95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 12 July 2016

Sec. Marine Conservation and Sustainability

Volume 3 - 2016 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2016.00120

This article is part of the Research Topic Fishing for human perceptions in coastal and island marine resource use systems View all 14 articles

This study offers a detailed analysis of community-based management (CBM) in a small island in Indonesia. In the study site, area-specific stewardship for a marine territory was informally institutionalized and, in addition to state rules, locally devised rules based on informal agreements have emerged. Using multiple methods for the analysis of the perceptions of the local community, this research examines the actual impact of the different rules on the fishing patterns in that sea territory, and illuminates the rationales of the local population to engage (or not) in the community-based approach to manage the marine resources. The study shows that the CBM initiative has to be seen as part of a convoluted regulatory system that impacts the fishing behavior in the sea territory. A lack of official authority to formally develop and especially to locally enforce rules represents a key challenges for the CBM initiative. This is further complicated by severe coordination problems between the local community and higher level state actors. The study further shows that the motivation of the community members to engage in the enforcement of the informal rules is strongly based on short-term economic considerations. For rules that are perceived to have a strong impact on the individual fishing yields, the fear of potential short-term economic losses constitutes a particular success factor of the local initiative since it motivates the members of the community to enforce local rules, especially when outside fishers break the rules. Yet, if rule-breaking is not perceived to decrease individual fishing yield, or if benefits of the generated yields are shared with the community as a compensation mechanism, the motivation of the community members to engage in rule enforcement ceases.

Concerns about the world's oceans and coasts are rapidly growing (Rockström et al., 2009; Burke et al., 2011; Visbeck et al., 2013; Zondervan et al., 2013). One of the most severe threats for marine ecosystems and their associated natural resources emanates from the unregulated and uncontrolled resource use, i.e., an open access situation (The World Bank, 2006). Open access to marine resources is common all over the world since rules, regulations and management are often either lacking or not effectively enforced (Agardy et al., 2005). Such an open access situation is widely assumed to lead to substantial sustainability deficits (Hardin, 1968; Ostrom, 1990; Agardy et al., 2005; The World Bank, 2006). The purpose of this article is to advance understanding of how to institute more effective community-based marine resource management in a small island setting.

Transforming an open access situation into any type of management regime requires the delineation of territory. While it appears to be more difficult to establish territoriality for marine areas than for terrestrial areas (The World Bank, 2006), research shows that it can be developed, legitimized and institutionalized (Kalikoski, 2007; Glaser et al., 2010). Marine territoriality implies area-specific stewardship coupled with legitimate rights to generate effective means based on formal and/or informal authority that steer human behavior in a specified sea area (Jones, 2014). In this regard, the concept of Common Pool Resource Regimes (CPRR) offers a useful point of departure (Ostrom, 1990; Young, 2006). The related literature holds that, apart from an open access situation, there are three proto-types of CPRR. These include the state CPRR, the private CPRR and the communal CPRR (Bromley and Cernea, 1989; Ostrom, 1990; Pomeroy and Berkes, 1997; Pomeroy and Rivera-Guib, 2006). In a “state CPRR,” the state assumes control over the resources or specified territories. Individuals and groups can only use the resources with the consent of the state and must comply with the regulations made by government laws. The state can grant the right to exploit resources to individuals or groups, but control over the resources is exercised by the state (i.e., by government agencies; Bromley and Cernea, 1989). A “private CPRR” refers to the exclusive possession of an area or a set of resources by private entities. Such private entities may not necessarily be individuals, but private ownership can also be transferred to clearly defined groups (corporate private property; Bromley and Cernea, 1989). In a private CPRR, the control over a specified territory, its resources and its products is given to private entities (owner). They hereby gain the right to exercise their rewarded power to exclude others from the use of their terrain or prevent usage of their resources from non-owners. The third category is the “communal CPRR” which has attracted particular attention over the past decades (cf. Dearden et al., 2005; Berkes, 2007b). Such a community-based management (CBM) approach describes a management system of a clearly defined group of people for a set of natural resources or a particular area (Berkes, 2010). Since CBM encompasses many different management situations in which natural resources, whole ecosystems or territories are “owned” and managed by local groups, there is no general definition available. Yet, the quintessence of CBM is that management authority for a defined territory or set of resources is transferred to, or rests with, a clearly defined group at a local level, which shares certain common characteristics (e.g., ethnicity) or commonly resides in a geographical area (Armitage, 2005).

Especially in tropical nations with weak state institutions, CBM has become a popular alternative approach for marine resource management. This is based on the notion that local actors are better suited to devise rules for addressing the roots of marine resource degradation (such as overfishing or the use of destructive fishing gears) than command-and-control approaches and other centrally organized solely government driven approaches (Ruddle, 1999; Ferse et al., 2010, 2014; Cinner et al., 2012). In fact, local communities all over the world have been involved in self-organized approaches to managing natural resources for centuries, and the idea of CBM originated from the acknowledgement of the effectiveness of such indigenous and traditional management systems for natural resources (Wade, 1988; Ostrom, 1990; Hidayat, 2005; Berkes, 2007a). A variety of management regimes for the sustainable use of natural resources has thus emerged based on local decision-making structures and formal or informal rules to secure the long-term socio-economic well-being of local populations (Borrini-Feyerabend et al., 2004, and references therein). The strength of such collaborative local endeavors is that communities can create solutions to local natural resource use problems, which are tailored to the particular local socio-cultural and environmental circumstances (Alcala, 1998; Armitage, 2005; Pomeroy and Rivera-Guib, 2006).

Yet, it is also widely acknowledged today that CBM is not a one-size-fits-all solution to successful marine resource management (Berkes, 2004; Cudney-Bueno and Basurto, 2009; Cinner et al., 2012). Rather, CBM approaches for natural resources harbor a series of hazards and cannot be assumed to be a “panacea” or “blueprint” for successful natural resource management. Various studies have shown that their risk of failure is high (cf. Berkes, 2007b; Christie and White, 2007; Cudney-Bueno and Basurto, 2009; Cinner et al., 2012; Adhuri, 2013). Moreover, it cannot be simply assumed that if government actors endorse the development of CBM initiatives, new and effective rules will automatically emerge for successful CBM of natural resources (Schlager and Ostrom, 1992, 1999). Berkes (2004, p. 623) highlights in this regard that a “community” is a complex, elusive and multidimensional construct under constant change. Even small communities, therefore, cannot be seen as a unitary actor who per se acts toward the long-term benefit of the entire community. Rather, every community, whether small or large, is characterized by internal divergences of interests because any community is made up of various individuals and groups, which are embedded in larger systems and affected by influences from the outside (Berkes, 2004). Further empirical research is thus needed to better understand under which circumstances local initiatives can lead to improved sustainable marine resource use in a certain sea territory, and when CBM faces strong difficulties.

Many studies have focused on the design of successful and persistent institutions in a self-organized CBM context that effect more sustainable resource use among the members of a community (cf. Wade, 1988; Ostrom, 1990; Cinner et al., 2012). Much less empirical research is available with regards to implementing CBM in the context of a regional resource use system, and in relation to CBM as part of a nested rule system to regulate resource use in a particular sea territory. In order to contribute to fill this gap, this study empirically investigates a CBM regime for the sea area surrounding Langkai Island, a small island located in the Indonesian Spermonde Archipelago off the coast of Makassar City. The objective of this research is two-fold: First, the study aims to provide a detailed analysis of what rules produced by which CPRR type actually have an impact on the fishing patterns in the sea territory as perceived by local resource users, and to illuminate potential challenges associated with implementing the rules generated by the different CPRR. The second objective of this article is to examine what motivates the local resource users to engage (or not) in the CBM of the marine resources. This article hereby complements previous more general work on CBM and informal rules in the Spermonde Archipelago by Deswandi (2012), Glaser et al. (2010, 2015) and Idrus (2009).

