- 1School of Environment, Resources and Sustainability, Faculty of Environment, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

- 2Ocean Frontier Institute, Department of Geography, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, NL, Canada

- 3School of Environment, Enterprise & Development, Faculty of Environment, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

This research is a critical examination of the behavioral foundations of livelihood pathways over a 50-year time period in a multispecies fishery in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Fishers make difficult decisions to pursue, enjoy, and protect their livelihoods in times of change and uncertainty, and the resultant behaviors shape efforts to advance sustainability through coastal and marine fisheries governance. However, there is limited evidence about fishers’ behavioral changes over long time periods, and the psychosocial experiences that underpin them, beyond what is assumed using neoclassical economic and rational choice framings. Our analysis draws on 26 narrative interviews with fishers who have pursued two or more fish species currently or formerly. Fishers were asked about their behavioral responses to change and uncertainty in coastal fisheries across their entire lifetimes. Their narratives highlighted emotional, perceptual, and values-oriented factors that shaped how fishers coped and adapted to change and uncertainty. The contributions to theory and practice are two-fold. First, findings included variation in patterns of fisher behaviors. Those patterns reflected fishers prioritizing and trading-off material or relational well-being. With policy relevance, prioritizations and trade-offs of forms of well-being led to unexpected outcomes for shifting capacity and capitalization for fishers and in fisheries more broadly. Second, findings identified the influence of emotions as forms of subjective well-being. Further, emotions and perceptions functioned as explanatory factors that shaped well-being priorities and trade-offs, and ultimately, behavioral change. Research findings emphasize the need for scientists, policy-makers, and managers to incorporate psychosocial evidence along with social science about fisher behavior into their models, policy processes, and management approaches. Doing so is likely to support efforts to anticipate impacts from behavioral change on capacity and capitalization in fleets and fisheries, and ultimately, lead to improved governance outcomes.

Introduction

Fisheries policy implementation involves anticipating and steering – through models and planning – the benefits and burdens of trade-off and decisions associated with social-ecological change (Blythe et al., 2020). The outcomes of these policy choices, moreover, are linked to international commitments and national objectives aimed at addressing drivers of change related to climate, economic development, and biodiversity loss (Chuenpagdee and Jentoft, 2018; Stephenson et al., 2019; Lam et al., 2020). To improve capacities and outcomes in fisheries and marine governance, new knowledge is needed about how fishers express behavior in response to change and uncertainty in marine environments, coastal communities, and in the context of policy development and implementation (Neilsen et al., 2017; Armitage et al., 2019; Andrews et al., 2020).

In this article, the term ‘fisher behavior’ refers to fishers’ actions both as individuals and as groups reflecting the mental processing and social exchange of information in coastal fisheries through decision-making (see Lynn et al., 2015). Decision-making represents the negotiation of values, emotions, perceptions, and various contextual factors that shape the individual and group capacities to choose and their desires to move to action (Ellis, 2000; Chuenpagdee and Jentoft, 2009). When fishers act in response to policies, the subsequent behaviors reflect policy outcomes that, in turn, provide insight into opportunities to strengthen marine governance (Pitcher and Chuenpagdee, 1993; Salas and Gaertner, 2004). Lessons from understanding and explaining fisher behavior in a local context are critical because, as Fulton et al. (2011): (3) argue in their review, “a consistent outcome [of policy implementation] is that resource users behave in a manner that is often unintended by the designers of the management system.” In short, to anticipate fisheries policy outcomes, scientists and decision-makers need to better understand fisher behavior.

Recent research has advanced a typology of fisher behaviors reflecting a range of tactical and strategic actions (Andrews et al., 2020). Tactical behaviors include actions in marine environments and landing areas such as effort, discarding, and compliance with landing and reporting obligations. Tactical behaviors shape pressures on fish stocks, and provide insights into whether fishers are following rules (Van Putten et al., 2012; Bergseth et al., 2015). Strategic behaviors include actions in coastal communities such as entering and exiting fisheries, investing in or divesting gear or vessels, diversifying household incomes, engaging in individual or collective political action, and out-migration from communities. Strategic behaviors alter the financial and human capital and capacity in fisheries shaped by individuals and group responses in coastal communities to global and local drivers of change (Van Putten et al., 2013; Lade et al., 2015; Van Dijk et al., 2017). Impacts on fish stocks and ecosystems, along with the capacity and capitalization of fishing fleets and in fisheries require differential policy responses. These might include integration of different policy tools, including input and output controls, temporary or permanent closures, or incentives (Lubchenco et al., 2016; Ojea et al., 2017).

To date, two key opportunities exist to improve the evidence base on fisher behavior. First, we need assessments of how fishers express diverse behaviors over long time periods relative to environmental, social, and policy changes and uncertainty. Research about fisher behavior has tended toward empirical studies of fishers behavior with shorter temporal scopes (e.g., <6 years), and these studies are most often about tactical behavior (Andrews et al., 2020). For example, some researchers have examined effort or compliance behavior in years before and after the implementation of a marine protected area (Abbott and Haynie, 2012; Arias et al., 2015). Strategic behavioral research has explored strategies behaviors through methods such as questionnaires on why fish harvesters “stay in or exit” the fishery (Pascoe et al., 2015), or through modeling when and why fish harvesters might invest under different policy interventions (Van Dijk et al., 2017). This kind of research provides useful snapshots into fisher behavioral responses to policies. Yet, the research has limited traction in assessing significant change processes in fisheries such as collapse, restructuring, and rebuilding to which fisher behavior contributes (Beitl, 2014; Khan and Chuenpagdee, 2014; Bieg et al., 2017).

Second, more psychosocial evidence is required to explain behavioral responses to policy changes. Researchers have revealed that psychosocial variables are likely a crucial aspect of understanding the environmental, social, economic, and policy changes that shape behavior, as psychosocial factors are involved in the mental and social decision-making that is fundamental to fishers’ negotiation of change (Bender, 2002; Song et al., 2013). Addressing these gaps is likely to strengthen the evidence-base to explain behavioral change beyond neoclassical economic and rational choice framings (Chuenpagdee and Jentoft, 2009; Fulton et al., 2011).

Research on documenting and explaining is useful for social-ecological assessments of marine systems. Systems research highlights the need for theory and evidence about microlevel change processes (Schlüter et al., 2019). In marine contexts, for example, that literature seeks evidence on fisher behavior as it functions in social and psychosocial contexts in order to build from the bottom up an understanding multi-scalar change (Stojanovic et al., 2016). Research on microlevel change processes also recognizes the important influence of the psychosocial dimension for fisher behavior (Armitage et al., 2012). More recently, research reflecting on the psychosocial dimension within microlevel change processes has turned identify knowledge needs for anticipating change. Using empirical assessments of longer-term behavioral change with the psychosocial explanation can support empirical and simulation models that account for prospective responses to environmental, social, and policy change (Essington et al., 2017).

A prospective shift on fisher behavior in context is likely to reveal opportunities to build robust description, explanations, and models of fisher behavior and lead to durable policies (Fulton et al., 2011; Wijermans et al., 2020). Chief among the benefits of contextual lessons for marine governance is stronger capacity in modeling, planning, and management systems to anticipate and address changes in which fisher behavior is involved (Lade et al., 2015; Ojea et al., 2017; Lindkvist et al., 2020). Pursuing the two opportunities in this article, then, can help marine systems research move from retrospective assessments to prospective modeling of behavior under different contextual scenarios that integrate policy change (Lade et al., 2015; Li et al., 2020).

The purpose of this research is to contribute evidence-based insights about fisher behavior relative to systemic uncertainty and change. Analysis involved examining and explaining fishers’ behavioral changes over a 50-year period in a multispecies fishery in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Northern Newfoundland and Labrador’s fishers have generations-long experiences responding to changes. These experiences include the dramatic impacts to their livelihoods, such as unemployment, outmigration, and closure of schools and communities due to the collapse of the Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) fishery (Bavington, 2010), and many other rapid changes to access and licensed allocations, or entitlements (e.g., for groundfish, shellfish, forage fish, and marine mammal species) (Ommer and the Coasts Under Stress Research Project Team, 2007). The first objective is to document and compare long-term patterns of fisher behavior by examining their livelihood pathways related to professional fishing from 1965 to 2015. The second objective is to examine behavioral changes by assessing psychosocial explanations of emotions, perceptions, and values, such as well-being. The research results provide evidence-based lessons for coastal and marine fisheries governance that promotes context-sensitivity and alternative ways to assess, address, and anticipate change (Andrews et al., 2020).

