95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 27 November 2014

Sec. Marine Biogeochemistry

Volume 1 - 2014 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2014.00064

Sulfide intrusion in seagrasses, as assessed by stable sulfur isotope signals, is widespread in all climate zones, where seagrasses are growing. Seagrasses can incorporate substantial amounts of 34S-depleted sulfide into their tissues with up to 87% of the total sulfur in leaves derived from sedimentary sulfide. Correlations between δ34S in leaves, rhizomes, and roots show that sedimentary sulfide is entering through the roots, either in the form of sulfide or sulfate, and translocated to the rhizomes and the leaves. The total sulfur content of the seagrasses increases as the proportion of sedimentary sulfide in the plant increases, and accumulation of elemental sulfur (S0) inside the plant with δ34S values similar to the sedimentary sulfide suggests that S0 is an important reoxidation product of the sedimentary sulfide. The accumulation of S0 can, however, not account for the increase in sulfur in the tissue, and other sulfur containing compounds such as thiols, organic sulfur, and sulfate contribute to the accumulated sulfur pool. Experimental studies with seagrasses exposed to environmental and biological stressors show decreasing δ34S in the tissues along with reduction in growth parameters, suggesting that sulfide intrusion can affect seagrass performance.

With the growing access to mass spectrometers, stable isotopes have become an important tool to explore complex questions in biological research (Fry, 2006). In the marine environment, stable isotopes have been successfully used in food web studies and are now applied in seagrass research to study a wide range of questions extending from uptake and incorporation of carbon during photosynthesis (Raven et al., 1995), carbon and nitrogen translocation in seagrasses (Marba et al., 2002) and carbon burial in sediments (Kennedy et al., 2010). Stable sulfur isotopes are used in food web studies together with 13C and 15N (Kharlamenko et al., 2001; Mittermayr et al., 2014), and in the studies of early evolution of life on earth (Canfield et al., 2000), and even earlier used to explore the uptake of sulfate and sulfide in halophytes and seagrasses (Fry et al., 1982). Sulfide is toxic to living cells, as it reacts strongly with iron-containing enzymes and thereby inhibits enzymatic processes in the cells (Raven and Scrimgeour, 1997). Several studies of seagrasses have suggested sulfide toxicity as a contributing factor in seagrass decline, where high sulfide concentrations induce seagrass mortality, e.g., in die-back events in Florida (Carlson and Forrest, 1982; Borum et al., 2005), during organic enrichment of sediments near fish farms (Frederiksen et al., 2007), upon invasion of seagrass meadows with Caulerpa sp. (Garcias-Bonet et al., 2008) and during hypoxic events (Mascaro et al., 2009). Quantification of sulfide exposure in seagrasses by the use of stable sulfur isotopes has the potential as a tool to examine seagrass stress factors (Kilminster et al., 2014).

Sulfate reduction is an important process for anaerobic decomposition of organic matter in marine sediments, where it can account for more than 50% of the organic matter oxidation (Jørgensen, 1982). Sulfate reduction is a key process in the anoxic sediments due to high pools of sulfate in seawater (in mM concentrations) compared to other electron acceptors present in μM (Canfield et al., 1993). Sulfide is produced during bacterial sulfate reduction and may accumulate in the sediment pore waters or precipitate with iron either as FeS or as pyrite (FeS2) commonly referred to as the AVS (acid volatile sulfide) and the CRS (chromium reducible sulfur) pool, respectively, based on the method used for extraction of the precipitated pools (Fossing and Jørgensen, 1989). Sulfate is fractionated during sulfate reduction and sedimentary sulfide has δ34S ranging between −15 to −25‰ (Canfield, 2001; Böttcher et al., 2004), compared to about +21‰ for sulfate in oceanic seawater (Rees et al., 1978). This difference is sufficient to distinguish the sources of sulfur in seagrass tissues by analysis of the stable sulfur isotopic composition (Fry et al., 1982; Frederiksen et al., 2006).

In contrast to the bacterial fractionation, sulfur isotopes remain unchanged in plant uptake and assimilation, and the isotopic composition of the tissues reflects the source of sulfur (Winner et al., 1981; Monaghan et al., 1999). Fry et al. (1982) suggested three potential sources of sulfur available for uptake in seagrasses: seawater sulfate, pore water sulfate, and sediment derived sulfide. Plants may acquire sulfur by active uptake of sulfate directly from the water column and pore waters by the leaves and roots, respectively, possibly mediated by a carrier as found in terrestrial plants (Kylin, 1960; Rennenberg, 1984), or by passive intrusion of gaseous sulfide into the below-ground tissues (Pedersen et al., 2004). Pore water sulfate may differ from the seawater sulfate signal, as it can be either heavier due to discrimination by sulfate-reducing bacteria against the lighter isotopes leaving a heavier pool of residual pore water sulfate, or lighter, if the light pore water sulfide is reoxidized to sulfate (Canfield, 2001). The last process may be important in seagrass sediments where oxygen release from the roots is considered an important mechanism for reoxidation of sulfide preventing the gaseous sulfide from entering into the plants (Pedersen et al., 2004; Frederiksen and Glud, 2006; Lamers et al., 2013).

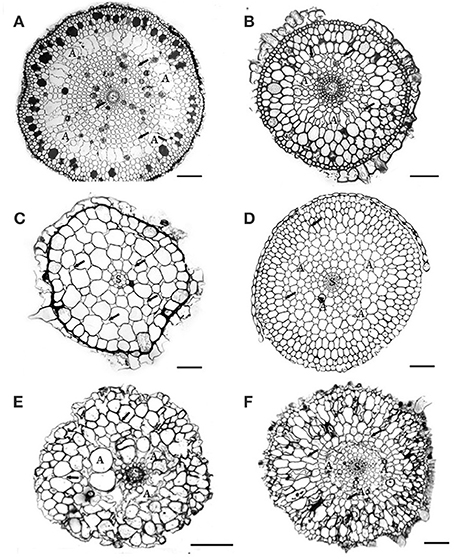

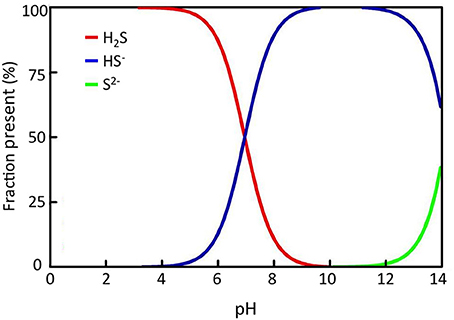

Seagrasses are growing in coastal zones world-wide from the tropics extending into the sub-arctic and about 72 seagrass species have been identified to date (Orth et al., 2006; Short et al., 2011). Seagrasses grow where light, substrate conditions and physical exposure allow and can be found from <1 m to 40–50 m depth. They vary in size from small (<5 cm leaf length) to large species (>1–2 m leaf length), but they are all characterized by being anchored into the sediments by roots and horizontal rhizomes. Some of the larger species also have vertical rhizomes extending 10–40 cm into the water column. Seagrasses are adapted to growth in anoxic sediments by their extensive aerenchyma tissue throughout the plants (Figure 1), which allow transportation of oxygen from leaves to roots and sustain oxic conditions around roots tips (Pedersen et al., 2004; Frederiksen and Glud, 2006). During night, however, where there is no photosynthesis, oxygen may be depleted inside the plant due to respiration, and if the oxygen supply from the water column is not sufficient, parts of the plant may turn anoxic (Pedersen et al., 2004; Frederiksen and Glud, 2006; Raun and Borum, 2013). If sulfide is present in the sediments, gaseous sulfide can enter through the root tips and diffuse into the plant tissues. Due to the high pH of pore waters (~ 6–8) in seagrass sediments (Brodersen et al., 2014), only a fraction of the pore water sulfide is present in gaseous form (H2S, Figure 2), which minimizes the risk of sulfide intrusion into the plants as only gaseous sulfide (H2S) is able to penetrate the bi-layer membranes and intrude into tissues (Raven and Scrimgeour, 1997). High concentrations of gaseous sulfide have, however, been measured inside seagrasses in the field with concentrations up to 325 μM for Zostera marina in a natural stand (Pedersen et al., 2004) and >750 μM for Thalasia testudinum in a die-back area (Borum et al., 2005). For both species the intrusion occurred during night, where oxygen was depleted in the lacunae due to respiration and due to low oxygen concentrations in the overlying water. When photosynthesis was reestablished at dawn, gaseous sulfide (H2S) was reoxidized by photosynthetically derived oxygen and disappeared from the internal structures (Pedersen et al., 2004; Borum et al., 2005). The reoxidation rate was slow, in the order of 20–30 min, suggesting a chemical rather than a biological mediated oxidation process (Pedersen et al., 2004). Similar scenarios can be expected for other seagrasses as they have the same basic structure and grow in anoxic sediments. Nevertheless, due to the large variation in size and growth rates of seagrass species as well as substrate conditions and environmental parameters, large spatial, temporal, and species variation in sulfide intrusion can be expected.

