94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci., 10 May 2021

Sec. Marine Affairs and Policy

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.652778

This article is part of the Research TopicIntegrated Marine Biosphere Research: Ocean Sustainability, Under Global Change, for the Benefit of SocietyView all 31 articles

Limited progress has been made in implementing integrated coastal and marine management (ICM) policies globally. A renewed commitment to ICM in Canada offers an opportunity to implement lessons from previous efforts over the past 20 years. This study applies three core ICM characteristics identified from the literature (formal structures; meaningful inclusion; and, innovative mechanisms) to identify opportunities for operationalizing ICM from participants’ lived experiences in Atlantic Canada. These characteristics are employed to assess and compare ICM initiatives across two case studies in the Upper Bay and the Lower Bay of Fundy. The assessments are based on semi-structured interviews conducted with key participants and a supplementary document analysis. The following insights for future ICM policies were identified: adaptive formal structures are required for avoiding previous mistakes; a spectrum of approaches will support meaningful engagement in ICM; local capacity is needed for effective innovative mechanisms; and, policy recommendations should be implemented in parallel. Although these insights are relevant to each of the two sub-regional case studies, the paths taken to incorporating and realizing them appear to be location-specific. To account for these site-specific differences, we suggest more attention be given to strategies that incorporate local history, unique capacity of actor groups and location-specific social-ecological systems objectives. We provide the following recommendations on policy instruments to assist in moving toward enhanced regional ICM in the Bay of Fundy, and that may also be transferable to international ICM efforts: update policy statements to incorporate lessons from previous experiences; strengthen commitment to ICM in Federal law; create a regional engagement strategy to enhance involvement of local actor groups; and, enhance the role of municipal governments to support local capacity building and appropriate engagement of local actors in ICM processes.

Current limitations of conventional sector-based coastal and marine management can only be resolved through the adoption of more integrated approaches. Limitations include a failure to adopt holistic approaches (i.e., that embrace ecological, economic, socio-cultural, and institutional objectives), resulting in conflict between actor groups, an inability to evaluate cumulative impacts, and segregated planning and decision-making mechanisms (Borja et al., 2016; Visbeck, 2018; Stephenson et al., 2019). Integrated coastal and marine management (ICM) seeks to address multiple objectives across many activities and has been attempted to maintain or restore ecological integrity (including biological productivity, biodiversity, and habitat) and to enhance the quality of life while pursuing economic development opportunities (Burbridge, 2004; Cicin-Sain and Belfiore, 2005). ICM offers a holistic and strategic form of governance that is necessary in the pursuit of sustainable development or “social-ecological harmony” (Fairbanks et al., 2019). There is, however, no general agreement on what characteristics of governance are most appropriate for implementing ICM initiatives (Ngoran and Xue, 2017), and many nation states, such as Canada, have been experimenting with various governance arrangements over the last two decades. The development of ecosystem-based processes and marine spatial planning (MSP) has reinvigorated efforts to implement ICM, yet many of these new initiatives are not achieving desired outcomes (Kelly et al., 2019).

We critically examine future opportunities for operationalizing ICM and identify core insights using a governance lens. The Bay of Fundy in Atlantic Canada was selected for an embedded case study due to its rich history of past and ongoing experiments in integrated management. Specifically, this study provides perspectives from local and regional actors and rights holders from two sub-regions within the Bay of Fundy that have seen many previous efforts toward ICM. This empirical research contributes to the global discourse on participation within ICM. We hope that this paper will provide ‘food for thought’ for authorities and practitioners who continue to develop and implement initiatives (e.g., policies, plans, and programs) within coastal and marine social-ecological systems (SES) and may inform action within other local, regional, and international initiatives. This empirical assessment of longstanding experiences of ICM initiatives in Canada can contribute to our understanding of how integration can be achieved. Critical to this assessment is the need to further understand how actors have experienced and learned from participating in ICM efforts in Canada. As we prepare to enter the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) (United Nations, 2020), the timing seems propitious to synthesize insights from past efforts and to alter the present approach for achieving multiple objectives across activities within the coastal and marine social-ecological systems. In particular, approaches that include governments and non-state actor groups may contain beneficial lessons.

The next section provides an overview of the core governance characteristics identified from a review of international literature on ICM, which includes as the process of planning, implementing, monitoring and evaluation/adaptation (Olsen, 2002; Ehler, 2003). We then introduce two case study contexts within the Bay of Fundy and describe our qualitative approach. Third, we synthesize opportunities for advancing the operationalization of ICM from each case study. Finally, we discuss themes that emerged from analysis across the two case studies and propose a common pathway forward for the Bay of Fundy to inform current actions being taken in Canada as they relate to the operationalization of ICM.

The rise of ICM can be viewed as part of a general shift from government, conventionally one set of state actors, to governance that includes multiple actors beyond government within management decision making processes. There is a need to focus on the approaches used for multiple actor groups to participate in oceans governance through combined arrangements (e.g., shared or multi-level) (Rhodes, 1996; Stoker, 1998; Salamon, 2002). Governance is defined here as the way actor groups in society interact and coordinate to steer social and political processes (Bennett and Dearden, 2014). In the wider setting of oceans governance and management, the practices of top–down (centralized) (Christie and White, 2007; Gilliland and Laffoley, 2008) and bottom–up (decentralized) approaches (Lane and Stephenson, 2000; Wever et al., 2012) have been documented. There is, however, agreement among scholars that neither a purely top–down nor a bottom–up approach will be sufficient when seeking to instigate more integrated approaches to coastal and marine governance (Stohr et al., 2014; Rockmann et al., 2015; Bennett, 2019). It is critically important that we assess how recent governance arrangements have facilitated or impeded the implementation of ICM. Additionally, research indicates that a vital challenge for coastal and marine governance is how to fit it to the local realities of coastal communities (Young et al., 2018). Decision-makers and practitioners must, therefore, consider underlying governance to better facilitate the operationalization of ICM initiatives.

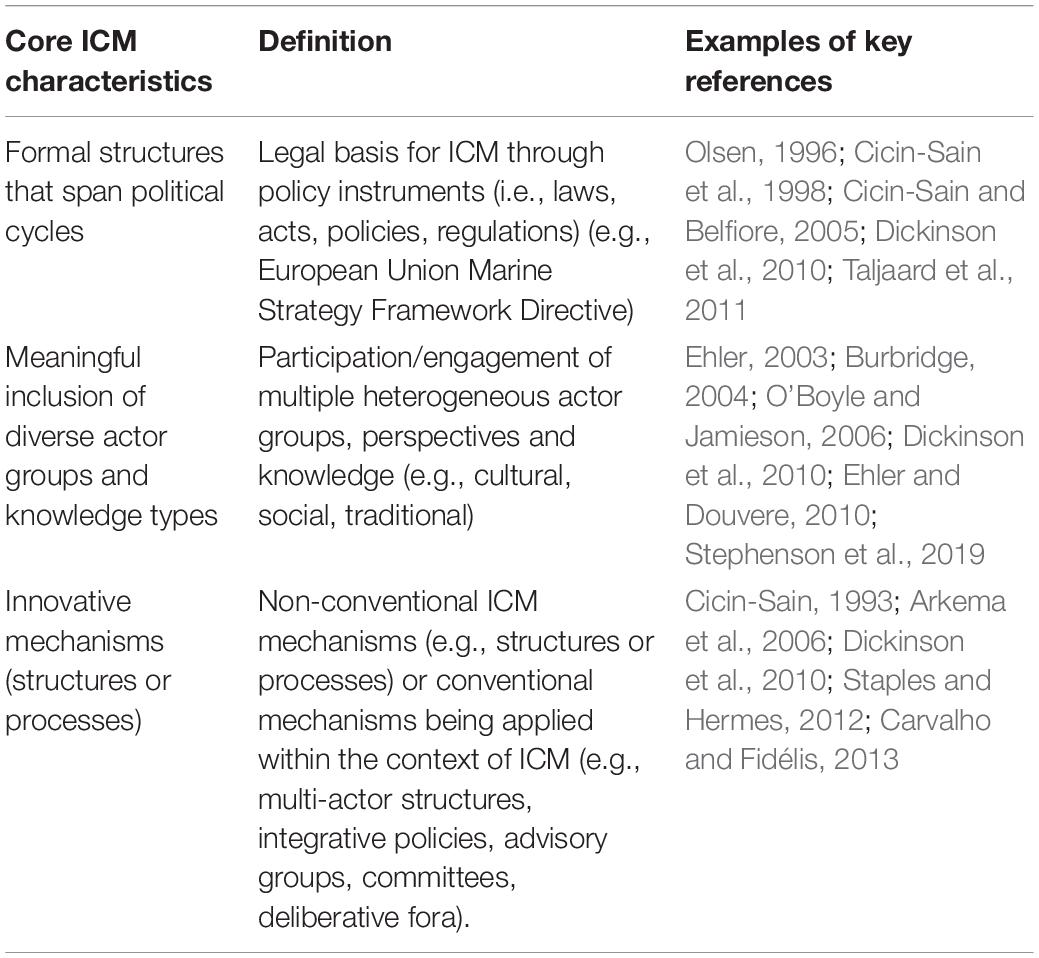

Core governance-related characteristics have recently been determined to be critical to operationalizing ICM initiatives. Three core ICM characteristics were identified through a systematic review that assessed the prevalence and importance of governance characteristics within ICM initiatives (Sorensen, 1997; Ehler, 2003; Stojanovic et al., 2004; Gilliland and Laffoley, 2008; Eger and Courtenay, 2021):

• formal structures that span political cycles;

• meaningful inclusion of diverse actor groups and knowledge types; and,

• innovative multi-actor mechanisms.

The three characteristics are defined and distinguished below and used to frame the embedded case analysis of two sets of sub-regions in the Bay of Fundy.

