- 1Norwegian Polar Institute, Fram Centre, Tromsø, Norway

- 2School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, United Kingdom

- 3Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany

- 4Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Plymouth, United Kingdom

The Barents Sea is a hotspot for environmental change due to its rapid warming, and information on dietary preferences of zooplankton is crucial to better understand the impacts of these changes on food-web dynamics. We combined lipid-based trophic marker approaches, namely analysis of fatty acids (FAs), highly branched isoprenoids (HBIs) and sterols, to compare late summer (August) and early winter (November/December) feeding of key Barents Sea zooplankters; the copepods Calanus glacialis, C. hyperboreus and C. finmarchicus and the amphipods Themisto libellula and T. abyssorum. Based on FAs, copepods showed a stronger reliance on a diatom-based diet. Phytosterols, produced mainly by diatoms, declined from summer to winter in C. glacialis and C. hyperboreus, indicating the strong direct linkage of their feeding to primary production. By contrast, C. finmarchicus showed evidence of year-round feeding, indicated by the higher winter carnivory FA ratios of 18:1(n-9)/18:1(n-7) than its larger congeners. This, plus differences in seasonal lipid dynamics, suggests varied overwintering strategies among the copepods; namely diapause in C. glacialis and C. hyperboreus and continued feeding activity in C. finmarchicus. Based on the absence of sea ice algae-associated HBIs (IP25 and IPSO25) in the three copepod species during both seasons, their carbon sources were likely primarily of pelagic origin. In both amphipods, increased FA carnivory ratios during winter indicated that they relied strongly on heterotrophic prey during the polar night. Both amphipod species contained sea ice algae-derived HBIs, present in broadly similar concentrations between species and seasons. Our results indicate that sea ice-derived carbon forms a supplementary food rather than a crucial dietary component for these two amphipod species in summer and winter, with carnivory potentially providing them with a degree of resilience to the rapid decline in Barents Sea (winter) sea-ice extent and thickness. The weak trophic link of both zooplankton taxa to sea ice-derived carbon in our study likely reflects the low abundance and quality of ice-associated carbon during late summer and the inaccessibility of algae trapped inside the ice during winter.

Introduction

In Arctic marine ecosystems, primary and secondary production, and subsequently its availability to higher trophic levels, are subject to a strong seasonality (Wassmann and Slagstad, 1993; Weydmann et al., 2013). Zooplankton in the Barents Sea are well adapted to interannual and seasonal environmental changes and fluctuations in food supply, from a low sea-ice cover or open water conditions and high incident irradiance during the summer months ranging to a consolidated sea-ice cover and extremely low light levels during the winter period (Conover and Huntley, 1991; Hagen, 1999; Bandara et al., 2016). Despite great inter-annual variability (Årthun et al., 2012; Herbaut et al., 2015), especially during the winter months (December throughout February), the Barents Sea has experienced a strong decline in sea-ice extent and concentration over the last decades, mostly due to higher water temperatures (Onarheim and Årthun, 2017; Barton et al., 2018; Årthun et al., 2019).

During spring and early summer, the Barents Sea is highly productive (Stramska and Bialogrodzka, 2016), particularly in the marginal ice zone (MIZ) (Falk-Petersen et al., 2007). However, productivity varies significantly depending on oceanographic conditions, nutrient concentrations and sea-ice cover (Sakshaug and Slagstad, 1992; Falk-Petersen et al., 2000b; Reigstad et al., 2002; Hop et al., 2019). Nevertheless, phytoplankton carbon is generally considered to be sufficient to meet the energetic requirements of the food web (Verity et al., 2002; Tamelander et al., 2006; Wassmann et al., 2006; Kohlbach et al., 2021). Additionally, sea ice-associated (sympagic) primary production can provide an alternative or supplemental source of carbon for some zooplankton taxa, early in the season (Søreide et al., 2008; Gradinger, 2009) and also during summer (Scott et al., 1999; Assmy et al., 2013; Kohlbach et al., 2016, 2021; Brown et al., 2017). During winter, primary production levels in the water column (Kvernvik et al., 2018) and in sea ice are practically zero (Mikkelsen et al., 2008), and the ice algal biomass trapped in internal ice layers might be difficult to access for grazers (Van Leeuwe et al., 2018). Compared to sea ice in the Arctic Ocean, the Barents Sea winter sea-ice is relatively thin and has been identified as being particularly affected by sea-ice loss (Francis and Hunter, 2007; Onarheim and Årthun, 2017). The reduced expansion of winter sea ice and continuing thinning of the ice cover has consequences for winter-active species that depend on the sympagic habitat for shelter and foraging (Hop et al., 2000; Poltermann, 2001; Werner and Gradinger, 2002; Werner and Auel, 2005), but little is known about the impact on food-web interactions.

Zooplankton are a vital link between primary production and higher tropic levels, and information on their lifestyle and feeding behavior is crucial to understand the functioning of marine ecosystems under present conditions and future change (Falk-Petersen et al., 2007; Atkinson et al., 2012; Pecuchet et al., 2020). The lower trophic levels of the Barents Sea food-web are dominated by Calanus copepods (Aarflot et al., 2018), with C. glacialis being dominant in Arctic shelf waters and the boreal C. finmarchicus in the warmer Atlantic sector. Both of these species are generally more abundant in the sampling region (Figure 1) than the larger C. hyperboreus that prefers deeper water masses (Hirche and Mumm, 1992; Hirche, 1997). Themisto amphipods, such as T. libellula and T. abyssorum, are major contributors to the macrozooplankton biomass in the study region (Dalpadado et al., 2001; Havermans et al., 2019). Both taxa serve as important prey for fish, seabirds and whales (Hop and Gjøsæter, 2013; Jakubas et al., 2016; Haug et al., 2017; Eriksen et al., 2020), but show significant differences in life-history strategies and feeding modes.

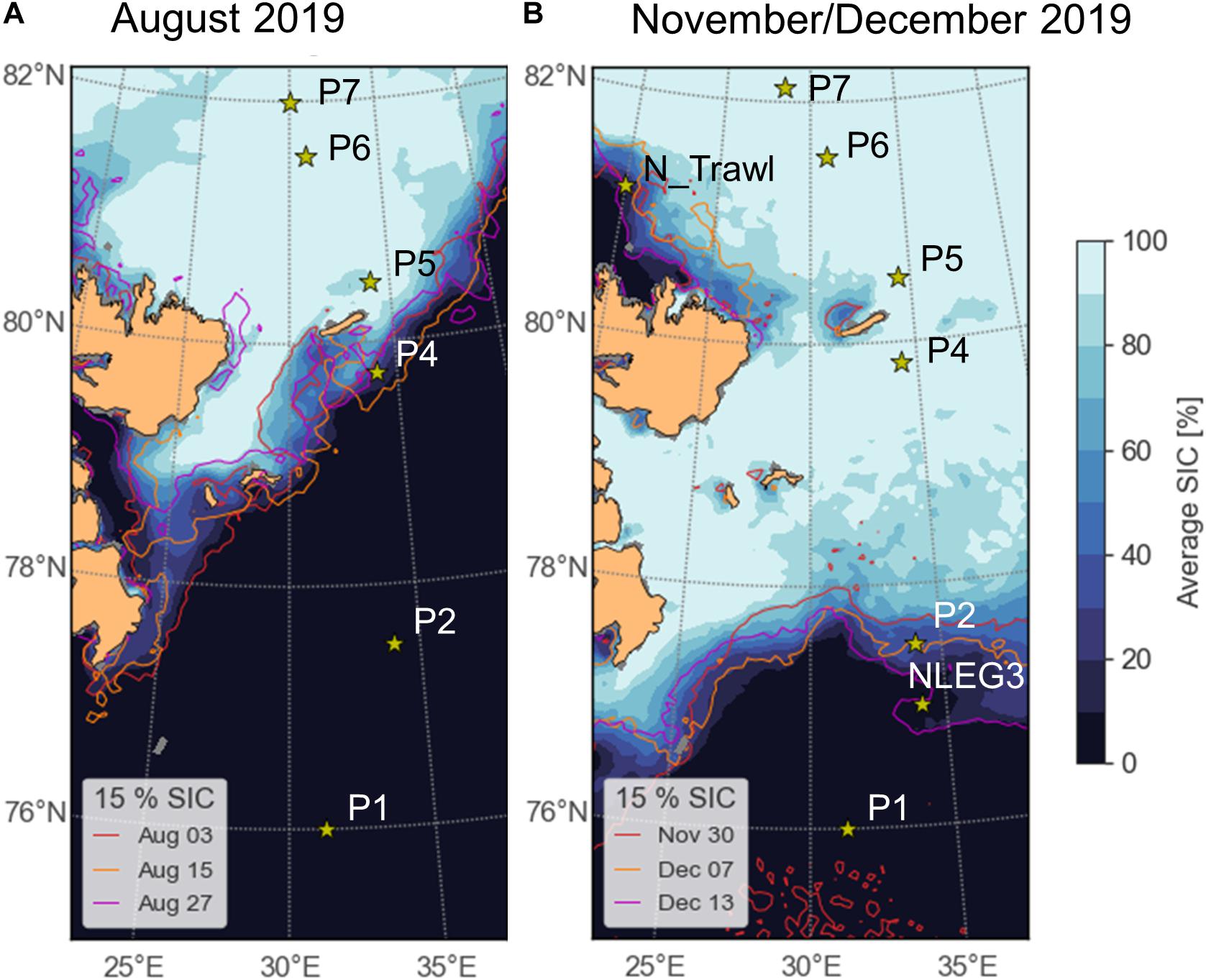

Figure 1. Sampling area with sampling stations during Nansen Legacy cruises (A) Q3 (polar day, August 2019) and (B) Q4 (polar night, November/December 2019). Sea-ice concentrations (SIC%) are shown for the beginning, mid and end of sampling for each sampling campaign, respectively. SIC data acquired from Bremen University (http://www.iup.uni-bremen.de:8084/amsr2/) (Spreen et al., 2008). More detailed information on sampling stations can be found in Kohlbach et al. (2021).

During winter, some Arctic zooplankton switch from herbivorous to omnivorous or carnivorous diets (Werner and Auel, 2005), while others rely at least partly on their lipid stores built up during the productive season (Hagen and Auel, 2001). The latter is the case for diapausing Calanus copepods (Falk-Petersen et al., 2009; Choi et al., 2020), and has also been described for Antarctic calanoid copepods (Atkinson, 1998). Governed by their energy reserves, Calanus hyperboreus, for example, has the ability to reproduce during winter (Melle and Skjoldal, 1998; Hirche, 2013; Halvorsen, 2015), in contrast to C. finmarchicus, which is not able to reproduce successfully in the high Arctic (Hirche and Kosobokova, 2007). Besides decreasing their metabolic activity, there are indications that Arctic Calanus spp. remain actively feeding also during winter (Søreide et al., 2008; Hobbs et al., 2020) with a possible increase in carnivory (Cleary et al., 2017), which would be in line with the recently suggested surprisingly high biological activity during the Arctic polar night (Berge et al., 2015, 2020). Early in the season, ice-associated food can be an important carbon source for the reproduction of Calanus glacialis while pelagic production is still low (Wold et al., 2011; Daase et al., 2013; Durbin and Casas, 2014), and all three Calanus species rely on phytoplankton (mostly diatoms) during summer (Campbell et al., 2009). The potential importance of sea-ice algae for copepods that do not perform diapause during winter is unclear (Cleary et al., 2017); thus far, information on their carbon source composition during the dark period is mostly restricted to late autumn (Scott et al., 2000) and the winter-spring transition (Wold et al., 2011). Other species with a more omnivorous/carnivorous lifestyle, such as Themisto amphipods, are less impacted by the lower algal productivity and can thus remain active during winter (Hagen and Auel, 2001; Kraft et al., 2013); they have a pelagic lifestyle but are often encountered at the sea ice-water interface (David et al., 2015) and are capable of utilizing sympagic carbon (Wang et al., 2015; Kohlbach et al., 2016, 2021).

Most polar zooplankton are opportunistic feeders with a pronounced dietary plasticity (e.g., Berge et al., 2020), capable of utilizing carbon of different origin and from multiple trophic positions. Thus, some can switch from a pelagic lifestyle during summer to a stronger reliance on sympagic food sources during winter, as illustrated for Antarctic copepods and amphipods (Kohlbach et al., 2018). A similar seasonal change from pelagic to sympagic carbon source composition could be expected for Arctic crustaceans, provided they feed to some extent throughout the winter and can actually access the ice-associated carbon. Preferred dietary sources of marine animals and their seasonality can be elucidated from the composition of lipid-based trophic markers (Leu et al., 2020). Their stability when transferred along the marine food chain makes them valuable trophic proxies in disentangling food-web relationships and revealing the importance of varying carbon sources (e.g., Scott et al., 1999; Iverson, 2009). Certain fatty acids (FAs), called trophic marker FAs, are produced by (pelagic and sympagic) diatoms [e.g., 16:1(n-7), 20:5(n-3)] and others by (pelagic and sympagic) dinoflagellates [18:4(n-3), 22:6(n-3)] (Dalsgaard et al., 2003), and can thus indicate the importance of diatom-versus dinoflagellate-derived food in a consumer. FAs can be incorporated into membrane lipids for the structural support of cell membranes and somatic growth, while others can be used as energy reserves in the form of storage lipids (Stübing et al., 2003; Falk-Petersen et al., 2009; Parrish, 2009; Ruess and Müller-Navarra, 2019). When food is abundant, marine animals accumulate large lipid reserves, which can be utilized for energy-intensive reproduction processes and to ensure survival during periods when food is not sufficiently abundant (Lee et al., 2006). Thus, the distribution of membrane and storage lipids in an animal’s body can give information on their nutritional condition and overwintering strategies (Kattner et al., 1994). Highly branched isoprenoid (HBI) lipids and sterols can further complement food-web studies (e.g., Schmidt et al., 2018; Kohlbach et al., 2021). Different HBIs allow for the differentiation of sympagic (IP25 and IPSO25) and pelagic (HBIs III and IV) carbon (Belt et al., 2012; Brown and Belt, 2012; Belt, 2018), whereas phyto- and animal-derived sterols allow conclusions about the degree of carnivory of a species (Drazen et al., 2008; Ruess and Müller-Navarra, 2019).

