- 1Department of Health, Life and Environmental Sciences, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy

- 2Department of Science, Roma Tre University, Rome, Italy

- 3Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences and Technologies – DiSTeBA, University of Salento, Lecce, Italy

Mediterranean marine biodiversity is still underestimated especially for groups such as nudibranchs. The identification of nudibranchs taxa is challenging because few morphological characters are available and among them chromatic patterns often do not align with species delimitation. Molecular assessments helped unveiling cryptic diversity within nudibranchs and have been mostly based on mitochondrial markers. Fast evolving nuclear markers are much needed to complement phylogenetic and systematic assessments at the species and genus levels. Here, we assess the utility of the nuclear Internal Transcribed Spacer 2 (ITS2) to delimit species in the eolid nudibranchs using both primary and secondary structures. Comparisons between the variation observed at the ITS2 and at the two commonly used mitochondrial markers (COI and 16S) on 14 eolid taxa from 10 genera demonstrate the ability of ITS2 to detect congeneric, closely related, species. While ITS2 has been fruitfully used in several other mollusc taxa, this study represents the first application of this nuclear marker in nudibranchs.

Introduction

Mediterranean marine biodiversity is still underestimated and new cryptic species continue to be identified, described, and added to our inventory of marine fauna (Calvo et al., 2009; Uriz et al., 2017; González-Castellano et al., 2020; Furfaro et al., 2021). Our knowledge on diversity of groups such as nudibranchs is recently increasing as demonstrated by the number of studies published in the last years (Cella et al., 2016; Furfaro and Trainito, 2017; Korshunova et al., 2017, 2019; Furfaro et al., 2018; Chimienti et al., 2020; Furfaro and Mariottini, 2020). In nudibranchs, few morphological characters are available, and the same chromatic pattern is often shared between closely related species, thereby making difficult the species identification based on morphology alone (Johnson and Gosliner, 2012; Furfaro et al., 2021). These uncertainties are overcome with the application of an integrative taxonomic approach.

The mitochondrial gene cytochrome oxidase c subunit 1 (COI) is the reference marker for DNA barcoding and species delimitation in animals, due to its fast evolutionary rate that makes this marker very useful to investigate diversity at lower taxonomic levels (Bucklin et al., 2011). Almost all the published studies concerning nudibranchs include the COI marker, and most of them also combine the mitochondrial 16S rRNA, which has proved to be valuable for species delimitation (Lydeard et al., 2000; Alqudah et al., 2015). However, limitations of using only mitochondrial data in taxonomic and evolutionary studies are well known (Moritz and Cicero, 2004) and additional nuclear markers are needed to improve results or resolve species delimitation in closely related taxa. To date, the most used nuclear marker in nudibranch phylogenetics and systematics is the histone H3. However, this marker is weakly informative, given its low evolutionary rate, especially at the species or genus levels (Galia-Camps et al., 2020; Furfaro et al., 2021).

The nuclear Internal Transcribed Spacer 2 (ITS2) rRNA has proved informative at both lower and higher taxonomic levels (Koetschan et al., 2010) in many invertebrates including marine molluscs (Oliverio et al., 2002; Salvi et al., 2010, 2014; Salvi and Mariottini, 2012, 2017). The ITS2 is located inside the rRNA gene cluster, between the 5.8S and 28S rRNA genes (Tague and Gerbi, 1984). A peculiar feature of this marker is its bivalent patterns of variation: while its primary sequence has a high mutation rate, the secondary RNA structure is very conserved, probably due to its crucial role in the processing of the “pre-rRNA” (Joseph et al., 1999; Côté and Peculis, 2001). For this reason, it has been successfully applied both to barcoding analyses (Müller et al., 2007; Yao et al., 2010) and molecular phylogenies (Wade and Mordan, 2000; Oliverio et al., 2002). In molluscs, the most common secondary structure of the ITS2 rRNA has four/five helices (domains D1–5). The first two domains (D1 and D2) on the 5′ region are more conserved and shorter than the two or three domains of the 3′ region (D3 and D4/D5), which are often ramified (Joseph et al., 1999; Schultz et al., 2005). In the domains D3 and D4, it is located the so-called apical STEM, which is an extremely conserved sequence that has been described in a few molluscan taxa (Oliverio et al., 2002; Coleman, 2007; Salvi and Mariottini, 2012).

The barcoding power of the ITS2 is anticipated by the finding that there is a correlation between differences at the ITS2 sequence-structure and the biological species concept (Müller et al., 2007). In this context, a very useful character for species delimitation inferences is represented by Compensatory Base Changes (CBCs), i.e., two mutations that occur in a paired region of a primary RNA transcript so that pairing itself is maintained (e.g., G-C mutates to A-U) (Müller et al., 2007).

Despite there are now more than 390,000 sequences available (April 7, 2021) in the “ITS2 Database”1 (Koetschan et al., 2010), ITS2 studies are still limited to a few groups of molluscs. To date the ITS2 has been used only in two studies on nudibranchs and none of them have combined the analysis of the primary sequence with the secondary structure (Eriksson et al., 2006; Trickey, 2013).

