94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci., 06 July 2021

Sec. Marine Biogeochemistry

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.637970

This article is part of the Research TopicPredicting Hydrocarbon Fate in the Ocean: Processes, Parameterizations, and Coupled ModelingView all 12 articles

Isabel C. Romero1*

Isabel C. Romero1* Jeffrey P. Chanton2

Jeffrey P. Chanton2 Gregg R. Brooks3

Gregg R. Brooks3 Samantha Bosman2

Samantha Bosman2 Rebekka A. Larson3

Rebekka A. Larson3 Austin Harris4

Austin Harris4 Patrick Schwing1,3

Patrick Schwing1,3 Arne Diercks4

Arne Diercks4Following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill (DWHOS), the formation of an unexpected and extended sedimentation event of oil-associated marine snow (MOSSFA: Marine Oil Snow Sedimentation and Flocculent Accumulation) demonstrated the importance of biology on the fate of contaminants in the oceans. We used a wide range of compound-specific data (aliphatics, hopanes, steranes, triaromatic steroids, polycyclic aromatics) to chemically characterize the MOSSFA event containing abundant and multiple hydrocarbon sources (e.g., oil residues and phytoplankton). Sediment samples were collected in 2010–2011 (ERMA-NRDA programs: Environmental Response Management Application – Natural Resource Damage Assessment) and 2018 (REDIRECT project: Resuspension, Redistribution and Deposition of Deepwater Horizon recalcitrant hydrocarbons to offshore depocenter) in the northern Gulf of Mexico to assess the role of biogenic and chemical processes on the fate of oil residues in sediments. The chemical data revealed the deposition of the different hydrocarbon mixtures observed in the water column during the DWHOS (e.g., oil slicks, submerged-plumes), defining the chemical signature of MOSSFA relative to where it originated in the water column and its fate in deep-sea sediments. MOSSFA from surface waters covered 90% of the deep-sea area studied and deposited 32% of the total oil residues observed in deep-sea areas after the DWHOS while MOSSFA originated at depth from the submerged plumes covered only 9% of the deep-sea area studied and was responsible for 15% of the total deposition of oil residues. In contrast, MOSSFA originated at depth from the water column covered only 1% of the deep-sea area studied (mostly in close proximity of the DWH wellhead) but was responsible for 53% of the total deposition of oil residues observed after the spill in this area. This study describes, for the first time, a multi-chemical method for the identification of biogenic and oil-derived inputs to deep-sea sediments, critical for improving our understanding of carbon inputs and storage at depth in open ocean systems.

In marine systems, hydrocarbons are composed of a complex mixture of compounds that originated biologically from autochthonous (e.g., phytoplankton, microbes, seeps) and allochthonous (e.g., terrestrial, anthropogenic) sources. Organic particles that reach the seafloor undergo weathering; still, the chemical signatures related to their source and transformation processes are preserved and can be used to assess the contribution from different sources to the global carbon budget for modern sediments as well as for historical palaeoceanographic reconstructions (Zonneveld et al., 2009; Canuel and Hardison, 2016; Bianchi et al., 2018; Larowe et al., 2020). Recently, efforts have focused on identifying the chemical signature of multiple sources in sinking organic particles in the water column or on the seafloor to better understand biogenic-petrogenic interactions that influenced carbon preservation and ecosystem health in areas with abundant natural seeps and oil exploration (Adhikari et al., 2015, 2016; Romero et al., 2017; Chanton et al., 2018; White et al., 2019; Bosman et al., 2020). Despite multiple studies looking at the fate of organic matter in the environment, the identification of robust chemical markers for source apportionment and transport processes of oil residues from surface waters to deep-sea sediments is still not available.

Differentiating hydrocarbon sources is important because it provides crucial information about sea surface to seafloor connectivity (e.g., organic matter transport processes and carbon sequestration). For example, hydrocarbons are significant components in the upper ocean carbon cycle due to the pervasive natural contribution from phytoplankton (Middleditch et al., 1979; Kameyama et al., 2009; Lea-smith et al., 2015) as well as in specific regions by large extensions of oil residues released from natural seeps (MacDonald et al., 2015) or as a result of oil spills (e.g., Deepwater Horizon oil spill – DWHOS: surface slicks covered 11200 km2, MacDonald et al., 2015; submerged plumes covered ∼73200 km2, Du and Kessler, 2012). Also, it has been observed that multiple hydrocarbon sources can interact and form biogenic-petrogenic aggregates in association with natural oil seeps, important for understanding hydrocarbon degradation and fate in the water column (D’souza et al., 2016). Furthermore, high-resolution analysis of deep-sea sediments collected in the aftermath of the DWHOS in the northern Gulf of Mexico (nGoM), revealed a large deposition of aggregates composed of inorganic and biogenic material mixed with oil residues containing varied chemical signatures (Brooks et al., 2015; Romero et al., 2015). These findings were supported by multiple observations of co-occurring phytoplankton blooms and surface oil-slicks during the DWHOS (Hu et al., 2011; Ziervogel et al., 2012; Passow et al., 2012; Vonk et al., 2015; Daly et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2016; Quigg et al., 2020). This enhanced sedimentation event was known as MOSSFA (Marine Oil Snow Sedimentation and Flocculent Accumulation) and consisted of oil residues mixed with organic and inorganic particles, including bacteria, phytoplankton, microzooplankton, zooplankton fecal pellets, detritus, and terrestrially derived lithogenic particles (Daly et al., 2020). Moreover, the deposition of oil residues as marine oil snow (MOS) and/or oil-mineral aggregates (OMAS) is not specific to the DWHOS (e.g., Niu et al., 2010; Vonk et al., 2015; Romero et al., 2016). Therefore, a better understanding of the conditions that favor MOSSFA events and its role in the fate of oil residues at depth is warranted for improving response efforts in the event of future oil spill accidents.

Offshore in the nGoM, MOSSFA was responsible for the deposition of ∼4–9% of the total oil discharged and not recovered from the DWHOS (Chanton et al., 2015; Romero et al., 2017). As a result, approximately a fourfold increase in sedimentary mass accumulation rates (Brooks et al., 2015) and 2–6 fold increase in hydrocarbon concentrations were observed in deep-sea sediments (Romero et al., 2015, 2017). Based on initial estimates of combined sedimentology, geochemical, and biological approaches, MOSSFA occurred over a 4–5-month period after the DWHOS (Brooks et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2016). However, Larson et al. (2018) found that stabilization of sedimentation in the nGoM did not occur until 2013. This is supported by numerous studies showing that oil residues from the DWHOS were still in the water column in the years following the spill (Adhikari et al., 2015, 2016; Walker et al., 2017; Romero et al., 2018). MOSSFA ultimately resulted in a widespread of faunal exposures to oil residues from the water column (Murawski et al., 2014; Quintana-Rizzo et al., 2015; Ainsworth et al., 2018; Romero et al., 2018, 2020; Pulster et al., 2020; Sutton et al., 2020) to benthic environments (Montagna et al., 2013; Baguley et al., 2015; Schwing et al., 2015, 2017, 2018; Rohal et al., 2020).

Furthermore, because hydrocarbons from the DWHOS were released at 1,500 m depth, multiple chemical mixtures within the water column were formed during transport of the spilled oil to the surface, including partitioning into dissolved and undissolved hydrocarbon mixtures (Socolofsky et al., 2011; Ryerson et al., 2012; Lindo-Atichati et al., 2014). The partitioning of hydrocarbons into chemical mixtures is not unique to the DWHOS, as it has been observed previously from natural releases (Harvey et al., 1979), shallower marine oil spills (Boehm and Flest, 1982; Elordui-zapatarietxe et al., 2010), and experimental discharges (Johansen et al., 2003). Specific to the DWHOS, based on the composition and concentration of hydrocarbons in each chemical mixture, it was calculated that of the total leaked mass ∼10% formed surface slicks composed of insoluble and non-volatile compounds ([≥]C12), and ∼36% formed deep submerged plumes of dissolved and dispersed compounds (<C12) (Ryerson et al., 2012). Although increased concentrations outside of the submerged plumes in the water column were observed (e.g., Valentine et al., 2010; Joye et al., 2011; Romero et al., 2018), these residues were not accounted for in models or oil fate assessment studies. Also, high concentrations of MOS were observed in the vicinity of the surface oil slicks and the submerged oil plumes (e.g., Passow et al., 2012; Daly et al., 2016), but the role of MOSSFA from these different chemical oil mixtures have not been elucidated to date. This is important for further understating the efficacy of natural and chemical dispersed processes to retain oil residues at depth. Altogether, to date, the role of MOSSFA on the deposition of biogenic-petrogenic aggregates from different water masses containing distinct chemical mixtures (e.g., surface: oil slicks, ∼900–1300 m depth: submerged plumes) is not known.

In this study, we use a wide range of data collected after the DWHOS (n-alkanes, isoprenoids, PAHs: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons including alkylated homologs, hopanes, steranes, and TAS: triaromatic steroids) to chemically characterize the MOSSFA event, which contained abundant and multiple hydrocarbon sources (e.g., oil residues and phytoplankton). The primary goal of this study was to identify molecular markers of biogenic and oil-derived hydrocarbons in deep-sea sediments collected in the aftermath of the DWHOS (2010–2011; ERMA and Gulf Science publicly available data) and years after the spill (2018; REDIRECT project). The chemical data from samples collected in 2010–2011 were used to determine where the hydrocarbons originated in the water column (surface vs. depth). This distinction was possible to observe because the surface slicks had a different chemical composition of oil-derived hydrocarbons than the submerged plumes at depth (insoluble and non-volatile compounds vs dissolved and dispersed compounds, respectively; Ryerson et al., 2012). The chemical data from samples collected in 2018 were used to improve our understanding of the changes in hydrocarbon composition after burial in deep-sea sediments and the efficacy of molecular markers to differentiate biogenic and oil-derived hydrocarbons after years of weathering. The results generated, define the chemical signature of MOSSFA relative to where it originated in the water column and its fate in deep-sea sediments, fundamental for better understanding hydrocarbon cycling in the oceans.

The chemical data used in this study, was collected from July 2010 to September 2011 offshore in the nGoM (deep-sea sediments, N = 239 sites, Figure 1). This dataset was obtained from publicly available databases such as ERMA Deepwater Gulf Response1 (downloaded on June 2013) and Gulf Science2 (downloaded on March 2013). This dataset can now be found at the DIVER database3. The different databases used similar chemical protocols for the analysis of hydrocarbons in sediment samples (GCMS-SIM analysis; protocols: 8270D and 8015C). Compounds include aliphatics (C12–C37 n-alkanes, isoprenoids), PAHs (2–6 ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons including alkylated homologs), biogenic PAHs (retene, perylene), and biomarkers like hopanes (C27–C35), steranes (C27–C29), and triaromatic steroids (C26–C28) (Supplementary Table 1). To assure reliable results, a strict chain of custody, calibration check samples, method blanks, and matrix spike samples were conducted. A more detailed explanation of QA/QC protocol and sample collection can be found in the Analytical Quality Assurance Plan report for Mississippi Canyon 252 (NOAA, 2011) and Stout and Payne (2016a). Only sediment cores with a full analysis of >C9 hydrocarbons and containing oil residues from the DWHOS were used in this study.

Figure 1. Location of studied sites in the nGoM where sediment cores were collected between 2010 and 2011 (green circles; ERMA and Gulf Science publicly available data) and 2018 (orange circles; REDIRECT project). The Deepwater Horizon wellhead is shown as a black circle.

