95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 26 May 2022

Sec. Marine Fisheries, Aquaculture and Living Resources

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.912409

This article is part of the Research Topic Mollusk Breeding and Genetic Improvement View all 25 articles

Genome editing using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 is enabling genetics improvement of productive traits in aquaculture. Previous studies have proven CRISPR/Cas9 to be feasible in oyster, one of the most cultured shellfish species. Here, we applied electroporation-based CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of β-tubulin and built a highly efficient genome editing system in Crassostrea gigas angulate. We identified the β-tubulin gene in the oyster genome and showed its spatiotemporal expression patterns by analyzing RNA-seq data and larval in situ hybridization. We further designed multiple highly specific guide RNAs (sgRNAs) for its coding sequences. Long fragment deletions were detected in the mutants by agarose gel electrophoresis screening and further verified by Sanger sequencing. In addition, the expression patterns of Cgβ-tubulin in the trochophore peritroch and intestinal cilia cells were altered in the mutants. Scanning electron microscopy represented shortened and almost complete depleted cilia at the positions of peritroch and the posterior cilium ring in Cgβ-tubulin mosaic knockout trochophores. Moreover, the larval swimming behavior in the mutants was detected to be significantly decreased by motility assay. These results demonstrate that β-tubulin is sufficient to mediate cilia development and swimming behavior in oyster larvae. By applying Cgβ-tubulin as a marker gene, our study established CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mosaic mutagenesis technology based on electroporation, providing an efficient tool for gene function validation in the oyster. Moreover, our research also set up an example that can be used in genetic engineering breeding and productive traits improvement in oysters and other aquaculture species.

Aquaculture has gradually become the main source of seafood for human diets because of the high-quality animal protein (FAO, 2020). However, compared to many terrestrial livestock and crop systems, most aquaculture species’ breeding is still in the early stages (Ahmed and Thompson, 2019). Previous breeding programs such as selective, cross, and marker-assisted breeding systems have been advancing genetic improvement of economic traits, including disease resistance, nutritional values, growth quality, and reproduction (Langdon, 2006; Dove and O'Connor, 2010; Rawson et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012; Frank-Lawale et al., 2014; Melo et al., 2016); however, the breeding processes is significantly limited by a number of constraints, such as the low heritability of the economic traits and the long generation time of the aquaculture organisms. The oyster, Crassostrea gigas angulata (Li et al., 2013), is a representative bivalve mollusk, which is one of the main aquaculture shellfish worldwide. It has the complex developmental stages consisting of free-swimming trochophore, veliger larva, permanently fixated juvenile, and adult after metamorphosis, and has been widely studied in developmental biology, conservation biology, and ecology (Riviere et al., 2017; Song et al., 2017; Yue et al., 2018; Chan et al., 2021). In industry, oyster breeding is still thought to be at an early stage of domestication (Houston et al., 2020). One promising approach to solving the aquaculture challenges is to use CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)/Cas9 system-mediated genomic editing technology (Hollenbeck and Johnston, 2018; Abe and Kuroda, 2019).

CRISPR/Cas9 system has been developed into a revolutionary technology, which allows researchers to perform a variety of genetic experiments by inducing loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations at a precise position (Eid and Mahfouz, 2016; Momose and Concordet, 2016; Chen et al., 2017). Due to its high efficiency, this technology has been successfully applied to at least 13 aquaculture species, including the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) (Straume et al., 2020), tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) (Li et al., 2014), sea bream (Sparus aurata) (Ohama et al., 2020), channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) (Simora et al., 2020), southern catfish (Silurus meridionalis) (Li et al., 2016), common carp (Cyprinus carpio) (Chen et al., 2019), rohu carp (Labeo rohita) (Chakrapani et al., 2016), grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) (Ma et al., 2018), northern Chinese lamprey (Lethenteron morii) (Zu et al., 2016), rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) (Cleveland et al., 2018), Olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) (Kim et al., 2019), ridgetail white prawn (Exopalaemon carinicauda) (Gui et al., 2016), and oysters (C. gigas and C. gigas angulata) (Yu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021; Jin et al., 2021), which suggests that the CRISPR system has becoming a practical gene editing tool in molluscan studies. In the studies of two cultured molluscan species, Yu et al. knockout of the target genes myostatin and Twist by microinjection of CRISPR/Cas9 complexes and one single sgRNA, which leads to 1–24 bp small indel mutation during genotyping (Yu et al., 2019). The same group recently reported microinjection-based mutation phenotypes including defective musculature and reduced mortality in the myosin essential light chain genes knockout mutants (Li et al., 2021). With small size egg and embryo at a size <50 μm in diameter, electroporation provides a more effective method for CRISPR complex delivery in the oysters. Jin et al. reported in 2021 that a pYSY-Cas9-gRNA-GFP vector plasmid was successfully delivered into the embryos of C. gigas angulate by electroporation (Jin et al., 2021), suggesting that electroporation-based CRISPR genome editing is a practical, time- and labor-efficient way in molluscan. Still, the sustainable development of the oyster genome editing breeding technics calls for establishing electroporation-based CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis tool that generates defective phenotypes.

As one of the marine benthonic organisms, oyster has a free-swimming larval stage that facilitates dispersal and locates a suitable habitat. A large number of arranged cilia is thought to be the swimming organ driving dispersal and settlement (Nielsen, 2004; Nielsen, 2005). Besides, cilia are also considered to play important roles in predator avoidance, feeding, and intestinal motility (Davenport and Yoder, 2005; Berbari et al., 2009; Pernet, 2018). β-Tubulin protein has been found to be expressed in cells located in the ciliary band of the trochophore of Patella vulgata and polychaete Hydroides elegans (Damen and Dictus, 1994; Arenas-Mena et al., 2007) where they contribute to cilia microtubules. However, the cilia-related functions of this gene were not known in oysters, although our recent study based on transcriptome has demonstrated that β-tubulin genes were highly expressed during the trochophore stage of C. gigas (Zhang et al., 2012).

In this study, we used β-tubulin as a marker gene and performed CRISPR-mediated knockout by electroporation in C. gigas angulate. Through direct genotyping, long fragments deletions were detected in the target gene. By in situ hybridization, scanning electron microscopy, and behavioral analysis, we observed mosaic mutations including defective cilia and decreased motility in the G0 larva. These results demonstrate that Cgβ-tubulin is sufficient to mediate cilia development and swimming in larval oyster. Based on convincing genotypes and phenotypes in the mutants, our study established electroporation-based CRISPR/Cas9 knockout as a practical, time- and labor-efficient method for studies of gene function in the oyster. In addition, our research also provides a robust tool for genetically engineered breeding to enhance beneficial traits in oysters and other marine bivalves for aquaculture.

The experimental adult C. gigas angulate from a local oyster farm in Fujian, China, were brought back to the lab under fresh condition (~10°C). Then, the oysters were acclimated for 7 days in 1 μm of filtered seawater (FSW) at 23°C (Figure 1). Gamete collection and in vitro fertilization were performed according to the method reported in a previous study (Zhang et al., 2012). After fertilization, the fertilized eggs were transferred to a 4-mm gap cuvette for electroporation. The electroporated eggs were then cultured in 1 μm FSW at 26°C (Figure 1). Embryos and larvae at various developmental stages (trochophore and D-shaped larvae) were collected and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C, respectively, for the subsequent characterization of knockout phenotypes based on whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Figure 1).

We designed a strategy to generate two and more cut sites using multiple single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs), which induces non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) to repair the resulting gap, and finally producing long deletions flanking the target loci. We designed five sgRNAs by manually screening genome regions for GGN18NGG or N20NGG protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences in the Cgβ-tubulin gene (Table 1). The DNA templates were generated by PCR with the Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) to synthesize Cgβ-tubulin-sgRNAs, using the sgRNA synthesis primers as shown in Table 1. Amplification was performed in a thermal cycler using a 30-s denaturation step at 95°C followed by 34 cycles of 13 s at 95°C, 15 s at 60°C, 15 s at 72°C, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Then, PCR products were purified by E.Z.N.A.®Gel Extraction Kit (OMEGA). All sgRNAs were synthesized by in vitro transcription using the MEGAscript T7 Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by purification using the RNA clean and concentrator ™-5 Kit (ZYMO Research, California, USA; PNAbio, California, USA). Cas9 protein was purchased from PNAbio (CP01-50).

