- 1Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States

- 2Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States

- 3National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO, United States

- 4Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States

- 5Geological Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

As the pressure to address the climate crisis builds, scientists must walk the line between research and activism. This was apparent at the 2019 United Nations (UN) Framework Convention on Climate Change – Conference of the Parties (UNFCCC – COP), the largest annual meeting to address the climate crisis via supranational policymaking. COP has convened annually since 1995 in effort to establish international agreements for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, and in 2015, was the launch pad for the UN Paris Climate Agreement (PCA). Here, we present our collective perspective as early-career researchers on COP, an institution that we believe plays a critical role in the future of our oceans. Given the current pledges from signatories to the PCA, Earth is expected to warm ∼3°C by 2100, with the majority of anthropogenic heat content stored throughout the ocean. For this reason, among others, we feel it is crucial for ocean scientists to have a baseline understanding of the negotiations unfolding at COP and within the UNFCCC. We also provide evidence that certain features/structures of COP formalize colonial hierarchies, marginalize certain groups, and threaten to perpetuate the drivers of the environmental crises we all face. Thus, we urge that the future of such gatherings include purposeful and self-reflective acts of restructuring the space they occupy, the solutions they advocate, and the ways in which power is distributed amongst participants. We balance our critique with examples of how this has already been successful at COP, particularly with respect to organizing around ocean-climate issues.

Introduction

Describing climate change as a “crisis” is not hyperbole (IPCC, 2014, 2018, 2019). In addition to higher mean temperatures, climate change means more frequent exposure to extreme weather events (IPCC, 2014, 2018); a greater likelihood of heatwaves, both terrestrial and marine (Frölicher and Laufkötter, 2018); desertification in some areas, inundation and drowning in others (Hirabayashi et al., 2013; Burrell et al., 2020). Climate change is likely to alter the form and function of nearly every system on Earth (IPCC, 2014, 2018), and it is imperative that all people collaborate to abate the emissions trapping excess heat in our atmosphere. For this reason, supranational dialog and consensus building such as that of the United Nations (UN) Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has a valuable role to play.

Convened in 1994, the UNFCCC aims to “prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with Earth’s climate system,”1 in coordination with other UN departments and affiliate agencies working to accomplish relevant climate and humanitarian goals (e.g., the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”). The UNFCCC holds an annual state-of-the-science and climate policy conference known colloquially as “COP” (i.e., the Conference of the Parties; est. 1995). At COP21 (Paris, France; 2015), the UN Paris Climate Agreement (PCA) was signed into international law (UNFCCC, 2015). The PCA is a multinational environmental treaty designed to limit anthropogenic warming to 2°C above the pre-industrial average through country-specific pledges to decarbonize known as “NDCs” (Nationally Determined Contributions). Countries are expected to re-up their NDCs at the next COP (COP26) in Glasgow, Scotland – which, as they are currently written, are likely to result in 2.9–3.4°C warming by 2100 (IPCC, 2018). The majority of anthropogenic heat content is or will be stored in the marine environment (IPCC, 2019), yet, it was not until Paris that negotiators with the UNFCCC began to substantively integrate the ocean into plans for climate action (Gallo et al., 2017). For these reasons, we feel it is critical for ocean scientists to have a baseline understanding of the negotiations currently unfolding at COP.

Since 2015, COP gatherings have largely focused on codifying the Paris Rulebook, which tells countries precisely how they should work together to respond to this existential threat. Major technical decisions are negotiated in advance by the UNFCCC’s Subsidiary Bodies (listed in Table 1) during intersessional and pre-COP meetings (which function much like COP but with fewer Observers). COP on the other hand is a highly visible forum for the final stages of negotiations, during which voting representatives from every one of the Framework’s 197 Parties must reach consensus to advance any particular outcome.

Table 1. Definitions and reference materials for (i) Acronyms, (ii) Participants, (iii) Key terms, (iv) Relevant texts and entities invoked throughout the text.

