- 1Canadian Integrated Ocean Observing System - Atlantic, Ocean Frontier Institute, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

- 2The Canadian Canoe Museum, Peterborough, ON, Canada

- 3Coastal and Ocean Information Network - Atlantic (COINAtlantic), Halifax, NS, Canada

- 4School of Information Management, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

Understanding and management of the marine environment requires respect for, and inclusion of, Indigenous knowledge, cultures, and traditional practices. The Aha Honua, an ocean observing declaration from Coastal Indigenous Peoples, calls on the ocean observing community to “formally recognize the traditional knowledge of Indigenous peoples,” and “to learn and respect each other’s ways of knowing.” Ocean observing systems typically adopt open data sharing as a core principle, often requiring that data be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR). Without modification, this approach to Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) would mean disregarding historical and ongoing injustices and imbalances in power, and information management principles designed to address these wrongs. Excluding TEK from global ocean observing is not equitable or desirable. Ocean observing systems tend to align with settler geography, but their chosen regions often include Indigenous coastal-dwelling communities that have acted as caretakers and stewards of the land and ocean for thousands of years. Achieving the call of Aha Honua will require building relationships that recognize Indigenous peoples play a special role in the area of ocean stewardship, care, and understanding. This review examines the current understanding of how Indigenous TEK can be successfully coordinated or utilized alongside western scientific systems, specifically the potential coordination of TEK with ocean observing systems. We identify relevant methods and collaborative projects, including cases where TEK has been collected, digitized and the meta(data) has been made open under some or all the FAIR principles. This review also highlights enabling factors that notably contribute to successful outcomes in digitization, and mitigation measures to avoid the decontextualization of TEK. Recommendations are primarily value- and process-based, rather than action-based, and acknowledge the key limitation that this review is based on extant written knowledge. In cases where examples are provided, or local context is necessary to be concrete, we refer to a motivating example of the nascent Atlantic Regional Association of the Canadian Integrated Ocean Observing System and their desire to build relationships with Indigenous communities.

Introduction

The essence of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is a living understanding of how the world works. TEK is a unique form of knowledge due in part to its relationship-based processes. Unlike the objectivity of western scientific1 ways of knowing, TEK acknowledges that people hold close relationships with all living beings, making them inseparable from the natural environment. Most common definitions emphasize that “Traditional Ecological Knowledge represents the collective knowledge of all people from a (tribal) area that has come through generations over time” (Living Traditions, 2013). Others note that TEK is a feeling of responsibility for future generations, explaining that we “owe thanks to everything that comes before us.”

Traditional Ecological Knowledge is not simply a way of understanding how the world works, nor is it easily bounded or quantified in the same way as western scientific ways of knowing. TEK is embodied by many different principles and values that may vary based on the knowledge holder. Some of the most common principles include responsibility, respect, reciprocity and connectivity to each other and the environment. Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge recognizes that Indigenous people, as the original caretakers, hold unique relationships with the land and waters. These relationships make TEK difficult to define, as Traditional Knowledge means something different to each person, each community, and each caretaker2. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples begins by reminding readers that “respect for Indigenous knowledge, cultures and traditional practices contributes to sustainable and equitable development and proper management of the environment” (United Nations General Assembly Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [UNDRIP], 2007).

The ocean contributes substantially to human wellbeing, and while it demonstrates remarkable resilience to human impacts, it is not unchanged. Whether critically informing our understanding of climate change, or protecting marine ecosystem health, or building a Blue Economy, our understanding of the ocean is crucial (Tanhua et al., 2019). The Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) typifies regional ocean observing approaches in adopting core principles that include user-centric design, sustained long-term observations, consistent standards and best practices, capacity building, and open data sharing for shared benefits (Tanhua et al., 2019). Recognizing that ocean observing systems have not always engaged with Indigenous communities, Indigenous delegates from Canada, the United States, Hawaii, the South Pacific Islands, and New Zealand issued the Aha Honua. It calls for observing systems “to establish meaningful partnerships with Indigenous communities, organizations, and Nations to learn and respect each other’s ways of knowing” (Indigenous Delegates at OceanObs’19, 2019). We cannot achieve equity and inclusion in the management of marine resources without an understanding of the ocean that includes learning to respect other ways of knowing and working together to establish meaningful partnerships. Understanding how to achieve this requires an examination of historic injustice and power imbalances, while also examining successful approaches that position western scientific data alongside traditional ecological knowledge.

As part of our own commitment to answering the call of Aha Honua, the authors undertook this review of scholarly and gray literature to:

(1) Locate and examine cases where TEK has been incorporated into a data system (collected, stored in digital form, and the metadata or data made open under some or all of the FAIR principles);

(2) Identify and explore risks and limitations with the incorporation of TEK into data systems;

(3) Identify the important enabling factors that notably contributed to successful outcomes; and

(4) Provide value- and process-based recommendations for observing systems to consider.

The scope of this review is itself complex, and potentially controversial. There are differing opinions and values held about sharing and accessing Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Some of the most notable concerns with the digitization of TEK include sensitivity of data, intellectual property ownership, consultation protocols, decontextualization of Indigenous knowledge systems and the risk of reinforcing colonial narratives; these concerns are explored further in this review, but it is important to note that for some communities, it may not be possible to resolve these concerns. Non-Indigenous researchers have a history of undertaking extractive, Eurocentric and unethical approaches to engaging with Indigenous communities, causing an understandable lack of trust (Wiwchar, 2000; Barber and Jackson, 2015). Some Indigenous scholars argue that TEK should not be digitized at all, as the risks of decontextualization are too high (Duarte et al., 2017). We acknowledge and respect these legitimate concerns. In such situations, we urge observing systems to consider how to clearly communicate the resulting incompleteness of their data resources. We urge decision-makers to systematically ensure they look beyond typical ocean observing data data to incorporate TEK in decision-making processes. Consideration of these concerns is included throughout this review.

We first describe our approach to this review, including our example ocean observing system that will allow us to provide concrete examples (see Section “Methods”). We then place the interactions between research institutions and Indigenous peoples in historical context (see Section “Historic Context”). We describe TEK in more detail, including frameworks for considering TEK, cases of successful collaborations around TEK, and general approaches for engaging with Indigenous communities around TEK (see Section “TEK Frameworks and Methods”). Finally, we synthesize a description of key challenges and recommendations in Section “Discussion: Best Practices for Navigating the Challenges of Including TEK.”

Methods

This review considered a variety of sources, including gray literature, documentaries, scholarly peer-reviewed articles, book chapters, videos, and books. Only drawing from peer-reviewed sources would have limited the research to a western-scientific realm and cut out many of the valuable Indigenous perspectives that comprise this review. Limiting the review to only literature would fail to recognize the oral nature of TEK, so various sources were considered including videos and conversations. For the same reason, we did not conduct a formal scoping or systematic review. Instead, all sources were screened for relevance to the above objectives, and we deliberately sought sources from different disciplines, fields, and projects that explore collaborative research methods. This included reviewing and exploring different case studies that utilized collaborative approaches to research while simultaneously acknowledging Indigenous intellectual rights. We conducted a specific search for digitization or mapping exercises that successfully integrated TEK in an ethical and reciprocal way.

To concretize our review and synthesis, and to anchor it to a place in the world, we will describe our results using a motivating example of a new ocean observing system building an Indigenous engagement strategy. While our review considered TEK in a broader context, we are most confident in its relevance to ocean observing in Turtle Island (North America).

Motivating Example: The Atlantic Regional Association of the Canadian Integrated Ocean Observing System

Local Traditional Knowledge, Place-Based Knowledge and Traditional Ecological Knowledge are terms that have often been used interchangeably to describe a body of knowledge that encompasses people’s relationship to place. Place plays an important role in understanding TEK, because it relates to how people interact with and understand the natural world at a localized level. The context, terminology, needs, perspectives, relationships, and myriad other factors vary by region and community. This review was conducted with a particular context in mind, which informs and limits the generality of the information and recommendations in the review.

The Atlantic Regional Association of the Canadian Integrated Ocean Observing System (CIOOS Atlantic) operates on the Atlantic Seaboard in the traditional territory of the Mi’kmaq, Innu, Wolastoqiyik, Peskotomuhkati, Nunatsiavut, Southern Inuit of NunatuKavut and in the ancestral homelands of the Mi’kmaq and Beothuk3. Each of these respective Indigenous peoples hold unique relationships with the natural environment in the form of cultural, ecological and historical teachings (these teachings are TEK in this context).

