- 1Research Division, Population Council (Nigeria), Abuja, Nigeria

- 2Research Unit, Policy Innovation Centre, Abuja, Nigeria

- 3Leeds Institute of Health Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom

- 4HIV/AIDS Program, Centre For Population Health Initiatives, Lagos, Nigeria

- 5Research Division, Diadem Consults, Abuja, Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria

- 6HIV/AIDS Program, Population Council, New York, NY, United States

- 7Maryland Global Initiatives Corporation (MGIC) an affiliate of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, Abuja, Nigeria

Background: Key populations (KP) are defined groups with an increased risk of HIV due to specific higher risk behaviours. KP who use substances engage in risky behaviors that may play a co-active role in HIV transmission and acquisition in Nigeria. This qualitative study explored the 'syndemics' of substance use, sexual risk behavior, violence and HIV infection among KP who use substances.

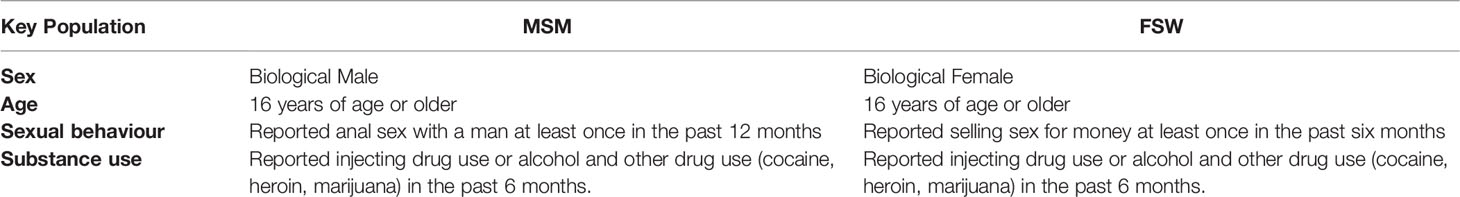

Methods: Nineteen sexually active men who have sex with men [MSM] and 18 female sex workers [FSW] aged 16 years and older who use substances were purposively selected to participate in sixteen in-depth interviews and two focus groups. We utilized a syndemic framework to explore the interaction of socio-economic factors, substance use and high-risk sexual practices. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, organized in NVIVO 11 and analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results: Majority (95%) were non-injection substance users (primarily alcohol and marijuana); a few KP also used cocaine and heroin. Sixty percent of participants were between 16-24 years. Substance use utilities and trajectories were heavily influenced by KP social networks. They used substances as a coping strategy for both physical and emotional issues as well as to enhance sex work and sexual activities. Key HIV/STI risk drivers in the settings of substance use during sexual intercourse that emerged from this study include multiple sexual partnerships, condom-less sex, transactional sex, intergenerational sex, double penetration, rimming, and sexual violence. Poverty and adverse socio-economic conditions were identified as drivers of high-risk sexual practices as higher sexual risks attracted higher financial rewards.

Conclusions and Recommendations: Findings indicate that KP were more inclined to engage in high-risk sexual practices after the use of substances, potentially increasing HIV risk. The syndemic of substance use, high-risk sexual behavior, adverse socio-economic situations, and violence intersect to limit HIV prevention efforts among KP. The behavioural disinhibition effects of substances as well as social and structural drivers should be considered in the design of targeted KP HIV prevention programs. HIV intervention programs in Nigeria may yield better outcomes if they address the nexus of sexual risk behavior and substance use as well as knowledge and appropriate use of HIV prophylaxis.

Introduction

Nigeria has the fourth-largest HIV epidemic in the world and the estimated prevalence among the adult population is 1.4% (approximately 1.8 million people) and an annual infectivity rate of 0.65 among the uninfected populace (1–3). Key Populations (KP) are defined groups with increased HIV risk due to specific higher risk behaviours irrespective of the epidemic type or local context (4). KP include female sex workers (FSW), men who have sex with men (MSM) and people who inject drugs (PWID), transgender and people in prisons and other closed settings (4). Structural factors such as stigma, violence, criminalization and human right violation of KP limit access to health services and increase their vulnerability to HIV (4). Due to limited access to prevention, testing and treatment services, they have a higher risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV (5).

Although they constitute only 3.4% of the general population, FSW, MSM and PWID account for close to 32 percent of new HIV infections in Nigeria (6). These KP are disproportionately affected by HIV/STIs compared to the general population (5, 7, 8). The prevalence of HIV among FSW and MSM is respectively 30 and 26 times higher than the general population in low- and middle-income countries (9). Findings from the 2014 Integrated Biological and Behavioural Sentinel Survey (IBBSS) showed that the overall HIV prevalence among KP was 9.5% (10). HIV prevalence was 22.9% among MSM, 19.4% among brothel-based females who sell sex (BBFWSS) and 8.6% among non-brothel based females who sell sex (NBBFWSS) (10).

In Nigeria, over 40% of the population live in poverty and inequality is high; social amenities for the poor are almost non-existent with women being disproportionately affected due to gendered discrimination (11). Poverty and sex work are intrinsically linked and financial returns underpin the decision to engage in sex work (12). Survival sex which involves exchanging sex for basic subsistence is viewed as a strategy to escape poverty as FSW are marginalized from mainstream employment in some instances due to lack of education, experience and mounting economic pressures (13, 14).

Substance use may be initiated by clients of FSW and may be used to cope with psychological stress or recurring challenges that arise from sex work (15). FSW are highly vulnerable to physical and sexual violence, as laws or policies that protect or empower them are limited and inability to negotiate safe sex as well as substance use contribute to their vulnerability (16, 17). “Sexual violence refers to any sexual act or attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted comments or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship with the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work’’ (18). Substance use heightens the risk of experiencing sexual violence, limits capacity to negotiate safer sex, increases the risk of unprotected sex and multiple sexual partners (19). The intersection of substance use, poverty and gender based violence is associated with an increased risk of HIV transmission (20).

Studies have established a high prevalence of substance use among MSM globally (21–23). In Nigeria, punitive laws that criminalise same-sex relationships, stigma, homophobia and ostracism results in MSM being hidden and this significantly limits their access to HIV services (24, 25). The use of illicit substances such as cocaine, heroin or marijuana is criminalized in Nigeria and users are likely to hide these practices due to stigma (26). Substance use among MSM has been associated with coping with stigma, reducing pain from receptive anal sex, facilitating group sex, transactional sex and multiple partnerships (27, 28). The use of substances during sex affects judgement and increases the likelihood of high-risk sexual practices such as condom-less sex (9, 29, 30). MSM who engaged in transactional sex were more likely to report sexual violence and assault but showed no difference in condom use compared to MSM who did not in a study conducted in Nigeria (24). Compensated sex among MSM was described as embedded within sexual-economic relationships that were not considered entirely transactional.

There are mutually reinforcing conditions, such as poverty, homelessness, family crisis, poor access to healthcare services, that interact synergistically to increase the disease burden among vulnerable populations (31). The synergistic interactions of two or more concurrent epidemics or disease clusters within a population which increases the burden of disease is referred to as a 'syndemic’’ (32, 33). This perspective highlights how synergistic interactions of psychosocial and biological conditions underlie patterns of disease clustering within local political, economic, and social contexts (31, 34).

HIV and malaria are important public health problems in Sub Saharan Africa and their synergistic bidirectional interaction has been documented. Malaria and other neglected tropical diseases (NTD) have a negative impact on HIV prevention, management and prognosis (35–37). Malaria is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Africa; in 2019 Nigeria had the highest burden of malaria cases globally (27%) and accounted for the highest proportion of deaths (23%) (36, 38). HIV infection increases malaria disease burden, severity and rate of transmission; malaria also increases the HIV viral burden, disease progression and risk of transmission (36). Evidence suggest a higher susceptibility to and increased progression of HIV among people with a wide range of bacterial, helminthic and protozoal NTD; clinical improvement is observed after treatment of these infections (35). The geographic distribution of areas of high prevalence for HIV, malaria and endemic infections shows an overlap and a high degree of co-infection (35, 36). Socio-economic factors such as poverty that are linked with the HIV syndemic pathways are also risk factors for NTD, consequently, these interactions highlights the need for integrated approaches that address the holistic needs of KP such as prevention and effective treatment of malaria and other NTDs.