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. The subsequent section provides an introduction of the study site, which outlines the particular fisheries related problems encountered and illuminates the presently implemented means to address them. Next, the methods applied in this research are described. The article then turns to the results. There, the article first focuses on understanding what rules actually affect the fishing patterns in the sea territory surrounding the study island based on the exploration of the perceptions of local fishers. The following section of the results then examines the rationales of the local fishers for engaging (or not) in the CBM initiative. The results are then discussed and put in a wider context. The article concludes with highlighting the main findings of the study and indicating further research needs to improve CBM initiatives for marine resource management.

Indonesia is located within the Coral Triangle, one of the world's marine biodiversity hotspots (Burke et al., 2011). The country has about 81,000 km of coastline comprising about 4000 ha of mangrove forests and the national territory encompasses 5.8 million km2 of sea area, of which ~51,000 km2 contain coral reefs (Syarif, 2009). The marine waters and its natural resources are of fundamental strategic, economic and environmental importance for Indonesia (Cribb and Ford, 2009). Yet, as a result of myriad anthropogenic pressures (Syarif, 2009), Indonesia is expected to experience the strongest decline in fisheries of any nation worldwide (Cheung et al., 2010). This is most severe for the people living in rural coastal areas and small islands, putting the livelihood security of millions of people at jeopardy (Ferrol-Schulte et al., 2013, 2015).

In order to effect more sustainable resource use in Indonesia, a number of laws have been developed in an attempt to regulate the use of the country's fishery resources (cf. Syarif, 2009). These include for instance the ban of destructive fishing gears such as poison and blast fishing, and legislation to support the development of marine protected areas (Ferrol-Schulte et al., 2015). Yet, the different laws pertaining to the regulation of fisheries appear to only have little traction on the ground (Satria and Matsuda, 2004; Radjawali, 2012; Wever et al., 2012). Despite the existence of numerous Indonesian laws in the environmental realm, there have been only very few cases of effective enforcement through courts nationwide (Waddell, 2009). Especially in areas far away from larger towns and cities, the enforcement of government rules including the prohibition of blast and poison fishing by enforcement agencies is highly difficult.

This study focuses on Langkai Island, a small island located at the outer margins of the Spermonde Archipelago, South Sulawesi (see Figure 1). The archipelago consists of ~80–100 small islands inhabited by about 35,000 people (Sab and Katsuya, 2008). The islands greatly differ in terms of socio-economic characteristics (Glaeser and Glaser, 2010). The Spermonde Archipelago is home to one of the largest reef fisheries in Indonesia (Pet-soede and Erdmann, 1998). Due to the physical characteristics of the islands, which hardly permit any land-based livelihood activities (Schwerdtner Máñez et al., 2012), fishery resources are of fundamental importance to provide the households in the archipelago with monetary and subsistence income (Pet-Soede et al., 2001; Glaser et al., 2015; Miñarro et al., 2016).

Yet, similar to other areas in Indonesia and elsewhere in South-East Asia (Burke et al., 2011), the fisheries resources in the Spermonde Archipelago are increasingly depleted (Glaeser and Glaser, 2010; Glaser et al., 2010; Ferse et al., 2012) and the coral reef ecosystems are heavily degraded (Edinger et al., 1998; Plass-Johnson et al., 2015a,b, 2016). This jeopardizes the livelihoods of thousands of people as an ever growing number of fishers in the archipelago competes for increasingly scarce marine resources (Glaser et al., 2010; Deswandi, 2012; Miñarro et al., 2016). Moreover, unsustainable and destructive fishing practices including blast and poison fishing are used all over the archipelago and pose a major threat to the viability of marine resources and marine ecosystems (for more details on destructive fishing and its consequences on the marine ecosystems in the Spermonde Archipelago see esp. Pet-Soede et al., 1999; Chozin, 2008; Wilkinson, 2008; Idrus, 2009; Ferse et al., 2014; Pauwelussen, 2015).

Effective means for more sustainable marine resource use are thus urgently needed to address this development. Unlike elsewhere in Indonesia, traditional customary fishery management systems such as the sasi laut in the Maluku Archipelago, for instance described in detail by Novaczek et al. (2001), are not found in the Spermonde Archipelago. Yet, in addition to official government laws, informal means to organize marine resource use have emerged in the Spermonde Archipelago. Today, local agreements between fishers (locally called kesepakatan) constitute informal rules, which have developed over time, and contribute to organizing the fishery in several areas in the Spermonde Archipelago (Glaser et al., 2010, 2015), including the sea territory around Langkai Island.

The research applies a mixed-methods anthropological research approach to advance understanding of how to institute more effective community-based marine resource management in a small island setting. The study was conducted as part of the third phase of the joint German-Indonesian research program SPICE (Science for the Protection of Indonesian Coastal Marine Systems, 2012–2015) and builds upon the research conducted during the second phase of the SPICE program (2007–2010). Data for this study were collected over a 6 month field research period in the Spermonde Archipelago area from September 2012 to March 2013. Three visits of about 2 weeks each to Langkai Island were carried out. Further islands, including Lanyukang Island, Barrang Lompo Island, Lumu-Lumu Island, and Barrang Cadi Island, which are located in close vicinity of the study island (up to 2 h by boat), were visited for shorter time periods of about 2–5 days. In addition, a number of interviews with government officials on Sulawesi were conducted for the purpose of this study. Prior informed consent was obtained from all informants in this study. Moreover, the research was conducted in accordance with all ethical standards outlined in the Amended and Updated White Paper on Safeguarding Good Scientific Practice by the German Science Foundation [Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), 2013]. The following section outlines the different methods used in this research (for more details on the methods see Bernard, 2006).

Using a semi-structured interview outline with open-ended questions, in-depth interviews were conducted with 69 informants on Langkai Island, on other small adjacent islands whose inhabitants frequently fish in the Langkai Island area, and government officials in Makassar City. The vast majority of respondents in all islands were fishers, but interviews were also conducted with traders and island officials with functions in the local administration structure1 (for details see Table 1). In addition, interviews were carried out with government officials in Makassar City from the Water Police, BAPPEDA (Badan Perencana Pembangunan Daerah, responsible for marine spatial planning) and DKP (Dinas Kelautan dan Perikanaan, responsible for fisheries and marine conservation). Usually, an informant was not only interviewed once but visited several times over the 6 months research period to inquire about different topics related to this study. Especially on Langkai Island, about eight informants served as central informants and conversations were held almost every day during the time spent on the island. In general, all interviews focused on understanding the development of the Langkai Island economy, changes of the social, economic and ecological circumstances, the different mechanisms in place that aim at organizing the appropriation of fishery resources in the sea territory surrounding Langkai Island, the impacts of these mechanisms on fishing behavior, and the reasons why some mechanisms work better than others. The particular topics covered in each interview were aligned to the expected knowledge of the informant, and sometimes adjusted to the actual knowledge of the interviewee. Except for the interviews with government officials, with whom more formal interviews were conducted, the interviews in the islands were not conducted as formal interviews since the topics covered highly sensitive matters such as the involvement in illegal fishing activities. Rather, after announcing the topic of this research, the intended use of the information, assuring anonymity to the individual respondents and obtaining informed consent from the informants, the interviews were carried out as informal conversations on the topic of the research to build as much trust as possible. Small groups of fishers, or individual fishers, were randomly approached at their homes or in public places in different areas of the small islands. Sometimes, upon recommendation by other island inhabitants, certain individuals were visited and asked to participate in the interviews because of their key role in CBM, or their anticipated in-depth knowledge of a particular aspect of the research. None of the conversations was recorded to further ensure an informal atmosphere and anonymity of the informant. Instead, particular effort was given to accurately document the content of the conversation in field notes during and after the conversations. All interviews were conducted by the author of this article with the help of a research assistant, who is a native speaker of the different local languages used in the area and has extended experience in working with the island communities on marine resource management in the Spermonde Archipelago and nearby areas. Where applicable, information received in one interview were triangulated in various interviews in the study island, on other islands, and on the Sulawesi “mainland” to verify data and cover a wider range of perspectives.

Participatory observation is a research method mainly used in cultural anthropology (Bernard, 2006). For this study, it was used to learn about social processes the interviewees may not be aware of, or are reluctant to talk about, and to further triangulate information obtained otherwise. The scope of participant observation in this study was limited, however, and only included attending relevant official meetings and informal gatherings, as well as observations of fishing behavior in the waters surrounding the island.

