95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 02 November 2021

Sec. Aquatic Physiology

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.734519

This article is part of the Research Topic Aquatic Physiology, Environmental Pollution, Nanotoxicology and Phytoremediation, Volume II View all 7 articles

The mud crab Scylla paramamosain is an important euryhaline mariculture species. However, acute decreases in salinity seriously impact its survival and can result in large production losses. In this study, we evaluated metabolic changes in S. paramamosain exposed to an acute salinity reduction from 23 psu to 3 psu. After the salinity decrease, hemolymph osmolality declined from 726.75 to 642.38 mOsm/kg H2O, which was close to the physiological equilibrium state. Activities of osmolality regulation-related enzymes in the gills, including Na+-K+-ATPase, CA, and V-ATPase all increased. Using LC-MS analysis, we identified 519 metabolites (mainly lipids). Additionally, 13 significant metabolic pathways (P < 0.05) were identified via enrichment analysis, which were mainly related to signal pathways, lipids, and transportation. Our correlation analysis, which combined LC-MS and previous GC-MS data, yielded 28 significant metabolic pathways. Amino acids and energy metabolism accounted for most of these pathways, and lipid metabolism pathways were insignificant. Our results showed that amino acids and energy metabolism were the dominant factors involved in the adaptation of S. paramamosain to acute salinity decrease, and lipid metabolites played a supporting role.

Changes in salinity impact the growth (Nurdiani and Zeng, 2007), immunity (Péqueux, 1995), and disease status (Parado-Estepa and Quinitio, 2011) of crustaceans. Osmotic regulation is the main way by which crustaceans adapt to salinity change. Inorganic ions and amino acids are the main factors that impact osmolality in crustaceans (Pan et al., 2007; Romano and Zeng, 2012; Long et al., 2018).

The gill is the main organ responsible for osmotic regulation, including hemolymph ion concentration, in crustaceans (Whiteley, 2011; Leone et al., 2015), and this regulation occurs mainly by ion transport via Na+/K+-ATPase (exclusively basolaterally located), Na+/K+/2Cl−cotransporters (both basolaterally and apically located), vacuolar-type (V-type) H+-ATPase (apically located), Cl−/(apically located), Na+/(apically located), and Na+/H+exchanger (apically located) (Henry, 2001; Weihrauch et al., 2004; Tsai and Lin, 2007; Freire et al., 2008). Muscle is the main source of amino acids (Dooley et al., 2000; Mcnamara et al., 2004), which are the main substances responsible for maintaining cellular osmolality. Therefore, they play an important role in the process by which crustaceans adapt to changes in salinity (Shinji et al., 2012; Lv et al., 2013). Previous studies have shown that the amino acids produced in muscle supplemented the hemolymph to help maintain the osmolality balance in a hypotonic environment (Lu et al., 2015).

The mud crab Scylla paramamosain is a euryhaline crustacean that is widely distributed from the Indian Ocean to the western Pacific region, including along the southeast coast of China (Vay et al., 2007). It is still extremely sensitive to sudden reductions in salinity, especially sharp falls (10 psu based on production data), in our team's previous research we found that under acute low-salt stress, 3 psu is an adaptable lower salinity; under the stress of a sudden drop from 23 to 3 psu, individual scylla crabs can adapt to the environment after the stress for 120 h (Wang et al., 2018a,b). Portunid Crab Scylla serrate live in saltwater and/or saltwater estuaries, and mature females migrate offshore to reproduce (Hill, 1994). Such regions are susceptible to heavy rains or large-scale changes to the aquatic environment, which lead to acute decreases in salinity (Scavia et al., 2002). Large salinity decreases may exceed the capability of S. paramamosain to regulate osmolality, which can lead to death (Anger et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018b). Therefore, the environment used to culture S. paramamosain should avoid large changes in salinity.

In previous studies of osmotic regulation in S. paramamosain, ions involved in osmotic regulation were identified (Xu et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019), as were proteases that regulate these ions (Chung and Lin, 2006). Related signal pathways were also discovered (Wang et al., 2018b). Yao et al. (2020) reported that taurine, glycine, and glutamic acid and their related metabolic pathways were crucial for regulation in S. paramamosain. These studies focused mainly on the substances that affected osmolality. Other researchers evaluated genes related to amino acid synthesis regulation and protein translation (Chung and Lin, 2006; Lu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019). (Wang et al. 2018a,b, 2019) reported that osmolality regulation by S. paramamosain consumes energy. We previously used gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to study the biological mechanism used by S. paramamosain to adapt to acute salinity decreases (Yao et al., 2020). To further explore this mechanism, we used correlation analysis of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and GC-MS data in this study.

A total of 300 randomly selected crabs with a bodyweight of (30 ± 3.1 g) were selected and kept in a natural water environment with a salinity of 23 psu and a temperature of ~20°C. Crabs were randomly into six groups of fifty, housed in six cement pools under identical physical and chemical conditions. The salinity of the seawater for three of the groups was adjusted to 3 psu from 23 psu, a drop of 20 psu. These three groups were defined as the LS (low salinity) group. The other three groups were defined as the CK groups, where the salinity of seawater was kept at 23 psu. All other conditions were the same as the LS group (Wang et al., 2018a,b,c, 2019).

All chemicals and solvents were analytical or HPLC grade. Water, methanol, acetonitrile, and formic acid were purchased from CNW Technologies GmbH (Düsseldorf, Germany). L-2-chlorophenylalanine was from Shanghai Hengchuang Bio-technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Following the method developed by Long et al. (2018), serum samples from S. paramamosain were thawed at room temperature, homogenized with an IKA homogenizer (Staufen, Germany) for 30 s, and centrifuged at 4°C and 12,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant (hemolymph) was then used for the measurement of osmolality. The osmolality of serum and water samples was measured using a Fiske 210 (ADVANCED, USA) osmometer. For the analysis, 0.1 g of rear gill tissue was diluted with saline (1:9) and homogenized for 1 min in an ice-water bath using an IKA micro-homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C and 3,000 rpm. The supernatant was collected, and an ELISA assay kit (Qiaodu Biomart Inc., Shanghai, China) was used to measure Na+-K+-ATPase, V-ATPase, and CA activities.

A measure of 30 mg of accurately weighed sample was transferred to a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. Two small steel balls were added to the tube. Then, 20 μL internal standard (2-chloro-lphenylaln-ine in methanol, 0.3 mg/mL, LysoPC17:0,0.01 mg/mL) and 400 μL extraction solvent with methanol /water (4/1, v/v) were added to each sample. Samples were stored at −20°C for 2 min and then ground at 60 HZ for 2 min, ultrasonicated by ice-water bath for 10 min, and stored at −20°C for 20 min. The extract was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm, 4°C for 10 min. The supernatants (200 μL) from each tube were collected using crystal syringes, filtered through 0.22 μm microfilters, and transferred to LC vials. The vials were stored at −80°C until LC-MS analysis.

QC samples were prepared by mixing aliquots of all samples to be a pooled sample.

A Dionex 3000 UHPLC system fitted with Q-Exactive plus an Orbitrap mass spectrometer equipped with a heated electrospray ionization (ESI) source (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to analyze the metabolic profiling in both ESI positive and ESI negative ion modes. Chromatographic separation of samples was performed using an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm). The mobile phase consisted of (A) water (containing 0.1% formic acid, v/v) and (B) acetonitrile (containing 0.1% formic acid, v/v), and separation was achieved using the following gradient: 0–1 min holding at 5% B, 5–100% B over 1–11 min, the composition was held at 100% B for 2 min, 100% B over 11–13 min, then 13–13.1 min, 100% to 5% B, and 13.1–15 min holding at 5% B. The flow rate was 0.35 mL/min and the column temperature was 50°C. All the samples were kept at 4°C during the analysis. The injection volume was 5 μL.

The mass range was from m/z 70 to 1,000. The resolution was set at 70,000 for the full MS scans and 17,500 for HCD MS/MS scans. The collision energy was set at 20 and 40 eV. The mass spectrometer operated as follows: spray voltage, 3,800 V (+) and 3,000 V (–); sheath gas flow rate, 35 arbitrary units; auxiliary gas flow rate, 8 arbitrary units; capillary temperature, 320°C.

The QCs were injected at regular intervals (every 10 samples) throughout the analytical run to provide a set of data from which repeatability can be assessed.

The acquired LC-MS raw data were analyzed by the Progenesis QI software (Waters Corporation,Milford, USA) using the following parameters: Precursor tolerance was set 5 ppm, fragment tolerance was set 10 ppm, and retention time (RT) tolerance was set 0.02 min. Internal standard detection parameters were deselected for peak RT alignment, isotopic peaks were excluded for analysis, and noise elimination level was set at 10.00, the minimum intensity was set to 15% of base peak intensity. The Excel file was obtained with three-dimensional data sets including m/z, peak RT and peak intensities, and RT–m/z pairs were used as the identifier for each ion. The resulting matrix was further reduced by removing any peaks with a missing value (ion intensity = 0) in more than 50% of samples. The internal standard was used for data QC (reproducibility).

Metabolites were identified by progenesis QI (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA) Data Processing Software, based on public databases such as http://www.hmdb.ca/; http://www.lipidmaps.org.

The positive and negative data were combined to produce a combined data set which was imported into the SIMCA software (version 14.0, Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden) package. Principle component analysis (PCA) and (orthogonal) partial least-squares discriminant analysis (O)PLS-DA were carried out to visualize the metabolic alterations among experimental groups, after mean centering (Ctr) and Pareto variance (Par) scaling, respectively. The Hotelling's T2 region, shown as an ellipse in score plots of the models, defines the 95% confidence interval of the modeled variation. Variable importance in the projection (VIP) ranks the overall contribution of each variable to the OPLS-DA model, and those variables with VIP > 1 are considered relevant for group discrimination. In this study, the default 7-round cross-validation was applied with one-seventh of the samples being excluded from the mathematical model in each round, in order to guard against overfitting.

The differential metabolites were selected on the basis of the combination of a statistically significant threshold of variable influence on projection (VIP) values obtained from the OPLS-DA model and p-values from a two-tailed Student's t-test on the normalized peak areas from different groups, where metabolites with VIP values larger than 1.0 and p-values < 0.05 were considered as differential metabolites.

