- 1Department of Marine Science and Convergence Technology, Hanyang University, Ansan, South Korea

- 2Marine Environment Research Division, National Institute of Fisheries Science, Busan, South Korea

- 3Deep-Sea and Seabed Mineral Resources Research Center, KIOST, Busan, South Korea

- 4Ochang Center, Korea Basic Science Institute, Cheongju, South Korea

The expansion of the aquaculture industry has resulted in accumulation of phosphorus (P)-rich organic matter via uneaten fish feed. To elucidate the impact of fish farming on P dynamics, P speciation, and benthic P release along with partitioning of organic carbon (Corg) mineralization coupled to sulfate reduction (SR) and iron reduction (FeR) were investigated in the sediments from Jinju Bay, off the southern coast of South Korea, in July 2013. SR in the farm sediment was 6.9-fold higher than the control sediment, and depth-integrated (0–10 cm) concentrations of NH4+, PO43–, and H2S in pore water of the farm sediment were 2.2-, 3.3-, and 7.4-fold higher than that in control sediment, respectively. High biogenic-P that comprised 28% of total P directly reflected the impact of P-rich fish feed, which ultimately enhanced the bioavailability (58% of total P) of P in the surface sediment of the farm site. In the farm sediment where SR dominated Corg mineralization, H2S oxidation coupled to the reduction of FeOOH stimulated release of P bound to iron oxide, which resulted in high regeneration efficiency (85%) of P in farm sediments. Enhanced P desorption from FeOOH was responsible for the increase in authigenic-P and benthic P flux. Authigenic-P comprised 33% of total P, and benthic P flux to the overlying water column accounted for approximately 800% of the P required for primary production. Consequently, excessive benthic P release resulting directly from oversupply of P-rich fish feed was a significant internal source of P for the water column, and may induce undesirable eutrophication and harmful algal blooms in shallow coastal ecosystems.

Introduction

Phosphorus (P) is a key nutrient, not only regulating primary production as a limiting nutrient in aquatic ecosystems, but also inducing eutrophication that can stimulate undesirable algal blooms in coastal ecosystems (Tyrrell, 1999; Diaz and Rosenberg, 2008; Middelburg and Levin, 2009; Lomnitz et al., 2016). In shallow coastal ecosystems, sediment serves either as a source (i.e., regeneration and release) or a sink (i.e., adsorption and precipitation) of P for the water column (Slomp, 2011; Kraal et al., 2015; An et al., 2019). P dynamics in coastal sediments are tightly coupled to the rate and partitioning of Corg mineralization and the resulting interaction between iron and sulfur (Rozan et al., 2002; Canfield et al., 2005; Kraal et al., 2013; Slomp et al., 2013; Andrieux-Loyer et al., 2014; An et al., 2019). P release from sediments into pore water first proceeds from Corg mineralization, relying on various terminal electron–accepting processes, such as aerobic respiration, denitrification, and reduction of Mn and Fe oxides and sulfate (Canfield et al., 2005; Holmer et al., 2005). In particular, under organic-rich and sulfidic conditions in which sulfate reduction dominates Corg mineralization, abiotic reduction (i.e., reductive dissolution) of Fe oxides coupled with H2S oxidation to form Fe sulfide minerals can intensify P desorption from Fe oxides (Supplementary Table 1). Because the interaction of P with Fe and S has a profound impact on P dynamics in anoxic sediment (Rozan et al., 2002; An et al., 2019), quantification of the relative significance of SR and FeR, which regulate the availability of Fe to react with the P, is particularly important to better understand the P dynamics in coastal sediments.

World aquaculture production has grown rapidly since the late 1980s. It accounted for 47% of total fish production in 2016, while capture-fishery production has remained relatively stable (FAO, 2018). Despite its economic importance, irresponsible aquaculture activities have led to massive accumulations of organic matter induced by uneaten fish feed and fecal production in coastal sediments (Hall et al., 1990; Holby and Hall, 1991; Holmer et al., 2002, 2003; Husa et al., 2014). This has generated various environmental issues including accumulation of chemically reactive and toxic H2S and regeneration of reduced inorganic nitrogen (NH4+) and phosphate (PO43–) in the sediment (Holmer et al., 2005; Hyun et al., 2013; Choi et al., 2018, 2020). The release of inorganic nutrients into the water column may result in changes in composition and diversity of macroalgae, eutrophication, and (harmful) algal blooms in coastal ecosystems (Holmer et al., 2008; Price et al., 2015; Ferrera et al., 2016; Stigebrandt and Andersson, 2020).

Given the overall economic and environmental significance of the aquaculture industry, relevant proxies for assessing the condition of fish-farm sediment are required (Ministery of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF), 2016; Choi et al., 2020). P enrichment of sediment has been recognized as a useful indicator for assessing the environmental impact of fish farms that make use of large amounts of feed (Holmer and Frederiksen, 2007; David et al., 2009), as natural variation of P in sediment is small compared with that of C and N (Soto and Norambuena, 2004). In particular, biogenic apatite P (Bio-P) has been proposed to be an important representative indicator of the impact of fish farming (Matijević et al., 2008). On the other hand, it is also speculated that the precipitation of authigenic-P (Aut-P) could be stimulated during the enhanced deposition and mineralization of Corg and subsequent P release in farm sediment as it was reported in various anoxic sediments with high organic matter loading (Anschutz et al., 2007; Goldhammer et al., 2010; Tsandev et al., 2012; Joshi et al., 2015; Kraal et al., 2017). Most studies that assess aquaculture impact associated with P evaluated total P and major P forms (Kassila et al., 2001; Matijević et al., 2008; David et al., 2009; Jia et al., 2015; Morata et al., 2015). Although several papers have suggested that sulfide accumulation enhances benthic P release in sediment affected by aquaculture (Heijs et al., 2000; Holmer et al., 2002, 2003; Nielsen et al., 2003; Holmer and Frederiksen, 2007), any comparative biogeochemical process studies on P dynamics accompanied by direct estimation of the rates and partitioning of FeR and SR have not been conducted in coastal ecosystems (Valdemarsen et al., 2012; An et al., 2019), especially in fish farm sediments where high P-containing fish feed would have significant impacts on P dynamics in sediments. The objectives of this article are: (1) to present the impact of fish farming on P enrichment and speciation in sediment, with special emphasis on biogenic-P and authigenic-P, (2) to elucidate P dynamics (i.e., adsorption and desorption) related to variation in Fe and S cycles associated with FeR and SR, the two major Corg mineralization pathways in coastal sediments, and (3) to evaluate the potential significance of farming-induced benthic P release as an internal source of P that can stimulate (harmful) algal blooms in shallow coastal ecosystems via benthic-pelagic coupling.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

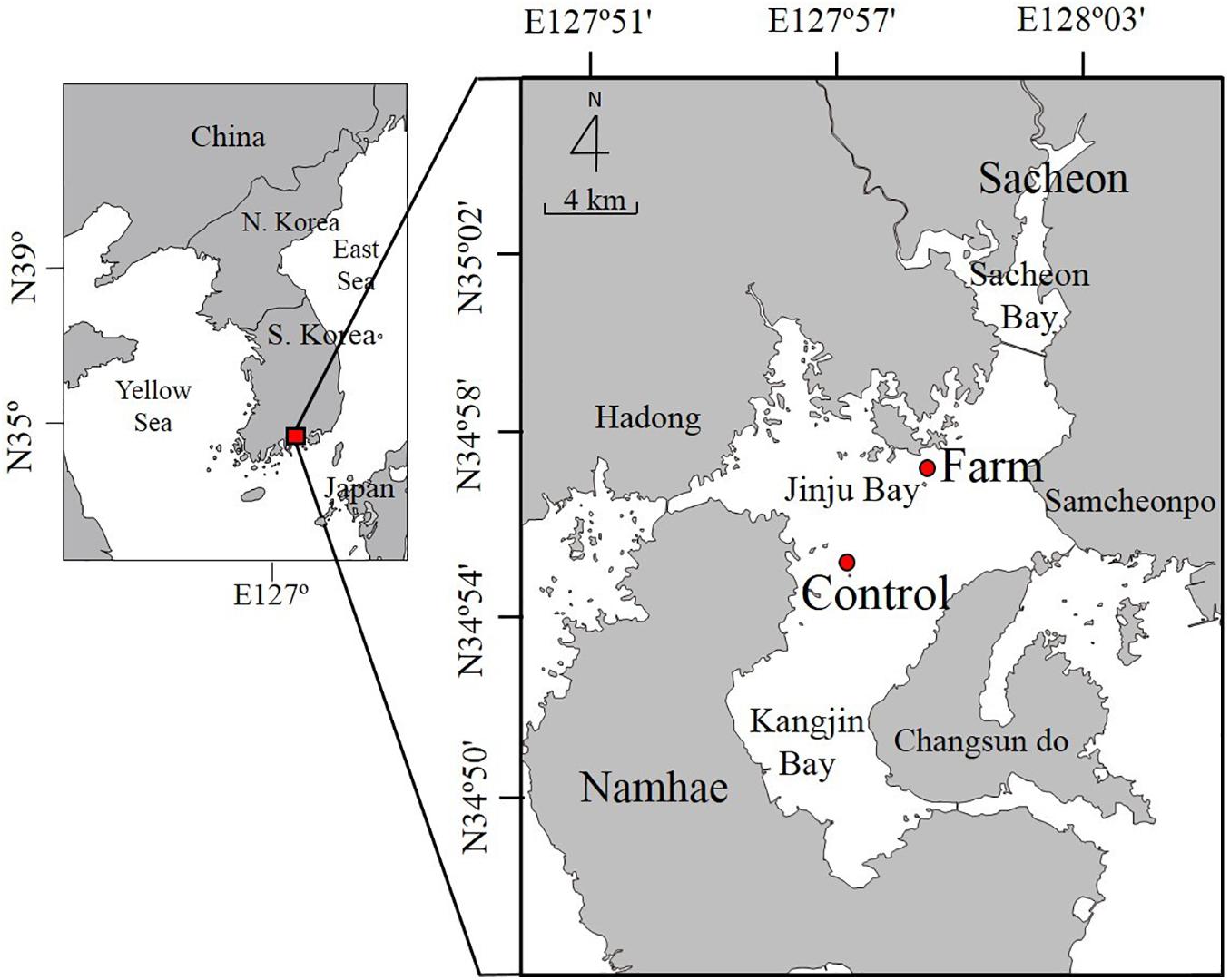

The study area was located in semi-enclosed Jinju Bay near Sacheon and Namhae Island on the southern coast of South Korea (34°55′–34°57′N, 127°57′–127°59′E) (Figure 1). Fish farming activities have been ongoing for several years in which most fish were harvested in November (fall), and re-stocking of empty cages with fry took place in the following March to May (spring) (Choi et al., 2020). Sampling was conducted in July 2013 at a farm site (34°57′08″N, 127°59′07″E) where sea bass (Lateolabrax japonicus), gray mullet (Mugil cephalus), and black porgy (Acanthopagrus schlegelii) were intensively cultivated. Annual fish production in the farming zone with an area of 1,323 m2 was approximately 445 tons in 2013. Fish feed, consisting of a mix of trash fish and extruded pellets (EP), was continuously supplied in accordance with the growth stage of the fish (Choi et al., 2020). In July 2013, only EP was used, and the input of EP at the fish farm was approximately 1.2 kg m––2 d––1. The EP used in the farming zone contain protein, fat, calcium, phosphorus, etc. Among other ingredients, the P content in fish feed varies depending on the growth stage of fish and can be up to 1.5--2.7% (NIFS)1. In order to evaluate the impact of fish farming on P dynamics in farm sediment, a control site (34°55′08″N, 127°57′09″E) was selected in the center of the bay, 4.5 km away from the farm site. Although current speed ranging from 28 to 33 cm s–1 in the study area (Ro et al., 2007) was fairly high enough to reduce the accumulation of sinking organic particles onto the sediment, sedimentation flux of particulate material at the farm (126.2 g m–2 d–1) was almost two-fold higher than that of the control site (77.7 g m–2 d–1) (NIFS, 2013). Accordingly, the density of infaunal polychaetes at the farm site (about 2,500 inds. m–2) was 25-fold higher than at the control site (about 100 inds. m–2).

