- 1Department of Chemistry, College of Science, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates

- 2Department of Biology, College of Science, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates

- 3The Big Data Analytics Center, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates

- 4Zayed Center for Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates

Vibrio gazogenes PB1 is an estuarine bacterium that was first isolated from saltwater mud. This bacterial species possesses the metabolic capacity to produce prodigiosin which has potential uses as an anticancer agent, antibiotic, and a fungicide. We evaluated the feasibility of employing V. gazogenes PB1 as a bacterial host for the production of prodigiosin. V. gazogenes PB1 could be grown and maintained using the well-known lysogeny broth medium when supplemented with NaCl, and revived after storage at -80°C. Under batch conditions, growth of V. gazogenes PB1 in minimal media and production of prodigiosin was observed over a wide range of NaCl concentrations from 1 to 5% (w/v). The production of prodigiosin was significantly influenced by the concentration of glucose (as the carbon source), ammonium chloride (as the nitrogen source), inorganic phosphate ions, as well as pH. The greatest titer (231 mg/L) was observed in minimal media that contained 1% (w/v) glucose, 100 mM ammonium chloride and 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer. The sequences and chromosomal locations of the pig genes associated with prodigiosin biosynthesis are revealed for the first time. PigA is an isolated gene on chromosome 2, while the remaining pig genes, from pigB to pigN, exist as a 20 kb gene cluster on chromosome 1. Given its excellent growth in a range of NaCl concentrations, wide availability from culture collections and low-risk status for experimental work, we would conclude that V. gazogenes PB1 is a promising bacterial host for the production of prodigiosin.

Introduction

One of the most promising drug leads to come out in recent years is prodigiosin, a member of the prodiginine family. This red pigment possesses a wide range of biological activities. It inhibits the growth of several species of pathogenic bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Streptococcus pyogene (Lapenda et al., 2015) with minimum inhibitory and minimal bactericidal concentrations in the range of 4-16 μg/mL (Gohil et al., 2020). Montaner et al. (2000) earlier identified prodigiosin as an apoptotic agent. Several groups have replicated these findings using a variety of cancer cell lines (Montaner and Pérez-Tomás, 2001; Campàs et al., 2003; Perez-Tomas and Vinas, 2010; Dalili et al., 2012; Hassankhani et al., 2015; Berning et al., 2021). Currently, prodigiosin is in the preclinical phase for evaluation as an anti-cancer drug (Anwar et al., 2020).

Prodigiosin is a secondary metabolite which is produced in several species of bacteria such as Hahella chejuensis (Kim et al., 2007), Streptomyces grisiovirides (Kawasaki et al., 2009) and Serratia marcescens (Wasserman et al., 1960). Synthesis of prodigiosin is influenced by a variety of physiological and environmental factors including cell density (Haddix and Shanks, 2020), nutrient deprivation (Yin et al., 2021), physical and chemical stress (El-Bialy and Abou El-Nour, 2014), temperature (Williams et al., 1971), growth medium (Williams et al., 1971), oxygen supply (Heinemann et al., 1970), pH (Solé et al., 1994), and light (Someya et al., 2004).

S. marcescens is the most favoured bacterial host for prodigiosin synthesis (Wasserman et al., 1960; Morrison, 1966; Williams, 1973; Gerber, 1975; Darshan and Manonmani, 2015; Woodhams et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). A large number of studies have evaluated a range of cultivation conditions for prodigiosin production in S. marcescens (Giri et al., 2004; Wei and Chen, 2005; Chen et al., 2013; Kurbanoglu et al., 2015; Elkenawy et al., 2017; Faraag et al., 2017). To date, the highest reported titer for S. marcescens is 50g/L using cassava wastewater as the feedstock (Araújo et al., 2010). Mutational approaches, involving exposure to chemical mutagens, UV irradiation and transposon insertion (El-Bialy and Abou El-Nour, 2014; Elkenawy et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2020), have also been attempted to further boost prodigiosin titers. Given its broad host range and the presence of virulence factors, a major drawback in the use of S. marcescens is its pathogenic status in humans (Hejazi and Falkiner, 1997). This opportunistic microorganism can cause pneumonia, urinary tract infections, meningitis and eye infections. S. marcescens is therefore not ideal for industrial-scale use. As an alternative approach, the metabolic pathway for prodigiosin has been transferred to GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) hosts, via synthetic biology approaches, for both Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas putida KT2440 species (Kwon et al., 2010; Domröse et al., 2015). However, due to the antibacterial properties of prodigiosin and the low titers reported in these non-native hosts, this has proven to be quite challenging. A biological host that is safe, reliable, and can be handled on a large scale and that offers gram quantities is still very much needed.

Vibrio gazogenes PB1, previously known as Beneckea gazogenes, is a mesophilic aerobe that was discovered in the late 70s for its red pigmentation, which was attributed to the accumulation of prodigiosin (Harwood, 1978; Baumann et al, 1980). This particular species is now widely available from several culture collections around the world. Although its growth characteristic and prodigiosin-producing trait was investigated by Allen et al. (Allen et al., 1983), the feasibility of employing V. gazogenes PB1 as a laboratory host for prodigiosin production still remains to be evaluated. Herein, we report that V. gazogenes PB1 possesses excellent physiological traits as a biotechnological host for prodigiosin production in minimal media, and reveal for the first time the DNA sequences and genomic arrangement of the pig genes associated with prodigiosin production.

Materials and Methods

Cultivation and Storage of V. Sazogenes PB1

V. gazogenes PB1 (ATCC: 29988, KCTC: 12695) was obtained from the Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC). For growth on solid media, V. gazogenes PB1 cells were initially streaked out on solid lysogeny broth (LB)/1.5% (w/v) agar plates supplemented with 3% (w/v) NaCl and incubated at 28°C for 2 days (Supplementary Figure 1). LB medium was composed of 10 grams of tryptone, 5 grams of yeast extract, and 10 grams of NaCl dissolved in 1 L of water. For growth in liquid media, V. gazogenes PB1 colonies from solid media plates were used to inoculate liquid LB medium supplemented with 3% (w/v) NaCl (LB-NaCl) and incubated at 28°C for up to 3 days. For cultivation experiments in minimal media, starter cultures were set up by inoculating 5 ml minimal media supplemented with 3% (w/v) NaCl (MM-NaCl). The composition of the minimal media was as follows: 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5, 21°C); 100 mM NH4Cl, 2 mM MgSO4; 0.1 mM CaCl2; micronutrient mix consisting of 10 nM FeSO4, 3 μM (NH4)6Mo7O24, 0.4 mM boric acid, 30 μM CoCl2, 15 μM CuSO4, 80 μM MnCl2 and 10 μM ZnSO4. A 2% (v/v) volume of starter culture was used to inoculate liquid MM-NaCl, and incubated at 28°C/180 rpm for up to 3 days. The growth rate and doubling time were determined from the exponential phase. The growth rate was calculated using the formula, ln (final OD650nm/initial OD650nm)/cultivation time (h). The doubling time (h) was calculated by taking the natural logarithm of 2 and dividing by the growth rate. For storage of V. gazogenes PB1 cells at -80°C, cells were cultured for 48 hours in 2 ml liquid LB-NaCl at 28°C/180 rpm, harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 2 ml fresh LB-NaCl, gently mixed with glycerol at a final concentration of 25% (v/v) and stored at -80°C without flash-freezing.