Figure 1. Cross-sections of 6 Australian seagrasses. (modified from Cambridge et al., 2012) (A) Cymodocea sp.: The epidermis is distinct. Hypodermis with thickened walled cells. Outer cortex with 3–4 layers of large cells containing tannin substances. Middle cortex with many regular large lacunae (A). Small intercellular spaces (arrows) occur in the inner cortical tissue. The stele is distinct. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Syringodium isoetifolium: Epidermal cells large, with tannin substances. Hypodermal cells small with thickened walls. Outer cortex with 3–4 layers of large cells, middle cortex with many developing regular large lacunae (A). Small air spaces (arrows) occur in both middle and inner cortical tissue. The stele (S) is distinct. Scale bar = 100 μm. (C) Halodule uninervis: Epidermal cells large. Small hypodermal cells with thicken walled. Cortex does not have distinct regions and consists of 5–6 layers of cortical cells with the outer ones being the largest. Distinct intercellular spaces occur throughout the cortical tissues. The central stele (s) is small. Scale bar = 100 μm. (D) Halophila ovalis: This section was taken from the basal portion of the root, where root hairs were absent. Epidermal cells small, hypodermal cells with thickened walls. Distinct lacunae (A) occur in the mid cortex region. The intercellular spaces (arrows) occur in both middle and inner cortical tissues. The stele (S) is distinct. Scale bar = 150 μm. (E) Posidonia australis: Branched root shown: cortical tissue only has about 8–10 cell layers, without distinct regions. Air lacunae (A) are developing. Few intercellular air spaces (arrows) are present. Scale bar = 100 μm. In developing “white” roots, epidermal cells are distinct, 1–2 layers of hypodermis and many distinct air lacunae in the middle cortex. Scale bar = 100 μm. (F) Amphibolis Antarctica: Both epidermis and hypodermis are distinct and contain tannin substances. The outer cortex has several layers of compact cells, without intercellular air spaces. The mid cortex has few developing lacunae (A). Few intercellular air spaces (arrows) also occur in the cortical cells. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 2. Sulfide solubility chart showing the relative fraction of each sulfide species at different pH; H2S = hydrogen sulfide, HS− = hydrosulfide, S2− = sulfide di-anion.

Seagrasses are threatened by environmental pressures and show rapid rates of decline (Waycott et al., 2009), and sulfide toxicity is considered one of the contributing factors for the observed declines. Stable sulfur isotopes have been proposed as indicators of sediment-sulfide stress and may be used to monitor environmental pressure in seagrasses (Kilminster et al., 2014). The overall aim of this review is to explore the variation in stable sulfur isotope composition in seagrass tissues and whether the composition can be used as indicator of sulfide intrusion into seagrasses. This is done through a compilation of spatial, temporal, and species variation in stable sulfur isotopic signals in seagrasses combined with an analysis of the contribution of sediment sulfide to sulfur content in seagrasses. Finally a summary of impacts of sulfide intrusion on seagrass performance is provided.

The δ34S values of sulfur sources (seawater and pore water sulfate and sedimentary sulfide) are measured by mass spectrometry. The methods for preparation of samples for δ34S analysis of sulfate and sulfide are different, where sulfate in seawater or pore water is precipitated as BaSO4 after boiling the sample under acidic conditions with BaCl2, whereas extraction of sulfide needs more preparation. Due to low pore water concentrations of dissolved sulfide (typically μM) and rapid oxidation by exposure to air, it is difficult to obtain enough material to analyze δ34S-sulfide in pore waters directly. Instead, sulfide is obtained by distillation of the sediments, where several methods are available. The most common method separates the acid volatile pool (AVS: H2S and FeS) from the chromium reducible pool (CRS: S0 and FeS2) (Fossing and Jørgensen, 1989; Kallmeyer et al., 2004). The pore water sulfide is included in the AVS pool, and this pool is used as a proxy for the δ34S values of pore water sulfide, as FeS is the first product in the early diagenesis of sulfur in marine sediments and no fractionation of sulfide occurs during the transformation from the dissolved to the particulate phase (Fossing and Jørgensen, 1989; Canfield, 2001). During distillation sulfide is precipitated as Ag2S, and the sulfur precipitate is filtered and weighed into tin capsules and vanadium pentoxide added as catalyst. The samples (BaSO4 or Ag2S in tin capsules) are analyzed by EA-CF-IRMS. Barium sulfate and silver sulfide are used as standards, which are supplied from reference laboratories such as The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Vienna. In brief an elemental analyzer (EA) coverts the total sulfur in the sample into SO2 gas. The EA is connected to a continuous-flow isotope-ratio mass-spectrometer (CF-IRMS), which measures the relative difference in stable-sulfur-isotope amount ratio (34S/32S) of the product SO2 gas.

The sulfur isotope composition of a sample is expressed in the standard δ notation (units per mill, ‰) given by

where Rsample = 34S/32S in the sample and Rstandard is the isotopic composition of the standard.

