95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Trop. Dis. , 11 October 2022

Sec. Neglected Tropical Diseases

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fitd.2022.808955

This article is part of the Research Topic 2022 in Review: Neglected Tropical Diseases View all 4 articles

Recent years have seen an increase in recognition of the important impact that mental health, wellbeing, and stigma have on the quality of life of people affected by neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), including the publication of global normative guidance and policy frameworks. However, systematic collation of the evidence that can guide greater clarity of thinking for research and practical application of effective interventions is lacking. We used systematic mapping methodology to review the state of the evidence around mental health, stigma, and NTDs in low- and middle-income countries, applying a simple theoretical framework to explore intersections between these areas. We built on existing reviews on the links between each domain, bringing the reviews up to date, across the NTDs identified by the WHO (minus recent additions). After systematic searching of major databases, and exclusions, we identified 190 papers. Data extraction was done to inform key topics of interest, namely, the burden of mental distress and illness/stigma associated with NTDs, the mechanisms by which NTDs add to mental distress and illness/stigma, how mental distress and illness/stigma affect the outcome and treatment of NTDs, and efficacy of interventions to address these domains. We also document the recommendations given by the authors of included studies for research and interventions. We found that there has been a substantial increase in research, which remains very heterogeneous. It was dominated by skin conditions, especially leprosy and, less so, lymphatic filariasis. Few studies had a comparative and even fewer had an intervention design. Our findings were however consistent with existing reviews, pointing to a high prevalence of mental conditions, substantially mediated by stigma and exclusion and a lack of sufficient access to support for mental wellbeing in programmes, despite the existence of effective interventions. These interventions cut across mental health services, stigma reduction, community engagement, and empowerment of people affected. We conclude that the evidence justifies increased investment in practical and integrated interventions to support the wellbeing of people affected by NTDs but that there remains a need for implementation research of consistent quality, and basic science around the impact of mental health interventions on NTD outcomes (including on elimination efforts) needs to be strengthened.

In addition to the considerable suffering and disability associated with neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), affected people often face social exclusion and have high rates of mental illness.

Traditional methods of estimating the burden of disease may not adequately capture adverse mental health effects and broader societal impacts (1, 2). For example, the burden of disease associated with lymphatic filariasis (LF) is around twice as high if a co-morbid depressive illness is taken into account (3). The isolation of physical manifestations of these conditions from emotional and social consequences underestimates not only the impact on people’s lives but also accurate formal measurement, including Global Burden of Disease estimates (4). This has major implications in policy and investment around service provision, though the World Health Organization (WHO) Roadmap for NTDs (2021–2030) has made substantial advances in calling for appropriate integration of comprehensive approaches in NTD programming (5).

Many of the consequences of NTDs are chronic, irreversible, and difficult to hide. They impact key life areas of social salience, such as the ability to work, marry, or meet social role expectations (6) and touch on popular concerns about the etiology, heredity, or transmission of the condition. People affected by NTDs describe emotional consequences such as mental distress and cite a major cause as social exclusion associated with stigma and discrimination, for example, preventing people from playing a full role in society (7–9). This has an impact on people affected and, by association, their families (3). Stigma and mental illness may impact negatively the uptake and effectiveness of NTD treatments, potentially reducing the effectiveness of investment in elimination efforts (9, 10). Recognizing the links between NTDs, stigma, and mental health is therefore important, both to ensure that health programmes adequately meet the expressed needs of those affected and to ensure that comprehensive NTD programming is maximally impactful.

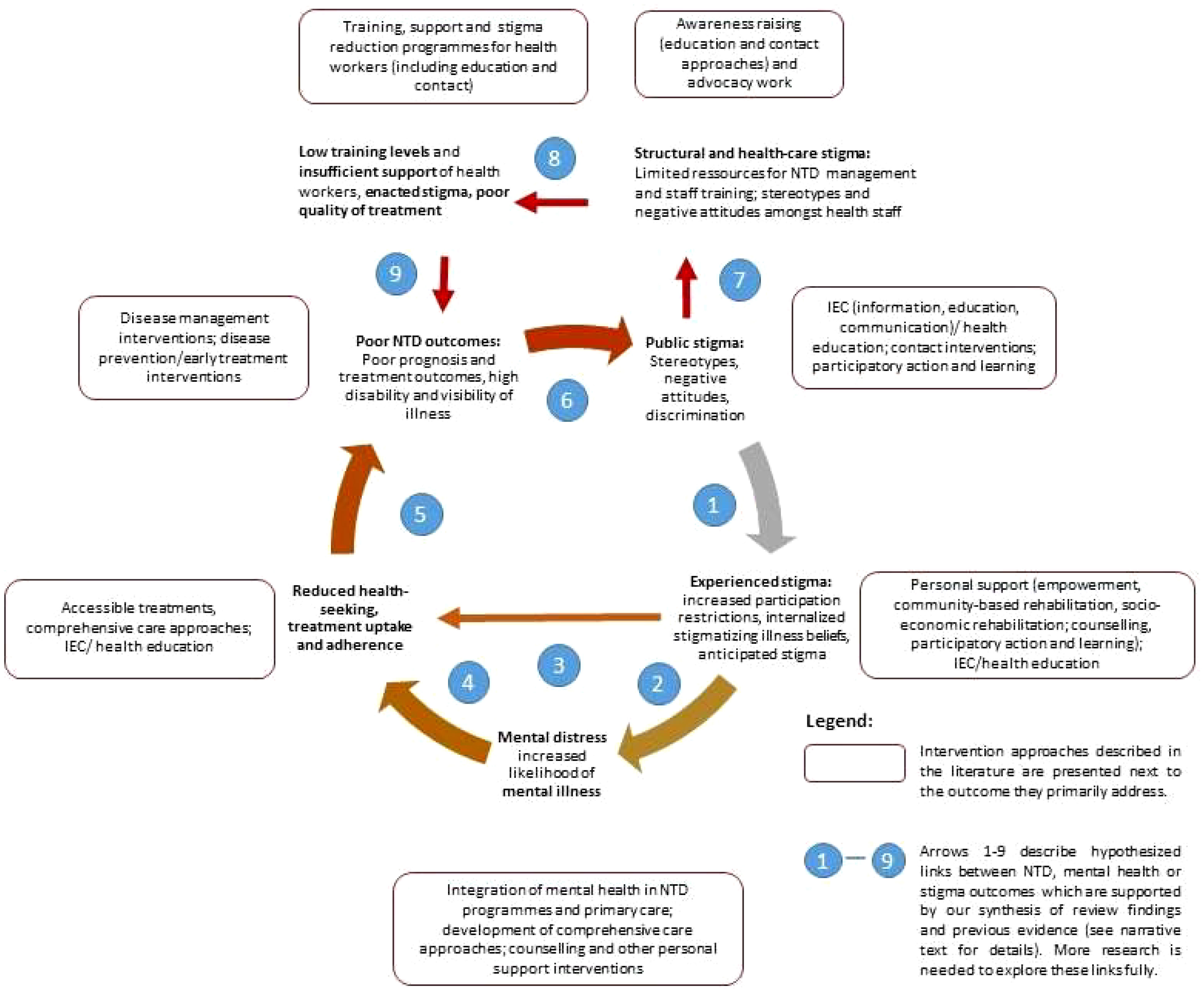

In this paper, we review and summarize the existing evidence on the links between NTDs, stigma, and mental health and derive recommendations for research and lessons for effective interventions to address mental health and stigma-related problems in NTD programmes and community interventions. The nature of these intersecting domains is that there are often mutually reinforcing, complex interactions between multiple social and personal factors. In order to address this, we propose a conceptual framework that clarifies relationships between different elements that we wish to explore, which we hope will also be helpful to guide research and action at several levels and by a range of stakeholders (Figure 1). This review itself also enables an examination of the utility of the conceptual frame in understanding these areas.

Existing review articles cover some elements of this conceptual framework. For example, for Link 1 (NTDs and mental health), a review by Litt and colleagues (11) includes evidence up to and including 2010. This review, which our review served to update, highlighted the links between NTDs and mental health, including depression, suicide, and reduced quality of life. A more recent systematic review by Somar et al. (2020) (12) consolidated evidence on the mental health impacts and determinants of leprosy. The review identified depression, anxiety, and suicide (thoughts and/or attempts) as well as fear, shame, low self-esteem, loneliness, sadness, anger, and reduced quality of life are associated with leprosy. In addition, children (including adolescents) of leprosy-affected individuals were found to have poor mental health outcomes such as depression and low self-esteem.

For Link 2 (NTDs and stigma and discrimination), a seminal systematic review by Hofstraat and van Brakel published in 2016 covers the evidence up to and including 2014 for NTDs other than leprosy (9), and another review summarizes the evidence on leprosy and stigma up to and including 2012, with one study from 2013 included (13). The review by Hofstraat and van Brakel (2016) (9) found that the stigma associated with NTDs causes an enormous social and psychological burden in terms of social exclusion, reduced quality of life, and poor mental health. Leprosy-related stigmatization has been relatively well-researched compared to other NTDs (13–16). People with NTDs are prone to social stigmatization and discrimination, due to the physical impairments and disfigurements that accompany some of the NTDs (17). The reasons why NTDs are stigmatized vary, but the types of stigma, the impact on affected persons and their families, and potential interventions to reduce stigma share many characteristics (9).

Finally, several recent reviews cover the evidence on anti-stigma interventions in the field of mental illness-related stigma (Link 3) up to and including 2012 (18–21). However, due to the main focus of this paper on NTDs, Link 3 was not explored further as part of this review.

The review work carried out for this paper therefore focused on i) the evidence published since these reviews for Links 1 and 2 [using NTD-related search terms of the Hofstraat and van Brakel review (9) and stigma and mental health-related search terms of Thornicroft et al. (19)] and ii) integrates and summarizes both recent and previously reviewed evidence to answer the review questions.

