94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Immunol. , 18 March 2025

Sec. Inflammation

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1496613

The NLRP3 inflammasome complex is an important mechanism for regulating the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and IL-18, in response to harmful pathogens. Overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines has been linked to cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome, arthritis, and other inflammatory conditions. It has been previously shown that tumor progression locus 2, a serine-threonine kinase, promotes IL-1β synthesis in response to LPS stimulation; however, whether TPL2 kinase activity is required during inflammasome priming to promote Il1b mRNA transcription and/or during inflammasome activation for IL-1β secretion remained unknown. In addition, whether elevated type I interferons, a consequence of either Tpl2 genetic ablation or inhibition of TPL2 kinase activity, decreases IL-1β expression or inflammasome function has not been explored. Using LPS-stimulated primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages, we determined that TPL2 kinase activity is required for transcription of Il1b, but not Nlrp3, Il18, caspase-1 (Casp1), or gasdermin-D (Gsdmd) during inflammasome priming. Both Casp1 and Gsdmd mRNA synthesis decreased in the absence of type I interferon signaling, evidence of crosstalk between type I interferons and the inflammasome. Our results demonstrate that TPL2 kinase activity is differentially required for the expression of inflammasome precursor cytokines and components but is dispensable for inflammasome activation. These data provide the foundation for the further exploration of TPL2 kinase inhibitor as a potential therapeutic in inflammatory diseases.

Tumor progression locus 2 (TPL2), also known as MAP3K8 or cancer Osaka thyroid (Cot), is a serine-threonine kinase that acts as a regulator of host immune responses (1). It also operates as a scaffolding protein, and TPL2’s kinase function is negatively regulated through its interaction with NF-κB p105 and ABIN2 (2–4). Ligand binding to toll-like receptors (TLRs), TNF receptor, and IL-1 receptors activates the IKK complex, composed of IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ (5–11). IKK complex activation leads to the phosphorylation and degradation of NF-κB p105 (12). The degradation of p105 releases TPL2 from its complex, allowing it to be phosphorylated and execute its kinase activity, initiating downstream signaling cascades, such as NF-κB, ERK, JNK, and p38. Through these pathways, TPL2 regulates the production of many pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF, and IFN-β (2, 6, 13, 14). In addition to its kinase activity, TPL2 regulates the expression of proteins NF-κB p105 and ABIN2 through its scaffolding function (2–4).

The NLRP3 inflammasome is crucial in the innate immune system’s initial sensing of pathogens and has a role in multiple inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (15, 16), atherosclerosis (17, 18), and multiple sclerosis (19, 20). The NLRP3 inflammasome is a complex of NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1, that functions by cleaving immature pro-inflammatory cytokines, pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, as well as pore-forming gasdermin-D (GSDMD) into their active forms (21–24). NLRP3 inflammasome activation occurs via a two-signal process. In priming, or signal 1, microbial components or extracellular cytokines are recognized by cytokine receptors and pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), such as TLRs and NOD-like receptors. This signaling cascade initiates NF-κB activation, leading to Nlrp3, Il1b, and Il18 mRNA expression (25). During activation, or signal 2, the NLRP3 inflammasome protein complex of NLRP3, ASC, and pro-caspase-1 assembles, triggering its catalytic cleavage of caspase-1 (26–29). Additionally, immature pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 are cleaved by caspase-1 into biologically active cytokines, IL-1β and IL-18. The N-terminal domain of GSDMD protein is cleaved, creating a pore through which the pro-inflammatory cytokines exit the cell (24, 30–32).

TPL2 is critical for controlling inflammation and host responses, but there is limited knowledge on its regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome function, which is also recognized to be highly regulated by phosphorylation events (33, 34). We previously demonstrated that TPL2 induces IL1b mRNA expression (14), and TPL2 has been shown to promote IL-1β secretion in various cell types and contexts (5, 35, 36). Despite the recognition that TPL2 is important for inflammasome pro-inflammatory cytokine synthesis, there is a lack of understanding for how TPL2 regulates the expression of inflammasome components, including NLRP3, caspase-1, and gasdermin-D or whether TPL2 is required for inflammasome function. Additionally, ablating TPL2 increases interferon-β (IFN) production, a type I IFN and a vital pro-inflammatory cytokine that provides protection against viral pathogens (37–40). Type I IFNs can inhibit IL-1β production through multiple cellular mechanisms (41–43). Whether elevated type I IFN signaling contributes to the repression of IL-1β transcription in TPL2-deficient macrophages remains unexplored.

In this study, we aimed to distinguish the roles for TPL2 kinase activity and type I IFNs during inflammasome priming and activation. We found that during inflammasome priming, Il1b transcription is regulated primarily by TPL2 kinase activity and is independent of type I IFN signaling. Ablating type I IFN signaling decreased Il18, Casp1, and Gsdmd transcription during inflammasome priming, demonstrating the regulatory differences between TPL2 kinase activity and type I IFNs. Finally, TPL2 kinase activity was dispensable for inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion when pharmacologically inhibited after priming but prior to inflammasome activation.

Wildtype (WT) C57BL/6 were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (JAX strain #000664) and bred in-house. Tpl2-/- mice backcrossed at least nine generations onto the C57BL/6 WT strain were kindly provided by Dr. Philip Tsichlis (5). Ifnar1-/- mice (B6.129S2-Ifnar1^tm1Agt/Mmjax; #032045-JAX) were kindly provided by Dr. Biao He. Tpl2-/- mice were intercrossed with Ifnar1-/- mice to produce Tpl2-/-Ifnar1-/- mice (44). TPL2 kinase-dead (TPL2-KD) mice with a D270A mutation were generated by Dr. Ali Zarrin (6) and generously provided by Dr. Mark Wilson and Genentech, Inc. Animals were housed in microisolator cages at the University of Georgia Coverdell Rodent Vivarium.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages were isolated from the tibias and femurs of age-matched 6–10-week-old male and female wildtype (WT), Tpl2-/-, TPL2-KD, Ifnar1-/-, and Tpl2-/-Ifnar1-/- mice. Bone marrow cells were cultured in RPMI-160 medium with glutamine (Mediatech, Inc.), 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Neuromics), penicillin-streptomycin (Mediatech, Inc.), HEPES (VWR Chemicals, LLC), 2-ME (Sigma-Aldrich, Co.), and mouse recombinant M-CSF (10 ng/mL, PeproTech, Inc.). Fresh media and M-CSF were added 4 days after isolation. At day 7 post-isolation, cells were harvested using Cellstripper (Mediatech, Inc.) and seeded at 1 x 106 cells/mL in various formats.