The chemical data from samples collected in 2010–2011 were used to identify molecular markers of biogenic and oil-derived hydrocarbons from the chemical mixtures that formed during transport of the spilled oil to the surface (Socolofsky et al., 2011; Ryerson et al., 2012; Lindo-Atichati et al., 2014). In order to establish the connectivity between water column and sedimentary organic matter during 2010–2011, we assumed that the molecular signature of the chemical mixtures (e.g., surface slicks, submerged plumes) was not affected significantly (1) during the MOSSFA event (transport of oil residues to the seafloor), and (2) after deposition as observed in Romero et al. (2015). Here, we used chemical ratios to identify molecular signatures of MOSSFA rather than hydrocarbon concentrations, which were shown to be affected mostly during transport in the water column and by slow in situ biodegradation on the seafloor (Romero et al., 2017). We used the same dataset analyzed in Romero et al. (2017). Only the sites located at depths > 200 m (deep-sea area) that were contaminated with oil residues from the DWHOS (see details in Romero et al., 2017) are included here in this study (Figure 1). Data from each site, correspond to sediment cores divided into the surface sediment layer (top 1 cm) and downcore layer (1–3 cm). The surface sediment layer represents recently deposited organic matter on the seafloor due to the increased sedimentation event that occurred during the DWHOS (Brooks et al., 2015; Chanton et al., 2015; Romero et al., 2015; Stout and Payne, 2016a). The layer 1–3 cm in each core studied corresponds to sediments deposited before the DWHOS (Brooks et al., 2015; Romero et al., 2015, 2017).

We collected and analyzed deep-sea sediment cores that were sampled during the REDIRECT project (Resuspension, Redistribution, and Deposition of the Deepwater Horizon Recalcitrant Hydrocarbons to offshore Depocenters) on the R/V Point Sur cruise (18–25 in May of 2018) using a multi corer (MC-800) in the nGoM (N = 11 sites, Figure 1). Sediment cores were extruded at 2 mm intervals for surficial sediment (0–10 cm), and at 5 mm intervals to the base of the core using Schwing et al. (2016) method.

Samples were chemically analyzed at the Marine Environmental Chemistry Laboratory (MECL, College of Marine Science, University of South Florida) for hydrocarbons following modified EPA methods and QA/QC protocols (GCMSMS-MRM analysis; protocols: 8270D and 8015C). Targeted compounds (Supplementary Table 1) include aliphatics (C12–C37 n-alkanes, isoprenoids), PAHs (2-6 ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons including alkylated homologs), biogenic PAHs (retene, perylene), and biomarkers like hopanes (C27–C35), steranes (C27–C29), and triaromatic steroids (TAS; C20–C28). Freeze-dried samples were extracted using an Accelerated Solvent Extraction system (ASE 200®, Dionex) following a one-step extraction and clean up procedure using a predetermined packing of the extraction cells (Romero et al., 2018). Hydrocarbon compounds were quantified using GC/MS/MS (Agilent 7680B gas chromatograph coupled with an Agilent 7010 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer) in selected reaction monitoring mode (SRM) to target multiple chemical fractions in one-run-step. Molecular ion masses for hydrocarbon compounds were selected from previous studies (Romero et al., 2015, 2017; Sørensen et al., 2016; Adhikari et al., 2017) and can be found in the Supplementary Table 2. For accuracy and precision of analyses, we included laboratory blanks, spiked controls samples, tuned MS/MS to PFTBA (perfluorotributylamine) daily, used standard reference material (NIST 2779) daily, and reanalyzed sample batches when replicated standards exceeded ± 20% of relative standard deviation (RSD), and/or if recoveries were low. Quantitative determination of compounds was conducted using response factors (RFs) calculated from the certified standard NIST 2779.

The samples collected in 2018 were used to study how weathering processes (e.g., biodegradation) affected the chemical composition of hydrocarbons after years of being buried in deep-sea sediments. Similar to the chemical data from 2010 to 2011, we included only the sites that contained oil residues from the DWHOS (N = 11 sites, Figure 1), as determined previously using established hopane and sterane ratios (Diercks et al., 2021). Also, for the sediment cores collected in 2018, we used only samples that were deposited between 2010 and 2013 (N = 72 samples), the period in which enhanced sedimentation was observed due to the MOSSFA event (Larson et al., 2018). Sediment cores were analyzed for short-lived radioisotopes and 210Pbxs geochronologies were utilized to identify the sediment layer that was deposited during the period of 2010–2013. Briefly, the activities of the 214Pb (295 keV), 214Pb (351 keV), and 214Bi (609 keV) were averaged as a proxy for the Radium-226 (226Ra) activity of the sample or the “supported” Lead-210 (210PbSup) that is produced in situ (Baskaran et al., 2014; Swarzenski, 2014). The 210PbSup activity was subtracted from the 210PbTot activity to calculate the “unsupported” or “excess” Lead-210 (210Pbxs), which is used for dating within the last ∼100 years. The Constant Rate of Supply (CRS) model was used to assign specific ages to sedimentary intervals within 210Pbxs profiles (Appleby and Oldfield, 1983; Binford, 1990). Short-lived radioisotope results and geochronologies for the sites studied are found in the Supplementary Tables 3–13.

Reported hydrocarbon concentrations are expressed as sediment dry weight concentrations. Low molecular weight (LMW) PAHs were calculated as the sum of all 2–3 ring PAHs, while high molecular weight (HMW) PAHs were calculated as the sum of 4–6 ring PAHs (all including alkylated homologs). LMW alkanes include the sum of C12–C23 n-alkanes, while HMW alkanes include the sum of C24–C37 n-alkanes. Hopanes, steranes and triaromatic hydrocarbons (TAS) were calculated as the sum of C23–C25, C27–C29, and C20–C28 compounds, respectively.

Multiple diagnostic ratios were calculated (Table 1) to characterize the chemical signature of the MOSSFA event relative to where it originated in the water column and its fate in sediments. PAH compounds were used to identify natural sources (%Re; Abrajano and Yan, 2003), discriminate petrogenic from pyrogenic sources (low vs. high values of the PI and Parent/alkyl ratios; Wang et al., 1999a; Romero et al., 2015, 2017), detect sources of dissolved oil-derived PAHs (N0-N1/T19), identify undissolved PAHs in the water column not exposed to the atmosphere (De/T19), and distinguish weathered samples (LMW/HMW PAHs, %5–6 ring PAHs, %Chrysene; Wang and Fingas, 2003; Liu et al., 2012; Romero et al., 2015, 2017; Table 1). Naphthalene compounds (e.g., N0, N1) were found to be abundant in the submerged plumes formed during the DWHOS (29.4–189.0 ppb; Diercks et al., 2010) due to the partitioning of more soluble PAHs during transport to surface waters (Ryerson et al., 2012) as observed as well in other marine oil spills (Gonzalez et al., 2006); therefore, they can be used as indicators of PAH inputs from near sources at depth (e.g., seeps, DWHOS wellhead). Other compounds, such as decalins (ratio: De/T19) can be used to identify the origin of oil residues in the water column due to their high evaporative (boiling point: 190°C) and low solubility (log Kow: 4.20) properties, relative to other compounds such as naphthalene (boiling point: 218°C, log Kow: 3.30). Consequently, high values of De/T19 can only be found in sediments if oil residues came from a MOSSFA event which originated at depth (didn’t reach the surface and were not entrained in the submerged plumes).

Alkane compounds were used to separate biogenic inputs in the presence of oil (ratio (C15,17)/(C14,16,18; White et al., 2019), discern phytoplankton sources from microbial and oil (CPIC15–C19; Xing et al., 2011), differentiate natural sources from oil (CPIC14–C23, CPIC25–C33; Bray and Evans, 1961; Xing et al., 2011; Romero et al., 2015; Herrera-Herrera et al., 2020), and distinguish weathered samples [LMW/HMW alkanes, (C12–C13)/T19] (Table 1).

We used hopane compounds to identify oil residues from the DWHOS using diagnostic ratios for oil identification that have been reported previously (Mulabagal et al., 2013; Aeppli et al., 2014; Romero et al., 2015, 2017; Wang et al., 2016; Diercks et al., 2021; Table 1). Also, we used ratios that compare hopane compounds that are more susceptible to weathering to recalcitrant hopanes (T30–T31/T19, T22–T33/T19, T32–T35/T19; Table 1; Aeppli et al., 2014; Romero et al., 2017). In addition, high values of %Terp typically denote potential interferences to hopanes like T20, T26, T30, and T35 (Table 1) due to relatively large inputs of modern biomarkers from bacterial or plant biomass (Simoneit et al., 1985, 2020; Hood et al., 2002; Dembicki, 2010; Stout and German, 2018).

For statistical analysis, all data were log-transformed or square-root transformed (if data include zeroes) to approach normal distribution. Differences in mean concentrations and ratios with respect to periods and categories were tested by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s HSD test. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Figures and statistical analyses were completed using JMP Pro 14 for Mac (JMP®, Version Pro 14. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States, 1989–2019). Average values are shown as arithmetic mean ± 95% confidence interval.