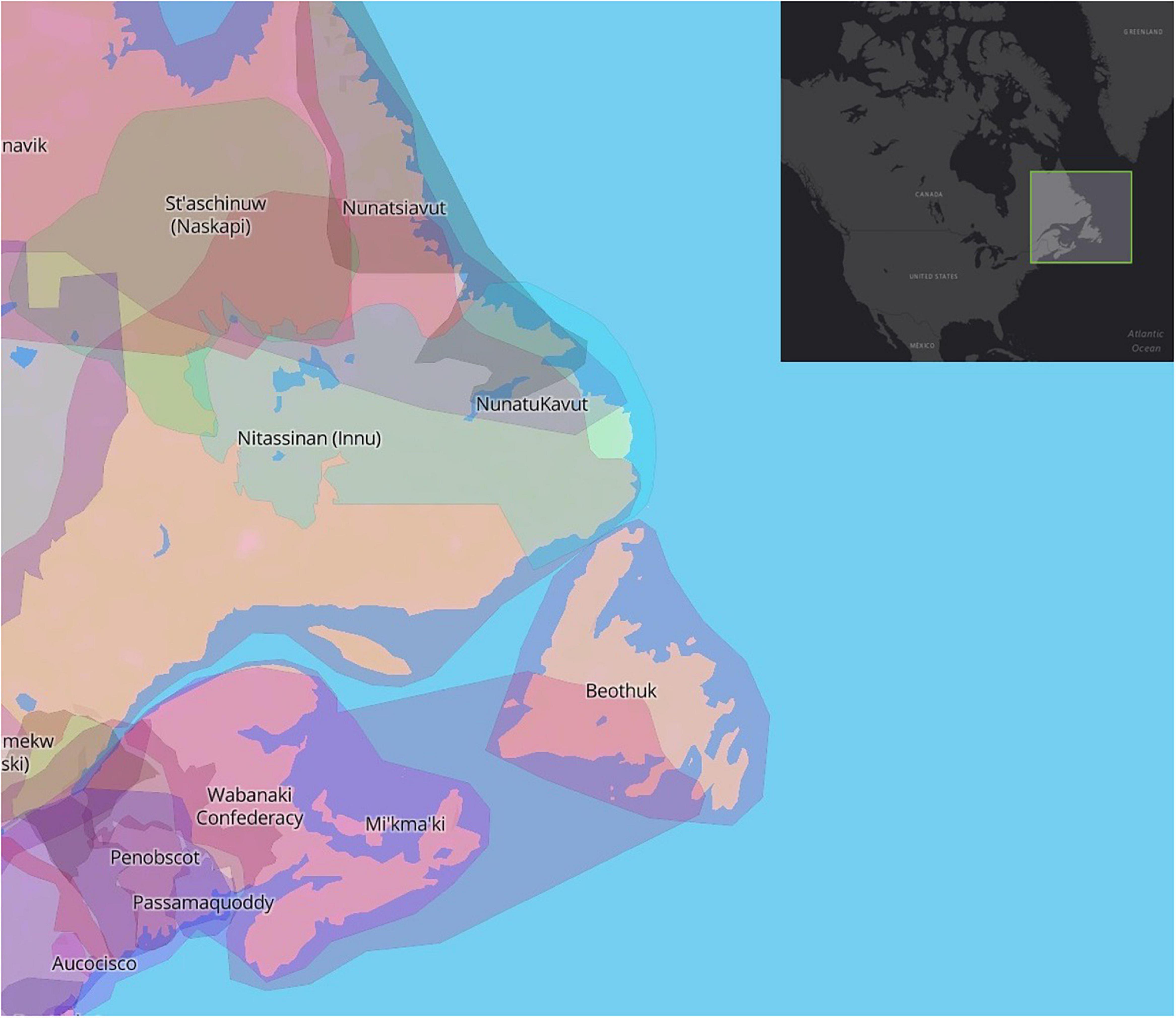

CIOOS Atlantic is defined by its relationship to the coastal environment, incorporating the Northwest Atlantic Ocean, including the Bay of Fundy but excluding the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Geographic delineations are therefore a result of Atlantic oceanic boundaries, rather than political, provincial or territorial boundaries4, as defined by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). Recognizing the original inhabitants and caretakers of Atlantic Canada, a geographic context map has been included in this report that identifies the territories of the Indigenous communities near the Atlantic coast (Figure 1). It is important to note that territory maps are best defined by Indigenous nations themselves, and these maps may change to more accurately reflect the original inhabitants and caretakers of the Atlantic seaboard.

Figure 1. Native Land Digital is an Indigenous-led not-for-profit organization that works to map Indigenous territories according to Indigenous nations themselves. An interactive map allows users to learn about traditional territories, treaties and languages; readers are encouraged to visit native-land.ca for this experience. This screenshot shows the territories on the Atlantic seaboard, with an inset map for global context. CIOOS Atlantic is concerned with the marine areas in this image, excluding the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and with some overlap expected with the future CIOOS Arctic. Screenshot from https://native-land.ca/ on August 10, 2020.

CIOOS Atlantic is in the very early stages of engaging with data providers and users in the region and is envisioned as a central federated data repository for varied and independent data providers. As a prototype regional association, its role is to make data more widely available for public benefit, and engagement with data users and data providers. Recognizing the importance and value of TEK, CIOOS Atlantic is working to build meaningful, reciprocal relationships with Indigenous communities in Atlantic Canada, and to ensure these communities are included in the “public benefit” described above.

The Canadian Integrated Ocean Observing System (CIOOS) is designed to increase discovery, access and reuse of oceanographic data for various users across the nation (Stewart et al., 2019). This involves ensuring that data integrated within the system is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR) (Wilkinson et al., 2016). These principles serve to actively support productive ocean science and management, while promoting collaborative opportunities among ocean sectors. CIOOS Atlantic is one of three Regional Associations (RAs) that make up the ocean observing system, along with the St. Lawrence Global Observatory and CIOOS Pacific. Key aspects of CIOOS include an online open access platform and a team of staff who are focused on building collaborative relations with different organizations, agencies and communities.

Recognizing that financial resources and institutional limitations, such as time constraints, often fail to acknowledge the nature of meaningful relationship building (Castleden et al., 2012), CIOOS Atlantic is working to build these relationships during this initial stage, before it formally exists as an independent organization (CIOOS Atlantic is currently operating as a project within the Ocean Frontier Institute, which includes Dalhousie University and Memorial University of Newfoundland among other partners).

Historical Context: Trauma in Research Relationships

A history of colonial narratives and Eurocentric research methods is the context from which we work to build respectful, meaningful relationships with Indigenous communities. The most successful relationships between western scientific institutions and Traditional Knowledge holders recognize the historical and cultural context that precede their relationships. Indigenous knowledge and property have been misused, decontextualized and even stolen by researchers. In less intense but still troubling cases, researchers act purely as outsiders, show up to collect information, and leave without providing any clear benefit to the communities of the geographic area being studied (Fidel et al., 2014).

Cochran et al. (2008) describe how “research has been a source of distress for [I]ndigenous people because of inappropriate methods and practices” (p.22), naming an example where blood samples were misused and distributed without consent from the donor communities. Any reluctance to work with researchers is natural, they suggest, because of trauma associated with past practices. The article concludes with recommendations for all academic researchers to undertake when working with Indigenous communities, including that honesty and transparency are key to building healthy, ethical relationships (Cochran et al., 2008).

A current example of the complexity of these relationships is Mauna Kea, a shield volcano on the Big Island of Hawaii. Leading astronomy groups led by the University of Hawaii are working to build a $2 billion USD observatory known as the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) at the peak, which already hosts 12 other telescopes. This is opposed by the Mauna Kea kia’i, a group of Native Hawaiians who regard the site as sacred, describing the cultural significance and their long-standing ties to the land (Witze, 2020). It is no surprise that an area ideally suited to observe the night sky has cultural significance; indeed, ecologically significant places are often also culturally significant spaces for many of the same reasons. The kia’i describe being portrayed as interlopers on their own land, despite having been the custodians of those lands for centuries, developing their own technologies and knowledge systems for understanding space. The conflict, rooted in historic injustice, has forced a reckoning with the approach to astronomical observation on this site, though the long-term impact remains unknown (Witze, 2020).

Scientists have also been known to adopt research approaches that result in unintended harm. Simonds and Christopher (2013) note that the analytical aspect of western scientific research methods can be dehumanizing to Indigenous ways, and can appear to be an attack on their knowledge, traditions and stories. In some cases, researchers have collected stories from Elders for the purpose of critical analysis that includes assessing their alignment with the researchers’ understanding of the world. Scientists who seek to decolonize research must be inclusive, reciprocal and constantly reflective of their actions (Simonds and Christopher, 2013). This may include adopting new methods that are not as familiar to the researcher (Cochran et al., 2008) but which demonstrate respect for TEK.

One way to avoid harmful research approaches is to review protocols and ethical guidelines that have been put in place by Indigenous communities. For example, The Mi’kmaw Ethics Watch, a committee appointed by the Unama’ki College of Cape Breton University, has a set of research principles to guide studies in a way that will guarantee the right of ownership rests with Mi’kmaw communities. At the same time, the principles and protocols ensure that Mi’kmaq are treated fairly and ethically in their participatory research. Researchers are asked to describe accommodations for Mi’kmaw language, culture and community protocols, including how Mi’kmaw people will be accommodated in communicating or deriving consent (Mi’kmaw Ethics Watch, 2000).

While the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement on Research Ethics provides guidance on engaging in research with Indigenous communities, many institutions are going further in providing guidance to researchers. Recommendations and guidelines typically include early engagement, consensual relationships, ethical conduct, reciprocity and research result distribution (Memorial University, 2020). Ocean research institutes can get even more specific and directive. For example, the Ocean Frontier Institute’s Indigenous Engagement Strategy was created by the Indigenous Engagement Steering Committee, which includes the institute’s senior leadership and four Indigenous members with an expertise in Indigenous research and engagement in their regional context (Ocean Frontier Institute, Dillon Consulting, 2021).

This historical context has motivated Indigenous communities to expect better, and researchers to be better. The Assembly of First Nations (AFN), “an advocacy organization representing First Nation citizens in Canada,” has created a resource booklet on First Nations Ethics (Assembly of First Nations [AFN], n.d.). AFN provides an index of the Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge Protocols that have been developed by individual Nations and communities, which should be consulted by any researcher or group interested in engaging in TEK work within Canada (Researchers in other countries should identify any similar resources). A first step in showing respect is to review community-level variance around guidelines and values.

Ocean observing systems may collect data through owned infrastructure, but also work with organizations and partners who collect data. The mandate to offer an openly accessible ocean data platform can be alarming and problematic for Indigenous communities. TEK is at risk of being misused and misinterpreted by western scientific systems. Care must be taken to ensure that any projects involving TEK align with the needs and interests of Indigenous communities, have goals and processes that are co-developed with these communities, and clearly set out how TEK will be stored, indexed, and disseminated.