BMDMs were pre-treated with or without TPL2 inhibitor TC-S 7006 (10 μM, Tocris) and left unstimulated or stimulated with 100 ng/mL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (E. coli 0111:B4, InvivoGen) at the time intervals indicated. For some experiments, ATP (5 mM, MP Biomedicals and InvivoGen) was added 4 hours after LPS stimulation for the stated duration.

Cell supernatants were removed. Cells were collected in TRK lysis buffer, RNA was extracted from the BMDMs using E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit I (Omega Bio-Tek, Inc.) and converted into cDNA using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). The relative gene expression was measured using probes purchased from Applied Biosystems with Sensifast Probe Hi-ROX kit (Meridian Biosciences). Real time quantitative PCR was performed on the QuantStudio3 instrument (Applied Biosystems). Samples were normalized to the actin internal control and the respective wildtype sample for the experiment using the ΔΔCT method. The probes used were: Il1b (Mm00434228_m1), Il18 (Mm00434226_m1), Nlrp3 (Mm00840904_m1), Casp1 (Mm00438023), Gsdmd (Mm00509958_m1), and Ifnb (Mm00439552_s1).

Cell supernatants were collected for cytokine analysis by ELISA. IL-1β cytokine secretion was detected using Mouse IL-1 beta Uncoated ELISA Kit (Invitrogen). IL-18 cytokine was measured by Mouse IL-18 Uncoated ELISA kit with Plates (Invitrogen). IFN-β cytokine secretion was detected using Rapid bioluminescent murine IFN-β ELISA kit (InvivoGen).

Standard statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad PRISM software version 10.4.1 (627). Individual data points are the average of three biological replicates from a single experiment and the data shown represent the mean ± standard error of mean. Differences between groups were analyzed using two- and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons and were considered statistically significant if p ≤ 0.05. Further statistical analysis details are provided in figure legends.