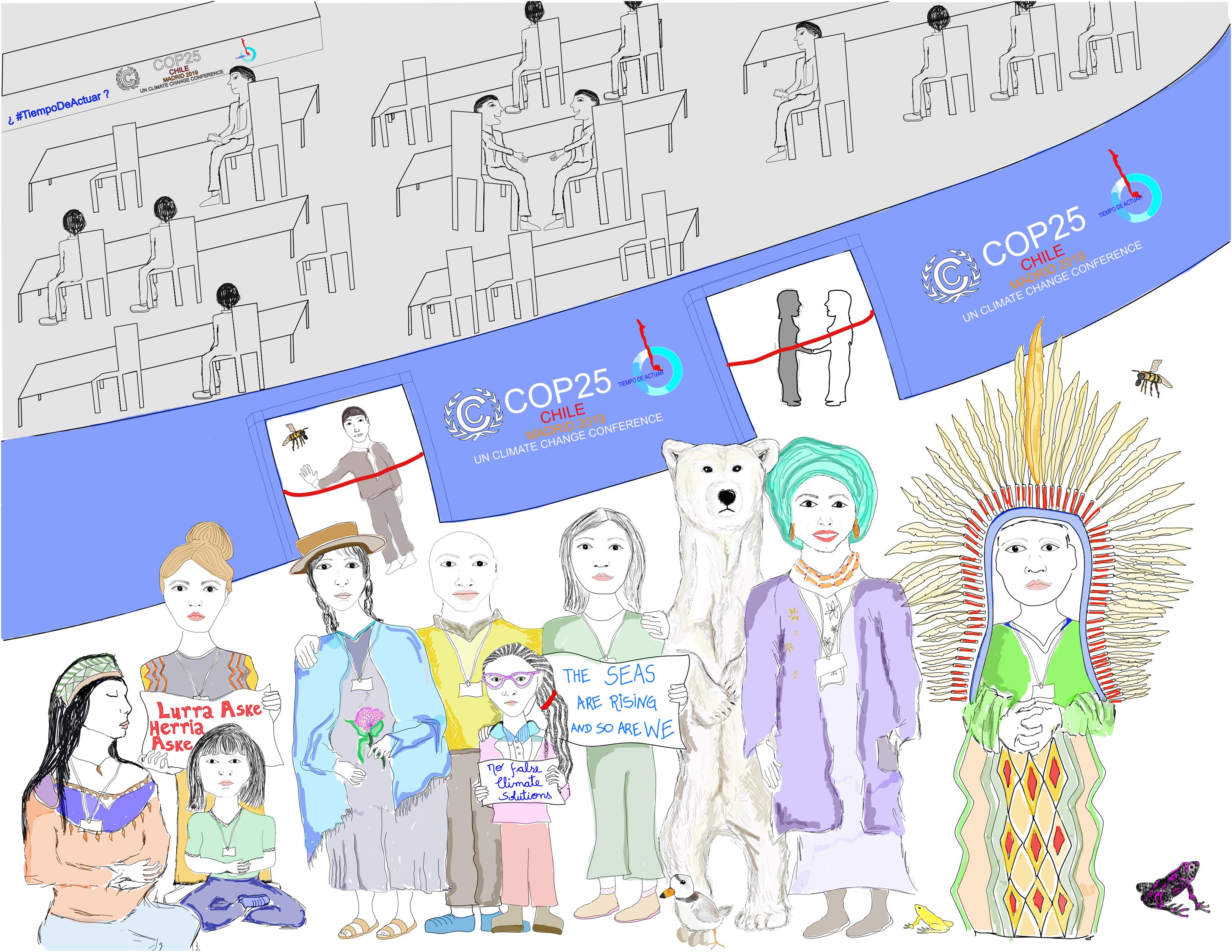

Six authors of this piece attended COP25 in Madrid, Spain (2019) as graduate student researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography with the University of California delegation. Many of us have additional experience from COPs 22 (Marrakesh, Morocco), 23 (Bonn, Germany), and 24 (Katowice, Poland). Our perspectives are informed by our professional experience and education in Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Science, framed by our own identities as individuals who are young, multi-ethnic, mostly women, graduate degree-holding, and multinational. We view the COP process as a critical vehicle for global dialog and emphatically support unified action to reduce harm associated with the climate crisis. However, as relative newcomers to the UNFCCC process, we’ve experienced a felt-disconnect between the strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions embraced within the formal COP negotiations and the more holistic, justice-centered approaches advocated for outside of those chambers (Goodman, 2019) (Figure 1). In an effort to lower the barriers to entering and understanding the COP process, we describe some of the lessons we’ve learned and present a list of key terms to help orient readers to the intricacies of the Conference itself and the Framework under which it’s come to be (Table 1).

Figure 1. The two realities of the Conference of Parties 25 (COP 25) inside the Baker Hall at Feria de Madrid, Spain. In the main plenary room, high-level negotiations/meetings are held. Outside, Observers gather to make their voices heard, including representatives from Indigenous communities, youth organizations, the Women and Gender Constituency among many others. COP participants frequently wear clothes or hold up signs that reflect their identity and core values. Animals are also depicted here since they are indirectly represented at COP by various observer organizations. Original artwork by author Leticia Cavole.

At COP we’ve witnessed two related issues which we view as obstacles to just international climate policy: the perpetuation of structural/institutional barriers to equitable inclusion of diverse constituents in decision-making; and a pronounced focus on market-based climate solutions, while largely skirting issues related to resource consumption. We explore these ideas in sections ““Setting the Stage” – Consensus of the Powerful” through “The Push for Representation at COP and Within the UNFCCC” of this article, while attempting to balance our critique with examples of COP actors working to solve many of the issues we’ve observed. In sections “The Push for Representation at COP and Within the UNFCCC” and “Power to the People Sees Direct Ocean ‘wins,”’ we highlight aspects of COP that we feel are worthy praise and outline how collective action and organizing have effectively paved the way for supranational ocean-climate action.

