94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci., 15 April 2020

Sec. Marine Biogeochemistry

Volume 7 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00206

Methane transport from subsurface reservoirs to shallow marine sediment is characterized by unique biogeochemical interactions significant for ocean chemistry. Sulfate-Methane Transition Zone (SMTZ) is an important diagenetic front in the sediment column that quantitatively consumes the diffusive methane fluxes from deep methanogenic sources toward shallow marine sediments via sulfate-driven anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM). Recent global compilation from diffusion-controlled marine settings suggests methane from below and sulfate from above fluxing into the SMTZ at an estimated rate of 3.8 and 5.3 Tmol year–1, respectively, and wider estimate for methane flux ranges from 1 to 19 Tmol year–1. AOM converts the methane carbon to dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) at the SMTZ. Organoclastic sulfate reduction (OSR) and deep-DIC fluxes from methanogenic zones contribute additional DIC to the shallow sediments. Here, we provide a quantification of 8.7 Tmol year–1 DIC entering the methane-charged shallow sediments due to AOM, OSR, and the deep-DIC flux (range 6.4–10.2 Tmol year–1). Of this total DIC pool, an estimated 6.5 Tmol year–1 flows toward the water column (range: 3.2–9.2 Tmol year–1), and 1.7 Tmol year–1 enters the authigenic carbonate phases (range: 0.6–3.6 Tmol year–1). This summary highlights that carbonate authigenesis in settings dominated by diffusive methane fluxes is a significant component of marine carbon burial, comparable to ∼15% of carbonate accumulation on continental shelves and in the abyssal ocean, respectively. Further, the DIC outflux through the SMTZ is comparable to ∼20% of global riverine DIC flux to oceans. This DIC outflux will contribute alkalinity or CO2 in different proportions to the water column, depending on the rates of authigenic carbonate precipitation and sulfide oxidation and will significantly impact ocean chemistry and potentially atmospheric CO2. Settings with substantial carbonate precipitation and sulfide oxidation at present are contributing CO2 and thus to ocean acidification. Our synthesis emphasizes the importance of SMTZ as not only a methane sink but also an important diagenetic front for global DIC cycling. We further underscore the need to incorporate a DIC pump in methane-charged shallow marine sediments to models for coastal and geologic carbon cycling.

Methane (CH4) is an important greenhouse gas with a significant role in the geological evolution of Earth’s carbon cycle and ongoing climate change. Compared to carbon dioxide (CO2), methane has ∼28 times higher warming potential (Stocker et al., 2014), and marine methane reservoirs constitute a large exchangeable carbon pool in the Earth’s shallow subsurface, which is significant for carbon cycle dynamics (Kvenvolden, 2002). Continental margins are characterized by methane flux sites that involve transfer in dissolved and gaseous forms via diffusion and advection from subsurface reservoirs to the seafloor. Methane transport toward the seafloor creates a characteristic chemosynthetic ecosystem based on benthic microbial interactions and highly interconnected carbon cycling coupled with other elements such as sulfur, iron, calcium, and trace metals (Suess, 2010). They are thus sites of unique geosphere-biosphere coupling that plays a significant role in the chemical and biological composition of the oceans, as well as the global carbon cycle (Judd and Hovland, 2009; Boetius and Wenzhöfer, 2013; Levin et al., 2016; Suess, 2018).

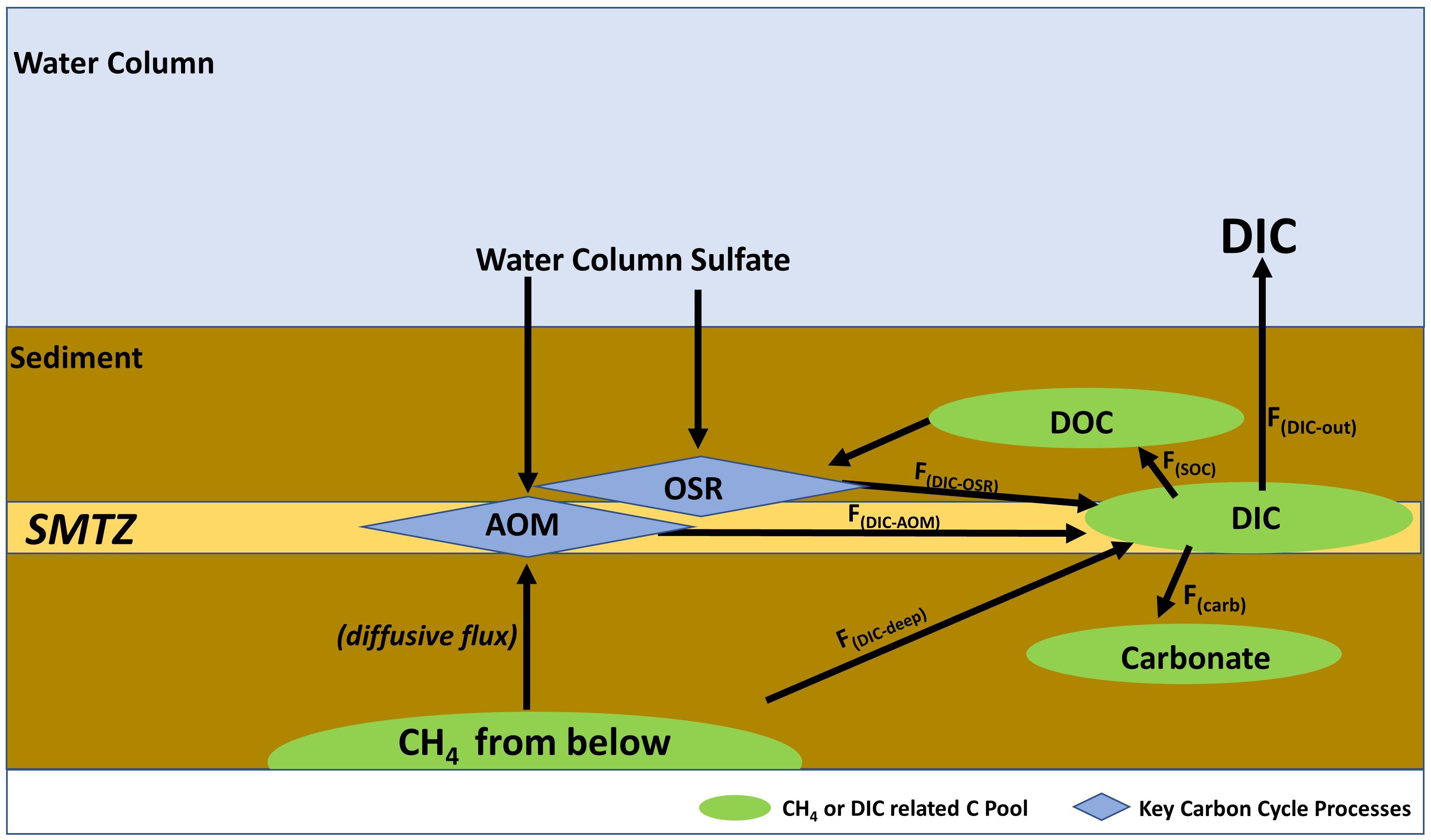

Some abrupt climate change events in paleoclimate records are potentially linked to massive dissociation of subsurface methane reservoirs into the oceans and atmosphere (e.g., Dickens et al., 1995; Hesselbo et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 2003). On the contemporaneous Earth, marine methane fluxes are effectively prevented from entering the atmosphere by microbial interactions in shallow sediments and water columns (Boetius and Wenzhöfer, 2013; Ruppel and Kessler, 2017). These processes convert methane carbon to inorganic and organic carbon pool (Figure 1) and prevent the direct impact of methane on the climate system (Reeburgh, 2007). However, the fate of this methane-derived carbon pool is overlooked and could be relevant to oceanic carbon cycling (Dickens, 2003; Coffin et al., 2014; Aleksandra and Katarzyna, 2018). Here we quantify methane-derived carbon cycling in shallow marine sediments in settings characterized by diffusive methane fluxes. We do this by assessing the transformation of methane carbon to inorganic and organic carbon pools (Figure 1) with the goal to assess its contribution to global oceanic carbon budgets. We emphasize settings dominated by diffusive rather than advective methane transport because of relatively well-constrained porewater data availability for global diffusive fluxes of methane and sulfate.

Figure 1. A simplified representation of DIC cycling at diffusion-controlled marine settings. Figure 4 provides DIC flux estimates. Refer to section “Calculations” for descriptions of flux parameters.

Sulfate-methane transition zone (SMTZ) is an important diagenetic front where the upward flux of methane encounters downward diffusive sulfate flux and undergoes sulfate-driven anaerobic methane oxidation (AOM) (Reeburgh, 1976; Borowski et al., 1996; Malinverno and Pohlman, 2011). During AOM, both methane and sulfate are consumed, and hydrogen sulfide (as HS–) and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) present mostly as bicarbonate (HCO3–) are produced (Boetius et al., 2000; Orphan et al., 2001). The net reaction can be expressed as:

Anaerobic methane oxidation in shallow sediment effectively consumes the methane diffusion in marine sediments (Reeburgh, 2007; Knittel and Boetius, 2009). A recent compilation by Egger et al. (2018) from 740 sites of wide oceanographic settings suggests that 2.8–3.8 Tmol CH4 undergoes sulfate-driven AOM annually. This range was higher than the average ∼1 Tmol CH4 year–1 proposed by Wallmann et al. (2012), closer to 3–5.2 Tmol CH4 year–1 estimated by Henrichs and Reeburgh (1987), and much lower than the estimated 19 Tmol CH4 year–1 by Hinrichs and Boetius (2002).

Here we highlight that SMTZ is not only important as a methane sink but also for DIC cycling in methane-charged shallow sediments. We do this by quantifying the sources and sinks of DIC cycling associated with the SMTZ at diffusive flux settings (Figure 1).