Within the conceptual framework outlined above, we were particularly interested in certain research questions for Links 1 and 2, which served as categories for data summarizing in the data extraction phase of the review (see below). These questions were as follows: i) What is the burden of mental distress and illness/stigma associated with NTDs? ii) What are the mechanisms by which NTDs add to mental distress and illness/stigma? iii) How do mental distress and illness/stigma affect the outcome and treatment of NTDs? iv) What interventions have been employed to address the burden of mental distress and illness/stigma associated with NTDs and which have proven effective? v) What are the recommendations given by the authors of included studies for research and interventions?

The search strategy employed systematic literature mapping techniques as recommended in published guidelines (22, 23) to provide a broad overview of the literature in the field of NTDs, mental health, social exclusion, and stigma (24–26). Mapping reviews aim to map out existing research on a given subject or subject area rather than address one specific review question alone. Articles are not appraised for quality; instead, the aim is to describe and categorize the existing evidence base, identify gaps in the evidence, and derive recommendations. A broad set of search terms were used for each of 1) neglected tropical diseases (as subject heading or text word), 2) mental illness and wellbeing (as the subject heading or text word), and 3) social exclusion/inclusion and stigma (as the subject heading or text word) (see Appendix 1 for search terms used). The search terms were based on earlier seminal reviews in the field (9, 11, 19) and were expanded to include further terms describing wider aspects of mental health and wellbeing, such as (mental health/psychological/emotional aspects of) quality of life (see Appendix 1 for details). We searched Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, and Global Health databases to cover the literature published since the above key reviews, i.e., the search on NTDs and mental health (Link 1) covered the time span 2011–2018 [update to the review by Litt et al., 2012 (11)], whilst the search on NTDs and stigma (Link 2) covered the time frame 2015–2018 for NTDs other than leprosy [update to the review by Hofstraat and van Brakel (2016) (9)] and 2013–2018 for stigma and leprosy [update to the review by Sermrittirong and van Brakel 2014 (13)]. We further searched the repository of NTD-related studies listed under infoNTD.org (27) and infolep.org (28) with the search terms “mental” and “stigma”. All searches were conducted in July 2018.

We applied the WHO definition of neglected tropical diseases valid in 2016 (29), which was also used in the systematic review by Hofstraat and van Brakel (2016) (9) and was described as follows (p.1): “According to WHO, the group of NTDs comprises 17 disease entities, caused by either viruses: dengue/chikungunya and rabies; bacteria: Buruli ulcer, leprosy, trachoma and endemic treponematoses (e.g., yaws); protozoa: Chagas disease, human African trypanosomiasis (HAT or sleeping sickness) and leishmaniasis; or helminths: dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease), echinococcosis, foodborne trematodiases, lymphatic filariasis (LF), onchocerciasis (river blindness), schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminthiasis (STH) and taeniasis/cysticercosis. In addition to this list of 17 disease entities, podoconiosis is also highlighted by WHO as a neglected tropical condition” (9). Recent changes, notably the addition of snake bite envenoming and scabies, are not included here. Given its likely association with onchocerciasis and our aim to map the evidence available as broadly as possible, nodding syndrome was also included in the list of NTDs examined in our review, though we recognize that it is an associated symptom, not a disease per se (30). We analyzed findings separately for cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis.

The field of global mental health has increasingly come to view mental health on a continuum from distress through to diagnosable mental conditions, with increasing levels of functional impact (31). In looking at the intersection of mental illness with NTDs, we took this broad view that the impact on people affected may be at any point on this continuum. Even where distress does not reach diagnostic criteria, this remains a concern of the field and is amenable to appropriate interventions. We have also used diagnoses where relevant, based on findings in the papers, and recognized their value in research and clinical work. In this, we hope to capture the diversity of experiences related to mental health, wellbeing, and disability associated with NTDs. The list of search terms used to capture this domain is accessible in Appendix 1. Epilepsy was not included as a mental health outcome, as we considered neurological conditions to be beyond the scope of this review.

Stigma can be conceptualized as a construct consisting of problems of knowledge (ignorance), problems of attitudes (prejudice), and problems of behavior (discrimination) (32). Discrimination, the behavioral consequence of stigma, contributes to the disability of people affected and leads to social exclusion and disadvantage. In this review, we examine both public stigma (i.e., stereotypes, negative attitudes and discriminatory behavior amongst community members, health staff, or even family members who may stigmatize a person affected by NTDs) and experienced stigma (i.e., the subjective experience of discrimination, exclusion, and devaluation faced by people affected by NTDS and sometimes their family members). The term experienced stigma here also includes the experience of internalized stigma, which is created when people affected accept the discrediting beliefs and prejudices held against them and lose self-esteem (33), leading to feelings of shame, feelings of hopelessness, feelings of depression, a sense of alienation, and social withdrawal (34). This also includes the distress created by anticipated stigma, i.e., the worry about potential negative social reactions, concerns about disclosing the illness, and attempts to prevent this. A further construct is the notion of perceived stigma, which refers to being aware of stigma and discrimination existing in one’s community, without necessarily having experienced it directly. We applied a broad selection of search terms in this review to capture the range of descriptions of stigma in the literature (see Appendix 1).

Studies included were those involving people affected by NTDs as defined above and their family members/caregivers who were living in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) [defined by the World Bank (35)]. We also included studies on community members or health professionals exhibiting stigma towards people with NTDs or their family members/caregivers in those countries. The focus on LMICs was chosen since our mapping review aimed to help inform future interventions in those countries, which carry the great majority of disease burden because of NTDs.

The review included all types of original peer-reviewed research studies (including intervention studies and descriptive studies) published in the time frames specified for the search on each link, provided their main focus was on the outcomes specified below. The specified time frame for the search on Link 2 (NTDs and stigma) was shorter than for the search on Link 1 (NTDs and mental health), and chance findings on stigma outcomes identified outside this time frame within the searches on mental health were not included in our findings for reasons of consistency. Review papers were also searched for, and key findings were referred to in the “Introduction” and “Discussion” sections of this article. Only publications in the English language and with an abstract were included.

A two-stage process was followed in order to determine whether a study addressed the study outcomes in question.

Firstly, we screened abstracts to examine whether the main focus of a study was related to one or both of the following two key study outcomes:

1. Mental health and wellbeing amongst people living with NTDs or

2. Stigma, discrimination, and social exclusion are faced by people living with NTDs.

Articles that simply performed an evaluation of treatments for NTDs were excluded unless the treatments included mental health or social component or measured an outcome that was related to either mental health and wellbeing (mental health components within the quality of life measures were also included as mental health outcomes) or stigma, human rights, and social exclusion (such as social relations, social functioning, or employment). Articles that investigated outcomes solely in relation to, for example, clinical symptoms of NTDs (including neuropsychiatric symptoms) or the acceptability, compliance with, and success of mass drug administration programmes, were excluded. We also excluded papers on knowledge, attitudes, and practices relating to NTDs if they did not specifically relate to the concept of stigma in the sense of social devaluation.

Where an abstract was found to meet the initial criteria, we then reviewed the full paper and included for final selection any paper where the primary or secondary outcome or the main determinant focused on 1) mental health and wellbeing or 2) stigma or social exclusion/inclusion.

Two reviewers (MK and YAH) participated in the selection of abstracts for full-text review. Both independently screened an initial set of 400 abstracts, at which point agreement for study exclusion between them was over 96%. Because of this high level of agreement, the remaining abstracts were divided between the two reviewers. The full texts of the selected articles were then divided amongst a team of five reviewers (EA, MK, MS, PCH, and YAH) to establish whether each retrieved paper met the inclusion criteria on the basis of the full text of the paper. Disparities in inclusion decisions were resolved through discussion. The reviewers did not contribute to inclusion decisions regarding studies in which they were involved. EndNote was used to store all selected studies.

A total of 190 articles were selected for inclusion (see also Figure 2). Data were extracted (by EA, MK, MS, PCH, and YAH) using categories derived from the research questions of the study, for example, “Burden and frequency of mental distress and illness amongst people affected by NTDs”. The first set of 25 studies was coded by two reviewers independently and then discussed in the group until agreement on the level of detail and type of information to be extracted had been achieved. Data were then extracted from the remaining papers separately. Coded data were summarized to identify key cross-cutting findings as well as important differences between diseases and countries for each research question.

Findings are presented separately for each of Links 1 and 2 as shown in Figure 1. In each case, we also provide evidence for the interactions in both directions, as we found interactions between the domains to be bi-directional.

In the review period for the link between NTDs and mental health (1 January 2011 to 22 July 2018), we found 66 studies (with 62 samples) from 26 countries (plus one global study) that reported on the mental health burden or mental distress/disorder associated with 14 of the included NTDs other than leprosy. These studies most commonly used a cross-sectional quantitative design (38 studies), some of which included a comparative element (for example, a control group). A further 12 studies were qualitative, seven were cohort studies, four were case–control studies, two were mixed-methods, one was a case series, one was a pre–post study, and only one was a randomized controlled trial (RCT). We found 53 studies from 13 countries in the review period that reported on the mental health link with leprosy.

