- 1Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES), University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, Barbados

- 2Marine Affairs Program, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

This paper explores the diversity of relationships that exist between science and policy and which underpin the uptake of science in oceans policy-making in the Wider Caribbean Region (WCR). We refer to these complex relationships, influenced by organizational culture and environments, as science-policy arenas. The paper examines the types of decisions that require science input, where the decision-making responsibility lies, who the science providers are, and how science gets translated into advice for a suite of 20 regional Intergovernmental Organizations (IGOs). The picture that emerges is one of a diverse suite of well-structured and active science-policy processes, albeit with several deficiencies. These processes appear to be somewhat separated from a broad diversity of potential science inputs. The gap appears largely due to lack of accessibility and interest in both directions (providers <-> consumers), with IGOs apparently preferring to use a relatively small subset of available expertise. At the same time, there is a small number of boundary-spanners, many of which are newly emerging, that carry out a diversity of functions in seeking to address the gap. Based on our scoping assessment, there is an urgent need for actors to understand the networks of interactions and actively develop them for science-policy interfaces to be effective and efficient. This presents a major challenge for the region where most countries are small and have little if any science capacity. Innovative mechanisms that focus more on processes for accessing science than on assembling inventories of available information are needed. A managed information hub that can be used to build teams of scientists and advisors to address policy questions may be effective for the WCR given its institutional complexity. More broadly, recognition of the potential value of boundary spanning activities in getting science into policy is needed. Capacity for these should be built and boundary spanning organizations encouraged, formalized and mainstreamed.

Introduction

This paper scopes the science-policy arenas involved in regional ocean governance in the Wider Caribbean Region (WCR). It builds on a study by McConney et al. (2016a) that explored factors affecting the uptake of science in policy making. The purpose is to illustrate, for an ocean region, the diversity and complexity of actors and processes with which any actor seeking to promote or improve the uptake of science in policy making in this region must cope. This descriptive elaboration is considered to be an essential precursor to deeper understanding of science-policy interfaces in the region and to developing approaches to improving uptake (Ostrom, 2010). There is increasing recognition of the role of regional organizations in achieving effective governance of the global oceans, and of the importance of building regional processes that have access to and make use of ‘best available scientific evidence’ (BASE) (Wright et al., 2017; IASS et al., 2020). However, other than the study by McConney et al. (2016a), we know of no other systematic attempt to elaborate a picture of science-policy arenas for ocean governance at the regional level. In our view, such studies are needed to develop a perspective of what is required to improve use of BASE at the regional level for global ocean governance.

The principle that decisions regarding conservation and management of living marine resources should be based on BASE is enshrined in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (United Nations, 1982). Countries and their regional organizations are legally obligated to operationalize this principle. Consequently, it has become well established in national, regional and global management policies and agreements. Even with the best intentions, managers have found many challenges to developing, obtaining and using BASE (Wolters et al., 2016). These range from low capacity to produce or access relevant scientific evidence, through poor communication of science to decision makers, to governance processes that are poorly or inadequately structured for the uptake of scientific advice (UNEP, 2017). The problem of linking science and policy for ocean governance has been extensively discussed in the literature for decades (e.g., Rice, 2005; Watson-Wright, 2005; Chilvers and Evans, 2009; MacDonald et al., 2016; Schumacher et al., 2020). Recently, the adoption of ecosystem based approaches to management which require a wide diversity of information for operationalization has resulted in renewed attention to this issue (Rice et al., 2014; Borja et al., 2016; Fanning et al., 2021a).

Developing countries and regions, particularly those with small islands developing states (SIDS) are particularly affected by the above challenges. The WCR is one such region in which the role of science in policy making has been noted as weak (Mahon et al., 2011; CLME+ Project, 2011; Deane and McConney, 2011; McConney et al., 2016a). Consequently, the Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem Strategic Action Programme (CLME+ SAP) includes a strategy to promote the uptake of science in management for the sustainable use of living marine resources in the region (Debels et al., 2017). The importance of this strategy has been reemphasized in the development of a regional coordination mechanism (CM) for the WCR which has strengthening science-policy interfaces as one of its functions (CLME+ Project, 2019).

The regional institutional context for governance of marine ecosystems in the WCR is complex (Chakalall et al., 1998; Fanning et al., 2009; Mahon et al., 2014; Cooke, 2017). It comprises a suite of regional and subregional intergovernmental and non-governmental arrangements1 that includes sectoral organizations (fisheries, pollution, biodiversity, etc.), multipurpose economic integration organizations and supporting organizations (academia, science and technology). The effective functioning of these arrangements is highly dependent on technical inputs from, and implementation at, the national level. Consequently, the importance of interfaces between national and regional levels has frequently been noted (McConney et al., 2016a). A multistakeholder consultation on marine ecosystem-based management (EBM) for the WCR that included representatives from academia, regional IGOs, Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and national governmental departments identified use of BASE as the second most important principle for EBM after participation (Fanning et al., 2011). Additionally, that consultation identified strengthening science-policy interfaces as critical for marine EBM in the WCR.

Clearly there is wide agreement that effective science-policy interfaces have a key role to play in promoting the use of BASE in ocean governance policy making in the WCR. However, in a region as complex as the WCR with ocean governance comprising a multi-organizational, multilevel system of arrangements (Mahon et al., 2010, 2014; Mahon and Fanning, 2019b; Degger et al., 2021), a key component to understanding the diversity of science-policy arenas, their structure and how they operate is to unpack the complexity of the system. As pointed out by Ostrom (2010) and Jordan et al. (2018), unpacking complexity is an undervalued step in the process of understanding and prescribing ways of improving a system. We believe that this unpacking is a necessary and valid step for assisting with the uptake of BASE in ocean governance decision making in the WCR and may also be instructional for other regions of the global ocean. We believe that the literature on science-policy interfaces, including boundary spanning, provides a valuable lens through which to approach this task. We first provide a brief conceptual overview of the components of a science-policy arena, the types of actors involved and their roles. Using the Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) Governance framework as a conceptual basis for multilevel ocean governance processes and interactions (Fanning et al., 2007), we then assess 20 key regional ocean governance arrangements within the WCR in terms of their type, origin and mandate. This scoping contributes to unpacking the complexity within the WCR by providing a broad perspective on where the decision-making responsibility lies, who the science providers are, and how science for ocean governance gets translated into advice in the WCR. We conclude with a reflection on brokering/boundary-spanning roles and approaches to strengthening these.

Dimensions of Science-Policy Interfaces

Conceptual Basis

This section provides a perspective that underpins the exploration of the science-policy arenas for ocean governance in the WCR. van den Hove (2007) defines science-policy interfaces as “…social processes which encompass relations between scientists and other actors in the policy process, and which allow for exchanges, co-evolution, and joint construction of knowledge with the aim of enriching decision-making.” (p. 815). Consistent with this definition is the perception of science-policy interfaces as networks of all the actors engaged in a particular science-policy arena (McConney et al., 2016a). Sarkki et al. (2020) refer to these networks as ‘meshworks’ and emphasize the need to understand and facilitate them. Hartley (2016) promotes a similar view and emphasizes the potential role of network analysis in understanding connectivity between science and policy. These studies underscore the reality that the relationship between science and policy is much more complex than just an interface between two entities. Consequently, in this paper the entire science-policy system for an issue is referred to as a science-policy arena.

It is also necessary to recognize that in governing, there are different levels of policy making - strategic policy, planning and operational - that will require science inputs (Fanning et al., 2013). The actors, the questions to be addressed and types of input will differ among these levels. In a multilevel, multi-organizational regional system, these processes may take place at different levels, namely local, national, subregional regional and global. In a regional perspective, the global level may be considered an externality, but may still be a major influencer of the structure and function of science-policy interfaces at regional and subregional levels. For example, many regional organizations are sub-bodies of global organizations, especially within the UN system (Mahon and Fanning, 2019b). At the same time, the national level may be so closely integrated into the regional level that it may even be difficult to identify policy processes that operate entirely at the regional level (McConney et al., 2016a).

In many instances policy-making pertaining to a single issue will cut across two or more levels (Fanning et al., 2013). For example in the case of managing a fishery, the overarching policies may be set at the global level by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Code of Conduct agreed upon at the FAO Commission of Fisheries (COFI). These policies are then translated to regional policies within regional economic integration organizations and regional fisheries organizations. The latter may then convert these policies into regional management plans at geographical scales appropriate to the resource distribution. Finally, in most cases the decisions for operational planning for enforcement, and data collection are taken at the national or even local level, and also require science/technical input. Fanning et al. (2013) provide more detailed examples of such multilevel policy-interfaces. Effective interoperation of these processes requires linkages among the various levels of the regional governance system and may even require a regional cooperation mechanism (Fanning et al., 2007; CLME+ Project, 2019; Mahon and Fanning, 2019a).