Community-based HIV service delivery strategies are useful in strengthening facility-based models to increase uptake of HIV testing, treatment, and prevention (39–41). In Nigeria, community based clinics have been instituted in addition to KP friendly health facilities to expand access to HIV/STI testing and treatment services for KP. Stigmatization by service providers, fear of police harassment are, however, barriers to access to services (42). Understanding the interaction of substance use, socio-economic factors, sexual risk behavior, and violence is essential to facilitate HIV risk reduction among KP. This study explored the syndemics of substance use, sexual risk behavior, violence, and HIV infection among KP who use substances to understand the synergistic effect on the risk of HIV transmission and implications for HIV prevention among KP.

Methods

Theoretical Framework

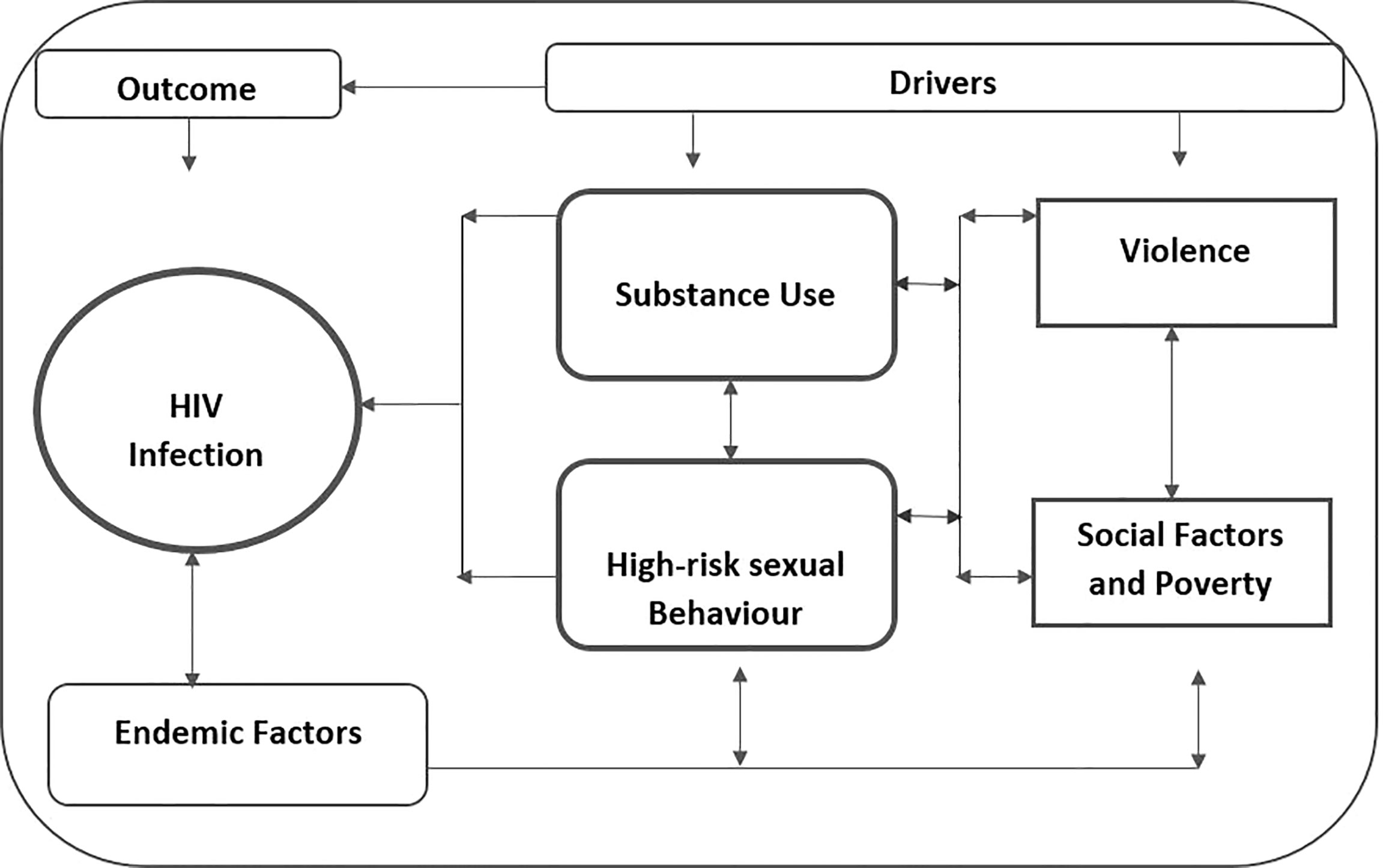

This study utilizes Singer’s syndemic theory to explore the co-occurrence of disease clusters in the setting of harmful social conditions that interact at individual and population levels to exacerbate the negative impact of each disease on health and wellbeing (43). Unlike the traditional biomedical approach that describes diseases as distinct and separate from other diseases and the social context, the syndemic theory utilizes a ‘bio-social’ approach to highlight the important intersections of the social context in the disease trajectory and consequences (32, 44). The syndemic theory highlights the tendency of social and structural drivers to increase health risks and other deleterious outcomes among vulnerable, marginalized populations and focuses attention on key linkages requiring attention (32). The syndemic of substance abuse, violence, and AIDS (SAVA) has been previously described (33). In this study, the concept facilitated an understanding of the interactions of socio-economic factors, substance use, high-risk sexual practices to increase the chances of HIV and STI transmission (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Syndemic framework on the interconnectedness of substance use, high-risk sexual behavior, violence, and socio-economic factors.

Study Design

This qualitative descriptive study was conducted to explore the interactions of socio-economic factors, substance use, violence and high-risk sexual practices to increase the risk of HIV and STI transmission among KP (FSW, MSM) who use substances. Semi-structured in-depth interviews (IDI) and focus group discussions (FGD) were conducted among MSM and FSW aged 16 years and older.

Study Site

The study was conducted in December 2018 in Lagos state, South-West Nigeria. Metropolitan Lagos has a population density of ∼20,000 people per square kilometer, and it is the most populous city in Africa (45). The 2015 population estimate for Lagos state was 24.6 million, and although it is the smallest state by size, it has 27.4% of the urban population of Nigeria (45). Lagos state controls over 60% of Nigeria’s financial and industrial investments, and as a result of increasing rural-urban migration, it is one of the most ethnically diverse states in Nigeria (46). The IDI and FGD were carried out in a KP-friendly and safe outpatient clinic, where FSW, PWID and MSM receive HIV and STIs prevention, care and treatment services.

Study Participants and Data Collection Procedures

Sixteen IDI and two FGD were conducted; participants were recruited either through their community/facility support teams or through the KP-friendly clinic, based on the study eligibility criteria as shown in Table 1. KP visit the clinic to access services mainly through referrals from community outreaches or friends. Potential participants were informed about the study and asked if they were willing to participate. Willing participants were referred to the research team, while KP who did not wish to participate in the study went on to access the services they needed.

Sixteen participants (eight MSM and eight FSW) who met the eligibility criteria for the IDI were interviewed by trained researchers in conducive, private consulting rooms in the KP-friendly clinic. Participants agreed to be audio-recorded and gave written informed consent. They were informed that no personal identifiers will be used throughout the study to ensure the confidentiality of the process. The guides were written in English and pre-tested before use. Each interview lasted about 60 minutes, and the IDI were conducted in English using a semi-structured interview guide that focused on the context of substance use, the utility of substances for sex work and sexual practices, linkages between substance use and high-risk sexual practices, social drivers of substance use and sexual behavior. Some of the IDI questions include ‘please share your experiences on specific encounters that have influenced substance use, please share your views about substance use, sexual risk behavior and decision making, in your opinion how does drug use influence your sexual behavior’?

Two FGD (one FGD among 10 MSM and one FGD among 11 FSW) were conducted with participants who met the eligibility criteria for the study. The FGD sessions lasted 60-90 minutes, and similar consent procedures were followed. Some of the FGD guide questions include ‘what are the reasons for drugs use among KPs, what does use of substances mean to KPs, in what way do you think drug use affect sexual risk taking/patterns, how do KPs who use drugs perceive and manage sexual risk’? Audio recorded data (real-time) was transcribed without personal identifiers and securely transferred to password-protected computers to folders developed by the study team to safely store study data and transcribed immediately after each interview. The recordings were labeled according to each interview category using designated codes. Only authorized members of the study team had access to the storage cabinets or password-protected files.