“Setting the Stage” – Consensus of the Powerful

Conference of the Parties itself is a massive enterprise, hosting tens of thousands of attendees in convention centers that stretch for multiple city blocks. Policymaking occurs in restricted-access areas of the convention hall between UN negotiators. An extensive, vibrant, Civil Society Zone is open to members of the press and representatives of observer organizations, which are entities that have been approved to attend (e.g., NGOs, IGOs, and industry representatives). Many of the observer organizations have self-organized around shared interests or perspectives to form cooperative constituency organizations. Nine constituencies are officially recognized by the UNFCCC (Table 1), including the Research and Independent NGOs constituency (RINGO) which hosted our participation.

The strength of COP is that, as an international body, it has a mandate to address transnational impacts of climate change mitigation and adaptation. Requiring consensus among PCA Parties enhances this positive characteristic, however, post-colonial political boundaries ensure that many communities remain politically disenfranchised when it comes to voting (e.g., Sealy-Higgins, 2017). For example, the de facto reliance on recognized nation states as Parties to the PCA is poorly aligned with the sentiments expressed in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (The United Nations General Assembly, 2007). Groups who have and continue to benefit most from the extraction and consumption of material goods (and high emissions) appear to have the greatest representation across negotiations, exacerbated by the fact that a country’s Party does not necessarily represent the interests of all its constituents/communities.

Despite the egalitarian objective of the UN to maintain international peace, we have observed that COP functions a bit like a microcosm of the world we live in, where the worldviews of some have been notoriously excluded or are systemically undervalued borne from intersecting forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, ageism, homophobia, transphobia, and religious discrimination among others (e.g., see Soumaré, 2021). Communities (and countries) that have been excluded from and/or explicitly targeted by dominant socioeconomic structures may have a seat at the table, but at this time, must use that platform to request alliance, compassion, and financial support for adaptation, loss and damages (e.g., Sealy-Higgins, 2017; see PCA Article 8). This highlights the distinction between equality and equity, and demonstrates why the equality offered by consensus may be insufficient to provoke meaningful change and reparations for climate damage already done.

Understanding How Proposed Climate “Solutions” May Perpetuate Crises

To achieve a “good life for all within planetary boundaries,” it is essential that we reduce the level of resources associated with a high standard of living (O’Neill et al., 2018). This includes a more equitable per capita consumption of resources (Giljum et al., 2009) as well as protections for communities and ecosystems that have been historically exploited. This knowledge permeates the negotiations at COP, however, it is not politically popular to discuss the fact that economic growth – while a primary need in many parts of the world (Rodríguez-Labajos et al., 2019; Hickel, 2020) – is counterbalanced by a need for “degrowth” (Table 1) in places where resource consumption is disproportionately high (Rodríguez-Labajos et al., 2019; Hickel, 2020). For reasons we suspect are related to the financial interests of a minority of wealthy/powerful people, lobbies, and Parties (who have no intention of advocating for decreased material consumption or “degrowth”), market-driven and technocratic solutions to climate change are heavily favored in COP negotiations overall (Bachram, 2004; Fernandes and Girard, 2011; Sealey-Huggins, 2017). We feel that it is important to contextualize these proposals and their actual potential to mitigate climate change.

Regarding market-driven solutions, the lynchpin of COP25 was in deciding the outcomes of specific subpoints in PCA – Article 6 (Table 1), dealing with the regulation of carbon-trading markets. These schemas (e.g., carbon offsets) are highly contentious, present a false substitute for decarbonization, and have been criticized as a modern-day extension of colonialism and imperialism (Bachram, 2004; Sealey-Huggins, 2017). Another utilization of “the market” within the UNFCCC that we find to be more appropriate is the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which is intended to redistribute monies from high-emission countries to low-emission countries that are least responsible for climate change but also highly vulnerable to its effects (Táíwò and Cibralic, 2020). While the GCF increasingly relies of private sector financial mechanisms and has, unfortunately, achieved < 10% of its 2020 $100 billion goal (Táíwò and Cibralic, 2020), we feel that the ideas behind the project, such as monetary redistribution and reparations, are worthy of full consideration at COP.

Under the umbrella of technocratic climate solutions is the push for a “green energy revolution.” This movement bears potential for deep decarbonization but is not without its own set of problems. Renewable energy technologies require the raw materials for batteries used in grid storage and electric vehicles, i.e., rare earths and other precious metals. In the span of just 10 years (2018–2028), demand for lithium-ion batteries is forecasted to grow seven-fold (Bibienne et al., 2020), with just a few “developed” countries driving ∼ 90% of the import-market in international trade (Sun et al., 2017). Similar to preceding generations of energy revolution, the current loci of extraction are often Indigenous or colonized lands (Estes, 2018; Whyte, 2020). Lithium is often sourced from the Andean highlands of South America, using a highly destructive process of extraction that threatens access to water and land among local and Indigenous communities. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, in Central Africa (mainly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo), people mine for the metallic supplements to lithium batteries (e.g., cobalt) (Banza Lubaba Nkulu et al., 2018). The byproducts of this extraction are toxic (e.g., uranium), jeopardizing the health and wellbeing of people who work in these oft-mismanaged mines as well as the function of local riparian/forest ecosystems (Banza Lubaba Nkulu et al., 2018).