Figure 1. A map showing study sites at the fish farm and control site in Jinju Bay on the southern coast of South Korea. Solid line indicates Sacheon Bridge.

Sampling and Handling

To minimize surface sediment disturbance, sediment samples were collected by SCUBA divers using acryl cores (40 cm in diameter, 40 cm in length). At both farm and control sites, approximately 30 sediment cores were collected to analyze the geochemical properties of pore water and sediments and to measure microbial metabolic activities such as the rate of sulfate reduction, iron reduction and total anaerobic organic carbon mineralization. On the vessel, triplicate sub-samples for geochemical analysis were collected using acryl cores (6.5 cm in diameter, 25 cm in length).

Sediment temperature was measured using an electronic thermometer (Multi thermometer, DT400, Summit) within a depth of 10 cm. The sediment cores for analysis of geochemical constituents in pore water were transferred to N2-filled glove bags, in which the sediment was sectioned and loaded into polypropylene centrifuge tubes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States). The tubes were tightly capped and centrifuged for 10 min at 3,500 rpm. After reintroduction to the N2-filled glove bag, pore water was sampled to measure NH4+, PO43–, Fe2+, SO42–, and H2S and filtered through cellulose acetate syringe filters (0.2-μm pore size, ADVANTEC, Toyo Roshi Kaisha, Ltd., Japan). The samples for determination of NH4+ were stored at 4°C after adding HgCl2 (125 mM). The samples for PO43– were frozen at −25°C until analysis. The samples for Fe2+ and SO42– were frozen at −25°C after adding HCl (0.1 M final concentration). The pore water samples for H2S and sediment samples for acid volatile sulfides (AVS = H2S + FeS), chromium reducible sulfur (CRS = FeS2 + S0) and elemental sulfur (S0) were fixed in a zinc acetate dehydrate (20% w/v) solution and frozen at −25°C until analysis. Sediment samples for analysis of solid-phase iron, chlorophyll-a (Chl a), total organic carbon (TOC), and total nitrogen (TN) were frozen at −25°C until analysis.

In situ water temperature and salinity were measured using a CTD meter (19 plus; Sea-Bird Electronics, Bellevue, WA, United States). Approximately 20 water samples were collected at the surface and bottom layers using a Niskin water sampler to measure concentrations of Chl a and inorganic nutrients. Duplicate samples were filtered using GF/F filters (47 mm in diameter) and kept in the dark at −20°C before analysis in the laboratory.

Laboratory Analysis

Concentrations of NH4+ and PO43– in pore water were analyzed using the flow injection analysis (FIA) method (Hall and Aller, 1992) and a nutrient autoanalyzer (QUAATRO, Seal Analytical), respectively. Dissolved Fe2+ in pore water was determined by colorimetry with a ferrozine solution (Stookey, 1970). SO42– concentration was measured using ion chromatography (819 IC detector using an A-Supp 5 column, Metrohm, Swiss; 1 mM NaHCO3 + 3.2 mM Na2CO3 eluent). Dissolved sulfide was determined using the methylene blue method (Cline, 1969). Reproducibility of NH4+ was better than 10%. The detection limit of H2S and Fe2+ was 3 and 1 μM, respectively.

Acid volatile sulfides and CRS in sediments were determined using a two-step distillation method with cold 12 M HCl and boiling 0.5 M Cr2+ solution (Fossing and Jørgensen, 1989), and reacted with the Cline solution for extracted S compound analysis (Cline, 1969). Elemental sulfur (S0) was defined as the sulfur extracted with methanol from sediment and measured as cyclo-S8 by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (Zopfi et al., 2004). Oxalate-extractable Fe(II), hereafter Fe(II)(oxal), was extracted in 0.2 M anoxic oxalate solution (pH 3) for 4 h (Phillips and Lovley, 1987), and total Fe(oxal) was extracted from an air-dried sediment in anoxic oxalate (Thamdrup and Canfield, 1996). Fe(II)(oxal) and total Fe(oxal) were determined with ferrozine as described above. Solid Fe(III)(oxal) was defined as the difference between total Fe(oxal) and Fe(II)(oxal). Chl a in surface sediment (0–2 cm) was extracted using 90% acetone for 24 h, and determined using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-2401PC) (Parsons et al., 1984). TOC and TN content in sediment was analyzed using an elemental analyzer (EURO EA 3000, Eurovector S.P.A., via Tortona 5, Milan, Italy) after removal of CaCO3.

Metabolic Rate Measurement

To determine anaerobic Corg mineralization rates, sediment cores (10 cm in diameter, 20 cm in length) were transferred to a glove bag filled with N2 gas and sliced to a depth of 10 cm at 2-cm intervals. The sliced sediments were treated in the same way as the analysis of geochemical constituents. Ten 50-ml centrifuge tubes that were filled with sediment without headspace were incubated in N2 filled gas-tight bags in the dark at in situ temperature. Two tubes were then taken at regular intervals (i.e., 0, 1, 2, 3, and 5 days), and pore water was extracted as described above. Anaerobic Corg mineralization rates were determined by linear regression of the accumulation of total dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in the pore water with added HgCl2 (125 mM) (Hyun et al., 2009) after correcting for CaCO3 precipitation (Thamdrup et al., 2000; Hyun et al., 2017). CaCO3 precipitation was calculated from decreasing dissolved Ca2+ concentration during incubation:

where KCa is the adsorption constant for Ca2+ (KCa = 1.6) (Li and Gregory, 1974). Then the anaerobic Corg mineralization rate corrected for CaCO3 precipitation was calculated as:

Sulfate reduction rates (SRRs) were determined with a radiotracer method (Jørgensen, 1978). Triplicate intact cores (35 cm long with a 3-cm internal diameter) were collected at each site. Two μCi of 35SO42– (Institute of Isotopes Co. Ltd.) were injected into the injection port at 1-cm intervals, and cores were incubated for 2 h at in situ temperatures. At the end of incubation, sediment was sliced into sections, fixed in Zn acetate (20%), and frozen until processing in the laboratory. Extraction of reduced 35S was performed by two-step distillation (Fossing and Jørgensen, 1989), and the radioactivity of the reduced 35S was quantified using a liquid scintillation counter (Tri-Carb 2910 TR; PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, United States). Background radioactivity of 35S at the farm and control sites was 53.9 ± 5.4 cpm cm–3 (n = 9) and 53.9 ± 5.4 cpm cm–3 (n = 9), respectively. Detection limits of the SRR estimated according to Fossing et al. (2000) ranged from 0.58 to 2.29 nmol cm–3 d–1. The Corg mineralization by SR was calculated from the stoichiometric equation (S:C = 1:2) presented in Supplementary Table 2 (Hyun et al., 2017).

To determine iron reduction rates (FeRR), the sediment that was used for the incubation experiment of the anaerobic Corg mineralization rate measurement was homogenized in an anaerobic chamber, and Fe(II)(oxal) was extracted in an anoxic oxalate solution as described above. FeRRs were determined by linear regression of the increase in solid Fe(II)(oxal) concentration with time (Hyun et al., 2009, 2017). The separation of microbial and abiotic processes in FeR and the contribution of FeR to anaerobic Corg mineralization were calculated based on the stoichiometric equation (Fe:S = 2:3, Fe:C = 4:1) presented in Supplementary Table 2 (Hyun et al., 2017).

Sediment Oxygen Demand and Benthic Nutrient Flux

Sediment cores for measuring sediment oxygen demand (SOD) and benthic nutrient flux (BNF) were collected using an acrylic incubation chamber (10 cm diameter, 22 cm length). The benthic chambers were transported to the laboratory immediately after sampling. Incubation began within 6 h of sampling. The benthic chambers were incubated in the dark at in situ temperature, after careful sealing to keep out air bubbles. Overlying water in the benthic chamber was continuously mixed using a geared pump (PQ-12, Greylor Co., flow rate = 0.14 ± 0.02 l min–1). Overlying water for measurement of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) and dissolved inorganic phosphorus (DIP) flux was sampled using the attached syringe of circulation tubing every 1–2 h during incubation. Concentrations of NH4+ and PO43– were analyzed using the nutrient autoanalyzer (QUAATRO, Seal Analytical). SOD and BNF at the sediment-water interface were calculated as follows (Eq. 3):

where F is the flux of oxygen and nutrients (mmol m–2 d–1), (dC/dt) is the slope of the linear regression line derived from the concentration change with time (mmol L–1 d–1), V is the volume of benthic chamber (m3), and A is the area of sediment-water interface (m2). The regression lines were derived from first 4 h of incubation before oxygen was depleted from the fish farm sediment sample.

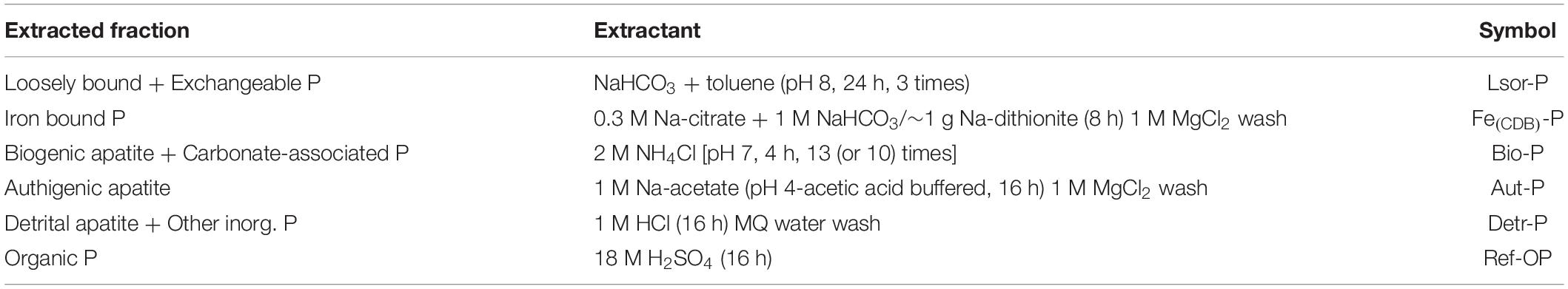

Phosphorus Speciation in the Sediment

Phosphorus speciation in the sediment was determined using the extraction scheme proposed by Anschutz and Deborde (2016) modified from Schenau and De Lange (2000) and Ruttenberg et al. (2009). The extraction procedure of each P fraction is summarized in Table 1. We separated six major P fractions: (1) loosely sorbed and exchangeable P (Lsor-P); (2) easily reducible/reactive Fe-bound P [Fe(CDB)-P], (3) biogenic apatite and carbonate-associated P (Bio-P), (4) authigenic apatite (Aut-P), (5) detrital apatite and other inorganic P (Detr-P), and (6) organic P (Ref-OP). Approximately 0.1 g of wet sediment was subsampled and placed into a 15-mL polypropylene conical tube. Sediment handling and extraction of Lsor-P and Fe(CDB)-P phases were conducted under N2-atmosphere to avoid the exposure to air during drying and to protect resorption of released P in the leaching solution (Kraal and Slomp, 2014; Anschutz and Deborde, 2016). Total P was calculated from the sum of the six different P fractions. Concentrations of phosphorus were measured with an ultraviolet-visible light spectrophotometer at 885 nm as the molybdenum-blue complex (Anschutz and Deborde, 2016), except in the case of Fe(CDB)-P. Because the dithionite and citrate in the Fe(CDB)-P extraction step interfered with the molybdate reagent, concentrations of Fe(CDB)-P were measured by inductively coupled atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES, JY 138, Ultrace, Jobin Yvon, France) (Kraal and Slomp, 2014).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted in SPSS Statistics 26. To compare differences in geochemical properties, metabolic rates, and P distributions in the sediment of farm and control sites, Student’s (independent-samples) t-test was performed. Before analysis, to assess the homogeneity of variance of samples, Levene’s test was used. The level of significance was taken at 5% (P < 0.05).

