94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Trop. Dis., 20 December 2021

Sec. Disease Prevention and Control Policy

Volume 2 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fitd.2021.788188

This article is part of the Research TopicCOVID and Tropical Diseases – intersection of policy and scienceView all 7 articles

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused health, economic, and social challenges globally. Under these circumstances, effective vaccines play a critical role in saving lives, improving population health, and facilitating economic recovery. In Muslim-majority countries, Islamic jurisprudence, which places great importance on sanctity and safety of human life and protection of livelihoods, may influence vaccine uptake. Efforts to protect humans, such as vaccines, are highly encouraged in Islam. However, concerns about vaccine products’ Halal (permissible to consume by Islamic law) status and potential harm can inhibit acceptance. Fatwa councils agree that vaccines are necessary in the context of our current pandemic; receiving a COVID-19 vaccination is actually a form of compliance with Sharia law. Broader use of animal component free reagents during manufacturing may further increase acceptance among Muslims. We herein explain the interplay between Sharia (Islamic law) and scientific considerations in addressing the challenge of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, particularly in Muslim populations.

COVID-19, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus, ignited a pandemic in 2020 and continues to circulate. Elevations in case numbers, circulation of variants of concern and potential variants of high consequence have alarmed the world. A coordinated global response led to development of COVID-19 vaccines in record time. Major vaccination efforts are now ongoing throughout the world (1). Unfortunately, uptake has been hindered for several reasons, including religious beliefs (2). This article will provide an Islamic perspective on COVID-19 vaccines.

In Islam, every aspect of life should align with Sharia (Islamic law), or God’s will for humankind. The sources of Sharia are the Al-Quran (Islamic holy book) and Al-Hadith (record of the words, actions, and the silent approval of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad) (3, 4). To effectuate God’s will, Islamic scholars provide their interpretation through the Islamic body of law called Fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence). While Sharia is the decree of God, Fiqh is accomplished via analysis by Ulama (clerics) of Al-Quran and Al-Hadith. Fiqh is neither sacred nor fixed, as it results from human opinion at a certain place and time and can be modified according to circumstances (3). When Muslims need clarity, Ulama perform ijtihad (best efforts) based on their understanding of Sharia and issue a Fatwa (ruling) to address questions. Since Fatwas are based on Fiqh and Ulamas’ ijtihad, varying scientific background and religious experience of Ulamas or authorized institutions may engender multiple different rulings on an issue, including vaccines (5).

Ulamas formulate Fatwas regarding COVID-19 vaccines by considering Sharia sources and scientific studies. During the Fatwa formulation process, Ulamas attempt to weigh religious and scientific values fairly (6). Fatwas are of critical importance to vaccine acceptance in Muslim populations, which have long had concerns about purity of contents (7). We herein describe current COVID-19 vaccine ingredients and how various authorized Islamic regulators have formed the relevant Fatwas. Understanding vaccine regulation under Islamic law provides insights for increasing vaccine acceptance in Muslim-majority countries, especially during a pandemic.

Vaccines can be generally classified as live or non-live, which distinguishes those containing attenuated replicating strains of the relevant pathogen from those containing only pathogen components or killed whole organisms. In addition to the ‘traditional’ live and non-live vaccines, other platforms have been developed over the past few decades, including viral vectors and nucleic acid-based RNA vaccines (8). Several COVID-19 vaccines have been developed using these new technologies (9, 10). Vaccines contain essential or active components that induce an immune response conferring protection upon subsequent exposure to the target pathogen. Apart from these active components, the main ingredient is typically water. Other ingredients may be added, including adjuvants to improve immunogenicity, preservatives, emulsifiers (such as polysorbate 80), or stabilizers (e.g., gelatin or sorbitol) (11). These added ingredients are typically present in very small quantities.

Products used during manufacturing could also theoretically remain in the final product and are included as potential trace vaccine components (8). For example, inactivation with formaldehyde is commonly used to produce human and animal vaccines such as those against polio, hepatitis A, enterovirus 71, and influenza viruses (12). The formaldehyde is diluted to trace levels in the final product and does not pose a safety concern (13). Other components may include antibiotics, egg or yeast proteins, latex, glutaraldehyde, and acidity regulators (such as potassium or sodium salts). Except in the case of allergy, such as yellow fever vaccination in the context of true egg allergy, there is no evidence of risk to human health from these trace components (8).