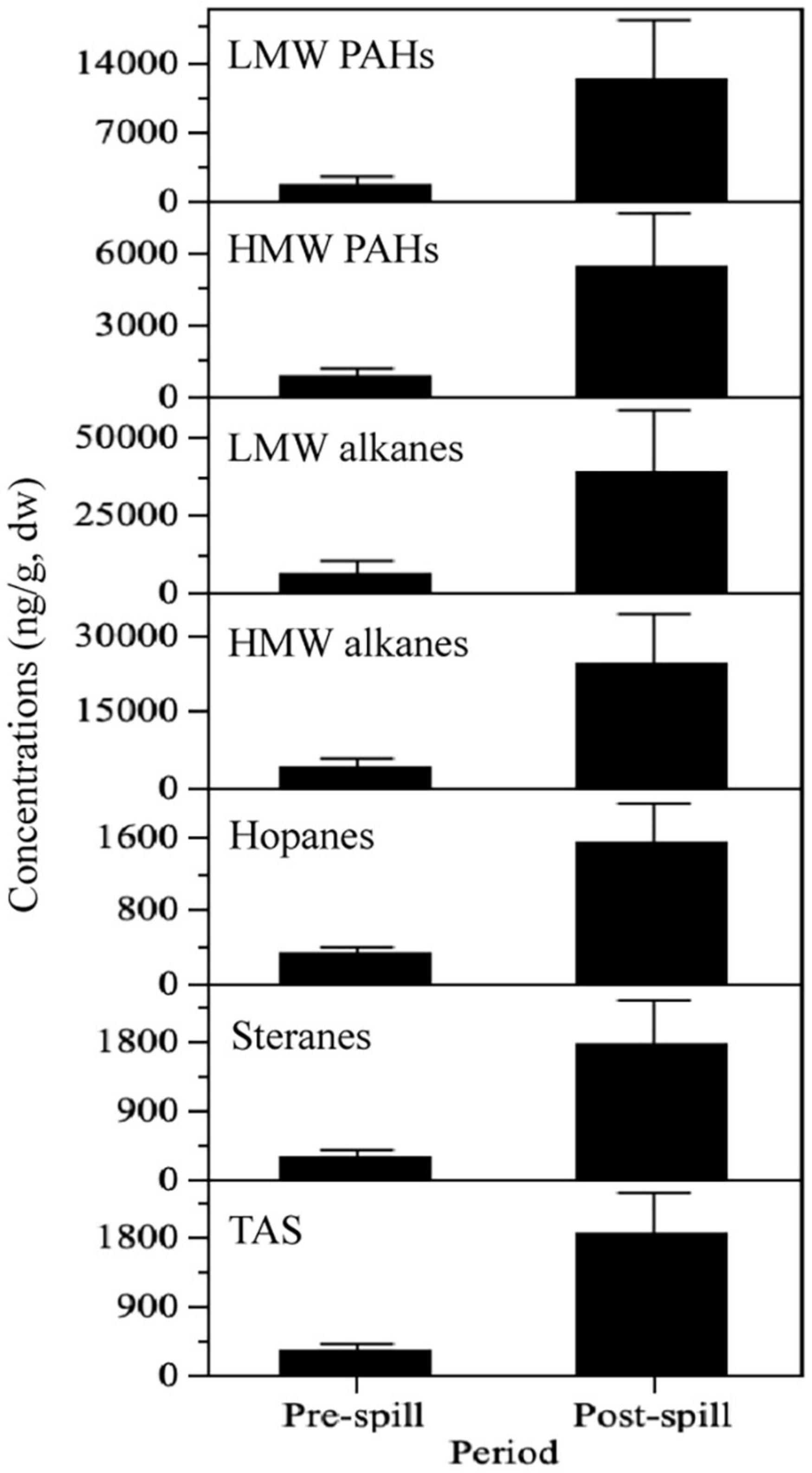

Sediment cores collected in 2010–2011 showed significantly higher hydrocarbon concentrations (sum of PAHs, n-alkanes, hopanes, steranes, TAS) in the layer deposited post-spill (0–1 cm surface sediments; 99905 ± 44270 ng/g) compared to the sediments deposited pre-spill (1–3 cm layer; 16454 ± 8594 ng/g) (p < 0.001). This was also observed for specific hydrocarbon compound groups, including for low and high molecular weight (LMW and HMW, respectively) PAHs and n-alkanes (p < 0.001; Figure 2). Overall, the mean concentrations of hydrocarbon compound groups were from 5 to 7 times higher post-spill (Figure 2). Interestingly, the calculated 95% confidence intervals in Figure 2 are very high in the post-spill sediment layer, explained by a large range in the concentration of hydrocarbons (sum of all compounds: 324 – 5533998 ng/g) and compound groups (Supplementary Table 14).

Figure 2. Hydrocarbon concentrations (ng/g, dw) by periods from sediment samples collected in 2010–2011 in the nGoM. Post-pill denotes concentrations in surface sediments (top 1 cm layer in the sediment cores), and pre-spill indicate concentrations in downcore layers (1–3 cm layer). LMW PAHs: 2–3 rings, HMW PAHs: 4–6 rings, LMW alkanes: C12–C23 n-alkanes, HMW alkanes: C24–C37 n-alkanes, hopanes: C23–C35, steranes: C27–C29, and TAS: C26–C28. Data shown as mean ± 95% confidence interval.

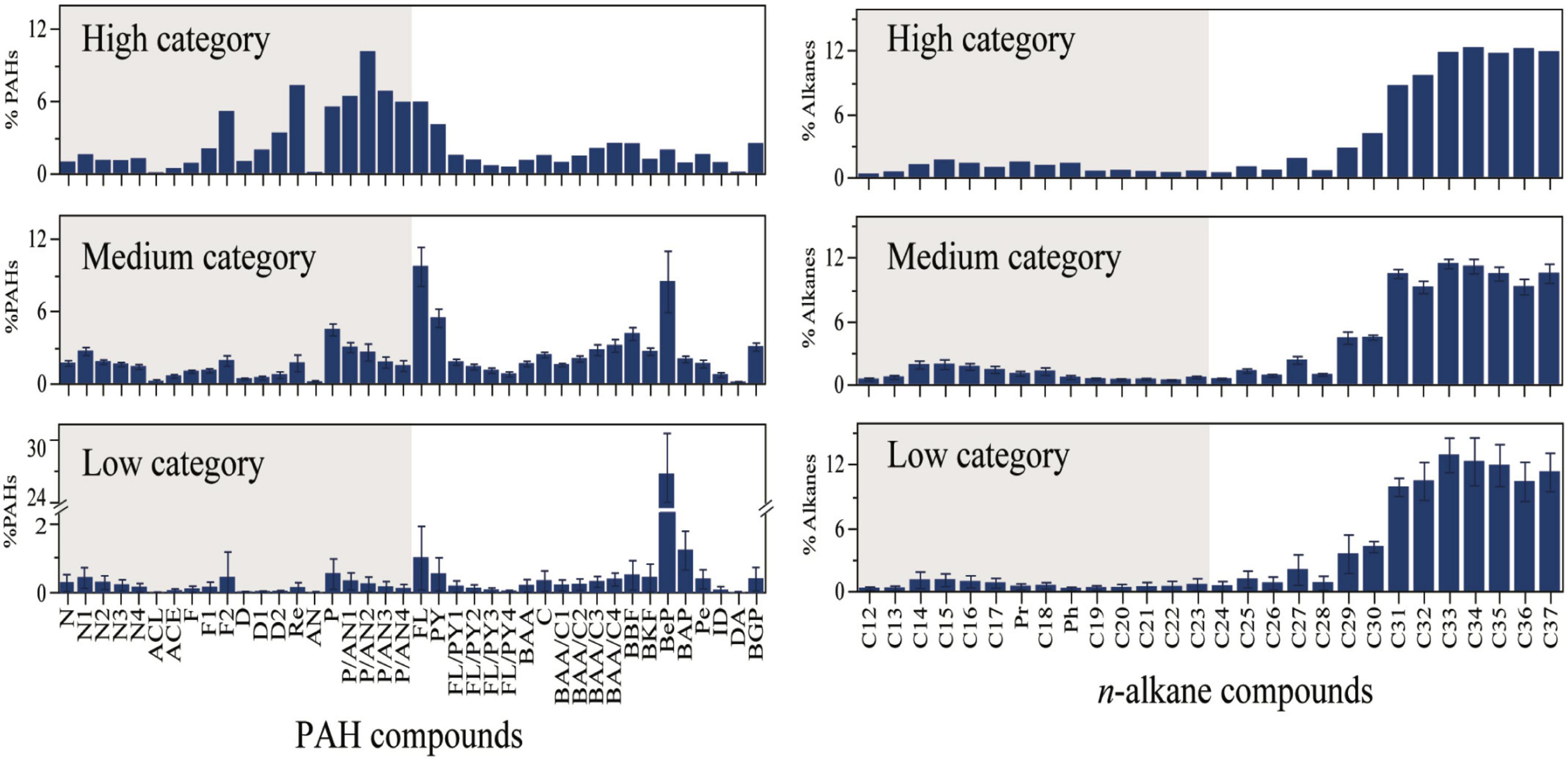

To better understand the large variation in hydrocarbons observed in the post-spill sediment layer, we plotted the most abundant compounds in the MC252 crude oil (LMW PAHs and LMW alkanes) by the hydrocarbon ranges observed in the studied area (Supplementary Figure 1). The distribution observed indicates a trend, described by low, medium, and high content of LMW PAHs (20.1 ± 1.4%, 35.6 ± 5.0%, and 68.0 ± 3.6%, respectively) and LMW alkanes (10.9 ± 1.1%, 22.2 ± 6.0%, and 63.9 ± 7.0%, respectively) (Supplementary Figure 1). By comparison, the category with low content of LMW compounds comprised 81% of the sites sampled. The medium and high categories only contained 12 and 7% of the sites sampled, respectively. No spatial trend was observed among the LMW categories within the studied area, which covers up to 180 km from the DWH rig from 200 to 2400 m depth (Supplementary Figure 2).

Using biomarker diagnostic ratios for oil source identification, we found that the three categories identified (low, medium, and high content of LMW compounds) lie within the values of the MC252 oil standard, indicating a match with the spilled oil from the DHWOS (Supplementary Figure 3). The category with low content of LMW compounds was the only category with significantly lower values for the ratios (T30 + T31)/T19 and (T32 + T33)/T19 (P < 0.01; Supplementary Figure 3). This preferential degradation of hopanoids > C31 (T30 – T33) over C30 hopane (T19) indicates significant weathering effects only in the low content category (from for example, biodegradation, dissolution), probably due to the large dispersion observed in this category (samples found up to 175 km from the DWH wellhead) (Figure 1; Supplementary Figure 2).