Results

Environmental Parameters

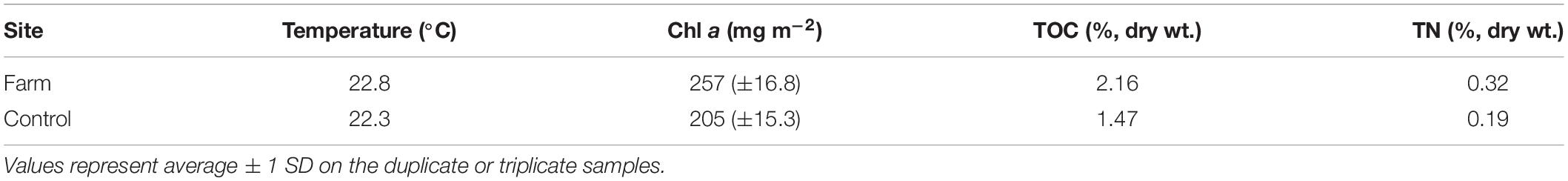

Water temperature and salinity ranged from 22.4 to 26.6°C, and from 31.0 to 32.3, respectively (Table 2). Dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations in seawater were lower at the farm site (114–180 μM) than at the control site (227–260 μM). Low DO saturation (51.5%) was observed in the bottom water of the farm site. DIN and DIP concentrations in seawater ranged from 4.07 to 4.73 μM and from 0.24 to 0.33 μM, respectively. Chl a concentrations in seawater were higher at the farm (3.83–8.11 μg L–1) than at the control site (1.90–2.38 μg L–1) (Table 2). Temperatures in the surface sediment of farm and control sites were 22.8 and 22.3°C, respectively. TOC, TN, and Chl a concentrations in the surface sediment were greater in the farm sediment than in the control sediment (Table 3).

Table 3. Environmental parameters in the surface sediment (0–2 cm) of the fish farm and control sites.

Pore-Water and Solid-Phase Constituents

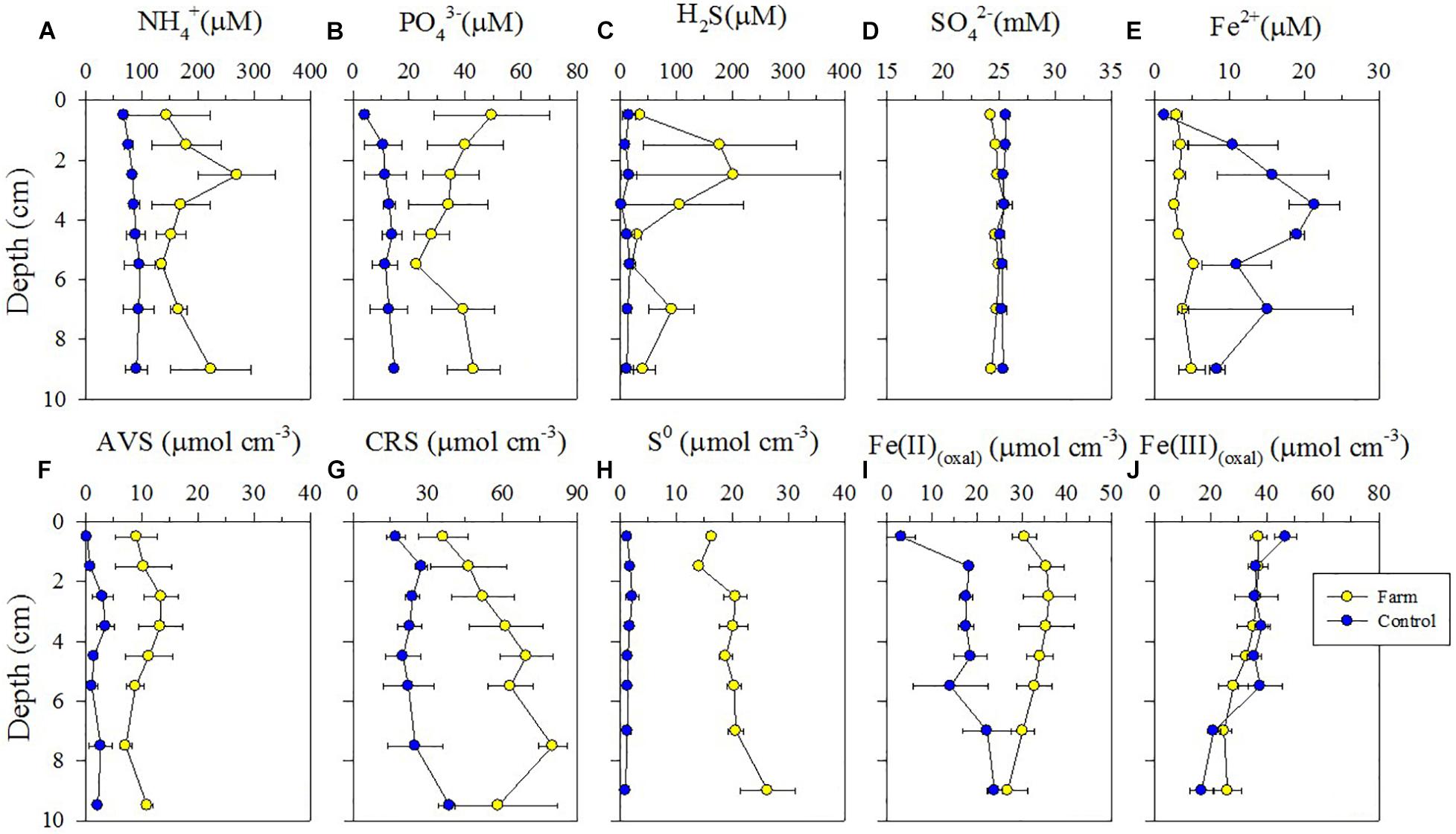

Concentrations of NH4+, PO43–, and H2S in pore water were significantly higher at the farm than at the control site (Figures 2A–C, P < 0.05). Depth-integrated (0–10 cm) concentrations of NH4+, PO43–, and H2S in pore water at the farm were 2. 2-, 3. 3-, and 7.4-fold higher than at the control site, respectively (Table 4). SO42– concentrations, which ranged from 24.2 to 25.6 mM in pore water from both sites, showed a vertically homogenous distribution patterns (Figure 2D, P = 0.414). In contrast, Fe2+ concentrations in pore water from the farm sediment were 3.0-fold lower than at the control site (Figure 2E and Table 4, P < 0.05).

Figure 2. Vertical distributions of geochemical constituents in pore water (A–E) and of AVS, CRS, S0, Fe(II)(oxal), and Fe(III)(oxal) in sediment (F–J) of the farm and control sites.

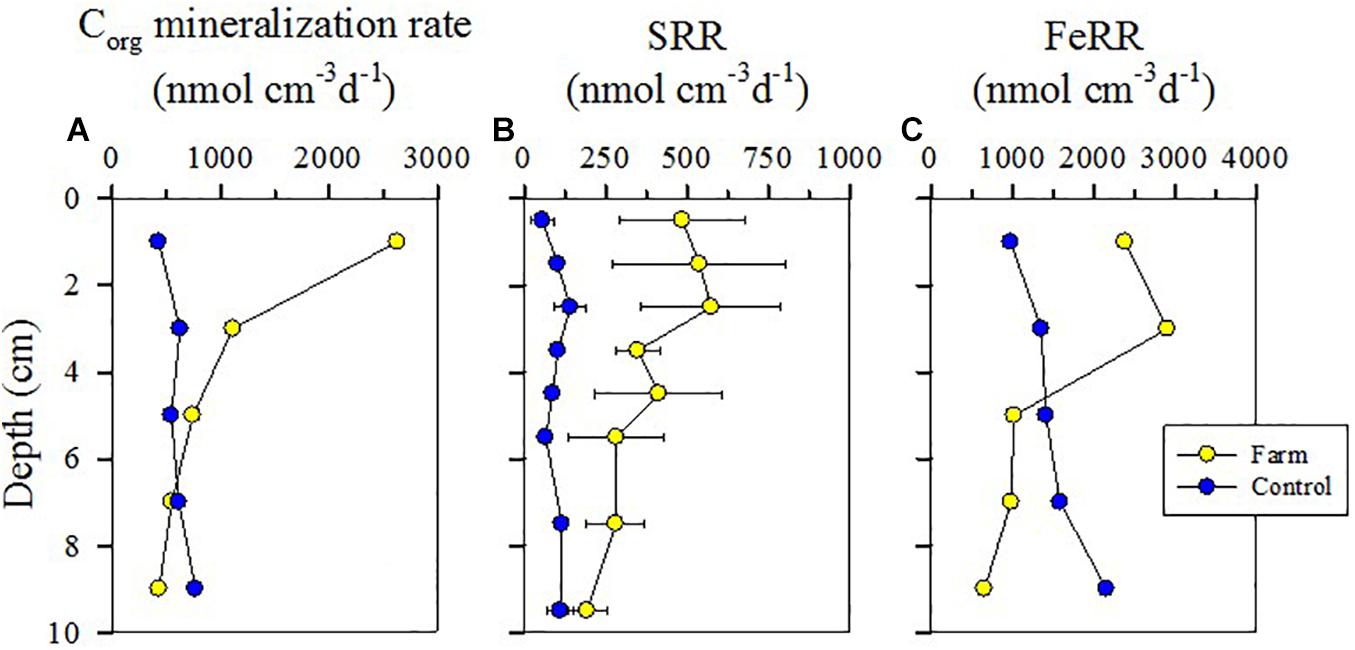

Table 4. Depth integrated (0–10 cm) concentrations of the pore water and solid phase constituents in sediments (mmol m–2).

Reduced sulfur compound content (i.e., AVS, CRS, and S0) was significantly higher at all depths of farm sediment compared with control sediment (Figures 2F–H, P < 0.001). Depth-integrated (0–10 cm) content of AVS and CRS in the sediments were 5.2- and 2.3-fold higher at the farm than at the control site, respectively (Table 4). Depth-integrated S0 content in the farm sediment was 13.6-fold greater than in the control sediment (Table 4). Solid Fe(II)(oxal) content was significantly higher within 6 cm depths of the farm sediment compared with the control sediment (Figure 2I, P < 0.05), whereas solid Fe(III)(oxal) content in sediment was similar at both sites (Figure 2J, P = 0.737). Depth-integrated (0–10 cm) Fe(II)(oxal) content in sediment was 1.8-fold greater at the farm compared with the control site, whereas Fe(III)(oxal) content in sediment was similar at the two sites (Table 4). Overall, dissolved and solid-phase constituent analysis revealed that fish farm sediment exhibited highly reduced conditions, with higher concentrations of NH4+, PO43–, and H2S in pore water and greater AVS, CRS, So, and Fe(II) content in sediments compared with control site sediment (Figure 2).