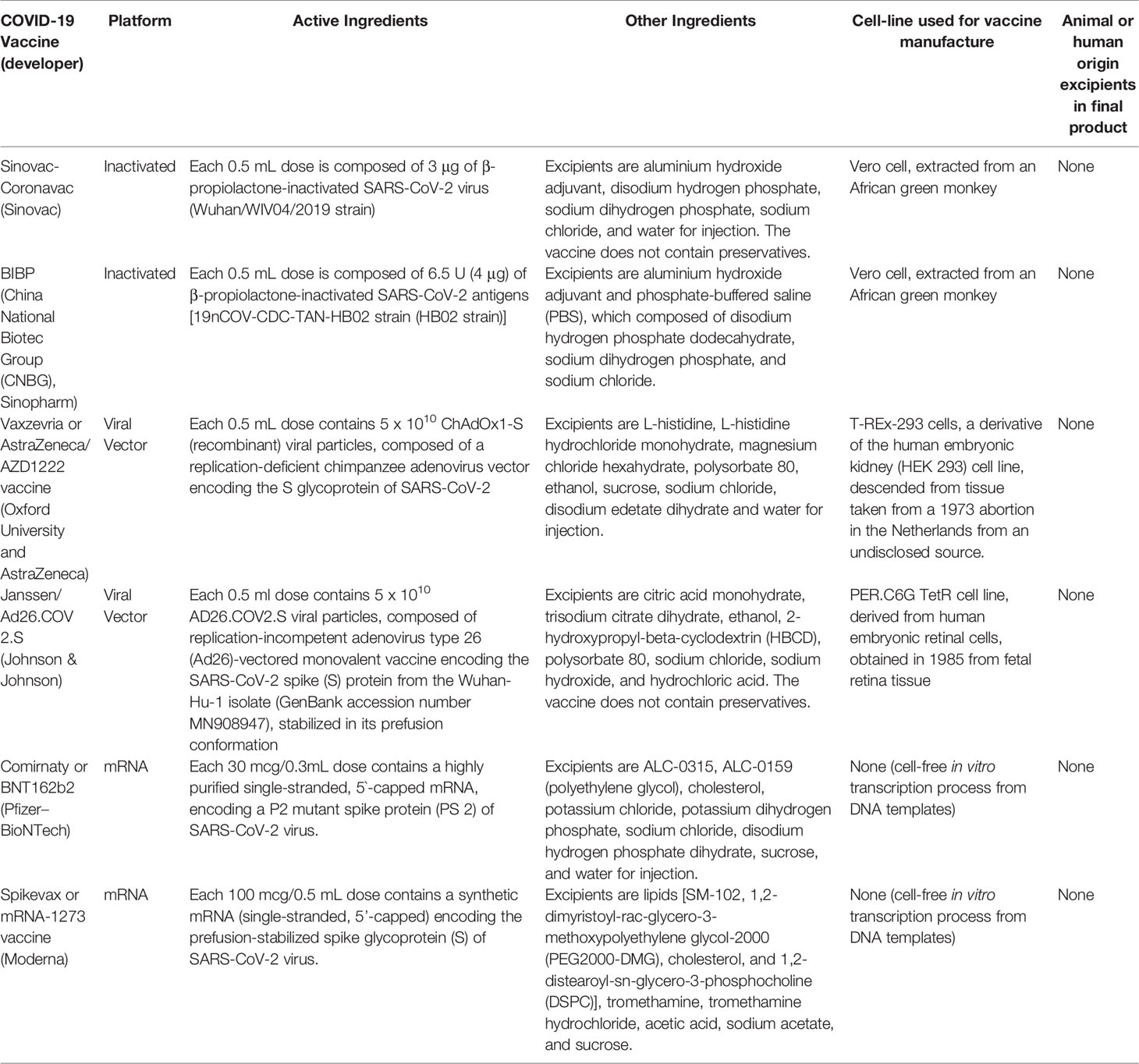

COVID-19 vaccines use several different platforms, with varying active ingredients and excipients. Additionally, some approaches, such as mRNA-based vaccines, are synthetically created in a lab and therefore do not require cell culture during production (9). Composition of COVID-19 vaccines included in WHO’s Emergency Use Listing (EUL) is described in Table 1 (14–19).

Table 1 Active and excipient ingredients of COVID-19 vaccines included in WHO’s Emergency Use Listing (EUL).

Vaccination coverage varies with access, affordability, awareness, and acceptance. Vaccine acceptance is a crucial component of disease prevention, as vaccines are only effective if used. However, some Muslim individuals have concerns that vaccines and other pharmaceuticals may not be Halal, and are therefore more likely to remain unvaccinated (20). There is also heterogeneity in the influence of religion on vaccination practices amongst Muslim-majority countries. In Saudi Arabia, an Islamic theocracy, a survey showed that parents were highly confident in vaccines; even vaccine-hesitant parents did not view religion as prohibiting vaccination. Conversely in Pakistan, which has the world’s second-largest Muslim population after Indonesia, local rumours with religious undertones falsely asserted that the polio vaccine causes sterilization and contains porcine products. Pakistan continues to see polio outbreaks (21).