An adapted version of the participatory research method “Net-Map,” described in detail by Schiffer and Hauck (2010), was used for this study. The method allows to visualize knowledge about the interplay of complex formal and informal social relations, the influence different actors exert on resource use patterns, and to unveil the social processes in natural resource management (cf. Gorris, 2015; Hauck et al., 2015). Two Net-Maps were developed in group interview sessions with fishers. The social relations that influence the fishing pattern in the Langkai Island waters, as perceived by the participants, were mapped. One group session was conducted with fishers from Langkai Island and the other group interview session was carried out with fishers from another nearby community in Barrang Lompo Island, who were well-known for using illegal fishing methods. On Langkai Island, the Net-Map group was composed of eight participants. On Barrang Lompo Island, the Net-Map session consisted of six participants. It was not intended to ensure a representative sample of the respective island in these interviews, but rather to ensure that the interview participants had long-standing experience of fishing in the sea area around Langkai Island, and possessed in-depth knowledge on how the fishery in the area is organized. Hence, all interview participants in both Net-Map sessions were fishers who frequently fished in the sea territory surrounding Langkai Island and were thus equipped with in-depth knowledge of the organization of the fishery in the area. Moreover, it was sought to include representatives of the wide variety of different fishing gears used in the Langkai Island sea area. Potential candidates meeting these requirements were identified prior to the Net-Map session based on recommendations by key informants, or were key informants themselves as described above. Potential candidates were contacted at their residences, or their fishing boats after fishing trips. Yet, eventual participation in the Net-Map group interview depended on the availability and interest of the fisher.

The Net-Maps were developed in a three-step process. A large sheet of paper was placed in front of the netmapping group. In a first step, the participants were invited to think of all actors that either are affected by, or themselves affect the management of natural resources in the waters surrounding the study island, i.e., who fishes in that area using what gear type, or who has an influence on the marine resource use patterns in the area. The identified actors were noted on cards and glued on the paper. In a second step, the netmapping group described who exercises influence affecting another actor. Influence of one actor toward another actor was indicated by an arrow on the paper. In a third step, the netmapping group participants were asked to judge how much influence they considered the different actors to have on the way marine resources are used in the area. A scale between one and four (four representing the highest possible influence) was used to determine the degree of influence of the respective actor. Discussions on the reasons for the thus constructed map followed. The netmapping approach, as adapted and used in this study, offers the opportunity to advance understanding of the de facto marine resource management through the visualization of social relations that affect marine resource use in the Langkai Island sea area. Data was digitalized and visualized using the social network analysis software Gephi.

The study was complemented by the results of a survey (for details see Supplementary Material in the online version of this article) with fishing households to provide socio-economic context data for Langkai Island (see Section Langkai Island: Fueling the Local Economy). The survey was conducted by a team of German and Indonesian researchers in several islands in the Spermonde Archipelago. This article only draws on the results of the survey interviews conducted on Langkai Island. A geographically stratified random sampling was used for selecting the respondents. Thirty-eight survey interviews were conducted representing about 20% of the island's fishing households. The survey participants were the household heads (all male). The households were selected in a lottery system from a list of fishers. Only descriptive statistics was used since the low absolute number of participants in the survey from Langkai Island does not allow for in-depth statistical analysis.

At the end of the 1940s, only 10 people who were all fishers permanently lived on Langkai Island. During that time, the main fishing gear used by these fishers was hand-line and the most important targeted species was the Narrow-Barred Spanish Mackerel (Scomberomorus commerson, called Tenggiri in local language). Today, the island population has grown to 225 households of which 190 (~84%) rely on fishing as their primary and mostly only source of income. This reflects the fundamental importance of marine resources to secure the local livelihoods.

The results of the survey show that numerous fishing gears are used by Langkai islanders today (see Figure 2). Depending on the season, most fishers used different gear types during different times of the year. Yet, hand line still has remained the most commonly used fishing gear to target a variety of fishery resources (used by 41% of the fishers). The second most commonly used fishing gear is gillnet, used by 32% of Langkai Island's fishers. Further gears used include driftnet, fish trap, mobile lift net, and compressor diving, while some other gears were only used to a minor extent. Despite the introduction of new fishing gears over the past 50 years, which allowed the islanders to target a wider range of fishery resources, the hand-line fishery has remained particularly important for the local economy. The continuous importance of the hand-line fishery is due to the high abundance of economically valuable species in the area that can be caught by hand-line, and especially the occurrence of the Narrow-Barred Spanish Mackerel (which can be sold for ~50–70,000 IDR2 per kilo) in the sea area surrounding Langkai Island.

Yet, the lucrative target fish, such as Mackerel, are unevenly distributed over the Spermonde Archipelago. Moreover, the increasingly depleted fish stocks and degrading fish habitats in the Spermonde Archipelago and the neighboring areas have motivated fishermen to search for fish in other areas than only the waters of their home islands. The sea territory surrounding Langkai Island has remained a particularly rich fishing ground where a wide range of valuable marine resources are still available. Hence, the area is not only subject to exploitation by local fishers from Langkai Island, but attracts many fishers from other islands and Sulawesi mainland fostering the competition for the valuable resources in the area.

Whilst not officially marked by flags or buoys, the “Langkai Island Waters” is a commonly acknowledged and relatively clearly defined marine territory surrounding the island. All interviewees from Langkai Island and from elsewhere, who frequently use the area for fishing, knew and acknowledged this. The interviewees were able to relatively precisely draw the borders of this area on a very large naval navigation map, and to describe the borders mainly based on aspects of the underwater topography and distinct features of the marine ecosystem. Since the area is perceived to belong to the island, the local community considers itself entitled to institute rules for the use of the area's fishery resources. Based on informal agreements, three locally devised rules were instituted for the use of marine resources in the Langkai Island Waters. These include the prohibition of (a) blast fishing, (b) poison fishing, and (c) the use of spear-guns for Mackerel fishing.

The surveillance and enforcement of these local rules were carried out by the local resource users. In addition, an important role in the sustained implementation of these rules and for controlling what gear is used in the waters, so it was argued in the interviews, attributes to the elected island leader (Ketua Rukun Warga) to gain improved authority in rule enforcement. Yet, neither the local community in Langkai Island in general nor the island head in particular have a formal authority to develop and enforce such locally devised fisheries management rules for the Langkai Island Waters since the necessary official authority (by law) does not extent out to the sea territory, but only accrues to organizational matters on the community's land. As for the prohibition of blast and poison fishing, i.e., for the rules also found in national law, the enforcement of these rules for the Langkai Island Waters thus relies on the cooperation with the Water Police based in Makassar City. This is a difficult situation, so it was argued in the interviews, as the islanders do not hold official authority to detain rule-breakers until the police arrives. With regards to the spear-gun rule, there is no legal basis at all and the Water Police is not entitled to engage in enforcing this rule. Hence, the remaining option for the islanders to enforce all three rules at the local level is to apply alternative informal means for enforcement. Common practice is that, if somebody is spotted in the Langkai waters who uses or is suspected to use gears, which are prohibited by the local rules for the marine territory, fishers form a group, ideally with the island leader among them, and inform the respective fisher about the rules that apply to the Langkai Island Waters. Usually, according to the islanders, this is sufficient to scare the fishers away. If not, Langkai islanders may also throw stones at the rule-breakers. This common enforcement practice was also widely confirmed by fishers from other islands, who fish in the Langkai Island area, and whose inhabitants are particularly famous for fishing with bombs, poison and spear-guns. In fact, it was stated in the interviews in other islands that the interviewees heard that the fishers of Langkai Island would even confiscate the fishing gears, or set fishing boats on fire, which both would cause severe economic loss for the fishers. While it was widely confirmed in the Langkai Island community and elsewhere that stones are used to scare rule-breakers away, the more drastic measures may also be a legend spread in the area.