Rates of Anaerobic Corg Mineralization, Sulfate Reduction, and Iron Reduction

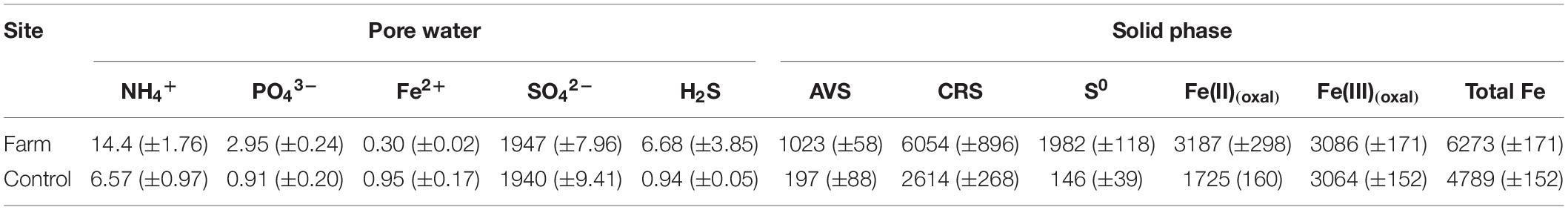

Both SR and FeR in the farm sediment were significantly greater than in the control sediment (P < 0.05), especially in the surface layer (Figure 3). SRR (11.0 mmol S m–2 d–1) and FeRR (47.8 mmol Fe m–2 d–1) within a depth of 2 cm of the farm sediment were 6.9-fold and 2.4-fold higher than those measured at the control site (1.58 mmol S m–2 d–1 and 19.6 mmol Fe m–2 d–1), respectively (Supplementary Table 2). Total anaerobic Corg mineralization rates (1872 ± 1071 nmol cm–3 d–1) within a depth of 4 cm of the farm sediment was 3.6-fold greater than that (527 ± 139 nmol cm–3 d–1) of the control sediment, although this difference was not significant (P = 0.22) (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure 1). In particular, the anaerobic Corg mineralization rate within 2 cm of the farm sediment (52.6 mmol C m–2 d–1) was up to 6.1-fold higher than that measured in the control sediment (8.56 mmol C m–2 d–1) (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 3. Vertical profiles of anaerobic Corg mineralization rates (A), sulfate reduction rates (SRRs) (B), and iron reduction rates (FeRRs) (C) in the fish farm and control sediment.

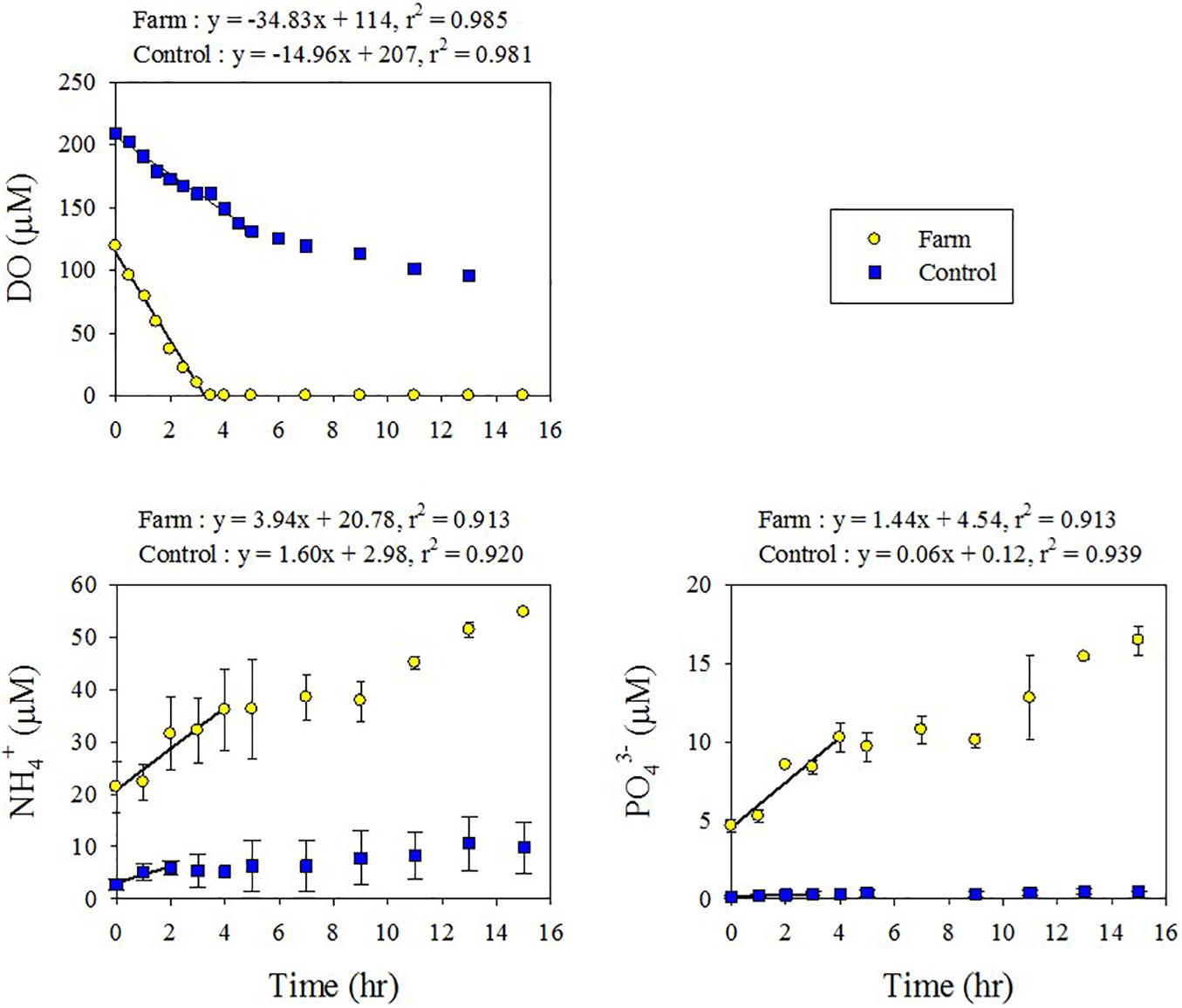

Sediment Oxygen Demand and Benthic Nutrient Release

Sediment oxygen demand, as determined by linear regression of the decrease in DO concentration with time (Figure 4), was 2.5-fold higher in the farm sediment (107 mmol O2 m–2 d–1) compared with the control sediment (43.1 mmol O2 m–2 d–1) (Supplementary Table 2). The flux of DIN and DIP was estimated from concentration variation in the overlying water of the chamber during incubation (Figure 4). Benthic NH4+ fluxes in the farm and control sediments were 11.4 and 4.61 mmol N m–2 d–1, respectively, and NOx fluxes were −0.25 and 0.11 mmol N m–2 d–1, respectively. Consequently, the DIN fluxes calculated from the sum of NH4+ and NOx fluxes were 2.4-fold higher in the farm sediment (11.1 mmol N m–2 d–1) compared with the control sediment (4.72 mmol N m–2 d–1) (Table 5). The DIP flux in the farm sediment (4.13 mmol P m–2 d–1) was 24.3-fold greater than that measured in the control sediment (0.17 mmol P m–2 d–1) (Table 5).

Figure 4. Changes in dissolved oxygen (DO), NH4+, and PO43– concentrations with time in the benthic chamber of the fish farm and control sediment. Note that the regression lines were derived from first 4 h of incubation before the depletion of oxygen concentration in the fish farm sediment sample.

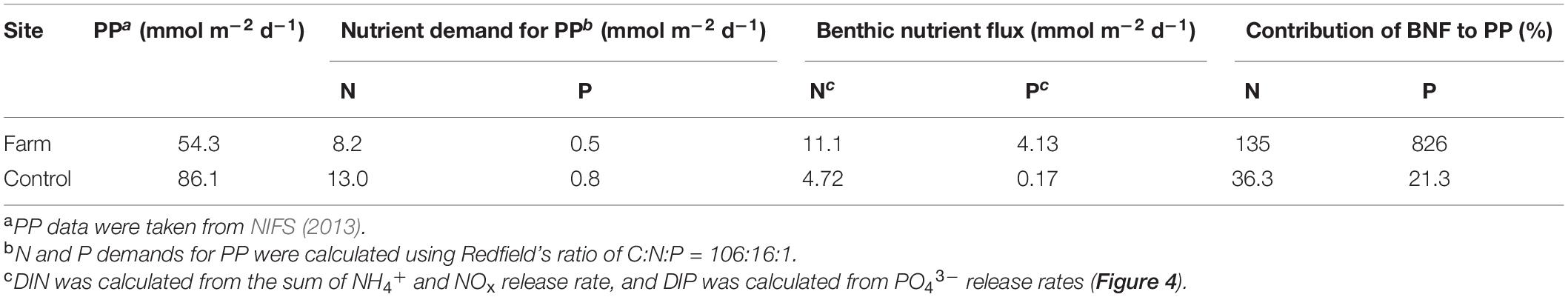

Table 5. Nutrient demand for primary production (PP), benthic nutrient flux (BNF), and contribution of BNF to PP.