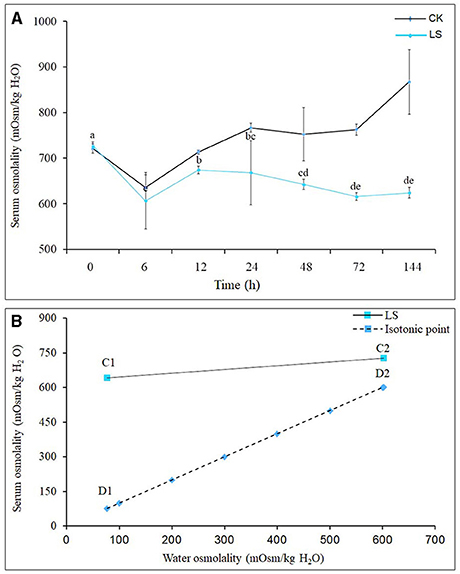

After the salinity dropped from 23 to 3 psu, the hemolymph osmolality of S. paramamosain began to drop rapidly, and reached its lowest point of 606.50 mOsm/kg H2O at 6 h, then began to rise, reaching its highest at 24 h, before it slowly decreased and stabilized after 48 h (Figure 1A). The osmolality (D2) of seawater with a salinity of 23 psu was 601.75 mOsm/kg H2O, while the osmolality (C2) of the hemolymph of S. paramamosain in this environment was 726.75mOsm/kg H2O (Figure 2B); when the seawater salinity dropped to 3 psu, the osmolality (D1) of seawater was 77.18 mOsm/kg H2O, but the osmolality (C1) of S. paramamosain was 642.38 mOsm/kg H2O (Figure 2B). It can be seen that the osmolality of S. paramamosain is always higher than the osmolality of seawater in the environment of 3–23 psu, and the osmolality of S. paramamosain will not decrease greatly with the rapid decrease of seawater osmolality.

Figure 1. Effect of salinity on hemolymph osmolality of S.paramamosainn; (A) shows the changes in osmolality of S.paramamosainn under the change of salinity; (B) is the osmolality isotonic map of S.paramamosainn and seawater. In the (B), D1 and C1 are the hemolymph osmolality in S.paramamosain at the salinity 23 and 3, respectively, and C2 and D2 are the seawater osmolality at the 23 and 3 psu, respectively.

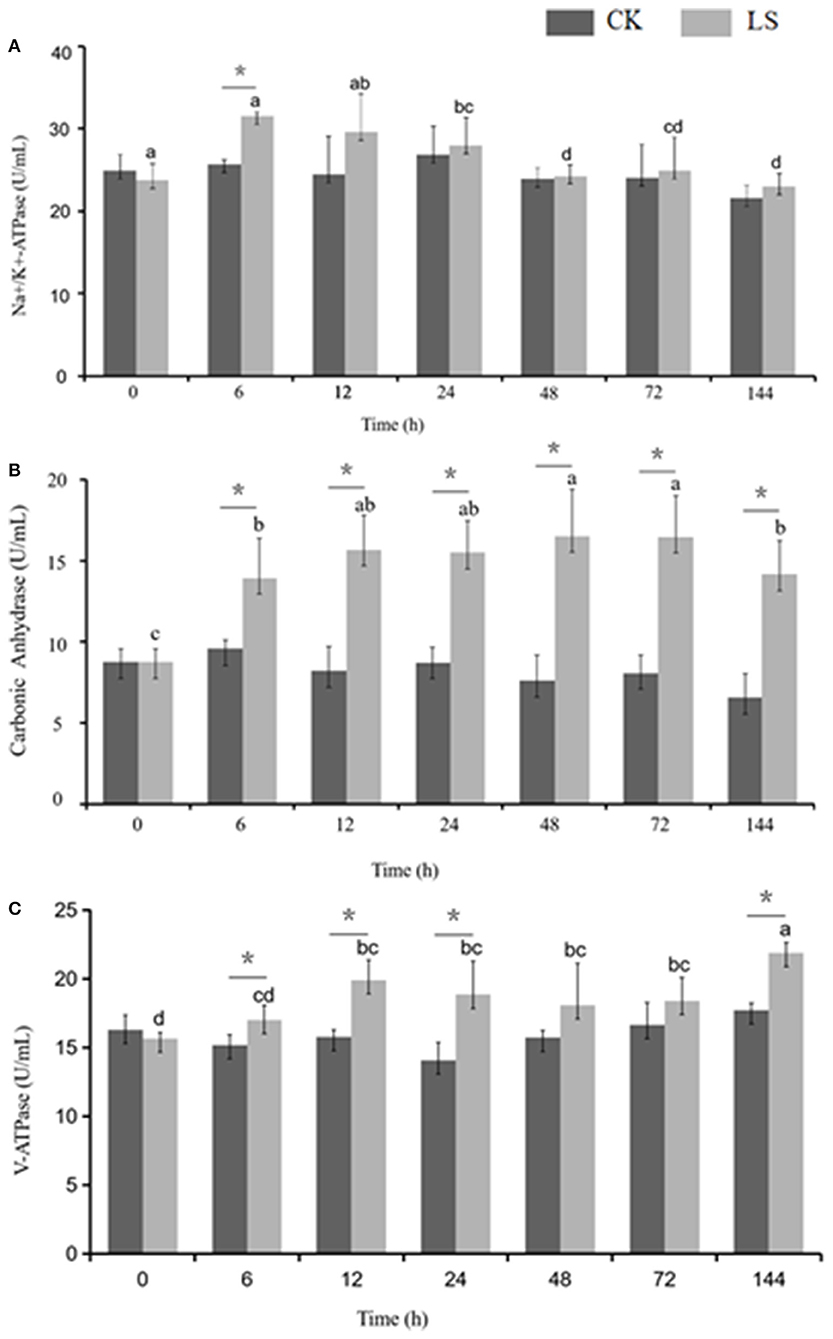

Figure 2. Effect of salinity on the ion transportation enzyme activity in the gills of S.paramamosain. * means significant difference in ion transport enzyme activity with different salinity at the same time.

Many enzymes were involved in osmolality regulation of S.paramamosain. When salinity decreased from 23 to 3 psu, Na+-K+-ATPase activity increased to 31.53 U/mL after 6 h, and this value was significantly higher than that of the CK group. The activity gradually decreased after 24 h and eventually reached an equilibrium state at 24.28 U/mL (Figure 2A). CA activity increased during the first 6 h and stayed at this stable state thereafter. Moreover, CA activity of the LS group (16.54 U/mL) was significantly (1.8 times) higher than that of the CK group. V-ATPase activity increased during the first 6 h to reach 21.88 U/mL, and then it stabilized (Figure 2).

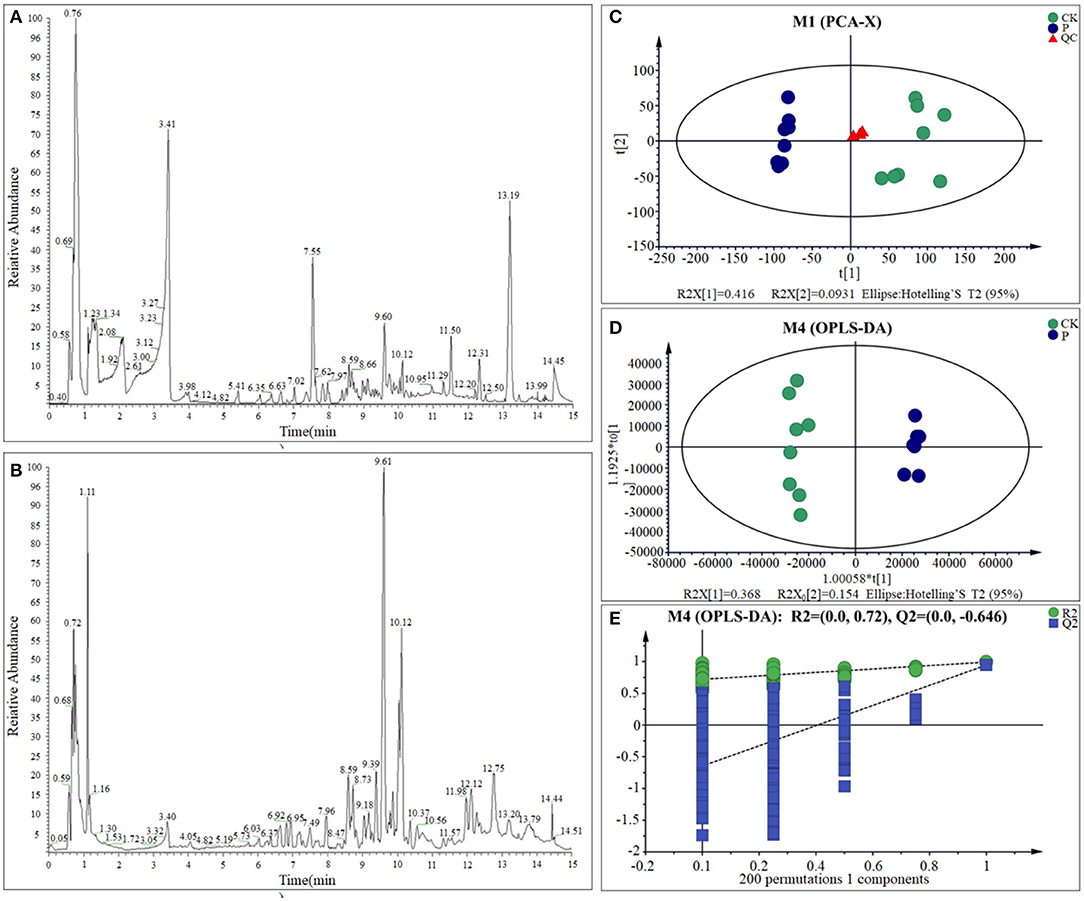

Previous studies showed the S. paramamosainreached an adaptive state after 120 h, when the seawater salinity dropped suddenly from 23 to 3 psu (Wang et al., 2018a,b,c, 2019). Therefore, LC-MS was adopted to detect the metabolome changes of gills between CK and LS crabs. Base peak chromatograms of QC (quality control sample) in positive ion ESI (+) (Figure 3A) mode and QC in negative ion ESI (–) (Figure 3B) mode indicated that the instrument analysis of all samples has strong signal strength, large peak capacity and good reproducibility of retention time. After data processing, 16,261 mass spectrum features were detected, and 4,023 metabolites were identified. The detectable metabolites of gill extracts contain Fatty Acyls, Carboxylic acids and their derivatives, Glycerophospholipids, and so on. In order to specifically explore the changes in the sudden drop in salinity, these LC-MS data were analyzed with multivariate data and univariate data.

