- 1Key Laboratory of Marine Ecosystem and Biogeochemistry, State Oceanic Administration & Second Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Hangzhou, China

- 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

- 3Key Laboratory of Marine Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao, China

- 4Ningbo Academy of Oceanology and Fishery, Ningbo, China

- 5Ocean College, Zhejiang University, Zhoushan, China

- 6State Key Laboratory of Satellite Ocean Environment Dynamics, Hangzhou, China

Due to the high toxicity in aquatic food chain, the toxic effects of methylmercury (MeHg) on organisms have caused widespread concerns, but little has been reported on its effects on marine fish. The acute and sub-lethal toxicities of MeHg chloride to an important aquaculture species in southeast coast of China - large yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea) embryos and larvae were investigated in this study. Acute toxicity tests showed that the 48-h LC50 values of methylmercury to fish embryos and larvae were 28.39 (21.33–33.98) and 18.27 (11.33–29.29) μg L−1, respectively. The 96-h LC50 value for larvae was 9.28 (4.41–14.49) μg L−1, which indicated that fish larvae were more sensitive to MeHg than the embryos. On the other hand, MeHg exposure induced delayed hatching process, lower yolk absorption rate, higher morphological malformations at concentrations ≥ 1 μg L−1, and caused higher larvae heart rate, lower survival and hatching success at concentrations ≥ 5, 10, and 20 μg L−1, respectively. The results suggested that the hatching, survival and growth of the large yellow croaker during the early life stages may serve as sensitive biomarkers for marine MeHg pollution.

Introduction

Mercury (Hg) has been shown to be a widespread and persistent metallic pollutant in estuarine and coastal waters all over the world (Satoh, 2000). Mercury in the environment mainly comes from anthropogenic activities such as fire coal, electric power generation facilities, chloralkali production, waste incineration and other industrial activities (UNEP, 2002; Trasande et al., 2005; Devlin, 2006). In aquatic environment, mercury can be converted into various forms such as metallic elements, inorganic salts and organic compounds (Lee et al., 2017). Among these forms, methylmercury (MeHg) is the most toxic and it is mainly produced by sulfate-reducing bacteria from precipitated mercury sulfate compounds in marine ecosystems (Gochfield, 2003). MeHg can be readily absorbed by aquatic organisms and its concentration increases with the increasing trophic levels due to biomagnification, which ultimately threatens the health of marine biota and the stability of the ecosystem (Jewett et al., 2003).

Given the ability of MeHg to form complexes with amino acid cysteine, which can result in high mobility in organisms (Ceccatelli et al., 2010), MeHg is toxic to multiple organs and systems (e.g., brain, kidneys, swim bladder, cardiovascular system, immune system, and reproductive system) (Syversen and Kaur, 2012). For example, it can induce oxidative damage, cause neurotoxicity and genotoxicity (Cambier et al., 2012; Farina and Aschner, 2019), MeHg also causes some protein down-regulation, affecting the normal development of organs (e.g., swim bladder) (Cuello et al., 2012). MeHg has a reaction center with a positive charge in the Hg atom, therefore, it has a higher reactivity to thiols and selenols groups. Such interaction can alter the structure and function of some proteins as well as the redox state of low molecular antioxidants, leading to MeHg-induced oxidative stress (Farina et al., 2011). Early life stages (ELSs) of fish are extremely sensitive to contaminants, low concentrations of contaminants may not be sufficiently poisonous to adult fish but it can cause harmful impacts on embryos and larvae (Jezierska et al., 2009). Numerous studies have confirmed that MeHg has adverse effects on the early development of fish, leading to growth retardation, increased mortality, impaired cardiac function, morphological abnormalities, genetic, and protein expression disorders (Hassan et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2019).

Large yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea) is one of the most important commercial fish species mainly distributed in the southeast coastal waters of China (Huang et al., 2019). However, the population of large yellow croaker has drastically declined in the past decades (Xu and Liu, 2007). In addition to overfishing, marine contaminants such as heavy metal are also considered to be the other important factor for the decline of fishery resources in the East China Sea (Zhao et al., 2015). The concentration of MeHg ranged from 0.00005–0.00022 μg L−1 in the surface seawater of the northern South China Sea (Fu et al., 2010), and the value is 24.9 ng g−1 in the large yellow croaker in the East China Sea (Xia et al., 2013). In order to further understand the toxicological effects of MeHg on ELSs of large yellow croaker and its external response, toxicity test was conducted wherein fish embryos and larvae were exposed to 0–80 μg L−1 MeHg. Considering the facts mentioned above, this study was performed with the following purpose: (1) to determine the acute toxicity of MeHg to large yellow croaker embryos and larvae; (2) to investigate the effects of MeHg on hatching, development and growth of fish embryos and larvae.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Methylmercury Stock Solution

Methylmercury chloride (CH3HgCl, purity, >99.5%, CAS No: 115-09-3, Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., United States) was initially dissolved in deionized water to achieve a concentration of 500 mg L−1 and further diluted to specific concentrations with filtered seawater for exposure tests. The methylmercury stock solution was stored at 4°C.

Test Organisms

The experiment was conducted in accordance with the standards of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Fish, Short-term Toxicity Test on Embryo and Sac-fry Stages” (OECD, 1998). Large yellow croaker embryos and larvae were obtained from Institute of Marine and Fisheries Research of Ningbo, China. The fertilized eggs were placed in a hatching bucket (density, 800 eggs L−1; photoperiod, 14L:10D; temperature, 18 ± 1°C; pH, 8.1 ± 0.1; salinity, 28 ± 1; dissolved oxygen, 7.5 ± 0.2 mg L−1; MeHg, 0.00006 ± 0.00003 mg L−1; hardness, 6124.6 ± 272.3 mg L−1 as CaCO3) for 2 h before the experiment. During this period, dead embryos sank to the bottom of the hatching bucket when the normal embryos floated on the water. Only normal developing embryos and larvae were used for toxicity tests.