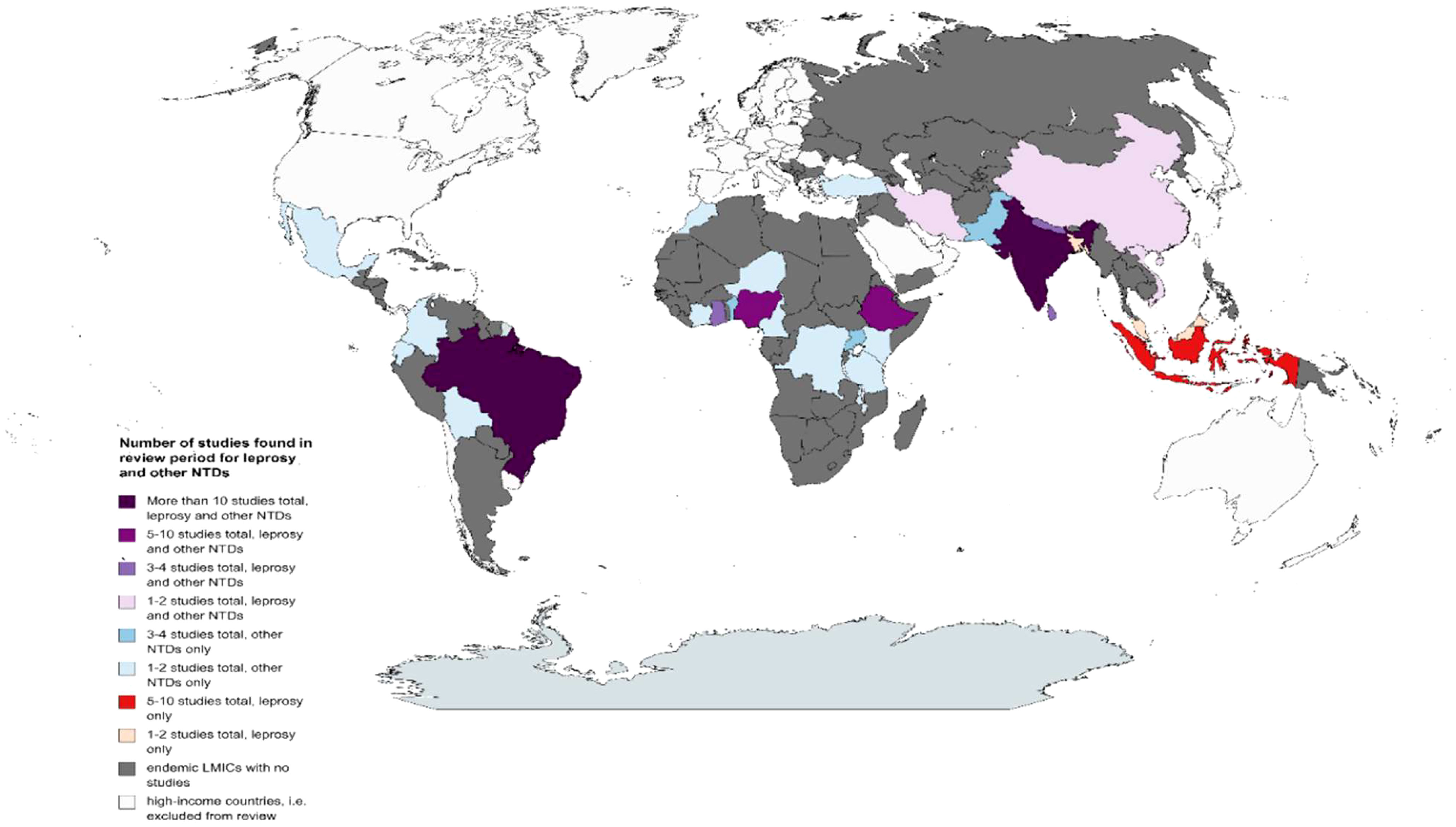

Figure 3 shows those LMICs where we found published studies on the link between NTDs and mental health for both leprosy and other NTDs during the review period. There were over 100 LMICs that are endemic for at least one NTD, for which we did not find any relevant study during the review period.

Figure 3 Map showing countries for which studies were found during the review period on the link between NTDs and mental health. NTDs, neglected tropical diseases.

For NTDs other than leprosy, the region with the most studies conducted in the review period was Africa with 28 studies (nine NTDs), followed by Asia with 20 studies (five NTDs), and the Americas with 17 studies (five NTDs), and there was one global study (see Figure 3). For nine of the included NTDs (other than leprosy), studies came from one region only in the review period, either Africa or the Americas. For five other included NTDs (other than leprosy), studies came from several regions: chikungunya (Americas and Asia), cutaneous leishmaniasis (Africa, Americas, and Asia), dengue (Americas and Asia), lymphatic filariasis (Africa, Asia, and global study), and schistosomiasis (Africa and Asia).

For leprosy, the region with the most studies conducted in the review period was Asia with 30 studies, followed by the Americas with 18 studies (all from Brazil) and then Africa (five studies, see Figure 3).

There was no relevant published study found on the link between NTDs and mental health in the review period for dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease), echinococcosis, endemic treponematoses, foodborne trematodiases, human African trypanosomiasis, rabies, or soil-transmitted helminthiasis.

Findings across studies and NTDs were remarkably consistent in their trend, with poor mental health outcomes reported for all of the NTDs. The outcomes that were particularly salient (i.e. many studies, across different diseases) were mental health components of quality of life (23 studies reported on this outcome during the review period for 11 NTDs other than leprosy and 15 studies on leprosy), depression/depressive symptoms (20 studies for 11 NTDs other than leprosy and 13 on leprosy), and anxiety disorder/anxiety symptoms (13 studies for seven NTDs other than leprosy and five on leprosy).

When looking at each disease separately, the evidence was generally patchy, and for most NTDs only a few studies (five or fewer) were identified within the review period that assessed the burden and/or types of mental health outcomes. Slightly more substantial evidence was available for dengue and lymphatic filariasis (10 studies with nine participant samples each), and many more for leprosy, during the review period.

Table 1 shows the outcomes relating to mental health that were identified in this review, along with the relevant NTDs, and a summary of findings.

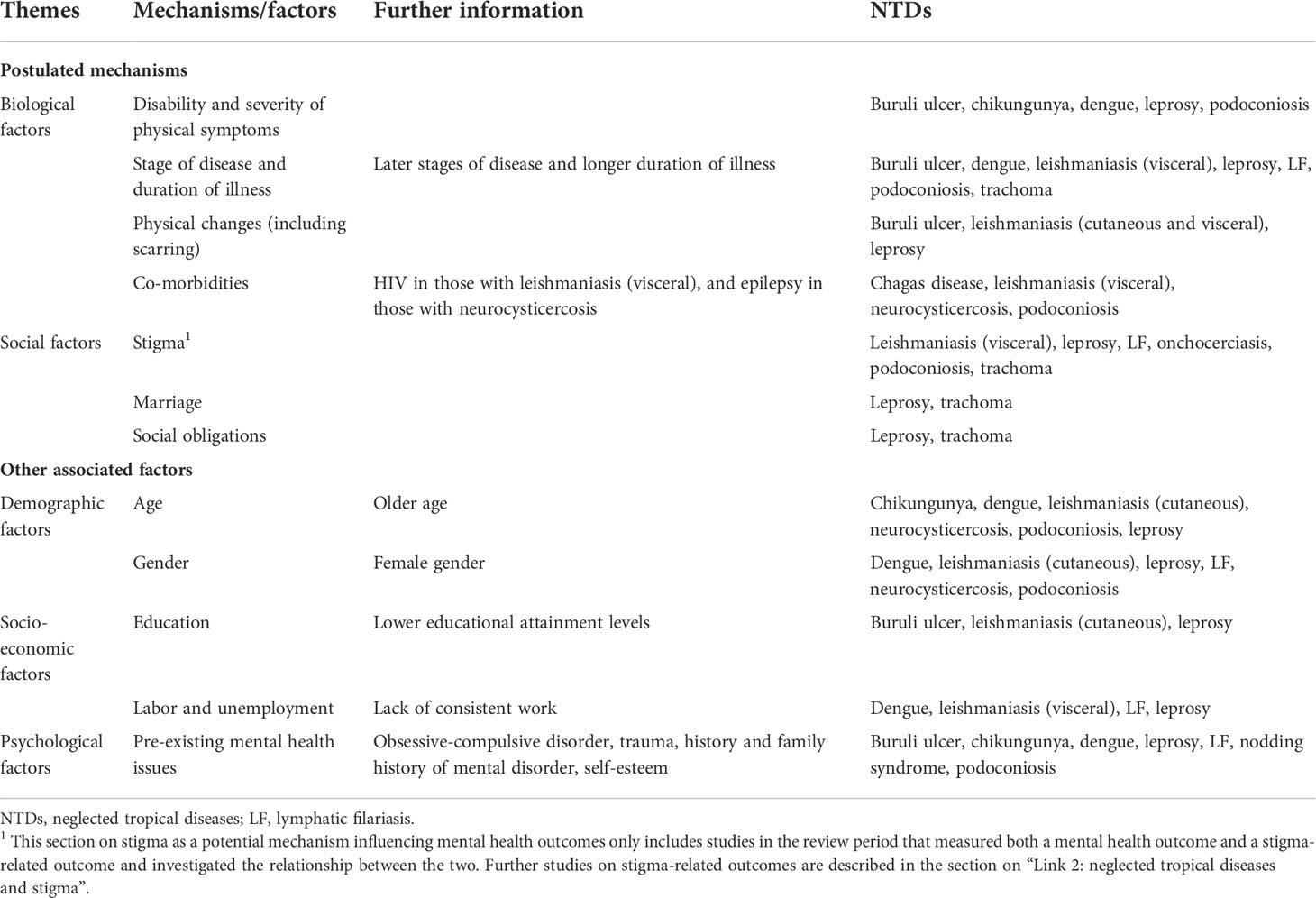

Based on our review, the postulated mechanisms (i.e. factors for which there is a plausible yet unproven causal relationship with mental distress/illness) and other associated factors that may lead to mental distress or illness for people affected by NTDs can be categorized into five broad themes: biological factors including disability, scarring or severity of disease (11 NTDs); demographic factors, including age and gender (10 studies, seven NTDs); psychological factors, i.e., pre-existing mental health issues (seven NTDs); socio-economic factors including education and employment status (four studies, six NTDs); and social factors such as stigma and relationships (six NTDs). See these in Table 2.

Table 2 Postulated mechanisms and associated factors by which NTDs influence mental distress and illness.