Ethical Considerations

Ethics and regulatory approvals were obtained. The study was carried out in accordance with the ethics recommendations of the Population Council IRB and the National Health Research Ethics Committee at the National Institute of Medical Research (Protocol No: IRB-19-009). All participants provided written informed consent for participation in the study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Analysis

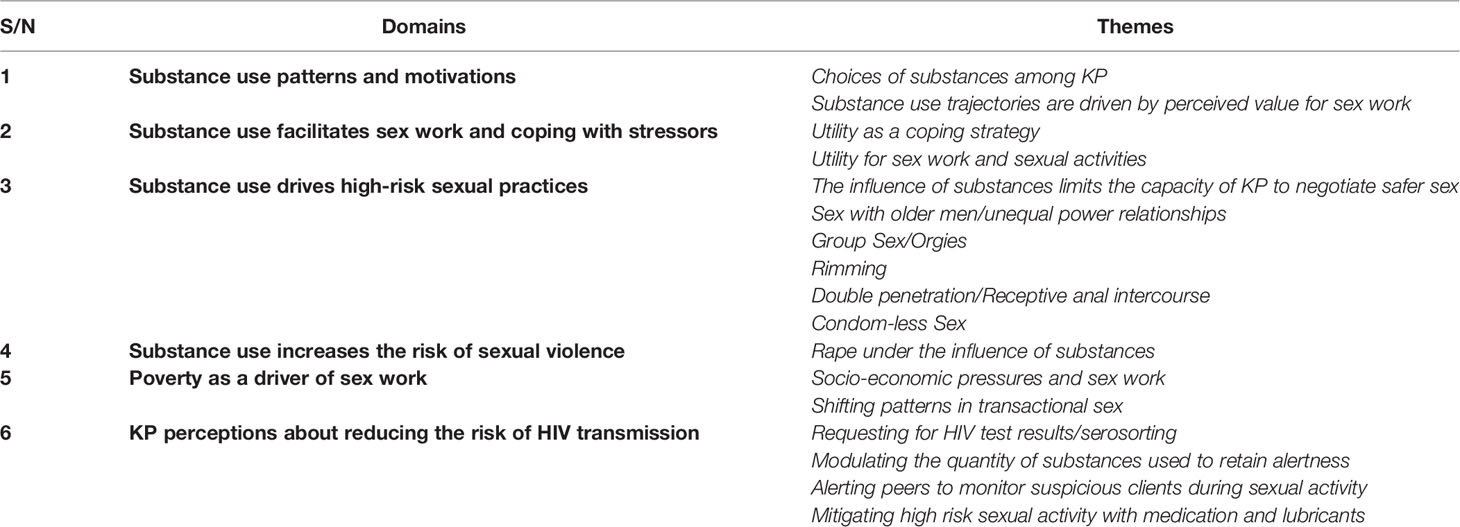

The audio recordings from the IDI and FGD were transcribed verbatim in preparation for analysis, and transcripts were transferred to NVIVO 11 software to organize the data and increase the thoroughness of the analytical process. The analysis team consisting of the lead author and two experienced qualitative researchers read all the transcripts to familiarize themselves with the data and develop the codebook through consensus. Thematic analysis was used as the analytical approach used to explore patterns and data themes. A hybrid of deductive and inductive approaches to thematic analysis and codebook development was applied. The themes were organized using the syndemic framework to explore substance use trajectories and relationship with HIV/STI risk, risk perception, violence and high-risk sexual practices.

Results

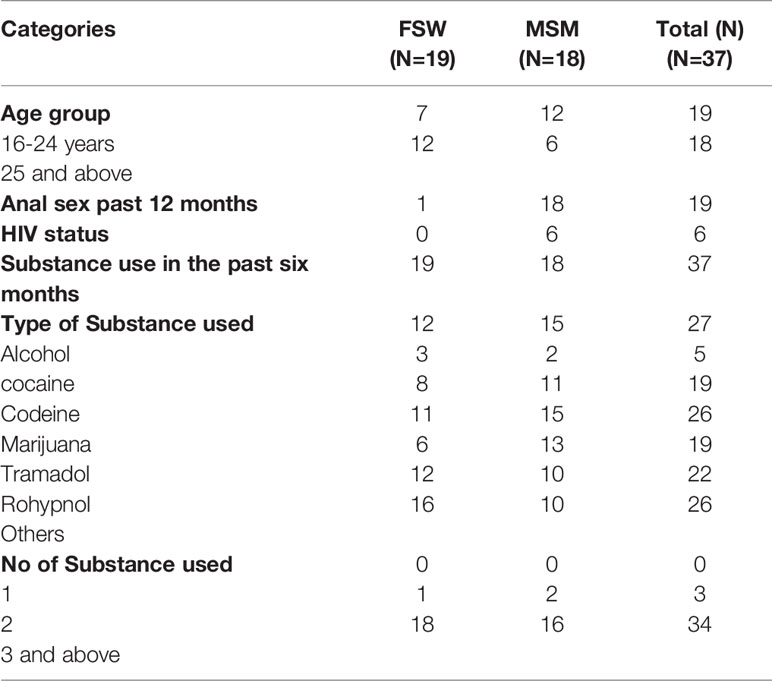

Table 2 shows a summary of the sociodemographic characteristics of participants. A total of 19 FSW and 18 MSM participated in the IDI/FGD. Majority of the participants used three or more substances; alcohol and marijuana were the most commonly used substances. The results are presented according to domains and themes as shown in Table 3.

Substance Use Patterns and Motivations

Choices of Substances Among KP

Participants used multiple substances ranging from alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, tramadol, rohypnol, codeine, and synthetic substances. Marijuana and alcohol were the most commonly used substances. Marijuana use was a precursor to the use of other substances, and majority of participants had used it at some point. The substances were influenced by peer pressure, affordability, availability and other situational factors. Some MSM reported that substance were commonly offered in parties, especially alcohol and shisha (a pipe for smoking marijuana), where these were made available for everyone; FSW mentioned that they used substances to relax after work or to enhance sexual activity. FSW reported using marijuana and alcohol prior to commencing sex work at the brothel. Cocaine was used by snorting, smoking or injecting; cocaine use was, however, considered expensive especially injecting.

Most times I actually use tramadol, and I deal with marijuana…but I actually take marijuana every Sunday with my niggers (guys) at the club then… recreational… occasionally cocaine and… codeine and poppers (akyl nitrite also known as liquid gold).” (Drug User_MSM)

“Before I come out for hustle, I'll enter the bunk first, go and smoke igbo (marijuana) very well, go ogogoro (alcohol) joint, drink before I go come and stand, hustle my money tight.” (Drug User_FSW)

“I do take cocaine and heroin, I do take cocaine, heroin and marijuana and alcohol, that is what I take, and I have been smoking for years.” (Drug User_FSW)

Substance Use Trajectories Are Driven by Perceived Value for Sex Work

Participants' conversations about substance use suggested multiple pathways with three trajectories emerging reflecting social influence, curiosity/boredom and perceived value for enhancing sex work or sexual activities. Individual substance use trajectories for FSW and MSM was however, heavily influenced by substance use transitions among peers or within the social network to which they belonged. This was reflected in some descriptions by MSM about substances considered "good" for them after recommendation by their peers. Marijuana and alcohol were usually viewed as the starting point for substance initiation prior to vertical transitions to cocaine, heroin and horizontal transitions other substances.

“Hmm… taking all these substances is by bad influence… without taking any of these drugs once I have sex with my own system with my own energy [hiss] I do last 15-20 minutes. But the first time I took that tramadol I lasted like more than 20 minutes. So that, that was when I knew that the thing works.” (Drug User_MSM)

“And like me, I was not able to hustle, so I asked one girl, how do they do it and she said if you are not able to hustle (perform sex work), she will introduce something that will make my eye to be clear so that I can hustle well and that is how I take, I started it.” (Drug User_FSW)

" I started using tramadol when I noticed, one of my friends told me about it, that it's so active and I will enjoy the way it works, in my body system I noticed tramadol was not so fine for me, so I went on using marijuana when I noticed marijuana was so good for my body system I started using it, so it went so good for me." (Drug User_MSM)

Progression to other substances such as injecting or multiple substance use was based on multiple considerations, including modulating the effects of substances being used based on the body’s reaction. For example, some FSW mentioned that if the substances they were using hindered their capacity to engage in sex work and negotiate payment with their clients, they switched to alternatives. There was a consensus that KP frequently changed substances to achieve the desired effect or to avoid some undesirable effects.

if I... take bullet (Inhalant) today and I see that bullet did not get me high, maybe tomorrow, if I see any of my colleague taking like captain (Codeine), I'll just say let me sip it o, if I taste it…and yes, this one (makes me) high me then I'll change to it.” (Drug User_FSW)

“Yes, sometimes if I lick rohypnol today and I discovered that it makes me behave abnormal, then it disturbs my hustle, as in…it makes me high more than the way I was expecting… the next day I'll find something that at least it'll just give me a small morale, it will just high me small, that I will still be on my senses to hustle.” (Drug User_FSW)

Substance Use Facilitates Sex Work and Coping With Stressors

Utility as a Coping Strategy

Substance use was considered invaluable for coping with daily life stressors. Specifically, marijuana was viewed as a multipurpose substance that was valuable for feeling invigorated, for stress relief, relaxation, non-violent approaches to dealing with conflict, for letting go of painful situations, boosting self-esteem, increasing alertness, euphoria, improving reasoning and helping them cope with the stigma and shame associated with sex work. Additionally, MSM reported using substances to reduce pain associated with sexual intercourse.