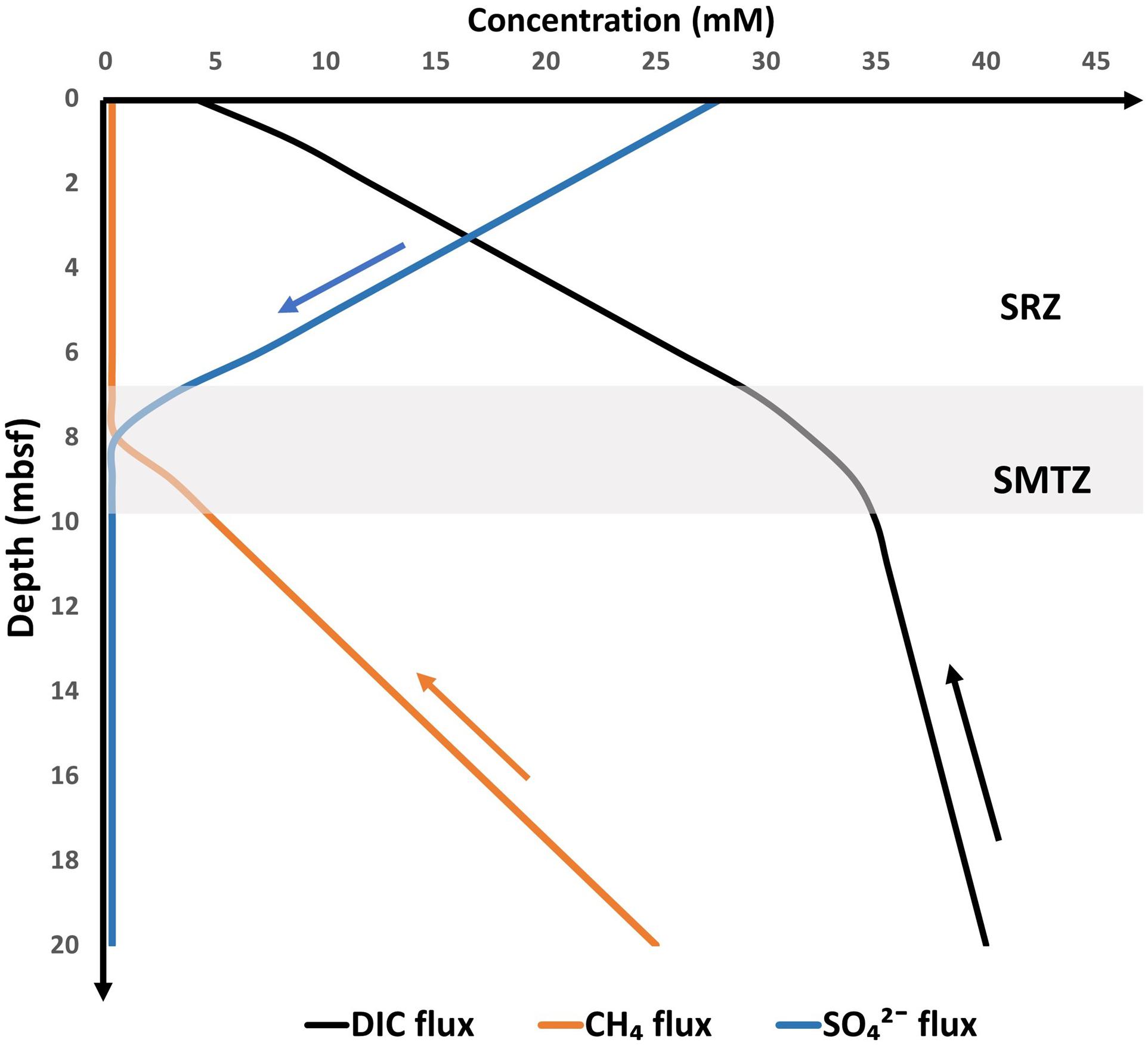

The SMTZ often contains higher DIC concentrations that can be accounted for AOM (Figure 2). Organoclastic sulfate reduction (OSR, Eq. 2) and deep-DIC flux from methanogenic zones are the primary sources of this excess DIC (Chatterjee et al., 2011).

Figure 2. Schematic concentration (based on measured and modeled) profiles for CH4, SO42–, and DIC, at diffusive methane flux setting. Arrows indicate flux direction. SRZ indicates the sulfate reduction zone with dominant organoclastic sulfate reduction (OSR). The DIC concentration at the SMTZ is the result of AOM, OSR, deep-DIC input, and authigenic carbonate precipitation. Modified based on data from Snyder et al. (2007, Japan Sea), Malinverno and Pohlman (2011, IODP Site U1325, Cascadia Margin), Chatterjee et al. (2011, ODP Site 1244, Hydrate Ridge), and Wehrmann et al. (2011, IODP Site 1345, Bering Sea).

The SMTZ depth is largely controlled by the upward flux of methane (Borowski et al., 1996) as well as the rate of organic matter degradation, which then controls rates of OSR and methanogenesis (Meister et al., 2013). In diffusive settings, OSR and AOM consume the sulfate at the SMTZ supported by organic matter buried into the SMTZ as well as dissolved organic carbon (DOC) that is produced below the SMTZ and migrates upward (Berelson et al., 2005; Komada et al., 2016; Jørgensen et al., 2019a). An estimated 11–80 Tmol year–1 of SO42– is reduced globally in marine sediments (Jørgensen and Kasten, 2006; Thullner et al., 2009; Bowles et al., 2014). Egger et al. (2018) suggested that 5.3 Tmol year–1 of this global marine SO42– reduction occurs at sites where methane transport occurs through diffusion.

A global estimate for methane and sulfate fluxing to the SMTZ in diffusive settings yielded an average ratio (CH4:SO42–) of 1:1.4 (Egger et al., 2018). A combined effect of AOM and OSR (Berelson et al., 2005; Kastner et al., 2008; Komada et al., 2016; Jørgensen et al., 2019b), as well as cryptic C-S cycling within SMTZ (due to concurrent production and consumption of methane), have been suggested to be causing this higher sulfate flux relative to methane flux (Borowski et al., 1997; Hong et al., 2013, 2014; Beulig et al., 2019).

In addition to AOM and OSR, deep-DIC fluxing from methanogenic depths provides another important source for DIC through the SMTZ (Dickens and Snyder, 2009; Solomon et al., 2014). Methanogenesis in deeper sediment can produce DIC in the form of CO2 which can be summarized as Eq. 3 (Meister et al., 2019b):

This CO2 would dissociate to HCO3– and H+, causing a pH decrease. This step, in turn, would favor weathering of silicate minerals in marine sediments (Marine Silicate Weathering-MSiW), resulting in alkalinity production and pH buffering (Aloisi et al., 2004; Wallmann et al., 2008; Solomon et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2016; Wehrmann et al., 2016, Eq. 4).

As a result of MSiW, methanogenic DIC enters the SMTZ as alkalinity instead of CO2 (Wallmann et al., 2008). Additional deep-DIC could enter the methanogenic zone and shallow sediments due to fluid expulsion from greater depths [e.g., continental crust alteration (Meister et al., 2011)].

Fate of the DIC pool entering the SMTZ primarily involves precipitation as authigenic carbonate minerals, autotrophic microbial consumption, and transport toward the water column. AOM, OSR, and deep-DIC flux will increase the DIC concentration and carbonate alkalinity of pore fluids at SMTZ (Chatterjee et al., 2011; Yoshinaga et al., 2014). Higher carbonate alkalinity, in turn, will stimulate authigenic carbonate precipitation at SMTZ (Aloisi et al., 2002; Orphan et al., 2004; Naehr et al., 2007; Feng et al., 2010; Crémière et al., 2012; Prouty et al., 2016) via the following reaction (Baker and Burns, 1985):

A small portion of total DIC from SMTZ will be assimilated into biomass by autotrophic microbes and eventually become part of sedimentary organic carbon (SOC; Sivan et al., 2007; Ussler and Paull, 2008). The remaining DIC enters overlying sediment and eventually the water column if it is not involved in diagenesis on the way.

The flux of DIC to the water column from methane charged sediments F(DIC–out), can be represented by Eqs 6 and 7, respectively.

As discussed below, Total(DIC) represents the ratio of DIC from AOM, OSR, and deep flux to methane entering the SMTZ. F(DIC–AOM), F(DIC–OSR), and F(DIC–deep) represent the DIC input to Total(DIC) via AOM, OSR, and deep flux, respectively. F(DIC–OSR) considers the depth-integrated DIC pool via OSR, which includes the SMTZ and sulfate reduction zone (SRZ) above. F(Carb), F(SOC), and F(DIC–out) represent the DIC output from Total(DIC) via authigenic carbonate precipitation, microbial uptake to SOC, and DIC outflux toward the water column, respectively (Figure 1). Net DIC fluxes from the sediment in methane-charged shallow sediments depend on the rates of these parameters. We would also like to mention that DIC cycling in shallow marine sediments, in general, can be influenced by processes not directly related to methane cycling like carbonate dissolution, organic matter degradation using electron acceptors other than sulfate, as well as submarine groundwater discharge (e.g., Berelson et al., 2007; Higgins et al., 2009; Moore, 2010; Hu and Cai, 2011; Aleksandra and Katarzyna, 2018). However, we focus our attention on diffusive methane charged settings and hence to the parameters in Eqs 6 and 7 for our DIC calculations, with an emphasis on their importance in marine DIC budgets.

Modeling studies have shown that the methane flux at fluid advection rates of up to 60 cm year–1 is almost completely consumed within shallow sediments (Luff and Wallmann, 2003; Luff et al., 2004), primarily via AOM. Hence, AOM efficiency would be lower in advective settings and higher in diffusive settings. As we focus on diffusive settings in this study, a 100% AOM efficiency is used for our budget calculation. Thus, for a 1:1.4 ratio of CH4:SO42– fluxing toward the SMTZ as a global average in diffusive settings (Egger et al., 2018), AOM accounts for 1 mol (70%) and OSR accounts for 0.4 mol (30%) of total SO42– consumption.

Deep-DIC flux to the SMTZ is prevalent in diffusive methane flux settings (e.g., Aloisi et al., 2004; Wallmann et al., 2008; Dickens and Snyder, 2009; Chatterjee et al., 2011; Scholz et al., 2013; Solomon et al., 2014). However, the global trend of this deep-DIC flux is not well established. If methane from deep below is biogenic, F(DIC–deep) should be 100% of the CH4 flux. As a result of MSiW, methanogenic DIC contributes as alkalinity, and silicate-bond cations are released (Wallmann et al., 2008; Solomon et al., 2014; Pierre et al., 2016), resulting in deep-DIC sequestration via carbonate precipitation within methanogenic zones (Torres et al., 2020). Additional deep-DIC sinks coupled to Fe/Mn reduction in the methanogenic zones was proposed by Solomon et al. (2014) and available literature reports also show a lower deep-DIC flux rate (Dickens and Snyder, 2009; Chatterjee et al., 2011; Wehrmann et al., 2011; Komada et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019). Hence, we assume a conservative estimate of 50% of CH4 flux to our budget as the average F(DIC–deep).

Reported average DIC uptake by authigenic carbonates from the total DIC pool at the SMTZ varies from 7–36% (Luff and Wallmann, 2003; Snyder et al., 2007; Wallmann et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2013; Coffin et al., 2014; Komada et al., 2016; Chuang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019), with upper estimates ranging up to 50% (Smith and Coffin, 2014). However, it is important to note that authigenic carbonates may not precipitate at all methane flux settings. Events of high-intensity fluxes (Karaca et al., 2010; Coffin et al., 2014), fluid flux with low dissolved methane concentrations, settings with intense bioturbation or high sedimentation rates (Luff et al., 2004; Bayon et al., 2007) can inhibit carbonate precipitation. Furthermore, dissolution of authigenic carbonates can occur under multiple conditions, including when aerobic methanotrophy produces CO2, when sulfide oxidation produces acid, which is corrosive (Matsumoto, 1990; Himmler et al., 2011); CO2 produced from methanogenesis (Meister et al., 2011); and due to CO2 produced in thermogenic gas seeps (Kinnaman et al., 2010)—among other drivers of dissolution. Rates of authigenic carbonate dissolution at diffusive methane flux sites are not well known. In our calculations, we assume a conservative estimate of 20% for FCarb as an average, considering the still-limited global perspective. This value is comparable to the recent estimates of Zhang et al. (2019, 20%) and Komada et al. (2016, 25%), who treated all three parameters in Eq. 6 as Total(DIC).

In exceptional cases, up to 85% incorporation of AOM induced DIC has been reported for the SOC pool (Coffin et al., 2015). However, in general, the production of new microbial biomass in anoxic sediments based on AOM is negligible due to low growth yield and accounts for only 1–3% of the methane consumption (Nauhaus et al., 2007; Treude et al., 2007). Hence the bulk SOC pool often does not represent the new biomass and the DOC produced via AOM (Ussler and Paull, 2008; Coffin et al., 2014). Modeling studies have shown that AOM is the dominant process at SOC values <5% (Sivan et al., 2007). Hence, we use an FSOC = 5% as an average estimate for DIC conversion to organic carbon at the SMTZ in our calculation.

With a portion of Total(DIC) going to authigenic carbonate and SOC, the remaining DIC from Total(DIC) (averaging 75% based on a Fcarb = 20 and FSOC = 5%) enters the overlying sediment and eventually the water column if it is not involved in diagenesis on the way. This DIC flux can, in turn, and significantly impact ocean chemistry.

It is also important to mention that methane fluxes are highly variable in time, resulting in upward and downward movement of the SMTZ (e.g., Malone et al., 2002; Meister et al., 2007, 2019a; Contreras et al., 2013; Meister, 2015). Such dynamic conditions could lead to strong variations in the parameters discussed above and the net DIC sinks and sources. Hence, we consider an extended range of these parameters in Table 1 to address the flux variability. This approach also considers the still-limited global perspective of these parameters.