Halal products are those which are permitted according to the Sharia law. Typically, Halal refers to the permissibility to eat, drink, or act based on Islamic law and principles. Substances used in vaccine manufacturing may be of animal origin, including swine or derivatives, dead animals, or blood, which are Haram or forbidden for Muslims to consume (6, 22). In Islam, Muslims are required to follow Sharia law, which is authoritative. The Holy Al-Quran states: “Therefore, (O Believers) eat of the lawful and good things that Allah has provided for you, and be grateful for His favours if it is true that you only worship Him. Indeed, Allah has forbidden you that which dies of itself, blood, and the flesh of swine; also, any flesh consecrated to something other than in the name of Allah. But whoever is compelled by necessity (to eat any of this) not intending to sin or transgress (regarding the quantity eaten), will find Allah Most Forgiving, Most Merciful”. (Q.S. An-Nahl 16:114-115). The passage explains why Muslims abstain from using Haram material or consuming porcine products and derivatives (6, 23).

Swine are amongst the animals declared as Haram by Sharia law. Using their parts and derivatives in pharmaceuticals will render them non-permissible for consumption by Muslims (22). However, swine derivatives are commonly used in vaccine production, including porcine trypsin and porcine gelatine. Porcine trypsin extracted from the swine pancreas is a reagent used during the propagation stage of production of certain vaccines, e.g., inactivated polio and Japanese encephalitis virus vaccines, to remove or detach cells from the culture tank or vessels before harvesting. It may also be used during the final culture stage of virus production for vaccine activation, such as with influenza virus and rotavirus. Although semi-synthetic (recombinant) trypsin is commercially available, porcine trypsin is commonly used for its lower cost and availability. Porcine trypsin is washed from harvested cells before further processing. Its presence is typically assessed by validated techniques, studies of which have mostly demonstrated undetectable amounts of porcine trypsin in final products (22, 24).

Hydrolyzed porcine gelatine is a mixture of peptides and proteins produced by partial hydrolysis of collagen, typically extracted from swine skin, tendons, ligaments, bones, cartilage, or other components. Porcine gelatine is used in vaccines to stabilize and preserve active ingredients during freeze-drying and storage. Unlike food grade gelatine, the gelatine used for vaccine production is highly purified and broken down into peptides. Although only present in small amounts, a label stating “Contains trace quantities of porcine content” is sometimes required by local product registration policy (2, 22, 24).

In Muslim-populated countries, Halal certification administrators use the Holy Al-Quran as a guide for granting the Halal certificate to applicants. Administrators evaluate the cleanliness of the applicant’s premises and equipment, selection of ingredients, and cross-contamination between Halal and non-Halal products (25). “Halal pharmaceuticals” must contain only ingredients permitted by Sharia law. They must specifically: (1) be free of parts or derivatives of animals declared non-Halal by Sharia law or not slaughtered according to Sharia law; (2) not contain najs (impurities); and (3) not be poisonous, intoxicating, or pose a health hazard to users when taken according to prescription (22). However, interpretation and implementation of Halal pharmaceutical certification varies between countries.

Indonesia has the world’s largest Muslim population, with 87% of its 277 million inhabitants identifying as Muslim. It is diverse in terms of language, ethnicity, and cultural background which, in addition to religion, impact vaccine perception. A fatwa, or ruling under Islamic law, to declare Halal status of a vaccine can be issued by Indonesia’s authorized Halal certification administrators, Indonesian Ulama Council (MUI) (21). The first COVID-19 vaccine authorized in the country, Sinovac, was granted a Halal and holy certificate by the MUI on January 11, 2021. The certification states that this vaccine does not use porcine trypsin or other animal enzymes during manufacturing (26). The MUI subsequently issued a fatwa on March 19, 2021 stating that the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine is “Haram-permittable”. MUI claimed it is Haram because it uses porcine trypsin during the early production process, but is permittable to use (or Mubah) due to the urgency of addressing COVID-19 (27). Notably, several other nations with Muslim majority populations, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Malaysia, use AstraZeneca vaccine without concern over whether it is Halal or Haram (28). Additionally, the Indonesian Food and Drug Monitoring Agency (BPOM) and WHO have confirmed the absence of porcine products in the AstraZeneca vaccine (16, 28). Some COVID-19 vaccines, the Sinopharm and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines are also deemed Haram-permittable, and can be used for emergencies. Other COVID-19 vaccines that have been granted EUA from BPOM, such as Moderna, J&J, Sputnik V, and CanSino, are not yet Halal/Haram certified by MUI as of September 2021 (https://mui.or.id/).