Genome Extraction

Genomic DNA (gDNA) extraction was undertaken using the Monarch Genomic DNA purification kit (New England Biolabs, NEB T3010). The cells were pelleted by centrifuging at 1,000 x g for 1 minute and resuspended in 100 µl ice cold PBS. Proteinase K (1 µl) and RNase A (3 µl) were added and mixed, followed by the addition of 100 µl cell lysis buffer. The mixture was incubated at 56°C for 5 minutes. gDNA binding buffer (400 µl) was added to the sample and mixed gently by inverting the tube. The lysate mix was then transferred to a gDNA purification column and centrifuged for 3 minutes at 1,000 x g, followed by additional centrifugation for 1 minute at 12,000 x g. The column was transferred to a new collection tube and 500 µl gDNA wash buffer was added. The column was centrifuged for 1 minute at 12,000 rpm and the wash procedure was repeated. The gDNA purification column was then placed into a new 1.5 ml DNase-free tube and the gDNA eluted using 50 µl Tris-EDTA buffer. The extracted gDNA was quantified using Qubit 4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific USA). The quality of the DNA was evaluated using 1% (w/v) agarose gel, pre-stained with 4 µg ethidium bromide (Sigma Aldrich) and visualized using a GelDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad). The gDNA was shipped, in a freeze-dried form, at room temperature for genome sequencing.

Quantification of Prodigiosin

For determining the production of prodigiosin, a 10 μl cell culture was added to 190 μl of acidified ethanol in a microplate well and mixed. The absorbance was measured at 535 nm. Taking into account the true sample pathlength and sample dilution factor, as well as the height of the absorbance baseline, the absorbance value was converted to prodigiosin titer (mg/L) using the following formula, (Absorbance peak height at 535 nm x dilution factor)/(millimolar extinction coefficient x true sample pathlength) x molecular weight of prodigiosin (323.4 amu), and based on the extinction coefficient of 139, 800 M-1 cm-1 (which is equivalent to 139.8 mM-1 cm-1) as reported recently by Domröse et al. (Domröse et al., 2015).

Whole Genome Sequencing, Assembly and Annotation

Illumina short-read and Pacific Biosciences long-read whole genome sequencing was performed at Novogen (Singapore). A 350 bp sequencing library was prepared and paired-end sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). For long-read sequencing, an SMRTbell library was prepared and sequenced on a Pacific Biosciences Sequel II platform (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA). Quality of the reads were checked and adapters were trimmed using Trimmomatic version 0.39 (Bolger et al., 2014). Hybrid assembly, using Illumina short-reads and PacBio long-reads, was performed using Unicycler version 0.4.9 (Wick et al., 2017) set with the default options. The final assembly was annotated using the Rapid Annotation Subsystem Technology (RAST) server (https://rast.nmpdr.org) (Brettin et al., 2015) and the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) (Tatusova et al., 2016) before submission to the NCBI Genome database. Gene clusters of secondary metabolites were analysed using antiSMASH (Blin et al., 2021) and pathway mapping of protein sequences was performed using the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS) (Moriya et al., 2007). Homologous pig proteins in the genome were identified using an in-house BLAST server based on the pig protein sequences of S. marcescens obtained from UniProt.

Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data represent the means ± SD of at least 3 independent culture experiments. Any significant differences between sample treatments were determined using a one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s tests to identify sample treatments which showed statistically significantly differences. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Cell Growth, Maintenance and Storage of V. gazogenes PB1

To assess the practical aspects of working with V. gazogenes PB1 as a biotechnological host, we explored its ease of cultivation in the well-known lysogeny broth (often abbreviated to LB), typically used for E. coli studies. We were able to grow and maintain the species in either standard liquid and solid LB medium supplemented with NaCl from 2 to 3% (w/v) (LB-NaCl). When V. gazogenes PB1 was streaked out on solid media plates, small orange colonies with a diameter less than 1mm were observed as early as 24 hours of cultivation. Larger red colonies appeared after 48 hours of growth (Supplementary Figure 1). Using glycerol as a cryopreservative, V. gazogenes could also be stored frozen at -80°C in liquid LB-NaCl medium and revived later, even after several months of storage, for experiments. Moreover, colonies that were stored in the fridge for a 1-week period could be successfully restreaked on solid LB-NaCl plates or used as an inoculum. However, slight thawing of the glycerol stock or prolonged incubation in the fridge (4°C, >1 week) resulted in a significant loss of culturally viable cells. In extreme cases, the cells could not be revived even after several attempts of inoculation in both solid and liquid LB-NaCl media. Thus, a great amount of care and attention needs to be exercised when handling and maintaining V. gazogenes PB1 cells.