The aim of this study is to assess the utility of the nuclear ITS2 to delimit species in the eolid nudibranchs (suborder Cladobranchia) using both primary and secondary structures and to identify diagnostic CBSs and semi-CBCs that can aid identification of species and genera, being useful for future studies on other nudibranchs groups.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and DNA Sequencing

Specimens of Calmidae Iredale and O’Donoghue, 1923, Coryphellidae Bergh, 1889, Facelinidae Bergh, 1889, Fionidae Gray, 1857, Flabellinidae Bergh, 1889, and Trinchesiidae F. Nordsieck, 1972 from Mediterranean and eastern Atlantic localities were collected by SCUBA diving (Supplementary Table 1). Samples were preserved in 95% EtOH, and DNA was extracted using the salting out procedure (Aljanabi and Martinez, 1997). Amplifications were performed by PCR using universal primers: LCO1490 and HCO2198 (Folmer et al., 1994) for the COI, and 16Sar-L and 16Sbr-H (Palumbi et al., 2001) for the 16S fragment. The newly designed forward primer ITS2 MAT-03 [5′-CGUCGC(A/G)GACGCCUC(U/C)GCGC-3′] and the reverse primer ITS2 MOD Rev: 5′-AGTTCTTTTCCTCCGCTTA-3′ were used for the ITS2. PCR conditions were the same as reported in Furfaro et al. (2016b). Amplicons were sequenced by Macrogen Inc. (Netherlands).

Analysis of Primary Sequences

ITS2, COI, and 16S DNA sequences were aligned together with GenBank sequences. We used the Muscle algorithm implemented in MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018) for COI dataset, while for ITS2 and 16S, sequence-structure alignments were built using combined sequence-structure models in 4Sale (Seibel et al., 2008) and further optimised considering the consensus sequence of each rRNA domain. The software “WebLogo”2 was used to generate a graphical representation of conserved domains and stems based on multiple sequence alignment (Crooks et al., 2004). Genetic distance (p-distance and Kimura 2-paramer, K2p, distance) and segregating sites were calculated using the programme Mega X for each marker (Kumar et al., 2018). Species delimitation analyses based on both genetic distances [Automatic Barcode Gap Discovery (ABGD) (Puillandre et al., 2012) and Species Identifier (Meier et al., 2006)] and on phylogenetic trees [Bayesian and maximum-likelihood analyses and Bayesian Poisson Tree Process (bPTP) (Zhang et al., 2013)] were carried out with the ITS2 dataset. Acanthodoris pilosa (Abildgaard in Müller, 1789) was used as the outgroup in BI and ML analyses. The GTR + I + G model was selected as the best substitution model by JModelTest 0.1 (Posada, 2008) according to the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). BI analyses were carried out with MrBayes 3.2.6 (Ronquist et al., 2012) running four Markov chains of five million generations each, sampled every 1000 generations. Consensus trees were calculated on trees sampled after a burnin of 25%. Maximum-likelihood analyses were performed in raxmlGUI 1.5b2 (Silvestro and Michalak, 2012), a graphical front-end for RAxML 8.2.1 (Stamatakis, 2014), with 100 independent ML searches and 1000 bootstrap replicates. Additionally, the recently developed Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning (ASAP) analysis (Puillandre et al., 2021) was performed using default parameters.

Secondary Structure Modelling and Compensatory Base Changes (CBCs) Analysis

Complete ITS2 rRNA and partial 16S rRNA (region from L7 to L13 stem-loops) secondary structures were obtained using the programme mfold (Zuker and Jacobson, 1998; Zuker, 2003). Best-supported folding models were predicted combining a thermodynamic approach (Mathews et al., 1999) with a close inspection of paired conserved regions. CBCs of rRNA sequence-structure were calculated and visualised in 4Sale (Seibel et al., 2008).

