94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Mar. Sci., 11 June 2019

Sec. Marine Conservation and Sustainability

Volume 6 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00304

This article is part of the Research Topic5th International Marine Conservation CongressView all 23 articles

As a crisis sector, marine conservation needs continuous public scrutiny to maintain much-needed transparency, accountability, and to secure public trust. Such opportunities for public scrutiny can be ensured through independent, objective and critical journalism (Johns and Jacquet, 2018). However, mainstream media and other journalistic platforms often rely on communication professionals working at marine conservation groups for information and expertise related to marine conservation issues. It is therefore crucial that communication professionals at conservation groups have a professional code of conduct that encourages dissemination of objective truth about conservation efforts and does not prevent journalists from carrying out their duties to serve the public interest.

In this piece, we elaborate on our opinion that a professional ethical guideline for marine conservation communication is necessary. We also report on discussions from a focus group titled, “Overcoming ethical challenges in marine conservation communication” held at the 5th International Marine Conservation Congress (IMCC5). Sixteen marine conservation professionals (scientists, practitioners, and communicators) shared their perspective about existing relationships and modes of engagement between media, journalists and conservation groups, urgency of factual and accurate narratives in ocean conservation, prerequisites of independent and transparent reporting while promoting conservation efforts, and the inclusion of local and indigenous voices in conservation narratives. Focus group participants discussed solutions-driven directives that could be incorporated into a professional code of conduct for conservation communicators and debated the fundamental premises of such a code.

“Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one” (Liebling, 1964). With the explosion of publishing platforms made possible by the Internet, this quote from Liebling rings truer today than it did in the 1960s. The demise of the journalistic watchdog and the rise of the citizen journalists (Bruns, 2008) have created a dynamic that means it is up to the reader to navigate between professional journalism, irresponsible click-bait, opinion blog posts, and agenda driven articles. Grassroots reporting (blog indexes, personal blogs) and the rise of citizen journalism have created an active audience that not only follows the news, but contributes (Bruns, 2008). The journalistic role of gatekeeping, filtering information before publishing, has diminished, transforming the role instead to gate watcher (Bruns, 2008) or scout in the jungle of information (Brüggemann, 2017), leaving journalists to filter information which is already published. With no dedicated watchdog, open publishing platforms allow everyone with access to the internet to have a voice. This, in turn, is enabling content that is directly or indirectly guided or influenced by those who may carry subjective, agenda-driven intentions, be it an organization, NGO, advertiser, broadcaster, or individual science communicator.

This is blurring the boundaries between environmental journalism and advocacy (Rosenstiel et al., 2016) which we, the authors, believe can have both a positive and negative impact on the way readers understand and interpret marine conservation. In some fields this is allowing more

extensive reporting on events such as climate conferences (Rosenstiel et al., 2016), yet it is also creating the opportunity for self-promotion, which depending on the agenda of the writer, can pose threats to the public's objective understanding of marine conservation and the issues facing the planet.

Recently, an opinion piece published in the New York Times discussed the trend of “just add water” that is seeing the triumphant announcement of large marine protected areas, which are protecting relatively empty waters as opposed to prioritizing coastal habitats that are home to 25% of all marine species (Rocha, 2018). While this opinion is not shared by all scientists (MacPherson, 2018), others (Barnes et al., 2018) stress the need to report outcomes as opposed to area when it comes to announcing new protected areas, arguing that the focus should be on anticipated biodiversity gains rather than the square kilometers protected. The root of this problem may, in fact, lie with the issuer of the original press release (e.g., an NGO) or the opinion piece may have been politically motivated. Crucially, there is an issue of transparency which needs to be improved from both sides: the source (the issuer of the press release) and the entity covering the story.

Another difficulty is simply distinguishing between science journalism—a responsibility to inform and educate the public (Xu, 2013), assess, critique and contextualize science and scientists rather than promote it (Borel, 2015), and science communication, which explains how a natural phenomenon works or describes “the how” of new scientific discoveries. The important difference is that how science communicators portray their topic depends on their intentions, which should be transparent (Borel, 2015). Xu argues that the ability for scientists to publish directly to the general public, without going through the official publishing process, is creating a new “science-media ecosystem.” Though a direct link between scientists and the public can be beneficial, journalist Brooke Borel highlights the importance of journalistic scrutiny in questioning the intentions of scientists or organizations publishing their own scientific outreach (Borel, 2015).