Next, the gene editing efficiencies of the five sgRNAs that we synthesized were tested by in vitro digestion of Cgβ-tubulin cDNA fragment with Cas9 protein. In brief, 250 ng of purified DNA template (Cgβ-tubulin PCR product) was thoroughly mixed with 250 ng each sgRNA, 500 ng Cas9 protein, 2 μl bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 2 μl restriction enzyme buffer (NEB, Ipswich, USA; TAKARA, Kusatsu, Japan) in a 20-μl reaction volume. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, 1 μl RNaseH enzyme (TAKARA) was added to the mixture to digest the DNA template, followed by denaturation at 98°C for 5 min to terminate the reaction. Finally, the gene editing efficiency of each sgRNA was analyzed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel.

For electroporation, one-cell stage C. gigas angulate embryos were collected and diluted to an appropriate concentration of about 5×104 cells/ml. Then, the five sgRNA mixtures (with a final concentration of 30 ng/μl), the tracing dye Lucifer Yellow (Invitrogen, cat. no. D7156) and Cas9 protein (with a final concentration of 30 ng/μl) were added to the CRISPR/Cas9 system; then, the mixture was incubated for 10 min at room temperature (20–24°C). The mixture and the fertilized eggs were then transferred into an electroporation cuvette (1 mm, BTX, Cat. No. 45-0140). Electroporation was conducted in an ECM 830 Square Wave Electroporation system (BTX) using a square wave pulse (40 V, 50 ms, 1 pulse). After electroporation, the fertilized eggs were washed in 1 μm FSW and further developed at 26°C.

Genomic DNA of the trochophores were extracted by proteinase K digestion method. Briefly, 20 μl of DNA extraction buffer [50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 10 mM ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.03% Nonidet P 40 (NP-40), 0.3% Tween-20, 0.5 mg/ml proteinase K] was added for digestion. Then, each individual specimen was incubated for 2 h at 55°C, followed by denaturation at 98°C for 5 min and cooling to 4°C. The DNA fragments covering the target sites and their flanking sequences were generated by PCR using the Premix ExTaq Mix (TAKARA) according to the Cgβ-tubulin gene-specific primers (Table 1). To define the genetic mutations, the amplified DNA were then cloned into pMD18-T vector (TAKARA) and sequenced on an ABI 3730 sequencer.

To calculate the survival rate, 4% PFA was used to fix the living embryos that were collected 24 h post-fertilization (hpf). We calculated the survival rate by dividing the number of normal D-shaped larvae by the total number of embryos (including normal D-shaped larvae and undeveloped and malformed larvae). To evaluate the larval motility, the trochophore of C. gigas angulate at 8 hpf were collected to record their swimming status under a microscope (Olympus BX53). Larval motility was then assessed by analyzing the microscopically recorded trajectory of the larvae described above. Briefly, the position of each larva was recorded in 1-s intervals during a time window of 10–11 s. Then, Adobe Illustrator software (Wood, 2016) was used to track the position of the larva, and the trajectory of the larva was simulated.

For SEM, the trochophore individuals were collected at 8 hpf and fixed overnight in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C and then dehydrated in 100% ethanol. After drying and coating, the observations of specimens were performed under a scanning electron microscope.

The cDNA fragment of the Cgβ-tubulin gene was generated by using the gene-specific primers (Table 1) and used to clone into the pMD18-T vector that contains the T7 promoter. The recombinant plasmid was linearized and used as templates when in vitro transcription was subsequently used to synthesize the digoxigenin-labeled probes. WMISH was performed as previously described (Wang et al., 2015) with minor modifications. Briefly, the rehydrated specimens were perforated at room temperature for 5 min with 10 μg/ml of proteinase K, followed by post-fixation with 4% PFA. The specimens were then incubated for 2 h at 65°C in the hybridization solution containing 50% formamide, 5× Denhart’s, 5× SSC, 100 μg/ml yeast tRNA, 50 μg/ml heparin, 0.1% Tween-20, followed by 16 h at 65°C in the above hybridization solution containing 1 μg/ml of denatured RNA probe. Then, the specimens were incubated at room temperature in 1× blocking buffer (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 2 h, followed by overnight incubation in an alkaline-phosphate-conjugated rabbit anti-digoxigenin antibody (Roche) at 4°C. The specimens were then extensively washed with PBST and incubated in Nitro blue tetrazolium/5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (NBT/BCIP) solution (Roche). Finally, the hybridization signals were visualized by using an Olympus BX53 microscope. In the negative control, the anti-sense probe with a final concentration of 1 μg/ml was replaced with sense probe of the Cgβ-tubulin gene.

All results were obtained from at least three independent experiments and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The main statistical test was the unpaired Student’s t-test. For experiments involving multiple comparisons, we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests or post-hoc comparisons (Tukey’s) tests. All the statistical analyses were performed using PRISM software (version 8.0.2.263). p values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

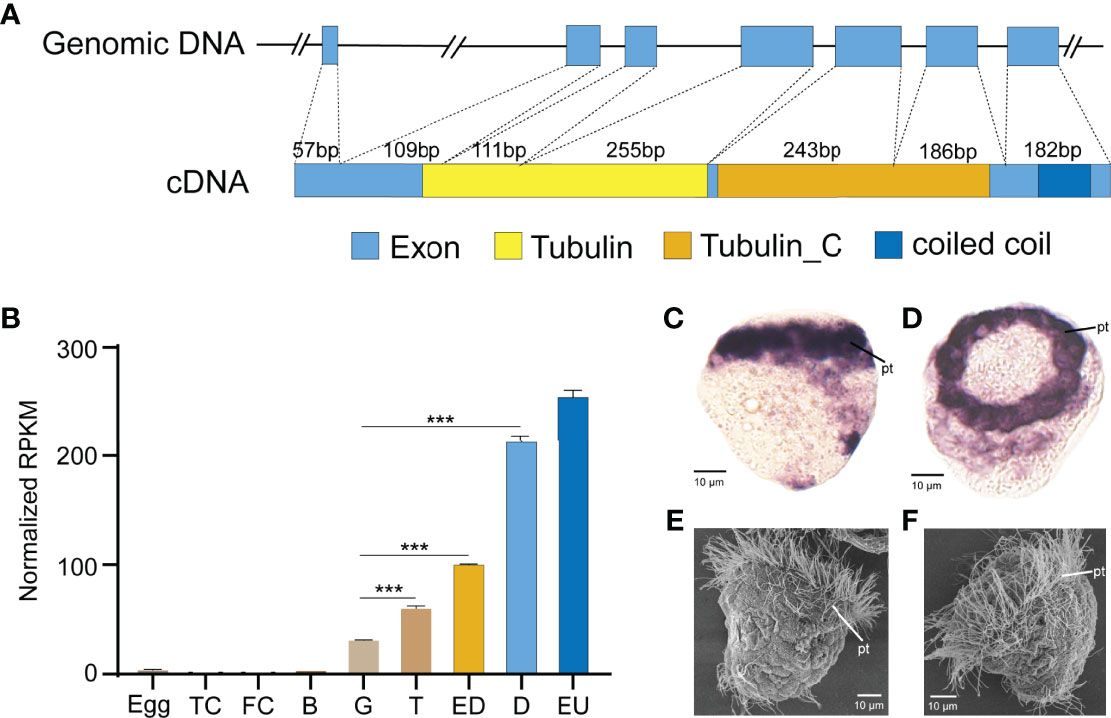

To test the approach of CRISPR/Cas9 in G0 deletion mosaic mutants, we targeted the cilia-relevant gene Cgβ-tubulin, given that the potential ciliated defect phenotypes should allow for easy visualization. Genomic DNA covering the complete coding region of Cgβ-tubulin was amplified and revealed to consist of seven exons and six introns. Cgβ-tubulin was characterized with conserved domain architecture with β-tubulin from other species, composed of Tubulin and Tubulin_C domains (Figure 2A). We next analyzed the expression patterns of Cgβ-tubulin during larval development and found that Cgβ-tubulin was significantly upregulated at gastrula and later larval stages (Figure 2B). In situ hybridization indicated that the β-tubulin gene was specifically expressed in cells localized to the prototroch of C. gigas angulate trochophore (Figures 2C, D). In summary, developmental and tissue expression patterns of Cgβ-tubulin are closely associated with the ciliated cells (Figures 2C–F).