Formal structures provide the legal foundation for ICM through policy instruments (e.g., laws, acts, regulations). For example, ICM policy can generate top-down commitment and leadership from authorities (e.g., government departments) to develop a holistic strategy for the management of coasts and oceans (e.g., Christie and White, 2007; Gilliland and Laffoley, 2008). Additionally, formal structures can acknowledge a diverse set of actors to be involved during the operationalization of ICM initiatives. Formal structures that span political structures, and cycles, can also set standards to ensure expectations are met and trade-offs are considered across scales (Pomeroy and Douvere, 2008). For example, such formal structures might direct or support stakeholder mapping or scenario planning. In a comparative policy study of Brazil and Indonesia, Wever et al. (2012) found that ineffective formal structures prevented the implementation of ICM. Other nations in which formal structures have catalyzed action toward ICM include Canada (Oceans Act), United States (National Marine Act), and European Union (Marine Strategy Framework Directive). Further, several countries have also established formalized mechanisms facilitating participation of local, non-state actors in decisions relating to coastal and marine areas: Norway (Buanes et al., 2005); Australia (Vince, 2008, 2014); and, China (Xue et al., 2004).

Meaningful inclusion of diverse actor groups and knowledge types (e.g., social, cultural, traditional, local) is recognized as a key feature in successfully operationalizing ICM (Flannery et al., 2018; Stephenson et al., 2019). Kooiman et al. (2008, p. 3) state that “broad societal participation in governance is an expression of democracy.” Discussion has evolved over the years around who should participate in ICM and how (Kearney et al., 2007; Flannery et al., 2019). An ongoing debate in the ocean governance literature is whether the government should decide how local actor groups participate (Ehler and Douvere, 2010) or whether local actor groups should be involved in deciding for themselves (Ritchie and Ellis, 2010; Fudge, 2018). Participation is conceptualized here broadly as an umbrella term for a spectrum of approaches or strategies for understanding and sharing perspectives on the impacts of decisions (Arnstein, 1969; Hurlbert and Gupta, 2015; Morf et al., 2019; Twomey and O’Mahony, 2019). The value of local actor participation in coastal governance and management is well established, for example, within ICM initiatives such as MSP (Pomeroy and Douvere, 2008; Ritchie and Ellis, 2010; Flannery et al., 2018). Furthermore, communities, defined here as a place-bounded group of heterogeneous actor groups with diverse values and interests, are increasingly being recognized for their capacity to catalyze and lead ICM initiatives. Wiersema (2008) argues that the participation of multiple actors is beneficial for obtaining social license, understanding the complexity of environmental problems, and identifying actionable goals that are needed to move toward effective results.

Innovative mechanisms, through which structure and process are implemented, have been identified as an important characteristic of governance. In particular, mechanisms that ensure that ICM initiatives are relevant to the local situation often involve a forum in which local actors, authorities and decision-makers can interact (Parlee and Wiber, 2014; Eger and Courtenay, 2021). These can include new or existing informal and formal venues or forums that allow, or even require, particular constituencies to interact and contribute to decision-making. Existing mechanisms or venues such as integrative policies, advisory groups, committees and deliberative spaces, that have been developed within other contexts, are showing success when being applied novelly within the context of ICM (UNEP/CBD, 2005; Eger and Courtenay, 2021). It remains critical to determine the appropriate balance of state and non-state actor group participation that is suited to a given local context. In most nations, as well as for ICM, government authorities tend to ultimately have the legal responsibility for decisions. Given the growing experience with ICM globally, there is value in exploring new and existing mechanisms to enhance participation of local and non-state actors in ICM. Such mechanisms would not only promote good governance values and assist in achieving transparency, but also in working toward broader and more desirable social and environmental outcomes (e.g., inclusivity, equity, and sustainable livelihoods) (Wingqvist et al., 2012). The application of existing mechanisms refers to those being used in other contexts and reflects the creativity needed to overcome governance challenges across contexts.

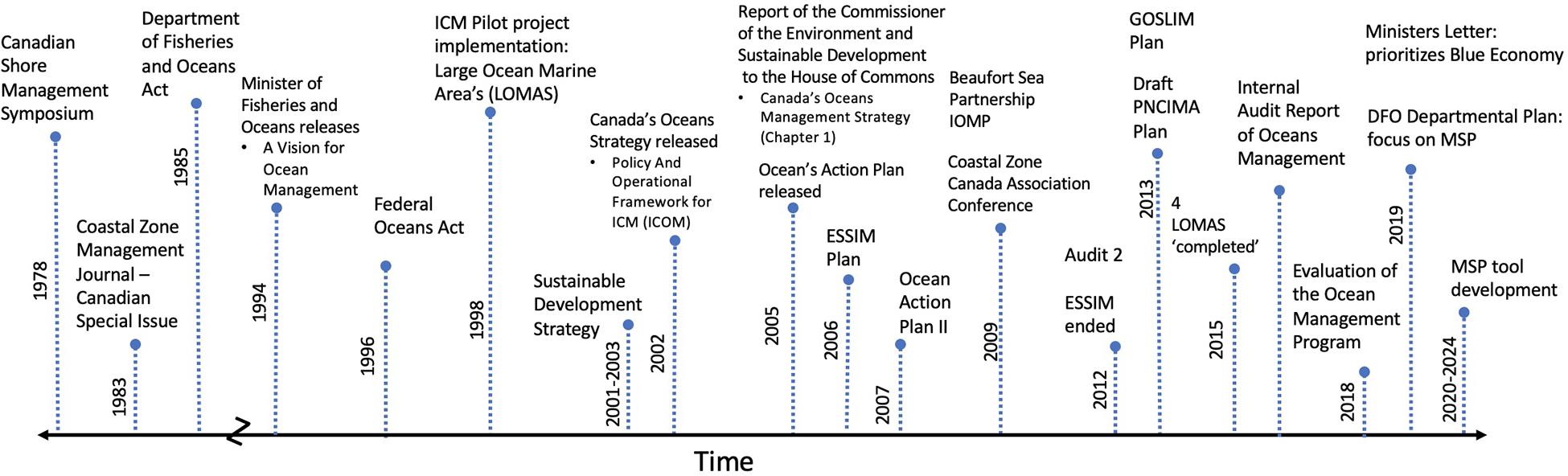

Canada recognized the need for ICM relatively early on in the evolution of ICM; however, as with other nations, the move from concept to practice has been slow or stalled. At the time of promulgation (January 31, 1997), Canada’s Oceans Act represented the first step toward ICM through legislation/policy both within Canada and internationally. This followed the formal conception of ICM broadly in the Rio Declaration at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (United Nations Sustainable Development, 1992). Figure 1 depicts some of the important actions and events relating to Canadian ICM beginning in the late 1970s. To ICM that began during 1978–1983 with a national conference (Canadian Council of Resource and Environment Ministers [CCREM], 1978) and a Canadian Special issue in Coastal Zone Management (Harrison and Parkes, 1983). In 1985 the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Act established a formal branch to coordinate oceans policies and programs (Canada, 1985).

Figure 1. Timeline of key ICM efforts/events in Canada from 1978 to 2020. *ESSIM, Eastern Scotian Shelf Integrated Management Plan; GOSLIM, Gulf of St. Lawrence Integrated Management Plan; PNCIMA, Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area.

Implementation of ICM in Canada has varied over time, and has been characterized as “slow” (Office of the Auditor General, 2005, p. 12), “from glacial to hectic” (Ricketts and Harrison, 2007), “progress or paralysis” (Ricketts and Hildebrand, 2011) and “from leader to follower” (Jessen, 2011). Much of the progress with ICM in Canada can be attributed to ICM pilots in five large ocean management areas (LOMAS) beginning in 1998. Four of the five LOMAS currently have plans, although none have been fully operationalized: Beaufort Sea, Pacific North West, Gulf of Saint Lawrence, and Eastern Scotian Shelf (Ricketts and Hildebrand, 2011; McCuaig and Herbert, 2013; Bailey et al., 2016) (Figure 1). In 2005, the Office of the Auditor General suggested progress had not been made due to ICM not being a consistent priority of the Federal Government (Office of the Auditor General, 2005). Canada’s inability to realize the original vision of ICM articulated in the Oceans Act and subsequent policy documents (i.e., Ocean Action Plan, Ocean Strategy and Policy and Operational Framework for ICOM, Ocean Action Plan I) is attributed in part to piecemeal, fragmented and scattered policies (Office of the Auditor General, 2005). Most recently, ICM is referenced in current departmental plans and ministerial mandate letters, in which the Prime Minister has indicated to certain Ministers his expectations for their contributions to the Blue Economy and MSP.

The Government of Canada has acknowledged the importance of involving multiple actor groups in decision-making for Canadian coasts and oceans through the Oceans Act and its supporting policy documents, and instruments (Government of Canada, 1996; Canada, 2002; Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, 2018; Minister of Fisheries Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard, 2019). The preamble of the Oceans Act clearly states the intention of implementing an integrated approach through the coordination of both state and non-state actor groups and within government departments/sectors (Government of Canada, 1996). Further, the subsequent Ocean Strategy (Canada, 2002; Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2002) also outlines suggestions for fostering collaboration with other ministries, Indigenous Peoples and coastal communities and indicates that the Strategy itself is meant to evolve as lessons are learned through adaptive management processes (Chircop and Hildebrand, 2006). In 2005 the Oceans Action Plan recognized that the governance of Canada’s oceans is “not equipped to deal with modern-day challenges” (Office of the Auditor General, 2005). Instead, what is needed over the long term is envisioning ICM as a cross-sectoral and collaborative approach to decision-making that “encourages the direct involvement of resource users and coastal communities” (Vodden, 2015, p. 18).

The reality that activities are managed by different government departments, each with its own mandate, resources and priorities makes it challenging for one department to have sole responsibility, and capacity/ability, for implementing ICM (Jessen, 2011; Nursey-Bray, 2016). The Office of the Auditor General has reported that both top-down and community-driven efforts toward ICM are required; yet, as of 2005, the Oceans Strategy had failed to provide specific “responsibility for leadership” (Office of the Auditor General, 2005, p. 9). Unfortunately, as noted by the CoastalCURA (2019), there has not been a substantial change since,

Despite the existence of policies that encourage the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) to work “in partnership” with local stakeholders (such as the Oceans Act), opportunities for representation of local voices are still greatly lacking when assessing the costs and benefits of a decision to these communities.