TEK Frameworks and Methods

Both TEK and western ecology are based on observations or experiments that aim to understand the natural world, but an essential difference is the normative values associated with each. Western scientific methods depend on objectivity, ensuring that researchers are not influenced by personal feelings or opinions (though this assumption is increasingly challenged, e.g. Singh et al., 2021). TEK is often guided by subjectivity and is very much dependent on experiential observations and relationships over time, with a strong element of the personal. Western ecological science often privileges quantitative work and instruments. TEK is often qualitative and represents a body of knowledge that is transmitted orally (Mazzocchi, 2006). These distinctions are not intended to be limiting or exclusionary, but rather to acknowledge two different ways of understanding the world, each with their own benefits. In general, these knowledge systems, while distinct from one another, can work together to create a more holistic approach to conducting scientific research. This concept is often called “Two-Eyed Seeing.”

First used by renowned Mi’kmaw leader Elder Albert Marshall in 2004 (Institute for Integrative Science & Health, 2004; Hatcher et al., 2009), Two-Eyed Seeing is “learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing… and learning to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all” (Ermine et al., 2004). This approach to research has resulted in many successful partnerships at the international and local levels, where individuals with expertise in one or both ways of seeing collaborate on environmental, health, education, or other work. Aikenhead and Michell (2011) describe experiences bridging cultures, connecting Indigenous ways of knowing with the required science curriculum through positive integrative projects across Africa, the United States, New Zealand, Australia, and Canada5. Key attributes of successful projects include co-ownership, shared responsibility, and shared decision-making powers. Despite the use of the word “integrative,” Two-Eyed Seeing is not meant to be one knowledge system consuming another. Rather, it encompasses a co-learning journey that can utilize multiple approaches to gain a better understanding of the world.

Two-Eyed Seeing is not a recipe or formula, as projects can vary substantially depending on the goals, participants, and regions. In this section, we describe a range of projects that use different collaborative approaches consistent with Two-Eyed Seeing, highlighting different processes used to record, display, and make Indigenous knowledge accessible. They also reveal the tension between the FAIR principles that have been part of the ethos of data repositories and the concerns of rightsholders about the risks of TEK being findable and accessible. Each example offers crucial insights into mitigation measures and enabling factors that have been developed for each project, and the results achieved. These examples are illustrative, not prescriptive; they demonstrate how projects incorporate the four Rs: respect, responsibility, reciprocity, and relevance (Kirkness and Barnhardt, 2001).

The cases are grouped into four main categories: Participatory Geographic Information Systems (PGIS), an approach to spatial planning that combines community research with digital mapping exercises; Indigenous Information Management Tools (IIMT), focusing on more general platforms that have been used to digitize TEK; Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), research conducted with and for, not on, members of a community (Strand et al., 2003); and Structured Decision Making (SDM), an organized process for engaging multiple parties in a productive decision-oriented dialog (Failing et al., 2007).

Participatory Geographic Information Systems

Participatory geographic information systems seek to engage communities in activities related to geospatial data about their own community, enabled by easy-to-use tools to sketch or annotate maps or other representations of geospatial information (Sieber, 2006). In the context of TEK, this is a mechanism for TEK holders to record geospatial data. This type of project is most common in the Arctic North, where proponents have sought to digitize TEK for future generations and current scientific communities (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous). A key driver of this interest is understanding and responding to climate change-induced environmental impacts, which disproportionately impact Arctic and coastal communities. For example, the Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory is an initiative of the Fisheries and Sealing Division of the Government of Nunavut to create a comprehensive dataset of Inuit knowledge. The Inventory provides information on aquatic and coastal species for all communities in the territory (Department of Environment Fisheries and Sealing Division, 2013).

The maturation of GIS tools (like StoryMaps and other novel technology) enables participatory GIS projects that include narrations and oral components to avoid decontextualizing Indigenous knowledge systems. TEK is preserved by knowledge holders through certain methods of teaching and learning that the western scientific realm has not typically recorded. Digital systems are designed for focusing on data of interest: observing systems providing different views or segments of data in various formats, GIS tools enable queries and layers to do the same. This same focus applied to TEK isolates it from its context, and is a form of destruction as only part of the story is being told. For TEK, the means of transmission are as important as the story itself.

To demonstrate that it is possible, we describe three successful projects that have digitized TEK while building an open platform of oceanographic and coastal data.

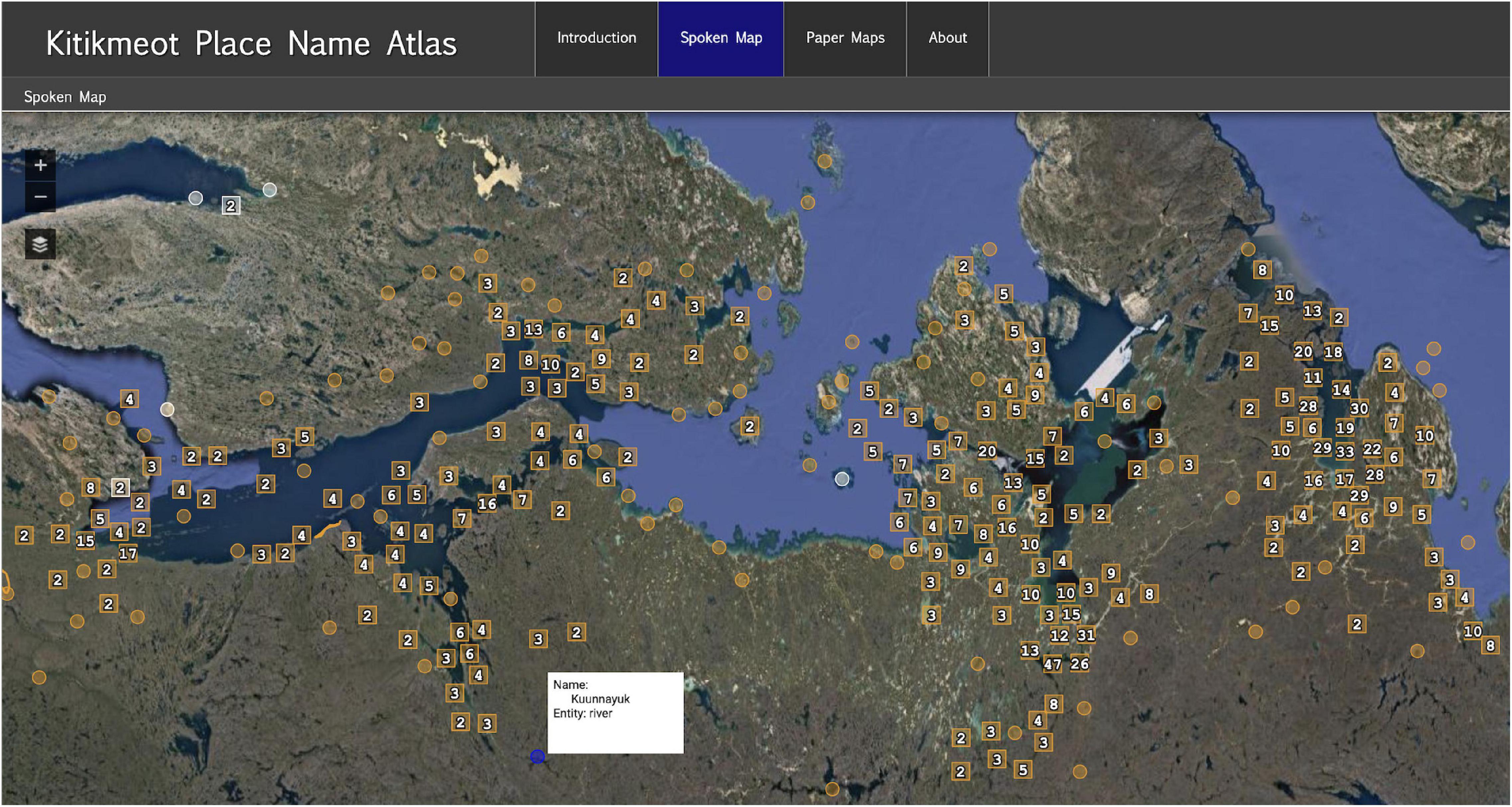

Kitikmeot Place Name Atlas

Digital cartographic atlases are one method of digitizing TEK that engages community members to share and preserve their knowledge in an online setting (Teixeira et al., 2013; Mackenzie et al., 2017). There are many different examples of online databases and atlases that use PGIS as a method for mapping TEK. The Kitikmeot Place Name Atlas (KPNA) is an interactive map that allows users to navigate through the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, Canada. The KPNA is the result of an ongoing program of place name recording in communities of the region. The purpose of the project is to preserve pronunciations, meanings and associated oral traditions of traditional Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun places. The Atlas functions by incorporating different layers of place-based data points over a base map of satellite imagery (Figure 2). Each point represents a dataset that includes a name and meaning associated with the coordinate. Many points also provide a media component that allows users to listen to the pronunciation of the traditional place names (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Kitikmeot Place Name Atlas map. The map features different clusters that incorporate several points. The orange circles are individual points that include a traditional name, coordinate, a translated name, and media associated with the datapoint (if available). Screenshot from https://atlas.kitikmeotheritage.ca/index.html?module=module.names on August 10, 2020.

The Kitikmeot Heritage Society, a community-led heritage association, partnered with the Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada to enhance technology to support new community requirements (Kitikmeot Heritage Society, 2020). Like many other digitization projects, the KPNA is focused on meeting the needs of specific identified communities.

To address concerns of decontextualization, the KPNA includes an interactive oral component to keep the original integrity and knowledge transmission alive. Much of Inuit knowledge, like other Indigenous knowledge systems, is not written down in the English language. As such, the recordings allow Elders to share their knowledge in a way that is authentic and comfortable for them. Some examples of audio features include pronunciations of traditional names, interviews and stories to accompany different datasets. The audio recording feature is effectively a layer built on top of an existing tool that improves its fitness for purpose.