Exposure Conditions

Acute Toxicity Test on Embryos

One hundred healthy embryos were selected randomly and transferred into each of 28 experimental beakers (1,000 mL), which were placed randomly in the laboratory with a constant temperature of 18 ± 1°C. Six nominal concentrations (1, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 80 μg L−1) and one control were set up, four replicates were set for each concentration. The experiment lasted continuously for 48 h without changing the seawater. The embryo development was observed and recorded every 6 h, and the dead embryos were removed promptly. During the test, embryos sank to the bottom of the beaker and turned gray were considered to be dead. The mortality obtained in the test was used for calculating LC50 values of methylmercury for the embryos.

Acute Toxicity Test on Larvae

Similar test method as acute toxicity test on embryos was applied for larvae. Six nominal concentrations (4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 40 μg L−1) and one control were set up, four replicates were set for each concentration. Hundred newly hatched larvae were selected randomly and transferred into each of the 28 experimental beakers (1,000 mL). The experiment lasted continuously for 96 h without changing the seawater. Larvae sank to the bottom of the beaker, turned gray and had no response to gentle touch were considered to be dead. The mortality obtained in the test was used for calculating LC50 values of mercury for larvae.

Toxicity Test on Embryonic-Larval Development and Survival

Based on the LC50 values derived from the acute toxicity tests, six nominal concentrations of MeHg: 0 (control), 0.2, 1, 5, 10, and 20 μg L−1 were set up. Hundred healthy embryos developed to the blastocyst stage were selected randomly and transferred to the experimental beakers. Dead individuals and the uneaten bait were removed with pipettes to prevent contamination of the experimental solutions. After hatching, two-thirds of the test solution in each beaker was replaced daily with the same concentration of MeHg. The test was performed for 6 days.

Survival and growth experiment

Four replicates were set for each concentration in the survival and growth experiments. During this experiment, no sampling was carried out to avoid the impact of sampling on experimental organisms to the greatest extent. Four biological parameters were investigated: (1) Cumulative hatching rate which was defined as the percentage of the cumulative number of larvae hatched during the test to the number of initially stocked embryos (100) in each beaker; (2) Median effective time for hatch (MET), defined as the time (h) required for 50% of individuals in different treatment groups or control groups to hatch. The time points of 22, 26, 28, 30, and 34 h post fertilization (hpf) were selected, and the number of hatching individuals was counted in each beaker. The method by Dave and Xiu (1991) was used to calculate the METs in different exposure concentrations. METs were used to evaluate the effect of methylmercury on incubation time; (3) Cumulative mortality was defined as the percentage of dead embryos and larvae throughout the tests to the number of initially stocked embryos (100) in each beaker; (4) Cumulative morphological abnormality of larvae was defined as the percentage of the total number of abnormally developed larvae by the cumulative number of larvae hatched during the test. Abnormal individuals were observed and recorded every 4 h after hatching by stereo microscope and camera system (Nikon-SMZ1000; digital video camera, Nikon-DS 5M; Software, ACT-2U; Tokyo, Japan). Abnormally developed survivors at the termination of each treatment, if any, were also checked and included.

Development experiment

In order to observe heartbeat and growth of the embryos and larvae, one set of development tests were carried out for sampling, three replicates were used for each concentration. Three biological parameters were investigated in developmental experiments: (1) heartbeat of embryos and larvae, three samples from the beaker at the heartbeat stage embryos, newly-hatched larvae (0 day post hatching, dph) and larvae 3 days post hatching (3 dph) were randomly selected, and the heart rates of embryos and larvae were counted; Heartbeat counting was taken with Nikon camera system by a 30-s video recording, and then counted by slow playback to reduce experimental error; (2) Body length, three larvae were taken from each beaker at 0 dph and the end of experiment to measure the body length of the newly-hatched larvae (L0, mm; Figure 3B) and the final body length (LT, mm), respectively; (3) Yolk absorption rate (R) which was defined as the average daily change in the yolk sac size over the course of the test in each tank. The calculating formula is R = (V0-Vt)/t, where V0 and Vt (mm3) are the initial and final yolk sac sizes, respectively, and t is the exposure time (h) of the test. The yolk sac size is calculated by the formula: V = π × a × b2/6, where a and b (mm) are the major axis and minor axis of the yolk sac, respectively. The measurement was conducted with a microscope (Nikon-ECLIPSE 50i, Tokyo, Japan) or stereo microscope and ACT-2U software (Tokyo, Japan). Before hatching, fish embryos were observed every 6 h to calculate embryo mortality, hatching rate, incubation time and heart rate (heartbeat period). The larvae survival rate, deformity rate, heart rate and other indicators were observed and calculated every 12 h after hatching.

Solution Sampling and Chemical Analyses

To determine the concentration of MeHg in the test solutions, water samples were taken for analysis at the end of test in acute toxicity tests, and every day when changing water in embryonic-larval test. Test solutions were measured using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Agilent 6890/5973; United States). In all tests, measured concentrations fell within the range of 80–120% of their nominal concentrations, which was required for toxicity tests (OECD, 1998).

Data Treatment and Statistical Analysis

The LC50 values of MeHg to large yellow croaker embryos and larvae were determined by a probit analysis (Finney, 1971). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov one-sample test was used to test the normality of the hypothesis and the Levene test was used to test the assumed homogeneity of the variance. If any of the assumptions were not met, the data would be normalized by logarithmic transformation before analysis of variance (yolk absorption rate data). If both hypotheses were met, the data would be analyzed by one-way ANOVA and then the differences between treatment and control groups were compared by Dunnett's multiple comparison test (p < 0.05). All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). The SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Software GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., California, USA) was used to generate graphs.

Results

LC50 Values of MeHg to Embryos and Larvae

The 48-h LC50 values of MeHg to large yellow croaker embryos was 28.39 (21.33–33.98) μg L−1 (with 95% confidence limits), while the 48-h and 96-h LC50 values of MeHg to larvae were 18.27 (11.33–29.29) and 9.28 (4.41–14.49) μg L−1, respectively.