Scholars have identified that strong political presence and support are needed in addition to active local-regional involvement of the community and non-governmental institutions in order to achieve ICM (Guenette and Alder, 2007). Along with other nations, Canada has learned that definitions and legal support for achieving effective participation of affected actors are variable and remain critical challenges in practice (Wilson and Wiber, 2009; Charles, 2010; Twomey and O’Mahony, 2019). Ongoing criticisms of previous ICM efforts in Canada include the weak policy basis that exists for ICM, specifically the lack of formal structures that span political cycles, support meaningful inclusion and innovative multi-actor mechanisms. In particular, there is a need for more governance mechanisms to support leadership, community participation and engagement in coastal and ocean resource management (Charles, 2010; Jessen, 2011; Vodden, 2015). A limitation of the Oceans Act is that it “has not adequately provided the mechanisms for ensuring a strong role for communities in integrated coastal and ocean management” (Kearney et al., 2007, p. 79). Scholars have acknowledged that coastal communities and local actors (e.g., Indigenous peoples and small-scale fish harvesters) must have priority for access to coastal and marine resources and spaces to avoid negative or unintended consequences and trade-offs (Bennett, 2018; Bennett et al., 2018). As a result of these lessons, we are beginning to see novel governance arrangements throughout Canada for navigating emerging coastal and marine social-ecological system issues through an ICM approach (e.g., the Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area). Making these new arrangements functional remains a work in progress.

Recently, Canada has shown a renewed commitment to an integrated approach to the management of coastal and marine systems. For example, the Minister of Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) was instructed to implement the G7 Charlevoix Blueprint for Healthy Oceans, Seas and Resilient Coastal Communities (G7, 2018) in the 2019 mandate letter (Minister of Fisheries Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard Mandate Letter, 2019). The 2019–2020 DFO Departmental Plan includes explicit language that supports ICM as well as a combined approach to develop and implement a marine spatial plan (Minister of Fisheries Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard Mandate Letter, 2019, p. 17).

DFO will initiate MSP in five marine areas. MSP is a process that will bring together relevant authorities to better coordinate the use and management of marine spaces to achieve ecological, economic, and social objectives. One of the key features of these MSP processes will be the establishment of Indigenous-Federal-Provincial governance structures. The goal for each planning area will be the development of a marine plan that sets out the long-term spatial objectives and includes shared accountabilities for implementation. This process will not replace existing regulatory processes but will offer a forum to advance cross-sector planning.

There remains an opportunity to learn from past experiences to identify and create new innovative governance mechanisms to achieve core ICM characteristics.

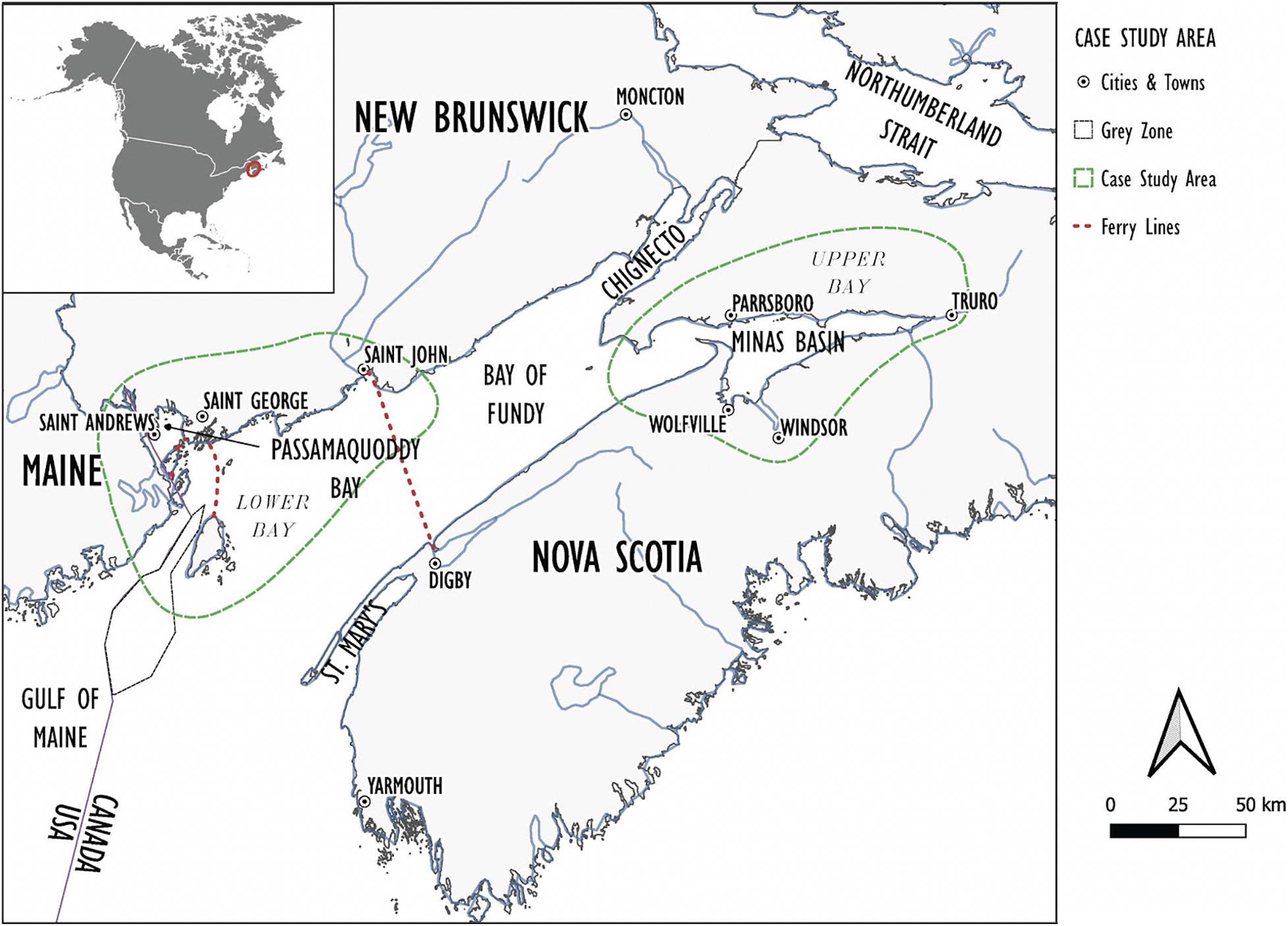

The Bay of Fundy has the highest tides in the world and includes many diverse and ecologically significant ecosystems (e.g., seagrasses, mudflats, estuaries). Although the Bay of Fundy was not chosen as a Large Ocean Management Area (LOMA) pilot project for implementing ICM in the early 2000s, over 60 integrated management initiatives (e.g., an organization, a research initiative, a management initiative or a body) have been identified by interview participants as being integrated in some way. For example, previous ICM initiatives include the Minas Basin Working Group Community Forums (Upper Bay) and the Marine Advisory Committee (Lower Bay)-previously known as the South Western New Brunswick Marine Resource Planning. The terms Upper Bay and Lower Bay allow for the inclusion of main activities that influence the sustainability of the sub-region. For example, Lower Bay boundaries include the Port of Saint John where there is significant transport activity. The Upper Bay includes Minas Basin as well as Minas Passage due to ongoing tidal energy research and development as well as the presence of valued fisheries throughout the area (e.g., lobster and scallops). As shown in Figure 2, each case is constrained by provincial and national boundaries to focus the scope of the research to remain manageable for data collection and allow for a ‘deep dive’ into local realities.

Figure 2. Sub-regional case study locations within the Bay of Fundy (Map created by S. Eger and R. Caballero for this study in 2020).

The present study used a hybrid analytical approach to analyze interviews for core ICM characteristics (Dubois and Gadde, 2002; Timmermans and Tavory, 2012). A hybrid approach, referred to by some as abductive, offered an alternative to a purely inductive or deductive approach, letting the researcher move between theory and data to develop or modify theory (Dubois and Gadde, 2002; Bryman, 2016). We first adopted the three core ICM characteristics (i.e., formal structures, meaningful inclusion of diverse actor groups, and innovative mechanisms) from Eger et al. (in press) and applied them within a case study approach to gain deep insight into governance issues (Ritchie and Ellis, 2010). This is an appropriate approach for this study as ICM implementation is highly contextual (Cicin-Sain et al., 1998). The use of case studies encouraged contextual nuances to emerge between case studies (Newing, 2010).