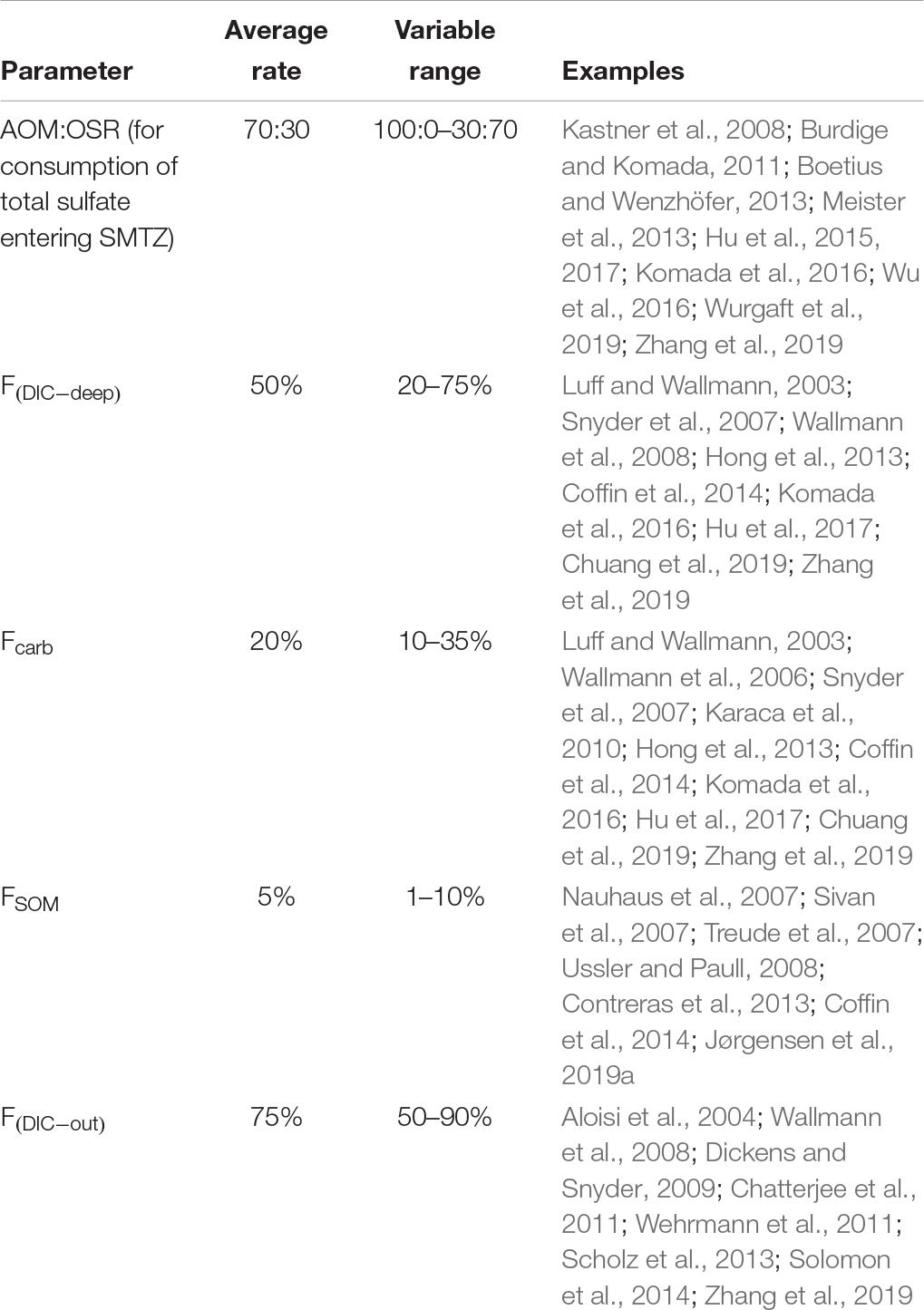

Table 1. Parameters controlling the DIC fluxes at SMTZ, with their average and extended range considered in carbon flux calculation.

We assume global average DIC production at SMTZ as suggested by Egger et al. (2018) along with their average CH4:SO42– fluxes to SMTZ of 1:1.4. This approach assumes quantitative methane consumption at SMTZ. AOM produces 1 mole of DIC for every mole of SO42– consumed. OSR, on the other hand, would produce 2 moles of DIC for every mole of SO42– consumed (Eqs 1 and 2). For a global average CH4:SO42– flux to the SMTZ of 1:1.4, 1.8 moles of DIC will be produced by sulfate reduction via AOM and OSR—that is, of the total 1.4 moles of SO42– entering SMTZ, 1 mole DIC will be produced by 1 mole SO42– reduction via AOM, and the remaining 0.4 moles of SO42– yields 0.8 moles DIC via OSR. Thus, the SO42–: DIC ratio from a CH4: SO42– flux ratio of 1:1.4 at the SMTZ will be 1.4:1.8 or 1:1.3 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Plots for SO42–: DIC ratio for AOM and OSR. Black slopes indicate AOM (1:1) and OSR (1:2). The blue slope indicates SO42–: DIC plot calculated from 740 diffusion-controlled marine methane flux sites globally by Egger et al. (2018), with SO42– flux data from 509 sites. CH4 concentrations were adjusted using a 1:1.4 flux ratio for CH4: SO42– and the combined effect of AOM and OSR results in a SO42–: DIC ratio ∼1:1.3.

Considering an average F(DIC–deep) of 50% of the CH4 flux, Total(DIC) through the SMTZ for a CH4: SO42– flux ratio of 1:1.4 can be given as:

Of this Total(DIC), an estimated DIC outflow toward the water column can be calculated using an average estimate of FCarb = 20 and FSOC = 5 as:

Thus, on average, for every mole of CH4 entering the SMTZ in diffusive setting, ∼0.5 moles of DIC precipitates as authigenic carbonate and ∼1.7 moles of DIC flow upward from the SMTZ toward the seafloor and water column.

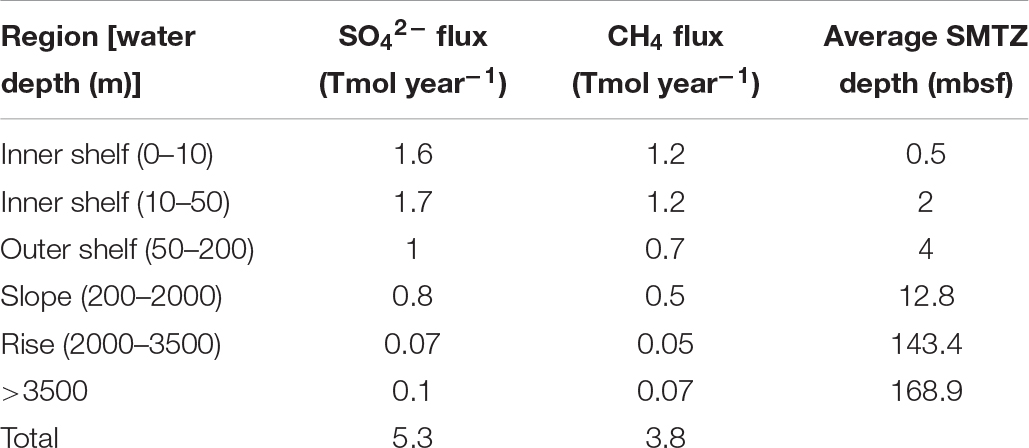

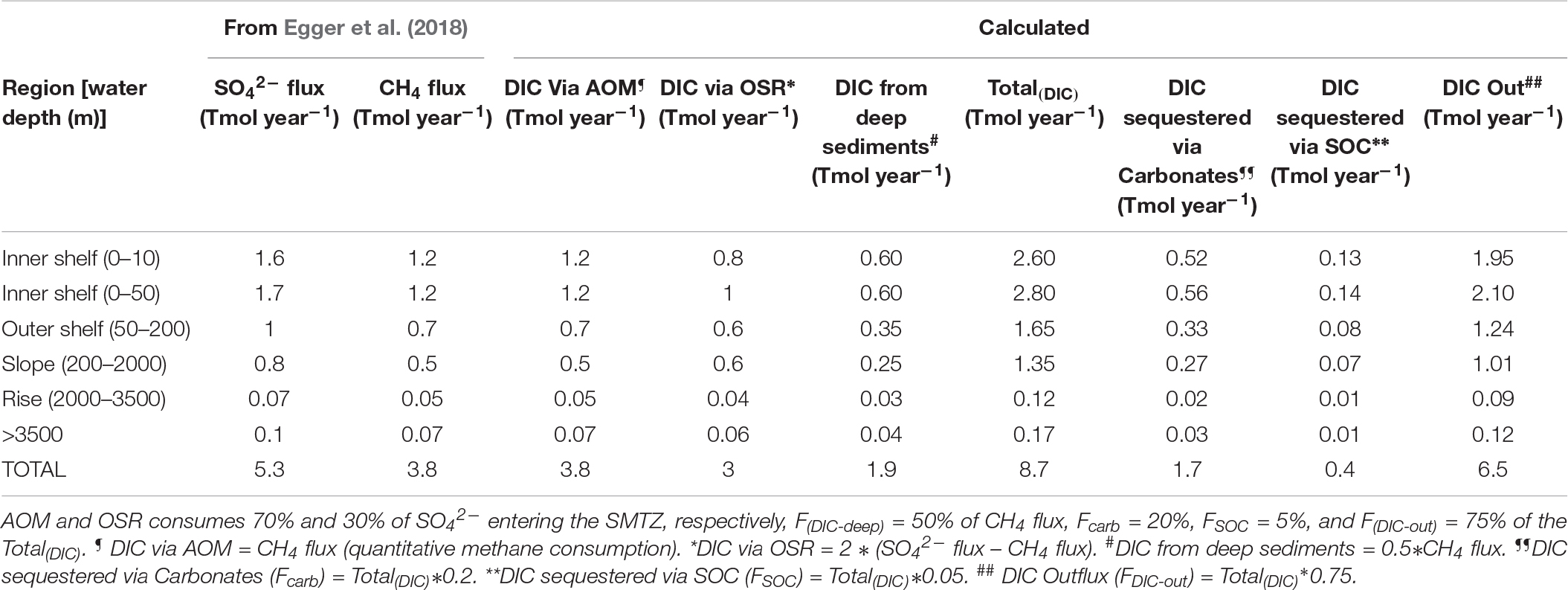

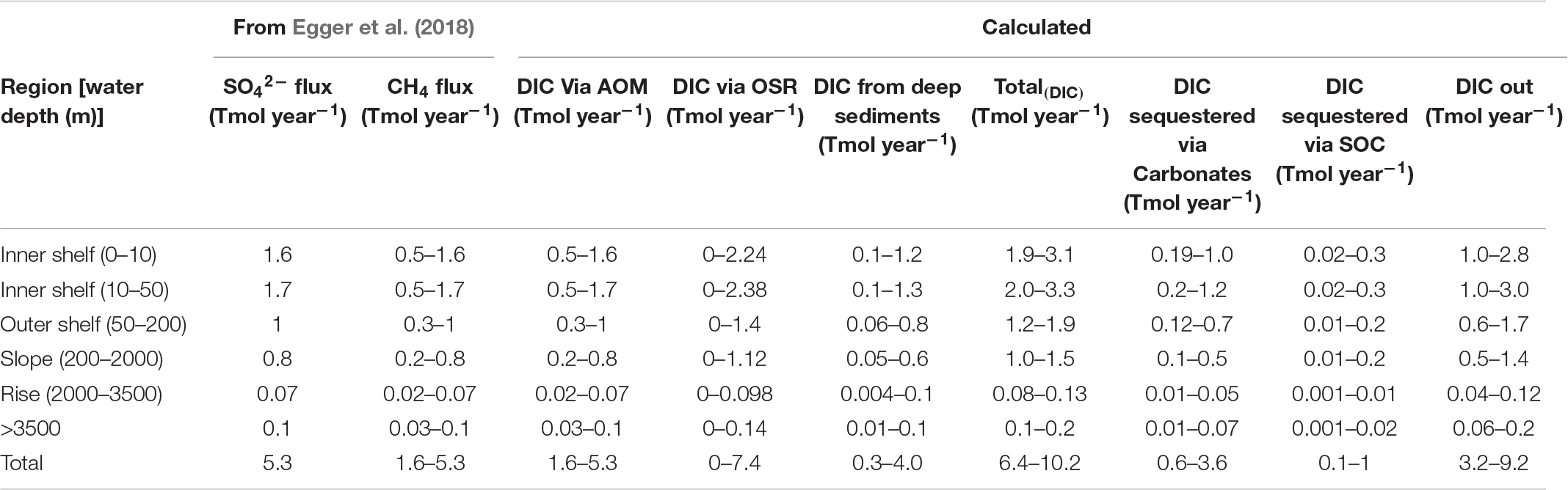

A global estimate of DIC cycling in diffusive methane-charged shallow sediments is derived using the recent compilation of global diffusive methane and sulfate fluxes into the SMTZ in marine settings from 740 sites by Egger et al. (2018, Tables 2–4).