Some fear that COVID-19 vaccines will suffer the same fate as the measles−rubella combination vaccine introduced to Indonesia in 2017 (28). At that time, MUI issued a fatwa that the vaccine was Haram due to porcine components being used in the manufacturing process. After the MUI fatwa declaring it Haram, uptake declined precipitously. While all six provinces on Java reached the 95% coverage target and saw measles and rubella cases decline by over 90%, coverage of children on other islands has reached only 68%. In Aceh, the only province allowed to practice Sharia law, coverage is only 8%, putting Indonesia at risk for a measles outbreak (21, 29). COVID-19 vaccine coverage disparities are also seen amongst provinces. Aceh again demonstrates extremely low coverage, with only 11.8% of its target population being fully vaccinated (https://vaksin.kemkes.go.id/). Religious considerations should be addressed in vaccine roll-out, with the engagement of religious leaders as a priority, since the fatwa specifically permits the use of non-Halal vaccines in the emergency (21).

Despite potential conflict with Sharia law, clerics in several Muslim countries have accepted vaccines that utilize impure substances such as porcine gelatine in their production process. They concluded that gelatine in vaccines is Halal because it has undergone hydrolysis, which purifies it under an Islamic legal concept called istihalah (perfect change) (2, 30). Istihalah refers to alteration of physicochemical nature to change a non-acceptable Haram product to an acceptable Halal form (31). This view is based on the principle of “transformation” in Sharia law, which is applied to vinegar production from wine (2). Vaccines become acceptable if the impure component is completely transformed into a new substance, different from its origin. Transformation of impure substances through downstream processing, e.g. filtration, to render them negligible in the final product is similarly used with other pharmaceuticals such as Heparin (porcine enzymes) and the Rotavirus vaccine (porcine trypsin). In Muslim jurisprudence, these processes accomplish istihalah and render the final product permissible for Muslim use (2, 32, 33).

In addition to istihalah, istihlak (mixing) can convert an unclean substance into one that is clean (34). ‘Istihlak’ refers to mixing of a substance with another until it is dissolved, causing loss of properties even though the substance still exists. Thus an unclean product can be mixed with a more dominant clean product to vanquish the unclean characteristics. This concept is adapted from the Hadith, which explains the characteristic of two kolah (about 216-270 litres) of water: “The Prophet was asked about the status of stagnant water being licked by reptiles and wild animals (i.e., whether the water is still clean). Then the Prophet said, “If the water exceeds two kolah, then it does not become unclean”. Another hadith explains “If the water exceeds two kolah, and is then mixed with the unclean, it does not become unclean as long as there is no change in its smell and taste” (33).

The concepts of istihalah and istihlak are not universally accepted by all Ulamas and authorization councils which determine Halal status. Acceptance by fatwa institutions varies based upon interpretation of Sharia law (33). However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, all councils agreed that an effective and safe COVID vaccine is a basic necessity, or darurat (emergency). Recognition as darurat justifies consumption of Haram product if needed in an emergency situation (35). The Holy al-Quran states: “He has only forbidden you what dies of itself (carrion) and blood and the flesh of swine, and that which is slaughtered as a sacrifice for others than Allah. But if one is forced by necessity without willful disobedience nor transgressing due limits, then there is no sin on them. Truly, Allah is Oft-Forgiving, Most Merciful” (Q.S. Al-Baqarah 2:173). COVID-19 vaccines are recognized as necessary or critical for saving lives and ensuring that societies can function. They are equivalent in status to other established basic human needs such as food and shelter, and therefore are eligible to be classified as darurat. A vaccine that protects against harm from SARS-CoV-2 is essential to uphold the principles of sanctity of human life and avoidance of harm (2).