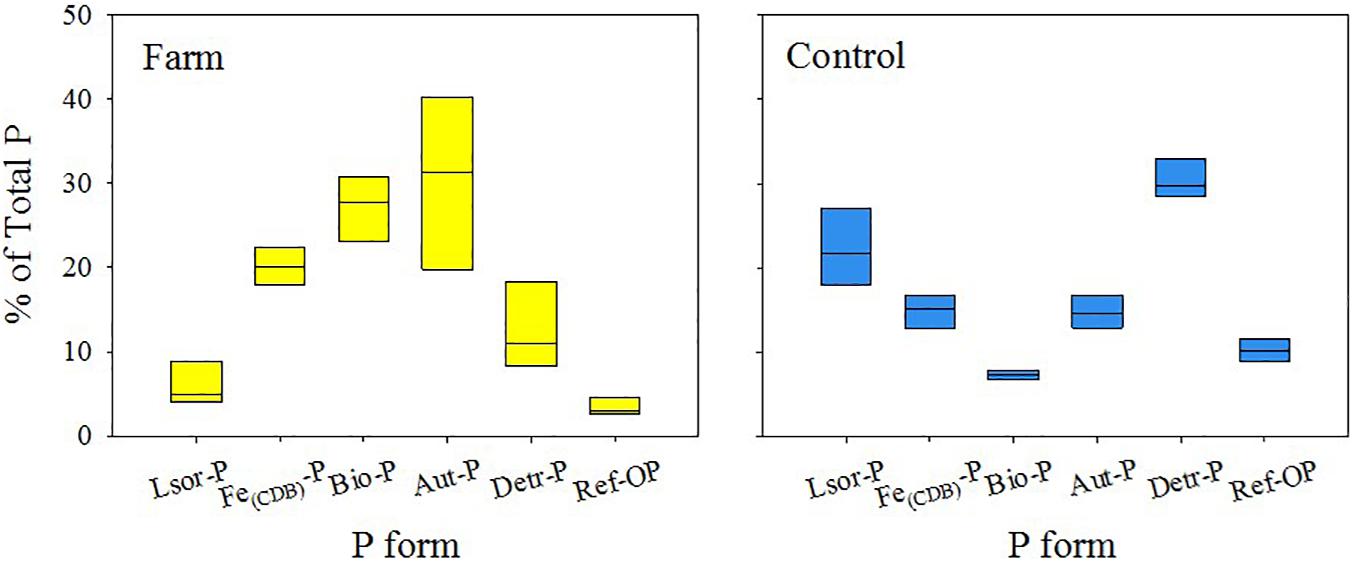

Speciation of Phosphorus in the Sediments

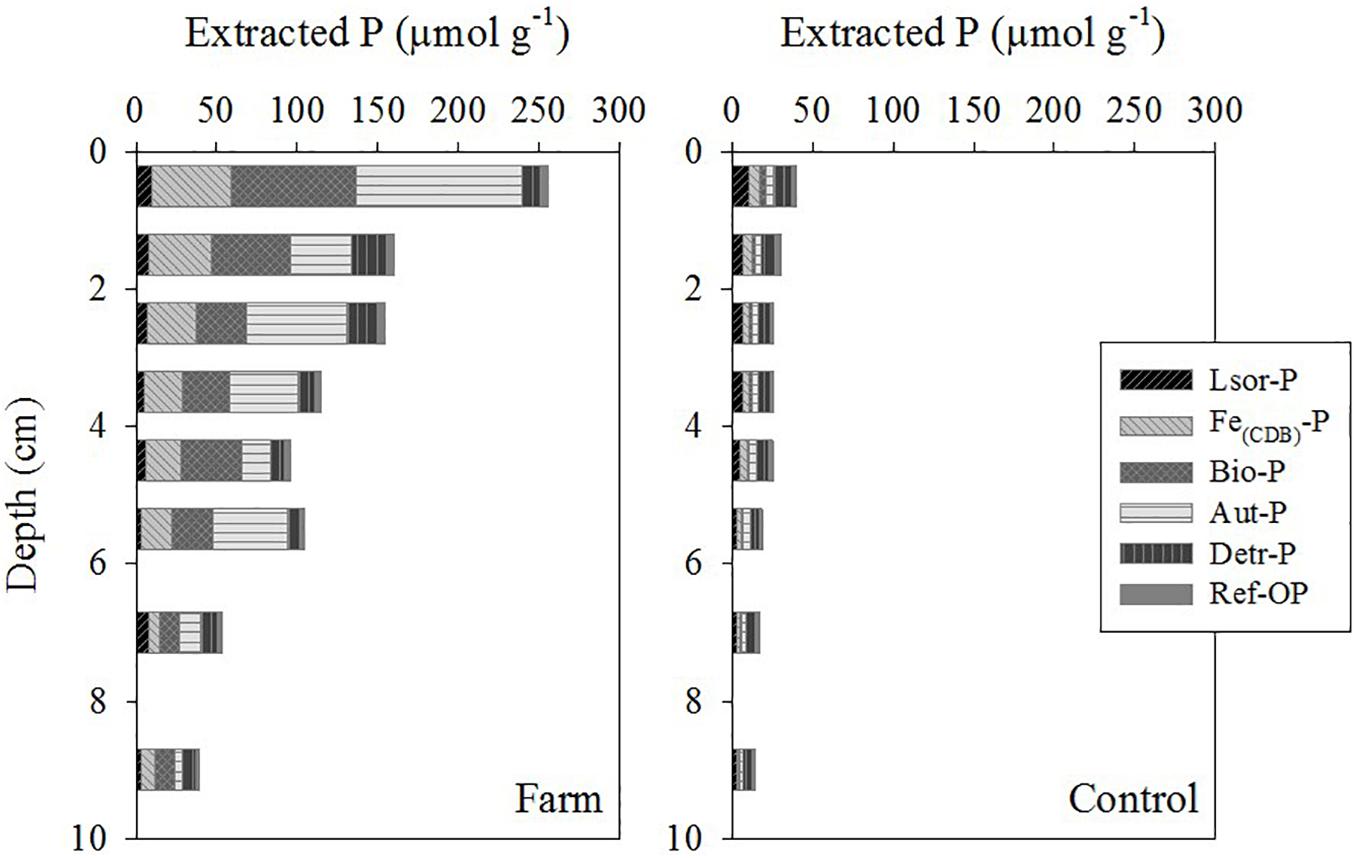

The content and distribution of P forms in sediment varied significantly between the farm and control site (Figures 5, 6, P < 0.05) except for Lsor-P (P = 0.532). Within a depth of 10 cm, total P content in the farm sediment (39–256 μmol g–1) was 4.5-fold greater than measured in the control sediment (14–40 μmol g–1) (Supplementary Table 3). The total P profile in the farm sediment was largely determined by the distribution of Fe(CDB)-P, Bio-P, and Aut-P, whereas the distribution of Lsor-P and Detr-P was mostly responsible for the shape of total P in the control sediment (Figure 6). Vertically, the three major P fractions, i.e., Fe(CDB)-P, Bio-P, and Aut-P, were highest in the surface layer (0–1 cm) of the farm sediment and decreased with depth (Figure 5).

Figure 6. Average proportion (%) of P forms within a depth of 10 cm of the fish farm and control sediment.

Lsor-P content was similar in both sites, ranging from 4 to 10 μmol g–1 and from 3 to 11 μmol g–1 in the sediments of the farm and control site, respectively, and the concentration decreased with depth (Figure 5). Lsor-P constituted a minor P form in the farm sediment, accounting for 4–15% of total P within 10 cm of depth, whereas it comprised 16–28% of total P in the control sediment (Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 3). Fe(CDB)-P content ranged from 6 to 49 μmol g–1, and from 1 to 7 μmol g–1 in the farm and control sediment, respectively, and the concentration of Fe(CDB)-P decreased with depth (Figure 5). The Fe(CDB)-P form accounted for 12–24% and 7–18% of total P within a depth of 10 cm in the farm and control sediment, respectively (Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 3). Bio-P content ranged from 12 to 78 μmol g–1 and from 1 to 3 μmol g–1 in the farm and control sediment, respectively, and the concentration of Bio-P decreased with depth (Figure 5). Bio-P constituted the major P form in the farm sediment, accounting for 20–39% of total P, but only 6–8% of total P in the control sediment (Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 3). Aut-P content ranged from 14 to 102 μmol g–1 and from 5 to 102 μmol g–1 in the farm and control sediment, respectively. Overall, Aut-P content decreased with depth (Figure 6). This form, together with Bio-P, constituted the major P form to a depth of 10 cm in the farm sediment, representing 12–44% of total P (Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 3). Detr-P contents ranged from 8 to 21 μmol g–1 and from 5 to 11 μmol g–1 in the farm and control sediment, respectively (Figure 5). Detr-P constituted the major P form in the control sediment, accounting for 28–37% of total P to a depth of 10 cm (Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 3). Ref-OP content, which ranged from 2 to 5 μmol g–1 and from 2 to 3 μmol g–1 in the farm and control sediment, respectively, was similar at both sites (Figure 5). This form accounted for 2–5% and 8–12% of total P within 10 cm of depth in the farm and control sediment, respectively, and thus constituted a minor P form together with Lsor-P in the farm sediment (Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

Impact of Farming on Phosphorus Enrichment and Speciation

The most prominent features revealed by P speciation analysis were that: (1) high total P, more than four-fold greater than the control site, accumulated in fish farm sediment (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 3), and (2) Aut-P and Bio-P were the dominant fractions of P forms (Figure 6). The higher accumulation of total P in farm sediment (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 3) directly reflected the impact of P-rich fish feed in fish farm regions (Karakassis et al., 1998; Holmer et al., 2002; Soto and Norambuena, 2004; Porrello et al., 2005; Matijević et al., 2008). Several studies have estimated that 60–70% of the P in feed is discharged as waste into the marine environment (Olsen et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2012; Bouwman et al., 2013), which is equivalent to the discharge of 9.4–25 kg of P waste per ton of fish production (Holby and Hall, 1991; Islam, 2005; Wang et al., 2012). Based on the P content in fish feed (0.8%, Christensen et al., 2000) and the feed input from the present study area (Status of Fish Culture 2017)2, 8–16 kg of P waste per ton of fish production would be generated in the study area. If 53% of the P in fish feed is accumulated in coastal sediment (Wu, 2001), the sinking of uneaten fish feed and fecal production from fish farms is directly responsible for P enrichment in sediment.

In addition to the insight it provided into P enrichment, P-speciation analysis clearly demonstrated the proportional order of each form of P in farm sediment [Aut-P > Bio-P > Fe(CDB)-P > Detr-P > Lsor-P > Ref-OP] and control sediment [Detr-P > Lsor-P > Fe(CDB)-P > Aut-P > Ref-OP > Bio-P] (Figure 6). The down-core increase in Aut-P in control sediment is resulted from the precipitation of Ca2+ with P that is released by Corg mineralization, which is responsible for the mirror image observed in the relative abundance of Fe(CDB)-P and Aut-P with depth (i.e., sink-switching between Fe-P and Aut-P) (Supplementary Figure 2; Ruttenberg, 2003). However, this sink-switching model did not appear in the farm sediment where the relative abundance of Aut-P was highest in surface layer (Supplementary Figure 2). The high proportion of Aut-P together with the high PO43– concentration in surface sediment at the farm site is primarily related to mineralization of organic matter (i.e., P-rich fish feed). The P released during Corg remineralization resulted in the P supersaturation in pore water with respect to apatite, which ultimately forms Aut-P (Slomp et al., 1996; Schenau et al., 2000; van der Zee et al., 2002; Andrieux-Loyer et al., 2014). In organic-rich sediment in particular, the regeneration of inorganic P from Corg remineralization was the predominant process for Aut-P precipitation (Anschutz et al., 2007; Tsandev et al., 2012; Joshi et al., 2015; Kraal et al., 2017). The enhancement of Corg mineralization rate and reductive dissolution of Fe oxides resulting from the reaction of FeOOH with sulfide in the organic-rich farm sediment were directly responsible for the strong surface enrichment of Aut-P (102 μmol g–1, 40% of total P) in the farm sediment (Figure 5; van der Zee et al., 2002; Brock and Schulz-Vogt, 2011; Slomp, 2011; Andrieux-Loyer et al., 2014; Supplementary Table 1). In particular, the accumulation of S0 in the sediments may result from the reaction between FeOOH and H2S (Figure 2H and Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, as biogenic hydroxyapatite (Bio-P) is more soluble than fluorapatite, additional phosphate is released into pore water during the Bio-P dissolution process after deposition, which results in a subsequent precipitation of P into the CFA (Froelich et al., 1988; Kassila et al., 2001; Schenau and De Lange, 2001).

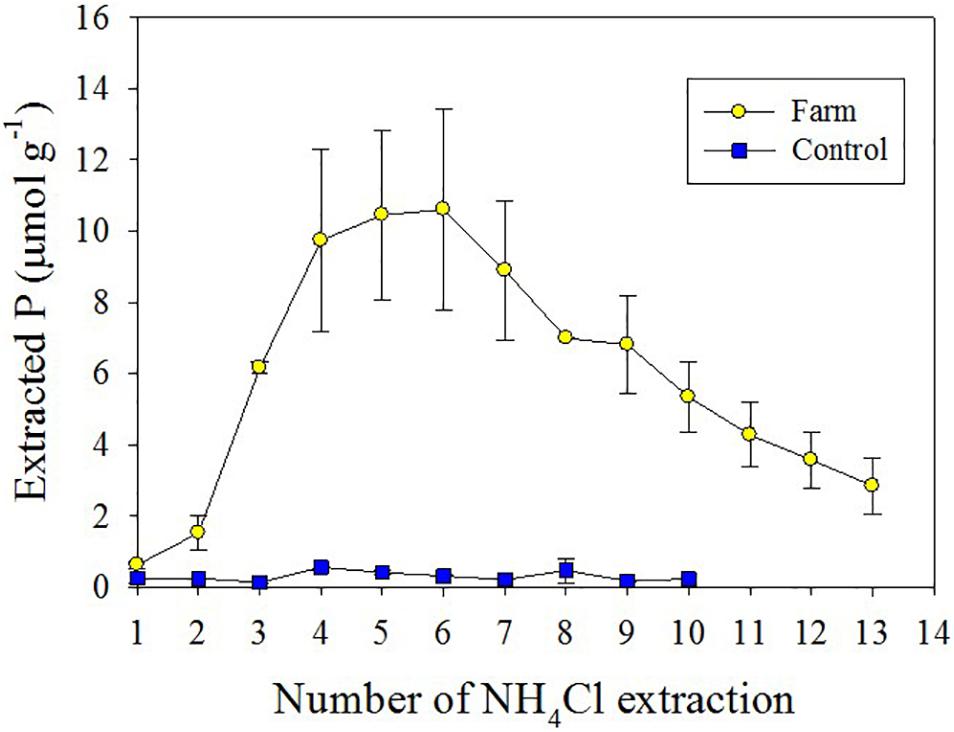

The abundance of Bio-P in farm sediment is associated with P-rich fish feed. In sequential extraction methods, authigenic apatite generally includes authigenic CFA, biogenic apatite, and CaCO3-associated P (Jensen et al., 1998; Ruttenberg et al., 2009). However, Schenau and De Lange (2000) recognized that a significant amount of reactive P was removed through high preservation of fish debris consisting of hydroxyapatite in surface deposits from the Arabian Sea, which suggested the need for identification of P associated with biogenic apatite (Bio-P) from authigenic apatite. In this regard, an additional attempt was made to separate biogenic P (Bio-P) associated with fish debris from Aut-P to assess the impact of fish farming on coastal environments through repeated NH4Cl extraction (Matijević et al., 2008). Indeed, repeated NH4Cl extraction revealed that the concentrations of extracted P in farm sediment increased sharply from the third extraction step, and then remained high until the seventh extraction, whereas NH4Cl-extracted P in the control sediment remained low throughout the extraction procedure (Figure 7). As a result, Bio-P in the farm sediment (78 μmol g–1, 31% of total P) was up to 25 times higher in surface layers compared with that in the control sediment (3 μmol g–1, 8% of total P). These results clearly demonstrate that the deposition of feed was directly responsible for the high surface accumulation of Bio-P in the fish farm sediments, and thus directly affected P speciation in sediment (Figures 5, 6).