While it may not be immediately obvious, the push for “green” energy is of particular relevance to those who study the ocean. Conflicts and environmental concerns around terrestrial mining may move exploration and exploitation for precious metals offshore via deep-seabed mining, where the impacts of human activity are not well understood and the regulations of mining yet to be defined (Levin et al., 2020). The ornate tapestry of life we’ve observed in the deep sea represents hundreds of years’ worth of development, and huge gaps in information plus challenges in data collection and monitoring exist for deep-sea and midwater environments (Drazen et al., 2020; Levin et al., 2020). This makes it difficult to establish an environmental baseline or to even understand what constitutes serious impacts to these ecosystems (Mengerink et al., 2000; Levin et al., 2016, 2020; Drazen et al., 2020).

Similar to terrestrial mining, seabed mining threatens “non-human” life as well as the communities of people whose culture and subsistence are dependent on healthy oceans (Levin et al., 2016, 2020). These were themes explored during COP25 at the Moana Blue Pacific Pavilion, sponsored by Fiji in combination with other Pacific Island nations. Without political measures to empower Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples (“LCIPs”), the market-driven extraction of metals for green-energy technologies, whether on or off shore, threatens to create populations of environmental refugees, migrating from homelands damaged in the name of climate “solutions” (Isenberg, 2010; Brito-Millan et al., 2019).