While the nature of the data is different from some of the data considered by ocean observing systems, this example is still relevant as a digitized collection of Traditional Knowledge that is open and accessible to all users. The goal of sharing information regarding the traditional and ecological significance of the region was realized through a collaborative partnership between Indigenous communities and western scientific institutions. One key success factor was co-developed goals and priorities for ocean observation. The team at Carleton University prioritized the needs of Inuit (as defined by the peoples themselves) when developing the technology to support the project. Another success factor is the embrace of data not typical for observing systems, including oral histories and information that links people with place. The GIS community is ahead of ocean observing systems in this area.

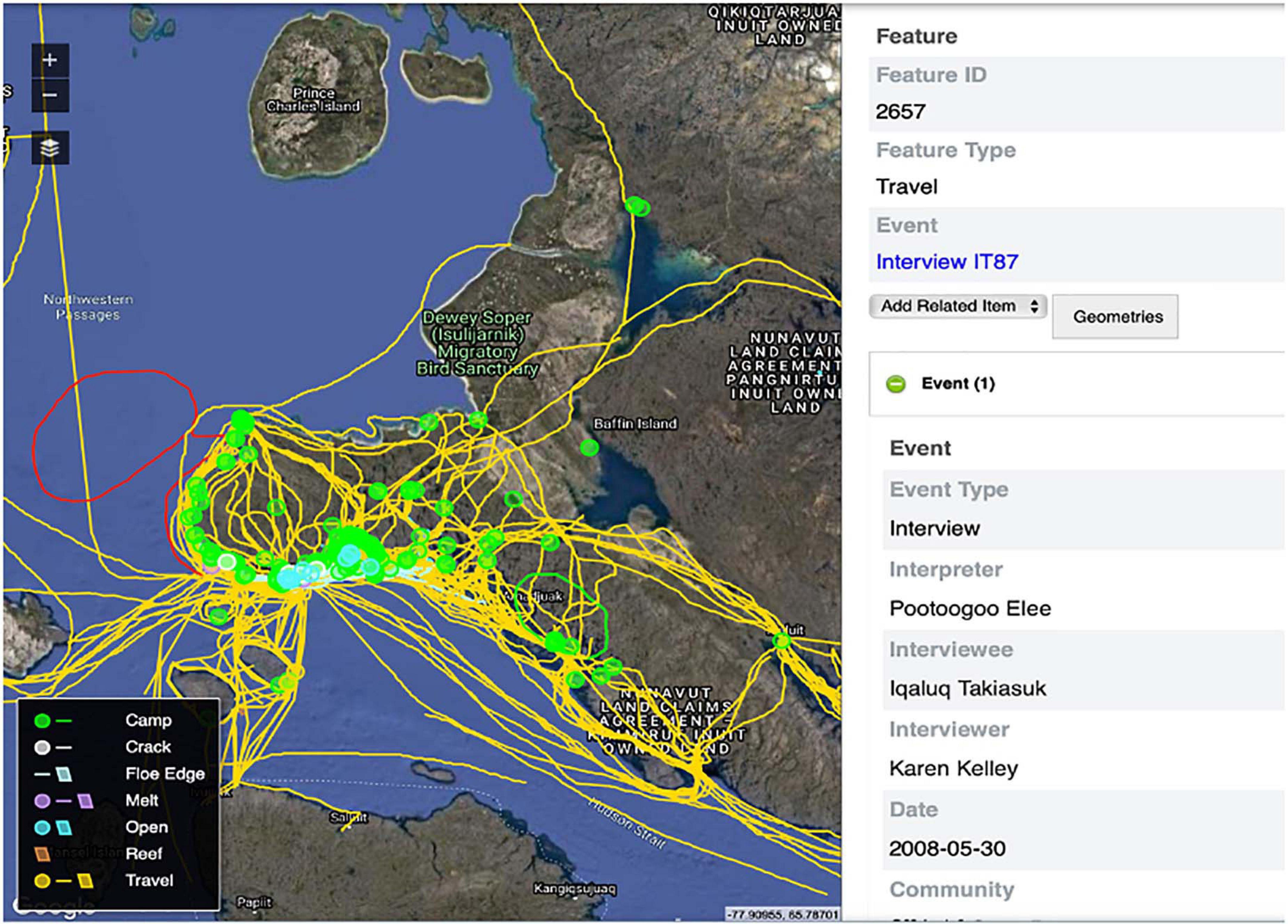

The Inuit Siku Atlas

The Inuit Siku Atlas is an example of digitized TEK that focuses on environmental observation. Sea ice is a fundamental feature of the polar environment; it is also one of the most tangible indicators of change in the Arctic. During the last two decades, and in the past several years, both polar scientists and local Inuit residents have detected important shifts in the extent, timing, dynamics and other key parameters of arctic sea ice (Siku Atlas, 2017). The Inuit Siku Atlas is an open platform that allows viewers to learn about Inuit knowledge of sea ice (“Siku”) around Baffin Island, Nunavut. The Atlas has been co-developed by Inuit experts, community researchers, and university researchers. (In this as in other examples, these labels are not meant to be exclusionary: Inuit experts can also be experts in western science, and university researchers can be Inuit).

The project aims to document Inuit knowledge about sea ice for future generations, while informing the scientific community of the climate changes observed throughout the region. Similar to the KPNA, the Siku Atlas utilizes several different map layers over a base map of satellite imagery to display different features. Some different layers of the sea ice map include travel routes, floe edges, ice ridges, cracks, camps, melts, reefs and open water areas. Each layer allows the viewer to navigate the map and click on different coordinate points or routes. Once selected, a sidebar appears that provides more information regarding the point or route (Figure 3). The Siku Atlas has four different views (Cape Dorset, Clyde River, Igloolik, and Pangnirtung) that allow users to experience unique observations made by each community, respecting the diversity of Traditional Knowledge throughout different regions.

Figure 3. The Siku Sea Ice map is interactive and allow users to click on different features to learn about how the information was collected and where it was collected from. For example, the yellow lines represent travel routes (mapped through participatory mapping sessions). Screenshot from https://sikuatlas.ca/index.html?module=module.sikuatlas.igloolik.sea_ice# on August 10, 2020.

The information recorded by the Atlas was collected through various methods, including interviews with local experts, participatory mapping, experiential travel (using the land to teach), focus groups, workshops, community-based monitoring, satellite monitoring and multi-media use. Perhaps one of the most interesting components of this Atlas is the recognition of Inuit knowledge holders as scientists. For example, weather variability, often measured in physical temperature readings, is evaluated by the decrease in ice crystal formation on people’s faces and parka hoods. Other sea ice changes that are noted by knowledge holders include changing winds, water temperatures, precipitation patterns, freezing processes, ice thickness and break up timing. In this scenario, Inuit Quajimajatuqangit (Inuit TEK) is the accumulation of methods for measuring these changes.

Every component of the Siku Atlas tells a story. The Siku Atlas provides a narrative for data that has been recorded using quantitative and qualitative approaches from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous scientists. This method provides cultural and environmental context to research. This is the principal strategy for avoiding decontextualization, ensuring that the relationship between people and the environment is recognized.

In the context of ocean observing, a key method for the Siku Alas is the use of narration to accompany instrumental readings. This approach has aided in building positive relationships while providing a comprehensive and useful system of ocean observations for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous scientists. A clear picture of oceans requires that ocean observing systems consider how to routinely supplement instrument data with this vital context and TEK.

