94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci., 12 October 2017

Sec. Marine Fisheries, Aquaculture and Living Resources

Volume 4 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00316

This article is part of the Research TopicChallenges and Opportunities for The EU Common Fisheries Policy application in The Mediterranean and Black SeaView all 18 articles

Saša Raicevich1,2*

Saša Raicevich1,2* Pietro Battaglia3

Pietro Battaglia3 Tomaso Fortibuoni1,4

Tomaso Fortibuoni1,4 Teresa Romeo3

Teresa Romeo3 Otello Giovanardi1,2

Otello Giovanardi1,2 Franco Andaloro5

Franco Andaloro5The Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) aims to achieve “Good Environmental Status” (GES) in EU marine waters by 2020. This initiative started its first phase of implementation in 2012, when each member state defined the GES and environmental targets in relation to 11 descriptors and related indicators for 2020. In 2013, the EU Commission launched the reformed Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), which aims to achieve biomass levels capable of producing maximum sustainable yield (MSY) for all commercial stocks exploited in EU waters by 2020, as well as contribute to the achievement of GES. These two pieces of legislation are aligned since according to Descriptor 3 (commercial fish and shellfish), the MSFD requires reaching a healthy stock status with fishing mortality (F) and spawning stock biomass (SSB) compatible with the respective MSY reference limits for all commercial species by 2020. We investigated whether the two policies are effectively aligned in the Mediterranean Sea, an ecosystem where the vast majority of stocks show unsustainable exploitation. For this purpose, we assessed and compared the number and typology of stocks considered by the member states when assessing GES in relation to data on stocks potentially available according to the EU Data Collection Framework (DCF) and the proportion of landings they represented. The number of stocks considered by the member states per assessment area was uneven, ranging between 7 and 43, while the share of landings corresponding to the selected stocks ranged from 23 to 95%. A lack of coherence between GES definitions among the member states was also revealed, and environmental targets were less ambitious than MSFD and CFP requirements. This could possibly reduce the likelihood of achieving fishery sustainability in the Mediterranean by 2020. These conditions limited the envisaged synergies between the two policies and are discussed in consideration of the recent Commission Decision on criteria and methodological standards for GES.

In 2008, the European Commission approved the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (Directive 2008/56/EC; MSFD; EU-COM, 2008), which was the new legislation put forward under the coordination of the EU Directorate-General for Environment aimed at achieving “Good Environmental Status” (GES) in EU waters by 2020. This concept represents “the environmental status of marine waters where these provide ecologically diverse and dynamic oceans and seas which are clean, healthy, and productive” (Article 3; EU-COM, 2008). According to the MSFD implementation process under Article 5, member states were requested to carry out “(i) an initial assessment (IA) (…) of the current environmental status of the waters concerned and the environmental impact of human activities thereon (…); (ii) a determination (…) of GES for the waters concerned (…); (iii) establishment of a series of environmental targets (ETs) and associated indicators” by July 15, 2012 (EU-COM, 2008).

This assessment should have been done in the context of “waters, the seabed, and subsoil on the seaward side of the baseline from which the extent of territorial waters is measured extending to the outmost reach of the area where a Member State has and/or exercises jurisdictional rights, in accordance with the Unclos (…)” (Article 3.1a; EU-COM, 2008). Moreover, it should have taken into account regional and subregional subdivisions of the MSFD as identified under Article 4 of the directive (EU-COM, 2008). In doing so, member states were asked to coordinate with the other EU states and other countries with national waters within the same region or subregion using “existing regional institutional cooperation structures, including those under Regional Sea Conventions, covering that marine region or subregion” (Article 6.1; EU-COM, 2008).

After consulting all interested parties, the Commission issued the decision on criteria and methodological standards for the GES of marine waters for implementation of the MSFD (Commission Decision 2010/477; EU-COM, 2010). This defined the qualitative description of GES in relation to 11 descriptors, along with a set of related criteria and indicators to be applied for quantitative assessment. In particular, Descriptor 3 concerns commercially exploited species. Its GES is qualitatively described as the condition where “populations of all commercially exploited fish and shellfish are within safe biological limits, exhibiting a population age and size distribution that is indicative of a healthy stock” (Annex, Part B, EU-COM, 2010). The commission decision stated that stocks to be considered for the purpose of such an assessment should have included “all the stocks covered by Regulation (EC) No. 199/2008 (within the geographical scope of Directive 2008/56/EC) and similar obligations under the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). For these and for other stocks, its application depends on the data available (taking the data collection provisions of Regulation (EC) No. 199/2008 into account), which will determine the most appropriate indicators to be used” (Annex, Part B, EU-COM, 2010).

Regulation (EC) No. 199/2008 (EU, 2008) refers to the Data Collection Framework (DCF) established in 2000 within the CFP for the collection and management of fishery data. Under this framework, the member states collect, manage, and provide a wide range of fisheries data for the main stocks, which are selected by DCF according to their relevance in terms of both landings and value. Such data include both the biological data (e.g., landings and catches by métier, fishery independent data) and socio-economic data (e.g., employment, revenues, etc.) needed for scientific advice. Accordingly, the definition of stocks to be considered within the MSFD established the need for including all stocks for which DCF applies, thus determining a clear link between the MSFD and the CFP.

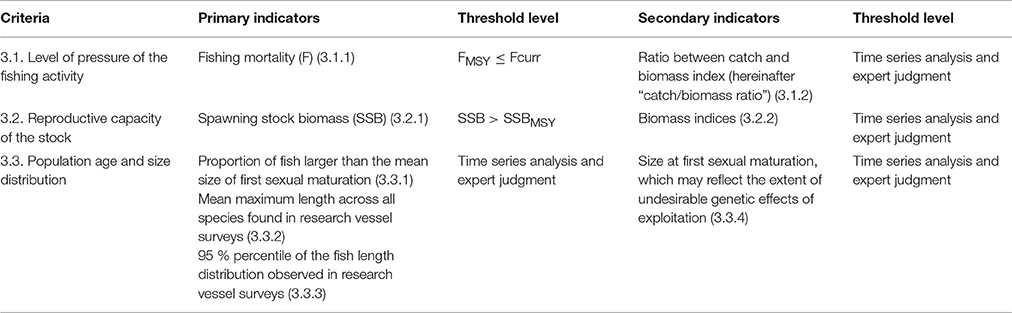

The three criteria to be considered for the assessment of GES by member states included fishing pressure, reproductive capacity, population age and size distribution, whose assessment is based on a suite of primary and secondary indicators (Table 1). Moreover, the first two criteria adopt, in the case of primary indicators, MSY-related reference points. The reformed CFP was delivered in 2013, 5 years after establishing the MSFD and 3 years after the definition of MSFD criteria and methodological standards by the Commission. The new basic regulation of the CFP is aligned to the overall objectives of the MSFD in relation to Descriptor 3, as the CFP is aimed at implementing measures to gradually reach biomass levels capable of producing the maximum sustainable yield (MSY; spawning stock biomass - SSB above BMSY) by 2015 where possible, and no later than 2020. Moreover, the two policies in relation to commercial fish and shellfish are interrelated and it is among the purposes of CFP to contribute to achieving GES (Article 2j; EU, 2013). In addition, the monitoring activities carried out within the DCF are some of the main providers of data to support the implementation of the MSFD, and not only in relation to commercially exploited species (Zampoukas et al., 2014).

Table 1. Criteria, primary and secondary indicators, and associated threshold levels, for the assessment of GES in relation to Descriptor 3, according to MSFD Criteria and Methodological Standards (EU-COM, 2010).

The Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on the first phase of implementation of the MSFD (COM 2014/97 final; EU-COM, 2014) showed a limited degree of coordination among member states in relation to several descriptors. This condition was also confirmed in a study by Crise et al. (2015) on Southern European seas, which also pointed out the issue of the lack of data for the implementation of GES for some descriptors, as well as an imbalance in MSFD implementation between coastal and off-shore areas. Regarding Descriptor 3, the report from the Commission (EU-COM, 2014; EU-COM Annex, 2014) identified the lowest degree of coherence at the regional level in relation to IA, GES, and ET definition across the Mediterranean subregions, while medium coherence was achieved in the Northern Seas (NE Atlantic), which was confirmed by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES, 2014a).

This outcome is quite relevant since the Mediterranean Sea, a large marine ecosystem characterized by high biodiversity (Coll et al., 2010), is subjected to an intensive fishing pressure, with about 90% of assessed stocks showing clear signs of overexploitation (Colloca et al., 2013). Despite the alarming evidence of excessive fishing mortality (Fcurr >> FMSY) exerted on exploited populations (Vasilakopoulos et al., 2014; Tsikliras et al., 2015), fishing pressure has not been reduced in the last decade for most species (Cardinale and Scarcella, 2017). In the whole Mediterranean and Black Sea Basin, fishery management is carried out in the framework of the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM). The GFCM is a Regional Fisheries Management Organization (RFMO) that plays a role in coordinating efforts by governments to effectively manage fisheries at the regional level following the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (FAO, 1995).