By far, the most salient mechanism that has been reported as adding to the reduced mental wellbeing of individuals with NTDs was the biological factors, which were reported for 11 NTDs (including leprosy). The scarring, pain, and physical attributes of the diseases were amongst the most noted factors contributing to distress and mental illness. In addition, across several NTDs, the stage of disease and duration of illness was important. A striking finding by one study was that over half of persons with podoconiosis reported that they had considered suicide in response to discrimination (134).

Most of the evidence reviewed on the link between NTDs and mental health outcomes was cross-sectional in nature, making it difficult to ascertain the directionality of any association. Nevertheless, wherever studies found a causal association to be plausible (see the section on postulated mechanisms above), the assumed direction of causality was that NTD-related factors led to poorer mental health outcomes. At the same time, it is likely that some of the correlational factors mentioned in the section on postulated mechanisms may actually be bi-directional (e.g., disability, stigma, and unemployment). We therefore looked out for evidence that may support a different direction of causality in Link 1 than the one generally assumed (“Link 1 reversed”), and we examined evidence on the impact of poor mental health on NTD-related physical outcomes, which has been reported for many other physical conditions, like HIV and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (140, 141). Overall, it can be said that there is a clear gap in the literature surrounding how mental illness impacts NTD outcomes, with much fewer studies published over the review period compared to those looking at the impact of NTDs on mental health.

By far, the most commonly reported NTD-related outcome was reduced overall quality of life, with nine studies on six NTDs (of which over half were from Latin America) reporting a correlation between poor mental health and overall quality of life (though it is worth noting the point about reverse causality and reinforcing interactions here).

We found one study in the review period demonstrating that mental illness (substance abuse) may be associated with delayed help-seeking behavior and treatment. This study from Iran on cutaneous leishmaniasis (142) showed that those experiencing opium addictions were more likely to delay treatment for fear of withdrawal if hospitalized. Larger lesions were associated with higher drug dependency.

Substance abuse was also found to negatively affect NTD outcomes in a study from Ethiopia, where chewing khat and drinking alcohol were associated with visceral leishmaniasis relapses (resulting in 20% of interviewees changing their substance use habits due to frequent relapses) (84).

In a further study, children with nodding syndrome in Uganda were found to be more likely to drop out of school owing to social, psychological, and physical reasons associated with the illness (85).

In an ethnographic study from Bolivia (118), Chagas disease patients reported the need to be calm (“tranquilo”) for their emotional wellbeing and to lessen the effects of the disease. Even otherwise positive emotions (e.g., excitement associated with going to a party) could be detrimental to their illness if they impact the tranquilidad of an affected person.

In Pakistan, researchers found that depression, anxiety, and stress negatively predicted the self-efficacy of dengue patients (101). In Brazil, pathological hoarding was found to pose a threat to the increasing proliferation of the dengue mosquito Aedes aegypti by putting people at risk owing to poor sanitation and trash accumulation (143).

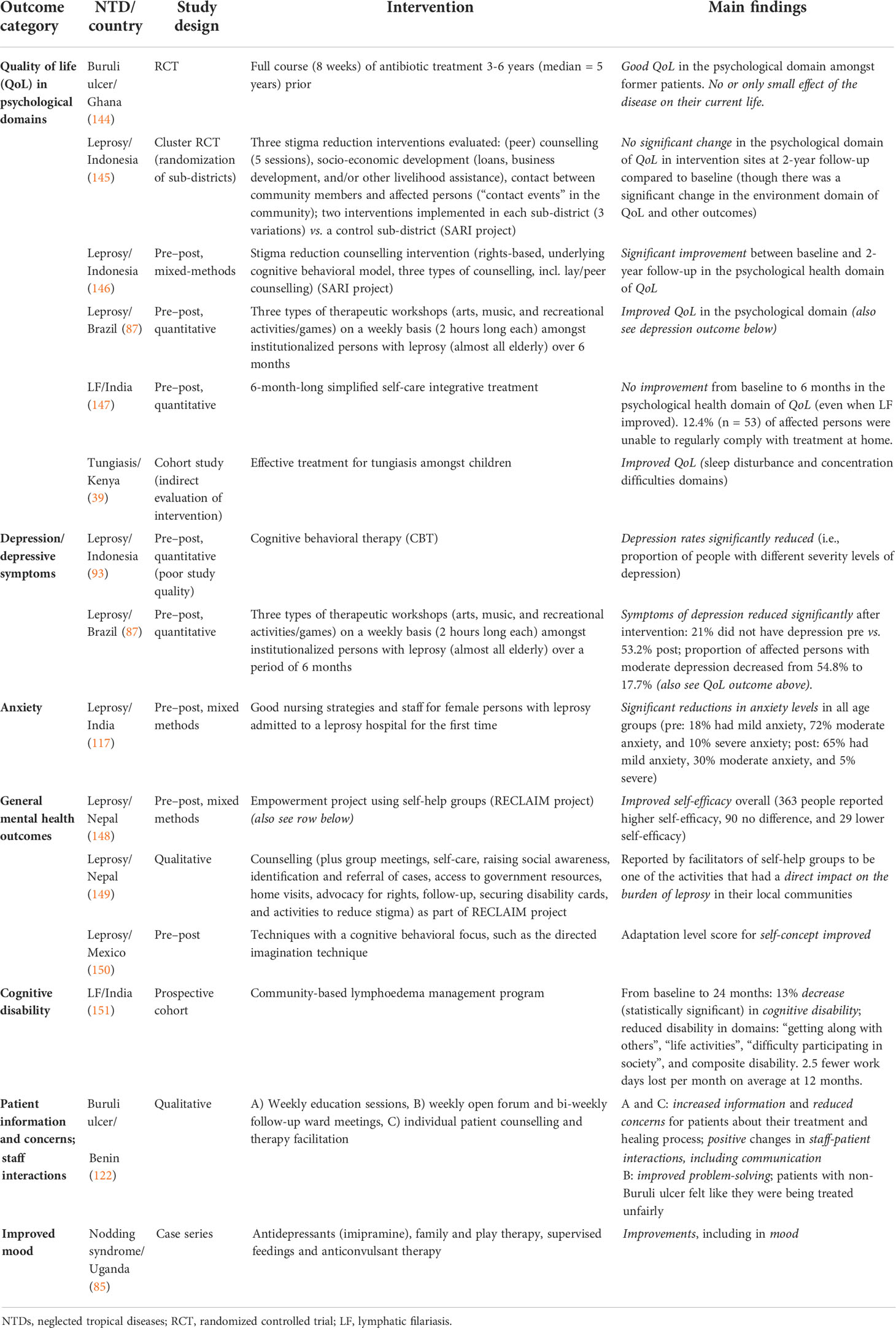

Table 3 provides an overview of studies conducted during the review period that evaluated interventions to address mental illness associated with NTDs or that measured mental health outcomes.

Table 3 Studies evaluating interventions to address mental illness associated with NTDs or that measured mental health outcomes.

In total, 14 studies involved some evaluation of a relevant intervention—eight of these were for leprosy, two each for Buruli ulcer and lymphatic filariasis, and one each for nodding syndrome and tungiasis. Eight studies were from Asia, four were from Africa, and two were from the Americas. There were no studies for the other 16 NTDs that were included in this review, indicating that there is a very large gap in the evidence on interventions, almost certainly demonstrating a gap in actual services in place.

There were only two RCTs during the review period (1 January 2011 to 22 July 2018 for studies on mental health outcomes), both of which included assessments of the psychological health domain of quality of life: a long-term follow-up in Ghana of persons affected by Buruli ulcer with small lesions 3 to 6 years after a full course of antibiotic treatment (144), and a cluster RCT evaluating three different stigma reduction interventions for people with leprosy in Indonesia, counselling, socio-economic development, and contact (145). Whilst the RCT in Ghana reported good quality of life scores (significantly higher than healthy controls) on the psychological domain of the WHOQOL-BREF, the cluster RCT in Indonesia found no significant improvement in the psychological domain of the WHOQOL-BREF between baseline and 2-year follow-up (though it did show improvements in other outcomes). Other studies employed a pre–post design (n = 7) or were cohort studies (n = 2), qualitative studies (n = 2), or case series (n = 1).

There were few universal findings, mainly because of the scarcity of studies conducted and the variety in the types of interventions and outcomes employed. However, all but two of the 14 studies reported positive mental health outcomes, including improvements in the psychological domains of quality of life for leprosy (87, 146), Buruli ulcer (144), and tungiasis (39) [though two studies reported no improvements in the psychological aspects of quality of life (145, 147)]; reduced depression symptoms for leprosy (87, 93); reductions in anxiety levels and improvements in self-efficacy and self-concept for leprosy (117, 148, 150); lessened burden of leprosy (149); decreased cognitive and other disabilities for LF (151); improvements in patient information, patient–staff interactions, problem-solving, and reduced patient concerns for Buruli ulcer (122); and improvements in mood for nodding syndrome (85).

The only two outcomes that were assessed by more than one study were quality of life in psychological domains (n = 6) and depression/depressive symptoms (n = 2). Four studies found improvements in psychological quality of life: the RCT mentioned above on Buruli ulcer in Ghana (144); one from Indonesia that evaluated a stigma reduction counselling intervention for people affected by leprosy (146); one from Brazil that assessed arts, music, and recreation/games workshops amongst institutionalized leprosy patients (87) (150); and one that reported improved quality of life following effective treatment for tungiasis amongst children in Kenya (39). However, two studies found no improvements in the psychological health domain of quality of life: the cluster RCT from Indonesia mentioned above (145) and a pre–post study on a simplified self-care integrative treatment for persons affected by LF in India (147). Both studies that included depression/depressive symptoms as an outcome were on leprosy and reported positive results in Brazil (87) and Indonesia (93).

Here we summarize some of the implications and recommendations on the link between NTDs and mental health made by the authors of the studies that were included in this review. Our own interpretations of the results are included in the “Discussion” section.