While some argue that we are in an “Unlikely Golden Age” at the height of production in terms of both quantity and quality of science and environmental journalism (Hayden and Check Hayden, 2018), we believe that despite this, there is a lack of capacity when it comes to reporting on marine conservation. An example is a recent article by The Guardian (Summers, 2018) which reports on a new scientific study concerning a controversial whale shark tourism site in the Philippines (which one of the authors and her team studies). The journalist reports only one side of the controversy, omitting all previous research from the same study site, and fails to include an outside quote. The article also reported illegal activity which lacked original sources.

The implications of poorly executed journalism such as this are far reaching. They can miseducate the public on complex topics and undermine conservation efforts. Are journalists at capacity and not able to dedicate their full time to covering marine conservation, similar to that of other environmental journalists (Detjen et al., 2000)? Or are there simply too few experts, with only a small group of journalists producing the vast majority of coverage (Brüggemann and Engesser, 2014)? Either way, how can this knowledge gap be moderated?

Communication professionals in NGOs can mitigate a lack of journalistic capacity in the marine conservation space if they commit to balanced, transparent self-reporting, and to help independent and objective reporting. However, this is not always the case. Mongabay's 2016 Conservation, Divided series highlighted that the biggest NGOs often issue “press releases that could convince a misanthrope to love people [and] make whatever they do sound like a resounding success, even when the reality is much more complex” (Hance, 2016). Biased self-reporting can also be off-putting for donors. A recent analysis commissioned by ISEAL, the global best practice community of standard setters, found that funders are more likely to believe communications that contain negative as well as positive impact (Chilvers, 2017). This suggests there is an opportunity for professional marine conservation communicators to contribute to objective reporting while improving relationships with key partners.

Finally, whether or not coverage of marine conservation efforts is the result of sponsored or embedded arrangements (e.g., a journalist given access to a remote marine location through an NGO sponsorship), conservation communicators must permit journalistic contents to be produced independently with objectivity and independence needed in the persuasion of the truth.