Roles in Science-Policy Arenas

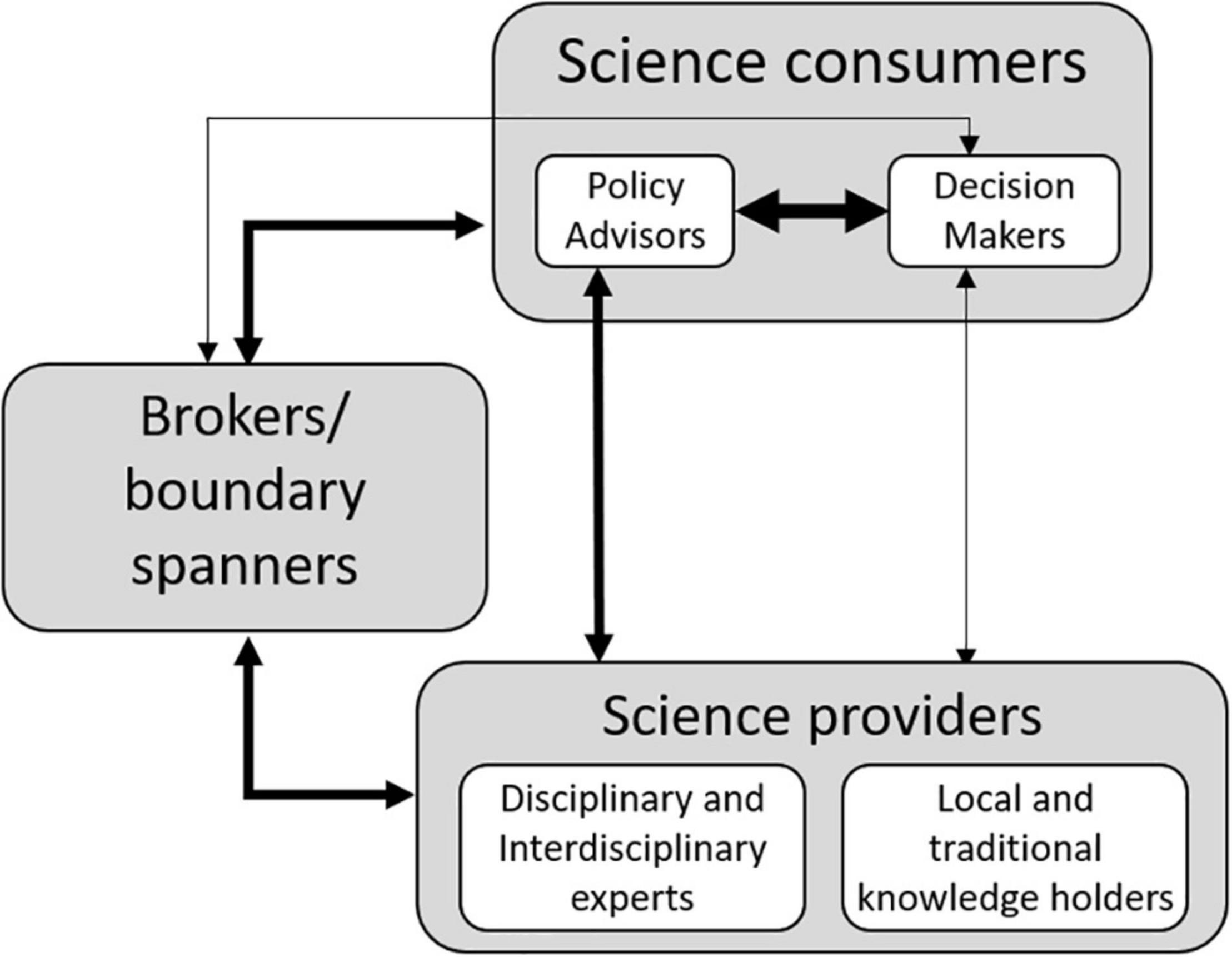

To simplify the exploration of science-policy arenas, it is convenient to consider various categories of actors and their diversity (MacDonald et al., 2016; UNEP, 2017; Gluckman, 2018). In this study, three categories of actors are proposed: science consumers, science providers, and science-policy brokers/boundary-spanners (Figure 1). However, as pointed out by Bednarek et al. (2018) within a science-policy arena for a particular issue, several individuals may play the same role, and/or some individuals may play more than one role.

Figure 1. Roles and interrelations among actors involved in science-policy arenas (arrow thickness suggests relative strengths of the relationship between actors).

Science Consumers

Consumers of coastal and marine science are of two broad types ‘advisors’ and ‘decision-makers.’ Advisors are usually the primary users with whom the research providers and brokers/boundary spanners engage. They weigh the technical advice together with other factors such as feasibility, competing interests and broader societal values to formulate the final advice. Ultimately, the decision-makers merge the advice with their own suite of factors before reaching final policy conclusions (Gudmundsson, 2003). It is important for scientists to understand that their input is usually only one of several factors influencing policy decisions, otherwise they may develop a negative view of the process and become disinclined to participate (Singh et al., 2014; MacDonald et al., 2016). On occasion, the providers and/or brokers may engage directly with decision-makers (Figure 1). It is also useful to note that regional level science advisors may formulate advice for input to decision making processes at global, regional and national levels. Serving the needs of these diverse science consumer processes at multiple levels will present advisors with challenges in formulating advice appropriately.

Science Providers

Ecosystem based management (EBM) of ocean ecosystems requires a wide range of disciplines: biogeophysical sciences (e.g., geology, biology, ecology, physics, chemistry), social sciences (e.g., political, economic, social), legal studies, management studies and technological studies, inter alia (UNEP, 2017). Science users must engage with this diversity among the research provider community (in terms of disciplines, institutions and research orientation) if they are to ensure use of BASE. Additionally interdisciplinary studies that bring the above together to address a research problem are required (Rice, 2016). The information may originate from many sources including from local stakeholders and communities (UNEP, 2012; Weichselgartner and Marandino, 2012) (Figure 1). As governance becomes more widely accepted as including all stakeholders, the need to provide for the coproduction of information by scientists, users and other interested parties is increasing and adds further complexity (Gustafsson et al., 2017; Norström et al., 2020).

Science-Policy Brokers/Boundary-Spanners

Connecting science and policy as described above is thought to require yet another kind of expertise in the form of an intermediary or broker that facilitates the exchange of information between science providers of all kinds and science consumers (Bednarek et al., 2015; Goldsmith et al., 2016). Actors in this role are often referred to as boundary-spanners (Cook et al., 2014; MacDonald et al., 2016; Bednarek et al., 2018). Bednarek et al. (2018) define the practice of boundary-spanning as “work to enable exchange between the production and use of knowledge to support evidence-informed decision-making in a specific context” and define boundary-spanners “as individuals or organizations that specifically and actively facilitate this process” (p. 1176).

There is a substantial literature on boundary spanning which has its origin in organizational and management studies (e.g., Tushman and Scanlan, 1981; Levina and Vaast, 2005). A full review of these concepts is beyond the scope of this paper. More recently, these concepts have been applied to science-policy interfaces (see review by Gluckman et al., 2021). Of particular interest for this paper is their application in science-policy interfaces for environmental governance (e.g., Guston, 2001; Smith et al., 2018; Jensen-Ryan and German, 2019) and especially for oceans (e.g., Driscoll et al., 2011; Cook et al., 2014; Goodrich et al., 2020; Posner et al., 2020). The conceptual developments pertaining to boundary spanning in science-policy arenas include activities by individuals and organizations. Note however, that most of the research has been done on national science-policy interfaces, with less attention to regional transboundary science-policy arenas (e.g., McConney et al., 2016a).

Materials and Methods

This study includes 20 major regional intergovernmental arrangements for governance of ocean ecosystems in the WCR. These arrangements were included based on previous analyses in this region (Mahon et al., 2015; Fanning et al., 2015; Cooke, 2017; Mahon and Fanning, 2019a, b). The LME Governance Framework which provides the conceptual basis for this evaluation is based on the premise that effective regional governance requires complete policy cycles, each with five stages; namely ‘data and information (DI),’ ‘provision of advice,’ ‘decision making,’ ‘implementation,’ ‘review and evaluation,’ at multiple levels (local, national, subregional, regional and global) with appropriate lateral and vertical linkages among them (Fanning et al., 2007). The first three stages above encapsulate the science-policy interface with ‘DI’ representing science providers, ‘provision of advice’ representing translation of science into policy relevant advice, including brokerage and boundary-spanning functions, and ‘decision making’ representing science users.

Following the approach of Mahon et al. (2015), this study examines the occurrence of each of the three stages in policy cycles associated with each arrangement in the WCR. Regarding the data and information stage, the main question asked is who the science providers are. Regarding the provision of advice stage, the questions pursued are: Is the science advisory function clearly specified in the agreement? If not, is it identifiable as a regular process based on documented outputs, or is it irregular, unsupported by formal documentation, or even entirely absent? Regarding the decision-making stage a key question is who decides and whether decisions are binding, passed to another arrangement as recommendations for decision-making there, or only recommendations for participating countries for voluntary implementation?

For each arrangement, the institutional mechanisms for policy making were determined from constituting documentation such as conventions and operating rules. Sources and pathways of scientific input to the identified science-policy arenas were determined by examining documentation of key meetings. In addition to the regional IGOs reviewed, the activities of NGOs that have been involved in regional science-policy interfaces are considered to evaluate the roles that they have played. In all cases, attention was paid to boundary spanning activities by actors within the science-policy arenas. In order to evaluate the extent of boundary spanning activities, a broad view of what constitutes a boundary spanning activity was taken. We found the seven possible functions suggested by Goodrich et al. (2020) provided guidance appropriate for our scoping exercise:

(1) “Connecting producers and users of knowledge by enabling and organizing their interaction, including providing logistical, mediation, facilitation, and financial support;

(2) Reconciling and protecting interests, different motivations, and cultures at the boundary and attending to issues of equity, unequal power, inclusivity, and trust building;

(3) Acting as ‘honest brokers’ by specifically focusing on integrating scientific knowledge with stakeholder input and offering (or helping influence) alternative approaches;

(4) Fostering mutual understanding among different interests while representing the interests of all (i.e., a stabilizing role at the science-policy interface);

(5) Co-producing and disseminating materials, tools, and objects (e.g., communication and visualization resources, scenarios, models, maps, apps) that can help bridge users and producers of knowledge but also customize information to different decision contexts;

(6) Providing services, training, and complementary expertise to enhance the production of actionable knowledge;

(7) Supporting and fostering the creation and maintenance of knowledge networks and communities of practice that sustain the co-production of knowledge and use.”