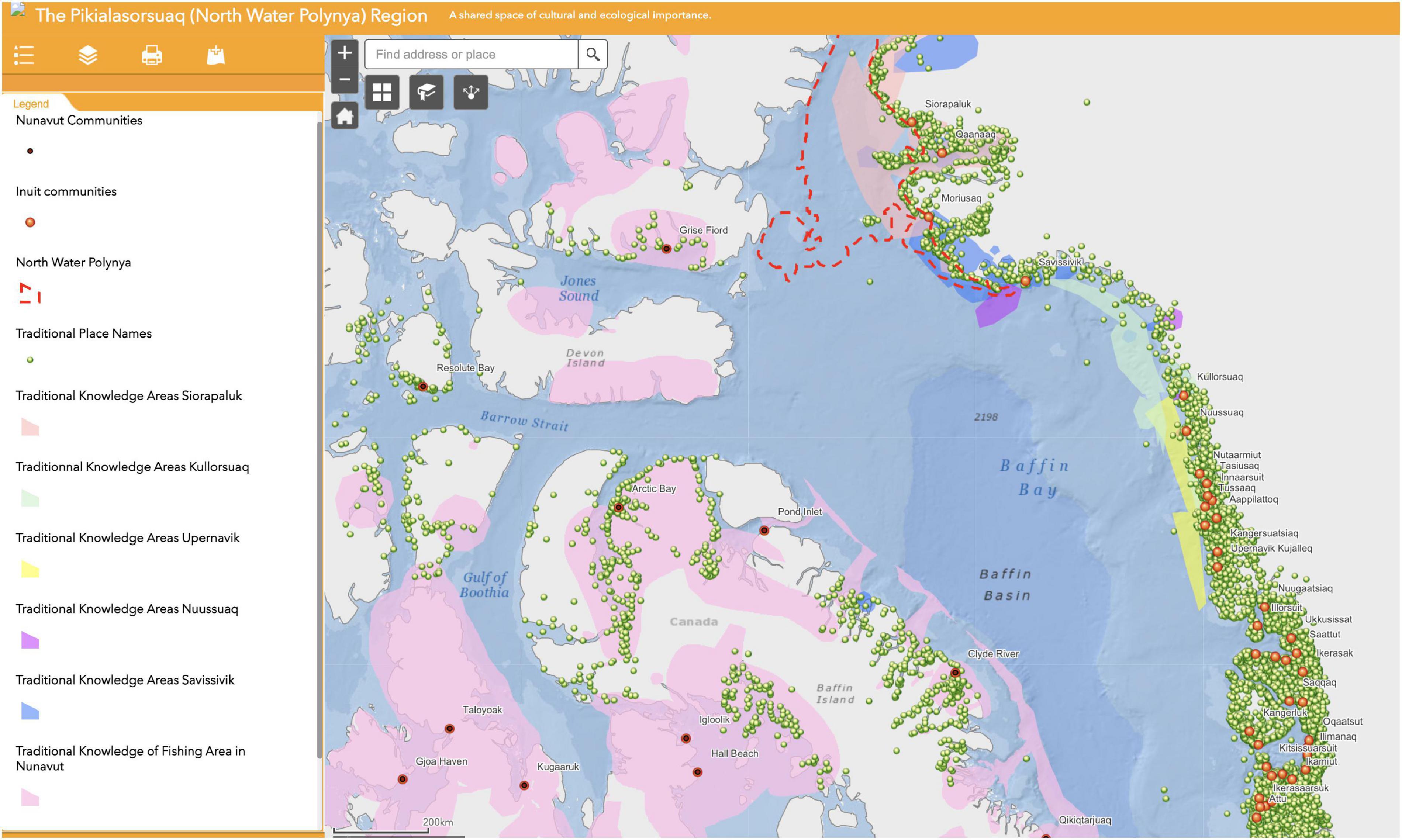

The Pikialasorsuaq Atlas

The Pikialasorsuaq Atlas (North Waters Polynya Atlas) attempts to bridge and represent both scientific knowledge and Inuit knowledge about a critically important Arctic sea-ice feature. A polynya is a large area of year-round open water, surrounded by sea-ice cover; Pikialasorsuaq is the largest polyna in the Canadian Arctic, located in the northern part of Baffin Bay between Arctic Canada and Greenland (Pikialasorsuaq Commission, 2019). As one of the most biologically active regions north of the Arctic Circle, the area sustains Inuit with food and resources, making it invaluable for physical, cultural and spiritual wellbeing (Tesar et al., 2019). It is a rich biologically diverse habitat for marine mammals, migratory birds, fish and plankton, and merits particular scrutiny in a warming climate.

The Pikialasorsuaq Atlas was first released in 2017, sparked by the growing need to safeguard and monitor the health of the polynya. The Atlas is a web-based platform that contains a variety of data points, allowing the viewer to develop a comprehensive understanding of the ecological and cultural importance of the polynya. The project is a collaboration between Dalhousie University, the Inuit Circumpolar Council’s Pikialasorsuaq Commission, KNAPK (The Association of Fishers and Hunters in Greenland) and World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

A key feature of the Atlas is an interactive story map (an ESRI GIS feature) that allows users to learn about place names, sea ice change delineations, Arctic animals, local uses and non-traditional uses. For example, by clicking on ‘local use’ at the top of the page, users can view established Inuit trails that were digitized from the Inuit Land Use and Occupancy Project (Milton Freeman Research Limited, 1976). Information to populate the Atlas has been collected through a variety of sources including Indigenous knowledge systems, western scientific knowledge systems, and previous projects. In addition to the story map feature, a ‘planning tool’ allows users to explore how different activities may interact with marine resources in the region, using the layer feature typical of GIS software. For example, one can look at overlap between undiscovered oil in the Arctic and narwhal habitat by selecting the appropriate layers on the map (see Figure 4). Users can also download or upload their own layers to the system.

Figure 4. The Pikialasorsuaq (North Water Polynya) Planning Tool allows users to upload and navigate through different layers to develop an understanding of how different activities may impact the polynya. For example, this screenshot displays overlap between narwhal habitat and undiscovered oil in the Arctic. Screenshot from https://panda.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=35081265064a460da83e89d43c041f5c on June 11, 2021.

Like the mission of ocean observing systems, the Pikialasorsuaq Atlas provides users with information that can allow them to make informed decisions regarding an ecologically significant area. Similar to the Siku Atlas and Kitikmeot Place Names Map, the Pikialasorsuaq Atlas provides a narrative to accompany geographic points and polygons, ultimately providing users with important contextual information surrounding the data they are exploring.

Researchers involved in the project note that “Inuit data, if carefully curated and presented, can be employed in the co-production of knowledge” (Tesar et al., 2019, p. 14). In a thoughtful exploration of the ethics and effectiveness of representing Inuit Knowledge in an online atlas, the authors acknowledge the challenge of decontextualizing Inuit knowledge, reducing it to a point on a map. Yet they are also optimistic, noting that despite the concerns, the “practice of using Indigenous knowledge together with scientific knowledge in a layered atlas can be used to challenge prevailing cartographic representations and empower Indigenous communities” (Tesar et al., 2019, p. 21). They provide four key elements in digitizing TEK:

[a] Involving Indigenous groups in designing usable systems.

[b] Providing context in a degree that is ‘acceptable.’

[c] Developing intellectual property policies.

[d] Providing guidelines for how to interpret Indigenous datasets.

Indigenous Information Management Tools (IIMT)

Given the unique needs of TEK and Indigenous knowledge, including considerations around intellectual property (Adams et al., 2015) and the Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP) principles, it is not surprising there are tools custom-built to meet these needs.

The Indigitization project works to provide training, toolkits, and funding to support the management of Indigenous community knowledge, and is a collaborative initiative involving Aboriginal groups in British Columbia (BC) and academic partners from the University of BC and the University of Northern BC (Indigitization, 2020).

The Reciprocal Research Network6 provides tools and support to enable remote relationship building and reciprocity, enabling “collaborative, socially responsible, and interdisciplinary research across local, national, and international borders” through a technical platform that also supports the recording and sharing of knowledge, with a focus on items of cultural significance. TEK is not part of their focus, but the model is an interesting one for ocean observing systems to consider. The Indigenous Knowledge Social Network (SIKU)7 is a social media network that establishes Indigenous rights as a first-order principle, and aims to provide a place where Indigenous knowledge can be shared for the benefit of a community without concern about ownership or abuse (Bickel and Dupont, 2018).

There is also a set of tools and consulting companies that seek to support Indigenous communities in managing consultations or other engagements that will impact their lands. For example, the CedarBox suite of apps8 is designed to support “community-based stewardship,” providing features for fieldwork and observation recording, the management of TEK interview data and archives, and other records management features. It is intentionally focused on ownership and stewardship questions, allowing organizations to host their own data locally rather than using cloud storage. The Community KnowledgeKeeper9 is a web-based system for managing a community’s documents, photographs, audio, and video files, with a particular interest in supporting consultations, land-use agreements, and environmental assessments.

Two of the PGIS case studies are built using open-source software called Nunaliit, developed by the Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre (GCRC) of Carleton University. A fundamental component of the GCRC is that technology to build and interact with information, particularly tools and information developed with public funds, should be free and open for anyone to use and modify (Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre [GCRC], 2020).

Mukurtu is one example of a tool used by Indigenous people, organizations, and communities to digitize their own data. Mukurtu (MOOK-oo-too) is a grassroots project that aims to empower communities to manage, share, and exchange their digital heritage in culturally relevant and ethically minded ways (Mukurtu, 2020). Mukurtu is committed to maintaining an open-source platform that is driven by different partnerships. The core mandate of Mukurtu is to build a simple to use, secure, and safe platform that is affordable, scalable, and updatable.

The Mukurtu database is primarily used to allow communities to share and digitize their cultural heritage by building their own website or digital archive. Core features include a ‘communities’ function that allows users to group different people and content together, a ‘cultural protocols’ function used to develop levels of access within communities, an interactive mapping component which allows users to create and visualize geospatial data, and a ‘categories’ function that can be used to describe content about the site. Media metadata allows users to share narratives, videos and audio components that may accompany different data such as maps, photographs or artifacts. Mukurtu does not digitize TEK, and is not specific to TEK, but rather provides a tool in the form of a web-publishing platform. This tool allows communities to share and publish their knowledge in a customizable way that suits their own guidelines and preferences. The cultural protocols function allows communities to ‘lock’ their knowledge or apply a ‘request access function,’ which can address concerns around knowledge governance.

Most users of Mukurtu have created platforms for museum databases and related projects, with no uses we could find focused on ocean observation. However, their focus on being an Indigenous archive and content management tool means it should be carefully considered by ocean observing systems for adoption, or for incorporation of key features.