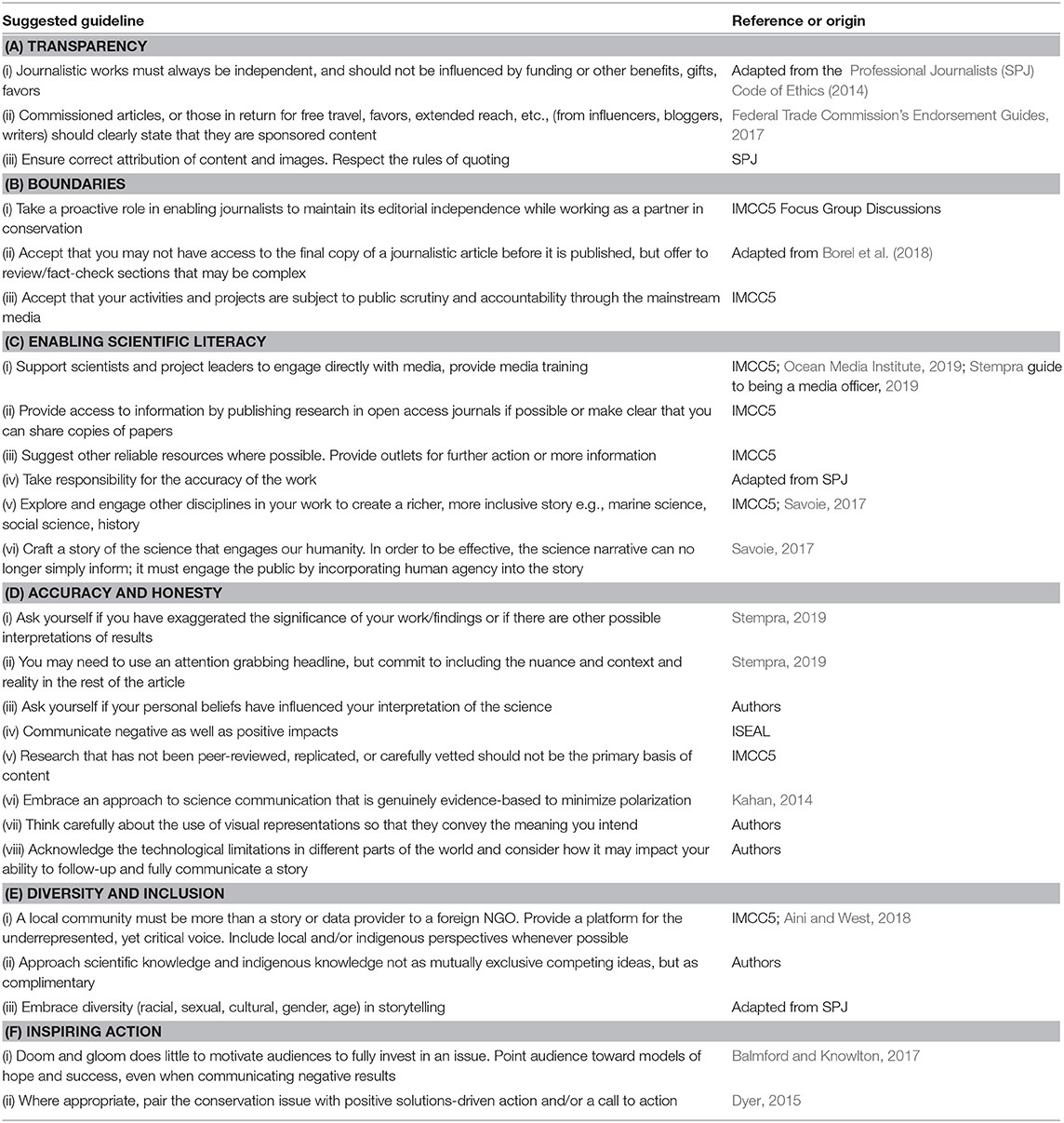

We believe there is a need for a code of professional ethics for marine conservation communicators that promotes trust, accountability, independence, and solutions-based reporting, all the while furthering the value of a compelling story. These guidelines (Table 1) draw together existing resources as well as emerging areas of focus and can be used as a tool by communication practitioners and scientists to create a professional ethics code, but can also be adopted by journalists and other content creators. Acknowledging the limitations of our own knowledge and the small sample size of opinions collated, we present them not as a final or comprehensive list, but as a starting point for much needed future collaborative work in this space.

Table 1. Suggestions to include in a code of professional ethics for marine conservation communicators.

In conclusion, no matter how much conservation groups have sway over social media and public relation platforms, those are not a replacement for independent journalism. While we should continue to strongly advocate for conservation, we should not make it difficult for journalists to inform the debate with facts and a commitment to making all voices heard. We hope this article will spark a conversation about the necessity of a code of professional ethics for marine conservation communicators.

MU conceived the idea and scope of problem. GS, LE, MU, and SS devised main conceptual ideas and designed the article. SS and LE took notes at the focus group discussion. All authors provided critical feedback and contributed to develop the final manuscript.

No funding was received for this work. Open access fees sponsored by Marine Stewardship Council (MSC).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the organizing committee of the 5th International Marine Conservation Congress and acknowledge the important feedback and contributions of all participants in the IMCC5 focus group Overcoming ethical challenges in marine conservation communication; Jorge Torre-Cosío (Director General, COBI), Kate Green (Australian Government), Pia Harkness (Ph.D. Candidate), John Zachary Koehn (Ph.D. Candidate), Luiz A. Rocha (Scientist), Georgina Short (Researcher), Sythong Run (Marine Researcher), Anjani Tiwari (Researcher), Benjamin L. Jones (Director, Project Seagrass), John Aini (Marine Conservationist), Mahatub Khan Badhon (Marine Conservationist), Nadiah Rosli (Freelance Journalist), and Fahmida Khalique Nitu (Conservationist).

1. Aini J., and West P. (2018). “Communities matter: decolonizing conservation management,” in Plenary Lecture, International Marine Conservation Congress (Kuching).

2. Balmford A., and Knowlton N. (2017). Why earth optimism? Science 356:225. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4082

3. Barnes M. D., Glew L., Wyborn C., and Craigie I. D. (2018). Prevent perverse outcomes from global protected area policy. Nat. Ecol. Evolut. 2, 759–762. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0501-y

4. Borel B. (2015). The Problem With Science Journalism: We've Forgotten That Reality Matters Most. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2015/dec/30/problem-with-science-journalism-2015-reality-kevin-folta (accessed February 21, 2019).

5. Borel B., Sheikh K., Husain F., Junger A., Biba E., Blum D., et al. (2018). The State of Fact-Checking in Journalism. Knight Science Journalism, MIT. Available online at: https://www.moore.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/fact-checking-in-science-journalism_mit-ksj.pdf?sfvrsn=a6346e0c_2 (accessed March 22, 2019).

6. Brüggemann M. (2017). Shifting roles of science journalists covering climate change. ORE Climate Science. Available online at: http://climatescience.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228620-e-354 (accessed May 29, 2019).

7. Brüggemann M., and Engesser S. (2014). Between consensus and denial: climate journalists as interpretive community. Sci. Commun. 36, 399–427. doi: 10.1177/1075547014533662

8. Bruns A. (2008). “The active audience: transforming journalism from gatekeeping to gatewatching,” in Making Online News: The Ethnography of New Media Production, eds C. Paterson and D. Domingo (New York, NY: Peter Lang, 171–184.