These functions were used to identify boundary-spanning activities by individuals within all types of organizations, and by entire organizations. Brief descriptions of these activities are provided to facilitate this evaluation and illustrate the diversity of boundary-spanning functions occurring within the WCR.

There are other actors whose activities may impact marine ecosystems in the WCR. Their science input needs are also relevant; for example tourism, oil and gas, shipping, energy, mining. Some have regional IGOs that could also play a role in regional ocean governance, such as the Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO), Caribbean Shipping Association (CSA), Port Management Association of the Caribbean (PMAC), Regional Association of Oil, Gas and Biofuels Sector Companies in Latin America and the Caribbean (ARPEL). However, these bodies are not included in the current analysis which focuses only on those bodies with a mandate for ecosystem management.

Finally, every effort has been made by the authors to objectively assess the identified science-policy arenas in the WCR through the use of the peer-reviewed frameworks and guidance. However, it must be noted that we have been engaged in regional and subregional ocean governance arrangements and activities involving all of the regional organizations included in this study for over 40 (RM) (Mahon, 2020) and 16 (LF) years and we draw extensively on our experiences. While being aware of the potential drawbacks of insider research (Teusner, 2016; Fleming, 2018), it is important to note that some of the information and insights acquired for this study are not readily available on websites or in easily accessible documents.

Results and Discussion

This section first examines the diversity of science-policy arenas at the regional and subregional levels and the types of decisions that require science input. It examines where the decision-making responsibilities lie and resulting lateral and vertical linkages among regional organizations and with the global level. Next, it examines who the science providers are. Finally, it considers the types and operations of science-policy brokers/boundary-spanners and how their role might be strengthened. The picture that emerges is one of a diverse suite of well-structured and active science-policy processes, albeit with several deficiencies. These processes appear to be somewhat separated from a broad diversity of potential science inputs. The gap appears largely due to lack of accessibility in both directions (providers <-> consumers), with IGOs apparently preferring to use a relatively small subset of available expertise. At the same time, there is a relatively small number of diverse boundary-spanning activities, many of which are newly emerging.

Science-Policy Arenas for Regional Ocean Governance

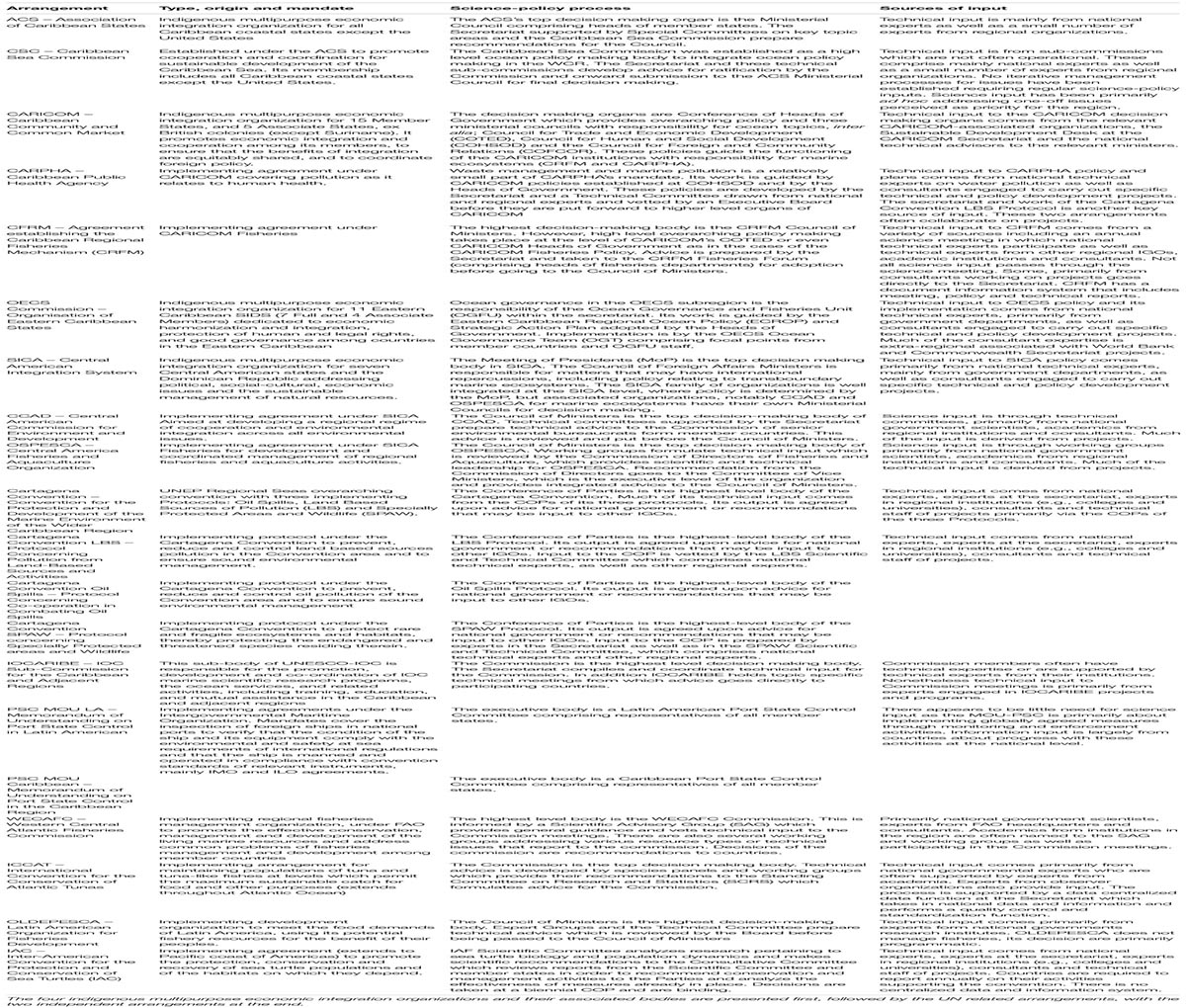

Within the WCR, the regional IGOs2 with responsibility for ocean issues are the core of the emerging Regional Ocean Governance Framework (CLME+ Project, 2013; Mahon et al., 2014). The mandates, science-policy processes and sources of science input of the key IGOs that are relevant to sustainable use of marine ecosystems in the WCR are shown in Table 1. These intergovernmental arrangements provide the majority of arenas for the uptake of science in policy making at the regional level. Some of these IGOs are indigenous multipurpose economic integration organizations with a broad mandate that includes oceans; namely the Association of Caribbean States (ACS), the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), and the Central American Integration System (SICA) (Table 1). These organizations are mostly high-level policy-setting bodies and, with the exception of the OECS, have subsidiary organizations with mandates for marine ecosystem management in areas such as fisheries, pollution and biodiversity.

Table 1. Key regional ocean governance arrangements in the Wider Caribbean Region and their science-policy processes.

These four high-level bodies tend to use science only after it has been processed by other organizations into overarching policy advice. Nonetheless, ensuring that the advice that reaches them is based on the best available science is important, as they are where science policy meets multisectoral financial policy and planning (Söderbaum and Granit, 2014). Among the four indigenous multipurpose IGOs, only two, the OECS Commission and the ACS have policies and institutions for the broader topic of ocean governance. Although SICA and CARICOM have subsidiary arrangements (Table 1) addressing aspects of ocean governance, neither has overarching oceans policy. The development of such policy and supporting arrangements that would provide an integrating science-policy arena within which science providers and brokers/boundary-spanners could engage is long overdue in both IGOs; especially as they are now pursuing blue economic growth.

In the OECS, these sectoral responsibilities are encompassed within the structure of the OECS Commission. The OECS Caribbean Regional Oceanscape Project (CROP) which underpins the development of ocean governance in the OECS subregion links national to subregional ocean policy in an integrated program that feeds advice to sectoral ministerial decision-making processes and the heads of government. Nonetheless, the OECS arena has a limited science base within its member countries and relies on inputs from projects and external scientists selected for their specific expertise. The establishment of a fifth University of the West Indies (UWI) Campus in 2019 in an OECS Member country (Antigua and Barbuda), and the Centre of Excellence for Oceanography and the Blue Economy based at this campus augurs well for the development of a stronger science base and a more integrated OECS science-policy arena.

Most other IGOs have a sectoral focus and use science directly. All have been established by signed agreements, have secretariats and hold regular intergovernmental meetings (IGMs) in which member countries take decisions (Table 1). Five are fisheries IGOs (CRFM, ICCAT, OSPESCA, OLDEPESCA, WECAFC)3 (Table 1). However, as the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries (EAF), requires attention to ecosystem health as well as the wellbeing of the social and economic systems associated with fishing, they will require the fullest range of science input for effective decision making. Seven IGOs have a mandate to address various aspects of pollution (Cartagena Convention, Oil Spills Protocol, LBS Protocol, CCAD, CARPHA, two PSC MOUs), while three have a mandate for biodiversity issues (SPAW Protocol, CCAD, IAC) (Table 1).