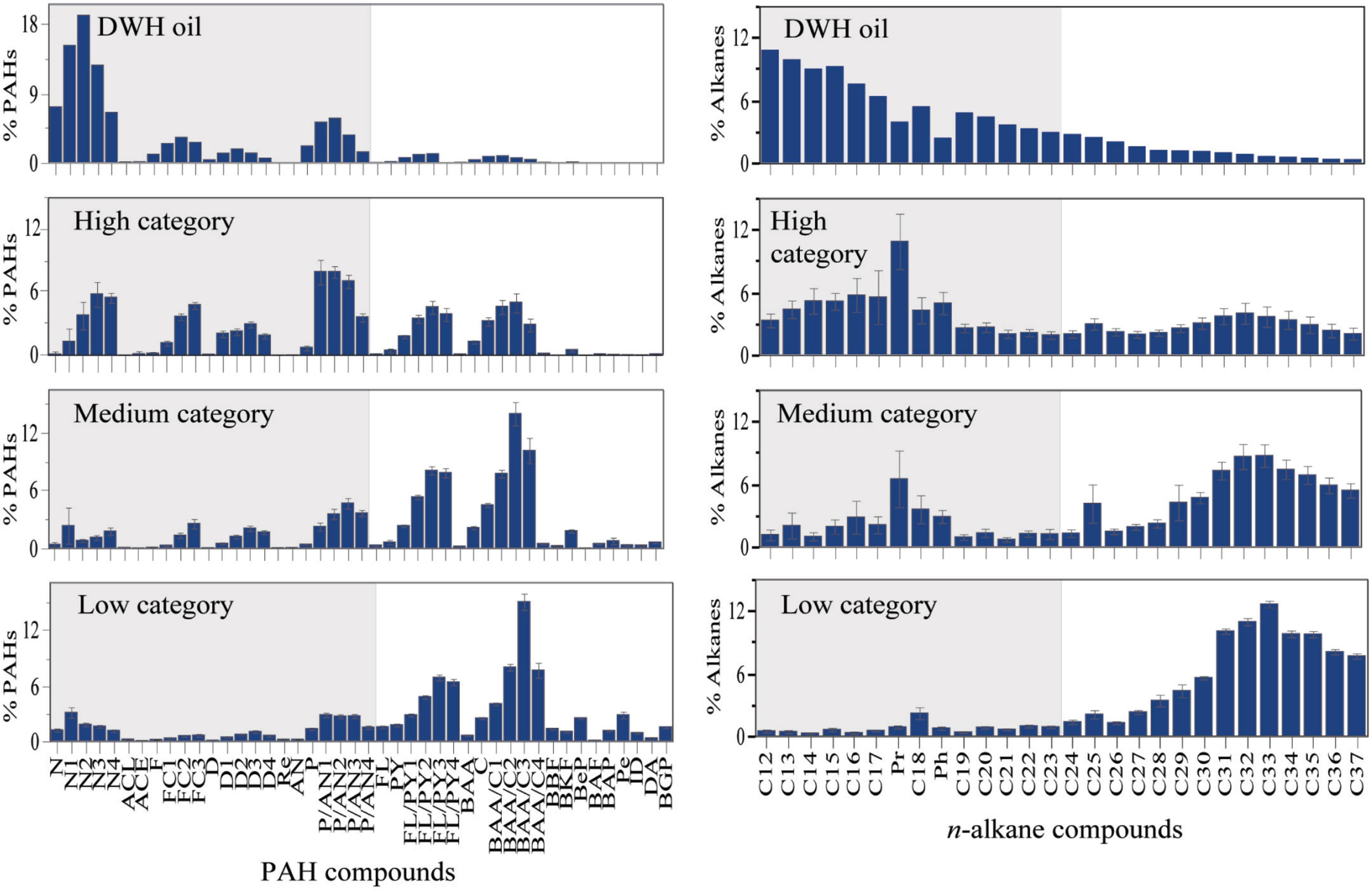

The composition of PAHs and alkanes also indicates weathered petrogenic samples relative to DWH oil (Figure 3). PAHs in the DWH oil are dominated by LMW compounds (94%), with a significant lower relative abundance in the high (68%), medium (36%), and low (21%) categories (Figure 3). A similar trend was also observed for the relative abundance of LMW alkanes (DWH oil: 84%; high category: 64%; medium category: 22%; low category: 11%), indicating significant weathering effects in the sediment samples (Figure 3). In addition, each category has a distinct composition of PAHs and alkanes (Figure 3). For example, the PAH distribution in the category with a high content of LMW compounds is dominated by alkyl homologs of LMW and HMW PAHs, while in the medium category phenanthrenes and 4-ring PAHs predominate (Figure 3). The category containing low content of LMW PAHs show an increase in parent compounds (e.g., FL, PY, BAA, BBF, BAP), and perylene (Pe) and naphthalene (N0, N1–N4) compounds as a consequence of weathering processes (e.g., dispersion, degradation) and mixing with other sources in the environment (e.g., seeps). For alkanes, weathering is evident with pristine (Pr) higher than C17 n-alkane in all categories (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Relative abundance of PAHs and n-alkanes by categories of %LMW compounds: high (PAHs: 68.0 ± 3.6%; alkanes: 63.9 ± 7.0%), medium (PAHs: 35.6 ± 5.0%; alkanes: 22.2 ± 6.0%), and low (PAHs: 20.1 ± 1.4%; alkanes: 10.9 ± 1.1%). Also, crude oil is shown as non-weathered DWH oil standard (NIST 2779). Contaminated sediments were collected in 2010–2011 in the nGoM (surface sediment layer). Data shown as mean ± 95% confidence interval.

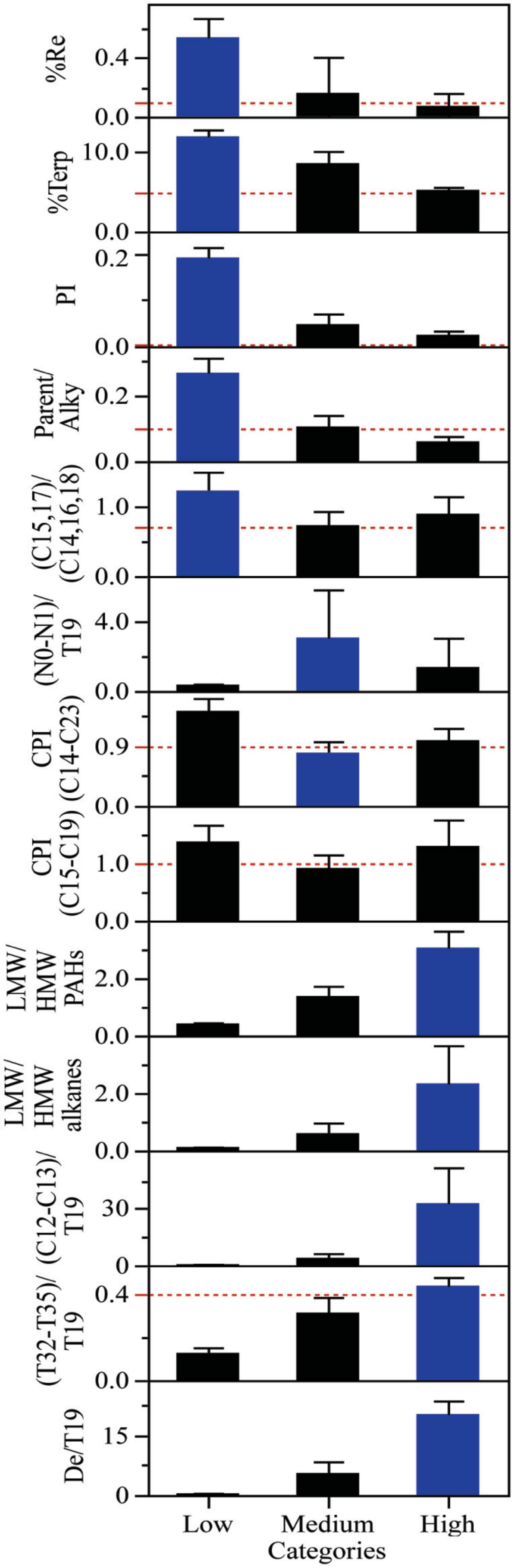

Additionally, diagnostic ratios such as %retene and %terpenoids (T20, T26, T30, T35) were significantly higher in the category with low content of LMW compounds relative to the other categories and the DWH oil (∼3 and ∼2 times, respectively; P < 0.001; Figure 4). These ratios indicate the presence of other sources different than oil like organic matter from terrestrial biomass for %retene, and modern triterpenes for samples with high %terpenoids (T20, T26, T30, T35) (Table 1). Similarly, the ratios PI and parent/alkyl were also significantly higher in the category with low content of LMW compounds (∼4 and ∼2 times, respectively; P < 0.001; Figure 4), indicating pyrogenic sources or weathered oil. Because these samples matched with the DWH oil (Supplementary Figure 3), the high values in the PI and parent/alkyl ratios indicate the presence of burned oil residues rather than an increase in HMW PAHs due to loss of LMW PAHs during natural weathering processes (e.g., dissolution). The slightly higher values of the n-alkane biogenic ratio ([C15,17]/[C14,16,18]) in Figure 4 indicate the presence of phytoplankton, providing further evidence that oil residues (e.g., surface slicks) mixed with biogenic organic matter were transported from the surface to deeper water depths and deposited on deep-sea sediments.

Figure 4. Diagnostic ratios by categories of %LMW compounds (low, medium, and high) in contaminated sediments collected in 2010–2011 in the nGoM (surface sediment layer). DWH oil standard (NIST 2779) is shown as a dash line if values are within the range observed for the samples. Blue bars indicate values statistically different at P < 0.001. Data shown as mean ± 95% confidence interval.

In contrast, the naphthalene ratio ([N0 + N1]/T19) was significantly higher in the sediments containing medium content of LMW compounds relative to the other categories (∼2 times; P < 0.0001; Table 1 and Figure 4). In addition, CPI ratio < 1 was found as well in the medium category (Table 1 and Figure 4). Both ratios match the chemical signature of the subsurface plumes formed during the DWHOS, in which highly soluble and volatile molecules were abundant (e.g., log Kow: 3.37 for naphthalene, 3.87 for 1-methylnaphthalene), as well as short-chain n-alkanes without odd-to-even carbon preference (found in microorganisms and oil).

Furthermore, elevated LMW/HMW PAH and alkane ratios were observed in the category with a high content of LMW compounds relative to the other categories (∼2 and ∼4 times higher, respectively; P < 0.001; Figure 4). Similarly, ratios specific for labile n-alkane and hopanoids compounds (C12–C13/T19 and T32–T35/T19) were observed significantly higher in the category with a high content of LMW compounds (P < 0.001; Figure 4), indicating samples were exposed to minimum vertical transport in the water column before being deposited on the seafloor with low weathering effects. This is supported by a similar trend in the %decalins ratio, with decreasing values from the high to the low category (P < 0.001; Figure 4). Decalin is a bicyclic-saturated hydrocarbon analog to naphthalene with similar evaporative properties but insoluble in water (Table 1); therefore, a higher %decalins value indicates oil residues were not evaporated (did not reach surface waters) or dissolved in the submerged plumes but remain in suspension in the water column at depth before deposition on the seafloor.

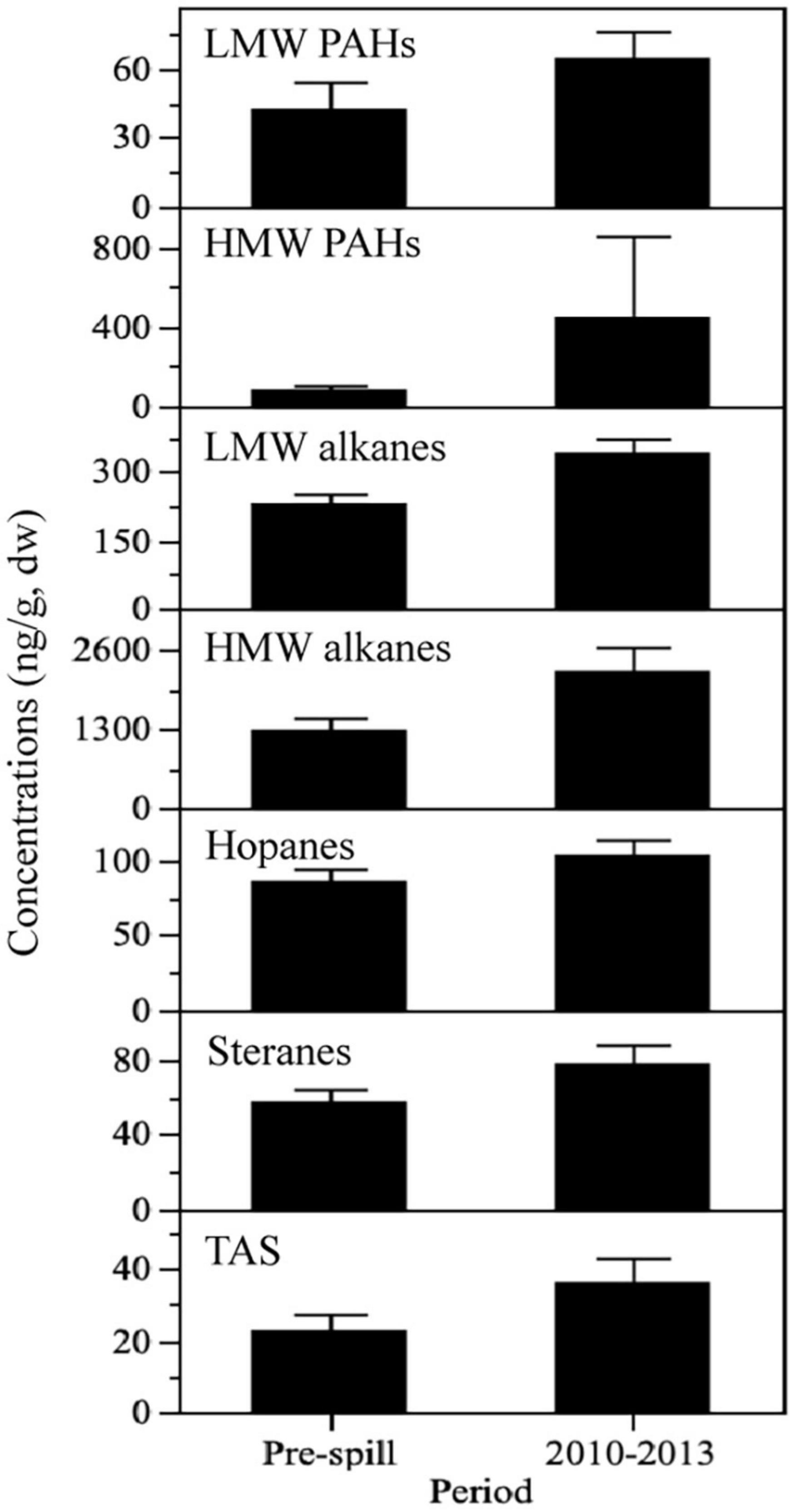

The buried sediment layer deposited post-spill (2010–2013) in the cores collected in 2018 showed significantly higher hydrocarbon concentrations (3.4 ± 0.7 μg/g) compared to the sediment layer deposited pre-spill (2.2 ± 0.6 μg/g) (p < 0.001). This was also observed for specific hydrocarbon compound groups (p < 0.001; Figure 5). As expected, the concentrations observed in the 2010–2013 buried sediment layer was at least an order of magnitude lower than the surface sediments collected in 2010–2011 (Figures 2, 5).