Results

ITS2, COI, and 16S Primary Sequence Comparisons in Eolid Nudibranchs

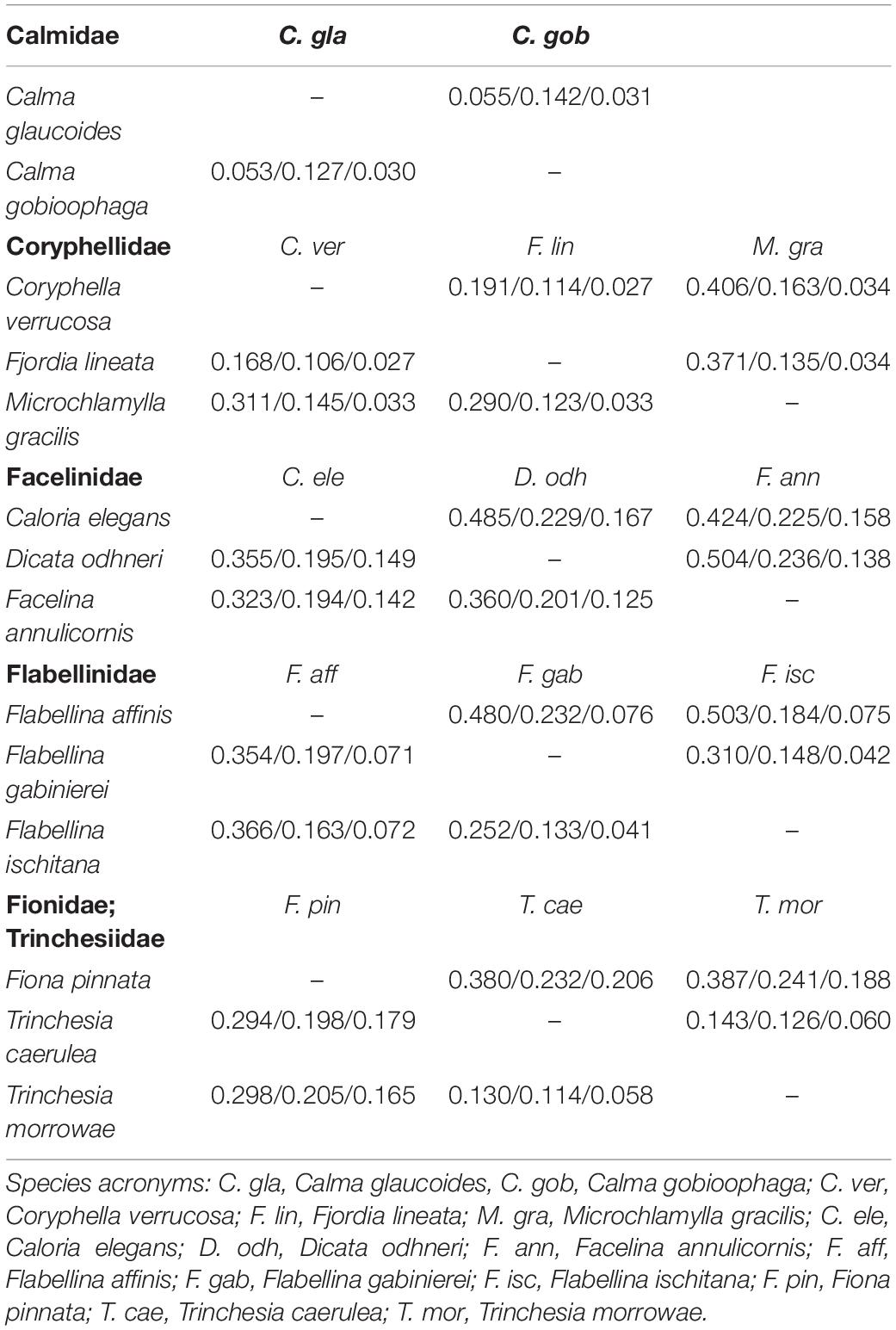

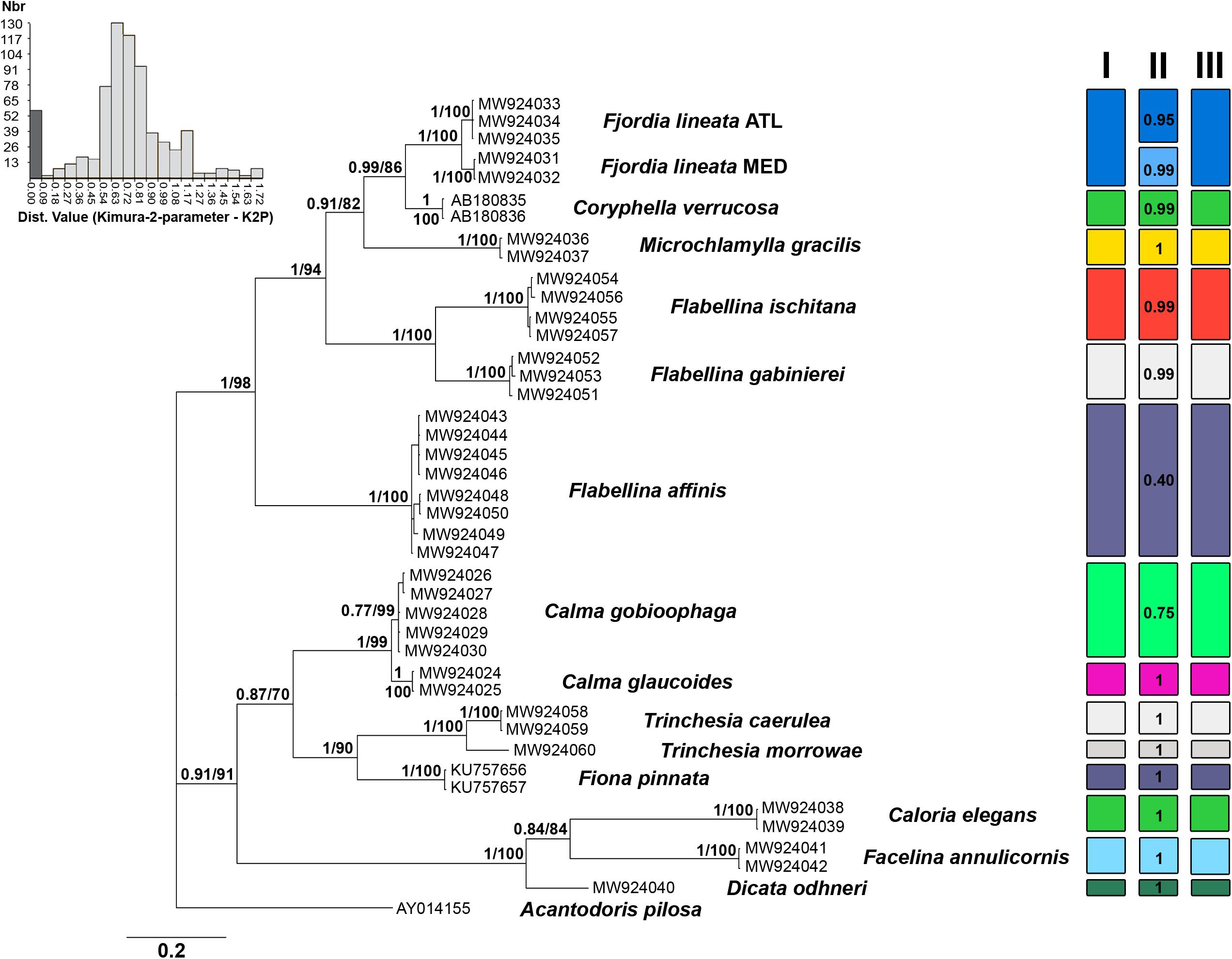

Genetic distance values for ITS2 rRNA and the mitochondrial COI and 16S rRNA markers are reported in Table 1. The lower genetic distance at ITS2 was obtained for Calma spp. with 5.3 and 5.5% p-distance and K2p, respectively, while the higher values were observed for Flabellina spp. with 36.6 and 50.3%. ITS2 is the more variable marker in most of the cases (Table 1). The lowest intrageneric p-distance and K2p values retrieved for the COI are 11.4 and 12.6% for Trinchesia spp. while the highest ones are 19.7 and 23.2% for Flabellina spp. (Table 1). Lowest values for the 16S marker were 3.0 and 3.1% between congeneric Calma spp., while the highest values were 7.1 and 7.6% for Flabellina spp. Intergeneric ITS2 p-distance and K2p values ranged from 16.8 to 19.1% between Coryphella and Fjordia species to 36 and 50.4% between Facelina and Dicata species. Genetic distance values of the two ITS2 conserved domains D1 and D2 are reported in Supplementary Table 2. Results from all the species delimitation analyses were congruent to each other (Figure 1) revealing the ability of the ITS2 to detect species even if closely related. Results from BI and ML phylogenetic inferences produced the same topology (statistical supports at each node are reported in Figure 1) and recovered two distinct monophyletic clades within Fjordia lineata (Lovén, 1846) that will need further taxonomic assessment.

Table 1. ITS2, COI, and 16S interspecific genetic distance values (p-distance: lower; K2p: upper) between representatives of six eolid families at the ITS2, COI and 16S loci (ITS2/COI/16S).

Figure 1. Bayesian phylogenetic tree based on the ITS2 dataset. Bayesian posterior probabilities and Bootstrap values based on the maximum-likelihood analysis are indicated at each node, respectively. On the top-left is the ABGD histogram showing the gap between intraspecific (dark grey) and interspecific (light grey) distances calculated with the Kimura-2-parameter model (K2P). Results of species delimitation analyses are reported in I (ASAP) II (bPTP) and III (Species Identifier).