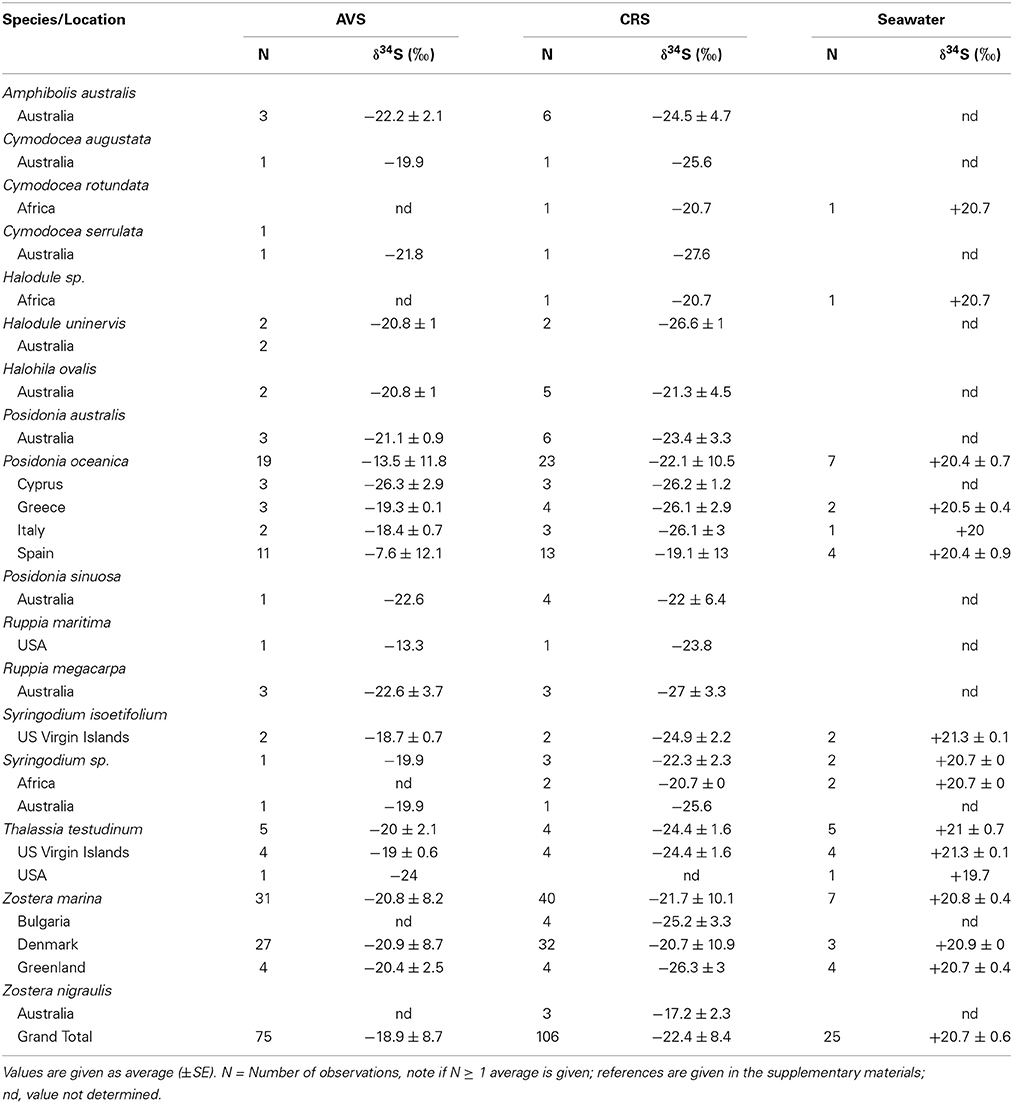

The δ34S values of seawater collected in seagrass meadows (Table 1) are quite consistent with the global oceanic value of +21‰ (Rees et al., 1978; Böttcher et al., 2007) although with a tendency to slightly lower values (global average +20.7‰) probably reflecting some mixing with lighter sulfide as observed for coastal waters (Böttcher et al., 2007). There are only a few reports of the isotopic composition of pore water sulfate in seagrass rhizosphere sediments, showing either slightly lower (+15.9 to +17.4‰, Fry et al., 1982) or slightly higher values (+22.3 ± 2.3‰, Frederiksen et al., 2006) compared to seawater sulfate. Lower values can be due to mixing of the sulfate pool with reoxidized sedimentary sulfide and higher values can be due to increasing values of the pore water sulfate pool as a result of sulfate reduction (Canfield, 2001). δ34S of pore water sulfide in seagrass sediments is only available from one study with values ranging between −24.1 to −20.7‰, which is slightly less negative than the corresponding AVS pool (−26.3 to −23.4‰) in the same sediments (Frederiksen et al., 2007). A compilation of the δ34S of AVS pools for seagrass sediments range between −26.3‰ to −7.6‰ with an average value of −18.9‰(Table 1). Less variation was found for CRS (−26.6‰to −17.2‰) and the average value was lower (−22.4‰, Table 1). The average sediment δ34S in seagrass sediments is less negative compared to non-vegetated sites (~ +25‰, Canfield, 2001). The large variations between sampling stations within the same site (Frederiksen et al., 2007), between locations (e.g., across the Mediterranean in Frederiksen et al., 2007) and between seasons (Frederiksen et al., 2006; Papadimitriou et al., 2006) illustrate the large spatial and temporal variability in sulfur isotopes in seagrass sediments. Such variability is critical and has to be accounted for when quantifying the contribution of sedimentary sulfide to the sulfur content in seagrasses (see below).

Table 1. Sulfur sources (sulfate and sulfide) δ34S from seagrass meadows represented by acid volatile sulfide (AVS), chromium reducible sulfur (CRS), and seawater sulfate.

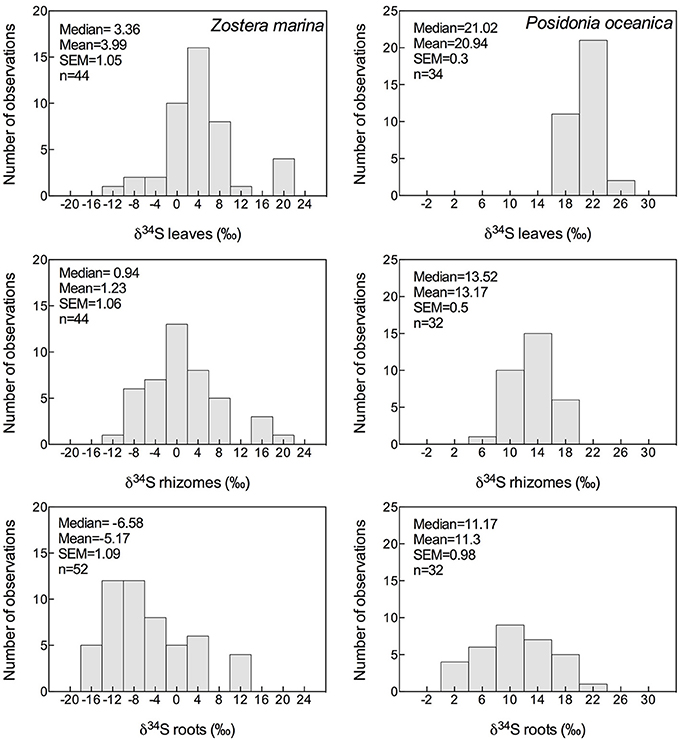

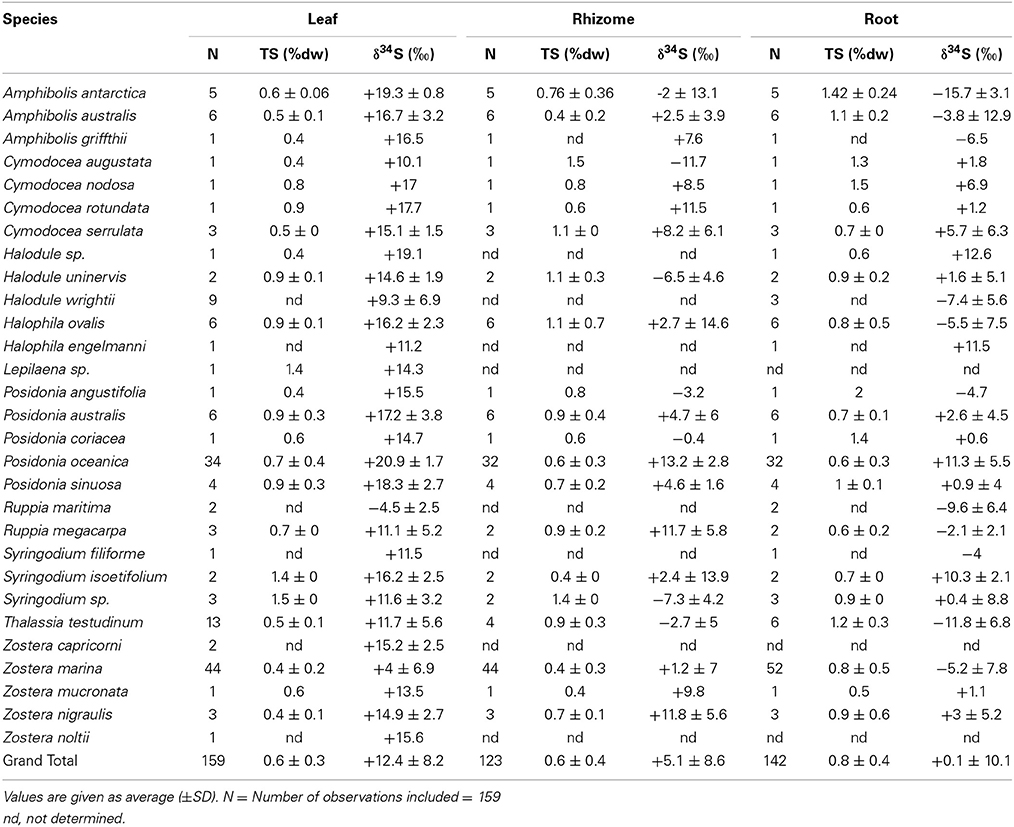

The δ34S composition of seagrasses has been investigated for various reasons (e.g., food-web structure, sulfur sources, and sulfide toxicity) in the past, resulting in a data set covering most seagrass genera, and δ34S values exist for about half of the species (27), representing sub-arctic, temperate, subtropical, and tropical seagrasses with most observations of Posidonia oceanica, Thalassia hemprichii, and Z. marina (Figure 3 and Table 2). The δ34S range from seawater sulfate levels in P. oceanica (+20.9 ± 03‰; Figure 3) and to negative values in Ruppia maritima (−4.5 ± 3.5‰). Most species have leaf values between +10% and +15‰ and the average value in leaves for all species is +12.4 ± 8.2‰. As δ34S of the leaves deviate from seawater sulfate having more negative values, this suggests that seagrasses accumulate sulfur derived from sedimentary sulfide in the leaves.