Within the authors’ reflections, the intervention topic was covered the most. With seven studies capturing information on interventions for lymphatic filariasis and a further six for dengue alone, this clearly is a topic that authors feel should have attention paid to. Most studies fit broadly across two categories. Firstly, early intervention was seen as core to reducing the impact of NTDs; this was found across studies for Buruli ulcer, dengue, leprosy, and trachoma. Secondly, the impact of integrating psychosocial care into healthcare more widely was reported as a key intervention to consider for six NTDs: Buruli ulcer, dengue, leprosy, lymphatic filariasis, nodding syndrome, and podoconiosis. The authors asked those designing interventions to include standardized measures such as quality of life to monitor the progress of affected persons. A leprosy study from Nigeria noted that the need for psychiatric evaluation cannot be overemphasized, which was confirmed by a study in China that found that focusing on mental health throughout leprosy treatment was a way to reduce suicidal thoughts in almost a quarter of affected persons. However, the authors clearly stated that whilst integrating psychosocial care is key, the wellbeing of affected persons also depends on the consistent distribution of medication, where appropriate.

Conclusions on implications for research were significantly fewer. Broadly, the authors highlighted the need to standardize measures in NTD and mental health research whilst expanding the scope of study techniques to include quasi-experimental or longitudinal studies and to broaden study populations. Additionally, authors researching chikungunya highlighted the need for further research into health-related quality of life, whereas objective measures of mobility for those with lymphatic filariasis were touted as a useful supplement to self-assessed quality-of-life questionnaires.

No study included in our review made recommendations on how to improve policies relevant to those with NTDs. This is a notable oversight and is an area that future research could focus on, both on the evidence needed to inform policy engagement and on the most effective ways of carrying out such engagement.

The review period for articles on NTDs and stigma was limited to articles published from 1 January 2015 to 22 July 2018 for NTDs other than leprosy and to articles published from 1 January 2013 to 22 July 2018 for leprosy, given that the evidence published previously has been summarized in other systematic reviews (9, 13).

After abstract and full-text review, we included 23 articles on the stigma associated with NTDs other than leprosy: six each on cutaneous leishmaniasis and lymphatic filariasis, five on podoconiosis, two each on Buruli ulcer and visceral leishmaniasis, and one each on Chagas disease and nodding syndrome. There were 16 studies from Africa, five from Asia, and two from the Americas.

We included 81 articles on the stigma associated with leprosy: nine studies from Africa, 56 studies from Asia, and 15 studies from the Americas. There was one multi-country study that included Bangladesh and DR Congo.

No articles were found during the review period on stigma for chikungunya, dengue, dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease), echinococcosis, endemic treponematoses (e.g., yaws), foodborne trematodiases, human African trypanosomiasis (HAT or sleeping sickness), neurocysticercosis, rabies, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminthiasis (STH), trachoma, or tungiasis.

The articles were coded according to different aspects of stigma, such as experiences of stigma faced by people with NTDs or their family caregivers, and stereotypes and attitudes towards people with NTDs; not all studies included had information on all these aspects of stigma.

Just over half of the articles contained information on how people affected by NTDs experienced stigma. There was a wide range of experiences reported, with most evidence available for leprosy (45 papers) and a small number of papers on stigma experience in people with lymphatic filariasis (six), cutaneous leishmaniasis (five), podoconiosis (four), Buruli ulcer (two), visceral leishmaniasis (two), or Chagas disease (one).

The findings on NTDs other than leprosy were analyzed firstly to identify sub-themes of stigma experience present across various diseases (marked in italics in the paragraphs below). These themes were then cross-checked for saturation against the themes present in the much larger literature on stigma experiences amongst people with leprosy. Table 4 outlines sub-themes identified on stigma experience and key findings across NTDs.

One of the most salient themes identified (in terms of presence across different diseases and the number of studies describing it) pertained to experiences of stigma and discrimination of people affected by NTDs reported having experienced from others, for example, in the form of exclusion and avoidance, devaluing comments, mocking, labelling, teasing, and violation of human rights. A few studies directly measured social participation restrictions.

Experiences of stigma were common and burdensome to people with NTDs; for example, a study amongst people with lymphatic filariasis in Nigeria found that nearly all respondents revealed emotionally burdensome experiences of stigma such as being shunned, receiving embarrassing stares and insults, or being viewed as inferior (80). Particularly salient across studies was the impact of stigma on work opportunities and marital relationships and marital prospects.

Sources of enacted stigma were members of the general public, and also people close to the person with the NTD, often their family members. A small number of studies looked at discrimination in healthcare, which was described for leprosy and Buruli ulcer.

Strikingly, internalized stigma with manifestations such as internalized stereotypes, anticipated discrimination, concealment of illness, shame, low self-esteem, and self-isolation was equally salient as experienced stigma in the studies we examined. A few studies on leprosy also described perceived stigma amongst people affected by leprosy, i.e., the degree to which they were aware of population attitudes being negative towards them due to their conditions.

Reduced quality of life in the social domain was another outcome measured in a few studies on leprosy and lymphatic filariasis. A small number of studies also reported that they found no or very little evidence of stigma; for example, one study found leprosy stigma to be virtually absent in an indigenous community in Malaysia (107). Six articles described courtesy stigma, i.e., experiences of stigma faced by the family members of those affected by NTDs.

Many studies reported directly or indirectly on the impact of stigma experiences on mental health, wellbeing, and social outcomes. They illustrated, for example, how emotionally hurtful experiences of exclusion and discrimination were, particularly when enacted by family members, and how stigma drove people into isolation, shame, low self-esteem, and depression. They reported how stigma led to feelings of pessimism, lack of motivation, and, often, contemplation of suicide. Concealment as an attempt to cope with stigma in turn reinforces negative emotions such as sadness, shame, and fear and leads to increased isolation.

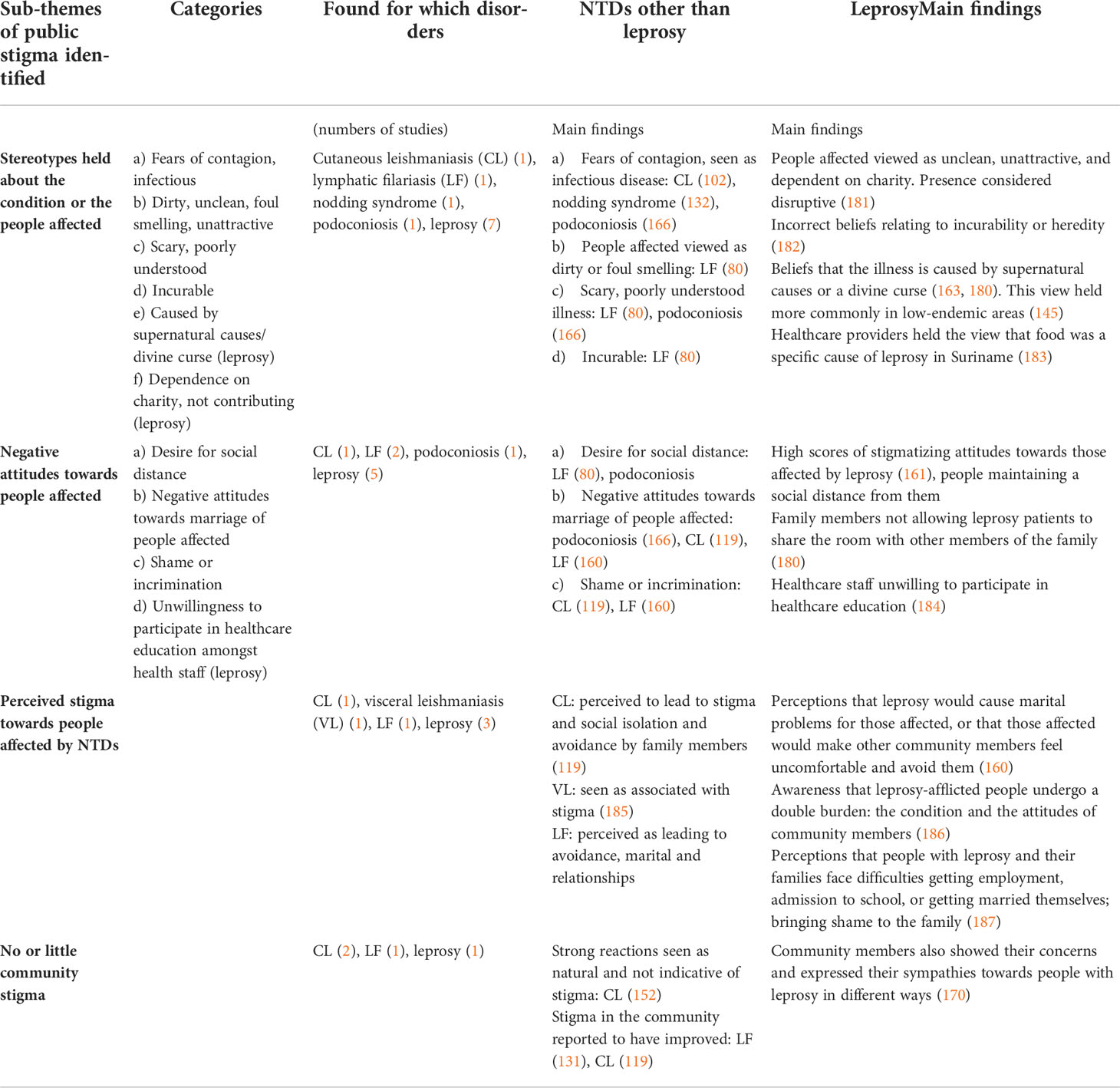

Articles further described stereotypes and negative attitudes towards people with NTDs found amongst community members or health staff. We found slightly less information on this than on experienced stigma faced by those affected, which is partly due to the fact that we excluded papers on knowledge, attitudes, and practices relating to NTDs if they did not specifically relate to the concept of stigma in the sense of social devaluation (for example, articles examining illness beliefs and attitudes with the aim of improving the acceptability of mass drug administration (MDA) programmes).