However, for EU member states with national waters in the Mediterranean and Black Sea Basins, the prescriptions of the CFP also apply. At present, the main EU fishery legislations for this area include the Mediterranean Regulation [Council Regulation (EC) No. 1967/2006; EU, 2006] and the reformed CFP [Regulation (EU) No. 1380/2013, EU, 2013]. Landings from EU member states account for about 87% of the total Mediterranean landings (average for the 2011–2014 period based on FAO Fishstat data). The CFP is associated with a financial instrument [Regulation (EU) No. 508/2014; EU, 2014] that allows co-financing data collection [Council Regulation (EC) No. 199/2008, EU, 2008; Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2016/1251, EU-COM, 2016]. Moreover, it supports member states for the implementation of CFP-related structural policies (e.g., reduction of fishing capacity, support to the development of processing and trading, etc.). Owing to such financial support and to the political role of the EU in managing the fishery sector of member states, the CFP is substantially more demanding than current GFCM prescriptions in terms of member-state obligations.

Given the presence of a common and coherent base of available data (i.e., DCF), the MSFD prescriptions for coordination among member states and within the Regional Sea Convention, and the recorded evidence of limited coherence within MSFD implementation in the Mediterranean Sea (EU-COM, 2014; EU-COM Annex, 2014; Crise et al., 2015), we wanted to assess and compare in detail how member states implemented the MSFD in relation to Descriptor 3, as well as identify the most critical sources of discrepancies. Our general hypothesis based on MSFD requirements is that member states should have adopted similar approaches in the selection of assessment areas, stocks to be considered, GES, and target definitions, and that within the same subregion, the approaches should have been consistent.

In this context, we analyzed the coherence of MSFD implementation at the national level across Mediterranean member states and with both MSFD and CFP objectives. The potential synergies between these two pieces of legislation were also considered in light of increasing the degree of their coherence to further support the efforts to reach fishery sustainability and GES in the area.

Accordingly, our analysis focuses on the following objectives:

1) Assessing the coherence of the selection of stocks and the extent to which the member states used data collected under the EU DCF (EU, 2008) for the purposes of IA and GES assessment within the MSFD.

2) Estimating the percentage of landings subjected to quantitative assessment of GES and comparing it to the past and future data availability given EU and GFCM obligations on data collection.

3) Providing an in-depth analysis of the approach adopted for MSFD reporting and implementation at the Mediterranean level, considering the definition of the spatial units adopted (i.e., assessment areas), GES and ET.

4) Assessing the current coherence in the implementation of the MSFD in relation to CFP objectives for commercial fish and shellfish stocks while considering the potential future impact of the recent process established under the relevant Regional Sea Convention (Barcelona Convention) and GFCM to address MSFD obligations.

These elements are also discussed in light of the recent Commission Decision (EU) 2017/848 (EU-COM, 2017) released on May 17, 2017, which updates the former decision on criteria and methodological standards for GES (EU-COM, 2010). In this context, we reflect on whether this new technical specification will ensure higher coherence in the MSFD implementation in the Mediterranean Sea for GES assessment in regard to Descriptor 3.

Official reports and documentation regarding the implementation of MSFD in EU Mediterranean member states (Spain, France, Italy, Malta, Slovenia, Croatia, Greece, Cyprus, with the exclusion of Gibraltar) were retrieved between January and February 2017 from the Central Data Repository of the European environment Information and Observation Network (Eionet) (http://cdr.eionet.europa.eu/). In the “Central Data Repository” section within the folders of “Marine Strategy Framework Directive: Articles 8, 9, and 10 & geographic areas and regional cooperation reporting,” a series of documents and files were inspected to gather the following information:

– Spatial units of application (i.e., assessment areas, as defined in relation to Descriptor 3).

– A list of stocks considered in the IA for each assessment area (mainly obtained from “national text-based paper reports”).

– GES definitions according to each member state (Supplementary Table 1).

– ET definitions according to each member state (Supplementary Table 2).

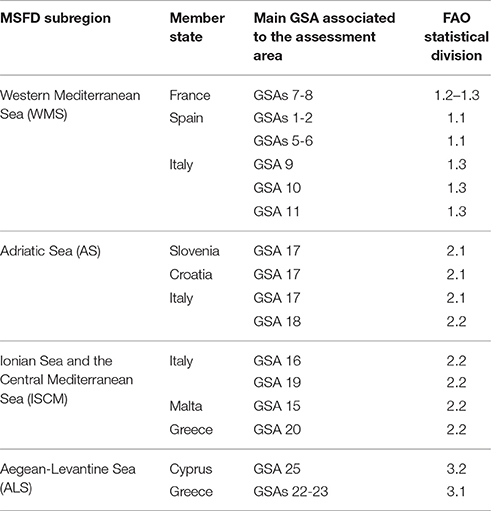

Official EU landings statistics encompassing all commercial species obtained by each member state fleet were not publicly available at disaggregated spatial levels, such as MSFD assessment areas or FAO geographical sub-areas. Accordingly, data based on the FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department and stored in the GFCM (Mediterranean and Black Sea) capture production database were retrieved from the European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet; Human Activities: Fish catches by FAO statistical area; http://www.emodnet-humanactivities.eu/search-results.php?dataname=Fish+Catches+by+FAO+Fishery+Statistical+Areas). The analysis was conducted using landing data from the FAO Fishery Statistics by species for the year 2011 (the closest year available in relation to when MSFD reporting on IA and GES/ET were carried out by MS). These data were assigned unambiguously to the MSFD assessment areas of member states based on the overlap between the country of origin and statistical area (Table 2). Only two exceptions were applied: in the case of Spain, which defined two different assessment areas joining 4 different geographical sub-areas (GSAs: 1, 2, 5, 6), all data refer to the same FAO statistical unit (i.e., Balearic, 37.1.1). Given the inconsistency between FAO statistical units and MSFD subregional domains for Italy, the official national DCF 2011 landing data toglierei la virgola by GSAs were used.

Table 2. Assessment areas identified by each Mediterranean EU member states per single MSFD subregion and overlap with FAO Statistical Areas.

The geographical boundaries of assessment areas as identified by member states were plotted based on coordinates provided by national reports to relate them to the GFCM GSAs and to highlight potential spatial overlap. This condition would imply that member states decided to consider for their assessment of the same area (or at least a portion), thus potentially leading to contrasting interests and methods. Analyses were carried out using QGIS 2.18.4.

We tested the hypothesis that member states would have selected the same species for the MSFD implementation for assessment areas which were close to each other and, in general terms, at subregional and regional levels owing to MSFD prescriptions, the common source of data (i.e., DCF), and the possible similarities in main target species and landings composition. For this purpose, two cluster analyses were performed (Bray–Curtis similarity/group average) on data in relation to each assessment area selected by member states. One considers the selected stocks and is based on presence/absence data, while the second is based on landings per species per assessment area (fourth-root transformation) by member states. The analysis was carried out using Primer 6.1.

We also assessed whether consistency was achieved among member states in terms of the proportion of landings represented by the stocks selected (i.e., the IA and reported GES corresponded to a similar percentage of landings). Accordingly, the percentage of landings of the stocks selected by member states for the purpose of the IA over total landings was computed for national assessment areas at the national level and the subregional level. Species under international management (i.e., under the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas - ICCAT management) were excluded from total landings. The same computation was done for species evaluated through stock assessments carried out in the period of 2010–2011 and approved by the Scientific, Technical, and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF; Cardinale and Osio, 2012). The latter analysis was carried out to highlight the percentage of landings in relation to stocks that provide analytical information to evaluate their status according to MSY-related reference points.

We compared the actual use of data made by member states within the MSFD implementation to the potential past, current, and future availability of data in relation to data collection obligations. To this end, we estimated the percentage of landings corresponding to stocks for which data collection is required under the following considerations:

– Stocks for which the DCF (EU, 2000, 2008; EU-COM, 2016) obligations apply.

– Species assigned a minimum landing size (MLS; now Minimum Conservation Size) according to Reg. 1967/2006 (EU, 2006) and thus subject to the reformed CFP in relation to the establishment of management plans and landing obligations.

– Stocks for which data collection is foreseen in the future according to the recent update of the Data Collection Reference Framework by the GFCM (2016).

In the latter case, we considered three groups of species: A1: stocks that drive the fishery and for which assessment will need to be carried out regularly; A2: stocks which are important in terms of landing or economic value at the regional and subregional levels, and for which assessment will not be regularly carried out; A3: species within international/national management plans and recovery or conservation action plans; non-indigenous species with the greatest potential impact (GFCM, 2016).