Subchronic Toxicity to Embryos and Larvae

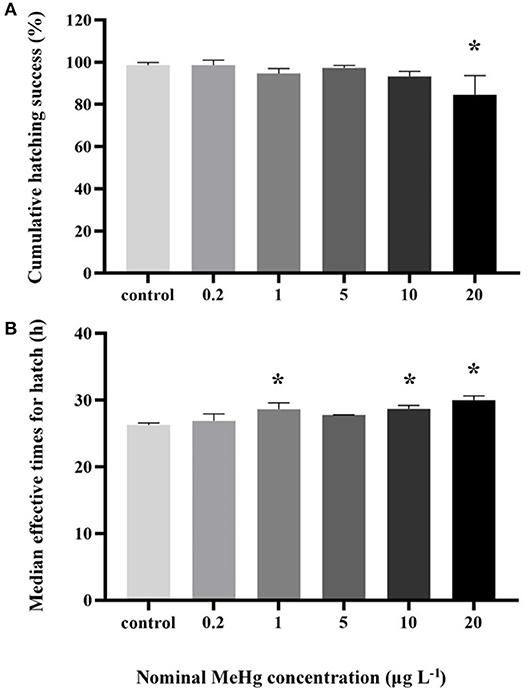

The cumulative hatching rate was significantly affected by MeHg exposure (ANOVA, p < 0.05). It was significantly decreased in the 20 μg L−1 treatment (85%) compared to the control (99%; Dunnett's test, p < 0.05; Figure 1A). MeHg exposure also had a significant impact on the METs of large yellow croaker embryo (ANOVA, p < 0.05). It was significantly decreased in the 1.0 (28.64 h), 10.0 (28.68 h), 20.0 (30.00 h) μg L−1 treatments with respect to the control (26.28 h; Dunnett's test, p < 0.05; Figure 1B).

Figure 1. (A) Cumulative hatching success and (B) METs of the large yellow croaker embryos by MeHg exposure (mean ± S.D.; n = 4; *indicated significant difference compared to the control group at p < 0.05).

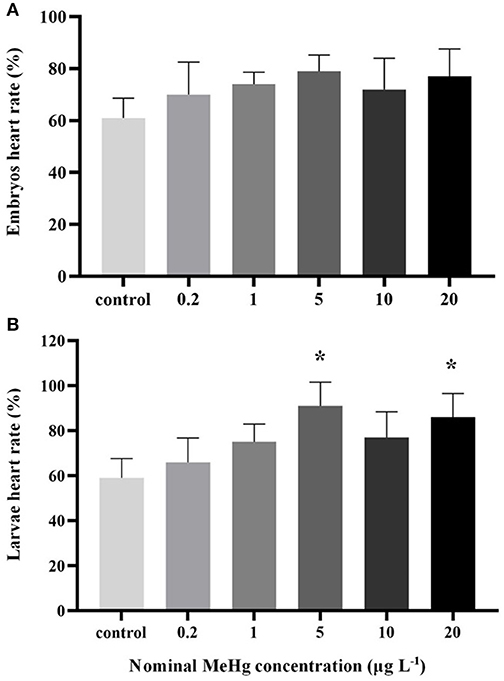

MeHg exposure had no significant effect on embryo's heart rate (ANOVA, p > 0.05; Figure 2A), but the heart rate of larvae was significantly increased in the 5 μg L−1 (91 beats min−1) and 20 μg L−1 (86 beats min−1) treatments compared to the control (59 beats min−1; ANOVA Dunnett's test, p < 0.05; Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Heart rate of the large yellow croaker (A) embryos and (B) larvae by MeHg exposure (mean ± S.D.; n = 3; *indicated significant difference compared to the control group at p < 0.05).

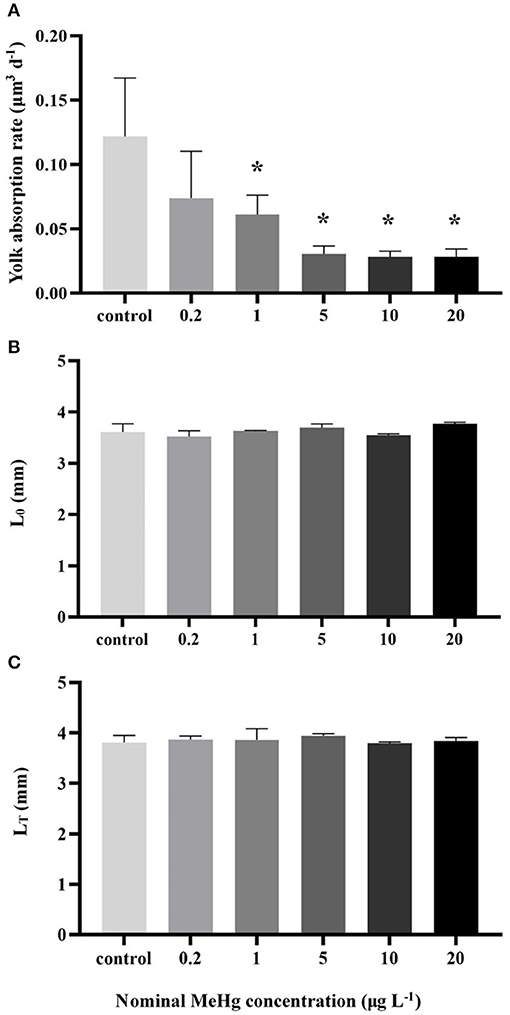

The yolk absorption rate was significantly decreased at the concentration ≥1 μg L−1 (0.03–0.06 μm3 d−1) compared to the control (0.12 μm3 d−1; ANOVA Dunnett's test, p < 0.05; Figure 3A); On the other hand, MeHg had no significant effect on the LT of larvae (ANOVA; p> 0.05; Figure 3C).