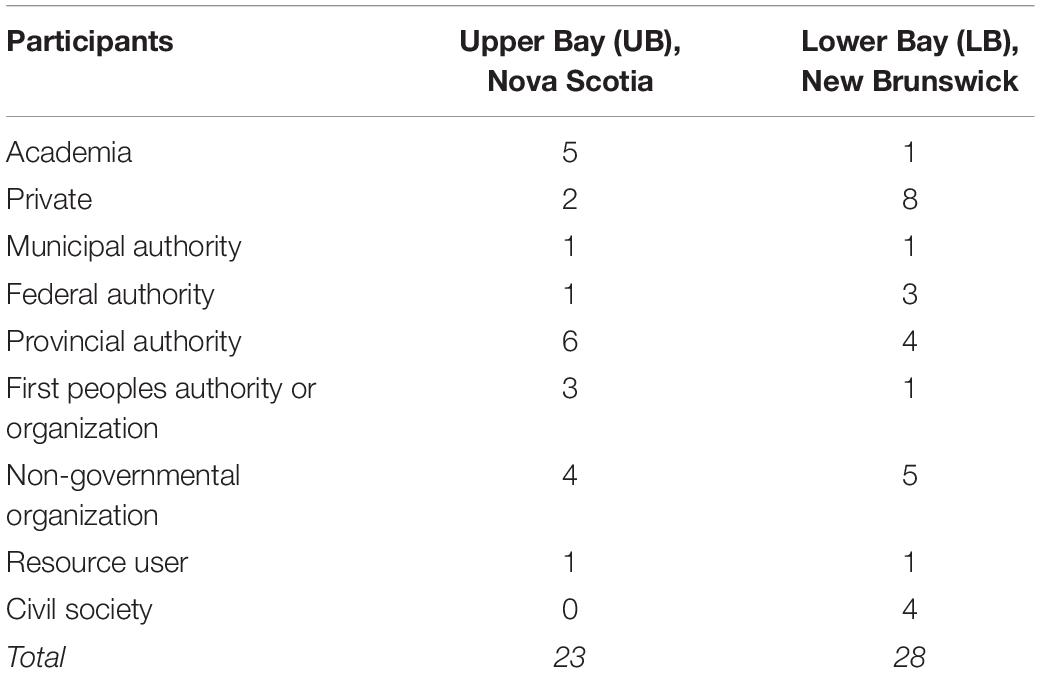

Participants from both Lower Bay (LB) and Upper Bay (UB) were purposively identified to include those who held knowledge of or previous experience with ICM initiatives in either of the embedded case studies. Participants held perspectives from a variety of backgrounds (e.g., academia, government authorities, First Peoples, private sector, non-governmental organizations, and civil society) and were chosen through snowball sampling (Biernacki and Waldorf, 1981). In total, 51 semi-structured interviews were conducted with a variety of participants who have experience with ICM within each case study sub-region (Table 1). Please note that the 51 interviews are from a subsample of an initial regional study of 68 interviews, therefore some participant numbers exceed 51 (Eger and Courtenay, 2021).

Table 1. A summary of participants from two sub-regional case studies within the Bay of Fundy (n = 51).

During the interviews, participants recalled their experiences with ICM and expressed their own views. To understand opportunities for future ICM efforts within each embedded case study, participants were asked questions from a governance lens to elicit experiences with ICM initiatives with a focus on lessons and the future. Examples of questions posed during the interviews included the following: From your perspective, are there any lessons from your experience with ICM? How do these lessons apply to future initiatives? If there was an opportunity to advance ICM in this area, what would you suggest (i.e., what are the next steps)? A complete semi-structured interview protocol and question guide can be found in Eger and Courtenay (2021). Interviews were audio-recorded, treated as confidential, and did not identify participants in the findings.

This study used thematic analysis, a common method to organize and describe data into categories or subthemes (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Saldana, 2015; Yin, 2016), to identify thematic patterns relevant to ICM opportunities in the Bay of Fundy. A full account of each case study relative to opportunities was reported by organizing and re-organizing text passages into sub-themes and themes to determine how the core characteristics related to opportunities within each case study (Yin, 2016). In some cases, participants framed opportunities as next steps or suggested lessons from previous experiences to be considered. For the most part, the codes and sub-themes were not verbalized directly as opportunities. Data analysis required the researcher to read between the lines in order to interpret data relative to various aspects of the research topic, as is customary when using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

The corresponding definitions of each of the identified core ICM characteristics used to analyze interview transcripts were derived from key references from the literature and are presented in Table 2. Coding and analysis of interview transcripts were supported by computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software. Temi1, an online transcription software program, was used to create written transcripts of audio-recorded interviews. Participants were given the opportunity to revise their interview transcripts upon request. The coding process for organizing data and identifying themes and sub-themes from the interviews was also facilitated by QSR NVIVO, a data management software.

Table 2. Code definitions of pre-selected core ICM characteristics applied to individual subregional case studies in Round 1.

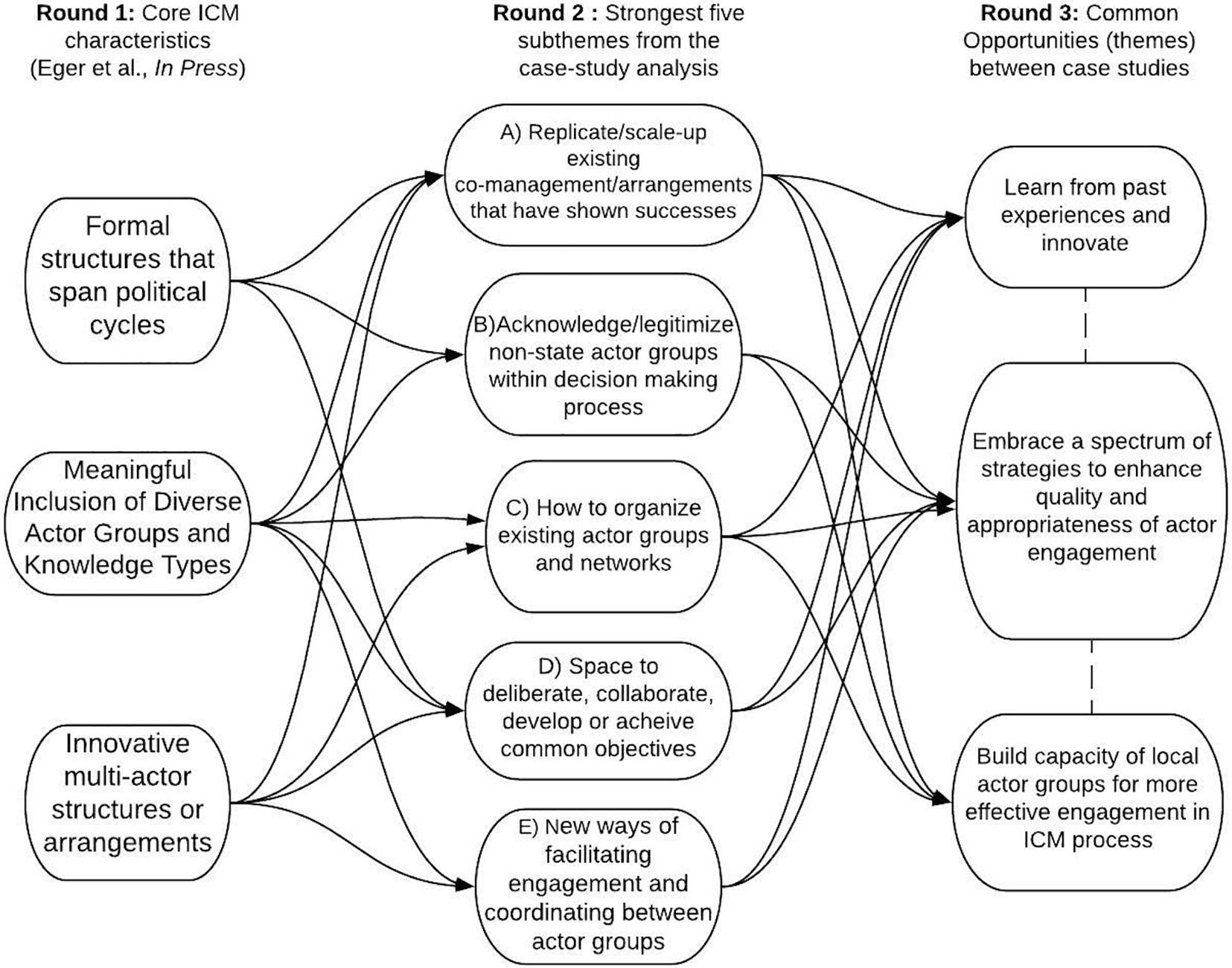

The analytical procedure for coding core ICM characteristics for each of the two sub-regional case studies was based on the three core ICM characteristics described in the previous section. An overview of the results of the multi-round analysis process is illustrated in Figure 3. The resulting opportunities flow from the pre-selected core ICM characteristics (Eger et al., in press) used in the first round of coding.

Figure 3. Overview of analytical processes that leads to common opportunities for ICM in the Bay of Fundy.

Each of the three distinct rounds was analyzed independently (further description of each round of analysis can be found in Supplementary Table 1). Each reorganization of raw data (i.e., text passages from case study interviews) led to fewer outliers as the sub-themes/themes reorganized. Coding stopped once each separate theme threatened to lose independence should another round occur (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Round 1 applied three core ICM characteristics, depicted on the left in Figure 3, deductively to both Upper and Lower Bay case study interview transcripts resulting in relevant text passages coded to each of the three core ICM characteristics. Using thematic analysis, Round 2 then reorganized the text passages from Round 1 further into related categories within each sub-regional case study and ultimately resulted in a list of overarching sub-themes. The most prevalent sub-themes— with the highest frequency of coded text passages—are shown in Figure 3 (middle column) and expanded on in Supplementary Table 2 – to help clarify the coding and analysis process. Finally, Round 3 (Figure 3, right column) compared the sub-themes from each of the case studies in a cross-case analysis to identify thematic patterns (Finfgeld, 2003; Finfgeld-Connett, 2010). This resulted in an amalgamation of sub-themes to yield several distinct opportunities (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Opportunities were determined based on the abundance of participant statements relating to each theme. Opportunities (themes) with the most linkages or connections with subthemes from both case studies, i.e., relevant to both the Lower Bay and the Upper Bay, emerged as final common opportunities. Table 2 explains the three main common opportunities from the analyzes and synthesizes evidence for each.

The interactions between rounds of analysis in Figure 3 demonstrate the connections of raw data between rounds and reflect the interconnectedness of raw data to a broader theme. In other words, the links shown as arrows in Figure 3 between the core ICM characteristics, sub-themes and final themes (opportunities) indicate that participants supported opportunities related to a cluster of themes. However, the connections among core characteristics, subthemes, and themes do not mean that other links were not present; rather, the selections represent the main factors as indicated by frequency of textual responses.