A total of 65 articles contained information on stigmatizing stereotypes and attitudes towards people with NTDs. Most evidence was available for leprosy (45 papers) and a small number of papers on stigma experience in people with lymphatic filariasis (6), cutaneous leishmaniasis (5), podoconiosis (4), Buruli ulcer (2), visceral leishmaniasis (2), or Chagas disease (1).

As for experienced stigma, the findings on NTDs other than leprosy were analyzed firstly, and sub-themes were then cross-checked against the larger literature on stigma towards people with leprosy. Table 5 outlines the sub-themes identified and key findings across NTDs.

Table 5 Stereotypes and negative attitudes towards people affected by NTDs held by community members or healthcare workers.

Articles across several diseases (leprosy, cutaneous leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, nodding syndrome, and podoconiosis) described stereotypes or stigmatizing beliefs held about the illness or people affected, such as the notion that people affected were contagious, unclean, or not contributing to society or that the illness was incurable, scary, or caused by supernatural forces. The number of articles found was too small to compare stereotypes held on each disease, but several stereotypes were found for several of the NTDs mentioned above.

Similarly, negative attitudes towards people with NTDs were reported for cutaneous leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, podoconiosis, and leprosy. This manifested in a desire for social distance, negative attitudes towards marriage of people with NTDs, feelings of shame and incrimination, or negative attitudes towards attending respective health education, for example. A number of papers reported attitude scores rather than qualitative information on attitudes.

A small number of studies (for leishmaniasis (cutaneous and visceral), lymphatic filariasis, and leprosy) reported on perceived stigma, i.e., community members being aware of people affected by NTDs being avoided, excluded, and discriminated against. Two studies on cutaneous leishmaniasis, one on lymphatic filariasis, and one on leprosy found no or little evidence of public stigma.

The postulated mechanisms (factors for which there is a plausible yet unproven causal relationship with stigma) and other associated factors that may lead to experienced stigma and public stigma are summarized in Tables 6, 7, respectively.

Most research on postulated mechanisms and associated factors concerned demographic factors and socio-economic status, followed by psychological factors. Social factors were little investigated. Leprosy is the most studied disease, but the findings were inconsistent. For postulated mechanisms leading to higher experienced stigma, the strongest evidence was found for biological factors, including a more disfigured appearance and a higher level of disability. A higher level of disability was also associated with higher social participation restrictions. The findings were consistent across various NTDs, with no study reporting conflicting results. For psychological factors, studies focused mostly on leprosy, supporting the association between a lack of knowledge and higher levels of stigma.

Advanced age and female gender were associated with higher levels of experienced stigma. However, several studies on leprosy reported limited evidence of association, and the findings on associations with socio-economic status, particularly education, were also inconsistent.

For postulated mechanisms leading to public stigma, the strongest evidence found concerned psychological factors, including lack of knowledge and fear of transmission. Different NTDs have their own specific local beliefs linked to more stigmatizing attitudes, surrounding religious or magical topics such as punishment by God or witchcraft in leprosy in several countries, or a focus on heredity in podoconiosis in Ethiopia. Longer contact duration reduced stigmatizing attitudes. Some evidence supported the role of lower educational levels in public stigma. The findings for demographic factors such as age and gender are more inconsistent.

As in the section on NTDs and mental health, a substantial limitation in our endeavor to better understand the association between NTDs and stigma outcomes was that several studies were cross-sectional in nature, making it difficult to ascertain the directionality of any association. Nevertheless, given that most of the research reported (see the section under postulated mechanisms) assumed or described an association where NTD-related factors led to stigma and discrimination, we thought it useful to examine evidence on how stigma may influence NTD-related outcomes. Overall, we identified 16 studies that looked at the impact of stigma on leprosy outcomes and six studies across four other NTDs (Buruli ulcer, podoconiosis, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and visceral leishmaniasis) on the impact of stigma on the treatment and outcome of those NTDs.

Stigma was found to have a negative effect on health seeking and treatment uptake in several studies on leprosy, one study on Buruli ulcer, and one on podoconiosis. It was defined as a limiting factor in willingness to seek care for leprosy in Ghana (184) and amongst people with leprosy in Indonesia (169). Relating to Buruli ulcer, a study from Ethiopia (156) found that stigma led to barriers to attendance for treatment mediated by failure to access accommodation and basic services, such as water supplies. Behind this was a popular belief that the disease was contagious and discomfort about the smell. The study reported that “some family members prevented children or other dependents from using the treatment supplies they collected from the (…) outreach clinics because of the discomfort they feel about the smell.” In another study from Ethiopia, on podoconiosis (166), internalized illness beliefs emphasizing heredity and not acknowledging the role of the environment and preventability were found to lessen the likelihood of people wearing protective shoe wear.

Stigma was also found to delay treatment and affect treatment adherence. In a study from Brazil, participants who suspected they had leprosy but feared community isolation were 10 times more likely to wait longer before consulting a doctor for their symptoms (197), meaning that often patients presented later before getting treatment. Majumder (158) came to a similar conclusion in India. Highlighting a similar point, an Indonesian study found that social capital could increase treatment adherence (128).

However, stigma may also act as a motivating factor for treatment, as suggested by a study by Bennis et al. (2017) (102). This found a clear demand for better treatment amongst people affected by cutaneous leishmaniasis, which was attributed to fears about scar-related stigma. The loss of social support and social engagement, for example, as a result of stigma was found to affect the overall quality of life of people affected by visceral leishmaniasis in two studies in Ethiopia (46, 47).

For leprosy, 19 studies investigating interventions to reduce stigma and discrimination were identified, of which 11 were conducted in Indonesia. Two studies were identified for podoconiosis (166, 201) and one for Buruli ulcer (122). No study on interventions to reduce stigma and discrimination were found for Chagas disease, chikungunya, dengue, leishmaniasis (cutaneous and visceral), lymphatic filariasis, neurocysticercosis, onchocerciasis/nodding syndrome, schistosomiasis, trachoma, or tungiasis. See Table 8 for an overview of the interventions aiming to reduce stigma for persons affected by NTDs identified in our review.

A cluster randomized controlled trial examined the effectiveness of three combined stigma-reduction interventions—peer and lay counselling, socio-economic development (SED), and contact events—conducted in the SARI project in Indonesia. Six studies reported findings of the interventions based on the SARI project (145, 146, 168, 176, 186, 202). The SARI project supported the effectiveness of two stigma-reduction strategies: personal support (peer and lay counselling and socio-economic development) and contact intervention, providing qualitative and quantitative evidence.

A cluster randomized controlled trial was found for podoconiosis in Ethiopia (201), investigating three intervention arms: 1) usual care health education, 2) household-based skills training (HB) and community awareness campaign (CAC), or 3) HB and CAC plus a genetics education module (GE). This study supported the effectiveness of a health education intervention. Usual care health education alone was reported to be as effective in experienced and enacted stigma reduction as HB and CAC at 3 and 12 months (166, 201).

Of the other studies, the effective domains of interventions included 1) information, education and communication (IEC)/health education interventions, 2) contact interventions, 3) disease management, 4) personal support, and 5) advocacy.

Most IEC/health education interventions provided education around general knowledge of the disease (162, 180, 203, 204), etiology (166, 201), transmission mechanisms (166, 203), available treatments (122, 166, 203, 204), prevention (166), and related issues including stigma, discrimination, and mental health (203).

For personal support interventions, peer groups fostered self-esteem, self-efficacy, and sense of control (149, 160, 207). Financial support and employment (145, 149, 164, 207) reduced poverty, encouraged health-seeking behaviors, and prevented social isolation. Knowledge (90, 168), personal experience, psychological support (90, 146, 206), human rights awareness, coping skills (90), and solutions to problems (90, 122) were the main focusses of counselling. Lay or peer counsellors were found to promote rapport and to be effective and empowering (168).

One study investigated reconstruction surgery for leprosy as disease management, which was found to be effective in the improvement of self-esteem and acceptance amongst family and community (205).

Contact interventions promoted mutual understanding and normalized the relationships between the affected individuals and their communities (89, 122, 145, 176, 181, 186). This set of interventions has been found to be effective in other areas of health-related stigma, such as mental health. These interventions reduced misconceptions and prejudice (146, 149, 181, 202).

There has been a lack of attention paid in research to specific populations including women, children, and the elderly, for whom general intervention approaches may not be applicable. Only two cluster randomized controlled trials were identified during our review, and few studies reported quantitative findings, which were often based on small sample sizes. Strong evidence was only available for leprosy, with some other evidence for podoconiosis and Buruli ulcer, which causes skin lesions or ulcers. Diseases causing impairment in other parts of the body and wider aspects of disabilities were little investigated.

As in the mental health section, here we report on the implications and recommendations provided by the authors of the stigma studies identified.

Whilst thematic differences between NTDs other than leprosy and leprosy are quite small, the difference in the strength of association and level of detail is stark. We found that 20 studies across seven NTDs other than leprosy included reflections on implications for interventions, whereas leprosy alone had nearly 50 studies that made a recommendation for interventions to reduce stigma in those affected.

Across all NTDs (including leprosy), authors noted health education to be a useful intervention tactic to reduce stigmatization through multiple routes, firstly, through patient education of the disease in order to identify early cases and reduce the severity and chronicity of diseases. Secondly, IEC should be provided to a wider community. Education interventions recognize that incorrect beliefs about disease and disability exist, especially around leprosy. Hence, clear and accurate communication detailing that leprosy is non-contagious, curable, and preventable is a beneficial way to prevent community stigmatization. Additionally, work that seeks to enable, empower, and educate healthcare professionals can increase the chances of early diagnosis, therefore reducing stigma from advanced disease stages.