Figure 3. BPC of gills sample from QC sample in ESI (+) (A) and ESI (–) (B); PCA scores plot (C), OPLS-DA scores plots (D), and response permutation testing (E) for CK and LS of the S.paramamosain.

One of the most important steps of this study was to examine the quality of the data. The use of quality control (QC) samples is required to obtain reliable and high-quality results (Stefanuto et al., 2015; Araújo et al., 2018). The principal component analysis (PCA) showed that with the exception of one outlier sample, all the other samples are within the confidence interval of 95%. Quality control (QC) sample aggregation indicates the obtained data is reliable and stable. The cumulative interpretation rate [R2X (cum)] is up to 0.672, indicating that the PCA model can be obtained to show the actual distribution of the sample. Therefore, the PCA result reveals the CK group and the LS group had a relatively obvious distribution rule (Figure 3C; Supplementary Table 1). Meanwhile, OPLS-DA model shows the difference between the two groups is significant (x-axis orientation), and all sample points are within the 95% confidence interval (Figure 3D; Supplementary Table 1). Through the fitting examination of the OPLS-DA model, it can be found that the interpretation ability of the model [R2Y (cum)] and predictive ability [Q2 (cum)] for the samples were 0.992 and 0.944, respectively. Besides, the slope of the straight line is large, and the intercept of Q2 is −0.646, indicating that the OPLS-DA model does not exceed the fitting (Figure 3E and Supplementary Table 1). In conclusion, the OPLS-DA model has good interpretation and prediction ability and can reflect the difference between different sample groups in real response. All of the above results showed that the metabolites of S. paramamosain gills at 3 psu seawater have changed obviously, comparing to 23 psu.

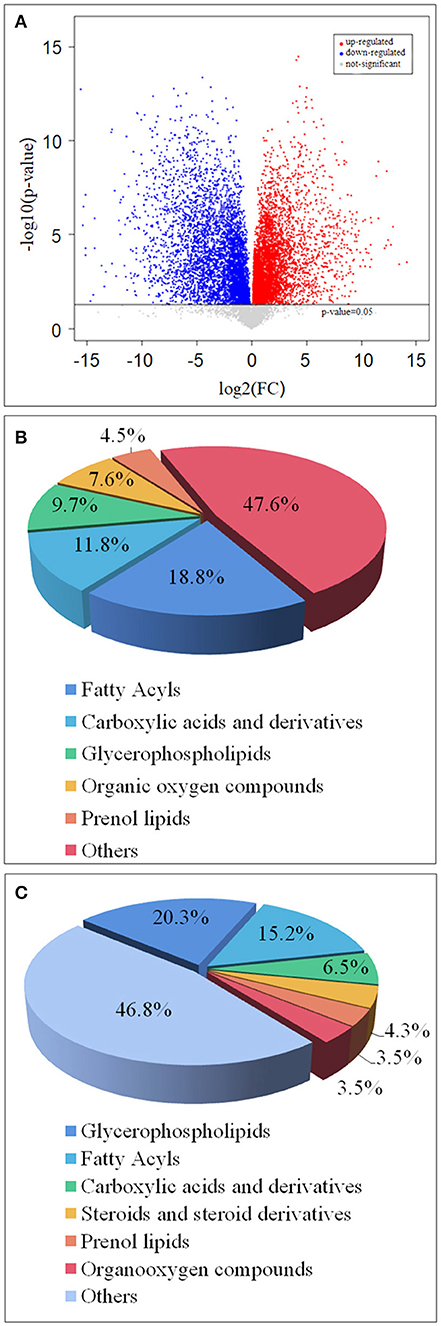

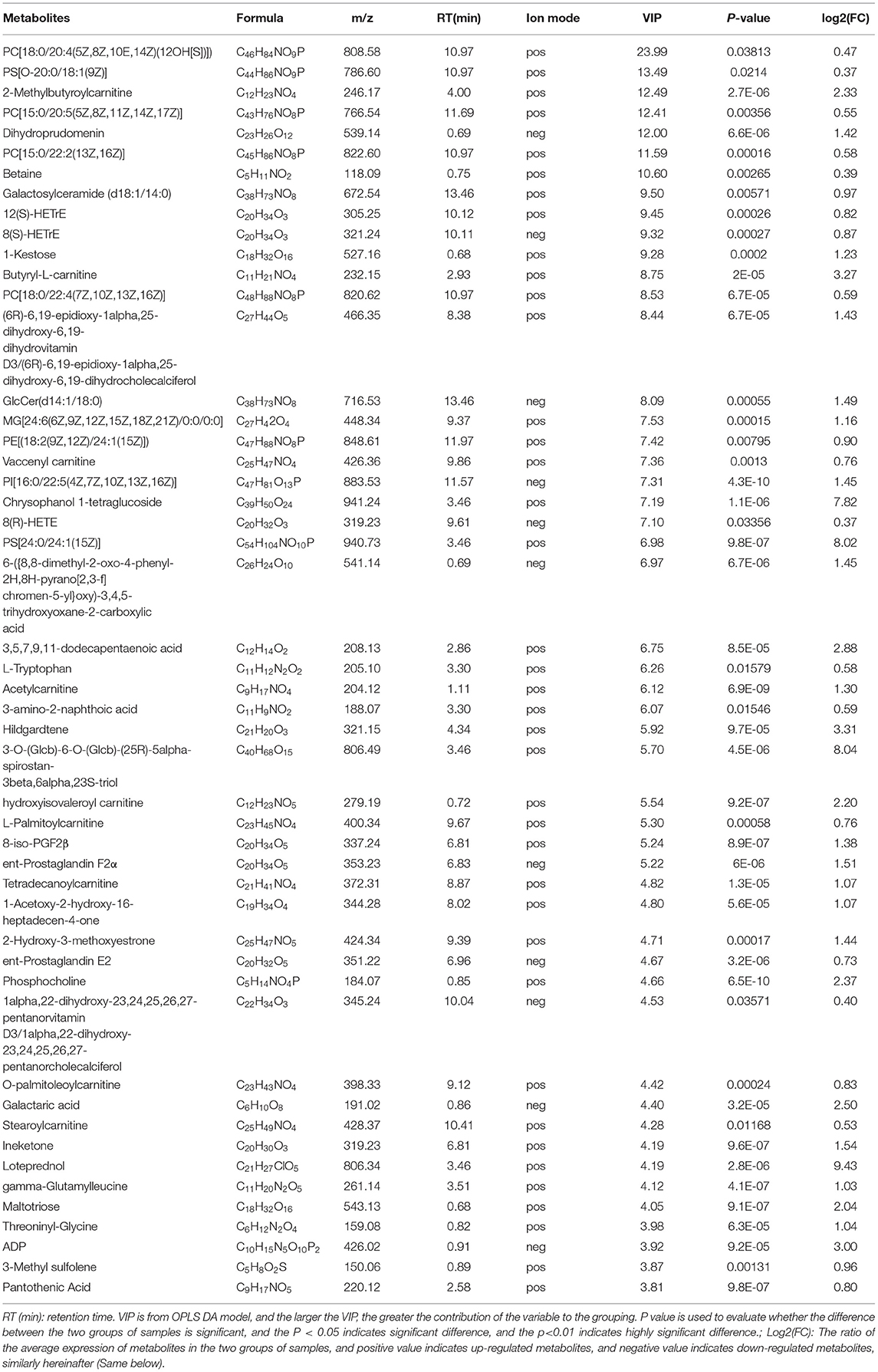

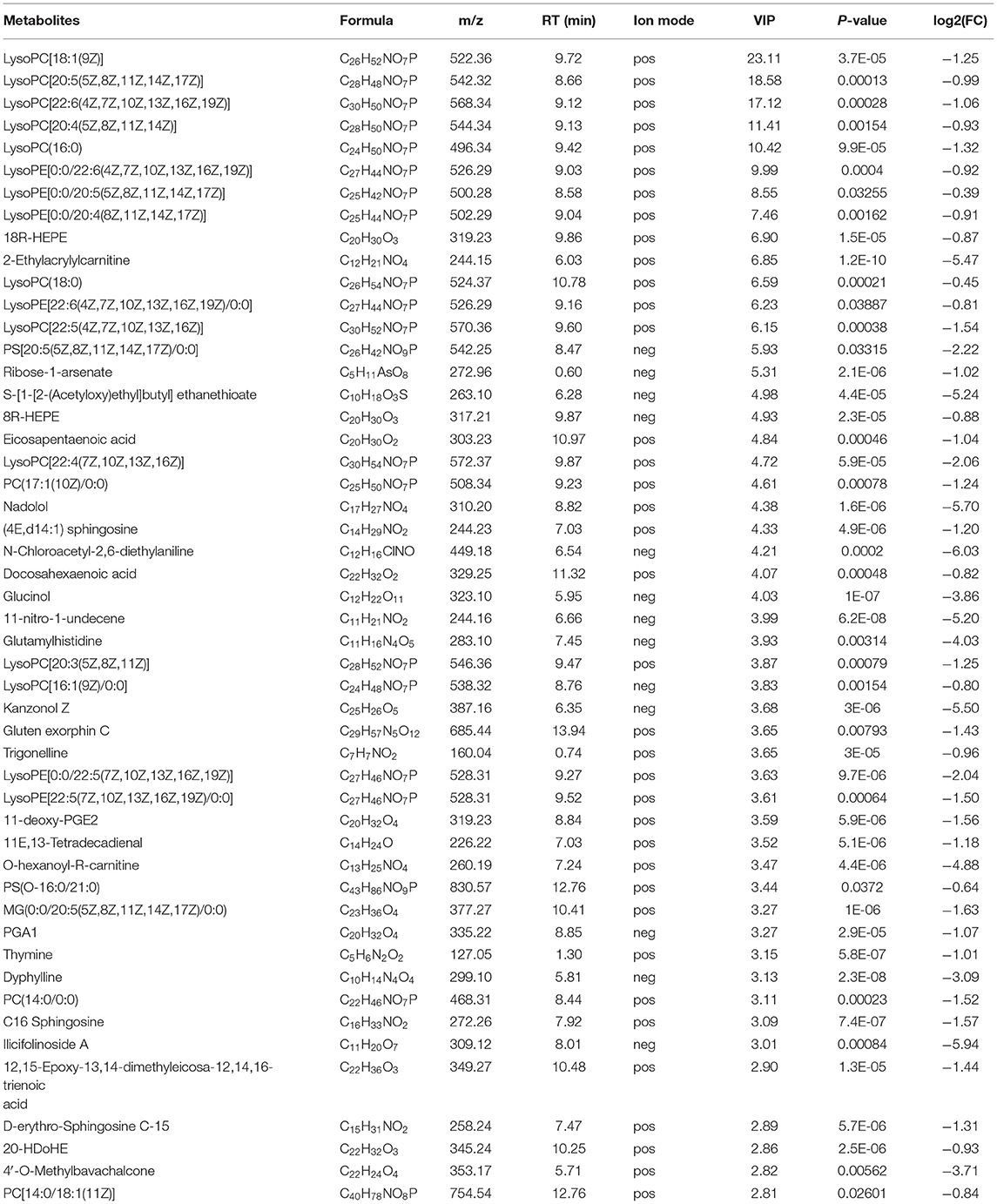

Through multi-dimensional analysis, single-dimensional analysis, and volcano map analysis (Figure 4A), the differential metabolites between the LS and CK groups were screened. The screening criteria were P < 0.05 and VIP > 1. As a result, a total of 519 different metabolites in the LS group were screened, including 288 up-regulated metabolites (Table 2) and 231 down-regulated metabolites (Table 3).