In parallel to interviews, an ad hoc document analysis was conducted by reviewing documents specific to the two case studies as they relate to core ICM characteristics or context-specific variables such as history, past initiatives, actor groups and policy. Document analysis was also used to triangulate interview data with sources to provide depth to the study and confirm validity. Details of documents that contributed to the document analysis can be found in Supplementary Table 3. Multiple dimensions of context including history, capacity, activities, jurisdictions and objectives were compiled to inform a rich understanding of each of the two sub-regional case studies. A review of documents revealed distinct differences within the two subregions, although there were some similarities in terms of socio-cultural context. Supplementary Table 4 summarizes various contextual aspects of each case study to reveal similarities and differences. These details were relevant as interview transcripts were reviewed and text passages were coded and compared throughout the three rounds of analysis.

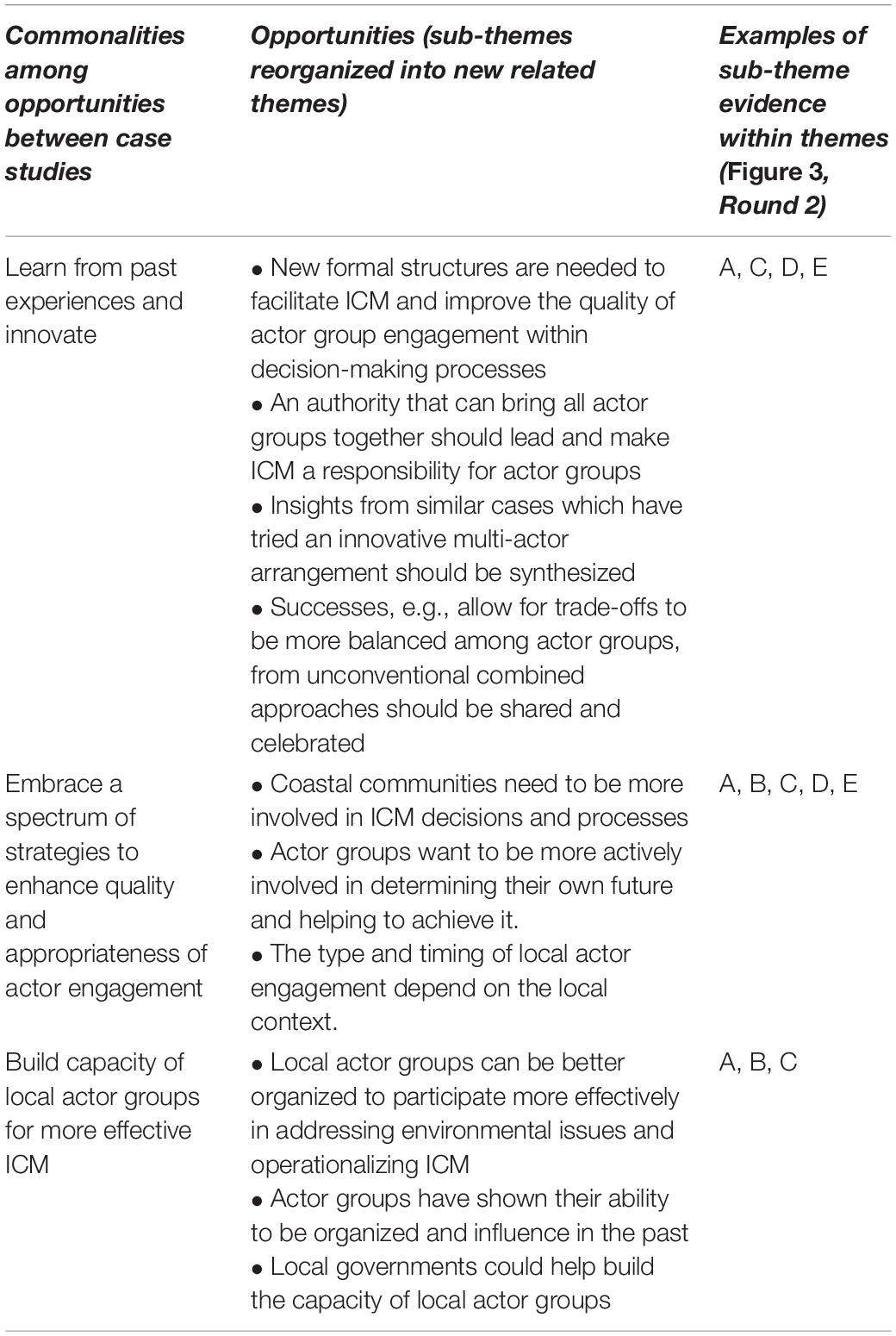

A document review and a multi-round cross-case analysis of the interview results yielded three emergent common opportunities for the Bay of Fundy:

• learn from past experiences and innovate;

• embrace a spectrum of strategies to enhance quality and appropriateness of actor engagement; and,

• build capacity of local actor groups for more effective ICM.

These opportunities suggest that there is a wealth of knowledge and experience relating to ICM that could be more closely integrated into policies and initiatives that support ICM at the regional and sub-regional levels. Table 3 explains the three main common opportunities that emerged from the analysis for achieving the core ICM characteristics in the Bay of Fundy analyses and elaborates using evidence below.

Table 3. Summary of results and their associated sub-themes (Letters from middle column, Figure 3).

Case study participants identified the need for a better understanding of the tools and strategies that have been useful for previously attempted ICM initiatives. In particular, improved knowledge translation and institutional learning will build upon past experiences and avoid learning the same lessons over and over again. Distinct lessons and innovative findings include mechanisms that provide a basis for multiple actor groups to come together. To help ICM initiatives come to fruition, lessons tended to focus on the inclusion of groups with perspectives broader than the prevalent economic or ecological to develop ICM objectives, engage in decision-making, or help with implementation. Enhanced leadership is suggested from both Provincial and Federal governments to implement this opportunity since they have the “authority and ability to pull people together” and there is a well-recognized need to organize ICM processes and decision-making further to be more effective (Upper Bay interviewee #64 or hereafter UB 64). Where leadership from these authorities was missing or not apparent in past initiatives, progress was stalled (e.g., ESSIM). Thus, formal structures (i.e., policy instruments including regulations and legislation) that endure across political cycles (i.e., Canada has a < 4 years electoral timeframe) are important for maintaining the commitment, resources, and capacity needed for ICM progress. For example, several participants from both case studies reflected that unless government authorities make ICM and interactions with local actor groups mandatory for industries (e.g., tidal power, aquaculture, shipping), they will continue to not voluntarily take the responsibility on themselves. In some cases, industry is ‘doing what they can’ but will only do what they are regulated to do (LB 57). For example, the aquaculture industry will remove salmon culture pens that are no longer in use only if required (LB 59). To move toward the improvement of existing learning and knowledge translation mechanisms needed for effective engagement and deliberation, conventional governance systems need to have a stronger role in facilitating them (e.g., formal guidance structures). From the experience of participants in both the Upper and Lower Bay, new combined mechanisms and structures are needed as people are not satisfied with the approaches that have been tried.

LB 53: [Y]ou need to have a strong coordinating, leading entity that will take it forward, and you need that support system; as much as you think it’s going to be ground up, it’s ground up and top-down meeting in the middle.

UB 45: [w]e just don’t have the sustaining integrated management, … nationally or regionally. Each region is basically implementing the Oceans Act in different ways, but shouldn’t we have Natural Resources Canada, DFO, Environment Canada, Parks Canada all at the table nationally and directing what we do and how we work in the regions? And First Nations too?

Participants in both cases incorporated local history in their narratives and mention the need to learn from past experiences in or adjacent to the Bay of Fundy. For example, it was acknowledged by participants in the Lower Bay how different actors are participating in ICM initiatives. Also, participants acknowledged that current systems have not been sufficient for achieving ICM initiatives in an integrated way. There are also previously created tools and resources that give insight into the various actor groups, values and community priorities within the case. In the Upper Bay there is significant potential to build upon previous work such as the community forums led by the Bay of Fundy Ecosystem Partnership – Minas Basin Working Group. This working group held multiple workshops with communities surrounding the Minas Basin to determine what values and priorities local actor groups had for coastal and marine areas (Tekamp, 2003). Participants suggested that updating the outcomes of these efforts and revisiting how to address ongoing priorities in the coastal and marine realm was prudent.

Additionally, participants mentioned innovative partnerships that were emerging to build research and management structures, for example, collaboration between the Marine Institute of Natural and Academic Science (MINAS), Sipekne’katik First Nation (Indian Brook) First Nations, and the Ocean Tracking Network for conducting species monitoring in the Upper Bay. In the Lower Bay, participants recalled the development of the community values criteria (CVC) as a valuable output from the Marine Resource Planning initiative (MRP) that existed from 2004–2009 (Jones and Stephenson, 2019). The CVC was a framework created by the MRP process involving numerous participants to recognize local-scale values and to evaluate proposed activities in the Lower Bay (LB 24). Although CVC criteria were never used as envisioned, participants believed it worthwhile to incorporate the CVC into future decision-making for activities within the sub-region (Parlee and Wiber, 2018). The MRP process subsequently evolved into an advisory body [i.e., the Marine Advisory Council (MAC)] that has since been dissembled (Jones and Stephenson, 2019). Nonetheless, the experiences and lessons from the MAC contributed to the understanding of how different actor groups interact and made progress in determining how to embed community values within coastal and marine decision-making in their area. Although there was a difference between the extent of experience with ICM initiatives in Upper and Lower Bay, both case studies realized that future opportunities should take into consideration past lessons.

One clear finding that relates to having new or more effective ways to deliberate and engage is that many local groups want to have a more meaningful role, in the process, for example at times this would look like a stronger ‘voice’ (i.e., more influence), in ICM decision-making. Each group has different capacities to consider which need to be considered in the way they are approached, engaged, and involved (LB 26). As the current governance regime in the Bay of Fundy generally leaves responsibility and authority to federal and provincial department representatives priorities and interests of the various elected officials continue to drive policy agendas and priorities. Participants called for lessons to balance top–down and bottom–up interactions between authorities and local actor groups. Insights into these combined arrangements have been provided by scholars, practitioners and program evaluators for Canada (Office of the Auditor General, 2005; Hall et al., 2011; Flannery and Cinnéide, 2012). Participants acknowledged that the current model of ‘business as usual’ is not working and that decision-makers have not sufficiently prioritized nor provided sufficient resources to aid progress with ICM.