9. Chilvers A. (2017). Guidelines for Effective Communication of the Impact of Sustainability Initiatives. London: Kayak Gold Consulting on behalf of ISEAL. Consultant report available upon request.

10. Detjen J., Fico F., Li X., and Kim Y. (2000). Changing work environment of environmental reporters. Newspaper Res. J. 21, 2–11. doi: 10.1177/073953290002100101

11. Dyer J. (2015). Is Solutions Journalism the Solution? Nieman Reports, Harvard College. Available online at: https://niemanreports.org/articles/is-solutions-journalism-the-solution/ (accessed May 29, 2019).

12. Federal Trade Commission (2017). Federal Trade Commission's (FTC) Endorsement Guides. Available online at: https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/press-releases/ftc-publishes-final-guides-governing-endorsements-testimonials/091005revisedendorsementguides.pdf (accessed May 29, 2019).

13. Hance J. (2016). Epilogue: Conservation Still Divided, Looking for a Way Forward. Mongabay. Available online at: https://news.mongabay.com/2016/05/epilogue-conservation-still-divided-looking-way-forward/ (accessed March 22, 2019).

14. Hayden T., and Check Hayden E. (2018). Science Journalism's unlikely golden age. Front. Commun. 2:24. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2017.00024

15. Johns L. N., and Jacquet J. (2018). Doom and gloom versus optimism: an assessment of ocean-related U.S. science journalism (2001-2015). Glob. Environ. Change 50, 142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.04.002

16. Kahan D. (2014). “Making climate science communication evidence based—all the way down,” in Culture, Politics and Climate Change: How Information Shapes Our Common Future, in D. A. Crow and M. T., Boykoff (New York, NY: Routledge, 203–220.

18. MacPherson R. (2018). Embracing Yes/Also: Marine Protected Areas Are Not an Either/or Proposition, Deep Sea News. Available online at: https://www.deepseanews.com/2018/03/embracing-yes-also-marine-protected-areas-are-not-an-either-or-proposition/ (accessed December 18, 2018).

19. Ocean Media Institute (2019). Available online at: http://www.oceanmediainstitute.org (accessed May 29, 2019).

20. Professional Journalists (SPJ) Code of Ethics (2014). Available at: https://www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp (accessed March 22, 2019).

21. Rocha L. A. (2018). Bigger is Not Better for Ocean Conservation, The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/20/opinion/environment-ocean-conservation.html (accessed December 18, 2018).

22. Rosenstiel T., Buzenberg W., Connelly M., and Loker K. (2016). Charting New Ground: The Ethical Terrain of Nonprofit Journalism. American Press Institute. Available online at: https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/publications/reports/nonprofit-news/ (accessed May 29, 2019).

23. Savoie G. M. (2017). Our storied sea: crafting a collective narrative of the ocean through accompaniment (Ph.D. Dissertation). Montana State University. Available online at: https://scholarworks.montana.edu/xmlui/handle/1/14190 (accessed May 29, 2019).

24. Stempra (2019). Guide to Being a Media Officer. Available online at: https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/241584?fbclid=IwAR3beySOJey8-T3CAPJYsCE7WUXjxnq0desqYhAomsCVmtERHLCL_9JTUJI (accessed March 22, 2019).

25. Summers H. (2018). How Whale Sharks Saved a Philippine Fishing Town and Its Sea Life, The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/dec/10/how-whale-sharks-saved-a-filippino-fishing-town-and-its-sea-life (accessed December 18, 2018).

26. Xu T. (2013). What is the Role of Science Journalism in the 21st Century? Medium. Available online at: https://medium.com/i-m-h-o/what-is-the-roleof-science-journalism-in-the-21st-century-2a97214fc67a (accessed March 6, 2019).

Keywords: communication, marine, conservation, professional ethics, media, science communication

Citation: Erickson LE, Snow S, Uddin MK and Savoie GM (2019) The Need for a Code of Professional Ethics for Marine Conservation Communicators. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:304. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00304

Received: 23 March 2019; Accepted: 23 May 2019;

Published: 11 June 2019.

Edited by:

Jason Paul Landrum, Lenfest Ocean Program, Pew Charitable Trusts, United StatesReviewed by:

Janie Harden Fritz, Duquesne University, United StatesCopyright © 2019 Erickson, Snow, Uddin and Savoie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lucy E. Erickson, bC5lcmlja3Nvbi5lQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.