Integration of psychosocial care and the need for multi-disciplinary actors in the care of those with NTDs was also considered important. For those with lymphatic filariasis, authors highlighted that care should focus on encouraging social participation. Similarly, leprosy researchers suggested that schools and families should be involved in care to ensure that leprosy-affected individuals can overcome feelings of alienation and be able to better navigate negative societal reactions.

The authors called for future research on stigma and NTDs to focus on how societal constructs of gender can act as a stigmatizing factor, exploring interactions between psychological distress, infectious agents, and natural disasters, for example.

Eleven papers on leprosy made recommendations for policies, and only three studies did the same for all other NTDs; and this area requires greater research attention. The authors proposed policy changes such as optimizing resource allocation and water availability to endemic areas, increasing social and economic inclusion, and taking a rights-based approach to the challenges that those with NTDs face. The policies recommended for leprosy could extend to encompass all other NTDs, considering that the overarching themes (as referred to in the mechanisms sections) tend to align.

For information relevant to the impact of stigma on those affected by NTDs, the only information available was from leprosy studies. Author recommendations included the benefit of monitoring patients, self-care groups, and bringing together people with different stigmatized conditions to share the challenges they face. They also recommended prioritizing children’s mental health and physical care.

Our review was designed to update existing reviews in the field (9, 11, 13, 14), which means that its findings are not representative of the overall literature on their own but need to be considered in conjunction with previous evidence. The following sections on Links 1 and 2 therefore summarize the findings of previous research and the additional evidence provided by our review, covering all research questions posed at the outset of this article.

Overall, there is a growing body of evidence illustrating the high levels of co-morbidity between NTDs and poor mental health; however, there has been a heavy focus on leprosy so far, and many other NTDs have received little or no attention. Consistent with previous reviews (11, 12), our review found evidence corroborating that depression/depressive symptoms, anxiety, and reduced (mental health/psychosocial components of) quality of life are the most commonly reported mental health outcomes amongst NTD-affected persons (of which more than one can be present in individuals), followed by a wide range of other issues such as mental distress, suicidal tendencies, and negative feelings like shame, fear, and stress.

Despite this, the emotional and psychosocial consequences of NTDs are still usually not included in conventional estimates of the burden of NTDs (2, 11); to our knowledge, only two studies have attempted to rectify this so far—one of them found that the disability-adjusted life years (DALY) burden of cutaneous leishmaniasis was seven times higher than the previous burden of disease estimates when associated major depressive disorder was included (208), and the other estimated that the global burden attributable to depressive illness in persons affected by lymphatic filariasis was around twice that than the burden attributed to lymphatic filariasis alone and was also substantial for their caregivers (3); much of this falls disproportionately on women (11).

There are various mechanisms through which NTDs add to mental distress and illness. Our review substantiated previous evidence (11, 12) that physical symptoms associated with NTDs like pain, disability, stage, and duration of illness; demographic factors (female gender and age); socio-economic mechanisms including lower income and unemployment; and stigma, discrimination, and participation restriction/exclusion can all contribute to poor mental health outcomes. We identified pre-existing mental health issues as a further possible factor. Prior research has also reported that disease processes for some NTDs (e.g., African trypanosomiasis, Chagas disease, dengue, neurocysticercosis, and schistosomiasis) can directly affect the brain in ways that lead to mental and neurological consequences like epilepsy, reduced cognitive function, dementia, depression, anxiety, agitation, or even manic symptoms or psychosis (209); additionally, it has been noted that drugs commonly used to treat NTDs may impair mood and cause anxiety, agitation, or psychosis (12, 209). Other mediating factors for which there is some evidence for leprosy include lifestyle factors such as a weak social network or inactivity, and—more inconsistently—marital status (being single, separated, or divorced) and living environment (12).

Conversely, there is not much specific evidence on how poor mental health may impact NTD-related outcomes, though similar mechanisms have been documented from research in HIV (210) and mental health (20). Early evidence from our review and other related research suggests that this may include reduced help-seeking behavior and uptake of and adherence to treatment in children dropping out from school and links with the overall quality of life and substance abuse as well as other mechanisms of co-morbidity (e.g., depression as a risk factor for chronic pain) (209). Furthermore, the negative impact of stigma and participation restrictions on mental wellbeing can be mutually enforcing; not only can stigma and discrimination contribute to poor mental health outcomes, but depression and anxiety can in turn aggravate stigma and further diminish participation. Studies on interventions to improve the mental wellbeing of persons affected by NTDs are still sparse and inconsistent in their methodologies and the measures used. Nevertheless, several studies have reported positive outcomes (12) for psychological interventions such as therapeutic workshops, cognitive behavioral therapy, reminiscence group therapy, empowerment projects, and counselling (particularly when peers are involved), as well as physical interventions like surgical correction or drug treatment or in combination. We note again that our review only included studies up to 2018 and that we are aware that other relevant intervention projects have been conducted since then.

Reviewing the literature up to 2015 in 52 studies, Hofstraat and van Brakel (9) found evidence of widespread stigma related to lymphatic filariasis, podoconiosis, Buruli ulcer, onchocerciasis, and leishmaniasis and less firm evidence for Chagas disease, schistosomiasis, trachoma, and STH. Leprosy stigma, however, is documented widely, to the extent that it is seen by many as emblematic of health-related stigma overall. Several systematic reviews, including the two reviews by Sermrittirong et al. (13, 14), which our review served to update, describe aspects of leprosy stigma, such as its causes and determinants (13), or interventions to combat leprosy stigma (14). Nevertheless, comparatively little systematic research has attempted to measure the level or intensity of leprosy stigma (211).

Our review adds to evidence from another 23 studies on stigma related to NTDs other than leprosy (leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, podoconiosis, Buruli ulcer, Chagas disease, and nodding syndrome) and 82 studies on leprosy stigma. Consistent with previous reviews, we found that stigma affects those living with NTDs and also family members (“courtesy stigma”) and can be experienced in many different ways. Particularly salient across diseases were experiences of enacted stigma and discrimination such as avoidance and exclusion, verbal insults and stares, critical comments, blaming and distancing from family members, and violation of personal rights and social participation restrictions. Stigma had a negative impact on people with NTDs’ ability to work and complete education, and their marital prospects and marital relationships (9). Strikingly, we found internalized stigma to be similarly common and impactful as experiences of enacted stigma in the studies we reviewed: across the disease groups for which studies had been done, there were reports of feelings of inferiority, feelings of shame, feelings of low self-esteem, anticipated stigma, attempts to hide the illness, or self-isolation, which also greatly affected social participation. Both enacted stigma and internalized stigma were directly linked to mental health, wellbeing, and social outcomes in many of the studies reviewed, which is also consistent with previous research (9, 13, 212).

Several reviews—mostly in the field of leprosy—have aimed to categorize the reasons or mechanisms by which NTDs are stigmatized and identify risk factors for stigma (9, 13, 213). Sermrittirong et al. (13), for example, distinguished external illness manifestations (physical appearance, odour, etc.), religious and cultural beliefs, and fear of transmission as key causes of leprosy stigma. In addition, the review by Hofstraat et al. (9) described the inability to fulfil a certain gender role, being a burden on family or society, low levels of knowledge about the illness, and advanced disease stage, leading to stigma. The studies included in our review strengthen the evidence base suggesting that visible illness manifestations, higher disability levels, poor knowledge about the illness, and fear of transmission act as mechanisms enhancing NTD-related stigma.

Previous research has also found that stigma affects structural issues such as political commitment to disease management and treatment, priorities and policymaking (9, 10), financial resources, and the way health systems work, including supervision and training levels of health workers. We found little information on these overarching issues of structural stigma; however, we found evidence of health workers holding stereotypes and stigmatizing attitudes towards patients (for Buruli ulcer and leprosy), which is in line with previous research documenting that health worker stigma negatively affects the quality of care, leading to reduced access to diagnosis and treatment (9, 214).

It is not surprising, therefore, that stigma has been found to impact the treatment and outcome of NTDs in areas such as health-seeking behavior, treatment uptake, and adherence (9, 10). Our review also found stigma to have a negative effect on these domains in a small number of studies on Buruli ulcer, podoconiosis, and leprosy, but research evidence in this domain is still scarce and is a priority for further research.

There has been a growing interest in interventions to address NTD-related stigma, yet the evidence on NTDs other than leprosy is still limited, and there are very few intervention studies or evaluations of programmes seeking to address stigma. However, the evidence base for interventions addressing leprosy-related stigma has grown significantly in the last decade and has been summarized in relevant systematic reviews (14, 215–217). Our review adds findings from 19 intervention studies on leprosy, two on podoconiosis, and one on Buruli ulcer. The most rigorous and recent evidence comes from the SARI Project in Indonesia, which was a randomized controlled trial of stigma interventions for leprosy, suggesting the effectiveness of comprehensive, multi-pronged approaches.

Key strategies and related interventions for reduction of NTD-related stigma include i) information, education, and communication (IEC)/health education interventions for patients and the community (9, 14) and also health staff, which aim to raise awareness, reduce stigma, and foster early detection and treatment [the importance of contextualization has been emphasized by several authors (14, 184)]; ii) contact interventions using testimonies and participatory video, which have been shown to improve knowledge and attitudes amongst community members and health staff (145, 186); iii) disease management interventions aiming to lessen the visible impact of NTDs to reduce stigma (9, 205); iv) disease prevention/early treatment interventions aiming to reduce the likelihood of stigmatization through early diagnosis and treatment, for example, in the case of Buruli ulcer, dengue fever, and nodding syndrome (in onchocerciasis) (132, 218, 219); and v) personal support interventions to achieve empowerment, improve self-esteem, and increase participation and community support (9, 14). Personal support interventions may focus on, for example, empowerment, community-based rehabilitation, and peer groups (16); socio-economic development (220); and participatory learning and action or counselling (168) to reduce stigma. vi) Advocacy provides another strategy to address structural stigma and ensure that the rights of people with NTDs are met. Overall, multi-level multi-targeted interventions have been found to have the best chances of success (221).