Figure 2 Expression and gene structure of Cgβ-tubulin. (A) Structures of the genomic DNA and cDNA of Cgβ-tubulin. Seven exons and six introns in total. cDNA was predicted to encode two tubulin domains, one coiled-coil domain. (B) Expression profile of β-tubulin gene in C. gigas angulate at different developmental stages, TC, two cells; FC, four cells; B, blastula; G, gastrula; T, trochophore; D, D-shape larvae; EU, early umbo larva. Error bars represent means ± SD of three independent repeats. One-way ANOVA were used for significance analysis (three asterisks represent p < 0.001). (C, D) In situ hybridizations shows C. gigas angulate larvae at 8 hpf, which high-level expression of Cgβ-tubulin is detected in ciliated cells. (E, F) SEM shows a comparable developmental stage of C.gigas angulate larvae. pt, peritroch.

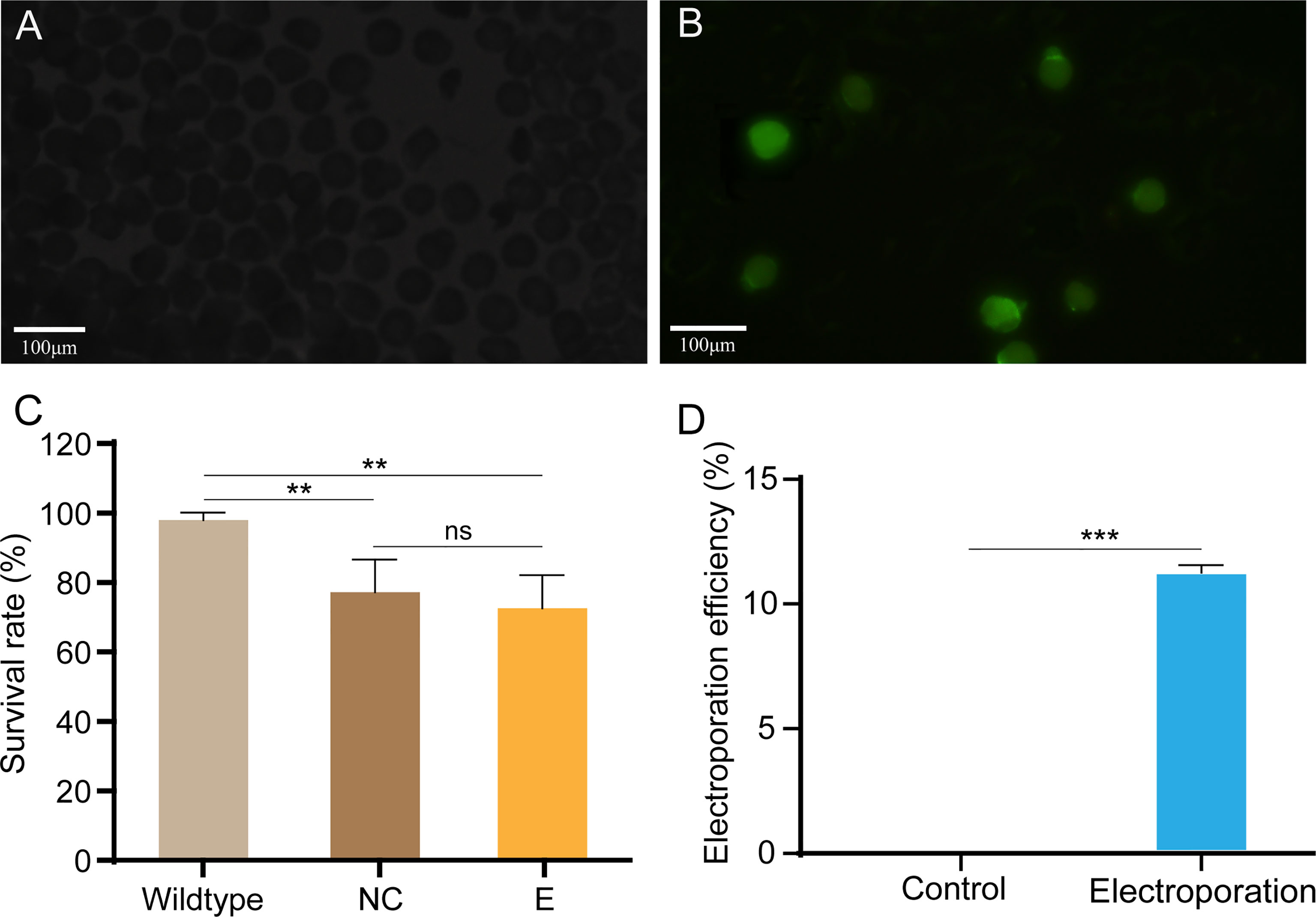

We used a standard laboratory electroporation setup to knock out Cgβ-tubulin with Lucifer yellow dye as report carrier to test the electroporation efficiency. Oyster embryos observed with green fluorescence indicated that exogenous dye had been successfully electroporated into the fertilized embryos (Figures 3A, B). We calculated the electroporation efficiency by dividing the number of embryos with fluorescence by the number of embryos. Considering that the setting of electroporation parameter has a significant impact on the survival rate and efficiency for gene delivery in the manipulated embryos, we generated multivariate experiments to determine electroporation parameters by evaluating penetrance efficiency and embryo survival rate. By comparing the results of multivariate experiments, the most balanced electroporation parameter with low voltage (40 V), long pulse duration (50 ms), and single pulse time was obtained, which not only ensured the gene delivery efficiency but also improved the survival rate of the larval. As shown in Figure 3C, compared with 98.0% in the control group without electroporation, the larval survival rates after electroporation with and without Cas9-sgRNA complex were close to 77.2% and 76.3%, respectively, which were far higher than that (0.6% and 1%) in a previous study (Jin et al., 2021). Finally, we achieved an electroporation efficiency of approximately 10% in the present study based on counting the number of embryos with green fluorescence. In brief, 100–110 embryos with green fluorescence were detected out of 1,000 embryos included in the statistics after electroporation with Lucifer yellow dye (Figure 3D and Table 2). These results suggest that the optimized parameters in this study can effectively avoid the serious impact of electroporation on larval development, and significantly improve the survival rates of oyster larvae.

Figure 3 Electroporation efficiency and survival rate of C. gigas angulate larvae after electroporation. (A, B) Early embryos electroporated with Cas9-sgRNA complex (A) or not (B). Green fluorescence was only seen in the fertilized eggs after by electroporation (caused by the fluorescent dye in the electroporation solution). (C) Survival rate of C. gigas angulate larvae after electroporation. Wild type, wild-type control; NC, wild type by electroporation without sgRNA/Cas9 complex; E, electroporation group with sgRNA/Cas9 complex. One-way ANOVA were used for significance analysis (p < 0.01, two asterisks; ns, non-significant). (D) Electroporation efficiency statistics based on fluorescent dyes. Control, electroporation without dye Lucifer Yellow; electroporation, electroporation with dye Lucifer Yellow. t-Test confirmed the significantly increased number of embryos with green fluorescence in the electroporation group (p < 0.001, three asterisks). Error bars represent means ± SD of three independent repeats.

