94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci., 31 March 2022

Sec. Marine Evolutionary Biology, Biogeography and Species Diversity

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.875308

This article is part of the Research TopicEcological and Genetic Insights into Seaweeds’ Diversity and AdaptationView all 7 articles

Hongyan Zheng1,2,3

Hongyan Zheng1,2,3 Yan Xu1,2,3

Yan Xu1,2,3 Dehua Ji1,2,3

Dehua Ji1,2,3 Kai Xu1,2,3

Kai Xu1,2,3 Changsheng Chen1,2,3

Changsheng Chen1,2,3 Wenlei Wang1,2,3*

Wenlei Wang1,2,3* Chaotian Xie1,2,3*

Chaotian Xie1,2,3*Increasing global temperatures have seriously affected the sustainable development of Neoporphyra haitanensis cultivation. Although several pathways are reported to be involved in the response of N. haitanensis to heat stress, it is unknown which ones are activated by signal transduction. Previously, we detected a large influx of calcium ions (Ca2+) in N. haitanensis under heat stress. In this study, we further investigated the specificity of Ca2+ signaling and how is it transduced. Transmission electron microscopy and Fv/Fm analyses showed that the Ca2+ signal derived from extracellular Ca2+ formed at the early stage of the response to heat stress, and the signal was recognized and decoded by N. haitanensis calmodulin (NhCaM). In yeast two-hybrid assays, DnaJ, a voltage-dependent anion channel, and a bromodomain-containing protein interacted with PhCaM1 in vivo. The transcript levels of the genes encoding these proteins increased significantly in response to heat stress, but decreased upon inhibition of NhCaM1, indicating that these interacting factors were positively related to NhCaM1. Additionally, a comparative transcriptome analysis indicated that Ca2+ signal transduction is involved in phosphatidylinositol, photosystem processes, and energy metabolism in N. haitanensis under heat stress. Our results suggest that Ca2+-CaM plays important roles in signal transduction in response to heat stress in N. haitanensis.

Global climate change-driven increases in seawater temperature seriously affect the sustainable development of Neoporphyra/Neoporphyra, which has the highest commercial value per unit mass (approximately $523 per wet metric ton) among all cultivated seaweed species (FAO, 2017). Neoporphyra haitanensis, a typical warm temperate zone species originally found in Fujian Province, is widely cultivated along the coast of South China. The output of N. haitanensis reached 150,000 tons (dry weight) in 2020 in China (China Fishery Bureau, 2021). Due to importantly economic and ecologic value, the market for this commodity is likely to increase dramatically in the future. However, N. haitanensis farms are often affected by sustained high temperatures that are induced by the ‘temperature rebound’ in autumn (Xu et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2020), especially in 2021 (unpublished). Persistent high temperatures make thalli susceptible to disease, premature aging, and eventual decay, leading to a significant drop in yield (Yan et al., 2009). Therefore, studying the molecular mechanisms of the response to heat stress and cultivating new heat-tolerance varieties are necessary.

Previous studies have indicated that the thalli of N. haitanensis resist high temperatures by inhibiting photosynthesis, protein synthesis, and energy metabolism to reduce unnecessary energy consumption, which in turn facilitates the rapid establishment of acclimatory homeostasis (Xu et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2021). Accordingly, the response to heat stress in N. haitanensis involves multiple stress resistance pathways. However, little is known about how these resistance pathways are activated. The calcium ion (Ca2+) is an astonishingly versatile signaling molecule that is poised at the core of a sophisticated network of signaling pathways (Dodd et al., 2010). Transient, sustained, or oscillatory rises in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration serve as a second messenger (McAinsh and Pittman, 2009; Thor, 2019). Our previous study found that heat stress significantly increased Ca2+ influx, while the expression level of heat shock proteins (HSPs) genes (HSP22 and HSP70) showed downregulated after the Ca2+ influx was inhibited by verapamil, indicating that the Ca2+ signal generated by the plasma membrane Ca2+ channel is crucial for N. haitanensis responses to heat stress (Zheng et al., 2020). However, the temporal specificity of calcium signaling is unclear in N. haitanensis under heat stress.

Furthermore, the information encoded within these transient changes in Ca2+ contents is decoded and transmitted by a toolkit of Ca2+-binding proteins that regulate transcription via Ca2+-responsive promoter elements and regulate proteins via phosphorylation (Dodd et al., 2010). Calmodulins (CaMs) is a universal Ca2+ sensor among eukaryotes (Rhoads and Friedberg, 1997). As a downstream target protein of Ca2+, CaM acts as an intermediary in Ca2+-mediated reactions, and regulates physiological and biochemical processes in cells by binding to intracellular enzymes or proteins. In this way, CaM plays an important role in cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, and participates in signal transduction of abiotic stress stimuli (Pawar et al., 2008). Our previous study suggested that CaM could act as a Ca2+ signal decoding protein in N. haitanensis in response to heat stress (Zheng et al., 2020). However, CaM has neither transcription factor nor enzyme activity, nor does it serve as a structural protein. Instead, it is the downstream CaM-binding proteins that regulate physiological functions. Therefore, identifying the proteins that interact with CaM is an important way to reveal the physiological function of CaM, and is the key to deciphering the Ca2+-CaM signal transduction system in N. haitanensis under heat stress.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to 1) investigating the temporal specificity of the Ca2+ signaling response to heat stress by comparing the quantum yield (Fv/Fm) of thalli in seawater with that of thalli in Ca2+-free seawater, and by observing the distribution of Ca2+ by scanning electron microscopy; 2) identifying proteins that interact with NhCaM by yeast two-hybrid analyses; 3) determining which pathways were activated downstream of Ca2+ signaling under heat stress through transcriptome analysis. The present results provide new insights into the signal transduction mechanism of N. haitanensis under heat stress.

The heat-resistant strain Z-61 of N. haitanensis (Chen et al., 2008) was selected and purified by the Laboratory of Germplasm Improvements and Applications of Neoporphyra at Jimei University, Fujian, China. For the control, Z-61 thalli were cultured in natural seawater supplemented with Provasoli’s enriched seawater medium at 21°C under a 10-h light/14-h dark photoperiod [50-60 μmol (m−2 s−1)]. The growth medium was refreshed every 2 days.

The seawater temperature exceeds 30°C during ‘temperature rebound’ in autumn, the season of the cultivation of N. haitanensis. Thus, in order to screening heat treatment condition, the Fv/Fm of the thallus was detected at six temperatures (30°C, 32°C, 34°C, 36°C, 38°C, 40°C). The results showed that Fv/Fm of the thalli had no change at 30°C for 48 h, while it decreased significantly at 1 h of 34°C - 40°C. However, Fv/Fm of thalli at 32°C showed no significant change within 12 h, but decreased rapidly after 12 h (Figure S1). Therefore, we selected 32°C as heat stress condition to investigate signal transduction that usually occurred at the early stage of stress. Healthy thalli with a length of (15 ± 1) cm were selected for heat treatment (32°C), and each group had three biological replicates. The composition of artificial seawater, in g/L, was as follows: NaCl 26.73, MgCl 2.26, MgSO4 3.25, CaCl2 1.15, NaHCO3 0.2, KCl 0.72, NaBr 0.058, H3BO3 0.058, Na2SiO3 0.0035, KAl (SO4) 2·12H2O 0.023, LiNO3 0.0013, NH4H2PO4 0.0040. For Ca2+-free seawater, CaCl2 was omitted.

A Diving Pulse Amplitude Modulation fluorometer (Diving-PAM, Walz, Effeltrich, Germany) was used to measure the ratio of variable chlorophyll fluorescence to maximal chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm). Thalli were acclimated in darkness for 10 min, and then chlorophyll fluorescence was measured using a slightly modified version of a previously published method (Yu and Guy, 2004).