GES and ET definitions provided by each member state were analyzed in order to assess whether they were aligned to the MSFD prescriptions and objectives. For this purpose (based on official member state documentation), we assessed the following items:

1) Comprehensiveness of the application of criteria for IA and GES assessment (i.e., whether or not member states applied all criteria).

2) Exhaustiveness of the definition of commercial species to be considered for GES assessment (i.e., whether or not member states clearly defined the list of stocks to be considered for GES assessment).

3) Agreement between the national GES definition, in relation to the use of reference points for indicators 3.1.1 and 3.2.1 and MSFD technical guidelines/CFP objectives (i.e., whether member states defined MSY-related reference levels for GES assessment as targets or limits).

4) Agreement between ET and MSFD/CFP objectives (i.e., whether ETs were clearly defined ensuring to reach MSFD/CFP objectives).

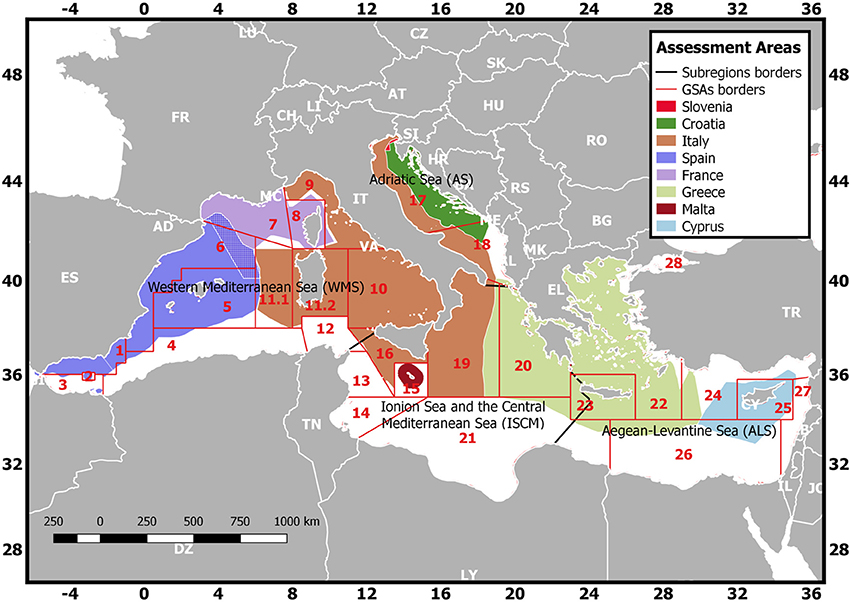

The MSFD divides the Mediterranean region into four different subregions: the Western Mediterranean Sea (WMS); the Adriatic Sea (AS); the Ionian Sea and the Central Mediterranean Sea (ISCM); and the Aegean-Levantine Sea (ALS). Member states had to consider such geographical sub-divisions when defining the extent of assessment areas. Most assessment areas were included in each geographical subregion except for the Strait of Sicily, for which the extension partially overlapped between the WMS and ISCM subregions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The spatial boundaries of assessment areas identified by member states for the assessment of Descriptor 3 within the MSFD. Boundaries of FAO geographical sub-areas are also represented in the background. The area identified by the white crosses represents the overlap between France and Spanish assessment areas.

Mediterranean member states defined 16 assessment areas in total, for which the spatial extension approximately overlapped with GFCM GSAs (Figure 1; Table 2). However, while the match between assessment areas and GSAs was almost full for Italy, Malta, Croatia, and Cyprus (i.e., each GSA had a corresponding assessment area), Spain, France, and Greece defined some assessment areas that merge two GSAs. In detail, Spain considered two assessment areas, the “Strait and Alboran” and the “Levantine Balearic area,” which almost overlapped with GSAs 1–2 and 5–6, respectively. France defined a single assessment area by merging waters of the Gulf of Lion (GSA 7) and the area around Corsica (GSA 8). It is worth mentioning that a clear overlap emerges between Spain's and France's assessment areas (Figure 1). In the Adriatic Sea, Italy, and Croatia restricted their assessment from national waters toward the midline. Within the ALS, Greece considered a single assessment area by merging waters of GSAs 22–23. The Malta assessment area was restricted to national waters and thus a sub-portion of GSA 15. In the case of Cyprus, assessment areas extended beyond the limits of GSA 25, overlapping with two other GSAs.

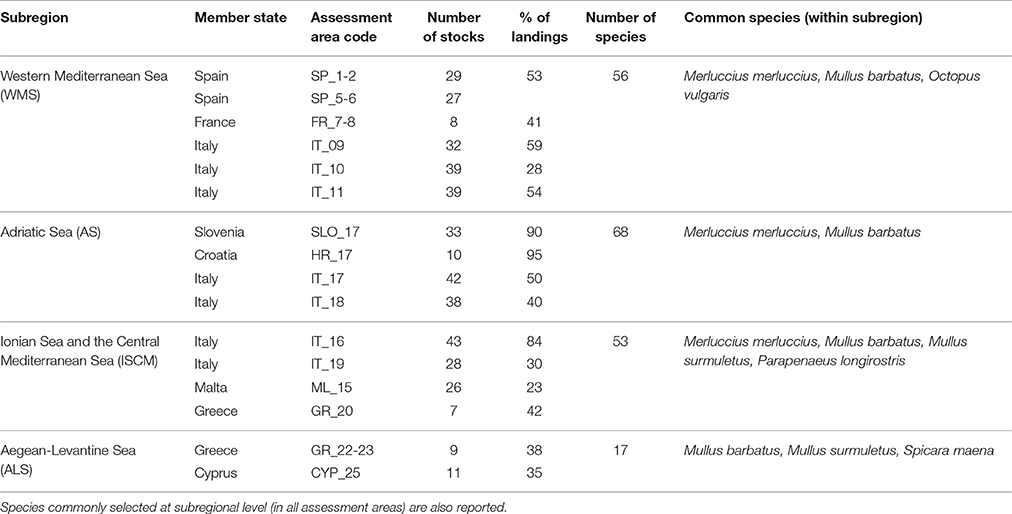

A total of 419 fish and shellfish stocks corresponding to 89 species were considered by EU Mediterranean member states for the purposes of the IA. However, limited consistency emerged in terms of the typology and number of selected stocks among assessment areas within subregions and among subregions. In particular, the number of considered stocks was uneven. Malta, Spain, Slovenia, and Italy considered between 28 to 43 stocks per assessment area, while Greece, France, Croatia, and Cyprus restricted their assessment to a pool of 7–11 selected stocks (Table 3).

Table 3. Number of stocks, species, and the corresponding percentage of landings considered within Initial Assessment in all Mediterranean assessment areas.

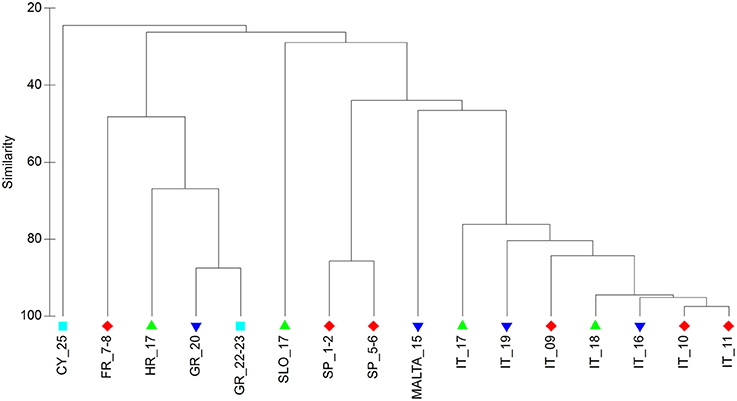

This pattern is also revealed by the cluster analysis based on selected stocks by assessment areas, which shows the presence of two main clusters at a similarity level cutoff of 25% (Figure 2) with one outlier (Cyprus). The two clusters relate to assessment areas of high vs. low numbers of considered stocks (Table 3). Assessment areas displaced in 4 and 3 subregions were grouped within the two clusters, showing a lack of similarities in stock selection within subregions. High similarities were observed among stocks selected at the national level within different assessment areas and subregions, as in the case of Italy (single cluster at a similarity of about 75%), Greece, and Spain (similarity above 80% each).

Figure 2. Cluster analysis (group average, based on Bray–Curtis similarity matrix) of stocks selected per assessment areas (presence/absence data) within the MSFD Initial Assessment in the Mediterranean Region.  : Western Mediterranean Sea;

: Western Mediterranean Sea;  : Adriatic Sea;

: Adriatic Sea;  : Ionian Sea and Central Mediterranean;

: Ionian Sea and Central Mediterranean;  : Aegean-Levantine Sea. Assessment areas codes are reported in Table 3.

: Aegean-Levantine Sea. Assessment areas codes are reported in Table 3.