Figure 4. Volcano map of differential metabolites in LS and CK groups (A), the red origin represents the differential metabolites that are significantly up-regulated, the blue origin represents the differential metabolites that are significantly down-regulated, and the gray origin represents the insignificant differential metabolites; The pie chart of the differential metabolite classification of CK and LS in the gill tissue of S.paramamosain: Up-regulated differential metabolite (B) and up-regulated differential metabolite (C).

Up-regulated differential metabolites were found to include: phosphatidylcholine (PC) (18:0/20:4) (VIP = 23, log2(FC) = 0.47), phosphatidylserine (PS) (O-20:0/18:1) (VIP = 13.49, log2(FC) = 0.37), and PC (15:0/20:5) (VIP = 12.41, log2(FC) = 0.55) etc. 28 Glycerophospholipids, PC (18:0/20:4) is the highest VIP among all up- regulated metabolites, and its VIP value reaches 23; 2-Methylbutyroylcarnitine (VIP = 12.49, log2(FC) = 2.33), 12(S)-HETrE (VIP = 9.45, log2(FC) = 0.82) and Vaccenyl carnitine (VIP = 7.36, log2(FC) = 0.76) etc. 54 Fatty Acyls; Betaine (VIP = 10.6, log2(FC)= 0.39), gamma-Glutamylleucine (VIP = 4.12,log2(FC) = 1.03) and Threoninyl-Glycine (VIP = 3.97, log2(FC) = 1.04) etc. 34 Carboxylic acids and derivatives; 1-Kestose (VIP = 9.28, log2(FC) = 1.23), Chrysophanol 1-tetraglucoside (VIP=7.19, log2(FC) = 7.82) and Galactaric acid (VIP = 4.40, log2(FC) = 2.5) etc. 22 Organooxygen compounds; (23S,24S)-17,23-Epoxy-24,29-dihydroxy-27-norlanost-8-ene-3,15-dione (VIP = 3.76, log2(FC) = 0.81), (-)-Cassaic acid (VIP = 3.14, log2(FC) = 0.56) and Limonene-1,2-diol (VIP = 2.39, log2(FC) = 0.93) etc.13 Prenol lipids; in addition,it also contains Dihydroprudomenin (VIP = 12, log2(FC) = 1.42), Galactosy-lceramide (d18:1/14:0) (VIP = 9.5, log2(FC) = 0.97) and Butyryl-L-carnitine (VIP = 8.75, log2(FC) = 3.27) etc. 137 differential metabolites (Table 1; Figure 4B).

Table 1. Up-regulated metabolites in gills of S.paramamosain response to sudden drop in salinity from 23 to psu.

The down-regulated differential metabolties included: lysophosphatidyl-choline (LysoPC) (20:5) (VIP = 6.85, log2(FC) = −0.99), PC(o-22:1) (VIP = 5.31, log2(FC) = −4.50) and LysoPC(22:4) (VIP = 4.38, log2(FC)= −2.06) etc. 47 Glycerop-hospholipids; 10Z-Tricosene (VIP = 9.99, log2(FC) = −4.96), O-hexanoyl-R-carnitine (VIP = 7.46, log2(FC) = −4.88), Hexyl 3-mercaptobutanoate (VIP = 5.93, log2(FC) = −6.37) etc.35 Fatty Acyls; L-isoleucyl-L-proline (VIP = 4.93, log2(FC) = −1.50), Perindopril Acyl-beta-D-glucuronide (VIP = 4.61, log2(FC) = −2.05), 2-Pentanamido-3-phenylpropanoic acid (VIP= 4.33, log2(FC)= −1.54) etc. 15 Carboxylic acids and derivatives; 1 Fluocinolone acetonide (VIP=3.65, log2(FC)= −8.33), 6alpha,9alpha- Difluoroprednisolone-17-butyrate (VIP= 3.15, log2(FC)= −9.13) and 12-Ketodeoxy-cholic acid (VIP = 2.33, log2(FC) = −0.92) etc.10 Steroids and steroid derivatives; N,N'-diacetylchitobiose (VIP = 2.14, log2(FC) = −2.01), Semilepidinoside A (VIP = 1.90, log2(FC) = −1.89) and DHAP(18:0e) (VIP = 1.86, log2(FC) = −1.26) etc. 8 Organooxygen compounds; in addition,it also contains (-)-2,7-Dolabelladiene-6beta, 10alpha,18-triol (VIP=23.11, log2(FC)= −1.1.9), 15-deoxy-δ-12,14-PGD2 (VIP = 18.58, log2(FC) = −0.58) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) (16:0/0:0) (VIP = 17.12, log2(FC) = −0.36) etc. 109 other down-regulated differential metabolites were found (Table 2; Figure 4C).

Table 2. Down-regulated metabolites in gills of Scylla paramamosain response to sudden drop in salinity from 23 to 3psu.