Figure 3. Histograms showing the mean, median and SEM of δ34S of leaves, rhizomes and roots of Zostera marina (left column) and Posidonia oceanica (right column) of data available in literature; references are given in the supplementary material.

Table 2. δ34S of leaves, rhizomes and roots of several seagrass species, references are reported in the supplementary material.

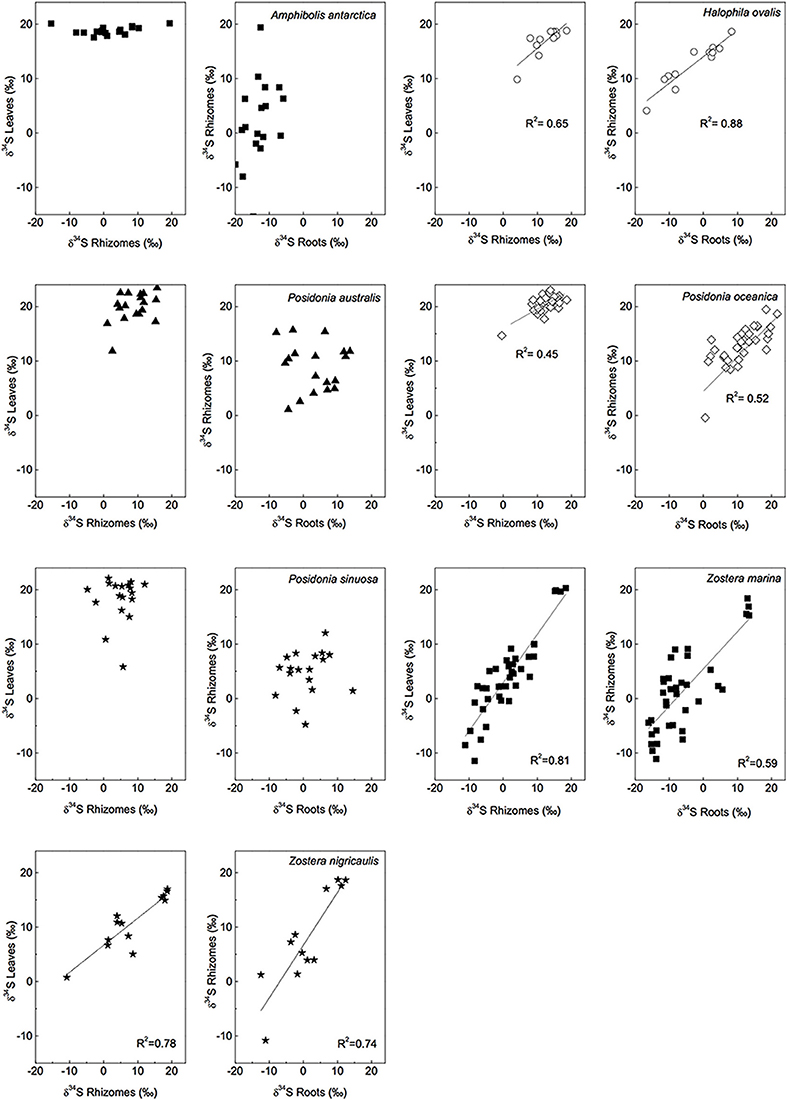

The δ34S of below-ground tissues are significantly lower than the leaves, on average +5.1 ± 8.6‰ for rhizomes and +0.1 ± 10.1‰ for roots (Table 2), suggesting that the accumulation of sulfide is higher in below-ground tissues. As observed for the leaves, P. oceanica has the highest δ34S values (+13.2 ± 2.8‰ and +11.3 ± 5.5‰ for rhizomes and roots, respectively, Figure 3), and Z. marina (+1.2 ± 7.0‰ and −5.2 ± 7.8‰ for rhizomes and roots, respectively, Figure 3) and R. maritima (−9.6 ± 6.4‰) show the lowest values. The lower values in roots compared to rhizomes suggests that the accumulation of sulfide-derived sulfur decrease from roots to rhizomes to leaves (Frederiksen et al., 2006, 2007) and is consistent with the intrusion of sulfide through roots (Pedersen et al., 2004). The intrusion into below-ground tissues is further supported by positive correlations between δ34S in roots and rhizome, and rhizomes and leaves for four out of nine seagrasses (Figure 4). The δ34S values show the largest variation for Z. marina, Zostera nigricaulis, and Halophila ovalis with values between −15 and +12.5‰ and steep regressions, whereas the Posidonia species and Amphibolis antarctica show no correlation between any of the tissues (Figure 4). A. antarctica leaves had values similar to seawater sulfate, suggesting that the sulfur source is seawater probably due to the long stem in this seagrass separating the leaves from the sediment. The lack of correlations for the larger species as Posidonia sp. and Amphibolis sp. suggests that the accumulation of sulfide is more complex compared to the smaller and less morphological differentiated seagrasses as Z. marina and H. ovalis. One of the seagrass species, Halophila engelmanni, has similar values in leaves and roots (+11.2 and +11.5‰, respectively) indicating no difference in sulfide intrusion between roots and leaves. This is a small species (<10 cm leaf length) with short distance between the sediment source and the leaves, and the sulfide intrusion may thus affect the entire plant due to short diffusion distances. δ34S has, however, only been reported from one study (Fry et al., 1982) and more data are needed to confirm the observations in particular as the similar sized H. ovalis show large difference between above and below-ground tissues (Table 2 and Kilminster et al., 2014).

Figure 4. Linear regressions of δ34S levels of different tissues and for several seagrass species, a R2 value is given if p < 0.05. [Data from various studies: same references as in Figure 3, Cambridge et al. (2012) and Holmer and Kendrick (2013)].

The δ34S values and correlations between tissues in the seagrasses studied so far thus suggests that that sulfide move from the below-ground tissues up to the leaves. Gaseous sulfide is considered to move freely in the plants, controlled by the gradient in partial pressures between the plant and the sediment (Borum et al., 2006). There are diaphragms at the nodes and in transition regions in the seagrasses, but these offer little resistance to gaseous diffusion (Larkum et al., 1989). Very rapid diffusion of oxygen is measured in seagrasses, in the order of 1 cm min−1, and is likely to be as fast for the sulfide gas (Borum et al., 2006). Sulfide may also exit the plant, e.g., through the meristem, where rapid gas exchange with the water column has been measured (Greve et al., 2003; Pulido and Borum, 2010; Raun and Borum, 2013). So far gaseous sulfide has not been detected in the leaves (Pedersen et al., 2004).