Based on the absence of sea ice algae-produced HBIs in their carbon pool, Calanus copepods collected during August 2019 in the Barents Sea had no verifiable trophic interaction with the sea-ice system, while these sea ice-produced metabolites were detected in Themisto amphipods during this period of the year (Kohlbach et al., 2021). Building on these previous results, the present study aims to assess species-specific changes in lipid content and lipid-based trophic markers indicating diet-source variability of these invertebrates during the transition from late summer (August 2019) to early winter (November/December 2019).

Materials and Methods

Sampling

As a contribution to the Norwegian Nansen Legacy project (arvenetternansen.com), samples were collected during the summer expedition Q3 (5 to 27 August 2019) and the winter expedition Q4 (28 November to 17 December 2019) onboard RV Kronprins Haakon in the northern Barents Sea (Table 1 and Figure 1). During Q3, sampling was carried out from south to north, while on Q4 the transect was sampled from north to south. Detailed information about sampling during Q3 can be found in Kohlbach et al. (2021).

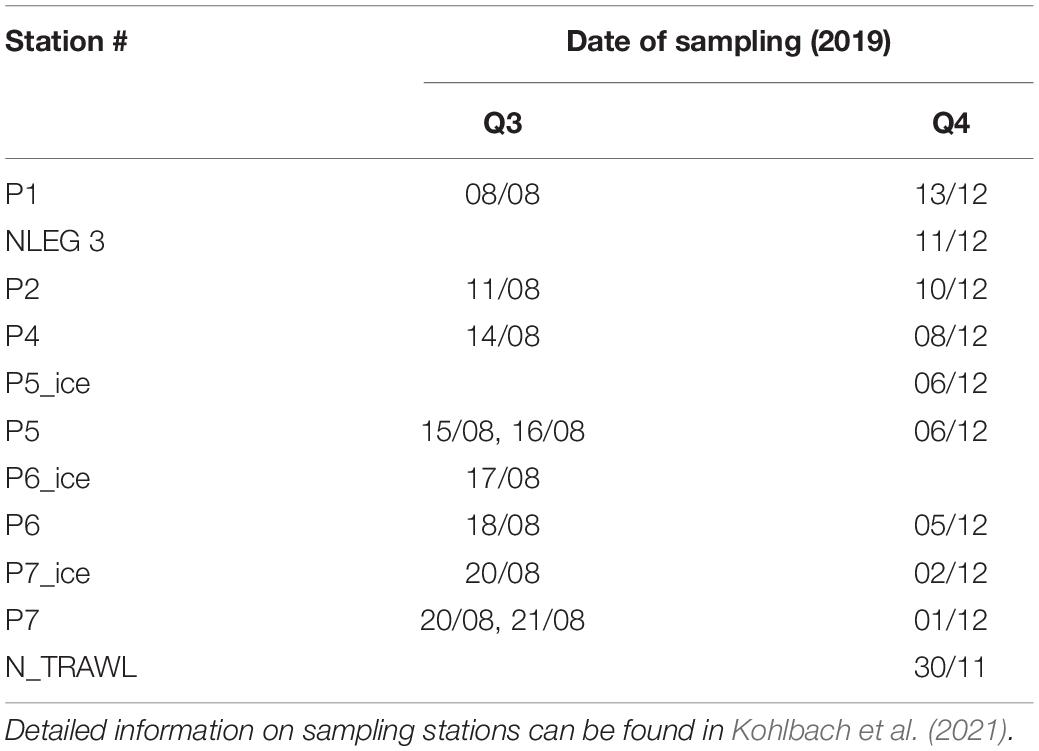

Table 1. Station information for RV Kronprins Haakon seasonal Nansen Legacy cruises Q3 during August 2019 and Q4 during November/December 2019 in the Barents Sea.

During Q3, Calanus copepods (C. glacialis Jaschnov, 1955; C. hyperboreus Krøyer, 1838; C. finmarchicus Gunnerus, 1770) and Themisto amphipods (Themisto libellula Liechtenstein, 1822; T. abyssorum Boeck, 1870) were collected at six stations (Kohlbach et al., 2021) and during Q4 at eight stations (Table 1 and Figure 1) with MIK nets (1200 μm with 500 μm cod end), WP3 nets (1000 μm), Macroplankton trawls (multiple mesh sizes, 8 mm bottom of the net), Bongonets (180 μm), Multinets (180 μm) and WP2 nets (90 μm). Samples were sorted into species (Supplementary Figures 1,2) and stage/size groups (Table 2) onboard the ship and immediately frozen at −80°C until further processing. The different Calanus species were differentiated based on morphology and prosome lengths according to Kwasniewski et al. (2003). Small species/individuals were pooled by stage/size group in order to obtain sufficient sample material for analyses (Table 2).

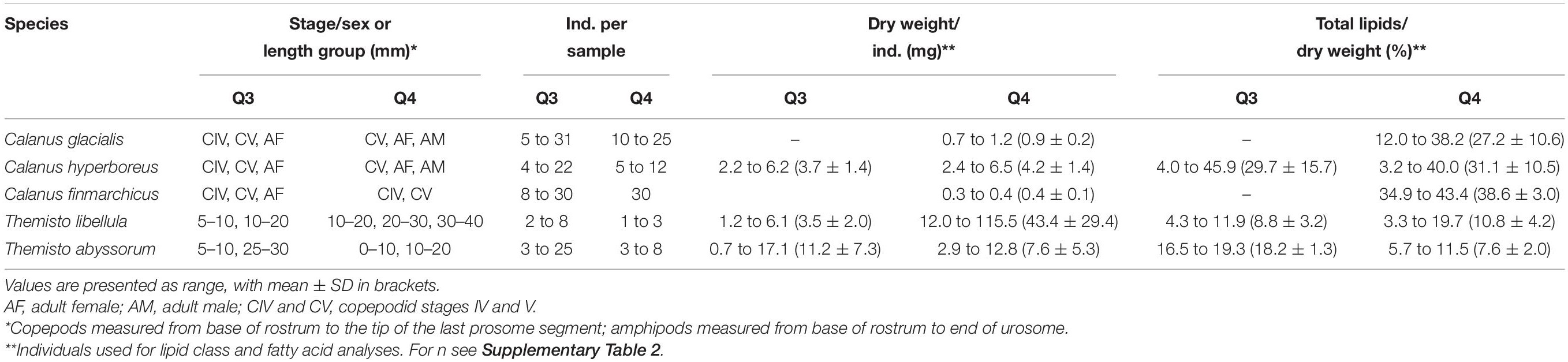

Table 2. Zooplankton collected during the RV Kronprins Haakon expeditions Q3 (August 2019) and Q4 (November/December 2019) in the Barents Sea.

During Q3, pelagic particulate organic matter (PPOM) was collected at six stations (P1, P2, P4, P5, P6, and P7) with Niskin bottles attached to a CTD rosette at the depth of the chlorophyll (Chl) a maximum (between 14 and 73 m). During Q4, water samples were collected at five stations (P1, P4, P5, P6, and P7) at 20 m depth. Volumes of 1.2 to 3 L of seawater were filtered via a vacuum pump through pre-combusted Whatman GF/F filters (3 h, 550°C) and PPOM filters were stored at −80°C until further processing. Chlorophyll a concentrations reached up to 2.6 μg L–1 during summer and were generally below 0.05 μg L–1 during winter (Vader et al., 2021).

During both sampling campaigns, ice-associated POM (IPOM) was collected at two stations, respectively, (Q3: P6_ice, P7_ice; Q4: P5_ice, P7_ice). The bottom 10 cm of the ice cores were melted in the dark without the addition of filtered seawater. For each sample, between 570 and 640 mL of melted ice sample was filtered by a vacuum pump through pre-combusted 47 mm GF/F filters and filters were stored at −80°C until further processing. Mean Chl a concentrations (n = 2 each) in the bottom 3 cm of the sea ice were higher during the summer sampling (P6_ice: 0.4 μg L–1, P7_ice: 2.3 μg L–1) compared to the winter ice cores (P5_ice: 0.04 μg L–1, P7_ice: 0.3 μg L–1; Vader et al., 2021).

Lipid Classes and Fatty Acids

Lipid classes and FAs were analyzed at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Bremerhaven, Germany. Details on sample preparation, analysis and lab equipment can be found in Kohlbach et al. (2021). Briefly, total lipids were extracted from the freeze-dried samples using a modified procedure from Folch et al. (1957) with dichloromethane/methanol (2:1, v/v). Lipid class analysis of the zooplankton was performed directly on the extracted lipids (Graeve and Janssen, 2009) via high performance liquid chromatography. Lipids were separated into neutral (= storage lipids) and polar lipid classes (= membrane lipids; Supplementary Table 1).

Total lipids were converted into fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) by transesterification in methanol, containing 3% concentrated sulfuric acid, and separated via gas chromatography (Kattner and Fricke, 1986). Total lipids were estimated using an internal standard (C23:0). FAs are expressed by the nomenclature A:Bn-X, where A represents the number of carbon atoms, B the amount of double bonds, and X gives the position of the first double bond starting from the methyl end of the carbon chain. The proportions of individual FAs are expressed as mass percentage of the total FA content.

Dry weights and percentage total lipids per dry weight are summarized in Table 2.

To study changes in carbon-source composition of the zooplankton species from summer to winter, we investigated relative proportions of marker FAs that can inform about carbon-source preferences of the consumers. The FAs 16:1(n-7), 16:4(n-1), and 20:5(n-3) are mainly produced by diatoms (= diatom-associated FAs), and the FAs 18:4(n-3) and 22:6(n-3) (= dinoflagellate-associated FAs) are predominantly produced by dinoflagellates and the prymnesiophyte Phaeocystis (Falk-Petersen et al., 1998; Reuss and Poulsen, 2002; Dalsgaard et al., 2003). FA ratios of 16:1(n-7)/16:0, ΣC16/ΣC18 and 20:5(n-3)/22:6(n-3) > 1 can indicate a dominance of diatom-produced versus dinoflagellate-produced carbon in an algal community or carbon pool of a consumer. Calanus spp. biosynthesize the monounsaturated long-chained FAs 20:1 and 22:1 (all isomers), which then can indicate the importance of Calanus spp. as a food source for a consumer (Sargent and Falk-Petersen, 1988; Falk-Petersen et al., 1990). The FA 18:1(n-7) derives from the elongation of 16:1n-7 in algae (Falk-Petersen et al., 1990) whereas 18:1(n-9) can be produced by the consumers (Graeve et al., 1994; Nyssen et al., 2005), and ratios of 18:1(n-9)/18:1(n-7) (carnivory index) can further inform about the degree of carnivory in a consumer (Graeve et al., 1997; Falk-Petersen et al., 2000a; Auel et al., 2002).

PPOM was analyzed on triplicates for each station (Q3: total n = 18, Q4: total n = 15). Q3 IPOM was analyzed on duplicates (total n = 4) and Q4 IPOM on individual samples (total n = 2).

Highly Branched Isoprenoids and Sterols

Highly branched isoprenoids and sterols were analyzed at the University of Plymouth, United Kingdom. Details on sample preparation, analysis and lab equipment can be found in Kohlbach et al. (2021). Briefly, total lipids were extracted with chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) and saponified with 20% potassium hydroxide in water/methanol (1:9, v/v). Non-saponifiable lipids were purified by open column chromatography (SiO2). The sea ice algae-associated HBIs IP25 (m/z 350.3) and IPSO25 (m/z 348.3), and the pelagic HBIs III and IV (m/z 346.3), were analyzed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS). HBIs were quantified by integrating individual ion responses in single-ion monitoring mode, and normalizing these to the corresponding peak area of the internal standard and an instrumental response factor obtained from purified standards (Belt et al., 2012).

Sterols were eluted from the same silica column using hexane:methylacetate (4:1,v/v). Sterol fractions were derivatized using N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) and analyzed by GC-MS. Individual sterols were identified by comparison of the mass spectra of their trimethylsilyl-ethers with published data (Belt et al., 2018). The main identifiable sterols were those commonly synthesized by plants (hereafter: phytosterols): brassicasterol (24-methylcholesta-5,22E-dien-3β–ol; m/z 470), sitosterol (24-ethylcholest-5-en-3β–ol; m/z 396), chalinasterol (24-methylcholesta-5,24(28)-dien-3β–ol; m/z 470) and campesterol (24-methylcholest-5-en-3β–ol; m/z 382) and those that are synthesized by both plants and animals (hereafter: zoosterols): cholesterol (Cholest-5-en-3β–ol; m/z 458), desmosterol (Cholesta-5,24-dien-3β–ol; m/z 343) and dehydrocholesterol (Cholesta-5,22E-dien-3β–ol; m/z 327).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significance of differences in trophic markers between summer and winter in POM and the zooplankton were assessed using unpaired Student’s t-tests. A statistical threshold of α = 0.05 was chosen, and results with p ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. All measures of statistical variation are reported as means ±1 SD. Prior to statistical analysis, the data were verified for normality of distribution. For testing, lipid class and FA data were transformed by applying an arcsine square root function to meet normality requirements for parametric statistics (Legendre and Legendre, 2012). All statistical analyses and data visualization were run in R v.3.4.3 (R Core Team, 2017), using the R package ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016).