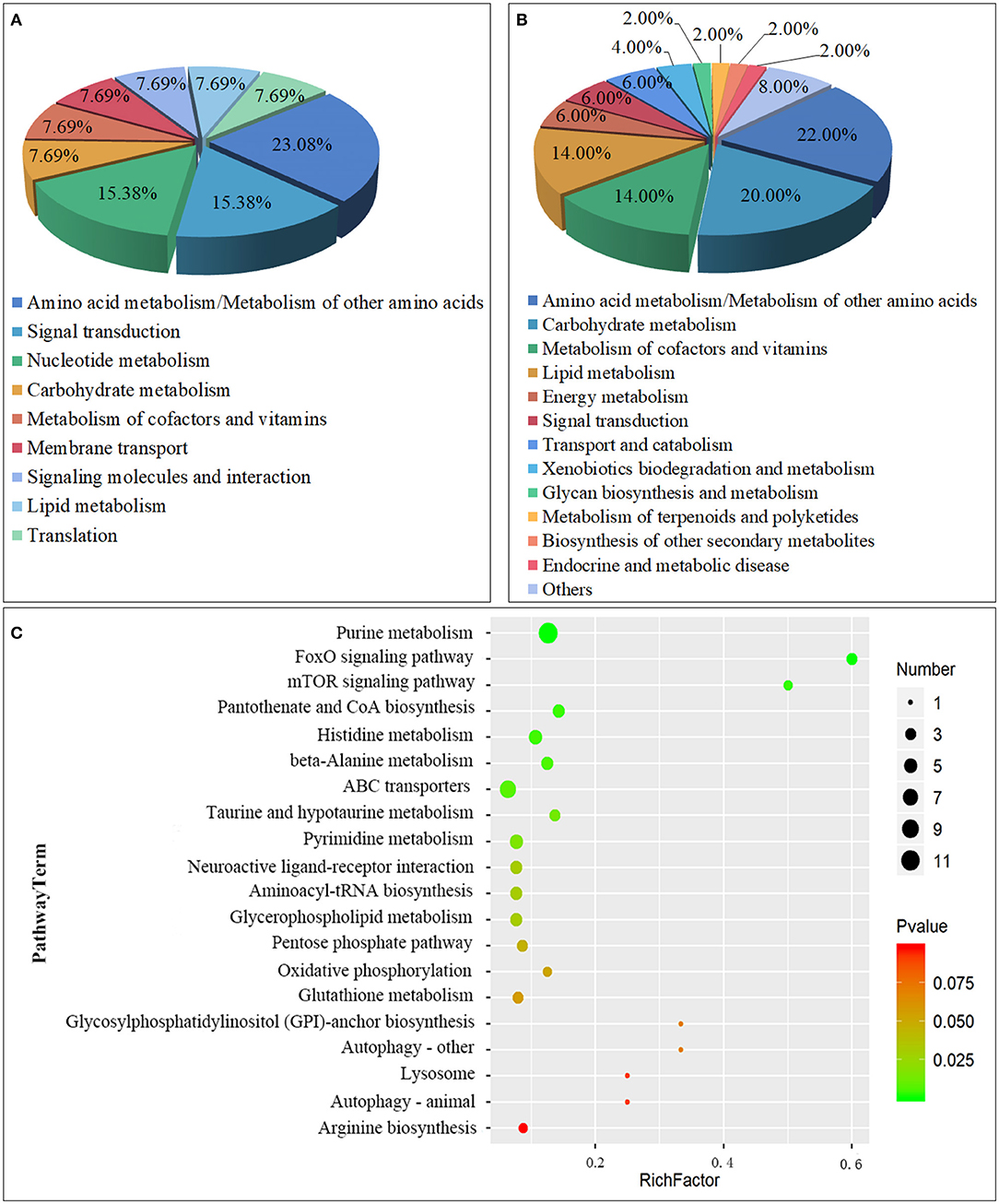

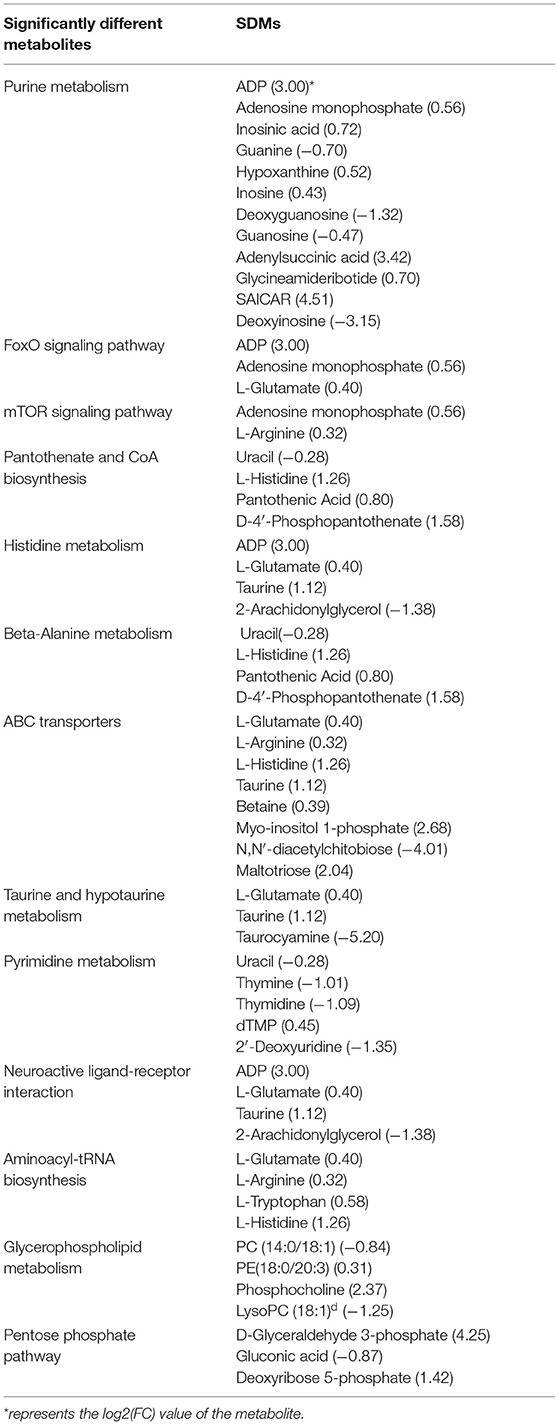

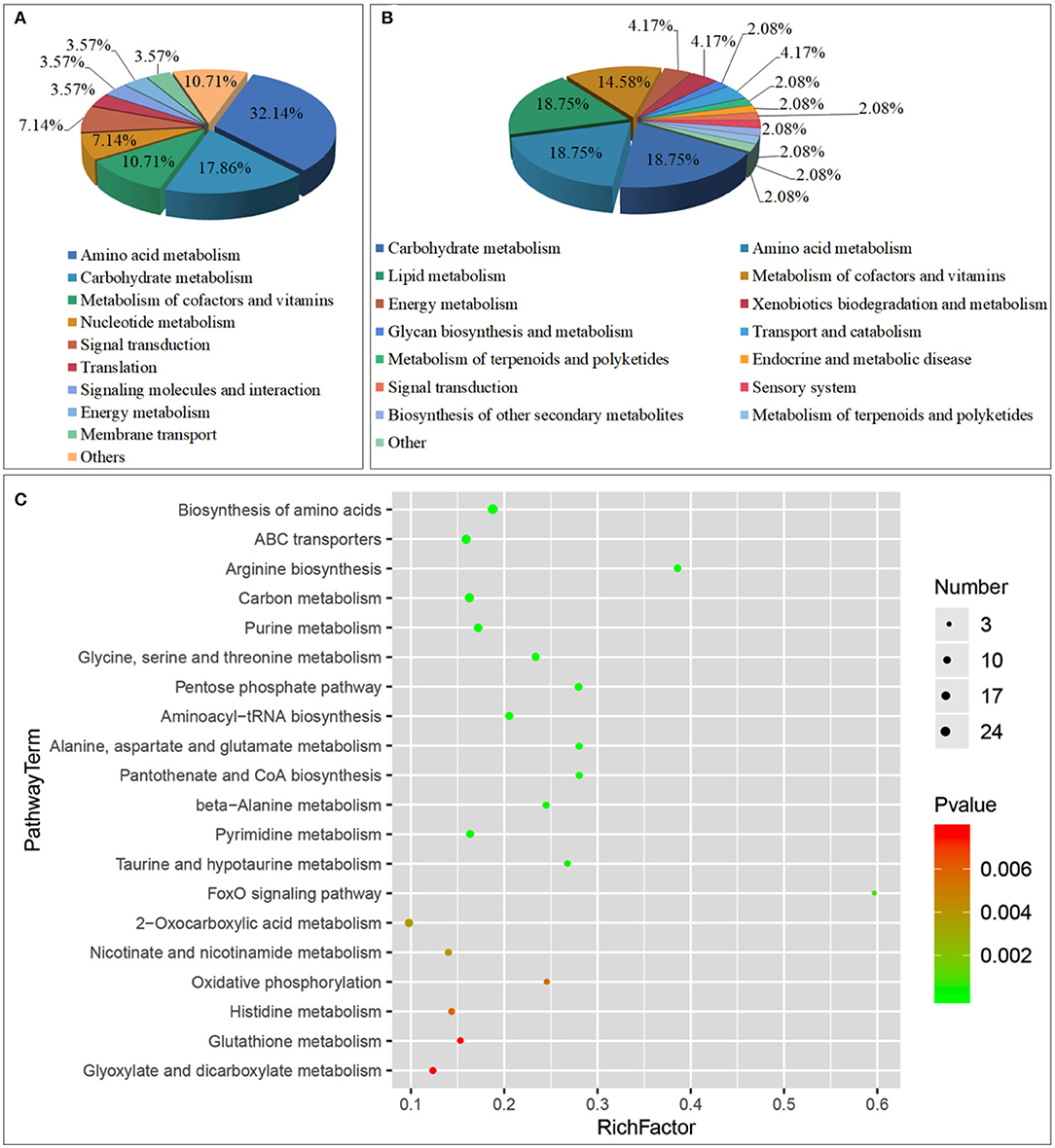

A total of 63 metabolic pathways were obtained by the analysis of the metabolic pathway enrichment of differential metabolites, of which 13 showed significant enrichment (P < 0.05) and 50 showed non-significant enrichment (P > 0.05). The 13 significant enrichment metabolic pathways are classified into amino acid metabolism/Metabolism of other amino acids (Histidine metabolism; beta-Alanine metabolism; Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism), Signal transduction (FoxO signaling pathway; mTOR signaling pathway), Carbohydrate metabolism (Pentose phosphate pathway), Metabolism of cofactors and vitamins (Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis); Nucleotide metabolism (Purine metabolism); Membrane transport (ABC transporters); Nucleotide metabolism (Pyrimidine metabolism); Signaling molecules and interaction (Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction); Lipid metabolism (Glycerophospholipid metabolism); and Translation (Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis) (Figures 5A,C; Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 5. Class of Metabolic pathway pie chart in the gill tissues of the S.paramamosain adapting to low salinity: significant enrichment (A) and non-significant enrichment (B); The metabolome view map of top 20 metabolic pathways in gills for S.paramamosain adapting to low salinity (C).

Another 50 enrichment metabolites pathways were classified as non-significant, including: Amino acid metabolism/Metabolism of other amino acids (Glutathione metabolism; Arginine biosynthesis; Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism, etc.), Carbohydrate metabolism (Butanoate metabolism; Galactose metabolism; Inositol phosphate metabolism, etc.), Metabolism of cofactors and vitamins (Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism; Vitamin B6 metabolism; Thiamine metabolism, etc.), Lipid metabolism (Sphingolipid metabolism; Synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies; Arachidonic acid metabolism, etc.), Energy metabolism (Oxidative phosphorylation; Nitrogen metabolism; Sulfur metabolism), Signal transduction (Phosphatidylinositol signaling system), Transport and catabolism (Autophagy - other; Lysosome; Autophagy - animal), Xenobiotics biodegradation and metabolism (Drug metabolism - other enzymes; Drug metabolism - cytochrome P450), Glycan biosynthesis and metabolism (Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis), Metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides (Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis), Biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites (Caffeine metabolism), Endocrine and metabolic disease (AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications), Other class (Carbon metabolism; Biosynthesis of amino acids; 2-Oxocarboxylic acid metabolism, etc.) (Figure 5B; Supplementary Table 3).

From the above classification, it is found that both significant metabolic and non-significant pathways are related mainly to amino acids, signal transduction, and energy metabolism. The top significant differential metabolic pathways are Purine metabolism (ADP; Adenosine monophosphate; Inosinic acid, etc.), FoxO signaling pathway (ADP; Adenosine monophosphate; L-Glutamate), mTOR signaling pathway (Adenosine monophosphate; L-Arginine), Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis (Uracil; L-Histidine; Pantothenic Acid, etc.), Histidine metabolism (ADP; L-Glutamate; Taurine, etc.), beta-Alanine metabolism (Uracil; L-Histidine; Pantothenic Acid, etc.), ABC transporters (L-Glutamate; L-Arginine; L-Histidine, etc.), Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism (L-Glutamate; Taurine; Taurocyamine), Pyrimidine metabolism (Uracil; Thymine; Thymidine, etc.), and Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction (ADP; L-Glutamate; Taurine, etc.) (Table 3). From the above result, Amino acid metabolism/Metabolism of other amino acids accounted for the highest proportion, reaching 23.08%, which are mainly involved in the regulation of metabolic differences of ADP, L-Glutamate, Taurine, 2-Arachidonylglycerol, Uracil, L-Histidine, Pantothenic Acid, D-4′-Phosphopantothenate, Taurocyamine; Signal transduction, and Carbohydrate metabolism also play an important role, such as participating in the regulation of ADP, Adenosine monophosphate, L-Glutamate, L-Arginine, D-Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, Gluconic acid, and Deoxyribose 5-phosphate.

Table 3. Significantly enriched metabolic pathways identified in significantly different metabolites.