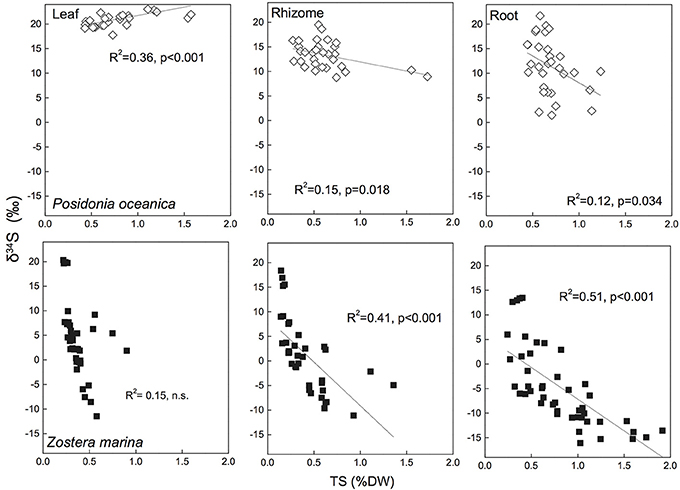

During the analysis of δ34S in the mass spectrometer the total sulfur (TS) content of the seagrass tissues is also obtained and by correlating TS with δ34S there appears to be a relationship between the two. There are relatively good correlations (R2 = 0.41–0.51) between TS content of the plants and decreasing δ34S in Z. marina rhizomes and roots (Figure 5), and similar correlations have been found for species with similar growth form as Z. marina, e.g., Cymodocea sp., Z. nigraulis (Cambridge et al., 2012; Holmer and Kendrick, 2013) and smaller species such as H. ovalis (Holmer et al., 2011; Cambridge et al., 2012). Also P. oceanica show correlation between TS and δ34S although the correlations are weaker (R2 = 0.12–0.15) due to the lower accumulation of sulfur in this seagrass (Figure 5). This suggests that the excess sulfur accumulating in the plant tissue is derived from sulfide in the sediments and that the increase in TS depends on the amount of sulfide entering into the plants.

Figure 5. Linear regressions between seagrass tissue total sulfur content (Tissue TS) and tissue δ34S in Posidonia oceanica (upper panel) and Zostera marina (lower panel) and leaves (left row), rhizomes (middle row) and roots (right row). The correlation coefficient (R2) and p-value for the linear regressions are given. The references are given in the supplementary material.

As the mass spectrometer analysis of TS and δ34S directly on plant tissue does not distinguish between organic and inorganic forms of sulfur, the available data does not allow for an identification of the different sulfur compounds accumulating in the tissues. Elemental sulfur [S0; assessed after methanol extraction by RP-HPLC after Zopfi et al. (2001)] is one reoxidation product of sulfide, which has been found accumulating in seagrass tissues (Holmer et al., 2005b, 2006; Frederiksen et al., 2006, 2007; Koch et al., 2007; Hasler-Sheetal, 2014). High S0 concentrations were found in Z. marina and Thalassia testudinum (up to 46% of TS), when plants were exposed to high sulfide concentrations in laboratory experiments (Holmer et al., 2005b; Koch et al., 2007; Mascaro et al., 2009; Hasler-Sheetal, 2014), but also field plants show accumulation of S0 and it is possibly a wide-spread mechanism for detoxification of sulfide in seagrasses (Holmer et al., 2005a, 2006; Frederiksen et al., 2006; Hasler-Sheetal, 2014). In field plants S0 primarily accumulates in the roots, and the highest tissue contents found are in Z. marina with about 0.5%DW, corresponding to 5–10% of TS content of the plants. A study of S0 in P. oceanica showed a shift in tissue isotopic signal to more negative values upon accumulation of S0, and extraction of S0 from the interior of the plants gave δ34S similar to the sediment sulfide, indicating that S0 is a direct oxidation product hereof (Frederiksen et al., 2007). As the accumulations of S0 generally are less than the observed increase in TS, this suggests that sulfide is incorporated in other, not yet identified, S-containing compounds (Mascaro et al., 2009; Hasler-Sheetal, 2014). S-containing thiols have been extracted from Z. marina and sulfate accumulated in both below-ground tissues and in leaves (Hasler-Sheetal, 2014). Sulfate has been suggested as an important storage compound of sulfur in terrestrial plants and marine algae, where for instance Chara accumulates crystal like structures of BaSO4 in their rhizoids and Desmarestia accumulates sulfuric acids in vacuoles (Rennenberg, 1984).

Sulfide is also taken up directly by the seagrasses (Hasler-Sheetal, 2014), and studies on maize, pumpkin, spinach, and spruce exposed to atmospheric sulfide demonstrate that sulfide is directly used for synthesis of cellular sulfur compounds (De Kok et al., 1989). Similarly Z. marina enzymatically metabolizes intruding sulfide via thiols into organic sulfur (Hasler-Sheetal, 2014). The later accumulates upon sulfide intrusion (Hasler-Sheetal, 2014). High levels of sulfide intrusion lead to accumulation of sulfur predominately in below ground tissues, 86% accumulated in roots and rhizome. In below ground tissues 67% precipitated as S0, 17% as organic sulfur, 12% as sulfate, and 4% as thiols (Hasler-Sheetal, 2014). A stable sulfur isotope analysis of the different sulfur compounds accumulating under sulfide intrusion revealed sediment sulfide as common source of thiols, organic sulfur and S0 in the roots and rhizomes (Hasler-Sheetal, 2014). In contrast all sulfur compounds in the leaves originated of a mixture of reoxidised sulfide and bulk pore water sulfate (Hasler-Sheetal, 2014). Also S-containing amino acids, such as taurine and thiotaurine, have been suggested as storage compounds of toxic sulfide in chemoautotrophic bacteria experiencing high sulfide concentrations (Joyner et al., 2003), a similar mechanism is possible in the seagrasses, but further studies are needed.

The δ34S in seagrass tissues reflects the δ34S values of the sedimentary sulfur sources, and the sediment source is quite variable as discussed above (Table 1) and may further show variations due to seasonal variations in temperature, sulfate reduction rates (sulfide production and concentration) or organic matter availability, site specific variations and sediment physical and chemical conditions (Holmer and Kendrick, 2013). There may thus be a discrepancy between the δ34S in the seagrass and the sediments due to differences in the timing of the variations. It is, however, possible to eliminate the dependence on sediment sulfide δ34S by calculating the factor Fsulfide. By using Fsulfide the sulfide intrusion into the seagrasses is corrected for the sediment δ34S values and Fsulfide represents the percentage of tissue sulfur, which is derived from sedimentary sulfide. Fsulfide is defined as the contribution (in percentage) of sedimentary sulfide to the sulfur in the plants, according to Frederiksen et al. (2006):

where δ34Stissue is the δ34S measured in the leaf, rhizome or root, δ34Ssulfate is the seawater value and δ34Ssulfide is the sediment sulfide value.

Variation in sulfide intrusion can be further reduced by analyzing Fsulfide in the young tissues (e.g., 1. and 2. leaf, rhizome or root bundle), representing the most recent growth, e.g., last couple of weeks for fast growing species like Zostera sp. and the last couple of months for the slow-growing species as Posidonia sp. Fsulfide quantifies the sulfide intrusion for direct comparison between types of tissue, species, and locations. This method does not take into account a potential redistribution of sulfur sources during senescence, as occurs for nitrogen in seagrasses (Marba et al., 2002), as there is a lack of knowledge on such redistribution of sulfur in seagrasses.

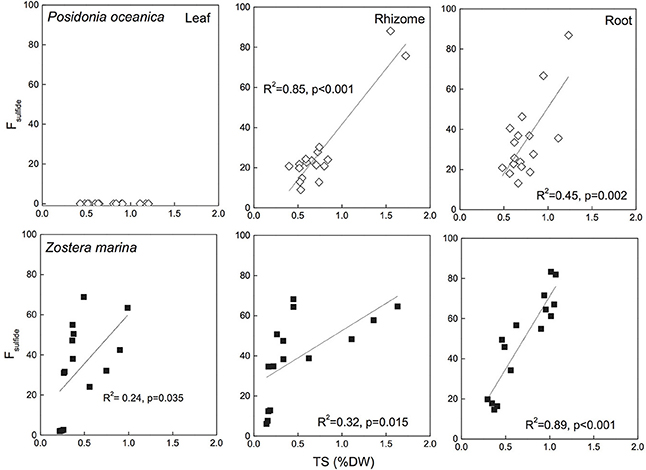

Fsulfide has been reported for several species and reflects the observations of δ34S with highest values in roots, followed by rhizomes and leaves (Figure 6 for P. oceanica and Z. marina). Fsulfide range between zero for leaves of P. oceanica and up to 96% in roots of T. testudinum. Highest values are found in leaves and respective roots of species like Z. marina (68%/86%), T. testudinum (21%/96%) and H. ovalis (11%/100%), whereas Posidonia sp. show the lowest values (0%/39%). Fsulfide correlates with TS and the correlations are generally stronger than observed for δ34S (Figure 6), and show that the removal of sediment variability increase the strength of Fsulfide as indicator of sulfide accumulation compared to δ34S.