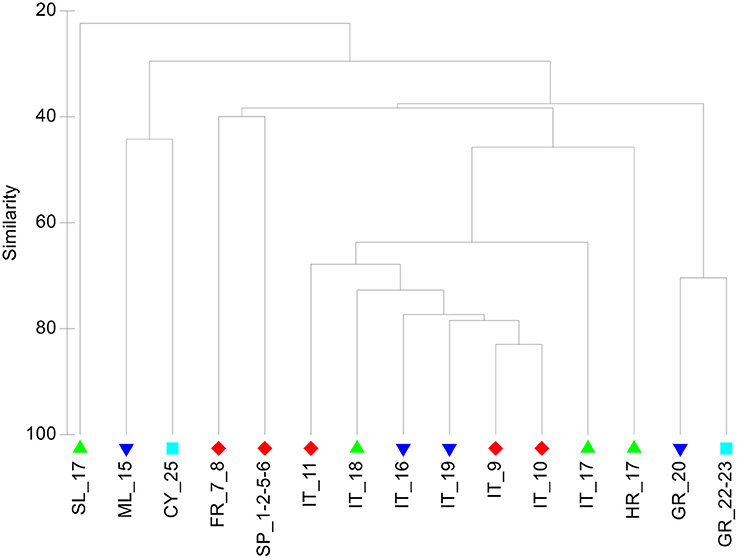

Further information can be derived by comparing the outcomes of this multivariate analysis to the cluster based on landings per species per assessment area (Figure 3). Indeed, at the same similarity cutoff of 25%, only one major cluster is identified grouping all assessment areas apart from that defined by Slovenia. Within the main cluster, two main clusters emerge: one comprising islands (Malta and Cyprus) and another comprising all the other member states. Within the latter, Greece's assessment areas differ, while a major cluster groups Spain's and France's landings and another groups Italy's and Croatia's landings by assessment areas. This result shows similarity among landings of geographically closer assessment areas, which is higher than that observed in terms of selected stocks. Moreover, it shows consistency between landing composition across assessment areas belonging to the same member states. However, in relation to Italian landings, we point out that the high similarity shown among its GSAs could be partially due to the different data sources used for this country compared to the others (i.e., DCF data vs. FAO statistics). The combined analysis of the clusters thus shows that stock selection per assessment area for the IA was not fully consistent with respect to the variation in corresponding landing composition.

Figure 3. Cluster analysis (group average, based on Bray–Curtis similarity matrix) of landings composition per species and assessment areas (fourth root transformation) within the MSFD Initial Assessment in the Mediterranean Region.  : Western Mediterranean Sea;

: Western Mediterranean Sea;  : Adriatic Sea;

: Adriatic Sea;  : Ionian Sea and Central Mediterranean;

: Ionian Sea and Central Mediterranean;  : Aegean-Levantine Sea. Assessment areas codes are reported in Table 3.

: Aegean-Levantine Sea. Assessment areas codes are reported in Table 3.

Further differences are revealed when considering the detailed list of stocks and species selected for the IA at the subregional level. In general terms, the AS subregion was the area where the largest number of species was considered (68), followed by WMS (56) and ISCM (53). Importantly, these values were higher than those of the ALS, where only a total number of 17 species was considered (Table 3).

Mullus barbatus was the only species for which stocks were considered in all the Mediterranean assessment areas. At the subregional scale, Merluccius merluccius represented a common stock in all assessment areas within all subregions apart from the ALS, while Mullus surmuletus was commonly considered in all assessment areas in both ISCM and ALS. Parapenaeus longirostris was considered in all assessment areas of ISCM, while Octopus vulgaris and Spicara smaris were commonly assessed within WMS and ALS, respectively.

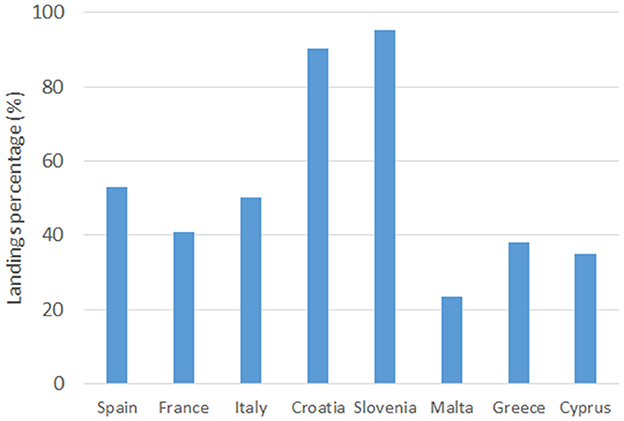

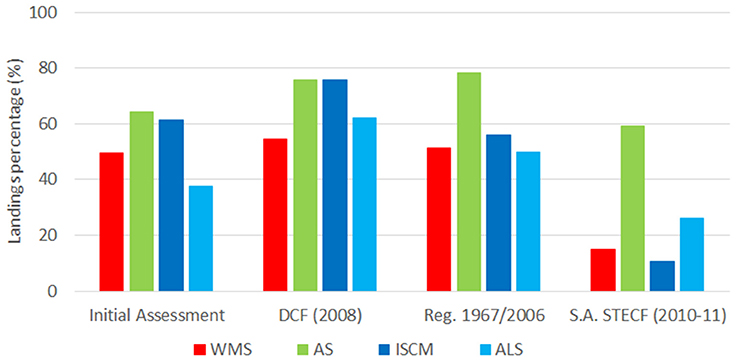

The proportion of landings corresponding to the stock selected by member states within the IA largely varied among assessment areas (Table 3). Overall, member states selected stocks representing different shares of national landings, with the highest values recorded for Slovenia and Croatia (above 90%), intermediate levels for Spain, France, and Italy (between 40 and 60%), and low levels for Malta, Greece, and Cyprus (between 20 and 40%; Figure 4). The comparison between landing percentages considered within IA and those related to data collection and policy obligations already established before shows that member states possibly did not use all potentially available scientific data. Indeed, landings associated with stocks monitored under the DCF (EU, 2008) were higher than those considered for the IA (Figure 5). Even the landings associated with species for which MLS was established according to EU (2006) were higher than those assessed within the IA at the subregional level, apart from the case of WMS. It is also worth noting that when IA was carried out, only a minor share of landings was associated with consolidated stock assessments (i.e., those approved by STECF in 2010–2011; Cardinale and Osio, 2012), thus implying that the application of primary indicators associated with MSFD criteria 3.1 and 3.2 was restricted to a small number of stocks.

Figure 4. Percentage of landings corresponding to the stocks selected by the EU member states within their Initial Assessment.

Figure 5. Percentage of landings corresponding to the stocks considered by EU member states within their Initial Assessment and in relation to data collection and policy obligations. Estimates are given at MSFD subregional level. WMS, Western Mediterranean Sea; AS, Adriatic Sea; ISCM, Ionian Sea and Central Mediterranean; ALS, Aegean-Levantine Sea. DCF (2008): Percentage of landings corresponding to stocks' list object of the DCF (EU, 2008). Reg. 1967/2006: Percentage of landings corresponding to species subjected to Minimum Landings Size according to the Mediterranean Regulation (Appendix 3, EU, 2006). S.A. STECF: Percentage of landings corresponding to stocks which were assessed on 2010–2011 by STECF (Cardinale and Osio, 2012).

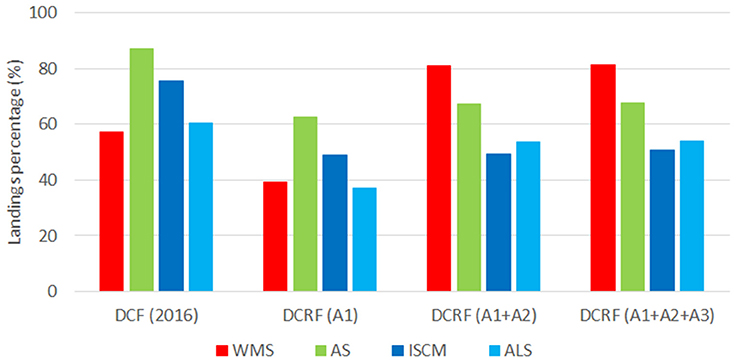

The DCF has recently been revised (EU-COM, 2016), and according to the new set of stocks that will need detailed data collection, a slight increase in the coverage of landings per subregion will be achieved (Figure 6). Recently, the Data Collection Regional Framework by GFCM (FAO, 2016) has been further amended with a request to collect data on a larger share of stocks across the Mediterranean. This is expected to increase the percentage of landings of stocks associated with the formal stock assessment from about 40–60%, depending on the subregion (Figure 6). However, the assessment will be regularly carried out for only a relatively small set of stocks (A1 species), including five species in all Mediterranean subregions (i.e., Engraulis encrasicolus, Sardina pilchardus, M. barbatus, M. merluccius, P. longirostris) and two species assessed in 3 out of 4 subregions (i.e., M. surmuletus and Nephrops norvegicus). Moreover, for other species (A2 species), assessment will not be regular. Based on the availability of both A1 and A2 data, between 50% (ISCM) and 81% (WMS) of landings could be associated with data to assess GES. Considering vulnerable species within international/national management plans, recovery, and conservation action plans (A3 species) will not substantially improve this figure.