Literature Review and Analytical Framework

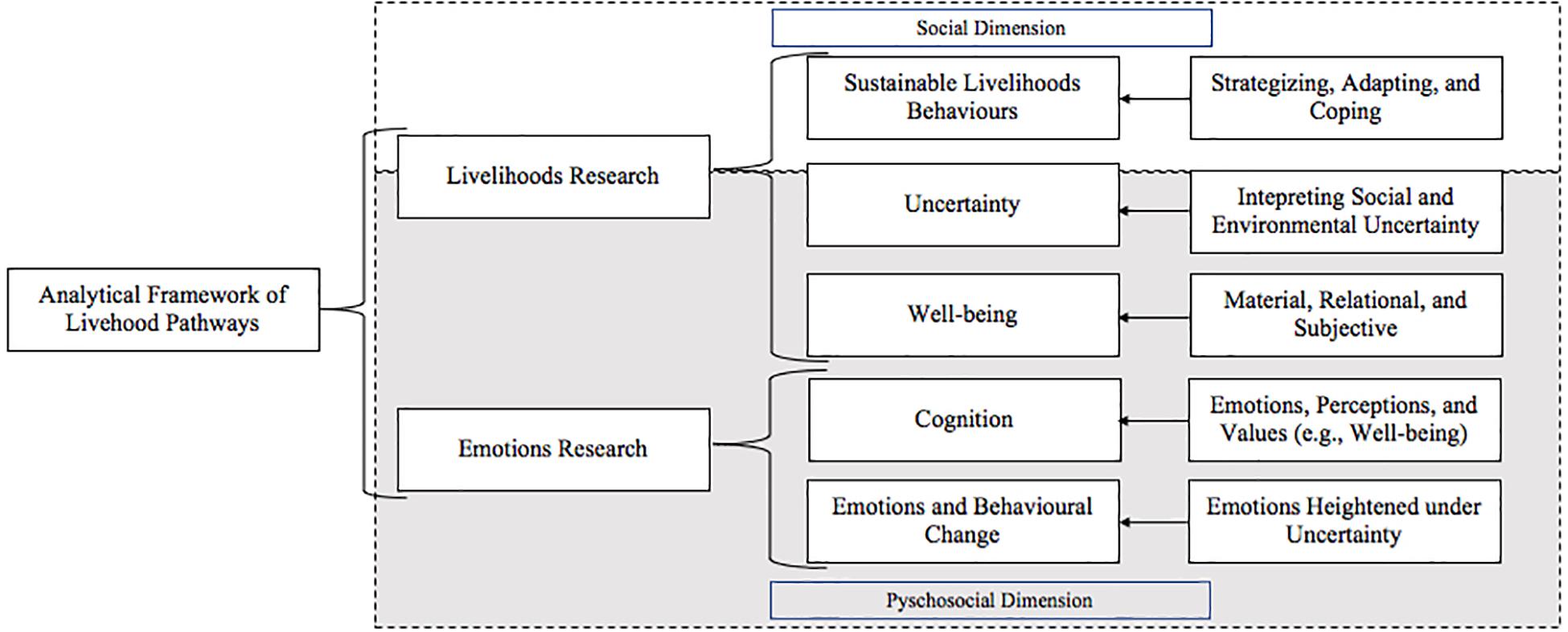

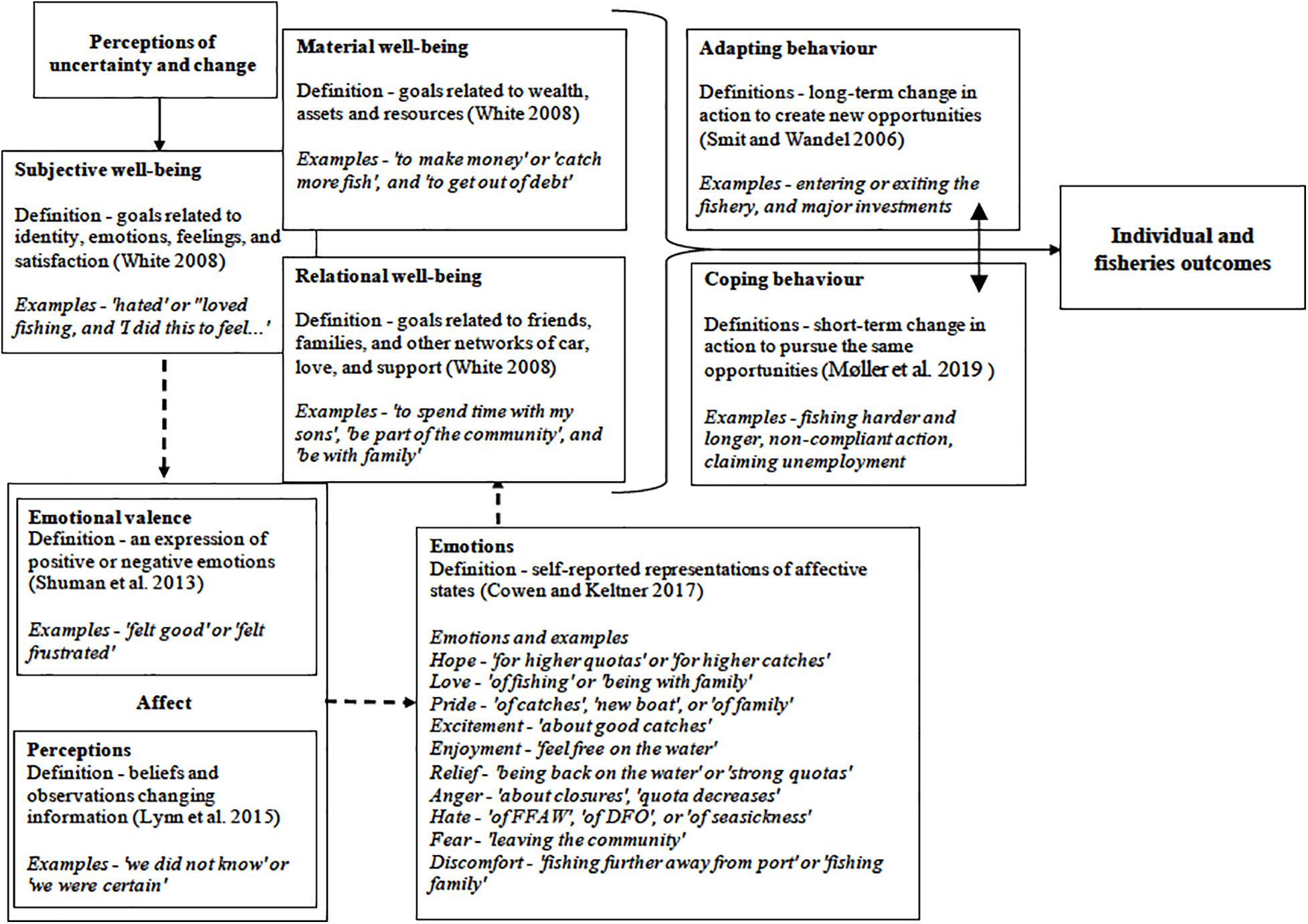

Our empirical research draws on livelihoods research (De Haan and Zoomers, 2003; Nayak, 2017), and emotions research (Feldman Barrett, 2017b; Maia and Hauber, 2020). We combine concepts from these literatures to form an analytical framework (Figure 1). Livelihoods research informs how we document patterns of fisher behavior as livelihood pathways, whereas emotions research helps explain fisher behavioral change within those pathways. Drawing from livelihoods research, concepts such as strategizing, coping, and adapting characterize observations of fishers’ decision-making and their resultant actions in relation to change. Further, livelihood research indicates well-being and perceptions of uncertainty as variables needed to observe fishers’ strategizing that precedes their coping or adapting. Emotions research unpacks the cognitive process underlying strategizing. Emotions research indicates that fisheries’ well-being is linked to their emotions and perceptions in a process known as cognition. Cognition is shaped by experiences of uncertainty that, in turn, influences fisher behavior. These two research areas, then, are complementary because they intersect at the psychosocial dimensions of fishers’ livelihood behaviors under perceived conditions of change and uncertainty.

Documenting Patterns of Behavior With Livelihoods Research

Livelihoods research is a multi-strand literature that examines livelihoods’ diversity as well as the institutions and contexts that shape and are shaped by different livelihoods (Nayak, 2017). Livelihoods are patterns of strategies, behaviors, and experiences by individuals, households, or groups to meet their economic and non-economic goals (Bebbington, 1999; De Haan and Zoomers, 2005). Livelihoods research is used to provide guidance and concepts related to how livelihoods emerge as behavior patterns, also known as ‘livelihood pathways’ (De Haan and Zoomers, 2003, 2005). Livelihood pathways are a useful concept because they help analyze how fishers navigate and express different livelihoods over their lifetimes in response to environmental, social, and governance changes. De Haan and Zoomers (2005): 44) argue that livelihood pathways represent “historical routes” that enable a long term, systematic comparison of “actors’ decisions in different geographical, socio-economic, cultural, or temporal contexts” (De Haan and Zoomers, 2005: 44). To build new evidence about fishers’ behavioral change as livelihood pathways, our research draws concepts from three livelihoods literature strands: sustainable livelihoods (Allison and Horemans, 2006), resilience (Marschke and Berkes, 2006), and well-being (Weeratunge et al., 2014).

The sustainable livelihoods strand focuses on three concepts—strategizing, adapting, coping—that characterize how individuals and groups move from decision-making to behavior change. Livelihood strategies comprise decisions that precede behavior. Strategizing refers to individuals, household, and groups beyond the household negotiating hardships and deciding to direct, alter or redistribute the intensity, direction, and focus of their efforts and resources (De Haan and Zoomers, 2003, 2005). Strategizing occurs in a social context and is informed by interactions, knowledge, and norms within households, fisheries, and communities (De Haan and Zoomers, 2003, 2005; Maharjan(ed.), 2014). For example, strategizing may include fishers discussing changes to quotas with family or crew, and prioritizing how to respond based on collective experiences and access to resources. Adapting is a behavioral response that redirects human and financial resources toward different economic and non-economic opportunities (Ellis, 2000). Redirecting resources constitutes an observable long-term behavioral change (Smit and Wandel, 2006). As such, adapting is distinct from coping. Coping is a short-term term behavioral response that involves the use of existing resources to pursue, enjoy, or protect the same opportunities (Møller et al., 2019). For example, expanding fishing effort using current resources within a fishing season can be considered as coping, whereas investing in a vessel to catch a different species or leaving a fishery can be considered adapting.

The well-being strand indicates opportunities to understand livelihoods’ patterns by focusing on various forms of material, relational, and subjective well-being as the values discussed in strategizing and pursued through behavior (White, 2008; e.g., Britton and Coulthard, 2013). Forms of well-being are psychosocial reference points for assessing behavioral change that provide insight into the different ways that fishers “act meaningfully” to enjoy “a satisfactory quality of life” (Brueckner-Irwin et al., 2019: (1). Empirical research can leverage well-being as an important starting point for assessing fishers’ professional goal orientation that informs their behavior (Andrews et al., 2020). As human values, forms of well-being are important to understand goals for adapting and coping behaviors that shape patterns in livelihood pathways. But, to explain behavioral change, this indicates other psychosocial factors are involved in behavior, particularly under conditions of uncertainty (Coulthard, 2012; Béné et al., 2019). For instance, fishers may prioritize different forms of well-being, and experience in households, communities and sectors different environmental, economic, social, political, and governance drivers of change (Béné and Tewfik, 2001; Coulthard et al., 2011). To advance, livelihood behavioral research, though, the well-being strand indicates that more interdisciplinary research is needed on other psychosocial factors in a local context (Weeratunge et al., 2014).

The uncertainty strand highlights that when fishers experience uncertainty, their coping and adapting behavior is dynamic, experimental, and therefore may or may not lead to results initially imagined and desired in individual and household strategies (Marschke and Berkes, 2006; Coulthard, 2012). According to this literature, uncertainty is a constant and problematic condition of fisheries shaped by multi-level environmental, social, economic, political, and governance factors, all of which can challenge the predictability of adapting and coping (Nayak, 2017). Resources users negotiate and interpret uncertainty when strategizing as they weigh personal and professional insecurities and opportunities associated with not knowing how change is likely to affect their livelihoods (Sagnybekova, 2017). This form of perceived uncertainty, then, can cause all sorts of delays and detours in how and why fishers cope and adapt in relation to change (Smit and Wandel, 2006; Nayak, 2017). For example, despite inclinations to act, fishers may fail to do so depending on the extent of anticipated risk or impact of change (Béné et al., 2019). The resultant behavior (or lack thereof) shapes outcomes at household and community levels (Marschke and Berkes, 2006), and therefore contributes to processes of change and environmental, economic, social, political, and governance outcomes at multiple scales (Nayak, 2017). Like the well-being strand, the uncertainty strand suggests greater insight is needed into other psychosocial factors to document behavioral change in relation to perceived uncertainty. The next section discusses concepts and evidence from emotions research to more deeply understand the psychosocial dimension of fisher behavior, including factors in cognition that help explain fisher behavioral change in relation to perceived uncertainty.

Explaining Fisher Behavior Using Emotions Research

Emotions research is an interdisciplinary field that provides evidence, theory, and policy recommendations about emotions’ central influence on individual and group decision-making and behavior, social life, and policy development (Feldman Barrett, 2017b; Wolfe, 2017; Maia and Hauber, 2020). Emotions are socially constructed representations of affect, where affect refers to the neurological and chemical appraisals of new information (Panksepp, 2008; Feldman Barrett, 2017b). People interpret their emotions and others’ emotional expressions. They discuss these interpretations in people’s everyday lives, and those interpretations influence behavior (Franks, 2010). That research draws on evidence within and beyond fisheries about how the brain and mind function to produce emotions, and the roles of emotion expression and interpretation through social, cultural, economic, and political behavior (Wolfe, 2017; Peltola et al., 2018; Maia and Hauber, 2020), including behavior expressed by fishers (Crivelli et al., 2016). The emotions research reported on below provides two contributions to understanding the psychosocial dimension of fishers’ livelihood behaviors. First, emotions research can help explain behavioral changes within livelihood pathways by combining psychosocial factors that are linked through cognition: emotions, perceptions, and values such as well-being. Second, emotions research enriches an understanding of the influence of psychosocial factors in cognition on fisher behavior under conditions of perceived uncertainty.