Most IGOs have well defined processes articulated in their constituting and operational documents, and for which there is ample evidence of operation in the form of meeting reports. These processes produce recommendations which may be taken to a political decision-making level, if there is one associated with the IGO, or for adoption at the national level (see below). Some IGOs meet biennially, for example, WECAFC, IOCARIBE, the Cartagena Convention and its protocols; but most convene at least annually. In addition, most hold technical meetings which may be of associated technical bodies, ad hoc meetings on special issues, or project related. Thus across the entire suite of arrangements, there is a large array of meetings each year that both science providers and boundary-spanners must grapple with if they are to make or facilitate effective science inputs.

Several arrangements are sub-bodies of global level UN organizations; namely UNESCO-IOC, UNEP, IMO, and FAO (Table 1). While these regional level arrangements may set some types of policy, they rely on their global bodies for overarching policy direction. Thus, this aspect of the science-policy interface must span the regional/global interface and requires regional input to adapt global policy to the regional level. Similarly, where regional IGOs are sub-bodies of indigenous regional economic integration bodies (namely ACS, CARICOM and SICA), some policy advice must transit from the sub-body to the parent body for policy decisions (Table 1). In the ACS, its Caribbean Sea Commission has its own ministerial council and could function as the high-level science-policy interface that it was originally intended to be (ACS/CERMES-UWI, 2010). However, it has not taken up this role and functions mainly as an implementing body for projects.

The majority of science input across the entire suite of arrangements is oriented toward programmatic decisions such as which projects and research initiatives to pursue and the implications of subsequent findings for regional and national policy and legislation. The other common form of advice is on overarching policy, such as the CARICOM Common Fisheries Policy4, the Castries Declaration on Illegal Unreported and Unregulated Fishing5 or the OECS St. Georges Declaration (Geoghegan, 2015). Few organizations provide advice as part of regular recurrent processes that manage ongoing issues such as fisheries stocks (e.g., ICCAT, CRFM), pollution levels, or biodiversity loss. The irregular nature of needs for science advisory inputs likely makes it difficult for science providers to engage, emphasizing the need for boundary-spanning actors.

Data and information functions in regional IGOs are generally limited; perhaps due to irregular science needs. Information on these functions is not included in Table 1 to avoid extensive repetition. ICCAT, and WECAFC are the only IGOs which maintain centralized databases on recurrent issues for which they have a mandate. For ICCAT, the secretariat vets and combines data for use by the assessment working groups. For WECAFC, the data are held at FAO headquarters, Rome, and extracted to produce reports for WECAFC meetings. All other IGOs maintain document libraries of technical and meeting reports. However, they seldom maintain databases for monitoring variables of concern. The ease of access to, and completeness of, document libraries vary widely across IGOs. Databases and documentation on issues falling under an IGO’s mandate are of critical importance for institutional memory which underpins continuity and consistency of technical input; especially when there are few technical staff in the secretariats and external experts may change over time.

The suite of IGOs and associated arrangements described above presents a complex set of science-policy arenas with which science providers seeking to influence policy must engage, either directly or through boundary-spanners, to (a) have their science outputs considered and (b) to determine what the major questions are so they can orient their research accordingly. In addition to the regular and ad hoc processes of regional IGOs, there are other emergent science-policy processes with which science providers must cope, for example, those for the international agreement on conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement), the invasive lionfish and the sargassum invasion affecting the entire region.

Actual and Potential Sources of Scientific Input

Our analysis of constituting documentation and operational rules for the 20 arrangements found science input to IGO and other science-policy processes was obtained primarily from national governmental experts, IGO Secretariat staff, and projects carried out for IGOs by consultants (which may include academic researchers) (Table 1). Academic researchers from universities and research laboratories are less frequently directly involved in providing science input (Table 1). When they are involved, IGOs appear to use a limited selection of experts as also found by Fanning and Mahon (2021). This is concerning given that the academic research community in the WCR is highly heterogeneous and there is considerable research capacity within the region across the varied types of research required. Toro (2017) reported that there are 147 academic higher education institutions (universities, polytechnics, colleges) with marine science and technology programs in the WCR. If the full range of disciplines and types of research needed are considered, this number will be considerably higher. Most of these academic institutions are concentrated in a few countries (United States, Mexico, Colombia, and Brazil) and the remainder are distributed through 14 other countries. Collectively they represent considerable research capacity. These institutions and their research capacity has not been fully inventoried which would be useful in coordinating research, especially its transfer to decision makers.

Regional IGOs also conduct research either by permanent secretariat staff, mostly facilitating the synthesis of knowledge from secondary sources, or through projects being carried out by consultants (e.g., CRFM, 2019; CCAD, 2020). These activities have generated considerable quantities of research not all of which is readily accessible or obtainable through conventional web-based search processes. Similarly, local, national and regional NGOs produce applied research which can be found mainly in the gray literature. As with tertiary educational institutions, no reliable inventory of these organizations or their research outputs exists. National agencies often have researchers as well; again mainly concentrated in the larger more developed countries. Nonetheless, the collective research capacity in national departments of the many smaller, less developed countries is likely to be considerable.

Finally, a considerable amount of research is conducted in the region by external researchers, mainly from universities. It is not uncommon for such research to be conducted unbeknownst to anyone in the WCR and published in journals and reports that are difficult to know about, let alone access. According to Stefanoudis et al. (2021) this ‘parachute science’ is a common problem worldwide. They call on researchers and publishers to adopt practices to minimize this problem, especially by including local researchers and observing national research policies requiring that data and reports be provided to relevant agencies in the country. However, smaller countries may not have the capacity to monitor and enforce these policies or to manage these data and reports when they are provided. Hence the need for such capacity at the subregional and regional levels. At the subregional level, the OECS Commission has a ‘Code of Conduct for Responsible Marine Research’ that promotes sharing and dissemination of research by all researchers (OECS Commission, 2016). However, what is also lacking is a regional level registry of researchers who fail to adhere to information sharing principles and practices.

It is evident that there is considerable research capacity in the WCR, but that its wide institutional and geographic distribution makes it difficult to access either the outputs, or more importantly, the expertise. This is not to say that there is sufficient research, that capacity is adequate, or that topics are adequately covered. However, efforts to increase the uptake of science in decision making should consider information and expertise that is already available and develop mechanisms to access it, in addition to seeking to promote more and better research.

The relatively low input of academic science into policy advisory processes may be due to the lack of mechanisms by which IGOs can access these sources. Just as it is a daunting task for researchers to be aware of the potential routes of uptake for their research, it is a considerable task for IGO staff responsible for coordinating technical input into advice to be aware of relevant science being done in the wide range of circumstances described above, far less to be in communication with the researchers. This is a push-pull barrier that may contribute to the scarcity of direct scientific input into governance processes in the WCR also described by McConney et al. (2017).

In some regions there are specialized regional research organizations that provide technical input to regional IGOs, for example the International Council for Exploration of the Sea (ICES), in the northeast Atlantic, The North Pacific Marine Science Organization (PICES), in the north Pacific, and the Coastal Oceans Research and Development – Indian Ocean (CORDIO) program (Mahon et al., 2015). These organizations are directly connected to the science-policy interfaces that they serve. No such regional organization exists in the WCR. The likelihood of a research advisory organization being established for fisheries is low considering the relatively low revenue generating nature of the predominantly small-scale fisheries in the region; notwithstanding their high importance for livelihoods and food security (Oxenford and McConney, 2021). The tourism sector, which derives considerable revenue from healthy marine ecosystems, and could support such an organization, is yet to show any significant interest in contributing to marine ecosystem research or governance at the regional level.

Brokers/Boundary-Spanners

Given the documented inadequacy of established linkages between science producers and consumers, alternative mechanisms for bridging the science-policy gap and strengthening the application of BASE in decisions affecting ocean governance in the WCR needs to be explored. We are not suggesting efforts aimed at improving direct interactions between users and providers should be abandoned. However, given the ocean governance challenges inherent in the WCR (Fanning et al., 2021b), it seems pertinent to examine the potential role boundary spanning organizations and individuals might play in mitigating some of the more intractable challenges. These include social and financial capital, capacity building and socio-cultural factors stemming from a history of colonization across the region.