Figure 6. Percentage of landings whose data collection is required under recently reviewed international obligations. Estimates are given at MSFD subregional level. WMS, Western Mediterranean Sea; AS, Adriatic Sea; ISCM, Ionian Sea and Central Mediterranean; ALS, Aegean-Levantine Sea. DCF (2016): percentage of landings corresponding to stocks' list object of the recent revision of DCF (EU-COM, 2016). DCRF: Percentage of landings corresponding to stocks' list object of the recent revision of the GFCM Data Collection Regional Framework (FAO, 2016). A1: Stocks that drive the fishery and for which assessment is regularly carried out; A2: Stocks which are important in terms of landing and/or economic values at regional and subregional level, and for which assessment is not regularly carried out; A3: Species within international/national management plans and recovery and/or conservation action plans; non-indigenous species with the greatest potential impact.

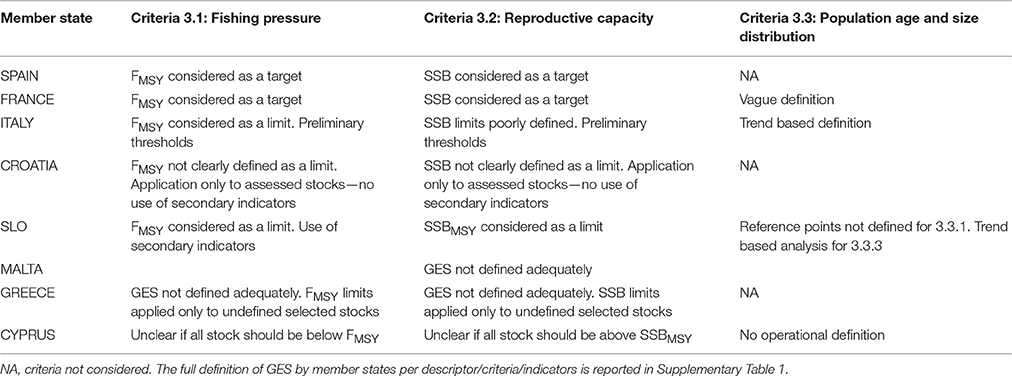

Most member states applied the IA and defined GES at the Descriptor 3 level or in relation to criteria 3.1 and 3.2. Conversely, for Criteria 3.3, only France, Italy, Slovenia and Cyprus provided some description of GES interpretation, which were quite vague in some cases (Supplementary Table 1). Three major discrepancies in comparison to MSFD criteria definitions and objectives emerge (Table 4):

1) A lack of specification of stocks to be considered (e.g., Greece).

2) Reference points for single stocks (e.g., FMSY) which were considered as targets and not limits (e.g., Spain and France).

3) A lack or preliminary definition of threshold levels; i.e., the percentage of stocks that need to be within safe biological limits to consider GES to be achieved (e.g., Italy).

Table 4. Main elements of discrepancies arising from the comparison between member states GES definition according to Descriptor 3 criteria in respect to MSFD criteria definition (EU-COM, 2010).

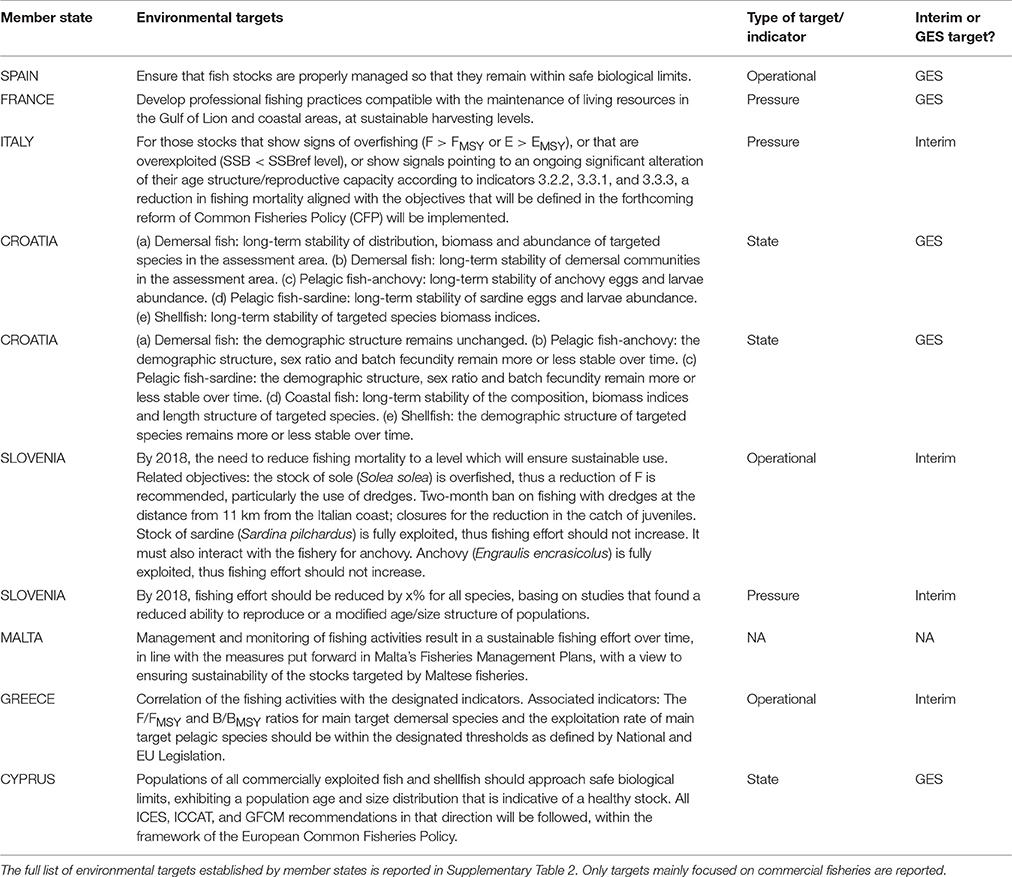

In total, member states defined 31 ETs referred to Descriptor 3 (Supplementary Table 2). Among the selection of those mainly related to commercial fishing practices, most of the ETs referred to GES achievement, while a smaller part represented interim targets (Table 5). However, the agreement with MSFD objectives was overall limited. These inconsistencies included:

1) A lack of detailed definition of stocks for which the target should be achieved (e.g., Spain, France, Slovenia, Greece).

2) The setting of objectives that are less ambitious than MSFD objectives and promote stability rather than improvement (where necessary) of stock status (e.g., Croatia).

3) The lack of clear definition of targets in relation to policies (such as the CFP) that still needed to be issued when ETs were proposed (e.g., Italy, Cyprus).

Table 5. Selected list of environmental targets defined by Mediterranean EU member states in the early phases of MSFD implementation.

Depending on the member state, targets not explicitly related to the GES definition and achievement were considered (Supplementary Table 2). These included the regulation of recreational fishing (i.e., Slovenia, Italy); the improved monitoring of biological resources (e.g., Greece, Cyprus); the establishment of MLS for selachians and the control of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUUF) (i.e., Italy); and the sustainability of artisanal fishing (i.e., France).

The MSFD represents an unprecedented effort to implement an ecosystem approach in marine waters in a large area like European marine waters, encompassing several countries and ecosystems, and establishing a holistic functional approach (Borja et al., 2010). This process was based on the definition of GES in relation to 11 descriptors, which consider the majority of marine ecosystem components and pressures. The Commission provided technical guidelines to support member states in MSFD implementation and fostered the coordination among member states and other countries thanks to the role of Regional Sea Conventions. Among the 11 MSFD descriptors, Descriptor 3 is not the only one connected to fisheries and their impact on the marine environment, with partial overlap with biodiversity, the marine food-web and seafloor integrity (Descriptors 1, 4, and 6, respectively). In this paper, we focused on Descriptor 3 related to commercial fish and shellfish and considered the approach and outcomes of the early phases of MSFD implementation. The focus was the Mediterranean Sea, an area that shows critical signs of overexploitation (Cardinale and Scarcella, 2017). Our analysis shows a potentially critical lack of coherence among member states in the implementation of the MSFD. Such inconsistencies can be observed at several levels, particularly: (i) the stocks selected for the implementation of the IA and the corresponding share of landings; (ii) GES definitions; and (iii) ET definitions.

Stock selection was uneven within the whole basin, with only a single species considered in all assessment areas, i.e., M. barbatus. A similar result emerged at subregional scale, with only 3–4 stocks in common among subregions. While limited consistency was observed at these levels, member states applied consistent approaches within the assessment areas they defined.