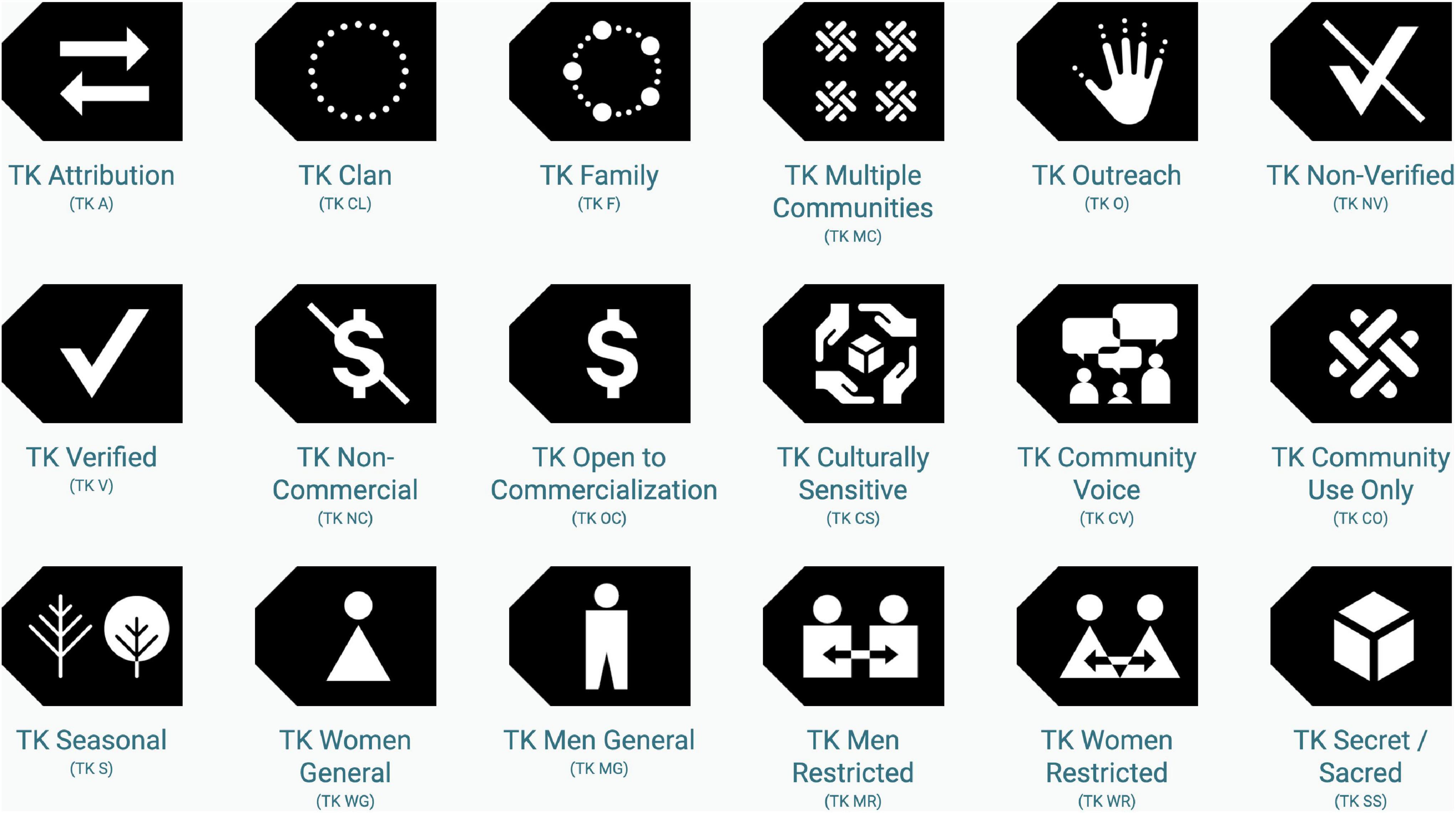

One such key feature is annotating data to identify Traditional Knowledge. Local Contexts, a labeling system for Indigenous knowledge, is an elaboration of the features originally offered by Mukurtu to separate copyright considerations from Traditional Knowledge considerations. It works to protect Indigenous intellectual ownership by providing Traditional Knowledge (TK) and Biocultural (BC) labels. These labels can be used by organizations, institutions and communities to safeguard and contextualize digitized collections of TK, including within the Mukurtu platform (see Figure 5). TK and BC labels should be considered for adoption by ocean observing systems (Liggins et al., 2021).

Figure 5. The TK Labels are a tool for Indigenous communities to add existing local protocols for access and use to recorded cultural heritage that is digitally circulating outside community contexts. The TK Labels offer an educative and informational strategy to help non-community users of this cultural heritage understand its importance and significance to the communities from where it derives and continues to have meaning. Screenshot from localcontexts.org on June 11, 2021.

Community-Based Participatory Research

Recognizing the challenges with digitizing TEK, we turn to another approach for collaborating with Indigenous communities on ocean observing in a meaningful and reciprocal way: community-based research. The TEK digitization projects described focused on recording and organizing TEK geospatially in response to the needs and interests of the community. This is representative of a broader concept, recognizing that often “community members want to know what scientists want to know” (Romer, personal communication, July 09, 2020).

Understanding the needs of Indigenous communities includes having an open mind; acknowledging that scientific and Indigenous communities may be the same or have similar objectives. For example, Ocean Networks Canada (ONC), based out of the University of Victoria in Canada, has partnered with community observatories to collect scientific data. Many of the observatories are owned and operated by First Nations communities in partnership with universities. These observatories are responsible for conducting and collecting instrumental data on the Pacific coast. There are many benefits to Indigenous peoples hosting their own observatories. For example, they allow communities to maintain ownership over their own data in their own territories. At the same time, it develops participation in and understanding of oceanographic science in a way that is beneficial to community members (as ocean caretakers). Observatories also provide employment and educational opportunities, supporting local development.

A similar community-based research approach has been applied on the east coast with the Apoqnmatulti’k (We Help Each Other) project in Nova Scotia, Canada. The Apoqnmatulti’k (pronounced ah-boggin-ah-mah-tul-teeg) project is a partnership between the Ocean Tracking Network (OTN), Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources (UINR), and the Mi’kmaw Conservation Group (MCG) to study culturally and commercially important fish species of Nova Scotia. The 3-year collaborative study tracks valued aquatic species in the Bay of Fundy and Bras d’Or Lake, while incorporating the knowledge of those who live there (Apoqnmatulti’k, 2020). One of the key approaches to this research is using Two-Eyed Seeing to develop a better understanding of the marine environment. Similar to ONC’s community observatories, the Apoqnmatulti’k partnership does not prioritize digitizing TEK. Instead, principles and ethical protocols of TEK are used to approach data collection, and TEK may inform how and where data is collected.

Projects such as Apoqnmatulti’k and ONC’s community observatories are referred to as community-based participatory research (CBPR). CBPR is a process in which decision-making power and ownership is shared between the researcher and community involved (Holkup et al., 2004). In these particular cases, community members are the researchers that are in the field, collecting data. Community observatories and the Apoqnamatulti’k project operate by having researchers and Indigenous communities work together to collect instrumental data. In many ways, TEK varies in the role it plays within scientific research. For example, collecting instrumental data in a ‘good way’, may involve following traditional values, such as having respect for samples and other ethical commitments that tie into cultural practices (Whaanga et al., 2015).

This is particularly relevant to the Apoqnamatulti’k project. MSc student and Apoqnmatulti’k team member Shannon Landovskis highlights her journey noting that “working on this project has impacted the way I conduct research by encouraging me to really question myself and the position I hold. I had to confront how I perceive the world and what has influenced my perceptions, practices, and beliefs” (Apoqnmatulti’k, 2020). Similarly, community liaison and field technician for Apoqnmatulti’k, Skyler Jeddore highlights that “Apoqnmatulti’k means working together as one from all corners, not just the scientists, but elders, local knowledge holders, and, of course, the fishermen” (Apoqnmatulti’k, 2020). In this case, the sharing of Mi’kmaw knowledge works to guide research and partnerships.

The crucial enabling factor that has made these partnerships successful is being community-led and co-developing research objectives. TEK is not collected or incorporated into any system, it is used to guide how research is conducted and how data is collected.

This factor is in turn only possible on the foundation of strong relationships. In an article titled “I spent the first year drinking tea,” Castleden et al. (2012) acknowledge some of the challenges of CBPR and relationship building. For example, finding time for relationship building poses a challenge. There are many institutional and financial limitations that make it difficult to commit to building relationships. For example, Masters and Ph.D. students often have timelines to meet in order to reach academic milestones. Similarly, organizations may not have prioritized funding to invest in relationship building. Despite these challenges, the article encourages non-Indigenous and western scientists to critically reflect on their own practices to better address unethical research, that has, for decades, “plagued Indigenous communities” (Castleden et al., 2012, p. 177). It is important to recognize that investing in these relationships, providing time, energy and resources, actively works to serve Indigenous peoples as part of the broader ocean observing community. Trust building and ‘getting to know each other’ are also valuable uses of time that should not be underestimated.

Castleden et al. (2012) recognize that partnerships with Indigenous communities are unique and not always comparable to institutional relationships that have prescribed timelines and action items. This is a challenge for ocean observing systems in particular. Considering the CIOOS Atlantic example, limits in both funding and time challenge the sincere desire for meaningful relationships and engagement. But prioritizing and making space for Indigenous peoples involves stepping outside of the funding timelines, deliverables, and initial scoping that otherwise constrain activities. Patience is essential to building meaningful relationships. Developing trust with communities prior to embarking on a data collection journey is not only respectful but encourages the longevity of a relationship (Kirkness and Barnhardt, 2001).

Adams et al. (2015) similarly suggests that researchers carefully consider their research process and who is involved, noting that “academics can be part of communities, just as community members can be researchers” (Adams et al., 2015, p. 2). Similar to Castleden et al. (2012), the authors emphasize the importance of including Indigenous communities in the research framework, and respecting ownership of the data.

Ocean observing systems should focus on the ocean observing needs and interests of Indigenous communities, ensuring that any joint projects are informed by, and motivated by, those needs. There may be established guidelines that can help; for the CIOOS Atlantic example, the Mi’kmaw Ethics Watch has laid out guidelines to ensure that intellectual property and data ownership rights are protected. These guidelines serve as a necessary foundation but are not sufficient guidance for relationship building. For example, CIOOS Atlantic engagement efforts in Mi’kma’ki will take place in the context of an ongoing dispute about self-regulated lobster fisheries involving the Sipekne’katik First Nation and DFO (Withers, 2021), a situation too complex to describe in detail here. CIOOS identifies DFO as a major funder, which could make building relationships more difficult. Protocols and guidelines are of limited use in navigating these complexities; relationships take time, sincerity, commitment, and energy.

Structured Decision Making

Another method of coordinating western science and TEK into environmental research is Structured Decision Making (SDM). SDM is an organized process for engaging multiple parties in a productive decision-oriented dialog (Failing et al., 2007). The literature and case studies integrating TEK into SDM are limited in comparison to PGIS and CBPR approaches. In most scholarly and academic articles, SDM is referred to as a model or approach for analyzing natural resource management decisions.