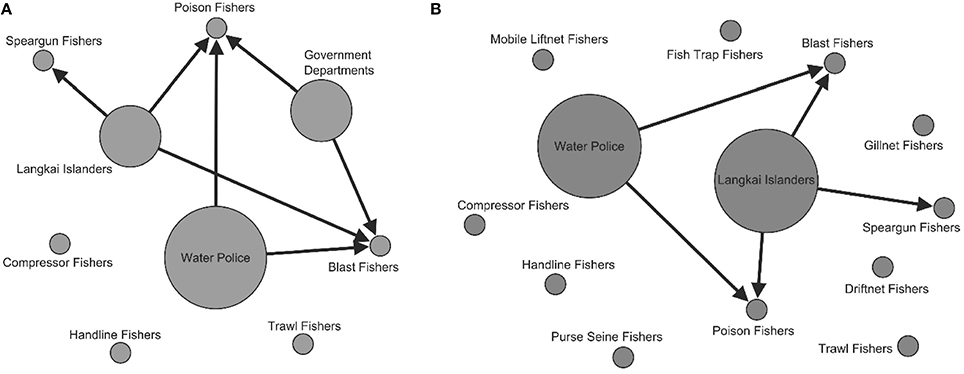

This section illuminates the perceived impact of the rules produced by the state CPRR and the CBM3 on the fishing practice in the Langkai Island Waters based on the two Net-Map group interview sessions. Figure 3A shows the results of the group session with Barrang Lompo Island fishers, and Figure 3B shows the results of the session with Langkai Island fishers.

Figure 3. Managing marine resources in the Langkai Island Waters. The figure shows the perceived impact of the state CPRR and the CBM on marine resource use in the Langkai Island Waters based on the Net-Map group interviews with fishers from Barrang Lompo Island (A), and with fishers from Langkai Island (B). The arrows indicate that an actor exercises influence toward another actor in the Langkai Island Waters. The size of the dots is scaled to the perceived influence of the actor on resource use in the area on a scale between 1 and 4 (the larger the dots, the higher is the perceived influence).

Both groups identified fishers using different gear types in the Langkai Island Waters (for details see Figure 3). The fishers of Langkai Island created a more detailed picture of the fishing gears used in the area, which is certainly due to their more in-depth knowledge of the marine resources use patterns close to their island. With regards to who has an influence on marine resource use patterns in the area, both groups identified the Water Police (which is based in Makassar City) and the local community in Langkai Island. The notion of the Langkai islanders in both group sessions represents their influence on marine resource use patterns in the Langkai Island Waters. Government departments, and particularly the Department of Fishery and Marine Conservation (DKP), were only mentioned to have an impact by the Barrang Lompo Island group. The interview participants from Langkai Island did not see their direct influence on the resource use patterns in the Langkai Island Waters. This may be explained by the fact that Barrang Lompo Island is relatively close to Makassar City, where the government departments reside. Due to this proximity, and maybe also due to the fact that the Barrang Lompo Island residents are well-known throughout the Spermonde Archipelago for using destructive fishing, government programs such as awareness raising campaigns frequently target fishers from Barrang Lompo Island, whilst such activities occur very rarely on Langkai Island.

Both groups argued in the interviews that the Water Police has a strong influence on poison and blast fishers (influence is marked by arrows in Figure 3), who attempt to fish in the area. The Langkai Island community was also found to affect these two types of fishing operations as a result of the informal agreements for this specific portion of marine territory. Moreover, the Langkai Islanders also influence the use of spear-gun fishers as, based on the local rules, they are not allowed to fish for Mackerel in that area. Hence, in the view of the both Net-Map groups, both government actors and the island community contribute to regulate marine resource use in the Langkai Island Waters.

Participants of both sessions agreed that the Water Police has the maximum possible influence (indicated by the size of the dots in Figure 3) on the resources use patterns in the Langkai Island Waters due to their official power of apprehending fishers using illegal gears. Despite the fact that illegal fishers will most probably not be prosecuted in court, participants in both groups argued that, if caught by the Water Police, illegal fishers will still spend some days or even weeks in jail during which they cannot generate income for their family, and that they also have to spend a significant amount of money for their release. This means a substantial financial loss for these fishers. However, it was argued in both sessions that, while the Water Police generally exerts strong influence on the resource use patterns, patrolling only occurs rarely in the general Langkai Island area, as it is far from the police station in Makassar City, and patrolling the area requires high financial input in terms of gasoline. In addition, the large Water Police boats are visible from a long distance and, if they are in the area, fishers will not carry out any illegal fishing operations. Therefore, while the general influence of the Water Police in terms of deterring blast and poison fishing when in the area is considered high, their actual impact on avoiding illegal fishing operation in the Langkai Island Waters is limited due to their rare presence in the area. By the participants of the Barrang Lompo Island group, the other government actors were perceived to be less influential compared to the Water Police. It was argued that the influence of the other government actors stems from the awareness raising campaigns about the danger of blast and poison fishing, which led some of the respective fishers to reconsider their fishing practice.

The perception on the influence of the local community on Langkai Island on the resources use patterns in the area slightly varies between the Net-Map sessions conducted in the two islands. The Barrang Lompo Island interview group saw less influence of the Langkai Island community compared to the Water Police. In contrast, the Langkai Island interview group also perceived the island community to have maximal influence. Participants in the Langkai Island group argued that they can develop rules for the area, which are complied with by the fishers from Langkai Island itself, and also by the majority of outsiders. Yet, the participants also highlighted that their means of actual enforcement is limited as they do not possess legal enforcement authority. The Langkai Island group reported that the cooperation with the police “is not always easy” as the police may be in other parts of the Spermonde Archipelago, or elsewhere, and may not come to Langkai Island, even upon request by the islanders. Therefore, Langkai Islanders usually rather tend to only scare rule-breakers away from the area instead of detaining them and cooperate with the police. The participants in the Barrang Lompo Island group argued along similar lines but especially highlighted that the islanders do not possess official authority to enforce rules in the Langkai Island Waters and, therefore, awarded the local community in Langkai Island with less than the maximum amount of “influence points.”

The support of local initiatives and the active engagement of a high share of the community in the enforcement of the related rules is a necessary precondition for a functioning rule system. This section illuminates the rationales behind the motivation of local fishers on Langkai Island to engage in the enforcement of the locally devised rules. Table 2 at the end of this section summarizes the fishers' rationales for engaging in the enforcement of the local rules.

Blast fishing is widely used in the Spermonde Archipelago. While there was also a more frequent use by fishers from Langkai Island up to the 1990s, today, only one fisher sometimes uses small bombs. The fishing practice by this fisher is despised by the other community members, but it was argued in the interviews that the other fishers cannot do much about it, except for trying to keep the fisher from operating the bombs in the Langkai Island Waters. Whilst a number of people on Langkai Island reported that they are also very strict on enforcing the blast fishing prohibition, in fact, other fishers reported that they tend to remain “inactive” in the enforcement of this rule and rather tolerate the use of blast fishing in the Langkai Island Waters for four main types of reasons.

(1) Issues in enforcement: In addition to the previously described issues related to the coordination with the police, another problem with the enforcement of this rule was highlighted in the interviews. If fishers use illegal fishing gears or act suspiciously, and Langkai islanders want to search their boats for illegal fishing gears, a common problem relates to the fact that the fishers who use explosives for fishing frequently have boats with stronger engines than the Langkai Island fishers with their rather simple and small boats. The blast fishers thus usually can escape before the Langkai islanders get the chance to come aboard. While the overall goal to prevent fishers from using blast fishing in the Langkai Island Waters is hereby achieved, this adds to the problem of cooperation with the Water Police since the islanders can rarely detain blast fishers. According to the interviewees, the overall problematic enforcement situation decreases the motivation of trying to catch blast fishers since it is often perceived as “not to be worth the effort.”