The method of transmission electron microscope analyses was a slight modification on the basis of publication by Ouyang et al. (2011). A 1 cm2 piece blade was cut from the middle of the thallus and fixed for 6–10 h in 2.5% glutaraldehyde + 2% paraformaldehyde fixative dissolved in 0.2% potassium pyroantimonate buffer (pH 7.6). The sample was washed three times with 2% potassium pyroantimonate phosphate buffer for 20 min each time. Then, the sample was fixed in 1% osmium and 2% potassium pyroantimonate phosphate buffer at room temperature in the dark for 7 h. The sample was washed three times with 2% potassium pyroantimonate phosphate buffer solution for 15 min each time, and then washed three times with 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution for 15 min each time. Dehydration, infiltration, embedding, and slicing were carried out using established methods.

Through searches of sequences at the NCBI database, NhCaM1 was screened out from the transcriptome of N. haitanensis. The full-length NhCaM1 sequence was cloned by 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE) using the SMART RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Multiple amino acid alignments were performed using Clustal X, and phylogenetic trees were constructed by the maximum likelihood method using MEGA6.0 software (Tamura et al., 2013).

Purified RNA (1 μg) was used as the template for synthesizing cDNA with the PrimeScript 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). The cDNA solutions were diluted to 5 ng μL−1 with nuclease-free water for subsequent quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR assays using the Step One Plus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (Takara). The gene encoding ubiquitin conjugating enzyme (UBC) was used as an internal control (Li et al., 2014) The PCR procedure was that recommended by the manufacturer. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

The yeast two-hybrid assay was performed using the Clontech Yeast Two-Hybrid System (pGBKT7 and pGADT7). The full-length NhCaM1 sequence was cloned into pGBKT7. The negative controls were the pGBKT7-LAM control vector and the pGADT7-T control vector. The pGBKT7-53 control vector and pGADT7-T control vector were used as positive controls for self-activation and toxicity tests of decoy genes. The positive blue clones on SD/-Trp/-Leu/X-α-Gal/AbA plates were transferred to SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade/X-α-Gal/AbA medium for rigorous screening. Blue positive clones were selected for one-to-one verification. The transcript levels of the interacting genes were detected under heat stress (32°C) and after treatment with the CaM inhibitor trifluoperazine (TFP) at 8 M.

N. haitanensis thalli were incubated with 100 μM verapamil, an inhibitor of Ca2+ channels, for 2 h before heat treatment (32°C). After 15 min of heat treatment, total RNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A. plant RNA Kit (OMEGA Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA). Seaweeds cultured in normal seawater served as the CK. Thalli were also cultured in Ca2+-free seawater under heat stress for 15 min and 3 h. Three biological samples were collected for each experimental group. De novo transcriptome assembly and annotation were completed by GENE DENOVO Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). The transcript level of genes was calculated based on reads per kb per million reads (RPKM) values. Differentially expressed genes were identified by comparing RNA-seq data between groups and between samples using DESeq2 and edger software (Robinson et al., 2010; Love et al., 2014), respectively. Genes showing two-fold changes were scored as differentially expressed on the basis of a false-discovery rate of 0.05. BlastX was used to compare unigene sequences with those in protein databases NR, SwissProt, KEGG, and COG/KOG (e value<0.00001), and functional annotation information for the most similar proteins was assigned to unigenes.

Data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance. Differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05. Unless otherwise indicated, all reported P-values refer to the results of one-way ANOVA followed by least significant difference (LSD) tests.

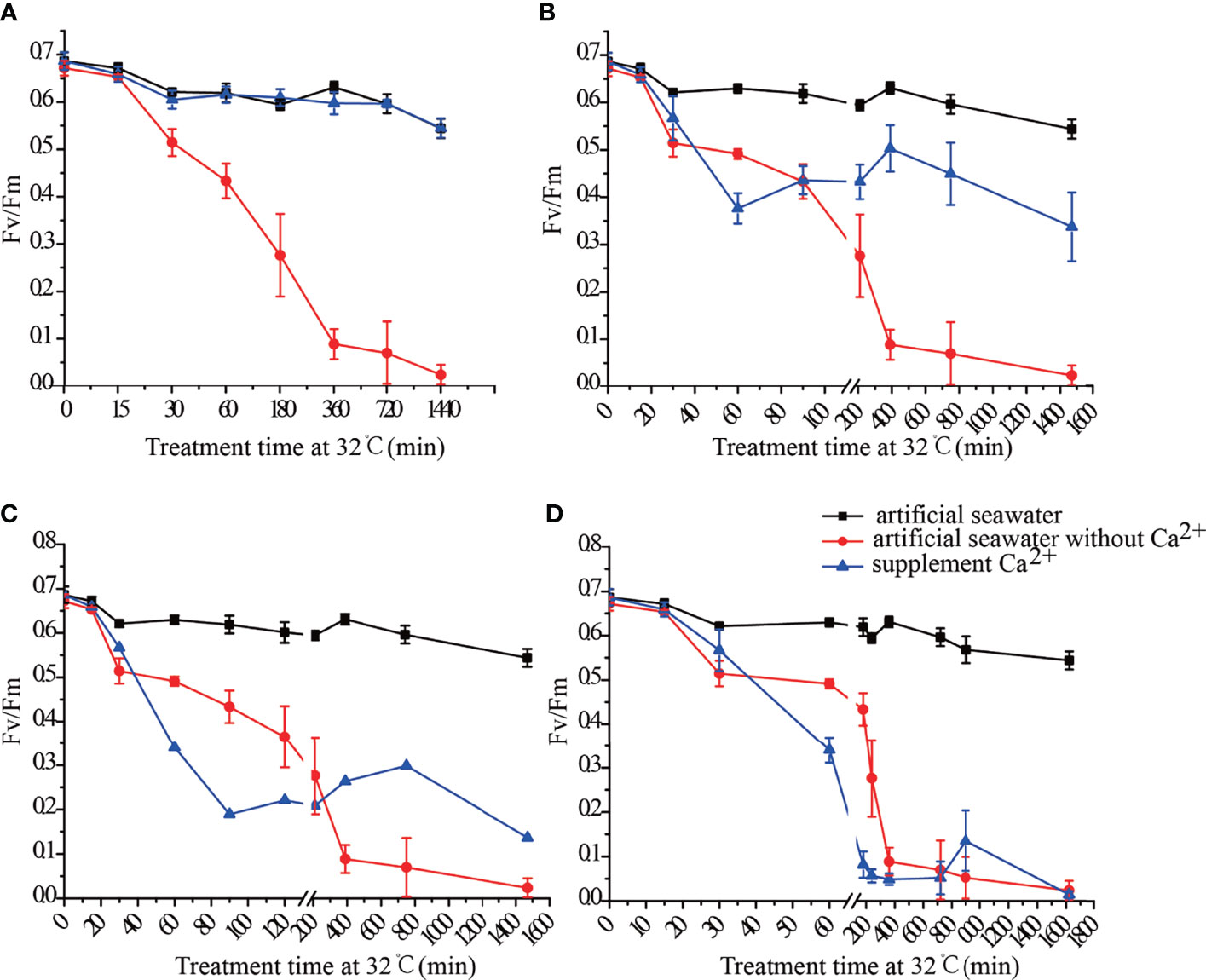

When Ca2+ was added into artificial seawater without Ca2+ at 15 min of the heat treatment, the thalli Fv/Fm values were restored to the normal level (Figure 1A). When Ca2+ was added into artificial seawater without Ca2+ at 30 min and 1 h of the heat treatment, the Fv/Fm values of the thalli recovered somewhat, but did not return to the normal levels (Figures 1B, C). The addition of Ca2+ into artificial seawater without Ca2+ at 3 h of the heat treatment did not improve the heat resistance of thalli, and the Fv/Fm value decreased to 0.1 (Figure 1D).

Figure 1 Fv/Fm of N. haitanensis thalli after adding Ca2+ at 15 min (A), 30 min (B), 1 h (C) and 3 h (D) of heat treatment.