Results

Variability in Zooplankton Lipid Class Composition

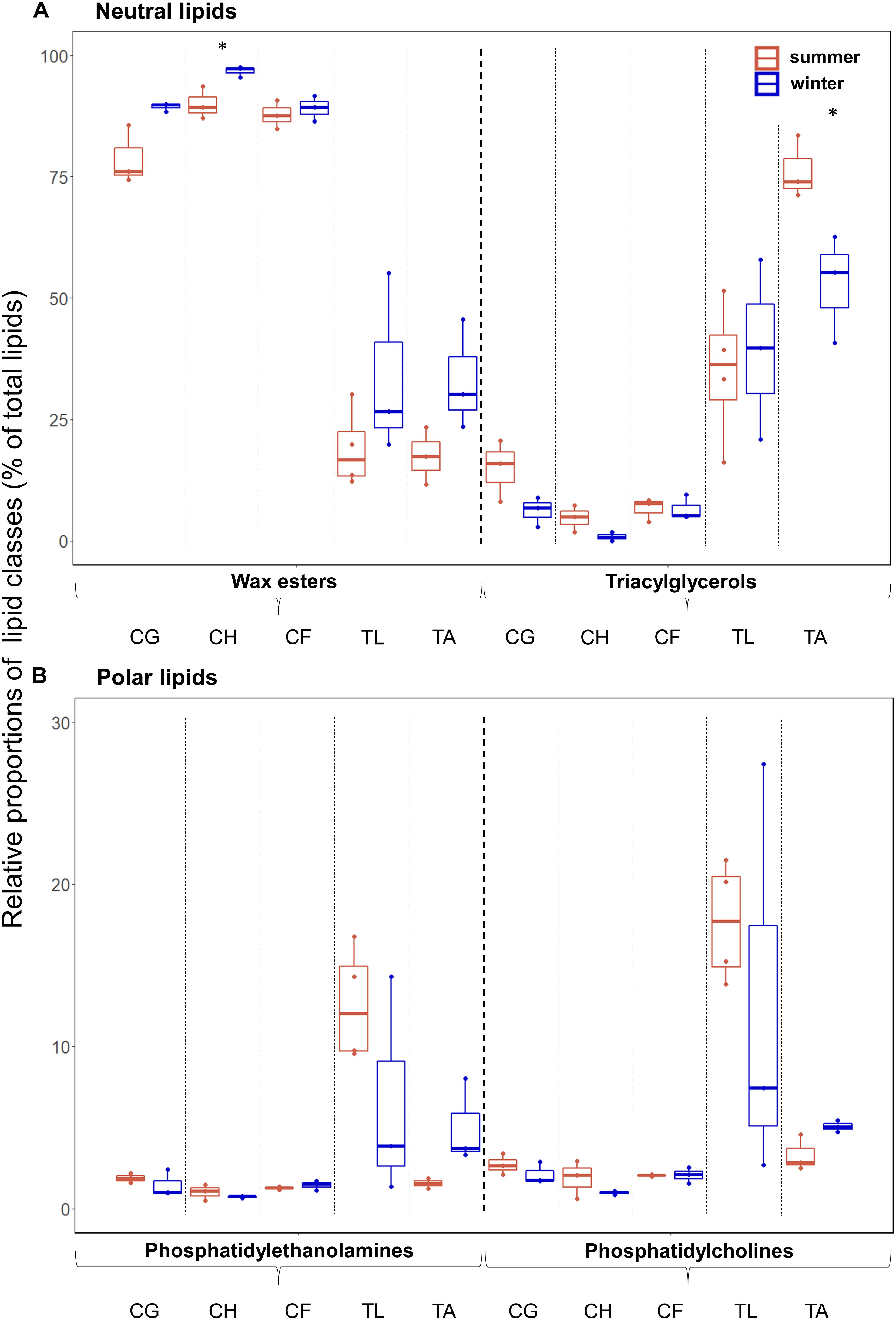

In all species, the relative proportions of the neutral lipids, mainly wax esters (WEs) and triacylglycerols (TAGs), during summer (mean 66% in T. libellula to 97% in C. hyperboreus) and winter (mean 79% in T. libellula to 98% in C. hyperboreus) exceeded the proportions of the polar lipids, mainly phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) and phosphatidylcholines (PCs) during summer (mean 3% in C. hyperboreus and C. finmarchicus to 34% in T. libellula) and winter (mean 2% in C. hyperboreus to 21% in T. libellula). The lipid content of the Calanus copepods consisted almost entirely of WEs during both seasons (mean ≥79%; Figure 2). In T. libellula, WEs and TAGs contributed equally to the neutral lipid fraction in winter, while in T. abyssorum, TAGs had higher relative contributions than WEs during both summer and winter (Figure 2A). In all species, the proportions of WEs were higher during winter compared to summer (significant difference in C. hyperboreus). In contrast, proportions of TAGs were higher during summer compared to winter in all species except for T. libellula (significant difference in T. abyssorum). The relative contributions of the polar lipids PC and PE showed no significant seasonal differences within each species, but were somewhat higher during winter compared to summer in T. abyssorum (Figure 2B). Relative proportions of individual lipid classes can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 2. Lipid class composition (as % of total lipids) during summer (Q3) and winter (Q4) in the zooplankton. (A) Neutral lipids and (B) polar lipids in the copepods Calanus glacialis (CG; Q3: n = 3, Q4: n = 3), C. hyperboreus (CH; Q3: n = 3, Q4: n = 3), C. finmarchicus (CF; Q3: n = 3, Q4: n = 3), and the amphipods Themisto libellula (TL; Q3: n = 4, Q4: n = 3) and T. abyssorum (TA; Q3: n = 3, Q4: n = 3). Horizontal bars in the box plots indicate median proportional values. Upper and lower edges of the boxes represent the approximate 1st and 3rd quartiles, respectively. Vertical error bars extend to the lowest and highest data value inside a range of 1.5 times the inter-quartile range, respectively (R Core Team, 2017). Individual datapoints are represented by the dots. Statistical differences between seasons are marked with an asterisk: *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

Variability in FA Composition

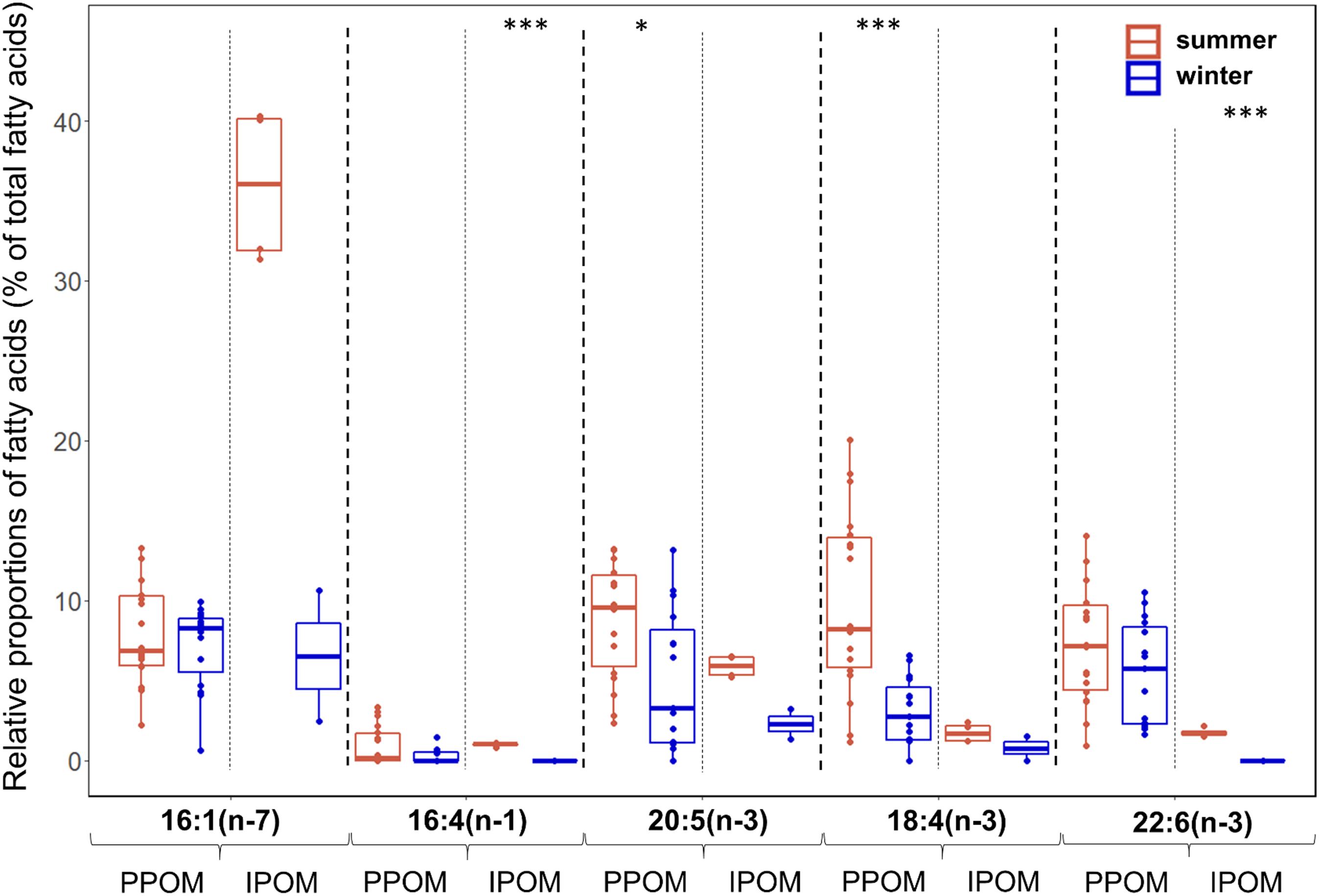

Pelagic and Ice-Associated Particulate Organic Matter (PPOM and IPOM)

During summer, the sum of diatom-associated FAs 16:1(n-7), 16:4(n-1), and 20:5(n-3) was on average more than twice as high in IPOM (mean 43%) compared to PPOM (mean 18%), whereas the sum of dinoflagellate-associated FAs 18:4(n-3) and 22:6(n-3) was on average more than four times higher in PPOM (mean 17%) than in IPOM (mean 4%; Figure 3). During winter, the sum of diatom-associated FAs was slightly higher in PPOM (mean 12%) than in IPOM (mean 9%), and the sum of dinoflagellate-associated FAs was on average nine times higher in PPOM (mean 9%) compared to IPOM (mean 1%).

Figure 3. Relative proportions (as % of total fatty acids-FAs) of diatom- [16:1(n-7), 16:4(n-1), 20:5(n-3)] and dinoflagellate-associated marker FAs [18:4(n-3), 22:6(n-3)] during summer (Q3) and winter (Q4) in pelagic particulate organic matter (PPOM) (Q3: n = 15, Q4: n = 18) and ice-associated particulate organic matter (IPOM) (Q3: n = 4, Q4: n = 2). Box plot design is described in Figure 2.

