95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Lang. Sci. , 11 February 2025

Sec. Language Processing

Volume 4 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/flang.2025.1453230

This article is part of the Research Topic Interacting factors in the development of discourse practices from childhood to adulthood View all 5 articles

Research on feedback in writing has predominantly focused on its effectiveness in improving surface-level linguistic accuracy, with limited attention to how students perceive and engage with written qualitative feedback as an interactive tool for writing development. This study addresses this gap by emphasizing the role of written qualitative feedback, defined as descriptive comments that address both content and linguistic element, promoting deeper engagement and critical thinking in student writing. Using an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design, the study examines the conception of written qualitative feedback held by 107 English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners in China. Over an academic semester, each learner produced three argumentative texts and received written qualitative feedback in three formats. Quantitative data from an adapted Conception of Written Feedback questionnaire reveals two predominant patterns in their conception of written qualitative feedback: (1) engaging with positive emotion and active use or (2) ignoring with defensiveness. To explore potential explanations for these patterns, a purposeful subsample of 10 learners participated in semi-structured interviews, conceptualizing the role of feedback in their writing practices. Qualitative findings indicate that learners perceive feedback along a continuum as an instructional tool, evaluative system, cognitive guide, dialogic conversation, and catalyst for personal change. By triangulating quantitative results and qualitative findings, the study demonstrates how personalized educational interaction in the form of written qualitative feedback facilitates adolescents' transition from competent language use to higher-order argumentative skills and agentic approaches to writing development. The study adds to a growing literature on adolescent writing development from the lens of interactive teaching and learning.

Writing is a social activity wherein writers select appropriate language to communicate with their target audience and achieve specific purposes (Heap, 1989; Magnifico, 2010; Bazerman, 2016). However, in most English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classrooms, writing is often implemented as a monological activity, where learners write for exams and expect minimal feedback from examiners other than a holistic writing quality score (Wang et al., 2024). As a result, meaningful interaction is largely missing from students' learning processes, leading to inadequate developmental outcomes and the lack of motivation to write (Wright et al., 2021). Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the possible interacting factors in writing activities and understand their roles in contributing to the development of such discourse practices.

Feedback provides a valuable perspective to examine the interacting nature of writing. In writing research, feedback has been categorized into several distinct types based on its purpose and implementation, each influencing students' learning in different ways. Written corrective feedback (WCF), a well-documented type, focuses on linguistic accuracy by highlighting and correcting surface-level errors, such as grammar and spelling (Bitchener and Storch, 2016). More recently, studies have called for a broader focus beyond error correction to consider the emotional and cognitive dimensions of WCF, as students' engagement is influenced by how they perceive and react to this feedback (Han and Hyland, 2019; Lee, 2024). A different method of delivering corrective feedback, such as recast, has also been shown to improve EFL learners' writing performance (Banaruee et al., 2022). While corrective feedback has been widely explored in L2 writing, some researchers have proposed feedback types that emphasize content and higher-order thinking. Content-focused feedback, for instance, targets idea development, coherence, and organization, helping students refine their arguments and improve the overall quality of their texts (Lipnevich and Smith, 2009; Matsumura et al., 2002; Evans, 2013). Similarly, higher-order feedback addresses the structure and clarity of students' arguments, fostering critical thinking and deeper engagement with the content (Chan and Lam, 2010; Moser, 2020).

The present study focuses on written qualitative feedback, which we define as descriptive and detailed written feedback—including marginal and summative comments—as well as rubric-based evaluation reports that address both content and linguistic elements of students' writing. By providing explanations, highlighting strengths, and suggesting areas for improvement, written qualitative feedback integrates the cognitive, social-affective, and structural dimension of feedback (Yang and Carless, 2013). It is designed to facilitate deeper engagement with the process of learning (Lizzio and Wilson, 2008; Hyland and Hyland, 2006), improve learners' ability to self-regulate their writing (Wingate, 2012), and enhance overall writing development and quality (Pritchard and Honeycutt, 2006). Despite the potential benefits of written qualitative feedback, its effectiveness depends on students' understanding and engagement. Past research has shown that even the most well-intentioned feedback may not lead to improvement if students are unable or unwilling to utilize it (Van der Kleij and Lipnevich, 2021). Interaction is bi-directional; thus, at the same time of understanding which types of feedback are beneficial to students, it is probably more urgent to investigate how students define, perceive, and conceive feedback in their writing practices.

This focus is aligned with researchers' convergence on feedback receptivity (Weaver, 2006; Walker, 2009; Lipnevich et al., 2016; Winstone et al., 2016; Hattie and Clarke, 2019; Jönsson and Panadero, 2018) and leads to the development of students' conceptions of feedback, which refers to the understanding and beliefs that students hold about the purpose and value of feedback in the learning process (Peterson and Irving, 2008; Brown et al., 2016). Peterson and Irving's (2008) seminal study on students' conceptions of feedback investigates secondary school students' understandings of feedback's purpose, perceived impact on learning, and circumstances in which feedback was deemed irrelevant. Their findings reveal that secondary school students' conceptions of feedback “largely center on their own interests and needs and there was a strong focus on the need or desire for a grade and strong guidance from teachers” (p. 247). In addition, their study leads to the development of the Students' Conceptions of Feedback Inventory (SoCF), which has been widely employed in educational settings worldwide (Brown et al., 2014, 2016). Studies adopting SoCF have found that students who view feedback as an opportunity to learn and improve are more likely to engage in self-regulated learning practices compared to those who perceive feedback as a judgment of their abilities or a means to receive praise and rewards (Brown et al., 2014). Furthermore, students' conceptions of feedback are shaped by their prior experiences with feedback—those with positive past experiences are more likely to perceive it as helpful and relevant to their learning, while those with negative experiences tend to perceive feedback as irrelevant or unhelpful (Brown et al., 2016).

Although research focusing on students' conceptions of written feedback is limited, several studies in EFL and L2 writing have emphasized the importance of considering learners' individual traits and styles. Learning preferences and cognitive styles significantly shape how students perceive and engage with feedback. For instance, Banaruee et al. (2022) found that EFL learners with synoptic learning styles performed better in reading tasks, suggesting that aligning feedback with students' cognitive styles can enhance their engagement and performance. Similarly, personality traits also influence how students respond to feedback. Extroverts tend to benefit more from explicit feedback, while introverts respond better to implicit feedback, indicating that feedback effectiveness may vary depending on individual characteristics (Banaruee et al., 2017).