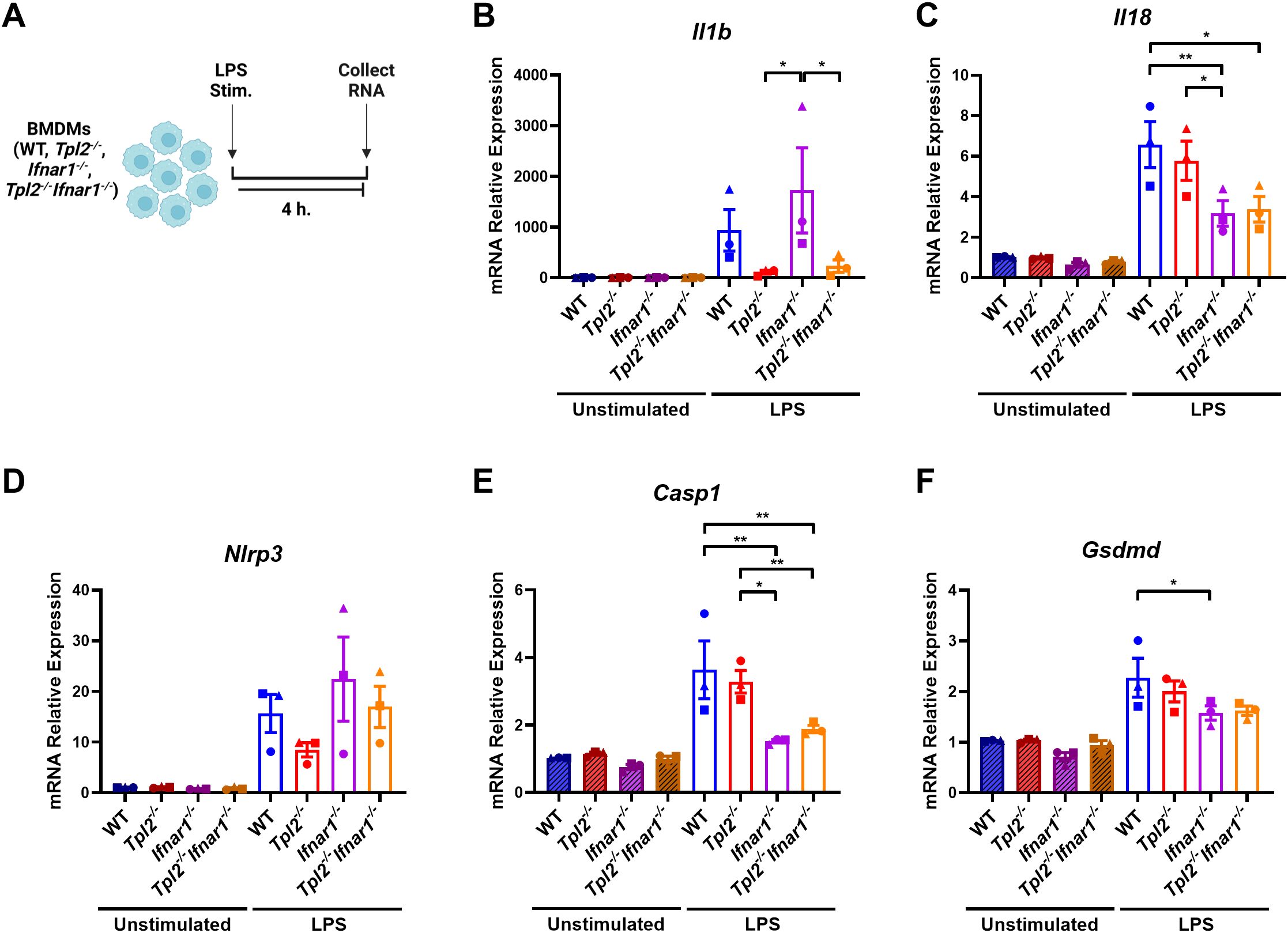

Previous research demonstrated that the absence of TPL2 attenuated IL-1β production during lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation by severely impairing Il1b transcription (5, 14, 35, 36). These studies did not distinguish whether TPL2 promotes IL-1β production by solely regulating Il1b mRNA synthesis during inflammasome priming or if TPL2 also mediates IL-1β cleavage and secretion during inflammasome activation. To evaluate TPL2’s function during inflammasome priming, bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were stimulated with LPS for 4 hours (Figure 1A). LPS stimulation caused a trending increase of Il1b mRNA expression in wildtype BMDMs (Figure 1B). Tpl2-/- BMDMs stimulated with LPS had reduced induction of Il1b mRNA synthesis compared to their unstimulated counterparts (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. TPL2 ablation decreases Il1b expression during inflammasome priming. (A) Experimental design depicting BMDM treatment for inflammasome priming. Image created using BioRender. (B-F) BMDMs isolated from WT, Tpl2-/-, IFNAR1-/-, and Tpl2-/-IFNAR1-/- mice were either unstimulated or stimulated with 100 ng/mL of LPS (LPS Stim.) for 4 hours. BMDMs were collected for mRNA transcription analysis. Gene expression analysis of Il1b (B), Il18 (C), Nlrp3 (D), Casp1 (E), and Gsdmd (F). (B) Not shown on graph: **p<0.01 unstimulated IFNAR1-/- vs LPS IFNAR1-/-. (C) Not shown on graph: ***p<0.001 unstimulated wildtype vs LPS wildtype, and unstimulated Tpl2-/- vs. LPS Tpl2-/-, and *p<0.05 unstimulated IFNAR1-/- vs LPS IFNAR1-/-, unstimulated Tpl2-/-IFNAR1-/- vs LPS Tpl2-/-IFNAR1-/-. (D) Not shown on graph: **p<0.01 unstimulated IFNAR1-/- vs LPS IFNAR1-/-, and *p<0.05 unstimulated wildtype vs LPS wildtype, unstimulated Tpl2-/-IFNAR1-/- vs LPS Tpl2-/-IFNAR1-/-. (E) Not shown on graph: ***p<0.001 unstimulated wildtype vs LPS wildtype, and **p<0.01 unstimulated Tpl2-/- vs. LPS Tpl2-/-. (F) Not shown on graph: ***p<0.001 for unstimulated wildtype vs. LPS wildtype, **p<0.01 unstimulated Tpl2-/- vs. LPS Tpl2-/-, unstimulated IFNAR1-/- vs LPS IFNAR1-/-, and *p<0.05 unstimulated Tpl2-/-IFNAR1-/- vs LPS Tpl2-/-IFNAR1-/-. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed. *p<0.05, **p< 0.01. Each data point represents the average of 3 individual mice. Data graphed represent means ± S.E.M. Data are from 3 independent experiments of both male and female mice.

TPL2 deficiency increases type I IFN cytokine expression, and type I IFNs inhibit IL-1β production (41–43). IFN-β and IFN-α initiate their signaling cascade through the type I IFN receptor, IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, to induce the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) (45, 46). Therefore, to test if early type I IFN signaling decreased Il1b mRNA synthesis in Tpl2-/- BMDMs, Ifnar1-/- and Tpl2-/-Ifnar1-/- BMDMs were simultaneously stimulated with LPS for 4 hours (Figure 1A). Tpl2-/-Ifnar1-/- BMDMs lack both TPL2 protein and a functional type I IFN receptor. These BMDMs do not respond to or initiate the type I IFN signaling pathway, but they do produce and secrete type I IFN cytokines (44, 47, 48). Stimulating Ifnar1-/- BMDMs with LPS induced Il1b mRNA levels, similar to LPS-stimulated wildtype BMDMs (Figure 1B). If increased type I IFNs were contributing to reduced Il1b mRNA synthesis in Tpl2-/- BMDMs, then Tpl2-/-Ifnar1-/- BMDMs would rescue Il1b expression. There was no difference in Il1b mRNA expression between LPS-stimulated Tpl2-/- and Tpl2-/-Ifnar1-/- BMDMs (Figure 1B).

In addition to Il1b, Il18 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine precursor produced during inflammasome priming. We examined if TPL2 ablation reduced Il18 mRNA expression during inflammasome priming by stimulating BMDMs with LPS for 4 hours. There was no difference in Il18 mRNA expression between wildtype and Tpl2-/- BMDMs (Figure 1C), indicating TPL2 is not required for Il18 synthesis. Both Ifnar1-/- and Tpl2-/-Ifnar1-/- BMDMs synthesized lower levels of Il18 mRNA relative to wildtype BMDMs (Figure 1C), consistent with previous publications that observed Il18 mRNA synthesis is dependent on type I IFNs signaling (49, 50).

Next, we assessed whether TPL2 and type I IFNs altered inflammasome component mRNA synthesis during priming, which could potentially result in modified inflammasome activity. Tpl2-/- BMDMs have trending decreases in Nlrp3 mRNA expression (Figure 1D). There was no significant difference in Nlrp3 mRNA levels between wildtype and Ifnar1-/- or Tpl2-/- and Tpl2-/-Ifnar1-/- BMDMs (Figure 1D). The absence of TPL2 did not alter Casp1 mRNA expression relative to LPS-stimulated wildtype BMDMs (Figure 1E); however, the blockade of type I IFN signaling did significantly lower Casp1 mRNA synthesis (Figure 1E). LPS-stimulated Ifnar1-/- BMDMs had significantly less Gsdmd mRNA expression than wildtype LPS-stimulated BMDMs (Figure 1F). Overall, these data indicate that TPL2 deficiency attenuates Il1b mRNA expression, while type I IFN signaling blockade decreases Casp1 and Gsdmd mRNA synthesis.