Figure 3. (A) Yolk absorption rate, (B) body length of newly hatched larvae (L0) and (C) final body length (LT) of the larvae by MeHg exposure (mean ± S.D.; n = 3; * indicated significant difference compared to the control group at p < 0.05).

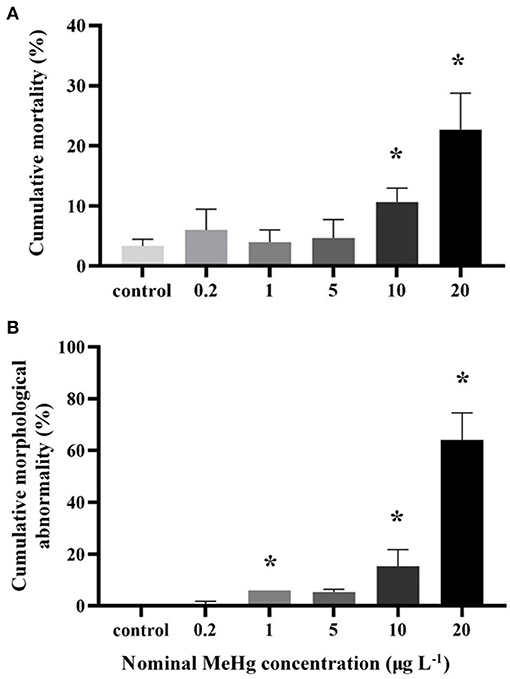

MeHg exposure also significantly affected the cumulative mortality of the embryos and larvae (ANOVA, p < 0.05; Figure 4A). The mortality was significantly increased in the 10 μg L−1 (11%) and 20 μg L−1 (23%) treatments compared to the control (3%; Dunnett's test, p < 0.05; Figure 4A).

Figure 4. (A) Cumulative mortality and (B) cumulative morphological abnormality of the large yellow croaker embryos and larvae by MeHg exposure (mean ± S.D.; n = 4; * indicated significant difference compared to the control group at p < 0.05).

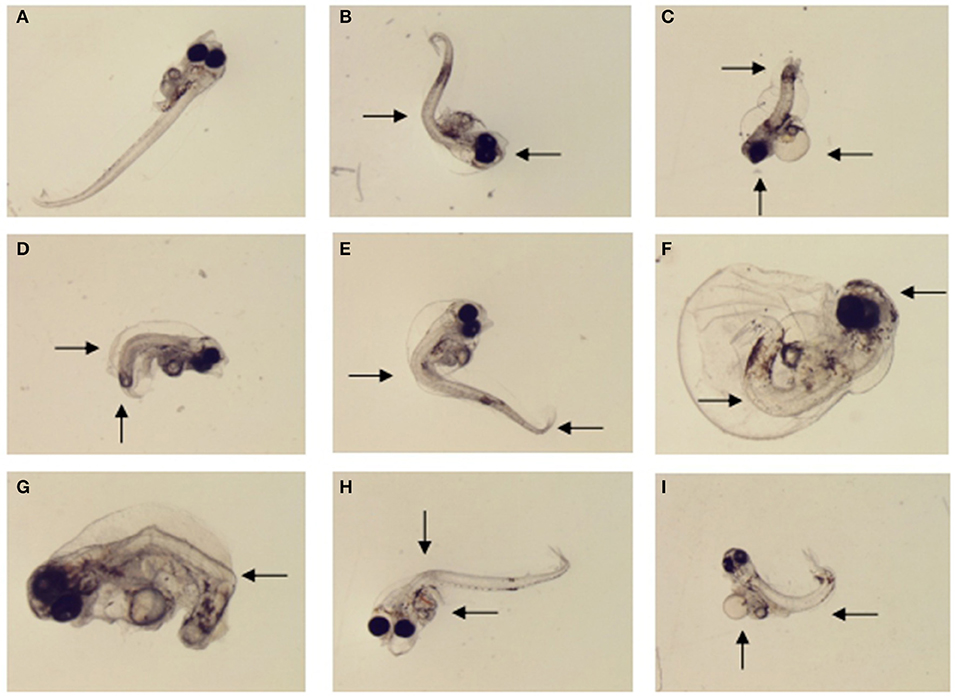

The morphological abnormality significantly increased in the 1.0 μg L−1 (6.0%), 10.0 μg L−1 (15.3%), and 20.0 μg L−1 (64.0%) treatments compared to the control (0; Dunnett's test, p < 0.05; Figure 4B). The level of larval morphological abnormality observed in the test included spinal deformity, tail curl, tail degeneration, pericardial edema and fin erosion (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Morphological malformations of the large yellow croaker larvae by MeHg exposure in the sub-chronic toxicity test: (A) normally developed larvae (control), (B) eye fusion and spinal deformity (20 μg L−1), (C) head dysplasia, fin rot and tail hypoplasia (40 μg L−1), (D) spinal deformity and tail hypoplasia (1 μg L−1), (E) spinal deformity and tail bending (5 μg L−1) (F) eye fusion, fin rot and spinal deformity (40 μg L−1), (G) body color abnormalities and tail hypoplasia (10 μg L−1), (H) visceral hemorrhage and spinal deformity (10 μg L−1), (I) periventricular edema and spinal deformity (10 μg L−1).

Discussion

It is an indisputable fact that relative low dose of MeHg could cause death, genotoxicity, neurotoxicity, cytotoxicity, immunotoxicity, and endocrine toxicity to fish (Cambier et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2018; Farina and Aschner, 2019). Because MeHg causes cell damage by over-producing ROS or reducing oxidative defense, and binding to tubulin leads to cytoskeletal changes and inhibition of the Na+/Ka+ pump and protein synthesis, eventually leading to impaired cell function or abnormal cell death (Hare and Atchison, 1994; Orrenius et al., 2003). In the present study, the 48-h LC50 of large yellow croaker embryos and the 48-h and 96-h LC50 of the larvae were lower than most of the reported fish species, indicating that ELSs of large yellow croaker is particularly sensitive to MeHg exposure. Moreover, MeHg can affect a variety of biological processes related to embryonic hatching and larval development, including placental development, nutrient absorption and apoptosis, etc. (Hare and Atchison, 1994; Latif et al., 2001).