Figure 6. Correlations between seagrass tissue total sulfur content (Tissue TS) and Fsulfide (fraction of tissue sulfur derived from sulfide) Posidonia oceanica (upper panel) and Zostera marina (lower panel) and leaves (left row), rhizomes (middle row), and roots (right row). The correlation coefficient (R2) and p-value for the linear regressions are given. No sulfide was detected in P. oceanica leaves, and the regression of Z. marina leaves was not significant. The references are given in the supplementary material.

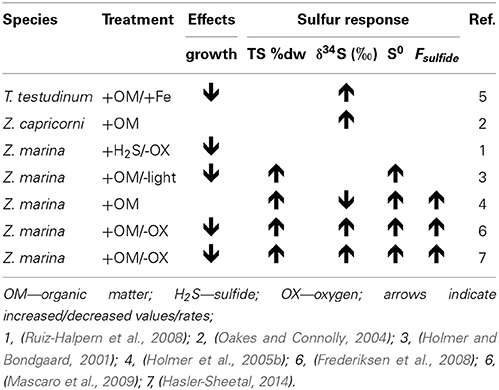

The δ34S and Fsulfide values exist from seagrasses growing under various types of stress, and low δ34S and high Fsulfide, indicative of enhanced sulfide intrusion compared to unstressed plants, is a general observation in seagrasses growing under stress (Table 3). For instance, high intrusion has been found in degrading seagrass meadows near fish farms, where sulfide intrusion increases toward the farms. The plants are exposed to anoxic stress and high sulfide concentrations in the sediments as well as increased nutrient availability and grazing by sea urchins (Frederiksen et al., 2007). High intrusion has also been found in degraded P. oceanica meadows affected by nutrient loading from boating activity compared to pristine sites (Marbà et al., 2007) and in P. oceanica growing under elevated temperatures (García et al., 2012).

Table 3. Collection of experimental seagrass studies where sulfide levels were manipulated and sulfur response parameters in the plants were assessed.

In Z. marina high intrusion has been found in plants exposed to low water column oxygen due to drifting algae (Holmer and Nielsen, 2007) and in plants exposed to hypoxia and at the same time growing in sediments with high organic matter pools and high sulfide concentrations (Mascaro et al., 2009). Similarly, direct exposure of T. testudinum to high pore water concentrations of sulfide (6 mM) and hypersalinity (65) resulted in declining δ34S in the plants and was followed by decreased plant performance (Koch et al., 2007). Combinations of increasing temperature and increasing biomass of the drifting algae Gracilaria comosa increased the sulfide intrusion in H. ovalis, and had detrimental impact on this small seagrass through interactive effects of shading, anoxia, and pore water sulfide (Holmer et al., 2011; Höffle et al., 2012). Where P. oceanica show negative performance under relatively little environmental pressure, e.g., low sulfide concentrations in the sediments (Calleja et al., 2007), harmful effects on the seagrasses with natural high Fsulfide in the tissues first accelerate when the plants suffer from hypoxia and/or anoxia (Mascaro et al., 2009; Martínez-Lüscher and Holmer, 2010). Seagrasses are able to tolerate sulfide intrusion as long as the sulfide can be: (i) reoxidized by oxygen present inside the plants in the aerenchyma (Pedersen et al., 2004) or in the rhizosphere (Van Der Heide et al., 2012) or (ii) detoxified by metabolisation via thiols into organic sulfur (Hasler-Sheetal, 2014). However, if both detoxification capacities are exceeded and sulfide intrudes into active tissues such as the meristem, then the performance of the seagrasses is negatively affected (Borum et al., 2005; Garcias-Bonet et al., 2008; Pulido and Borum, 2010; Korhonen et al., 2012). Negative effects of sedimentary sulfide can thus be expected when the reoxidation capacity of the plants is inhibited by environmental or biological stress. Such stress factors are for instance water column hypoxia, sediment anoxia (high biological activity in the sediments or anoxia due to macroalgae cover), increased temperature and shading (Figure 7).

Experimental remediation studies have been done to remove the sulfide pressure on seagrasses. Addition of iron to the sediments decreased the dissolved sulfide pools and at the same time δ34S increased in the leaves of T. testudinum and Halodule wrightii. This suggests that δ34S can be used as an indicator of stress removal in seagrasses (Chambers et al., 2001), and both species grew better after the reduction in sulfide levels in the sediments. Similar addition of iron to organic enriched sediments inhabited by P. oceanica showed reduced sulfide intrusion where the leaf δ34S increased from +18.2‰ in control plots to +20.5‰ in iron added plots (Marbà et al., 2007). These two studies were done in carbonate sediments with natural low iron content, and the added iron decreased the sulfide pressure in the sediments by increasing the precipitation of iron sulfide and reducing the pore water pool of sulfide. Both shoot survival and recruitment rates increased due to the relief of sulfide pressure. The mechanisms behind improved growth due to iron additions remain to be resolved, but the plant enzymatic activities increased, probably due to removal of inhibition by sulfide as well as higher iron availability, resulting in higher growth (Chambers et al., 2001; Holmer et al., 2005a).

The analysis of stable sulfur isotope signals in seagrasses shows, that sediment sulfide contributes significantly to the isotopic sulfur composition of seagrass tissues. Sulfide is intruding in the 27 species examined so far, remarkably also when they are growing under pristine conditions without human perturbations. Sedimentary sulfide contributes to the sulfur demand of the plants and are incorporated into the tissues like other essential nutrients. The intrusion of sulfide results in an increase in the TS content in seagrass tissues, and whether the accumulating sulfur is a by-product of a passive intrusion of sulfide or it is an adaptation to facilitate incorporation of S-molecules into the biological structure of the seagrasses remains to be explored. Whether the intrusion of sulfide is harmful to the seagrasses varies. Some species, such as P. oceanica, are quite sensitive to presence of sulfide, whereas other species, such as Z. marina and T. testudinum, tolerate high concentrations and frequent intrusions, and are first harmed when their reoxidation capacities of sulfide is exceeded. The links between Fsulfide and plant performance parameters suggest that δ34S can be used as indicator of seagrass health, but the indicator has to be developed further and should be used in combination with other indicators as seagrasses growing under stress are most often exposed to more than one stressor (Waycott et al., 2009; Thomsen et al., 2012).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Marianne Holmer was supported by the Danish Natural Science Foundation (12-127012) and Hasler-Sheetal was funded by the Danish Council of Independent Research (grant no. 09-067485).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fmars.2014.00064/abstract

Borum, J., Pedersen, O., Greve, T. M., Frankovich, T. A., Zieman, J. C., Fourqurean, J. W., et al. (2005). The potential role of plant oxygen and sulphide dynamics in die-off events of the tropical seagrass, Thalassia testudinum. J. Ecol. 93, 148–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2004.00943.x

Borum, J., Sand-Jensen, K., Binzer, T., Pedersen, O., and Greve, T. M. (2006). “Oxygen Movement in Seagrasses,” in Seagrasses: Biology, Ecology and Conservation, eds A. W. D. Larkum, R. J. Orth, and C. M. Duarte (Dordrecht: Springer), 255–270.