In both PPOM and IPOM, seasonal variability in FA profiles was mainly driven by differences in trophic marker FAs. In PPOM, all marker FAs, except for 16:1(n-7), had higher relative proportions during summer compared to winter, with significant differences in the diatom-associated FA 20:5(n-3) and the dinoflagellate-associated FA 18:4(n-3) (Figure 3). The averaged sum of dinoflagellate-associated FAs in PPOM was about twice as high during summer compared to winter. In IPOM, the same pattern was observed, with significantly higher proportions of the diatom-associated FA 16:4(n-1) and the dinoflagellate-associated FA 22:6(n-3) in summer compared to winter. Moreover, the diatom-associated FA 16:1n-7 dominated the IPOM FA profile during summer (mean 36%), whereas during winter, the relative proportions of the marker FAs were more evenly distributed (Figure 3). In summer, the averaged sum of diatom-associated FAs in IPOM was about five times higher than in winter, and the sum of dinoflagellate-associated FAs was four times higher. Relative proportions of individual FAs can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

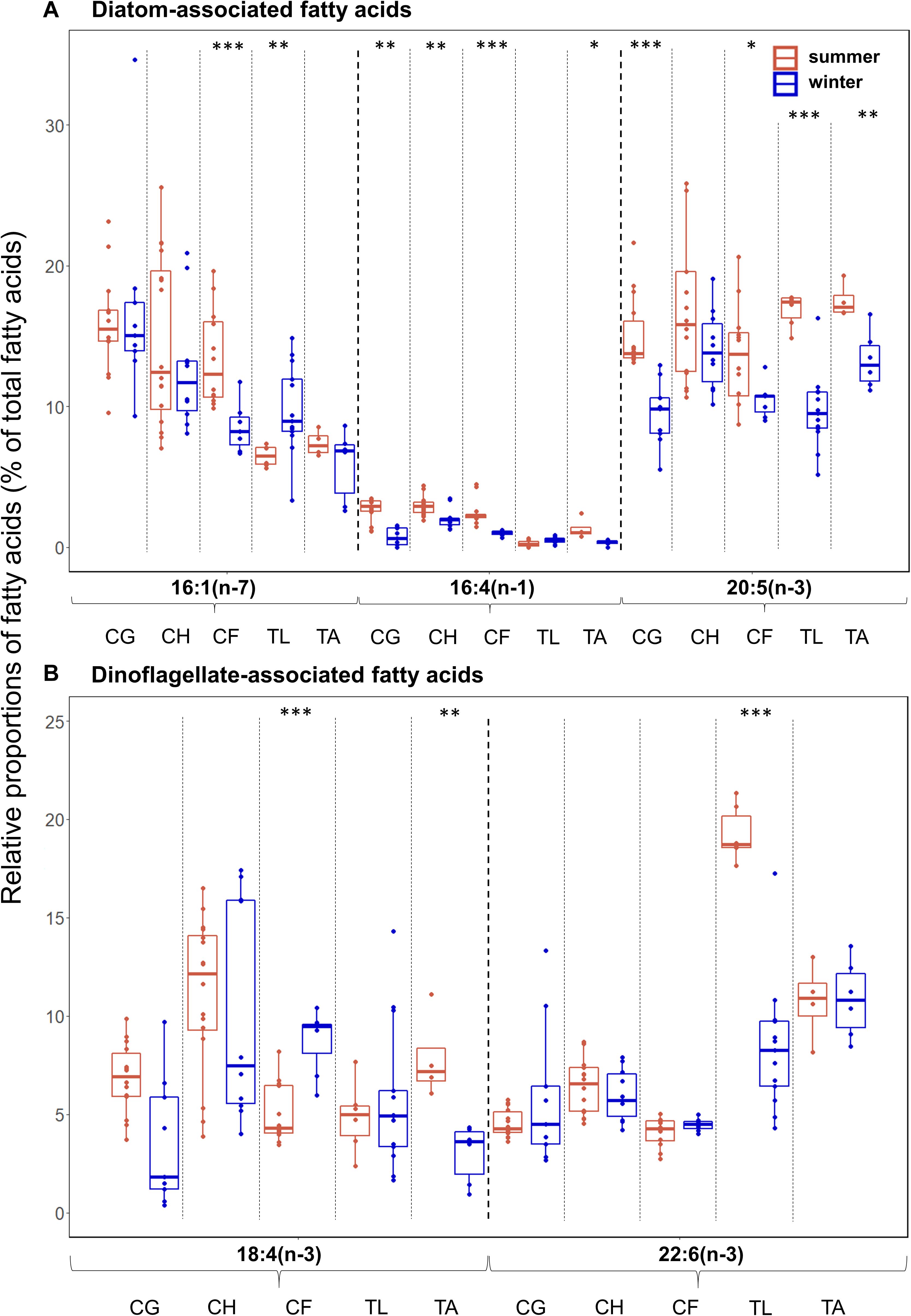

Zooplankton

Overall, differences in diatom-associated FAs were more pronounced than differences in dinoflagellate-associated FAs among the zooplankton (Figures 4A,B). Among all species, C. hyperboreus had the most stable fatty acid composition when transitioning from summer to winter conditions (Figure 4), and variability in FAs was not as pronounced as in the other species. In most species, the relative proportions of the diatom-associated FAs 16:4(n-1) (except for T. libellula) and 20:5(n-3) (except for C. hyperboreus) were significantly higher in summer than in winter (Figure 4A). There was no clear seasonal pattern apparent for the relative proportions of the two dinoflagellate-associated FAs. For example, in C. glacialis (Figure 4B; summer: mean 7%, winter: mean 4%) and T. abyssorum (summer: mean 8%, winter: mean 3%), the dinoflagellate-associated FA 18:4(n-3) had higher levels during summer, while in C. finmarchicus, this FA had higher levels during winter (summer: mean 5%, winter: mean 9%). The dinoflagellate-associated FA 22:6(n-3) had significantly higher levels in T. libellula collected during summer (mean 19%) compared to winter (mean 8%; Figure 4B), while in all other species seasonal differences in this FA were insignificant. Mean relative proportions of calanoid copepod-associated FAs were higher in winter (26.5 ± 8.4%) compared to summer (10.7 ± 2.2%) in T. libellula, but remained seasonally unchanged in T. abyssorum (19.9 ± 3.8 and 21.0 ± 4.8%, respectively). Relative proportions of individual FAs can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Figure 4. Relative proportions (as % of total fatty acids-FAs) of (A) diatom- [16:1(n-7), 16:4(n-1), 20:5(n-3)] and (B) dinoflagellate-associated marker FAs [18:4(n-3), 22:6(n-3)] during summer (Q3) and winter (Q4) in the copepods Calanus glacialis (CG; Q3: n = 14, Q4: n = 9), C. hyperboreus (CH; Q3: n = 16, Q4: n = 10) and C. finmarchicus (CF; Q3: n = 12, Q4: n = 7) and the amphipods Themisto libellula (TL; Q3: n = 6, Q4: n = 13) and T. abyssorum (TA; Q3: n = 4, Q4: n = 6). Box plot design is described in Figure 2.

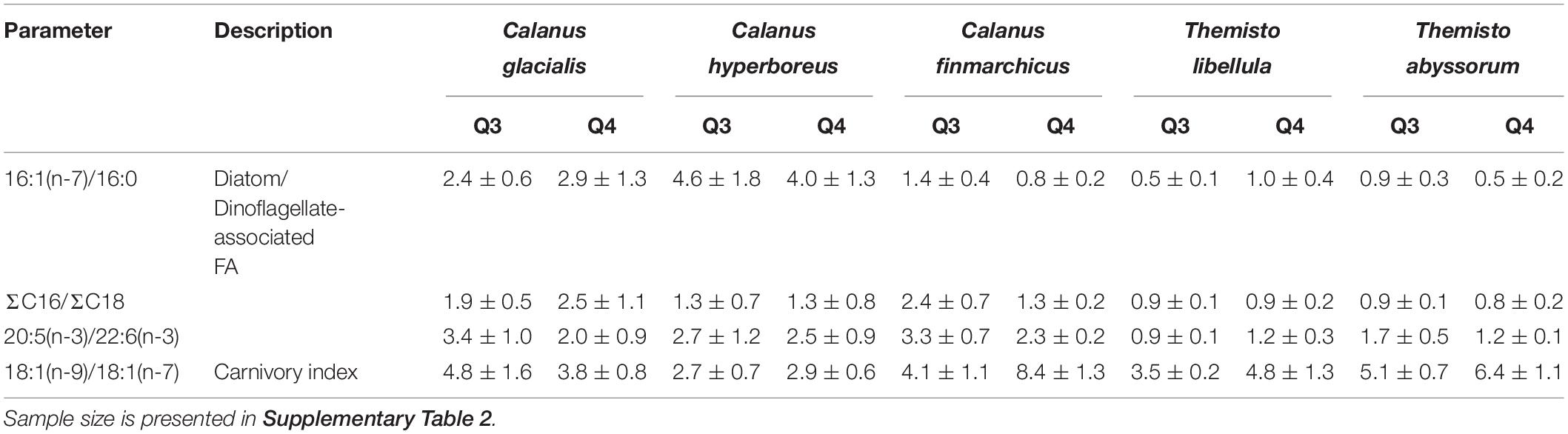

Based on the diatom/dinoflagellate marker FA ratios, Calanus spp. had a stronger diatom signal than amphipods during both seasons (Table 3). Based on the ratio 18:1(n-9)/18:1(n-7), the degree of carnivory increased from summer to winter in C. finmarchicus and both Themisto species, while the ratio 16:1(n-7)/16:0 simultaneously decreased in C. finmarchicus and T. abyssorum. The ratio 20:5(n-3)/22:6(n-3) decreased in C. glacialis, C. finmarchicus and T. abyssorum from summer to winter (Table 3).

Table 3. Trophic marker fatty acid ratios (mean ± SD) in copepods and amphipods during summer (Q3) and winter (Q4).

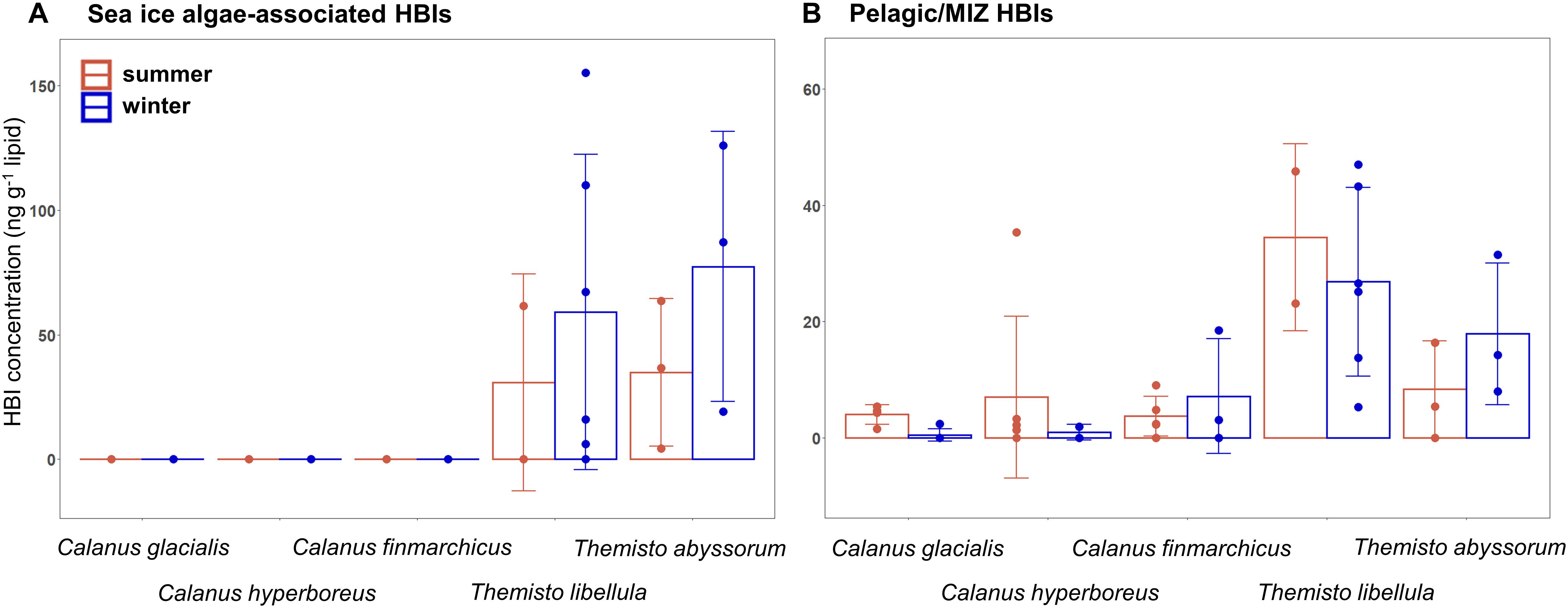

Variability in HBI and Sterol Composition

In both seasons, PPOM and all three Calanus species did not contain detectable quantities of the sea ice algae-associated HBIs IP25 and IPSO25 (Figure 5A). In both amphipod species, mean sea ice algae-associated HBI concentrations were slightly higher in winter compared to summer. Mean concentrations of the pelagic/MIZ HBIs III and IV were slightly lower in winter than in summer in C. glacialis, C. hyperboreus, and T. libellula, but lower in summer than in winter in C. finmarchicus and T. abyssorum (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Concentrations of (A) sea ice algae-associated and (B) pelagic/MIZ highly branched isoprenoids (HBIs; mean ± SD ng g− 1 lipid) in copepods and amphipods during summer (Q3) and winter (Q4). Individual datapoints are represented by the dots. Sample size is presented in Table 4.