Building upon this line of research, the present study uses an explanatory sequential mixed methods design (Greene et al., 1989; Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2003; Johnson and Turner, 2003; Creswell et al., 2003; Creswell, 2005; Hanson et al., 2005) to understand EFL learners' conceptions of written qualitative feedback and explore how such conceptions contribute to their writing development. We aim to address three specific research questions:

1) How many factors emerge from EFL learners' conception of written qualitative feedback?

2) To what extent do these conception factors contribute to students' argumentative writing proficiency?

3) How do EFL learners define feedback and understand the role of written qualitative feedback in shaping their writing practices?

The first two research questions are addressed through quantitative analysis of learners' responses to a questionnaire assessing students' conception of feedback as well as their associations with writing quality scores. The third question is explored through qualitative analysis of their self-reflection in semi-structured interviews. The findings are discussed in relation to pedagogical implications that highlight feedback as an educational interaction through which adolescents make agentic choices in their writing practices.

The study was part of a larger writing intervention conducted at a public high school in eastern China. Co-designed by the researchers and school teachers, the intervention included a 90-min English argumentative writing class and a practice lesson, held on alternative weeks. Over the course of an academic semester (from September 2022 to January 2023), participants engaged in three argumentative writing tasks. The writing prompts were selected from the “Word Generation” program, a curriculum designed to cultivate adolescents' academic language and complex reasoning through argumentative writing (Jones et al., 2019). It included topics closely related to adolescents' life and adaptable to different cultural contexts (e.g., Should schools sell junk food? Should animals be used for scientific experiments?), allowing students to engage in argumentative thinking and writing about socially and scientifically controversial issues.

The writing tasks were completed in the classrooms during the practice session. Then, students' handwritten essays were mailed to the researchers' lab, where a group of trained research assistants transcribed them into Word documents and provided detailed written feedback along with an evaluation report targeting different aspects of writing, including position, support, organization, and clarity. The school teachers then received the Word documents, printed them out, and distributed to the students.

Three distinct formats of qualitative written feedback were provided:

• Marginal Comments (See Figure 1): comments consisting of questions, suggestions, and remarks placed alongside specific sections of the text. Instead of directly correcting students' language or argumentative structure, these comments highlight strengths and identify areas for improvement within specific argumentative moves. By asking open-ended questions, offering encouragement and praise, pointing out weak points, and providing scaffolding support, marginal feedback invites students to reflect on their writing strategies, consider alternative approaches, and articulate their thought processes (Biancarosa and Snow, 2004; Shute, 2008; Graham et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017).

• Summative Comments: Summative comments are provided at the end of the essay to offer a holistic evaluation of the student's overall performance. These comments synthesize the feedback given throughout the text and point out broader areas of strength or aspects in need of further development (Ferris et al., 1997; Berzsenyi, 2001; Patchan et al., 2009).

“[Marker] You did a fantastic job presenting detailed reasoning that clearly shows your thought process! However, your position could be clearer. I suggest stating your stance at the beginning to guide your reader. If you support rap censorship, try expanding on why censorship is necessary instead of just refuting the claim that 'listening to rap leads to aggression.' For example, think about why harmful activities like smoking aren't banned. What factors shape these decisions? Listing potential reasons and uncovering hidden rationales will make your argument even more persuasive. You're clearly a great critical thinker—I look forward to reading your next piece!”

• Rubric-Based Writing Evaluation Report (See Figure 2): The rubric-based writing evaluation report uses standardized rating criteria to evaluate students' performance across multiple dimensions, such as content organization, coherence, and use of evidence. While rubric-based evaluation is often associated with traditional feedback, our evaluation report includes a narrative explanation for each rating, linking the quantitative evaluation to qualitative insights (Nordrum et al., 2013; Sáiz-Manzanares et al., 2017). By the end of the semester, the report also tracks students' progress in areas such as syntactic complexity and lexical complexity. This detailed evaluation is further visualized using radar graphs, which provide a clear depiction of students' performance across different dimensions, offering a nuanced understanding of their writing development over time (Uttal and Doherty, 2008).

After the final round of written feedback and evaluation reports were returned to students, they completed a questionnaire to convey their conceptions of feedback.

Participants included a total of 120 EFL learners enrolled in the participating school. Of these, 112 students completed the follow-up questionnaire. After matching the questionnaire responses to the corresponding essays, only 107 participants had complete data for both. Of these 107, 54 were 9th graders and 53 were 10th graders. The sample is relatively balanced by gender with 51% female students and 49% male students. All the students in the study are of Chinese ethnicity. They self-reported speaking mandarin Chinese as their native language and had learned English as a foreign language for ~8 to 10 years. According to the school's placement test, all participants had achieved intermediate-level proficiency (B1 or B2) by the time they entered 9th grade. Among all participants, 10 students were selected for subsequent qualitative analysis based on two criteria: (1) they have indicated the willingness to communicate in follow-up interviews; (2) their writing demonstrates distinctive patterns of development over the academic semester. Detailed demographic characteristics of this sub-sample of participants are shown in Table 1. Consent forms were obtained from both participants and their guardians before any data were collected.

The 24-item Conceptions of Written Feedback (CoWF) questionnaire was adapted from Student Conceptions of Feedback (SCoF-II) Inventory (Irving et al., 2021). Adaptations were made to align with the current study's research context: (1) items were rephrased to focus narrowly on writing instead of general academic tasks; (2) the feedback giver was changed from “teachers” to “markers” to better fit the design of the writing intervention; (3) the items were reviewed and revised for clarity but were not translated, as the questionnaire was administered only in English. This decision was supported by several factors: first, the entire study was conducted in an English-medium class, where all writing interventions, assignments, and feedback were in English. Second, a pilot study was conducted with a small group of students to ensure they understood the language used in the questionnaire, and the results indicated that students were able to comprehend the terminology and respond effectively. Furthermore, the research team consulted the students' teachers, who confirmed that the students possessed the necessary English proficiency to complete the survey without translation. Given these considerations, the research team decided that administering the questionnaire in English was most appropriate to maintain consistency and alignment with the language context of the study.

The items were classified into five categories to characterize various aspects participants could consider while reflection on the conception of feedback, including: Usage, Enjoyment, Ignoring, Expectations, and Comments on Raters. The questionnaire was designed on a five-point rating scale, in which participants chose to indicate their degree of agreement with certain statements (1-strongly disagree, 2-mostly disagree, 3-slightly-agree, 4-mostly agree, 5-strongly agree). For instance, “I make active use of the feedback I get from my markers.”