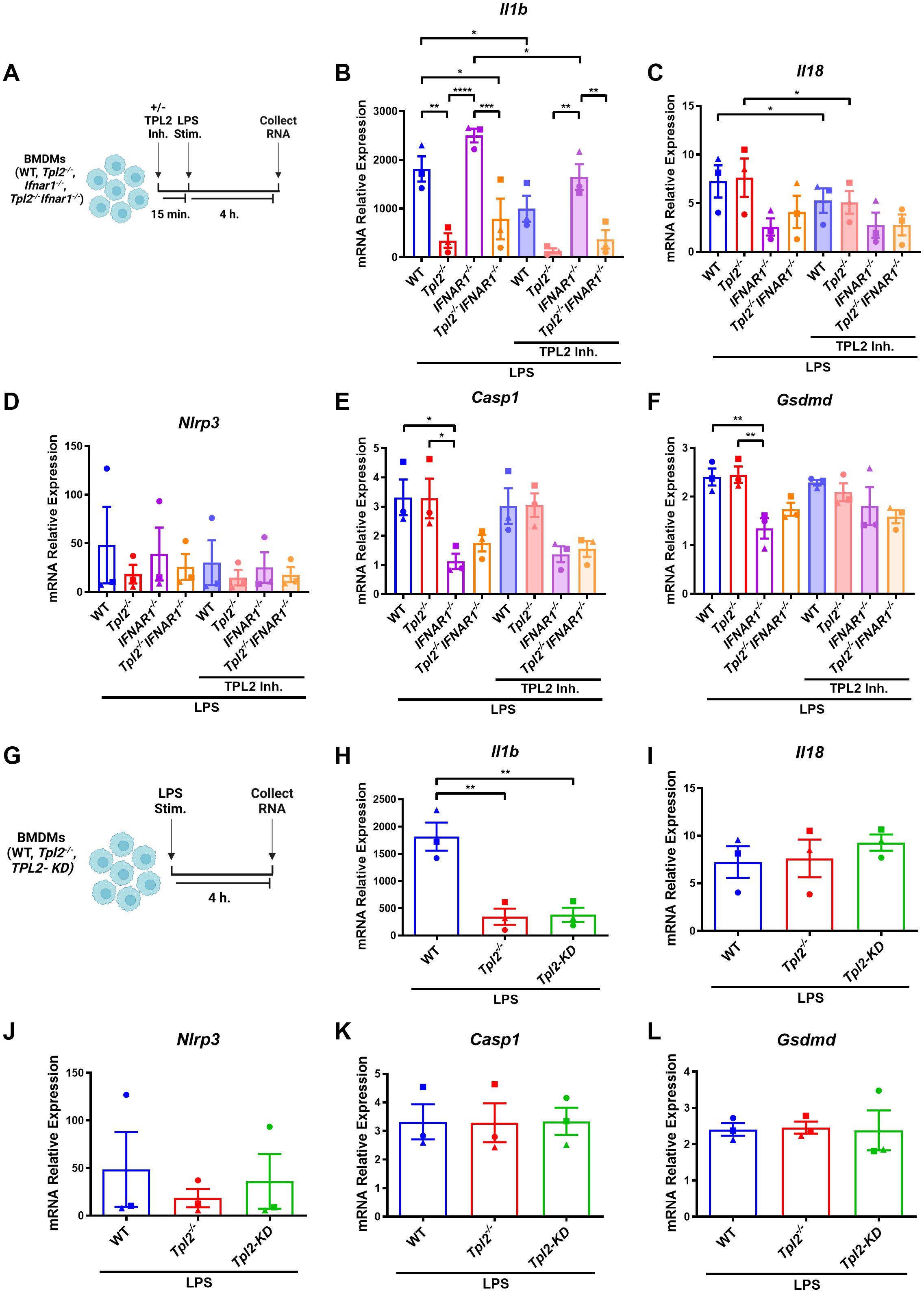

TPL2 has dual roles as both a scaffolding protein and a kinase. In its scaffolding function, TPL2 regulates the maintenance of ABIN2 and NF-κB1 p105 proteins; the interaction with these two proteins inhibits TPL2 kinase activity (2–4). To determine if the changes in Tpl2-/- BMDM Il1b mRNA transcription during inflammasome priming were attributed to TPL2’s kinase activity, BMDMs were treated with TPL2 inhibitor 15 minutes prior to LPS stimulation (Figure 2A). TPL2 inhibitor treatment significantly decreased Il1b mRNA synthesis in wildtype and Ifnar1-/- BMDMs relative to their LPS-stimulated counterparts, confirming that TPL2 kinase activity promotes Il1b mRNA transcription (Figure 2B). Il1b levels were unchanged in Tpl2-/- and Tpl2-/-Ifnar1-/- BMDMs treated with TPL2 inhibitor (Figure 2B). Wildtype BMDMs treated with TPL2 inhibitor showed a modest reduction in Il18 mRNA transcription compared to those stimulated with LPS alone (Figure 2C). The addition of TPL2 inhibitor did not alter Nlrp3, Casp1, or Gsdmd mRNA synthesis (Figures 2D-F).

Figure 2. TPL2 kinase activity regulates Il1b mRNA synthesis. (A) Experimental design depicting BMDM treatment for inflammasome priming with TPL2 inhibitor treatment. Image created using BioRender. (B-F) BMDMs isolated from WT, Tpl2-/-, IFNAR1-/-, and Tpl2-/-IFNAR1-/- mice were treated with or without 10 μM of TPL2 inhibitor TC-S 7006 (+/- TPL2 Inh.) for 15 minutes prior LPS stimulation (LPS Stim.). Approximately 4 hours after LPS stimulation, BMDMs were collected for mRNA transcription analysis. Gene expression analysis of Il1b (B), Il18 (C), Nlrp3 (D), Casp1 (E), and Gsdmd (F). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed. *p<0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. (G) Experimental design depicting BMDM treatment for inflammasome priming with TPL2-KD mice. Image created using BioRender. (H-L) BMDMs isolated from WT, Tpl2-/-, and Tpl2-KD mice were stimulated with 100 ng/mL of LPS (LPS Stim.) for 4 hours, then cells were collected for mRNA expression analysis. mRNA expression analysis of Il1b (H), Il18 (I), Nlrp3 (J), Casp1 (K), and Gsdmd (L). Expression values from WT and Tpl2-/- BMDMs from the same experiment, also shown in (B-F), are replotted here for comparison. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed. **p< 0.01. Each data point represents the average of 3 individual mice. Data graphed represent means ± S.E.M. Data are from 3 independent experiments of both male and female mice.

Because pharmacological inhibition can potentially cause off-target effects, we further verified the importance of TPL2 kinase activity in Il1b mRNA production during inflammasome priming. We utilized BMDMs from TPL2 kinase dead (TPL2-KD, Tpl2D270A) mice, in which the TPL2 protein remains intact but has no kinase activity, to evaluate mRNA synthesis (Figure 2G) (6, 51). Unstimulated TPL2-KD BMDMs exhibited no difference in mRNA expression of inflammasome pro-inflammatory precursors or components relative to all genotypes (Supplementary Figures 1A–E). LPS-stimulated Tpl2-/- and TPL2-KD BMDMs expressed significantly decreased Il1b mRNA compared to LPS-stimulated wildtype BMDMs (Figure 2H). There was no change in Nlrp3, Il18, Casp1, or Gsdmd mRNA synthesis between LPS-stimulated wildtype, Tpl2-/-, and TPL2-KD BMDMs (Figures 2I–L).