Acute Toxicity of MeHg to Embryos and Larvae

The present study showed that the 48-h LC50 value of MeHg (28.39 μg L−1) to embryos of large yellow croaker was generally lower than fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas, 71 μg L−1; Devlin, 2006), killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus, 50 μg L−1; Sharp and Neff, 1982), zebrafish (Danio rerio, 90 μg L−1; Cambero and Calvo, 2010) and coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch, 54–71 μg L−1; Devlin and Mottet, 1992), but higher than the Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus, 15.3 μg L−1; Ren et al., 2019). While the 48-h LC50 (18.27 μg L−1) and 96-h LC50 (9.28 μg L−1) values of MeHg to large yellow croaker larvae was much lower than larvae of catfish (Clarias batrachus, 48-h LC50, 668 μg L−1, 96-h LC50, 430 μg L−1; Kirubagaran and Joy, 1988), lamprey (Petromyzon marinus, 48-h LC50, 88–151 μg L−1, 96-h LC50, 48–88 μg L−1; Mallatt et al., 1986), rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss, 48-h LC50, 37–66 μg L−1, 96-h LC50, 24–42 μg L−1; Wobeser, 1975; Mozhdeganloo et al., 2015), blue gourami (Trichogaster trichopterus, 48-h LC50, 94 μg L−1, 96-h LC50, 89 μg L−1; Roales and Perlmutter, 1974) and Japanese flounder (48-h LC50, 20.7 μg L−1, 96-h LC50, 16.3 μg L−1). Based on these results, large yellow croaker embryos and larvae may be more sensitive to MeHg than most other fish species mentioned above. On the other hand, when conducting indoor controlled experiments, different studies often set different experimental conditions depending on the species tested. Due to the confounding effects of experimental conditions, there are some controversies about the sensitivity of different species to toxicants (Ren et al., 2019). External environmental factors such as temperature, salinity, hardness, pH and DOC could greatly affect the toxicity of MeHg to fish (Pack et al., 2014). For example, the LC50 of MeHg on lamprey larvae decreased with increasing water temperature (Mallatt et al., 1986); while the LC50 of Hg on nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) decreased with increasing hardness in water (Ishikawa et al., 2007). In this experiment, the laboratory conditions were controlled most suitable for the growth and survival of large yellow croaker, and other experimental controls may be the most suitable experimental conditions for other species. Therefore, we should also consider the experimental conditions when comparing with other results.

It could also be inferred from the present study that the survival of large yellow croaker was more sensitive to MeHg exposure at larval stage than embryonic (48-h LC50: 28.39 vs. 18.27 μg L−1). This result is in consistence with the general view that fish embryos are not as sensitive as larvae exposed to contaminants probably due to the protective effect of the embryonic membrane (Jezierska et al., 2009). However, there are some opposite phenomena. For example, Japanese flounder embryos are more sensitive than larvae when exposed to heavy metals such as mercury and cadmium (Huang et al., 2010; Ren et al., 2019). For such species, the chorions during early embryogenesis may have not yet hardened to function as barriers to effectively protect the embryos from exposure to toxicants (Herrmann, 1993). Additionally, the chorions during late embryogenesis will gradually break and thereby increase the susceptibility of the embryos to waterborne toxicants (Ren et al., 2019). Therefore, the sensitivity of embryos to toxicants could be related to the processes by which the chorions biologically function in response to the waterborne toxicants entering the embryos (Sharp and Neff, 1982).

Toxicity of MeHg to Hatching Process of Embryos

In the present study, the cumulative hatching rate in the highest MeHg concentration (20 μg L−1) was significantly lower than that in the lower concentrations. One possible reason for the decline in hatching rate of embryos is that metals enter the egg membrane through osmosis, causing disturbances in structure and function such as mitotic divisions during embryonic development, resulting in reduced hatching success (Latif et al., 2001; Witeska et al., 2014). For example, in walleye (Stizostedion vitreum), MeHg even at nanogram levels could affect the transformation of the germinal layers into various organs of the embryos, thus affecting the embryo development and eventually reducing the hatching success (Latif et al., 2001). However, Japanese flounder embryos exposed to MeHg below LC50 values did not show the reduced cumulative hatching rate, probably these concentrations may not reach the threshold of affecting the hatchability of the Japanese flounder embryos (Ren et al., 2019).

The METs were significantly increased by MeHg exposure, implying that MeHg is likely to cause a delay in the hatching of large yellow croaker embryos once it reaches a certain level. Hatching process of fish embryos is a combination of osmotic, biochemical (enzymatic) and biophysical (mechanical) mechanisms (Yamagami, 1981). MeHg has been proved to inhibit the activity of hatching enzymes for egg shell disintegration, and thus leading to the inability of the emerging larvae to break the egg shell and consequently result in delayed hatching (Hallare et al., 2005). Moreover, MeHg could inhibit the synthesis of proteins associated with the development of embryo chorions, which also delay the development and hatching of fish (Cuello et al., 2012). In addition, MeHg exposure may induce oxidative stress, which constrain the function of energy metabolism and enzyme activities and eventually retards the hatching process (Gonzalez et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2018).