To evaluate the overall writing quality of argumentative essays, we implemented a scoring rubric that had been validated in previous research (Deng et al., 2022; Phillips Galloway et al., 2020). This rubric, informed by the National Assessment Governing Board (2010) Writing Framework, measured writing quality across four dimensions: Position, Support, Organization, and Clarity (See Figure 3):

- The Position dimension assessed the number of perspectives being considered.

- The Support dimension evaluated the level of depth, complexity, elaboration, and connectedness of ideas in essays in support of its position.

- The Organization dimension examined the logical and coherent structuring of the essay.

- The Clarity dimension gauged the precision and unambiguous conveyance of information in essay.

Figure 3. Radar graph and line charts demonstrating developmental trend in specific dimensions of argumentative writing.

Each dimension was scored on a four-point scale, with higher scores reflecting superior quality. These dimensional scores were then holistically considered to determine the final designation of writing quality levels. Specifically, high-quality writing was charactered by essays scoring 4 points on at least three dimensions; medium-quality writing comprised of those scoring 3 or 4 on at least two dimensions; and low-quality writing included those scoring 2 or below on all dimensions.

A team of four human raters underwent rigorous training to ensure consistency in scoring. To verify inter-rater reliability, 20% of the essays were double-scored, achieving a κ = 0.89. The remaining 80% of the essays were independently scored by the four raters. This robust scoring rubric and training of raters ensured a reliable and objective evaluation of the holistic writing quality in argumentative essays.

We used semi-structured interviews to delve deeper into participants' conceptions and provide detailed explanations of the quantitative results. Questions were designed based on Peterson and Irving's (2008) guiding questions and informed by quantitative results revealed in the previous phase of analysis. The questions were organized to investigate EFL learners' conceptions of definitions, perceived effects, and irrelevant situations of written qualitative feedback. Two major sections were designed to cover conceptions of written qualitative feedback and their correlation with writing proficiency development.

The first part of the interview revolved around participants' conceptions of written qualitative feedback. Open-ended questions were designed to investigate participants' experience, feelings, and definitions of written qualitative feedback. Based on the previous quantitative data, participants were invited to share specific examples of how they engage or ignore written qualitative feedback. During the process of interview, participants received their first piece of personalized writing performance reports and were asked to select comments they found to be the most impressive. The second part of the interview explored how conceptions of written qualitative feedback correlate and contribute to writing proficiency development. Participants were first asked to self-reflect their writing development patterns, followed by detailed analysis and explanation from the researcher. Close-ended questions were posed to testify participants' level of agreement and open-ended questions followed to investigate participants' perceived relationship between feedback and writing development.

Each interview lasted for 30–40 min. Five interviews were conducted in person at the school, and five were completed online. Both offline and online interviews were transcribed verbatim for in-depth analysis. Participants were allowed to freely switch between English and Mandarin during their interview for optimal communicative efficiency.

To address the first research question, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed to examine the dimensionality of the Conceptions of Written Feedback (CoWF) questionnaire (See Figure 4). To address the second research question, multi-level regression models were built to investigate the associations between the CoWF factors (emerging from the first research question) and students' writing quality scores, i.e., position, evidence, organization, language, and overall writing quality. We adopted multi-level regression analysis because each student produced three argumentative essays during the academic semester, thus, texts data were nested within individuals. We fit individual-level random slopes so that both within-individual and between-individual variance could be accounted in the analysis.

The interview data underwent a detailed qualitative analysis, utilizing a combination of deductive and inductive approaches (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Deductive analysis was guided by a theoretical framework based on Peterson and Irving's (2008) codes and the CoWF factors, serving as predetermined references. Concurrently, inductive analysis was applied to allow for the identification of new, emerging themes that were not anticipated by the theoretical framework.

The first author independently coded all interview transcripts using the NVivo software, starting with the predetermined codes from the theoretical framework. Throughout this process, the coding scheme was continuously refined to incorporate new themes that surfaced from the data. Codes were grouped into broader categories that reflected participants' perceptions and interactions with feedback, such as “definitions of written feedback,” “positive responses to feedback,” and “negative responses to feedback.” The coding process was iterative and involved continuous re-evaluation to ensure clarity and consistency. To enhance reliability, the second author and a research assistant reviewed the initial codes and categories. Final categories were collaboratively refined through discussions and re-readings of the transcripts to reach consensus.

Following the qualitative analysis, themes were mapped onto the CoWF factors to ensure alignment between quantitative and qualitative findings. This triangulation allowed us to create a cohesive representation of students' conceptions of feedback, highlighting areas of agreement and divergence between their questionnaire responses and interview insights. By integrating both data sources, we were able to model how individual perceptions of feedback influence students' writing practices, providing a comprehensive understanding of their engagement with different feedback types.

Pairwise correlation analysis revealed moderate to strong correlations among all items in the Conception of Written Feedback (CoWF) questionnaire, suggesting adequate inter-item consistency. Principal Component Analysis revealed that the 24 items fell onto two primary factors (with an Eigenvalue higher than 1), explaining ~65% of the variance in the entire questionnaire (see Table 2). An in-depth evaluation of specific items associated with each factor revealed distinctive patterns. For the first factor, 15 items positively loaded onto it with eigenvectors higher than 0.20, all of which featured endorsement of the active use, enjoyment, high expectations, and positive comments to markers. For instance, participants gave positive rating to statements, such as “I use feedback to set goals or targets for the next writing task”; “I enjoy getting feedback on my writing”; and “I know I have done well when my score or grade is better than last time.” Thus, the first factor was named Engaging feedback with positive emotion and active use.

For the second factor, eight items loaded onto it with eigenvectors higher than 0.20, all of which featured negative perception of feedback. Specifically, participants rated higher on statements such as “I ignore bad grades or comments;” “I already know how good/poor my writing is before I get my scored writing back;” “Markers' comments don't tell me anything useful.” Thus, the second factor was named Ignoring feedback with defensiveness.

We conducted pairwise correlation analysis and multi-level regression modeling to investigate the associations between EFL learners' conceptions of written qualitative feedback and writing development, as operationalized by the writing proficiency scores on four dimensions (i.e., position, support, organization, and clarity) as well as overall quality. As shown in Table 3, the two factor scores generated from the previous step—i.e., Engaging feedback with positive emotion and active use and Ignoring feedback with defensiveness—only showed weak correlations with writing quality. Specifically, among all dimensions of writing proficiency scored, Engaging feedback was found to be positively and significantly associated with position in writing (r = 0.09, p<0.05), suggesting that learners with positive conception of feedback were more likely to incorporate multiple perspectives in their writing, resulting in more nuanced position statements. On the other hand, Ignoring feedback was found to be negatively associated with clarity of writing (r = −0.14, p < 0.05), indicating that learners holding a negative conception of feedback tended to demonstrate less clear language usage in writing. Limited correlations were found between CoWF factors and other writing proficiency scores.