“But for sexing, let’s say I smoke (India Hemp), if I carry a man kpakpakpa [have sex with a client quickly], it will make me agile, collect my money and come out again begin to find my money.” (Drug User_ FSW)

"People often do them for a boost of self-esteem or courage or confidence to get into either the orgy or whatever sex they're trying to get into. So it's either to reduce pain and increase the pleasure, to boost confidence or to make you not think about what you're doing." (Drug User_MSM)

So usually take marijuana just to clear my head… it increases your libido…it is called munchies. When you take it, it makes you hungry… you have these out of the world thoughts… (Drug User_MSM)

For FSW, substance use was critical to ensuring boldness and courage to perform sex work and speak to male clients without feeling intimidated.

“…And to make me high so that I can hustle (perform sex work) very well by then I cannot fear anybody; I can hustle anybody… Like if I don’t use those things, I will not be able to hustle. Those things used to make me strong, and I will not fear anybody, no matter how tall you are. I will not fear you, and it will make me sleep well.” (Drug Use _ FSW)

Utility for Sex Work and Sexual Activities

MSM and FSW considered the use of substances advantageous for enhancing sex work and sexual activities. Many FSW mentioned using substances to get them in the "mood" and enhance their ‘business’. The process of preparing for sex work included using substances to facilitate the entire spectrum of negotiation and client engagement, enhancing client sexual satisfaction, as well as concluding the transaction and getting paid. FSW used substances to increase their sexual appeal and increase performance to maximize the client’s satisfaction for the money they were paid. Some FSW were able to receive higher payments for sex work than initially negotiated when they used substances because they were able to impress their clients. Similarly, some MSM cited how being "high" on substances propelled them to perform "excellently" during sex to guarantee retention of partners and repeat visits. In addition, some MSM reported that substance use was necessary to attain a certain level of sexual performance, prolong sexual satisfaction, increase libido and deepen sexual pleasure.

"I perform excellently when I'm high... Like excellently – like you will surely want to come for your next one. Yes, so… For the fact that I was high, and I could do some things that impressing my partner or impressing the other person or… there's just something you will do that you know you cannot…you can normally not do with your clear eyes" (Drug User_MSM)

“If I take that thing (the substance), I can hustle you, maybe we bargained 2 naira (as fees for sex work) before you leave my room, 4 naira or 5 naira will come out for your pocket” (Drug User_FSW)

“For sex, it (drugs) will make me have strength... maybe if I have sex and I've not used the drugs, I can go two rounds, but if I've used it, I will go like four, five rounds.” (Drug User_MSM)

Substance Use Drives High-Risk Sexual Practices

The Influence of Substances Limits the Capacity of KP to Negotiate Safer Sex

There was a consensus that substance use increases risk-taking and the tendency to participate in high-risk sexual practices. The influence of substances limited the ability of KPs to negotiate safer sex because they were less inhibited when they were ‘high’. An MSM mentioned that the influence of substances ‘makes you not think about what you're doing’. In some instances, participants reported that although they planned to use condoms during sexual intercourse, at the point of meeting the partners, they forgot because they were ‘high’.

“Yea, substance use can... The risk is higher under the influence, some people are able to control themselves while some can't, so I think it's, it's pretty much difficult to actually say” (Drug User_MSM)

“Very risky because at some point you're actually… putting your mouth where you’re not supposed to put them. like the anus I wouldn’t do that with my clear eyes. I wouldn’t rim a guy with my clear eyes, but if I was high and he's the right person...” (Drug User_MSM)

Some participants reported that they were involved in high-risk sexual practices they would not normally engage in if they were not under the influence of substances.

“Ordinarily I wouldn't even think of having a group sex or orgy or anything, but under the influence I know I've done that under the influence before, and I think under the influence, there was a time I did without protection, yea.” (Drug User_MSM)

“When I took someone (a client) inside, I removed condom, then kept it on the bed, then forgot to fix it for the guy… it was after I lay down and then the guy now asked me what happened that I've not put the condom yet o, I said oh! I forgot, and that day I was under the influence of alcohol.” (Drug User_FSW)

“You want to give somebody a blow job and the person has gonorrhoea definitely you are having gonorrhoea of the throat, because you are high at that particular time.” (Drug User_MSM)

Sex With Older Men/Unequal Power Relationships

Some MSM reported that they were forced to have sex with older men. These encounters were usually arranged by middlemen who acted as pimps [men who controlled sex workers and arranged clients for them, taking a proportion of their earnings in return]. They sometimes did not have prior knowledge about the fact that they were being arranged [pimped] for older men. These encounters were difficult for younger MSM, and substance use was considered the only way to get through the experience. Unfortunately, substance use before sex made them more vulnerable to high-risk sexual activities, in addition to the fact that the pimps disempowered them from negotiating safe sex with the older men.

Immediately I saw this person, my heart started beating fast, he had a pot belly and white hair, in fact, the man is just old, so I told him I’m coming I just went down, I did my thing (injected coda) in the rest room – coda (codeine injection). Because generally if you want to have sex with somebody and maybe the person acts like an animal you are high already, you don’t give a fuck about what is there, you just want to do your shit and leave, so it exposes you to more risk getting yourself infected STI and many more.” (Drug User_MSM)

“No, I do not take the risk, I cannot have not more than one man inside. The drugs do not give me the boldness to sleep with two men…Yes, because you took the drug… because the drug can make you to sleep with old” (Drug User _ FSW)

Group Sex/Orgies

Participants cited the influence of substances as an important factor in the decision to participate in orgies due to lowered inhibition. Participation in orgies was associated with high-risk sexual practices such as inconsistent condom use, condom-less sex, and double penetration. FSW reported that in some brothels, there were rules that restricted the entrance of more than one male client or additional females into a room.

"Yes, yes, it makes me take more risk, yes…there was a night, in fact like two occasions, me and my friends like four of us, the same room, with some guys, the same bed you know all these big wide bed… Yea, we have that kind of group sex." (Drug User_FSW)

Yes, drugs are often used at orgies because it lowers your inhibition. It lowers your… reduces your reasoning…. Because at orgies; it’s difficult to maintain condom use. If you're a receptive partner and you have different penetrative partners, even if they're wearing condoms; they're not gonna change condoms for each partner they penetrate. So they're gonna use the same condoms with everybody, so it’s the practice and the drugs lead to unsafe practices. (Drug User_MSM)

“Ok, I met a friend…. he will invite different guys, throw a party in his house…you do your injection stuff and the funniest part of it is that nobody used condom, you can see random guys sleeping with each other… like this one will be with this one for the next five minutes, and with the other one next two minutes...without condom and that was when I found out that I was positive, so it’s not an easy journey, I will never ask anybody to do that shit again, if you tell me you are throwing a house party and you are injecting everybody I won’t come.” (Drug User_MSM)

Rimming

Rimming refers to oro-anal sex in which one person orally (licking, sucking, penetrating) stimulates another’s anus (47). Most MSM perceived rimming as an extreme practice and were uncomfortable about rimming their partners because of the hygiene issues associated with it. For some MSM, they were only able to participate in rimming after using substances like marijuana which clouds their judgement so they don’t have to think about the process. While high on marijuana, they were able to disregard basic hygiene procedures that were usually a critical concern, such as ensuring the anus was clean and free of faeces.

“Do you know what rimming is? Rimming is just like when a guy is licking a girl’s vagina but it’s the other way for MSM; so when a guy is eating your ass. So I could actually do that… when I’m high with marijuana, but with my clear eyes, I can’t do that.” (Drug User_MSM)

Rimming is… it’s like eating the ass – like; you know cunnilingus, just for the ass now, not the vagina. So that’s rimming. So if I'm not high, I would make sure that it is clean and there is a little pungent odour… the sweatiness. But then, the smell of poop or anything like that – you know it’s a turn-off – but with marijuana; it’s not a problem (Drug User_MSM)

“When I'm with my BF and I take marijuana; I could go as far as rimming him…yes; but if I am not with my BF and I'm high, I could go as far as giving you a head – just suck your dick and not rim you…. Yeah I weigh the risks because it’s more normal and usual to give a guy head than to rim you. Rimming is you're going extra.” (Drug User_MSM)

Double Penetration/Receptive Anal Intercourse

MSM perceived double penetration to be high-risk sexual behaviour because of associated risks of tears as well as the tendency to do so without condom and using limited lubrication. However, some MSM participants highlighted how they found themselves being involved in double penetration despite the perceived risks as a result of the influence of substances.