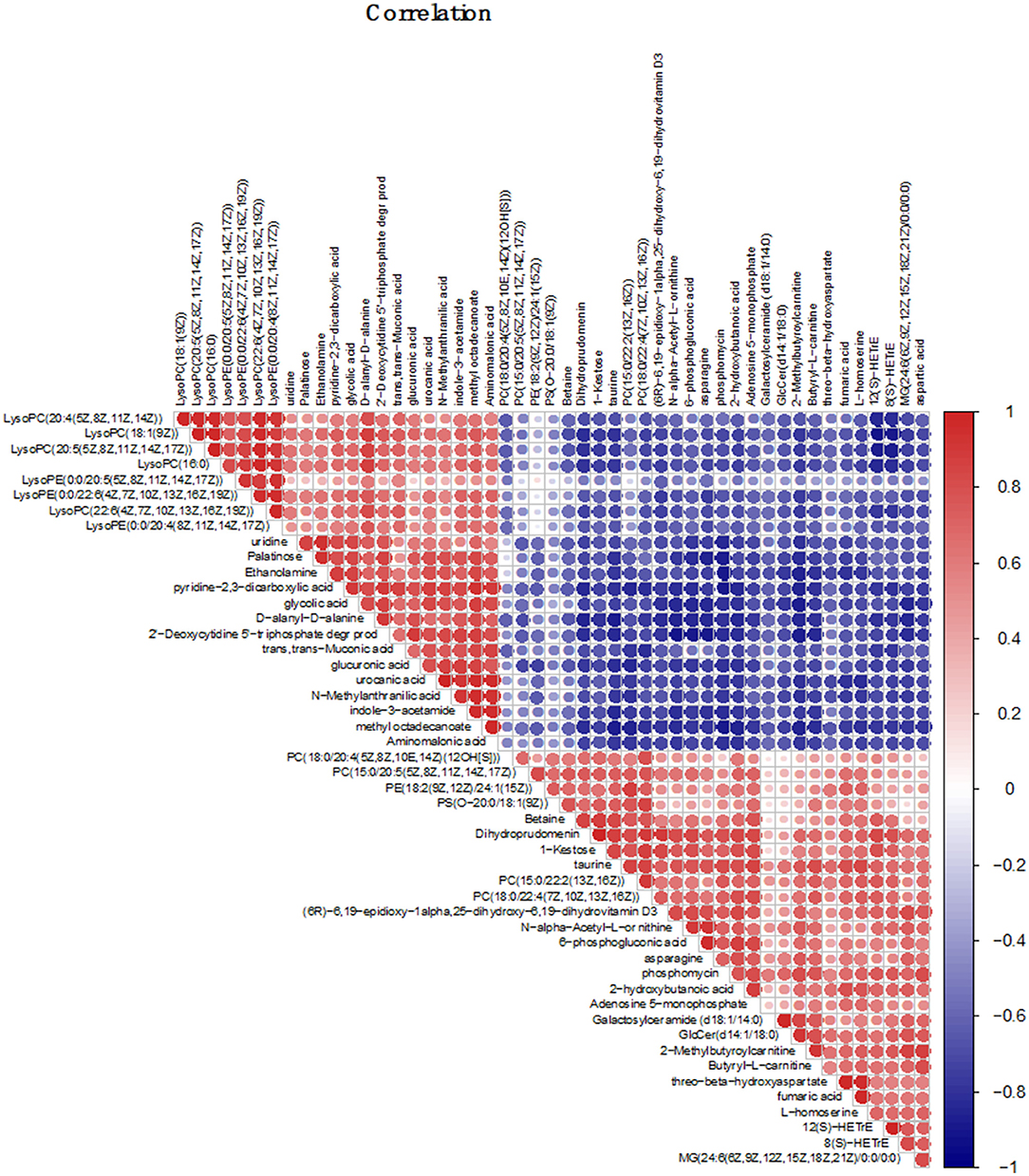

Earlier, we revealed the metabolic mechanism of S. paramamosain adapting to a low salinity base on GC-MS (Yao et al., 2020). Due to differences in the properties of metabolites detected by GC-MS and LC-MS, in order to more fully reveal the metabolic mechanism of the adaptation of S. paramamosain to low salinity, correlation analysis was performed between the two. In this study, Betaine, taurine, asparagine, and aspartic acid are all amino acids related to osmotic regulation, they are all up-regulated and there is a strong positive correlation between them. In addition, these four amino acids are combined with fumaric acid, 6-phosphogluconic acid, PC(15:0/20:5), PE(18:2), PS[O-20:0/18:1(9Z)], and other metabolites are positively correlated with LysoPC(20:4), LysoPC(18:1), LysoPC(20:5), glycolic acid, and urocanic acid, etc., they are all down-regulated, and show a strong negative correlation (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Correlation analysis chart of the top 50 different metabolites; The correlation analysis graph represents a correlation between the expression levels of different substances, the red one represents the positive correlation, and the blue one represents the negative correlation. The darker the color, the larger the dot, and the higher the correlation value.

A total of 76 pathways were screened by correlation analysis, including 28 significant differential metabolic pathways (P < 0.05). These included Amino acid metabolism (Arginine biosynthesis; Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism; Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism, etc.), Carbohydrate metabolism (Pentose phosphate pathway; Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism; Galactose metabolism, etc.), Metabolism of cofactors and vitamins (Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis; Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism; Vitamin B6 metabolism), Nucleotide metabolism (Purine metabolism; Pyrimidine metabolism), Translation (Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis), Signal transduction (FoxO signaling pathway), Signaling molecules and interaction (Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction), Energy metabolism (Oxidative phosphorylation), Membrane transport (ABC transporters), and others (Biosynthesis of amino acids; Carbon metabolism; 2-Oxocarboxylic acid metabolism) (Figures 7A,C, Table 4) and 48 non-significant differential metabolic pathways (P < 0.05) (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Class of Metabolic pathway pie chart in the gill tissues of the S.paramamosain adapting to low salinity: significant enrichment (A) and non-significant enrichment (B) in correlation analysis; the metabolome view map of top 20 significant enrichment metabolic pathways in the gill tissues of the S.paramamosain adapting to low salinity (C) in correlation analysis.

Through correlation analysis, Amino acid metabolism accounted for the highest proportion, reaching 32.14%; followed by Carbohydrate metabolism, accounting for 17.86%. The top 10 significant differential metabolic pathways (P < 0.01) are Biosynthesis of amino acids (Pyruvic acid; L-Glutamate; alpha-ketoglutaric acid, etc.), ABC transporters (Phosphate; L-Glutamate; Glycine, etc.), Arginine biosynthesis (L-Glutamate; alpha-ketoglutaric acid; aspartic acid, etc.), Carbon metabolism (Pyruvic acid; L-Glutamate; alpha-ketoglutaric acid, etc.), Purine metabolism (ADP; Adenosine 5-monophosphate; Glycine, etc.), Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism (Pyruvic acid; Glycine; aspartic acid, etc.), Pentose phosphate pathway (Pyruvic acid; ribose-5-phosphate; D-Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, etc.), Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis (L-Glutamate; Glycine; lysine, etc.), Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism (Pyruvic acid; L-Glutamate; alpha-ketoglutaric acid, etc.), and Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis (Pyruvic acid; aspartic acid; Uracil, etc.) (Supplementary Table 5).

Our results showed that the osmolality of S. paramamosain did not continuously decrease with declining environmental salinity during the adaptation process. Similar results were reported for Scylla serrate stressed by low salinity (Hulathduwa et al., 2007; Romano et al., 2014). After reaching osmotic balance, the osmolality of S. paramamosain was higher than that of the environment, likely due to a significant difference of osmotic regulator between the S. paramamosain and the environment (Chen and Chia, 1977). In our study, Na+-K+-ATPase, CA and V-ATPase activities increased in the LS group, which confirmed the effect of Na+-K+-ATPase and CA as regulators of osmotic balance in S. paramamosain (Towle and Weihrauch, 2001; Chung and Lin, 2006). Towle and Mangum (1985) previously reported that CA activity increased with increasing Na+-K+-ATPase activity, and V-ATPase has been shown to promote the osmotic balance in freshwater crustaceans, amphibians, and fish (Nelson and Harvey, 1999; Wieczorek et al., 1999; Kirschner, 2004; Beyenbach and Wieczorek, 2006). Together, the data suggested that Na+-K+-ATPase, CA, and V-ATPase were related to osmolality regulation in S. paramamosain.

This study focused on the metabolic mechanism responsible for osmolality regulation in the gills of S. paramamosain during adaptation to an acute decrease in salinity. The LC-MS results showed that glycerophospholipids accounted for most of the metabolites involved in the process, thus they putatively played a leading role in osmolality regulation. Glycerophospholipid is one type of phospholipid; it is the key component of the cell lipid phospholipid bilayer, and it plays important roles in energy metabolism and signaling conduction (Fahy et al., 2005). Other phospholipids include phosphatidic acid (PA), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS), and phosphatidylcholine (PC) (Murru et al., 2013), which perform various functions (Coutteau et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2006; Thomas et al., 2010; Hochreiter-Hufford et al., 2013). In response to salinity change, Bhoite and Roy (2013) found that the lipid composition and the intra-/intercellular ion concentration of S. serrata changed significantly. The total phospholipid content also increased significantly in the rear gills of Eriocheir sinensis after a change in salinity (Chapelle et al., 1976). Previous studies have shown that S. paramamosain transports Na+, K+, and Cl− into cells via cotransporters to regulate osmolality (Gagnon et al., 2003; Gamba, 2005; Xu et al., 2017). After the salinity decreased from 23 psu to 3 psu in our study, the metabolites of PC, PA, PE, and PS in the LS group changed significantly. These results suggested that membrane components of gill cells as well as ion transportation and amino acids were correlated with osmolality regulation in S paramamosain. However, the mechanism still requires further study.

Free amino acids are known to play a key role in adaptation to acute low salinity in S. paramamosain (Yao et al., 2020). In our study, betaine was up-regulated. Betaine is an N-methylated free amino acid that plays an important role in intracellular osmolality regulation (Lokhande et al., 2010). It also improves the osmotic regulation capability of various aquatic animals (Deaton, 2001; Saoud and Davis, 2005; Ye et al., 2014). In plants, betaine can effectively inhibit the damage to cell membranes caused by salinity (Wang et al., 2009), although this effect has not yet been reported for osmotic regulation in S. paramamosain.