LB 27: I think going forward, that’s one of the things that we’re going to look for is we need to have that direct involvement with a decision.

UB 11: It became obvious very soon into the process that Force, the government and the corporations that are going to put turbines in the water weren’t really listening. They just wanted us to tell them it was okay. They didn’t care. They’re still not going to change their project depending on what you say. They already have it set in stone.

New approaches do not necessarily mean reinventing the wheel but may instead embrace the idea that there should be critical reflection on previous initiatives, for instance, what was the result and how next time it will go better in the same or different context (Canada’s Ocean Strategy: Our Oceans, Our Future, 2002). Participants identified existing community-based and co-management efforts that have shown success and perhaps could be replicated or scaled up in other areas or for other issues/objectives (Kearney et al., 2007; Parlee and Wiber, 2014). In the Lower Bay, participants referred to the novel co-management of shellfish harvesting with fishermen’s associations, and the desire to try to replicate a similar model for ground fisheries (LB 26) (Wiber et al., 2010). Fishermen’s associations are fairly well established in the Lower Bay with democratic representatives who speak for their actor group (e.g., Grand Manan Fishermen’s Association, Fundy North Fishermen’s Association). In the Upper Bay, participants had experience engaging with or knowing about the Bras d’Or Lakes Collaborative Environmental Planning Initiative (CEPI), even though this is outside the regional scope of the Bay of Fundy. CEPI is an innovative mechanism between the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources, an organization representing five Mi’kmaq Chiefs. CEPI is creating collaborative management plans and addressing environmental management issues around the Bras d’Or Lakes (Naug, 2007). While conventional approaches remain focused on ecological and economic objectives, the use of unconventional approaches in Canada (e.g., CEPI) might allow for more appropriate consideration of social and cultural objectives (LB 44, LB 63).

The plethora of experiences with ICM has included different foci of ‘what is being integrated,’ strongly suggesting there is not a single way to operationalize ICM. Therefore, there is an opportunity to translate these experiences into ICM strategies that are appropriate for different contexts (i.e., histories, capacities, and priorities). The opportunity to embrace a spectrum of ICM can assist and direct practitioners to more effectively select appropriate approaches and strategies within the ICM process that are best suited to different contexts, or sub-regions.

A spectrum of strategies for actor engagement is needed to navigate ICM initiatives. Engagement is considered to include the sharing of perspectives to understand the impacts of decisions on various actor groups ranging from one-way communication to having some authority over decision-making (e.g., consultation, involvement, collaboration, partnerships and empowerment) [International Association for Public Participation (IAP2), 2002]. Participants outlined ways in which decisions are being made for marine activities and priorities across different jurisdictions and geographic scales resulting in undesired or ineffective outcomes at the local scale. Participants from coastal communities acknowledged that the current distribution of power to government authorities at national and provincial scales has made it difficult to consider community values and for community actors to participate effectively (i.e., engage and collaborate with different types of actors) (LB 59). In particular, the fact that communities are not homogenous and have differing worldviews needs to be better addressed by decision- and policy-makers through more thoughtful engagement processes (Kearney et al., 2007). One participant said he believes that rural people have the impression that people in Ottawa, Halifax or Fredericton think they, themselves, are experts and do not try to understand the knowledge locals possess (LB 36).

Further, there is not a strong sense from participants that they could ever have a true impact on decisions (LB 26). One practical approach mentioned by participants is related to ‘stakeholder mapping’ type exercises for process leaders, such as provincial and federal representatives, to do prior to entering a community. This exercise aids in scoping the range of relevant actors and the diverse priorities to avoid forming preconceived notions about what their priorities are (UB 8). Stakeholder mapping is a tool used to scope out different actors, their incentives and their influence relating to a particular problem, and/or geography or interest (LB 10, LB 27). Once relevant actor groups, and ideally their representatives, are identified it is then important that the expectations of each actor group are clear, and that their unique capacity is recognized and supported appropriately. A recent lesson from the Minas Basin tidal energy development was that the consultations with actor groups showed that place and local priorities matter.

UB 43: we’ve been very place focused. [These meetings] held in Parsborro area where we’re based, have not included broader stakeholder concerns across the Bay of Fundy is something that requires more of a geographic spread in our engagement efforts. Everything’s connected…. So we’re definitely trying to focus more on a broader level impact in our engagement strategies than we were in years past.

LB 10: You need to determine at the very outset what is up for debate. To what extent will any consultation influence decisions – your stakeholders should know that. It really frustrates me that there are people with real concerns and livelihoods and traditions and histories of either working on the land or living adjacent to these communities, that I don’t feel is honored and respected through the consultation processes or by government officials. I really think you have to rethink the process of working with local communities when you are exploring things like MSP or integrated coastal management or whatever.

Interviews revealed the desire of participants to be actively involved in determining their own future as well as motivation to participate in achieving it. This means that decision-making processes require transparency so there is a clear understanding of how actor groups can best contribute (e.g., who is responsible, for what, and how) and the degree to which actor groups will contribute to and shape the result (e.g., a decision being made). Participants in both case study areas were able to identify various actor groups with current capacity to help operationalize ICM, and that some groups are more suited and capable of participating than others. Moreover, participants from both case studies were interested in exploring how to increase engagement of the First Peoples in coastal and marine management. In the Lower Bay, the Peskotomuhkati First Peoples (Passamaquoddy) and actor groups from both sides of the Canada- United States border have recently committed to restoring the alewife population on the St. Croix River (DFO, 2018). In the Upper Bay specific recommendations were for MINAS, a local collaboration between fishermen and academia, to work with Sipekne’katik First Nation (Indian Brook) to manage and maintain one of the last traditional fishing weirs in the area (i.e., Bramber Weir).

LB 58: Having that diversity of ownership, for lack of a better term, is part of what made it successful because it gives you windows into a lot of different segments of the population rather than always living within an echo chamber of your own beliefs.

UB 51: It’s just hard with so many different levels of government involved and who actually can make decisions and make it in a timely manner. It definitely has to be an ongoing process and very flexible, but people get really upset and then they can’t see beyond their issue.

Participants’ experiences provided insights into diverse strategies being used within combined approaches and highlighted opportunities for stronger engagement. Both directly and indirectly, participants referred to multi-actor forums that allow for deliberation and facilitate the sharing of different views within a community. An Indigenous participant referenced the relevance to the Bay of Fundy of the Taku River Tlingit First Nation (TRTFN) Case Law in BC that found “On the spectrum of consultation required by the honor of the Crown, the TRTFN was entitled to more than minimum consultation under the circumstances, and to a level of responsiveness to its concerns that can be characterized as accommodation” (Canada, 2004). Other landmark cases in Canada relating to Indigenous title include the R v. Marshall (Canada and Marshall, 1999) case in Nova Scotia regarding a treaty right to fish. Examples of what could be accomplished in these forums with diverse actor groups include determining common objectives and clarifying expected outcomes from both the participation process and the intervention itself (LB 2). Specific between-actor actions could also involve co-visioning or scenario-planning, co-creation of actor engagement plans, collective and strategic long-term planning. Additionally, participants recognized that particular forums could function to (re)build trust between actor groups within or between different activities and direct the groups’ shared incentives and capacity to contribute (i.e., resources, power, staff, mandate). Often within these forums, champions and representatives from different actor groups were identified. Results also indicated that there is a large diversity of what these forums could be because of incentives, motivation, and capacity of actor groups in the sub-region. For example, one participant reflects that engagement strategies for integrated management in the area have ranged from “loose group getting together every few months for pizza” to “you are the decision-making authority”… or “they have to get our piece of paper with our signature” (UB 42). The following quotations from participants indicate that involving local actor groups is rarely a one step process suggesting strategies used should be more than a one-time effort.

LB 64: Let’s come into the room, leave our opinions at the door and listen to one another – [that’s] step one.

UB 65: The key is, is once the decision’s made it doesn’t mean that you stop the engagement process. There’s that ongoing progress that needs to continue to happen otherwise companies and activities never get integrated into communities.

In both the Lower Bay and Upper Bay case studies, the general sentiment was that opportunities for involving diverse actor groups were neither sufficient nor appropriate. Where the two case studies differed was for what the appropriate next steps toward ICM might be. When asked about successful models of participation, participants focused on examples that allowed for communication between actor groups (i.e., two way or back and forth). Further, comments frequently called for formal structures. One participant from a non-governmental organization suggested there should be a requirement to meet minimal standards for engagement at provincial and/or national levels, “if you don’t listen to people, you’re not likely to be successful” (UB 49). Another individual mentioned the value of fishermen liaisons from the communities in the Lower Bay who reported directly to (then Minister of Fisheries and Oceans) Romeo Leblanc to connect decisions he was making to “the place and the people” (LB 62). Despite extensive ICM experiences, participants in the Lower Bay shared that they were tired and jaded from spending volunteer time in a process that did not achieve desired outcomes likely due to ineffective engagement.

LB 27: There are a lot of community-minded people who are open to a lot of things who would like the opportunity to deliberate. This is what is lacking in a consultation is that there is no time to deliberate.

In contrast, the Upper Bay had less extensive experience and participants showed an enhanced willingness to proactively participate to help shape multiple and integrated objectives for the region, particularly with the development of renewable energy and intensive fishing efforts. One participant reflects that currently, they are being excluded and that local actors have valuable perspectives to share.

UB 58: The idea of shutting out opposing viewpoints just because they can be intimidating or offer a differing opinion isn’t what governance and leadership is about. Listening to those people, oftentimes giving them a platform, but understanding that it’s part of the dialogue.