Under heat stress, the growth of thalli stagnated, and those in the Ca2+-free seawater began to bleach and decay. This was indicative of severe damage to pigments and photosystems. Thalli in the Ca2+-free seawater became transparent by 36 h of heat stress. Lesions did not appear until 24 h of heat treatment in artificial seawater (Figures S2A–E). After disinfection, thalli were cultured in natural seawater, artificial seawater, or Ca2+-free seawater at 22°C. Within 12 h, there was no difference in Fv/Fm between thalli cultured in natural seawater and those cultured in artificial seawater, while the Fv/Fm values were decreased slightly in thalli cultured in Ca2+-free seawater (Figure S2F). Under heat stress (32°C), the thalli cultured in both natural seawater and artificial seawater showed slightly decreased Fv/Fm values, while those cultured in Ca2+-free seawater showed a sharp decrease in Fv/Fm, dropping to less than 0.1 after 12 h. The thalli were on the point of death at 12 h of heat treatment in Ca2+-free seawater (Figure S2F).

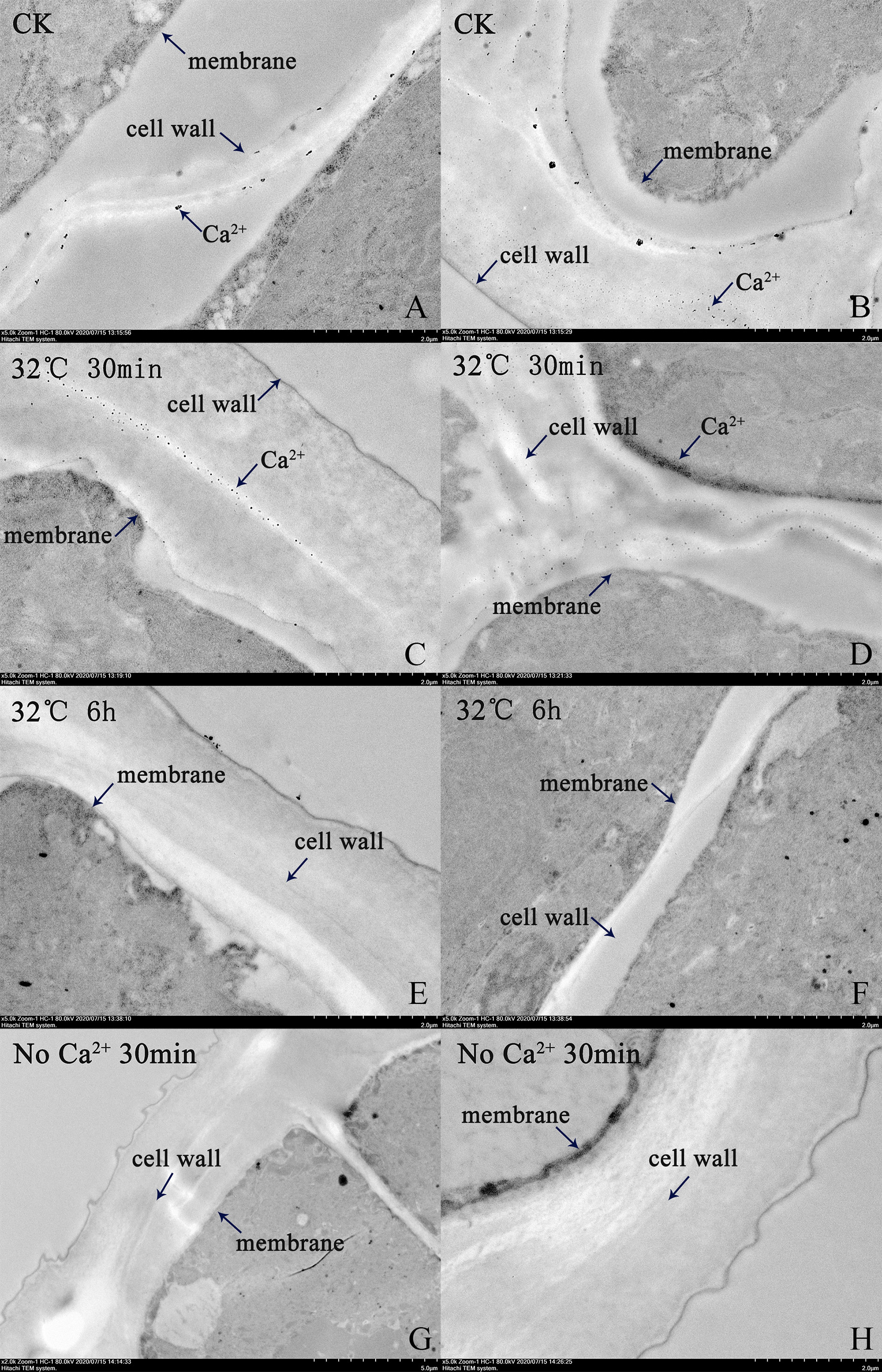

At 30 min of heat stress, a large amount of Ca2+ was present in the cell wall, cell membrane, and cell interior (Figures 2A, D). At 6 h of heat stress, no Ca2+ was present in the cell wall or cell membrane (Figures 2E, F). In the thalli cultured in Ca2+-free seawater, fewer Ca2+ aggregates were present in the cell wall and cell membrane, but Ca2+ was distributed inside the cell (Figures 2G, H).

Figure 2 Transmission electron micrographs showing distribution of Ca2+ in N. haitanensis thalli under heat stress. (A, B) Control group. (C, D) Heat treatment for 30 min. (E, F) Heat treatment for 6 h. (G, H) Heat treatment for 30 min in Ca2+-free seawater.