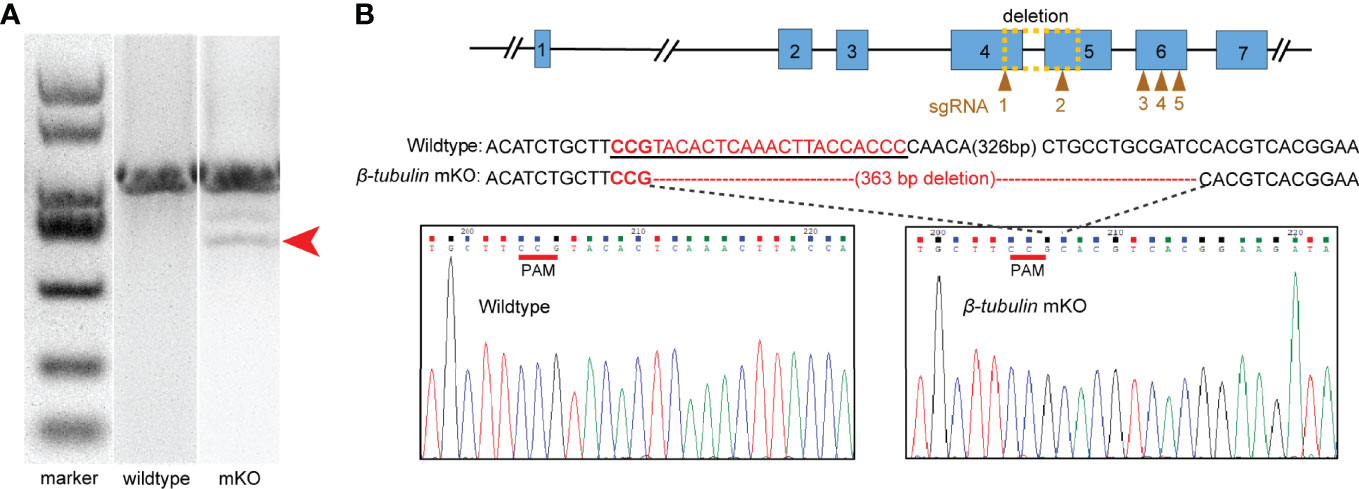

Our loss-of-function experiment aimed to produce long deletion genotypes and mosaic phenotypes in G0 generation. We designed five sgRNAs directed against Cgβ-tubulin, one targets the fourth exon, one targets the fifth exon, and the other three target the sixth exon (Figure 4B). We further assessed the efficiency of different sgRNAs by in vitro digestion of isolated Cgβ-tubulin DNA with Cas9. We found that all the five sgRNAs were effective in guiding Cas9-induced mutagenesis (Supplementary Figure S1). Among them, sgRNA1 and sgRNA2 showed high efficiency of introducing mutation, resulting in almost complete digestion of wild-type PCR bands.

Figure 4 Characterization of deleted mutations in the electroporated embryos. Embryos electroporated with Cas9-sgRNA complex were sacrificed for PCR and sequencing. (A) Fragment sizes analysis by agarose gel electrophoresis. Mutant PCR bands were detected (red arrow). (B) DNA sequence analysis showed the presence of 363 bp deletion around the Cgβ-tubulin-sgRNA-1 and Cgβ-tubulin-sgRNA-2 (yellow dotted box); sgRNA sequences are shown in the black underline, PAM sequences are shown in red underline, and the deleted nucleotides are shown in short straight lines.

We further generated Cgβ-tubulin mutants by mixing five sgRNAs with Cas9 protein and electroporating them into one-cell embryos. We aimed to identify long deletions produced by NHEJ following double-strand breaks (DSBs) because it facilitates rapid screening. Genome editing events analysis was performed in individual C. gigas angulate larvae by PCR screening of genomic DNA, analyzing fragment sizes by agarose gel electrophoresis, and cloned sequencing (Figure 4). We observed ~360 bp long deletion in the gel with the genotyping primers (Figure 4A). Sanger sequencing of TA clones (red arrow in Figure 4A) showed that mutations were frameshift mutations or in-frame mutations with long deletion, suggesting altered protein translation and disrupted gene function of Cgβ-tubulin. Further analysis demonstrated that no mutation was detected in the unelectroporated group, while the 16 truncated sequences (10%, from 160 sequences of the electroporated larvae) were all composed of long deletion mutations (100%, 363 bp deletion) (Figure 4B). These results suggested that electroporation mediated high-throughput delivery of the Cas9/sgRNA complex indeed caused mutations in the target gene Cgβ-tubulin.