The first contribution of emotions research is to reveal linkages between emotions are linked with other psychosocial factors that influence fisher behavior, such as perceptions and values. The social construction of emotions, then, involves the expression and interpretation of emotions through language, vocal patterns, and gestures based on perceptions, values and experiences of affect (Franks, 2010; Feldman Barrett, 2017a). The production and interpretation of emotions are inseparable from perceptions, values, and their social context because they are based in a process known as cognition. Cognition involves affect, memory, perceptions, and values that function together to acquire, store, organize, recall, and appraise sensory information that leads to behavioral change (Bechara, 2004; Cohen, 2005). In cognition, affect functions to appraise perceived stimuli as negative or positive, a property of described by the notion ‘valence’ (Shuman et al., 2013). Appraisal is driven by goals, in this case forms of well-being, that are reference points for categorizing valence (Franks, 2010). Our experience of emotions is experienced as simultaneous to appraisal (Feldman Barrett, 2017a). If individuals appraise new stimuli as being negative and experience it intensely, they might attribute, recognize, and express this affective experience with emotional terms such as anger or fear. Expressions of anger or fear are recognizable to other people because they relate that anger and fear to their own experiences (LeDoux, 2012, 2013).

Given the importance of affect and emotions in cognition, emotions research cautions against theoretical models for behavior based in neoclassical economic and rational choice framings for behavior. Rational choice theory, for example, refers to a series of assumptions that individual behavior reflects a pursuit to maximize utilities (Kahneman, 2003), often assumed to be material and economically based such as goods and profit (Zafirovski, 1998). The decision-maker is presumed to have access to all necessary information to make optimal decisions by drawing on an infinite cognitive capacity to choose optimal bundles of rewards (Simon, 1990). Moreover, decision-making is presumed to be conducted through a dispassionate decision-making process (Loewenstein and Lerner, 2003). Emotions research indicates that emotions and affect influence individual and group behavior in ways that discount and make implausible the dispassionate decision-making engendered in economic and rational choice assumptions (Bechara, 2004; Cohen, 2005).

Evidence from emotions research indicates that moving beyond economic and rational choice into more psychosocially informed frames for cognition and behavior can help fisheries scientists and policy makers better understand and anticipate behavioral responses and expectations related to social, environmental and policy changes (Chuenpagdee and Jentoft, 2009; Andrews et al., 2020; Nightingale, 2013). For example, in a study on Tongan fisheries, perceptions, values and emotions shaped fishers’ patterns of effort and collective action (Bender, 2002). Tongan fishers perceived fish as autonomous actors, and this perception was shaped by values that promoted spirituality in everyday activities such as fishing. However, fishers’ perceptions led to a low sense of responsibility over exploitation. Fishers believed that fish stocks declined because fish chose to swim away. Those perceptions interacted with feelings of sadness and readiness to help one another out when fish left. These emotions promoted cooperation and coordination during stock declines. They also led to limited support among Tongan fishers for policies that excluded access to fish stocks, as those policies were seen as addressing a problem that did not exist (fish went away on their own) and were likely to disrupt patterns of cooperation and coordination. Examples like this highlight opportunities for an understanding of emotions in combination with perceptions and well-being (see Béné et al., 2019) to better understand the psychosocial dimension for fisheries policy implementation (Nightingale, 2013).

The second contribution includes evidence about the heightened role of emotions in individual and group strategizing shaped by perceived uncertainty. Through strategizing, individuals draw on their memories to assess the familiarity of an experience and use those memories to categorize both the intensity and valence of the experience (Shuman et al., 2013). In group strategizing these affective experiences are shared as emotions (Thagard, 2006). Individual and shared affective appraisals shape perceptions of new information in relation to goals that emotions researchers characterize as human values such as living well, making money, building relationships, or making sound decisions (Franks, 2010; Van Kleef, 2016). However, under conditions of perceived uncertainty, the experiences of affect are heightened, and overall cognition is less reliable (Etzioni, 1988; Feldman Barrett et al., 2007). In other words, as individuals or groups, the power of emotions is heightened without commensurate increases in the reliability of perceptions, and this leads to potentially unpredictable behavior (Thagard, 2006).

Emotions under perceived uncertainty can, then, diverse and potentially counter intuitive patterns behavioral responses to social and environmental change (Carmi et al., 2015). Heightened affective experiences and perceived uncertainty lead to more intensely experienced and shared emotions (Cohen, 2005). Group negotiation of emotions creates a feedback that can intensify individuals’ emotional experiences within groups in ways that can strengthen or entrench individuals’ perspectives and therefore reinforce behavioral patterns (Van Kleef, 2016). Alternatively, groups can reprioritize their values which can lead to behavoiural change (Van Kleef, 2016). Diverse patterns of fisher behavior, then, may emerge as some groups change their behavior based on negotiation of emotions and perceived uncertainty and other groups do not.

For example, in a study on Scottish inshore fisheries, Nightingale (2013) documented fishers strategizing as a group about their fear related to bad weather. She also documented that fishers experienced excitement and elatedness when negotiating bad weather. This research identified two behavioral responses, including staying on the water or traveling back to the home port, and this was informed by positive or negative emotions. Using findings like this, Nightingale (2013) argued that incorporating the psychosocial dimension in relation to patterns of behavioral change can strengthen marine governance. She concluded that fisheries policies are likely more effective when developed and implemented with consideration of diverse behavioral responses, and in order to do that, insights on psychosocial factors like emotions, perceptions, and values are required. More can be studied about these relationships. Little is known about patterns fisher behavior change that exist over time, and what new lessons for coastal and marine fisheries governance can be gleaned from that kind of investigation. Returning to this study’s objectives, then, opportunities exist to leverage concepts in livelihoods research to document livelihood pathways overtime, and to explain patterns of behavioral change in those pathways by drawing on emotions, perceptions, and values in the context of perceived uncertainty. Next, we describe the setting and methodological approach with which we document inshore fishers’ livelihood pathways, and use emotions research to assess changes in their adapting behaviors.

Study Setting

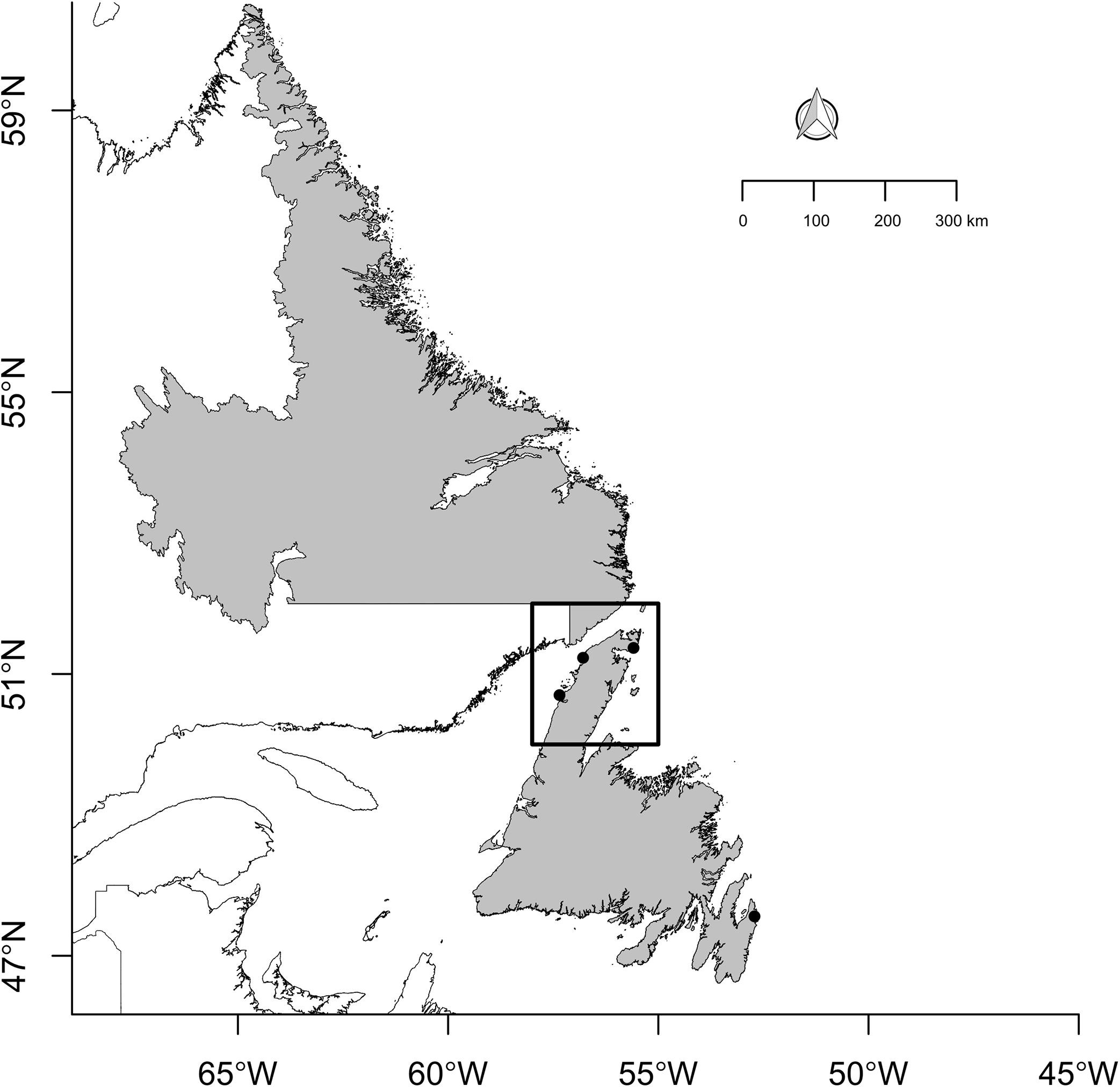

This research took place in small villages and towns along the coast of the Great Northern Peninsula, Newfoundland and Labrador. The Great Northern Peninsula is 270 km long and its northern half—a low-lying coastal area—is surrounded by key fishing grounds in the Gulf of St. Lawrence to its west, the Strait of Belle Isle on its north, and the Labrador Sea and White Bay on its East (Figure 2). Currently, the peninsula includes 69 distinct villages and towns (hereafter communities), with populations ranging from 50 people on the peninsula’s western and eastern coasts to 2250 in St. Anthony on the northern tip.

Figure 2. Map of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, with Great Northern Peninsula highlighted in black box and three examples of communities included in the research—Port au Choix, Green Island Brook, and St. Anthony—highlighted with black dots.

Commercial fishing is the primary industry in the St. Anthony-Port-au-Choix region followed by tourism, forestry, and oil and gas development and exploration. Typically, fishers belong to inshore (vessels 14’ to 64’) and offshore fleets (vessels 190’ to 290’)1. This research investigates behaviors related to the inshore fisheries. The inshore fishing fleets operate within an 80 km range of the coastline, and land their catches in local harbors (McCracken and MacDonald, 1976; Sumaila et al., 2001). Landings are then processed by family members and other residents working in local processing plants, if a plant exists in that area (Ommer and the Coasts Under Stress Research Project Team, 2007).