ITS2 and 16S Secondary Structure Comparisons in Eolid Nudibranchs

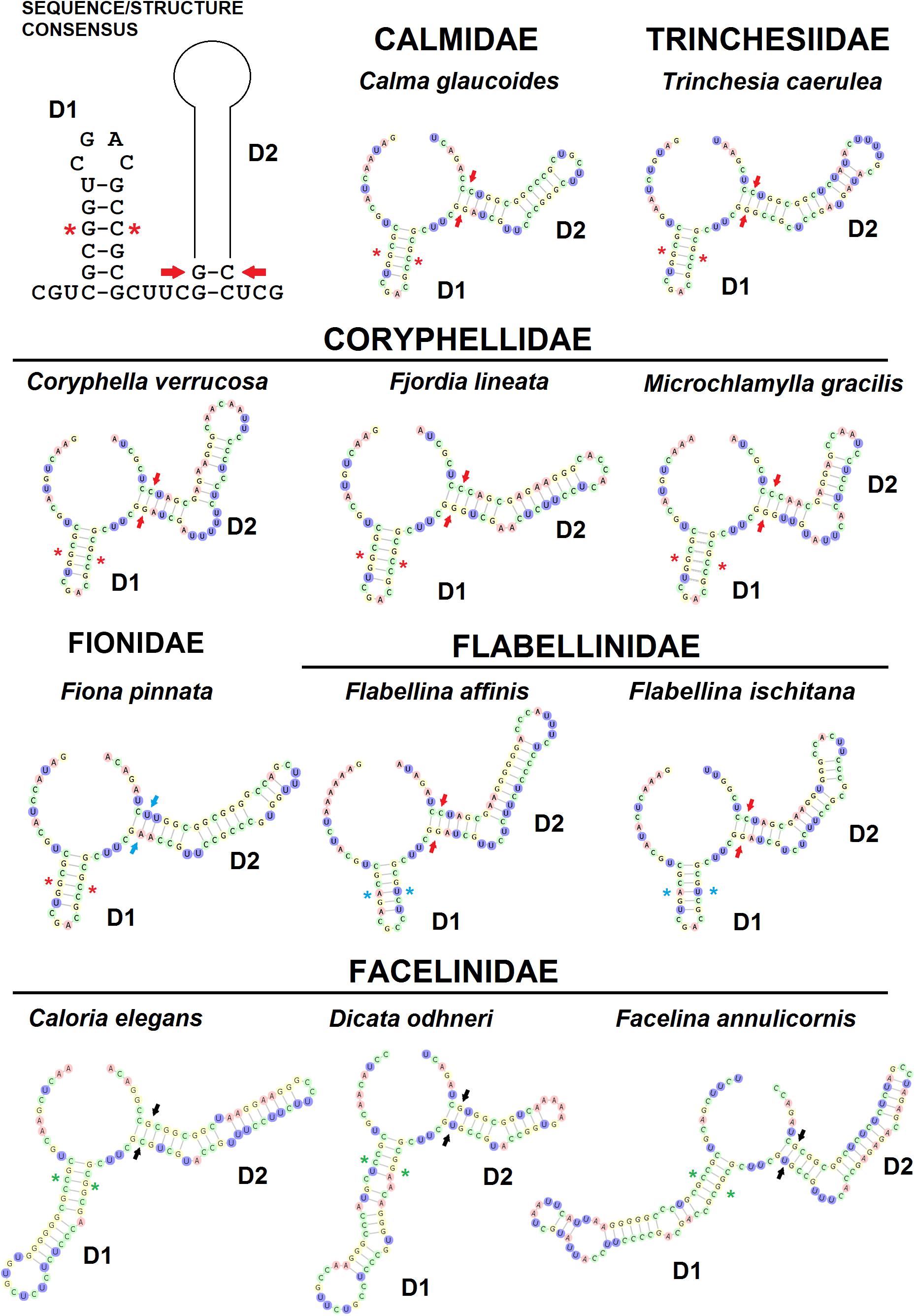

The ITS2 rRNA alignment consisted of 44 sequences, from 14 species in 10 genera and six families (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1), and 668 positions, among which 446 segregating sites. The ITS2 sequence length ranged from 275 nucleotides in Calma gobioophaga (Calado and Urgorri, 2002) to 391 nucleotides in Flabellina gabinierei (Vicente, 1975) with a mean length of 321 nucleotides. No differences in intra-specific ITS2 rRNA lengths were observed, except for the Atlantic and Mediterranean populations of F. lineata that show 311 and 313 nucleotides, respectively. The common derived ITS2 secondary structure of the eolid nudibranchs is organised in five domains (D1–5) (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 1) and conforms to the general folding observed in several other molluscan (Oliverio et al., 2002; Coleman, 2007; Salvi et al., 2010, 2014; Salvi and Mariottini, 2012, 2017).

Figure 2. Comparison of the ITS2 secondary structures of species among the families Calmidae, Trinchesiidae, and Flabellinidae.

The ITS2 D1 and D2 helix-loop regions are always identifiable in terms of sequence/structure and position (Figure 3). In fact, the basal double-strand RNA portion of D1 consisting of the very conserved triplet 5′-CGC/GCG-3′ is preceded by the triplet 5′-CGU-3′ and followed by the conserved single-strand sequence that separates D1 and D2 domains 5′-CUUC-3′. In D1 stem, another conserved base pairing is 5′-G/C-3′ positioned next to the triplet 5′-CGC/GCG-3′, present in all the families except for the Flabellinidae (substituted by the CBC 5′-A/U-3′) and the Facelinidae (substituted by the CBC C/G). The basal double-strand helix of D2 displays the consensus base pairing 5′-GG/CC-3′ (Calmidae, Coryphellidae, Flabellinidae, and Trinchesiidae), but in some families, this paired sequence is substituted by 5′-GA/UC-3′ (Fionidae) and 5′-GC/GC-3′ or 5′-GU/GC-3′ (Facelinidae) where CBCs and semi-CBCs maintain the initial stem base-pairing folding of D2. The ITS2 3′ region containing D3–D5 shows a moderate to high divergence structural folding between congeneric species (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 1) and the correct multiple sequence alignments were obtained only considering the derived 2D structures.

Figure 3. The ITS2 conserved secondary models of D1 (first domain) and D2 (second domain) of six eolid nudibranch families. Red stars indicate the conserved nucleotide pair of nucleotides (G/C) on D1. Blue stars indicate the conserved nucleotide pair of nucleotides (A/U) on D1. Green stars indicate the conserved nucleotide pair of nucleotides (C/G) on D1. Red arrows indicate the basal conserved nucleotide pair of nucleotides on D2. Blue arrows indicate CBCs of the basal nucleotide pair of nucleotides on D2 of Fionidae. Black arrows indicate CBCs of the basal nucleotide pair of nucleotides on D2 of Facelinidae.

In all species examined, there is a very high conserved sequence motif located in the apical double helix-loop region of D5 and identified as the Apical STEM, described in other marine molluscs (Salvi et al., 2010; Salvi and Mariottini, 2012). The consensus Apical STEM of the eolid nudibranchs includes up to nine base pairs: there are five invariant nucleotide positions in the 5′-strand (nnnGCUCGn) out of nine and two invariant ones (nnGnGnnnnn) out of 10 in the 3′-strand (Supplementary Figure 2). The base-pairing between the two strands does not perfectly match the entire sequences of the double helix. Within the eolid families analysed, the Apical STEM consists of nine base pairs with a single U conserved in all families (Supplementary Figure 2). Caloria elegans (Facelinidae) shows a quite different sequence due to insertions of nucleotide stretches between the stem regions (Supplementary Figure 2). The Apical STEMs of the families Coryphellidae and Flabellinidae are very similar with semi-CBCs that preserve nine base pairs (Supplementary Figure 2).

The number of ITS2 CBCs observed between species of six eolid families is reported in Supplementary Table 3. Calma spp. does not show any diagnostic CBC, whereas the number of CBCs in Flabellinidae species ranges from one (Flabellina affinis/Flabellina ischitana) to six (F. gabinierei/F. ischitana).

The 16S rRNA dataset consisted of 41 sequences, obtained from the same species (Supplementary Table 1), with 391 positions, among which 152 segregating sites. The 16S rRNA sequence length ranged from 384 to 391 nucleotides. The 16S secondary structures (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1) correspond to the domain D5 of the 3′ half portion of the gene (Horovitz and Meyer, 1995; Lydeard et al., 2000).

The sequence-structure of 16S (D5) is highly conserved between congeneric species, except for the L7, L10, and L11 stem-loops (Horovitz and Meyer, 1995), which contain diagnostic nucleotides and can be considered as barcoding regions (Furfaro et al., 2016a,b) (Supplementary Figure 1). In the D5 region, a few diagnostic nucleotides distinguish C. gobioophaga/Calma glaucoides when compared to Flabellina spp. and Trinchesia caerulea/Trinchesia morrowae.