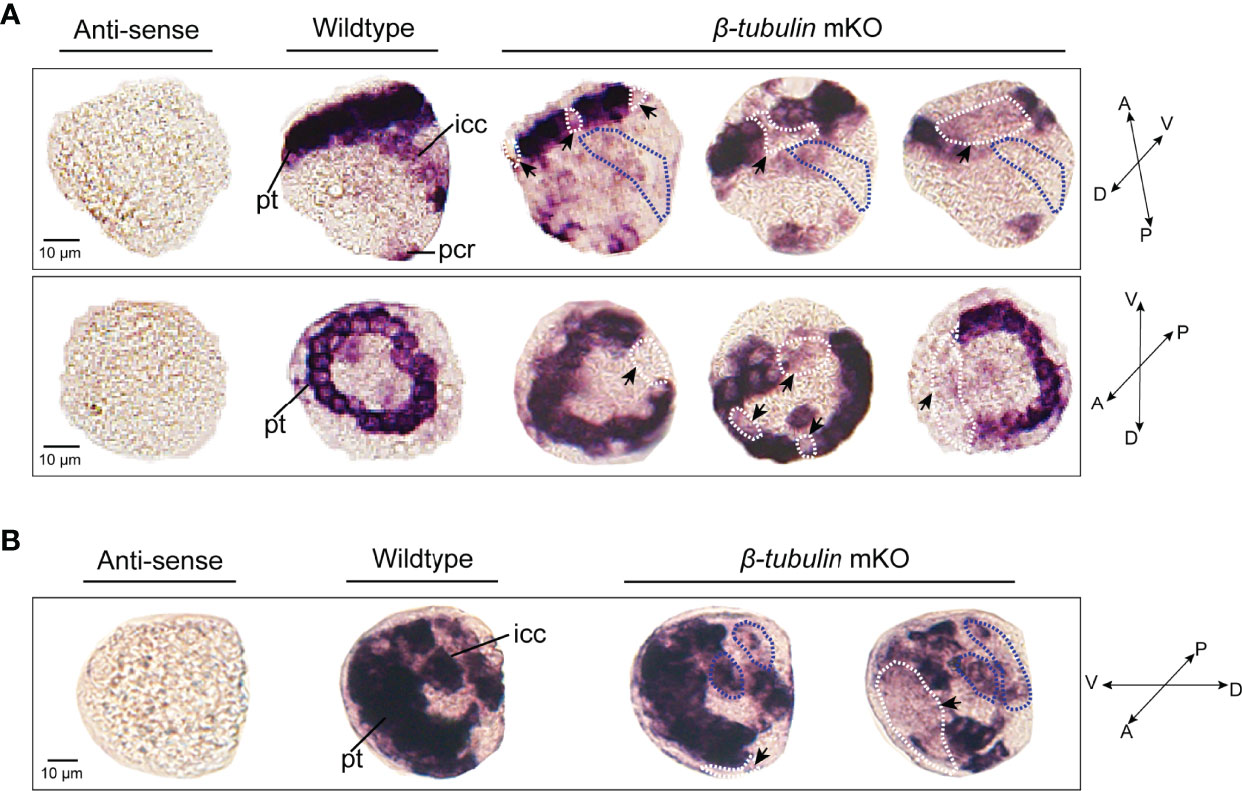

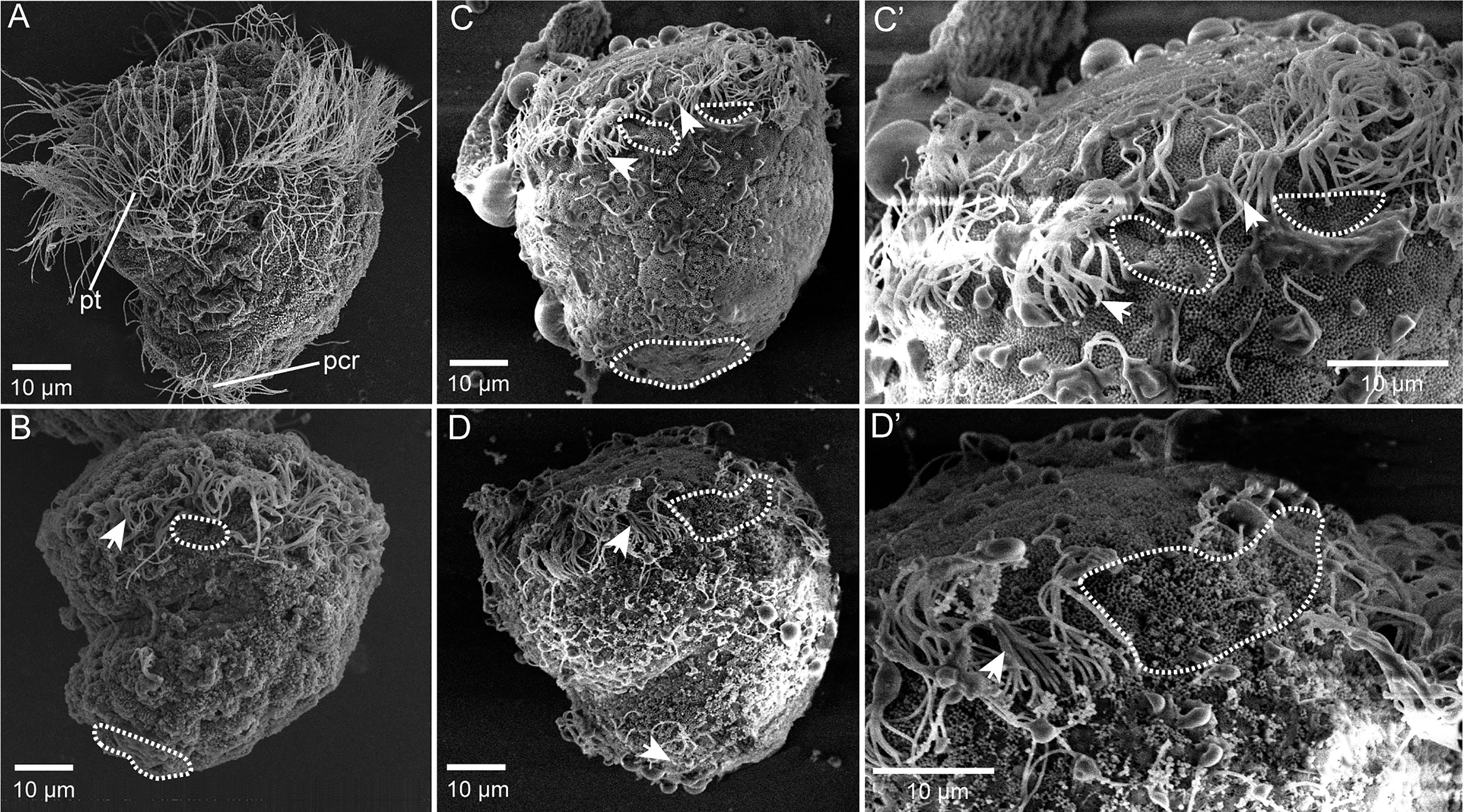

To test whether Cgβ-tubulin knockout could affect the cilia phenotypes of C. gigas angulate larvae, we performed in situ hybridization in the Cgβ-tubulin mosaic knockout larva. Multiple distinct expression patterns for Cgβ-tubulin were affected resulting from Cas9/sgRNA mosaic knockout in the trochophore and D-shaped stages of oyster larva (Figure 5). We observed that the multiple mosaic ciliary defects in the Cgβ-tubulin mosaic knockout larva (Figure 5). In details, β-tubulin knockout caused the mosaic expression patterns of Cgβ-tubulin at the positions of peritroch (Figures 5A, B, white dotted boxes and black arrows), intestinal cilia cluster (Figures 5A, B, blue dotted boxes) in the trochophore (Figure 5A) and D-shaped larvae (Figure 5B), including bilateral mosaics, which ranged in severity. Moreover, scanning electron microscopy revealed mosaic ciliary defects in the manipulated larvae including shortened (white arrows) and almost complete depleted cilia (white dotted boxes) at the positions of peritroch and the posterior cilium ring of C. gigas angulate trochophore (Figures 6B–D’). In addition, no abnormal development in other tissues of the manipulated C. gigas angulate individual was observed except for cilia shortening/depletion under ordinary light microscopy (Figure 6A).

Figure 5 Effects of β-tubulin somatic mutagenesis in C. gigas angulate larvae based on WMISH. The mosaic expression patterns of β-tubulin at the positions of peritroch (white dotted boxes) and intestinal cilia (blue dotted boxes) in C. gigas angulate trochophore (A) and D-shaped larvae (B) after Cgβ-tubulin knock out. pt, peritroch; icc, intestinal cilia cluster; pcr, posterior cilium ring; A, anterior; P, posterior; D, dorsal; V, ventral.

Figure 6 Mosaic ciliary defects in the β-tubulin knockout larvae based on SEM. (A) Wild-type control, normally developing larvae under ordinary light microscopy. pt, peritroch. (B–D’) Mosaic ciliary defects in the manipulated larvae based on the SEM data, including shortened (white arrows) and almost complete depleted cilia (white dotted boxes) at the positions of peritroch (B, C, C’, D, D’) and the posterior cilium ring (B–D) of C. gigas angulate trochophore.

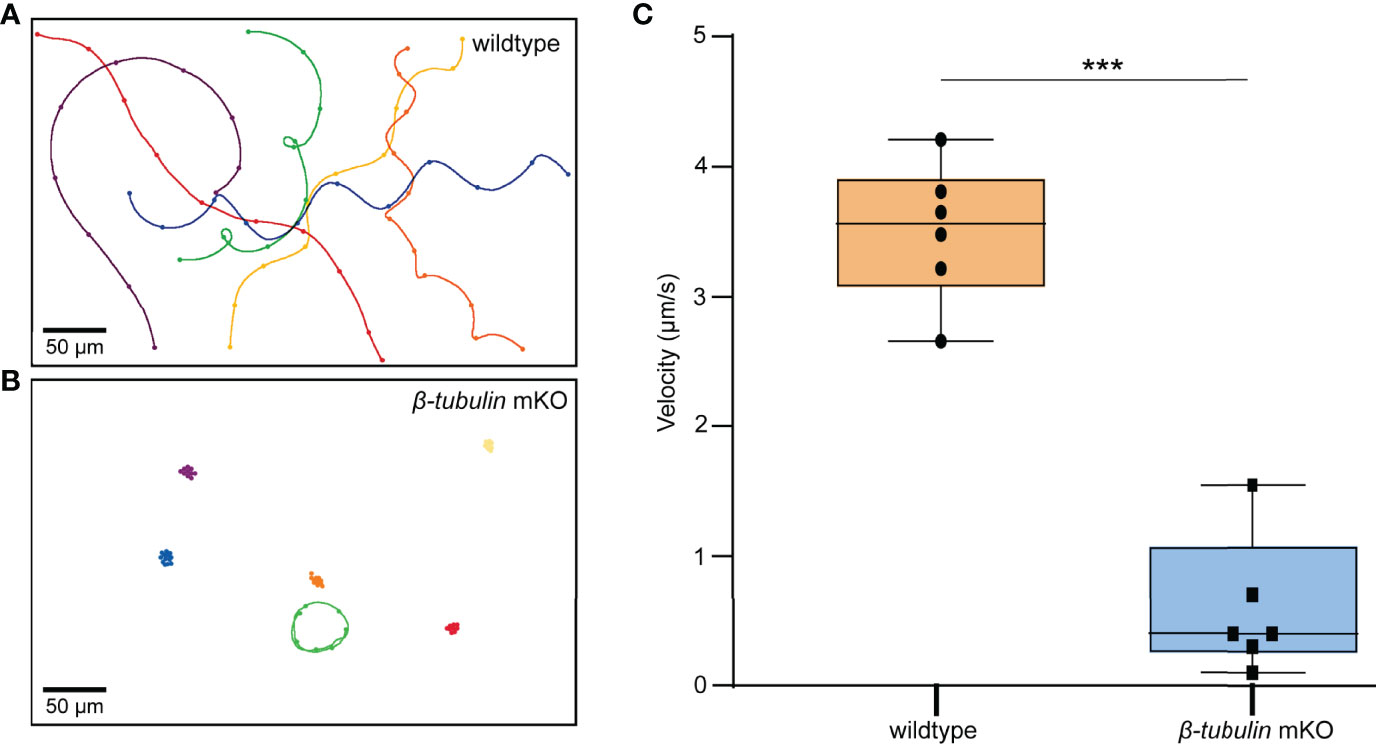

To determine whether swimming behavior was also affected in the β-tubulin knockout larvae, the trochophore of C. gigas angulate at 8 hpf were collected to perform the motility assay. The results showed that Cgβ-tubulin knockout resulted in a significant decrease in motility of C. gigas angulate larvae, especially in swimming direction and speed, compared with the wild-type larvae (Figures 7A–C, and Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). These results demonstrated that the β-tubulin gene was vital to cilia motility in C. gigas angulate larvae.