In this study, 63 metabolic pathways were identified through KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/KEGG/pathway.html) enrichment analysis, and 13 pathways showed significant differences (P < 0.05). Amino acid metabolism/metabolism of other amino acids was mainly involved in the regulation of taurine, L-glutamate, L-histidine, and pantothenic acid. Glycerophospholipid metabolism was mainly involved in the regulation of PC, PE, LysoPC, and phosphocholine. The changes in betaine and taurine were mainly controlled by ABC transporters. In this study, PC was the most up-regulated phospholipid and had the highest VIP, which indicated that PC played a key role in the osmolality regulation in S. paramamosain. PC is also closely correlated with cholesterol (Brzustowicz et al., 2002), which regulates phospholipid in the membrane (Finegold, 1993; Mcmullen and Mcelhaney, 1996). Therefore, our results suggested that PC played important roles in regulating the membrane during osmolality regulation in S. paramamosain. Glycerophospholipid metabolites directly regulate the synthesis and metabolism of PC. ABC transporters belong to one of the largest protein families, and their main function is to regulate the transport of small molecules such as amino acids, ions, and sugars in biological membranes (Dawson, 2006; Hollenstein et al., 2007). Therefore, our results suggested that upon acute low salinity stress, S. paramamosain regulated the structural changes of biomembranes via glycerophospholipid metabolites, followed by transportation of amino acids and carbohydrates through biomembranes via ABCs to achieve osmotic balance inside and outside cells.

Our correlation analysis of GC-MS and LC-MS data identified 57 metabolic pathways. Among them, 28 showed significant differences (P < 0.05), and they were mainly amino acid and energy metabolic pathways Figure 7C). However, differences in glycerophospholipid metabolism pathways, such as arachidonic acid metabolism and alpha-linolenic acid metabolism, were all insignificant (Supplementary Table 4). Osmolality regulation in crustaceans is mainly regulated by amino acids and inorganic ions, and inorganic ions account for 80–90% of the regulation (Chen and Chia, 1977; Onken and Putzenlechner, 1995). Amino acid transportation includes free diffusion, assisted diffusion, and active transport, and ion transport includes free diffusion and active transportation, neither of which require protein carriers. This implies that osmolality in S. paramamosain is regulated mainly via the adjustment of concentrations of ions and amino acids. Amino acids are mostly freely diffused out of cells to maintain the osmotic equilibrium state.

Many significant metabolic pathways related to sugar metabolism and energy metabolism were identified using regardless of GC-MS/LC-MS correlation technology to study the biological mechanism by which S. paramamosain adapts to acute low salinity stress. These metabolic pathways include butanoate metabolism, galactose metabolism, inositol phosphate metabolism, fatty acid degradation, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, citrate cycle, pyruvate metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, nitrogen metabolism, and sulfur metabolism. Therefore, these energy metabolism pathways are likely involved in osmolality regulation in S. paramamosain.

In this study, S paramamosain were exposed to an acute decrease in salinity from 23 psu to 3 psu. Hemolymph osmolality decreased to 642.38 mOsm/Kg and reached the physiological equilibrium state. Na+-K+-ATPase activity in the gills, which is responsible for osmolality regulation, continuously increased from 0 to 6 h to reach 31.53 U/mL and then decreased from 24 h to reach the physiological equilibrium state (24.28 U/mL). CA and V-ATPase activities increased, reaching 16.54 U/mL and 21.88 U/mL, respectively. Using LC-MS technology, we identified 519 differential metabolites (mainly lipids), and 63 metabolic pathways were identified by KEGG enrichment analysis of differential metabolites. Thirteen of these pathways showed significant differences (P < 0.05), including the FoxO signaling pathway, glycerophospholipid metabolism, and ABC transporters as well as signaling pathways, lipids, and transport-related pathways. Numerous studies have shown that lipids play a key role in osmolality regulation in S. paramamosain, and energy metabolism involving carbohydrates provides sufficient energy to adapt to an acute decrease in salinity. We conducted correlation analysis with combined LC-MS and GC-MS data (Yao et al., 2020) and found that 28 of 57 metabolic pathways showed a significant difference (P < 0.05). These pathways included arginine biosynthesis, pentose phosphate, and ABC transporters. Among them, amino acids and energy metabolism accounted for the largest proportion, whereas lipid metabolism was absent. These results showed that amino acids and energy dominated the process by which S. paramamosain adapted to an acute decrease in salinity and that lipid metabolites played only a supportive role.

In this study, we explored the role and relationship of lipids and amino acids in the adaptation of S. paramamosain to an acute decrease in salinity. For the first time, we elucidated the mechanism of cellular osmolality regulation, which occurred via the transport of substances through the cell membrane. Our results can be used to devise an emergency strategy to respond to acute salinity reduction in the culture environment and to improve aquaculture technology in inland low salinity environments. Therefore, in the process of breeding S. paramamosain, enriching the feed with a certain amount of taurine and betaine or enhancing the metabolic pathways through related products may improve the ability of S. paramamosain to adapt to acute low salt.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The animal subjects used in the present study are crabs, which are invertebrates and are exempt from this requirement.

HW conceived and designed the study. HY, YC, GL, and GG took samples of experimental animals. HY, XL, HW, CW, and CM performed and analyzed all the other experiments. HY and HW wrote the manuscript with support from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFD0900203); Basic Public Welfare Research Program of Zhejiang Province (No. LY20D060001), 2025 Technological Innovation for Ningbo (2019B10010), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA, the K. C. Wong Magna Fund in Ningbo University. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aside from funding support, we also thank oebiotech (oebiotech, Shanghai, China) for sequencing consultation and support.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.734519/full#supplementary-material

Anger, K., Riesebeck, K., and Püschel, C. (2000). Effects of salinity on larval and early juvenile growth of an extremely euryhaline crab species, Armases miersii (Decapoda: Grapsidae). Hydrobiologia 426, 161–168. doi: 10.1023/A:1003926730312

Araújo, A. M., Bastos, M. L., Fernandes, E., Carvalho, F., Carvalho, M., and Paula, G. (2018). GC-MS metabolomics reveals disturbed metabolic pathways in primary mouse hepatocytes exposed to subtoxic levels of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA). Arch. Toxicol. 92, 3307–3323. doi: 10.1007/s00204-018-2314-9

Beyenbach, K., and Wieczorek, H. (2006). The V-type H+-ATPase: molecular structure and function, physiological roles and regulation. J. Experim. Biol. 209, 577–589. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02014

Bhoite, S., and Roy, R. (2013). Role of membrane lipid in osmoregulatory processes during salinity adaptation: a study with chloride cell of mud crab, Scylla serrata. Mar. Freshw. Behav. Physiol. 46, 287–300. doi: 10.1080/10236244.2013.832525

Brzustowicz, M. R., Cherezov, V., Caffrey, M., Stillwell, W., and Wassall, S. R. (2002). Molecular organization of cholesterol in polyunsaturated membranes: microdomain formation. Biophys. J. 82, 285–298. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75394-0

Chapelle, S., Dandrifosse, G., and Zwingelstein, G. (1976). Metabolism of phospholipids of anterior or posterior gills of the crab Eriocheir sinensis M. EDW, during the adaptation of this animal to media of various salinities. Int. J. Biochemistr. 7, 343–351. doi: 10.1016/0020-711X(76)90097-5

Chen, J. C., and Chia, P. G. (1977). Osmotic and ionic concentration of Scylla serrata (Forskål) subjected to different salinity levels. Comparat. Biochem. Physiol. 117, 239–244. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9629(96)00237-X

Chung, K. F., and Lin, H. C. (2006). Osmoregulation and Na+, K+-ATPase expression in osmoregulatory organs of Scylla paramamosain. Comparat. Biochemistr. Physiol. Part A Molecul. Integrat. Physiol. 144, 48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.02.003

Coutteau, P., Kontara, E. K. M., and Sorgeloos, P. (2000). Comparison of phosphatidylcholine purified from soybean and marine fish roe in the diet of postlarval Penaeus vannamei Boone. Aquaculture 181, 331–345. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(99)00238-0

Dawson, R. J., and Locher, K. P. (2006). Structure of a bacterial multidrug ABC, transporter. Nature 443, 180–185. doi: 10.1038/nature05155

Deaton, L. E. (2001). Hyperosmotic volume regulation in the gills of the ribbed mussel, Geukensia demissa: rapid accumulation of betaine and alanine. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 260, 185–197. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(01)00237-4

Dooley, P. C., Long, B. M., and West, J. M. (2000). Amino acids in haemolymph, single fibres and whole muscle from the claw of freshwater crayfish acclimated to different osmotic environments. Comparat. Biochemistr. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integrat. Physiol. 127, 155–165. doi: 10.1016/S1095-6433(00)00247-6

Fahy, E., Subramaniam, S., Brown, H. A., Glass, C. K., Jr, M. A. H., Murphy, R. C., et al. (2005). A comprehensive classification system for lipids. J. Lipid Res. Vol. 46, 839–861. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E400004-JLR200

Finegold, L. (1993). Cholesterol in membrane models [M] Cholesterol in Membrane Models. Boca Raton, FL: CRC press.

Freire, C. A., Onken, H., and Mcnamara, J. C. (2008). A structure-function analysis of ion transport in crustacean gills and excretory organs. Comparat. Biochemistr. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integrat. Physiol. 151, 272–304. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.05.008

Gagnon, E., Forbush, B., Caron, L., and Isenring, P. (2003). Functional comparison of renal Na+-K+-Cl− cotransporters between distant species. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 284, 365–370. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00262.2002

Gamba, G. (2005). Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of electroneutral cationchloride cotransporters. Physiol. Rev. 85, 423–493. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2004

Henry, R. P. (2001). Environmentally mediated carbonic anhydrase induction in the gills of euryhaline crustaceans. J. Experim. Biol. 204, 991–1002. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.5.991

Hill, B. J. (1994). Offshore spawning by the portunid crab Scylla serrata (Crustacea: Decapoda). Mar. Biol. 120, 379–384. doi: 10.1007/BF00680211

Hochreiter-Hufford, A. E., Lee, C. S., Kinchen, J. M., Sokolowski, J. D., Arandjelovic, S., Call, J. A., et al. (2013). Phosphatidylserine receptor BAI1 and apoptotic cells as new promoters of myoblast fusion. Nature 497, 263–267. doi: 10.1038/nature12135

Hollenstein, K., Frei, D. C., and Locher, K. P. (2007).Structure of an ABC transporter in complex with its binding protein. Nature 446, 213–216. doi: 10.1038/nature05626

Huang, H., Huang, C., Guo, L., Zeng, C., and Ye, H. (2019). Profiles of calreticulin and Ca2+ concentration under low temperature and salinity stress in the mud crab, Scylla paramamosain. Public Library Sci. 14:e0220405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220405