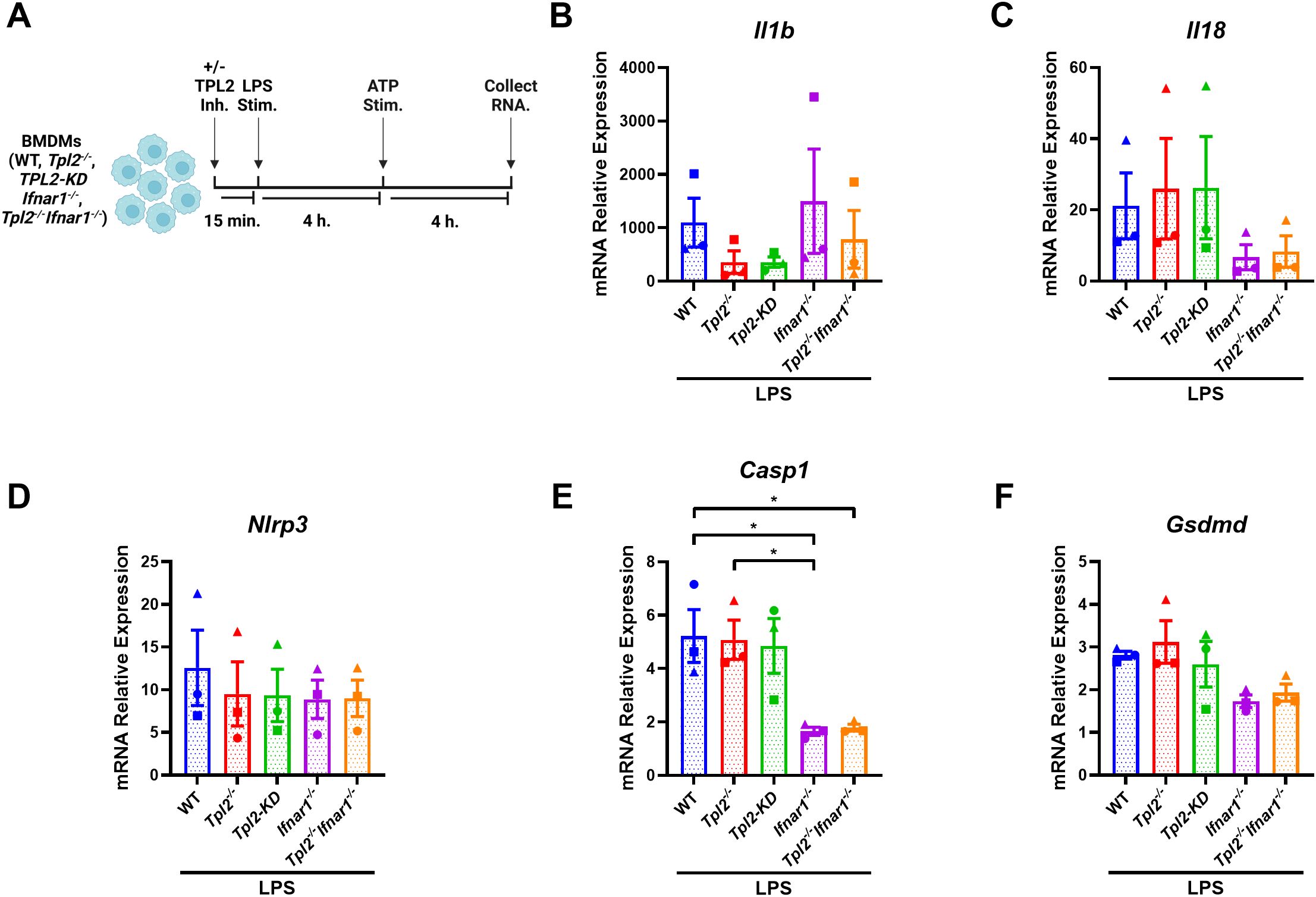

Having established the specific role of TPL2 kinase activity during LPS inflammasome priming, we next examined whether increased type I IFN signaling in Tpl2-/- BMDMs was a contributing factor to alterations in inflammasome mRNA synthesis. Ifnb mRNA synthesis peaks 4 hours after LPS stimulation (Supplementary Figure 2A), and Tpl2-/- BMDMs secrete elevated IFN-β relative to LPS-stimulated wildtype BMDMs (Supplementary Figure 2G). Additionally, mRNA expression of inflammasome-processed cytokines (Il1b and Il18) and components (Nlrp3, Casp1, and Gsdmd) over a 24-hour period indicated that transcription occurred by 4 hours of LPS stimulation and often had the greatest synthesis levels at 8 hours (Supplementary Figures 2B–F). Therefore, to evaluate the effects of type I IFNs on the transcription of inflammasome components, BMDMs were LPS-stimulated for 8 hours with ATP addition after 4 hours (Figure 3A). Il1b mRNA levels 8 hours after LPS treatment followed a similar expression trend across the different BMDM genotypes found in Figure 2B (Figure 3C), and IL-1β cytokine secretion from the various BMDM genotypes matched their Il1b mRNA expression (Supplementary Figure 3A). Nlrp3 mRNA expression was not altered by type I IFN signaling (Figure 3D). Wildtype and Tpl2-/- BMDMs expressed significantly higher Casp1 mRNA relative to BMDMs that lack type I IFN receptors (Figure 3E). Both Ifnar1-/- and Tpl2-/-Ifnar1-/- BMDMs have trending decreases in Il18 and Gsdmd mRNA expression compared to wildtype, Tpl2-/-, and TPL2-KD BMDMs (Figures 3C, F). There was no difference in IL-18 secretion in BMDMs stimulated under these conditions (Supplementary Figures 4B). These data indicate that type I IFNs do not contribute to decreased Il1b mRNA expression during inflammasome function; however, type I IFNs do promote the expression of inflammasome components, such as Casp1.