Figure 5. Hydrocarbon concentrations (ng/g, dw) by periods from contaminated sediment samples collected in 2018 in the nGoM. Post-pill denotes the buried sediment layer deposited in 2010–2013, and pre-spill indicate concentrations in downcore layers deposited before 2010. LMW PAHs: 2–3 rings, HMW PAHs: 4–6 rings, LMW alkanes: C12–C23 n-alkanes, HMW alkanes: C24–C37 n-alkanes, hopanes: C23–C35, steranes: C27–C29, and TAS: C20–C28. Data shown as mean ± 95% confidence interval.

Different from the surface layer collected in 2010–2011, distinct LMW alkanes categories were not observed, containing similar composition (7.9 ± 3.9%, 12.6 ± 2.2%, and 10.4%, respectively) and no odd-to-even carbon preference indicating oil (short- and long-chain alkanes) and microbial (short-chain alkanes) sources (Figure 6). Additionally, all categories showed that alkane and biomarker diagnostic ratios matched with oil from the DWHOS (Supplementary Figure 4). Moreover, biodegradation seems to affect only hopane compounds > C34 strongly, as shown by the ratio T32–T33/T19 with low values in the medium and high categories relative to the MC252 oil standard (Supplementary Figure 4). The ratio T30–T31/T19 in the low category of the buried layer is similar to the MC252 oil standard (Supplementary Figure 4) but higher than the 2010–2011 surface sediments (Supplementary Figure 3), indicating bacterial biomass inputs during weathering (Table 1). This is also observed for the %Terp ratio (Supplementary Figure 5). In addition, diagnostic alkane ratios for phytoplankton inputs were not significantly different among categories, and oil residues were highly weathered (Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 6. Relative abundance of PAHs and n-alkanes by categories of %LMW compounds: high (PAHs: 62.3%; alkanes: 10.4%), medium (PAHs: 32.9 ± 3.1%; alkanes: 12.6 ± 2.2%), and low (PAHs: 7.8 ± 4.4%; alkanes: 7.9 ± 3.9%). Contaminated sediment samples were collected in 2018 in the nGoM (buried sediment layer deposited in 2010–2013). Data shown as mean ± 95% confidence interval.

In contrast, we found that the data from the buried layer can be divided by categories of low, medium, and high content of LMW PAHs (7.8 ± 4.4%, 32.9 ± 3.1%, and 62.3%, respectively) (Figure 6), with similar relative amounts per category to the surface sediment layer collected in 2010–2011 (Figure 3). However, only 22% of the buried samples have low content of LMW PAH compounds, while 75% have medium, and only 3% (with only one sample) have a high content of LMW PAH. The composition of PAHs is very different among categories (Figure 6) and to the surface layer collected in 2011 (Figure 3). All categories in the 2010–2013 buried layer collected in 2018 have a higher content of parent compounds than observed in the surface sediments from 2011 (Figures 3, 6). The effects of weathering (e.g., degradation, transformation) years after burial can also be noted in the calculated PAH ratios (Supplementary Figure 5), with a different trend among categories in the buried layer (Supplementary Figure 5) compared to the surface sediments from 2011 (Figure 4). However, specifically for the category with low content of LMW compounds, PAH ratios were similar between the two datasets (buried layer collected in 2018 vs. surface sediments from 2010 to 2011).

The present work chemically characterized the MOSSFA event and, for the first time, identifies the water masses where the hydrocarbons originated (surface vs. depth) after partitioning into chemical mixtures during transport of the spilled oil from 1500 m depth to the surface of the water column. A combination of multiple molecular markers (i.e., PAHs, alkanes, hopanes) was used to calculate diagnostic ratios and identify biogenic, and oil-derived hydrocarbon sources deposited in deep-sea sediments from the MOSSFA event (Figure 4).

Our results support previous studies showing biogenic and oil-derived hydrocarbon inputs from surface waters during the DWHOS (Diercks et al., 2010; Passow et al., 2012; Brooks et al., 2015; Daly et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2016; Romero et al., 2017; White et al., 2019). Exopolymeric substances (EPS) are produced by phytoplankton and bacteria exposed to oil forming aggregates that sink rapidly (Passow et al., 2012; van Eenennaam et al., 2016) while preserving the chemical signature of the oil residues distinct from background signatures (Romero et al., 2015, 2017; Stout et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2016; van Eenennaam et al., 2018). Both sources from surface waters (biogenic and oil residues from the DWHOS) were noted on the sediment samples collected in 2010–2011 with low %LMW compounds, and elevated %Terp and alkanes ratios (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 3). Similarly, in previous studies, modern triterpenes and biogenic alkanes mixed with oil residues were observed in oil-contaminated surface waters (Stout and German, 2018; White et al., 2019) and deep-sea sediments (Romero et al., 2015; Stout et al., 2016). Also, hydrocarbons from terrestrial sources were present in the surface waters during the DWHOS (Murawski et al., 2016) that were deposited on benthic environments during the MOSSFA event as dominant siliciclastics sediment inputs (Brooks et al., 2015), supporting our observations of elevated %Re in the surface sediment layer from 2010 to 2011 (Figure 4).

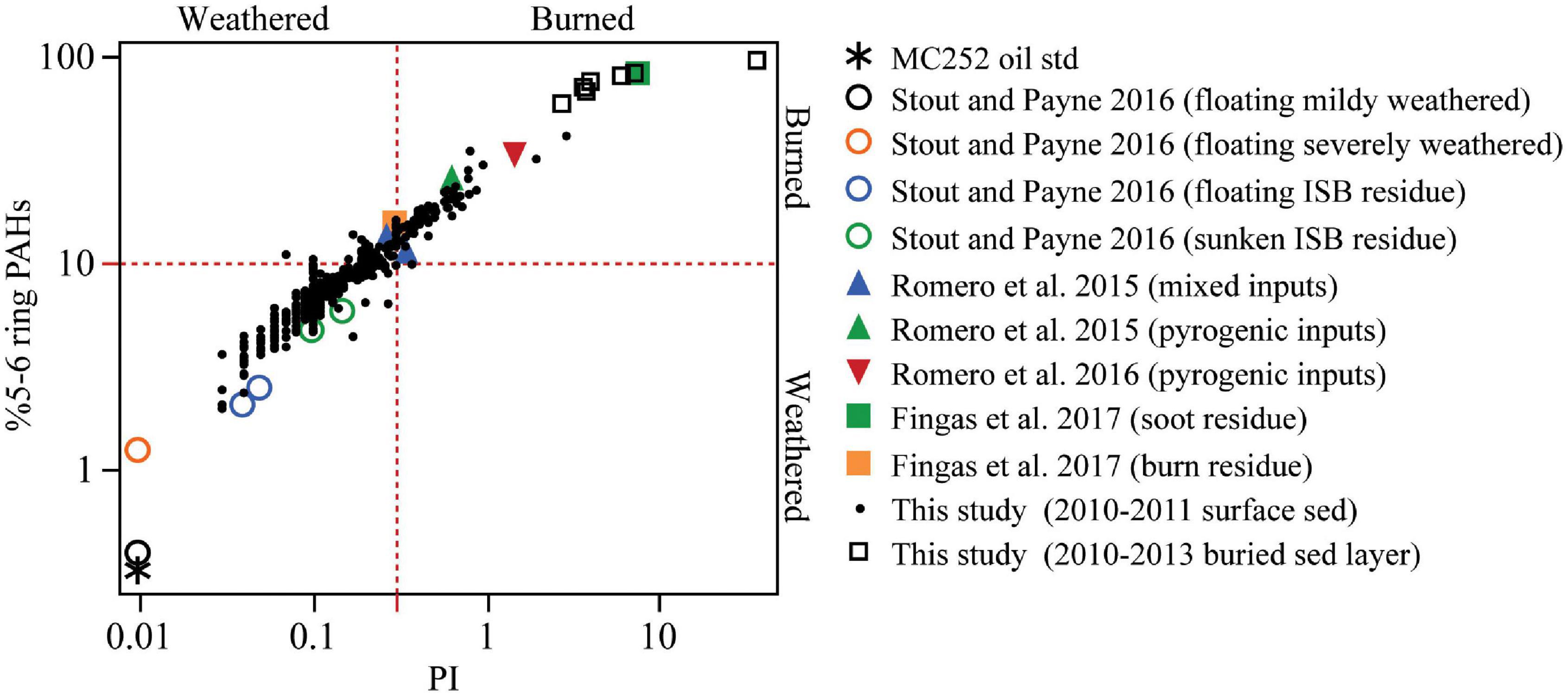

Our results also support previous studies showing burned-oil residue inputs from surface waters during the DWHOS (low category of %LMW; ratios: PI, parent/alkyl; Figure 4) using similar PAH ratios (Romero et al., 2015; Shigenaka et al., 2015) or estimating relative amounts of HMW PAHs (Stout and Payne, 2016b; Fingas, 2017). As a response effort during the DWHOS, about 220,000–310,000 barrels of floating oil were burned (Mabile and Allen, 2010), producing residues that were not mechanically recovered and believed to have sunk. Burn residues in deep-sea benthic environments have been mostly detected by an increase in HMW PAHs; however, HMW PAHs can also become abundant in oil residues due to loss of LMW PAHs during natural weathering processes. Therefore, we propose using biplots of ratios like PI and %5–6 ring PAHs (Figure 7) to distinguish burned-oil residues from weathered-oil residues. These ratios showed no correlation with indicator ratios of natural weathering processes for PAHs (e.g., dissolution, evaporation; Supplementary Figure 6). The PI ratio (e.g., Wang et al., 1999b, Wang et al., 2008; Romero et al., 2015; Shigenaka et al., 2015) as well as %5–6 ring PAHs (Shigenaka et al., 2015; Romero et al., 2016; Stout et al., 2016; Fingas, 2017) have been used to differentiate petrogenic and pyrogenic sources in surface and deep-sea samples. Using available data from previous studies and our study, Figure 7 shows the significant correlation between PI and %5–6 ring ratios (R = 0.68, P < 0.001, N = 416). The limits set for burned- and weathered-oil residues were based on previous studies (Wang et al., 2008; Romero et al., 2015). In Figure 7, the samples containing low %LMW compounds from 2010 to 2011 (indicative of MOSSFA derived from surface waters) have burned (17%), weathered (68%), and mixed (15%) oil residues. In contrast, the few samples containing low %LMW compounds in the buried sediments collected in 2018 (layer deposited in 2010–2013) have only burned-oil residues. Overall, the trend observed in Figure 7, supports well previous observations of deposited burned and mixed oil residues in the DeSoto Canyon after the DWHOS (Romero et al., 2015), burn residues after the explosion of the Hercules 265 gas rig (Romero et al., 2016), and oil residues after experimental burning of crude oil (Fingas, 2017). Interestingly, floating and sunken burned oil residue samples from Stout and Payne (2016b) have relatively low %5–6 ring PAHs and PI ratio (Figure 7). A potential explanation is that samples in Stout and Payne (2016b) were partially burned (∼89% burn efficiency), as shown by the presence of relatively high amounts of volatile compounds such as naphthalenes and other LMW PAHs. Also, the trend between burn efficiency and the PI ratio among studies supports the trend observed in Figure 7 (Shigenaka et al., 2015: ∼50% efficiency and PI = ∼0.1; Stout and Payne, 2016b: ∼89 efficiency and PI = 0.2; and Fingas, 2017: 99% efficiency and PI = 0.3–7.2). Moreover, Stout and Payne (2016b) found that burned oil residues can be detected by looking at the composition of aliphatics, in which n-alkanes > C20 are severely depleted, a pattern not explained by natural weathering processes (e.g., evaporation, biodegradation). In Figure 7, samples from our study located in the lower-left panel (weathered oil residues) did not have depleted n-alkanes > C20, indicating these samples were not burned but can be distinguished from samples that were partially burned, such as the samples in Stout and Payne (2016b).