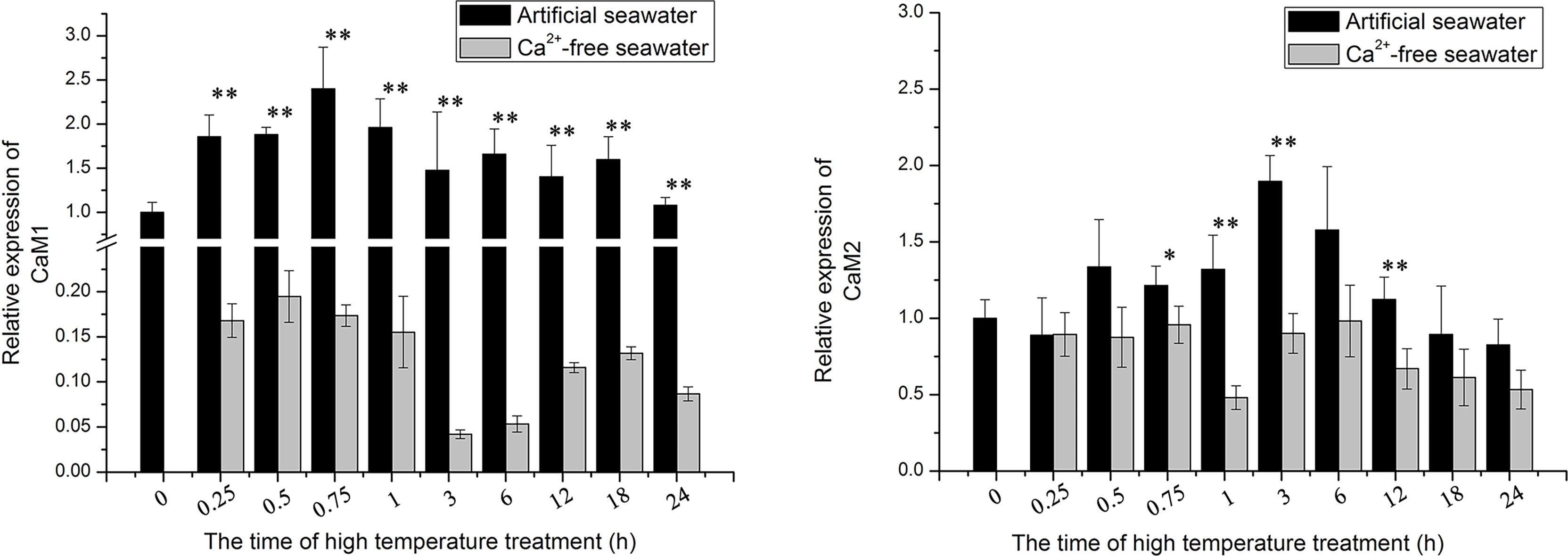

The transcript levels of genes encoding CaM1 and CaM2 were detected in thalli cultured in seawater and Ca2+-free seawater under heat stress (32°C) for 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 18 h, and 24 h. Under heat stress, the transcript levels of genes encoding CaM1 and CaM2 were up-regulated, and CaM1 was up-regulated earlier than CaM2. In the thalli cultured in Ca2+-free seawater, the expression of these genes was inhibited to varying degrees (Figure 4). To explore the regulation of NhCaM during the response of N. haitanensis to heat stress, we isolated a 450-bp sequence of NhCaM1 (Figure S3). A BLAST analysis revealed that the protein encoded by this gene contained four ‘EF-hand’ domains, which are characteristic of CaM proteins in other species and are involved in binding Ca2+. On the basis of these findings, we speculated that this gene encodes CaM in N. haitanensis, so it was designated as NhCaM1. This sequence has been submitted to the GenBank database under the accession number KU179277. Analyses using ExPASy ProtParam indicated that NhCaM1 encodes a protein consisting of 149 amino acids with the formula C723H1138N184O253S11, a theoretical molecular weight of 16.8 kDa, and a theoretical isoelectric point 4.09. The protein was predicted to have 14 positively charged amino acid residues (Arg and Lys), 38 negatively charged amino acid residues (Asp and Glu), an instability coefficient of 36.43, and a GRAVY score of 0.543. The results showed that NhCaM1 is stable and hydrophilic. Swiss-Model was used to predict the third-order spatial structure of NhCaM1. No signal peptides or transmembrane domain sequences were found by PrediSi, but three serine and three threonine residues were identified as potential phosphorylation sites by TMHMM.NetPhos2.0. Additionally, the expression of NhCaM1 and NhCaM2 showed down-regulation in Ca2+-free seawater under heat stress (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Transcript levels of NhCaM in N. haitanensis at different times under heat stress. * and ** represent significant difference (P < 0.05) and extremely significant difference (P<0.01) between the same time point in different treatment groups, respectively.

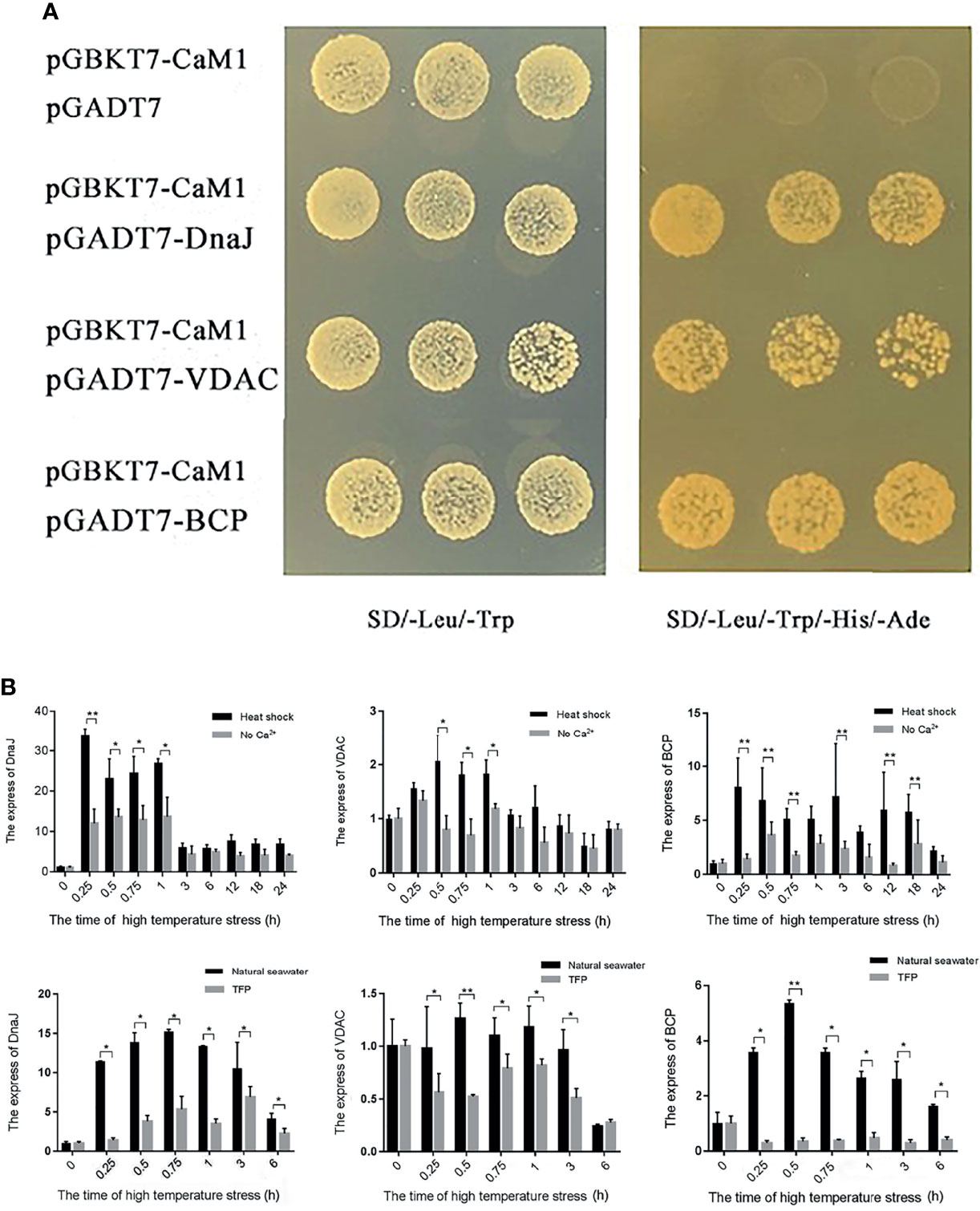

The full-length ORF of PhCaM1 was cloned into the pGBKT7 bait vector to screen the P. haitanensis Y2H cDNA library under heat stress conditions. Before screening, the autoactivation and toxicity of the clone were tested in yeast. The yeast cells harboring the PhCaM1 clone grew slightly and remained blue on SD/-Leu/-Trp/-his/x-α-gal medium, but not on SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade/X-α-gal/AbA medium, confirming that pGBKT7-CaM1 had no autoactivation in these Y2H Gold yeast strains. 30 positive clones were obtained by screening the library three times, and 25 clones were successfully sequenced after removing failures of PCR amplification and sequencing. 7 sequences of these 25 sequences can be annotated. Thus, these annotated 7 sequences were selected for one-to-one validation. After BLAST comparisons at the NCBI, three had annotations: DnaJ (also referred to as HSP40), the voltage-dependent anion-selective channel (VDAC), and a bromodomain-containing protein (BCP) (Figure 4A). Additionally, we detected up-regulation of DnaJ, VDAC, and BCP under heat stress, especially at the early stage of the response. Treatment with TFP resulted in down-regulation of all three genes, as did culturing of thalli in in Ca2+-free seawater (Figure 4B).

Figure 4 Screening for NhCaM1 interaction partners by yeast two-hybrid analysis, and gene transcript levels in thalli of N. haitanensis under different treatments. (A) Screening for proteins that interact with NhCaM1 in N. haitanensis under heat stress by yeast two-hybrid analysis; (B) Transcript levels of genes encoding proteins that interact with NhCaM1 in N. haitanensis thalli under different treatments. TFP: trifluoperazine, a CaM inhibitor. * and ** represent significant difference (P< 0.05) and extremely significant difference (P<0.01) between the same time point in different treatment groups, respectively.