Lee Failing, scholar in public decision-making literature, explores how a structured decision process can contribute to the integration of TEK and western science in resource management. Failing et al. (2007) notes that often TEK, which is referred to as local knowledge, is “scientific inputs to the environmental decision-making process are often uncritically accepted” (p. 48). On the same token “scientific inputs to the environmental decision-making process are often uncritically accepted” (p. 48). This is a crucial observation that reaffirms the importance of Two-Eyed Seeing, recognizing that knowledge systems should work alongside one another. It can be harmful and counterproductive to prioritize and claim that one knowledge system is more effective or valued than another. Failing advocates for the rigorous treatment of both science (western) and values (TEK) in resource management decisions. Examples are presented in BC, Canada where participants utilize SDM to facilitate mutual learning10.

Turner et al. (2008) explore the need for a broader and more inclusive approach to land use and resource decision-making. They acknowledge that many ‘invisible’ losses that First Nations communities have experienced are due to the undervalued nature of Indigenous knowledge in resource planning. Recognizing culturally derived values as relevant can work to create better alternatives for land use planning that acknowledge Indigenous rights. In relation to ocean observation, scientific activities such as data collection should be done ethically and with the input of local Indigenous communities. Ocean observatories should ensure the data deposited have been collected ethically, with the consent of rightsholders.

In relation to decision making processes, many Indigenous communities have developed their own processes for making decisions. Indigenous governance systems or traditional government differs based on the community. For example, Kahente Horn-Miller explains that the Kahnawake’s decision making process is participatory based and requires input from multiple community members (Miller, 2013). Other governance systems have hereditary chiefs who inherit the responsibilities according to the history and cultural values of their community. The Indian Act of 1876 enforced a governance structure on First Nations in Canada known as the Elected Chief and Band Council System, which still operates today (Indigenous Corporate Training Inc [ICTINC], 2015). These governance systems are important to understand in any engagement effort.

Discussion: Best Practices for Considering TEK

A common theme in the cases described is avoiding decontextualization when recording, archiving and digitizing Indigenous knowledge. Simpson (2014) expresses concern that presenting traditional teachings through an online venue fails to recognize the physical and spiritual connection to land, and advocates teaching and preserving TEK using traditional Nishnaabeg knowledge and storytelling to advocate for reclamation of land. “If we do not create a generation of people attached to the land and committed to living out our culturally inherent ways of coming to know, we risk losing what it means to be Nishnaabeg within our own systems” (Simpson, 2014, p. 13). In an earlier article, Simpson (2004) urges readers to be anti-colonial, noting that there is a colonial narrative to digitizing and documenting TEK. Language like ‘integrating,’ ‘incorporating’ and ‘collecting’ is (we hope unintentionally) colonial, assuming that western scientists have the right to take a body of knowledge and mold it into a system that was developed without the input of Indigenous peoples (Simpson, 2004). This not only repeats historical traumas of the past but perpetuates an idea that Indigenous knowledge is a component of science to fill in western scientific gaps. Simpson emphasizes that Indigenous knowledge became threatened at precisely the same time that Indigenous nations lost control over their land (2004), and suggests academics should actively work to protect the land and waters.

Understanding and respecting individual community views on digitizing TEK is important because the concerns are literally existential. The Arctic communities in the PGIS examples embraced the digitization of TEK, using new technology to ensure that their knowledge does not become decontextualized: audio components, participatory mapping exercises with Elders, and story maps. These methods are useful to understand but will not work in all contexts. Other Indigenous communities have different methods and ways to preserve their knowledge systems: rather than direct digitization, using TEK to guide decisions around instrumented observations that augment TEK. Successful partnerships described earlier in this paper emphasize that community needs should guide research objectives. Finally, some TEK is best preserved by protecting the lands and waters that keeps its transmission alive, rather than pursuing digitization. Simpson (2004) acknowledges “situations where documenting Indigenous knowledge may be helpful in preservation,” but challenges “academics and knowledge holders to think critically about the process of documentation before they begin” (p. 384).

The practices for digitizing TEK described in the preceding sections ensure participation and avoid decontextualization. Digital cartography provides many opportunities for recording Indigenous knowledge, and is being used in collaboration with Indigenous organizations to record unprecedented social and environmental changes. Yet adopting these practices will not magically resolve ethical concerns around digitizing TEK and making it openly available. TEK that is readily findable and accessible can result in misuse and misinterpretation, harming both communities and the natural environment they depend on. Mapping rare habitats or resources that are ecologically and culturally significant may lead to economic exploitation or create new pressures on Indigenous communities. Providing context still places some trust in users to view and understand information and knowledge in that context, and to use the information for the intended purpose.

In cases where there are digital records, there are questions regarding ownerships and intellectual property (Engler et al., 2013). These questions have been raised in international, national, and local declarations that address the importance of ownership rights for Indigenous peoples. For example, the First Nations principles of OCAP (Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession) acknowledge the right of First Nations communities to own, control, access and possess information about their people (Assembly of First Nations [AFN], 2007). This includes all aspects of research and information management processes that impact them. OCAP strives to ensure that information is accessible. First Nations must have access to information and data about themselves and their communities, regardless of where it is currently held. Data about the natural environment should be no exception as it provides First Nations with information regarding the state of their traditional lands and waters. Ocean observing systems can actively support the accessibility of oceanographic observation data, which can be beneficial to Indigenous communities.

Similarly, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (United Nations General Assembly Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [UNDRIP], 2007) specifically addresses Indigenous rights to knowledge and place. For example, Article 13.1 asserts that “Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions.” The Aha Honua Coastal Indigenous Peoples’ Declaration recognizes Indigenous peoples as “first stewards” with “a responsibility to our oceans and shoreline ecosystems,” and calls on the “ocean observing community to formally recognize Traditional Knowledge of Indigenous peoples worldwide,” to establish relationships, and to “respect each other’s ways of knowing” (Indigenous Delegates at OceanObs’19, 2019). The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) Statement on Indigenous Traditional Knowledge notes that communities need “to protect [I]ndigenous [T]raditional [K]nowledge and local knowledge for the benefit of [I]ndigenous peoples as well as for the benefit of the rest of the world”, furthering that “it is vulnerable both because it is exploitable and has been exploited” (International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions [IFLA], 2019).

These statements consistently set out aligned principles for ownership and control of TEK, recognizing them as necessary for all data repositories. Entering relationships and investing time and resources into supporting TEK is considered part of formally recognizing the knowledge of Indigenous peoples.

Implied across these case studies is a complex, multi-dimension spectrum: at one end, there is a process through which TEK can and should be digitized and shared through open online platforms; on the other end, the potential benefits to rightsholders do not outweigh the risks and concerns and TEK should be left alone. At all levels, there are strategies for ensuring TEK informs instrumented observations and decision-making without direct inclusion in a repository.

TEK and the FAIR and CARE Principles

The FAIR principles are considered by many data repositories to be a best practice, to the point that there are external certification bodies that test compliance with these principles (among others). Ocean observing systems strive to provide users with data that is readily findable (discoverable), accessible (downloadable), interoperable (standardized and compatible with other systems regionally and internationally), and reusable (accurate provenance within metadata). The vocabularies, standards, and software required to collaborate internationally are already established, and ocean observing systems often adopt tools used by other systems. [In our motivating example, CIOOS Atlantic and the other CIOOS regional associations have adopted some of the tools used by their United States counterpart, and others used by government open data portals (Smit et al., 2017)]. The fact that tools specific to TEK have been developed (see Section “Indigenous Information Management Tools”) suggests that tools designed for FAIR might not meet TEK needs out-of-the-box. Ocean observing systems should audit their software stack with a TEK lens, particularly data ownership.

While sharing data tends to increase its value, some data is sensitive and cannot be made fully accessible to all. The nature of digitizing TEK makes interoperability challenging, and the importance of data ownership and stewardship challenges re-usability. Ocean observing systems will need to balance their FAIR doctrine with their sincere desire to support Indigenous communities and determine how to work with sensitive data in appropriate and ethical ways.

The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance have been developed out of the growing concern regarding Indigenous data sovereignty intersecting with the FAIR principles (Carroll et al., 2020, 2021). The authors recognize the insufficiency of FAIR for addressing the rights of Indigenous peoples to create value from their data and participate in the knowledge economy, and sought to build a set of principles that are “people and purpose-oriented, reflecting the crucial role of data in advancing Indigenous innovation and self-determination” (Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group [RDA IIDS IG], 2019). The CARE principles encourage data users and collectors to seek Collective benefit, recognize Authority to control, act with Responsibility, and foreground Indigenous peoples’ rights and wellbeing (Ethics). Approaches include appropriate data training (such as OCAP training), applying Traditional Knowledge labels to accompany data (such as Local Contexts), and enforcing data restrictions with appropriate information about why data is not openly accessible.

Recommended Best Practices

Throughout this review, it has been clear that there are complexities, local differences, and considerations that cannot be addressed by following a template. Ocean observing systems, and the people who comprise them, need to be sincere, thoughtful, reflective, intentional, patient, open-minded, and generous. Across the case studies identified in the review, we have synthesized practices that are core and foundational to demonstrating respect, responsibility, relevance, and reciprocity. Many of these would be of interest to all ocean observing systems, regardless of the state of current or planned engagement with Indigenous communities.

(1) Identify and understand local protocols and guidelines that have already been put in place. Read these within the context of national and international declarations, including OCAP, CARE, UNDRIP, and Aha Honua.

(2) Recognize and understand historical trauma and colonial tendencies, and adopt an anti-colonial approach to engagement. This is more than simply “do not be colonial.”

(3) Co-develop objectives and processes with Indigenous communities.

(4) Recognize and understand the risks associated with digitizing TEK. This includes paying close care and attention to intellectual property ownership, decontextualization, and unique community concerns. Mitigation measures should be put in place to avoid the exploitation of TEK.

(5) Recognize that the goal is not to digitize all TEK, but to identify TEK where digitization offers benefit to the community. This decision rests with the Indigenous community.

(6) Relationship building is essential, individually but also in the form of workshops, discussions, forums, and other community-led approaches.

(7) Only data that has been collected ethically should be included in the ocean observing system.