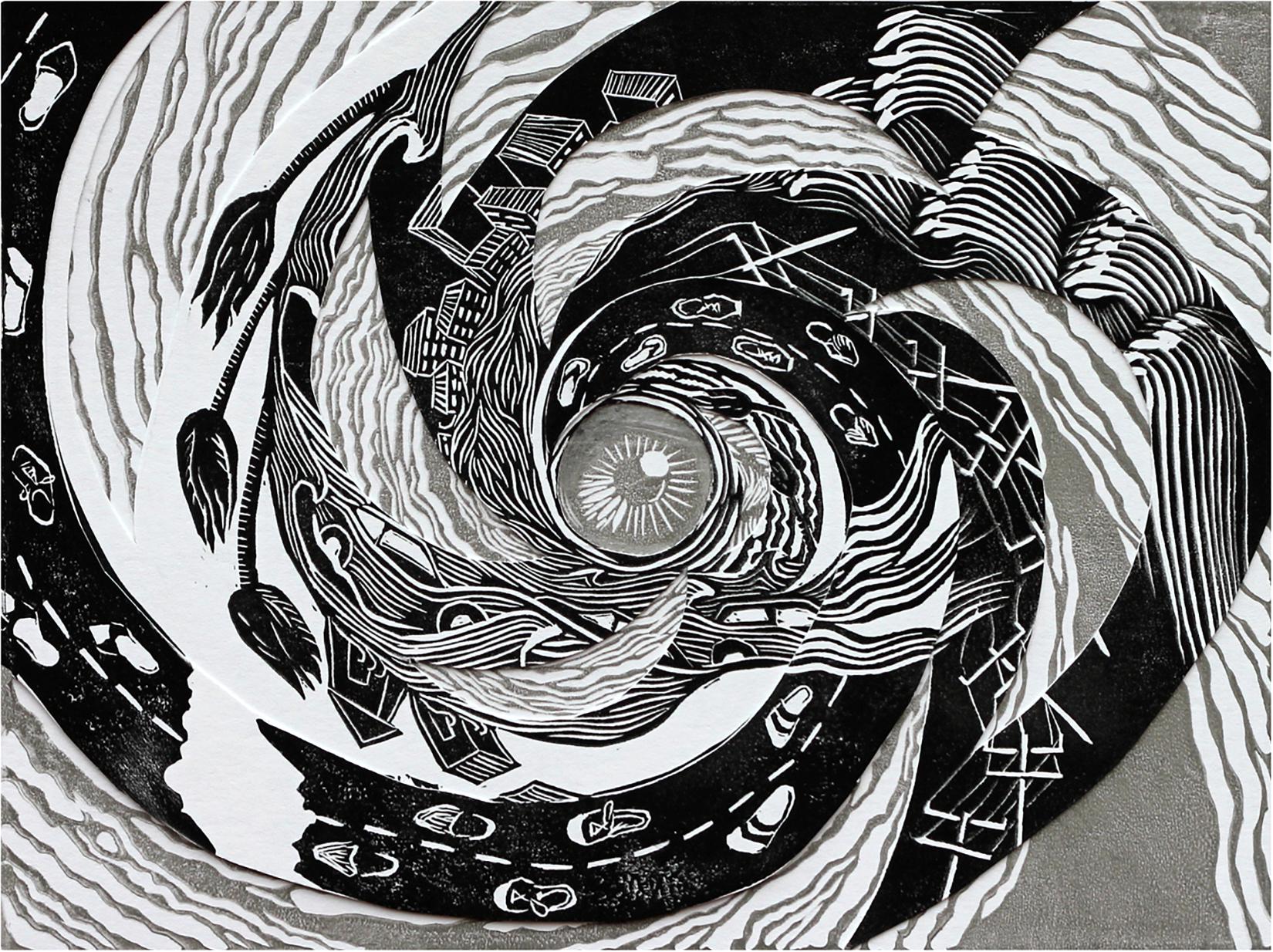

Resource extraction driven by the push to mitigate climate change is a territory-crosscutting vulnerability which threatens to perpetuate the environmental crises we face. Instead, we should work thoughtfully to address what we view as one of the root causes of climate change: rapid, inefficient, and highly inequitable consumption of resources (O’Neill et al., 2018; Hickel, 2020). As a “threat multiplier” (Huntjens and Nachbar, 2015), climate change will affect everyone, but for some, it’s a matter of home or homelessness, “a matter of life or death” (Head of State Hilda Heine of the Republic of Marshall Islands comm., September 2016) (Figure 2). To this end, climate “solutions” should be carefully considered and scrutinized based on their social and ecological impacts, including violations to sovereignty and health. We, as authors of this piece but also beneficiaries of tremendous privilege, feel united in a desire to sacrifice material excess and political hegemony for the health and longevity of the planet and each other. We assert that this trade-off is valid, not naive, and should be part of political climate negotiations at the largest scale.

Figure 2. Linocut by author Simona Clausnitzer that depicts the lived experience of hurricanes, in particular Hurricane María. The image can be interpreted literally, as a hurricane and its numerous impacts, or more symbolically: watching ourselves twist in a storm system of inequities that caused people living in Puerto Rico to be without power for as much as 328 days following María, largely due to a lack of support from the United States’ federal government. As severe weather events worsen in frequency and intensity, it is crucial to have meaningful justice-oriented climate legislation, much of which is being developed at COP.

The Push for Representation at COP and Within the UNFCCC

Despite an ongoing push to represent alternative perspectives within the UNFCCC, COP participants who do not conform to the zeitgeist of proposed climate solutions are frequently marginalized. At COP25, for example, 200 + Observers were temporarily banned from the convention center after staging a sit-in demonstration advocating increased attention to climate justice, and solutions beyond carbon markets (McGrath, 2019). This demonstration came on the heels of an earlier protest staged by the organization Fridays for Future (Table 1), where youth activists occupied the center stage of the negotiation chamber to demand climate justice in accordance with the IPCC’s Special Report on 1.5°C Warming (2018). No doubt, the organizers of these protests will continue to make their voices heard at COP26, and in our opinion, they are successfully altering the tone of climate negotiations.

During the final plenary of the convention, 2 min were allocated to the constituency group for Indigenous Peoples’ Organizations (IPOs). IPOs had pushed fruitlessly for negotiators to elaborate on the protection of human rights and Indigenous peoples’ rights within the PCA – Article 6, arguing that carbon market approaches directly harm Indigenous communities (Webb and Wentz, 2018). When the time came for the plenary, the President delivering the address attempted to omit their statement, asking instead that they upload it to the website due to a two-day delay in closing the negotiations. In contrast to this act and the history of Indigenous exclusion within the UNFCCC (Sherpa, 2019), negotiators formally constituted the Facilitative Working Group of the LCIP Platform (LCIPP) at COP25. The LCIPP is composed of 14 members: one Party representative from each of the UN’s five regional groups; one Party representative from a Small Island Developing State (SIDS); one Party representative from a “Least Developed Country” (LDC); and seven IPO representatives. The core functions of this working group are to: (1) protect and apply traditional knowledge, (2) build capacity for UNFCCC LCIP engagement, and (3) to facilitate strong climate change policy that respects LCIP rights.

Similar efforts to build political representation and power for other historically marginalized groups exist within the UNFCCC, including the Women and Gender Constituency. A UN Environmental Program report (2020) makes clear that climate change has gendered impacts on society, stemming from patriarchal social conditions under which women and girls have less control over resources, wealth, and power – and are exposed to disproportionately high levels of physical and sexual violence resulting from climate instability (Nellemann et al., 2012; UNDP, 2020). Yet, just one-third to two-fifths of UNFCCC leadership roles, Party, or subsidiary delegations, are occupied by women (Greene, 2019; UNFCCC WEDO, 2020). Furthermore, the intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) of gender discrimination with (for example) race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or disability may heighten vulnerabilities (Nellemann et al., 2012; Vinyeta et al., 2015; UNDP, 2020), especially among groups of people who do not see their experiences reflected by Party representatives.