(2) Reciprocity: Reciprocal hospitality represents an important aspect in the wider Spermonde Archipelago. In case fishers come from distant areas during their fishing trips to the prosperous fishing grounds of Langkai Island, or go fishing in the open water beyond the shelf of the Spermonde Archipelago platform, fishers stay overnight in the Langkai Island area. The local term Sawakung refers to layovers in foreign islands or on their boats adjacent to the island during fishing trips. They are of mutual benefit for the guest and the host. While outside fishers are provided with shelter, goods and services in the host island, these layovers hereby generate additional revenues for the Langkai Island community. Moreover, these stays facilitate knowledge exchange between the islanders and outsiders. Despite the rich fishing grounds in the Langkai Island area, some of the fishers from Langkai Island sometimes themselves perform long-distance fishing trips to other fishing grounds, and have to do layovers in the nearby islands. The interviewees in Langkai Island expressed concerns that, if they engage in trying to detain or scaring rule-breaking fishers such as blast fishers away, they would deny the outside fishers access to the fishing area. This would create problems for the Langkai fishers in case they themselves needed to visit the home island of these outside fishers for a layover. Langkai fishers thus feared that their engagement in rule enforcement would seriously affect their fishing operation in a negative way if they were not able anymore to visit the fishing grounds close the respective islands where the Langkai fishers themselves relied on the goods and services offered by the host community. Another more general worry with regards to reciprocity was that the fishers using illegal fishing gears are believed to have very good relations with “important people” in Makassar City, which is why blast and poison fishers most probably will not be prosecuted for illegal fishing. Moreover, interviewees feared that they themselves would “get problems” if handing over illegal fishers to the police since it might be taken as an offense by “the important people in Makassar” to apprehend fishers who are under their protectorate.

(3) Lack of perceived strong negative impact on own fishery yield: Almost all hand-line fishers, who target Mackerel, perceived that blast fishing operations would not have severe negative consequences for their own fishing. The Mackerel is no target fish for blast fishing. Interviewees highlighted that Mackerel only occurs in small groups of few individuals while blast fishers only target schools of fish to increase the profitability of the blast fishing operation. Moreover, it was stated that the Mackerel moves too fast to be caught by a bomb operation. The blast fishers thus can only catch Mackerel accidentally, which was referred to as “a lucky accident for them,” but not on purpose. It further seems to be commonly perceived that the Mackerel spawns on the seafloor, whilst the bomb is not operated close to the seafloor due to the danger of particles that may be expelled from the water by the explosion. Blast fishing is thus believed to also not affect the Mackerels' spawning grounds. For that reason, the fishers argued that blast fishing has limited effects on the abundance of their target fish, and its spawning grounds. As a result, the blast fishing is seen not to have severe negative consequences on their yields. Similarly, the gillnet fishers also saw no direct negative impact of blast fishing on their yields, for the same reasons4.

(4) Benefit-sharing: A strong argument produced in the interviews was that there is a general understanding in the Spermonde Archipelago that, if the blast fishers operate a bomb, everyone who is nearby can assist the blast fishers in collecting the “harvested fish,” of which a helper would get a share of one out of three parts of the fish collected by him (see also description by Chozin, 2008; Deswandi, 2012). This provides a strong economic incentive for some islanders to assist the blast fishers instead of enforcing the local rule. In addition, the benefit-sharing was perceived to be a type of compensation mechanism for the environmental damage caused to the marine ecosystems in Langkai Island Waters.

The situation with poison fishing is different and at the time of this study there were no active poison fishers on Langkai Island. According to the informants, the prohibition of poison fishing was enforced much stricter locally than the prohibition of blast fishing. While the (1) issues in enforcement, and (2) reciprocity, as described in the previous section, remain the same in the given rationales for engaging in the enforcement of the poison fishing rule, in contrast, the (3) perceived strong negative impact on own fishery yield, and the (4) benefit-sharing differed for the case of poison fishing.

(3) Perceived strong negative impact on own fishery yield: It was argued in all interviews that poison fishing is believed to cause much stronger negative environmental impacts than blast fishing. Poison fishers specifically target coral reef fish. Anecdotal evidence suggests, so it was argued in the interviews, that the poison, if distributed by the local currents, may “turn a vast marine area in a dead zone.” This includes the destruction of large coral reef areas, and of the majority of marine life that happens to be in the area during the time of fishing operation. Based on the perception of the interviewees, poison fishing causes a much stronger impact on the environment and on their own fishing yield5.

(4) Lack of benefit-sharing: Unlike the blast fishers, who provide an economic incentive in exchange for the environmental damage caused, poison fishers do not share their catch with other fishers. Hence, poison fishing offers no economic incentives for the local community to tolerate it.

The third local rule-in-use relates to the prohibition of spear-gun fishing for Mackerel, one of the marine resource most valuable to the Langkai Island fishing community. This rule appeared to be at least as strictly enforced locally as the prohibition of poison fishing. The reasons behind (1) issues in enforcement, and (2) reciprocity, as already outlined before, also remain to some extent for this rule, but cooperation with state actors was not possible at all. Differences compared to the blast fishing rule again accrue to the (3) perceived strong negative impact on own fishery yield, and the (4) benefit-sharing.

(3) Perceived strong negative impact on own fishery yield: The Mackerel fishery is vital for the local economy on Langkai Island. Hand-line and spear-gun are the two fishing gears most adequate to target Mackerel. According to the informants, the agreement to prohibit the use of spear-guns for Mackerel fishing has two central reasons. First, as previously noted, the price for Mackerel caught by hand-line ranged between 50 and 70,000 IDR6 per kilo at the time of this research. The kilo price for Mackerel caught by spear-gun was with 40–45,000 IDR much lower. The lower price results from the fact that the fish caught by spear-gun displays strong visible marks (i.e., the entry and exit injuries of the spear). To achieve the highest possible price for the amount of fish in the area, spear-guns are not used by the Langkai Island community, but only by outsiders. The spear-gun, however, is more effective than using hand-lines, and more fish can be caught in less time. If fishers from other areas use spear-guns, they have an advantage over the Langkai Island fishers and can catch a larger share of the total fish in the area, but the overall yield will only be sold at a lower overall price. This would decrease the overall revenue that could be generated from the fish in the area. The second reason for the agreement is that the local Mackerel fishers perceived that, if Mackerel is caught by a spear-gun, the remaining fish will be scared away due to the fast movement of the spear and the blood spilled into the water. It was argued that, if only hand-lines are used to catch Mackerel, the “fellow fish” will not notice that “somebody” is missing and stay in the area while the use of spear-guns “scares them” away immediately. While fishers would prefer an overall legal prohibition of the use of spear-guns for Mackerel fishing in the entire archipelago, it was argued that the Langkai Island community can only influence what happens in the Langkai Island Waters. Both objectives of the rule thus relate to achieving the highest economic return from the overall abundance of the fish in the area.

(4) Lack of benefit-sharing: The use of spear-guns for fishing Mackerel by outside fishers offers no economic incentives for the local community to tolerate it.

In addition to the rules pertaining to the Langkai Island Waters, a further local informal agreement is found in the area. A Fish Aggregation Device (FAD, locally called rumpon) is a tool to attract fish and keep them nearby. It is an effective tool to concentrate fish in a certain area, which then can be easily harvested. Langkai Island fishers installed FAD westwards off the island, already outside of the area that is perceived to be the Langkai Island Waters. The general understanding among the fishers, not only in Langkai Island but also in other areas of the Spermonde Archipelago (cf. Chozin, 2008), is that who owns the FAD, and maintains it, also privately owns the fish that it aggregates, and that fishing around the FAD is prohibited, or requires the permission of the owner. The informal agreements regarding the FADs thus can be considered a private CPRR in which individuals own a set of marine resources in a defined marine area. For harvesting the fish around the FAD, some owners on Langkai Island collaborate with purse-seine fishers from other areas. The general agreement for the FAD is that if there is enough fish in the area, the purse-seine fishers will inform the owner that they now start to harvest. When harvesting a FAD, the catch will be shared and the total amount of harvested fish divided into four parts, of which one part goes to the FAD owner, whilst the other three parts go to the boat that harvests the fish7. If the FAD owner himself harvests the FAD, of course, he keeps the fish to himself. Since the rules associated with the FAD are no CBM rules, but the rules relate to a private CPRR, different issues arise compared to the CBM rules. The clearly economical nature underlying the motivation of the owner to engage in enforcement is obvious, and all owners reported that they try to enforce the rules as strictly as possible.