Impact of Fish Farming on P Dynamics Associated With Iron- and Sulfate Reduction

In the present study, despite the high sinking particle flux (126.2 g m–2 d–1, NIFS, 2013) at the farm site, the organic content in the fish farm sediments (2.16% TOC) was lower than the values reported in other fish farm sediments (Holmer and Kristensen, 1992; Holmer et al., 2002; á Norði et al., 2011; Bannister et al., 2014). The high current speed (average 28–33 cm s–1, Ro et al., 2007) and high polychaete density (approximately 2,500 inds. m–2, NIFS, 2013) likely explain this low organic matter accumulation. For example, Holmer and Frederiksen (2007) reported low organic content (average 0.51–1.60% POC) despite high sinking particle fluxes (32.3–63.8 g m–2 d–1) in farm sediments from the Mediterranean Sea and attributed it to dispersion of waste products under rapid water exchange (>5.5 cm s–1) and or the consumption of waste products by benthic fauna, i.e., up to 400 inds. m–2 polychaetes (Hermodice carunculata) (Heilskov et al., 2006) or up to 60 inds. m–2 sea urchins (Ruiz et al., 2001).

Analysis of geochemical constituents and metabolic rate measurement clearly revealed that high organic loading (126.2 g m–2 d–1) in the fish farm greatly stimulated benthic metabolism (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 2), which resulted in increased accumulation of mineralization products (i.e., NH4+, H2S, and PO43–) in pore water from farm sediment (Figures 2A–C and Table 4). SR was a dominant Corg mineralization pathway in the farm sediment, accounting for 70% of anaerobic Corg mineralization (Supplementary Table 2). Stimulation of SR by aquaculture has been continuously demonstrated in several fish farms where feed or feces are deposited directly onto the sediment (Holmer et al., 2002, 2003; Holmer and Frederiksen, 2007; Holmer and Heilskov, 2008; Valdemarsen et al., 2009; á Norði et al., 2011; Hyun et al., 2013; Bannister et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2018, 2020). Along with enhanced SR, abundant Fe oxides (∼ 40 μmol cm–3; Figure 2J) would ultimately stimulate FeR in surface sediments of the farm (Figure 3C; Thamdrup, 2000).

The enrichment of dissolved Fe2+ in pore water can be ascribed to the stimulation of dissimilatory FeR or chemical reduction of Fe oxides coupled with H2S oxidation (Canfield, 1989; Hyun et al., 2013; An et al., 2019). However, despite the high FeRR in farm surface sediments, the Fe2+ concentration in pore water of farm sediment was strikingly lower than that of the control sediment (Figure 2E). This decoupling of FeR and Fe2+ was due to the precipitation of dissolved Fe2+ with surplus sulfides derived from the high SR (Canfield et al., 2005; Firer et al., 2008), which subsequently stimulated reactions between Fe and S to form high FeS (AVS) and FeS2 (CRS) content in the sediments (Figures 2F,G and Supplementary Table 1; Thamdrup et al., 1994; Jørgensen et al., 2019). In addition, under high Corg loading conditions, SR dominates Corg mineralization, which ultimately results in high P release by lowering the binding capacity of Fe to P due to the formation of FeS minerals (i.e., uncoupled cycling of Fe and P) (Lehtoranta et al., 2008, 2009; An et al., 2019).

Enhanced Phosphorus Availability and Benthic Phosphorus Flux in Fish Farm Sediment

Higher SOD and benthic nutrient release (Figure 4) in fish farm sediment compared with control sediment indicate that the enhanced Corg mineralization resulting from excess input of organic wastes was directly responsible for the stimulation of benthic nutrient release into the water column. Interestingly, the ratio of benthic release rate between ammonium (3.94 μmol N L–1 h–1) and phosphate (1.44 μmol P L–1 h–1) in the farm sediment (i.e., N/P = 2.74) was 9.7 times lower than that measured in the control sediment (i.e., N/P = 26.7) (Figure 4), which further suggests that benthic P release was greatly stimulated during the mineralization process of fish feed and subsequent P dynamics (Jia et al., 2015; Ferrera et al., 2016). Under SR-dominant conditions, the desorption of P via reduction of FeOOH coupled with H2S oxidation would be directly responsible for highly enhanced release of P from the sediment of the farm (Lehtoranta et al., 2008, 2009). The low P binding capacity (i.e., high P availability in pore water) in the farm sediment was further demonstrated through P regeneration efficiency (% Precyc), which can be estimated from the percentage of benthic P flux (Fp) directly measured from the benthic chamber incubation (Table 5) relative to the theoretical benthic P flux (Fcp = Corg oxidation rate × 1/C:P) based on Redfield stoichiometry (C:P = 106:1) (Eq. 4, Ferrón et al., 2009a).

The measured benthic P flux (Fp) in the farm sediment (4.13 mmol m–2 d–1; Table 5) was similar to the expected benthic P flux (4.86 mmol m–2 d–1). By contrast, Fp in the control sediment (0.17 mmol m–2 d–1; Table 5) was 3.3 times lower than Fcp (0.56 mmol m–2 d–1). Finally, the % Precyc calculated according to the Eq. 4 in the farm sediment (85%) was approximately three-fold greater than that estimated in the control sediment (30%). Here, the C:P ratio in the farm sediment was assumed to be lower than the Redfield ratio used in the control sediment (C:P = 106:1) due to the high P content in fish feed (Ferrón et al., 2009b), and thus we adopted the C:P ratio for organic matter (average 22.5) in the surface sediment measured by Holmer et al. (2007) in the case of the farm sediment. These results indicated that P could be quickly released to the water column through mineralization of organic matter from the farm sediment, whereas most P in the control sediment would be retained in the sediment. In addition, in the farm sediment, high Precyc may be partly associated with P release through the chemical dissolution of Fe oxides and microbial metabolism (i.e., decomposition of polyphosphate) (Ferrón et al., 2009b; Brock and Schulz-Vogt, 2011).

The results also strongly suggest that, along with analysis of the P pool size, a separation of P forms in sediment is required to determine the upper limit of P availability associated with aquaculture in an aquatic ecosystem (Andrieux and Aminot, 1997; Hou et al., 2009). Hou et al. (2009) described bioavailable P as an integrated concentration of Lsor-P, Fe(CDB)-P, and Ref-OP. In the present study, Bio-P was additionally included in bioavailable P, due to the chemical dissolution properties of Bio-P (Schenau and De Lange, 2001). In the present study, the bioavailable P content within surface sediment to a depth of 2 cm (that is directly influenced by organic loading from the water column) was 2,902 mmol m–2 (58% of total P) in the farm sediment (Supplementary Table 3).

This high level of bioavailable P indicates that sediment below fish farms plays an important role as an internal source of P for coastal ecosystems (Ferrón et al., 2009b; Hou et al., 2009; Viktorsson et al., 2013; An et al., 2019). For example, Christensen et al. (2000) pointed out that aquaculture could have an impact on the entire coastal environment by supplying 42% of total P input in summer, even though fish farms occupy a relatively small area (0.02% of the total coastal area). In the present study, benthic release of N and P accounted for 135 and 826%, respectively, of the N and P required for primary production (Table 5). Because the occurrence of certain dinoflagellates (e.g., Cochlodinium polykrikoides) in coastal waters, including the study area, is often associated with excess P in the water column (Thomas and Smayda, 2008; Cho, 2010; Lee et al., 2015), the results suggest that the excessive benthic P flux (or P availability) from aquaculture sediment could be a significant factor triggering harmful algal blooms (Rozan et al., 2002; Stal et al., 2003; Joshi et al., 2015; Schoffelen et al., 2018).

Conclusion

Input of fish feed associated with fish farming activity significantly enhanced the accumulation of biogenic apatite P in sediment, suggesting that it could be used as a sensitive indicator for the assessment of environmental conditions in fish farm sediments, especially those related to fish feed. High benthic metabolism by SR in farm sediment greatly stimulated P release into pore water, which ultimately altered P speciation by increasing the Aut-P fraction in total P. Enhanced P regeneration efficiency and high P bioavailability in the farm sediment suggests that the sediment below the fish farm acts as an internal source of P to support primary production in the coastal ecosystem. Overall results strongly suggest that variations in P forms and benthic P flux coupled with Corg mineralization and resulting C-Fe-S cycles in the sediment could provide important information for quantitative and qualitative assessments of the impact of aquaculture in coastal ecosystems.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

J-SM and J-HH designed the study and conducted most writing of the manuscript. J-SM, AC, BK, and S-UA collected the samples and performed most laboratory analysis. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Fisheries Science (NIFS; R2021056) and National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Ministry of Science and Information Communication Technology (NRF-2018R1A2B2006340), and Ministry of Education (NRF-2020R1I1A1A01073965).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.645449/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

á Norði, G., Glud, R. N., Gaard, E., and Simonsen, K. (2011). Environmental impacts of coastal fish farming: carbon and nitrogen budgets for trout farming in Kaldbaksfjør?ur (Faroe Islands). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 431, 223–241. doi: 10.3354/meps09113

An, S.-U., Mok, J.-S., Kim, S.-H., Choi, J.-H., and Hyun, J.-H. (2019). A large artificial dyke greatly alters partitioning of sulfate and iron reduction and resultant phosphorus dynamics in sediments of the Yeongsan River estuary, Yellow Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 665, 752–761. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.058

Andrieux, F., and Aminot, A. (1997). A two-year survey of phosphorus speciation in the sediments of the Bay of Seine (France). Cont. Shelf Res. 17, 1229–1245. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4343(97)00008-3

Andrieux-Loyer, F., Azandegbé, A., Caradec, F., Philippon, X., Kérouel, R., Youenou, A., et al. (2014). Impact of oyster farming on diagenetic processes and the phosphorus cycle in two estuaries (Brittany, France). Aquat. Geochem. 20, 573–611. doi: 10.1007/s10498-014-9238-7

Anschutz, P., Chaillou, G., and Lecroart, P. (2007). Phosphorus diagenesis in sediment of the Thau Lagoon. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 72, 447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2006.11.012

Anschutz, P., and Deborde, J. (2016). Spectrophotometric determination of phosphate in matrices from sequential leaching of sediments. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 14, 245–256. doi: 10.1002/lom3.10085

Bannister, R. J., Valdemarsen, T., Hansen, P. K., Holmer, M., and Ervik, A. (2014). Changes in benthic sediment conditions under an Atlantic salmon farm at a deep, well-flushed coastal site. Aquacult. Environ. Interact. 5, 29–47. doi: 10.3354/aei00092

Bouwman, L., Beusen, A., Gilbert, P. M., Overbeek, C., Pawlowski, M., Herrera, J., et al. (2013). Mariculture: significant and expanding cause of coastal nutrient enrichment. Environ. Res. Lett. 8:044026. doi: 10.1080/10641262.2013.790340

Brock, J., and Schulz-Vogt, H. N. (2011). Sulfide induces phosphate release from polyphosphate in cultures of a marine Beggiatoa strain. ISME J. 5, 497–506. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.135

Canfield, D. E. (1989). Reactive iron in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 53, 619–632. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(89)90005-7

Canfield, D. E., Thamdrup, B., and Kristensen, E. (2005). Aquatic Geomirobiology. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 640.

Cho, E.-S. (2010). A comparative study on outbreak and non-outbreak of Cochlodinium polykrikoides Margalef in south sea of Korea in 2007-2009. J. Korean Soc. Mar. Environ. Saf. 16, 31–41.