Figure 7 Motility assay in C. gigas angulate G0 larvae. Swimming trajectories of larvae (8 hpf) by electroporation with sgRNA/Cas9 complex (B) or not (A). Original microscopy videos are provided in Supplementary Video 2 (electroporation with sgRNA/Cas9 complex) and Supplementary Video 1 (electroporation without sgRNA/Cas9 complex). (C) t-test shows the significantly reduced larvae swimming velocity in the electroporation group with sgRNAs/Cas9 complex (p < 0.001, three asterisks).

In conclusion, with the use of ciliated marker gene, we demonstrate that electroporation-based CRISPR/Cas9 system can be used to generate mosaic oyster larvae with targeted deletions. This ability to generate long fragments deletion and somatic mosaics is a powerful tool in the mollusks experimental system, as it allows the rapid evaluation of candidate gene function in vivo that would be embryonically lethal in pure mutant lines.

Since the first reported application of CRISPR/Cas9 in mollusks (Perry and Henry, 2015), the applications of this technology in mollusks (including gastropods and bivalves) have been described in an increasing number of studies in recent years (Yu et al., 2019; Huan et al., 2021; Jin et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). With small size egg and embryo at a size <50 μm in diameter, electroporation was considered to be a practical, time- and labor-efficient way in molluscan CRISPR genome editing, providing a more effective method for CRISPR complex delivery in the oysters than microinjection (Yu et al., 2019; Jin et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). Still, the sustainable development of the oyster genome editing breeding system calls for establishing efficient CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis tool that generates significant defective phenotypes. In this report, we performed the CRISPR-mediated β-tubulin gene knockout by electroporation and described the long fragments deletions and mosaic mutations including defective cilia and decreased motility in the G0 larva of C. gigas angulate.

Cilium is a tubulin-based cytoplasmic extension and is thought to have functions of interrogating the extracellular environment in many biological contexts (Davenport and Yoder, 2005; Berbari et al., 2009). A large number of arranged cilia is thought to be the swimming organ of many zooplankton and larvae of aquatic protostomes, including mollusks (Nielsen, 2004; Nielsen, 2005). The tubulin subunits (β-tubulin) was considered to be required for the formation of the tubulin heterodimers, the main compounds that polymerized into microtubules and constitute the major compound of cilia in the mollusks P. vulgata (Damen and Dictus, 1994), Crepidula fornicata (Hejnol et al., 2007), and Ilyanassa obsoleta (Gharbiah et al., 2013), and in the annelid Polygordius lacteus (Woltereck, 1904) and polychaete H. elegans (Arenas-Mena et al., 2007). In our present study, a β-tubulin gene was identified in C. gigas angulate and found to be highly expressed in ciliated cells based on in situ hybridization. In present study, we used β-tubulin as a marker gene and performed CRISPR-mediated knockout by electroporation in C. gigas angulate. Through direct genotyping, long fragments deletions (363 bp) were detected in the target gene. By in situ hybridization, scanning electron microscopy, and behavioral analysis, we observed mosaic mutations including defective cilia and decreased motility in the G0 larva. This result demonstrates that Cgβ-tubulin is sufficient to mediate cilia development and swimming in larval oyster. In conclusion, with the use of ciliated marker gene, we demonstrate that electroporation-based CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis can be used to generate mosaic oyster larvae with targeted deletions and for studies of gene function in the oyster.

We optimized the parameters to improve the survival rate of oyster larvae under the premise of ensuring good perforation efficiency. Compared with the electroporation parameters (100 V, with 15 ms pulse duration and four pulses separated by 100-ms pulse interval) set by Jin et al. (2021), we reduced the voltage of electroporation to 40 V, the pulse times to 1, while the pulse time was increased to 50 ms. After optimization, the larval survival rate after electroporation with and without Cas9-sgRNA complex was close to 77.2% and 76.3% in the present study, respectively, which was far higher than that (0.6% and 1%) of Jin et al. (2021). Moreover, based on our previous experience, the higher final concentrations of Cas9-sgRNA complex tend to give larger effects and is suitable for less potentially lethal loci. In the present study, by adjusting the concentrations of Cas9-sgRNA complex, we have been able to induce mosaic mutants using as low as 30 ng/μl Cas9 and 30 ng/μl of each sgRNA in oyster larvae. Although the efficiency of successful gene editing is still low (10%, 16/160), we can still obtain a certain number of successfully edited larvae because of the large number of oyster eggs. In addition, it is worth noting that only the long fragment deletions were used to evaluate the gene editing efficiency, while the small indels mutations were ignored, which may result in a serious underestimate of editing efficiency in the present study.

Loss-of-function deletion mutations can be produced by NHEJ following DSBs. In previous studies, long deletion knockout strategies generated by two and more cut sites using multiple single-guide RNAs (co-injection of more than two sgRNAs) have been applied in a variety of species including Danio rerio (Höijer et al., 2022), Bombyx mori (Wang et al., 2013), Helicoverpa armigera (Khan et al., 2017), Vanessa cardui (Zhang and Reed, 2016), and Bicyclus anynana (Zhang et al., 2017), but not in mollusks, such as L. goshimai (Huan et al., 2021), C. gigas (Yu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021), and C. gigas angulate (Jin et al., 2021). In the present study, five sgRNAs were simultaneously used to generate long fragment deletions, as it allowed us to perform rapid screening and genotyping of mutants using PCR and conventional agarose gel electrophoresis. According to genotyping, we detected a long fragment deletion of 363 bp in the target gene, which was the longest known deletion in mollusks, and much longer than the studies in L. goshimai (<25 bp deletion), C. gigas (<30 bp deletion), and C. gigas angulate (single base substitution). This strategy of co-injecting more than two sgRNAs is a significant improvement over the difficult detection of small indels generated by single cleavage using normal agarose gels, which significantly simplifies the genome editing workflow. Moreover, the small indels often inevitably produce truncated proteins function more similar to the original protein (theoretically, in-frame mutations occurred in 33.3% of cases). The long fragment deletion at the first functional Tubulin domain of Cgβ-tubulin gene in our study could significantly increase the probability of generating truncated proteins with deletion of the remaining functional domains and cause convincing knockout phenotypes.

Genetic mosaicism is the presence of more than one genotype in one individual. Mosaicism can be produced by a variety of natural mechanisms including chromosome non-disjunction, anaphase hysteresis, endoreplication, and mutations arising during development (Taylor et al., 2014), and by manipulative mechanisms such as genome editing. In essence, target genes at different stages of embryonic development can be continuously targeted and cleaved by the CRISPR/Cas9 system, resulting in mosaic mutant individuals (Mizuno et al., 2014; Oliver et al., 2015; Xin et al., 2016). Typically, mosaicism generated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system in animal models is considered an undesirable outcome. In some cases, however, this phenomenon can be valuable. Due to the embryonic lethality of many target genes and the difficulties of maintenance and genotyping, most of our attention has been focused on analysis of mosaic G0 phenotypes. The advantages of focusing on somatic mosaicism are that data can be collected over a generation, and the phenotypic effects of lesions are limited to the subset of cell lineages with deletions, thereby reducing the harmful effects of many deletions (Zhong et al., 2015; Mehravar et al., 2019). β-Tubulin knockout mediated the mosaic expression patterns of Cgβ-tubulin, and mosaic ciliary defects were commonly found at the positions of peritroch, intestinal cilia, and the posterior cilium ring in C. gigas angulate trochophore and D-shaped larvae. Overall, we suggest that CRISPR/Cas9 can be applied to generate oyster larvae with phenotypic mosaic defects for targeted deletions. In the future, this ability to produce somatic deletion mosaics could be a powerful tool for studying oyster gene function in the mollusks experimental systems.