The political outcomes of COP negotiations also have major impacts on Earth’s flora and fauna (IPBES, 2019; Duarte et al., 2020), but the PCA fails to operationalize their inherent rights to exist and thrive. Countries such as Bolivia have lobbied hard to codify these rights at COP (see PCA Introduction – item 13) and in parallel proceedings (e.g., The World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth, 2010); but it’s been difficult to garner political support for the “rights of nature” (see Republic of Ecuador, 2008) as a matter of international law. In this respect, the Rulebook does a poor job at honoring nature’s intrinsic value as well as the lives and cultural practices of people for whom human and “non-human” life is spiritually intertwined (McCauley, 2006; Whyte, 2020). It also undervalues the many impending climate consequences associated with mass extinction and biosphere collapse (Anderson-Teixeira et al., 2013; IPBES, 2019). Technically, the UN’s Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) is tasked with stemming the contemporaneous crisis of biodiversity loss, but their work is increasingly recognized as inextricably tied to UNFCCC negotiations. And, in a somewhat hopeful turn of events, the Presidency of COP26 will center “Nature” as one of its five “Presidential Campaigns.”

As we’ve described, the politics of climate change adaptation and mitigation have the potential to exploit and amplify pre-existing and intersecting social vulnerabilities. Moreover, a wide breadth of social-ecological knowledge/perspectives will be required to tackle the complex governance challenges and biogeochemical consequences associated with climate change (e.g., IPBES, 2019). For these reasons, equitable representation of historically marginalized groups is paramount in political arenas such as COP, and we propose that the pre-existing infrastructure for official constituencies be leveraged to enfranchise communities that are not well-represented by Parties.

Constituency groups already have enhanced representative power at COP, including access to the Floor in the form of interventions and facilitated exchange with the UNFCCC Secretariat. Their current status as “non-party organizations,” however, means that they cannot vote on nor veto official Rulebook language. Constituencies do not represent a single country or territory, rather, they encompass politically cross-cutting groups with common interests, perspectives, and struggles. Thus, developing mechanisms to give constituencies official Party status could bring voting representation for explicitly marginalized groups into the negotiation chambers with enhanced power to advocate for the communities they represent.

We recognize, however, that representation (even within leadership positions) may be insufficient to counteract foundational legacies of exclusion; that formal representation is often met with pressure to conform; and that negotiators are people, and no one person can “fix” everything. Thus, without systemic accountability practices, the dominant culture may continue to control chambers of power. Additional mechanisms/metrics should be developed to track progress toward meaningful inclusion of diverse perspectives and to promote organizational practices that counteract the long-held influence of power, money, and political hegemony. We contend that these mechanisms must address the multifaceted effects of hierarchy by ensuring inclusion and actively combating prejudice (e.g., practicing anti-racism) within the organization.

Power to the People Sees Direct Ocean “Wins”

Culminating at COP25, we’ve seen how the political organization of communities from historically marginalized groups can fundamentally change the outcome of negotiations, whereby Fiji and its many allies through the “Friends of the Ocean” coalition (Table 1) secured attention for ocean-climate action in future UNFCCC negotiations. Specifically, the coalition laid the groundwork for future SBSTA discussions related to ocean-climate action and ocean-based solutions (Decision 1/CP.25)2. This represents an important step because, until COP21, the ocean had been largely excluded from negotiations altogether; this oversight is at odds with the incredible role that the ocean plays in regulating Earth’s climate as well as the numerous manifestations of climate change in the marine environment (IPCC, 2019).

In the COPs following COP23 (spearheaded by Fiji), we noticed increases in Indigenous representation and a concerted focus on the ocean-climate nexus. We also observed an increase in both the span and depth of conversations centered on SIDS, the unequal effects of climate change, and the key role that local and Indigenous knowledge/leadership plays in successfully implementing the PCA. This gave way to the ideas behind the LCIPP Facilitative Working Group, and beginning in January 2018, Parties adopted a new facilitative dialog publicly introduced by COP23’s President and Fijian Prime Minister (Frank Bainimarama).

This traditional dialog, known as the Talanoa dialog, is a solutions-oriented style of decision-making which places emphasis on collective action. It involves storytelling and skill-sharing to build trust and improve negotiations through empathy (Informal Note by COP Presidencies). We support Parties fully integrating and convening through the Talanoa or similar dialogs, emphasizing inclusivity and transparency to enact decisions both for and by all. Moreover, leadership emanating from LCIPs, SIDs, and Pacific Islander communities on issues related to the ocean exemplifies why alternate epistemologies must be integrated into UNFCCC negotiations.