Choi, A., Cho, H., Kim, B., Kim, H. C., Jung, R.-H., Lee, W.-C., et al. (2018). Effects of finfish aquaculture on biogeochemistry and bacterial communities associated with sulfur cycles in highly sulfidic sediments. Aquacult. Environ. Interact. 10, 413–427. doi: 10.3354/aei00278

Choi, A., Kim, B., Mok, J.-S., Yoo, J., Kim, J. B., Lee, W.-C., et al. (2020). Impact of finfish aquaculture on biogeochemical processes in coastal ecosystems and elemental sulfur as a relevant proxy for assessing farming condition. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 150:110635. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110635

Christensen, P. B., Rysgaard, S., Sloth, N. P., Dalsgaard, T., and Schwærter, S. (2000). Sediment mineralization, nutrient fluxes, denitrification and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium in an estuarine fjord with sea cage trout farms. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 21, 73–84. doi: 10.3354/ame021073

Cline, J. D. (1969). Spectrophotometric determinations of hydrogen sulfide in natural waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 14, 454–458. doi: 10.4319/lo.1969.14.3.0454

David, C. P. C., Sta. Maria, Y. Y., Siringan, F. P., Reotita, J. M., Zamora, P. B., Villanoy, C. L., et al. (2009). Coastal pollution due to increasing nutrient flux in aquaculture sites. Environ. Geol. 58, 447–454. doi: 10.1007/s00254-008-1516-5

Diaz, R. J., and Rosenberg, R. (2008). Spreading dead zones and consequences for marine ecosystems. Science 321, 926–929. doi: 10.1126/science.1156401

FAO (2018). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018. Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals. Rome: FAO.

Ferrera, C. M., Watanabe, A., Miyajima, T., San Diego-McGlone, M. L., Morimoto, N., Umezawa, Y., et al. (2016). Phosphorus as a driver of nitrogen limitation and sustained eutrophic conditions in Bolinao and Anda, Philippines, a mariculture-impacted tropical coastal area. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 105, 237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.02.025

Ferrón, S., Alonso-Pérez, F., Anfuso, E., Murillo, F. J., Ortega, T., Castro, C. G., et al. (2009a). Benthic nutrient recycling on the northeastern shelf of the Gulf of Cádiz (SW Iberian Peninsula). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 390, 79–95. doi: 10.3354/meps08199

Ferrón, S., Ortega, T., and Forja, J. M. (2009b). Benthic fluxes in a tidal salt marsh creek affected by fish farm activities: Río San Predo (Bay of Cádiz, SW Spain). Mar. Chem. 113, 50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2008.12.002

Firer, D., Friedler, E., and Lahav, O. (2008). Control of sulfide in sewer systems by dosage of iron salts: comparison between theoretical and experimental results, and practical implications. Sci. Total Environ. 392, 145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.11.008

Fossing, H., Ferdelman, T. G., and Berg, P. (2000). Sulfate reduction and methane oxidation in continental margin sediments influenced by irrigation (South-East Atlantic off Namibia). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 64, 897–910. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(99)00349-X

Fossing, H., and Jørgensen, B. B. (1989). Measurement of bacterial sulfate reduction in sediments: evaluation of a single-step chromium reduction method. Biogeochemistry 8, 205–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00002889

Froelich, P. N., Arthur, M. A., Burnett, W. C., Deakin, M., Hensley, V., Jahnke, R., et al. (1988). Early diagenesis of organic matter in Peru continental margin sediments: phosphorite precipitation. Mar. Geol. 80, 309–343. doi: 10.1016/0025-3227(88)90095-3

Goldhammer, T., Brüchert, V., Ferdelman, T. G., and Zabel, M. (2010). Microbial sequestration of phosphorus in anoxic upwelling sediments. Nat. Geosci. 3, 557–561. doi: 10.1038/ngeo913

Hall, P. O. J., and Aller, R. C. (1992). Rapid small-volume, flow injection analysis for CO2 and NH4+ in marine and freshwaters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 37, 1113–1119. doi: 10.4319/lo.1992.37.5.1113

Hall, P. O. J., Anderson, L. G., Holby, O., Kollberg, S., and Samuelsson, M.-O. (1990). Chemical fluxes and mass balances in a marine fish cage farm. I. Carbon. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 61, 61–73. doi: 10.3354/meps061061

Heijs, S. K., Azzoni, R., Giordani, G., Jonkers, H. M., Nizzoli, D., Viaroli, P., et al. (2000). Sulfide-induced release of phosphate from sediments of coastal lagoons and the possible relation to the disappearance of Ruppia sp. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 23, 85–95. doi: 10.3354/ame023085

Heilskov, A., Alperin, M., and Holmer, M. (2006). Benthic fauna bio-irrigation effects on nutrient regeneration in fish farm sediments. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 339, 204–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2006.08.003

Holby, O., and Hall, P. O. J. (1991). Chemical fluxes and mass balances in a marine fish cage farm. II. Phosphorus. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 70, 263–272. doi: 10.3354/meps070263

Holmer, M., Argyrou, M., Dalsgaard, T., Danovaro, R., Diaz-Almela, E., Duarte, C. M., et al. (2008). Effects of fish farm waste on Posidonia oceanica meadows: synthesis and provision of monitoring and management tools. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 56, 1618–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.05.020

Holmer, M., Duarte, C. M., Heilskov, A., Olesen, B., and Terrados, J. (2003). Biogeochemical conditions in sediments enriched by organic matter from net-pen fish farms in the Bolinao area, Philippines. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 46, 1470–1479. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(03)00281-9

Holmer, M., and Frederiksen, M. S. (2007). Stimulation of sulfate reduction rates in Mediterranean fish farm sediments inhabited by the seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Biogeochemistry 85, 169–184. doi: 10.1007/s10533-007-9127-x

Holmer, M., and Heilskov, A. C. (2008). Distribution and bioturbation effects of the tropical alpheid shrimp Alpheus macellarius in sediments impacted by milkfish farming. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 76, 657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2007.07.033

Holmer, M., and Kristensen, E. (1992). Impact of marine fish cage farming on metabolism and sulfate reduction of underlying sediments. Mar. Ecol. Porg. Ser. 80, 191–201. doi: 10.3354/meps080191

Holmer, M., Marbá, N., Diaz-Almela, E., Duarte, C. M., Tsapakis, M., and Danovaro, R. (2007). Sedimentation of organic matter from fish farms in oligotrophic Mediterranean assessed through bulk and stable isotope (δ13C and δ15N) analyses. Aquaculture 262, 268–280. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.09.033

Holmer, M., Marbá, N., Terrados, J., Duarte, C. M., and Fortes, M. D. (2002). Impacts of milkfish (Chanos chanos) aquaculture on carbon and nutrient fluxes in the Bolinao area, Philippines. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 44, 685–696. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(02)00048-6

Holmer, M., Wildish, D., and Hargrave, B. (2005). Organic enrichment from marine finfish aquaculture and effects on sediment biogeochemical processes. Handb. Environ. Chem. 5, 181–206. doi: 10.1007/b136010

Hou, L. J., Liu, M., Yang, Y., Ou, D. N., Lin, X., Chen, H., et al. (2009). Phosphorus speciation and availability in intertidal sediments of the Yangtze Estuary, China. Appl. Geochem. 24, 120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2008.11.008

Husa, V., Kutti, T., Ervik, A., Sjøtun, K., Hansen, P. K., and Aure, J. (2014). Regional impact from fin-fish farming in an intensive production area (Hardangerfjord, Norway). Mar. Biol. Res. 10, 241–252. doi: 10.1080/17451000.2013.810754

Hyun, J.-H., Kim, S.-H., Mok, J.-S., Cho, H., Lee, T., Vandieken, V., et al. (2017). Manganese and iron reduction dominate organic carbon oxidation in surface sediments of the deep Ulleung Basin, East Sea. Biogeosciences 14, 941–958. doi: 10.5194/bg-14-941-2017

Hyun, J.-H., Kim, S.-H., Mok, J.-S., Lee, J. S., An, S.-U., and Lee, W.-C. (2013). Impacts of long-line aquaculture of Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) on sulfate reduction and diffusive nutrient flux in the coastal sediments of Jinhae-Tongyeong, Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 74, 187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.07.004

Hyun, J.-H., Mok, J.-S., Cho, H.-Y., Kim, S.-H., Lee, K. S., and Kostka, J. E. (2009). Rapid organic matter mineralization coupled to iron cycling in intertidal mud flats of the Han River estuary. Yellow Sea. Biogeochem. 92, 231–245. doi: 10.1007/s10533-009-9287-y

Islam, M. S. (2005). Nitrogen and phosphorus budget in coastal and marine cage aquaculture and impacts of effluent loading on ecosystem: review and analysis towards model development. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 50, 48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.08.008

Jensen, H. S., McGlathery, K. J., Marino, R., and Howarth, R. W. (1998). Forms and availability of sediment phosphorus in carbonate sand of Bermuda seagrass beds. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 799–810. doi: 10.4319/lo.1998.43.5.0799

Jia, B., Tang, Y., Tian, L., Franz, L., Alewell, C., and Huang, J.-H. (2015). Impact of fish farming on phosphorus in reservoir sediments. Sci. Rep. 5:16617. doi: 10.1038/srep16617

Jørgensen, B. B. (1978). A comparison of methods for the quantification of bacterial sulfate reduction in coastal marine sediments, 1. Measurement with radiotracer techniques. Geomicrobiol J. 1, 11–28. doi: 10.1080/01490457809377721

Jørgensen, B. B., Findlay, A. J., and Pellerin, A. (2019). The biogeochemical sulfur cycle of marine sediments. Front. Microbiol. 10:849. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00849

Joshi, S. R., Kukkadapu, R. K., Burdige, D. J., Bowden, M. E., Sparks, D. L., and Jaisi, D. P. (2015). Organic matter remineralization predominates phosphorus cycling in the mid-bay sediments in the Chesapeake Bay. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 5887–5896. doi: 10.1021/es5059617

Karakassis, I., Tsapakis, M., and Hatziyanni, E. (1998). Seasonal variability in sediment profiles beneath fish farm cages in the Mediterranean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 162, 243–252. doi: 10.3354/meps162243

Kassila, J., Hasnaoui, M., Droussi, M., Loudiki, M., and Yahyaoui, A. (2001). Relation between phosphate and organic matter in fish-pond sediments of the Deroua fish farm (Béni-Mellal, Morocco): implications for pond management. Hydrobiologia 450, 57–70. doi: 10.1023/A:1017547600678

Kraal, P., Burton, E. D., Rose, A. L., Cheetham, M. D., Bush, R. T., and Sullivan, L. A. (2013). Decoupling between water column oxygenation and benthic phosphate dynamics in a shallow eutrophic estuary. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 3114–3121. doi: 10.1021/es304868t

Kraal, P., Burton, E. D., Rose, A. L., Kocar, B. D., Lockhart, R. S., Grice, K., et al. (2015). Sedimentary iron-phosphorus cycling under contrasting redox conditions in a eutrophic estuary. Chem. Geol. 392, 19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2014.11.006

Kraal, P., Dijkstra, N., Behrends, T., and Slomp, C. P. (2017). Phosphorus burial in sediments of the sulfide deep Black Sea: key roles for adsorption by calcium carbonate and apatite authigenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 204, 140–158. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2017.01.042

Kraal, P., and Slomp, C. P. (2014). Rapid and extensive alteration of phosphorus speciation during oxic storage of wet sediment samples. PLoS One 9:e96859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096859.g001

Lee, M. O., Kim, B. K., and Kim, J. K. (2015). Marine environmental characteristics of Goheung coastal waters during Cochlodinium polykrikoides blooms. J. Korean Soc. Mar. Environ. Eng. 18, 166–178. doi: 10.7846/JKOSMEE.2015.18.3.166

Lehtoranta, J., Ekholm, P., and Pitkänen, H. (2008). Eutrophication-driven sediment microbial processes can explain the regional variation in phosphorus concentrations between Baltic Sea sub-basins. J. Mar. Syst. 74, 495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2008.04.001

Lehtoranta, J., Ekholm, P., and Pitkänen, H. (2009). Coastal eutrophication thresholds: a matter of sediment microbial processes. Ambio 38, 303–308. doi: 10.1579/09-A-656.1

Li, Y.-H., and Gregory, S. (1974). Diffusion of ions in sea water and deep-sea sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 38, 703–714. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(74)90145-8

Lomnitz, U., Sommer, S., Dale, A. W., Löscher, C. R., Noffke, A., Wallmann, K., et al. (2016). Benthic phosphorus cycling in the Peruvian oxygen minimum zone. Biogeosciences 13, 1367–1386. doi: 10.5194/bg-13-1367-2016

Matijević, S., Kušpilić, G., Kljaković-Gašpić, Z., and Bogner, D. (2008). Impact of fish farming on the distribution of phosphorus in sediments in the middle Adriatic area. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 56, 535–548. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.11.017

Middelburg, J. J., and Levin, L. A. (2009). Coastal hypoxia and sediment biogeochemistry. Biogeosciences 6, 1273–1293. doi: 10.5194/bgd-6-3655-2009

Ministery of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF) (2016). Establishment of Criteria for Fishery Environments. Sejong: MOF.