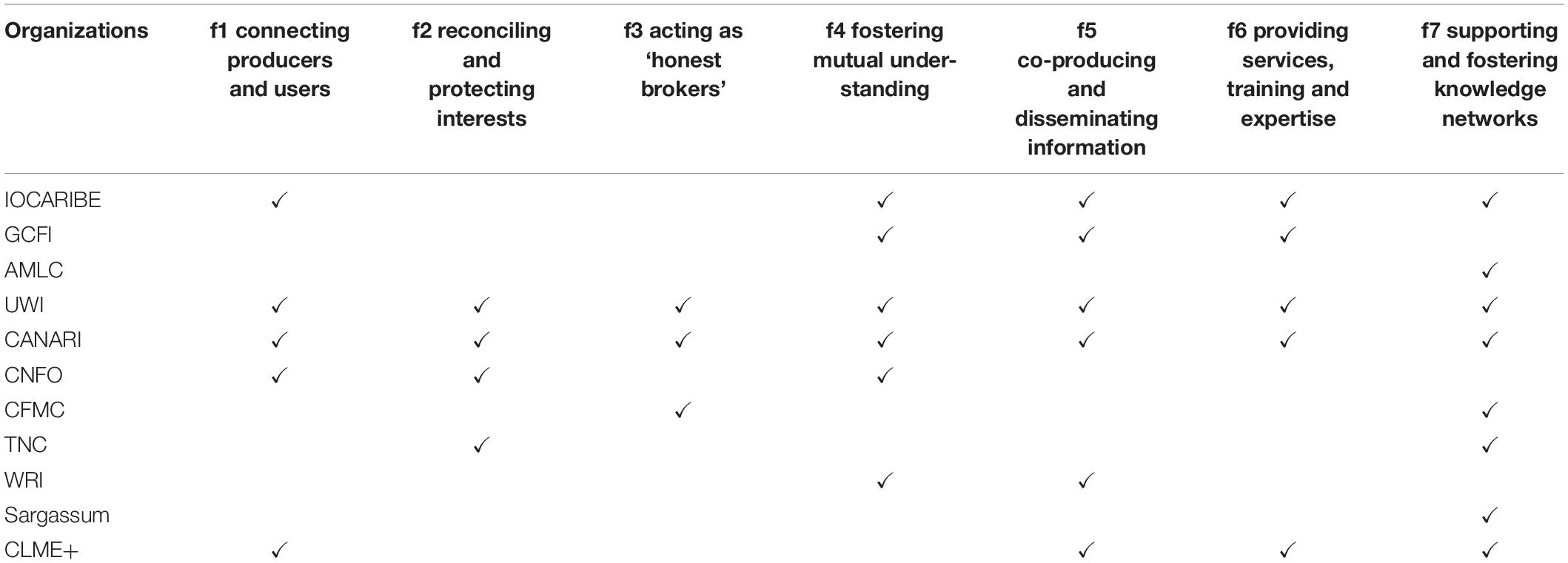

In addition to the regional (IGOs) reviewed, the activities of key NGOs that have been involved in regional science-policy interfaces in the WCR were evaluated to determine their actual and potential brokering/boundary spanning activities with reference to the seven functions of Goodrich et al. (2020), noted as f1–f7 in parentheses However, given the diversity of actors in science-policy arenas in the WCR, it is often difficult to determine their relative roles, as some actors may perform multiple roles as noted by Bednarek et al. (2018). For example, the same actors may at times engage in providing science inputs as academics and at other times as consultants; or the same actors may be science providers to advisory processes on some occasions and advisors at others.

IOCARIBE, IOC-UNESCO’s regional commission in the WCR has a mandate to promote and coordinate marine science (Table 1) (f1, f4–f7). Consequently, it might be expected to play a role in facilitating the strengthening of science-policy interfaces in the region. However, it does not have a mandate for any specific governance issue, or to function as a provider of science input for specific issues that are the mandates of other IGOs. Most of its advice is directed to its commission and is programmatic. However, some of its programs include workshops and conferences that bring science into the policy arena, result in direct advice to member countries; for example the development of a regional tsunami warning system6, or the Caribbean Marine Atlas7 (f4, f5). These have often linked regional with extra-regional experts, thus extending the scope of science input. IOCARIBE’s role in developing a boundary-spanning regional hub or platform to provide access to regional expertise, data and information through the Caribbean LME Initiative is discussed below (f7).

The Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute (GCFI), established in 1947, is a regional focal organization for fisheries research. Its annual conference brings scientists, fishers, managers, and policy advisors from around the region together. The conference includes workshops on topical issues aimed at generating applied advice. Through time, GCFI has embraced emerging topics such as sociology of fisheries and ecosystem-based management. This information is published in the conference proceedings. In this way it plays a role as a boundary organization (f4–f6), but this has not been formalized with the relevant IGOs and pertains only to fisheries. Its engagement with the previous and current phases of the Caribbean LME (CLME) Initiative reflects a more structured role as a boundary-spanner through the development of an information hub in the first phase and a science plan in the second phase (Acosta et al., 2020) (f7).

The members of the Association of Marine Laboratories of the Caribbean (AMLC) are marine laboratories of all types including extra-regional organizations with laboratories in the region (e.g., Smithsonian Institution and McGill University). It has 22 members which represent a considerable potential source of information and expertise. AMLC is well positioned to play a role as a broker/boundary-spanning organization. A proposal in 2010 that it should do so through association with the CLME Project, with which all regional IGOs were engaged, was not approved by the AMLC Board which noted that its role was to promote science rather than to link it to policy. A subsequent attempt by some AMLC Members to create a stand-alone ‘Cooperative Network of Marine Laboratories’ in 2014 did not gain the necessary financial support from donors. While AMLC only carries out function f7 incidentally. it has the potential to undertake other functions as well.

The University of the West Indies (UWI), while mainly a science provider, has also played a boundary spanning role as an institution. In 2011 it established the UWI Ocean Governance Network, a Google e-group linking 90+ faculty with an interest in oceans across its four campuses. The Network served as a forum for exchange among community members, and to link them to the needs of external agencies such as the CRFM and ACS with which it had MOUs (f1). However, it was not much used until 2015, when CARICOM took an integrated approach to negotiating the international legally binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement). In 2016 the Network was used to find four experts to join the overall CARICOM advisory team which included the CRFM, the OECS Commission and national experts. This time-bound ad hoc process is led by the Sustainable Development Desk at CARICOM Secretariat and the advice flows via that desk to the CARICOM negotiators at the United Nations Representations in New York. The UWI is a large institution within which individuals also carry out all of f1–f7, as noted for universities by Smith et al. (2018), albeit to different extents across its campuses and bodies. There is certainly considerable potential for UWI to become more mainstreamed as both science provider and boundary-spanner for the IGOs serving its member countries.

The Caribbean Natural Resources Institute (CANARI) is a regional NGO that focusses on small-scale livelihoods and inclusion of local stakeholders in national and regional governance. It sometimes functions as a science provider by generating social science information on community-based management. However, it also plays an organizing role by providing capacity building that enables local level engagement (f6), and by taking a programmatic approach to getting legitimate local and community level inputs into regional science-policy arenas (f1, f2). Notable is the development of the Civil Society Action Programme for the Sustainable Management of the Shared Living Marine Resources of the Caribbean and North Brazil Shelf LMEs (2018–2030) (CANARI, 2018). Indeed over the years in its many projects, CANARI has carried out all seven functions of Goodrich et al. (2020).

The Caribbean Network of Fisherfolk Organisation (CNFO) is a network of small-scale fisher folk and their organizations for CARICOM countries. In addition to their role in improving livelihoods for fisher folk, they play a role in fisheries governance and sustainable fisheries development by engaging with regional fisheries management organizations to ensure that the views of, and information from, small-scale fishers are represented in regional level decision-making (McConney and Phillips, 2011) (f1). As such, they serve as a boundary-spanning organization channeling information from a broad base of fisher folk through legitimate representation into regional fisheries processes (McConney et al., 2016b, McConney et al., 2017) (f2, f4). CNFO representatives have also played this role in global level processes such as the FAO Committee on Fisheries and the UN Oceans Conference.

The Caribbean Fishery Management Council (CFMC), is a national organization that adopted a regional role for queen conch fisheries. As one of eight US Fishery Management Councils established under the 1976 Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, its purpose is to conserve, restore and manage fishery resources in Puerto Rico and United States Virgin Islands. Nonetheless, it has become the lead agency in developing a regional fisheries management plan for queen conch. It has brought together all the regional fisheries bodies (CRFM, WECAFC, OSPESCA) and countries with significant queen conch resources to develop this plan, which is then taken up by the processes of the fisheries bodies (f3, f7). In this role it performs as a regional level boundary-spanning activity.

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is a large NGO with global reach and considerable activity in the WCR, mainly projects to manage marine ecosystems; especially through marine spatial planning and marine protected areas. However, there is also a component of information brokerage and advocacy at the regional level f2, f7). Its most notably technical initiative was its ecoregional planning program that mapped marine and terrestrial biodiversity in the insular Caribbean and proposed networks of protected areas for conservation (Huggins et al., 2007). This initiative marshaled a substantial amount of technical expertise and data, but ultimately did not have much uptake at the regional level. This is probably because it was not connected to any regional arrangement or process and the outputs did not have any champions within these arrangements. In another initiative, the TNC Caribbean Challenge Initiative played a central role in developing a regional program connecting sources of extra-regional funding for marine protected areas with high level national decision makers. This was technically supported by the Secretariat of the Cartagena Convention, the UNEP Caribbean Environment Programme (UNEP CEP) and resulted in several commitments to upscale protected area coverage.

The World Resources Institute is a large global NGO based in the United States. Its Reefs at Risk program integrated a wide variety of information on the status of reefs and related ecosystems globally with data on the pressures affecting them (Bryant et al., 1998). The Caribbean component of this initiative (Burke and Maidens, 2004) integrated information from a wide range of stakeholders (f4). The information was shared in a highly visual, easy to understand format which is fundamental to uptake (McConney et al., 2016a) (f5). The outputs were actively taken up by regional and national policy fora. That reefs were already high profile ecosystems connected to tourism and biodiversity concerns, and decision makers were under pressure from regional and global organizations to address reef degradation may also have promoted uptake in contrast to the TNC ecoregional planning initiative discussed above.

The ad hoc science-policy arena for the sargassum seaweed invasion WCR provides an example of an emergent boundary-spanning activity. In 2011 unprecedented massive influxes of pelagic sargassum seaweed took the Caribbean completely by surprise (McConney and Oxenford, 2020). They disrupted fishing and tourism activities as well as recreational use of beaches and the sea throughout the region. Influxes of sargassum have continued intermittently since 2011. There was no regional or subregional policy process or science-policy interface for this problem in the Eastern Caribbean (McConney and Oxenford, 2020). The response which emerged through the often fragmented efforts of the multiplicity of stakeholders was decidedly self-organized rather than centrally facilitated. Rather, was facilitated by stakeholders and various boundary-spanning activities on the part of regional and national organizations, that rapidly brought regional and extraregional science to bear on the problem which policy makers were flagging as critical (f7). However, communication among stakeholders and between the stages of the policy process was, and continues to be, a major challenge (McConney and Oxenford, 2020).