(1) Issues in enforcement: A central issue for enforcement relates to the fact that the rules for the FAD are based on a private CPRR instead of a CBM. This means that the owner is the main person responsible for monitoring the rule, not the whole community. While the motivation of the owner to engage in enforcement is obviously high, monitoring a FAD (or several FAD) that is not in direct vicinity of the island is highly difficult for a single person (in some instances they are assisted by other family members). In addition, similar to the spear-gun rule, the lack of legal recognition of this private CPRR complicates the enforcement. In case the rules are broken by “illegal” fishing around the FAD, the owner will claim a large compensation fee from the rule-breaker, which already happened in the past, as reported in several interviews. In both interviews with islanders and district government officials, it was stated that the arrangement is also agreed upon with district government officials, who may voluntarily support the owners of FAD in settling their claim, but without legal recognition of the arrangement. Particularly the lack of legal recognition of the individual ownership of the FAD owners thus presents a drawback for the effective settlement of potential compensation claims by the FAD owner for rule-breaking.

(2) Reciprocity: Whilst the incentive is high to “steal” fish from FAD owners, especially reciprocity-related social and economic sanctions prevent this from happening. The vast majority of the Langkai Island community members stated that they would not steal from the FAD as the fish belongs to the owner, and, if they were caught, they would “feel ashamed” and had to pay a high compensation fee. Outside fishers also reported that they feared hostility during Sawakung if they broke the rule, which would complicate their visits to the fishing grounds close Langkai Island. This shows that for the rules related to the FAD, the issues surrounding reciprocity support the compliance with the FAD rules due to the fear of social and economic sanction.

(3) Perceived strong negative impact on own fishery yield: As a matter of course, breaking the rules related to the FAD by non-owners was perceived to seriously harm the owners' income.

(4) Benefit-sharing: When “stealing” from the FAD, there is no benefit-sharing of the rule breaker that could relax the engagement of the FAD owner in enforcement.

Effective means to address the unregulated and uncontrolled use of marine ecosystems and their associated natural resources are urgently needed (The World Bank, 2006; Young et al., 2007). While local approaches appear to be a promising means to achieve more successful natural resource management (Ruddle, 1999; Armitage, 2005; Ferse et al., 2010, 2014; Cinner et al., 2012), CBM harbors a series of hazards (Berkes, 2004; Cudney-Bueno and Basurto, 2009; Cinner et al., 2012). A better understanding of these hazards is needed to contribute to institute more successful CBM.

In line with other observations from Indonesia and elsewhere, this study supports previous research that challenges the portrayal of CBM as isolated endeavors in which communities are buffered from the “outside” world (Agrawal and Gibson, 1999; Berkes, 2004, 2007b; Cudney-Bueno and Basurto, 2009; Seixas and Berkes, 2010; Adhuri, 2013; Pauwelussen, 2016). The results of this study show that particular problems emerge from “trans-local” variables, which hamper the effectiveness of the self-organized local endeavors. Moreover, the study illuminates that divergences in the economic rationales of the community members are an important factor which affect their motivations to engage (or not) in local approaches to managing marine resources.

The marine resource use patterns in the sea area around Langkai Island are impacted by a convoluted rule system generated by different types of CPRR. While the Indonesian state CPRR rules to ban highly destructive fishing are indeed found to have a perceived impact on the marine resource use in the waters surrounding Langkai Island, this study confirms wider observations that the enforcement of environmental law is fraught with difficulties (cf. Idrus, 2009; Glaser et al., 2010; Wever et al., 2012). Especially corruption, the long distance from the Water Police base to the case study area, and insufficient funds for adequate patrolling are central factors resulting in enforcement shortcomings of the rules produced by the state CPRR. This represents an eminent threat to the marine ecosystems and the abundance of fishery resources (Patlis et al., 2001; Dirhamsyah, 2006; Jones et al., 2011). Partly in response to the shortcomings of the state CPRR, local rules-in-use have emerged in the case study area despite the lack of legal authority to do so. Area-specific stewardship for a marine territory surrounding Langkai Island (CBM) and individual ownership (private CPRR) was informally institutionalized and locally devised rules based on informal agreements were instituted for a specified portion of the sea area surrounding Langkai Island. However, while the islanders' authority to devise rules for the Langkai Island Waters may be to some extent informally acknowledged by outside fishers, the self-organized local initiative lacks the official authority to formally develop and especially to locally enforce rules. As a result, close coordination between the local community and state actors is needed which represents a strong challenge, especially in context of a remote small island community.

In consequence, the findings of this research further support the classical argument made for instance by Ostrom (1990, 2005) that, in order to contribute to increase effectiveness of self-organized local endeavors, and to reduce the challenge of coordination with higher level state actors for instituting and enforcing rules, a clear allocation of rights to the local level to devise rules, and the endowment of the community with appropriate legal means to enforce the rules, is essential. Moreover, Seixas and Berkes (2010), who explored success factors in multiple case studies on community-based enterprises in natural resource management, found in this regard that networks and partnerships which extend beyond the boundaries of a community are an important means to improve coordination in a nested rule system. Given the findings of this research together with the results of other studies from Indonesia and elsewhere (cf. Adhuri and Visser, 2006; Cudney-Bueno and Basurto, 2009; Gasalla, 2011), both aspects appear to be highly salient to effect more successful self-organized local natural resource management.

The active engagement of the local population in the implementation of local regulations is a necessary precondition for a successful CBM initiative. In this respect, the analysis of local resource users' perceptions, which are socially constructed and informed by both personal experience and the information available (Clayton and Myers, 2009), are crucial to understand what motivates (or not) individuals to engage in CBM of marine resources (McClanahan et al., 2005; Walker-Springett et al., 2016). This study reveals how the divergences in the perceptions of the members in a community affect their motivation to engage in the CBM endeavor. Moreover, the findings particularly illustrate the challenges of dealing with factors that lie outside the influence sphere of a community.

The vast majority of Langkai Island fishers cooperate and comply with “their” rules as produced by the CBM and the private CPRR. The fishers of the Langkai Island community neither use poison fishing, nor blast fishing, nor spear-guns in the Langkai Island Waters. Moreover, poaching at the FAD is perceived to be highly risky as it is difficult to conceal it in such a small island community. Thus, in fact, the rationales underlying the motivation of the islander to engage in rule enforcement, as reported in this study, mainly relate to rule-breaking of outsiders and, therefore, have to be understood in the context of defending the local resources against undesirable fishing behavior by non-community members. While research has shown that social sanctions can effectively induce intra-community cooperation for collective action and compliance among community members (Ostrom, 1990, 1999, 2005), this study shows that this does not necessarily apply for non-community members. Rather, inter-community reciprocity concerns may arise when engaging in enforcing the local rules against outsiders, which can hamper the effective enforcement of the local rules. As a result, the reliance on social sanctions may be a pitfall in effecting rule compliance when the aim is to defend local resources against outsiders (see also, for instance, Cudney-Bueno and Basurto, 2009).

The findings show that there are differences in the strictness of the enforcement of the local rules. These differences mainly stem from economic rationales of the community members. In fact, the motivation for the engagement in the enforcement of the local rules by the Langkai islanders are strongly based on short-term economic considerations, i.e., on a “give-and-take” basis in the local context. If the fishing activities of rule-breakers are not perceived to strongly harm the fishing yield of individuals, and/or if benefits of the generated yields are shared with the Langkai Island community as a compensation mechanism for the environmental harm caused, the motivation of the affected community members to engage in rule enforcement seems to cease. As a result, the prohibition of the fishing activities, which are perceived to cause a stronger impact on the short-term economic return of local fishers without compensation mechanisms are much stronger enforced. Ostrom (1990) raised concerns that the compliance of community members with self-organized rules that regulate the use of natural resources may be undermined, if resource users value the expected future opportunity of resource availability and possible future gains less than the value they can generate now or in the near future. While this may hold true for intra-community compliance to self-organized rules, the findings of this study indicate that the perceived danger of short-term economic losses of the local community members may be a particular success factor of a CBM initiative, if the aim of a CBM initiative involves to defend local resources against undesired use forms by outsiders.