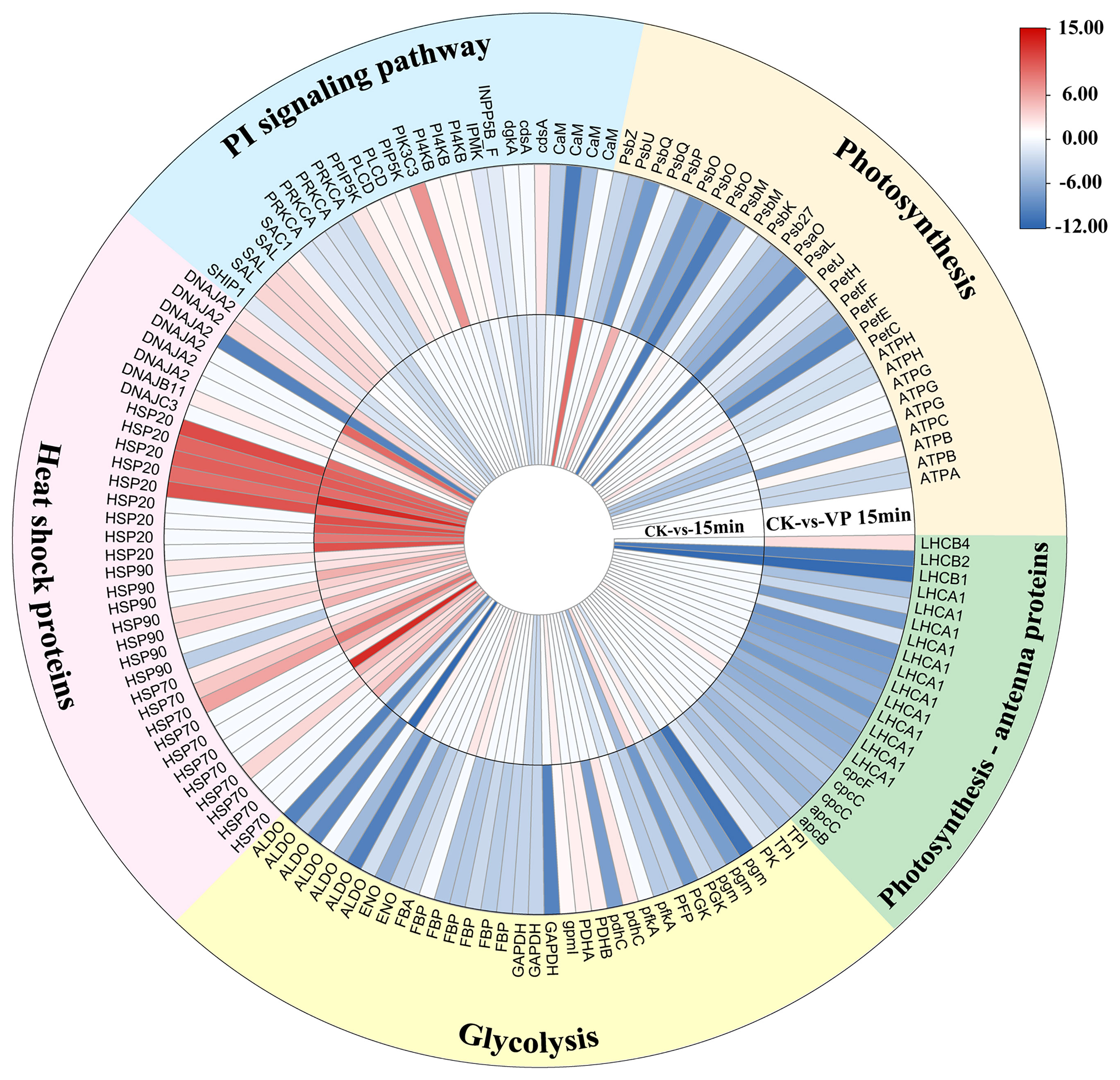

At 15 min of heat treatment, 1,747 genes were up-regulated and 2,273 genes were down-regulated, while at 15 min after verapamil treatment, 3,904 genes were up-regulated and 5,021 genes were down-regulated (Figure S4). Further analysis showed that three CaM genes was down-regulated by inhibition of Ca2+ channels by verapamil, while one gene was up-regulated under heat stress (Figure 5). The transcript levels of 24 of 34 DEGs encoding HSPs, including five HSP40 (DnaJ) genes, six HSP20 genes, four HSP90 genes, nine HSP70 genes, were also up-regulated in thalli at 15 min of heat treatment, while the expressions of these genes were inhibited by verapamil. Whereas, the increases in the transcript levels of three HSP20 genes, two HSP 70, two HSP40, and one HSP90 gene were higher after inhibition of Ca2+ influx than in the heat treatment. Transcripts of key genes related to phosphatidylinositol signaling, mainly including three phosphodylinositol 4-kinase (PI4K) genes, two phospholipase C (PLC) genes, two phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase (PIP5K) genes, one phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) gene, were not detected or down-regulated at 15 min of heat treatment, but they were significantly up-regulated in thalli treated with verapamil. Compared to 15 min heat treatment, the transcript levels of 26 of 35 genes encoding enzymes involved in glycolysis, such as glucose phosphate mutase (PGM), fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase place (FBP), fructose diphosphate aldolase (ALDO), triose phosphate isomerase (TPI), and glyceric acid phosphate kinase (PGK), were down-regulated in thalli treated with verapamil. In addition, the genes encoding components of the photosynthetic system were also significantly down-regulated in the thalli treated with verapamil (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Differentially expressed genes between untreated N. haitanensis thalli and thalli treated with verapamil under heat stress. CK, control (the thalli at normal condition); 15min, the thalli at 15 min heat treatment; VP15min, the thalli treated with verapamil at 15 min heat treatment. HSP, heat shock proteins; DNAJ*, DNAJ subfamily *; PI, phosphatidylinositol; CaM, Calmodulin; cdsA, Phosphatidate cytidylyltransferase; dgkA, diacylglycerol kinase; INPP5B_F, phosphatidylinositol-bisphosphatase; IPMK, inositol-hexakisphosphate kinase; PI4K, phosphodylinositol 4-kinase; PIK3C3; phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PI5K, phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase; PLC, phospholipase C; PRKCA, Serine/threonine protein kinase; SAC1, phosphatidylinositide phosphatase; SAL, 3’(2’),5’-bisphosphate nucleotidase SAL1; SHIP1, inositol polyphosphate phosphatase; Psb*, Photosystem II* subunits; Psa*, photosystem I * subunit; PetC, cytochrome b6-f complex iron-sulfur subunit; petE, plastocyanin; petF, ferredoxin FNR; petH, ferredoxin–NADP+ reductase; petJ, cytochrome c6; ATP*, ATP synthase * subunit; LHCA1, light-harvesting complex protein; LHCB*, chlorophyll a-b binding protein *; cpcC, phycobilisome linker polypeptide; cpcF, phycocyanobilin lyase beta subunit; apcB, phycoerythrin beta subunit; apcC, allophycocyanin subunit; TPI, triose phosphate isomerase; PK, pyruvate kinase; pgm, glucose phosphate mutase; PGK, glyceric acid phosphate kinase; PFP, pyrophosphate–fructose-6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase; pfkA, 6-phosphofructokinase; pdhC, dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase; PDH*, pyruvate dehydrogenase * subunit; gpmI, phosphoglycerate mutase; GAPDH, Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; FBP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase place; ENO, enolase; FBA, Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase; ALDO, fructose diphosphate aldolase.

Our previous study found that heat stress induced obvious Ca2+ influx in N. haitanensis, which then regulated the downstream gene expression, such as, HSPs. Whereas, preventing an influx of Ca2+ into cells from external sources by verapamil decreased N. haitanensis heat tolerance (Zheng et al., 2020). The present result also showed that the Fv/Fm declined sharply and thalli rapidly bleached in Ca2+-free seawater (Figure 1) under heat stress. It demonstrated that extracellular Ca2+ functions as an important secondary messenger molecule in the response of N. haitanensis to heat stress.