Since the 1970s, the inshore fishers have lived through and responded to a number of linked environmental, social, and policy changes (Khan and Chuenpagdee, 2014). These have included extensive and cascading changes and more continuous changes (see Schlüter et al., 2019). The most notable extensive change is the commercial and near biological collapse of North Atlantic cod [Gadus morhua] fisher in 1992. To respond to the collapse, the Canadian federal government and its Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) ministry instituted a multi-year moratorium on commercial cod fishing initially intended to last two years. However, the cod fishery remains closed except for sentinel (scientific) fleets and commercial fleets with small allocations (Bavington, 2010). The same year, the commercial salmon fishery was also closed. Fishers who remained in the cod fishery were provided with retraining programs in the province’s capital, St. John’s, and some were allotted temporary permits to harvest northern shrimp (Pandulas borealis)2. Others remained with allocations for shellfish, forage fish, and marine mammals such as seals.

In the modern history of fishing in Newfoundland and Labrador, the cod collapse and subsequent restructuring is a reference point to understand continuous changes to which fishers respond.

Before the cod collapse, strategic behaviors like entry, investment, and effort were driven by informal training traditions (e.g., youth participation and mentorship) and the availability of new technology. In the 1970’s, examples include the adoption of the Japanese cod trap, longliners, and gillnets that increased capacity (Ommer, 2002). Cultural and technological change was set on a backdrop of economic changes. These included the implementation of the Exclusive Economic Zone and subsequent single species regulation in 1977 that increased local entry, competition and extensified effort. Further, provincially led economic development disrupted including interrupting informal economies and subsistence practices by attempts to develop new sectors including industrial logging (Ommer, 2002).

In the 1980s, the size of cod and volume of catches started to decline with uncertain but concerning implications felt by fishers and communities (Rose, 2003). Further, the industry suffered a financial collapse that stimulated increased borrowing with adverse implications to fishers and households. Many fishers suspected and called for government intervention yet were surprised by the extent of intervention (Mather, 2013). After the moratorium the shellfish industry grew with peak stocks and allocations for northern Newfoundland fishers in the mid 2000s (Khan and Chuenpagdee, 2014). Since the early 2010s, however, ocean warming has created new uncertainties. Particularly, this includes precipitous decreases in shellfish populations and allocations that are only stabilized by high market values, and the potential for a shellfish collapse and rebound of groundfish potentially requiring another restructuring of the inshore fishing industry (Rowe and Rose, 2017).

The inshore fishery is primarily governed by DFO which coordinates with a labor union, Fish and Food Allied Workers (FFAW-Unifor) that represents fishers and processors, and with international partners such as the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization. Governance for the inshore fishery is guided by economic, ecological, cultural and institutional objectives articulated in Canada’s Fisheries Act (1985), Ocean’s Act (1997), and Species at Risk Act (2002). Canada’s Fisheries Act’s regulations and Canada’s licensing policies further elaborate how fishers can enter, pass down or sell their enterprises, and exit the fishery.

Overtime, fisher behaviors in NL have been shaped by an evolving policy regime marked by three changes (Ommer, 2002; Rose, 2003; Khan and Chuenpagdee, 2014). First, limited entry license system began in 1981 creating individualized market that prevented fishers from pursuing multiple species with corresponding licenses, and later encouraged new investment. Second, after the cod collapse, rationalization shaped increased emphasis on buyback, retraining, and professionalization that, in turn, shaped entry, exiting, investment, and diversification behaviors. For example, after 1996, fishers discussed entry in terms of two regulatory categories (core v. non-core) introduced in that year with reference to a certification program with graduated entry (Apprentice, Level 1, and Level 2) introduced in 1997. Third, policies were introduced to protect the inshore fishery. Most notably, the promotion of the inshore fishery was incorporated into The Policy for Preserving the Independence of the Inshore Fleet in Canada’s Atlantic (2007), which restricts vessel size, ensures individual ownership of fishing enterprises, and prevents the integration of enterprises with the processing sector. The owner-operator policy is now formally recognized in Canada’s revised Fisheries Act (2019) and policy goals that refer to ‘fleet separation’ and ‘promotion of the independence of license holders.’ In addition to professionalization, policy changes are brought to bear in DFO decision-making that has been marked by dramatic annual shifts for the inshore fishery including annual spatio-temporal access decisions, output controls such as Total Allowable Catch limits and individualized quotas, and input controls such as fleet and gear restrictions for the inshore. This process is marked by perceived uncertainty. Year to year, fishers do not know what their access and allocation will be for the spring, and they do not know what their income will be until the fall when their catch is sold.

Materials and Methods

This research follows a qualitative case study approach using three iterative phases: scoping, data collection, and analysis. First, scoping was conducted with five fisheries scientists who conduct research in the study area and meetings with 15 community mayors to identify (1) key issues faced by inshore fishers and (2) receive guidance for recruiting and interviewing fishers.

Second, data collection began with participant recruitment using a snowball sampling strategy (Noy, 2008), starting with referrals from mayors, and then subsequent referrals from inshore fisher participants. Recruitment included phone calls, visiting harbors, local coffee shops and participants’ houses to introduce the research. Participants making a snowball referral were asked to contact the new potential participant to let them know that they would be approached for an interview, so as not to place undue pressure on the participant. Throughout the recruitment process, participants were ensured that their participation was voluntary and confidential.

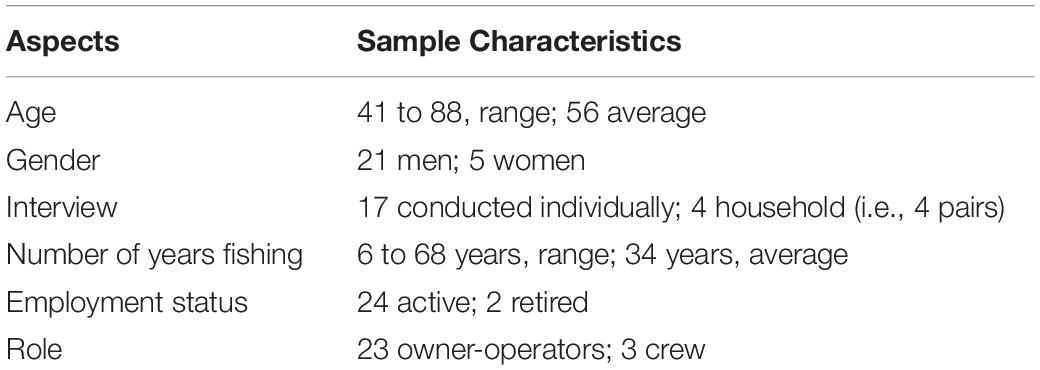

Research participants included fishers who pursued two or more fish species currently or formerly in coastal waters off the northern tip of the Great Northern Peninsula (n = 26) (Table 1). Those participants were interviewed using a narrative approach (see Supplementary Material 1). Narrative interviewing elicits participants’ stories about how they viewed and responded to events in their life (Jovchelvitch and Bauer, 2000). Narrative interviews are contextual and often cover broad time scales and topics (Junqueira Muylaert et al., 2014). Narrative interviews are therefore distinct from semi-structured interviews that tend to focus on specific topics which may or may not be situated in their context (Jovchelvitch and Bauer, 2000).

Third, data were analyzed using a content analysis technique that guided assessment of individual or household fisher narrative themes, and then allowed comparison of themes across those varied livelihood pathways. Content analysis refers to the systematization of interview content by coding themes, and the relationships among those themes, all while reflecting, journaling, and diagramming those relationships iteratively (Clandinin, 2006). Content analysis’ balance between systematic coding and iterative reflection was appropriate for analyzing and interpreting the meaningful stories included in narrative interview data (Clandinin, 2006).

The content analysis was conducted using by-participant, narrative comparison, and thematic comparison. For by-participant analysis (e.g., Murray et al., 2006), data were segmented into single narratives for each fisher to provide individual chronology of behavioral events. Coding assessed behavioral events and their explanations in each narrative. Second, narratives were compared as units of analyzes, reflecting a narrative analysis (Lal et al., 2012). Comparing groups of narratives was conducted based on their convergence and incongruence on codes from single-participant analysis. In this research, patterns of behavior were apparent in relation to different types of well-being and substantiated groupings of livelihood pathways. Thematic analysis was used to examine adapting behavioral explanations with particular attention to self-reported psychosocial variables in the dataset. Insufficient data existed to assess explanations for coping behavioral change (see Supplementary Material 1). Codes were re-applied to the entire dataset and assessing congruence and incongruence among codes about psychosocial variables.

Variables, operational definitions, and example codes are included in Figure 3. Latent variables, such as implicit emotions demonstrated through voice or facial expressions were not assessed. Interview data were analyzed using QSR International’s NVivo 12, a qualitative analytical software and codes, reflections and diagrams were created and housed in Microsoft Excel (2012). This research was approved by The University of Waterloo Office of Research Ethics (ORE) (ORE# 22704) on January 31, 2018.

Figure 3. Variables, operational definitions, and example codes (dashed arrows reflect conceptual relationships from emotions research and solid arrows reflect contributions livelihood research).

Results

Our results addressed two objectives: (1) document and compare inshore fishers’ (IFs) behavioral responses to change and uncertainty as livelihood pathways, and (2) examine explanations of behavioral change by assessing the influence of emotions, perceptions, and well-being. The results below are organized into two sections. First, an analysis of IFs livelihood pathways that were grouped according to economic and relational well-being (i.e., narrative comparison) with stories and examples (i.e., by-participant analysis). Second, results included descriptions of emotions as forms of subjective well-being related to both coping and adapting behavior. Then, results include the roles for combinations of emotions, perceptions, and forms of well-being that contributed to explanations of adapting behavior changes and avoidance of behavioral change.