Table 2. Global estimate of diffusive CH4 and SO42– flux based on 1:1.4 ratio, and average SMTZ depth compiled from 740 sites (Egger et al., 2018).

Table 3. Average values for parameters in Table 2, for a global CH4 flux of 3.8 Tmol year–1 and SO42– flux of 5.3 Tmol year–1.

Table 4. Range of DIC flux values based on variable ranges of DIC flux parameters in Table 1 details in the Supplementary Data.

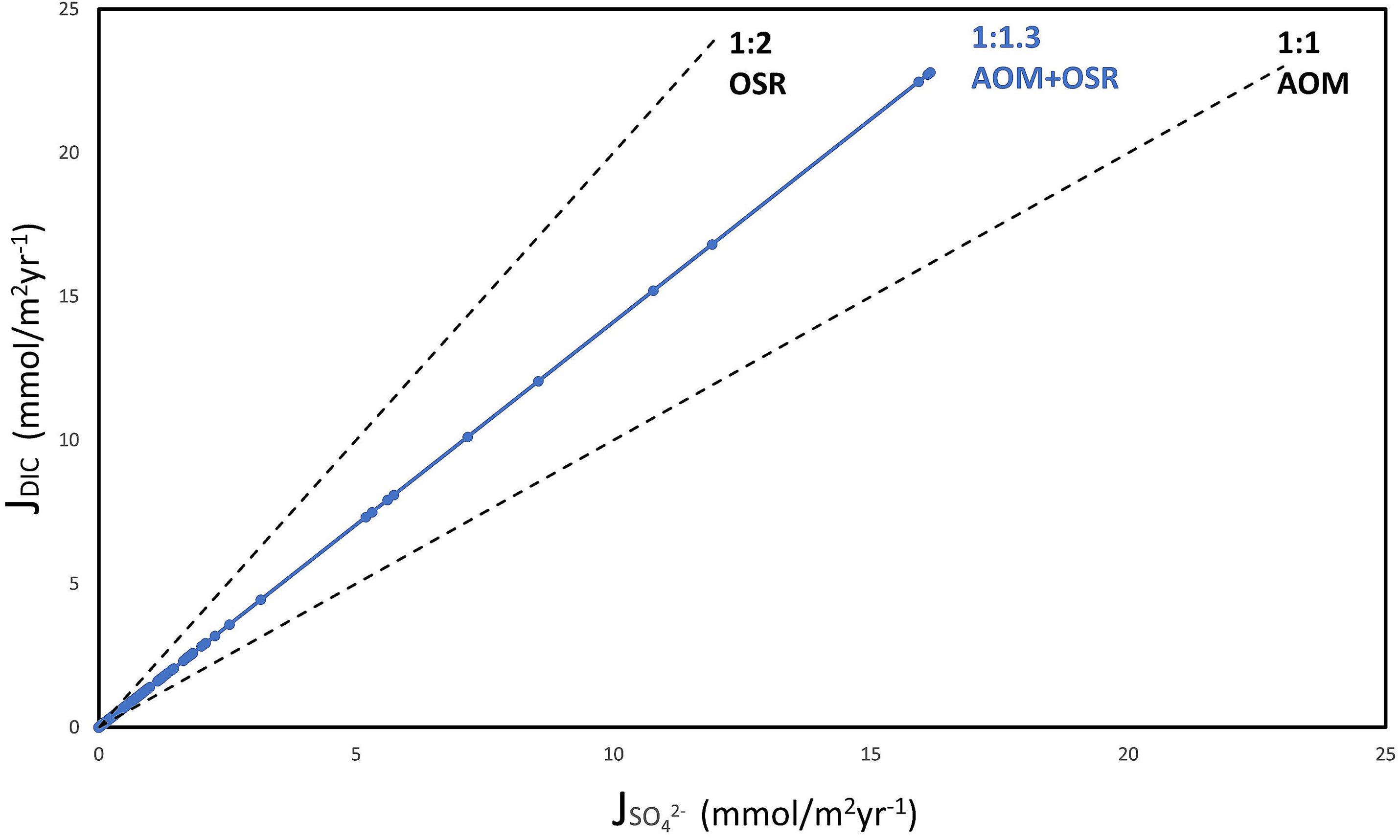

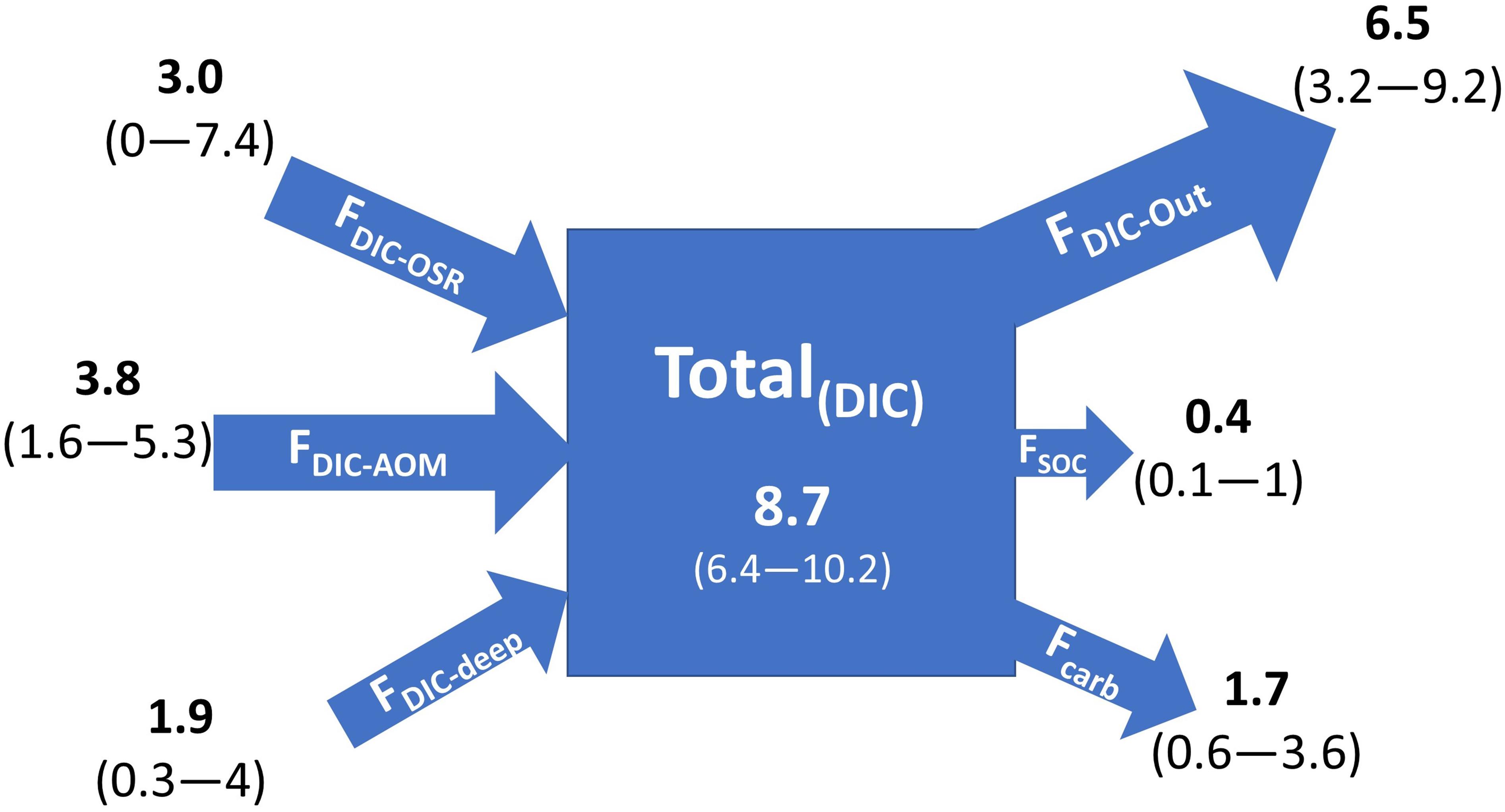

We highlight the major DIC fluxes through the SMTZ in methane-charged shallow marine sediments under diffusion-controlled settings with the following estimated values (Figure 4):

Figure 4. Sources and sinks of DIC through the SMTZ in methane-charged shallow sediments. The numbers in bold indicate flux values in Tmol year– 1. Numbers in the parentheses indicate the flux values with an extended range of parameters considered in Table 1. Size of the arrows indicates relative DIC flux contribution.

a. 8.7 Tmol year–1 DIC input [Total(DIC)] due to AOM, OSR, and deep-DIC flux (range: 6.4–10.2 Tmol year–1) enters the shallow sediments.

b. 6.5 Tmol year–1 DIC outflux F(DIC–out) toward the seafloor and water column (range 3.2–9.2 Tmol year–1).

c. 1.7 Tmol year–1 DIC sink via authigenic carbonate precipitation (Fcarb) (range: 0.6–3.6 Tmol year–1).

d. 0.4 Tmol year–1 DIC enters the SOC pool due to microbial uptake (FSOC) (range 0.1–1 Tmol year–1).

We would like to point out that our model curve is determined from current turnover rates and methane fluxes would vary strongly over time. While data necessary to constrain the temporal variability of fluxes is not available, we acknowledge this limitation. Consideration of an extended range for all the parameters we used in our DIC budget aims to address this dynamic nature of methane fluxes. Furthermore, it is also important to note that present estimates on global marine methane fluxes are heavily dependent on data from continental margins. Methane venting in the deep sea remains to a great part unexplored (e.g., Boetius and Wenzhöfer, 2013). The uncertainty on global marine methane flux estimates is expected to narrow down in the coming decade with rapidly improving mapping efforts and long-term flux monitoring programs. We also emphasize that we based our DIC flux estimates on the pore fluid data compiled by Egger et al. (2018), due to an extensive geochemical database it considers (740 global sites from a wide range of oceanographic settings). Calculations based on the other estimates, ∼1.2 Tmol CH4 year–1 by Wallmann et al. (2012) and 19 Tmol CH4 year–1 by Hinrichs and Boetius (2002) would provide much wider flux range (Supplementary Table 3).

Methane-derived authigenic carbonate precipitation in diffusive settings averaging 1.7 Tmol year–1 (range: 0.6–3.6 Tmol year–1) is close to the 1 Tmol year–1 estimated by Sun and Turchyn (2014) and 1.5 Tmol year–1 suggested by Wallmann et al. (2008), for a methane flux estimate of 5 Tmol year–1). Our estimated average corresponds to 11–15% of 11–15 Tmol year–1 carbonate accumulation estimated for continental shelf sediments and 15% of ∼11 Tmol year–1 in pelagic oceans (Milliman, 1993; Archer, 1996; Milliman and Droxler, 1996; Iglesias-Rodriguez et al., 2002; Schneider et al., 2006; Wallmann and Aloisi, 2012).