Growth Profile of V. gazogenes PB1 in NaCl-Supplemented Minimal Media

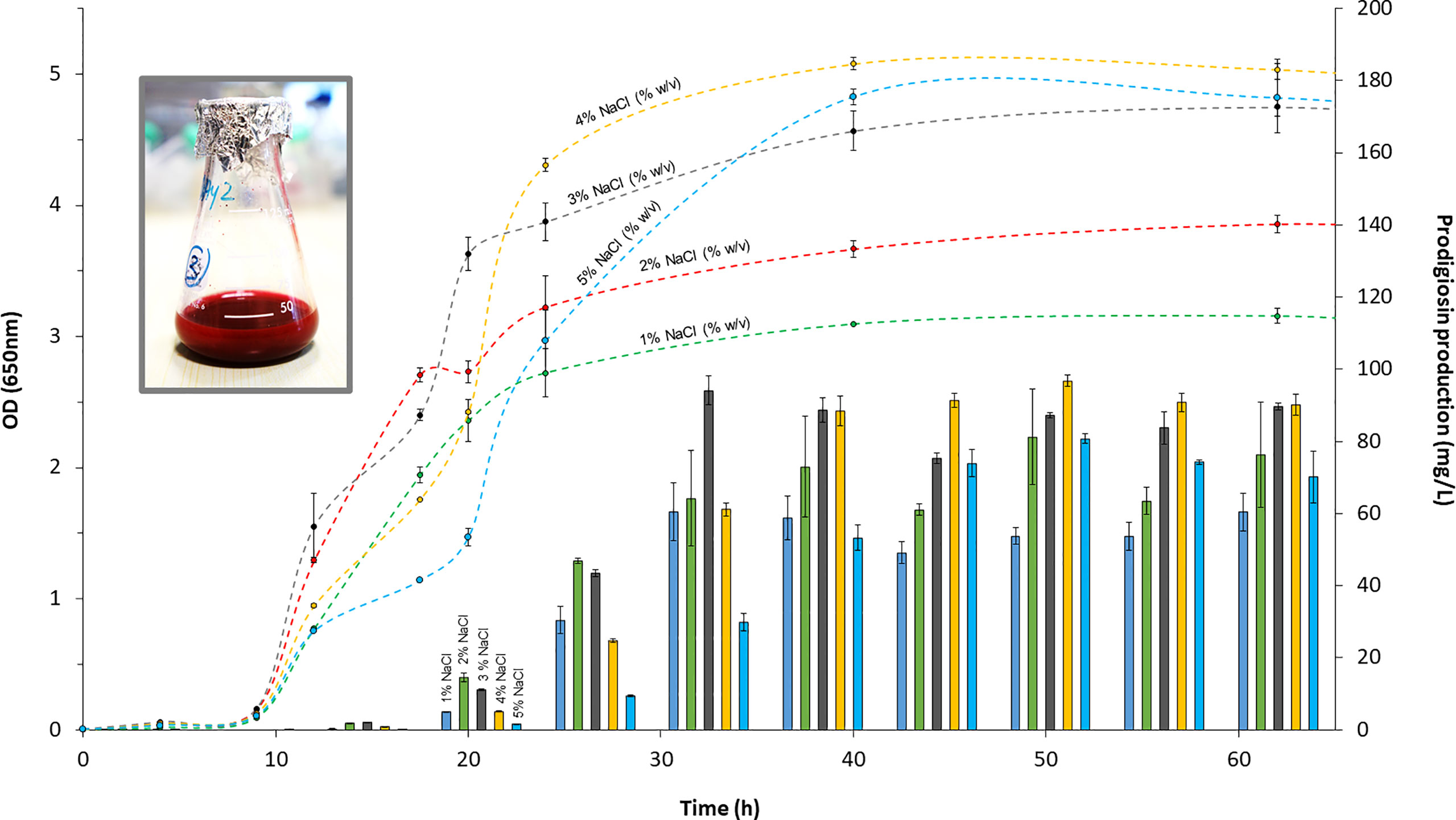

Given that V. gazogenes PB1 was originally sourced from saltwater marsh, we evaluated the growth of V. gazogenes PB1 in minimal media to identify the optimal NaCl concentration for growth. Cells were cultivated over a 3-day period at 28°C in minimal media over a NaCl concentration ranging from 1 to 5% (w/v). Glucose at 1% (w/v) was used as the carbon source for growth. Cell density was determined by monitoring light scattering at 650 nm. The classical bacterial growth curve was observed which displayed the 3 phases of growth: lag, exponential and stationary (Figure 1). At NaCl concentrations of 1% (w/v), 2% (w/v), 4% (w/v) and 5% (w/v) NaCl concentrations, the lag phase was extended by as much as 2 hours. Cell clumping was also noted in these cultures during the early hours of the cultivation period. The growth rates, determined from the exponential phases did not differ greatly and ranged from 0.29 to 0.24 per hour which translated to a doubling time of 2.4 to 2.9 hours. Cultivation at 3% (w/v) NaCl was found to be the most ideal for growth offering a short lag phase, fast growth rate and high cell densities. Most importantly though, these results show that V. gazogenes PB1 is highly tolerant to NaCl and capable of growing in a wide range of NaCl concentrations.

Figure 1 The growth profile and the production of prodigiosin at different concentrations of NaCl. V. gazogenes PB1 was cultivated in minimal media at 28°C over a period of 3 days in the presence of 1 - 5% (w/v) NaCl. OD values at 650 nm are shown with dashed lines, while prodigiosin production is shown with solid bars.

Production of Prodigiosin in Na-Cl Supplemented Minimal Media

Since its discovery in 1978, V. gazogenes is known to be a prodigiosin-producing bacterial species (Harwood, 1978). To assess the capabilities of V. gazogenes PB1 for prodigiosin production, we monitored prodigiosin levels in minimal media over a 3-day period (Figure 1). After its verification by NMR, prodigiosin was quantified in acidified ethanol at 535 nm, as described previously using the molar extinction coefficient of 139, 800 M-1 cm-1 (Domröse et al., 2015). The levels of prodigiosin became noticeable during the early exponential phase at 12 hours of cultivation. Going into the mid- to late-exponential phases, prodigiosin levels increased substantially (Figure 1). Due to the accumulation of prodigiosin, V. gazogenes PB1 cultures developed a strong red color. The pigment levels remained fairly stable as the host entered the stationary phase suggesting that metabolic degradation of prodigiosin does not pose an issue even after prolonged incubation. The greatest productivity of prodigiosin was observed at 3% (w/v) NaCl resulting in a titer of 94 ( ± 4) mg/L. In a separate batch experiment using a shake-flask, the highest titer observed was 231 ( ± 5) mg/L (Figure 1). More importantly though, we noted that V. gazogenes PB1 is capable of significant levels of pigment production over the entire 1 to 5% (w/v) concentration range of NaCl.