(8) Conduct an audit of cyberinfrastructure for its ability to support the archiving and sharing of TEK, and consider including purpose-built tools or features like Local Contexts labels.

(9) Recognize the importance of land, place, and people. Data must not be separated from its context.

(10) Look past FAIR to the CARE principles.

(11) Remain fully transparent. It is essential to understand goals, ownership, stewardship, access, and other questions around the management of data.

Conclusion

Building meaningful, respectful, and reciprocal relationships with Indigenous communities is the only path forward for ocean observing systems, and this review makes it clear that this is underway in some areas. The ocean observing community remains far from achieving the call of the Aha Honua to “formally recognize the Traditional Knowledge of Indigenous peoples,” and “to learn and respect each other’s ways of knowing.” The leading work summarized in this review provides some indication of the challenges ahead, but also confirmation that the path is navigable. This is especially true in relation to reciprocal coastal and ocean data observation needs of ocean observing systems and Indigenous communities.

This article describes some key success stories and some emerging and adopted software that supports digitized TEK, identifies some approaches to working alongside TEK, and warns that not all TEK should be digitized. From the examples and discussions in the literature, we synthesize value- and process-based recommendations, which are not prescriptive nor even directive, but rather offer a starting point to understand and mitigate the challenges. There is no 10-step plan to success, as local and community contexts vary widely. The onus is on ocean observing systems to understand needs and concerns, and ensure that the risks and challenges of including TEK (through digitization or other means) do not outweigh the benefits.

Our synthesis has been shared publicly in the context of three 2-h workshops engaging Indigenous Elders, some of the scholars and project leaders cited in this review, and representatives of the CIOOS Atlantic ocean observing system described in the example11. It was evident that the challenges described in this review are very present. Building relationships is never easy, and there are bound to be challenges, misunderstandings and frustrations along the way, but this is not to say it should not be done. Failing to engage with Indigenous communities can result in the exclusion of centuries of knowledge about the environment and ecological relationships. Failing to respectfully engage with Indigenous people is unethical and shortsighted. Failing to engage with Indigenous communities undermines their value as knowledge holders and scientists who have held innate relationships with the natural environment for time immemorial. The work is difficult, but essential for ocean observing systems to realize their benefit to society.

Author Contributions

MP conducted the review and wrote the initial report supported by LR and CM. SF, CM, and MS proposed and oversaw the research. All authors contributed to producing this review article based on the report, led by MS. All authors made substantive contributions and stand behind the quality of the work.

Funding

Research funding was provided by the Ocean Frontier Institute, through an award from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund. Funding for this Seed Fund grant was provided by Canada’s Ocean Supercluster. CIOOS is supported by funding partners Fisheries and Oceans Canada, MEOPAR, and the Hakai Institute. CIOOS Atlantic is additionally supported by Dalhousie University, the Ocean Frontier Institute, the Ocean Tracking Network, COINAtlantic, and the Marine Institute at Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to not only acknowledge, but thank the Indigenous caretakers of the Atlantic seaboard for their continued stewardship and resilience in preserving our lands and oceans. We thank Trent University for connections with knowledge keepers and Elders who provided a clearer understanding of respectful and reciprocal research protocols. We thank the individuals and organizations who contributed time and knowledge through informative conversations.

MP offers personal thanks to family, friends, and resilient Nishnaabeg matriarchs for continuing to pass down knowledge and stories despite the many challenges faced. Chi’miigwech.

Footnotes

- ^ The phrase “western science” is itself problematic but is adopted in this paper to distinguish between science rooted in TEK and other approaches to science. The intent is not to dichotomize; for example, Indigenous knowledge holders may also be experts in western scientific methods. This review also notes the challenge of western scientific institutions (broadly defined), which default to being colonial in nature. This review does not consistently describe these institutions as colonial but is informed by this understanding.

- ^ Throughout this paper, TEK refers to a body of environmental knowledge encompassed by Indigenous peoples. While the advice and examples might be applicable to other forms of traditional knowledge, our focus was entirely on TEK in the context of Indigenous peoples, and we make no broader claim. Indigenous peoples refer to the original inhabitants of a particular place. Indigenous in Canada is an umbrella term that refers to First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples; the original inhabitants of Turtle Island, each with their own distinct cultures, histories and values.

- ^ It should be noted that accurately identifying the geographic scopes of the traditional territories that CIOOS Atlantic operates in is difficult, because of the complexity surrounding geographic context. For example, prior to colonization, Indigenous peoples were able to move freely within their territory without the limitations of segregation by colonial officials. Reserve systems were not yet imposed on Indigenous peoples that limited them to a singular place within their traditional territory. With these changes in territorial freedom, relationships between Indigenous peoples and the natural environment have been altered, making it difficult to define a respectful land acknowledgment that is inclusive and authentic to Indigenous Atlantic communities.

- ^ Notable the use of “Canadian” in the name CIOOS implies a geopolitical boundary, which is common in ocean observing systems because of how funding works. Grappling with the complexity of this name in the context of reconciliation, self-government, and nation-to-nation relationships is out of scope for this review.

- ^ ‘Integrative’ in this context does not refer to one knowledge system merging into another. Instead, it refers to multiple knowledge systems working alongside one another where appropriate.

- ^ https://www.rrncommunity.org/

- ^ https://siku.org/

- ^ https://mightyoaks.com/products/stewardship/development/

- ^ https://knowledgekeeper.ca/

- ^ It is important to recognize that Indigenous peoples are rights holders and not simply stakeholders in decision-making processes, despite common themes throughout Canadian decision-making literature.

- ^ These workshops were a relationship building and knowledge translation activity, not a data collection activity, so no analysis of comments and feedback is provided in this article. The sessions were recorded, and are available on the CIOOS Atlantic Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCtDCafF8ggqQ4Noh74QTIvQ.

References

Adams, M., Carpenter, J., Housty, J. A., Neasloss, D., Paquet, P. C., Service, C. N., et al. (2015). “De-centering the university from community-based research: a framework for engagement between academic and indigenous collaborators in conservation and natural resource research,” in Toolbox on the Research Principles in an Aboriginal Context: Ethics, Respect, Equity, Reciprocity, Collaboration and Culture, eds N. Gros-Louis McHugh, K. Gentelet and S. Basile (Rouyn-Noranda, QC: Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue), 7–17.

Aikenhead, G. S., and Michell, H. (2011). Bridging Cultures: Scientific and Indigenous Ways of Knowing Nature. Don Mills ON: Pearson.

Apoqnmatulti’k (2020). Facebook. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/apoqnmatultik (accessed June 13, 2020).

Assembly of First Nations [AFN] (n.d.). First Nations Ethics First Nations Ethics Guide on Research and Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge. Available online at: https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/fn_ethics_guide_on_research_and_atk.pdf (accessed June 20, 2020).

Assembly of First Nations [AFN] (2007). OCAP. (Ownership), Control, Access and Possession: First Nations Inherent Right to Govern First Nations Data. Available online at: https://fnigc.ca/sites/default/files/OCAP%20First%20Nations%20Inherent%20Right%20to%20Govern%20First%20Nations%20Data.pdf (accessed June 20, 2020).

Barber, M., and Jackson, S. (2015). ‘Knowledge Making’: issues in modelling local and indigenous ecological knowledge. Hum. Ecol. 43, 119–130. doi: 10.1007/s10745-015-9726-4

Carroll, S. R., Garba, I., Figueroa-Rodríguez, O. L., Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materechera, S., et al. (2020). The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Data Sci. J. 19:43.

Carroll, S. R., Herczog, E., Hudson, M., Russell, K., and Stall, S. (2021). Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous data futures. Sci. Data 8:108.

Castleden, H., Morgan, V., and Lamb, C. (2012). “I spent the first year drinking tea”: exploring Canadian university researchers’ perspectives on community-based participatory research involving Indigenous peoples. Can. Geogr. 56, 160–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.2012.00432.x

Cochran, P., Marshall, C., Garcia-Downing, C., Kendall, E., Cook, D., McCubbin, L., et al. (2008). Indigenous ways of knowing: implications for participatory research and community. Am. J. Public Health 98, 22–27. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2006.093641

Department of Environment Fisheries and Sealing Division (2013). Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory. Available online at: https://www.gov.nu.ca/sites/default/files/ncri_pangnirtung_en_0.pdf (accessed June 19, 2020).

Duarte, M., Vigil-Hayes, M., Littletree, S., and Belarde-Lewis, M. (2017). “Of Course, Data Can Never Fully Represent Reality”: assessing the Relationship between “Indigenous Data” and “Indigenous Knowledge,” “Traditional Ecological Knowledge,” and “Traditional Knowledge”. Hum. Biol. 91, 163–178. doi: 10.13110/humanbiology.91.3.03

Engler, N., Scassa, T., and Taylor, D. (2013). Mapping traditional knowledge: digital cartography in the Canadian North. Cartographica 48, 189–199. doi: 10.3138/carto.48.3.1685

Ermine, W., Sinclair, R., and Jeffrey, B. (2004). The ethics of Research Involving Indigenous Peoples. Report of the Indigenous Peoples’ Health Research Centre to the Interagency Advisory Panel on Research Ethics. Available online at: https://www.schoolofpublicpolicy.sk.ca/iphrc/ (accessed June 29, 2020).

Failing, L., Gregory, R., and Harstone, M. (2007). Integrating science and local knowledge in environmental risk management: a Decision-focused approach. Ecol. Econ. 64, 47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.03.010

Fidel, M., Kliskey, A., Alessa, L., and Sutton, P. (2014). Walrus harvest locations reflect adaptation: a contribution from a community-based observation network in the Bering Sea. Polar Geogr. 37, 48–68. doi: 10.1080/1088937X.2013.879613

Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre [GCRC] (2020). Welcome to Nunaliit: Nunaliit Map Makers. Available online at: http://nunaliit.org (accessed June 13, 2020).