Böttcher, M., Brumsack, H.-J., and Dürselen, C.-D. (2007). The isotopic composition of modern seawater sulfate: I. Coastal waters with special regard to the North Sea. J. Mar. Syst. 67, 73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2006.09.006

Böttcher, M. E., Hespenheide, B., Brumsack, H.-J., and Bosselmann, K. (2004). Stable isotope biogeochemistry of the sulfur cycle in modern marine sediments: I. seasonal dynamics in a temperate intertidal sandy surface sediment. Isotopes Environ. Health Stud. 40, 267–283. doi: 10.1080/10256010410001678071

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Brodersen, K. E., Nielsen, D. A., Ralph, P. J., and Kühl, M. (2014). Oxic microshield and local pH enhancement protects Zostera muelleri from sediment derived hydrogen sulphide. New Phytol. doi: 10.1111/nph.13124. [Epub ahead of print].

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Calleja, M. L., Marba, N., and Duarte, C. M. (2007). The relationship between seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) decline and sulfide porewater concentration in carbonate sediments. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 73, 583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2007.02.016

Cambridge, M. L., Fraser, M. W., Holmer, M., Kuo, J., and Kendrick, G. A. (2012). Hydrogen sulfide intrusion in seagrasses from Shark Bay, Western Australia. Mar. Freshwater Res. 63, 1027–1038. doi: 10.1071/MF12022

Canfield, D. E. (2001). Biogeochemistry of sulfur isotopes. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 43, 607–636. doi: 10.2138/gsrmg.43.1.607

Canfield, D. E., Habicht, K. S., and Thamdrup, B. (2000). The Archean sulfur cycle and the early history of atmospheric oxygen. Science 288, 658–661. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.658

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Canfield, D. E., Jørgensen, B. B., Fossing, H., Glud, R., Gundersen, J., Ramsing, N. B., et al. (1993). Pathways of organic carbon oxidation in three continental margin sediments. Mar. Geol. 113, 27–40. doi: 10.1016/0025-3227(93)90147-N

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Carlson, P. R., and Forrest, J. (1982). Uptake of dissolved sulfide by Spartina alterniflora: evidence from natural sulfur isotope abundance ratios. Science 216, 633–635. doi: 10.1126/science.216.4546.633

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chambers, R. A., Fourqurean, J. W., Macko, S. A., and Hoppenot, R. (2001). Biogeochemical effects of iron availability on primary producers in a shallow marine carbonate environment. Limnol. Oceanogr. 46, 1278–1286. doi: 10.4319/lo.2001.46.6.1278

De Kok, L. J., Stahl, K., and Rennenberg, H. (1989). Fluxes of atmospheric hydrogen sulphide to plant shoots. New Phytol. 112, 533–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1989.tb00348.x

Fossing, H., and Jørgensen, B. B. (1989). Measurement of bacterial sulfate reduction in sediments: evaluation of a single-step chromium reduction method. Biogeochemistry 8, 205–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00002889

Frederiksen, M. S., and Glud, R. N. (2006). Oxygen dynamics in the rhizosphere of Zostera marina: a two-dimensional planar optode study. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 1072–1083. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.2.1072

Frederiksen, M. S., Holmer, M., Borum, J., and Kennedy, H. (2006). Temporal and spatial variation of sulfide invasion in eelgrass (Zostera marina) as reflected by its sulfur isotopic composition. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 2308–2318. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.2308

Frederiksen, M. S., Holmer, M., Díaz-Almela, E., Marba, N., and Duarte, C. (2007). Sulfide invasion in the seagrass Posidonia oceanica at Mediterranean fish farms: assessment using stable sulfur isotopes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 345, 93–104. doi: 10.3354/meps06990

Frederiksen, M. S., Holmer, M., Pérez, M., Invers, O., Ruiz, J. M., and Knudsen, B. B. (2008). Effect of increased sediment sulfide concentrations on the composition of stable sulfur isotopes (δ34S) and sulfur accumulation in the seagrasses Zostera marina and Posidonia oceanica. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 358, 98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2008.01.021

Fry, B., Scalan, R. S., Winters, J. K., and Parker, P. L. (1982). Sulfur uptake by salt grasses, mangroves, and seagrasses in anaerobic sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 46, 1121–1124. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(82)90063-1

García, R., Sánchez-Camacho, M., Duarte, C. M., and Marbà, N. (2012). Warming enhances sulphide stress of Mediterranean seagrass (Posidonia oceanica). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 113, 240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2012.08.010

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Garcias-Bonet, N., Marba, N., Holmer, M., and Duarte, C. M. (2008). Effects of sediment sulfides on seagrass Posidonia oceanica meristematic activity. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 372, 1–6. doi: 10.3354/meps07714

Greve, T. M., Borum, J., and Pedersen, O. (2003). Meristematic oxygen variability in eelgrass (Zostera marina). Limnol. Oceanogr. 48, 7. doi: 10.4319/lo.2003.48.1.0210

Hasler-Sheetal, H. (2014). Fate and Effect of Sulfate on Seagrasses: from Molecule to Ecosystem. PhD Dissertation, University of Southern Denmark.

Höffle, H., Wernberg, T., Thomsen, M. S., and Holmer, M. (2012). Drift algae, an invasive snail and elevated temperature reduce ecological performance of a warm-temperate seagrass, through additive effects. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 450, 67–80. doi: 10.3354/meps09552

Holmer, M., and Bondgaard, E. J. (2001). Photosynthetic and growth response of eelgrass to low oxygen and high sulfide concentrations during hypoxic events. Aquat. Bot. 70, 29–38. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3770(00)00142-X

Holmer, M., Duarte, C. M., and Marbá, N. (2005a). Iron additions reduce sulfate reduction rates and improve seagrass growth on organic-enriched carbonate sediments. Ecosystems 8, 721–730. doi: 10.1007/s10021-003-0180-6

Holmer, M., Frederiksen, M. S., and Mollegaard, H. (2005b). Sulfur accumulation in eelgrass (Zostera marina) and effect of sulfur on eelgrass growth. Aquat. Bot. 81, 367–379. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2004.12.006

Holmer, M., and Kendrick, G. (2013). High sulfide intrusion in five temperate seagrasses growing under contrasting sediment conditions. Estuar. Coast. 36, 116–126. doi: 10.1007/s12237-012-9550-7

Holmer, M., and Nielsen, R. M. (2007). Effects of filamentous algal mats on sulfide invasion in eelgrass (Zostera marina). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 353, 245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2007.09.010

Holmer, M., Pedersen, O., and Ikejima, K. (2006). Sulfur cycling and sulfide intrusion in mixed Southeast Asian tropical seagrass meadows. Botanica Marina 49, 91–102. doi: 10.1515/BOT.2006.013

Holmer, M., Wirachwong, P., and Thomsen, M. (2011). Negative effects of stress-resistant drift algae and high temperature on a small ephemeral seagrass species. Mar. Biol. 158, 297–309. doi: 10.1007/s00227-010-1559-5

Jørgensen, B. B. (1982). Mineralization of organic matter in the sea bed-the role of sulphate reduction. Nature 296, 643–645. doi: 10.1038/296643a0

Joyner, J. L., Peyer, S. M., and Lee, R. W. (2003). Possible roles of sulfur-containing amino acids in a chemoautotrophic bacterium-mollusc symbiosis. Biol. Bull. 205, 331–338. doi: 10.2307/1543296

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kallmeyer, J., Ferdelman, T. G., Weber, A., Fossing, H., and Jorgensen, B. B. (2004). A cold chromium distillation procedure for radiolabeled sulfide applied to sulfate reduction measurements. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2, 171–180. doi: 10.4319/lom.2004.2.171

Kennedy, H., Beggins, J., Duarte, C. M., Fourqurean, J. W., Holmer, M., Marbà, N., et al. (2010). Seagrass sediments as a global carbon sink: isotopic constraints. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 24. doi: 10.1029/2010GB003848

Kharlamenko, V. I., Kiyashko, S. I., Imbs, A. B., and Vyshkvartzev, D. I. (2001). Identification of food sources of invertebrates from the seagrass Zostera marina community using carbon and sulfur stable isotope ratio and fatty acid analyses. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 220, 103–117. doi: 10.3354/meps220103