Although different stimuli can cause a transient Ca2+ increase in cells, the changes in cytosolic concentration of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]cyt) caused by each environmental stress are unique (Anil and Sankara Rao, 2001). This uniqueness is reflected in the dynamics of subcellular localization or (Ca2+)cyt fluctuations (Franklin-Tong et al., 2002). For example, the increase in (Ca2+)cyt caused by low temperature is relatively large and very short, lasting only a few seconds to tens of seconds, i.e., a sharp-spike type (Yuan et al., 2018). The amplitude of the (Ca2+)cyt increase caused by oxidative stress and salt stress is relatively small and lasts from several minutes to dozens of minutes, while that caused by hypoxia stress lasts for several hours. For N. haitanensis, supplementation with Ca2+ at the early stage (15 min) of heat stress was able to restore the normal growth of thalli, but the heat tolerance of thalli could not recover when supplementation with Ca2+ after 30 min of heat stress. Therefore, Ca2+ signaling plays a role in the early response to heat stress in N. haitanensis.

Sensing of transient (Ca2+)cyt increase required for downstream stress-responses is mediated by Ca2+-binding sensor proteins. Our previous study revealed that CaM, a small acidic protein represents a universal Ca2+ sensor across eukaryotes (Reddy et al., 2002), are able to decipher Ca2+ signaling and then activated resistant genes in N. haitanensis under heat stress (Zheng et al., 2020). However, CaM has neither transcription factor nor enzyme activity, nor does it serve as a structural protein. It regulates physiological functions via downstream CaM-binding proteins. Therefore, the present study identified the proteins that interact with CaM to investigate how CaM regulates thermoltolerance of N. haitanensis. The result of ‘one to one’ verification by yeast two-hybrid assay showed that the CaM of N. haitanensis interacts with DnaJ, VDAC, and BDC proteins in response to heat stress (Figure 4).

One adverse impact of high temperatures on cells is the production and accumulation of denatured or misfolded proteins. HSPs can facilitate protein folding and stabilize partially unfolded proteins. The most conserved HSPs are molecular chaperones that prevent the formation of non-specific protein aggregates and help proteins to acquire and retain their native structures (Richter et al., 2010). HSPs has been demonstrated that contribute to the tolerance of N. haitanensis to various abiotic stresses, including heat stress (Wang et al., 2018), hypersaline stress (Wang et al., 2019; Wen et al., 2020), and hyposaline stress (Wang et al., 2020). As a molecular chaperone widely found in plant cells, DnaJ is a member of the HSP40 family and functions as a molecular chaperone to maintain intracellular protein homeostasis (Hennessy et al., 2005). The transcript level of gene encoding HSP40 were found to be significantly up-regulated in response to heat stress in N. haitanensis, but either CaM inhibitors or the absence of Ca2+ inhibited the expression of genes encoding HSPs, and this reduced the heat resistance of N. haitanensis (Figures 4, 5). This suggested that NhCaM1 is functional upstream of the induction of HSPs, and can bind HSP40 to regulate the response of thalli to heat stress, which is consistent with previous study. Such as, the expression of OsCaM1-1 and OsHSP17 reached their maximal expression levels rapidly within 30 min heat shock treatment in rice (Oryza sativa L). Meanwhile, Over-expression of OsCaM1 induced the expression of AtHSP at a non-inducing temperature and enhanced intrinsic heat tolerance in Arabidopsis (Wu et al., 2012). In transgenic Arabidopsis plants, UidA reporter gene expression directed by AtHSP18.2 promoter was affected by Ca2+ and CaM inhibitors (Liu et al., 2005). Ca2+-CaM regulates gene expression via mediating the phosphorylation status of heat shock factors, which in turn modulates the expression of HSPs genes for heat shock signal transduction (Liu et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2012). Therefore, Ca2+-CaM signal transduction system is crucial for activation of HSPs to maintain protein homeostasis during the response of N. haitanensis to heat stress.

Several Ca2+ transport systems across the endothelium control the concentration of Ca2+ in the cytoplasm or mitochondria (Gincel et al., 2001). VDAC are highly conserved proteins that exist in all eukaryotes and are the main protein components of the mitochondrial outer membrane (Colombini, 2012). As core members of mitochondrial metabolism and ion signaling, VDACs are involved in the exchange of compounds between the cytoplasm and the membrane, including ions such as Ca2+, metabolites such as succinate or ATP, and larger molecules such as tRNA or DNA that regulate the exchange of substances in response to cellular signals and stress (Homble et al., 2012). Ca2+ can pass through the mitochondrial outer membrane via VDACs, thus confirming their role in regulating Ca2+ homeostasis (Gincel et al., 2001). A previous study found that a VDAC of Arabidopsis thaliana interacts with the Ca2+ sensor calcineurin-B-like proteins 1 under cold stress (Li et al., 2013). In the present study, we found that the transcript level of VDAC, interacting with NhCaM1 in N. haitanensis, was significantly inhibited by inhibition of CaM under heat stress. It is possible that CaM regulates the transport of substances into and out of mitochondria through VDACs in N. haitanensis under heat stress.

As members of bromodomain and extra-terminal motif protein family, BCPs mediates a wide range of biological processes (Fujisawa and Filippakopoulos, 2017; Ren et al., 2017). Such as, many modifications (phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination) and transcriptional co-activation are involved in the regulation of transcription by polyprotein complexes containing BCPs (Denis, 2001a). BCPs affect histone and chromatin organization via interactions between the bromodomain and acetylated lysine residues. Lysine acetylation is a histone modification that forms a stable epigenetic mark on chromatin for BCPs to dock and in turn modulates gene transcription (Denis, 2001b; Hassan et al., 2007). Under heat stress, the interaction between NhCaM1 with BCP might ensure the diversity, speed, and flexibility of transcriptional responses so that the thalli of N. haitanensis can actively respond to heat stress. However, the type of BCP and how it interacts with acetylated histidine residues in N. haitanensis are yet to be verified.

The phosphatidylinositol (PI) signaling system is significant for cells to response to different biotic and abiotic stresses, and interaction with Ca2+ signaling network (Berridge et al., 1998; Lin et al., 2004). The present result showed that under heat stress, the expression of PLC, PI4K, and PI5K exhibited up-regulation after inhibition of Ca2+ channels (Figure 5). PI can be phosphorylated at 4’ position of the inositol ring by PI4Ks, which resulting in production of two second messenger precursors (phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P)) and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) (Xu et al., 1992). Nilius et al. (2006) revealed that PI(4,5)P2 strikingly improved activity of TRPM4, that depolarizes the plasma membrane and regulates Ca2+ influx, by increasing the channel’s Ca2+ sensitivity. The loss of OsPLC4 compromised the increase of inositol triphosphate and free cytoplasmic Ca2+ in Oryza sativa cv, and inhibited the induction of genes involved in Ca2+ sensor and salt stress (Deng et al., 2019). Similarly, OsPLC1 preferred to hydrolyze PI4P and elicited salt stress-induced Ca2+ signals (Li et al., 2017). Additionally, PI signaling can also regulate HSPs activity under abiotic stresses. It has been demonstrated that accumulation of the small heat shock proteins (HSP18.2 and HSP25.3) was downregulated in a PLC mutant line of Arabidopsis (atplc9) and was upregulated in the overexpressed lines after heat shock (Zheng et al., 2012). This might interpret why the transcripts of few HSPs genes were up-regulated after the inhibition of Ca2+ signaling. Thus, it has been speculated that in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ influx signals, N. haitanensis activated PI signaling earlier to regulate the response to heat stress through increasing the concentration of intracellular Ca2+ or other ways.

N. haitanensis captures light via phycoerythrin (PE), phycocyanin, and allophycocyanin. The up-regulated expression of a PE precursor of N. haitanensis was detected after 15 min of heat stress, while they were down-regulated after Ca2+ influx was inhibited. It suggested that increased synthesis of PE was regulated by the extracellular Ca2+ signal, which helped the thalli capture light and positively respond to heat stress. Additionally, Ca2+ can help protect the photosynthetic system from photoinhibition under heat stress by accelerating the repair of subunits in the photosystem II reaction center (Yang et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2015). In vivo, the degree of damage under stress depends on the balance between damage and repair processes, especially in the light system (Mohanty et al., 2007). After only 15 min of heat treatment, some proteins in the photosystem were up-regulated and the dimer structure was stabilized to allow photosynthesis to continue normally in N. haitanensis. In contrast, in the absence of the extracellular Ca2+ signal, photosystem of thalli could not be repaired in a timely manner.