However, this estimate is an order of magnitude higher than the recently suggested estimate of 0.14 Tmol year–1 by Bradbury and Turchyn (2019). Multiple factors could be responsible for this mismatch. Previous estimates for global carbonate authigenesis were based primarily on the Ca2+ flux into sediments from the overlying water column and do not account for Ca2+ fluxes toward shallow sediment from deep methanogenic zones due to MSiW (Longman et al., 2019). Further, a higher authigenic carbonate sink is expected when Mg2+ fluxes into shallow marine sediments are also considered along with the Ca2+ fluxes (Berg, 2018; Berg et al., 2019). Moreover, the CH4 and SO42– flux data used in this study from the compilation by Egger et al. (2018) covers a higher number of diffusive methane flux locations from IODP and non-IODP expeditions than those used by Sun and Turchyn (2014) and Bradbury and Turchyn (2019), which were based solely on the ODP/IODP database. Estimates of global methane flux-related processes based exclusively on the ODP/IODP dataset have important limitations. So far, only a handful of ODP/IODP expeditions (e.g., 146, 164, 204, X311, and X341S) were dedicated to methane/gas hydrate research. Further, to the best of our knowledge, ∼33 drill sites have shown SMTZ depths below 10 mbsf. The data compilation used here from Egger et al. (2018) includes data from 323 non-IODP sediment cores (coring sites) globally with ∼290 sites with an SMTZ depth of <10 mbsf, and the remaining sites have an SMTZ depth of <20 mbsf. Many of the past ODP/IODP sites do not have pore fluid measurements from the top 1 mbsf whereas the data from non-IODP sediment cores focused on diffusive methane flux sites shows ∼100 global sites with an SMTZ less than 1 mbsf. Thus, the drilling-based dataset grossly underestimates DIC entering the SMTZs in coastal settings, which in turn constitutes ∼65% of global diffusive methane flux. Hence, the combination of IODP and non-IODP sediment core data used here, based on Egger et al. (2018), can provide better constraints to the global DIC cycling at diffusive methane flux settings.

Recently, it was postulated that carbonate cap rocks sealing the majority of hydrocarbon systems could be formed via AOM (Caesar et al., 2019). Further, carbonate authigenesis is suggested to be more dominant in slope settings, especially during the periods of widespread anoxia in geologic history, because of the prevalent anaerobic respiration in comparison to margins (Higgins et al., 2009; Schrag et al., 2013). These studies suggest large unexplored authigenic carbonate deposits that account for thousands of Gt C sequestration over millions of years. Authigenic carbonates formed below SMTZ in methanogenic zones (Ca[Fe,Mg,Mn,Ba]CO3) with distinctly enriched δ13C (>5‰) are well known (e.g., Rodriguez et al., 2000; Naehr et al., 2007; Meister et al., 2011; Solomon et al., 2014; Teichert et al., 2014; Pierre et al., 2016; Phillips et al., 2018; Torres et al., 2020). If we assume 20–50% of the DIC from methanogenic zones is sequestered as authigenic carbonate below the SMTZ, net methane-induced authigenic carbonate precipitation at the SMTZ and in the methanogenic depths below would be 2.5–3.6 Tmol year–1, for a global 3.8 Tmol year–1 of methane production suggested by Egger et al. (2018). This range is consistent, at the lower end, with the estimate of 3.3–13.3 Tmol year–1 by Wallmann et al. (2008) and the higher end of 1–4 Tmol year–1 suggested by Torres et al. (2020). These estimates amount to a significant carbon sink that must be accounted for in global carbonate accumulation budgets.

In present-day settings, 6.5 Tmol year–1 (range 3.2–9.2 Tmol year–1) of DIC flux toward the seafloor and water column from the SMTZ. In comparison, this amount is ∼20% (range: 10–28%) of the ∼33 Tmol year–1 of global riverine DIC fluxing to the oceans (Meybeck, 1993; Amiotte Suchet et al., 2003; Aufdenkampe et al., 2011; Li et al., 2017). Most of our estimated DIC outflux (98%) occurs in continental margin sediments with shallow SMTZ depths of ∼13 mbsf (Table 2). Hence, this DIC flux can enter the water column, if it is not involved in diagenesis on the way, and impact ocean chemistry. As oceans continue to absorb rapidly rising atmospheric CO2, the water column is prone to pH reduction with significant changes to ocean chemistry, associated biogeochemical cycling, and marine ecology (Doney et al., 2009). A pH reduction on the scale of 0.3–0.4 units has been predicted for the end of the 21st century (Feely et al., 2009). Further, under advective conditions, methane can enter the water column and undergo aerobic methane oxidation, which consumes bottom water oxygen and contributes to acidification through the production of CO2 (Biastoch et al., 2011; Boetius and Wenzhöfer, 2013; Boudreau et al., 2015).

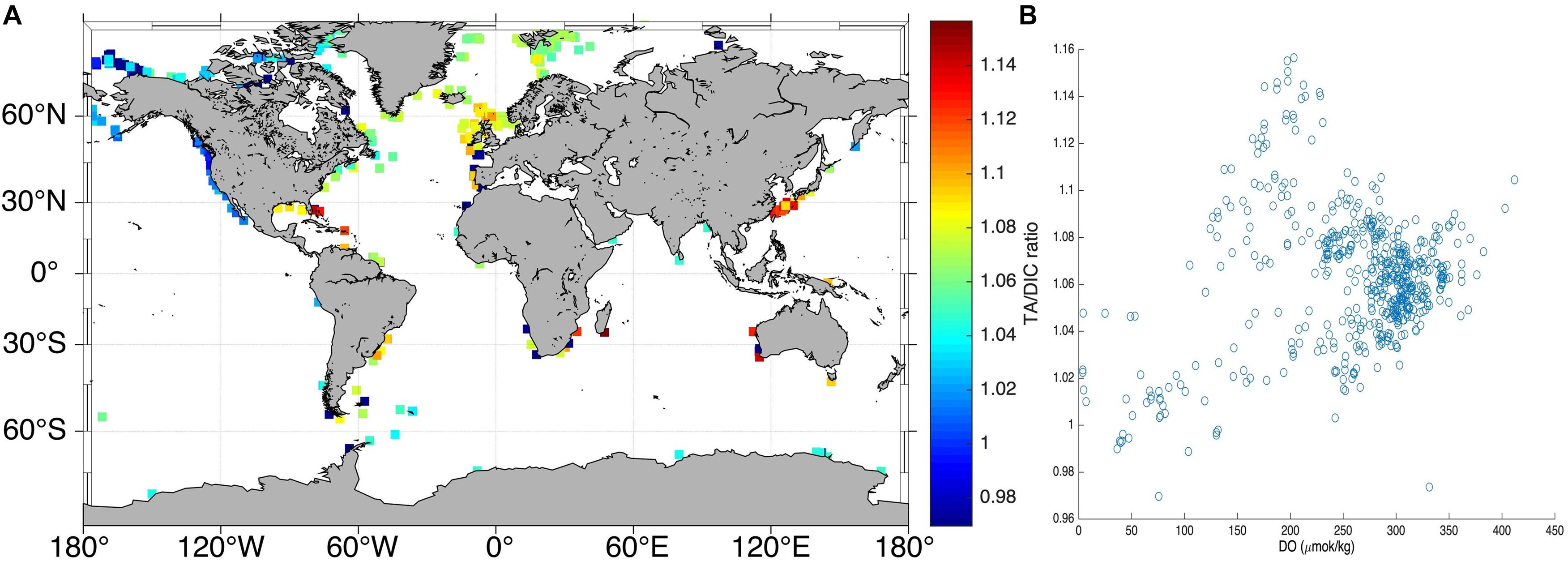

Alkalinity contribution from the sediments to the water column has important implications for ongoing climate change as they can reduce the ocean acidification effect and even enhance the CO2 absorption capacity of surface water (Chen and Wang, 1999; Chen, 2002; Thomas et al., 2008; Hu and Cai, 2011; Krumins et al., 2013; Brenner et al., 2016). Hence, evaluating the contribution of DIC outflux to the water column in terms of total alkalinity (TA) to DIC ratio is of great importance. Most (86%) of the DIC outflux at diffusive methane flux settings is occurring within SMTZ depths of ≤4 mbsf and bathymetry below 200 m (Tables 2–4). Minimum TA/DIC ratios in the water column 20 m above the seabed under oxygen-limited conditions on continental shelves (100–250 m bathymetry) is generally ≤1 (Figure 5). This relationship implies that if the DIC outflux has a TA/DIC ratio of >1, it is contributed as alkalinity to the water column.

Figure 5. Global trend of TA/DIC ratio above the seafloor for oxygen-limited coastal setting. (A) Global distribution of TA/DIC at 100–250 m bathymetry within 20 m above the seabed. (B) Global distribution of TA/DIC at different oxygen concentrations. It can be noticed that the minimum TA/DIC ratio is about 1, under oxygen-limited condition in the shallow bathymetry settings. Data Resource: GLODAPv2 (Key et al., 2015; Lauvset et al., 2016; Olsen et al., 2016).

TA/DIC for the net DIC entering the SMTZ and above in diffusive settings—considering inputs from AOM (TA/DIC ratio = 2), OSR (TA/DIC ratio = 1), the deep-DIC flux (TA/DIC ratio = 1), and the average rates of DIC input parameters in Table 1 – will produce a value ∼1.4:

However, the TA/DIC flux ratio from this pool would be determined by the authigenic carbonate precipitation and the balance between sulfide burial and oxidation. As discussed below, sulfide burial relates to the extent of sulfide oxidation and related acid production. Otherwise, assuming the stoichiometry from Wallmann et al. (2008) (H2S + 2/5Fe2O3 → 2/5FeS2 + 1/5 FeS + 1/5 FeO + H2O), formation of sulfide minerals at the SMTZ would have no net impact on the TA/DIC ratio of DIC outflux. Carbonate precipitation would consume bicarbonate and reduce the TA by a factor of two. Thus, while methane derived authigenic carbonate precipitation sequesters a portion of total DIC entering the SMTZ, it will also contribute CO2 to the water column from shallow sediments by reducing the alkalinity of the DIC outflux. Net TA/DIC of DIC outflux for our average DIC budget (Figure 4) under hypothetical complete sulfide burial can be given by:

This relationship suggests that even with a hypothetical complete sulfide burial, Fcarb > 20% can cause DIC outflux to contribute CO2 to the water column. Maximum and Minimum TA/DIC estimates for DIC outflux based on varying parameter ranges used in this model are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Alkalinity flux would be different when sulfide oxidation occurs. AOM and OSR produce ∼5.3 Tmol year–1 sulfide at SMTZ (equivalent to total SO42– consumption). Complete or at least significant sulfide burial (e.g., Hensen et al., 2003; Dickens, 2011) could result in a substantial alkalinity contribution from sediments. Oxidation of this entire sulfide pool can, in contrast, produce acid and effectively neutralize the alkalinity flux. It has been suggested that globally 5 to 20% of the sulfide produced in sediments is buried as iron minerals (e.g., FeS, FeS2) or with organic matter and the remaining is reoxidized to sulfate (Berner, 1982; Jørgensen, 1982; Jørgensen and Nelson, 2004; Zopfi et al., 2004; Wasmund et al., 2017).