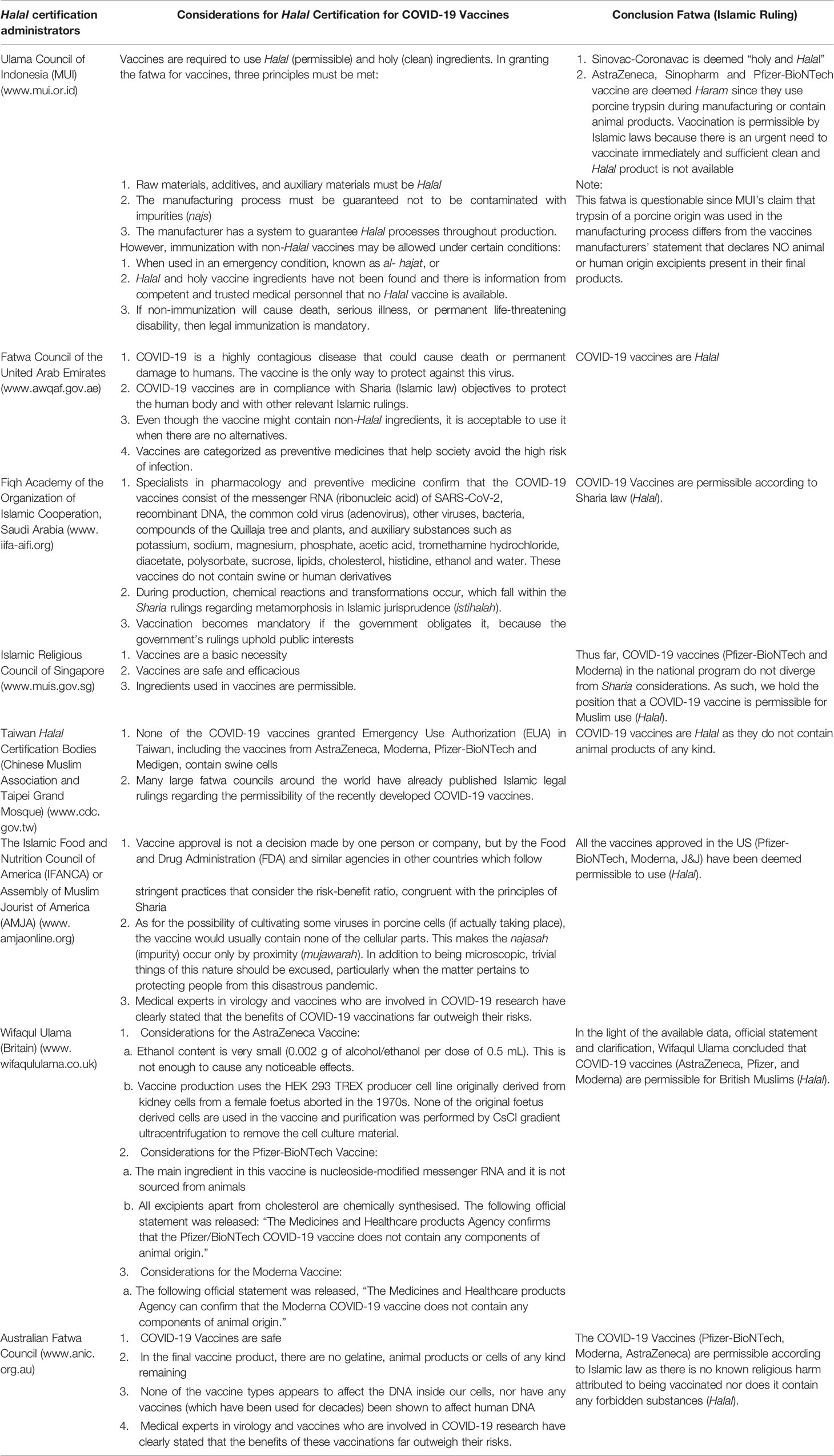

The COVID-19 vaccine development process is also consistent with the principle of the avoidance of harm in Islamic jurisprudence. All vaccines approved for public use undergo stringent safety and efficacy evaluation, which conform to requirements of national ethics bodies (36). Vaccine development reflects the Qur’an’s concept of prevention, or wiqaya, which can refer to preventive actions such as against hell-fire, punishment, greed, bad acts, harm and heat. The Qur’an concludes that prevention is one of the laws of God, so it also applies to the role of vaccination for preventing harm to humans (2, 37). This consideration in combination with scientific data provided a basis for fatwa councils worldwide to publish Islamic legal rulings permitting use of recently developed COVID-19 vaccines, listed in Table 2.

Table 2 Fatwa (Ruling) status and considerations for granting Halal certification of COVID-19 vaccines in several countries.

Vaccines are required to be manufactured under current good manufacturing practices (cGMP) (38–40). cGMP requires that products for human administration should not be contaminated with extraneous materials, including those of animal origin (9 C.F.R. § 113 and 21 C.F.R. 610) (38, 41, 42). Regulations addressing cell culture based biologics became particularly important after the discovery that variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) could be transmitted between species by “prions” or infectious protein, without involving any nucleic acids (43). There is a current push to utilize animal-component-free (ACF) or xeno-free reagents (44). In recent years, progress has been made to generate serum-free media alternatives and ACF products for pharmaceutical manufacturing, including vaccine production. As growth media influences cells’ characteristics, safety and efficacy, comparative studies are essential to understanding the differences, advantages, and challenges associated with specific serum-free/ACF formulations. Nevertheless, the use of ACF reagents during vaccine manufacturing aligns with the Halal way in Sharia, without depending on the acceptance of Istihalah and Istihlak concepts. Thus, the broader use of ACF products in vaccine manufacturing, especially in Muslim countries, could ameliorate vaccine hesitancy associated with Muslim religious beliefs.