Figure 3. Type I IFNs do not suppress LPS-induced Il1b transcription but do promote inflammasome component expression. (A) Experimental design depicting BMDM treatment for type I IFN signaling on inflammasome function. Image created using BioRender. (B-F) BMDMs isolated from WT, Tpl2-/-, IFNAR1-/-, and Tpl2-/-IFNAR1-/- mice were stimulated with 100 ng/mL of LPS (LPS Stim.) for 4 hours. After 4 hours of LPS stimulation, 5 mM of ATP (ATP Stim.) was added for 4 hours. At the experimental endpoint, BMDMs were collected for mRNA expression analysis. mRNA expression analysis of Il1b (B), Il18 (C), Nlrp3 (D), Casp1 (E), and Gsdmd (F). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed. *p< 0.05. Each data point represents the average of 2-3 individual mice. Data graphed represent means ± S.E.M. Data are from 3 independent experiments of both male and female mice.

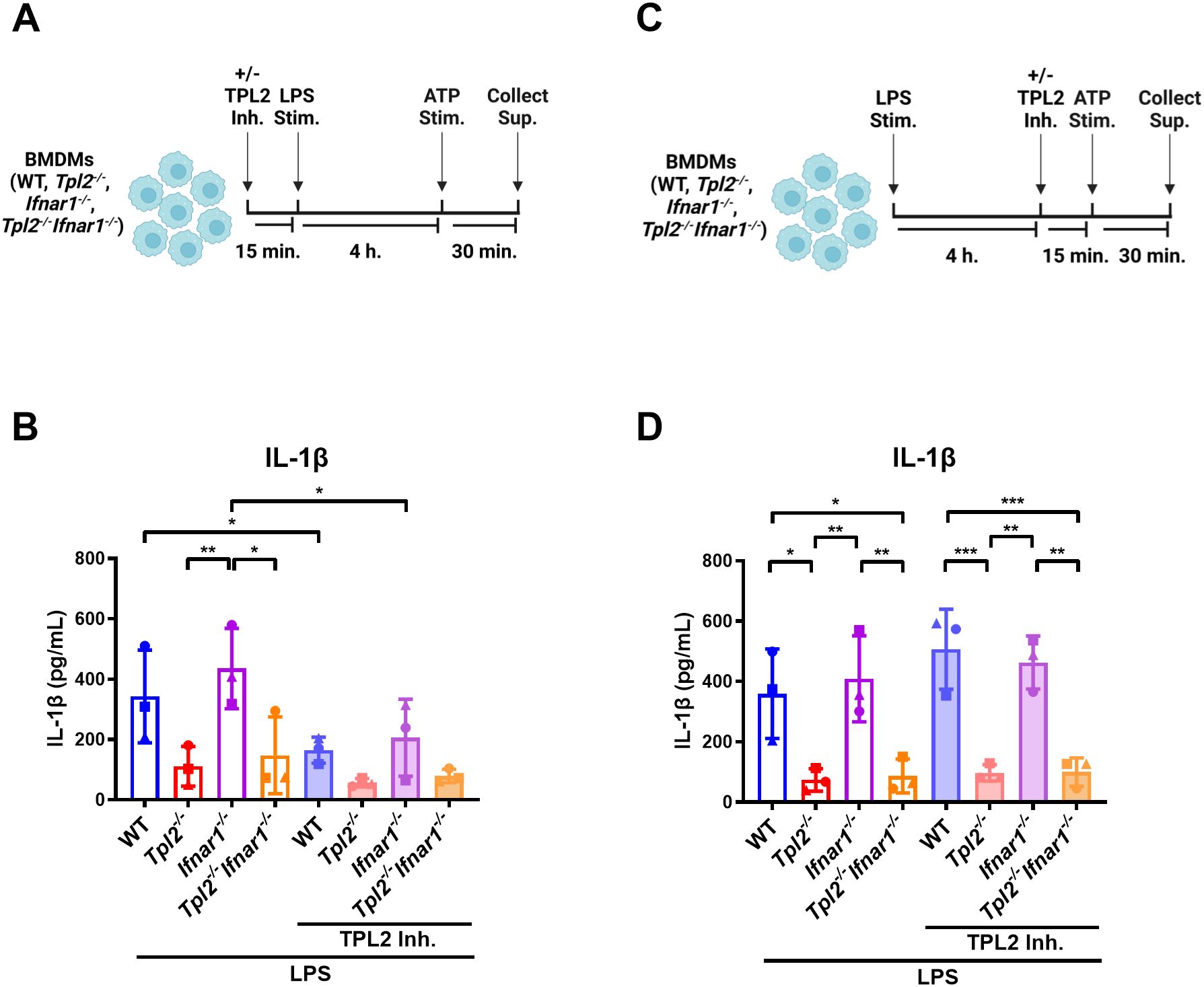

We have demonstrated that TPL2 kinase activity regulates Il1b mRNA expression during inflammasome priming; however, it is unclear if TPL2 kinase activity also affects inflammasome activation and IL-1β release. First, to evaluate the role of TPL2 in inflammasome priming, BMDMs were treated with TPL2 inhibitor 15 minutes prior to LPS stimulation (Figure 4A). Four hours later, inflammasome activation was initiated by ATP stimulation for 30 minutes (Figure 4A). Wildtype and Ifnar1-/- BMDMs treated with TPL2 inhibitor before inflammasome priming secreted significantly less IL-1β than their LPS-stimulated counterparts (Figure 4B). To assess the effect of TPL2 inhibition on inflammasome activation directly, BMDMs were stimulated with LPS for 4 hours, then treated with TPL2 inhibitor 15 minutes prior to ATP stimulation (Figure 4C). LPS-stimulated wildtype and Ifnar1-/- BMDMs treated with TPL2 inhibitor just prior to inflammasome activation exhibited no reduction in IL-1β secretion (Figure 4D), indicating that pro-IL-1β processing by the inflammasome and secretion are independent of TPL2 kinase activity. Overall, these data suggest that TPL2 kinase activity is crucial for Il1b mRNA transcription during inflammasome priming but is dispensable for inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion.

Figure 4. IL-1β secretion and inflammasome activation are not dependent on TPL2 kinase activity. (A) Experimental design depicting the role of TPL2 inhibition during inflammasome priming on IL-1β secretion. Image created using BioRender. (B) BMDMs isolated from WT, Tpl2-/-, IFNAR1-/-, and Tpl2-/-IFNAR1-/- mice were treated with and without 10 μM of TPL2 inhibitor (+/- TPL2 Inh.) for 15 minutes prior to LPS stimulation (LPS Stim.). After 4 hours of LPS stimulation, 5 mM of ATP (ATP Stim.) was added for 30 minutes and supernatant was collected to perform an IL-1β ELISA. (C) Experimental design depicting the role of TPL2 inhibition during inflammasome activation on IL-1β secretion. Image created using BioRender. (D) WT, Tpl2-/-, IFNAR1-/-, and Tpl2-/-IFNAR1-/- BMDMs were stimulated with LPS (LPS Stim.) for 4 hours, then 10 μM of TPL2 inhibitor (+/- TPL2 inh.) was added. 15 minutes after TPL2 inhibitor was added, 5 mM of ATP (ATP Stim.) was added for 30 minutes and supernatant was collected to measure IL-1β secretion by ELISA. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed. *p<0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001. Each data point represents the average of 3 individual mice. Data graphed represent means ± S.E.M. Data are from 3 independent experiments of both male and female mice.