Documenting Fisher Behavior as Livelihood Pathways

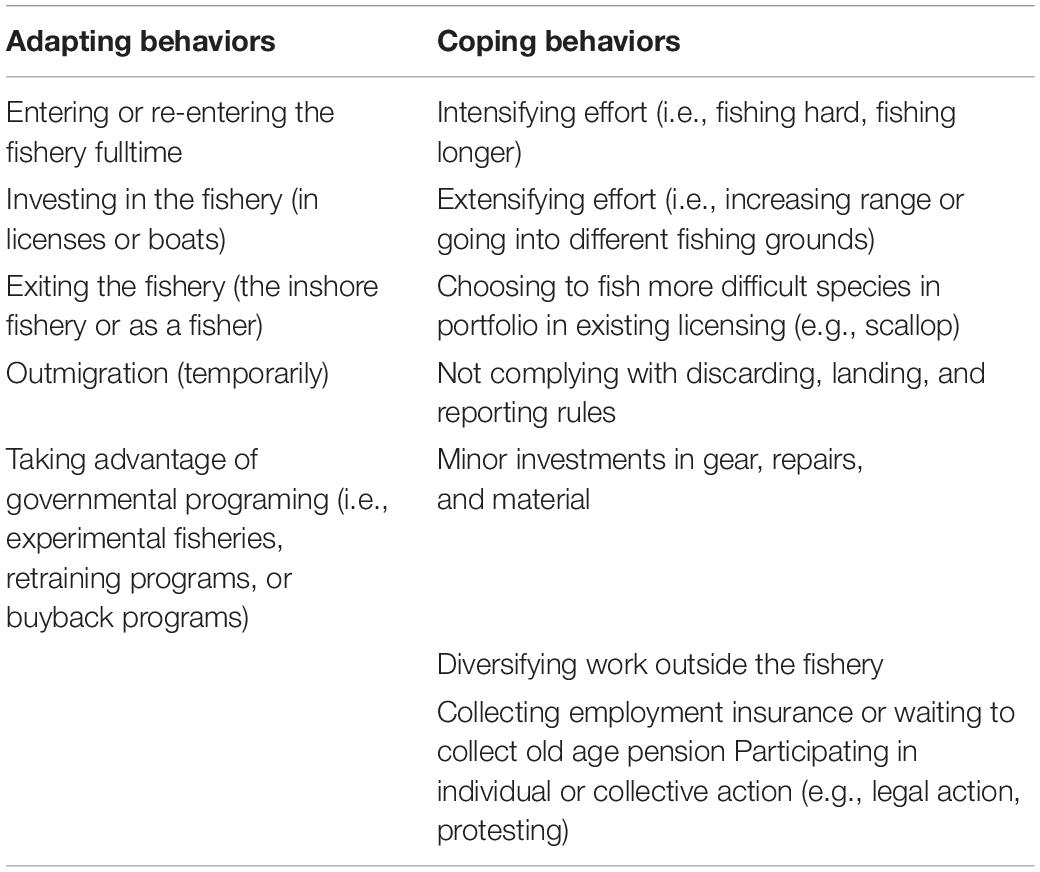

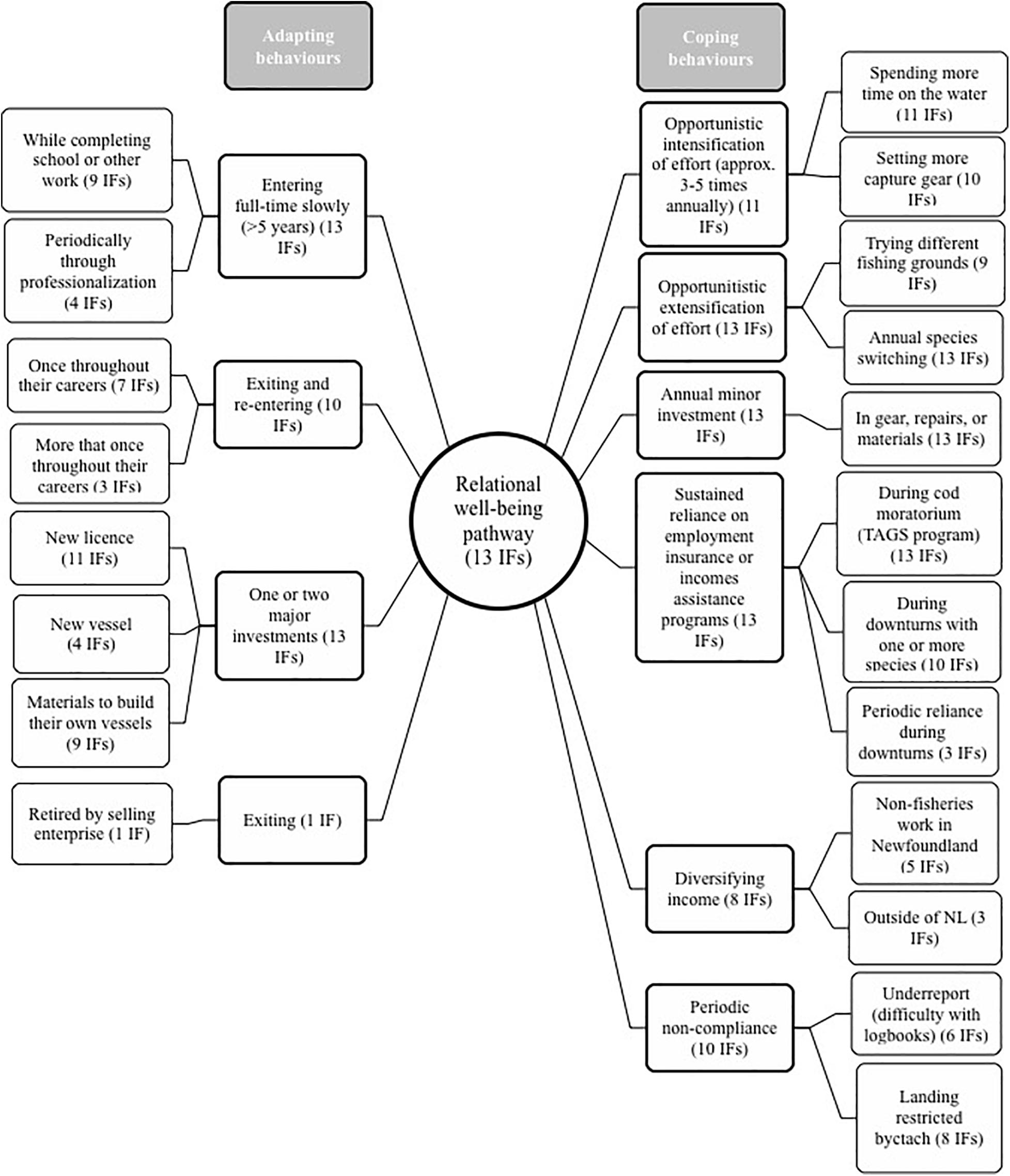

Livelihood pathways refers to patterns of behavioral change that manifest across time (De Haan and Zoomers, 2003, 2005). Five adapting and seven coping behaviors were recorded from the livelihood pathways analysis (Table 2).

In some instances, adapting and coping were inter-related in that coping delayed adapting, and adapting created new coping opportunities (Smit and Wandel, 2006). For example, 21 IFs indicate that claiming employment insurance or considering claiming old age pensions were notable coping behaviors because they delayed adapting behaviors.3 During fishery downturns – i.e., weakened fish stocks, lower quotas, or low prices for catches – collecting employment insurance, referred to as “stamps” (12 IFs), or waiting until eligibility to claim old age pension (9 IFs) caused some fishers to, as described by IF1 “wait it out.” IFs reported that strategizing for adapting behaviors largely took place in the household, whereas coping behaviors were decided on vessels, in landing areas, and in other aggregating sites, such as coffee shops.

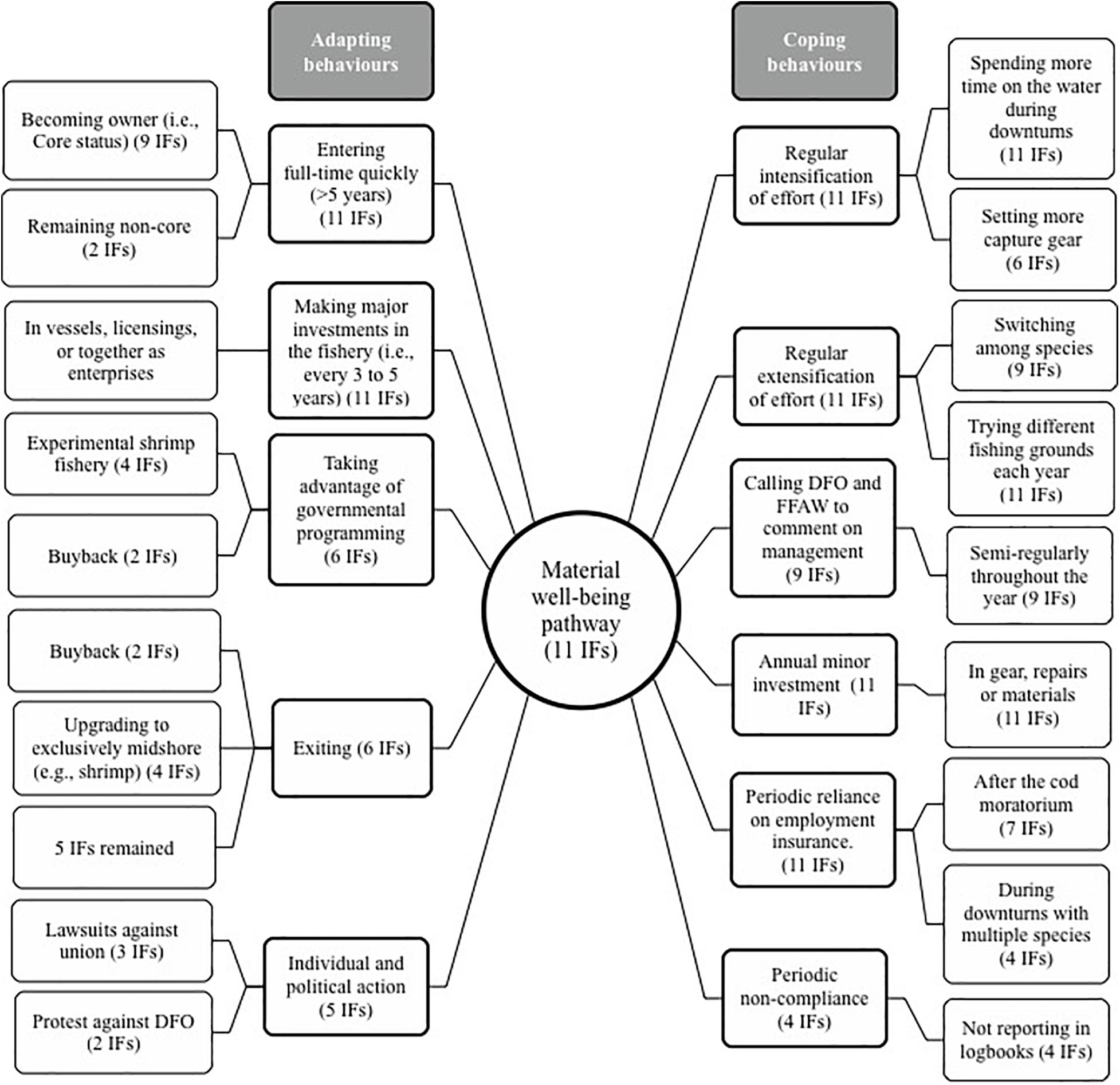

A comparison of IFs’ individual livelihood pathways revealed patterns in types, frequency, and forms of well-being associated with adapting and coping behaviors. Patterns were recorded as categories of livelihood pathways characterized by the well-being form most often associated with adapting and coping behaviors—a material well-being pathway (11 IFs) and relational well-being pathway (13 IFs). IFs were categorized according to material or relational well-being pathways when those IFs expressed most adapting and coping behaviors in relation to material or relational well-being. Those patterns reflected a prioritization of that form of well-being. However, several IFs expressed behaviors related to a different form of well-being reflecting a trade-off of values at critical times in their lives and in the fishery, such as when they entered and exited during downturns in the fishery (e.g., during closures, lower quotas, or low values for landings). Some coping behaviors, such as intensifying and extensifying effort, claiming employment insurance, and making annual minor investments were attributed to both material and relational well-being pathways. Adapting behaviors were attributed to subjective well-being, but no IF expressed their behavior systemically for subjective well-being. Rather, IFs discussed one or two instances when they expressed adaptive behaviors for subjective well-being (see subsection 5.2.1). Two IFs did not indicate enough information about behavior and its goals for categorization into a material or relational pathway.

The Material Well-Being Pathway Group

The material well-being livelihoods pathway group involved IFs’ livelihoods characterized by adapting and coping behaviors driven by catching more and higher value fish stocks, and earning higher profits every year (Figure 4).