Despite the presence of diverse rules-in-use for organizing the marine resource use in the case study area, conservation thinking, i.e., the aim to preserve an intact local marine environment in the long run, played almost no role in the rationales given in all interviews. Rather, it appears that the locally devised rules in that area intend to ensure that the local community gets an adequate share of the diminishing local marine resources, which are exploited by a growing number of fishers from elsewhere. This also leads to concerns that the environmental conservation effects of the locally devised rules in the area may be limited and should be considered incidental.

Especially in tropical nations with weak state institutions such as Indonesia, CBM has been widely advocated for its potential to achieve more effective natural resource management. However, detailed case study analyses of the challenges for implementing CBM in a particular sea territory remain very rare, but are particularly needed to understand the potential pitfalls for local approaches to marine resource management. This article provided a detailed analysis of a case study in Indonesia to contribute to fill this gap and help to institute more effective community-based marine resource management.

The results of this study particularly emphasize the context dependence of the success of a CBM initiative for marine resources because a certain CBM initiative, even in what seems to be a small community in a remote island setting, is characterized by internal divergences, and by “trans-local” variables which create complex interdependencies. Especially divergences in the economic rationales of the community members are important factors which affect their motivation to engage (or not) in both the CBM and the private CPRR. While especially short-term economic considerations appear to be a particular success factor in this study, such rationales underlying the motivation of community members to engage in CBM raise concerns about the sustainability orientation of the local measures.

While the scope of this research with its narrow focus on a small sea territory appears limited, the study brings a suite of aspects to attention that are often overlooked, but are highly salient to understand the factors underlying successful CBM. Moreover, the situation in this island mirrors the situation of communities in other areas in Indonesia, and also in other countries with weak state institutions. Further research is especially needed on how to address the pitfalls of CBM that are induced by factors that lie beyond the reach of local communities, and on mechanisms for improved coordination between the different types of CPRR. This is particularly urgent for remote places such as a small island, where large portions of the population heavily depend on increasingly degraded resource systems to secure their livelihoods. Moreover, perception studies represent important means to assist marine planners, policy makers and natural resource managers to better understand the reality of CBM initiatives.

The author is responsible for data collection, analyses and writing of the manuscript.

I greatly appreciate the financial support from the SPICE III Project (grant number 03F0643A) funded by the German Ministry for Research and Education (BMBF) and the Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Ecology (ZMT) in Bremen, Germany. Moreover, I acknowledge financial support from the Alexander-von-Humboldt (AvH) professorship for Environmental Economics of the University of Osnabrück (UOS). I also acknowledge support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and Open Access Publishing Fund of Osnabrück University.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Guest Associate Editor, AB, declares that, despite having recently published with the author, PG, the review process was handled objectively and no conflict of interest exists.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmars.2016.00120

1. ^Note that almost all of the positions in the administrative structure at the local level are voluntary and unsalaried, and the vast majority of the island officials relied more or less directly on fishery related livelihood activities such as fishing, trading, fishing boat construction etc. for their income.

2. ^At the time of this research, 1 Euro was equivalent to about 12,500 IDR (Indonesian Rupiah).

3. ^Note that the Fish Aggregation Devices (see below) are located outside the Langkai Island Waters and are thus not included in these interviews.

4. ^It could not be revealed in further communication on the matter with marine biologists whether this perception holds true, or whether this is a misperception.

5. ^It could not be revealed in further communication on the matter with marine biologists whether this strong impact is true, or whether this is a misperception.

6. ^At the time of this research, 1 Euro was equivalent to about 12,500 IDR (Indonesian currency).

7. ^Note that there seem to be different agreements related to the FAD in the wider Spermonde Archipelago area. Chozin (2008) describes the FAD as a tool that is harvested by blast fishers using bombs. According to his detailed ethnographic description of another area in the Spermonde Archipelago, the sharing ratio is 2:3 in which the owner of the FAD gets two portions of the fish and the harvester gets three. As for the Langkai Island FAD, the FAD are harvested by Purse-Seine fishers, which also might explain the different share-ratio between the harvester and the FAD owner.

Adhuri, D. S. (2013). Selling the Sea, Fishing for Power: A Study of Conflict over Marine Tenure in Kei Islands, Eastern Indonesia. Canberra, ACT: ANU E-Press.

Adhuri, D. S., and Visser, L. E. (2006). “Fishing in, fishing out: transboundary issues and the territorialization of blue space” in Proceedings of the International Workshop on “Transboundary Environmental Issues in Southeast Asia” (Taipeh: Center for Asia-Pacific Area Studies (CAPAS)), 112–145.

Agardy, T., Alder, J., Dayton, P., Curran, S., Kitchingman, A., Wilson, M., et al. (2005). “Coastal systems,” in Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Current State and Trends, Vol. 1, ed W. V. Reid (Washington, DC; Covelo; London: Island Press), 515–549.

Agrawal, A., and Gibson, C. C. (1999). Enchantment and disenchantment: the role of community in natural resource conservation. World Dev. 27, 629–649. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00161-2

Alcala, A. C. (1998). Community-based coastal resource management in the Philippines: a case study. Ocean Coast. Manag. 38, 179–186. doi: 10.1016/S0964-5691(97)00072-0

Armitage, D. (2005). Adaptive capacity and community-based natural resource management. Environ. Manage. 35, 703–715. doi: 10.1007/s00267-004-0076-z

Berkes, F. (2004). Rethinking community-based conservation. Conserv. Biol. 18, 621–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00077.x

Berkes, F. (2007a). “Adaptive co-management and complexity: exploring the many faces of co-management,” in Adaptive Co-Management: Collaboration, Learning, and Multi-level Governance, eds D. Armitage, F. Berkes, and N. Doubleday (Vancouver: UBC Press), 19–37.

Berkes, F. (2007b). Community-based conservation in a globalized world. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15188–15193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702098104

Berkes, F. (2010). Devolution of environment and resources governance: trends and future. Environ. Conserv. 37, 489–500. doi: 10.1017/S037689291000072X

Bernard, R. H. (2006). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 4th Edn. Oxford: AltaMira Press.

Borrini-Feyerabend, G., Pimbert, M., Farvar, M. T., Kothari, A., and Renard, Y. (2004). Sharing Power: Learning by Doing in Co-Management of Natural Resources throughout the World. Cenesta; Teheran: IIED and IUCN/CEESP/CMWG.

Bromley, D. W., and Cernea, M. M. (1989). The Management of Common Property Natural Resources: Some Conceptual and Operational Fallacies. Worldbank Discussion Paper 57. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Burke, L., Reytar, K., Spalding, M., and Perry, A. (2011). Reefs at Risk Revisited. Washington, DC: World Resource Institute.

Cheung, W. W. L., Lam, V. W. Y., Sarmiento, J. L., Kearney, K., Watson, R., Zeller, D., et al. (2010). Large-scale redistribution of maximum fisheries catch potential in the global ocean under climate change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 16, 24–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01995.x

Chozin, M. (2008). Not Legal but Common: Life of Blast Fishermen in the Spermonde Archipelago, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. MSc thesis.

Christie, P., and White, A. T. (2007). Best practices for improved governance of coral reef marine protected areas. Coral Reefs 26, 1047–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00338-007-0235-9

Cinner, J. E., Basurto, X., Fidelman, P., Kuange, J., Lahari, R., and Mukminin, A. (2012). Institutional designs of customary fisheries management arrangements in Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and Mexico. Mar. Policy 36, 278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2011.06.005

Clayton, S., and Myers, G. (2009). Conservation Psychology: Understanding and Promoting Human Care for Nature. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Cribb, R., and Ford, M. (2009). “Indonesia as an archipelago: managing islands, managing the sea,” in Indonesia beyond the Water's Edge: Managing an Archipelagic State, eds R. Cribb and M. Ford (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS)), 1–27.