From the Islamic point of view, preserving life is aligned with preserving religion (35). Muslims who refuse to receive COVID-19 vaccines may be regarded as acting against Sharia law. Yet Halal certification is only one of many issues that may affect vaccine uptake. The anti-vaccination movement, concerns about long term side effects, accessibility and mis-information pose additional challenges. Effective scientific discourse and communication, including regular engagement with Islamic law scholars, Ulamas, and national regulatory agencies, will be critical for achieving vaccination targets (45).

Individual decisions about accepting COVID-19 vaccines are multifactorial. The Halal issue may pose a significant challenge amongst Muslim populations. Fatwa councils worldwide have used both sharia and scientific approaches to grant Halal certificates for COVID-19 vaccines. Yet there have been inconsistencies across regions. For example, the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine is considered Haram by the Indonesian council but Halal by other councils. Nonetheless, all fatwa councils agree that vaccines are necessary in the context of our current pandemic, and thus receiving a COVID-19 vaccination is actually a form of compliance with Sharia law. Broader use of ACF reagents during manufacturing may further increase acceptance among Muslims.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the study did not analyze any particular data, we reviewed published articles and Islamic laws. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to eW1hcmRpYW5AaW5hLXJlc3BvbmQubmV0.

YM and C-YL conceptualized the manuscript. YM drafted the manuscript. YM, KS-S, and C-YL reviewed the draft of the manuscript, literature, provided critical insights, edited and prepared the final version of the manuscript. All authors analysed, reviewed, and edited the manuscript’s final version and approved it for publication.

This work has been funded in whole or in part with MOH Indonesia; the Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, National Institutes of Health; and Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, under contract Nos. HHSN261200800001E and HHSN261201500003I. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We are grateful to Adhella Menur Naysilla for her feedback and in-depth religious insight. We also thank the Indonesia Research Partnership on Infectious Diseases (INA-RESPOND) Network for the operational support and technical assistance.

1. Ball P. The Lightning-Fast Quest for COVID Vaccines - and What It Means for Other Diseases. Nature (2021) 589(7840):16–8. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03626-1

2. Grabenstein JD. What the World’s Religions Teach, Applied to Vaccines and Immune Globulins. Vaccine (2013) 31(16):2011–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.02.026

3. Yusroh Y, Rahman MZA. Mapping Contemporary Islamic Jurisprudence of Muḥammad Saʻīd Al-’Ashmāwī and Muḥammad Shaḥrūr. IJISH (Int J Islamic Stud Humanit) (2018) 1(1):32–46. doi: 10.26555/ijish.v1i1.132

4. Thalib P. Distinction of Characteristics Sharia and Fiqh on Islamic Law. Yuridika (2018) 33(3):439–52. doi: 10.20473/ydk.v33i3.9459

5. Khoiri N. The Mapping of Renewal of ‘Usul Fiqh’thoughts in Indonesia. Int J Language Res Educ Stud (2017) 1(1):18–33. doi: 10.30575/2017081202

6. Ab Latiff J, Zakaria Z. The Challenges in Implementation of Halal Vaccine Certification in Malaysia. J Food Pharm Sci (2021) 9(1):2. doi: 10.22146/jfps.1147

7. Wong LP, Wong PF, AbuBakar S. Vaccine Hesitancy and the Resurgence of Vaccine Preventable Diseases: The Way Forward for Malaysia, a Southeast Asian Country. Hum Vaccines Immunother (2020) 16(7):1511–20. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1706935

8. Pollard AJ, Bijker EM. A Guide to Vaccinology: From Basic Principles to New Developments. Nat Rev Immunol (2021) 21(2):83–100. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00479-7

9. Mathew S, Faheem M, Hassain NA, Benslimane FM, Thani AAA, Zaraket H, et al. Platforms Exploited for SARS-Cov-2 Vaccine Development. Vaccines (Basel) (2020) 9(1):11. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010011

10. Li Y, Tenchov R, Smoot J, Liu C, Watkins S, Zhou Q. A Comprehensive Review of the Global Efforts on COVID-19 Vaccine Development. ACS Cent Sci (2021) 7(4):512–33. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.1c00120

11. Kocourkova A, Honegr J, Kuca K, Danova J. Vaccine Ingredients: Components That Influence Vaccine Efficacy. Mini Rev Med Chem (2017) 17(5):451–66. doi: 10.2174/1389557516666160801103303

12. Wilton T, Dunn G, Eastwood D, Minor PD, Martin J. Effect of Formaldehyde Inactivation on Poliovirus. J Virol (2014) 88(20):11955–64. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01809-14

13. U. S. Food and Drug Administration. Common Ingredients in US Licensed Vaccines (2014). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/safety-availability-biologics/common-ingredients-us-licensed-vaccines.