Projects may also play temporary boundary-spanning roles. A full review of regional and subregional projects that have played this role is beyond the scope of this paper. However, it has been noted that projects that adopt a boundary spanning role may leave a gap when the project ends, unless the project is designed to leave a mechanism in place to sustain that function. Two regional level examples illustrate this situation. The first is the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Assessment and Management Programme (CFRAMP) funded by the Canada International Development Agency (CIDA) from 1992 to 2004 which developed fisheries science and management capacity among CARICOM countries (Mahon, 2020). At its completion, it established the CRFM to continue that function (Haughton et al., 2004), which it continues to do (Table 1). The second example is the CLME Initiative, a suite of four GEF projects spanning 20+ years (Fanning et al., 2021b). The CLME Initiative engaged the major regional IGOs to promote an ecosystem-based approach to the major fisheries ecosystems in the WCR (f1). It supported pilot activities (f6) that brought science to bear on fisheries ecosystem issues and contributed advice into science-policy processes with the aim of strengthening them in a learning-by-doing mode (f5) (Fanning et al., 2009). Ultimately, the IGOs and countries of the WCR agreed that the role played by the CLME Initiative in integrating science and policy-making at the regional level should be continued by a regional coordination mechanism (f7) (CLME+ Project, 2013). The mechanism was designed (CLME+ Project, 2019) and adopted in principle by the countries in 2021, subject to national political approval. It is anticipated that this mechanism will be established in the next Phase of the CLME Initiative.

These examples of brokering/boundary-spanning activity serve to illustrate the diversity of circumstances to be found in the WCR that contribute to linking science production and policy making (Table 2). These instances can best be described as arising organically to meet the variety of needs rather than as deliberately planned by the institutional processes in the IGOs with a mandate to ensure sustainable use of marine ecosystems in the WCR. Notably only four organizations were seen to be addressing function two “Reconciling and protecting interests, different motivations, and cultures at the boundary and attending to issues of equity, unequal power, inclusivity, and trust building.” This is an important function if inputs of local and traditional knowledge holders is to be incorporated into decision making in a legitimate and trusted fashion.

Table 2. Preliminary assessment of organizations within the WCR demonstrating the boundary-spanning functions of Goodrich et al. (2020).

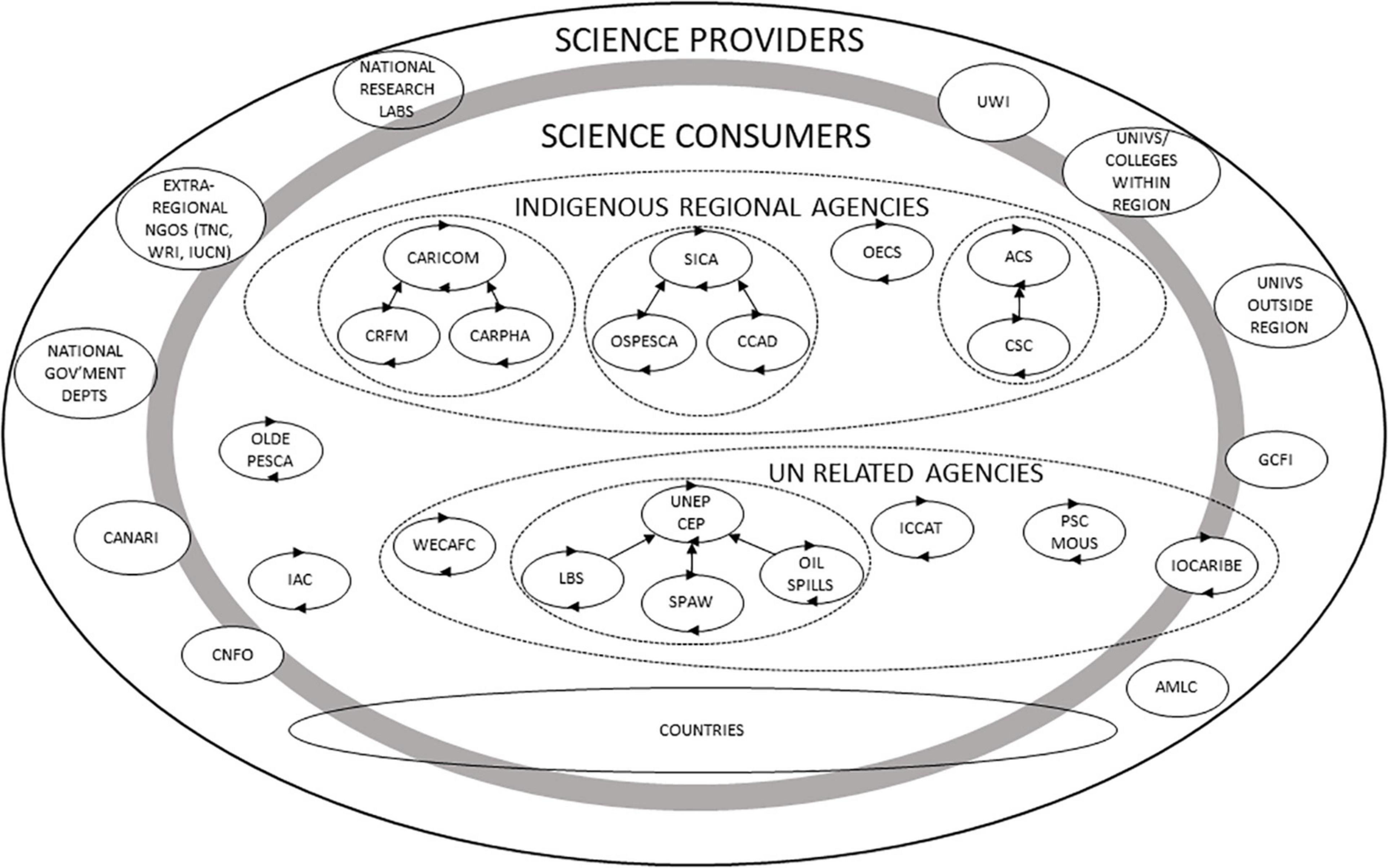

We are conscious that a more rigorous evaluation of boundary spanning activities for ocean governance in the WCR is needed. Figure 2 illustrates the key actors involved in enhancing the application of BASE in ocean governance decision making within the WCR and their roles as science providers, consumers and nascent boundary spanners. However, we are of the view that although most organizations reviewed undertake boundary spanning activities, none can be described as an boundary spanning organization designed for that purpose.

Figure 2. The organizations involved in regional science-policy arenas for ocean governance in the WCR. The gray ellipse is the boundary between science producers and science consumers. Arrows on ellipses indicate science-policy processes.

Improving Brokering/Boundary-Spanning Capacity in the WCR

This study has provided insight into the diversity of regional level boundary-spanning activities currently taking place in the WCR. However, only a few organizations could be identified as formally engaging in boundary spanning activities (IOCARIBE, CANARI, GCFI, CNFO), and this was not their primary function. This section explores what can be done to improve the effectiveness of boundary-spanning activities in the WCR as a means of improving the current science-policy arenas affecting the success of regional ocean governance. The lessons from this scoping study could also be useful to other ocean regions.

At the institutional level, there is the need for policy change in which the individuals and organizations responsible for using BASE in decision-making, are encouraged to recognize the distinct role of boundary-spanners, engage them, promote their activities and mainstream them into their organizations’ arrangements as suggested by Goodrich et al. (2020) and IASS et al. (2020). This could include promoting the establishment of formal boundary spanning organizations (Kennedy, 2018) noting their importance as ‘honest brokers’ that can operate at ‘arm’s length’ from policy makers (Boswell, 2018; Kennedy, 2018). At the same time, it is worth noting that successful boundary spanning linkages may be less about utilizing formal boundary organizations and more about fostering the process through which science and policy are intermingled (Jensen-Ryan and German, 2019). Consequently, a broad approach that focusses on practical actions such as developing web-based decision support tools and improving boundary spanning functions within existing IGOs should also be considered (Goodrich et al., 2020). Most already have some degree of internal boundary-spanning capability in the form of program officers who are technical generalists, or in-house specialist expertise, for example CRFM, while many have expertise supported by short-term funding or attached to projects. One approach to strengthening this capacity in IGOs would be the establishment of scientific advisory groups for IGOs as was proposed for the OECS Ocean Governance Team, drawing on the expertise of other regional institutions (Renard, 2020). Several of the IGOs already have technical advisory committees (Table 1), but the constitution of these and their effectiveness in bringing BASE into decision-making has not been evaluated in any case.

To support building the capacity of boundary-spanners, there is need for their functioning and effectiveness to be more thoroughly examined to understand their operations and impacts, and ultimately to prepare guidelines and best practices for their operation. Smith et al. (2018) emphasized the need to understand context before designing and implementing boundary management strategies. Similar studies in other global ocean regions leading to interregional learning may also be useful (Mahon and Fanning, 2019a). Posner and Cvitanovic (2019) note that such research will be a “challenging prospect as such impacts occur in complex social and ecological systems; involve subtle, gradual, and difficult-to-track changes; and elude conventional evaluation methods that fail to capture the complexity of real world science and decision-making contexts” (p. 141). The diversity of types and settings of boundary-spanning activities to be found in the WCR underscores their view. They also emphasize that such studies would help “clarify general principles for what success looks like and how to measure it.” Gluckman et al. (2021) provide an example of how analysis can generate recommendations for effectiveness. These studies could include application and testing of approaches such as the workshop model designed by Goldsmith et al. (2016) to bridge the gap between coastal and marine decision makers and scientists.