It was previously known that IL-1β production was impaired in response to LPS when TPL2 was absent, but how TPL2 regulated other components of the inflammasome and inflammasome activation remained unclear. Our experiments reveal that TPL2 kinase activity inhibition, either pharmacologically or genetically, impaired LPS-induced Il1b mRNA synthesis. In contrast, Il18, Casp1, and Gsdmd transcription are independent of TPL2 but dependent on type I IFN signaling during inflammasome priming. Furthermore, TPL2 kinase activity is critical during inflammasome priming but is dispensable during inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion.

The absence of TPL2 causes elevated IFN-β expression (37, 38). Though it is well-established that TPL2 regulates IL-1β production, whether the increased type I IFN signaling that accompanies TPL2 ablation contributes to lower IL-1β levels has remained a standing question. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has evaluated both TPL2 and type I IFN signaling in the context of the inflammasome. Our data shows that type I IFN signaling does not contribute to lower Il1b expression during inflammasome priming (Figure 3B).

In addition to determining the role of TPL2 and type I IFNs on Il1b, we also further clarified their roles on inflammasome components during priming. Casp1 had significantly lower mRNA transcription in Ifnar1-/- and Tpl2-/-Ifnar1-/- BMDMs compared to wildtype BMDMs (Figure 1E). Conflicting reports have suggested that caspase-1 expression is either unchanged or increased after stimulation with type I IFNs and LPS during inflammasome priming (41, 42). Our data aligns with recent studies showing that type I IFN signaling promotes Casp1 mRNA expression (41, 52–54). LPS-stimulated Ifnar1-/- BMDMs synthesized significantly reduced Gsdmd mRNA relative to LPS-stimulated wildtype BMDMs (Figures 1F, 2F). The regulation of Gsdmd by type I IFNs is also in agreement with other previously published studies (41, 52). Our study also helps to clarify conflicting data regarding the role of TPL2 on Casp1 (35, 36, 54). We demonstrate that TPL2 does not regulate Casp1 or Gsdmd transcription, which is primarily responsive to type I IFN signaling.

While NF-κB contributes to both IL-1β and IL-18 production, these pro-inflammatory cytokines are regulated via different mechanisms. Il1b mRNA transcription must be induced by a pro-inflammatory signal or pathogen, and transcription is immediately increased in response to stimulation (55, 56). Conversely, Il18 is constitutively expressed at steady state (55, 56). Limited evidence indicates that ablating TPL2 kinase activity in human monocyte-derived macrophages and retinal pigment epithelial cells reduces IL-18 secretion in early inflammasome priming (35, 36). While we also found that treating wildtype BMDMs with TPL2 inhibitor modestly reduced Il18 mRNA expression (Figure 2C), there was no difference in Il18 expression in Tpl2-/- and TPL2-KD BMDMs relative to wildtype BMDMs (Figures 2C, I), suggesting that TPL2 is not a dominant regulatory factor for Il18. In murine BMDMs, type I IFN signaling is needed in conjunction with LPS stimulation for Il18 transcriptional induction, resulting in delayed Il18 synthesis relative to Il1b (49). We observed that both wildtype and Tpl2-/- BMDMs have a higher average level of Il18 after 8 hours of LPS, a time when IFN-β secretion is continuing to increase (Supplementary Figure 2G). Our data demonstrate that type I IFN signaling is an integral component of Il18 transcription, while Il1b mRNA synthesis requires TPL2 kinase activity (Figures 1B, C, 2B, C, H, I). The different regulatory mechanisms noted above likely account for the differences in TPL2 dependency observed between Il1b and Il18 expression in our study. Despite evidence that type I IFNs promote inflammasome component mRNA synthesis at 4 and 8 hours of stimulation, we did not observe a reduction in IL-1β or IL-18 secretion from Ifnar1-/- BMDMs at 8 hours (Supplementary Figures 3A, B).

In terms of clinical application, TPL2 kinase inhibition has not yet been approved for therapeutic use (57). Our data further clarify how TPL2 kinase activity contributes to inflammation by limiting Il1b transcription. Previous studies have shown that TPL2 kinase activity promotes pro-inflammatory cytokine production in both murine and human monocytes and neutrophils (6). The loss of TPL2 kinase activity reduced inflammation and pathogenesis in murine models of arthritis, colitis, and tauopathy (6, 51). In specific contexts, inhibiting TPL2 kinase activity will likely have beneficial effects, such as mitigating the damage from excessive IL-1β. However, TPL2 inhibition could potentiate other inflammatory pathways via elevated type I IFNs. Further exploration of controlled delivery of a TPL2 kinase inhibitor to specific inflammation sites could prove advantageous in inflammatory diseases caused by IL-1β overexpression, such as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome and other inflammatory diseases.

All relevant data is contained within the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The animal study was approved by University of Georgia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

DF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NP: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. WW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Research reported in this publication was supported in part by The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R21AI147003 to WW. DF was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002378 and Award Number TL1TR002382. NP was supported by funds from the UGA Foundation, Veterinary Medical Experiment Station, UGA College of Veterinary Medicine. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We would like to thank University Research and Animal Resources at UGA Coverdell rodent vivarium for their exceptional assistance and care of the animals.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1496613/full#supplementary-material

1. Gantke T, Sriskantharajah S, Ley SC. Regulation and function of TPL-2, an IkappaB kinase-regulated MAP kinase kinase kinase. Cell Res. (2011) 21:131–45. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.173

2. Lang V, Symons A, Watton SJ, Janzen J, Soneji Y, Beinke S, et al. ABIN-2 forms a ternary complex with TPL-2 and NF-kappa B1 p105 and is essential for TPL-2 protein stability. Mol Cell Biol. (2004) 24(12):5235–48. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5235-5248.2004