Figure 7. Correlation between PAH ratios for samples analyzed in this study (low %LMW content in contaminated sediments collected in 2010–2011 and 2018) and from previous studies in the nGoM (R = 0.68, P < 0.001, N = 416). Both x-axis and y-axis shown in logarithmic scale (log base 10).

The trend observed in the data from the surface sediments collected in 2010–2011 also supports previous studies indicating MOSSFA was originated at depth during the DWHOS (e.g., Passow et al., 2012; Daly et al., 2016). Abundant deposition of LMW PAHs with low sedimentation at a depth of 1043 m was observed in the DeSoto Canyon after the DWHOS, attributed to the direct contact of the deep submerged plume with the continental slope surface sediments (Romero et al., 2015). In our study, the category with medium content of %LMW compounds has a chemical signature characteristic of the submerged plumes with elevated relative amounts of naphthalene compounds (Figure 4). In this category, 15% of the samples (N = 5) were not highly weathered (%Chrysene < 1.5), containing the highest relative amounts of naphthalene and LMW n-alkane compounds (Supplementary Figure 7). These samples were all located at depths higher than 1500 m (except for one sample at 1071 m; Supplementary Figure 7), out of the range for a direct contact of the deep plumes with the continental slope, which were observed between 900 and 1300 m (Ryerson et al., 2012). Therefore, these samples containing medium content of %LMW are evidence for MOSSFA originated at depth from the deep submerged plumes.

In contrast, the category with a high content of %LMW compounds indicates MOSSFA originated at depth in the water column, not from the submerged plumes but from contaminated sinking particles. The chemical signature of the samples with a high content of %LMW compounds (Figure 4) indicate MOSSFA was formed in the water column as predominant OMAS as observed previously in the water column (Joung and Shiller, 2013; Yan et al., 2016) and deep-sea sediments (Brooks et al., 2015; Romero et al., 2015; Stout and Payne, 2016a).

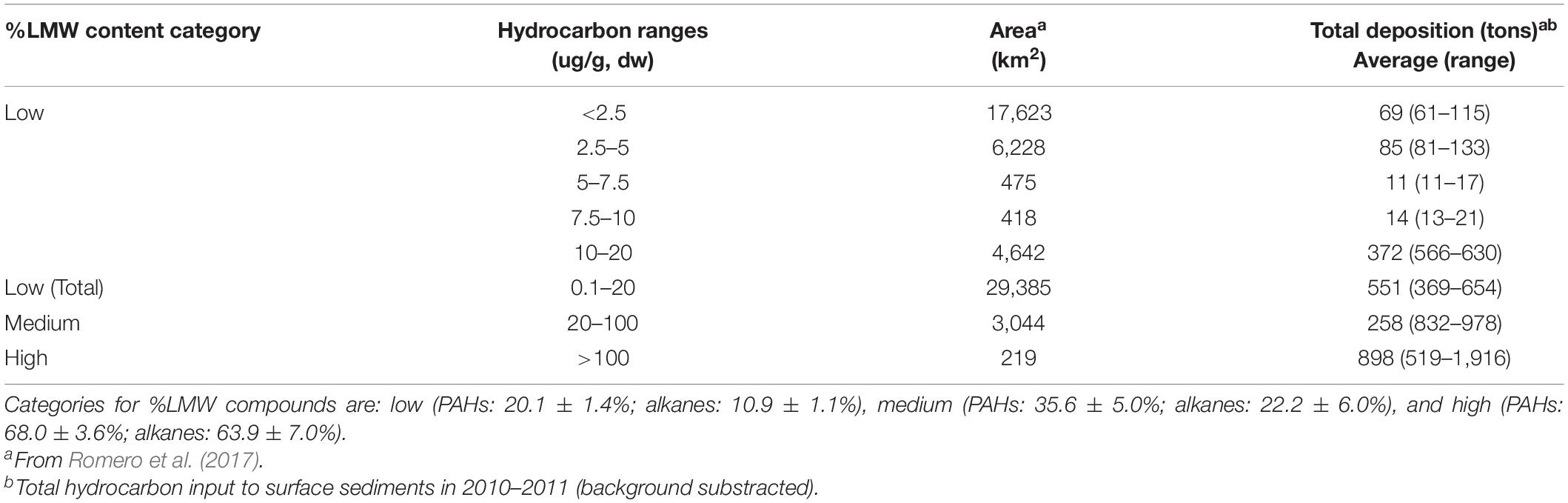

Altogether, using the spatial coverage of oil residues deposited after the DWHOS in deep-sea sediments by Romero et al. (2017), we found that MOSSFA from surface waters covered 90% of the deep-sea area studied and was responsible for 32% of the total deposition of oil residues observed offshore in deep-sea areas after the DWHOS (low category content of %LMW compounds; Table 2). In contrast, MOSSFA originated at depth from the submerged plumes covered only 9% of the deep-sea area studied and was responsible for 15% of the total deposition of oil residues observed after the DWHOS on deep-sea sediments (medium category content of %LMW compounds; Table 2). Furthermore, MOSSFA originated at depth but from the water column covered only 1% of the deep-sea area studied (mostly in close proximity of the DWH wellhead; Supplementary Figure 2) but was responsible for 53% of the total deposition of oil residues observed after the spill in this area (high category content of %LMW compounds; Table 2). This extensive deposition of oil-residues in the vicinity of the DWH wellhead may have been produced by the presence of larger amounts of sediment particles enhanced from the application of drilling mud to help control and stop the DWHOS (Graham et al., 2011) that mixed with the spilled oil and sank (Yan et al., 2016).

Table 2. Area coverage and total deposition of oil residues calculated in Romero et al. (2017) for each %LMW category and hydrocarbon range.

The buried samples collected 8 years after the DWHOS showed weathering after burial has affected most compounds (Supplementary Figure 5); therefore, the molecular markers used to identify where MOSSFA was originated in the water (ratios in Figure 4) cannot be applied in these sediment samples. In contrast, specific hopane and PAH ratios (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure 4) still indicate the presence of oil residues from the DWHOS and whether samples were affected or not by in situ burning of surface slicks. Also, biodegradation seems not to be the only weathering process affecting the buried oil residues, because Pr/C17 and Ph/C18 ratios were <1 (Figure 6). Transformation processes (e.g., oxidation) of oil-residues have been observed in samples collected from surface slicks or on beaches (Hall et al., 2013; White et al., 2016; Aeppli et al., 2018) and potentially also can be an important process at depth.

Overall, our analyses of multiple hydrocarbon compounds chemically characterized for the first time the MOSSFA event that formed during the DWHOS. We identified molecular markers of hydrocarbon sources (biogenic, DWHOS residues), natural and human-induced weathering processes (biodegradation, in situ oil burning), and hydrocarbon mixtures formed by the partitioning of oil residues in the water column. Altogether, our results provide the basis for identifying where MOSSFA originated in the water column and its fate in deep-sea benthic environments, important for response efforts in future deep oil spills. Significant findings include (1) natural weathering processes were dominant during the DWHOS, as evidenced by the chemical signature of MOSSFA at depth, which was similar to the chemical mixtures formed during the transport of oil residues to surface waters in the water column. (2) Biodegradation of buried oil residues in deep-sea sediments is slow; therefore, a longer impact to this environment is expected, as observed from deep-sea studies looking at hydrocarbons in sediments and benthic ecological recovery (Romero et al., 2017; Rohal et al., 2020). (3) Other weathering processes different from biodegradation might occur (e.g., oxidation) in buried oil residues in deep-sea environments that still need to be studied to predict the long-term fate of oil residues from deep spills.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: Data are publicly available through the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative & Data Cooperative (GRIIDC) at https://data.gulfresearchinitiative.org (doi: 10.7266/N7ZG6Q71, doi: 10.7266/N7N29V16, doi: 10.7266/n7-6bfd-g305, doi: 10.7266/n7-h6gj-1m18). Publicly data from ERMA-NRDA program are available at the DIVER database (https://www.diver.orr.noaa.gov/).

IR carried out the laboratory and data analyses and wrote the manuscript including figures and tables. GB, RL, and PS established the chronology of cores collected in 2018. JC and AD selected sampled sites and help in the collection. SB and AH helped in collection and discussions. All co-authors contributed to the manuscript by revising, editing, and adding references and comments. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was made possible by a grant from The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GOMRI): REDIRECT (Resuspension, Redistribution and Deposition of Deepwater Horizon recalcitrant hydrocarbons to offshore depocenter). Also, research reported in this publication was supported by an Early-Career Research Fellowship from the Gulf Research Program of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to IC Romero (Grant #2000010685). The content in this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Gulf Research Program of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the crew of the R/V Point Sur and R/V Weatherbird II for their help during the field program, and the technicians Hannah Hamontree, and Olivia Traenkle for laboratory support.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.637970/full#supplementary-material

Abrajano, T. A., and Yan, B. (2003). “High molecular weight petrogenic and pyrogenic hydrocarbons in aquatic environments,” in Treatise on Geochemistry Vol. Environmental Geochemistry, ed. B. S. Lollar (Pergamon: Elsevier), 475–510.

Adhikari, P. L., Maiti, K., Bosu, S., and Jones, P. R. (2016). 234Th as a tracer of vertical transport of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 107, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.04.002

Adhikari, P. L., Maiti, K., and Overton, E. B. (2015). Vertical fluxes of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Chem. 168, 60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2014.11.001

Adhikari, P. L., Wong, R. L., and Overton, E. B. (2017). Application of enhanced gas chromatography/triple quadrupole mass spectrometry for monitoring petroleum weathering and forensic source fingerprinting in samples impacted by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Chemosphere 184, 939–950. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.06.077

Aeppli, C., Nelson, R. K., Radović, J. R., Carmichael, C. A., Valentine, D. L., and Reddy, C. M. (2014). Recalcitrance and degradation of petroleum biomarkers upon abiotic and biotic natural weathering of Deepwater Horizon oil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 6726–6734. doi: 10.1021/es500825q

Aeppli, C., Swarthout, R. F., O’Neil, G. W., Katz, S. D., Nabi, D., Ward, C. P., et al. (2018). How Persistent and bioavailable are oxygenated deepwater horizon oil transformation products? Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 7250–7258. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b01001

Ainsworth, C. H., Paris, C. B., Perlin, N., Dornberger, L. N., Patterson, W. F., Chancellor, E., et al. (2018). Impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill evaluated using an end-to-end ecosystem model. PLoS One 13:e190840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190840

Appleby, P. G., and Oldfield, F. (1983). The assessment of 210 Pb data from sites with varying sediment accumulation rates. Hydrobiologia 103, 29–35.