Conclusion

Despite the sheer magnitude of the climate crisis, we believe that a better world is possible, and that purposeful restructuring of the UNFCCC/COP process will aid in our shared goal to abate emissions and overcome the negative effects of warming. We have seen how increased representation from diverse constituents and delegations at COP has successfully shifted the narrative on climate change, generating increased attention to intersectional climate justice as well as political interest in our coasts, islands, and oceans. In writing this piece, we directly address our fellow early-career researchers who find themselves driven to push for climate action beyond their role in science, and hope that our experiences motivate an increased attention to the global climate negotiations that will undoubtedly shape the future of our lives and the oceans we love.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

EH conceived the initial idea for this manuscript and EMF organized its execution. DFD, EMF, EH, RS, and TCO worked to develop the original content for the manuscript. EMF and EH contributed the first drafts of the manuscript. LMC, SC, DFD, EMF, EH, TCO, and RS helped to contribute with the subsequent framing, writing, and revisions. EMF, EH, and SC served as the main editors for the manuscript. LMC, DFD, TCO, and EMF prepared the table. LMC and SC contributed to the original artwork to this manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the organizers of the University of California delegation to COP, and in particular Robert Monroe, for the opportunity to attend the conference. We would also like to thank Margaret Leinen, Lisa Levin, Robert Monroe, two reviewers, and the handling editor of this manuscript, all of whom provided very helpful feedback and critique on this manuscript. Finally, we give thanks to our many friends and colleagues who have helped inform our understanding of COP and climate issues over time.

Footnotes

References

Anderson-Teixeira, K. J., Miller, A. D., Mohan, J. E., Hudiburg, T. W., Duval, B. D., and DeLucia, E. H. (2013). Altered dynamics of forest recovery under a changing climate. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 2001–2021. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12194

Bachram, H. (2004). Climate fraud and carbon colonialism: the new trade in greenhouse gases. Capitalism Nat. Socialism 15, 5–20. doi: 10.1080/1045575042000287299

Banza Lubaba Nkulu, C., Casas, L., Haufroid, V., De Putter, T., Saenen, N. D., Kayembe-Kitenge, T., et al. (2018). Sustainability of artisanal mining of cobalt in DR Congo. Nat. Sustain. 1, 495–504. doi: 10.1038/s41893-018-0139-4

Bibienne, T., Magnan, J.-F., Rupp, A., and Laroche, N. (2020). From mine to mind and mobiles: society’s increasing dependence on Lithium. Elements 16, 265–270. doi: 10.2138/gselements.16.4.265

Brito-Millan, M., Cheng, A., Harrison, E. J., Mendoza Martinez, M., Sugla, R., Belmonte, M., et al. (2019). No comemos baterias: solidarity sciene against false climate change solutions. Sci. People 22. https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/vol22-1/agua-es-vida-solidarity-science-against-false-climate-change-solutions/ [Epub ahead of print].

Burrell, A. L., Evans, J. P., and De Kauwe, M. G. (2020). Anthropogenic climate change has driven over 5 million km2 of drylands towards desertification. Nat. Commun. 11:3853. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17710-7

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Normative Discrimination and the Motherhood Penalty, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Legal Forum, 8.

Drazen, J. C., Smith, C. R., Gjerde, K. M., Haddock, S. H. D., Carter, G. S., Anela Choy, C., et al. (2020). Midwater ecosystems must be considered when evaluating environmental risks of deep-sea mining. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 17455–17460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2011914117

Duarte, C. M., Agusti, S., Barbier, E., Britten, G. L., Castilla, J. C., Gattuso, J. P., et al. (2020). Rebuilding marine life. Nature 580, 39–51. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2146-7

Estes, N. (2018). Our History is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance. New York, NY: Verso, 133–167.

Fernandes, S., and Girard, R. (2011). Corporations, Climate and the United Nations How Big Business has Seized Control of Global Climate Negotiations. Available online at: https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/polarisinstitute/pages/31/attachments/original/1411065499/CorporationsClimateandtheUN.pdf?1411065499 (accessed November, 2020).

Frölicher, T. L., and Laufkötter, C. (2018). Emerging risks from marine heat waves. Nat. Commun. 9:650. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03163-6

Gallo, N., Victor, D., and Levin, L. (2017). Ocean commitments under the paris agreement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 833–838. doi: 10.1038/nclimate3422

Giljum, S., Hinterberger, F., Bruckner, M., Burger, E., Frühmann, J., Lutter, S., et al. (2009). Overconsumption? Our Use of the World’s Natural Resources. Brussels: Friends of the Earth Europe.

Goodman, A. (2019). COP25: Alternative Climate Summit Honors Those “Suffering the Crimes of Transnational Corporations. Democracy Now! December 6.

Greene, S. (2019). What Do the Statistics on UNFCCC Women’s Participation Tell Us?. New York, NY: Women’s Environment & Development Organization.

Hickel, J. (2020). What does degrowth mean? A few points of clarification. Globalizations 1–7. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2020.1812222

Hirabayashi, Y., Mahendran, R., Koirala, S., Konoshima, L., Yamazaki, D., Watanabe, S., et al. (2013). Global flood risk under climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 816–821. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1911

Huntjens, P., and Nachbar, K. (2015). Climate Change as a Threat Multiplier for Human Disaster and Conflict. Available online at: https://www.thehagueinstituteforglobaljustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/working-Paper-9-climate-change-threat-multiplier.pdf (accessed November, 2020).