The application of CRISPR-mediated gene editing in marine mollusks is still facing great challenges, both in functional studies after gene knockout and in genetic engineering breeding. Here, we found that β-tubulin knockout could induce mosaic phenotypes in G0 larvae of C. gigas angulate by using electroporation, characterized by shortened/depleted cilia and decreased larval motility. Since the β-tubulin knockout phenotypes are easy to detect at very early developmental stages, it may serve as the optimal preliminary candidate gene for establishing CRISPR-based gene editing technology. In addition, our study reveals the strategy of generating long fragments deletion, and somatic mosaics are a powerful tool in the mollusks experimental system. Together, our report can provide useful reference for a widespread application of CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing technology in mollusks in the future.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conceived and designed the experiments: LZ. Performed the experiments: JC, WZ, YueX, and YuX. Data analysis: JC, WZ, and YueX. Contributed reagents/materials/computer resources: LZ. Wrote the paper: JC and LZ. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41976088) to LZ, Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB42000000) to LZ, Key Development Project of Centre for Ocean Mega-Research of Science, Chinese Academy of Science (COMS2019R01) to LZ.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank the high-performance computing center of Institute of Oceanology, CAS. We also would like to thank Fucun Wu for oyster culture support and Yuanyuan Sun for SEM help.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.912409/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | In vitro cleavage assay for testing the sgRNAs guided DNA cleavage by Cas9. WT represented the mixture of sgRNA and Cgβ-tubulin cleavage templates. SgRNA1-sgRNA5 shown the in vitro cleavage band types by Cgβ-tubulin-sgRNA1-5, respectively.

Supplementary Video 1 | Original microscopy video of larval trajectories in the wildtype group.

Supplementary Video 2 | Original microscopy video of larval trajectories in the electroporation group with sgRNAs/Cas9 complex.

Abe M., Kuroda R. (2019). The Development of CRISPR for a Mollusc Establishes the Formin Lsdia1 as the Long-Sought Gene for Snail Dextral/Sinistral Coiling. Development 146, dev175976–dev175976. doi: 10.1242/dev.175976

Ahmed N., Thompson S. (2019). The Blue Dimensions of Aquaculture: A Global Synthesis. Sci. Total Environ. 652, 851–861. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.163

Arenas-Mena C., Wong S. Y., Arandi-Forosani N. (2007). Ciliary Band Gene Expression Patterns in the Embryo and Trochophore Larva of an Indirectly Developing Polychaete. Gene Expr. Patterns 7, 544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2007.01.007

Berbari N. F., Connor A. K., Haycraft C. J., Yoder B. K. (2009). The Primary Cilium as a Complex Signaling Center. Curr. Biol. 19, 526–535. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.025

Chakrapani V., Patra S. K., Panda R. P., Rasal K. D., Jayasankar P., Barman H. K. (2016). Establishing Targeted Carp TLR22 Gene Disruption via Homologous Recombination Using CRISPR/Cas9. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 641, 242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2016.04.009

Chan J. L., Wang L., Li L., Mu K., Bushek D., Xu Y., et al. (2021). Transcriptomic Response to Perkinsus Marinus in Two Crassostrea Oysters Reveals Evolutionary Dynamics of Host-Parasite Interactions. Front. Genet. 12, 795706. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.795706

Chen H. L., Wang J., Du J. X., Si Z. X., Yang H., Xu X. D., et al. (2019). ASIP Disruption via Crispr/Cas9 System Induces Black Patches Dispersion in Oujiang Color Common Carp. Aquaculture 498, 230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.08.057

Chen Y., Wang Z., Ni H., Yong X., Chen Q., Jiang L. (2017). CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Base-Editing System Efficiently Generates Gain-of-Function Mutations in Arabidopsis. Sci. China Life Sci. 60, 520–523. doi: 10.1007/s11427-017-9021-5

Cleveland B. M., Yamaguchi G., Radler L. M., Shimizu M. (2018). Editing the Duplicated Insulin-Like Growth Factor Binding Protein-2b Gene in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss). Sci. Rep. 8, 16054. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34326-6

Damen P., Dictus W. (1994). Cell Lineage of the Prototroch of Patella Vulgata (Gastropoda, Mollusca). Dev. Biol. 162, 364–383. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1094

Davenport J. R., Yoder B. K. (2005). An Incredible Decade for the Primary Cilium: A Look at a Once-Forgotten Organelle. Am.J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 289, 1159–1169. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00118.2005

Dove M. C., O'Connor W. A. (2010). Commercial Assessment of Growth and Mortality of Fifth-Generation Sydney Rock Oysters Saccostrea Glomerata (Gould 1850) Selectively Bred for Faster Growth. Aquaculture Res. 40, 1439–1450. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2009.02243.x

Eid A., Mahfouz M. M. (2016). Genome Editing: The Road of CRISPR/Cas9 From Bench to Clinic. Exp. Mol. Med. 48, e265. doi: 10.1038/emm.2016.111

FAO. (2020). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020-Sustainability in Action (Rome: FAO). doi: 10.4060/ca9229en

Frank-Lawale A., Allen S. K., Dégremont L. (2014). Breeding and Domestication of Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea Virginica) Lines for Culture in the Mid-Atlantic, Usa: Line Development and Mass Selection for Disease Resistance. J. Shellfish Res. 33, 153–165. doi: 10.2983/035.033.0115

Gharbiah M., Nakamoto A., Nagy L. M. (2013). Analysis of Ciliary Band Formation in the Mollusc Ilyanassa Obsoleta. Dev. Genes Evol. 223, 225–235. doi: 10.1007/s00427-013-0440-1

Gui T., Zhang J., Song F., Sun Y., Xie S., Yu K., et al. (2016). CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing and Mutagenesis of EcChi4 in Exopalaemon Carinicauda. G3-Genes Genomes Genet. 6, 3757–3764. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.034082

Hejnol A., Martindale M. Q., Henry J. Q. (2007). High-Resolution Fate Map of the Snail Crepidula Fornicata: The Origins of Ciliary Bands, Nervous System, and Muscular Elements. Dev. Biol. 305, 63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.044

Höijer I., Emmanouilidou A., Östlund R., van Schendel R., Bozorgpana S., Tijsterman M., et al. (2022). CRISPR-Cas9 Induces Large Structural Variants at on-Target and Off-Target Sites In Vivo That Segregate Across Generations. Nat. Commun. 13, 627. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28244-5

Hollenbeck C. M., Johnston I. A. (2018). Genomic Tools and Selective Breeding in Molluscs. Front. Genet. 9. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00253

Houston R. D., Bean T. P., Macqueen D. J., Gundappa M. K., Robledo D. (2020). Harnessing Genomics to Fast-Track Genetic Improvement in Aquaculture. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 389–409. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-0227-y

Huan P., Cui M. L., Wang Q., Liu B. Z. (2021). CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Mutagenesis Reveals the Roles of Calaxin in Gastropod Larval Cilia. Gene 787, 145640. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2021.145640

Jin K., Zhang B., Jin Q., Cai Z., Wei L., Wang X., et al. (2021). CRISPR/Cas9 System-Mediated Gene Editing in the Fujian Oysters (Crassostrea Angulate) by Electroporation. Front. Marine Sci. 8, 763470. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.763470

Khan S. A., Reichelt M., Heckel D. G. (2017). Functional Analysis of the ABCs of Eye Color in Helicoverpa Armigera With CRISPR/Cas9-Induced Mutations. Sci. Rep. 7, 40025. doi: 10.1038/srep40025

Kim J., Cho J. Y., Kim J. W., Kim H. C., Noh J. K., Kim Y. O., et al. (2019). CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Myostatin Disruption Enhances Muscle Mass in the Olive Flounder Paralichthys Olivaceus. Aquaculture 512, 734336. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734336

Langdon E. C. (2006). Effects of Genotype × Environment Interactions on the Selection of Broadly Adapted Pacific Oysters (Crassostrea Gigas). Aquaculture 261, 522–534. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.07.022

Li M., Feng R., Ma H., Dong R., Liu Z., Jiang W., et al. (2016). Retinoic Acid Triggers Meiosis Initiation via Stra8-Dependent Pathway in Southern Catfish, Silurus Meridionalis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 232, 191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2016.01.003

Li C., Wang H. Y., Liu C. F., Li Y. W., Guo X. M. (2013). Classification and Distribution of Oysters Off Coastal Guangxi, China. Oceanologia Limnologia Sin. 5, 1318–13240.