Kilminster, K., Forbes, V., and Holmer, M. (2014). Development of a ‘sediment-stress’ functional-level indicator for the seagrass Halophila ovalis. Ecol. Indic. 36, 280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.07.026

Koch, M. S., Schopmeyer, S. A., Holmer, M., Madden, C. J., and Kyhn-Hansen, C. (2007). Thalassia testudinum response to the interactive stressors hypersalinity, sulfide and hypoxia. Aquat. Bot. 87, 104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2007.03.004

Korhonen, L. K., Macias-Carranza, V., Abdala, R., Figueroa, F. L., and Cabello-Pasini, A. (2012). Effects of sulfide concentration, pH, and anoxia on photosynthesis and respiration of Zostera marina. Cienc. Mar. 38, 625–633. doi: 10.7773/cm.v38i4.2034

Kylin, A. (1960). The incorporation of radio−sulphur from external sulphate into different sulphur fractions of isolated leaves. Physiol. Plant. 13, 366–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1960.tb08039.x

Lamers, L. P. M., Govers, L. L., Janssen, I. C. J. M., Geurts, J. J. M., Van Der Welle, M. E. W., Van Katwijk, M. M., et al. (2013). Sulfide as a soil phytotoxin - a review. Front. Plant Sci. 4:268. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00268

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Larkum, A., Roberts, G., Kuo, J., and Strother, S. (1989). “Gaseous movement in seagrasses,” in Biology of Seagrasses. A Treatise on the Biology of Seagrasses with Special Reference to the Australian Region, eds A. Larkum, A. McComb, and S. Shepherd (Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers BV), 686–722.

Marbà, N., Calleja, M., Duarte, C., Álvarez, E., Díaz-Almela, E., and Holmer, M. (2007). Iron additions reduce sulfide intrusion and reverse seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) decline in carbonate sediments. Ecosystems 10, 745–756. doi: 10.1007/s10021-007-9053-8

Marba, N., Hemminga, M. A., Mateo, M. A., Duarte, C. M., Mass, Y. E. M., Terrados, J., et al. (2002). Carbon and nitrogen translocation between seagrass ramets. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 226, 287–300. doi: 10.3354/meps226287

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Martínez-Lüscher, J., and Holmer, M. (2010). Potential effects of the invasive species Gracilaria vermiculophylla on Zostera marina metabolism and survival. Mar. Environ. Res. 69, 345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2009.12.009

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mascaro, O., Valdemarsen, T., Holmer, M., Perez, M., and Romero, J. (2009). Experimental manipulation of sediment organic content and water column aeration reduces Zostera marina (eelgrass) growth and survival. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 373, 26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2009.03.001

Mittermayr, A., Hansen, T., and Sommer, U. (2014). Simultaneous analysis of δ13C, δ15N and δ34S ratios uncovers food web relationships and the trophic importance of epiphytes in an eelgrass Zostera marina community. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 497, 93–103. doi: 10.3354/meps10569

Monaghan, J. M., Scrimgeour, C. M., Stein, W. M., Zhao, F. J., and Evans, E. J. (1999). Sulphur accumulation and redistribution in wheat (Triticum aestivum): a study using stable sulphur isotope ratios as a tracer system. Plant Cell Environ. 22, 831–839. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00445.x

Oakes, J. M., and Connolly, R. M. (2004). Causes of sulfur isotope variability in the seagrass, Zostera capricorni. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 302, 153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2003.10.011

Orth, R. J., Carruthers, T. J. B., Dennison, W. C., Duarte, C. M., Fourqurean, J. W., Heck, K. L., et al. (2006). A global crisis for seagrass ecosystems. Bioscience 56, 987–996. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[987:AGCFSE]2.0.CO;2

Papadimitriou, S., Kennedy, H., Rodrigues, R. M. N. V., Kennedy, D. P., and Heaton, T. H. E. (2006). Using variation in the chemical and stable isotopic composition of Zostera noltii to assess nutrient dynamics in a temperate seagrass meadow. Org. Geochem. 37, 1343–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2006.01.007

Pedersen, O., Binzer, T., and Borum, J. (2004). Sulphide intrusion in eelgrass (Zostera marina L.). Plant Cell Environ. 27, 595–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01173.x

Pulido, C., and Borum, J. (2010). Eelgrass (Zostera marina) tolerance to anoxia. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 385, 8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2010.01.014

Raun, A. L., and Borum, J. (2013). Combined impact of water column oxygen and temperature on internal oxygen status and growth of Zostera marina seedlings and adult shoots. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 441, 16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2013.01.014

Raven, J. A., and Scrimgeour, C. M. (1997). The influence of anoxia on plants of saline habitats with special reference to the sulphur cycle. Ann. Bot. 79, 79–86. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a010309

Raven, J. A., Walker, D. I., Johnston, A. M., Handley, L. L., and Kübler, J. E. (1995). Implications of 13C natural abundance measurements for photosynthetic performance by marine macrophytes in their natural environment. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 123, 193–205. doi: 10.3354/meps123193

Rees, C. E., Jenkins, W. J., and Monster, J. (1978). The sulphur isotopic composition of ocean water sulphate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 42, 377–381. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(78)90268-5

Rennenberg, H. (1984). The fate of excess sulfur in higher-plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 35, 121–153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.35.060184.001005

Ruiz-Halpern, S., Macko, S. A., and Fourqurean, J. W. (2008). The effects of manipulation of sedimentary iron and organic matter on sediment biogeochemistry and seagrasses in a subtropical carbonate environment. Biogeochemistry 87, 113–116. doi: 10.1007/s10533-007-9162-7

Short, F. T., Polidoro, B., Livingstone, S. R., Carpenter, K. E., Bandeira, S., Bujang, J. S., et al. (2011). Extinction risk assessment of the world's seagrass species. Biol. Conserv. 144, 1961–1971. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.04.010

Thomsen, M. S., Wernberg, T., Engelen, A. H., Tuya, F., Vanderklift, M. A., Holmer, M., et al. (2012). A meta-analysis of seaweed impacts on seagrasses: generalities and knowledge gaps. PLoS ONE 7:e28595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028595

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Van Der Heide, T., Govers, L. L., De Fouw, J., Olff, H., Van Der Geest, M., Van Katwijk, M. M., et al. (2012). A three-stage symbiosis forms the foundation of seagrass ecosystems. Science 336, 1432–1434. doi: 10.1126/science.1219973

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Waycott, M., Duarte, C. M., Carruthers, T. J., Orth, R. J., Dennison, W. C., Olyarnik, S., et al. (2009). Accelerating loss of seagrasses across the globe threatens coastal ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12377–12381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905620106

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Winner, W. E., Smith, C. L., Koch, G. W., Mooney, H. A., Bewley, J. D., and Krouse, H. R. (1981). Rates of emission of H2S from plants and patterns of stable sulfur isotope fractionation. Nature 289, 672–673. doi: 10.1038/289672a0

Zopfi, J., Kjaer, T., Nielsen, L. P., and Jorgensen, B. B. (2001). Ecology of Thioploca spp.: nitrate and sulfur storage in relation to chemical microgradients and influence of Thioploca spp. on the sedimentary nitrogen cycle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 5530–5537. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5530-5537.2001

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: δ34S, sediment sulfide, seagrass performance, uptake and fate of sulfur

Citation: Holmer M and Hasler-Sheetal H (2014) Sulfide intrusion in seagrasses assessed by stable sulfur isotopes—a synthesis of current results. Front. Mar. Sci. 1:64. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2014.00064

Received: 10 September 2014; Paper pending published: 15 October 2014;

Accepted: 04 November 2014; Published online: 27 November 2014.

Edited by:

Douglas Patrick Connelly, National Oceanography Centre, UKReviewed by:

John Robert Helms, Old Dominion University, USACopyright © 2014 Holmer and Hasler-Sheetal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marianne Holmer, Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Campusvej 55, DK-5230 Odense M, Denmark e-mail:aG9sbWVyQGJpb2xvZ3kuc2R1LmRr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.