Toxicity of MeHg to Heart Rate of Embryos and Larvae

In this experiment, MeHg exposure significantly increased the larvae heart rate but did not affect embryonic heart rate. An important mechanism for the toxicity of MeHg is the Ca2+ homeostasis disorder in cells, as Ca2+ plays an important role in maintaining normal rhythm of the heart, unbalanced Ca2+ concentration can cause severe arrhythmias (Ceccatelli et al., 2010). MeHg exposure affects the expression of related protein associated with Ca2+ homeostasis (e.g., Calreticulin), resulting in elevated Ca2+ concentrations (Cuello et al., 2012). Moreover, MeHg affects the normal physiological function of the larvae heart which is also an important reason for heart rate change (Weis et al., 1981). MeHg could lead to abnormal cardiac ventricular differentiation, ventricular defect and other cardiac malformations in killifish, resulting in incomplete cardiac development (Jezierska et al., 2009). In addition, MeHg was also reported to cause blood accumulation in the fathead minnow heart region, thus leading to defects in cardiac output (Devlin, 2006). MeHg was reported to play roles in nerve interference, and acetylcholinesterase could be inhibited by MeHg (Hallare et al., 2006). MeHg may cause a series of cascading responses mentioned above which eventually lead to changes in heart rate of larvae.

Toxicity of MeHg to the Growth and Development of Embryos and Larvae

MeHg was reported to affect the growth of various fish species (Mozhdeganloo et al., 2015). The yolk sac is very important to newly hatched larvae as it is the only nutrients source before the larvae open their mouth, and the changes in yolk sac absorption can directly affect the growth of fish embryo-larvae stage (Huang et al., 2010). In this study, the yolk sac absorption rate of the larvae was decreased significantly by MeHg, implying that methylmercury inhibits energy expenditure. Similarly, MeHg inhibited the absorption rate of yolk sac in newly hatched Japanese flounder larvae (Ren et al., 2019). Generally, toxic heavy metals can reduce the nutrient absorption, increase the extra energy consumption for detoxification, or disrupt the expression of growth hormone and inhibit the growth of larvae (Cao et al., 2012). However, the final body length of larvae was not affected by MeHg, which is contrary to most experimental results (Houck and Cech, 2004). One possible reason is that although the body length of the larvae was not affected by MeHg, the body weight was probably reduced. We suspect that the body weight of larvae in the high-concentration group may be reduced accordingly due to poor nutrient absorption, but this still requires proof from subsequent accurate measurement.

The morphological deformities of fish at ELSs due to the exposure to toxicants, particularly heavy metals and POPs, have been well investigated and documented (Jezierska et al., 2009; Witeska et al., 2014). For example, Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) embryos showed a series of abnormalities such as small eyes with reduced pigmentation exposed to MeHg solution ≤ 80 mg L−1 (Heisinger and Green, 1975; Dial, 1978). Zebrafish larvae exposed to MeHg at 30 μg L−1 showed abnormal eye development, spinal deformity, tail and fin flexure (Samson and Shenker, 2000). In the present study, MeHg induced spinal deformity, tail bending and hypoplasia, swelling head, abnormal pigmentation, and fin erosion. Spine and tail deformity are the most common types of deformities observed during the test. One of the toxic mechanisms of MeHg is suppression of protein synthesis (Cheung and Verity, 1985), as MeHg have been proven to induce a variety of protein expression down-regulation related to morphological changes, such as body axis bending and mandibular deformity (Cuello et al., 2012). This is probably due to the fact MeHg exposure could induce degeneration of rough endoplasmic reticulum and down regulation of ribosomal protein expression (Cuello et al., 2012), because endoplasmic reticulum is an important place for protein synthesis, any degradation of protein related to morphological development in early life stages of fish may finally result in deformation. On the other hand, MeHg exposure also causes significant up-regulate of ribosome proteins (such as rpl7a) associated with apoptosis (Cuello et al., 2012). Apoptosis is accompanied by some biological processes such as cell death, gastrulation and tissue interaction which can lead to abnormal morphology of developing fish larvae to some extent (Orrenius et al., 2003). Finally, other factors such as MeHg-induced oxidative stress, inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity, and influence of immune gene expression may also be responsible for the morphological abnormalities of fish (Wu et al., 2018). In addition, high deformity rates are often accompanied by low survival rates, suggesting that malformation in the ELSs is likely to increase larval mortality.

Conclusion

This study evaluated the toxic effects of MeHg on large yellow croaker embryos and larvae. The results revealed that the larval stage of large yellow croaker was more sensitive than embryonic to MeHg exposure at 18°C and 28 psu under laboratory conditions. Moreover, MeHg induced detrimental impacts across various biological process including low hatchability, delayed hatch, reduced yolk sac absorption rate, higher mortality and morphological malformation.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

WH and LC executed the project and designed the experiment. FW, XiX, QC, LH, BT, and XuX conducted the experiments. WH, XY, LC, and SD analyzed the experimental results and wrote the manuscript. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFD0900901), Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41306112; 41406167; 21307019), Basic Scientific Research of SIO, China (Nos. JG1717, JG1718). National Key Basic Research Program (Contract No. 2015CB453302), National Key Technology Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the China (2015BAD08B01), State Key Laboratory of Satellite Ocean Environment Dynamics (Nos. SOEDZZ1902; SOEDZZ1803), China-APEC Cooperation Fund (No. 2029901), Joint Advanced Marine and Ecological Studies in the Bay of Bengal and the eastern equatorial Indian Ocean (JAMES). Basic Scientific Research of SIO, China (Nos. JG1717, JG1718).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. H. F. Jiao and Dr. S. W. Xu for their help in providing facilities and conveniences for the present study.