Cudney-Bueno, R., and Basurto, X. (2009). Lack of cross-scale linkages reduces robustness of community-based fisheries management. PLoS ONE 4:e6253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006253

Dearden, P., Bennett, M., and Johnston, J. (2005). Trends in global protected area governance, 1992-2002. Environ. Manage. 36, 89–100. doi: 10.1007/s00267-004-0131-9

Deswandi, R. (2012). Understanding Institutional Dynamics: The Emergence, Persistence, and Change of Institutions in Fisheries in Spermonde Archipelago, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Ph.D., thesis.

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (2013). Sicherung Guter Wissenschaftlicher Praxis: Empfehlungen der Kommission “Selbstkontrolle in der Wissenschaft.” Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA.

Dirhamsyah, D. (2006). Indonesian legislative framework for coastal resources management: a critical review and recommendation. Ocean Coast. Manag. 49, 68–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2005.09.001

Edinger, E. N., Jompa, J., Limmon, G. V., Widjatmoko, W., and Risk, M. J. (1998). Reef degradation and coral biodiversity in Indonesia: effects of land-based pollution, destructive fishing practices and changes over time. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 36, 617–630. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(98)00047-2

Ferrol-Schulte, D., Gorris, P., Baitoningsih, W., Adhuri, D. S., and Ferse, S. C. A. (2015). Coastal livelihood vulnerability to marine resource degradation: a review of the Indonesian national coastal and marine policy framework. Mar. Policy 52, 163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.09.026

Ferrol-Schulte, D., Wolff, M., Ferse, S. C. A., and Glaser, M. (2013). Sustainable Livelihoods Approach in tropical coastal and marine social–ecological systems: a review. Mar. Policy 42, 253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2013.03.007

Ferse, S. C. A., Glaser, M., Neil, M., and Schwerdtner Máñez, K. (2014). To cope or to sustain? Eroding long-term sustainability in an Indonesian coral reef fishery. Reg. Environ. Change 14, 2053–2065. doi: 10.1007/s10113-012-0342-1

Ferse, S. C. A., Knittweis, L., Krause, G., Maddusila, A., and Glaser, M. (2012). Livelihoods of ornamental coral fishermen in south sulawesi/indonesia: implications for management. Coast. Manage. 40, 525–555. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2012.694801

Ferse, S. C. A., Máñez Costa, M., Schwerdtner Máñez, K., Adhuri, D. S., and Glaser, M. (2010). Allies, not aliens: increasing the role of local communities in marine protected area implementation. Environ. Conserv. 37, 23–34. doi: 10.1017/S0376892910000172

Gasalla, M. A. (2011). “Do all answers lie within (the community)? Fishing rights and marine conservation,” in World Small-Scale Fisheries: Contemporary Visions, ed R. Chuenpagdee (Delft: Eburon Acdemic Publisher), 185–203.

Glaeser, B., and Glaser, M. (2010). Global change and coastal threats: the Indonesian case. An attempt in multi-level social-ecological research. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 17, 135–147.

Glaser, M., Baitoningsih, W., Ferse, S. C. A., Neil, M., and Deswandi, R. (2010). Whose sustainability? Top–down participation and emergent rules in marine protected area management in Indonesia. Mar. Policy 34, 1215–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2010.04.006

Glaser, M., Breckwoldt, A., Deswandi, R., Radjawali, I., Baitoningsih, W., and Ferse, S. C. A. (2015). Of exploited reefs and fishers: a holistic view on participatory coastal and marine management in an Indonesian archipelago. Ocean Coast. Manage. 116, 193–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.07.022

Gorris, P. (2015). Entangled? Linking Governance Systems for Regional-Scale Coral Reef Management: Analysis of Case Studies in Brazil and Indonesia. Bremen: Jacobs University.

Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science 162, 1243–1248. doi: 10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

Hauck, J., Stein, C., Schiffer, E., and Vandewalle, M. (2015). Seeing the forest and the trees: facilitating participatory network planning in environmental governance. Glob. Environ. Change 35, 400–410. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.09.022

Hidayat, A. (2005). Institutional Analysis of Coral Reef Management. A Case Study of Gili Indah Village, West Lombok, Indonesia. Aachen: Shaker Verlag.

Idrus, M. R. (2009). Hard habits to break, Investigating Coastal Resource Utilisations and Management Systems in Sulawesi, Indonesia. Canterbury: University of Canterbury.

Jones, P. J. S. (2014). Governing Marine Protected Areas: Resilience through Diversity. Oxon; New York, NY.

Jones, P. J. S., Qiu, W., and De Santo, E. M. (2011). Governing Marine Protected Areas - Getting the Balance Right, Technical Report. Nairobi: Technical Report, United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Nairobi.

Kalikoski, D. C. (2007). “Marine protected areas and social justice: insights from the common property theory,” in Aquatic Protected Areas as Fisheries Management Tools, Protected Areas of Brazil Series, eds A. P. Prates and D. Blanc (Brasilia: Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA)), 65–75.

McClanahan, T. R., Maina, J., and Davies, J. (2005). Perceptions of resource users and managers toweards fisheries management options in Kenyan coral reefs. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 12, 105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2400.2004.00431.x

Miñarro, S., Navarrete Forero, G., Reuter, H., and van Putten, I. E. (2016). The role of patron-client relations on the fishing behaviour of artisanal fishermen in the Spermonde Archipelago (Indonesia). Mar. Policy 69, 73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.04.006

Novaczek, I., Harkes, I. H. T., Sopacua, J., and Tatuhey, M. D. D. (2001). An Institutional Analysis of Sasi Laut in Maluku, Indonesia. ICLARAM Technical Report 59, ICLARAM - The World Fish Center, Penang, 343.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge.

Ostrom, E. (1999). Coping with tradgedies of the commons. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2, 493–535. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.493

Patlis, J. M., Dahuri, R., Knight, M., and Tulungen, J. (2001). Integrated coastal management in a decentralized Indonesia: how it can work. Integr. Coast. Manage. 4, 24–39.

Pauwelussen, A. (2016). Community as network: exploring a relational approach to social resilience in coastal Indonesia. Maritime Stud. 15, 2. doi: 10.1186/s40152-016-0041-5

Pauwelussen, A. P. (2015). The moves of a Bajau middlewoman: understanding the disparity between trade networks and marine conservation. Anthropol. Forum J. Soc. Anthropol. Comp. Sociol. 25, 329–349. doi: 10.1080/00664677.2015.1054343

Pet-Soede, C., Cesar, H. S. J., and Pet, J. S. (1999). An economic analysis of blast fishing on Indonesian coral reefs. Environ. Conserv. 26, 83–93. doi: 10.1017/S0376892999000132

Pet-Soede, C., Van Densen, W. L. T., Hiddink, J. G., Kuyl, S., and Machiels, M. A. M. (2001). Can fishermen allocate their fishing effort in space and time on the basis of their catch rates? An example from Spermonde Archipelago, SW Sulawesi, Indonesia. Fish. Manage. Ecol. 8, 15–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2400.2001.00215.x

Pet-soede, L., and Erdmann, M. (1998). An overview and comparison of destructive fishing practices in Indonesia. SPC Live Reef Fish Inf. Bull. 4, 28–36.

Plass-Johnson, J. G., Ferse, S. C. A., Jompa, J., Wild, C., and Teichberg, M. (2015a). Fish herbivory as key ecological function in a heavily degraded coral reef system. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60, 1382–1391. doi: 10.1002/lno.10105

Plass-Johnson, J. G., Schwieder, H., Heiden, J., Weiand, L., Wild, C., Jompa, J., et al. (2015b). A recent outbreak of crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) in the Spermonde Archipelago, Indonesia. Reg. Environ. Change 15, 1157–1162. doi: 10.1007/s10113-015-0821-2

Plass-Johnson, J. G., Taylor, M. H., Husain, A. A. A., Teichberg, M. C., and Ferse, S. C. A. (2016). Non-random variability in functional composition of coral reef fish communities along an environmental gradient. PLoS ONE 11:e0154014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154014