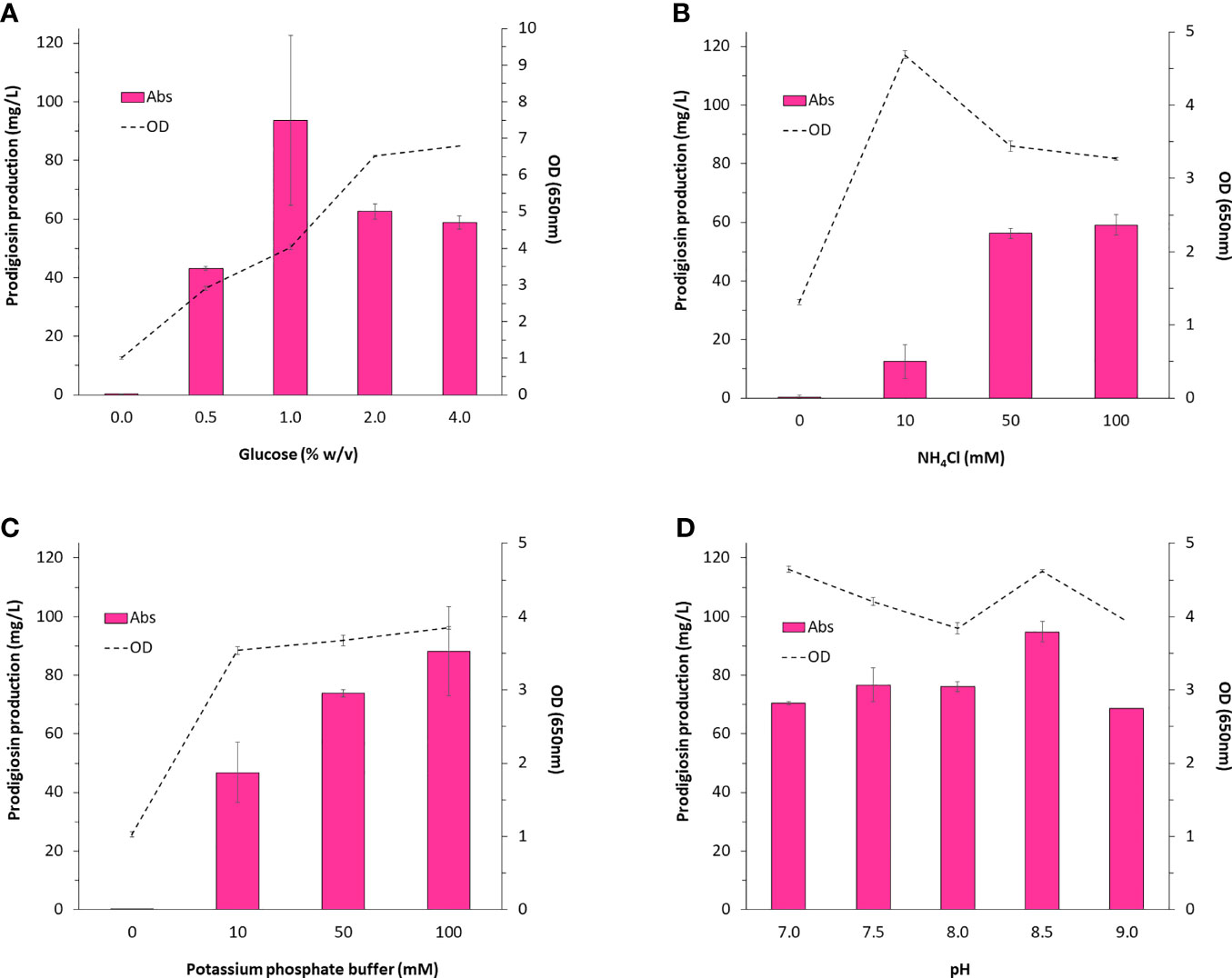

Growth Medium Components That Influence Prodigiosin Production

We were particularly interested in identifying key components of the medium that could impact prodigiosin production. For this we considered glucose and ammonium chloride which would serve as the carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively, for the synthesis of prodigiosin (C20H25N3O), as well as inorganic phosphate which had been investigated in an earlier study (Allen et al., 1983). In all cases, varying the concentration of these media components had a noticeable impact on pigment production (Figures 2A–C). Statistical analysis confirmed that these factors were strongly correlated to pigment production. The general trend observed was that increasing the source of carbon, nitrogen and inorganic phosphate ions increased pigment production. This also correlated well with cell growth indicating that increased pigment production was attributed to greater biomass. However, in the specific case of glucose, exceeding the 1% (w/v) glucose concentration resulted in a 2-fold drop in pigment production. Since growth was not inhibited in any way and in fact stimulated by almost 2-fold, suggests that excess carbon is inefficiently diverted towards biomass rather than prodigiosin synthesis. Interestingly, since inorganic phosphate ions can also act as a buffering agent, a 20% improvement in prodigiosin levels was noted when the culture was grown at a pH of 8.5 (Figure 2D). In summary, batch cultivation conditions using 1% (w/v) glucose, 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.5), and 100 mM NH4Cl would serve as an excellent starting point for any future investigations concerning the production of prodigiosin in V. gazogenes PB1 in minimal media.

Figure 2 Medium components impacting the production of prodigiosin in V. gazogenes PB1. V. gazogenes PB1 was cultivated in minimal media at 28°C in the presence of (A) 0 - 4% (w/v) glucose, (B) 0 - 100 mM ammonium chloride, (C) 0 - 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), and (D) 100 mM phosphate buffer adjusted from pH of 7 to 9.