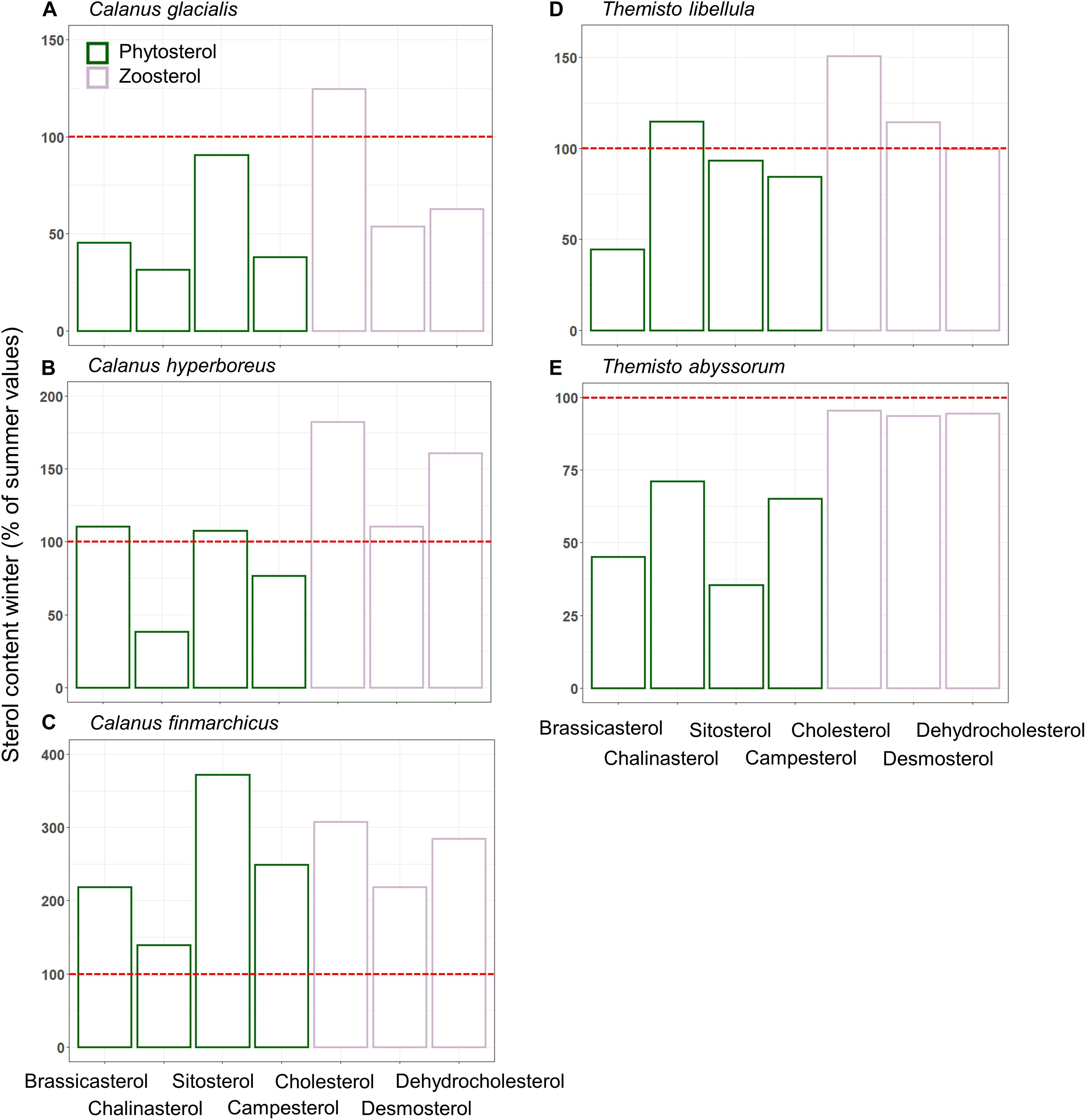

The mean ratio of zoosterols/phytosterols increased in all zooplankton species from summer to winter (Table 4), but there was large variability in individual sterols among the zooplankton between the seasons. In C. glacialis, all phyto- and zoosterols, except for cholesterol, had higher averaged values in summer compared to winter (Figure 6A). In C. hyperboreus, chalinasterol content in winter was about 30% of that in summer, while averaged levels of the other phytosterols were more similar between the seasons, and all zoosterols were higher during winter (Figure 6B). In C. finmarchicus, all phytosterols and zoosterols had higher averaged levels in winter than in summer (Figure 6C). All phytosterols, except for brassicasterol, were similar in summer and winter in T. libellula (Figure 6D), while in T. abyssorum, all phytosterols were less abundant in winter than in summer (Figure 6E). In both amphipods, the zoosterol content was relatively stable between the seasons.

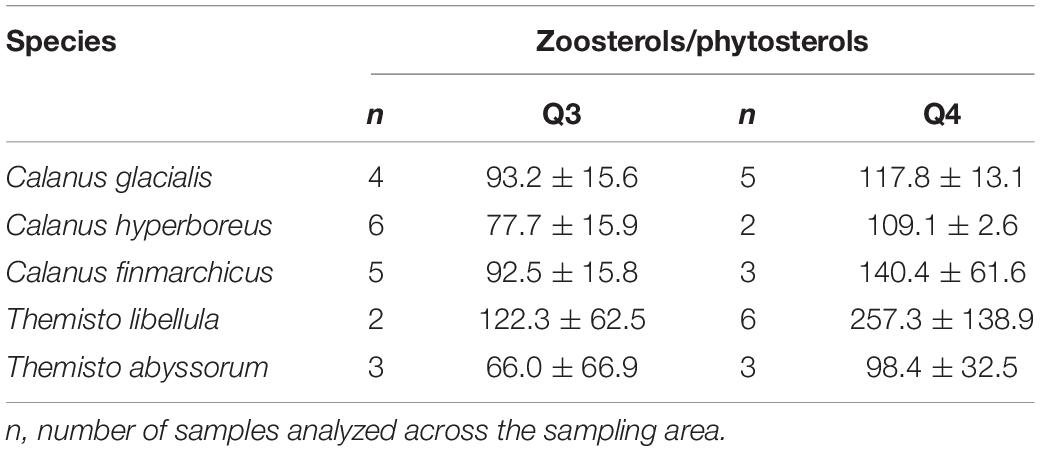

Table 4. Ratios of the relative values of zoosterols/phytosterols (mean ± SD) in copepods and amphipods during summer (Q3) and winter (Q4).

Figure 6. Relative proportions of phyto-and zoosterols (mean ± SD%) represented by green and purple bars, respectively, during winter (Q4) related to summer (Q3) in Calanus spp. (A–C) and Themisto spp. (D,E). Percentages are based on average sterol-content values from both sampling campaigns. The red line highlights 100%, i.e., same proportions of sterols during summer and winter. Sample size is presented in Table 4.

Discussion

All five species showed, to a varying degree, seasonal changes in their composition of lipid classes and lipid-based trophic markers, reflecting differences in life history and food composition between the more productive summer and low-level food availability during winter. Species that are utilizing their lipid storage during winter, such as Calanus spp., are typically rich in WEs. These constitute often more than 70% of their lipid mass (Figure 2A), providing a store of long-chained FAs and alcohols with a high density of energy (Graeve and Kattner, 1992; Falk-Petersen et al., 2009). By contrast, TAGs are metabolized faster, and often dominate the lipid reservoir of non-dormant species, such as Themisto spp. (Figure 2A; Albers et al., 1996; Lee et al., 2006).

Calanus Copepods

Congruent with other studies (Kattner et al., 1989; Scott et al., 2000; Falk-Petersen et al., 2009), C. hyperboreus had the highest WE levels (mean 97% in summer and 90% in winter related to total lipids) among the copepods during both seasons, which can be attributed to their superior ability to synthesize and store high-energy long-chained FAs and alcohols (20:1 and 22:1 isomers) (Ackman et al., 1974; Sargent and Falk-Petersen, 1988). In comparison with the other two Calanus species, C. hyperboreus showed similar FA composition and FA marker ratios during the polar day and night (Table 3 and Figure 4). Moreover, the total lipid content per dry weight was similar between summer and winter in C. hyperboreus (Table 2), indicating that this species was in similar body condition between the seasons and well adapted to the food-poor winter conditions.

In C. glacialis and C. hyperboreus, WE levels were higher in winter than in summer (Figure 2A), reflecting the significance of long-term storage lipids for successful overwintering in species that are directly dependent on the highly seasonal algal production (Albers et al., 1996; Lee et al., 2006; Falk-Petersen et al., 2009). Concomitantly, relative proportions of the faster metabolized TAGs decreased in these species in December, likely already utilized in the days and weeks prior to the winter sampling. In C. finmarchicus by contrast, the relative proportions of individual neutral and polar lipids varied little from summer to winter, indicating species-specific differences in seasonal lipid dynamics among the copepods (Figures 2A,B and Supplementary Table 1).

As found before (Søreide et al., 2008; Cleary et al., 2017), the marker FA ratios suggested the importance of diatom- over dinoflagellate-associated carbon in the diets of all three Calanus species during both seasons (Table 3). In C. glacialis and C. hyperboreus, the overall phytosterol content declined from late summer to early winter (Figures 6A,B), most noticeably in chalinasterol, however, variability across the sampling area was large. The decrease in phytosterols in C. glacialis and C. hyperboreus was not evident in C. finmarchicus, further pointing to differences in overwintering activity and strategies between the Calanus species. However, phyto- and zoosterol contents varied largely between the sampling stations within one species so that differences between the species might not only be species-specific but also driven by spatial variability. Pelagic HBIs were also slightly lower in C. glacialis and C. hyperboreus during winter (Figure 5B). Given that diatoms are the major producers of marine sterols (Stonik and Stonik, 2015; Jaramillo-Madrid et al., 2019), these changes likely reflected a shift away from intake of fresh phytoplankton during summer, as the primary production declined. The lower proportions of the diatom-associated FAs 16:4(n-1) and 20:5(n-3) in winter compared to summer in all three copepods (Figure 4A) further reflected the seasonal decrease in diatom contribution to their diet (lower Chl a concentrations in water column and sea ice, lower proportions of diatom-associated FAs in PPOM and IPOM; Figure 3).

In C. finmarchicus, the carnivory index 18:1(n-9)/18:1(n-7) and the averaged ratio of zoosterols to phytosterols were higher in winter than in summer (Tables 3, 4). The other two Calanus species also showed higher ratios of zoosterols/phytosterols during winter, but ratios of 18:1(n-9)/18:1(n-7) varied little between the seasons in C. hyperboreus and were even lower in winter compared to summer in C. glacialis (Tables 3, 4). While proportions of 18:1(n-9) can potentially increase during starvation (Graeve et al., 1997), these species-specific differences could also indicate that the C. finmarchicus investigated in our study were actually active during the winter sampling, which was also reported for Calanus spp. in Svalbard fjords (Daase et al., 2018), and relied more on degraded heterotrophic material or heterotrophic prey due to the low quantity and quality of POM during winter (Søreide et al., 2008; Hobbs et al., 2020). For example, winter-active C. glacialis may be able to prey on small copepods, and their eggs and nauplii that are available during winter (Hobbs et al., 2020), as well as early life stages of chaetognaths or ctenophores (Cleary et al., 2017). Calanus individuals that were not able to accumulate enough lipids during the productive season might be required to stay active during winter (Hobbs et al., 2020), and search for food near the surface or ice-water interface (Pedersen et al., 1995), while individuals with large lipid stores can descend into deeper water layers where food but also predators are scarce (Wold et al., 2011; Freese et al., 2017; Schmid et al., 2018; Kvile et al., 2019). Seasonal changes in the trophic markers can, to some degree also reflect ontogenetic differences in the copepods, and consequently feeding behavior and food composition driven by size or possibly sex. The samples collected during summer contained individuals of the copepodid stages CIV and CV as well as female adults, and the samples collected during winter contained stages CIV, CV, female, and male individuals (Table 2), however, due to the low sample size of each life stage it is not possible to reveal the influence of ontogenetic variability in this study.

Failure to detect the sea ice algae-associated HBIs in all three Calanus species during both seasons (Figure 5A) suggests that their carbon sources were likely predominantly of pelagic origin. Ice algae can be essential for reproduction and development of early Calanus life stages in spring (Niehoff et al., 2002; Søreide et al., 2010; Daase et al., 2013), but abundant pelagic food during spring and summer, large lipid reservoirs and dormancy during winter possibly render alternative or additional ice-associated carbon sources unnecessary. However, the known HBI-producing ice algal taxa Haslea and Pleurosigma (Brown et al., 2014a,b; Limoges et al., 2018) are not usually amongst the major ice algal species, and indeed were not detected in the sea-ice communities during both seasons (or their abundances were below the detection limit of the Utermöhl settling method). This is in agreement with previous taxonomic studies showing that the known IP25-producing species (Haslea crucigeroides, H. spicula, H. kjellmanii, and Pleurosigma stuxbergii var rhomboides) typically represent <1% of the sea ice diatom assemblages in Svalbard waters (von Quillfeldt, 2000). Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that the copepods were grazing on sea-ice algae containing HBI producers, but which were below the detection limit or were grazing on non-HBI-producing ice algal taxa. We should emphasize, however, that both amphipods and other pelagic zooplankton such as the filter-feeding pteropods Clione limacina and Limacina helicina contained sympagic HBIs during summer (Kohlbach et al., 2021), pointing to differences in feeding depth layers and/or feeding mechanisms between the taxa, and showing that HBI-producing diatoms were present at some point in the sampling area.

Themisto Amphipods

The two pelagic amphipods varied in their lipid class (Figures 2A,B) and FA compositions (Figures 4A,B) as well as seasonal variability of these parameters, which supports the notion that the two species differ in their lipid storage modes, carbon source composition and consequently their trophic interactions within the Arctic food web (Auel et al., 2002).

During both seasons, concentrations of pelagic HBIs were higher(Figure 5B), whereas 18:1(n-9)/18:1(n-7) carnivory ratios were lower in T. libellula compared toT. abyssorum (Table 3), suggestingthat T. abyssorum occupied a higher trophic level than T. libellula, in agreement with the literature (Auel et al., 2002). In both amphipod species, heterotrophic prey had a greater contribution to their food composition in winter versus summer based on the higher carnivory ratios of 18:1(n-9)/18:1(n-7) and zoosterols to phytosterol ratios (Tables 3, 4). To some extent, the observed seasonal differences likely reflect ontogenetic changes in carbon and prey composition (Noyon et al., 2012), e.g., in T. libellula from early life stages during summer (average dry weight 3.5 mg ind.–1) to larger predatory T. libellula individuals during winter (average dry weight 43.4 mg/ind–1).