Discussion

Our inventory of Mediterranean nudibranchs is rapidly growing as new species are continuously added, including cryptic species within historically accepted species (Furfaro and Trainito, 2017; Korshunova et al., 2019; Chimienti et al., 2020; Furfaro and Mariottini, 2020). Nowadays, the integrative approach combining morphological and molecular characters is commonly used in nudibranch taxonomy. Ideally, this approach is more robust as more genes and characters are considered. The most used markers in nudibranch systematics are the mitochondrial COI and 16S and the nuclear H3. However, the latter is known to be poorly informative at lower taxonomic levels and for this reason, an additional nuclear “fast-evolving” marker would be extremely valuable. The nuclear ITS2 assessed in this study has revealed a promising marker for nudibranch species identification. The analyses of the ITS2 primary sequence indicate that ITS2 holds a high variability that is comparable with, or higher than, the one of the COI. Species delimitation analyses based on both genetic distances (ABGD, ASAP, and Species Identifier) and on phylogenetic trees (bPTP) (Figure 1) demonstrate the ability of the ITS2 to distinguish nudibranch species. Species identified based on ITS2 are consistent with the a priori species identification (based on morphology and COI data), even for cryptic species such as Trinchesia spp. or closely related species such as Calma spp. which show the lowest divergence values (Table 1). Moreover, phylogenetic trees based on ITS2 sequence data confirm two distinct clades within F. lineata (Lovén, 1846) previously reported in Furfaro et al. (2018) based on COI data and will need further taxonomic assessment. While the combined analysis of the ITS2 sequence-structure is crucial to establish positional homology in multiple alignments, it also provides conserved sequence-structure elements, such as CBCs, that can have diagnostic value at different taxonomic levels up to the species level (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 3; see Salvi and Mariottini, 2012 for examples on bivalves). This result indicates that also in nudibranchs the presence of CBCs in the RNA folding correlates with distinct species, thus they are very useful for species delimitation, as previously observed in other eukaryotic groups (Müller et al., 2007; Wolf et al., 2013). On a less positive note, the ITS2 amplification revealed difficult for some nudibranch species (e.g., Furfaro et al., 2021). In fact, in the case of the two Mediterranean sibling species Flabellina cavolini (Vérany, 1846) and Flabellina gaditana (Cervera et al., 1987), it exhibited poor sequencing trace quality and for this reason could not be used in that study. The variability in the efficiency of sequencing the ITS2 must be considered and tested while planning the study to perform. Except for these specific cases, however, there is no doubt on the great utility of the ITS2 in the study of animal diversity (Müller et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2011). This study represents the first assessment of the ITS2 in nudibranchs and constitutes a starting point for future works focused on other nudibranch groups.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: NCBI GenBank (accession: MW924024–MW924060).

Author Contributions

MG, PM, and GF contributed to conception and design of the study. MG organised the database and performed the statistical analysis. GF wrote the first draft of the manuscript. PM and DS revised the analyses carried out. MG, PM, GF, and DS wrote the sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

GF was supported by funds from the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR, PON 2014-2020, grant AIM 1848751-2, Linea 2).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

PM and GF wish to thank “University of Roma Tre” and “University of Salento” for financial support (contribution to the laboratory CAL/2020 and AIM 1848751-2). The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for helping to improve our manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.693093/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Aljanabi, S. M., and Martinez, I. (1997). Universal and rapid salt-extraction of high-quality genomic DNA for PCR-based techniques. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4692–4693. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4692

Alqudah, A., Saad, S. B., Hadry, N. F., and Susanti, D. (2015). Identification and phylogenetic inference in different molluscs nudibranch species via mitochondrial 16S rDNA. Braz. J. Biol. Sci. 2, 295–302.

Bucklin, A., Steinke, D., and Blanco-Bercial, L. (2011). DNA barcoding of marine metazoa. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 3, 471–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-080950

Calvo, M., Templado, J., Oliverio, M., and Machordom, A. (2009). Hidden Mediterranean biodiversity: molecular evidence for a cryptic species complex within the reef building vermetid gastropod Dendropoma petraeum (Mollusca: Caenogastropoda). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 96, 898–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01167.x

Carmona, L., Gosliner, T. M., Pola, M., and Cervera, J. L. (2011). A molecular approach to the phylogenetic status of the aeolid genus Babakina Roller, 1973 (Nudibranchia). J. Molluscan Stud. 77, 417–422. doi: 10.1093/mollus/eyr029

Carmona, L., Pola, M., Gosliner, T. M., and Cervera, J. L. (2013). A tale that morphology fails to tell: a molecular phylogeny of Aeolidiidae (Aeolidida, Nudibranchia, Gastropoda). PLoS One 8:e63000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063000

Cella, K., Carmona, L., Ekimova, I., Chichvarkhin, A., Schepetov, D., and Gosliner, T. M. (2016). A radical solution: the phylogeny of the nudibranch family Fionidae. PLoS One 11:e0167800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167800

Chimienti, G., Angeletti, L., Furfaro, G., Canese, S., and Taviani, M. (2020). Habitat, morphology and trophism of Tritonia callogorgiae sp. nov., a large nudibranch inhabiting Callogorgia verticillata forests in the Mediterranean Sea. Deep Sea Res. I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 165:103364. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2020.103364

Coleman, A. W. (2007). Pan-eukaryote ITS2 homologies revealed by RNA secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 3322–3329.

Côté, C. A., and Peculis, B. A. (2001). Role of the ITS2-proximal stem and evidence for indirect recognition of processing sites in pre-rRNA processing in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 2106–2116. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.10.2106

Crooks, G. E., Hon, G., Chandonia, J. M., and Brenner, S. E. (2004). WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004

Dong, L. N., Wortley, A. H., Wang, H., Li, D. Z., and Lu, L. U. (2011). Efficiency of DNA barcodes for species delimitation: a case in Pterygiella Oliv. (Orobanchaceae). J. Syst. Evol. 49, 189–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-6831.2011.00124.x

Eriksson, R., Nygren, A., and Sundberg, P. (2006). Genetic evidence of phenotypic polymorphism in the aeolid nudibranch Flabellina verrucosa (M. Sars, 1829) (Opisthobranchia: Nudibranchia). Org. Divers. Evol. 6, 71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ode.2005.04.003

Folmer, O., Black, M., Hoeh, W., Lutz, R., and Vrijenhoek, R. (1994). DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotech. 3, 294–299.