The stability of energy supply under stress is closely related to stress resistance. N. haitanensis can resist stress by increasing energy metabolism, mainly the glycolytic pathway and pentose phosphate pathway (Wang et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2020). Here, we also found similar results, however, the main genes, such as, Fructose 6-phosphate kinase (PFK), Fructose-bisphosphate (FBP) aldolase, phospholipase c (PLC) of glycolytic pathway showed downregulated under heat stress after inhibition of Ca2+ channels by verapamil (Figure 5). Among these genes, higher activity of FBP aldolase stimulates the glycolytic pathway by catalyzing a reversible cleavage reaction of fructose-1, 6-bisphosphate into two trioses: glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate (Matsumoto and Ogawa, 2008). He et al. (2012) found that exogenous Ca2+ significantly elevated the quantity of the FBP aldolase, which alleviated the effects of hypoxic stress on cucumber roots. Meanwhile, the glycolytic pathway (initiated with sucrose synthase forming UDP-glucose and fructose and completed with alcohol dehydrogenase) were up-regulated via Ca2+ elevation under hypoxic stress (Igamberdiev and Hill, 2018). Therefore, the Ca2+ signal is involved in regulating the glycolytic pathway to provide energy and the related carbon skeletons for key metabolic processes in the response of N. haitanensis to heat stress.

Our results show that Ca2+-CaM is involved in the early response of N. haitanensis to heat stress. It is crosstalk with PI signaling and is crucial for triggering HSPs to maintain protein homeostasis, regulating the transport of substances into and out of mitochondria through VDACs, and activating glycolysis to provide energy and the related carbon skeletons during the response of N. haitanensis to heat stress. These results increase our understanding of the molecular mechanisms associated with Ca2+ signal transduction in N. haitanensis under heat stress.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: NCBI [accession: PRJNA725630].

CTX, HYZ, and WLW designed the experiments. HYZ and WLW, carried out the experiments. HYZ, WLW, CTX, CSC, KX, YX, and DHJ analyzed the data, interpreted the results. HYZ, WLW, and CTX drafted the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: U21A20265 and 31872567), Fujian Province Science and Technology Major Project (2019NZ08003) and the China Agriculture Research System (grant number: CARS-50).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank Jennifer Smith, PhD, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.875308/full#supplementary-material

Anil V. S., Sankara Rao K. (2001). Calcium-Mediated Signal Transduction in Plants: A Perspective on the Role of Ca2+ and CDPKs During Early Plant Development. J. Plant Physiol. 158 (10), 1237–1256. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-00550

Berridge M. J., Bootman M. D., Lipp P. (1998). Calcium-A Life and Death Signal. Nature 395, 645–648. doi: 10.1038/27094

Chang J., Shi J., Lin J., Ji D., Xu Y., Chen C., et al. (2021). Molecular Mechanism Underlying Pyropia Haitanensis PhHsp22-Mediated Increase in the High-Temperature Tolerance of Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. J. Appl. Phycol. 33 (2), 1137–1148. doi: 10.1007/s10811-020-02351-6

Chen C. S., Ji D. H., Xie C. T., Xu Y., Liang Y., Zheng Y., et al. (2008). Preliminary Study on Selecting the High Temperature Resistance Strains and Economic Traits of Porphyra Haitanensis (in Chinese With English Abstract). Acta Oceanol. Sin. 30, 100–106. doi: 10.1007/s11676-008-0012-9

China Fishery Bureau (2021). China Fishery Statistical Yearbook (in Chinese). Chin. Agric. Express, 2, 28

Colombini M. (2012). VDAC Structure, Selectivity, and Dynamics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818 (6), 1457–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.12.026

Deng X., Yuan S., Cao H., Lam S. M., Shui G., Hong Y., et al. (2019). Phosphatidylinositol-Hydrolyzing Phospholipase C4 Modulates Rice Response to Salt and Drought. Plant Cell Environ. 42 (2), 536–548. doi: 10.1111/pce.13437

Denis G. V. (2001a). Bromodomain Motifs and "Scaffolding"? Front. Biosci. 1 (6), 1065–1068. doi: 10.2741/A668

Denis G. V. (2001b). Duality in Bromodomain-Containing Protein Complexes. Front. Biosci. 1 (6), 849–852. doi: 10.2741/denis

Dodd A. N., Kudla J., Sanders D. (2010). The Language of Calcium Signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 593–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-070109-104628

FAO (2017) Fisheries & Aquaculture-Fisheries and Aquaculture Fact Sheets. Available at: http://www.fao.org/fishery/factsheets/en (Accessed 2 August 2017).

Franklin-Tong V. E., Holdaway-Clarke T. L., Straatman K. R., Kunkel J. G., Hepler P. K. (2002). Involvement of Extracellular Calcium Influx in the Self-Incompatibility Response of Papaver Rhoeas. Plant J. 29 (3), 333–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01219.x

Fujisawa T., Filippakopoulos P. (2017). Functions of Bromodomain-Containing Proteins and Their Roles in Homeostasis and Cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 246–262. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.143

Gincel D., Zaid H., Shoshan-Barmatz V. (2001). Calcium Binding and Translocation by the Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel: A Possible Regulatory Mechanism in Mitochondrial Function. Biochem. J. 358, 147–155. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580147

Hassan A. H., Awad S., Al-Natour Z., Othman S., Mustafa F., Rizvi T. A. (2007). Selective Recognition of Acetylated Histones by Bromodomains in Transcriptional Co-Activators. Biochem. J. 402 (1), 125–133. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060907

He L., Lu X., Tian J., Yang Y., Li B., Li J., et al. (2012). Proteomic Analysis of the Effects of Exogenous Calcium on Hypoxic-Responsive Proteins in Cucumber Roots. Proteome Sci. 10 (1), 1–15. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-10-42

Hennessy F., Nicoll W. S., Zimmermann R., Cheetham M. E., Blatch G. L. (2005). Not All J Domains are Created Equal: Implications for the Specificity of Hsp40-Hsp70 Interactions. Protein Sci. 14 (7), 1697–1709. doi: 10.1110/ps.051406805

Homble F., Krammer E. M., Prevost M. (2012). Plant VDAC: Facts and Speculations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818 (6), 1486–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.11.028

Igamberdiev A. U., Hill R. D. (2018). Elevation of Cytosolic Ca2+ in Response to Energy Deficiency in Plants: The General Mechanism of Adaptation to Low Oxygen Stress. Biochem. J. 475 (8), 1411–1425. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20180169

Li B., Chen C., Xu Y., Ji D., Xie C. (2014). Validation of Housekeeping Genes as Internal Controls for Studying the Gene Expression in Pyropia Haitanensis (Bangiales, Rhodophyta) by Quantitative Real-Time PCR. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 33 (9), 152–159. doi: 10.1007/s13131-014-0526-2

Lin W. H., Ye R., Ma H., Xu Z. H., Xue H. W. (2004). DNA Chip-Based Expression Profile Analysis Indicates Involvement of the Phosphatidylinositol Signaling Pathway in Multiple Plant Responses to Hormone and Abiotic Treatments. Cell Res. 14 (1), 34–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290200

Liu H. T., Gao F., Li G. L., Han J. L., Liu D. L., Sun D. Y., et al. (2008). The Calmodulin-Binding Protein Kinase 3 is Part of Heatshock Signal Transduction in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant J. 55, 760–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03544.x

Liu H. T., Li G. L., Chang H., Sun D. Y., Zhou R. G., Li B. (2007). Calmodulin-Binding Protein Phosphatase PP7 is Involved in Thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 156–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01613.x