Participants also identified other models that are headed in the right direction such as the Striped Bass Association which is a partnership between academia and community-based groups (UB 19). Many participants had positive comments on the intention of previous innovative mechanisms to enhance actor engagement [e.g., the Regional Committee on Coastal and Oceans Management (RCCOM) and the Eastern Scotian Shelf Integrated Management (ESSIM) Stakeholder advisory committee]. With regards to ESSIM, comments surrounded the flow of information back and forth across different levels which allowed for many relationships to be built (UB 42). As with the RCCOM, some comments pointed to the need to explore a high-level formal structure (e.g., agreement or commission) to span government mandates, keep provinces accountable, and provide a high-level structure for oceans management in Canada over the course of multiple political cycles (e.g., European Commission) (UB 45). Although the idea to develop local ICM spaces or forums was supported by many participants, one participant acknowledged that these groups will likely continue to lack authority and that it is important to recognize the different streams of government (i.e., both elected representatives and the civil service). Successful ICM in the Bay of Fundy requires high-level commitment, from those who hold legal authority within the coastal and marine realm which include the Federal government, the two Provincial governments (i.e., New Brunswick and Nova Scotia), and First People groups (LB 4).

LB 38: It starts with the willingness to give up some power and authority from the center…. it’s got to be rooted in community.

UB 45: It just seems like issues ebb and flow and we just don’t have the sustaining integrated management or MSP, whatever you want to call it, a national or regional structure. We don’t have that here.

Although the above points were generally supported by participants from both case studies, there were clear differences between the Upper and Lower Bay regions in participant attitudes toward ICM. In the Lower Bay, there was an impression of defeat and lack of motivation from those who had been involved in previous multi-actor group efforts because expectations had not been met in the past (e.g., Southwestern New Brunswick Marine Advisory Committee). As a result, there were many recommendations for smaller, tangible efforts that remained reactive to current issues. Pursuing specific, actionable objectives is a better way to bring different actor groups together moving forward (LB 4). One participant spoke about building trust among actor groups by tackling ‘low hanging fruit’ before preparing to take on more complex issues such as truly integrated programs (LB 32). Some success was seen with marine debris initiatives because it was an issue “common to all stakeholders” (LB 33). In other words, the usual suspects (i.e., engaged representatives of various actor groups) would need to rally around a specific problem [i.e., marine debris, protection of the endangered North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis), or spatial protection] or a defined purpose. Who you bring around the table is dependent on the objective (LB 26). Participants from the Upper Bay were more optimistic and open to coming together to deal with large, interconnected issues. Suggestions to support future ICM efforts included scenarios or visioning workshops with multiple actor groups on topics of concern to ICM, methods to more effectively integrate First Peoples, and proactive efforts. Participants from both case studies alluded to the idea of ‘a one-stop shop’ with representatives from local actor groups in a single place to provide knowledge and advice such as context-specific data for government authorities, industries, and decision-makers that could impact their communities.

Capacity needs to be built into community actor groups to participate in operationalizing ICM and addressing environmental issues. Participants from local actor groups recognized the need to become more organized as a group. Participants from government in particular suggested that it is beneficial to their programs and processes when actor groups are already organized. The ability to organize was connected to three components listed by participants relating to capacity: local development (LB 62), financial support (UB 22) and education/knowledge (UB 43). Within both case study regions, a fundamental opportunity emerged around strengthening the ability for actor groups to be involved in ICM. Specifically, achieving a democratic representation of actor groups was a prominent theme. Participants from government authorities expressed that having democratic processes for selecting representatives within actor groups enhances the legitimacy of the actor group and thus the recognition by government agencies. In the case of NGOs and industry, these representatives were often full-time staff members. In other actor groups such as tourism, small-scale livelihoods, and engaged citizens, representatives were likely to be volunteers and unlikely to have been selected through any particular process.

As it currently stands, participants suggested that enhanced representation was needed within their actor groups. Currently, many actor groups involved a vocal minority being led by individuals with strong personalities, rather than people who truly represented the group (UB 68). Another example of misrepresentation was when members were assumed to be representative of their group (e.g., tokenism) which has happened frequently with Indigenous consultation. A participant who fishes and identifies as Indigenous was mislabeled as a representative or leader. He exclaims “I don’t speak for my band” (UB 19). Further, a participant that works with, and for, First Peoples expressed that “the consultants don’t work for us” and that it is a current limitation of the system that avoids effective engagement of the actor group (UB 22).

Enhanced representation of actor groups was frequently brought up in both case studies as a concept that would assist in ensuring effective consideration of priorities, values and objectives.

UB 68: The success stories are those that have representation.

According to a participant from the Lower Bay, actor groups should organize and have effective representation in order to build capacity.

LB 62: Communities have been marginalized and need to build capacity to govern themselves before engaging. It is important to be able to know how to organize and mobilize once there is something to work toward… A key element here that needs to be put in place and that is we have no institutional capacity or resources to help build capacity in communities and organizations. To be able to fully engage around these things, to be able to play a meaningful role in shaping your destiny as a community, you need to have the sort of human capacity to do that. the issue of capacity, to organize effectively is the biggest stumbling block of all.

Both case studies have actor groups who have shown they are capable of organizing, leading, engaging and influencing various activities and processes within coastal and marine systems. Between case studies, however, actor groups may have different motivations and abilities to influence or catalyze change. In the Upper Bay, there is evidence of the strength and influence of local communities who opposed the process, not necessarily the objective, of tidal energy development in Minas Basin and Minas Passage. Active engagement of one group in particular, the Upper Bay Fishermen’s Association, resulted in a delay of tidal energy development progress for almost a year (Maclean, 2017). In the Lower Bay, actor groups have also shown their interest in leading change in their community. The motivation of some individuals and groups from the Lower Bay, many of whom were volunteers, was sustained through their continued participation in the Marine Advisory Committee for 10 years or more.

Several government participants felt that some actions by actor groups disrespected or undermined processes that had been laid out for local engagement. An elected official recounted that there are always groups that avoid the formal processes in place and who directly lobby the Minister, undermining the process, while other actor groups are trying to engage/influence through the allocated channels (UB 22).

LB 5: Some fishermen have tremendous influence on the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. But, there are other fishing groups that have zero [influence] and are treated very badly. Clam fishermen is one of those groups.

UB 10: And that’s exactly what happened with the fishing community. Their [Fundy Fishermen’s Association] power to influence was, you know, underestimated and they just thought they could have them go to a few meetings to see and just hear what they had to say. There wasn’t as much [access] as they needed for an emotional [support] or irrational or whatever. That’s perhaps why they chose such a radical way to influence this whole process. And they were able to.

In both case studies, an enhanced role of local or municipal governments was proposed by interviewees to facilitate or lead local development and capacity building. The general sentiment from participants was that “leaders need to understand the perspectives of the community” (LB 60) and that municipal governments could carry out and connect local values to higher-level priorities (UB 45). One participant stated that when an individual from the municipal government was in a leadership role it was easier to support them (LB 63). Participants commented on a multitude of roles that municipal governments could take on including having a larger, more defined role in implementing coastal and marine planning. This may require the decentralization of some Provincial, or even, Federal authority/responsibility to a more localized level. One participant suggests to ‘move DFO out of Ottawa’ as more localized governance, as seen with municipal land use planning, would be more appropriate to create long-term development plans that satisfy local, including Indigenous, Provincial and National objectives (UB 56). Another possibility would be for municipal governments to play a brokering role between actor groups at the local/sub-regional level by creating spaces that allow for a diverse set of views to be heard and common objectives to emerge between actor groups at the local level (UB 19, LB 62). Municipal governments could also educate local actor groups on the decision-making system within which they are embedded (UB 43). Lastly, the development of rural economies is seen to help strengthen the independence and autonomy of local actor groups over local decisions (UB 65).

UB 22: There’s a lack of capacity in communities for addressing environmental issues. There’s no funding support, there’s nobody to enforce it. There’s nothing to enforce here in Nova Scotia unless they’re actually implemented by the community, but they don’t have the capacity to even undertake the work to identify the areas, let alone implement bylaws and then enforce them…if we continue at this rate, Nova Scotia is going to be drained and then we’re, you know, we’re going to be the ones holding the bag for those seven generations who have nothing.

LB 22: So that’s where that body [one stop shop] can be really powerful so you do reach consensus on things you would never get on the bilateral stuff between Fredericton and the individual stakeholders. So you get the body to say, you know, this is what we think about this… when that body speaks as one and says to the Minister, there were fisherman and aquaculture and “we all think this about that.” Then the Minister needs to reflect what they are asking.

These instances outline potential roles that municipal governments could play in moving toward ICM through the organization of local actor groups while maintaining connections with broader coastal and marine objectives (UB 69).

This paper sought to synthesize past experiences of participants in ICM through interviews and embedded case studies within the Upper and Lower Bay of Fundy. Using core ICM characteristics identified from Eger et al. (in press), data analysis uncovered three opportunities for the Bay of Fundy region, common to both the Upper and Lower Bay sub-regions. The results of this study support the inclusion of both state and non-state actors across scales. A main finding of this study indicates that the form of participation of these groups is a critical element in ICM given that all the opportunities that emerged from the analysis, all have implications for participation.

As seen in Figure 3, subsequent analysis of the interviews from each case study relative to the core characteristics of ICM conceptual framing revealed similar opportunities. Therefore, policy recommendations are made in the following section at the regional level and focus on the importance of being able to tailor and accommodate unique contexts within each sub-region. The commonalities between case studies may be due to overlapping aspects of context seen in Supplementary Table 4 such as history with integrated initiatives, development activities, cultural preferences and similar population characteristics (i.e., rural, First Peoples). The following insights for future ICM efforts are elaborated below:

• improved formal structures are required to avoid making the same mistakes;

• a spectrum of approaches will support meaningful engagement in ICM;

• local capacity is needed for effective innovative mechanisms; and,

• policy measures are recommended.

The main opportunity to achieve formal structures that span political cycles was to learn from past experiences and innovate (Eger and Courtenay, 2021). The present study found that many lessons have been learned over the years and iterative policy updates are crucial for avoiding past pitfalls. Despite interest in combined approaches, planning and decisions for coastal and marine systems continue to be made in a predominantly top–down way at national and regional scales. Essentially, the lessons identified in this paper aren’t being institutionalized for ICM. Given this reality, learning from the past and having it inform how to move forward is especially important at regional and sub-regional scales.