Either going or foregoing protection…or risky behaviour like using less lubrication or wild sex, double penetration… like in orgies; multiple partners… often times some… receptive partners who want to take … bigger penises. So… now that’s a risky behaviour … it could lead to tear [of anal canal] and increases infection because it could lead to tear; that’s higher chance of getting infection. (Drug User_MSM)

“Yeah, yeah it is, but saying it with my clear eyes right now is actually disgusting. I’m feeling disgusted so… If I’m not on marijuana, I don’t think I can do it. I don’t think I can. Okay I actually had 2 dicks (penises) in my ass at the same time.” (Drug User_MSM)

Condom-Less Sex

Considerations about condom use reflected different scenarios relating to the dynamics of condom availability and consistency of use. Even when condoms were available, the decision to use them was driven by the influence of substances. For example, an MSM participant reported “Drugs can actually make you have sex without condoms”.

“When you use drugs… when you are high, and you want to have sex you won't have the time to think of using condom or something just feel like having the pleasure, just enjoy yourself, just feel, just feel free you don't want to know all that.” (Drug User_MSM)

“I actually went out of the box …by inviting a straight guy for my birthday and not knowing his status, not knowing what he has done… at the end, I had sex with him without a condom because I was high. I was on marijuana, and I was on whisky” (Drug User_MSM)

I came there, and the guy was like let’s have sex… that his friend is enjoying me, and me I was high I needed more, so I allowed his friend, and they didn’t use condom… up to date I don’t even know if it’s his friend or him that actually got me infected with gonorrhoea” (Drug User _MSM)

Substance Use Increases the Risk of Sexual Violence

Rape Under the Influence of Substances

There was a consensus among MSM and FSW that the risk of experiencing violence was much higher when they were under the influence of substances. Some MSM acknowledged that their regular partners sometimes forced them to have sex against their wish because they were under the influence of substances and lacked the capacity to resist. Some FSW were forced to have sex without condoms or were raped after they were overpowered by clients irrespective of prior negotiations about condom use. Due to the influence of substances, some FSW acknowledged that they were disinhibited and were unable to fight back when sexually assaulted; others, however, reported that they were able to defend themselves if they were still alert. Some MSM also reported similar narratives about sexual violence in the setting of substance use.

" I was just going with the mindset of having sex with you after getting high with marijuana… you're now telling me, there's marijuana and your friends are around, and I have to sex… and you didn't tell me that at first. We were all still gisting and smoking… not as if you planned it and I didn't know about your friends coming but for the fact that I was high; they took advantage of the person – of my friend, and he didn't like it. And that caused him to bleed for a few weeks." (Drug User _MSM)

“I've heard of a story where a friend actually went out for a birthday party too, and obviously he had a lot to take; so he was raped.” (Drug User_MSM)

“If I (am) high and you want to (trick) me because I am high, me and you will have a problem. We may fight oh! You can't sex me anyhow. One day I was high and carried one man to fuck. He gave… me 1,500 naira and burst the rubber (condom). ‘Stand up now, let me change the rubber he said No!’. He began to press me so that he would go flesh-to-flesh as the rubber had burst...I told him, you cannot do like that…I am not your housewife; I am not your girlfriend. I am a hustler. I pushed him from the bed, he fell, and I stood up because I knew he was ready to carry a pillow to cover my mouth so I would not shout out. (Drug User _ FSW)

In some brothels, clients were not allowed to bring in substances as a measure to protect FSW from being drugged. Brothel owners made these rules and enforced them to protect FSW from clients who planned to drug them and take advantage of them. Some FSW were also robbed by clients because they were under the influence of substances.

"Now, we… hustle, but we did not go to school (we are not educated) but we are wise. When we bring customers, you do not know what he put inside, some use that thing to drug many girls that we have seen. so we avoid this… that is why our director say no one will smoke inside his own hotel. (Drug User _FSW)

Poverty as a Driver of Sex Work

Socio-Economic Pressures and Sex Work

Poverty and economic pressures were described as major drivers of the decision to engage in sex work. Due to limited educational and employment opportunities, young women are forced to sell sex as the most feasible option to earn a living and survive. FSW reported that they were involved in sex work as a strategy for guaranteeing a better future for themselves and their children. Unfortunately, there were additional pressures to engage in unprotected sex because clients paid much higher for FSW who agreed to engage in condom-less sex, thus increasing HIV/STI risk. The process of engaging in sex work sets the scene for exploitation and abuse due to the unequal power relationships between FSW and their clients, creating additional disadvantages and increasing the risk of HIV/STIs, especially in the setting of substance use.

"It is not because of being high that I came here… it is because of my children. So you can’t contact disease because of money, you can't come and kill me. Those children, they will be suffering, no father, no mama. I have a son… then my son was a year, and so I have to look for money to take care of him, and I will not depend on anybody to take care of my baby for me, so that's why I am where I am…." (Drug User _FSW)

“Wow! above, the man was above me, ah, let me say thirty or thirty-something. Yea, but because of the money, I just closed the eyes, do it, then get out with my money.” (Drug User _ FSW)

"…but some people will say because of the 10,000 naira, they will choose to have unprotected sex. They will assume that nothing harmful will happen to them. We see this happening a lot. (Drug User_FSW)

Shifting Patterns in Transactional Sex

Our analysis suggests that the setting for sex work for MSM was different and more sophisticated than FSW; unlike the FSW, who operated from brothels, MSM were connected through gay apps and online platforms. They were profiled online; the price was agreed upon as well as terms of payment prior to meeting in person. Some MSM, however, reported that the approach to profiling for transactional sex sometimes introduced some form of familiarity that resulted in lower risk perception and the inclination to engage in condom-less sex.

“With female sex workers, people tend to use condoms… that I know but often times they don’t. But you know the lines are beginning to be blurred because…prostitution isn’t the way it is anymore. Like now, we have things we call ‘Boss’. You know it’s escort services; yeah but then escort services, the escorts are not meant to have sex with their clients but where a situation whereby you don’t need to go to brothels anymore to… you don’t need to stand on the corner of the road to position yourself and sell sex. You can do that from the comfort of your home from your smartphone! So, you can transact sex…” (Drug User_MSM)

“Okay, Grinder is a gay app... I don’t know if you know Tinder?” They profile with… you try to hook up with them; there's a price. Some can even have their price, and some can just tell you that they're there for sex for pay. Now, that’s prostitution but it just doesn’t happen the way you're used to it. Some do theirs on Instagram anyway… so at the end of the day, we have many people who do have sex with technical prostitutes but just not the kind of prostitutes we’re used to seeing.” (Drug User_MSM)

KP Perceptions About Reducing the Risk of HIV Transmission

FSW and MSM acknowledge the intersection of risks they are faced with when they use substances and engage in high risk sexual behavior. They, however, perceive that they can reduce or minimize the risk by adopting strategies such as serosorting, use of medication/lubricants and controlling the quantity of substances used.

Requesting for HIV Test Results/Serosorting

Some FSW requested for clients to show them their HIV test results before engaging in sexual intercourse. MSM also discussed coming into an agreement with their sexual partners to check their HIV status regularly. For both MSM and FSW, this strategy was considered particularly useful when negotiating condom-less sex. They perceived that if the client’s test result was negative, it was safe to engage in sex without condom because the client did not seem to pose any significant risk to them. In addition to requesting for results, they expected clients to disclose any history of STIs to them during conversations that occur prior to sex. In some instances, FSW used the female condom as an additional layer of protection, while MSM mentioned having their HIV-negative partners use PEP after condom-less sex.