Liu H. T., Sun D. Y., Zhou R. G. (2005). Ca2+ and AtCaM3 are Involved in the Expression of Heat Shock Protein Gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 1276–1284. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01365.x

Li L., Wang F., Yan P., Jing W., Zhang C., Kudla J., et al. (2017). A Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C Pathway Elicits Stress-Induced Ca2+ Signals and Confers Salt Tolerance to Rice. New Phytol. 214 (3), 1172–1187. doi: 10.1111/nph.14426

Li Z. Y., Xu Z. S., He G. Y., Yang G. X., Chen M., Li L. C., et al. (2013). The Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel 1 (AtVDAC1) Negatively Regulates Plant Cold Responses During Germination and Seedling Development in Arabidopsis and Interacts With Calcium Sensor CBL1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 (1), 701–713. doi: 10.3390/ijms14010701

Love M. I., Huber W., Anders S. (2014). Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNAseq Data With Deseq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. 2014. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

Matsumoto M., Ogawa K. (2008). “New Insight Into the Calvin Cycle Regulation Glutathionylation of Fructose Bisphosphate Aldolase in Response to Illumination,” in Photosynthesis Energy From the Sun. Eds. Allen J. F., Gantt E., Golbeck J. H., Osmond B. (Netherlands: Springer), 872–874.

McAinsh M. R., Pittman J. K. (2009). Shaping the Calcium Signature. New Phytol. 181 (2), 275–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02682.x

Mohanty P., Allakhverdiev S. I., Murata N. (2007). Application of Low Temperatures During Photoinhibition Allows Characterization of Individual Steps in Photodamage and the Repair of Photosystem II. Photosynth Res. 94, 217–224. doi: 10.1007/s11120-007-9184-y

Nilius B., Mahieu F., Prenen J., Janssens A., Owsianik G., Vennekens R., et al. (2006). The Ca2+-Activated Cation Channel TRPM4 is Regulated by Phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-Biphosphate. EMBO J. 25 (3), 467–478. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600963

Ouyang J., Zhang M. Y., Xia K. F. (2011). Calcium Distribution in Developing Anther Cells of No-Pollen Type CMS and Maintainer Lines of Rice (Oryza Sativa L.). J. Plant Sci. 29 (1), 109–117. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1142.2011.10109

Pawar P. S., Micoli K. J., Ding H., Cook W. J., Kappes J. C., Chen Y., et al. (2008). Calmodulin Binding to Cellular FLICE-Like Inhibitory Protein Modulates Fas-Induced Signalling. Biochem. J. 412 (3), 459–468. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071507

Reddy V. S., Ali G. S., Reddy A. S. (2002). Genes Encoding Calmodulin-Binding Proteins in the Arabidopsis Genome* 210. J. Biol. Chem. 277 (12), 9840–9852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111626200

Ren W., Wang C., Wang Q., Zhao D., Zhao K., Sun D., et al. (2017). Bromodomain Protein Brd3 Promotes Ifnb1 Transcription via Enhancing IRF3/p300 Complex Formation and Recruitment to Ifnb1 Promoter in Macrophages. Sci. Rep. 7, 39986. doi: 10.1038/srep39986

Rhoads A. R., Friedberg F. (1997). Sequence Motifs for Calmodulin Recognition. FASEB J. 11 (5), 331. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.5.9141499

Richter K., Haslbeck M., Buchner J. (2010). The Heat Shock Response: Life on the Verge of Death. Mol. Cell 40 (2), 253–266. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.006

Robinson M. D., McCarthy D. J., Smyth G. K. (2010). Edger: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 26 (1), 139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616

Shi J., Chen Y., Xu Y., Ji D., Chen C., Xie C. (2017). Differential Proteomic Analysis by iTRAQ Reveals the Mechanism of Pyropia Haitanensis Responding to High Temperature Stress. Sci. Rep. 7, 44734. doi: 10.1038/srep44734

Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013). MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 (12), 2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197

Wang W., Chen T., Xu Y., Xu K., Xu Y., Ji D., et al. (2020). Investigating the Mechanisms Underlying the Hyposaline Tolerance of Intertidal Seaweed, Pyropia Haitanensis. Algal Res. 47, 101886. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2020.101886

Wang W., Teng F., Lin Y., Ji D., Xu Y., Chen C., et al. (2018). Transcriptomic Study to Understand Thermal Adaptation in a High Temperature-Tolerant Strain of Pyropia Haitanensis. PLoS One 13 (4), e0195842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195842

Wang W., Xu Y., Chen T., Xing L., Xu K., Xu Y., et al. (2019). Regulatory Mechanisms Underlying the Maintenance of Homeostasis in Pyropia Haitanensis Under Hypersaline Stress Conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 662, 168–179. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.214

Wen J., Wang W., Xu K., Ji D., Xu Y., Chen C., et al. (2020). Comparative Analysis of Proteins Involved in Energy Metabolism and Protein Processing in Pyropia Haitanensis at Different Salinity Levels. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00415

Wu H. C., Luo D. L., Vignols F., Jinn T. L. (2012). Heat Shock-Induced Biphasic Ca2+ Signature and OsCaM1-1 Nuclear Localization Mediate Downstream Signalling in Acquisition of Thermotolerance in Rice (Oryza Sativa L.). Plant Cell Environ. 35 (9), 1543–1557. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02508.x

Xu P., Lloyd C. W., Staiger C. J., Drobak B. K. (1992). Association of Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase With the Plant Cytoskeleton. Plant Cell 4 (8), 941–951. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.8.941

Xu Y., Chen C., Ji D., Hang N., Xie C. (2013). Proteomic Profile Analysis of Pyropia Haitanensis in Response to High-Temperature Stress. J. Appl. Phycol. 26 (1), 607–618. doi: 10.1007/s10811-013-0066-8

Yang S., Wang F., Guo F., Meng J. J., Li X. G., Dong S. T., et al. (2013). Exogenous Calcium Alleviates Photoinhibition of PSII by Improving the Xanthophyll Cycle in Peanut (Arachis Hypogaea) Leaves During Heat Stress Under High Irradiance. PLoS One 8 (8), e71214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071214

Yang S., Wang F., Guo F., Meng J. J., Li X. G., Wan S. B. (2015). Calcium Contributes to Photoprotection and Repair of Photosystem II in Peanut Leaves During Heat and High Irradiance. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 57 (5), 486–495. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12249

Yan X. H., Lv F., Liu C. J., Zheng Y. F. (2009). Selection and Characterization of a High-Temperature Tolerant Strain of Porphyra Haitanensis Chang Et Zheng (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). J. Appl. Phycol. 22 (4), 511–516. doi: 10.1007/s10811-009-9486-x

Yuan P., Yang T., Poovaiah B. W. (2018). Calcium Signaling-Mediated Plant Response to Cold Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 (12) 3896. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123896

Yu F. Y., Guy R. D. (2004). Variable Chlorophyll Fluorescence in Response to Water Plus Heat Stress Treatments in Three Coniferous Tree Seedlings. J. Forestry R. 15 (1), 24–28. doi: 10.1007/BF02858005

Zheng H., Wang W., Xu K., Xu Y., Ji D., Chen C., et al. (2020). Ca2+ Influences Heat Shock Signal Transduction in Pyropia Haitanensis. Aquaculture 516, 734618. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734618

Keywords: calcium signal, calmodulin, heat stress, Neoporphyra haitanensis, yeast two-hybrid

Citation: Zheng H, Xu Y, Ji D, Xu K, Chen C, Wang W and Xie C (2022) Calcium-Calmodulin-Involved Heat Shock Response of Neoporphyra haitanensis. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:875308. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.875308

Received: 14 February 2022; Accepted: 11 March 2022;

Published: 31 March 2022.

Edited by:

Guang Gao, Xiamen University, ChinaReviewed by:

Nianjun Xu, Ningbo University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Zheng, Xu, Ji, Xu, Chen, Wang and Xie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chaotian Xie, Y3R4aWVAam11LmVkdS5jbg==; Wenlei Wang, d2x3YW5nQGptdS5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.