Our review adds evidence from 22 studies supporting the effectiveness of some of these strategies, particularly health education interventions [found for leprosy (162, 180, 203, 204), podoconiosis (166, 201), and Buruli ulcer (122)], contact interventions [found for leprosy (89, 145, 176, 181, 186) and Buruli ulcer (122)], disease management [found for leprosy (205)], personal support interventions [found for leprosy (90, 145, 146, 149, 160, 164, 168, 206, 207) and Buruli ulcer (122)], and advocacy interventions [in leprosy (146, 149, 181, 202)].

Based on the above synthesis of our review findings with existing research, we postulate a revised framework to describe the relationships between NTD outcomes, stigma, and mental health (see Figure 4). This goes beyond the simple triangular relationship described in our original research framework (see Figure 1) to take account of the cyclical nature of these interconnected and mutually reinforcing aspects of health. The links (arrows) in the diagram in Figure 4 are based on our synthesis of the findings above and other established evidence. However, given the scarcity of research on NTD stigma overall, particularly for diseases other than leprosy, further research should examine the complex relationships that the framework aims to depict in a very simplified way. This applies particularly to the links between stigma experience and mental distress with reduced treatment adherence and uptake (arrows 3 and 4) and links between societal stigma, poor resource allocation, health worker stigma, and low quality of care (arrows 7, 8, and 9).

Figure 4 A negative cycle of stigma affecting mental health, social inclusion, and treatment outcomes.

Nevertheless, we hope that the framework will serve to summarize key points of the evidence reviewed here and help to inform future work in the field. It is briefly described in the following.

Stigma triggers a vicious cycle that leads to disadvantages in many aspects of life, reducing social participation and increasing disability (see Figure 4, arrow 1). Stigmatizing attitudes are often internalized by those affected, leading to feelings of shame and low self-esteem, which—along with social restrictions—cause mental distress and increase the likelihood of depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders (arrow 2). Poor mental health (arrow 3), feelings of shame, and anticipated stigma (arrow 4) reduce self-efficacy and act as a barrier to health-seeking and treatment adherence. All these factors adversely influence the effectiveness of treatments leading to poor recovery rates and maintaining disability levels and visibility of the illness (arrow 5), thereby further reinforcing negative attitudes and discrimination (arrow 6).

In addition to the direct effects of societal stigma, persons suffering from NTDs face several forms of structural stigma, manifested, for example, in the lack of resources allocated to this “neglected” group (arrow 7) and low training levels and negative attitudes amongst healthcare staff (arrow 8). This in turn affects the availability, quality, and uptake of treatments offered (arrow 9), feeding back into the cycle of poor treatment outcomes, persistent stigma, and poor mental health.

Each part of the cycle offers access points for interventions. Based on our synthesis of the research evidence above, we have overlaid potential intervention strategies in Figure 4 below. As pointed out earlier, it is often the case in complex systems that using multiple and complementary interventions can be more effective in bringing effective and sustained change. However, some studies suggest additional risks of the stigma associated with skin NTDs, where there is greater disfigurement (especially of the face), and in women, so there would be value in programmes recognizing the additional needs for these groups and target interventions accordingly. Interventions should also consider and address the specific local beliefs associated with different NTDs, such as ideas around punishment by God or witchcraft in leprosy in several countries, or a focus on heredity in podoconiosis in Ethiopia. Similarly, in relation to mental health, there is value in specifically focusing efforts to identify and respond appropriately to at-risk groups. Some mechanisms may be appropriate to address in specific NTDs, for example, addressing chronic itch in onchocerciasis or neuropathic pain in leprosy or considering anti-epileptic medication for nodding syndrome.

This systematic mapping review covered a complex subject area, given the range of diseases covered under the definition of NTDs, and a broad range of outcomes pertaining to stigma and mental distress and illness. Hence, the review was carried out over a long period, which means that papers less than 3 years old are not included (other than key reviews). The selection of studies was limited in that it only considered scientific papers published in English. No grey literature or doctoral theses were included.

The pragmatic decision to make use of existing reviews for parts of the conceptual framework avoided repetition of work, but even though we attempted to be as consistent as possible in the use of search terms, definitions, etc., there are inevitably some differences in approach between different parts of the framework, for example, in terms of the time frames applied in the literature search. We attempted to incorporate the findings of the other reviews in our conclusions but have not re-analyzed raw data, so we were reliant on the results and conclusions drawn by the other review authors.

We felt that the simple conceptual framework adopted served its purpose well, giving a logical structure to our enquiry. We found that the links between the elements of the framework were relevant; each had rich information to populate them, none were redundant, and we did not identify factors in our review that did not fit into this frame. The complexity and interacting nature of many of the relevant factors affecting people’s lives were difficult to fully outline in this simple framework, and we have now proposed a more complex cyclical framework (Figure 4). Some additional factors (such as the intersection between NTD-related stigma and mental-health-related stigma) certainly warrant greater examination. We further acknowledge the role of context and the effect of social determinants on all parts of the framework (acting in a syndemic manner), which has been omitted here due to the limited scope of the review.

We found that there were a disproportionate number of small, uncontrolled studies, and a great heterogeneity in methods and measurements. Most studies were cross-sectional in nature, and greater use of longitudinal studies would enrich our understanding of course and mechanisms of interaction in particular. In accordance with systematic mapping methodology (22, 23), no quality appraisal of studies was carried out, and therefore, poorer-quality studies were considered on the same level as higher-quality evidence. However, the high level of overall concordance of the findings suggests that a different approach would not have altered the main findings and conclusions.

The studies identified in this review contain rich insights into the way that the mental health and wellbeing of people affected by a variety of NTDs are impacted by their conditions. The prevalence of mental conditions amongst people affected by NTDs is far higher than that of the general population, and stigma and social exclusion seem to be the major mechanisms through which this manifests, with obvious disfigurement, particularly to the face, being of particular importance. Disability, functional restrictions, and physical symptoms like chronic pain are also key factors, and means of reducing mental distress and illness must include comprehensive attention to physical treatment in addition to specific mental healthcare.

Many of the social determinants that influence mental health and stigma cannot be addressed in immediate service provision but require more profound and structural reform to reduce inequity. The well-described mutually reinforcing cycle of poverty and mental illness (or disability) is a good example of the need to intervene in multiple ways to break such cycles (222). As with mental health more broadly, there was less evidence for the role of addressing more upstream structural factors like poverty and other forms of marginalization, even though these were identified as major risk factors for mental illness and populations affected by NTDs tend to be part of the “bottom billion”.

There is strong evidence that stigma and mental illness result in poorer access to healthcare and worse outcomes in other conditions, but this relationship needs to be better characterized for NTDs if investment in mental healthcare and stigma reduction is to be further justified. This is of particular interest to national NTD programmes at the country level, and funders of global efforts to control and eliminate NTDs must be a focus of further research. In order to achieve a substantial improvement in mental health and wellbeing in the lives of people affected by NTDs, mental health and stigma must be core components of NTD strategies, so that the effective approaches identified in this review can be accessed routinely.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

MK and JE conceived the research and developed the methodology, which was refined in collaboration with MS, P-CT, and YHA-H. MK, MS, P-CT, and YHA-H screened and extracted data from the papers. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

MS is supported by the Global Health Research Unit for NTDs at the Brighton and Sussex Medical School, which is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). JE is part-funded through the SUCCEED programme, funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. This research was supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) using Official Development Assistance funding [grant number: NIHR 200140].

The need for a paper that summarized evidence on these issues arose from discussions in the Mental Wellbeing and Stigma Working Group of the Disease Management, Disability and Inclusion (DMDI) cross-cutting group of the NTD NGO Network (NNN), and we are grateful for the commitment of this group and those who work in NNN to raise the profile of inclusion and wellbeing in the NTD sector. We thank Emily Armstrong (EA) for her work in manuscript reviewing and Sara Evans for her methodological guidance. We would like to acknowledge CBM for their support of the lead authors’ time on the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fitd.2022.808955/full#supplementary-material

1. Bailey F, Eaton J, Jidda M, van Brakel WH, Addiss DG, Molyneux DH. Neglected tropical diseases and mental health: Progress, partnerships, and integration. Trends Parasitol (2019) 35(1):23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.11.001

2. Hotez PJ, Alvarado M, Basáñez M, Bolliger I, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, et al. The global burden of disease study 2010: interpretation and implications for the neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Diseases (2014) 8(7):e2865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002865

3. Ton TGN, Mackenzie C, Molyneux DH. The burden of mental health in lymphatic filariasis. Infect Dis Poverty (2015) 4:34. doi: 10.1186/s40249-015-0068-7

4. Bailey F, Mondragon-Shem K, Hotez P, Ruiz-Postigo JA, Al-Salem W, Acosta-Serrano A, et al. A new perspective on cutaneous leishmaniasis–implications for global prevalence and burden of disease estimates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis (2017) 11(8):e0005739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005739

5. World Health Organization. Ending the neglect to attain the sustainable development goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization (2020).

6. Yang LH, Kleinman A, Link BG, Phelan JC, Lee S, Good B. Culture and stigma: Adding moral experience to stigma theory. Soc Sci Med (2007) 1(7):1524–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.013

7. Tsutsumi A, Izutsu T, Islam AM, Maksuda AN, Kato H, Wakai S. The quality of life, mental health, and perceived stigma of leprosy patients in Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med (2007) 64(12):2443–53. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.014

8. Person B, Addiss D, Bartholomew L. Can it be that god does not remember me": a qualitative study on the psychological distress, suffering, and coping Dominican women with chronic filarial lymphedema and elephantiasis of the leg. Health Care Women Int (2008) 29:349–65. doi: 10.1080/07399330701876406

9. Hofstraat K, van Brakel WH. Social stigma towards neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. Int Health (2016) 8:53–70. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihv071

10. Weiss MG. Stigma and the social burden of neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Med (2008) 2(5): e237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000237