“How can somebody tell you not to use a condom without knowing the person, and he did not show you the result of test? … For a responsible man who knows he is okay… before you fuck without condom, you must do HIV test. But if you want to know this is a very stupid person, if he is your friend for one week or two weeks if he wants to have sex without condom, he will not talk anything about test…he will ask you to have sex like that no problem.” (Drug User_FSW)

“In one of my past relationships, it got to a point we had to go to the hospital to know our status, and he was cool with me being positive…. and fine, we were still having sex but with condoms. And with days… it’s not like we always have sex with condoms, but the days we don’t have sex with condoms, he always goes to the clinic to take PEP just for him to be safe.” (Drug User_MSM)

“He will bring the result now. Somebody cannot just tell you that he is okay… without showing you the result. You will see the result, see the date when he did it, see the hour and know whether it is true. But if you want to confirm o, you can tell him say let us go together then you do your own, I do my own. You will hear about my own, I will hear about your own.” (Drug User_FSW)

Modulating the Quantity of Substances Used to Retain Alertness

FSW reported modulating the quantity of substances used to ensure they were alert enough to enforce condom use with clients. Through practice, they felt that they were able to determine the quantity of alcohol or marijuana needed to achieve optimal functioning without compromising their judgement or engaging in high-risk sexual practices.

“No matter how high I am; I cannot forget condom because I use to gauge my high…. If I know that today, I want to hustle. God gives me money; okay, I want to take (4) wraps of igbo. I know that, that (4) wraps of igbo will not make me to be carried away and it will carry me till when I want to sleep so I will take it. So no matter how high I am, I can’t forget condom.” (Drug User_FSW)

“That's why I said when whenever I'm drinking I always make sure that even though as I'm being high, there's a level, there's a level that I'll still be under my control, I'll have a sense of reasoning, I'll still have at least a little sense, a little control in me.” (Drug User_FSW)

“When my customer, my business partner comes inside, the first thing is, even though I am on drugs, the drug will make me locate my condom, when he pays me, I bring my condom out, the drug can make me remember, I will use my condom.” (Drug User_FSW)

Alerting Peers to Monitor Suspicious Clients During Sexual Activity

FSW who operated in brothels mentioned that whenever they met up with clients under the influence of substances, they alerted their peers about their activities to ensure their peers looked out for them and intervened if there was a problem. This protection mechanism was considered crucial for FSW because they considered themselves at risk of being overpowered by male clients, assaulted, and forced to have sex without a condom.

"Yes, as they monitor you, When I don’t trust a client I am with… if I want to enter, ( I will alert my friend) my dear, I want to enter with this man o! Please after some time come and check my room (Drug User _FSW)

…the person doesn’t know you, so when you are meeting that very person, you have to use your brain. Oga I will fuck (have sex with you) you well o, is it my leg you want me to open or my back…? If you are discussing with a man with some shame, he will say ‘my dear, let us negotiate inside’ but if it is an agbero (tout) like me, we stand outside, discuss everything outside. You will make eye contact (with your friend), and you will ask your friend, ‘watch that man for me’…. (Drug User _FSW)

“Yeah. If someone offers you something, make sure to know what’s in the cup before you take it or whatever you're taking before you take it, eh… take in bits and always have someone… if you go to somewhere you're not familiar; have someone somewhere to check in from time to time to know your situation, so if things start to deteriorate; there's always someone to come get you.” (Drug User_MSM)

Mitigating High Risk Sexual Activity With Medication and Lubricants

There was a consensus among FSW that condom tears were fairly common occurrences during sexual intercourse with clients. While some managed this risk by wearing female condoms as an additional layer of protection, others ensured that their condoms were well lubricated to avoid tearing. In addition, one MSM reported using Septrin (an antibiotic medication) to manage the risk of having sex without a condom.

“Excuse me, let me tell you, at times mistakes happen during this fuck of a thing and the condom can burst.” (Drug User_FSW)

"There are some types of customers that you will carry…they will be doing rough sex so that the condom will burst… So if I pour the oil on the condom, it will not burst because the oil will make everywhere smooth. But if I do not put that oil, the condom will burst, and that is why I don’t lack the oil in my room” (Drug User_FSW)

"I had a medicine in my house, its septrine, so anytime I am being exposed like, having sex without condom, that's the only thing I take." (Drug User _MSM)

Discussion

This study explored the syndemic of substance use, sexual risk behavior, and violence in the context of poverty and social drivers of HIV risk in Nigeria. Findings from this study show that substance use utilities and trajectories that drive continued use were heavily influenced by social networks and the perceived value as a coping strategy as well as enhancing sexual activities. In line with the syndemic theory, the use of substances increased risk-taking and the tendency to participate in high-risk sexual practices in the setting of social drivers of HIV/STIs risk and sexual violence. Sex workers are vulnerable to victimization from clients and brothel owners, and they frequently experience violence and psychological distress in the setting of substance use, increasing the risk of HIV transmission and compounding the consequences of the disease (48). Key HIV/STI risk drivers in substance use settings during sexual intercourse that emerged from this study included multiple sexual partnerships, condom-less sex, transactional sex, intergenerational sex, double penetration, rimming, sexual violence. These findings are consistent with other studies that have documented the coexistence of substance use and sexual risk (28, 49–52).

As highlighted in this study, the multiple trajectories to sustained use of substances result in dynamic situations that set the scene for polysubstance use. The tendency for MSM and FSW to learn and adapt to new substances as they search for an enhanced effect or to modulate side effects reinforces the pathways that sustain use. This adaptive approach to modulating consequences of substance use and switching substances in the process appeared to be positively reinforcing as opposed to deterring use altogether. Although the value of substances had a prominent sexual focus, of note is the fact that it was also linked to social aspects of everyday life such as parties and daily coping with life stressors. The tendency to use substances in anticipation of specific sexual experiences has also been documented in another study (52). A multipronged strategy is, however, needed to develop integrated interventions that address the nexus of substance utilities and social factors that sustain use.

Although substance use was considered valuable by MSM and FSW across the entire spectrum for enhancing sex work and sexual activities, it also predisposed them to be vulnerable to high-risk sexual practices and violence. As highlighted in the syndemic theory, poverty as well as limited educational and employment opportunities played a role in predisposing KP to these HIV risk drivers (33). The synergistic effect of these syndemic factors is illustrated by considerations among FSW to engage in high-risk sexual practices such as condom-less sex for a higher fee. These findings were also reinforced among MSM recruited through escort services or gay apps and had a lower HIV risk perception about the prospective clients due to preliminary profiling that gave them a sense of safety-driven by the prospects of higher returns.

Across this study, there was a clear consensus that risk-taking during sexual intercourse was influenced by prior substance use. The influence of substances limited the capacity of KP to negotiate safer sex or protect themselves from violence as they were no longer in control of the process; this implies that KP do not make informed decisions about risk taking in such situations. This is in contrast to other situations when they rationalize the utility of substances for sex work or sexual activities. Substance use is associated with risky sexual practices such as limited condom use with multiple sexual partners (53). The risk of acquiring HIV and rectal STIs is higher among MSM who participate in condom-less receptive anal intercourse than those who only participate in condom-less insertive anal intercourse (30). Findings from this study showed that these sexual practices were common among MSM participants after substance use and as a result of power relations that occur when they engage in sexual intercourse with older men. An additional issue for consideration is the evidence that suggests that MSM who are receptive partners give up the responsibility of initiating condom use to the partner on top (30). Due to the spontaneous nature of sexual encounters following substance use, there is little or no time for discussions about condom use and sexual positioning. Substance use also increases the tendency for unrealistic and poor decision-making about sexual partners, practices, risk-taking that favour immediate gratification over long-term consequences (52). Findings from this study reflect this as MSM who were not comfortable with rimming or group sex disregarded safety considerations and risk implications and they did so after substance use.

Perceptions about risk reduction strategies reflected misconceptions about risk-taking and HIV prevention. The adoption of sero-adaptive strategies such as serosorting was central to some participants’ sexual risk decision-making. Serosorting is a practice in which decision-making about partner selection and sexual practices is based on assumed or reported HIV serostatus with a view to avoiding transmission and forgoing the use of condoms (54, 55). Findings from this study show that MSM and FSW considered serosorting as an important risk reduction strategy in the negotiation of condom-less sex. Unfortunately, this approach may be problematic because partners may not know their true HIV status, may falsify test results because they are HIV positive, and choose to hide their status. Recently infected partners may also have a false negative antibody test result and inadvertently disclose themselves as HIV negative (54, 56). These issues may result in KP engaging in high-risk sexual practices on the basis of erroneous information or ‘sero-guessing’ based assumptions about their partner's HIV status (57).

Findings from other studies suggest that the practice of serosorting may inadvertently increase the risk of HIV transmission (54, 56, 58). A systematic review by the WHO showed that in comparison with consistent condom use, serosorting was associated with 79% increase in HIV transmission and 61% increase in STIs (59). HIV prevention programs for KP should incorporate discussions about the limitations of serosorting as an HIV risk reduction strategy because they may develop a false sense of security and forgo condom use based on potentially inaccurate information. Although some FSW and MSM disclosed additional layers of protection such as female condom and PEP after sexual intercourse with HIV positive partners, these may not be consistently used. The context and practice of serosorting among MSM in Nigeria needs further evaluation. While KP described other risk reduction strategies such modulating the quantity of substance used and alerting peers to monitor suspicious clients and use of lubricants, these measures are subjective and cannot substitute established safer sex measures.