Baguley, J. G., Montagna, P. A., Cooksey, C., Hyland, J. L., Bang, H. W., Morrison, C., et al. (2015). Community response of deep-sea soft-sediment metazoan meiofauna to the Deepwater Horizon blowout and oil spill. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 528, 127–140. doi: 10.3354/meps11290

Baskaran, M., Nix, J., Kuyper, C., and Karunakara, N. (2014). Problems with the dating of sediment core using excess 210 Pb in a freshwater system impacted by large scale watershed changes. J. Environ. Radioact. 138, 355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2014.07.006

Bianchi, T. S., Cui, X., Blair, N. E., Burdige, D. J., and Eglinton, T. I. (2018). Organic Geochemistry Centers of organic carbon burial and oxidation at the land-ocean interface. Org. Geochem. 115, 138–155. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.09.008

Binford, M. W. (1990). Calculation and uncertainty analysis of 210Pb dates for PIRLA project lake sediment cores. J. Paleolimnol. 3, 253–267.

Boehm, P. D., and Flest, D. L. (1982). Subsurface distributions of petroleum from an offshore well blowout. The Ixtoc I Blowout, Bay of Campeche. Environ. Sci. Technol. 16, 67–74. doi: 10.1021/es00096a003

Bosman, S. H., Schwing, P. T., Larson, R. A., Wildermann, E., Brooks, G. R., Romero, I. C., et al. (2020). The southern Gulf of Mexico: a baseline radiocarbon isoscape of surface sediments and isotopic excursions at depth. PLoS One 15:e0231678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231678

Bray, E. E., and Evans, E. D. (1961). Distribution of n-paraffins as a clue to recognition of source beds. Geochemica Cosmochim. 22, 2–15.

Brooks, G. R., Larson, R. A., Schwing, P. T., Romero, I., Moore, C., Reichart, G.-J., et al. (2015). Sedimentation pulse in the NE Gulf of Mexico following the 2010 DWH blowout. PLoS One 10:e0132341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132341

Canuel, E. A., and Hardison, A. K. (2016). Sources, ages, and alteration of organic matter in estuaries. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 8, 409–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-122414-034058

Chanton, J., Zhao, T., Rosenheim, B. E., Joye, S., Bosman, S., Brunner, C., et al. (2015). Using natural abundance radiocarbon to trace the flux of petrocarbon to the seafloor following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 847–854. doi: 10.1021/es5046524

Chanton, J. P., Giering, S. L. C., Bosman, S. H., Rogers, K. L., Sweet, J., Asper, V. L., et al. (2018). Isotopic composition of sinking particles: oil effects, recovery and baselines in the Gulf of Mexico, 2010-2015. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 6, 2010–2015. doi: 10.1525/elementa.298

Daly, K., Gilbert, S., Hollander, D. J., Paris, C. B., and Schlüter, M. (2020). “Physical processes influencing the sedimentation and lateral transport of MOSSFA in the NE Gulf of Mexico,” in Scenarios and Responses to Future Deep Oil Spills Fighting the Next War, eds S. Murawski, C. H. Ainsworth, S. Gilbert, D. J. Hollander, C. B. Paris, M. Schluter, et al. (Cham: Springer), 300–314. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-12963-7_18

Daly, K. L., Passow, U., Chanton, J., and Hollander, D. (2016). Assessing the impacts of oil-associated marine snow formation and sedimentation during and after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Biochem. Pharmacol. 13, 18–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ancene.2016.01.006

Dembicki, H. (2010). Recognizing and compensating for interference from the sediment’s background organic matter and biodegradation during interpretation of biomarker data from sea fl oor hydrocarbon seeps: an example from the Marco Polo area seeps. Gulf Mar. Pet. Geol. 27, 1936–1951. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2010.06.009

Diercks, A.-R., Highsmith, R. C., Asper, V. L., Joung, D., Zhou, Z., Guo, L., et al. (2010). Characterization of subsurface polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons at the Deepwater Horizon site. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, 1–6. doi: 10.1029/2010GL045046

Diercks, A., Romero, I. R., Schwing, P., Larson, R. A., Harris, A., Bosman, S., et al. (2021). Resuspension, Redistribution and Deposition of DwH oil-residues to offshore Depocenters. Front. Mar. Sci. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.630183

D’souza, N. A., Subramaniam, A., Juhl, A. R., Hafez, M., Chekalyuk, A., Phan, S., et al. (2016). Elevated surface chlorophyll associated with natural oil seeps in the Gulf of Mexico. Nat. Geosci. 9, 215–218. doi: 10.1038/NGEO2631

Du, M., and Kessler, J. D. (2012). Assessment of the spatial and temporal variability of bulk hydrocarbon respiration following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 10499–10507. doi: 10.1021/es301363k

Elordui-zapatarietxe, S., Rosell-melé, A., Moraleda, N., Tolosa, I., and Albaigés, J. (2010). Phase distribution of hydrocarbons in the water column after a pelagic deep ocean oil spill. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 60, 1667–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.07.001

Fingas, M. (2017). The fate of PAHs resulting from in-situ oil burns. Intern. Oil Spill Conf. Proc. 2017, 1041–1056.

Gonzalez, J. J., Vinas, L., Franco, M. A., Fumega, J., Soriano, J. A., Grueiro, G., et al. (2006). Spatial and temporal distribution of dissolved / dispersed aromatic hydrocarbons in seawater in the area affected by the Prestige oil spill. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 53, 250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.09.039

Graham, B., Keilly, W. K., Beinecke, F., Boesch, D., Garcia, T. D., Murray, C. A., et al. (2011). Deep water: The Gulf Oil Disaster and the Future of Offshore Drilling; Report to the President. Washington, DC: National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Offshore Drilling.

Hall, G. J., Frysinger, G. S., Aeppli, C., Carmichael, C. A., Gros, J., Lemkau, K. L., et al. (2013). Oxygenated weathering products of Deepwater Horizon oil come from surprising precursors. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 75, 140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.07.048

Harvey, G. R., Requejo, A. G., McGillivary, P. A., and Tokar, J. M. (1979). Observation of a subsurface oil-rich layer in the open ocean. Science 205, 999–1001.

Herrera-Herrera, A. V., Leierer, L., Jambrina-enríquez, M., Connolly, R., and Mallol, C. (2020). Organic geochemistry evaluating different methods for calculating the Carbon Preference Index (CPI): implications for palaeoecological and archaeological research. Org. Geochem. 146:104056. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2020.104056

Hood, K. C., Wenger, L. M., Gross, O. P., and Harrison, S. C. (2002). Hydrocarbon systems analysis of the northern Gulf of Mexico: delineation of hydrocarbon migration pathways using seeps and seismic imaging. Surf. Explor. Case Hist. Appl. Geochem. 48, 25–40.

Hu, C., Weisberg, R. H., Liu, Y., Zheng, L., Daly, K. L., English, D. C., et al. (2011). Did the northeastern Gulf of Mexico become greener after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill? Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, 1–5. doi: 10.1029/2011GL047184

Johansen, Ø, Rye, H., and Cooper, C. (2003). DeepSpill – field study of a simulated oil and gas blowout in deep water. Spill Sci. Technol. Bull. 8, 433–443. doi: 10.1016/S1353-2561(02)00123-8

Joung, D., and Shiller, A. M. (2013). Trace element distributions in the water column near the Deepwater Horizon well blowout. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 2161–2168. doi: 10.1021/es303167p

Joye, S. B., Macdonald, I. R., Leifer, I., and Asper, V. (2011). Magnitude and oxidation potential of hydrocarbon gases released from the BP oil well blowout. Nat. Geosci. 4, 2–6. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1067

Kameyama, S., Tsunogai, U., Nakagawa, F., Sasakawa, M., Komatsu, D. D., Ijiri, A., et al. (2009). Enrichment of alkanes within a phytoplankton bloom during an in situ iron enrichment experiment in the western subarctic Paci fi c. Mar. Chem. 115, 92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2009.06.009

Larowe, D. E., Arndt, S., Bradley, J. A., Burwicz, E., Dale, A. W., and Amend, J. P. (2020). ScienceDirect Organic carbon and microbial activity in marine sediments on a global scale throughout the Quaternary. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 286, 227–247. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2020.07.017

Larson, R. A., Brooks, G. R., Schwing, P. T., Holmes, C. W., Carter, S. R., and Hollander, D. J. (2018). Anthropocene High-resolution investigation of event driven sedimentation: Northeastern Gulf of Mexico. Biochem. Pharmacol. 24, 40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ancene.2018.11.002

Lea-smith, D. J., Biller, S. J., Davey, M. P., Cotton, C. A. R., Perez, B. M., Turchyn, A. V., et al. (2015). Contribution of cyanobacterial alkane production to the ocean hydrocarbon cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 13591–13596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507274112

Lindo-Atichati, D., Paris, C. B., Le Hénaff, M., Schedler, M., Valladares Juárez, A. G., and Müller, R. (2014). Simulating the effects of droplet size, high-pressure biodegradation, and variable flow rate on the subsea evolution of deep plumes from the Macondo blowout. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 129, 301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2014.01.011

Liu, Z., Liu, J., Zhu, Q., and Wu, W. (2012). The weathering of oil after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill: insights from the chemical composition of the oil from the sea surface, salt marshes and sediments. Environ. Res. Lett. 7:035302. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/7/3/035302

Mabile, N., and Allen, A. (2010). Controlled Burns after Action Report Burns on May 28th - August 3 2010. Houma: Controlled Burn Group, Houma Incident Command Post.

MacDonald, I. R., Garcia-Pineda, O., Beet, A., Daneshgar, A., Feng, L., Graettinger, G., et al. (2015). Natural and unnatural oil slicks in the Gulf of Mexico. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 120, 8364–8380.

Middleditch, B. S., Chang, E. S., and Basile, B. (1979). Alkanes in plankton from the buccaneer oilfield. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 427, 421–427.

Montagna, P. A., Baguley, J. G., Cooksey, C., Hartwell, I., Hyde, L. J., Hyland, J. L., et al. (2013). Deep-sea benthic footprint of the deepwater horizon blowout. PLoS One 8:e70540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070540

Mulabagal, V., Yin, F., John, G. F., Hayworth, J. S., and Clement, T. P. (2013). Chemical fingerprinting of petroleum biomarkers in Deepwater Horizon oil spill samples collected from Alabama shoreline. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 70, 147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.02.026

Murawski, S. A., Fleeger, J. W., Patterson, W. F., Hu, C., Daly, K., Romero, I., et al. (2016). How did the Deepwater Horizon oil spill affect coastal and continental shelf ecosystems of the Gulf of Mexico? Oceanography 29, 160–173. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2016.80

Murawski, S. A., Hogarth, W. T., Peebles, E. B., and Barbeiri, L. (2014). Prevalence of external skin lesions and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon concentrations in Gulf of Mexico fishes, post-Deepwater Horizon. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 143, 37–41. doi: 10.1080/00028487.2014.911205

Niu, H., Li, Z., Lee, K., Kepkay, P., and Mullin, J. V. (2010). Modelling the transport of oil-mineral-aggregates (OMAs) in the marine environment and assessment of their potential risks. Environ. Model. Assess. 16, 61–75. doi: 10.1007/s10666-010-9228-0

NOAA (2011). Analytical quality assurance plan, Mississippi Canyon 252 (Deepwater Horizon) natural resource damage assessment, Version 4.0. May 30, 2014.