Identification of the pig Genes Associated With Prodigiosin Biosynthesis

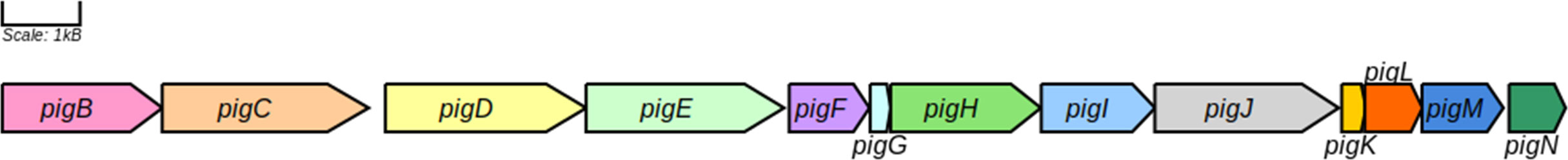

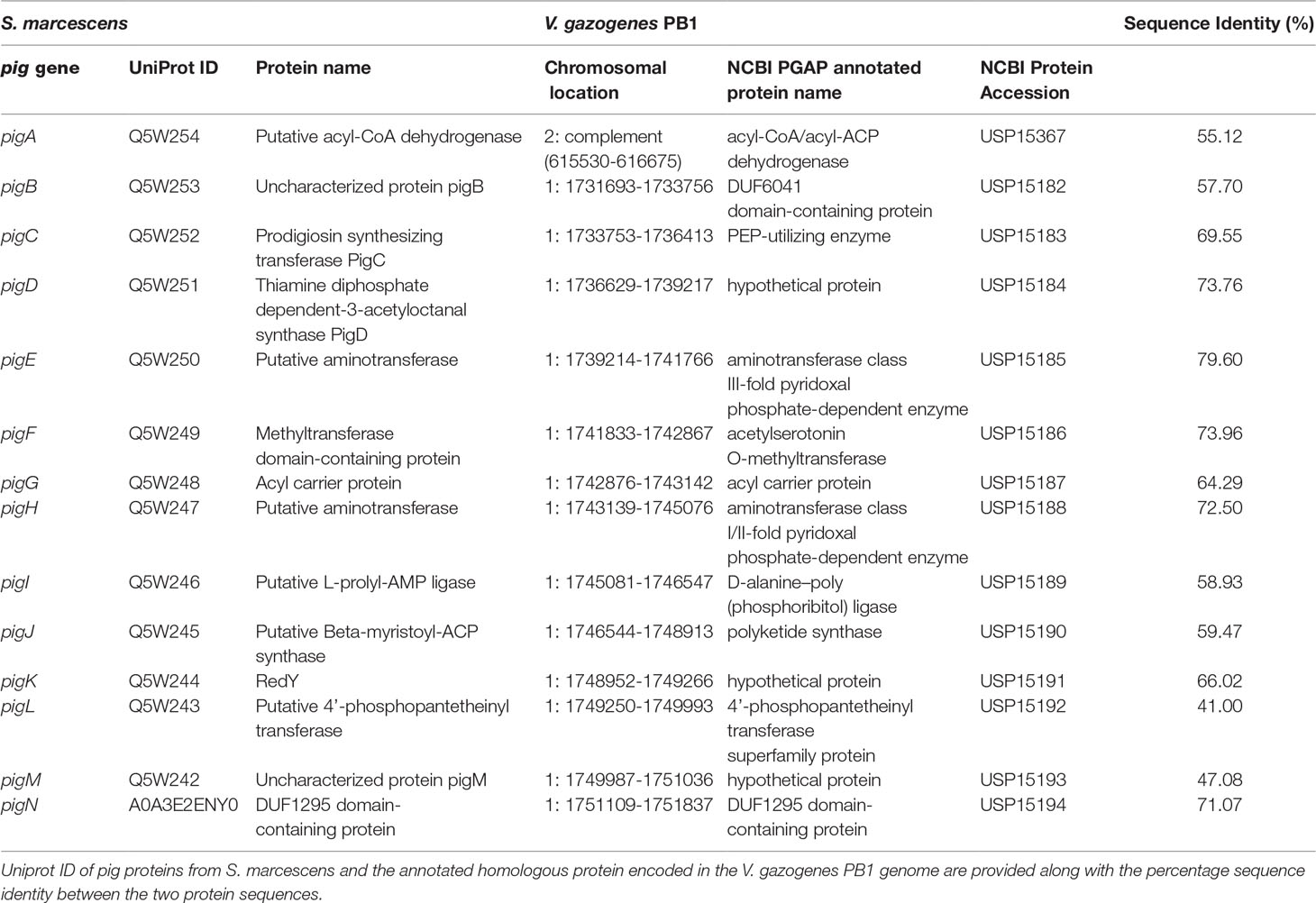

The pig genes responsible for prodigiosin production in V. gazogenes PB1 still remain unknown. An initial assessment of the V. gazogenes PB1 genome sequence using antiSMASH, a tool used for the identification of gene clusters for the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, reported the presence of the prodigiosin producing gene cluster on chromosome 1 (NCBI Accession: CP092587) between 1,723,753-1,758,913 with 70% similarity to the corresponding gene cluster found in S. marcescens (Table 1). Subsequently, we submitted the annotated protein sequences to KAAS to evaluate the presence of all necessary homologous proteins in V. gazogenes PB1 associated with prodigiosin synthesis. A mapping of this to the KEGG prodigiosin biosynthesis pathway map00333 revealed the presence of pig enzymes essential for the production of prodigiosin (Supplementary Figure 2). BLAST searches of S. marcescenspig proteins in V. gazogenes PB1 revealed the presence of all pig proteins, including the ones essential for prodigiosin production, with at least 45% sequence identity (Supplementary Table 1). The putative pigB-pigN genes are located sequentially on chromosome 1 (Figure 3) between positions 1731693 – 1751837, while pigA gene is located on the minus strand of chromosome 2 (NCBI Accession: CP092588) between 615530 – 616675. Based on protein BLAST searches, the proteins encoded by these genes also share 100% sequence identity with previously reported V. gazogenes proteins and high sequence identity with a bacterium from the Vibrio genus and other prodigiosin-producing bacteria such as Pseudoalteromonas rubra, S. rubidaea, and Rugamonas rubra (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 1 Identification of putative pig genes in the V. gazogenes PB1 genome based on annotated pig genes in S. marcescens.

Discussion

V. gazogenes PB1 is a widely available bacterial strain and can be sourced from several culture collections with the following reference numbers: ATCC (American culture collection), 29988; KCTC (Korea culture collection), 12695; CIP (Pasteur Institute culture collection), 103173; CECT (Spanish culture collection), 5068; DSM (German culture collection), 21264; JCM (Japan Culture Collection) 21187; NBRC (NITE Biological Research Center culture collection), 103151; CCUG (University Of Gothenburg culture collection), 57114; IAM (Institute of Applied Microbiology culture collection), 14404; NCIMB (National Collection of Industrial, Food and Marine Bacteria culture collection), 2250. One observed drawback in using V. gazogenes PB1 is the finicky nature of this species during cultivation and storage. On several occasions, it was noted that repeated streaks from the same glycerol stock or prolonged storage in the fridge, exceeding 2 weeks, often resulted in a drastic loss in the cultivability of V. gazogenes PB1. This behaviour commonly encountered for Vibrio species, could possibly reflect the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state during which cells are viable but fail to replicate on account of entering a dormant state. In this state, cells can be difficult to revive (Ramamurthy et al., 2014). However, such a predicament can be avoided if care and attention is given to the handling of master glycerol stocks and re-streaking on a weekly basis.

Clearly, V. gazogenes possesses the pathway for the production of the secondary metabolite, prodigiosin. The biochemical pathway for prodigiosin synthesis was first elucidated almost 50 years ago using mutants of S. marcescens. (Morrison, 1966; Williams, 1973). The pathway requires as many as 14 genes; 12 encode for proteins directly involved in the biochemical synthesis of prodigiosin while the remaining 2 are thought to have auxiliary roles (Loeschcke et al., 2013). The pathway is bifurcated in which the final step, the condensation of 4-methoxy-2,2′-bipyrrole-5-carbaldehyde and monopyrrole (MBC) and 2-methyl-3-n-amyl-pyrrole (MAP), is catalysed by pigC (Picott et al., 2020). Prodiogiosin is synthesized in several species of bacteria (Darshan and Manonmani, 2015). A comparison of the pig proteins in available genomes of these species shows remarkable conservation of these proteins (Supplementary Table 2). Additionally, the pig genes appear to be part of a contiguous gene cluster in most species, apart from pigN in Pseudoalteromonas rubra. However, what distinguishes the Vibrio genera appears to be the separation of pigA on chromosome 2, while the remaining pig genes reside on the longer chromosome 1.