References

Cambero, J. P. G., and Calvo, A. C. (2010). Lethal and sublethal effects of methylmercury to zebrafish embryos. Toxicol. Lett. 196:S118. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.03.415

Cambier, S., Gonzalez, P., Mesmer-Dudons, N., Brèthes, D., Fujimura, M., and Bourdineaud, J. P. (2012). Effects of dietary methylmercury on the zebrafish brain: histological, mitochondrial, and gene transcription analyses. Biometals 25, 165–180. doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9494-6

Cao, L., Huang, W., Shan, X., Ye, Z., and Dou, S. (2012). Tissue-specific accumulation of cadmium and its effects on antioxidative responses in Japanese flounder juveniles. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 33, 16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2011.10.003

Ceccatelli, S., Daré, E., and Moors, M. (2010). Methylmercury-induced neurotoxicity and apoptosis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 188, 301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.04.007

Cheung, M. K., and Verity, M. A. (1985). Experimental methyl mercury neurotoxicity: locus of mercurial inhibition of brain protein synthesis in vivo and in vitro. J. Neurochem. 44, 1799–1808. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb07171.x

Cuello, S., Ximénez-Embún, P., Ruppen, I., Schonthaler, H. B., Ashman, K., Madrid, Y., et al. (2012). Analysis of protein expression in developmental toxicity induced by MeHg in zebrafish. Analyst 137:5302. doi: 10.1039/c2an35913h

Dave, G., and Xiu, R. Q. (1991). Toxicity of mercury, copper, nickel, lead, and cobalt to embryos and larvae of zebrafish, Brachydanio rerio. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 21, 126–134. doi: 10.1007/BF01055567

Devlin, E. W. (2006). Acute toxicity, uptake and histopathology of aqueous methyl mercury to fathead minnow embryos. Ecotoxicology 15, 97–110. doi: 10.1007/s10646-005-0051-3

Devlin, E. W., and Mottet, N. K. (1992). Embryotoxic action of methyl mercury on coho salmon embryos. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 49, 449–454. doi: 10.1007/BF01239651

Dial, N. A. (1978). Methylmercury: some effects on embryogenesis in the Japanese medaka, Oryzias latipes. Teratology 17, 83–91. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420170116

Farina, M., and Aschner, M. (2019). Glutathione antioxidant system and methylmercury-induced neurotoxicity: an intriguing interplay. BBA Gen. Subj. 1863:129285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.01.007

Farina, M., Aschner, M., and Rocha, J. B. T. (2011). Oxidative stress in MeHg induced neurotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 256, 405–417. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.05.001

Fu, X. W., Feng, X. B., Zhang, G., Xu, W. H., Li, X. D., Yao, H., et al. (2010). Mercury in the marine boundary layer and seawater of the South China Sea: concentrations, sea/air flux, and implication for land outflow. J. Geophys. Res. 115, 620–631. doi: 10.1029/2009JD012958

Gochfield, M. (2003). Cases of mercury exposure, bioavailability, and absorption. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 56, 174–179. doi: 10.1016/S0147-6513(03)00060-5

Gonzalez, P., Dominique, Y., Massabuau, J. C., Boudou, A., and Bourdineaud, J. P. (2005). Comparative effects of dietary methylmercury on gene expression in liver, skeletal muscle, and brain of the zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 3972–3980. doi: 10.1021/es0483490

Hallare, A., Nagel, K., Köhler, H. R., and Triebskorn, R. (2006). Comparative embryotoxicity and proteotoxicity of three carrier solvents to zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 63, 378–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2005.07.006

Hallare, A. V., Schirling, M., Luckenbach, T., Köhler, H. R., and Triebskorn, R. (2005). Combined effects of temperature and cadmium on developmental parameters and biomarker responses in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. J. Therm. Biol. 30, 7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2004.06.002

Hare, M. F., and Atchison, W. D. (1994). Mechanisms of methylmercury-induced neurotoxicity. FASEB J. 8, 622–629. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.9.7516300

Hassan, S. A., Moussa, E. A., and Abbott, L. C. (2012). The effect of methylmercury exposure on early central nervous system development in the zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryo. J. Appl. Toxicol. 32, 707–713. doi: 10.1002/jat.1675

Heisinger, J. F., and Green, W. (1975). Mercuric chloride uptake by eggs of the ricefish and resulting teratogenic effects. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 14, 665–673. doi: 10.1007/BF01685240

Herrmann, K. (1993). Effects of the anticonvulsant drug valproic acid and related substances on the early development of the zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio). Toxicol. In Vitro. 7, 41–54. doi: 10.1016/0887-2333(93)90111-H

Houck, A., and Cech, J. J. (2004). Effects of dietary methylmercury on juvenile Sacramento blackfish bioenergetics. Aquat. Toxicol. 69, 107–123. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2004.04.005

Huang, L. X., Liu, W. J., Jiang, Q. L., Zuo, Y. F., Su, Y. Q., Zhao, L. M., et al. (2019). A metabolomic investigation into the temperature dependent virulence of Pseudomonas plecoglossicida from large yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea). J. Fish. Dis. 42, 431–446. doi: 10.1111/jfd.12957

Huang, W., Cao, L., Ye, Z. J., Yin, X. B., and Dou, S. Z. (2010). Antioxidative responses and bioaccumulation in Japanese flounder larvae and juveniles under chronic mercury exposure. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 152, 99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2010.03.005

Ishikawa, N. M., Ranzani-Paiva, M. J. T., and Lombardi, J. V. (2007). Acute toxicity of mercury (HgCl2) to Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Bol. Inst. Pesca. 33, 99–104.

Jewett, S. C., Zhang, X., Naidu, A. S., Kelley, J. J., Dasher, D., and Duffy, L. K. (2003). Comparison of mercury and methyl mercury in northern pike and Artic grayling from western Alaska rivers. Chemosphere 50, 383–392. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(02)00421-6

Jezierska, B., Ługowska, K., and Witeska, M. (2009). The effects of heavy metals on embryonic development of fish (a review). Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 35, 625–640. doi: 10.1007/s10695-008-9284-4

Kirubagaran, R., and Joy, K. P. (1988). Toxic effects of three mercurial compounds on survival, and histology of the kidney of the catfish Clarias batrachus (L.). Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 15, 171–179. doi: 10.1016/0147-6513(88)90069-3

Latif, M. A., Bodaly, R. A., Johnston, T. A., and Fudge, R. J. P. (2001). Effects of environmental and maternally derived methylmercury on the embryonic and larval stages of walleye (Stizostedion vitreum). Environ. Pollut. 111, 139–148. doi: 10.1016/S0269-7491(99)00330-9