Passow, U., Ziervogel, K., Asper, V., and Diercks, A. (2012). Marine snow formation in the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Environ. Res. Lett. 7:035301. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/7/3/035301

Pulster, E. L., Gracia, A., Armenteros, M., Carr, B. E., Mrowicki, J., and Murawski, S. A. (2020). Chronic PAH exposures and associated declines in fish health indices observed for ten grouper species in the Gulf of Mexico. Sci. Total Environ. 703:135551. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135551

Quigg, A., Passow, U., Daly, K. L., Burd, A., Hollander, D. J., Schwing, P. T., et al. (2020). “Marine oil snow sedimentation and flocculent accumulation (MOSSFA) events: learning from the past to predict the future,” in Deep Oil Spills: Facts, Fate, and Effects, eds S. A. Murawski, C. H. Ainsworth, S. Gilbert, D. J. Hollander, C. B. Paris, M. Schlüter, et al. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 196–220. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-11605-7_12

Quintana-Rizzo, E., Torres, J. J., Ross, S. W., Romero, I., Watson, K., Goddard, E., et al. (2015). δ13C and δ15N in deep-living fishes and shrimps after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Gulf Mexico Mar. Pollut. Bull. 94, 241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.02.002

Rohal, M., Barrera, N., Escobar-briones, E., Brooks, G., Hollander, D., Larson, R., et al. (2020). How quickly will the o ff shore ecosystem recover from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill? Lessons learned from the 1979 Ixtoc-1 oil well blowout. Ecol. Indic. 117:106593. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106593

Romero, I. C., Judkins, H., and Vecchione, M. (2020). Temporal variability of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in deep-sea cephalopods of the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:54. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00054

Romero, I. C., Özgökmen, T., Snyder, S., Schwing, P., O’Malley, B. J., Beron-Vera, F. J., et al. (2016). Tracking the Hercules 265 marine gas well blowout in the Gulf of Mexico. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean 121, 706–724. doi: 10.1002/2015JC011037

Romero, I. C., Schwing, P. T., Brooks, G. R., Larson, R. A., Hastings, D. W., Flower, B. P., et al. (2015). Hydrocarbons in deep-sea sediments following the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Blowout in the Northeast Gulf of Mexico. PLoS One 10:e0128371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128371

Romero, I. C., Sutton, T., Carr, B., Quintana-Rizzo, E., Ross, S. W., Hollander, D. J., et al. (2018). A decadal assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mesopelagic fishes from the Gulf of Mexico reveals exposure to oil-derived sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 10985–10996. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02243

Romero, I. C., Toro-farmer, G., Diercks, A., Schwing, P., Muller-Karger, F., Murawski, S., et al. (2017). Large-scale deposition of weathered oil in the Gulf of Mexico following a deep-water oil spill. Environ. Pollut. 228, 179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.05.019

Ryerson, T. B., Camilli, R., Kessler, J. D., Kujawinski, E. B., Reddy, C. M., Valentine, D. L., et al. (2012). Chemical data quantify Deepwater Horizon hydrocarbon flow rate and environmental distribution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 20246–20253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110564109

Schwing, P. T., Chanton, J. P., Romero, I. C., Hollander, D. J., Goddard, E. A., Brooks, G. R., et al. (2018). Tracing the incorporation of carbon into benthic foraminiferal calcite following the Deepwater Horizon event. Environ. Pollut. 237, 424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.02.066

Schwing, P. T., O’Malley, B. J., Romero, I. C., Martínez-Colón, M., Hastings, D. W., Glabach, M. A., et al. (2017). Characterizing the variability of benthic foraminifera in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico following the Deepwater Horizon event (2010-2012). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 2754–2769. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7996-z

Schwing, P. T., Romero, I. C., Brooks, G. R., Hastings, D. W., Larson, R. A., and Hollander, D. J. (2015). Correction: a decline in benthic foraminifera following the deepwater horizon event in the Northeastern Gulf of Mexico. PLoS One 10:e0128505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128505

Schwing, P. T., Romero, I. C., Larson, R. A., O’malley, B. J., Fridrik, E. E., Goddard, E. A., et al. (2016). Sediment core extrusion method at millimeter resolution using a calibrated, threaded-rod. J. Vis. Exp. 2016:e54363. doi: 10.3791/54363

Shigenaka, G., Erd, N., Overton, E., Meyer, B., Gao, H., and Miles, S. (2015). Comparison of Physical and Chemical Characteristics of in-Situ Burn Residue and Other Environmental Oil Samples Collected During the Deepwater Horizon Spill Response. New Orleans, LA: Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE).

Simoneit, B. R. T., Grimalt, J. O., Wang, T. G., Cox, R. E., Hatcher, P. G., and Nissenbaum, A. (1985). Cyclic terpenoids of contemporary resinous plant detritus and of fossil woods, ambers and coals. Adv. Org. Geochem. 10, 877–889.

Simoneit, B. R. T., Oros, D. R., Karwowski, Ł, Szendera, Ł, Smolarek-lach, J., Goryl, M., et al. (2020). Terpenoid biomarkers of ambers from Miocene tropical paleoenvironments in Borneo and of their potential extant plant sources. Int. J. Coal Geol. 221:103430. doi: 10.1016/j.coal.2020.103430

Socolofsky, S. A., Adams, E. E., and Sherwood, C. R. (2011). Formation dynamics of subsurface hydrocarbon intrusions following the Deepwater Horizon blowout. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, 1–6. doi: 10.1029/2011GL047174

Sørensen, L., Meier, S., and Mjøs, S. A. (2016). Application of gas chromatography / tandem mass spectrometry to determine a wide range of petrogenic alkylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in biotic samples. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 30, 2052–2058. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7688

Stout, S. A., and German, C. R. (2018). Characterization and flux of marine oil snow settling toward the sea floor in the northern Gulf of Mexico during the Deepwater Horizon incident: evidence for input from surface oil and impact on shallow shelf sediments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 129, 695–713. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.10.059

Stout, S. A., and Payne, J. R. (2016a). Chemical composition of floating and sunken in-situ burn residues from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 108, 186–202. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.04.031

Stout, S. A., and Payne, J. R. (2016b). Macondo oil in deep-sea sediments: part 1 - sub-sea weathering of oil deposited on the seafloor. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 111, 365–380. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.07.036

Stout, S. A., Payne, J. R., Ricker, R. W., Baker, G., and Lewis, C. (2016). Macondo oil in deep-sea sediments: part 2 — Distribution and distinction from background and natural oil seeps. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 111, 381–401. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.07.041

Sutton, T. T., Frank, T., Judkins, H., and Romero, I. C. (2020). “As gulf oil extraction goes deeper, who is at risk? community structure, distribution, and connectivity of the deep-pelagic fauna,” in Scenarios and Responses to Future Deep Oil Spills, eds S. Murawski, C. H. Ainsworth, S. Gilbert, D. J. Hollander, C. B. Paris, M. Schluter, et al. (Cham: Springer), 403–418. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-12963-7_24

Swarzenski, P. W. (2014). “210Pb dating,” in Encyclopedia of Scientific Dating Methods, eds W. J. Rink and J. Thompson (Cham: Springer), 1–11. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6326-5

Valentine, D. L., Kessler, J. D., Redmond, M. C., Mendes, S. D., Heintz, M. B., Farwell, C., et al. (2010). Propane respiration jump-starts microbial response to a deep oil spill. Science 330, 208–211. doi: 10.1126/science.1196830

van Eenennaam, J. S., Rahsepar, S., Radović, J. R., Oldenburg, T. B. P., Wonink, J., Langenhoff, A. A. M., et al. (2018). Marine snow increases the adverse effects of oil on benthic invertebrates. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 126, 339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.11.028

van Eenennaam, J. S., Wei, J., Bao, P., Foekema, E. M., and Murk, A. J. (2016). Oil spill dispersants induce formation of marine snow by algae-associated bacteria. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 104, 294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.01.005

Vonk, S. M., Hollander, D. J., and Murk, A. J. (2015). Was the extreme and wide-spread marine oil-snow sedimentation and flocculent accumulation (MOSSFA) event during the Deepwater Horizon blowout unique? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 100, 5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.08.023

Walker, B. D., Druffel, E. R. M., Kolasinski, J., Roberts, B. J., Xu, X., and Rosenheim, B. E. (2017). Stable and radiocarbon isotopic composition of dissolved organic matter in the Gulf of Mexico. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 8424–8434. doi: 10.1002/2017GL074155

Wang, Z., Fingas, M., and Page, D. S. (1999a). Oil spill identification. J. Chromatogr. A 843, 369–411.

Wang, Z., Fingas, M. F., Landriault, M., Sigouin, L., Lambert, P., Turpin, R., et al. (1999b). PAH distribution in the 1994 and 1997 mobile burn products and determination of the diesel PAH destruction efficiencies. Int. Oil Spill Conf. Proc. 1999, 1287–1292. doi: 10.7901/2169-3358-1999-1-1287

Wang, Z., and Fingas, M. F. (2003). Development of oil hydrocarbon fingerprinting and identification techniques. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 47, 423–452. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(03)00215-7

Wang, Z., Yang, C., Brown, C., Hollebone, B., and Landriault, M. (2008). A case study: distinguishing Pyrogenic hydrocarbons froM Petrogenic hydrocarbons. Intern. Oil Spill Conf. 2008, 311–320.

Wang, Z., Yang, C., Yang, Z., Brown, C. E., Hollebone, B. P., and Stout, S. A. (2016). “Petroleum biomarker fingerprinting for oil spill characterization and source identification,” in Standard Handbook Oil Spill Environmental Forensics, eds Z. Stout and S. Wang (Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc), 131–254. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-803832-1/00004-0

White, H. K., Marx, C. T., Valentine, D. L., Sharpless, C., Aeppli, C., Gosselin, K. M., et al. (2019). Examining inputs of biogenic and oil-derived hydrocarbons in surface waters following the deepwater horizon oil spill. ACS Earth Sp. Chem. 3, 1329–1337. doi: 10.1021/acsearthspacechem.9b00090

White, H. K., Wang, C. H., Williams, P. L., Findley, D. M., Thurston, A. M., Simister, R. L., et al. (2016). Long-term weathering and continued oxidation of oil residues from the Deepwater Horizon spill. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 113, 380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.10.029

Xing, L., Zhang, H., Yuan, Z., Sun, Y., and Zhao, M. (2011). Terrestrial and marine biomarker estimates of organic matter sources and distributions in surface sediments from the East China Sea shelf. Cont. Shelf Res. 31, 1106–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2011.04.003

Yan, B., Passow, U., Chanton, J. P., Nöthig, E.-M., Asper, V., Sweet, J., et al. (2016). Sustained deposition of contaminants from the Deepwater Horizon spill. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E3332–E3340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513156113

Ziervogel, K., McKay, L., Rhodes, B., Osburn, C. L., Dickson-Brown, J., Arnosti, C., et al. (2012). Microbial activities and dissolved organic matter dynamics in oil-contaminated surface seawater from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill site. PLoS One 7:e34816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034816

Keywords: hydrocarbons, deep-sea sediment, oil spill accidents, MOSSFA, marine oil snow (MOS)

Citation: Romero IC, Chanton JP, Brooks GR, Bosman S, Larson RA, Harris A, Schwing P and Diercks A (2021) Molecular Markers of Biogenic and Oil-Derived Hydrocarbons in Deep-Sea Sediments Following the Deepwater Horizon Spill. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:637970. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.637970

Received: 04 December 2020; Accepted: 28 April 2021;

Published: 06 July 2021.

Edited by:

Robert Hetland, Texas A&M University, United StatesReviewed by:

Shawn Doyle, Texas A&M University, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Romero, Chanton, Brooks, Bosman, Larson, Harris, Schwing and Diercks. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Isabel C. Romero, aXNhYmVscm9tZXJvQHVzZi5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.