Owing to these discrepancies, it is clear that any IA would have resulted in inconsistent and incomparable outcomes (even in the case of identical analytical approaches applied to define GES and integrate data among assessment areas). Some member states selected a relatively large number of stocks for each assessment area, while others restricted their analysis to a more restricted pool. In the case of Croatia, the latter choice did not impede representing a large portion of landings, which was above 90%. This outcome is the effect of the high incidence of small pelagics in the total national landings, particularly S. pilchardus and E. encrasicolus.

Landings characterized by a high number of commercial species are typical of the Mediterranean Sea owing to the presence of multispecific fisheries and varied seafood cultural habits (Farrugio et al., 1993). This contrasts with the North-East Atlantic region, where there are a limited number of stocks for the bulk of landings. Moreover, in the Mediterranean Sea, about 80% of the fishing vessels are from small-scale fisheries, which have clear practical difficulties with monitoring their catches of local stocks (FAO, 2016).

When comparing the potential availability of data for exploited stocks arising from the EU DCF (EU, 2008) in the Mediterranean Sea with the number of stocks selected for the IA, it appears that only a small fraction of stocks monitored under DCF were considered. This mismatch could be partially due to the quality or availability of data, which can be affected by species with low catchability or high variability within standardized surveys, spawning periods not coinciding with data collection periods, relatively short time-series, etc. Such factors might have affected the possibility of estimating some indicators in relation to different MSFD criteria. It must also be considered that criteria adopted to select stocks within assessment areas influenced this outcome. For instance, Spain selected only species for which landings were above 1% of the total landings within the considered assessment areas. Other member states did not consider some species with large landings, as in the case of Chamelea gallina in GSA 17. All of this is linked to an uneven interpretation of the criteria for Methodological Standards (EU-COM, 2010), which requested that “all commercial species” be considered, explicitly referring to the scientific data collected under the DCF (EU, 2008).

However, we highlight that our estimates should be taken with some caution since they were based on FAO statistical data (apart from Italy) and are referred to 2011. These data could differ to some extent from national statistics or DCF data, which are usually not fully accessible at the GSA level. For instance, Spain reported covering about 70–90% of national landings per assessment area referring to average values 2008–2010. Such estimate includes species assessed by ICCAT (which were excluded in our analysis). These values are quite different from our estimations referred to 2011 landings (53% in total), even though we considered the same set of species. Moreover, Spain reported that out of the 29 and 27 stocks they selected in relation to GSAs 1–2 and 5–6, only in 22 and 23 stocks indicators were applicable, due to lack of data.

It is worth mentioning that after the initial steps of the MSFD were implemented (early 2013), member states defined monitoring programs to fill the gaps of knowledge that emerged, defined the programmes of measures, and in some cases had already refined the species list to be considered in their assessments. However, different approaches can be identified. For instance, in 2015, Malta increased the number of species to be considered, including taxa not previously considered (e.g., cephalopods). In contrast, in the process of carrying out the monitoring programs, Italy amended some previous definition of GES. In this context, Italy identified commercial species to be considered as “those under Reg. 1967/2006, provided that they belong to G1 and G2 MEDITS species or they are MEDIAS species” (free translation from Decree of the Ministry of Environment of 17 October 2014; Decree 2014; MEDITS: International bottom trawl survey in the Mediterranean; MEDIAS: Mediterranean Acoustic Survey on Small Pelagics). These new selection criteria would sharply reduce the number of stocks considered per assessment area in the forthcoming assessment to 11 stocks, in contrast to the average of 36 stocks that were included in the previous assessment (Table 3).

Further inconsistencies emerge when considering the definition of GES and ETs by member states. Overall, the definition of GES differed among member states and within subregions in relation to: (i) different interpretations or limited description of which stocks should be considered for GES assessment; (ii) whether to consider MSY-related reference points as targets or limits; and (iii) which shares of stocks should be within safe biological limits to achieve GES. Each of these items would produce different outcomes in terms of GES assessment and requirements to achieve GES. Indeed, applying different criteria for selecting stocks prevents member states from conducting assessments on similar stocks or similar shares of landings. At the same time, using MSY-related reference points as a target allows for the possibility of being above or below the reference point, which is less restrictive than setting the reference point as a limit. In addition, using different criteria to achieve GES in terms of the percentage or number of stocks that must be within safe biological limits would also have implications in the measures to be adopted to achieve GES. In this context, following a strict application of the MSFD criteria and methodological standards would have implied the inclusion of all stocks for which data are collected under the DCF in the assessment, the use of MSY-related reference points as limits, and the need to have 100% of stocks in safe biological limits to reach GES.

These discrepancies across member states clearly prevented a coherent definition of GES criteria. Moreover, only some countries adopted and defined GES in relation to secondary indicators, particularly for indicators of Criteria 3.3 (population age and size distribution). The latter case could possibly be linked to the lack of agreement on procedures to define reference limits to assess indicators of Criteria 3.3. Indeed, the recent advice proposed by ICES in relation to length-based indicators suggests that related indicators are not fully operational and that additional research will be needed to reach a consensus on defined reference levels (ICES, 2017).

Some member states applied GES estimation considering only assessed stocks, or in some cases applying secondary indicators associated with FMSY and SSBMSY as primary indicators. However, restricting the analysis to only stocks formally assessed under a quantitative stock assessment procedure would clearly restrict the share of landings subjected to GES assessment, especially in the case of the Mediterranean Sea. Indeed, although the number and range of stock assessments have increased in the last decade, the share of landings for which such assessments were available at the time of MSFD implementation ranged between 10 and 30% in three subregions (ISCM, WM, ALS), and up to 60% in the case of the AS.

The application of the Data Collection Regional Framework (DCRF) from GFCM might substantially improve such figure, reaching coverage between 40 and 60% for all subregions in relation to stocks for which assessment will be routinely carried out (GFCM, 2016; A1 list species). If such an approach will be extended to stocks not regularly assessed, such figures will increase to a range of 50–80% depending on the subregion (GFCM, 2016 A2 list species). Levels that are similar (yet different in relation to subregions) should be achieved in the future according to the application of the revised DCF (EU-COM, 2016).

The ETs set by member states might not be considered fully compliant with the MSFD expectations, as in the case of GES definitions. Again, the major reasons for such discrepancies are a lack of clarity on some definitions, a set of targets that are less ambitious than the MSFD objectives, or the reference to policies that were not already established when the targets were defined. Some member states justified the choice of not defining the percentage of stocks for which GES should be achieved by mentioning the intrinsic difficulties derived from ecosystem interactions and environmental fluctuations of having all commercial stocks simultaneously at MSY levels. Indeed, as pointed out by Link (2002), the sum of single species MSY is greater than MSY for the ecosystem, and it is energetically impossible to simultaneously maximize yield for multiple species. This issue was also acknowledged by Borja et al. (2013), who suggested revising the 100% threshold (i.e., all stocks should be in safe biological limits) and applying a lower operational threshold. The definition of such threshold would in turn affect the process of stocks selection moving from single stocks consideration to a proper ecosystem based approach implementation.

From our analysis, major inconsistencies among member states in the implementation of the IA and the definition of GES and ETs emerged at Mediterranean level. In contrast, at the national level, coherent approaches were applied in the case of several assessment areas, whether or not being displaced in one or more subregions. This in turn shows that the approaches were not appropriately coordinated at a subregional level as well.

In particular, the use of reference points based on MSY values as targets rather than limits is inconsistent with not only the MSFD criteria and methodological standards (EU-COM, 2010) but also with CFP objectives. However, it is worth mentioning that the latter were defined in 2013 after the MSFD was issued (EU, 2013). This lack of coherence reflected in ETs that are less ambitious than the MSFD policy objectives is likely to have hampered the potential synergies between MSFD and CFP.

As mentioned, member states sharing a marine region or subregion should have cooperated to ensure that the measures required to achieve the objectives of MSFD would have been coherent and coordinated across marine regions or subregions. In particular, existing regional institutional cooperation structures, including those under Regional Sea Conventions, were identified by MSFD as the tool for coordination between member states and other countries whose national waters are comprised within the same region or subregion and then for the enforcement of a regional approach to fishery management between EU member states and non-EU countries.

For this purpose, at the Mediterranean level and in the context of the Barcelona Convention, the UNEP/MAP established the Ecosystem Approach (EcAp) process, as agreed by the Conference of the Parties in 2008 (Decision IG17/6; UNEP, 2008) aiming to achieve GES in the Mediterranean by 2020. This process entails engaging all contracting parties (both EU and non-EU Mediterranean countries) in the definition of GES, related indicators, ecological objectives, and monitoring process. However, as pointed out by Cinnirella et al. (2014), differences between MSFD and EcAp are also evident because the latter has no financial support and applies to all Mediterranean countries. There is thus a high imbalance in terms of the economic development of countries involved compared to EU Mediterranean countries.