Interestingly, we did not observe the presence of any prodigiosin analog(s). Support for this is based on two pieces of evidence. The first is from the NMR analysis which did not reveal any peaks to indicate the presence of a prodigiosin analog(s). The second is from the bioinformatics analysis which did not identify any homologs for RedJ, RedK and RedL proteins which would be required for the synthesis of undecylprodigiosin (refer to Supplementary Figure 2). Undecylprodigiosin can therefore be ruled out as a possible analog. Since both butyl-meta-cycloheptylprodiginine (also known as streptorubin B) and metacycloprodigiosin are derived from undecylprodigiosin, via RedG and McpG, respectively, these analogs can also be ruled out along with other cyclic variants such as prodigiosin R1, prodigiosin R2, cycloprodigiosin which also contain an undecyl backbone within their structures (Kimata et al., 2016, Kimata et al., 2018). Thus, it is highly unlikely that there is interference from other prodigiosin analogs, as reported for other species (Tsao et al., 1985; Kimata et al., 2018).

V. gazogenes PB1 possesses a couple of phenotypic traits that would make it a more superior host than S. marcescens for the production of prodigiosin. The first is that V. gazogenes is able to tolerate and grow in saline conditions, as high as 5% (w/v) NaCl. (Siva et al., 2012). From an industrial perspective, this is a useful property as it avoids the stringent requirement for desalinated water which would greatly reduce large-scale production costs for prodigiosin production. Furthermore, high-salt media would hinder the growth of microbial contaminants during a scale-up (Skinner and Leathers, 2004). In contrast, S. marcescens is greatly inhibited with increasing concentrations of NaCl-supplemented medium (Silverman and Munoz, 1973). However, it is worth noting that since fermenters are traditionally made of stainless steel, they will be highly vulnerable to corrosion in the presence of NaCl (Long et al., 2017). Corrosion-resistant metals such as nickel–copper alloys would therefore be superior alternatives to stainless steel in the construction of marine-compatible fermenters (Powell and Michels, 2000). Second, V. gazogenes is classed as a Biosafety Level 1 organism and would therefore pose a low risk for human use. S. marcescens, on the other hand, is an opportunistic pathogen that is well known to causes infections in humans (Hejazi and Falkiner, 1997).

Although the titer obtained in this study is considerably less than what has been achieved in a previous study (Araújo et al., 2010) using S. marcescens, the intent of this study was not to optimize prodigiosin production, but rather to demonstrate the feasibility of working with V. gazogenes PB1 as a host for prodigiosin synthesis. We were able to firmly establish that the levels of glucose, nitrogen, and phosphate, as well as the pH, all have significant influential effects on the production of prodigiosin in V. gazogenes PB1. Further extensive work will need to be undertaken to identify the optimal cultivation conditions for the production of prodigiosin in V. gazogenes PB1.

To date, there has been only one comprehensive study on the use of V. gazogenes PB1 as a host for prodigiosin production (Allen et al., 1983). This study was conducted more than 30 years ago in which the authors reported a very small prodigiosin titer of 2 ng per ml (equivalent to 2 μg/L). In contrast to this, we observed a titer as high as 230 mg/L, which is 2 orders of magnitude greater than what was reported by Allen et al. (Allen et al., 1983). In re-evaluating V. gazogenes PB1 we can confirm here that this bacterial species is very much a capable bacterial host for prodigiosin production with phenotypic traits that are ideal for biotechnological use.

Conclusion

Given its excellent growth in high-salt medium, modest production levels of prodigiosin under non-optimized conditions and the wide availability from several culture collections, our conclusion from this study is that V. gazogenes PB1 is a practicable host for further improving prodigiosin titers and its use merits further investigation.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

MKA conceptualized the study. DV carried out the in vivo experiments. DV carried out the genomic extraction and purification. DV and MSA carried out the extraction and quantification of prodigiosin. DV, BB, RV, and MKA analysed the results. DV and BB presented the results. BB, RV, and MKA analysed the sequencing data. BB and RV identified and annotated the genes for prodigiosin pathway. MKA drafted the manuscript. RV and MKA edited the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the UAEU Program for Advanced Research Funds awarded to MKA (12S011) and RV (12S006), in addition to the ‘SDG research program’ fund awarded to MKA.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.940888/full#supplementary-material

References

Allen G. R., Reichelt J. L., Gray P. P. (1983). Influence of Environmental Factors and Medium Composition on Vibrio gazogenes Growth and Prodigiosin Production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45, 1727–1732. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.6.1727-1732.1983

Anwar M. M., Shalaby M., Embaby A. M., Saeed H., Agwa M. M., Hussein A. (2020). Prodigiosin/PU-H71 as a Novel Potential Combined Therapy for Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC): Preclinical Insights. Sci. Rep. 2020 101 10, 1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71157-w

Araújo H. W. C., Fukushima K., Takaki G. M. C. (2010). Prodigiosin Production by Serratia Marcescens UCP 1549 Using Renewable-Resources as a Low Cost Substrate. Molecules 15, 6931. doi: 10.3390/MOLECULES15106931

Baumann P., Baumann L., Bang S. S., Woolkalis M. J. (1980). Reevaluation of the Taxonomy of Vibrio, Beneckea, and Photobacterium: Abolition of the Genus Beneckea. Curr. Microbiol. 4, 127–132. doi: 10.1007/BF02602814

Berning L., Schlütermann D., Friedrich A., Berleth N., Sun Y., Wu W., et al. (2021). Prodigiosin Sensitizes Sensitive and Resistant Urothelial Carcinoma Cells to Cisplatin Treatment. Molecules 26, 1294. doi: 10.3390/molecules26051294

Blin K., Shaw S., Kloosterman A. M., Charlop-Powers Z., Van Wezel G. P., Medema M. H., et al. (2021). antiSMASH 6.0: Improving Cluster Detection and Comparison Capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W29–W35. doi: 10.1093/NAR/GKAB335

Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B. (2014). Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTU170

Brettin T., Davis J. J., Disz T., Edwards R. A., Gerdes S., Olsen G. J., et al. (2015). RASTtk: A Modular and Extensible Implementation of the RAST Algorithm for Building Custom Annotation Pipelines and Annotating Batches of Genomes. Sci. Rep. 5, 8365. doi: 10.1038/SREP08365

Campàs C., Dalmau M., Montaner B., Barragán M., Bellosillo B., Colomer D., et al. (2003). Prodigiosin Induces Apoptosis of B and T Cells From B-Cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Leukemia 17, 746–750. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402860

Chen W. C., Yu W. J., Chang C. C., Chang J. S., Huang S. H., Chang C. H., et al. (2013). Enhancing Production of Prodigiosin From Serratia Marcescens C3 by Statistical Experimental Design and Porous Carrier Addition Strategy. Biochem. Eng. J. 78, 93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2013.02.001