IPBES (2019). “Intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services,” in Summary for Policy Makers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, eds E. S. Brondizio, J. Settele, S. Díaz, and H. T. Ngo (Bonn: IPBES).

IPCC (2014). IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the 5th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Geneva: IPCC, doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511976988.002

IPCC (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways in the Context Of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Cli, eds V. Masson-Delmotte, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, et al. (Geneva: IPCC).

IPCC (2019). in Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, eds H. O. Portner, D. C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, et al. (Geneva: IPCC).

Levin, L. A., Amon, D. J., and Lily, H. (2020). Challenges to the sustainability of deep-seabed mining. Nat. Sustain. 3, 784–794. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-0558-x

Levin, L. A., Mengerink, K., Gjerde, K. M., Rowden, A. A., Van, C. L., Clark, M. R., et al. (2016). Defining “serious harm” to the marine environment in the context of deep-seabed mining. Mar. Policy 74, 245–259. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.09.032

Mengerink, K. J., Dover, C. L., Van Ardron, J., Baker, M., Escobar-briones, E., et al. (2000). A call for deep-ocean stewardship. Science 344. 696–698.

Nellemann, C., Verma, R., and Hislop, L. (2012). Women at the Frontline of Climate Change: Gender Risks and Hopes, a Rapid Response Assessment. Arendal: United Nations Environment Programme.

O’Neill, D. W., Fanning, A. L., Lamb, W. F., and Steinberger, J. K. (2018). A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 1, 88–95. doi: 10.1038/s41893-018-0021-4

Republic of Ecuador (2008). Constitution of 2008 (English Translation). Available online at:https://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Ecuador/english08.html (accessed March, 2021).

Rodríguez-Labajos, B., Yánez, I., Bond, P., Greyl, L., Munguti, S., Ojo, G. U., et al. (2019). Not so natural an alliance? Degrowth and environmental justice movements in the global south. Ecol. Econ. 157, 175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.11.007

Sealey-Huggins, L. (2017). ‘1.5°C to stay alive’: climate change, imperialism and justice for the Caribbean. Third World Q. 38, 2444–2463. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2017.1368013

Sherpa, P. D. (2019). The Historical Journey of Indigenous Peoples in Climate Change Negotiation. Gland: IUCN.

Soumaré, M. (2021). Racism at the UN: internal audit reveals deep-rooted problems. Afr. Rep. https://www.theafricareport.com/62757/racism-at-the-un-internal-audit-reveals-deep-rooted-problems/ [Epub ahead of print].

Sun, X., Hao, H., Zhao, F., and Liu, Z. (2017). Tracing global lithium flow: a trade-linked material flow analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 124, 50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.04.012

Táíwò, O. O., and Cibralic, B. (2020). The Case for Climate Reparations. Washington, DC: Foreign Policy.

The United Nations General Assembly (2007). Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. New York, NY: The United Nations General Assembly.

UNDP (2020). Gender, Climate & Security: Sustaining Inclusive Peace on the Frontlines of Climate Change. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme, 49.

UNFCCC (2015). Paris Climate Agreement. Available online at: https://undocs.org/en/FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1 (accessed November, 2020).

UNFCCC WEDO (2020). Report: Women’s Participation in the UNFCCC. Available online at: https://wedo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Factsheet-UNFCCC-Progress-Achieving-Gender-Balance-2019.pdf (accessed November, 2020).

Vinyeta, K., Whyte, K. P., and Lynn, K. (2015). Climate Change through an Intersectional Lens: Gendered Vulnerability and Resilience in Indigenous Communities in the United States. USFS General Technical Report PNW-GTR-923, Boise, ID: USFS.

Webb, R., and Wentz, J. (2018). Human rights and article 6 of the paris agreement: ensuring adequate protection of human rights in the SDM and ITMO Frameworks. SSRN Electronic J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3180159

Keywords: conservation, climate change, United Nations, climate justice, climate policy, ocean-climate action

Citation: Ferrer EM, Cavole LM, Clausnitzer S, Dias DF, Osborne TC, Sugla R and Harrison E (2021) Entering Negotiations: Early-Career Perspectives on the UN Conference of Parties and the Unfolding Climate Crisis. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:632874. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.632874

Received: 24 November 2020; Accepted: 09 April 2021;

Published: 11 May 2021.

Edited by:

André Frainer, Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, NorwayReviewed by:

Louise Carin Gammage, University of Cape Town, South AfricaChloe Lucas, University of Tasmania, Australia

Copyright © 2021 Ferrer, Cavole, Clausnitzer, Dias, Osborne, Sugla and Harrison. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Erica M. Ferrer, ZW1mZXJyZXJAdWNzZC5lZHU=

Erica M. Ferrer

Erica M. Ferrer Leticia M. Cavole1

Leticia M. Cavole1 Simona Clausnitzer

Simona Clausnitzer Daniela F. Dias

Daniela F. Dias Rishi Sugla

Rishi Sugla Emma Harrison

Emma Harrison