The lack of coherence in the MSFD implementation among Mediterranean EU member states (a problem that has emerged also in the context of other EU regions; van Leeuwen et al., 2014) also possibly derives from the difficulties in achieving a consensus among Mediterranean countries on indicators and methodologies to be applied for GES assessment within EcAp. Moreover, as shown by Freire-Gibb et al. (2014), there is uncertainty in the respective roles of different authorities responsible for executing the MSFD (i.e., the European Union, member states and Regional Sea Conventions), particularly in relation to their levels of authority, which might have been a key issue in preventing coordination among member states.

In the context of the Barcelona Convention, there has been a long revision process (that was also triggered by involving GFCM for technical support) of fishery-related ecological objective (i.e., Populations of commercially exploited fish and shellfish are within biologically safe limits; EO3). The definition of indicators as well as technical and data requirements has recently been subjected to strong improvements. Indeed, the 19th Meeting of Contracting Parties (Decision IG.22/7; UNEP, 2016) held in February 2016, adopted the EcAp-based Integrated Monitoring and Assessment Programme (IMAP) of the Mediterranean Sea and Coast and Related Assessment Criteria, for which EO3 (corresponding to MSFD Descriptor 3) is still to be consolidated. However, candidate indicators have been defined and include: SSB, total landings, F, fishing effort, catch per unit of effort or landing per unit of effort as a proxy, and bycatch of vulnerable and non-target species (UNEP, 2016). The involvement of GFCM in the definition of target species, fishing-related GES, common indicators, and ecological objectives has strengthened the coherence between EcAp-IMAP and MSFD objectives for Descriptor 3, even if there are still some differences in the defined process. In particular, no secondary indicators have been defined in relation to fishing pressure and SSB. However, the EO3 definition is now benefiting from the enforcement of the GFCM Data Collection Regional Framework (GFCM, 2016), which should boost data availability in the future in parallel to the new DCF (EU-COM, 2016).

The definition of stocks and data availability is only a part of the process to achieve regional and subregional coherence in GES assessment for Descriptor 3. Indeed, in our analyses, we did not consider methodological approaches adopted to assess indicators based on time-series and to aggregate information from multiple indicators and criteria from assessment areas to the national and subregional level. For the first item, many approaches could be applied (e.g., Spearman rank correlation, linear regressions, etc.; ICES, 2014b), and a regional coherence in the approach would be needed to ensure consistency. Coherence is also needed in regard to aggregation methods. As shown by Borja et al. (2014), the vast range of methods could result in inconsistent outcomes.

On May 17, 2017, the Commission Decision (EU) 2017/848 (EU-COM, 2017) was issued as an update of the former decision on criteria and methodological standards on GES of marine waters. This decision is aimed at improving the consistency of methodological approaches in relation to GES assessment. In relation to Descriptor 3 and when considering the Mediterranean subregion (Annex, Part I, EU-COM, 2017), several elements emerge in relation to the main issues we identified, i.e., the spatial scale, selection of stocks, interpretation of reference points, use of trend-based indicators, and criteria for the aggregation of information from several stocks.

In regard to the spatial scale, the Commission Decision states that “populations of each species are assessed at ecologically relevant scales within each region or sub-region, as established by appropriate scientific bodies referred to in Article 26 of Regulation (EU) No. 1380/2013 based on specified aggregations of GFCM geo-graphical sub-areas” (EU-COM, 2017). This statement clarifies that GSA aggregations could be considered and also assigns a role to the STECF in the definition of the appropriate spatial scale to be considered.

In relation to the selection of stocks to be included in GES assessment, “Member States shall establish through regional or subregional cooperation a list of commercially exploited fish and shellfish,” (…) taking into account Council Regulation (EC) No. 199/2008, “all stocks that are managed under Regulation (EU) No. 1380/2013; the species for which minimum conservation reference sizes are set under Regulation (EC) No. 1967/2006; the species under multiannual plans according to Article 9 of Regulation (EU) No. 1380/2013; the species under national management plans according to Article 19 of Regulation (EC) No. 1967/2006; any important species on a regional or national scale for small-scale/local coastal fisheries,” among others (EU-COM, 2017). This requirement should foster an increase in the consistency of stock selection for GES assessment within the Mediterranean Region and subregions. In this context, the role of the Barcelona Convention and GFCM will be essential to ensure that consistency will be achieved. However, the lack of clear specifications of a minimum requirement (e.g., % of landings, the number of common stocks) does not allow for current inference of how many stocks will be considered.

All three criteria (F, SSB, and age-size distribution) shall be considered, although it is recognized that data for age-size distribution might be not available for the 2018 assessment. Given the lack of consolidated reference points for related indicators, this condition will most likely result in an unbalanced application of this criterion among member states. Reference levels of F and SSB are mentioned as limits. Moreover, “In relation to stocks managed under a multiannual plan according to Article 9 of Regulation (EU) No. 1380/2013, in situations of mixed fisheries, the target F and the biomass levels capable of producing MSY shall be in accordance with the relevant multiannual plan” (EU-COM, 2017). This definition will increase consistency in the GES assessment for stocks for which analytical assessment is available, since the use of reference points as targets should not be an option. Moreover, it will increase the alignment with management plans established under the CFP. However, regarding stocks for which secondary indicators (i.e., catch/biomass ratio, and biomass related indexes) will be considered, “An appropriate method for trend analysis shall be adopted (e.g., the current value can be compared to the long-term historical average).” We highlight that without an agreed common analytical approach at the regional level for the application of trend analyses, high inconsistency is expected in the outcomes of the assessment of stock status evaluation.

Finally, the Commission Decision states that “the extent to which GES has been achieved shall be expressed for each area assessed as follows: (a) the populations assessed, the values achieved for each criterion and whether the levels for D3C1 and D3C2 and the threshold values for D3C3 have been achieved, and the overall status of the population on the basis of criteria integration rules agreed at Union level” (EU-COM, 2017). The criteria integration rules defined at the Union level are not yet specified, including in relation to methods of integration from assessment areas to subregional and regional levels (Zampoukas et al., 2014). Again, if no common agreement on the approach is achieved, it will prevent a consistent GES assessment at the Mediterranean level.

We analyzed and compared the approaches applied by EU Mediterranean member states in the early phases of the implementation of the MSFD in relation to commercial fisheries. What emerged is a lack of consistency in the selection of stocks, application of reference points, and definition of GES and ETs. MSFD criteria and methodological standards were applied with different interpretations across member states, showing that subregional and regional coordination was not effectively enforced. Moreover, only a partial use of potentially available data for GES assessment was identified, while new frameworks in relation to data collection (both at the EU and GFCM levels) suggest an increase in data availability for GES assessment for the future.

The recently reformed Commission Decision on criteria and methodological standards for GES (EU-COM) supports a more coherent approach to be applied in the forthcoming assessment of GES, which would also foster better coherence with the reformed CFP. However, several elements that could determine the uneven application of MSFD are still not completely clarified, particularly stock selection and criteria for the integration of GES assessment from stocks to assessment areas and subregions, as well as the methodological approach to the use of secondary indicators. The definition of a common, regional, and subregional approach is given to relevant regional and subregional cooperation bodies. Thus, their capability of defining and agreeing on a common, structured approach will be essential to ensure an even application of the MSFD in relation to commercial fisheries. However, since the next GES assessment will need to be carried out by 2018, there is an urgent need to implement such a process in the short term, and we hope this research will add to this framework.

Achieving consistency in MSFD implementation should also foster an improvement of stocks status in the Mediterranean region, which is lagging behind in comparison to the Northern-Atlantic countries in terms of tangible results (Cardinale and Scarcella, 2017). Ensuring that MSFD and CFP policies will be applied with the needed consistency at the pan-European level requires increased cooperation among scientists and member states from Mediterranean countries within GFCM and the Barcelona Convention, and collaboration between these institutions, ICES, other Regional Sea Conventions, and STECF/SGMED (Freire-Gibb et al., 2014; van Leeuwen et al., 2014).

Current data of F (Cardinale and Scarcella, 2017) suggest a low probability of reaching GES in the short term in the Mediterranean. Beyond the technical issues associated with GES definition and assessment, reaching this goal will also need better coordination among member states and other countries in relation to the definition of the programmers of measures, since the Mediterranean Sea is typically characterized by shared stocks (e.g., in the Adriatic Sea and Strait of Sicily). This is another complexity that adds to the multispecificity of fishing activities, the relevance of small-scale fisheries, and the political diversity of the area.