The significantly higher relative proportions of the marker FA 18:4(n-3) in T. abyssorum during summer (Figure 4B) reflected the higher concentrations and availability of dinoflagellates and/or Phaeocystis, in agreement with higher relative proportions of 18:4(n-3) in summer PPOM compared to winter PPOM (Figure 3), and further suggests the greater importance of phytoplankton and flagellate-based prey in their diet during the polar day. Our results correspond to previous studies (Mayzaud and Boutoute, 2015), suggesting continuous, more carnivorous, feeding during winter for both species (Dale et al., 2006; Kraft et al., 2013).

In both amphipods, WE levels were higher during winter (Figure 2A), pointing to an increased predation on wax ester-rich species during the polar night. In the case of T. libellula, these seasonal differences in WEs as well as calanoid copepod-associated FAs reflected the greater importance of Calanus copepods in their winter diet (Supplementary Table 2). Significantly higher levels of the diatom-associated FA 16:1(n-7), an important contributor to the FA pool of Calanus spp., in T. libellula during winter further highlights the significance of these copepods for the successful overwintering of T. libellula. The significantly higher relative proportions of the polyunsaturated FAs (PUFAs) 20:5(n-3) and 22:6(n-3) in T. libellula in summer compared to winter (Figures 4A,B) could again point to ontogenetic differences in feeding habits, as the rather omnivorous younger stages (length group 5–20 mm) collected during summer probably fed more intensely on PUFA-rich phytoplankton/ice algae than the mostly carnivorous adult stages of T. libellula (length group 10–40 mm) (Noyon et al., 2009, 2012). However, these PUFAs are mainly incorporated into polar lipids (Stübing et al., 2003), and lower PUFA concentrations in T. libellula in winter might be explained by the larger proportion of storage lipids during the polar night (Supplementary Table 1).

In T. abyssorum, zooplankton other than Calanus spp. might have been equally important prey items due to similar relative proportions of calanoid copepod-associated FAs in both seasons. Calanus copepods are generally an important food item for both amphipods (Auel et al., 2002; Dalsgaard et al., 2003; Marion et al., 2008; Noyon et al., 2009), but T. abyssorum has been reported to also prey on other copepods such as Metridia and appendicularians (Dalpadado et al., 2008). Information on feeding modes and diet composition during the polar night is generally scarce, but during summer and autumn, T. abyssorum has been found to have a greater diversity of food items in comparison to T. libellula which fed mostly on copepods (Auel et al., 2002; Dalpadado et al., 2008). For carnivorous species, such as the two hyperiid amphipods, seasonality in primary production has a less severe impact on their feeding behavior in comparison to herbivorous copepods since their preferred prey is basically available throughout the year (Hagen and Auel, 2001; Hirche and Kosobokova, 2011).

Themisto libellula is associated with Arctic waters, while T. abyssorum is more abundant in subarctic (Atlantic) waters. Moreover, T. libellula has been observed to be distributed closer to the surface (<50 m) which could give them easier access to sea ice-associated prey than T. abyssorum that has a more mesopelagic lifestyle (>200 m) (Dalpadado et al., 2001; Auel et al., 2002; Dalpadado, 2002). However, concentrations of sea ice algae-associated HBIs were similar between the two species (Figure 5A), only slightly higher in T. abyssorum, indicating an at least comparable trophic relationship to the ice-associated ecosystem for both species. The lack of sea ice algae-associated HBIs in the copepods further reveals that both amphipod species obtained sympagic metabolites by feeding on other sympagic prey. The presence versus absence of sea ice-derived HBIs in amphipods and copepods, respectively, likely reflects differences in their feeding location (under ice versus water column) and/or feeding behavior. Furthermore, it is possible that the juvenile amphipods during summer were feeding on sinking ice algal aggregates in the mid-water column (marine snow), as suggested for pteropods and appendicularians (Kohlbach et al., 2021), as young Arctic and Antarctic Themisto have been observed to feed partly on phytoplankton (Noyon et al., 2012; Watts and Tarling, 2012). Sea ice algae-associated HBIs were somewhat more concentrated in the winter compared to the summer Themisto spp., but concentrations varied strongly among the individuals (Figure 5A). On one hand, this could again reflect ontogenetic differences in food composition, but could on the other hand, be the result of the very opportunistic feeding style of these amphipods (Havermans et al., 2019).

Highly branched isoprenoids concentrations in Barents Sea fauna during winter, spanning pelagic and benthic invertebrates and fish, were in a similar order of magnitude as in our study (Figures 5A,B; Brown et al., 2015). Compared to HBI concentrations in Antarctic krill Euphausia superba, however, the levels of both sea ice algae-associated and pelagic HBIs in the amphipods were distinctly lower in our study. This could reflect hemispheric differences in the abundance of HBI-producing algae as for example Arctic diatoms producing IP25 have, despite their ubiquitous distribution throughout the Arctic, a relatively low contribution (< 5%) to the overall sympagic diatom community (Brown et al., 2014b). Given the low level of sea ice-associated primary production and that the available ice algae are not accessible for grazers during winter, HBIs detected in the winter samples could also, to some degree, reflect the importance of benthic food sources for the amphipods as HBI-producing diatoms have been found to be present in benthic sediments and bottom waters rather than sea ice and upper water layers during winter (Brown et al., 2015). Both amphipod species have been observed close to the seafloor (Vinogradov, 1999), however, the extent that they rely on benthic food sources remains unclear.

Conclusion

During some periods of the year, sea ice algae can serve as a valuable carbon source for ice-associated grazers and subsequently their predators, both in the Arctic (Wang et al., 2015, 2016; Kohlbach et al., 2016, 2019) and the Antarctic marine environment (Kohlbach et al., 2017, 2018; Bernard et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2018). Yet, in both late summer and early winter, the trophic link between Calanus copepods and the ice-associated ecosystem was weak in our study area. This suggests that (a) during summer, phytoplankton and pelagic prey are sufficient to meet the energetic requirements of the copepods and (b) diapause or the decrease in metabolic activity as well as the presence of accumulated lipids during winter counteract the reliance on ice algae. Furthermore, in the case of the (likely) winter-active C. finmarchicus, plasticity in feeding behavior and carbon source composition enables successful survival, seemingly without the utilization of sympagic carbon. In the Themisto amphipods, relatively similar concentrations of sea ice-associated metabolites in their lipid pool between the seasons and ontogenetic life stages suggest that sympagic carbon was more important, possibly obtained from benthic food sources, but still likely not critical for their overwintering in the Barents Sea. Rather than diapause, carnivory helped sustain these amphipods during the polar night.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

AW and AKA-H conducted the sampling. HH and PA provided sampling logistics. PA, HH, and DK developed the study design. DK was the main author of this manuscript and accomplished the fatty acid laboratory analyses and data evaluation. MW carried out lipid class analysis with support of MG. KS accomplished the HBI and sterol analysis and data evaluation with the help of LS, SB, and AA. MG and SB provided laboratory materials, methodological expertise, and laboratory space. Data analyses and figure assemblage was done by DK with the help of the other authors. All authors contributed significantly to data interpretation and to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Research Council of Norway through the project The Nansen Legacy (RCN #276730). Contributions by KS, SB, and AA were funded by the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council MOSAiC-Thematic project SYM-PEL: “Quantifying the contribution of sympagic versus pelagic diatoms to Arctic food webs and biogeochemical fluxes: application of source-specific highly branched isoprenoid biomarkers” (NE/S002502/1).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the captain and the crew of RV Kronprins Haakon for their excellent support at sea during the Nansen Legacy seasonal cruises Q3 and Q4. We would like to thank Kasia Dmoch (IOPAN) for her help with zooplankton sorting during Q3, and Sinah Müller and Valeria Adrian (AWI) with their help with the fatty acid laboratory analyses. We thank Øyvind Lundesgaard (NPI) for his help creating the sea-ice map. We thank the editor Anne Helene Tandberg and the two reviewers for providing helpful comments and suggestions during the review process.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.640050/full#supplementary-material

References

Aarflot, J. M., Skjoldal, H. R., Dalpadado, P., and Skern-Mauritzen, M. (2018). Contribution of Calanus species to the mesozooplankton biomass in the Barents Sea. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 75, 2342–2354. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsx221

Ackman, R. G., Linke, B. A., and Hingley, J. (1974). Some details of fatty acids and alcohols in the lipids of North Atlantic copepods. J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 31, 1812–1818. doi: 10.1139/f74-233

Albers, C. S., Kattner, G., and Hagen, W. (1996). The compositions of wax esters, triacylglycerols and phospholipids in Arctic and Antarctic copepods: evidence of energetic adaptations. J. Mar. Chem. 55, 347–358. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4203(96)00059-X

Årthun, M., Eldevik, T., and Smedsrud, L. H. (2019). The role of Atlantic heat transport in future Arctic winter sea ice loss. J. Clim. 32, 3327–3341. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-18-0750.1

Årthun, M., Eldevik, T., Smedsrud, L. H., and Skagseth, Ø, and Ingvaldsen, R. B. (2012). Quantifying the influence of Atlantic heat on Barents Sea ice variability and retreat. J. Clim. 25, 4736–4743. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00466.1

Assmy, P., Ehn, J. K., Fernández-Méndez, M., Hop, H., Katlein, C., Sundfjord, A., et al. (2013). Floating ice-algal aggregates below melting Arctic sea ice. PLoS One 8:e76599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076599

Atkinson, A. (1998). Life cycle strategies of epipelagic copepods in the Southern Ocean. J. Mar. Syst. 15, 289–311. doi: 10.1016/S0924-7963(97)00081-X

Atkinson, A., Ward, P., Hunt, B. P. V., Pakhomov, E. A., and Hosie, G. W. (2012). An overview of Southern Ocean zooplankton data: abundance, biomass, feeding and functional relationships. CCAMLR Sci. 19, 171–218.

Auel, H., Harjes, M., Da Rocha, R., Stübing, D., and Hagen, W. (2002). Lipid biomarkers indicate different ecological niches and trophic relationships of the Arctic hyperiid amphipods Themisto abyssorum and T. libellula. Polar Biol. 25, 374–383. doi: 10.1007/s00300-001-0354-7

Bandara, K., Varpe, Ø, Søreide, J. E., Wallenschus, J., Berge, J., and Eiane, K. (2016). Seasonal vertical strategies in a high-Arctic coastal zooplankton community. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 555, 49–64. doi: 10.3354/meps11831

Barton, B. I., Lenn, Y.-D., and Lique, C. (2018). Observed Atlantification of the Barents Sea causes the polar front to limit the expansion of winter sea ice. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 48, 1849–1866. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-18-0003.1

Belt, S. T. (2018). Source-specific biomarkers as proxies for Arctic and Antarctic sea ice. Org. Geochem. 125, 277–298. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2018.10.002

Belt, S. T., Brown, T. A., Sanz, P. C., and Rodriguez, A. N. (2012). Structural confirmation of the sea ice biomarker IP25 found in Arctic marine sediments. Environ. Chem. Lett. 10, 189–192. doi: 10.1007/s10311-011-0344-0

Belt, S. T., Brown, T. A., Smik, L., Assmy, P., and Mundy, C. J. (2018). Sterol identification in floating Arctic sea ice algal aggregates and the Antarctic sea ice diatom Berkeleya adeliensis. Org. Geochem. 118, 1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2018.01.008

Berge, J., Daase, M., Hobbs, L., Falk-Petersen, S., Darnis, G., and Søreide, J. E. (2020). “Zooplankton in the polar night,” in Polar Night Marine Ecology, eds J. Berge, G. Johnsen, and J. H. Cohen (Cham: Springer), 113–159.

Berge, J., Daase, M., Renaud, P. E., Ambrose, W. G. Jr., Darnis, G., Last, K. S., et al. (2015). Unexpected levels of biological activity during the polar night offer new perspectives on a warming Arctic. J. Curr. Biol. 25, 2555–2561. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.024

Bernard, K. S., Gunther, L. A., Mahaffey, S. H., Qualls, K. M., Sugla, M., Saenz, B. T., et al. (2018). The contribution of ice algae to the winter energy budget of juvenile Antarctic krill in years with contrasting sea ice conditions. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 76, 206–216. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsy145

Brown, T. A., Assmy, P., Hop, H., Wold, A., and Belt, S. T. (2017). Transfer of ice algae carbon to ice-associated amphipods in the high-Arctic pack ice environment. J. Plankton Res. 39, 664–674. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbx030

Brown, T. A., and Belt, S. T. (2012). Identification of the sea ice diatom biomarker IP25 in Arctic benthic macrofauna: direct evidence for a sea ice diatom diet in Arctic heterotrophs. Polar Biol. 35, 131–137. doi: 10.1007/s00300-011-1045-7

Brown, T. A., Belt, S. T., and Cabedo-Sanz, P. (2014a). Identification of a novel di-unsaturated C25 highly branched isoprenoid in the marine tube-dwelling diatom Berkeleya rutilans. Environ. Chem. Lett. 12, 455–460. doi: 10.1007/s10311-014-0472-4

Brown, T. A., Belt, S. T., Tatarek, A., and Mundy, C. J. (2014b). Source identification of the Arctic sea ice proxy IP25. Nat. Commun. 5:4197. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5197

Brown, T. A., Hegseth, E. N., and Belt, S. T. (2015). A biomarker-based investigation of the mid-winter ecosystem in Rijpfjorden, Svalbard. Polar Biol. 38, 37–50. doi: 10.1007/s00300-013-1352-2

Campbell, R. G., Sherr, E. B., Ashjian, C. J., Plourde, S., Sherr, B. F., Hill, V., et al. (2009). Mesozooplankton prey preference and grazing impact in the western Arctic Ocean. Deep Sea Res. II 56, 1274–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.10.027