Hulathduwa, Y. D., Stickle, W. B., and Brown, K. M. (2007). The effect of salinity on survival, bioenergetics and predation risk in the mud crabs Panopeus simpsoni and Eurypanopeus depressus. Mar. Biol. 152, 363–370. doi: 10.1007/s00227-007-0687-z

Kirschner, L. B. (2004). The mechanism of sodium chloride uptake in hyperregulating aquatic animals. J. Experim. Biol. 207, 1439–1452. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00907

Leone, F. A., Garçon, D. P., Lucena, M. N., Faleiros, R. O., Azevedo, S. V., Pinto, M. R., et al. (2015). Gill-specific (Na+, K+)-ATPase activity and alpha-subunit mRNA expression during low-salinity acclimation of the ornate blue crab Callinectes ornatus (Decapoda, Brachyura). Comparat. Biochem. Physiol. Part B. Biochemistr. Mol. Biol. 186, 59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2015.04.010

Lokhande, V. H., Nikam, T. D., and Penna, S. (2010). Differential osmotic adjustment to iso-osmotic NaCl and PEG stress in the in vitro cultures of Sesuvium portulacastrum (L.) L. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 13, 251–256. doi: 10.1007/s12892-010-0008-9

Long, X. W., Wu, X. G., Zhao, L, Ye, H. H., Cheng, Y. X., and Zeng, C. S. (2018). Physiological responses and ovarian development of female Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis subjected to different salinity conditions. Front. Physiol. 8:1072. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.01072

Lu, J. Y., Shu, M. A., Xu, B. P., Liu, G. X., Ma, Y. Z., Guo, X. L., et al. (2015). Mud crab Scylla paramamosain glutamate dehydrogenase: molecular cloning, tissue expression and response to hyposmotic stress. Fisher. Sci. 81, 175–186. doi: 10.1007/s12562-014-0828-5

Lv, J. J., Liu, P., Wang, Y., Gao, B. Q., Chen, P., and Li, J. (2013). Transcriptome analysis of Portunus trituberculatus in response to salinity stress provides insights into the molecular basis of osmoregulation. Public Library Sci. 8:e82155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082155

Mcmullen, T. P. W., and Mcelhaney, R. N. (1996). Physical studies of cholesterol-phospholipid interactions. Curr. Opini. Colloid Interface Sci. 1, 83–90. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0294(96)80048-3

Mcnamara, J. C., Rosa, J. C., Greene, L. J., and Augusto, A. (2004). Free amino acid pools as effectors of osmostic adjustment in different tissues of the freshwater shrimp Macrobrachium olfersii (crustacea, decapoda) during long-term salinity acclimation. Mar. Freshw. Behav. Physiol. 37, 193–208. doi: 10.1080/10236240400006208

Murru, E., Banni, S., and Carta, G. (2013). Nutritional properties of dietary omega-3-enriched phospholipids. BioMed Res. Int. 13, 1–14. doi: 10.1155/2013/965417

Nelson, N., and Harvey, W. R. (1999). Vacuolar and plasma membrane protonadenosinetriphosphosphatases. Physiol. Rev. 79, 361–385. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.361

Nurdiani, R., and Zeng, C. (2007). Effects of temperature and salinity on the survival anddevelopment of mud crab, Scylla serrata (Forsskål), larvae. Aquaclt. Res. 38, 1529–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2007.01810.x

Onken, H., and Putzenlechner, M. (1995). A V-ATPase drives active, electrogenic and Na+-independent Cl− absorption across the gills of Eriocheir sinensis. J. Experiment. Biol. 198, 767–774. doi: 10.1242/jeb.198.3.767

Pan, L. Q., Zhang, L. J., and Liu, H. Y. (2007). Effects of salinity and pH on ion-transport enzyme activities, survival and growth of Litopenaeus vannamei postlarvae. Aquaculture 237, 711–720. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2007.07.218

Parado-Estepa, F. D., and Quinitio, E. T. (2011). Influence of salinity on survival and molting in early stages of three species of Scylla crabs. Bamidgeh 63, 1–6.

Péqueux, A. (1995). Osmotic regulation in crustaceans. J. Crustacean Biol. 15, 1–60. doi: 10.2307/1549010

Romano, N., Wu, X. G., Zeng, C. S., Genodepa, J., and Elliman, J. (2014). Growth, osmoregulatory responses and changes to the lipid and fatty acid composition of organs from the mud crab, Scylla serrata, over a broad salinity range. Marine Biol. Res. 10, 460–471. doi: 10.1080/17451000.2013.819981

Romano, N., and Zeng, C. S. (2012). Osmoregulation in decapod crustaceans: implications to aquaculture productivity, methods for potential improvement and interactions with elevated ammonia exposure. Aquaculture 334, 12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.12.035

Saoud, I. P., and Davis, D. A. (2005). Effects of betaine supplementation to feeds of pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei reared at extreme salinities. N. Am. J. Aquac. 67, 351–353. doi: 10.1577/A05-005.1

Scavia, D., Field, J. C., Boesch, D. F., Buddemeier, R. W., Burkett, V., Cayan, D. R., et al. (2002). Climate change impacts on U.S. Coast. Marine Ecosyst. 25, 149–164. doi: 10.1007/BF02691304

Shinji, J., Okutsu, T., Jayasankar, V., Jasmani, S., and Wilder, M. N. (2012). Metabolism of amino acids during hyposmotic adaptation in the whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Amino Acids 43, 1945–1954. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1266-2

Stefanuto, P. H., Perrault, K. A., Lloyd, R. M., Stuart, B., Rai, T., Forbes, S. L., et al. (2015). Exploring new dimensions in cadaveric decomposition odour analysis. Analytic. Methods 7, 2287–2294. doi: 10.1039/C5AY00371G

Thomas, A., Déglon, J., Lenglet, S., Mach, F., Mangin, P., Wolfender, J. L., et al. (2010). High-throughput phospholipidic fingerprinting by online desorption of dried spots and quadrupole-linear ion trap mass spectrometry: evaluation of atherosclerosis biomarkers in mouse plasma. Anal. Chem. 82, 6687–6694. doi: 10.1021/ac101421b

Towle, D. W., and Mangum, C. P. (1985). Ionic Regulation and transport atpase activities during the molt cycle in the blue crab Callinectes sapidus. J. Crustac. Biol. 15, 216–222. doi: 10.2307/1547868

Towle, D. W., and Weihrauch, D. (2001). Osmoregulation by gills of euryhaline crabs: molecular analysis of transporters. Am. Zool. 41, 770–780. doi: 10.1093/icb/41.4.770

Tsai, J. R., and Lin, H. C. (2007). V-type H+-ATPase and Na+, K+-ATPase in the gills of 13 euryhaline crabs during salinity acclimation. J. Experim. Biol. 210, 620–627. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02684

Vay, L. L., Ut, V. N., and Walton, M. (2007). Population ecology of the mud crab Scylla paramamosain (Estampador) in an estuarine mangrove system; a mark-recapture study. Mar. Biol. 151, 1127–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00227-006-0553-4

Wang, H., Tang, L., Wei, H. L., Lu, J. K., Mu, C. K., and Wang, C. L. (2018a). Transcriptomic analysis of adaptive mechanisms in response to sudden salinity drop in the mud crab, Scylla paramamosain. BMC Genom. 19:421. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4803-x

Wang, H., Wei, H. L., Tang, L., Lu, J. K., Mu, C. K., and Wang, C. L. (2018b). A proteomics of gills approach to understanding salinity adaptation of Scylla paramamosain. Gene 677, 119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.07.059

Wang, H., Wei, H. L., Tang, L., Lu, J. K., Mu, C. K., and Wang, C. L. (2018c). Identification and characterization of miRNAs in the gills of the mud crab (Scylla paramamosain) in response to a sudden drop in salinity. BMC Genom. 19:609. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4981-6

Wang, H., Wei, H. L., Tang, L., Lu, J. K., Mu, C. K., and Wang, C. L. (2019). Gene Identification and Characterization of Correlations for DEPs_DEGs Same Trend Responding to Salinity Adaptation in Scylla paramamosain. Int. J. Genom. 11, 1–12. doi: 10.1155/2019/7940405

Wang, X., Devaiah, S. P., Zhang, W., Zhang, W., and Welti, R. (2006). Signaling functions of phosphatidic acid. Prog. Lipid Res. 45, 250–278. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.01.005

Wang, Y. X., Zhang, B., and Wang, T. (2009). Effects of salt stress on cell membrane permeability, chlorophylls and betaine concentration in lucerne. Pratacult. Sci. 26, 53–56.

Weihrauch, D., Morris, S., and Towle, D. W. (2004). Ammonia excretion in aquatic and terrestrial crabs. J. Experiment. Biol. 207, 4491–4504. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01308

Whiteley, N. M. (2011). Physiological and ecological responses of crustaceans to ocean acidification. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 430, 257–271. doi: 10.3354/meps09185

Wieczorek, H., Grüber, G., Harvey, W. R., Huss, M., and Merzendorfer, H. (1999). The plasma membrane H+-V-ATPase from tobacco hornworm midgut. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 31:67. doi: 10.1023/A:1005448614450

Xu, B. P., Tu, D. D., Yan, M. C., Shu, M. A., and Shao, Q. J. (2017). Molecular characterization of a cDNA encoding Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter in the gill of mud crab (Scylla paramamosain) during the molt cycle: Implication of its function in osmoregulation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol,. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 203, 115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.08.019

Yao, H., Li, X., Tang, L., Wang, H., Wang, C. L., Mu, C. K., et al. (2020). Metabolic mechanism of the mud crab (Scylla paramamosain) adapting to salinity sudden drop based on GC-MS technology. Aquacult. Rep. 18:100533. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2020.100533

Keywords: Scylla paramamosain, LC-MS/GC-MS, acute hyposalt, osmotic adjustment, metabolic mechanism

Citation: Yao H, Li X, Chen Y, Liang G, Gao G, Wang H, Wang C and Mu C (2021) Metabolic Changes in Scylla paramamosain During Adaptation to an Acute Decrease in Salinity. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:734519. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.734519

Received: 01 July 2021; Accepted: 23 September 2021;

Published: 02 November 2021.

Edited by:

Francesco Fazio, University of Messina, ItalyReviewed by:

Xiaodan Wang, East China Normal University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Yao, Li, Chen, Liang, Gao, Wang, Wang and Mu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huan Wang, d2FuZ2h1YW4xQG5idS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.