14. World Health Organization. Background Document on the Inactivated Vaccine Sinovac-Coronavac Against COVID-19. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE_recommendation-Sinovac-CoronaVac-background-2021.1.

15. World Health Organization. Background Document on the Inactivated COVID-19 Vaccine BIBP Developed by China National Biotec Group (CNBG). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization Rome, Italy (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE_recommendation-BIBP-background-2021.1.

16. World Health Organization. Background Document on the AZD1222 Vaccine Against COVID-19 Developed by Oxford University and Astrazeneca: Background Document to the WHO Interim Recommendations for Use of the AZD1222 (Chadox1-s [Recombinant]) Vaccine Against COVID19 Developed by Oxford. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/background-document-on-the-azd1222-vaccine-against-covid-19-developed-by-oxford-university-and-astrazeneca.

17. World Health Organization. Interim Recommendations for the Use of the Janssen Ad26. COV2. s (COVID-19) Vaccine. Background Document on the Janssen Ad26COV2S (COVID-19) Vaccine: Background Document to the WHO Interim Recommendations for Use of Ad26COV2S (COVID-19) Vaccine (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE-recommendation-Ad26.COV2.S-background-2021.1.

18. World Health Organization. Background Document on Mrna Vaccine BNT162b2 (Pfizer-Biontech) Against COVID-19. License: CC by-NC-SA 3.0 IGO (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/background-document-on-mrna-vaccine-bnt162b2-(pfizer-biontech)-against-covid-19.

19. World Health Organization. Background Document on the Mrna-1273 Vaccine (Moderna) Against COVID-19: Background Document to the WHO Interim Recommendations for Use of the Mrna-1273 Vaccine (Moderna). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/background-document-on-the-mrna-1273-vaccine-(moderna)-against-covid-19.

20. Kabir R, Mahmud I, Chowdhury MTH, Vinnakota D, Jahan SS, Siddika N, et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Intent and Willingness to Pay in Bangladesh: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines (Basel) (2021) 9(5):416. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050416

21. Harapan H, Shields N, Kachoria AG, Shotwell A, Wagner AL. Religion and Measles Vaccination in Indonesia, 1991-2017. Am J Prev Med (2021) 60(1 Suppl 1):S44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.07.029

22. Khoo YSK, Ghani AA, Navamukundan AA, Jahis R, Gamil A. Unique Product Quality Considerations in Vaccine Development, Registration and New Program Implementation in Malaysia. Hum Vaccines Immunother (2020) 16(3):530–8. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1667206

23. Al-Teinaz YR. What is Halal Food? In: The Halal Food Handbook (2020). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley Online Library. p. 7–26.

24. Agency EM. Guideline on the Use of Porcine Trypsin Used in the Manufacture of Human Biological Medicinal Products (2013). Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2013/03/WC500139532.pdf.

25. Latif IA, Mohamed Z, Sharifuddin J, Abdullah AM, Ismail MM. A Comparative Analysis of Global Halal Certification Requirements. J Food Prod Mark (2014) 20(sup1):85–101. doi: 10.1080/10454446.2014.921869

26. Indonesian Ulema Council. Fatwa Majelis Ulama Indonesia Nomor : 02 Tahun 2021 Tentang Produk Vaksin Covid-19 Dari Sinovac Life Sciences, Co. Ltd China Dan PT Biofarma (2021). Available at: https://mui.or.id/produk/fatwa/29485/fatwa-mui-no-02-tahun-2021-tentang-produk-vaksin-covid-19-dari-sinovac-life-sciences-co-ltd-china-dan-pt-biofarma/.

27. Indonesian Ulema Council. Fatwa MUI No 14 Tahun 2021 Tentang Hukum Penggunaan Vaksin Covid-19 Produk Astrazeneca (2021). Available at: https://mui.or.id/produk/fatwa/29883/fatwa-mui-hukum-penggunaan-vaksin-covid-19-produk-astrazeneca/.

28. Tempo. We Need Science, Not Fatwas (2021). Available at: https://en.tempo.co/read/1446020/we-need-science-not-fatwas.