Furfaro, G., and Mariottini, P. (2020). A new Dondice Marcus Er. 1958 (Gastropoda: Nudibranchia) from the Mediterranean Sea reveals interesting insights into the phylogenetic history of a group of Facelinidae taxa. Zootaxa 4731, 1–22. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4731.1.1

Furfaro, G., Mariottini, P., Modica, M. V., Trainito, E., Doneddu, M., and Oliverio, M. (2016a). Sympatric sibling species: the case of Caloria elegans and Facelina quatrefagesi (Gastropoda: Nudibranchia). Sci. Mar. 80, 511–520. doi: 10.3989/scimar.04479.09a

Furfaro, G., Picton, B., Martynov, A., and Mariottini, P. (2016b). Diaphorodoris alba Portmann and Sandmeier, 1960 is a valid species: molecular and morphological comparison with D. luteocincta (M. Sars, 1870) (Gastropoda: Nudibranchia). Zootaxa 4193:zootaxa.4193.2.6.

Furfaro, G., Salvi, D., Mancini, E., and Mariottini, P. (2018). A multilocus view on Mediterranean aeolid nudibranchs (Mollusca): systematics and cryptic diversity of Flabellinidae and Piseinotecidae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 118, 13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.09.001

Furfaro, G., Salvi, D., Trainito, E., Vitale, F., and Mariottini, P. (2021). When morphology does not match phylogeny: the puzzling case of two sibling nudibranchs (Gastropoda). Zool. Scr. 1–16. [Epub ahead of print].

Furfaro, G., and Trainito, E. (2017). A new species from the Mediterranean Sea and North-Eastern Atlantic Ocean: Knoutsodonta pictoni n. sp. (Gastropoda Heterobranchia Nudibranchia). Biodivers. J. 8, 725–738.

Galia-Camps, C., Carmona, L., Cabrito, A., and Ballesteros, M. (2020). Double trouble. A cryptic first record of Berghia marinae Carmona, Pola, Gosliner, & Cervera 2014 in the Mediterranean Sea. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 21, 191–200. doi: 10.12681/mms.20026

González-Castellano, I., González-López, J., González-Tizón, A. M., and Martínez-Lage, A. (2020). Genetic diversity and population structure of the rockpool shrimp Palaemon elegans based on microsatellites: evidence for a cryptic species and differentiation across the Atlantic–Mediterranean transition. Sci. Rep. 10:10784.

Horovitz, I., and Meyer, A. (1995). Systematics of New World monkey (Platyrrhini, Primates) based on 16S mitochondrial DNA sequences: a comparative analysis of different weighting methods in cladistic analysis. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 4, 448–456. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1995.1041

Johnson, R. F., and Gosliner, T. M. (2012). Traditional taxonomic groupings mask evolutionary history: a molecular phylogeny and new classification of the chromodorid nudibranchs. PLoS One 7:e33479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033479

Joseph, N., Krauskopf, E., Vera, M. I., and Michot, B. (1999). Ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) exhibits a common core of secondary structure in vertebrates and yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 4533–4540. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.23.4533

Koetschan, C., Förster, F., Keller, A., Schleicher, T., Ruderisch, B., Schwarz, R., et al. (2010). The ITS2 database III—sequences and structures for phylogeny. Nucleic Acids Res. 38(Suppl. 1) D275–D279.

Korshunova, T., Martynov, A., Bakken, T., Evertsen, J., Fletcher, K., Mudianta, I. W., et al. (2017). Polyphyly of the traditional family Flabellinidae affects a major group of Nudibranchia: aeolidacean taxonomic reassessment with descriptions of several new families, genera, and species (Mollusca, Gastropoda). ZooKeys 717, 1–139. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.717.21885

Korshunova, T., Picton, B., Furfaro, G., Mariottini, P., Pontes, M., Prkić, J., et al. (2019). Multilevel fine-scale diversity challenges the ‘cryptic species’ concept. Sci. Rep. 9:6732.

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C., and Tamura, K. (2018). MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096

Lydeard, C., Holznagel, W. E., Schnare, M. N., and Gutell, R. R. (2000). Phylogenetic analysis of molluscan mitochondrial LSU rDNA sequences and secondary structures. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 15, 83–102. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1999.0719

Mathews, D. H., Sabina, J., Zuker, M., and Turner, D. H. (1999). Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 288, 911–940. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2700

Meier, R., Kwong, S., Vaidya, G., and Ng, P. K. L. (2006). DNA barcoding and taxonomy in Diptera: a tale of high intraspecific variability and low identification success. Syst. Biol. 55, 715–728. doi: 10.1080/10635150600969864

Moritz, C., and Cicero, C. (2004). DNA barcoding: promise and pitfalls. PLoS Biol. 2:e354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020354

Müller, T., Philippi, N., Dandekar, T., Schultz, J., and Wolf, M. (2007). Distinguishing species. RNA 13, 1469–1472.

Oliverio, M., Cervelli, M., and Mariottini, P. (2002). ITS2 rRNA evolution and its congruence with the phylogeny of muricid neogastropods (Caenogastropoda, Muricoidea). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1, 63–69. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(02)00227-0

Palumbi, S., Martin, A., Romano, S., Mc Millan, W. O., Stice, L., and Grabowski, G. (2001). The Simple Fool’s Guide to PCR Version 2.0. Honolulu, HI: Department of Zoology and Kewalo Marine.