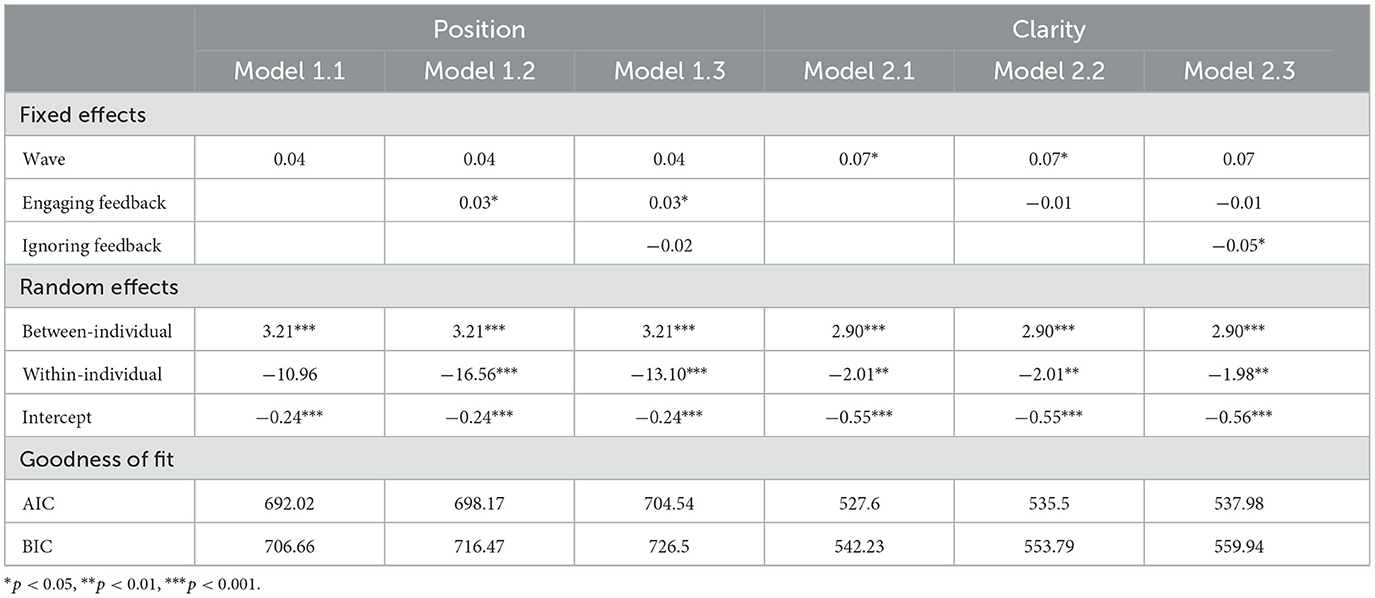

Informed by the results from the pairwise correlation analysis, we built a series of multi-level regression models to further explore the predictive power of CoWF factors to writing position and clarity, the two writing proficiency scores significantly correlated with CoWF factors. In regression models presented in Table 4, we used writing position and clarity as outcome variables, wave of data collection as a control variable, Engaging feedback factor and Ignoring feedback factors as main predictors. Results showed that Engaging feedback was positively and significantly associated with writing position (β = 0.03, p < 0.05), and Ignoring feedback was negatively and significantly associated with writing clarity (β = −0.05, p < 0.05), holding other variables constant. Statistical interactions were tested between CoWF factors and wave on both outcome variables, but none was significant, suggesting that the predictive effects were consistent over time.

Table 4. Multi-level regression analysis using CoWF factors to predict writing position and clarity scores.

The analysis of responses to semi-structured interview questions revealed three overarching themes in students' conceptions of written qualitative feedback: (1) students possessed a hierarchical set of definitions of written qualitative feedback, (2) students engaged with written qualitative feedback in four distinct ways, and (3) students ignored written qualitative feedback for five different reasons. Table 5 provides a summary of supporting evidence for each theme.

Chinese EFL learners tended to define written qualitative feedback based on its practical utility. As Rong succinctly put it, written qualitative feedback was used “to point out what I have done very well and not very appropriate, like some grammar mistakes or the overly absolute words used in the essay.” This functional perspective was echoed by Yuan, who stated that she found markers' comments valuable as they pinpointed precisely what she did wrong and where she could improve. Serving as a handy tool for learners, written qualitative feedback worked beyond “pointing out” issues. Yue exemplified other functions of written qualitative feedback, ranging from providing a thorough evaluation of every aspect of his essay, to reviewing the flow of his language, and making changes to specific wording, sentence structure, and logic.

Some learners perceive written qualitative feedback as an integrated system. For Lin, written qualitative feedback came as a report with her initial essay accompanied by detailed comments and modifications on the right margin. These comments addressed grammar, structure, content, and exploratory ideas, serving as a comprehensive feedback system. For Wen, who adopted a similar systematic lens, written qualitative feedback was composed of three main sections: grammar correction, content suggestions, and scoring, which together formed a structured approach to improvement. According to Rong, written qualitative feedback was “really satisfying owing to its wonderful combination of both detailed comments made by professional markers and thorough assessments for each aspect of students' writing skills.” By its form, written qualitative feedback was conceived as a system since it comprised of detailed margin comments and a transparent scoring rubric. By its content, as written qualitative feedback addressed every component of an essay, it left learners an impression that it was holistic, comprehensive, and systematic.

Taking the role of a marker into consideration, some learners viewed written qualitative feedback as valuable guidance from experienced individuals. Le explained, “It is guidance from someone who has been down this road before.” This perspective was shared by Yuan, who found the feedback process to be a new and unexpected form of learning support. She contrasted this with her classroom experience, saying, “I had never experienced such a way of receiving feedback. Usually, our class teachers would find two sample essays at most and identify their advantages and disadvantages. I never received a systematic feedback report like this, of me, and only for me.” The feeling was echoed by Lin, who highlighted the urgent need for guidance on ideas, opinions, and embellishments, areas where automated tools or general feedback fall short. Such an individualized written qualitative feedback provided her with new perspectives and directions, helping her to improve her essays in ways she had not considered before.

Despite most of the markers are strangers to the students, some learners felt a sense of personal communication through the interaction of giving and receiving feedback. Zu likened the feedback process to a dialogue, noting that it involved a human element that other ways of assessments lacked. She said, “I can perceive the communication between human beings because giving and receiving feedback on an essay is a dialogue itself. Exams, however, only provide a ruthless score without telling you why the points were deducted.” Receiving written qualitative feedback from a human marker also seemed to transcend the boundary of time and space, a feeling that can hardly be replaced by machine. As Tong mentioned, “Reading those words made me feel like having a conversation with the marker face-to-face. Compared with a ChatGPT, which is only generating word after word automatically, I prefer receiving comments from a real person.” The existence of an authentic audience, therefore, motivated EFL learners to approach writing as if they were in a conversation where they needed to deduct, understand, and negotiate with others' perspectives. For Rong, this came as a sense of curiosity to read the markers' minds, “When I was writing, I was always curious about how the markers would approach this topic if they were me.”

Written qualitative feedback also has the potential to drive personal transformation in learners. Yuan wrote in the opened-end survey, “My essays were rarely graded in such a discreet way: it transformed my vague feeling of ‘something could be improved' into ‘I know where to work on.”' For her, written qualitative feedback helped bridge the gap between her current performance and her ideal goals. Rong recounted how feedback improved her ability to write argumentative essays, leading to significant progress over time. She described the initial difficulty of writing her first essay and the ease with which she completed her final one, “At the beginning of this program, writing an argumentative essay was like peeling a toothpaste. With every difficult push, a limited number of words were written down. Now, I can compose an essay with ease, knowing exactly how to organize arguments and counterarguments in my mind and then, demonstrate them on the paper.” This process transformed her writer's identity and instilled a sense of pride and accomplishment in her.

Learners who engaged with feedback usually paid close attention to it, often with anticipation. Lin, for instance, eagerly awaited feedback whenever she submitted her essay, saying, “I wondered when the feedback could be done.” Upon receiving it, she read it carefully. Chen, similarly, paid special attention due to her curiosity about her weaknesses. Rong's attention was particularly heightened by a negative assessment, stating, “The scores of my first essay were not very high, so I paid a lot of attention to the feedback, and I would pay more attention to it in the next writing.” This attention was so intense that she said, “I attached very, very much attention and notice to it, everything, every comment and score, including those punctuation marks.”

What came with such detailed attention was a feeling of joy. Rong found joy in comments that showed the marker's satisfaction, stating, “The marker will say ‘very good statement~,' and I will feel very happy when I see this [~] because it's showing my teacher [marker] is very happy. It's just cute, and I will feel relaxed when I read the feedback.” Rong also enjoyed the relationship with the marker, feeling grateful for the assistance from someone she hadn't known before. Xin echoed this sentiment, saying, “I think all the teachers [markers] are like my friends, like my family.” For Zu and Le, enjoyment was linked to potential improvement. Zu felt happy when feedback pointed out overlooked aspects of her writing. Le appreciated detailed, sentence-by-sentence comments, noting, “Feedback I received before mainly focused on structures. But your feedback provides sentence-by-sentence comments. Therefore, I felt happy about it.”

Learners who engaged with feedback also verified its value by actively using it. Integrating previous comments into future writing tasks was a common practice among learners like Wen. He often made a mental note to implement feedback in his future writing. Wen stated, “Because throughout reading the written qualitative feedback, I have noticed that I like to use long and sophisticated phrases, adding clauses here and there. So perhaps in the future, I am going to try and make my language easier to understand.” He also made efforts to state his opinion clearly at the beginning after receiving feedback criticizing his unclear positions. “After that second essay, which gave me only one point because of my unclear position, I have always tried to include my full opinion in the first paragraph.” This practice led to noticeable improvement in his writing. Xin also dedicated herself to setting goals for future essays, seeking additional resources and lectures on argumentative writing. She said, “I tried my best, and I searched on the internet for information about argumentative writing. And I also found some lectures teaching me how to arrange those structures.”

Though less common, some learners applied written qualitative feedback beyond academic contexts. Wen tried to apply feedback about stating his opinion clearly in speeches and daily life. Yuan attempted to use feedback in her Chinese writing, though this sometimes led to mixed results. She recalled, “The first time I received feedback saying that I failed to include the rebuttal part, I contemplated it, and some chaos happened in later writings. Sometimes I wrote too much rebuttal, and it overwhelmed my central argument.”

While many learners engaged deeply with written qualitative feedback, others chose to ignore it for various reasons. Some learners ignored feedback due to the subjective nature of writing. Yue observed that writing assessments varied widely, making some feedback seem too subjective. “Personally, I don't care much. After all, people hold different opinions, especially in the context of writing as it is highly subjective,” he said. This perspective was influenced by his observation of fellow students' experiences with different standardized tests, where scores varied significantly. Yuan also preferred to follow her own standard, stating, “I don't care much about getting a score of 4 or 5 or 6. For me, writing is really something open.” She emphasized that as long as she met her personal standards, the external evaluations held less significance.

Apart from writing, some learners also found the scoring rubric subjective. Qian, for instance, criticized the rubric's constraints, stating, “Having little writing time with so many inquiries, giving two opinions and one counterargument, it's difficult for us to demonstrate our writing abilities.” Yue also challenged the necessity of providing a counterargument, arguing that he preferred to elaborate on his central argument without always including a counterpoint.

Subjectivity led to selective attention to feedback. Lin, for example, admitted to ignoring feedback on grammar and details unlikely to be used in future essays. She explained, “If you provide feedback on grammar, I might just glance through it without paying too much attention.” Lin's selective approach also extended to comments she deemed irrelevant to her future writing tasks. She noted, “Some details might be ignored because I felt they wouldn't be used in the future. Comments aiming at one specific theme might be useless when it comes to another theme. That's why I ignore it.”

While seeking space for improvement led some learners to engage with feedback, others also ignored due to similar reason. Tong admitted that she paid less attention when her scores were higher than anticipated. “The sores were sometimes even higher than what I expected,” she noted. This attitude suggests that higher-than-expected scores reduced the perceived need for further improvement, leading to a disregard of feedback.

Course settings also influenced engagement with feedback (Brown et al., 2014). Tong mentioned that the non-compulsory nature of the writing program led some learners to ignore feedback. Sheng added that the course not counting toward GPA contributed to this attitude. Tong shared her experience of being “driven” out of a more advanced course and “forced” into this course “for no reason at all,” which affected her motivation to engage with the feedback. Additionally, she noted that her teacher's casual approach to distributing feedback reports without detailed analysis diminished her motivation to learn more. Another factor was the perceived verbosity of some teachers, which affected students' engagement with the feedback. Yue complained about his teacher being “too verbose” and leaving “only 5 min for the final writing task.” This insufficient time allocation for feedback integration made it difficult for students to absorb and apply the comments effectively.

The timing of feedback responses was another critical factor. Duan mentioned that a 2-week gap was long enough for students to forget what they wrote, emphasizing the need for quicker feedback. Yu and Wei similarly noted that delays in feedback made it hard to recall their thought processes during writing. They expressed a desire for more timely feedback, using words like “earlier,” “timelier,” and “more quickly” to describe their expectations.

This study examines the impact of personalized feedback on the argumentative writing development of EFL learners in China. Utilizing an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design, the study involves 107 Chinese high school students who completed three argumentative writing tasks over an academic semester and received personalized feedback in various formats. The findings reveal two primary patterns in students' conceptions of feedback: engaging with positive emotion and active use and ignoring with defensiveness. Quantitative analysis shows that engaging with feedback is positively associated with nuanced position statements in writing, while ignoring feedback is negatively associated with clarity of language. Qualitative insights further illustrate the diverse definitions of feedback among students and their varied engagement with it, highlighting the importance of content-based, timely, and individualized feedback for writing development.

The study finds a significant correlation between students who actively engage with feedback and their ability to produce more nuanced and well-developed position statements in their writing. This correlation is particularly evident in the case of Lin, who emphasized the value of feedback on her logical fallacies, acknowledging that comments on the structure and coherence of her arguments were more beneficial than simple grammatical corrections. Lin's insight aligns with the findings of Hattie and Timperley (2007), who assert that feedback addressing the discrepancy between current performance and desired outcomes is most effective in promoting self-regulation and metacognition. Similarly, Hyland and Hyland (2006) highlight that personalized and content-based feedback significantly enhances the learning process. By focusing on the content and argumentation rather than surface-level errors, the feedback these students received helped them refine their positions and develop more coherent arguments.

Rong's case further illustrates the importance of engaging with content-based feedback. She describes her past experiences with feedback as focusing primarily on her language not conforming to native expressions and her logic being messy. These earlier comments, although negative, shape her attitude toward written qualitative feedback. She approaches the feedback process with a learning mindset, agreeing with and trying to learn from every piece of feedback provided. This positive and open attitude is crucial for effective engagement with feedback (Brown et al., 2014). Rong highlights how her marker's feedback, which often involves changing her wording to make sentences more coherent without using complicated words, greatly influences her writing style. This process of learning from feedback and applying it to improve the coherence and clarity of her arguments aligns with the socioconstructivist view that feedback facilitates cognitive development and knowledge construction through social interaction (Vygotsky, 1978).

Conversely, students who ignore feedback often exhibit less clarity in their writing. The qualitative data reveals that students like Yue and Yuan view writing as a subjective and non-interactive activity, leading to a disregard for feedback. Yue, for instance, expressed that writing assessments varied widely, making some feedback seem too subjective to be useful. This attitude resonates with the findings of Lea and Street (1998), who argue that students who do not perceive writing as an interactive process are less likely to engage with feedback and improve their clarity. Lin's case further illustrates this selective attention to feedback. She admits to ignoring feedback on grammar and details she considers irrelevant to her future essays. Comments on grammatical mistakes, which are identified as less important, are mostly ignored by her. This selective attention prevents students from fully benefiting from feedback and improving their writing clarity. By ignoring feedback, these students miss the iterative process of refining their arguments and improving their clarity through feedback and revision, which is crucial for effective writing development (Ferris and Hedgcock, 1998).

Le's case adds another dimension to understanding how past experiences with feedback shape students' conceptions and engagement. Le highlights her fear of repeating mistakes in using phrases like “argue for” incorrectly. She appreciates the marker's detailed, sentence-by-sentence feedback, which differs from the general comments she normally receives at school. This experience underscores the importance of clear, specific feedback in helping students avoid repeated errors and improve the clarity of their writing.

The study finds that students' definitions of feedback varied widely, reflecting different understandings and values placed on feedback. This diversity can be understood through the lens of educational conceptions, which play a fundamental role in how individuals perceive their learning environment.

While surface-level conceptions focus on the acquisition, storage, reproduction, and use of knowledge, deep-level conceptions center on the construction of meaning and personal change (Entwistle, 1991). Accordingly, some students view feedback primarily as a means of correcting errors. This surface-level conception, focuses on identifying and fixing grammatical mistakes. Students with this view might see feedback as a checklist for improving the technical accuracy of their writing. For example, students like Le value feedback that correct specific language use errors, which helps her avoid repeating mistakes and improve clarity. A more nuanced, deep-level definition of feedback views it as a tool for learning and development. Students like Rong perceive feedback as an opportunity to improve their writing by addressing both strengths and weaknesses in their arguments and presentation. She highlights how the feedback on her language and logic helped her make her sentences more coherent and her arguments more structured. This conception of feedback aligns with the construction of meaning and facilitating personal change, as it encourages students to engage deeply with the feedback and apply it to develop their writing skills comprehensively.

Some students, like Zu, view feedback as part of an interactive dialogue between the writer and the marker. This conception sees feedback as a form of communication that helps clarify misunderstandings and build on ideas. It aligns with the socioconstructivist perspective that emphasizes the social nature of learning and the importance of interaction (Vygotsky, 1978). On the other hand, students who view feedback as an integrated, holistic system supports the cognitive perspective that feedback should promote self-regulation and metacognition (Hattie and Timperley, 2007). Lin's case illustrates this conception, as her definition encompasses error correction, evaluation, learning, and dialogue, providing a comprehensive approach to improving writing skills.

Promoting a broader understanding of feedback—as an interactive and developmental tool—can help students better utilize feedback to improve their writing. Studies have shown that students who view feedback as an opportunity to learn and improve are more likely to engage in self-regulated learning practices (Brown et al., 2014). For example, Lin and Yuan's cases illustrate how feedback that addresses logic and evidence can help students structure their arguments more coherently and provide stronger support for their claims. This aligns with Brown et al. (2016), who find that students' conceptions of feedback are influenced by their prior experiences and the type of feedback they have received. Additionally, encouraging students to adopt a deep-level conception of feedback—as a tool for constructing meaning and facilitating personal change—can also lead to more significant improvements in their writing.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the participants were drawn from a single, homogenous educational context, with all students being native Chinese speakers. This lack of diversity in geographical, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Future research should include participants from varied cultural and linguistic contexts to explore whether the observed patterns hold across diverse educational settings (Banaruee et al., 2023). Second, the study did not account for the potential influence of personality-related factors, such as learning styles and cognitive preferences, which can shape how students perceive and respond to feedback. Future studies could address this gap by examining the role of personality traits in feedback receptivity to better understand individual variations (Banaruee et al., 2017). Third, this study focused primarily on argumentative writing; subsequent research should investigate the impact of feedback on various types of writing, such as creative or technical writing, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how feedback influences writing development. Additionally, with the emergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI), exploring the role of digital feedback tools is important. Examining digital AI-driven feedback and their efficacy compared to traditional methods could offer valuable insights into modern educational practices.

Findings from the current study highlights several pedagogical implications for creating a more individualized and interactive learning environment in EFL writing classrooms. First, it is necessary to provide detailed, content-based written qualitative feedback. Many students valued feedback that addressed specific areas for improvement over simple grammatical corrections. Educators should provide specific, detailed feedback that addresses the deeper aspects of students' writing, such as logic, coherence, and the strength of their arguments. Second, teachers should work on interactive and dialogic written qualitative feedback. Some students, like Zu, viewed feedback as an interactive dialogue that helps clarify misunderstandings and build on ideas. Other students also reported being more motivated by the existence of a real human reader. Educators should foster an environment where feedback is seen as a form of communication, encouraging students to engage deeply with the comments and reflect on how they can improve their writing. This can be achieved by providing opportunities for students to discuss feedback with their teachers, ask questions, and seek clarification. By promoting feedback as a dialogue, educators can help students understand the communicative aspect of writing and improve their clarity and coherence. Third, students value timely and constructive Feedback. Educators should strive to provide feedback as quickly as possible to ensure it is fresh in students' minds and can be effectively applied to their revisions. Some artificial intelligence tools could be integrated to enhance the efficiency of feedback, but “human touch” on the machine feedback is necessary to enhance the “interactiveness” of feedback activities. Finally, teachers should tailor feedback to individual needs and preferences. Students' reflections on past indicate that they learn less from general feedback or sample essays. Many students recall their usual ways of receiving feedback and their longing for more personalized comments. When time and workload allowed, educators should try to consider each student's unique learning style and needs when providing feedback. This personalized approach can help students feel more supported and motivated to engage with the feedback.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee at Fudan University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

TS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WQ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research was supported by the Shanghai Grant of Educational Science [Grant No. C2023155].

We extend our gratitude to the members of the Fudan LEAD Lab, particularly intellectual guidance from Prof. Yongyan Zheng and Prof. Jiming Zhou; collaborative discussion from Weiran Wang, Shuang Wu, Cheng Cheng, Yiqi Shen, Yiqun Ma, Meiying Wu, and Jiafei Yu. We also express our heartfelt thanks to the teachers who supported this project and to all the students who participated.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Banaruee, H., Farsani, D., and Khatin-Zadeh, O. (2022). EFL learners' learning styles and their reading performance. Discov. Psychol. 2:45. doi: 10.1007/s44202-022-00059-x

Banaruee, H., Farsani, D., and Khatin-Zadeh, O. (2023). Culture in english language teaching: a curricular evaluation of english textbooks for foreign language learners. Front. Educ. 8:1012786. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1012786

Banaruee, H., Khoshsima, H., and Askari, A. (2017). Corrective feedback and personality type: a case study of Iranian L2 learners. Glob. J. Educ. Stud. 3, 14–21. doi: 10.5296/gjes.v3i2.11501

Bazerman, C. (2016). “What do sociocultural studies of writing tell us about learning to write,” in Handbook of Writing Research (2nd ed.), Eds. C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, and J. Fitzgerald (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 11–23.

Berzsenyi, C. A. (2001). “Comments to comments: teachers and students in written dialogue about critical revision,” in Composition Studies, 71–92. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43501489

Biancarosa, G., and Snow, C. (2004). Reading Next—A Vision for Action and Research in Middle and High School Literacy: A Report to Carnegie Corporation of New York. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

Bitchener, J., and Storch, N. (2016). Written Corrective Feedback for L2 Development. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, G. T., Peterson, E. R., and Yao, E. S. (2016). Student conceptions of feedback: Impact on self-regulation, self-efficacy, and academic achievement. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 86, 606–629. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12126

Brown, G., Harris, L., and Harnett, J. (2014). Understanding classroom feedback practices: a study of New Zealand student experiences, perceptions, and emotional responses. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 26, 197–218. doi: 10.1007/s11092-013-9187-5

Chan, J. C., and Lam, S. F. (2010). Effects of different evaluative feedback on students' self-efficacy in learning. Int. Sci. 38, 37–58. doi: 10.1007/s11251-008-9077-2

Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Creswell, J. W., Plano Clark, V. L., Gutmann, M. L., and Hanson, W. E. (2003). “Advanced mixed methods research designs,” in Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research, Eds. A. Tashakkori and C. Teddlie (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 209–240.

Deng, Z., Uccelli, P., and Snow, C. (2022). Diversity of advanced sentence structures (DASS) in writing predicts argumentative writing quality and receptive academic language skills of fifth-to-eighth grade students. Assess. Writ. 53:100649. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2022.100649

Entwistle, N. (1991). Approaches to learning and perceptions of the learning environment—introduction to the special issue. High. Educ. 22, 201–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00132287

Evans, C. (2013). Making sense of assessment feedback in higher education. Rev. Educ. Res. 83, 70–120. doi: 10.3102/0034654312474350

Ferris, D. R., and Hedgcock, J. (1998). Teaching ESL Composition: Purpose, Process, and Practice (1st ed.). Mahwah: Routledge.

Ferris, D. R., Pezone, S., Tade, C. R., and Tinti, S. (1997). Teacher commentary on student writing: descriptions and implications. J. Second Lang. Writ. 6, 155–182. doi: 10.1016/S1060-3743(97)90032-1

Graham, S., Hebert, M., and Harris, K. R. (2015). Formative assessment and writing: a meta-analysis. Elem. Sch. J. 115, 523–547. doi: 10.1086/681947

Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., and Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 11, 255–274. doi: 10.3102/01623737011003255

Han, Y., and Hyland, F. (2019). Academic emotions in written corrective feedback situations. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 38, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2018.12.003

Hanson, W. E., Creswell, J. W., Clark, V. L. P., Petska, K. S., and Creswell, J. D. (2005). Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. J. Couns. Psychol. 52, 224–235. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.224

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487

Heap, J. L. (1989). Writing as social action. Theory Pract. 28, 148–153. doi: 10.1080/00405848909543394

Hyland, K., and Hyland, F. (2006). Feedback on second language students' writing. Lang. Teach. 39, 83–101. doi: 10.1017/S0261444806003399

Irving, E., Peterson, E., and Brown, G. T. L. (2021). Student Conceptions of Feedback. Auckland: The University of Auckland.

Johnson, B., and Turner, L. A. (2003). “Data collection strategies in mixed methods research,” in Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research, Eds. A. Tashakkori and C. Teddlie (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 297–319.

Jones, S. M., LaRusso, M., Kim, J., Yeon Kim, H., Selman, R., Uccelli, P., et al. (2019). Experimental effects of word generation on vocabulary, academic language, perspective taking, and reading comprehension in high-poverty schools. J. Res. Educ. Effect. 12, 448–483. doi: 10.1080/19345747.2019.1615155

Jönsson, A., and Panadero, E. (2018). “Facilitating students' active engagement with feedback,” in International Guide to Student Achievement, Eds. J. Hattie and E. Anderman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 321–323. doi: 10.1017/9781316832134.026

Lea, M. R., and Street, B. V. (1998). Student writing in higher education: an academic literacies approach. Stud. High. Educ. 23, 157–172. doi: 10.1080/03075079812331380364

Lee, I. (2024). The future of written corrective feedback research. Pedagogies 19, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/1554480X.2024.2388068

Lipnevich, A. A., Berg, D. A., and Smith, J. K. (2016). “Toward a model of student response to feedback,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment (New York, NY: Routledge), 169–185.

Lipnevich, A. A., and Smith, J. K. (2009). Effects of differential feedback on students' examination performance. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 15, 319–333. doi: 10.1037/a0017841

Lizzio, A., and Wilson, K. (2008). Feedback on assessment: students' perceptions of quality and effectiveness. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 33, 263–275. doi: 10.1080/02602930701292548

Magnifico, A. M. (2010). Writing for whom? cognition, motivation, and a writer's audience. Educ. Psychol. 45, 167–184. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2010.493470

Matsumura, L. C., Patthey-Chavez, G. G., Valdes, R., and Garnier, H. (2002). Teacher feedback, writing assignment quality, and third-grade students' revision in lower- and higher-achieving urban schools. Elem. Sch. J. 103, 3–25. doi: 10.1086/499713

Moser, A. (2020). Written Corrective Feedback: The Role of Learner Engagement. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

National Assessment Governing Board (2010). Writing Framework for the 2011 National Assessment of Educational Progress. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. Available at: https://www.nagb.gov/content/nagb/assets/documents/publications/frameworks/writing/2011-writing-framework.pdf

Nordrum, L., Evans, K., and Gustafsson, M. (2013). Comparing student learning experiences of in-text commentary and rubric-articulated feedback: strategies for formative assessment. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 38, 919–940. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.758229

Patchan, M. M., Charney, D., and Schunn, C. D. (2009). A validation study of students' end comments: comparing comments by students, a writing instructor, and a content instructor. J. Writ. Res. 1, 124–152. doi: 10.17239/jowr-2009.01.02.2

Peterson, E. R., and Irving, S. E. (2008). Secondary school students' conceptions of assessment and feedback. Learn. Instr. 18, 238–250. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.05.001

Phillips Galloway, E., Qin, W., Uccelli, P., and Barr, C. D. (2020). The role of cross-disciplinary academic language skills in disciplinary, source-based writing: investigating the role of core academic language skills in science summarization for middle grade writers. Read Writ. 33, 13–44. doi: 10.1007/s11145-019-09942-x

Pritchard, R. J., and Honeycutt, R. L. (2006). “The process approach to writing instruction: examining its effectiveness,” in Handbook of Writing Research (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 275–290.

Sáiz-Manzanares, M. C., Cuesta Segura, I. I., Alegre Calderón, J. M., and Peñacoba Antona, L. (2017). Effects of different types of rubric-based feedback on learning outcomes. Front. Educ. 2:34. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00034

Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 78, 153–189. doi: 10.3102/0034654307313795

Tashakkori, A., and Teddlie, C. (2003). Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Uttal, D. H., and Doherty, K. O. (2008). “Comprehending and learning from ‘visualizations': a developmental perspective,” in Visualization: Theory and Practice in Science Education (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 53–72.

Van der Kleij, F. M., and Lipnevich, A. A. (2021). Student perceptions of assessment feedback: a critical scoping review and call for research. Educ. Assess. Eval. Acc. 33, 345–373. doi: 10.1007/s11092-020-09331-x

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walker, M. (2009). An investigation into written comments on assignments: do students find them usable? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 34, 67–78. doi: 10.1080/02602930801895752

Wang, E., Matsumura, L. C., and Correnti, R. (2017). Written feedback to support students' higher level thinking about texts in writing. Read. Teach. 71, 101–107. doi: 10.1002/trtr.1584

Wang, X., Zhang, J., and Chen, H. (2024). Traditional EFL writing instruction and the challenges of providing effective feedback. PLoS ONE 39, 1–15.

Weaver, M. (2006). Do students value feedback? student perceptions of tutors' written responses. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 31, 379–394. doi: 10.1080/02602930500353061

Wingate, U. (2012). ‘Argument!' helping students understand what essay writing is about. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 11, 145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2011.11.001

Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Rowntree, J., and Menezes, R. (2016). What do students want most from written feedback information? Distinguishing necessities from luxuries using a budgeting methodology.. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 1237–1253. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1075956

Wright, K. L., Hodges, T. S., Enright, E., and Abbott, J. (2021). The relationship between middle and high school students' motivation to write, value of writing, writer self-beliefs, and writing outcomes. J. Writ. Res. 12, 601–623. doi: 10.17239/jowr-2021.12.03.03

Keywords: written qualitative feedback, conception of feedback, argumentative writing, writing development, English as a Foreign Language (EFL)

Citation: Tao S and Qin W (2025) “Feedback is communication between human beings”: understanding adolescents' conception of written qualitative feedback. Front. Lang. Sci. 4:1453230. doi: 10.3389/flang.2025.1453230

Received: 22 June 2024; Accepted: 24 January 2025;

Published: 11 February 2025.

Edited by:

Liliana Tolchinsky, University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Hassan Banaruee, University of Education Weingarten, GermanyCopyright © 2025 Tao and Qin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenjuan Qin, cWluX3dlbmp1YW5AZnVkYW4uZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.