Since marine methane flux settings have diagenetic systems different than sites without methane fluxes (e.g., Formolo and Lyons, 2013), the sulfide burial rate at diffusive methane flux settings could differ from the global average (Dickens, 2011). For example, nearly quantitative precipitation of all reduced sulfur by AOM was reported for an iron-rich, non-steady-state setting (Hensen et al., 2003) and more recently, and two thirds of sulfide produced via AOM and OSR at the SMTZ was inferred to undergo burial (Wurgaft et al., 2019). Availability of reactive iron (for sulfide burial) as well as the ratio of burial versus oxidation of the sulfide produced at the SMTZ is thus an important parameter in determining the impact of methane induced carbon cycling at diffusive methane flux settings. In general, a combination of higher sulfide burial with lower carbonate precipitation rates can result in a DIC outflux that contributes alkalinity from sediments, and the opposite can result in DIC contribution as CO2. We assume the latter to be dominant in the present-day setting—that is, inefficient sulfide burial and high carbonate precipitation—which implies that out fluxing DIC would be a contributor to ongoing ocean acidification. We also emphasize the importance of integrated C-S-Fe approach to understand how these subsurface processes affect water column chemistry. Future studies should quantify the rates of sulfide oxidation and carbonate authigenesis in diverse and globally distributed settings characterized by subsurface methane fluxes to improve on these first-order estimates.

We estimated DIC cycling in methane charged shallow sediments with global values for diffusive methane and sulfate fluxes into the SMTZ. Our synthesis highlights major diffusive methane-powered carbon fluxes with 8.7 Tmol year–1 DIC (range 6.4–10.2 Tmol year–1) entering the shallow sediments due to AOM, OSR, and the deep-DIC flux. An estimated 6.5 Tmol year–1 (range 3.2–9.2 Tmol year–1) of the this DIC pool flows toward the water column. This DIC outflux will contribute alkalinity or CO2 in different proportions to the water column, depending on the rates of authigenic carbonate precipitation and sulfide oxidation. At present, settings with pervasive authigenic carbonate precipitation and sulfide oxidation are contributing CO2 and thus to ocean acidification. Our estimates also suggest that globally distributed precipitation of authigenic carbonate minerals at SMTZ characterized by diffusive methane transport sequesters an average of 1.7 Tmol year–1 (range: 0.6–3.6 Tmol year–1). This estimate is equivalent to ∼15% of carbonate accumulation in neritic and in pelagic sediments, respectively. Our study also suggests the need for detailed pore fluid chemical analysis in future expeditions at diffusive settings, which would include quantification of F(DIC–deep), Fcarb, and sulfide oxidation rates. Overall, we emphasize that settings characterized by diffusive methane fluxes may play an even larger role in oceanic carbon cycling via conversion of methane carbon to inorganic carbon, which contributes significantly to oceanic DIC pool and carbonate accumulation. These pathways must be included in coastal and geologic carbon models.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

SA conceptualized the project and wrote the manuscript. RC, HA, and TL helped in the expansion of concepts, manuscript preparation, data synthesis, and calculations.

TL acknowledges funding from the ACS-PRF.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

SA would like to acknowledge the TAMUCC CMSS Research Assistantship during this manuscript preparation and Dr. Xinping Hu (TAMUCC) for constructive discussions on chemical implication of the DIC outflux in the article. We would like to thank the two reviewers for their constructive inputs that greatly improved this manuscript.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2020.00206/full#supplementary-material

Aleksandra, B.-G., and Katarzyna, Ł-M. (2018). Porewater dissolved organic and inorganic carbon in relation to methane occurrence in sediments of the Gdańsk Basin (southern Baltic Sea). Cont. Shelf Res. 168, 11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2018.08.008

Aloisi, G., Bouloubassi, I., Heijs, S. K., Pancost, R. D., Pierre, C., Damsté, J. S. S., et al. (2002). CH4-consuming microorganisms and the formation of carbonate crusts at cold seeps. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 203, 195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0012-821x(02)00878-6

Aloisi, G., Wallmann, K., Drews, M., and Bohrmann, G. (2004). Evidence for the submarine weathering of silicate minerals in Black Sea sediments: possible implications for the marine Li and B cycles. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 5:Q04007. doi: 10.1029/2003GC000639

Amiotte Suchet, P., Probst, J. L., and Ludwig, W. (2003). Worldwide distribution of continental rock lithology: implications for the atmospheric/soil CO2 uptake by continental weathering and alkalinity river transport to the oceans. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 17:1038. doi: 10.1029/2002GB001891

Archer, D. E. (1996). An atlas of the distribution of calcium carbonate in sediments of the deep sea. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 10, 159–174. doi: 10.1029/95gb03016

Aufdenkampe, A. K., Mayorga, E., Raymond, P. A., Melack, J. M., Doney, S. C., Alin, S. R., et al. (2011). Riverine coupling of biogeochemical cycles between land, oceans, and atmosphere. Front. Ecol. Environ. 9, 53–60. doi: 10.1890/100014

Baker, P. A., and Burns, S. J. (1985). Occurrence and formation of dolomite in organic-rich continental margin sediments. AAPG Bull. 69, 1917–1930.

Bayon, G., Pierre, C., Etoubleau, J., Voisset, M., Cauquil, E., Marsset, T., et al. (2007). Sr/Ca and Mg/Ca ratios in niger delta sediments: implications for authigenic carbonate genesis in cold seep environments. Mar. Geol. 241, 93–109. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2007.03.007

Berelson, W., Balch, W., Najjar, R., Feely, R., Sabine, C., and Lee, K. (2007). Relating estimates of CaCO3 production, export, and dissolution in the water column to measurements of CaCO3 rain into sediment traps and dissolution on the sea floor: a revised global carbonate budget. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 21:GB1024. doi: 10.1029/2006GB002803

Berelson, W. M., Prokopenko, M., Sansone, F., Graham, A., Mcmanus, J., and Bernhard, J. M. (2005). Anaerobic diagenesis of silica and carbon in continental margin sediments: discrete zones of TCO 2 production. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 4611–4629. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2005.05.011

Berg, R. D. (2018). Quantifying the Deep: The Importance of Diagenetic Reactions to Marine Geochemical Cycles. Thesis Ph.D., University of Washington, Washington, D.C.

Berg, R. D., Solomon, E. A., and Teng, F.-Z. (2019). The role of marine sediment diagenesis in the modern oceanic magnesium cycle. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–10.

Berner, R. A. (1982). Burial of organic carbon and pyrite sulfur in the modern ocean: its geochemical and environmental significance. Am. J. Sci. 282, 451–473. doi: 10.2475/ajs.282.4.451

Beulig, F., Roy, H., Mcglynn, S. E., and Jorgensen, B. B. (2019). Cryptic CH4 cycling in the sulfate-methane transition of marine sediments apparently mediated by ANME-1 archaea. ISME J. 13, 250–262. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0273-z

Biastoch, A., Treude, T., Rüpke, L. H., Riebesell, U., Roth, C., Burwicz, E. B., et al. (2011). Rising Arctic Ocean temperatures cause gas hydrate destabilization and ocean acidification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38:L08602. doi: 10.1029/2011GL047222

Boetius, A., Ravenschlag, K., Schubert, C. J., Rickert, D., Widdel, F., Gieseke, A., et al. (2000). A marine microbial consortium apparently mediating anaerobic oxidation of methane. Nature 407:623. doi: 10.1038/35036572

Boetius, A., and Wenzhöfer, F. (2013). Seafloor oxygen consumption fuelled by methane from cold seeps. Nat. Geosci. 6, 725–734. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1926

Borowski, W. S., Paull, C. K., and Ussler, W. (1996). Marine pore-water sulfate profiles indicate in situ methane flux from underlying gas hydrate. Geology 24, 655–658.

Borowski, W. S., Paull, C. K., and Ussler Iii, W. (1997). Carbon cycling within the upper methanogenic zone of continental rise sediments; an example from the methane-rich sediments overlying the Blake Ridge gas hydrate deposits. Mar. Chem. 57, 299–311. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4203(97)00019-4

Boudreau, B. P., Luo, Y., Meysman, F. J., Middelburg, J. J., and Dickens, G. R. (2015). Gas hydrate dissociation prolongs acidification of the Anthropocene oceans. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 9337A–9344A.

Bowles, M. W., Mogollón, J. M., Kasten, S., Zabel, M., and Hinrichs, K.-U. (2014). Global rates of marine sulfate reduction and implications for sub–sea-floor metabolic activities. Science 344, 889–891. doi: 10.1126/science.1249213

Bradbury, H. J., and Turchyn, A. V. (2019). Reevaluating the carbon sink due to sedimentary carbonate formation in modern marine sediments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 519, 40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2019.04.044

Brenner, H., Braeckman, U., Le Guitton, M., and Meysman, F. J. (2016). The impact of sedimentary alkalinity release on the water column CO 2 system in the North Sea. Biogeosciences 13, 841–863. doi: 10.5194/bg-13-841-2016

Burdige, D. J., and Komada, T. (2011). Anaerobic oxidation of methane and the stoichiometry of remineralization processes in continental margin sediments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 1781–1796. doi: 10.4319/lo.2011.56.5.1781

Caesar, K. H., Kyle, J. R., Lyons, T. W., Tripati, A., and Loyd, S. J. (2019). Carbonate formation in salt dome cap rocks by microbial anaerobic oxidation of methane. Nat. Commun. 10:08.

Chatterjee, S., Dickens, G. R., Bhatnagar, G., Chapman, W. G., Dugan, B., Snyder, G. T., et al. (2011). Pore water sulfate, alkalinity, and carbon isotope profiles in shallow sediment above marine gas hydrate systems: a numerical modeling perspective. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 116:B09103. doi: 10.1029/2011JB008290

Chen, C.-T. A. (2002). Shelf-vs. dissolution-generated alkalinity above the chemical lysocline. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 49, 5365–5375. doi: 10.1016/s0967-0645(02)00196-0

Chen, C. T. A., and Wang, S. L. (1999). Carbon, alkalinity and nutrient budgets on the East China Sea continental shelf. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 104, 20675–20686. doi: 10.1029/1999jc900055

Chuang, P.-C., Yang, T. F., Wallmann, K., Matsumoto, R., Hu, C.-Y., Chen, H.-W., et al. (2019). Carbon isotope exchange during anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) in sediments of the northeastern South China Sea. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 246, 138–155. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2018.11.003

Coffin, R., Hamdan, L., Smith, J., Rose, P., Plummer, R., Yoza, B., et al. (2014). Contribution of vertical methane flux to shallow sediment carbon pools across Porangahau Ridge, New Zealand. Energies 7, 5332–5356. doi: 10.3390/en7085332

Coffin, R. B., Osburn, C. L., Plummer, R. E., Smith, J. P., Rose, P. S., and Grabowski, K. S. (2015). Deep sediment-sourced methane contribution to shallow sediment organic carbon: atwater valley, texas-louisiana shelf, gulf of mexico. Energies 8, 1561–1583. doi: 10.3390/en8031561

Contreras, S., Meister, P., Liu, B., Prieto-Mollar, X., Hinrichs, K.-U., Khalili, A., et al. (2013). Cyclic 100-ka (glacial-interglacial) migration of subseafloor redox zonation on the Peruvian shelf. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 18098–18103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305981110

Crémière, A., Pierre, C., Blanc-Valleron, M.-M., Zitter, T., Çaðatay, M. N., and Henry, P. (2012). Methane-derived authigenic carbonates along the North Anatolian fault system in the Sea of Marmara (Turkey). Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 66, 114–130. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2012.03.014

Dickens, G. R. (2003). Rethinking the global carbon cycle with a large, dynamic and microbially mediated gas hydrate capacitor. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 213, 169–183. doi: 10.1016/s0012-821x(03)00325-x

Dickens, G. R. (2011). Down the rabbit hole: toward appropriate discussion of methane release from gas hydrate systems during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum and other past hyperthermal events. Clim. Past 7, 831–846. doi: 10.5194/cp-7-831-2011

Dickens, G. R., O’neil, J. R., Rea, D. K., and Owen, R. M. (1995). Dissociation of oceanic methane hydrate as a cause of the carbon isotope excursion at the end of the Paleocene. Paleoceanography 10, 965–971. doi: 10.1029/95pa02087

Dickens, G. R., and Snyder, G. T. (2009). Interpreting upward methane flux from marine pore water profiles. Fire Ice Winter 9, 7–10.