Choi, H., Ha, S.-Y., Lee, S., Kim, J.-H., and Shin, K.-H. (2020). Trophic dynamics of zooplankton before and after Polar Night in the Kongsfjorden (Svalbard): evidence of trophic position estimated by δ15N analysis of amino acids. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:489. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00489

Choquet, M., Kosobokova, K., Kwaśniewski, S., Hatlebakk, M., Dhanasiri, A. K., Melle, W., et al. (2018). Can morphology reliably distinguish between the copepods Calanus finmarchicus and C. glacialis, or is DNA the only way? Limnol. Oceanogr. (Methods) 16, 237–252. doi: 10.1002/lom3.10240

Cleary, A. C., Søreide, J. E., Freese, D., Niehoff, B., and Gabrielsen, T. M. (2017). Feeding by Calanus glacialis in a high arctic fjord: potential seasonal importance of alternative prey. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 74, 1937–1946. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsx106

Conover, R. J., and Huntley, M. (1991). Copepods in ice-covered seas—distribution, adaptations to seasonally limited food, metabolism, growth patterns and life cycle strategies in polar seas. J. Mar. Syst. 2, 1–41. doi: 10.1016/0924-7963(91)90011-I

Daase, M., Falk-Petersen, S., Varpe, Ø, Darnis, G., Søreide, J. E., Wold, A., et al. (2013). Timing of reproductive events in the marine copepod Calanus glacialis: a pan-Arctic perspective. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 70, 871–884. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2015-0333

Daase, M., Kosobokova, K., Last, K. S., Cohen, J. H., Choquet, M., Hatlebakk, M., et al. (2018). New insights into the biology of Calanus spp. (Copepoda) males in the Arctic. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 607, 53–69. doi: 10.3354/meps12788

Dale, K., Falk-Petersen, S., Hop, H., and Fevolden, S.-E. (2006). Population dynamics and body composition of the Arctic hyperiid amphipod Themisto libellula in Svalbard fjords. Polar Biol. 29, 1063–1070. doi: 10.1007/s00300-006-0150-5

Dalpadado, P. (2002). Inter-specific variations in distribution, abundance and possible life-cycle patterns of Themisto spp. (Amphipoda) in the Barents Sea. Polar Biol. 25, 656–666. doi: 10.1007/s00300-002-0390-y

Dalpadado, P., Borkner, N., Bogstad, B., and Mehl, S. (2001). Distribution of Themisto (Amphipoda) spp. in the Barents Sea and predator-prey interactions. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 58, 876–895. doi: 10.1006/jmsc.2001.1078

Dalpadado, P., Yamaguchi, A., Ellertsen, B., and Johannessen, S. (2008). Trophic interactions of macro-zooplankton (krill and amphipods) in the Marginal Ice Zone of the Barents Sea. Deep Sea Res. II 55, 2266–2274. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.05.016

Dalsgaard, J., St. John, M., Kattner, G., Müller-Navarra, D., and Hagen, W. (2003). Fatty acid trophic markers in the pelagic marine environment. Adv. Mar. Biol. 46, 227–237. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2881(03)46005-7

David, C., Lange, B., Rabe, B., and Flores, H. (2015). Community structure of under-ice fauna in the Eurasian central Arctic Ocean in relation to environmental properties of sea-ice habitats. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 522, 15–32. doi: 10.3354/meps11156

Drazen, J. C., Phleger, C. F., Guest, M. A., and Nichols, P. D. (2008). Lipid, sterols and fatty acid composition of abyssal holothurians and ophiuroids from the North-East Pacific Ocean: food web implications. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 151, 79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2008.05.013

Durbin, E. G., and Casas, M. C. (2014). Early reproduction by Calanus glacialis in the Northern Bering Sea: the role of ice algae as revealed by molecular analysis. J. Plankton Res. 36, 523–541. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbt121

Eriksen, E., Benzik, A. N., Dolgov, A. V., Skjoldal, H. R., Vihtakari, M., Johannesen, E., et al. (2020). Diet and trophic structure of fishes in the Barents Sea: the Norwegian-Russian program “Year of stomachs” 2015–establishing a baseline. Prog. Oceanogr. 183:102262. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2019.102262

Falk-Petersen, S., Hagen, W., Kattner, G., Clarke, A., and Sargent, J. (2000a). Lipids, trophic relationships, and biodiversity in Arctic and Antarctic krill. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 57, 178–191. doi: 10.1139/f00194

Falk-Petersen, S., Hop, H., Budgell, W. P., Hegseth, E. N., Korsnes, R., Løyning, T. B., et al. (2000b). Physical and ecological processes in the marginal ice zone of the northern Barents Sea during the summer melt period. J. Mar. Syst. 27, 131–159. doi: 10.1016/S0924-7963(00)00064-6

Falk-Petersen, S., Hopkins, C. C. E., and Sargent, J. R. (1990). “Trophic relationships in the pelagic, Arctic food web,” in Trophic Relationships in the Marine Environment, eds M. Barnes and R. N. Gibson (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press), 315–333.

Falk-Petersen, S., Mayzaud, P., Kattner, G., and Sargent, J. R. (2009). Lipids and life strategy of Arctic Calanus. Mar. Biol. Res. 5, 18–39. doi: 10.1080/17451000802512267

Falk-Petersen, S., Pavlov, V., Timofeev, S., and Sargent, J. R. (2007). “Climate variability and possible effects on arctic food chains: the role of Calanus,” in Arctic Alpine Ecosystems and People in a Changing Environment, eds J. B. Ørbæk, R. Kallenborn, I. Tombre, E. N. Hegseth, and S. Falk-Petersen (Berlin: Springer), 147–166.

Falk-Petersen, S., Sargent, J. R., Henderson, J., Hegseth, E. N., Hop, H., and Okolodkov, Y. B. (1998). Lipids and fatty acids in ice algae and phytoplankton from the Marginal Ice Zone in the Barents Sea. Polar Biol. 20, 41–47. doi: 10.1007/s003000050274

Folch, J., Lees, M., and Sloane Stanley, G. H. (1957). A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. (Baltim.) 226, 497–509.

Francis, J. A., and Hunter, E. (2007). Drivers of declining sea ice in the Arctic winter: a tale of two seas. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34:L17503. doi: 10.1029/2007GL030995

Freese, D., Søreide, J. E., Graeve, M., and Niehoff, B. (2017). A year-round study on metabolic enzymes and body composition of the Arctic copepod Calanus glacialis: implications for the timing and intensity of diapause. Mar. Biol. 164:3. doi: 10.1007/s00227-016-3036-2

Gradinger, R. R. (2009). Sea-ice algae: major contributors to primary production and algal biomass in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas during May/June 2002. Deep Sea Res. II 56, 1201–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.10.016

Graeve, M., Hagen, W., and Kattner, G. (1994). Herbivorous or omnivorous? On the significance of lipid compositions as trophic markers in Antarctic copepods. Deep Sea Res. I 41, 915–924. doi: 10.1016/0967-0637(94)90083-3

Graeve, M., and Janssen, D. (2009). Improved separation and quantification of neutral and polar lipid classes by HPLC–ELSD using a monolithic silica phase: application to exceptional marine lipids. J. Chromatogr. B 877, 1815–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.05.004

Graeve, M., and Kattner, G. (1992). Species-specific differences in intact wax esters of Calanus hyperboreus and C. finmarchicus from Fram Strait- Greenland Sea. Mar. Chem. 39, 269–281. doi: 10.1016/0304-4203(92)90013-Z

Graeve, M., Kattner, G., and Piepenburg, D. (1997). Lipids in Arctic benthos: does the fatty acid and alcohol composition reflect feeding and trophic interactions? Polar Biol. 18, 53–61. doi: 10.1007/s003000050158

Hagen, W. (1999). Reproductive strategies and energetic adaptations of polar zooplankton. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 36, 25–34. doi: 10.1080/07924259.1999.9652674

Hagen, W., and Auel, H. (2001). Seasonal adaptations and the role of lipids in oceanic zooplankton. Zoology 104, 313–326. doi: 10.1078/0944-2006-00037

Halvorsen, E. (2015). Significance of lipid storage levels for reproductive output in the Arctic copepod Calanus hyperboreus. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 540, 259–265. doi: 10.3354/meps11528

Haug, T., Falk-Petersen, S., Greenacre, M., Hop, H., Lindstrøm, U., and Meier, S. (2017). Trophic level and fatty acids in harp seals compared with common minke whales in the Barents Sea. Mar. Biol. Res. 13, 919–932. doi: 10.1080/17451000.2017.1313988

Havermans, C., Auel, H., Hagen, W., Held, C., Ensor, N. S., and Tarling, G. A. (2019). Predatory zooplankton on the move: Themisto amphipods in high-latitude marine pelagic food webs. Adv. Mar. Biol. 82, 51–92. doi: 10.1016/bs.amb.2019.02.002

Herbaut, C., Houssais, M.-N., Close, S., and Blaizot, A.-C. (2015). Two wind-driven modes of winter sea ice variability in the Barents Sea. Deep Sea Res. I 106, 97–115. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2015.10.005

Hirche, H.-J. (1997). Life cycle of the copepod Calanus hyperboreus in the Greenland Sea. Mar. Biol. 128, 607–618. doi: 10.1007/s002270050127

Hirche, H.-J. (2013). Long-term experiments on lifespan, reproductive activity and timing of reproduction in the Arctic copepod Calanus hyperboreus. Mar. Biol. 160, 2469–2481. doi: 10.1007/s00227-013-2242-4

Hirche, H.-J., and Kosobokova, K. N. (2007). Distribution of Calanus finmarchicus in the northern North Atlantic and Arctic Ocean—expatriation and potential colonization. Deep Sea Res. II 54, 2729–2747. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2007.08.006

Hirche, H.-J., and Kosobokova, K. N. (2011). Winter studies on zooplankton in Arctic seas: the Storfjord (Svalbard) and adjacent ice-covered Barents Sea. Mar. Biol. 158, 2359–2376. doi: 10.1007/s00227-011-1740-5

Hirche, H.-J., and Mumm, N. (1992). Distribution of dominant copepods in the Nansen Basin, Arctic Ocean, in summer. Deep Sea Res. A 39, S485–S505. doi: 10.1016/S0198-0149(06)80017-8

Hobbs, L., Banas, N. S., Cottier, F. R., Berge, J., and Daase, M. (2020). Eat or sleep: availability of winter prey explains mid-winter and spring activity in an Arctic Calanus population. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:744. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.541564

Hop, H., Assmy, P., Wold, A., Sundfjord, A., Daase, M., Duarte, P., et al. (2019). Pelagic ecosystem characteristics across the Atlantic water boundary current from Rijpfjorden, Svalbard, to the Arctic Ocean during summer (2010–2014). Front. Mar. Sci. 6:181. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00181

Hop, H., and Gjøsæter, H. (2013). Polar cod (Boreogadus saida) and capelin (Mallotus villosus) as key species in marine food webs of the Arctic and the Barents Sea. Mar. Biol. Res. 9, 878–894. doi: 10.1080/17451000.2013.775458

Hop, H., Poltermann, M., Lønne, O. J., Falk-Petersen, S., Korsnes, R., and Budgell, W. P. (2000). Ice amphipod distribution relative to ice density and under-ice topography in the northern Barents Sea. Polar Biol. 23, 357–367. doi: 10.1007/s003000050456

Iverson, S. J. (2009). “Tracing aquatic food webs using fatty acids: from qualitative indicators to quantitative determination,” in Lipids in Aquatic Ecosystems, eds M. Kainz, M. T. Brett, and M. T. Arts (New York, NY: Springer), 281–308.