Among the practical activities needed to improve the connection between science and policy are mechanisms to improve access to the widely dispersed scientific capacity and sources of information within the WCR. Gorg et al. (2016) considered the strengths and weaknesses of two extreme approaches; a network model and a platform model. The former is less formal, and less resource intensive, but subject to the voluntary engagement of science providers for effective functioning. The latter is more formal and demanding of resources for its operation, but more reliable and comprehensive. The development of a mechanism to improve uptake of science in policy was planned in the 2011–2014 Phase of the CLME Initiative. It was to facilitate access by policy makers to science expertise throughout the region and thence to the desired data and information. The planned mode of operation was that in response to a query from a policy maker or advisor, a core team of three to five topic experts would be assembled. They in turn would engage with other experts, within and beyond the WCR, in a working group to address the question with the best available information and determine what additional research would be required. Teams would remain functional as long as needed, might change membership as the problem evolved, and could develop long-term relationships with the regional IGOs and other science users as appropriate. This initiative went as far as to establish an information hub, housed at the GCFI, but the mechanism was not attached to an institution, which was initially envisaged as being IOCARIBE. This mixed platform-network approach remains to be explored for the WCR. The CLME+ Hub for the Wider Caribbean currently being developed by the CLME+ Project has the potential to serve as such a mechanism, but will also need an institutional home that will proactively pursue the further development and operation of the mechanism (CLME+ Project, 2020). Given its mandate to promote uptake of science in policy making, the proposed regional coordination mechanism emerging from the CLME Initiative (CLME+ Project, 2020) will need to reflect carefully on this and other possible approaches.

Conclusion

This scoping study of science-policy arenas for ocean governance in the WCR finds that while regional IGOs provide the institutional basis for much of the uptake of science by regional ocean governance processes, the science-policy arenas are diverse, complex and interconnected. Many have some degree of internal boundary-spanning capability in the form of program officers and resident technical experts. While several have pathways to ministerial decision-making, they must often revert to their parent organization, which may be at the global level. Others have no access to ministerial level decision making and must rely on uptake at the national level or on champions from other IGOs with ministerial decision-making capacity to take the recommendations forward. The lack of decision-making bodies in several of the arrangements and their reliance on national uptake for implementation is a weak area in the regional science-policy arena in the WCR.

The regional science-policy landscape is further complicated by the occurrence of other science-policy arenas at the regional level that are emerging or not part of an established, regular regional process, for example, the sargassum issue and CARICOM’s engagement with its UN representations in formulating input to the BBNJ agreement. A regional strategy for improving the uptake of science into policy making must consider all of these arenas. The assignation of new and emerging issues such as sargassum to an IGO with a regular process for ocean issues could help ensure that they are taken up in established science-policy arenas.

The complexity of science-policy arenas in the WCR is likely to have considerable implication for efficacy of getting BASE into policy, as despite the existence of a variety of boundary spanning activities, the pathways from science producers to science users are often irregular, informal and unclear. While constraints imposed by this situation were not explicitly examined in this paper, it is inferred that it is likely to affect both science producers and boundary-spanners as they seek to engage with policy processes. Navigating this complex multi-organizational, multilevel system to ensure that advice reaches the appropriate forum and level requires understanding of the overall system, and the interaction among the IGO partners to determine entry points for science inputs. Developing and communicating this understanding is a key role for boundary-spanners.

The fact that a significant part of ocean governance policy in the WCR is externally driven, largely by UN organizations (e.g., FAO, UNEP, IMO, UNDOALOS) and global conventions (e.g., CITES, CBD, MARPOL) also contributes to the complexity of the science-policy arenas in the region. Of the regional integration IGOs, only the OECS Commission can be considered as having an indigenous subregional oceans policy. While the Caribbean Sea Commission of the ACS is in project implementation mode, neither CARICOM nor SICA have integrated ocean policy, despite prominent orientation toward Blue Economies for which such policies would seem essential (Clegg, 2021). The requirement to develop ocean policies formally informed by BASE by these IGOs would provide a clearer policy environment for boundary spanning.

In terms of strengthening the provision of accessible policy-relevant science, there is the need for science producers, their organizations (e.g., universities and research institutes) and their professional bodies (e.g., GCFI, AMLC) to develop mechanisms that provide more efficient access to their expertise and information. These mechanisms could facilitate establishing regional working groups to address specific problems and lead in turn to improved engagement within the science-policy arenas. Research institutions, especially in academia, could support this approach by giving researchers merit for engaging in science-policy arenas, and may find that policy-relevant science leads to increased funding. Ultimately, these mechanisms will come under the heading of boundary-spanning. There are examples of past and ongoing efforts in the WCR to build on and lessons to be learned from other regions as well.

No organizations established specifically for boundary spanning were found, and while boundary spanning activities were found to be taking place, largely informally, through efforts of a wide range of actors, there are significant gaps (Table 2). This role needs to be explicitly recognized and fostered by IGOs and other research consumers; even to the extent of encouraging the establishment of organizations whose primary role is boundary spanning. Some IGOs cultivate relationships with science providers often admitting them as permanent observers to their meetings, while others seldom do, or do so only for specific topics for which the observers’ input is considered necessary. A reorientation by IGOs to recognizing and encouraging brokers/boundary-spanners on a permanent and more integrated basis; indeed even strengthening their capacity, would enable them to better play their role and to engage in ongoing dialogue with both science providers and science users. This will also have the potential to move the science-policy relationship toward knowledge coproduction wherever appropriate and thus facilitate the incorporation of a broader range of BASE (Norström et al., 2020).

The diversity of ways in which boundary-spanning takes place in the WCR suggests that analysis of the effectiveness of boundary spanning activities in the region is needed to determine what works and what does not (Posner and Cvitanovic, 2019). In that way, rather than seeking to promote conventional approaches to boundary-spanning, WCR ‘bright spots’ can be identified and built on (Cvitanovic and Hobday, 2018). An analysis at the regional level regarding impacts of policy advice similar to that done at the national level by Kushner et al. (2012), could contribute to understanding efficacy and best practices for boundary-spanners in the region. It could also serve to illuminate the role of boundary-spanners for IGOs so that they can consider how best to engage with them. As noted by IASS et al. (2020), the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development may provide the opportunity and resources needed to pursue strengthening science-policy arenas.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

- ^ The term arrangement refers to an agreement and the organs and processes established to give effect to it.

- ^ In this study the term IGO refers to the entire arrangement.

- ^ Refer to Table 1 for full names of each IGO.

- ^ http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/mul167228.pdf

- ^ http://www.fao.org/tempref/FI/DOCUMENT/wecafc/15thsess/ref11e.pdf

- ^ https://www.ctic.ioc-unesco.org/

- ^ https://www.caribbeanmarineatlas.net/

References

Acosta, A. A., Glazer, R. A., Ali, F. Z., and Mahon, R. (2020). Science and Research Serving Effective Ocean Governance in the Wider Caribbean Region. Report for the UNDP/GEF CLME+ Project (2015-2020). Technical Report No.2. 185. Marathon, FL: Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute.

ACS/CERMES-UWI (2010). Report of the Expert Consultation on the Operationalisation of the Caribbean Sea Commission: Building a Science-Policy Interface for Ocean Governance in the Wider Caribbean, July 7th–9th, 2010. CERMES Technical Report No. 33. University Of The West Indies, Cave Hill Campus: CERMES.

Bednarek, A. T., Shouse, B., Hudson, C. G., and Goldburg, R. (2015). Science-policy intermediaries from a Practitioner’s perspective: the lenfest ocean program experience. Sci. Public Pol. 43, 291–300. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scv008

Bednarek, A. T., Wyborn, C., Cvitanovic, C., Meyer, R., Colvin, R. M., Addison, P. F. E., et al. (2018). Boundary-spanning at the science–policy interface: the Practitioners’ perspectives. Sustain. Sci. 13, 1175–1183. doi: 10.1007/s11625-018-0550-9

Borja, A., Elliott, M., Snelgrove, P. V., Austen, M. C., Berg, T., Cochrane, S., et al. (2016). Bridging the gap between policy and science in assessing the health status of marine ecosystems. Front. Mar. Sci. 3:175. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00175

Boswell, J. (2018). Keeping expertise in its place: understanding Arm’s-length bodies as boundary organizations. Policy Polit. 46, 485–501. doi: 10.1332/030557317x15052303355719

Bryant, D., Burke, L., McManus, J., and Spalding, M. (1998). Reefs at Risk: a Map-Based Indicator of Threats to the World’s Coral Reefs. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 114.

Burke, L., and Maidens, J. (2004). Reefs at Risk in the Caribbean. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

CANARI (2018). Civil Society Action Programme for the Sustainable Management of the Shared Living Marine Resources of the Caribbean and North Brazil Shelf Large Marine Ecosystems (2018-2030). Port-of-Spain: CANARI, 27.

CCAD (2020). Screening Tool for the Implementation of WWF Policies and Safeguards to the Model Projects of the Integrated Ridge to Reef Management of the Mesoamerican Reef Ecoregion MAR2R. Antiguo Cuscatlán: Central American Commission on Environment and Development.

Chakalall, B., Mahon, R., and McConney, P. (1998). Current issues in Fisheries Governance in the Caribbean Community (CARICOM). Mar. Pol. 22, 29–44. doi: 10.1016/s0308-597x(97)80002-4

Chilvers, J., and Evans, J. (2009). Understanding networks at the science–policy interface. Geoforum 40, 355–362.