SR conceived the work. SR, PB, and TF collected data. TF and SR performed the analysis. All the authors wrote and revised the paper.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This research benefited from the experience of the authors obtained in the framework of ISPRA activities in relation to MSFD implementation. This research activity was partially supported by POR project in relation to fishery co-management. The definition of its goals benefited from the participation to several ICES WGs which was supported to SR as invited expert by ICES, which is gratefully acknowledged. We thank the reviewers for their insightful comments on the paper, which allowed us to improve the manuscript.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2017.00316/full#supplementary-material

Borja, A., Elliott, M., Andersen, J. H., Cardoso, A. C., Carstensen, J., Ferreira, J. G., et al. (2013). Good environmental status of marine ecosystems: what is it and how do we know when we have attained it? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 76, 16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.08.042

Borja, Á., Elliott, M., Carstensen, J., Heiskanen, A.-S., and van de Bund, W. (2010). Marine management-towards an integrated implementation of the European Marine Strategy Framework and the Water Framework Directives. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 60, 2175–2186. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.09.026

Borja, A., Prins, T. C., Simboura, N., Andersen, J. H., Berg, T., Marques, J. C., et al. (2014). Tales from a thousand and one ways to integrate marine ecosystem components when assessing the environmental status. Front. Mar. Sci. 1:72. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2014.00072

Cardinale, M., and Osio, C. (2012). Status of Mediterranean Resources in European Waters in 2012. Results for Stocks in GSA 1-29 (Mediterranean and Black Sea). Available online at: http://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/mare/document.cfm?action=display&doc_id=17391

Cardinale, M., and Scarcella, G. (2017). Mediterranean Sea: a failure of the European fisheries management system. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:72. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00072

Cinnirella, S., Sardà, R., Suárez de Vivero, S., Brennan, R., Barausse, A., Icely, J., et al. (2014). Steps toward a shared governance response for achieving good environmental status in the Mediterranean Sea. Ecol. Soc. 19:47. doi: 10.5751/ES-07065-190447

Coll, M., Piroddi, C., Steenbeek, J., Kaschner, K., Ben Rais Lasram, F., Aguzzi, J., et al. (2010). The biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: estimates, patterns, and threats. PLoS ONE 5:e11842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011842

Colloca, F., Cardinale, M., Maynou, F., Giannoulaki, M., Scarcella, G., Jenko, K., et al. (2013). Rebuilding Mediterranean fisheries: toward a new paradigm for ecological sustainability in single species population models. Fish Fish. 14, 89–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2011.00453.x

Crise, A., Kaberi, H., Ruiz, J., Zatsepin, A., Arashkevich, E., Giani, M., et al. (2015). A MSFD complementary approach for the assessment of pressures, knowledge and data gaps in Southern European Seas: the PERSEUS experience. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 95, 28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.03.024

EU (2000). Council Regulation (EC) No 1543/2000 of 29 June 2000 Establishing a Community Framework for the Collection and Management of the Data Needed to Conduct the Common Fisheries Policy.

EU (2006). Council Regulation (EC) No 1967/2006 of 21 December 2006 Concerning Management Measures for the Sustainable Exploitation of Fishery Resources in the Mediterranean Sea, Amending Regulation (EEC) No 2847/93 and Repealing REGULATION (EC) No 1626/94.

EU (2008). Council Regulation (EC) No 199/2008 of 25 February 2008 Concerning the Establishment of a Community Framework for the Collection, Management and Use of Data in the Fisheries Sector and Support for Scientific Advice Regarding the Common Fisheries Policy.

EU (2013). Regulation (EU) No 1380/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 on the Common Fisheries Policy, Amending Council Regulations (EC) No 1954/2003 and (EC) No 1224/2009 and Repealing Council Regulations (EC) No 2371/2002 and (EC) No 639/2004 and Council Decision 2004/585/EC Official Journal of the European Union (Brussels).

EU (2014). Regulation (EU) No 508/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and Repealing Council Regulations (EC) No 2328/2003, (EC) No 861/2006, (EC) No 1198/2006 and (EC) No 791/2007 and Regulation (EU) No 1255/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council.

EU-COM (2008). Directive 2008/56/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008 Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Marine Environmental Policy (Marine Strategy Framework Directive). Available online at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2008:164:0019:0040:EN:PD.Provisional

EU-COM (2010). Commission Decision of 1 September 2010 on Criteria and Methodological Standards on Good Environmental Status of Marine Waters (2010/477/).

EU-COM (2014). Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament. The First Phase of Implementation of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (2008/56/EC) The European Commission's assessment and guidance /* COM/2014/097 Final */

EU-COM (2016). Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2016/1251 of 12 July 2016 Adopting A Multiannual Union Programme for the Collection, Management and Use of Data in the Fisheries and Aquaculture Sectors for the Period 2017-2019 (notified under document C(2016) 4329).

EU-COM (2017). Commission Decision (EU) 2017/848 of 17 May 2017 Laying Down Criteria and Methodological Standards on Good Environmental Status of Marine Waters and Specifications and Standardised Methods for Monitoring and Assessment, and Repealing Decision 2010/477/EU.

EU-COM Annex (2014). Commission Staff Working Document. Annex Accompanying the Document Commission Report to the Council and the European Parliament The First Phase of Implementation of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (2008/56/EC) - The European Commission's assessment and guidance {COM(2014) 97 final}.

FAO (2016). The State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries. General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean. Rome.

Farrugio, H., Oliver, P., and Biagi, F. (1993). An overview of the history, knowledge, recent and future research trends in Mediterranean fisheries. Sci. Mar. 57, 105–119.

Freire-Gibb, L. C., Koss, R., Margonski, P., and Papadopoulou, N. (2014). Governance strengths and weaknesses to implement the marine strategy framework directive in European waters. Mar. Policy 44, 172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2013.08.025

ICES (2014a). Report of the Workshop to draft recommendations for the assessment of Descriptor D3 (WKD3R). Copenhagen, Denmark. ICESCM 2014/ACOM:50.

ICES (2014b). EU Request on Draft Recommendations for the Assessment of MSFD Descriptor 3. Special request, Advice March 2014. Section 1.6.2.1.

ICES (2017). EU Request to Provide Guidance on Operational Methods for the Evaluation of the MSFD Criterion D3C3 (Second Stage 2017). Special Request Advice Northeast Atlantic Ecoregion sr.2017.07. Available online at: https://www.ices.dk/sites/pub/Publication%20Reports/Advice/2017/Specialrequests/eu.2017.07.pdf

Link, J. S. (2002). What does ecosystem-based fisheries management mean. Fisheries 27, 18–21. doi: 10.1577/1548-8446-27-4

Tsikliras, A. C., Dinouli, A., Tsikliras, V. Z., and Tsalkou, E. (2015). The Mediterranean and Black Sea fisheries at risk from overexploitation. PLoS ONE 10:e0121188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121188

UNEP (2008). “Decision IG 17/6: Implementation of the ecosystem approach to the management of human activities that may affect the Mediterranean marine and coastal environment,” in 15th Ordinary Meeting of the Contracting Parties to the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Coastal Region of the Mediterranean and its Protocols (Athens).

UNEP (2016). “Decision, I. G.22/7: Integrated Monitoring and Assessment Programme of the Mediterranean Sea and Coast and Related Assessment Criteria,” in The 19th Meeting of the Contracting Parties to the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Coastal Region of the Mediterranean (Athens).

van Leeuwen, J., Raakjaer, J., van Hoof, L., van Tatenhove, J., Long, R., and Ounanian, K. (2014). Implementing the Marine strategy framework directive: A policy perspective on regulatory, institutional and stakeholder impediments to effective implementation. Mar. Policy. 50, 325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.03.004

Vasilakopoulos, P., Maravelias, C. D., and Tserpes, G. (2014). The alarming decline of Mediterranean fish stocks. Curr. Biol. 24, 1643–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.070

Zampoukas, N., Palialexis, A., Duffek, A., Graveland, J., Giorgi, G., Hagebro, C., et al. (2014). Technical guidance on monitoring for the Marine Strategy Framework Directive. JRC Scientific and Policy Reports. Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Keywords: Marine Strategy Framework Directive, Common Fisheries Policy, Good Environmental Status, Data Collection Framework, Data Collection Regional Framework, stock assessment

Citation: Raicevich S, Battaglia P, Fortibuoni T, Romeo T, Giovanardi O and Andaloro F (2017) Critical Inconsistencies in Early Implementations of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive and Common Fisheries Policy Objectives Hamper Policy Synergies in Fostering the Sustainable Exploitation of Mediterranean Fisheries Resources. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:316. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00316

Received: 17 March 2017; Accepted: 15 September 2017;

Published: 12 October 2017.

Edited by:

Sebastian Villasante, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, SpainReviewed by:

Konstantinos Tsagarakis, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, GreeceCopyright © 2017 Raicevich, Battaglia, Fortibuoni, Romeo, Giovanardi and Andaloro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saša Raicevich, c2FzYS5yYWljZXZpY2hAaXNwcmFtYmllbnRlLml0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.