Jakubas, D., Wojczulanis-Jakubas, K., Boehnke, R., Kidawa, D., Błachowiak-Samołyk, K., and Stempniewicz, L. (2016). Intra-seasonal variation in zooplankton availability, chick diet and breeding performance of a high Arctic planktivorous seabird. Polar Biol. 39, 1547–1561. doi: 10.1007/s00300-015-1880-z

Jaramillo-Madrid, A. C., Ashworth, J., Fabris, M., and Ralph, P. J. (2019). Phytosterol biosynthesis and production by diatoms (Bacillariophyceae). Phytochem 163, 46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.03.018

Kattner, G., and Fricke, H. S. G. (1986). Simple gas-liquid chromatographic method for the simultaneous determination of fatty acids and alcohols in wax esters of marine organisms. J. Chromatogr. A 361, 263–268. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)86914-4

Kattner, G., Graeve, M., and Hagen, W. (1994). Ontogenetic and seasonal changes in lipid and fatty acid/alcohol compositions of the dominant Antarctic copepods Calanus propinquus, Calanoides acutus and Rhincalanus gigas. Mar. Biol. 118, 637–644. doi: 10.1007/BF00347511

Kattner, G., Hirche, H. J., and Krause, M. (1989). Spatial variability in lipid composition of calanoid copepods from Fram Strait, the Arctic. Mar. Biol. 102, 473–480. doi: 10.1007/BF00438348

Kohlbach, D., Ferguson, S. H., Brown, T. A., and Michel, C. (2019). Landfast sea ice-benthic coupling during spring and potential impacts of system changes on food web dynamics in Eclipse Sound, Canadian Arctic. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 627, 33–48. doi: 10.3354/meps13071

Kohlbach, D., Graeve, M., Lange, B. A., David, C., Peeken, I., and Flores, H. (2016). The importance of ice algae−produced carbon in the central Arctic Ocean ecosystem: food web relationships revealed by lipid and stable isotope analyses. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, 2027–2044. doi: 10.1002/lno.10351

Kohlbach, D., Graeve, M., Lange, B. A., David, C., Schaafsma, F. L., van Franeker, J. A., et al. (2018). Dependency of Antarctic zooplankton species on ice algae−produced carbon suggests a sea ice−driven pelagic ecosystem during winter. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 4667–4681. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14392

Kohlbach, D., Hop, H., Wold, A., Schmidt, K., Smik, L., Belt, S. T., et al. (2021). Multiple trophic markers trace dietary carbon sources in Barents Sea zooplankton during late summer. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:610248. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.610248

Kohlbach, D., Lange, B. A., Schaafsma, F. L., David, C., Vortkamp, M., Graeve, M., et al. (2017). Ice algae-produced carbon is critical for overwintering of Antarctic krill Euphausia superba. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:310. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00310

Kraft, A., Berge, J., and Varpe, Ø, and Falk-Petersen, S. (2013). Feeding in Arctic darkness: mid-winter diet of the pelagic amphipods Themisto abyssorum and T. libellula. Mar. Biol. 160, 241–248. doi: 10.1007/s00227-012-2065-8

Kvernvik, A. C., Hoppe, C. J. M., Lawrenz, E., Prášil, O., Greenacre, M., Wiktor, J. M., et al. (2018). Fast reactivation of photosynthesis in arctic phytoplankton during the polar night. J. Phycol. 54, 461–470. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12750

Kvile, K. Ø, Ashjian, C., and Ji, R. (2019). Pan-Arctic depth distribution of diapausing Calanus copepods. Biol. Bull. 237, 76–89. doi: 10.1086/704694

Kwasniewski, S., Hop, H., Falk-Petersen, S., and Pedersen, G. (2003). Distribution of Calanus species in Kongsfjorden, a glacial fjord in Svalbard. J. Plankton Res. 25, 1–20. doi: 10.1093/plankt/25.1.1

Lee, R. F., Hagen, W., and Kattner, G. (2006). Lipid storage in marine zooplankton. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 307, 273–306. doi: 10.3354/meps307273

Leu, E., Brown, T. A., Graeve, M., Wiktor, J. M., Hoppe, C. J. M, Chierici, M., et al. (2020). Spatial and temporal variability of ice algal trophic markers- with recommendations about their application. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 8:676. doi: 10.3390/jmse8090676

Limoges, A., Masse, G., Weckström, K., Poulin, M., Ellegaard, M., Heikkilä, M., et al. (2018). Spring succession and vertical export of diatoms and IP25 in a seasonally ice-covered high Arctic fjord. Front. Earth Sci. 6:226. doi: 10.3389/feart.2018.00226

Marion, A., Harvey, M., Chabot, D., and Brêthes, J.-C. (2008). Feeding ecology and predation impact of the recently established amphipod, Themisto libellula, in the St. Lawrence marine system, Canada. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 373, 53–70. doi: 10.3354/meps07716

Mayzaud, P., and Boutoute, M. (2015). Dynamics of lipid and fatty acid composition of the hyperiid amphipod Themisto: a bipolar comparison with special emphasis on seasonality. Polar Biol. 38, 1049–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00300-015-1666-3

Melle, W., and Skjoldal, H. R. (1998). Reproduction and development of Calanus finmarchicus, C. glacialis and C. hyperboreus in the Barents Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 169, 211–228. doi: 10.3354/meps169211

Mikkelsen, D. M., Rysgaard, S., and Glud, R. N. (2008). Microalgal composition and primary production in Arctic sea ice: a seasonal study from Kobbefjord (Kangerluarsunnguaq), West Greenland. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 368, 65–74. doi: 10.3354/meps07627

Niehoff, B., Madsen, S., Hansen, B., and Nielsen, T. (2002). Reproductive cycles of three dominant Calanus species in Disko Bay, West Greenland. Mar. Biol. 140, 567–576. doi: 10.1007/s00227-001-0731-3

Nielsen, T. G., Kjellerup, S., Smolina, I., Hoarau, G., and Lindeque, P. (2014). Live discrimination of Calanus glacialis and C. finmarchicus females: can we trust phenological differences? Mar. Biol. 161, 1299–1306. doi: 10.1007/s00227-014-2419-5

Noyon, M., Gasparini, S., and Mayzaud, P. (2009). Feeding of Themisto libellula (Amphipoda Crustacea) on natural copepods assemblages in an Arctic fjord (Kongsfjorden, Svalbard). Polar Biol. 32, 1559–1570. doi: 10.1007/s00300-009-0655-9

Noyon, M., Narcy, F., Gasparini, S., and Mayzaud, P. (2012). Ontogenic variations in fatty acid and alcohol composition of the pelagic amphipod Themisto libellula in Kongsfjorden (Svalbard). Mar. Biol. 159, 805–816. doi: 10.1007/s00227-011-1856-7

Nyssen, F., Brey, T., Dauby, P., and Graeve, M. (2005). Trophic position of Antarctic amphipods- enhanced analysis by a 2-dimensional biomarker assay. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 300, 135–145. doi: 10.3354/meps300135

Onarheim, I. H., and Årthun, M. (2017). Toward an ice−free Barents Sea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 8387–8395. doi: 10.1002/2017GL074304

Parrish, C. C. (2009). “Essential fatty acids in aquatic food webs,” in Lipids in Aquatic Ecosystems, eds M. Kainz, M. T. Brett, and M. T. Arts (New York, NY: Springer), 309–326.

Pecuchet, L., Blanchet, M.-A., Frainer, A., Husson, B., Jørgensen, L. L., Kortsch, S., et al. (2020). Novel feeding interactions amplify the impact of species redistribution on an Arctic food web. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 4895–4906. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15196

Pedersen, G., Tande, K., and Ottesen, G. O. (1995). Why does a component of Calanus finmarchicus stay in the surface waters during the overwintering period in high latitudes?’ J. Mar. Sci. 52, 523–531. doi: 10.1016/1054-3139(95)80066-2

Poltermann, M. (2001). Arctic sea ice as feeding ground for amphipods–food sources and strategies. Polar Biol. 24, 89–96. doi: 10.1007/s003000000177

R Core Team (2017). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Reigstad, M., Wassmann, P., Wexels Riser, C., Øygarden, S., and Rey, F. (2002). Variations in hydrography, nutrients and chlorophyll a in the marginal ice-zone and the central Barents Sea. J. Mar. Syst. 38, 9–29. doi: 10.1016/S0924-7963(02)00167-7

Reuss, N., and Poulsen, L. (2002). Evaluation of fatty acids as biomarkers for a natural plankton community. A field study of a spring bloom and a post-bloom period off West Greenland. Mar. Biol. 141, 423–434. doi: 10.1007/s00227-002-0841-6

Ruess, L., and Müller-Navarra, D. (2019). Essential biomolecules in food webs. Front. Ecol. Evol. 7:269. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00269

Sakshaug, E., and Slagstad, D. (1992). Sea ice and wind: effects on primary productivity in the Barents Sea. Atmos. Ocean 30, 579–591. doi: 10.1080/07055900.1992.9649456

Sargent, J. R., and Falk-Petersen, S. (1988). “The lipid biochemistry of calanoid copepods,” in Biology of Copepods, eds G. A. Boxshall and H. K. Schminke (Dordrecht: Springer), 101–114.

Schmid, M. S., Maps, F., and Fortier, L. (2018). Lipid load triggers migration to diapause in Arctic Calanus copepods- insights from underwater imaging. J. Plankton Res. 40, 311–325. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fby012

Schmidt, K., Brown, T. A., Belt, S. T., Ireland, L. C., Taylor, K. W. R., Thorpe, S. E., et al. (2018). Do pelagic grazers benefit from sea ice? Insights from the Antarctic sea ice proxy IPSO25. Biogeosciences 15, 1987–2006. doi: 10.5194/bg-15-1987-2018

Scott, C. L., Falk-Petersen, S., Sargent, J. R., Hop, H., Lønne, O. J., and Poltermann, M. (1999). Lipids and trophic interactions of ice fauna and pelagic zooplankton in the marginal ice zone of the Barents Sea. Polar Biol. 21, 65–70. doi: 10.1007/s003000050335

Scott, C. L., Kwasniewski, S., Falk-Petersen, S., and Sargent, J. R. (2000). Lipids and life strategies of Calanus finmarchicus, Calanus glacialis and Calanus hyperboreus in late autumn, Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Polar Biol. 23, 510–516. doi: 10.1007/s003000000114

Søreide, J. E., Falk-Petersen, S., Hegseth, E. N., Hop, H., Carroll, M. L., Hobson, K. A., et al. (2008). Seasonal feeding strategies of Calanus in the high-Arctic Svalbard region. Deep Sea Res. II 55, 2225–2244. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.05.024

Søreide, J. E., Leu, E., Berge, J., Graeve, M., and Falk-Petersen, S. (2010). Timing of blooms, algal food quality and Calanus glacialis reproduction and growth in a changing Arctic. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 3154–3163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02175.x

Spreen, G., Kaleschke, L., and Heygster, G. (2008). Sea ice remote sensing using AMSR−E 89−GHz channels. J. Geophys. Res. (Oceans) 113:C02S03. doi: 10.1029/2005JC003384

Stonik, V., and Stonik, I. (2015). Low-molecular-weight metabolites from diatoms: structures, biological roles and biosynthesis. Mar. Drugs 13, 3672–3709. doi: 10.3390/md13063672

Stramska, M., and Bialogrodzka, J. (2016). Satellite observations of seasonal and regional variability of particulate organic carbon concentration in the Barents Sea. Oceanologia 58, 249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.oceano.2016.04.004

Stübing, D., Hagen, W., and Schmidt, K. (2003). On the use of lipid biomarkers in marine food web analyses: an experimental case study on the Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48, 1685–1700. doi: 10.4319/lo.2003.48.4.1685

Tamelander, T., Renaud, P. E., Hop, H., Carroll, M. L., Ambrose, W. G. Jr., and Hobson, K. A. (2006). Trophic relationships and pelagic–benthic coupling during summer in the Barents Sea Marginal Ice Zone, revealed by stable carbon and nitrogen isotope measurements. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 310, 33–46. doi: 10.3354/meps310033

Vader, A., Amundsen, R., Marquardt, M., and Bodur, Y. (2021). Chlorophyll A and phaeopigments, Nansen Legacy. Nor. Mar. Data Centre (in press). doi: 10.21335/NMDC-1477580440

Van Leeuwe, M. A., Tedesco, L., Arrigo, K. R., Assmy, P., Campbell, K., Meiners, K. M., et al. (2018). Microalgal community structure and primary production in Arctic and Antarctic sea ice: a synthesis. Elementa 6:4. doi: 10.1525/elementa.267

Verity, P. G., Wassmann, P., Frischer, M. E., Howard-Jones, M. H., and Allen, A. E. (2002). Grazing of phytoplankton by microzooplankton in the Barents Sea during early summer. J. Mar. Syst. 38, 109–123. doi: 10.1016/S0924-7963(02)00172-0

Vinogradov, G. M. (1999). Deep-sea near-bottom swarms of pelagic amphipods Themisto: observations from submersibles. Sarsia 84, 465–467. doi: 10.1080/00364827.1999.10807352

von Quillfeldt, C. H. (2000). Common diatom species in Arctic spring blooms: their distribution and abundance. Bot. Mar. 43, 499–516. doi: 10.1515/BOT.2000.050

Wang, S. W., Budge, S. M., Iken, K., Gradinger, R. R., Springer, A. M., and Wooller, M. J. (2015). Importance of sympagic production to Bering Sea zooplankton as revealed from fatty acid-carbon stable isotope analyses. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 518, 31–50. doi: 10.3354/meps11076

Wang, S. W., Springer, A. M., Budge, S. M., Horstmann, L., Quakenbush, L. T., and Wooller, M. J. (2016). Carbon sources and trophic relationships of ice seals during recent environmental shifts in the Bering Sea. Ecol. Appl. 26, 830–845. doi: 10.1890/14-2421

Wassmann, P., Reigstad, M., Haug, T., Rudels, B., Carroll, M. L., Hop, H., et al. (2006). Food webs and carbon flux in the Barents Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 71, 232–287. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2006.10.003

Wassmann, P., and Slagstad, D. (1993). Seasonal and annual dynamics of particulate carbon flux in the Barents Sea. Polar Biol. 13, 363–372. doi: 10.1007/BF01681977

Watts, J., and Tarling, G. A. (2012). Population dynamics and production of Themisto gaudichaudii (Amphipoda, Hyperiidae) at South Georgia, Antarctica. Deep Sea Res. II 59, 117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2011.05.001

Werner, I., and Auel, H. (2005). Seasonal variability in abundance, respiration and lipid composition of Arctic under-ice amphipods. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 292, 251–262. doi: 10.3354/meps292251

Werner, I., and Gradinger, R. (2002). Under-ice amphipods in the Greenland Sea and Fram Strait (Arctic): environmental controls and seasonal patterns below the pack ice. Mar. Biol. 40, 317–326. doi: 10.1007/s00227-001-0709-1

Weydmann, A., Søreide, J. E., Kwaśniewski, S., Leu, E., Falk-Petersen, S., and Berge, J. (2013). Ice-related seasonality in zooplankton community composition in a high Arctic fjord. J. Plankton Res. 35, 831–842. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbt031