94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Lang. Sci., 27 May 2024

Sec. Language Processing

Volume 3 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/flang.2024.1388964

This article is part of the Research TopicSpoken Language Processing in Developmental Dyslexia – Beyond PhonologyView all 4 articles

Introduction: Syntactic awareness is the ability to monitor and manipulate word order within sentences. It is unclear whether children with dyslexia have syntactic awareness problems, as there are mixed results in the literature. Dyslexia is typically classified with very poor word and nonword reading and phonological processing problems are often observed in this population. It is conceivable that a phonological deficit could strain memory when performing oral syntactic awareness tasks. Here we examine if syntactic awareness problems are observed in children with dyslexia once phonological processing and memory skills are controlled.

Methods: Real and nonword reading efficiency tests determined reading level. Children with dyslexia (n = 25) were compared to typically developing children (n = 24) matched for age (M = 8;8) and nonverbal abilities. Syntactic awareness was measured with an oral word order correction task (e.g., Is baking Lisa and her son in his room sleeps). Tests of phonological awareness, phonological memory, and verbal working memory were also administered and served as controls.

Results: The dyslexic group performed worse than typically developing readers on syntactic awareness and this group difference persisted once phonological memory and verbal working memory were controlled. However, after controlling for phonological awareness skills, there were no group differences on the syntactic awareness test.

Discussion: The results suggest that phonological awareness problems in particular might be responsible for syntactic awareness difficulties in dyslexia and future studies should control for this. The results are discussed within theoretical frameworks on the nature of oral language deficits in dyslexia.

Syntactic awareness is the ability to reflect on and manipulate word order within sentences (Tunmer et al., 1987). The relation between syntactic awareness and reading comprehension is well-established on both a theoretical (e.g., Perfetti and Stafura, 2014) and empirical level (e.g., Tong et al., 2024). And yet the relevance of syntactic awareness to word reading is less clear, with a mixed set of empirical evidence to date (e.g., Tunmer et al., 1988; Tunmer, 1989; Rego, 1997; Cain, 2007; Deacon and Kieffer, 2018). This question has particular relevance to children with developmental dyslexia, who experience the most entrenched difficulties in word reading. Developmental dyslexia is typically classified by very poor real word and nonword reading skills. While it is a written language disorder, phonological processing is considered the core deficit underlying these difficulties, at least in alphabetic orthographies (Melby-Lervåg et al., 2012; Snowling and Hulme, 2012). It has been argued that nonphonological oral language skills, such as syntactic awareness, are classically intact in children with dyslexia (see Bishop and Snowling, 2004). And yet, whether children with dyslexia in fact have challenges with syntactic awareness is far from clear, with many studies revealing deficits in comparison to age-matched peers (e.g., Abu-Rabia et al., 2003; Rispens and Been, 2007; Casalis et al., 2013; Robertson and Gallant, 2019) while others do not (e.g., Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995). We contribute to this discussion by examining first whether English-speaking children with dyslexia experience problems with syntactic awareness relative to age-matched controls and then whether they can be explained by other factors that could affect performance on this task: phonological processing and working memory. We do so because it is conceivable that phonological processing difficulties could strain memory while processing orally delivered sentences, a common method for syntactic awareness tasks (Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995). Examining whether phonological processing or memory challenges explain differences between children with dyslexia and typical readers could clarify the mixed results and inform theories of developmental reading disorders.

Before considering dyslexia, it is worth noting that the literature on the relation between syntactic awareness and word reading in typically developing children has received mixed results. Cain (2007) examined predictors of word reading accuracy in 7-to-10-year-olds and found that syntactic awareness was a significant predictor even after grammatical knowledge, verbal working memory, and vocabulary were controlled. A similar pattern was revealed by Willows and Ryan (1986) who found syntactic awareness predicted word reading accuracy in 6-to-8-year-old children after controlling for nonverbal IQ, vocabulary, and verbal working memory. However, phonological processing was not controlled in these two studies. Given the strong relationship between phonological processing and word reading (e.g., Hulme et al., 2012), it would be important to examine whether syntactic awareness remained a significant predictor of word reading once phonological processing was controlled. Unlike the other studies, Gottardo et al. (1996) found that syntactic awareness was not a significant predictor of word reading in 8-year-old children after controlling for phonological processing and verbal working memory.

Plaza and Cohen (2003) also controlled for phonological processing when examining the relationship between syntactic awareness and reading. Syntactic awareness was a significant predictor of 6-year-old French speaking children's reading skills even after controlling for phonological processing, memory, and naming speed. However, reading skill was conceptualized as a broad written language composite variable which included word reading, spelling, and reading comprehension. It is unclear if syntactic awareness was a significant predictor of word reading in particular or written language skills in general. Overall, the majority of the papers conducted with typically developing children show there is a connection between syntactic awareness and word reading, but the role of phonological processing as a potential explanation for this relationship needs further investigation. We turn next to studies on dyslexia which have investigated syntactic awareness problems in children with very poor word wording skills that often co-exist with phonological processing problems.

A large set of studies have now demonstrated that children with dyslexia show poor performance on syntactic awareness tasks in comparison to age-matched controls (e.g., Bentin et al., 1990; Abu-Rabia et al., 2003; Leikin and Assayag-Bouskila, 2004; Rispens et al., 2004; Rispens and Been, 2007; Casalis et al., 2013; Chung et al., 2013; Yeung et al., 2014; Delage and Durrleman, 2018; Antón-Méndez et al., 2019; Robertson and Gallant, 2019; but see Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995; Robertson and Joanisse, 2010). For instance, poor performance on spoken sentence comprehension tests has emerged in studies of Hebrew-speaking and French-speaking children with dyslexia (Leikin and Assayag-Bouskila, 2004; Casalis et al., 2013, respectively). Studies employing oral cloze tasks have also revealed challenges with syntax in Arabic and Chinese-speaking dyslexic children (Abu-Rabia et al., 2003; Yeung et al., 2014, respectively). Hebrew and Dutch-speaking children with dyslexia showed grammaticality judgment difficulties in studies conducted by Leikin and Assayag-Bouskila (2004) and Rispens and Been (2007) respectively. Bentin et al. (1990) found English speaking children with severe reading disabilities performed worse than peers on a grammaticality judgment and correction test. While in other cases, syntactic awareness difficulties in children with dyslexia have been more subtle (Robertson and Joanisse, 2010) or nonexistent (e.g., Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995) the majority of the studies that examined syntactic awareness in children with dyslexia have indeed revealed problems compared to age-matched controls.

The bigger question though lies in what poorer performance of children with dyslexia on syntactic awareness tasks reflects. One debate has been whether these are true syntax deficits or whether they stem from known deficits in phonological processing (e.g., Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995), which are widely established to be a causal factor in the word reading difficulties that English-speaking dyslexic readers experience (e.g., Melby-Lervåg et al., 2012; Snowling and Hulme, 2012). Answering this question would inform treatment for dyslexia.

According to the Phonological Deficit Hypothesis, originally coined the Processing Limitation Hypothesis (see Smith et al., 1989), when oral syntactic awareness problems are found in children with dyslexia, they can be explained by a core phonological processing deficit which strains memory (Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995).

And yet, empirical evidence that tests whether syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia stem from phonological deficits is limited. Many studies that found syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia reported concurrent phonological processing deficits (Abu-Rabia et al., 2003; Rispens and Been, 2007; Yeung et al., 2014; Robertson and Gallant, 2019). However, to our knowledge, few studies examined the relationship between phonological processing, syntactic awareness, and word reading in children with dyslexia. Yeung et al. (2014) conducted a longitudinal study with Chinese-speaking children. The dyslexic group performed more poorly than the control group on syntactic awareness in the first grade and these group differences persisted 3 years later. Syntactic awareness in the first grade was a significant predictor of word reading 3 years later even after phonological processing skills were controlled. This finding is not in line with what the Phonological Deficit Hypothesis would predict. However, it is important to consider cross-linguistic differences between alphabetic and morphosyllabic languages. In Yeung et al.'s study, children with dyslexia did not differ from the same-age control group on phonological processing, and phonological processing was not a significant predictor of word reading. Instead, rapid naming, which is characteristically impaired in Chinese-speaking children with dyslexia (Ho, 2004) was poorer in the dyslexic group and was a significant predictor of word reading (Yeung et al., 2014). The pattern might differ in dyslexic children learning to read in alphabetic languages, such as English, given strong connection between phonological processing and reading in these languages (e.g., Melby-Lervåg et al., 2012; Snowling and Hulme, 2012).

Antón-Méndez et al. (2019) examined morphophonological processing in the context of a syntactic awareness task in Spanish-speaking children with dyslexia. Children had to complete a sentence that adhered to subject-verb agreement (e.g., the key to the cabinets___). Performance of the dyslexic group was poor overall compared to the same-age control group, but it was not explained by the presence or absence of morphophonological number marking plural nouns. The authors concluded that the lower scores in the dyslexic group were driven by problems with syntactic processing that is independent of phonological processing. Yet, in the context of alphabetic languages, no study has explored syntactic awareness in children with dyslexia while controlling for phonological processing with a separate measure (e.g., as Yeung et al., 2014, did in Chinese).

The role of verbal working memory in sentence processing has received a good deal of theoretical (e.g., Baddeley, 1992; Just and Carpenter, 1992; Baddeley et al., 2021) and empirical interest (e.g., Gottardo et al., 1996; Montgomery, 2008; Pham and Archibald, 2022). Models of working memory differ with respect to how storage and manipulation of material are organized, but it is clear that verbal working memory involves short-term storage and manipulation of verbal material (e.g., see Baddeley, 1992; Just and Carpenter, 1992; Baddeley et al., 2021). Since syntactic awareness involves the perception and manipulation of, and reflection on word order within sentences, verbal working memory is likely to be engaged in performing a standard syntactic awareness task. For example, in an orally administered word order correction task, children need to briefly store the words in order to manipulate them to arrive at the correct word order. According to the Phonological Deficit Hypothesis, sentence tasks with higher working memory loads should be especially difficult for children with dyslexia since their core phonological processing deficit would strain memory and affect performance (Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995). However, if task demands minimize memory loads, no syntax problems should be observed (Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995). The existing literature which examines this hypothesis comes from studies that examined verbal working memory through task demands (Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995; Robertson and Joanisse, 2010; Antón-Méndez et al., 2019).

Smith et al. (1989) implemented a syntactic awareness task that had minimal working memory loads. In the sentence-picture matching task, children listened to a sentence and selected one of two pictures that matched the sentence. Since children were able to view the pictures while listening, the working memory load was considered minimal. The dyslexic group only showed marginally lower scores than the control group on a sentence-picture matching task. Shankweiler et al. (1995) minimized memory loads even further by designing a task whereby children listened to a sentence while viewing one picture and then decided whether the sentence matched the picture. There were no differences across the dyslexic and control groups in this study. Smith et al. (1989) and Shankweiler et al. (1995) interpret these findings to indicate that children with dyslexia only show syntactic awareness problems if memory processing loads are high. However, neither study compared performance of dyslexic children under high versus low memory loads; the memory load was held constant and considered minimal.

A somewhat similar pattern was found in a dyslexia study that manipulated different verbal working memory loads through task demands (Robertson and Joanisse, 2010). A standard sentence-picture matching task was employed whereby children listened to a sentence while viewing four alternative picture displays and selected the picture that matched the sentence. Working memory was manipulated by varying the delay between the spoken sentence and picture displays. In the low working memory load condition, children heard the sentence and viewed the pictures simultaneously, similar to the low working memory load employed in the Smith et al. (1989) study. No group differences across dyslexic and control groups were found under the low working memory load. Working memory load was increased by presenting the sentence first, followed by a three-second delay before presenting the four picture choices. While performance in both groups declined under the high working memory load, no group differences were found across the dyslexic and control groups. However, under the high working memory load the dyslexic group showed a syntactic complexity effect and performed more poorly on complex versus simple sentences. However, the control group performed equally well across simpler and complex sentences. In summary, no direct differences were found across dyslexic and control groups and the subtle differences in processing complex versus simple sentences in the dyslexic group was only evident under the high memory load.

A follow-up study by Robertson and Gallant (2019) implemented eye tracking to record fixations during online processing of oral sentences in a sentence-picture-matching task. The task itself was similar to the low working memory load employed by Robertson and Joanisse (2010). Like the earlier study, no group differences were found across dyslexia and same-age control groups on accuracy. However, the eye tracking data revealed group differences in online processing. The control group looked longer than the dyslexic group at the target picture while listening to the sentence. In contrast, the dyslexic group looked longer than the control group at the syntactic distractor, likely reflecting a confusion between the object and subject. These eye tracking data show that even under low memory loads the dyslexic group showed subtle syntactic awareness difficulties compared to the control group during online processing. This finding questions the Phonological Deficit Hypothesis as an explanation for syntax problems in children with dyslexia. In summary, when the role of working memory on syntactic awareness in children with dyslexia is measured through task demands, there is no clear pattern; sometimes problems are found even under minimal working memory loads (e.g., Robertson and Gallant, 2019).

The potential effects of working memory on syntactic awareness in children with dyslexia were examined differently in a study by Antón-Méndez et al. (2019). Working memory was manipulated by examining different processing loads in a subject-verb agreement sentence completion task. One way working memory load was manipulated was by modality: both oral and written tasks were administered, and it was argued that the written task would present a higher processing load for children with dyslexia. Secondly, performance was compared across sentences with high and low frequency nouns. Lower frequency nouns may involve a higher processing load while processing subject-verb agreement. However, neither of the syntax task-related working memory load conditions explained the poorer performance in the dyslexic group. To summarize the current literature on the role of phonological processing and working memory on syntactic awareness problems in dyslexia, manipulating task demands alone makes it unclear whether phonological processing or memory or both are related to performance on syntactic awareness tests.

As reviewed above, it is not clear if children with dyslexia have difficulties on syntactic awareness tasks and if they do, it is unknown if these are accounted for by challenges with either phonological processing or working memory. While phonological processing deficits are characteristic in this population, very few studies have examined potential relations among phonological processing and syntactic awareness in children with dyslexia (see Yeung et al., 2014) and none have examined whether syntactic awareness problems in dyslexia might be explained by phonological processing. And given the limited number of studies that manipulated working memory demands and the mixed results on whether this is related to syntactic awareness in children with dyslexia (e.g., Robertson and Joanisse, 2010; Robertson and Gallant, 2019) we take another approach to answering this question by controlling for individual differences in working memory to see if they are related to any observed syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia.

The Phonological Deficit Hypothesis (Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995) speaks to phonological processing deficits that could strain memory. This hypothesis encapsulates multiple processes that are related to syntactic awareness. For instance, phonological awareness is one type of phonological processing; it is the ability to perceive and manipulate phonemes within words and has been well established as an underlying deficit in children with dyslexia, at least in alphabetic languages like English (Melby-Lervåg et al., 2012; Snowling and Hulme, 2012). We examine here whether phonological awareness is responsible for any observed deficits in syntactic awareness, given its status as another metalinguistic skill that involves manipulation of linguistic units. Another aspect of phonological processing is phonological memory, which involves the short-term storage of phonological material (Torgesen, 1996). This skill might also be relevant in the context of syntactic awareness. For instance, the ability to temporarily store words while listening to the sentence unfold over time might be related to performance on a syntactic awareness task (e.g., van Witteloostuijn et al., 2021). Finally, verbal working memory involves both storage and manipulation of verbal material and there is speculation as to its role in syntactic awareness (e.g., Gottardo et al., 1996; Pham and Archibald, 2022). Within studies on syntactic awareness in children with dyslexia, working memory has only been examined through task demands. It would be useful to measure verbal working memory skills outside the context of syntax tests and control for its potential effect on syntactic awareness.

Taking these ideas together, it is conceivable that poor performance on syntactic awareness could result from a problem with phonological awareness, phonological memory, or verbal working memory. By measuring children's phonological awareness, phonological memory, and verbal working memory skills separately and controlling for them when examining syntactic awareness, we can determine whether any of these are contributing to any syntactic awareness problems that are found in children with dyslexia. None of the studies to date have measured and controlled for all three skills when examining syntactic awareness in children with dyslexia.

We implement this approach here. Our first research question addresses whether children with dyslexia have syntactic awareness problems in comparison to age-matched peers. Secondly, we examine if any observed syntactic awareness problems remain once phonological memory and verbal working memory are controlled. Both of these skills involve short-term storage of verbal material, and a second research question will address the extent to which memory plays a role in syntactic awareness skills of children with dyslexia. An assumption of The Phonological Deficit Hypothesis is that phonological processing strains memory (Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995). It is worthwhile to first examine whether memory skills on their own change syntactic awareness in dyslexia. Finally, if syntactic awareness problems persist once both phonological and verbal working memory are controlled, we will examine whether they persist after controlling for phonological awareness in our final research question. In answering these questions, we employ an oral word order correction test to measure syntactic awareness. This is a widely used task that is developmentally appropriate for this age range (e.g., Deacon and Kieffer, 2018) and the use of an oral task avoids confounding performance with word-level reading difficulties (e.g., see Casalis et al., 2013).

The data that we report on comes from a larger study of reading development. A total of 49 participants from the third and fourth grades were recruited from elementary schools in Atlantic Canada. All participants were native speakers of English, and none had hearing difficulties, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or neurological impairments based on parental report. Mean test scores and standard deviations for the two groups described below are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Group mean scores (and standard deviations) on classification measures, covariates, and the syntactic awareness test.

We identified a total of 25 children (15 female; 10 male) for this group. We identified children as part of the dyslexic group based on a mean percentile rank below 20 across the word and nonword reading efficiency measures and a score at the 40th percentile rank or higher on the nonverbal cognition measure described below (Torgesen et al., 2012; Kaufman and Kaufman, 2004; respectively). The mean age was 8 years, 8 months. Seventeen children were in third grade and eight were in fourth grade.

We identified a total of 24 children (11 female; 13 male) for this group. We identified children for this group based on a mean percentile rank between 40 and 70 on word and nonword reading efficiency and a score at the 40th percentile rank or higher on nonverbal cognition (Torgesen et al., 2012; Kaufman and Kaufman, 2004, respectively). We selected children with these scores who were matched on age and nonverbal cognition to the dyslexic group. The mean age was 8 years, 8 months. Eighteen were in third grade and six were in fourth grade.

Word reading efficiency: Form A of the Sight Word Efficiency subtest from the Test of Word Reading Efficiency, 2nd edition (TOWRE-2) was administered to measure word reading efficiency (Torgesen et al., 2012). The subtest included 108 words presented in columns and children were asked to read aloud as many words as they could in 45 seconds. The test-retest reliability reported in the manual is 0.91.

Nonword reading efficiency: Form A of the Phonemic Decoding Efficiency subtest from the TOWRE-2 was given to measure nonword reading efficiency (Torgesen et al., 2012). The subtest included 66 nonwords presented in columns and children were asked to read aloud as many nonwords as they could in 45 seconds. The test-retest reliability reported in the manual is 0.90.

The Matrices subtest from the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, 2nd edition (KBIT-2) was given to measure nonverbal cognition (Kaufman and Kaufman, 2004). Children viewed an array of images and had to pick a target picture that fit with the pattern. The internal reliability reported in the manual for this measure is 0.88.

Phonological awareness: The Elision subtest from the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing was given to measure phonological awareness (Wagner et al., 1999). Children were asked to listen to one word at a time, repeat the word, and then delete a phoneme from the word. There were 20 items. The internal reliability reported in the manual for this measure is 0.89.

Phonological memory: The Nonword Repetition subtest from the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing was given to measure phonological memory (Wagner et al., 1999). Children listened to one pre-recorded nonword at a time and were asked to repeat it. There were 18 items, which increased in syllable length over the test. The internal reliability reported in the manual for this measure is 0.78.

Verbal working memory: Verbal working memory was measured with a backward digit span test. The research assistant dictated a string of digits and asked the child to repeat them in the reverse order. Children completed two practice trials with feedback. The test trials began with two-digit sequences and gradually increased to sequences of eight digits over 14 trials. All trials were administered and there was no stop rule. The child's number of correct responses out of 14 trials was used as their verbal working memory score. Cronbach's alpha for our sample was 0.55.

An oral word order correction task was designed to measure syntactic awareness (see Appendix A in Supplementary material for the full list of items). This task was based on prior sentence correction tasks widely used in the literature (Bowey, 1986; Willows and Ryan, 1986; Siegel and Ryan, 1988; Deacon and Kieffer, 2018). As in these earlier tasks, children listened to pre-recorded sentences with words in a jumbled order and their task was to put the words in the right order. Responses were coded as either correct or incorrect. To receive a correct response, all words had to be put in the right order without changing, adding, or removing any words. As shown in Appendix A in Supplementary material, multiple versions of correct sentences were accepted for each trial as long as the word order and the subject-verb agreement were intact. All sentences consisted of two clauses: one subject-verb clause and one subject-verb-object clause. All words were familiar to children as they were taken from the Children's Printed Word Database (http://www.essex.ac.uk/psychology/cpwd).

Each sentence had either a syntactic or morphosyntactic violation. Syntactic violations had two clauses with an incorrect word order. For example, in the sentence “Is baking Lisa and her son in his room sleeps,” the first clause has an incorrect verb-subject structure, and the second clause has an incorrect subject-object-verb structure. To fix this sentence, children needed to rearrange the words to form the proper subject-verb and subject-verb-object word order by saying, “Lisa is baking and her son sleeps in his room.”

Sentences with morphosyntactic violations had both syntactic and morphological violations. The syntactic violations were the same in nature as the ones described above. The subject-verb and subject-verb-object word order were violated in the two clauses. In addition to the syntactic violation, there was also a morphological violation because the two clauses also had subject-verb agreement errors. For example, in the sentence “Sing Ryan and dances the girls on stage,” the singular subject “Ryan” does not agree with the verb “sing” and the plural subject “girls” does not agree with the verb “dances.” To fix the morphological violation, children needed to exchange the nouns or verbs across the two clauses. Children would fix the syntactic violation by correcting the incorrect verb-subject and verb-subject-object orders to form the proper subject-verb and subject-verb-object order. When correcting both syntactic and morphosyntactic violations, children would say “Ryan dances and the girls sing on stage.”

Originally there were 16 sentences in total and each violation type had eight trials (all different sentences). However, one of the morphosyntactic violation sentences had to be removed from the analyses due to a design error, leaving a total of 15 sentences. All sentences had multiple correct versions and children were given a point for any of the correct versions. The violation types were distributed in a random order but the order of sentences across children was fixed. Practice trials included one example of each violation type and children were given feedback on these before moving on to the test items. The child listened to the prerecorded sentences with headphones. Cronbach's alpha was 0.70.

All procedures were approved by the university and school board ethics. Information letters and consent forms were distributed to children's parents/caregivers and children who returned the forms with signed consent from a parent/caregiver were invited to participate at a time that was convenient with the teacher. Children gave oral consent before starting the tasks. The tests were administered to each child individually and spanned two separate half-hour sessions. The time between the two sessions was approximately 3 months. Children were given a small token of appreciation (e.g., pencil, sticker) at the end of each session.

Table 1 summarizes group means and standard deviations on classification measures, covariates, and the syntactic awareness test. Variables were checked for normality and all had acceptable skewness levels below 1.0. Kurtosis was a bit high for raw phonological awareness scores (−1.53) but improved after a square root transformation (−0.99). The analyses below were run with raw and transformed phonological awareness scores and the outcomes were consistent. All analyses reported below are therefore based on raw scores.

To summarize the raw score group differences on classification measures, as expected, the dyslexic group had lower reading efficiency scores than the TD group on both word and nonword reading tests, t(47) = 9.04, p < 0.001; t(47) = 10.55, p < 0.001, respectively. However, the two groups were similar on nonverbal cognition and age, t(47) = 0.05, p = 0.96; t(47) = 0.33, p = 0.74, respectively. As discussed in the Introduction, phonological awareness, phonological memory, and verbal working memory were treated as covariates since they may influence syntactic awareness. The dyslexic group had lower score than the TD group on phonological awareness and verbal working memory, but there were no group differences on phonological memory, t(47) = 3.24, p < 0.01; t(47) = 2.35, p < 0.05; t(47) = 1.56, p = 0.13, respectively.

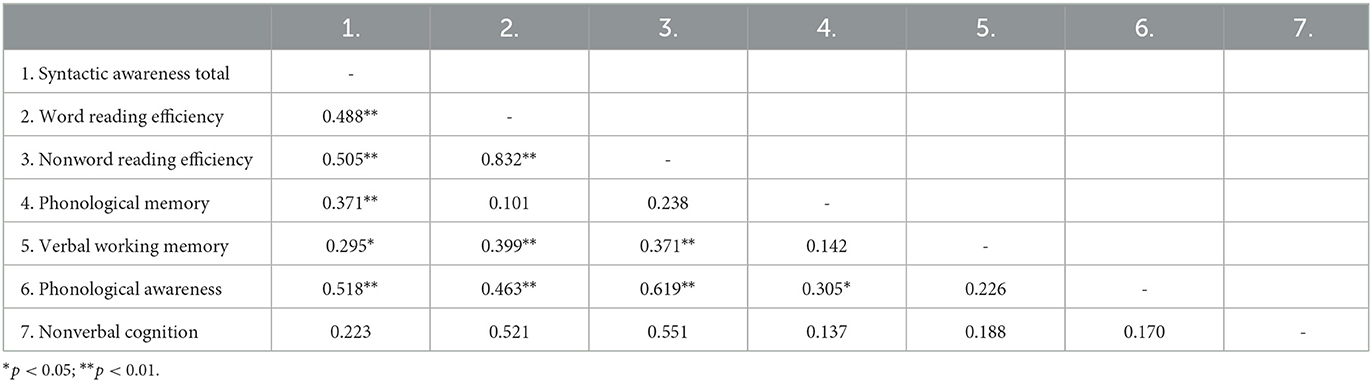

A correlation matrix reporting bivariate Pearson correlation coefficients for the total score (out of 15) on the syntactic awareness task and the other measures is reported in Table 2. A visual inspection of scatterplots indicated the shape of the bivariate correlations were all linear (see Appendix B in Supplementary material). These show that syntactic awareness was significantly correlated with both word and nonword reading (p < 0.01 for both). Syntactic awareness was also correlated with phonological awareness (p < 0.01), phonological memory (p < 0.01), and verbal working memory (p < 0.05), demonstrating the value of these variables as controls.

Table 2. Zero-order bivariate Pearson correlation coefficient matrix of measures of syntactic awareness, reading, and covariates.

We conducted three main analyses to examine our three research questions. Research Question 1 asked whether children with dyslexia have syntactic awareness problems and a univariate ANOVA was conducted to examine it. Following a significant group difference for Research Question 1, a second analysis was conducted. Research Question 2a asked if group differences persisted once the phonological memory and verbal working memory were controlled. This was addressed with a univariate ANCOVA. Finally, following a significant group difference on Research Question 2a, a final analysis was conducted to address whether group differences remained when phonological awareness was controlled. Research Question 2b was addressed with a final univariate ANCOVA.

To address this question, a univariate ANOVA was conducted with scores for the syntactic awareness task. Levene's test of equality of variance across groups was not significant, F(1, 47) = 2.74, p = 0.11. There was a significant main effect of Group, F(1, 47) = 9.20, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.16. The dyslexic group had lower scores than the TD group on the syntactic awareness test. The means from each group are noted in Table 1.

The pattern of results was largely similar when the total syntactic awareness score was broken down by the two violation types in a 2 (Group) by 2 (Sentence Violation Type) mixed ANOVA. Since the number of sentence types across the two violations was slightly uneven, we used the percentages on each one rather than raw scores. In addition to the group effect there was a significant main effect of sentence violation type such that performance overall was better on syntactic items compared to morphosyntactic items F(1, 47) = 9.20, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.16; F(1, 47) = 37.62, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.45, respectively. However, there was no interaction between Group and Sentence Violation Type, F(1, 47) = 0.48, p = 0.49, partial η2 = 0.01.

To address this question, a univariate ANCOVA was conducted. Phonological memory, and verbal working memory were entered as covariates to see if the group effect remained after they were controlled. Levene's test of equality of variance across groups was significant, F(1, 47) = 4.62, p < 0.05, and results should be interpreted with caution. Verbal working memory was not a significant covariate, F(1, 45) = 1.41, p = 0.24, partial η2 = 0.03. However, phonological memory was a significant covariate F(1, 45) = 4.70, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.10. Despite the significance of phonological memory, the group effect remained significant, and the dyslexic group performed worse than the TD group even after phonological memory and verbal working memory were controlled, F(1, 45) = 4.47, p < 05, partial η2 = 0.09. The pattern of results was the same when the total syntactic awareness score was broken down by the two violation types.

To address this question, we added phonological awareness as a third covariate to the univariate ANCOVA described above. Levene's test of equality of variance across groups was not significant, F(1, 47) = 1.14, p = 0.29. Neither phonological memory nor verbal working memory were significant covariates, F(1, 44) = 2.68, p = 0.11, partial η2 = 0.06; F(1, 44) = 1.06, p = 0.31, partial η2 = 0.02, respectively. However, phonological awareness emerged as a significant covariate, F(1, 44) = 6.66, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.13. After controlling for phonological awareness, the earlier group effect was no longer significant, F(1, 44) = 1.42, p = 0.24, partial η2 = 0.03. The pattern of results was the same when the total syntactic awareness score was broken down by the two violation types.

The goal of the current study was to address mixed results in the literature on syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia. We first examined whether syntactic awareness problems were observed across children with dyslexia with an oral word order correction task. Secondly, we examined whether such problems persisted once relevant factors that could contribute to syntactic awareness performance were controlled. The Phonological Deficit Hypothesis claims that a phonological processing deficit could strain memory while performing oral syntactic awareness tasks (Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995). Only a handful of studies have addressed this hypothesis empirically, and most have done so by examining verbal working memory through task demands with mixed results to date (e.g., Shankweiler et al., 1995; Robertson and Joanisse, 2010; Antón-Méndez et al., 2019; Robertson and Gallant, 2019). The current study aimed to clarify which phonological and memory processes in particular might be affecting syntactic awareness in children with dyslexia. Phonological memory, verbal working memory, and phonological awareness are three unique constructs that could potentially explain syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia. We took a novel approach to measure and control for individual differences in these three skills when comparing syntactic awareness across dyslexic and control groups.

To summarize the results, children with dyslexia showed syntactic awareness problems when no variables were controlled. These results concur with many previous studies that have found syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia that did not control for relevant variables that could potentially explain the syntactic awareness problems (Bentin et al., 1990; Abu-Rabia et al., 2003; Leikin and Assayag-Bouskila, 2004; Rispens and Been, 2007; Casalis et al., 2013; Chung et al., 2013; Delage and Durrleman, 2018; Robertson and Gallant, 2019). Our results showed that syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia remained even when phonological memory and verbal working memory were controlled. However, we found no group differences once phonological awareness was controlled. Our results suggest syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia are not likely explained by phonological memory nor by verbal working memory, but they may possibly be explained by phonological awareness problems.

As mentioned in the literature review, there are only two earlier studies that took the role of phonological processing into account when examining the relation between syntactic awareness and word reading in children with dyslexia (Yeung et al., 2014; Antón-Méndez et al., 2019). Antón-Méndez et al. (2019) did not measure phonological processing skills in their sample of children with dyslexia, but they did measure task-related morphophonological processing in the subject-verb agreement sentence completion task. Children with dyslexia did not show particular difficulty with morphophonological number marking plural nouns but they did show poorer performance overall compared to the same-age control group. Antón-Méndez et al. (2019) concluded that children with dyslexia have syntactic awareness problems that are independent of phonological processing.

Unlike the Antón-Méndez et al. (2019) paper, the Yeung et al. (2014) study examined the role of phonological processing by measuring phonological skills outside the context of syntactic awareness tests. They revealed poor syntactic awareness in the dyslexic group compared to the control group in the first grade and these problems persisted 3 years later. The design of the Yeung study was different from ours in that it was longitudinal and sought to reveal whether early syntactic awareness skills could predict later word reading levels in dyslexia. Even when both phonological awareness and phonological memory were controlled, syntactic awareness in the first grade was still a significant predictor of fourth grade word reading skills in Chinese-speaking children with dyslexia (Yeung et al., 2014). The results from the Yeung study do not suggest that syntactic awareness problems in dyslexia are explained by phonological processing. Noting the differences in design, the current study found a different pattern that suggests phonological awareness is an important control when testing syntactic awareness in children with dyslexia. The cross-linguistic differences may explain the mixed results. Chinese has a morphosyllabic orthography and problems that Chinese-speaking children with dyslexia experience are more commonly associated with orthographic processing and rapid naming compared to phonological awareness (Ho, 2004). In alphabetic languages like English, the role of phonological awareness in word reading and word reading difficulties has been well established (e.g., Snowling and Hulme, 2012; Melby-Lervåg et al., 2012). The results of the current study suggest that phonological awareness cannot be ruled out as a potential explanation for syntactic awareness problems, at least in English-speaking children.

On a conceptual level both phonological awareness and phonological memory are considered part of the broad construct of phonological processing and yet they are unique skills (e.g., Wagner et al., 1999). Phonological memory was treated as an additional control in the current study because it is reasonable to think that temporary storage of phonological material would be relevant when storing and manipulating verbal material during a syntactic awareness task. In the literature reviewed, only the Yeung et al. (2014) study controlled for phonological memory when examining whether syntactic awareness was a significant predictor of word reading in children with dyslexia. The earlier study did not detect differences across the dyslexic and control groups on phonological memory and phonological memory was not a significant predictor of syntactic awareness. In the current study, a somewhat similar pattern was found for phonological memory. There were no group differences on this measure. When entered along with verbal working memory, phonological memory was a significant covariate, but group differences on syntactic awareness remained. But when phonological awareness was entered as covariate phonological memory was no longer significant. With respect to the two forms of phonological processing examined, the current results suggest that it is phonological awareness in particular that is likely to be the source of syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia.

In the current study, phonological memory was treated as a separate control from verbal working memory. While both constructs involve storage, verbal working memory carries additional processing demands involving manipulating verbal material. We built on the limited number of earlier studies that examined whether verbal working memory could explain syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia (Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995; Robertson and Joanisse, 2010; Antón-Méndez et al., 2019). Rather than relying on processing demands of syntax tests to examine verbal working memory, the current used a different approach. Individual verbal working memory skills were measured outside the context of a syntactic awareness test and controlled. An earlier study conducted by Delage and Durrleman (2018) found no group differences between the dyslexic and control group on the forward/backward digit span test of verbal working memory. The current study employed only the backward digit span test without testing forward digit span and found the dyslexic group performed more poorly than the TD group. The current study's verbal working memory test also had no stop rule unlike the test employed in the earlier study and this may explain why a difference was observed in the current study. However, despite the group differences on verbal working memory in the current study, even when verbal working memory was controlled it did not emerge as a significant covariate and group differences on the syntactic awareness test remained when verbal working memory and phonological memory were controlled. There is no evidence from the current study's results that working memory or phonological memory explain syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia. Even though verbal working memory was measured differently in the Antón-Méndez et al. (2019) study through task demands on the syntax test, their results also suggest that that syntactic awareness problems in dyslexia are not likely explained by limitations in working memory.

With that said, there are some limitations when interpreting the phonological memory and verbal working memory results. First, the equality of variance assumption across groups was violated in the analysis that only involved the two memory covariates. This limits the interpretation of the significant group differences on the syntactic awareness measure. This was not a concern in the final analysis that included all three covariates; the assumption of equal variance across groups was not violated. In this final analysis the memory covariates yielded null effects; only phonological awareness was a significant covariate. Finally, while there were significant group differences on the verbal working memory test, there was no significant group effect on the phonological memory test. The dyslexic group had numerically lower scores but performance of the TD group on this particular measure was lower than expected and significant group differences were not detected.

A further limitation is that the nonsignificant effects of the verbal working memory and phonological memory covariates cannot be interpreted, but some of these limitations might be addressed in future studies by considering different measures. Verbal working memory tests vary widely (e.g., Daneman and Carpenter, 1980; Willows and Ryan, 1986). The backward digit span test was chosen to provide a measure of working memory that tests fundamental skills that are not reliant on sentence processing. Willows and Ryan (1986) employed the forward and backward digit span test in a study on syntactic awareness in typically developing readers. The current study took a similar approach, but we only used the backward digit span in order to capture both storage and manipulation of verbal material. The manipulation of digits is different from other working memory tests that involve sentence processing (e.g., Daneman and Carpenter, 1980; Gottardo et al., 1996). For example, Gottardo et al. (1996) modified the classic (Daneman and Carpenter, 1980) working memory task in a study with typically developing children. Oral sentences were presented, and children had to answer a yes/no question about each sentence while simultaneously storing the last word in each sentence for later recall. On one hand it may seem appealing to select a working memory test that involves sentences when controlling for working memory during syntactic awareness. However, this type of test was avoided because it could present a confound. The complexity of the linguistic material to process in this type of working memory test might overlap too much with the processing involved in the syntactic awareness measure. It then becomes difficult to dissociate verbal working memory from sentence processing. For this reason, we chose to measure verbal working memory outside the context of sentence processing to have a cleaner measure of the fundamental processing involved in working memory. With that said, it would be interesting to examine whether the pattern of results would change if a working memory test involving sentences was used in a future study.

We chose to measure syntactic awareness with a word order correction test because it requires the manipulation of word order within sentences. Children needed to rearrange the presented words to produce an intact sentence. Word order correction tasks by nature involve a substantive verbal working memory load because children store, manipulate and produce the sentences. Despite the verbal working memory demands that were involved in our syntactic awareness test, verbal working memory skills measured through backward digit span did not explain the group differences between the dyslexic and TD groups. Our syntactic awareness word order correction task involved production of one word at a time and words within the clause need to follow a correct order. In a review paper, Majerus and Cowan (2016) noted studies observed serial order processing problems in dyslexia across a range of stimuli including syllables and words, but none had examined the effects of serial positioning in sentences. The current study did not aim to tease apart serial processing problems from syntactic processing, but this is an interesting area to be investigated in future studies.

Another interesting avenue to pursue in future studies is morphological awareness, the ability to reflect on and manipulate morphemes (Carlisle, 2000) and its relation to syntactic awareness and word reading. Morphological awareness skills outside the context of the syntactic awareness task were not measured in our study, though significant relationships have been found between morphological awareness and word reading (e.g., Kirby and Bowers, 2018; Berthiaume, 2019; Levesque et al., 2021; Rastle, 2022). Future studies could consider adding a morphological awareness test that falls outside the context of sentence processing as a control when examining syntactic awareness in children with dyslexia.

Despite the limitations, the two groups were well defined. Rather than running the risk of inflating potential group differences by employing no upper limit on reading levels in the control group, our control group had normal ranging reading scores. With this in mind, it may be expected that the group differences on syntactic awareness and covariate measures might be less pronounced than they would be in studies with no upper limits on reading levels of control groups. Our groups were also matched on nonverbal cognition and age. We detected group differences on phonological awareness and phonological awareness was a significant covariate in the syntactic awareness group comparisons. Many previous studies revealed syntactic awareness deficits in children with dyslexia, but ours is the first to show that phonological awareness may be driving these problems in English-speaking children. These results suggest that future studies should control for phonological awareness when investigating syntactic awareness in children with dyslexia.

Our study included one control group of same-aged children, but our findings are consistent with the few other studies to implement a reading-level match (Casalis et al., 2013; Chung et al., 2013). As it is well-established, group comparisons of dyslexic to same-age groups means that any differences might be explained by reading skill or learning that occur as a result of reading experience (e.g., Bryant and Goswami, 1986; Goswami and Bryant, 1989). Indeed, in one of the few studies to implement this approach, no group differences in syntactic awareness emerged (e.g., Chung et al., 2013). This was a study of Chinese-speaking adolescents with dyslexia. A similar pattern emerged in a study of French-speaking children with dyslexia when the syntactic task was orally administered (Casalis et al., 2013). We note, however, that this study also identified that the dyslexic group performed more poorly than the reading-level control group on a syntactic task that was given in written format, suggesting that this reading level matching might not eliminate all effects of reading experience. Taken together, there could be advantages to implementing both age-and reading-level matches, along with controls for phonological processing and aspects of memory.

Our results are in line with what the Phonological Deficit Hypothesis would predict (Smith et al., 1989; Shankweiler et al., 1995). When phonological awareness was controlled, the observed syntactic awareness problems in the dyslexia group were no longer significant. It is possible that syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia can be explained by phonological awareness. With respect to oral language deficits in children with dyslexia, a theoretical categorical distinction between phonological and nonphonological skills has been put forward. A two-dimensional model of phonological and nonphonological language skills (including syntax) was proposed by Bishop and Snowling (2004) to explain the language profiles of developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment (now called developmental language disorder, see Bishop, 2017). According to this model, children with dyslexia classically perform poorly on the phonological dimension but within normal ranges on the nonphonological dimension, but children with specific language impairment have deficits on both dimensions (Bishop and Snowling, 2004). Our results suggest there is value in taking a closer look at how the phonological dimension might influence the nonphonological dimension.

While reading comprehension was not the focus of the current study, results from a meta-analysis conducted by MacKay (2023) showed that word reading mediated the relationship between syntactic awareness and reading comprehension. This pattern is in line with the idea that knowledge of grammatical categories and word order help place constraints on word recognition when sounding out novel words (Tunmer, 1989; Rego, 1997). The results from the current study suggest phonological awareness likely plays an important role in the relationship between word reading and syntactic awareness, at least in a population of children with very low word reading scores. Future studies on developmental dyslexia can build upon this work by examining word identification in the setting of syntactic contextual facilitation and the role of phonological awareness. Since our population of interest was developmental dyslexia, we specifically focused on extremely low word and nonword reading and its relation to syntactic awareness. The Reading Systems Framework addresses both word reading and reading comprehension (Perfetti and Stafura, 2014). According to this framework, syntax, phonology, and morphology are part of the Linguistic Knowledge System which helps to drive word reading and reading comprehension. Syntax is also part of the lexicon, which helps to connect word reading and reading comprehension (Perfetti and Stafura, 2014). Future longitudinal studies can investigate word reading, reading comprehension, syntactic awareness, and phonological awareness over time to expand upon our understanding of the role of syntactic awareness in typical and atypical reading development.

Our study contributes to the literature on syntactic awareness challenges in children with dyslexia. We addressed mixed results surrounding the presence of syntactic awareness deficits in this population by taking a novel approach. We not only examined the existence of syntactic awareness problems; we controlled for whether such problems might be accounted for by phonological processing and working memory skills. Our results suggest that phonological awareness in particular is likely driving syntactic awareness problems in children with dyslexia and phonological awareness should be controlled in future studies. We hope our study provides incentive to further investigate the relationship between phonological and nonphonological skills in children with dyslexia to collectively inform theory and provide focus for intervention programs.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because as per university research ethics board regulations, access to the data is restricted to the researchers involved in the study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ZXJpbl9yb2JlcnRzb25AY2J1LmNh.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Cape Breton University Research Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

ER: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. CM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing. SD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research was carried out with support from a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant awarded to ER (# 402,411-2011).

The authors acknowledge the children for their participation and their parents/caregivers, teachers, and principals who facilitated participation. We also thank Mark Vickers, Jillian Polegato, and Sarah Keefe for assistance with data collection.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/flang.2024.1388964/full#supplementary-material

Abu-Rabia, S., Share, D., and Mansour, M. S. (2003). Word recognition and basic cognitive processes among reading-disabled and normal readers in Arabic. Read. Writ. 16, 423–442. doi: 10.1023/A:1024237415143

Antón-Méndez, I., Cuetos, F., and Suárez-Coalla, P. (2019). Independence of syntactic and phonological deficits in dyslexia: A study using the attraction error paradigm. Dyslexia 25, 38–56. doi: 10.1002/dys.1601

Baddeley, A., Hitch, G., and Allen, R. (2021). “A multicomponent model of working memory,” in Working Memory: State of the Science, ed. R. H. Logie, V. Camos, and N. Cowan (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 10–43. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198842286.003.0002

Bentin, S., Deutsch, A., and Liberman, I. Y. (1990). Syntactic competence and reading ability in children. J. Exper. Child Psychol. 49, 147–172. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(90)90053-B

Berthiaume, R. (2019). Encouraging the appropriation of research results on morphological knowledge by school stakeholders. From Read. Writ. Res. Pract. 2019, 125–143. doi: 10.1002/9781119610793.ch8

Bishop, D. V. M. (2017). Why is it so hard to reach agreement on terminology? The case of developmental language disorder (DLD). Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disor. 52, 671–680. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12335

Bishop, D. V. M., and Snowling, M. J. (2004). Developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment: same or different? Psychol. Bull. 130, 858–886. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.858

Bowey, J. A. (1986). Syntactic awareness in relation to reading skill and ongoing reading comprehension monitoring. J. Exper. Child Psychol. 41, 282–299. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(86)90041-X

Bryant, P. E., and Goswami, U. C. (1986). Strengths and weaknesses of the reading level design: a comment on Backman, Mamen and Ferguson. Psychol. Bull. 100, 101–103. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.100.1.101

Cain, K. (2007). Syntactic awareness and reading ability: is there any evidence for a special relationship? Appl. Psycholing. 28, 679–694. doi: 10.1017/S0142716407070361

Carlisle, J. F. (2000). Awareness of the structure and meaning of morphologically complex words: impact on reading. Read. Writ. 12, 169–190. doi: 10.1023/A:1008131926604

Casalis, S., Leuwers, C., and Hilton, H. (2013). Syntactic comprehension in reading and listening: a study with French children with dyslexia. J. Learn. Disab. 46, 210–219. doi: 10.1177/0022219412449423

Chung, K. K. H., Ho, C. S., Chan, D. W., Tsang, S., and Lee, S. (2013). Contributions of syntactic awareness to reading in Chinese-speaking adolescent readers with and without dyslexia. Dyslexia 19, 11–36. doi: 10.1002/dys.1448

Daneman, M., and Carpenter, P. A. (1980). Individual differences in working memory and reading. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 19, 450–466. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5371(80)90312-6

Deacon, S. H., and Kieffer, M. (2018). Understanding how syntactic awareness contributes to reading comprehension: evidence from mediation and longitudinal models. J. Educ. Psychol. 110, 72–86. doi: 10.1037/edu0000198

Delage, H., and Durrleman, S. (2018). Developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment: distinct syntactic profiles? Clin. Ling. Phonet. 32, 758–785. doi: 10.1080/02699206.2018.1437222

Goswami, U., and Bryant, P. (1989). The interpretation of studies using the reading level design. J. Liter. Res. 21, 413–424. doi: 10.1080/10862968909547687

Gottardo, A., Stanovich, K. E., and Siegel, L. S. (1996). The relationships between phonological sensitivity, syntactic processing, and verbal working memory in the reading performance of third-grade children. J. Exper. Child Psychol. 63, 563–582. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1996.0062

Ho, F. C. (2004). “Reading patterns of children with learning difficulties in Hong Kong,” in Hong Kong Special Education Forum, 34–46.