Lee, Y. H., Kim, D. H., Kang, H. M., Wang, M., Jeong, C. B., and Lee, J. S. (2017). Adverse effects of methyl mercury (MeHg) on life parameters, antioxidant systems, and MAPK signaling pathways in the rotifer Brachionus koreanus and the copepod Paracyclopina nana. Aquat. Toxicol. 190, 181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.07.006

Mallatt, J., Barron, M. G., and Mc Donough, C. (1986). Acute toxicity of methyl mercury to the larval lamprey, Petromyzon marinus. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 37, 281–288. doi: 10.1007/BF01607762

Mozhdeganloo, Z., Jafari, A. M., Koohi, M. K., and Heidarpour, M. (2015). Methylmercury -induced oxidative stress in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) liver: ameliorating effect of vitamin C. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 165, 103–109. doi: 10.1007/s12011-015-0241-7

OECD (1998). Test No. 212: Fish, Short-term Toxicity Test on Embryo and Sac-Fry Stages, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/9789264070141-en

Orrenius, S., Zhivotovsky, B., and Nicotera, P. (2003). Regulation of cell death: the calcium-apoptosis link. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 552–565. doi: 10.1038/nrm1150

Pack, E. C., Kim, C. H., Lee, S. H., Lim, C. H., Sung, D. G., Kim, M. H., et al. (2014). Effects of environmental temperature change on mercury absorption in aquatic organisms with respect to climate warming. J. Toxicol. Env. Health Part A. 77, 1477–1490. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2014.955892

Ren, Z. H., Cao, L., Huang, W., Liu, J. H., Cui, W. T., and Dou, S. Z. (2019). Toxicity test assay of waterborne methylmercury on the Japanese Flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) at embryonic-larval stages. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 102, 770–777 doi: 10.1007/s00128-019-02619-9

Roales, R. R., and Perlmutter, A. (1974). Toxicity of methylmercury and copper, applied singly and jointly, to the blue gourami, Trichogaster trichopterus. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 12, 633–639. doi: 10.1007/BF01684931

Samson, J. C., and Shenker, J. (2000). The teratogenic effects of methylmercury on early development of the zebrafish, Danio Rerio. Aquat.Toxicol. 48, 343–354. doi: 10.1016/S0166-445X(99)00044-2

Satoh, H. (2000). Occupational and environmental toxicology of mercury and its compounds. Ind. Health. 38, 153–164. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.38.153

Sharp, J. R., and Neff, J. M. (1982). The toxicity of mercuric chloride and methylmercuric chloride to Fundulus heteroclitus embryos in relation to exposure conditions. Environ. Biol. Fish. 7, 277–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00002502

Syversen, T., and Kaur, P. (2012). The toxicology of mercury and its compounds. J Trace Elem Med Biol 26, 215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2012.02.004

Trasande, L., Landrigan, P. J., and Schechter, C. (2005). Public health and economic consequences of methyl mercury toxicity to the developing brain. Environ. Health. Perspect. 113, 590–596. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7743

UNEP (2002). Global Mercury Assessment Report. New York, NY: United Nations Environmental Programme. Available from: http://www.chem.unep.ch/mercury/Report/GMA-report-TOC.htm (accessed August 24, 2010).

Weis, J. S., Weis, P., Heber, M., and Viadya, S. (1981). Methylmercury tolerance of killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus) embryos from a polluted vs non-polluted environment. Marine. Biology. 65, 283–287. doi: 10.1007/BF00397123

Witeska, M., Sarnowski, P., Ługowska, K., and Kowal, E. (2014). The effects of cadmium and copper on embryonic and larval development of ide Leuciscus idus L. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 40, 151–163. doi: 10.1007/s10695-013-9832-4

Wobeser, G. (1975). Acute toxicity of methyl mercury chloride and mercuric chloride for rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri) fry and fingerlings. J. Fish. Res. Board. Can. 32, 2005–2013. doi: 10.1139/f75-236

Wu, F. Z., Huang, W., Liu, Q., Xu, X. Q., Zeng, J. N., Cao, L., et al. (2018). Responses of antioxidant defense and immune gene expression in early life stages of large yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea) under methyl mercury exposure. Front. Physiol. 9:1436. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01436

Xia, C. H., Wu, X. G., Lam, J. C. W., Xie, Z. Q., and Lam, P. K. S. (2013). Methylmercury and trace elements in the marine fish from coasts of East China. Environ. Lett. 48, 1491–1501. doi: 10.1080/10934529.2013.796820

Xu, K. D., and Liu, Z. F. (2007). The current stock of large yellow croaker Pseudosciaena crocea in the East China Sea with respects of its stock decline. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 22, 392–396. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-9957.2007.05.015

Yamagami, K. (1981). Mechanisms of hatching in fish: secretion of hatching enzyme and enzymatic choriolysis. Am. Zool. 21, 459–471. doi: 10.1093/icb/21.2.459

Keywords: development, early life stage (ELS), methylmercury, Pseudosciaena crocea, toxicity

Citation: Yu X, Wu F, Xu X, Chen Q, Huang L, Teklehaimanot Tesfai B, Cao L, Xu X, Dou S and Huang W (2019) Effects of Short Term Methylmercury Exposure on Growth and Development of the Large Yellow Croaker Embryos and Larvae. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:754. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00754

Received: 24 September 2019; Accepted: 20 November 2019;

Published: 06 December 2019.

Edited by:

Xiaoshou Liu, Ocean University of China, ChinaReviewed by:

Jun Bo, Third Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration, ChinaChristyn Bailey, Inmunología y Patología de Peces, Centro de Investigación en Sanidad Animal (CISA, INIA), Spain

Copyright © 2019 Yu, Wu, Xu, Chen, Huang, Teklehaimanot Tesfai, Cao, Xu, Dou and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liang Cao, caoliang@qdio.ac.cn; Wei Huang, willhuang@sio.org.cn

Xiang Yu

Xiang Yu Fangzhu Wu

Fangzhu Wu Xiaoqun Xu1

Xiaoqun Xu1 Wei Huang

Wei Huang