These lessons should, in turn, be adapted into and reflected through current governance regimes (i.e., formal structures and processes). Some notable lessons for the Bay of Fundy can be derived from previous ICM initiatives in Atlantic Canada such as the CoastalCURA partnership, South Western New Brunswick Marine Advisory Committee, Eastern Scotian Shelf Integrated Management, and Bras d’ Ors Watershed Collaborative Environmental Planning Initiative (CEPI) (Naug, 2007; Parlee and Wiber, 2018; Jones and Stephenson, 2019). Conversations continue to emerge surrounding community-based and multi-stakeholder approaches to environmental management to overcome the inefficiencies of central government efforts in the Bay of Fundy beginning before the Oceans Act and which have continued until the present day (Kearney et al., 2007; Wiber et al., 2010). In Canada, the development of structures to support the evolution of active participation of non-state actors in ICM has not occurred on a broad scale and there remains a need to explore alternative shared-governance models and enhance collaborative ICM processes (Heemskerk, 2001; Office of the Auditor General, 2005; Jessen, 2011; Eger and Courtenay, 2021). This exploratory process can also be aided by documented experiences with ICM initiatives elsewhere in Canada (e.g., PNCIMA, Beaufort Sea) as well as from other nations (e.g., Australia, China, United States) (Hildebrand and Norrena, 1992; Chircop and Hildebrand, 2006; Jessen, 2011; McCann et al., 2017).

To gain the meaningful inclusion of diverse actor groups and knowledge types, a spectrum of participation strategies must be embraced, especially by ICM process leaders, to meaningfully engage all relevant actor groups within and between sub-regions given their various capacities, histories, and objectives. This idea of participation as a continuum has long been recognized in literature through numerous typologies (Gustavsson et al., 2014), ladders (Twomey and O’Mahony, 2019), and essential ingredients (Senecah, 2004; Pomeroy and Douvere, 2008). So, why is not it being used in practice? Authorities in the Bay of Fundy could benefit by expanding their understanding of actor participation (i.e., consultation, involvement, partnerships, and empowerment) by including why certain actors might be involved, how much influence would actors have on the decision, what type of methods are appropriate, when will engagements taken place and how frequently into determining a relevant, context-specific strategy (Morf et al., 2019).

Empowering local actor groups to understand how they can best participate in ICM processes should be a key focus to ensure local interests are accounted for in the Bay of Fundy. As an example, more appropriate engagement could be achieved through the creation of a provincial policy or engagement strategy (in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) to recognize a spectrum of options through guidance and tools such as scenario planning or development (Glaser and Glaeser, 2014). Furthermore, stakeholder mapping and analysis can help understand the capacity and influence of actor groups and ensure participation mechanisms are appropriate for the scale, context and actor group (Hall et al., 2011; Cvitanovic et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2017). Local actors play a role in determining how they should be involved (Buanes et al., 2005; Flannery and Cinnéide, 2012). Given the experiences in the Bay of Fundy, the leaders or ‘initiators’ of the ICM initiative, along with the local actor groups, should jointly determine what type of interaction is “necessary, appropriate and desirable” (Rockmann et al., 2015, p. 161), for example through strategic co-creation of engagement plans (Ritchie and Ellis, 2010; Cvitanovic et al., 2016).

Another opportunity in the Bay of Fundy is to build local capacity of local actor groups for more effective participation in ICM processes. Empowering and building capacity for bottom–up approaches is important because actor groups need to be organized and to have a forum where they can determine how they want, and are able, to participate (Jentoft and Chuenpagdee, 2009; Wever et al., 2012; Brandes and O’Riordan, 2014; Fudge, 2018). Similarly, the creation of innovative mechanisms such as multi-actor structures are likely to be better suited to sub-regional actor groups when the groups themselves can leverage their skills and expertise effectively. Actors, forums and arrangements in the Bay of Fundy varied between sub-regions. Additionally, local actor groups might benefit from an improved understanding of the decision-making system (e.g., legal conditions, processes in place to provide feedback) to legitimize group organization (i.e., representation) and to learn how to participate in policy discussions more effectively (Underdal, 1990; O’Boyle and Jamieson, 2006; Flannery and Cinnéide, 2012; Buchan and Yates, 2019).

Innovative mechanisms have the potential to help amplify voices of marginalized or underrepresented groups and might include new coastal partnerships or inter-industry-bodies, merging agencies together or creating super-agencies. Mechanisms that support the inclusion of non-government actors are becoming more common and are currently needed in the Bay of Fundy (Eger and Courtenay, 2021). To guide local authorities to deal with “complex issues in an integrated manner” local capacity must be built, responsibilities must be clarified, and democracy within ICM processes should be enhanced (Shipman and Stojanovic, 2007, p. 381). Overcoming these obstacles requires that legislation be created for local governments to establish legally constituted partnerships (e.g., joint steering committees with local and national governments) as well as to better align policies to support overarching approaches being used throughout of Fundy. As with combined approaches, institutional innovations and sustained leadership are also required within the Bay of Fundy to enhance capacity for integrated governance at the national level to support initiatives at local and regional levels (Charles, 2010; Lockwood et al., 2010; Eger and Courtenay, 2021).

In Canada, there is renewed interest in achieving ICM through MSP. This study investigated whether unique opportunities exist for ICM in the Bay of Fundy using an embedded sub-regional case study analysis. A synthesis of local experiences revealed opportunities to strengthen top–down structures and processes while also building bottom–up capacity to ensure ICM is grounded within local contexts. Figure 4 depicts policy implications including concrete policy suggestions for the Bay of Fundy, implement policy suggestions/considerations in parallel, and provide a basis for critical examination of ICM across other scales.

The main insights of this paper relate to core ICM characteristics (inner circle of Figure 4):

1. Formal structures that span political cycles

2. Meaningful inclusion of diverse actor groups and knowledge

3. Innovative multi-actor structures or arrangements

The second inner ring shows the lessons from past ICM experiences and combined approaches need to be updated within existing policy instruments. Most importantly:

• Learn from past experiences and innovate

• Embrace a spectrum of strategies to enhance quality and appropriateness of actor engagement

• Build capacity of local actor groups for more effective ICM

Next, meaningful inclusion of actors requires consideration of context-specific details that differ between actor groups within the Bay of Fundy (e.g., capacity, history, objectives). Last, capacity of actor groups should be enhanced so they can effectively participate in appropriate, innovative mechanisms for deliberation and implement future integrated management efforts. Opportunities to achieve core ICM characteristics are shaped by the history, capacity, motivation/incentives, and objectives of the sub-regions. Although opportunities for ICM policy measures in the Bay of Fundy are identified at the regional scale, policies that are founded or incorporate the differences at the sub-regional level should be prioritized.

The outer ring of Figure 4 ultimately leads to examples of policy recommendations that were raised by participants. These illustrative examples provide concrete and practical paths for the achievement of each common opportunity identified in this study within the Bay of Fundy context. Specifically, these actions would help facilitate an appropriate balance between government and non-state actor groups in ICM:

• Update Federal Policy statements to incorporate lessons

◦ E.g., Revise the Oceans Strategy to include lessons from previous experiences

• Strengthen commitment to ICM in federal law

◦ E.g., Through the Federal Oceans Act or Federal Aquaculture Act

• Create a provincial engagement strategy to enhance engagement of local actor groups

◦ E.g., Engagement guidelines or standards for activities in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick

• Enhance role of municipal governments to support the building of local capacity and engagement of local actors in ICM

◦ E.g., Amend Municipality Acts (Provincial legislation) in both Nova Scotia and New Brunswick

Implementing the recommended policy insights should facilitate ICM progress in the Bay of Fundy, as well as assist in other regions, by more closely considering appropriate governance dimensions. The suggested policy instruments from the outer ring of Figure 4 would likely benefit from being implemented simultaneously. Core characteristics, as well as the opportunities to achieve them, are significantly interconnected and, in some cases, can facilitate or even depend on each other. For example, adopting a Provincial engagement strategy could help facilitate the meaningful inclusion of diverse actors and knowledge types as well as help ensure early and ongoing engagement. In this way, connections between opportunities and core characteristics overlap as well as within the characteristics themselves as a result of contextual factors (Figure 3). Additionally, this example illustrates that stregnthened formal structures can direct legal authorities to more clearly support core ICM characteristics and ensure efforts for ICM continue beyond one political cycle.

Formal structures can also help local actor groups receive the opportunity to participate in a way that is meaningful and appropriate to their unique context. Additionally, other formal policy measures that serve to increase the capacity or organization, and thus legitimacy of their groups to authorities, to participate meaningfully might be linked to achieving democratic representation and identifying common objectives. It should not be assumed that an actor group in one sub-region will have the same capacity in another. These policy instruments have implications for continued knowledge sharing and institutional learning from past failures and successes to optimize positive and desired outcomes from ICM processes.

Given the findings of this study, some apprehension arises in light of the international scale at which some ICM initiatives are being pursued with the potential to be misaligned with local capacity. Specifically, a number of internationally led ICM initiatives presently being implemented are often operating at a scale much beyond the sub-regional setting argued in this paper. Recent examples include the UNESCO MSP Global program (UNESCO, 2020), Blue Economy, European Union Maritime Spatial Planning, US Ocean Planning, that often create high-level objectives or planning principles that may not fit with local capacity, pressures and opportunities.

This trend of international objectives impacting national and regional initiatives may not focus sufficiently on the untapped potential of the local-regional scale. This is seen through international conservation efforts and agreements such as CBD Aichi Target 11 that has elicited the prioritization of conservation objectives through MPA networks (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2013). In Canada, this has resulted in federal agencies committing to:

By 2020, at least 17 percent of terrestrial areas and inland water, and 10 percent of marine and coastal areas, are conserved through networks of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures (Government of Canada, 2011).