Li M., Yang H., Zhao J., Fang L., Shi H., Li M., et al. (2014). Efficient and Heritable Gene Targeting in Tilapia by CRISPR/Cas9. Genetics 197, 591–599. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.163667

Li H., Yu H., Du S., Li Q. (2021). CRISPR/Cas9 Mediated High Efficiency Knockout of Myosin Essential Light Chain Gene in the Pacific Oyster (Crassostrea Gigas). Marine Biotechnol. 23, 215–224. doi: 10.1007/s10126-020-10016-1

Ma J., Fan Y., Zhou Y., Liu W., Jiang N., Zhang J., et al. (2018). Efficient Resistance to Grass Carp Reovirus Infection in JAM-A Knockout Cells Using CRISPR/Cas9. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 76, 206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.02.039

Mehravar M., Shirazia A., Nazaric M., Banan M. (2019). Mosaicism in CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing. Dev. Biol. 445, 156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.10.008

Melo C. M. R., Durland E., Langdon C. (2016). Improvements in Desirable Traits of the Pacific Oyster, Crassostrea Gigas, as a Result of Five Generations of Selection on the West Coast, USA. Aquaculture 460, 105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.04.017

Mizuno S., Dinh T. T. H., Kato K., Mizuno-Iijima S., Tanimoto Y., Daitoku Y., et al. (2014). Simple Generation of Albino C57BL/6J Mice With G291T Mutation in the Tyrosinase Gene by the CRISPR/Cas9 System. Mamm. Genome 25, 327–334. doi: 10.1007/s00335-014-9524-0

Momose T., Concordet J. P. (2016). Diving Into Marine Genomics With CRISPR/Cas9 Systems. Mar. Geonomics 30, 55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.margen.2016.10.003

Nielsen C. (2004). Trochophora Larvae: Cell-Lineages, Ciliary Bands, and Body Regions. 1. Annelida and Mollusca. J. Exp. Zoology Part B Mol. Dev. Evol. 302, 35–68. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.20001

Nielsen C. (2005). Trochophora Larvae: Cell-Lineages, Ciliary Bands and Body Regions. 2. Other Groups and General Discussion. J. Exp. Zoology Part B Mol. Dev. Evol. 304, 401–447. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21050

Ohama M., Washio Y., Kishimoto K., Kinoshita M., Kato K. (2020). Growth Performance of Myostatin Knockout Red Sea Bream Pagrus Major Juveniles Produced by Genome Editing With CRISPR/Cas9. Aquaculture 529, 735672. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020

Oliver D., Yuan S., McSwiggin H., Yan W. (2015). Pervasive Genotypic Mosaicism in Founder Mice Derived From Genome Editing Through Pronuclear Injection. PloS One 10, e0129457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129457

Pernet B. (2018). “Larval Feeding: Mechanisms, Rates, and Performance in Nature,” in Evolutionary Ecology of Marine Invertebrate Larvae. Eds. Carrier T. J., Reitzel A. M., Heyland A. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), Pp. 87–102.

Perry K. J., Henry J. Q. (2015). CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Genome Modification in the Mollusc, Crepidula Fornicata. Genesis 53, 237–244. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22843

Rawson P., Lindell S., Guo X., Sunila I. (2010). Cross-Breeding for Improved Growth and Disease Resistance in the Eastern Oyster. NRAC Publication No. 206-2010. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247778319.

Riviere G., He Y., Tecchio S., Crowell E., Gras M., Sourdaine P., et al. (2017). Dynamics of DNA Methylomes Underlie Oyster Development. PloS Genet. 13, e1006807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006807

Simora R., Xing D., Bangs M. R., Wang W., Dunham R. A. (2020). CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Knock-in of Alligator Cathelicidin Gene in a Non-Coding Region of Channel Catfish Genome. Sci. Rep. 1, 22271. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79409-5

Song K., Li Y., Huang B., Li L., Zhang G. (2017). Genetic and Evolutionary Patterns of Innate Immune Genes in the Pacific Oyster Crassostrea Gigas. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 77, 17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.07.012

Straume A. H., Kjærner-Semb E., Kai O. S., Güralp H., Edvardsen R. B. (2020). Indel Locations are Determined by Template Polarity in Highly Efficient In Vivo CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated HDR in Atlantic Salmon. Sci. Rep. 10, 409. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57295-w

Taylor T. H., Gitlin S. A., Patrick J. L., Crain J. L., Wilson J. M., Griffin D. K. (2014). The Origin, Mechanisms, Incidence and Clinical Consequences of Chromosomal Mosaicism in Humans. Hum. Reprod. Update 20, 571–581. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu016

Wang Q., Li Q., Kong L., Yu R. (2012). Response to Selection for Fast Growth in the Second Generation of Pacific Oyster (Crassostrea Gigas). J. Ocean Univ. China 2012, 413–418. doi: 10.1007/sl1802-012-1909-7

Wang X., Liu B., Liu F., Huan P. (2015). A Calaxin Gene in the Pacific Oyster Crassostrea Gigas and its Potential Roles in Cilia. Zoological Sci. 32, 419–426. doi: 10.2108/zs150009

Wang Y., Li Z., Xu J., Zeng B., Ling L., You L., et al. (2013). The CRISPR/Cas System Mediates Efficient Genome Engineering in Bombyx Mori. Cell Res. 23, 1414–1416. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.146

Woltereck R. (1904). Beiträge Zur Praktischen Analyse Der PolygordiusEntwicklung Nachdem “Nordsee-” Und Dem “Mittelmeer-Typus”. Dev. Genes Evol. 18, 377–403. doi: 10.1007/BF02162440

Xin L., Min L., Bing S. (2016). Application of the Genome Editing Tool CRISPR/Cas9 in Non-Human Primates. Zool. Res. 37, 241. doi: 10.13918/j.issn.2095-8137.2016.4.214

Yue C., Li Q., Yu H. (2018). Gonad Transcriptome Analysis of the Pacific Oyster Crassostrea Gigas Identifies Potential Genes Regulating the Sex Determination and Differentiation Process. Mar. Biotechnol. 20, 206–219. doi: 10.1007/s10126-018-9798-4

Yu H., Li H., Li Q., Xu R., Yue C., Du S. (2019). Targeted Gene Disruption in Pacific Oyster Based on CRISPR/Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein Complexes. Mar. Biotechnol. 21, 301–309. doi: 10.1007/s10126-019-09885-y

Zhang G., Fang X., Guo X., Li L., Luo R., Xu F., et al. (2012). The Oyster Genome Reveals Stress Adaptation and Complexity of Shell Formation. Nature 490, 49–54. doi: 10.1038/nature11413

Zhang L., Martin A., Perry M. W., Van D., Matsuoka Y., Monteiro A., et al. (2017). Genetic basis of melanin pigmentation in butterfly wings. Genetics 205, 1537–1550. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.196451

Zhang L., Reed R. D. (2016). Genome Editing in Butterflies Reveals That Spalt Promotes and Distal-Less Represses Eyespot Colour Patterns. Nat. Commun. 7, 11769. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11769

Zhong H., Chen Y., Li Y., Chen R., Mardon G. (2015). CRISPR-Engineered Mosaicism Rapidly Reveals That Loss of Kcnj13 Function in Mice Mimics Human Disease Phenotypes. Sci. Rep. 5, 8366. doi: 10.1038/srep08366

Keywords: mosaic mutagenesis, CRISPR/Cas9, long deletion, gene editing, gene knockout, aquaculture breeding

Citation: Chan J, Zhang W, Xu Y, Xue Y and Zhang L (2022) Electroporation-Based CRISPR/Cas9 Mosaic Mutagenesis of β-Tubulin in the Cultured Oyster. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:912409. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.912409

Received: 05 April 2022; Accepted: 27 April 2022;

Published: 26 May 2022.

Edited by:

Yuehuan Zhang, South China Sea Institute of Oceanology (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Xiaotong Wang, Ludong University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Chan, Zhang, Xu, Xue and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Linlin Zhang, bGlubGluemhhbmdAcWRpby5hYy5jbg==

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.