Six IFs discussed material well-being as the only value informing their behaviors in the fishery. The other five IFs indicated material well-being was only a priority and indicated that one or two adapting behaviors in fishery were informed by relational or subjective well-being. Common to the material well-being pathway were adapting behaviors expressed to increase individual capacity: entering fulltime within five years and making (or trying to make) major investments in the enterprise every three to five years. Moreover, each season IFs expressed coping behaviors to maintain or increase catches through intensifying and extensifying effort. Also common were actions taken against DFO and FFAW resources including phoning representatives regularly or even participating in legal actions and protests. Seven of the 11 IFs discussed how their behavior led to growth of their enterprise in expected ways. For example, four of those IFs ended up upgrading out of the inshore fishery harvesting groundfish and forage fish, and into the midshore fishery exclusively for northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis) and snow crab (Chionoecetes opilio). One of those five IFs remained inshore harvesting groundfish and forage fish, and “felt good” that he was able to buy two enterprises after years of “living paycheck to paycheck” for several years after the cod moratorium (IF2). Two IFs discussed how they exited the fishery by selling their enterprises through a buy-back program. Five of the 11 IFs indicated their behaviors were often ill-timed and resulted in suboptimal personal outcomes. They remained in the inshore fishery despite considerable financial and health-related challenges. Next, results include some examples from a by-participant analysis that are indicate how the ‘material well-being’ pathway group manifests over time.

The stories of two brothers (IF2 and IF3) are indicative of the material well-pathway group. IF2 and IF3 invested considerably in the northern shrimp fishery and ended up upgrading out of the inshore fishery between the mid-1980s and mid-2000s for the purpose of catching more fish and earning higher incomes (stories indented for emphasis):

IF2 and IF3 were both born in the 1960s. They grew up and lived all their life in the same fishing community. They both entered together as part time harvesters in the 1970s to fish with their father, who was harvesting fulltime. With the onset of licensing for fisheries, they quickly moved to fulltime fishers owning separate enterprises. In the late 1980’s, they fished through the moratorium because they had switched to shrimp when DFO tried an “experiment to open up the shrimp” fishery (IF2) and they fished “smaller and fewer cod” and “more gillnets” (IF3). In 1990, they invested in a new enterprise (i.e., 64’ boat and license for shrimp) along with investing in new gear (i.e., moving from gillnets to otter trawls). In the late 1990s, they noticed a considerable return on their investment into the shrimp fishery, although they kept harvesting scallop to offset periodic “bad years” with shrimp (IF3). In the early 2010s, they discussed buying another enterprise, but as IF3 indicated, they “couldn’t see any vision for it.” Moreover, IF2 argued the regulations and quotas changed to make fishing less financially viable. However, both IF2 and IF3 indicated they will fish until they are no longer able. IF2 said, he will “fish till he gets sick.” When that happens, both IFs state they will use a regulatory process to “let their sons take it over” and take a small cut from their income, which they admit would be a “small fraction of the value” for the enterprise (IF2).

IF2 and IF3 made, as both described, “good decisions in the fishery.” To them, good decisions resulted from decades of strategizing about changes in fish stock status of cod and northern shrimp. They invested in new opportunities to take advantage of an experimental governmental program, and chose not to invest when they thought the declining economic viability of the northern shrimp fishery was going to persist. By describing their ‘good decisions’ in relation to expected financial returns, the stories of IF2 and IF3 demonstrated a prioritization of material well-being. Outcomes from prioritizing material well-being included shifting their capacity and capital to fisheries to the midshore fishery by moving partially to the shrimp fishery in the late 1980s, and giving up fishing ‘inshore’ species like scallop in 2006. However, their decisions to ‘fish till they get sick’ despite declining shrimp stocks, and to transfer their enterprises to their sons for low financial returns represented trade-offs of material well-being associated with expected financial returns with relational well-being associated with promoting the goals of family members.

Not all IFs in this pathway group experienced positive or expected outcomes. For example, IF5, IF6, and IF7 remained in the fishery despite considerable hardships. They made several attempts to upgrade, but were unsuccessful. In the meantime, IF6 explained how they made attempts within fishing seasons to increase catches by increasing hours on the water fishing scallops, a very difficult stock to fish in a small boat. During this time, IF5 even lost a finger while fishing, and IF6 and IF7 discussed how their mental health rapidly deteriorated because as IF6 indicated, they felt “helpless.” IF7 stated that they just fish now “for stamps,” i.e., to qualify for employment insurance.

The Relational Well-Being Pathway Group

The relational well-being livelihoods pathway group involved 13 IFs’ livelihoods characterized by behaviors informed by maintaining relationships with families (within and outside of households) and friends and neighbors in local communities (Figure 5).

For example, relational well-being was expressed by choosing fishing as the main source of income despite downturns because it was an opportunity to spend time with family (7 IFs). Additionally, IFs discussed fishing as important for the survival of families and of local ‘culture’ in communities (6 IFs). Common to the relational well-pathway group were slow attempts at becoming a full-time fisher. A slow attempt reflected completing school or work before certification programs were introduced or taking time to navigate requirements of certification while working in other sectors. Also common were dynamic exiting and entering the fishery to seek work elsewhere to enable living in fishing communities longer term. Rapid exit and re-entry, along with diversifying incomes outside of Newfoundland and Labrador reflected a dynamic quality not found in the material well-being pathway.

Inshore fishers in the relational well-being pathway group often made one or two major investments to enter or upgrade, and most had, at one time, built their own vessel. As such, investment behavior was more sporadic than in the material well-being pathway. Rather, IFs in the relational pathway relied on a diverse suite of coping behaviors to sustain themselves financially: 11 IFs discussed in terms of making a modest living, expressed by phrases like “getting enough to get by” (IF8) or “just to make little living” (IF9). Some IFs indicated that a modest living was around 25,000 to 50,000 Canadian dollars annually.

The story of IF8 demonstrates the dynamic nature of adapting and coping behaviors reflected in the relational well-being pathway group. IF8 exited the fishery temporarily during the cod moratorium, and then re-entered and diversified income sources:

IF8 entered the fishery as a teenager working in summers with his father while he finished high school before the cod moratorium before professionalization. After the moratorium, he diversified his income by working in the oil and gas sector in Alberta in the winter, and harvesting groundfish and scallops in the summer. During this time, he would save his money to use for investment in gear upgrades performed before the fishing season opened. In the early 2000s, he exited the fishery completely and spent four years working exclusively in Alberta. During this time, he saved enough to purchase a larger inshore vessel (64’11”) and licenses to harvest scallop and lobster knowing that scallop fishing was hard work and that catch rates and values for lobster, at that time, were low. He remarked that “it was good after the first paycheck, but then it was all down hill.” He returned because he felt that “his mind was always back [in Newfoundland]” with his family. To supplement his income, he began building and selling new gear and is starting to build a tourism operation.

This story illustrates a common adapting response to the cod moratorium: exiting the fishery to work outside of Newfoundland and Labrador (Bavington, 2010). Less common, however, was IF8’s return after several years to re-enter and invest considerably in a fishery. IF8 believed entering into the scallop and lobster fisheries was difficult work and might not provide a financial return on his investment. His comment that his “mind was back” in Newfoundland with his family demonstrates relational well-being, and a willingness to potentially trade-off material well-being (or take financial risks) to be with his family.

Twelve of the 13 IFs remained in the inshore fishery and were planning to fish while their health permitted (one IF retired). When their health declined, three IFs indicated they were going to sell their enterprise to retire, and 9 IFs stated that they were going to sell to their children. Three of those 13 IFs discussed how they were waiting for old age pension. At the time interviews were conducted, nine of 13 IFs remained in the inshore fishery with smaller enterprises (i.e., 28’ and under and several groundfish and forage fish licenses). Four of 13 IFs remained or retired with larger enterprises and mixed licenses for groundfish and shellfish. The larger-scale IFs indicated that they were successful because of keeping costs low by building their own vessels and conducting their own repairs. However, the IFs that remained at a smaller capacity discussed how they made financial sacrifices staying with family or fishing with friends and family in their community. These IFs experienced considerable hardships brought on by decreasing allocations or fish stocks. IF9 discussed this “death by a thousand cuts” to his livelihoods. IF10 indicated that he “had nothing to catch.” Yet, IF10 still planned to fish with his three sons despite the financial hardship:

We did not have much money to throw at our boat. We had to get along with what we had. Lots of times we were thinking to get out of it, but I got three boys [with whom he fishes] and they didn’t seem to want to do [exit] yet and I didn’t force em and I am glad I didn’t because to have them there with you, I mean there is nothing any better. I’m proud. I’m blessed with that part of it I guess.

IF10’s comment indicates a trade-off of material well-being for relational well-being pathway. That trade-off resulted from difficult discussions about staying in his community with limited resources. This quotation also hints at the role of subjective well-being with his comment on “there is nothing any better” and the function of emotions related to ‘feeling proud.’ In the next section, results include discussions the role of emotions as subjective well-being, and as factors that shaped behavioral change because of the presence of emotions in strategizing related to values and uncertainty.

Explaining Fisher Behavior and Strategizing Using Emotions Research

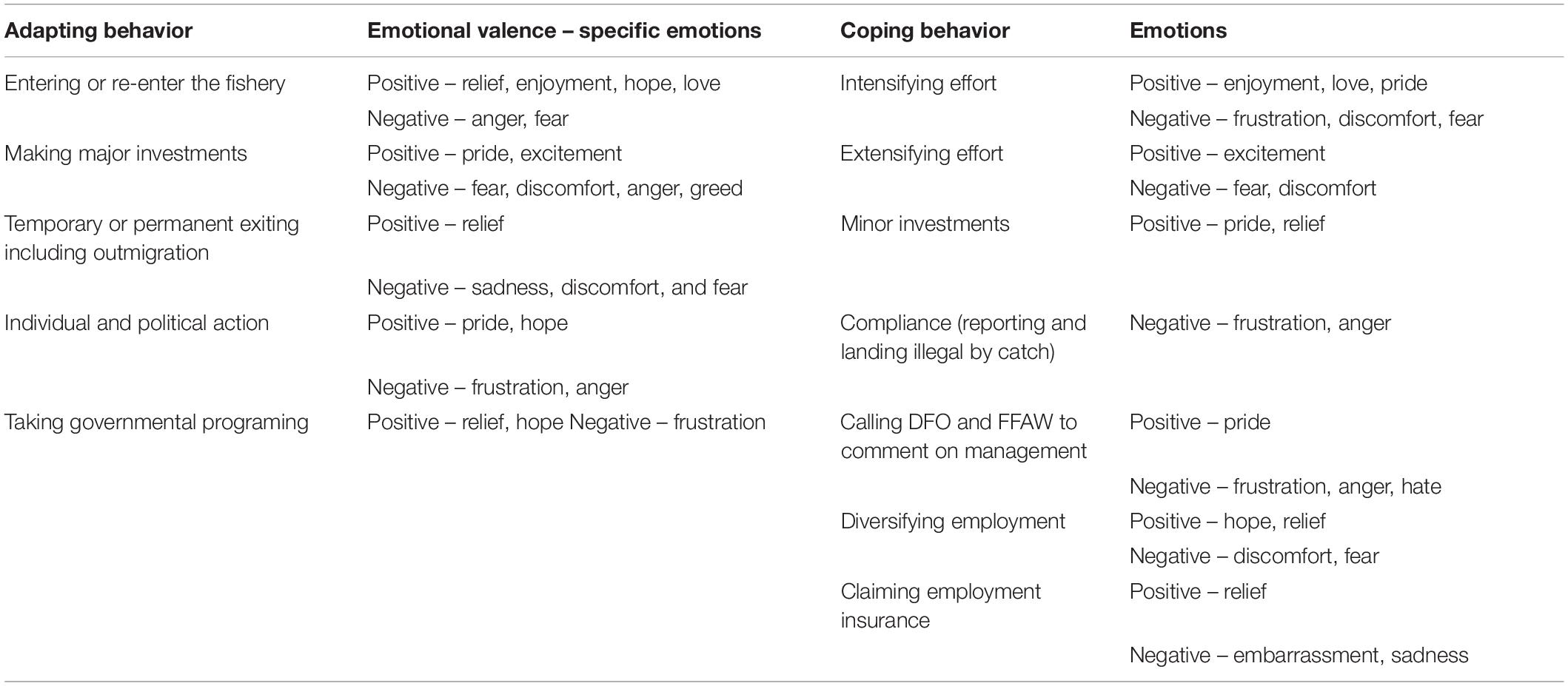

Emotions are socially constructed representations of affect that are linked, through cognition, to a person’s perceptions and values (Feldman Barrett, 2017b). Our results indicated a range of positive and negative emotions that IFs associated with specific behaviors (Table 3).