The public health implications of HIV co-infection with malaria and other neglected tropical diseases reinforces the need to address syndemic factors that increase the risk of HIV infection among KP. KP programs should incorporate service provider trainings and referral guidelines for substance use prevention and management to facilitate access to therapy for KP in need. KP community support groups should incorporate discussion sessions on HIV risk reduction strategies that address misconceptions and increase awareness about the use of PrEP; these sessions can be embedded into regular facility visits and virtual KP engagement platforms. The understanding of syndemics is important for policymakers and implementers to explore critical points for HIV prevention strategies. These strategies must incorporate multilevel interventions to address the intersections of poverty, substance use, sexual risk behavior, and violence as well as the nexus of malaria and other NTDs.

Limitations

There are limitations to the conduct of this study. A small sample was used in this qualitative study among KP who use substances and therefore is not representative across KP that use diverse combination of substances. Recruitment of participants through health facilities and health outreach centers may limit the diversity of KP interviewed. The information obtained from this study was self-reported (except HIV status) and there may be nuanced challenges with recall or social desirability in the description of events. This study also did not exhaustively explore issues relating to the effect of specific substances. Despite these limitations, the study provides useful information that can guide the development of adaptive strategies for HIV prevention among KP.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that there are important linkages between substance use, sexual behavior, violence, and social drivers of HIV risk. The findings from this study highlight important considerations for HIV prevention strategies among KP that incorporate specific harm reduction strategies for substance use as well as addressing wider issues around stigma and coping. Prevention approaches need to consider tailoring more effective interventions for MSM and FSW.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included inthe article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can bedirected to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Population Council IRB and the National Health Research Ethics Committee (local ethics committee) at the National Institute of Medical Research, Nigeria. All study participants provided written informed consent for participation in the study.

Author Contributions

OD, GE, WT and SA conceptualized the study. OD, MA, AA and AO analyzed the data. OD, led the writing of this paper with contributions from MA, AO, AA, BE, ES. All authors reviewed, edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Elton John AIDS Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank dedicated staff of the Community Health Center especially Chiedu Ifekandu, Ebunoluwa Taiwo and Lanre Osakue for overseeing the recruitment of participants and implementation of the research. We also thank the study participants without whom this study would not have been possible.

References

1. AVERT. HIV and AIDS in Nigeria (2019). Available at: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/nigeria.

2. Qiao S, Zhang Y, Li X, Menon JA. Facilitators and Barriers for HIV-Testing in Zambia: A Systematic Review of Multi-Level Factors. PLoS One (2018) 13(2):e0192327–e0192327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192327

3. Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) Nigeria. Nigeria HIV/AIDS Indicator and Impact Survey (NAIIS) 2018. In: Technical Report Nigeria:FMOH (2019). p. 297. Available at: http://ciheb.org/media/SOM/Microsites/CIHEB/documents/NAIIS-Report-2018.pdf.

4. Organization WH. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations–2016 Update. Geneva: WHO (2019).

5. Gilbert L, Anita R, Denise H, Jamila S, Assel T, Gail W, et al. Targeting the SAVA (Substance Abuse, Violence, and AIDS) Syndemic Among Women and Girls: A Global Review of Epidemiology and Integrated Interventions. JAIDS (2015) 69(Suppl 2):S118–127. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000626

6. WHO. Global Health Sector Strategy on HIV 2016-2021. In: World Health Organization ( Geneva: WHO) (2016). p. 60.

7. Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, Mendenhall E. Syndemics and the Biosocial Conception of Health. Lancet (2017) 389:941–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30003-X

8. Beyrer C, Sullivan P, Sanchez J. The Increase in Global HIV Epidemics in MSM. AIDS (2013) 27:2665–78. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000432449.30239.fe

9. Sabin K, Zhao J, Garcia CJM, Sheng Y, Arias GS, Reinisch A, et al. Availability and Quality of Size Estimations of Female Sex Workers, Men Who Have Sex With Men, People Who Inject Drugs and Transgender Women in Low and Middle- Income Countries. PLoS One (2016) 11(5):e0155150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155150

10. FMOH. Integrated Biological and Behavioural Surveillance Survey (IBBSS), Vol. 2015 (Nigeria:Federal Ministry of Health). (2014).

11. National Bureau of Statistic (NBS). 2019 Poverty and Inequality in Nigeria (2019). Available at: https://nigerianstat.gov.ng/download/1092.

12. Monroe J. Women in Street Prostitution: The Result of Poverty and the Brunt of Inequity. J Poverty (2005) 9(3):69–88. doi: 10.1300/J134v09n03_04

13. Onyango MA, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Agyarko-Poku T, Asafo MK, Sylvester J, Wondergem P, et al. “It’s All About Making a Life”: Poverty, HIV, Violence, and Other Vulnerabilities Faced by Young Female Sex Workers in Kumasi, Ghana. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (2015) 68:S131–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000455

14. Van Blerk L. Poverty, Migration and Sex Work: Youth Transitions in Ethiopia. Area (2008) 40(2):245–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2008.00799.x

15. Strathdee SA, West BS, Reed E, Moazen B, Azim T, Dolan K. Substance Use and HIV Among Female Sex Workers and Female Prisoners: Risk Environments and Implications for Prevention, Treatment, and Policies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (2015) 69 Suppl 2(0 1):S110–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000624

16. Poteat T, Reisner SL, Radix A. HIV Epidemics Among Transgender Women. Curr Opin HIV AIDS (2014) 9(2):168–73. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000030

17. Sevelius JM, Keatley J, Gutierrez-Mock L. HIV/AIDS Programming in the United States: Considerations Affecting Transgender Women and Girls. Womens Heal Issues (2011) 21(6 Suppl):S278–82. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.08.001

18. World Health Organization (WHO). Sexual Violence . Available at: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/global_campaign/en/chap6.pdf.

19. Ditmore MH. When Sex Work and Drug Use Overlap: Considerations for Advocacy and Practice. London, UK: Harm Reduct Int (2013).

20. Shannon K, Bright V, Allinott S, Alexson D, Gibson K, Tyndall MW, et al. Community-Based HIV Prevention Research Among Substance-Using Women in Survival Sex Work: The Maka Project Partnership. Harm Reduct J (2007) 4(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-4-20

21. Colfax GN, Mansergh G, Guzman R. Drug Use and Sexual Risk Behavior Among Gay and Bisexual Men Who Attend Circuit Parties: A Venue-Based Comparison. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (2001) 28:373–9. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200112010-00011

22. Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM. HIV Prevalence and Associated Risks in Young Men Who Have Sex With Men. Young Men’s Surv Study Group JAMA (2000) 284:198–204. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.198

23. Stall R, Purcell DW. Intertwining Epidemics: A Review of Research on Substance Use Among Men Who Have Sex With Men and its Connection to the AIDS Epidemic. AIDS Behav (2000) 4(2):181–92. doi: 10.1023/A:1009516608672

24. Crowell TA, Keshinro B, Baral SD, Schwartz SR, Stahlman S, Nowak RG, et al. Stigma, Access to Healthcare, and HIV Risks Among Men Who Sell Sex to Men in Nigeria. J Int AIDS Soc (2017) 20(1):21489. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.01.21489

25. Dirisu O, Sekoni A, Vu L, Adebajo S, Njab J, Shoyemi E, et al. “I Will Welcome This One 101%, I Will So Embrace it”: A Qualitative Exploration of the Feasibility and Acceptability of HIV Self-Testing Among Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM) in Lagos, Nigeria. Health Educ Res (2020) 35(6):524–37. doi: 10.1093/her/cyaa028

26. NDLEA. National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA), Vol. 2015. (2015) Available at https://ndlea.gov.ng/files/2015%20annual%20report.pd(NDLEA:Nigeria).