Posada, D. (2008). jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1253–1256. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn083

Prkic, J., Furfaro, G., Mariottini, P., Carmona, L., Cervera, J. L., Modica, M. V., et al. (2014). First record of Calma gobioophaga Calado and Urgorri, 2002 (Gastropoda: Nudibranchia) in the Mediterranean Sea. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 15, 423–428. doi: 10.12681/mms.709

Puillandre, N., Brouillet, S., and Achaz, G. (2021). ASAP: assemble species by automatic partitioning. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 21, 609–620. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13281

Puillandre, N., Lambert, A., Brouillet, S., and Achaz, G. (2012). ABGD, Automatic barcode gap discovery for primary species delimitation. Mol. Ecol. 21, 1864–1877. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.2011.05239.x

Ronquist, F., Teslenko, M., van der Mark, P., Ayres, D. L., Darling, A., Höhna, S., et al. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029

Salvi, D., Bellavia, G., Cervelli, M., and Mariottini, P. (2010). The analysis of rRNA sequence-structure in phylogenetics: an application to the family Pectinidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 56, 1059–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.04.025

Salvi, D., Macali, A., and Mariottini, P. (2014). Molecular phylogenetics and systematics of the bivalve family Ostreidae based on rRNA sequence-structure models and multilocus species tree. PLoS One 9:e108696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108696

Salvi, D., and Mariottini, P. (2012). Molecular phylogenetics in 2D: ITS2 rRNA evolution and sequence-structure barcode from Veneridae to Bivalvia. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 65, 792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.07.017

Salvi, D., and Mariottini, P. (2017). Molecular taxonomy in 2D: a novel ITS2 rRNA sequence-structure approach guides the description of the oysters’ subfamily Saccostreinae and the genus Magallana (Bivalvia: Ostreidae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 179, 263–276.

Schultz, J., Maisel, S., Gerlach, D., Müller, T., and Wolf, M. (2005). A common core of secondary structure of the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) throughout the eukaryota. RNA 11, 361–364. doi: 10.1261/rna.7204505

Seibel, P. N., Müller, T., Dandekar, T., and Wolf, M. (2008). Synchronous visual analysis and editing of RNA sequence and secondary structure alignments using 4SALE. BMC Res. Notes 1:91. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-1-91

Silvestro, D., and Michalak, I. (2012). raxmlGUI: a graphical front-end for RAxML. Org. Divers. Evol. 12, 335–337. doi: 10.1007/s13127-011-0056-0

Stamatakis, A. (2014). RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313.

Tague, B. W., and Gerbi, S. A. (1984). Processing of the large rRNA precursor: two proposed categories of RNA-RNA interactions in eukaryotes. J. Mol. Evol. 20, 362–367. doi: 10.1007/bf02104742

Trickey, J. (2013). Phylogeography and Molecular Systematics of the Rafting Aeolid Nudibranch Fiona pinnata (Eschscholtz, 1831). Doctoral dissertation. Dunedin: University of Otago.

Uriz, M. J., Garate, L., and Agell, G. (2017). Molecular phylogenies confirm the presence of two cryptic Hemimycale species in the Mediterranean and reveal the polyphyly of the genera Crella and Hemimycale (Demospongiae: Poecilosclerida). PeerJ 5:e2958. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2958

Wade, C. M., and Mordan, P. B. (2000). Evolution within the gastropod mollscs; using the ribosomal RNA gene-cluster as an indicator of phyolgenetic relationships. J. Molluscan Stud. 66, 565–569. doi: 10.1093/mollus/66.4.565

Wade, C. M., Mordan, P. B., and Clarke, B. (2001). A phylogeny of the land snails (Gastropoda: Pulmonata). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 268, 413–422.

Wolf, M., Chen, S., Song, J., Ankenbrand, M., and Müller, T. (2013). Compensatory base changes in ITS2 secondary structures correlate with the biological species concept despite intragenomic variability in ITS2 sequences–a proof of concept. PLoS One 8:e66726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066726

Yao, H., Song, J., Liu, C., Luo, K., Han, J., Li, Y., et al. (2010). Use of ITS2 region as the universal DNA barcode for plants and animals. PLoS One 5:e13102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013102

Zhang, J., Kapli, P., Pavlidis, P., and Stamatakis, A. (2013). A general species delimitation method with applications to phylogenetic placements. Bioinformatics 29, 2869–2876. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt499

Zuker, M. (2003). Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595

Keywords: integrative taxonomy, Heterobranchia, molecular morphology, species delimitation, secondary structure, evolution

Citation: Garzia M, Mariottini P, Salvi D and Furfaro G (2021) Variation and Diagnostic Power of the Internal Transcribed Spacer 2 in Mediterranean and Atlantic Eolid Nudibranchs (Mollusca, Gastropoda). Front. Mar. Sci. 8:693093. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.693093

Received: 09 April 2021; Accepted: 07 June 2021;

Published: 25 June 2021.

Edited by:

Tito Monteiro da Cruz Lotufo, University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Daria Sanna, University of Sassari, ItalySonia Andrade, University of São Paulo, Brazil

Copyright © 2021 Garzia, Mariottini, Salvi and Furfaro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giulia Furfaro, Z2l1bGlhLmZ1cmZhcm9AdW5pc2FsZW50by5pdA==

Matteo Garzia

Matteo Garzia Paolo Mariottini2

Paolo Mariottini2 Daniele Salvi

Daniele Salvi Giulia Furfaro

Giulia Furfaro