An emotions analysis in relation to behavior revealed two different functions important for understanding strategizing and behavioral changes in livelihood pathways. First, emotions served as goals for behavior, which were recorded as attempts to advance subjective well-being. Second, perceptions, emotional valence, and self-reported emotions informed strategizing that influenced adapting behavior changes or avoiding behavioral change.

Next, we turn the first function of emotions as forms of well-being goals.

Emotions as Subjective Well-Being Goals

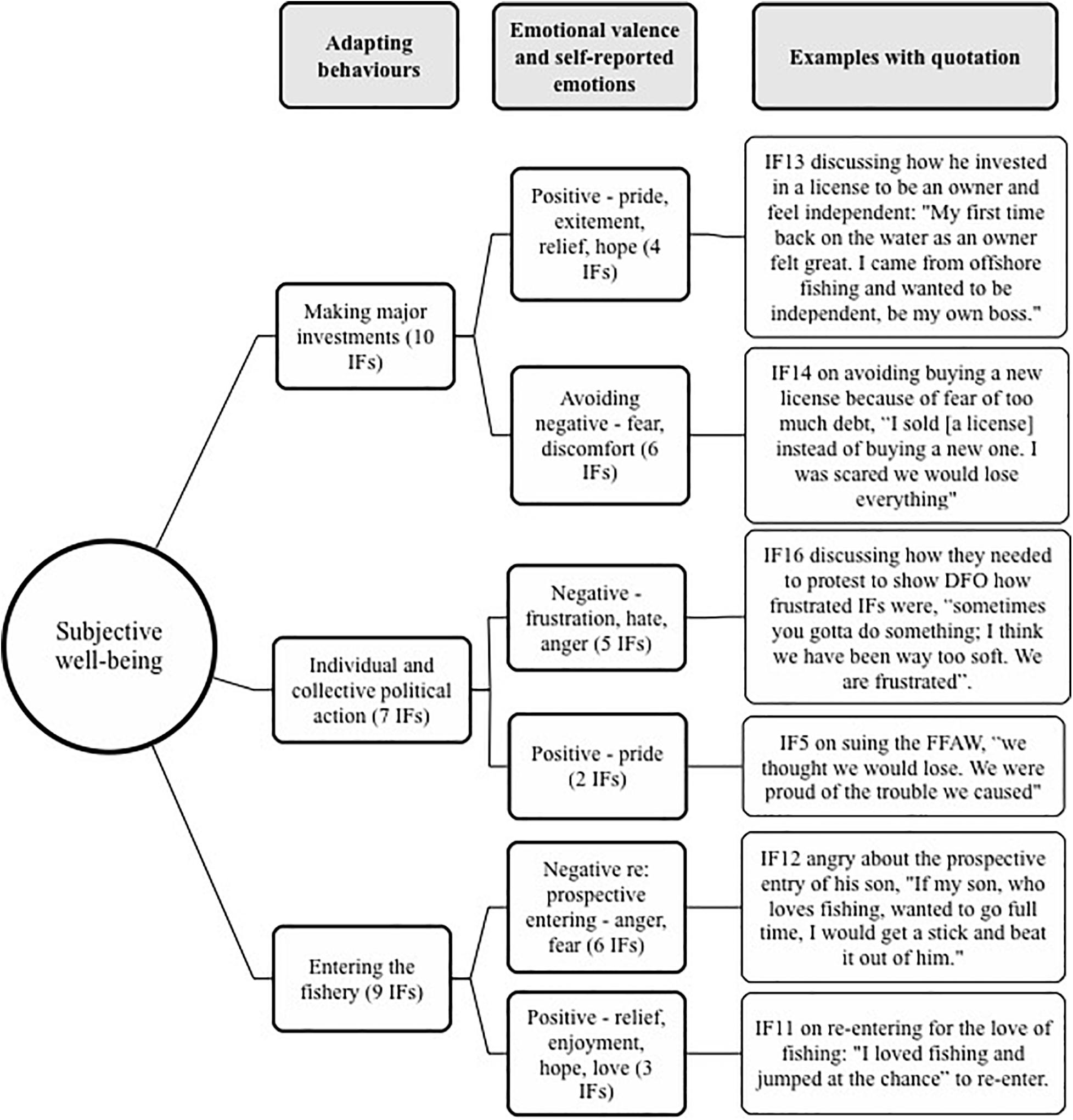

Across both IFs’ livelihood pathway groups, we recorded instances when some livelihood behaviors were expressed to advance subjective well-being reflecting a positive emotional experience or avoiding a negative emotional experience (Figure 6).

Positive emotions included pride, relief, hope, love, and excitement, whereas negative emotions included frustration, hate, anger, discomfort, and fear. For instance, IFs discussed how emotional experiences were a goal for entering or re-entering the fishery, making major investments in vessels and new licenses, and participating in political action, individually or collectively, such as protesting or suing the FFAW. Moreover, subjective well-being informed strategies to avoid certain behaviors and promote other forms of well-being. Responding to decreased shellfish allocations, Six IFs recounted how they discouraged their children from entering the inshore fishery because of their anger or frustration with fishery downturns and because they wanted their children to have better economic opportunities. IF12 indicated he wanted his children to have a “better go of it.”

Across the livelihood pathway groups, emotions as subjective well-being goals functioned situationally and sporadically. Fishery economic changes in Newfoundland informed adapting behaviors related to entry and investment taken to advance subjective well-being. For example, four IFs were able to re-enter when a new vessel became available or when fish stocks for which they were licensed were, as IF17 indicated “doing well.” Moreover, economic downturns, new fisheries policy announcements, and social opportunities shaped coping behaviors such as political action. For example, three IFs indicated that they protested when DFO announced significant decreases to shrimp or crab quotas and were mobilized by community leaders, whereas two others participating in legal action when they were approached by community leaders with the opportunity. In some cases, emotions as forms of subjective well-being emerged when IFs traded-off relational or material well-being. The brief story from IF18’s livelihood pathway highlights how a trade-off of material well-being for subjective well-being emerged over time and was informed by his financial situation and the economic viability of lobster fishing in the late 1990s and throughout the 2000s:

In the mid 2010s, IF18 sold his enterprise for over a million dollars. He indicated he had over a decade of success in the lobster fishery due to high prices for lobster and some good years when catch rates and quotas were high. High prices and good years helped him stay out of debt and earn considerable annual incomes. In the next year, he got the opportunity to join with a friend as a crewmember. In the following offseason, he used some retirement savings for materials to build a smaller boat (28’), and to buy a groundfish license. IF18 remained in the inshore fishery fishing for several groundfish and forage fish, although he stated that he makes far less money than when he was fishing lobster. When asked why he came back to work as crewmember and then fulltime for money. He said, “I told you I loved it.”

IF18’s story is indicative of a trade-off of material well-being for subjective well-being that informed a behavioral change. He used part of his retirement saving to come out of retirement and to re-enter for the ‘love of fishing.’ Although IF18’s story highlights a trade-off, IF18’s story does suggest that material well-being was not fully discounted, as IF18 had considerable savings from selling his enterprise. IF18s’ behavioral change highlights the importance of the social and economic situation. He was able to re-enter as a crew member first because of an opportunity posed by his friend. Then, IF18 had the financial security and skills to build his own boat and spend part of his savings on a groundfish license. In addition to the function of emotions as subjective well-being goals, emotions functioned as psychosocial factors to inform strategizing relating to adapting behavior changes.

Emotions as Psychosocial Factors in Strategizing for Adapting Behavior

We recorded how emotional valence and self-reported emotions factored into strategizing for adapting behaviors by shaping why IFs chose to pursue or not to pursue different forms of well-being. In all instances, perceptions of uncertainty played a mediating role when IFs indicated that emotions shaped their behaviors. Two patterns of emotional valence, self-reported emotions, perceptions of uncertainty and well-being were identified.

First, seven IFs associated adapting behavior change with hope, a self-reported emotion of positive valence. Those IFs associated hope with potential but uncertain opportunities in the fishery to advance their material, relational, or subjective well-being. Opportunities related to uncertainty about whether the fishery was going to have stronger catches or whether DFO was going to increase the quotas for the following year. Three IFs discussed how they entered or re-entered in the fishery because they were uncertain the future of their quotas for crab and hoped that DFO was going to reverse the trend of decreasing allocations. For example, IF13 discussed how the “fishery is really too unstable,” and that they re-entered with buying a new license because he “hopes that [DFO] figures [the quotas] out.” They hoped that quotas were going to be increased because of a limited availability of other work in their community, and they did not want to leave Newfoundland to make money with the cost of leaving their family. Four IFs indicated that they invested in the fishery by buying a new enterprise because they hoped for some positive change in the fishery to help them reach their goals. A quotation from IF19 explains how hope and uncertainty can turn out positively:

[F]ishing is a gamble. You are either going to do good or you mightn’t get any…. Right before you start fishing you have a good idea what you are going to end up with,. unless they for some reason… shut it down before you get your catch, but that don’t happen every year…[but in that circumstance] we just hoped and hoped that we were going to do something. We were hoping that we were going to get a bit of mackerel. There is always something that comes along. You don’t see it at the time when you are in the situation, but the road it seems like something always comes up.

In this quotation, IF19 connected the uncertainty of fishing as a type of ‘gamble’ where suboptimal conditions in the fishery can be reversed by catch increases of mackerel. For example, IF19 indicated that “a good price” can improve how fishing went the past year.

IF20’s comments provided another example of the role of hope and uncertainty. IF20 discussed how he bought a new vessel after years of making financially responsible decisions just to stay long-term in his community with his family. He had hoped cod would return. Several years later he realized that he made the wrong decision after “things started to go downhill.” However, he stated he makes a living sufficient to stay in the fishery until he physically can no longer fish:

I am going to stick with the fishery, but I am probably going to end up losing the boat…that I got because I ain’t got it paid for yet. So, I am going to stick with the small boat… The biggest season I got was [around $150,000] and that gotta be shared with five men. It’s not a big lot… if I make [a few hundred] dollars at the end of the week, oh boy that is good…The only bad part is that nobody put enough money away for a “rainy day” they calls [sic] it.