27. Sandfort TGM, Knox JR, Alcala C, El-Bassel N, Kuo I, Smith LR. Substance Use and HIV Risk Among Men Who Have Sex With Men in Africa: A Systematic Review. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (2017) 76(2):e34–46. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001462

28. Tan RKJ, Wong CM, Chen MI-C, Chan YY, Bin Ibrahim MA, Lim OZ, et al. Chemsex Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex With Men in Singapore and the Challenges Ahead: A Qualitative Study. Int J Drug Policy (2018) 61:31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.10.002

29. Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance Use and Risky Sexual Behavior for Exposure to HIV. Issues Methodol Interpret Prev Am Psychol (1993) 48(10):1035–45. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035

30. Dangerfield 2DT, Ober AJ, Smith LR, Shoptaw S, Bluthenthal RN. Exploring and Adapting a Conceptual Model of Sexual Positioning Practices and Sexual Risk Among HIV-Negative Black Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Sex Res (2018) 55(8):1022–32. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1433287

31. Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and Public Health: Reconceptualizing Disease in Bio-Social Context. Med Anthropol Q (2003) 17(4):423–41. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423

32. Singer MC, Erickson PI, Badiane L, Diaz R, Ortiz D, Abraham T, et al. Syndemics, Sex and the City: Understanding Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Social and Cultural Context. Soc Sci Med (2006) 63(8):2010–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.012

33. Singer M. A Dose of Drugs, a Touch of Violence, a Case of AIDS: Conceptualizing the SAVA Syndemic. Free Inq Creat Sociol (2000) 28(1):13–24.

34. Singer M. Introduction to Syndemics: A Critical Systems Approach to Public and Community Health. CA Jossey-Bass: San Fransisco (2009).

35. Simon GG. Impacts of Neglected Tropical Disease on Incidence and Progression of HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria: Scientific Links. Int J Infect Dis (2016) 42:54–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.11.006

36. Alemu A, Shiferaw Y, Addis Z, Mathewos B, Birhan W. Effect of Malaria on HIV/AIDS Transmission and Progression. Parasit Vectors (2013) 6(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-18

37. Yegorov S, Joag V, Galiwango RM, Good SV, Okech B, Kaul R. Impact of Endemic Infections on HIV Susceptibility in Sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines (2019) 5(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s40794-019-0097-5

38. 2020 SMO. Nigeria Malaria Facts (2020). Available at: https://www.severemalaria.org/countries/nigeria.

39. George E, Lung V, Waimar T. Assessment of HIV Testing Misclassifications and Effectiveness of Community-Based HIV Service Delivery Models Among Key Populations in Nigeria. In: Project SOAR Final Report. Washington, DC:USAID (2021).

40. Doherty T, Tabana H, Jackson D, Naik R, Zembe W, Lombard C. Effect of Home Based HIV Counselling and Testing Intervention in Rural South Africa: Cluster Randomised Trial Vol. 346.(United Kingdom:Bmj) (2013).

41. Fylkesnes K, Sandøy IF, Jürgensen M, Chipimo PJ, Mwangala S, Michelo C. Strong Effects of Home-Based Voluntary HIV Counselling and Testing on Acceptance and Equity: A Cluster Randomised Trial in Zambia. Soc Sci Med (2013) 86:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.036

42. Emmanuel G, Folayan MO, Ochonye B, Umoh P, Wasiu B, Nkom M, et al. HIV Sexual Risk Behavior and Preferred HIV Prevention Service Outlet by Men Who Have Sex With Men in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res (2019) 19(1):261. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4108-z

43. Tsai AC, Venkataramani AS. Syndemics and Health Disparities: A Methodological Note. AIDS Behav (2016) 20(2):423–30. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1260-2

44. Quinn KG, Spector A, Takahashi L, Voisin DR. Conceptualizing the Effects of Continuous Traumatic Violence on HIV Continuum of Care Outcomes for Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men in the United States. AIDS Behav (2021) 25(3):758–72. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-03040-8

45. LASG N. The Official Website of Lagos State: Population (2011). Available at: http://www.lagosstate.gov.ng/pagelinks.php?p=6.

46. Wikipedia TFE. Lagos (2015). Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Lagos&oldid=678904313.

47. Turner JM, Rider AT, Imrie J, Copas AJ, Edwards SG, Dodds JP, et al. Behavioural Predictors of Subsequent Hepatitis C Diagnosis in a UK Clinic Sample of HIV Positive Men Who Have Sex With Men. Sex Transm Infect (2006) 82(4):298–300. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.018366

48. Brennan J, Kuhns LM, Johnson AK, Belzer M, Wilson EC, Garofalo R, et al. Syndemic Theory and HIV-Related Risk Among Young Transgender Women: The Role of Multiple, Co-Occurring Health Problems and Social Marginalization. Am J Public Health (2012) 102(9):1751–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300433

49. Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, HM J, McKirnan D, Buchbinder S, Koblin B. Substance Use and Sexual Risk: A Participant-and Episode-Level Analysis Among a Cohort of Men Who Have Sex With Men. Am J Epidemiol (2004) 159(10):1002–12. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh135

50. Anderson AM, Ross MW, Nyoni JE, McCurdy SA. High Prevalence of Stigma-Related Abuse Among a Sample of Men Who Have Sex With Men in Tanzania: Implications for HIV Prevention. AIDS Care (2015) 27(1):63–70. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.951597

51. Stall R, Wiley J. A Comparison of Alcohol and Drug Use Patterns of Homosexual and Heterosexual Men: The San Francisco Men’s Health Study. Drug Alcohol Depend (1988) 22:63–73. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(88)90038-5

52. Mullens AB, Young RM, Hamernik E, Dunne M. The Consequences of Substance Use Among Gay and Bisexual Men: A Consensual Qualitative Research Analysis. Sex Health (2009) 6(2):139–52. doi: 10.1071/SH08061

53. Storholm ED, Volk JE, Marcus JL, Silverberg MJ, Satre DD. Risk Perception, Sexual Behaviors, and PrEP Adherence Among Substance-Using Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Qualitative Study. Prev Sci (2017) 18(6):737–47. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0799-8

54. Butler DM, Smith DM. Serosorting can Potentially Increase HIV Transmissions. AIDS (2007) 21(9):1218–20. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32814db7bf

55. Koester KA, Erguera XA, Kang Dufour M-S, Udoh I, Burack JH, Grant RM, et al. “Losing the Phobia:” Understanding How HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Facilitates Bridging the Serodivide Among Men Who Have Sex With Men. Front Public Health (2018) 6:250. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00250

56. Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Cain DN, Cherry C, Stearns HL, Amaral CM, et al. Serosorting Sexual Partners and Risk for HIV Among Men Who Have Sex With Men. Am J Prev Med (2007) 33(6):479–85. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.08.004

57. Bird JDP, Morris JA, Koester KA, Pollack LM, Binson D, Woods WJ. “Knowing Your Status and Knowing Your Partner’s Status Is Really Where It Starts”: A Qualitative Exploration of the Process by Which a Sexual Partner’s HIV Status Can Influence Sexual Decision Making. J Sex Res (2017) 54(6):784–94. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1202179

58. Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, O’Connell DA, Karchner WD. A Strategy for Selecting Sexual Partners Believed to Pose Little/No Risks for HIV: Serosorting and its Implications for HIV Transmission. AIDS Care (2009) 21(10):1279–88. doi: 10.1080/09540120902803208

59. Organization WH. Prevention and Treatment of HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Men Who Have Sex With Men and Transgender People: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. Prev Treat HIV Other Sex Transm Infect Among Men Who Have Sex With Men Transgender People Recomm a Public Heal Approach. (2011) Geneva:World Health Organisation.

Keywords: key populations, sexual risk behavior, HIV risk, substance use, syndemics, Nigeria (Western), sexual practices, violence

Citation: Dirisu O, Adediran M, Omole A, Akinola A, Ebenso B, Shoyemi E, Eluwa G, Tun W and Adebajo S (2022) The Syndemic of Substance Use, High-Risk Sexual Behavior, and Violence: A Qualitative Exploration of the Intersections and Implications for HIV/STI Prevention Among Key Populations in Lagos, Nigeria. Front. Trop. Dis 3:822566. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2022.822566

Received: 25 November 2021; Accepted: 24 May 2022;

Published: 13 July 2022.

Edited by:

Merrill Singer, University of Connecticut, United StatesReviewed by:

Chuen-Yen Lau, National Institutes of Health (NIH), United StatesLiying Zhang, Wayne State University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Dirisu, Adediran, Omole, Akinola, Ebenso, Shoyemi, Eluwa, Tun and Adebajo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Osasuyi Dirisu, T3Nhc3V5aWRpcmlzdUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Osasuyi Dirisu

Osasuyi Dirisu Mayokun Adediran

Mayokun Adediran Adekemi Omole

Adekemi Omole Akinwumi Akinola1

Akinwumi Akinola1 Bassey Ebenso

Bassey Ebenso Waimar Tun

Waimar Tun Sylvia Adebajo

Sylvia Adebajo