Morata, T., Falco, S., Gadea, I., Sospedra, J., and Rodilla, M. (2015). Environmental effects of a marine fish farm of gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) in the NW Mediterranean Sea on water column and sediment. Aquacult. Res. 46, 59–74. doi: 10.1111/are.12159

Nielsen, O. I., Kristensen, E., and Macintosh, D. J. (2003). Impact of fiddler crabs (Uca spp.) on rates and pathways of benthic mineralization in deposited mangrove shrimp pond waste. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 289, 59–81. doi: 10.1016/S0022-098(03)00041-8

NIFS (2013). National Institute of Fisheries Science Report on the Assessment of Fishery Environment and Establishment of Guidelines. Busan: NIFS, 92.

Olsen, L. M., Holmer, M., and Olsen, Y. (2008). Perspectives of Nutrient Emission from Fish Aquaculture in Coastal Waters. Literature Review with Evaluated State of Knowledge. FHF Project No. 542014, Vol. 66. FHF-Fishery and Aquaculture Industry Research Fund, doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.1273.8006

Parsons, T. R., Maita, Y., and Lalli, C. M. (1984). A Manual of Chemical and Biological Methods for Seawater Analysis. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 173. doi: 10.1016/C2009-0-07774-5

Phillips, E. J. P., and Lovley, D. R. (1987). Determination of Fe(III) and Fe(II) in oxalate extracts of sediments. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 51, 938–941. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1987.03615995005100040021x

Porrello, S., Tomassetti, P., Manzueto, L., Finoia, M. G., Persia, E., Mercatali, I., et al. (2005). The influence of marine cages on the sediment chemistry in the Western Mediterranean Sea. Aquaculture 249, 145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.02.042

Price, C., Black, K. D., Hargrave, B. T., and Morris, J. A. Jr. (2015). Marine cage culture and the environment: effects on water quality and primary production. Aquacult. Environ. Interact. 6, 151–174. doi: 10.3354/aei00122

Ro, Y. J., Jun, W. S., Jung, K. Y., and Eom, H. M. (2007). Numerical modeling of tide and tidal current in the Kangjin Bay, South Sea, Korea. Ocean Sci. J. 42, 153–163. doi: 10.1007/BF03020919

Rozan, T. F., Taillefert, M., Trouwborst, R. E., Glazer, B. T., Ma, S., Herszage, J., et al. (2002). Iron-sulfur-phosphorus cycling in the sediments of a shallow coastal bay: implications for sediment nutrient release and benthic macroalgal blooms. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47, 1346–1354. doi: 10.4319/lo.2002.47.5.1346

Ruiz, J. M., Pérez, M., and Romero, J. (2001). Effects of fish farm loadings on seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) distribution, growth and photosynthesis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 42, 749–760. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(00)00215-0

Ruttenberg, K. C. (2003). “The global phosphorus cycle,” in Treatise on Geochemistry, Vol. 8, eds W. H. Schlesinger, H. D. Holland, and K. K. Turekian (New York, NY: Elsevier), 585–643. doi: 10.1016/B0-08-043751-6/08153-6

Ruttenberg, K. C., Ogawa, N. O., Tamburini, F., Briggs, R. A., Colasacco, N. D., and Joyce, E. (2009). Improved, high-throughput approach for phosphorus speciation in natural sediments via the SEDEX sequential extraction method. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 7, 319–333. doi: 10.4319/lom.2009.7.319

Schenau, S. J., and De Lange, G. J. (2000). A novel chemical method to quantify fish debris in marine sediments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45, 963–971. doi: 10.4319/lo.2000.45.4.0963

Schenau, S. J., and De Lange, G. J. (2001). Phosphorus regeneration vs. burial in sediments of the Arabian Sea. Mar. Chem. 75, 201–217. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4203(01)00037-8

Schenau, S. J., Slomp, C. P., and De Lange, G. J. (2000). Phosphogenesis and active phosphorite formation in sediments from the Arabian Sea oxygen minimum zone. Mar. Geol. 169, 1–20. doi: 10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00083-9

Schoffelen, N. J., Mohr, W., Ferdelman, T. G., Littmann, S., Duerschlag, J., Zubkov, M. V., et al. (2018). Single-cell imaging of phosphorus uptake shows that key harmful algae rely on different phosphorus sources for growth. Sci. Rep. 8:17182. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35310-w

Slomp, C. P. (2011). “Phosphorus cycling in the estuarine and coastal zones: sources, sinks, and transformations,” in Treatise on Estuarine and Coastal Science, Vol. 5, eds E. Wolanski and D. S. McLusky (Waltham, MA: Academic Press), 201–229. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-374711-2.00506-4

Slomp, C. P., Epping, E. H. G., Helder, W., and Van Raaphorst, W. (1996). A key role for iron-bound phosphorus in authigenic apatite formation in North Atlantic continental platform sediments. J. Mar. Res. 54, 1179–1205. doi: 10.1357/0022240963213745

Slomp, C. P., Mort, H. P., Jilbert, T., Reed, D. C., Gustafsson, B. G., and Wolthers, M. (2013). Coupled dynamics of iron and phosphorus in sediments of an oligotrophic coastal basin and the impact of anaerobic oxidation of methane. PLoS One 8:e62386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062386

Soto, B. D., and Norambuena, F. (2004). Evaluation of salmon farming effects on marine systems in the inner seas of southern Chile: a large-scale mensurative experiment. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 20, 493–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0426.2004.00602.x

Stal, L. J., Albertano, P., Bergman, B., von Bröckel, K., Gallon, J. R., Hayes, P. K., et al. (2003). BASIC: Baltic Sea cyanobacteria. An investigation of the structure and dynamics of water blooms of cyanobacteria in the Baltic Sea-responses to a changing environment. Cont. Shelf Res. 23, 1695–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2003.06.001

Stigebrandt, A., and Andersson, A. (2020). The eutrophication of the Baltic Sea has been boosted and perpetuated by a major internal phosphorus source. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:572994. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.572994

Stookey, L. L. (1970). Ferrozine-a new spectrophotometric reagent for iron. Anal. Chem. 42, 245–252. doi: 10.1139/v84-121

Thamdrup, B. (2000). Bacterial manganese and iron reduction in aquatic sediments. Adv. Microb. Ecol. 16, 41–84. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4187-5_2

Thamdrup, B., and Canfield, D. E. (1996). Pathways of carbon oxidation in continental margin sediments off central Chile. Limnol. Oceanogr. 41, 1629–1650. doi: 10.4319/lo.1996.41.8.1629

Thamdrup, B., Fossing, H., and Jorgensen, B. B. (1994). Manganese, iron, and sulfur cycling in a coastal marine sediment, Aarhus Bay, Denmark. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 5115–5129. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(94)90298-4

Thamdrup, B., Rosselló-Mora, R., and Amann, R. (2000). Microbial manganese and sulfate reduction in Black Sea shelf sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 2888–2897. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.7.2888-2897.2000

Thomas, C. R., and Smayda, T. J. (2008). Red tide blooms of Cochlodinium polykrikoides in a coastal cove. Harmful Algae 7, 308–317. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2007.12.005

Tsandev, I., Reed, D. C., and Slomp, C. P. (2012). Phosphorus diagenesis in deep-sea sediments: sensitivity to water column conditions and global scale implications. Chem. Geol. 330-331, 127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.08.012

Tyrrell, T. (1999). The relative influences of nitrogen and phosphorus on oceanic primary production. Nature 400, 525–531. doi: 10.1038/22941

Valdemarsen, T., Bannister, R. J., Hansen, P. K., Holmer, M., and Ervik, A. (2012). Biogeochemical malfunctioning in sediments beneath a deep-water fish farm. Environ. Pollut. 170, 15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.06.007

Valdemarsen, T., Kristensen, E., and Holmer, M. (2009). Metabolic threshold and sulfide-buffering in diffusion controlled marine sediments impacted by continuous organic enrichment. Biogeochemistry 95, 335–353. doi: 10.1007/s10533-009-9340-x

van der Zee, C., Slomp, C. P., and van Raaphorst, W. (2002). Authigenic P formation and reactive P burial in sediments of the Nazaré canyon on the Iberian margin (NE Atlantic). Mar. Geol. 185, 379–392. doi: 10.1016/S0025-3227(02)00189-5

Viktorsson, L., Ekeroth, N., Nilsson, M., Kononets, M., and Hall, P. O. J. (2013). Phosphorus recycling in sediments of the central Baltic Sea. Biogeosciences 10, 3901–3916. doi: 10.5194/bg-10-3901-2013

Wang, X., Olsen, L. M., Reitan, K. I., and Olsen, Y. (2012). Discharge of nutrient wastes from salmon farms: environmental effects, and potential for integrated multi-trophic aquaculture. Aquacult. Environ. Interact. 2, 267–283. doi: 10.3354/aei00044

Wu, R. S. S. (2001). “Environmental impacts of marine fish farming and their mitigation. Responsible Aquaculture Development in Southeast Asia,” in Proceedings of the Seminar-Workshop on Aquaculture Development in Southeast Asia organized by the SEAFDEC Aquaculture Department, 12-14 October 1999, Iloilo City, Philippines, ed. L. M. B. Garcia (Iloilo: SEAFDEC Aquaculture Department), 157–172.

Keywords: biogenic apatite P, benthic nutrient flux, P regeneration, aquaculture, phosphorus speciation, sulfate reduction, iron reduction

Citation: Mok J-S, Choi A, Kim B, An S-U, Lee W-C, Kim HC, Kim J, Yoon C and Hyun J-H (2021) Phosphorus Dynamics Associated With Organic Carbon Mineralization by Reduction of Sulfate and Iron in Sediment Exposed to Fish Farming. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:645449. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.645449

Received: 23 December 2020; Accepted: 17 August 2021;

Published: 21 September 2021.

Edited by:

Varenyam Achal, Guangdong Technion-Israel Institute of Technology (GTIIT), ChinaReviewed by:

Tieyu Wang, Shantou University, ChinaCintia Organo Quintana, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark

Peter Kraal, Department of Ocean Systems, Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ), Netherlands

Copyright © 2021 Mok, Choi, Kim, An, Lee, Kim, Kim, Yoon and Hyun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jung-Ho Hyun, aHl1bmpoQGhhbnlhbmcuYWMua3I=; Cheolho Yoon, Y2h5b29uQGtic2kucmUua3I=

Jin-Sook Mok

Jin-Sook Mok Ayeon Choi

Ayeon Choi Bomina Kim1

Bomina Kim1 Jonguk Kim

Jonguk Kim Cheolho Yoon

Cheolho Yoon Jung-Ho Hyun

Jung-Ho Hyun