In addition to patterns of behavioral change associated with hope and uncertainty, a second pattern was recorded from 12 IFs in which fear drove the avoidance of adapting behavior, namely investing and exiting the fishery. In all instances, exiting the fishery or investing were associated with outmigration from local communities, including temporarily leaving their families or permanently uprooting their families. Investing was associated with debt, exiting the fishery and leaving their communities to find work outside of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Perceived certainty and uncertainty played different roles in strategizing. In each instance, IFs were certain that allocations were going to decrease or even close for respective fish stocks. IF1’s comment described this form of certainty, by indicating, “you never hear of anyone saying we are going to try to open up another area. All you hear is about is closures.” Uncertainty was associated with starting afresh in other provinces and cities more broadly. Respondents who perceived certain continual downturn of the fishery expressed how fear over exiting the fishery for an uncertain life elsewhere. For example, three IFs discussed fear associated with avoided the risks in investment. Those IFs stated that they did not know how to make a living any other way while perceiving that DFO was going to continue to decrease access and allocations. IF22’s demonstrated indicated that he had “nowhere to go, when you owe money like I do. I cannot do anything else. I put up with fishing up and down, but now it is not up and down: it is taken away.” Nine IFs indicated that fear shaped choices on whether to exit or not exit the fishery. Those IFs knew that fishery quotas were going to decline but were scared to move to another place that was unfamiliar to them. A quotation from IF5, the material well-being IF who lost her finger to fishing, talked about how fear of leaving the community for an uncertain future elsewhere shaped her decision to remain in the inshore fishery:

Where are we going to go? Unemployment is good though. No I cannot leave all together. My husband had to go away to work to Alberta, but when he came back he only had [a few thousand dollars]. So what was the point of that? [When I think about leaving], it is the familiarity mostly. I do not like city life, and it is basically it. I just do not like hustle and bustle of cities. It is the fear of the unknown.

This quotation demonstrates the power of perceived uncertainty and the role of fear in strategizing and subsequent behavior when IF5 states that the decision to remain in the fishery was shaped by “the fear of the unknown.” The fear was powerful enough that the family would remain in the fishery despite injury, lack of opportunity and dependence on employment insurance.

The 20 IFs who expressed the two patterns of emotional valence, self-reported emotions, well-being, and perceptions of uncertainty indicated that their strategizing included lengthy emotional discussions with household family members. Additionally, ten IFs who similarly indicated changes in adapting behaviors, in which emotions were an explanatory factor, indicated that these behaviors resulted from emotionally driven strategizing. Often strategizing extended across several fishing seasons and involved a negotiation of current outcomes, assets, and potential to advance well-being in the future. IF20, who ended up investing considerably, describes how he and his wife talked about how they considered exiting the fishery:

Once [the fishery was] pretty bad and me and the wife talked about it, “jeez” we are going to have to go away and go to Alberta or something, and I said, “I don’t know how life will go.” I said, “I tell you one thing. If I [expletive] go, I am not coming back once I am gone, and it will be pretty sad. We talked about it over and over.it was pretty emotional.”

Ultimately, IF20’s strategizing led to a hope-driven investment that turned out to be unexpectedly suboptimal. The stories of IFs who were driven by emotions as subjective well-being, and who expressed adapting behaviors for material and relational well-being did not come to those decisions lightly or dispassionately. The resultant behaviors influenced whether or not new capital and capacity remained within, increased, or left the inshore fishery.

Discussion

Insights about fisher behavior can strengthen the capacity to assess, address, and anticipate change in the core activities in marine governance, such as modeling, developing and implementing policy, and strategic planning (Fulton et al., 2011; Neilsen et al., 2017; Armitage et al., 2019). Emergent fisheries research about fishers’ behavior, and underlying explanations for this behavior, has indicated two opportunities to strengthen this evidence base: (1) to conduct research that better understands fisher behaviors over long periods of time; (2) to develop psychosocial evidence that explains fisher behavioral change. Our research addressed these gaps by examining fishers’ behaviors as livelihood pathways defined by the prioritization of certain forms of well-being associated with behaviors, and assessing changes to adapting behaviors for their psychosocial explanations by drawing on emotions research. Below we build evidence-based insights and lessons for fisheries science and governance to support, develop and implement policies under conditions of change that are sensitive to the local context.

Our findings provide theoretical and evidentiary lessons to enhance how scientists and policy-makers anticipate and address behavior in four ways. First, the categorization of livelihoods pathways shed new light on the livelihoods’ behavioral foundations and the importance of values, such as well-being, as goals for behavior (Coulthard, 2012; Weeratunge et al., 2014). The material wellbeing and relational pathways reflected patterns of adapting and coping behavior in response to change and uncertainty expressed toward the same values. Moreover, those patterns led to similar types of individual and household outcomes, with significant implications for capacity and capitalization in fisheries. For example, IFs who more often pursued material well-being experienced either a boom or bust in their lives. ‘Boom’ outcomes involved IFs experiencing considerable success, and that success was concomitant with new forms of capacity—larger vessels, more licenses, and more gear—into midshore shrimp and crab fisheries or remaining at the upper regulatory limits (i.e., biggest boats, higher allowable licenses) in the inshore fishery. ‘Bust’ outcomes resulted in suboptimal experiences in the fishery, including deprivations to physical and mental health and reliance on governmental assistance to sustain material well-being. IFs who pursued relational well-being more often stayed smaller by limiting their capacity and capitalization by making only one or two major investments in licenses or vessels, or by building their own boats. They, too, relied on employment insurance for governmental assistance but did so to prioritize their family life in local communities.

Behavior patterns associated with single values and patterned outcomes contributes to research on fishers behavioral diversity under conditions of change (e.g., Boonstra et al., 2017; Andrews et al., 2020; Wijermans et al., 2020). For example, Wijermans et al. (2020) highlight the importance of motivations, social interactions, abilities, and livelihoods to modeling fishing behavior (e.g., decision related to effort) in relation to ecosystem and policy change. Here, this research contributes additional categorizations for diversity with an emphasis on values as organizing patterns of behavior in both marine environments and coastal communities. Future research can investigate outcomes from different livelihood pathways by examining how adapting and coping behaviors enrich or detract from fishery livelihood dependence in communities. However, the categorizations did not fully explain all the behavioral changes discussed by the study’s IFs. Often, changes in adapting behavior were informed by trade-offs in forms of well-being along with changes in the economic, environmental, and social conditions in fisheries. In this research, however, behavioral events and their explanations were only tied to broad environmental, economic, and policy trends. More precise factors, such as fish stock biomass, habitat conditions, household debt, and trip costs over time have been determined to shape behavior over time. Moreover, emphasis on factors such as age, household financial status, gender and behavior, interpersonal relations, and social norms highlighted by other research can enhance future research (e.g., Daw et al., 2012; Pascoe et al., 2015; Harper et al., 2017).

Second, emotions’ evidence helped explain behavioral change, including changes associated with trade-offs involving well-being. Research results described how IFs often changed adapting behaviors to be based on strategizing that involved positive emotions such as relief and enjoyment. They avoided adapting behaviors such as investing for themselves and entry for their children out of emotions such as anger and frustration with fisheries downturns. Moreover, emotions associated with the economic conditions of the fishery drove some IFs to protest the policies of DFO and to sue their union. In addition to emotions as goals for fisher behavior, emotions functioned as explanatory factors that shaped IFs’ pursuit of well-being during strategizing on the water, in aggregating areas such as dockside, and in households. When emotions functioned as psychosocial factors, those emotions were strongly linked to the negotiation of uncertainty. IFs indicated that when they were uncertain of future allocations, they held out hope for advancing their material or relational well-being in the future. Notably, those IFs acted on hope when they re-entered or invested, injecting new capacity and capitalization in the fishery. Some IFs who remained in the fishery avoided exiting out of fear for the uncertainty associated with moving from Newfoundland and Labrador. Importantly, the negotiation of uncertainty happened over lengthy, emotionally laden discussions with family that confronted trade-offs among values (Van Kleef, 2016). Drawing on emotions was original (also Bender, 2002) and significant in combination with values and perspectives. Further, the examples contribute new evidence to an evolving understanding of how livelihood strategies lead to individual and household outcomes, and broader environmental and social changes, including those in governance (Nayak, 2017). To extend thinking on multi-scalar interactions related to behavior, future sociological and social psychological research is needed that more expressly relates fishers’ strategizing and its psychosocial attributes to social institutions. This will help research account for the sort of push and pull on behavior made by fishers’ agency or community structures, respectively (Coulthard, 2012).

Third, the research contributes to social-ecological systems assessments by revealing microlevel change processes and their potential implications for system dynamics related to both continuous change and system collapse (Fabinyi et al., 2014; Lade et al., 2015; Stojanovic et al., 2016). Our results revealed fishers’ behavioral patterns and their psychosocial explanations in those microlevel change processes. The results contributed novel evidence on how fishers interpret and negotiate of change and uncertainty, and how resultant behavioral patterns can help explain diverse groupings of responses. Consequently, these results contribute novel evidence to enrich social-ecological systems models and planning for adaptive capacity that accounts for social diversity and individual behavior needed to understand ‘action situations’ (Schlüter et al., 2019). Further, the research provides direction for deep qualitative descriptions into such assessments (Li et al., 2020).

Fourth, this research provides insights for coastal and marine fisheries governance under conditions of change and uncertainty. Governance can be strengthened with science, policy, and management interventions that can assess, address, and anticipate change and uncertainty in fisheries that, in turn, have environmental, economic, social, political, and governance dimensions (Nayak, 2017). Research has revealed that assumptions about human behavior and its motivations shape the underlying logic of how actors in governance expect a fishery to operate and respond to policy (Chuenpagdee and Jentoft, 2009). This research results provide a more nuanced understanding of rationality, in which fishers pursued, prioritized, and traded-off multiple goals and drew on emotions and perceptions as lenses to a range of economic, environmental, and governance changes. This depiction of change in inshore fisher behavior demonstrates the futility of anticipating that fishers are to behave in dispassionate ways to maximize their economic utility, as indicated by neoclassical economic and rational choice paradigms (Chuenpagdee and Jentoft, 2009; Fulton et al., 2011; Wijermans et al., 2020). Rather, this research highlights profit, or material well-being, as just one of several values that are negotiated, pursued, and prioritized across marine environments and coastal communities (Brueckner-Irwin et al., 2019).

Building context-sensitivity in fisheries policy reflects efforts to include knowledge on the local context in assessing change in fisheries, developing and implementing policy, and evaluating policies, such as through management strategy evaluation (Steelman and Wallace, 2001; Young et al., 2018; Lindkvist et al., 2020). Our findings further develop the psychosocial dimension of the local context (see also Béné et al., 2019). Findings on livelihood groupings provided long-term patterns of behavior in response to perceived changes provide complementary ways to organize fishers beyond common policy categories such as vessel size or allocation type. The IFs in this research ultimately self-organized according to their fishery-related goals. These goals informed how those fishers interacted with fish stocks, in coastal communities, and with managers in marine governance. As such, values reflect a necessary variable anticipating how fishers are likely to respond to policy change (Song et al., 2013; Wijermans et al., 2020). Results on the function of emotions, perceptions, and values in individual and group strategizing provides new and nuanced insights on how fishers prioritize and respond to change in local context. Further, the results provide opportunities for future research on the relationship between individual and group motivations for fisher behavior (Lindkvist et al., 2020), as the narratives in this research pointed to emotional decision-making related to adapting behaviors in households.