Dalili D., Fouladdel S., Rastkari N., Samadi N., Ahmadkhaniha R., Ardavan A., et al. (2012). Prodigiosin, the Red Pigment of Serratia Marcescens, Shows Cytotoxic Effects and Apoptosis Induction in HT-29 and T47D Cancer Cell Lines. Nat. Prod. Res. 26, 2078–2083. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2011.622276

Darshan N., Manonmani H. K. (2015). Prodigiosin and its Potential Applications. J. Food Sci. Technol. 52, 5393–5407. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-1740-4

Domröse A., Klein A. S., Hage-Hülsmann J., Thies S., Svensson V., Classen T., et al. (2015). Efficient Recombinant Production of Prodigiosin in Pseudomonas Putida. Front. Microbiol. 6. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00972

El-Bialy H. A., Abou El-Nour S. A. (2014). Physical and Chemical Stress on Serratia Marcescens and Studies on Prodigiosin Pigment Production. Ann. Microbiol. 65, 59–68. doi: 10.1007/S13213-014-0837-8

Elkenawy N. M., Yassin A. S., Elhifnawy H. N., Amin M. A. (2017). Optimization of Prodigiosin Production by Serratia Marcescens Using Crude Glycerol and Enhancing Production Using Gamma Radiation. Biotechnol. Rep. 14, 47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2017.04.001

Faraag A. H., El-Batal A. I., El-Hendawy H. H. (2017). Characterization of Prodigiosin Produced by Serratia Marcescens Strain Isolated From Irrigation Water in Egypt. Nat. Sci. 15, 55–68. doi: 10.7537/MARSNSJ150517.08

Gerber N. N. (1975). Prodigiosin-Like Pigments. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 469–485. doi: 10.3109/10408417509108758

Giri A. V., Anandkumar N., Muthukumaran G., Pennathur G. (2004). A Novel Medium for the Enhanced Cell Growth and Production of Prodigiosin From Serratia Marcescens Isolated From Soil. BMC Microbiol. 4, 11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-4-11

Gohil N., Bhattacharjee G., Singh V. (2020). Synergistic Bactericidal Profiling of Prodigiosin Extracted From Serratia Marcescens in Combination With Antibiotics Against Pathogenic Bacteria. Microb. Pathog. 149, 104508. doi: 10.1016/J.MICPATH.2020.104508

Haddix P. L., Shanks R. M. Q. (2020). Production of Prodigiosin Pigment by Serratia Marcescens is Negatively Associated With Cellular ATP Levels During High-Rate, Low-Cell-Density Growth. Can. J. Microbiol. 66, 243. doi: 10.1139/CJM-2019-0548

Harwood C. S. (1978). Beneckea Gazogenes Sp. Nov., a Red, Facultatively Anaerobic, Marine Bacterium. Curr. Microbiol. 1, 233–238. doi: 10.1007/BF02602849

Hassankhani R., Sam M. R., Esmaeilou M., Ahangar P. (2015). Prodigiosin Isolated From Cell Wall of Serratia Marcescens Alters Expression of Apoptosis-Related Genes and Increases Apoptosis in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Med. Oncol. 32, 1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0366-0

Heinemann B., Howard A. J., Palocz H. J. (1970). Influence of Dissolved Oxygen Levels on Production of L-Asparaginase and Prodigiosin bySerratia. marcescens. 19, 800–804. doi: 10.1128/am.19.5.800-804.1970

Hejazi A., Falkiner F. R. (1997). Serratia Marcescens. J. Med. Microbiol. 46, 903–912. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-11-903

Kawasaki T., Sakurai F., Nagatsuka S. Y., Hayakawa Y. (2009). Prodigiosin Biosynthesis Gene Cluster in the Roseophilin Producer Streptomyces Griseoviridis. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo). 62, 271–276. doi: 10.1038/ja.2009.27

Kimata S., Izawa M., Kawasaki T., Hayakawa Y. (2016). Identification of a Prodigiosin Cyclization Gene in the Roseophilin Producer and Production of a New Cyclized Prodigiosin in a Heterologous Host. J. Antibiot. 2017 702 70, 196–199. doi: 10.1038/ja.2016.94

Kimata S., Matsuda T., Suizu Y., Hayakawa Y. (2018). Prodigiosin R2, a New Prodigiosin From the Roseophilin Producer Streptomyces Griseoviridis 2464-S5. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo). 71, 393–396. doi: 10.1038/S41429-017-0011-1

Kim D., Lee J. S., Park Y. K., Kim J. F., Jeong H., Oh T. K., et al. (2007). Biosynthesis of Antibiotic Prodiginines in the Marine Bacterium Hahella Chejuensis KCTC 2396. J. Appl. Microbiol. 102, 937–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03172.x

Kurbanoglu E. B., Ozdal M., Ozdal O. G., Algur O. F. (2015). Enhanced Production of Prodigiosin by Serratia Marcescens MO-1 Using Ram Horn Peptone. Braz. J. Microbiol. 46, 631–637. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838246246220131143

Kwon S. K., Park Y. K., Kim J. F. (2010). Genome-Wide Screening and Identification of Factors Affecting the Biosynthesis of Prodigiosin by Hahella Chejuensis, Using Escherichia Coli as a Surrogate Host.Appl Environ Microbiol 76, 1661–1668. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01468-09

Lapenda J. C., Silva P. A., Vicalvi M. C., Sena K. X. F. R., Nascimento S. C., JC L., et al. (2015). Antimicrobial Activity of Prodigiosin Isolated From Serratia Marcescens UFPEDA 398. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 31, 399–406. doi: 10.1007/s11274-014-1793-y

Loeschcke A., Markert A., Wilhelm S., Wirtz A., Rosenau F., Jaeger K.-E., et al. (2013). TREX: A Universal Tool for the Transfer and Expression of Biosynthetic Pathways in Bacteria. ACS Synth. Biol. 2, 22–33. doi: 10.1021/SB3000657

Long Y., Feng C., Peng B., Xie Y., Wang J., Zhang M., et al. (2017). Corrosion Behaviour of T92 Steel in NaCl Solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 12, 5104–5120. doi: 10.20964/2017.06.13

Montaner B., Navarro S., Piqué M., Vilaseca M., Martinell M., Giralt E., et al. (2000). Prodigiosin From the Supernatant of Serratia Marcescens Induces Apoptosis in Haematopoietic Cancer Cell Lines. Br. J. Pharmacol. 131, 585–593. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703614

Montaner B., Pérez-Tomás R. (2001). Prodigiosin-Induced Apoptosis in Human Colon Cancer Cells. Life Sci. 68, 2025–2036. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01002-5