Hulme, C., Bowyer-Crane, C., Carroll, J. M., Duff, F. J., and Snowling, M. J. (2012). The causal role of phoneme awareness and letter-sound knowledge in learning to read: combining intervention studies with mediation analyses. Psychol. Sci. 23, 572–577. doi: 10.1177/0956797611435921

Just, M. A., and Carpenter, P. A. (1992). A capacity theory of comprehension: individual differences in working memory. Psychol. Rev. 99, 122–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.99.1.122

Kaufman, A. S., and Kaufman, N. L. (2004). Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, 2nd ed. London: Pearson. doi: 10.1037/t27706-000

Kirby, J. R., and Bowers, P. N. (2018). “The effects of morphological instruction on vocabulary learning, reading, and spelling,” in Morphological Processing and Literacy Development, eds. R. Berthiaume, D. Daigle, and A. Desrochers (London: Routledge), 217–243. doi: 10.4324/9781315229140-10

Leikin, M., and Assayag-Bouskila, O. (2004). Expression of syntactic complexity in sentence comprehension: a comparison between dyslexic and regular readers. Read. Writ. 17, 801–821. doi: 10.1007/s11145-004-2661-1

Levesque, K. C., Breadmore, H. L., and Deacon, S. H. (2021). How morphology impacts reading and spelling: advancing the role of morphology in models of literacy development. J. Res. Read. 44, 10–26. doi: 10.1111/1467-9817.12313

MacKay, E. (2023). Answering the questions of “which, how, and when”: a comprehensive investigation of the relation between syntactic skills and reading comprehension (Dissertation). Dalhousie University. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10222/82818 (accessed April 14, 2024).

Majerus, S., and Cowan, N. (2016). The nature of verbal short-term impairment in dyslexia: the importance of serial order. Front. Psychol. 7:1522. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01522

Melby-Lervåg, M., Lyster, S.-A. H., and Hulme, C. (2012). Phonological skills and their role in learning to read: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 138, 322–352. doi: 10.1037/a0026744

Montgomery, J. W. (2008). Role of auditory attention in the real-time processing of simple grammar by children with specific language impairment: a preliminary investigation. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disor. 43, 499–527. doi: 10.1080/13682820701736638

Perfetti, C., and Stafura, J. (2014). Word knowledge in a theory of reading comprehension. Sci. Stud. Read. 18, 22–37. doi: 10.1080/10888438.2013.827687

Pham, T., and Archibald, L. M. D. (2022). The role of working memory loads on immediate and long-term sentence recall. Memory. 31, 61–76. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2022.2122999

Plaza, M., and Cohen, H. (2003). The interaction between phonological processing, syntactic awareness, and naming speed in the reading and spelling performance of first-grade children. Brain Cogn. 53, 287–292. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00128-3

Rastle, K. (2022). “Word recognition III: morphological processing,” in The Science of Reading: A Handbook 2nd ed., eds. M. J. Snowling, C. Hulme, and K. Nation (Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell), 102–119. doi: 10.1002/9781119705116.ch5

Rego, L. L. B. (1997). The connection between syntactic awareness and reading: evidence from Portuguese-speaking children taught by a phonic method. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 20, 349–365. doi: 10.1080/016502597385379

Rispens, J., and Been, P. (2007). Subject-verb agreement and phonological processing in developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment (SLI): a closer look. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disor. 42, 293–305. doi: 10.1080/13682820600988777

Rispens, J. E., Roeleven, S., and Koster, C. (2004). Sensitivity to subject-verb agreement in spoken language in children with developmental dyslexia. J. Neuroling. 17, 333–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2003.09.001

Robertson, E. K., and Gallant, J. E. (2019). Eye tracking reveals subtle spoken sentence comprehension problems in children with dyslexia. Lingua 228:102708. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2019.06.009

Robertson, E. K., and Joanisse, M. F. (2010). Spoken sentence comprehension in children with dyslexia and language impairment: the roles of syntax and working memory. Appl. Psycholing. 31, 141–165. doi: 10.1017/S0142716409990208

Shankweiler, D., Crain, S., Katz, L., Fowler, A. E., Liberman, A. M., Brady, S. A., et al. (1995). Cognitive profiles of reading-disabled children: comparison of language skills in phonology, morphology, and syntax. Psychol. Sci. 6, 149–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00324.x

Siegel, L. S., and Ryan, E. B. (1988). Development of grammatical-sensitivity, phonological, and short-term memory skills in normally achieving and learning disabled children. Dev. Psychol. 24, 28–37. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.24.1.28

Smith, S. T., Macaruso, P., Shankweiler, D., and Crain, S. (1989). Syntactic comprehension in young poor readers. Appl. Psycholing. 10, 429–454. doi: 10.1017/S0142716400009012

Snowling, M. J., and Hulme, C. (2012). Interventions for children's language and literacy difficulties. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disor. 47, 27–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-6984.2011.00081.x

Tong, X., Yu, L., and Deacon, S. H. (2024). A meta-analysis of the relation between syntactic skills and reading comprehension: a cross-linguistic and developmental investigation. Rev. Educ. Res. 11:00346543241228185. doi: 10.3102/00346543241228185

Torgesen, J. K. (1996). “A model of memory from an information processing perspective: The special case of phonological memory,” in Attention, Memory, and Executive Function, eds. G.R. Lyon, and N.A. Krasnegor (Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.), 157–184.

Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., and Rashotte, C. A. (2012). Test of Word Reading Efficiency –Second Edition (TOWRE-2). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Tunmer, W. E. (1989). “The role of language-related factors in reading disability,” in Phonology and Reading Disability: Solving the Reading Puzzle, eds. D. Shankweiler and I. Y. Liberman (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press), 91–131.

Tunmer, W. E., Herriman, M., and Nesdale, A. (1988). Metalinguistic abilities and beginning reading. Read. Res. Quart. 23, 134–158. doi: 10.2307/747799

Tunmer, W. E., Nesdale, A. R., and Wright, A. D. (1987). Syntactic awareness and reading acquisition. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 5, 25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-835X.1987.tb01038.x

van Witteloostuijn, M., Boersma, P., Wijnen, F., and Rispens, J. (2021). Grammatical performance in children with dyslexia: the contributions of individual differences in phonological memory and statistical learning. Appl. Psycholing. 42, 791–821. doi: 10.1017/S0142716421000102

Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., and Rashotte, C. A. (1999). Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Willows, D. M., and Ryan, E. B. (1986). The development of grammatical sensitivity and its relationship to early reading achievement. Read. Res. Quart. 21, 253–266. doi: 10.2307/747708

Keywords: dyslexia, syntactic awareness, phonological awareness, phonological memory, verbal working memory

Citation: Robertson EK, Mimeau C and Deacon SH (2024) Do children with developmental dyslexia have syntactic awareness problems once phonological processing and memory are controlled? Front. Lang. Sci. 3:1388964. doi: 10.3389/flang.2024.1388964

Received: 20 February 2024; Accepted: 29 April 2024;

Published: 27 May 2024.

Edited by:

Lucia Colombo, University of Padua, ItalyReviewed by:

Paz Suárez-Coalla, University of Oviedo, SpainCopyright © 2024 Robertson, Mimeau and Deacon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Erin K. Robertson, ZXJpbl9yb2JlcnRzb25AY2J1LmNh

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.