29. Rochmyaningsih D. Indonesian ‘Vaccine Fatwa’sends Measles Immunization Rates Plummeting. Science Magazine (2018). Available at: https://www.science.org/news/2018/11/indonesian-vaccine-fatwa-sends-measles-immunization-rates-plummeting.

30. World Health Organization RO for the EM. Statement Arising From a Seminar Held by the Islamic Organization for Medical Sciences on ‘The Judicially Prohibited and Impure Substances in Foodstuff and Drugs’ (2001). Available at: www.immunize.org/concerns/porcine.pdf.

31. Jahangir M, Mehmood Z, Saifullah, Bashir Q, Mehboob F, Ali K. Halal Status of Ingredients After Physicochemical Alteration (Istihalah). Trends Food Sci Technol (2016) 47:78–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2015.10.011

32. Rochmyaningsih D. Indonesian Fatwa Causes Immunization Rates to Drop. Sci (New York NY) United States (2018) 362:628–9. doi: 10.1126/science.362.6415.628

33. Rosman AS, Khan A, Fadzillah NA, Samat AB. Fatwa Debate on Porcine Derivatives in Vaccine From the Concept of Physical and Chemical Transformation (Istihalah) in Islamic Jurisprudence and Science. J Crit Rev (2020) 7(7):1037–45. doi: 10.31838/jcr.07.07.189

34. Abubakar A, Hukum Vaksin MR. Teori Istihalah Dan Istihlak Versus Fatwa MUI. Media Syari’ah: Wahana Kajian Hukum Islam Dan Pranata Sosial (2021) 23(1):1–15. doi: 10.22373/jms.v23i1.8485

35. Sholeh MAN, Helmi MI. The COVID-19 Vaccination: Realization on Halal Vaccines for Benefits. Samarah: J Hukum Keluarga Dan Hukum Islam (2021) 5(1):174–90. doi: 10.22373/sjhk.v5i1.9769

36. Corey L, Mascola JR, Fauci AS, Collins FS. A Strategic Approach to COVID-19 Vaccine R&D. Sci (New York NY) (2020) 368(6494):948–50. doi: 10.1126/science.abc5312

37. Kasule O. Islamic Legal Guidelines on Polio Vaccination in India. 16th Session of the Fiqh Academy of India (2007). Available at: http://omarkasule-04.tripod.com/id1406.html.

38. US FDA. Guidance for Industry: Characterization and Qualification of Cell Substrates and Other Biological Materials Used in the Production of Viral Vaccines for Infectious Disease Indications. In: Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (2010). White Oak, Maryland: Food and Drug Administration. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/78428/download.

39. US FDA. Facts About the Current Good Manufacturing Practices (Cgmps) (2015). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/pharmaceutical-quality-resources/facts-about-current-good-manufacturing-practices-cgmps.

40. World Health Organization. Good Manufacturing Practices for Biological Products. In: Who Technical Report Series, vol. 822. (1992). p. 20–9. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/biologicals/publications/trs/areas/vaccines/gmp/WHO_TRS_822_A1.pdf?ua=1.

41. Code US, Law P. 21 C.F.R. § 610. In: Code of Federal Regulations (2013). Washington, D.C: Office of the Federal Register. Available at: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-F/part-610.

42. Code US, Law P. 9 C.F.R. § 113. In: Code of Federal Regulations (2017). Washington, D.C: Office of the Federal Register. Available at: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-9/chapter-I/subchapter-E/part-113.

43. Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. Addressing Foodborne Threats to Health: Policies, Practices, and Global Coordination: Workshop Summary. In: Reporting Foodborne Threats: The Case of Bovine Sp. Washington (DC: National Academies Press (US (2006). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK57084/. National Academies Press (US).

44. Fletcher T, Harris H. Safety Drives Innovation in Animal-Component-Free Cell-Culture Media Technology. In: Safety (2016). Iselin, New Jersey: BioPharm International. Available at: http://www.processdevelopmentforum.com/articles/safety-drives-innovation-in-animal-component-free-cell-culture-media-technology/.

Keywords: Halal certificate, Sharia (Islamic law), Fatwa, COVID-19 vaccines, islamic

Citation: Mardian Y, Shaw-Shaliba K, Karyana M and Lau C-Y (2021) Sharia (Islamic Law) Perspectives of COVID-19 Vaccines. Front. Trop. Dis 2:788188. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2021.788188

Received: 01 October 2021; Accepted: 30 November 2021;

Published: 20 December 2021.

Edited by:

Son H. Nghiem, Griffith University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Abhay Machindra Kudale, Savitribai Phule Pune University, IndiaCopyright © 2021 Mardian, Shaw-Shaliba, Karyana and Lau. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yan Mardian, eW1hcmRpYW5AaW5hLXJlc3BvbmQubmV0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.