Doney, S. C., Fabry, V. J., Feely, R. A., and Kleypas, J. A. (2009). Ocean acidification: the other CO2 problem. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 1, 169–192.

Egger, M., Riedinger, N., Mogollón, J. M., and Jørgensen, B. B. (2018). Global diffusive fluxes of methane in marine sediments. Nat. Geosci. 11:421. doi: 10.1038/s41561-018-0122-8

Feely, R. A., Doney, S. C., and Cooley, S. R. (2009). Ocean acidification: present conditions and future changes in a high-CO2 world. Oceanography 22, 36–47. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2009.95

Feng, D., Chen, D., Peckmann, J., and Bohrmann, G. (2010). Authigenic carbonates from methane seeps of the northern Congo fan: microbial formation mechanism. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 27, 748–756. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.08.006

Formolo, M. J., and Lyons, T. W. (2013). Sulfur biogeochemistry of cold seeps in the Green Canyon region of the Gulf of Mexico. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 119, 264–285. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2013.05.017

Henrichs, S. M., and Reeburgh, W. S. (1987). Anaerobic mineralization of marine sediment organic matter: rates and the role of anaerobic processes in the oceanic carbon economy. Geomicrobiol. J. 5, 191–237. doi: 10.1080/01490458709385971

Hensen, C., Zabel, M., Pfeifer, K., Schwenk, T., Kasten, S., Riedinger, N., et al. (2003). Control of sulfate pore-water profiles by sedimentary events and the significance of anaerobic oxidation of methane for the burial of sulfur in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 2631–2647. doi: 10.1016/s0016-7037(03)00199-6

Hesselbo, S. P., Grocke, D. R., Jenkyns, H. C., Bjerrum, C. J., Farrimond, P., Morgans Bell, H. S., et al. (2000). Massive dissociation of gas hydrate during a Jurassic oceanic anoxic event. Nature 406, 392–395. doi: 10.1038/35019044

Higgins, J. A., Fischer, W., and Schrag, D. (2009). Oxygenation of the ocean and sediments: consequences for the seafloor carbonate factory. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 284, 25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2009.03.039

Himmler, T., Brinkmann, F., Bohrmann, G., and Peckmann, J. (2011). Corrosion patterns of seep-carbonates from the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Terra Nova 23, 206–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3121.2011.01000.x

Hinrichs, K.-U., and Boetius, A. (2002). “The anaerobic oxidation of methane: new insights in microbial ecology and biogeochemistry,” in Ocean Margin Systems, eds G. Wefer, D. Billet, D. Hebbeln, B. B. Jorgensen, M. Schlüter, and T. C. E. Van Weering (Berlin: Springer), 457–477. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-05127-6_28

Hong, W.-L., Torres, M. E., Kim, J.-H., Choi, J., and Bahk, J.-J. (2013). Carbon cycling within the sulfate-methane-transition-zone in marine sediments from the Ulleung Basin. Biogeochemistry 115, 129–148. doi: 10.1007/s10533-012-9824-y

Hong, W.-L., Torres, M. E., Kim, J.-H., Choi, J., and Bahk, J.-J. (2014). Towards quantifying the reaction network around the sulfate–methane-transition-zone in the Ulleung Basin, East Sea, with a kinetic modeling approach. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 140, 127–141. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2014.05.032

Hu, C.-Y., Yang, T. F., Burr, G. S., Chuang, P.-C., Chen, H.-W., Walia, M., et al. (2017). Biogeochemical cycles at the sulfate-methane transition zone (SMTZ) and geochemical characteristics of the pore fluids offshore southwestern Taiwan. J. Asian Earth Sci. 149, 172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2017.07.002

Hu, X., and Cai, W. J. (2011). An assessment of ocean margin anaerobic processes on oceanic alkalinity budget. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 25:GB3003. doi: 10.1029/2010GB003859

Hu, Y., Feng, D., Liang, Q., Xia, Z., Chen, L., and Chen, D. (2015). Impact of anaerobic oxidation of methane on the geochemical cycle of redox-sensitive elements at cold-seep sites of the northern South China Sea. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 122, 84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2015.06.012

Iglesias-Rodriguez, M. D., Armstrong, R., Feely, R., Hood, R., Kleypas, J., Milliman, J. D., et al. (2002). Progress made in study of ocean’s calcium carbonate budget. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 83, 365–375. doi: 10.1029/2002eo000267

Jiang, G., Kennedy, M. J., and Christie-Blick, N. (2003). Stable isotopic evidence for methane seeps in Neoproterozoic postglacial cap carbonates. Nature 426, 822–826. doi: 10.1038/nature02201

Jørgensen, B., and Nelson, D. (2004). Sulfide oxidation in marine sediments: geochemistry meets microbiology. GSA Spec. Pap. 379, 63–81.

Jørgensen, B. B. (1982). Mineralization of organic matter in the sea bed—the role of sulphate reduction. Nature 296:643. doi: 10.1038/296643a0

Jørgensen, B. B., Beulig, F., Egger, M., Petro, C., Scholze, C., and Røy, H. (2019a). Organoclastic sulfate reduction in the sulfate-methane transition of marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 254, 231–245. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2019.03.016

Jørgensen, B. B., Findlay, A. J., and Pellerin, A. (2019b). The biogeochemical sulfur cycle of marine sediments. Front. Microbiol. 10:849. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00849

Jørgensen, B. B., and Kasten, S. (2006). “Sulfur cycling and methane oxidation,” in Marine Geochemistry, eds H. D. Schulz and M. Zabel (Berlin: Springer), 271–309. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32144-6_8

Judd, A., and Hovland, M. (2009). Seabed Fluid Flow: The Impact on Geology, Biology and the Marine Environment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Karaca, D., Hensen, C., and Wallmann, K. (2010). Controls on authigenic carbonate precipitation at cold seeps along the convergent margin off Costa Rica. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 11:Q08S27. doi: 10.1029/2010GC003062

Kastner, M., Claypool, G., and Robertson, G. (2008). Geochemical constraints on the origin of the pore fluids and gas hydrate distribution at Atwater Valley and Keathley Canyon, northern Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 25, 860–872. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2008.01.022

Key, R. M., Olsen, A., van Heuven, S., Lauvset, S. K., Velo, A., Lin, X., et al. (2015). Global Ocean Data Analysis Project, Version 2 (GLODAPv2), ORNL/CDIAC-162, ND-P093. Tennessee: Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center. doi: 10.3334/CDIAC/OTG.NDP093_GLODAPv2

Kim, J. H., Torres, M. E., Haley, B. A., Ryu, J. S., Park, M. H., Hong, W. L., et al. (2016). Marine silicate weathering in the anoxic sediment of the Ulleung Basin: evidence and consequences. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 17, 3437–3453. doi: 10.1002/2016gc006356

Kinnaman, F. S., Kimball, J. B., Busso, L., Birgel, D., Ding, H., Hinrichs, K.-U., et al. (2010). Gas flux and carbonate occurrence at a shallow seep of thermogenic natural gas. Geo-Mar. Lett. 30, 355–365. doi: 10.1007/s00367-010-0184-0

Knittel, K., and Boetius, A. (2009). Anaerobic oxidation of methane: progress with an unknown process. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63, 311–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093130

Komada, T., Burdige, D. J., Li, H.-L., Magen, C., Chanton, J. P., and Cada, A. K. (2016). Organic matter cycling across the sulfate-methane transition zone of the Santa Barbara Basin, California Borderland. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 176, 259–278. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2015.12.022

Krumins, V., Gehlen, M., Arndt, S., Cappellen, P. V., and Regnier, P. (2013). Dissolved inorganic carbon and alkalinity fluxes from coastal marine sediments: model estimates for different shelf environments and sensitivity to global change. Biogeosciences 10, 371–398. doi: 10.5194/bg-10-371-2013

Kvenvolden, K. A. (2002). Methane hydrate in the global organic carbon cycle. Terra Nova 14, 302–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3121.2002.00414.x

Lauvset, S. K., Key, R. M., Olsen, A., Van Heuven, S., Velo, A., Lin, X., et al. (2016). A new global interior ocean mapped climatology: the 1× 1 GLODAP version 2. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8, 325–340. doi: 10.5194/essd-8-325-2016

Levin, L. A., Baco, A. R., Bowden, D. A., Colaco, A., Cordes, E. E., Cunha, M. R., et al. (2016). Hydrothermal vents and methane seeps: rethinking the sphere of influence. Front. Mar. Sci. 3:72. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00072

Li, M., Peng, C., Wang, M., Xue, W., Zhang, K., Wang, K., et al. (2017). The carbon flux of global rivers: a re-evaluation of amount and spatial patterns. Ecol. Indic. 80, 40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.04.049

Longman, J., Palmer, M. R., Gernon, T. M., and Manners, H. R. (2019). The role of tephra in enhancing organic carbon preservation in marine sediments. Earth-Sci. Rev. 192, 480–490. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.03.018

Luff, R., and Wallmann, K. (2003). Fluid flow, methane fluxes, carbonate precipitation and biogeochemical turnover in gas hydrate-bearing sediments at Hydrate Ridge, Cascadia Margin: numerical modeling and mass balances. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 3403–3421. doi: 10.1016/s0016-7037(03)00127-3

Luff, R., Wallmann, K., and Aloisi, G. (2004). Numerical modeling of carbonate crust formation at cold vent sites: significance for fluid and methane budgets and chemosynthetic biological communities. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 221, 337–353. doi: 10.1016/s0012-821x(04)00107-4

Malinverno, A., and Pohlman, J. W. (2011). Modeling sulfate reduction in methane hydrate-bearing continental margin sediments: does a sulfate-methane transition require anaerobic oxidation of methane? Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 12:Q07006. doi: 10.1029/2011GC003501

Malone, M. J., Claypool, G., Martin, J. B., and Dickens, G. R. (2002). Variable methane fluxes in shallow marine systems over geologic time: the composition and origin of pore waters and authigenic carbonates on the New Jersey shelf. Mar. Geol. 189, 175–196. doi: 10.1016/s0025-3227(02)00474-7

Matsumoto, R. (1990). Vuggy carbonate crust formed by hydrocarbon seepage on the continental shelf of Baffin Island, northeast Canada. Geochem. J. 24, 143–158. doi: 10.2343/geochemj.24.143

Meister, P. (2015). For the deep biosphere, the present is not always the key to the past: what we can learn from the geological record. Terra Nova 27, 400–408. doi: 10.1111/ter.12174

Meister, P., Brunner, B., Picard, A., Böttcher, M. E., and Jørgensen, B. B. (2019a). Sulphur and carbon isotopes as tracers of past sub-seafloor microbial activity. Sci. Rep. 9:604.

Meister, P., Liu, B., Khalili, A., Böttcher, M. E., and Jørgensen, B. B. (2019b). Factors controlling the carbon isotope composition of dissolved inorganic carbon and methane in marine porewater: an evaluation by reaction-transport modelling. J. Mar. Syst. 200:103227. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2019.103227

Meister, P., Gutjahr, M., Frank, M., Bernasconi, S. M., Vasconcelos, C., and Mckenzie, J. A. (2011). Dolomite formation within the methanogenic zone induced by tectonically driven fluids in the Peru accretionary prism. Geology 39, 563–566. doi: 10.1130/g31810.1

Meister, P., Liu, B., Ferdelman, T. G., Jørgensen, B. B., and Khalili, A. (2013). Control of sulphate and methane distributions in marine sediments by organic matter reactivity. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 104, 183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2012.11.011

Meister, P., Mckenzie, J. A., Vasconcelos, C., Bernasconi, S., Frank, M., Gutjahr, M., et al. (2007). Dolomite formation in the dynamic deep biosphere: results from the Peru Margin. Sedimentology 54, 1007–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2007.00870.x

Meybeck, M. (1993). Riverine transport of atmospheric carbon: sources, global typology and budget. Water Air Soil Pollut. 70, 443–463. doi: 10.1007/978-94-011-1982-5_31

Milliman, J., and Droxler, A. (1996). Neritic and pelagic carbonate sedimentation in the marine environment: ignorance is not bliss. Geol. Rundschau 85, 496–504. doi: 10.1007/s005310050090

Milliman, J. D. (1993). Production and accumulation of calcium carbonate in the ocean: budget of a nonsteady state. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 7, 927–957. doi: 10.1029/93gb02524

Moore, W. S. (2010). The effect of submarine groundwater discharge on the ocean. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2, 59–88.