Moriya Y., Itoh M., Okuda S., Yoshizawa A. C., Kanehisa M. (2007). KAAS: An Automatic Genome Annotation and Pathway Reconstruction Server. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W182–W185. doi: 10.1093/NAR/GKM321

Morrison D. A. (1966). Prodigiosin Synthesis in Mutants of Serratia Marcesens. J. Bacteriol. 91, 1599–1604. doi: 10.1128/jb.91.4.1599-1604.1966

Perez-Tomas R., Vinas M. (2010). New Insights on the Antitumoral Properties of Prodiginines. Curr. Med. Chem. 17, 2222–2231. doi: 10.2174/092986710791331103

Picott K. J., Deichert J. A., DeKemp E. M., Snieckus V., Ross A. C. (2020). Purification and Kinetic Characterization of the Essential Condensation Enzymes Involved in Prodiginine and Tambjamine Biosynthesis. Chembiochem 21, 1036–1042. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201900503

Powell C. A., Michels H. T. (2000). Copper-Nickel Alloys for Seawater Corrosion Resistance and Antifouling-A State of the Art Review. Available at: https://onepetro.org/NACECORR/proceedings-abstract/CORR00/All-CORR00/NACE-00627/111669

Ramamurthy T., Ghosh A., Pazhani G. P., Shinoda S. (2014). Current Perspectives on Viable But non-Culturable (VBNC) Pathogenic Bacteria. Front. Public Heal. 2. doi: 10.3389/FPUBH.2014.00103

Silverman M. P., Munoz E. F. (1973). Effect of Iron and Salt on Prodigiosin Synthesis in Serratia Marcescens. J. Bacteriol. 38, 999–1006. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.3.999-1006.1973

Siva R., Subha K., Bhakta D., Ghosh A. R., Babu S. (2012). Characterization and Enhanced Production of Prodigiosin From the Spoiled Coconut. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 166, 187–196. doi: 10.1007/s12010-011-9415-8

Skinner K. A., Leathers T. D. (2004). Bacterial Contaminants of Fuel Ethanol Production. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 31, 401–408. doi: 10.1007/S10295-004-0159-0

Solé M., Rius N., Francia A., Lorén J. G. (1994). The Effect of pH on Prodigiosin Production by non-Proliferating Cells of Serratia Marcescens. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 19, 341–344. doi: 10.1111/J.1472-765X.1994.TB00470.X

Someya N., Nakajima M., Hamamoto H., Yamaguchi I., Akutsu K. (2004). Effects of Light Conditions on Prodigiosin Stability in the Biocontrol Bacterium Serratia Marcescens Strain B2. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 70, 367–370. doi: 10.1007/S10327-004-0134-7

Sun Y., Wang L., Pan X., Osire T., Fang H., Zhang H., et al. (2020). Improved Prodigiosin Production by Relieving CpxR Temperature-Sensitive Inhibition. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8. doi: 10.3389/FBIOE.2020.00344

Tatusova T., Dicuccio M., Badretdin A., Chetvernin V., Nawrocki E. P., Zaslavsky L., et al. (2016). NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 6614–6624. doi: 10.1093/NAR/GKW569

Tsao S. W., Rudd B. A. M., He X. G., Chang C. J., Floss H. G. (1985). Identification of a Red Pigment From Streptomyces Coelicolor A3(2) as a Mixture of Prodigiosin Derivatives. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo). 38, 128–131. doi: 10.7164/ANTIBIOTICS.38.128

Wang S. L., Wang S. L., Nguyen V. B., Doan C. T., Doan C. T., Tran T. N., et al. (2020). Production and Potential Applications of Bioconversion of Chitin and Protein-Containing Fishery Byproducts Into Prodigiosin: A Review. Molecules 25, 2744. doi: 10.3390/molecules25122744

Wasserman H. H., McKeon J. E., Santer U. V. (1960). Studies Related to the Biosynthesis of Prodigiosin in Serratia Marcescens. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 3, 146–149. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(60)90211-4

Wei Y. H., Chen W. C. (2005). Enhanced Production of Prodigiosin-Like Pigment From Serratia Marcescens SMΔR by Medium Improvement and Oil-Supplementation Strategies. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 99, 616–622. doi: 10.1263/JBB.99.616

Wick R. R., Judd L. M., Gorrie C. L., Holt K. E. (2017). Unicycler: Resolving Bacterial Genome Assemblies From Short and Long Sequencing Reads. PLos Comput. Biol. 13, e1005595. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PCBI.1005595

Williams R. P. (1973). Biosynthesis of Prodigiosin, a Secondary Metabolite of Serratia Marcescens. Appl. Microbiol. 25, 396–402. doi: 10.1128/aem.25.3.396-402.1973

Williams R. P., Gott C. L., Qadri S. M., Scott R. H. (1971). Influence of Temperature of Incubation and Type of Growth Medium on Pigmentation in Serratia Marcescens. J. Bacteriol. 106, 438–443. doi: 10.1128/JB.106.2.438-443.1971

Woodhams D. C., LaBumbard B. C., Barnhart K. L., Becker M. H., Bletz M. C., Escobar L. A., et al. (2018). Prodigiosin, Violacein, and Volatile Organic Compounds Produced by Widespread Cutaneous Bacteria of Amphibians can Inhibit Two Batrachochytrium Fungal Pathogens. Microb. Ecol. 75, 1049–1062. doi: 10.1007/s00248-017-1095-7

Keywords: marine, bacteria, secondary metabolite, high-value chemical, industrial biotechnology

Citation: Vijay D, Baby B, Alhayer MS, Vijayan R and Akhtar MK (2022) Native Production of Prodigiosin in the Estuarine Bacterium, Vibrio gazogenes PB1, and Identification of the Associated pig Genes. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:940888. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.940888

Received: 10 May 2022; Accepted: 17 June 2022;

Published: 08 August 2022.

Edited by:

Thomas Bartholomäus Brück, Technical University of Munich, GermanyReviewed by:

Fernando Reyes, Fundación MEDINA, SpainJoachim Wink, Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers (HZ), Germany

Copyright © 2022 Vijay, Baby, Alhayer, Vijayan and Akhtar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ranjit Vijayan, cmFuaml0LnZAdWFldS5hYy5hZQ==; M. Kalim Akhtar, bWsuYWtodGFyQHVhZXUuYWMuYWU=

†ORCID: M. Kalim Akhtar, orcid.org/0000-0002-8805-0373

Dhanya Vijay

Dhanya Vijay Bincy Baby

Bincy Baby Maryam S. Alhayer1

Maryam S. Alhayer1 Ranjit Vijayan

Ranjit Vijayan M. Kalim Akhtar

M. Kalim Akhtar