Clegg, P., Mahon, R., McConney, P., and Oxenford, H. A. (eds) (2021). The Caribbean Blue Economy. Oxford: Routledge.

CLME Project+ (2011). Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem Regional Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis. The UNDP/GEF Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem and Adjacent Areas (CLME) Project, Cartagena, Colombia. Cartagena: CLME Project, 138.

CLME+ Project (2013). The Strategic Action Programme for the Sustainable Management of the Shared Living Marine Resources of the Caribbean and North Brazil Shelf Large Marine Ecosystems (CLME+ SAP). Cartagena, CO: Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem Project.

CLME+ Project (2019). Proposals for a Permanent Coordination Mechanism and a Sustainable Financing Plan for Ocean 2 Governance in the Wider Caribbean region. London: Centre for Partnerships for Development. Available online at: http://gefcrew.org/carrcu/18IGM/10SPAWCOP/Ref-Docs/CAD_CLME+_PCM-en.pdf

CLME+ Project (2020). Proposals for a Permanent Coordination Mechanism and a Sustainable Financing Plan for Ocean Governance in the Wider Caribbean Region. Centre of Partnerships for Development (GlobalCAD), Barcelona, Spain. Barcelona: GlobalCAD, 121.

Cook, C. N., Mascia, M. B., Schwartz, M. W., Possingham, H. P., and Fuller, R. A. (2014). Achieving conservation science that bridges the knowledge–action boundary. Conserv. Biol. 27, 669–678. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12050

Cooke, A. L. (2017). Evaluating Regional Governance Arrangements for Living Marine Resources in the Wider Caribbean Region. Ph.D thesis. University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus: CERME.

CRFM. (ed.) (2019). CRFM Research Paper Collection, Vol. 9. Belize City: Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism.

Cvitanovic, C., and Hobday, A. J. (2018). Building optimism at the environmental science-policy practice interface through bright spots. Nat. Commun. 9:3466. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05977-w

Deane, L., and McConney, P. (2011). Communication between marine science and policy in the eastern Caribbean. Proc. Gulf Caribb. Fish. Inst. 63, 406–410.

Debels, P., Fanning, L., Mahon, R., McConney, P., Walker, L., Bahri, T., et al. (2017). The CLME+ strategic action programme: an ecosystems approach for assessing and managing the Caribbean Sea and North Brazil shelf large marine ecosystems. Environ. Dev. 22, 191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2016.10.004

Degger, N., Hudson, A., Mamaev, V., Hamid, M., and Trumbic, I. (2021). Navigating the complexity of regional ocean governance through the Large Marine Ecosystems Approach. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:645668. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.645668

Driscoll, C. T., Fallon Lambert, K., and Weathers, K. C. (2011). Integrating science and policy: case study of the Hubbard brook research foundation science links program. BioScience 61, 791–801. doi: 10.1525/bio.2011.61.10.9

Fanning, L., Al-Naimi, M. N., Range, P., Ali, A. S. M., Bouwmeester, J., Al-Jamali, F., et al. (2021a). Applying the ecosystem services-EBM framework to sustainably manage Qatar’s coral reefs and seagrass beds. Ocean Coast. Manag. 205:105566. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105566

Fanning, L., and Mahon, R. (2021). Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem+ Strategic Action Plan Monitoring Report: Baseline 2011-2015. Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies, CERMES Technical Report No. 100. The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus: CERME, 98.

Fanning, L., Mahon, R., Compton, S., Corbin, C., Debels, P., Haughton, M., et al. (2021b). Challenges to implementing regional ocean governance in the Wider Caribbean Region. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:286. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.667273

Fanning, L., Mahon, R., and McConney, P. (2009). Focusing on living marine resource governance: the Caribbean large marine ecosystem and adjacent areas project. Coast. Manag. 37, 219–234. doi: 10.1080/08920750902851203

Fanning, L., Mahon, R., and McConney, P. (2013). Applying the large marine ecosystem (LME) governance framework in the Wider Caribbean Region. Mar. Pol. 42, 99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2013.02.008

Fanning, L., Mahon, R., McConney, P., Angulo, J., Burrows, F., Chakalall, B., et al. (2007). A large marine ecosystem governance framework. Mar. Pol. 31, 434–443. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2007.01.003

Fanning, L., Mahon, R., and McConney, P., eds (2011). Towards Marine Ecosystem-based Management in the Wider Caribbean. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 426.

Fanning, L., Mahon, R., Baldwin, K., and Douglas, S. (2015). Transboundary Waters Assessment Programme (TWAP) Assessment of Governance Arrangements for the Ocean: Transboundary Large Marine Ecosystems. IOC Technical Series, 119: 80, Vol. 1. Paris: IOC-UNESCO.

Fleming, J. (2018). Recognizing and resolving the challenges of being an insider researcher in work-integrated learning. Int. J. Work Integr. Learn. 19, 311–320.

Geoghegan, T. (2015). Regional Policy Harmonisation as a Bridge Between Global and National Policy Arenas: the St. George’s Declaration on Principles for Environmental Sustainability in the Eastern Caribbean. Case Study. Port of Spain: Caribbean Natural Resources Institute (CANARI).

Gluckman, S. P. (2018). The role of evidence and expertise in policy-making: the politics and practice of science advice. J. Proc. R. Soc. N. S. W. 151(Pt 1), 91–101.

Gluckman, P. D., Bardsley, A., and Kaiser, M. (2021). Brokerage at the science–policy interface: from conceptual framework to practical guidance. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8:84. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00756-3

Goldsmith, K., Granek, E., Lubitow, A., and Papenfus, M. (2016). Bridge over troubled waters: a syn-thesis session to connect scientific and decision making sectors. Mar. Pol. 70, 30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.04.015

Goodrich, K. A., Sjostrom, K. D., Vaughan, C., Nichols, L., Bednarek, A., and Lemos, M. C. (2020). Who are boundary-spanners and how can we support them in making knowledge more actionable in sustainability fields? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 42, 45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.001

Gorg, C., Wittmer, H., Carter, C., Turnhout, E., Vandewalle, M., Schindler, S., et al. (2016). Governance options for science–policy interfaces on biodiversity and ecosystem services: comparing a network versus a platform approach. Biodivers. Conserv. 25, 1235–1252. doi: 10.1007/s10531-016-1132-8

Gudmundsson, H. (2003). The policy use of environmental indicators–learning from evaluation research. J. Transdiscip. Environ. Stud. 2, 1–12.

Gustafsson, K. M., Wolf, S. A., and Agrawal, A. A. (2017). Science-policy-practice interfaces: emergent knowledge and monarch butterfly conservation. Environ. Pol. Gov. 27, 521–533. doi: 10.1002/eet.1792

Guston, D. H. (2001). Boundary organizations in environmental policy and science: an introduction. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 26, 399–408. doi: 10.1177/016224390102600401

Hartley, T. W. (2016). “When scientific uncertainty is in the eye of the beholder: using network analysis to understand the building of trust in science,” in Science, Information, and Policy Interface for Effective Coastal and Ocean Management, eds B. H. MacDonald, S. S. Soomai, E. M. De Santo, and P. G. Wells (London: CRC Press), 175–202. doi: 10.1201/b21483-11

Haughton, M. O., Mahon, R., McConney, P., Kong, G. A., and Mills, A. (2004). Establishment of the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism. Mar. Pol. 28, 351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2003.08.002

Huggins, A. E., Keel, S., Kramer, P., Núñez, F., Schill, S., Jeo, R., et al. (2007). Biodiversity Conservation Assessment of the Insular Caribbean Using the Caribbean Decision Support System. Technical Report. Arlington, TX: The Nature Conservancy, 112.

IASS, IDDRI, and TMG (2020). Marine Regions Forum 2019: Achieving a Healthy Ocean–Regional Ocean Governance Beyond 2020. Conference Report. Marine Regions Forum 2019, 30 September–2 October 2019. Berlin: Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, 109. doi: 10.2312/iass.2020.001

Jensen-Ryan, D. K., and German, L. A. (2019). Environmental science and policy: a meta-synthesis of case studies on boundary organizations and spanning processes. Sci. Public Pol. 46, 13–27. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scy032

Jordan, A., Huitema, D., Schoenefeld, J., Van Asselt, H., and Forster, J. (2018). “Governing climate change polycentrically: setting the scene,” in Governing Climate Change: Polycentricity in Action?, Vol. 2018, eds A. Jordan, D. Huitema, H. Van Asselt, and J. Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 3–25.

Kennedy, E. B. (2018). Supporting Scientific Advice through a boundary organization. Glob. Challeng. 2:1800018. doi: 10.1002/gch2.201800018

Kushner, B., Waite, R., Jungwiwattanaporn, M., and Burke, L. (2012). Influence of Coastal Economic Valuations in the Caribbean: Enabling Conditions and Lessons Learned. Washing, DC: World Resources Institute.

Levina, N., and Vaast, E. (2005). The emergence of boundary spanning competence in practice: implications for implementation and use of information systems. MIS Q. 29:2.

MacDonald, B. H., Soomai, S. S., De Santo, E. M., and Wells, P. G. (2016). “Understanding the science–policy interface in integrated coastal and ocean management,” in Science, Information, and Policy Interface for Effective Coastal and Ocean Management, eds B. H. MacDonald, S. S. Soomai, E. M. De Santo, and P. G. Wells (London: CRC Press), 20–43.

Mahon, R. (2020). Exploring scale in ocean and coastal governance in the Wider Caribbean. Gulf Caribb. Res. 31, xxix–xlviii. doi: 10.18785/gcr.3101.06