Naehr, T. H., Eichhubl, P., Orphan, V. J., Hovland, M., Paull, C. K., Ussler Iii, W., et al. (2007). Authigenic carbonate formation at hydrocarbon seeps in continental margin sediments: a comparative study. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 54, 1268–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2007.04.010

Nauhaus, K., Albrecht, M., Elvert, M., Boetius, A., and Widdel, F. (2007). In vitro cell growth of marine archaeal-bacterial consortia during anaerobic oxidation of methane with sulfate. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 187–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01127.x

Olsen, A., Key, R. M., Van Heuven, S., Lauvset, S., Velo, A., Lin, X., et al. (2016). An internally consistent data product for the world ocean: the global ocean data analysis project, version 2 (GLODAPv2). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2016, 1–1.

Orphan, V. J., House, C. H., Hinrichs, K. U., Mckeegan, K. D., and Delong, E. F. (2001). Methane-consuming archaea revealed by directly coupled isotopic and phylogenetic analysis. Science 293, 484–487. doi: 10.1126/science.1061338

Orphan, V. J., Iii, W. U., Naehr, T. H., House, C. H., Hinrichs, K.-U., and Paull, C. K. (2004). Geological, geochemical, and microbiological heterogeneity of the seafloor around methane vents in the Eel River Basin, offshore California. Chem. Geol. 205, 265–289. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2003.12.035

Phillips, S. C., Hong, W.-L., Johnson, J. E., Fahnestock, M. F., and Bryce, J. G. (2018). Authigenic carbonate formation influenced by freshwater inputs and methanogenesis in coal-bearing strata offshore Shimokita, Japan (IODP site C0020). Mar. Petrol. Geol. 96, 288–303. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.06.007

Pierre, C., Blanc-Valleron, M.-M., Caquineau, S., März, C., Ravelo, A. C., Takahashi, K., et al. (2016). Mineralogical, geochemical and isotopic characterization of authigenic carbonates from the methane-bearing sediments of the Bering Sea continental margin (IODP Expedition 323, Sites U1343–U1345). Deep Sea Research Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 125, 133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2014.03.011

Prouty, N. G., Sahy, D., Ruppel, C. D., Roark, E. B., Condon, D., Brooke, S., et al. (2016). Insights into methane dynamics from analysis of authigenic carbonates and chemosynthetic mussels at newly-discovered Atlantic Margin seeps. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 449, 332–344. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2016.05.023

Reeburgh, W. S. (1976). Methane consumption in Cariaco Trench waters and sediments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 28, 337–344. doi: 10.1016/0012-821x(76)90195-3

Reeburgh, W. S. (2007). Oceanic methane biogeochemistry. Chem. Rev. 107, 486–513. doi: 10.1021/cr050362v

Rodriguez, N., Paull, C., and Borowski, W. (2000). “30. Zonation of authigenic carbonates within gas hydrate-bearing sedimentary sections on the Blake Ridge: offshore southeastern north America,” in Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Fremantle, 30.

Ruppel, C. D., and Kessler, J. D. (2017). The interaction of climate change and methane hydrates. Rev. Geophys. 55, 126–168. doi: 10.1002/2016rg000534

Schneider, R. R., Schulz, H. D., and Hensen, C. (2006). Marine Carbonates: Their Formation and Destruction. Berlin: Springer, 311–337.

Scholz, F., Hensen, C., Schmidt, M., and Geersen, J. (2013). Submarine weathering of silicate minerals and the extent of pore water freshening at active continental margins. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 100, 200–216. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2012.09.043

Schrag, D. P., Higgins, J. A., Macdonald, F. A., and Johnston, D. T. (2013). Authigenic carbonate and the history of the global carbon cycle. Science 339, 540–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1229578

Sivan, O., Schrag, D., and Murray, R. (2007). Rates of methanogenesis and methanotrophy in deep-sea sediments. Geobiology 5, 141–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2007.00098.x

Smith, J. P., and Coffin, R. B. (2014). Methane flux and authigenic carbonate in shallow sediments overlying methane hydrate bearing strata in Alaminos Canyon, Gulf of Mexico. Energies 7, 6118–6141. doi: 10.3390/en7096118

Snyder, G. T., Hiruta, A., Matsumoto, R., Dickens, G. R., Tomaru, H., Takeuchi, R., et al. (2007). Pore water profiles and authigenic mineralization in shallow marine sediments above the methane-charged system on Umitaka Spur, Japan Sea. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 54, 1216–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2007.04.001

Solomon, E. A., Spivack, A. J., Kastner, M., Torres, M. E., and Robertson, G. (2014). Gas hydrate distribution and carbon sequestration through coupled microbial methanogenesis and silicate weathering in the Krishna–Godavari basin, offshore India. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 58, 233–253. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2014.08.020

Stocker, T. F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S. K., Boschung, J., et al. (2014). Climate change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Suess, E. (2010). “Marine cold seeps,” in Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology, eds K. N. Timmis, T. McGenity, J. Roelof van der Meer, and V. de Lorenzo (Berlin: Springer), 185–203. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77587-4_12

Suess, E. (2018). “Marine cold seeps: background and recent advances,” in Hydrocarbons, Oils and Lipids: Diversity, Origin, Chemistry and Fate, ed. H. Wilkes (Berlin: Springer), 1–21. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-54529-5_27-1

Sun, X., and Turchyn, A. V. (2014). Significant contribution of authigenic carbonate to marine carbon burial. Nat. Geosci. 7, 201–204. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2070

Teichert, B., Johnson, J. E., Solomon, E. A., Giosan, L., Rose, K., Kocherla, M., et al. (2014). Composition and origin of authigenic carbonates in the Krishna–Godavari and Mahanadi Basins, eastern continental margin of India. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 58, 438–460. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2014.08.023

Thomas, H., Schiettecatte, L., Suykens, K., Kone, Y. M., Shadwick, E. F., Prowe, A., et al. (2008). Enhanced ocean carbon storage from anaerobic alkalinity generation in coastal sediments. Biogeosciences 6, 267–274. doi: 10.5194/bg-6-267-2009

Thullner, M., Dale, A. W., and Regnier, P. (2009). Global-scale quantification of mineralization pathways in marine sediments: a reaction-transport modeling approach. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 10:Q10012.

Torres, M. E., Hong, W.-L., Solomon, E. A., Milliken, K., Kim, J.-H., Sample, J. C., et al. (2020). Silicate weathering in anoxic marine sediment as a requirement for authigenic carbonate burial. Earth-Sci. Rev. 200:102960. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.102960

Treude, T., Orphan, V., Knittel, K., Gieseke, A., House, C. H., and Boetius, A. (2007). Consumption of methane and CO2 by methanotrophic microbial mats from gas seeps of the anoxic Black Sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 2271–2283. doi: 10.1128/aem.02685-06

Ussler III, W., and Paull, C. K. (2008). Rates of anaerobic oxidation of methane and authigenic carbonate mineralization in methane-rich deep-sea sediments inferred from models and geochemical profiles. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 266, 271–287. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2007.10.056

Wallmann, K., and Aloisi, G. (2012). “The Global carbon cycle: geological processes,” in Fundamentals of Geobiology, eds A. H. Knoll, D. E. Canfield, and K. O. Konhauser (Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.), 20–35. doi: 10.1002/9781118280874.ch3

Wallmann, K., Aloisi, G., Haeckel, M., Obzhirov, A., Pavlova, G., and Tishchenko, P. (2006). Kinetics of organic matter degradation, microbial methane generation, and gas hydrate formation in anoxic marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 3905–3927. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2006.06.003

Wallmann, K., Aloisi, G., Haeckel, M., Tishchenko, P., Pavlova, G., Greinert, J., et al. (2008). Silicate weathering in anoxic marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 2895–2918. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.03.026

Wallmann, K., Pinero, E., Burwicz, E., Haeckel, M., Hensen, C., Dale, A., et al. (2012). The global inventory of methane hydrate in marine sediments: a theoretical approach. Energies 5, 2449–2498. doi: 10.3390/en5072449

Wasmund, K., Mußmann, M., and Loy, A. (2017). The life sulfuric: microbial ecology of sulfur cycling in marine sediments. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 9, 323–344. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12538

Wehrmann, L., Ockert, C., Mix, A., Gussone, N., Teichert, B., and Meister, P. (2016). Repeated occurrences of methanogenic zones, diagenetic dolomite formation and linked silicate alteration in southern Bering Sea sediments (Bowers Ridge, IODP Exp. 323 Site U1341). Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 125, 117–132. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.09.008

Wehrmann, L. M., Risgaard-Petersen, N., Schrum, H. N., Walsh, E. A., Huh, Y., Ikehara, M., et al. (2011). Coupled organic and inorganic carbon cycling in the deep subseafloor sediment of the northeastern Bering Sea Slope (IODP Exp. 323). Chem. Geol. 284, 251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2011.03.002

Wu, Z., Zhou, H., Ren, D., Gao, H., and Li, J. (2016). Quantifying the sources of dissolved inorganic carbon within the sulfate-methane transition zone in nearshore sediments of Qi’ao Island, Pearl River Estuary, Southern China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 59, 1959–1970. doi: 10.1007/s11430-016-0057-0

Wurgaft, E., Findlay, A. J., Vigderovich, H., Herut, B., and Sivan, O. (2019). Sulfate reduction rates in the sediments of the Mediterranean continental shelf inferred from combined dissolved inorganic carbon and total alkalinity profiles. Mar. Chem. 211, 64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2019.03.004

Yoshinaga, M. Y., Holler, T., Goldhammer, T., Wegener, G., Pohlman, J. W., Brunner, B., et al. (2014). Carbon isotope equilibration during sulphate-limited anaerobic oxidation of methane. Nat. Geosci. 7:190. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2069

Zhang, Y., Luo, M., Hu, Y., Wang, H., and Chen, D. (2019). An areal assessment of subseafloor carbon cycling in cold seeps and hydrate-bearing areas in the northern south china sea. Geofluids 2019, 1–14. doi: 10.1155/2019/2573937

Zopfi, J., Ferdelman, T. G., Fossing, H., Amend, J. P., Edwards, K. J., Lyons, T. W. (2004). “Distribution and fate of sulfur intermediates—sulfite, tetrathionate, thiosulfate, and elemental sulfur—in marine sediments,” in Sulfur Biogeochemistry – Past and Present, eds J. P. Amend, K. J. Edwards, and T. W. Lyons (Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America).

Keywords: marine carbon cycle, marine methane fluxes, sulfate methane transition zone, anaerobic methane oxidation, methane derived authigenic carbonates, dissolved inorganic carbon, sediment carbon budget, ocean acidification

Citation: Akam SA, Coffin RB, Abdulla HAN and Lyons TW (2020) Dissolved Inorganic Carbon Pump in Methane-Charged Shallow Marine Sediments: State of the Art and New Model Perspectives. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:206. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00206

Received: 08 September 2019; Accepted: 16 March 2020;

Published: 15 April 2020.

Edited by:

Laura Anne Bristow, University of Southern Denmark, DenmarkReviewed by:

Bo Thamdrup, University of Southern Denmark, DenmarkCopyright © 2020 Akam, Coffin, Abdulla and Lyons. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sajjad A. Akam, c2FqamFkYUB0YW11Y2MuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.