3. Ventura S, Cano F, Kannan Y, Breyer F, Pattison MJ, Wilson MS, et al. A20-binding inhibitor of NF-κB (ABIN) 2 negatively regulates allergic airway inflammation. J Exp Med. (2018) 215(11):2737–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170852

4. Lang V, Janzen J, Fischer GZ, Soneji Y, Beinke S, Salmeron A, et al. betaTrCP-mediated proteolysis of NF-kappaB1 p105 requires phosphorylation of p105 serines 927 and 932. Mol Cell Biol. (2003) 23:402–13. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.402-413.2003

5. Dumitru CD, Ceci JD, Tsatsanis C, Kontoyiannis D, Stamatakis K, Lin JH, et al. TNF-alpha induction by LPS is regulated posttranscriptionally via a Tpl2/ERK-dependent pathway. Cell. (2000) 103:1071–83. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00210-5

6. Senger K, Pham VC, Varfolomeev E, Hackney JA, Corzo CA, Collier J, et al. The kinase TPL2 activates ERK and p38 signaling to promote neutrophilic inflammation. Sci Signal. (2017) 10:eaah4273. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aah4273

7. Pattison MJ, Mitchell O, Flynn HR, Chen CS, Yang HT, Ben-Addi H, et al. TLR and TNF-R1 activation of the MKK3/MKK6-p38alpha axis in macrophages is mediated by TPL-2 kinase. Biochem J. (2016) 473:2845–61. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160502

8. Eliopoulos AG, Wang CC, Dumitru CD, Tsichlis PN. Tpl2 transduces CD40 and TNF signals that activate ERK and regulates IgE induction by CD40. EMBO J. (2003) 22:3855–64. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg386

9. Stafford MJ, Morrice NA, Peggie MW, Cohen P. Interleukin-1 stimulated activation of the COT catalytic subunit through the phosphorylation of Thr290 and Ser62. FEBS Lett. (2006) 580:4010–4. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.004

10. Hatziapostolou M, Koukos G, Polytarchou C, Kottakis F, Serebrennikova O, Kuliopulos A, et al. Tumor progression locus 2 mediates signal-induced increases in cytoplasmic calcium and cell migration. Sci Signal. (2011) 4:ra55. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002006

11. Israel A. The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-kappaB activation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. (2010) 2:a000158. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000158

12. Waterfield M, Jin W, Reiley W, Zhang M, Sun SC. IkappaB kinase is an essential component of the Tpl2 signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. (2004) 24:6040–8. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.6040-6048.2004

13. Tsatsanis C, Vaporidi K, Zacharioudaki V, Androulidaki A, Sykulev Y, Margioris AN, et al. Tpl2 and ERK transduce antiproliferative T cell receptor signals and inhibit transformation of chronically stimulated T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2008) 105:2987–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708381104

14. Mielke LA, Elkins KL, Wei L, Starr R, Tsichlis PN, O'Shea JJ, et al. Tumor progression locus 2 (Map3k8) is critical for host defense against Listeria monocytogenes and IL-1 beta production. J Immunol. (2009) 183:7984–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901336

15. Bauer C, Duewell P, Mayer C, Lehr HA, Fitzgerald KA, Dauer M, et al. Colitis induced in mice with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) is mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome. Gut. (2010) 59:1192–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.197822

16. Cocco M, Pellegrini C, Martinez-Banaclocha H, Giorgis M, Marini E, Costale A, et al. Development of an acrylate derivative targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Med Chem. (2017) 60:3656–71. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01624

17. Rajamaki K, Lappalainen J, Oorni K, Valimaki E, Matikainen S, Kovanen PT, et al. Cholesterol crystals activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages: a novel link between cholesterol metabolism and inflammation. PloS One. (2010) 5:e11765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011765

18. Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. (2010) 464:1357–61. doi: 10.1038/nature08938

19. Malhotra S, Costa C, Eixarch H, Keller CW, Amman L, Martinez-Banaclocha H, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome as prognostic factor and therapeutic target in primary progressive multiple sclerosis patients. Brain. (2020) 143:1414–30. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa084

20. Coll RC, Robertson AA, Chae JJ, Higgins SC, Munoz-Planillo R, Inserra MC, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nat Med. (2015) 21:248–55. doi: 10.1038/nm.3806

21. Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. (2002) 10:417–26. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00599-3

22. Piccini A, Carta S, Tassi S, Lasiglie D, Fossati G, Rubartelli A. ATP is released by monocytes stimulated with pathogen-sensing receptor ligands and induces IL-1beta and IL-18 secretion in an autocrine way. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2008) 105:8067–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709684105

23. Watson RW, Rotstein OD, Parodo J, Bitar R, Marshall JC. The IL-1 beta-converting enzyme (caspase-1) inhibits apoptosis of inflammatory neutrophils through activation of IL-1 beta. J Immunol. (1998) 161:957–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.161.2.957

24. He WT, Wan H, Hu L, Chen P, Wang X, Huang Z, et al. Gasdermin D is an executor of pyroptosis and required for interleukin-1beta secretion. Cell Res. (2015) 25:1285–98. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.139

25. Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, Speert D, et al. Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol. (2009) 183:787–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363

26. Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. (2006) 440:237–41. doi: 10.1038/nature04516

27. Petrilli V, Papin S, Dostert C, Mayor A, Martinon F, Tschopp J. Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ. (2007) 14:1583–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402195

28. Franchi L, Eigenbrod T, Nunez G. Cutting edge: TNF-alpha mediates sensitization to ATP and silica via the NLRP3 inflammasome in the absence of microbial stimulation. J Immunol. (2009) 183:792–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900173

29. Kanneganti TD, Ozoren N, Body-Malapel M, Amer A, Park JH, Franchi L, et al. Bacterial RNA and small antiviral compounds activate caspase-1 through cryopyrin/Nalp3. Nature. (2006) 440:233–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04517

30. Fink SL, Cookson BT. Caspase-1-dependent pore formation during pyroptosis leads to osmotic lysis of infected host macrophages. Cell Microbiol. (2006) 8:1812–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00751.x

31. Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature. (2015) 526:660–5. doi: 10.1038/nature15514

32. Kayagaki N, Warming S, Lamkanfi M, Vande Walle L, Louie S, Dong J, et al. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature. (2011) 479:117–21. doi: 10.1038/nature10558

33. Song N, Liu ZS, Xue W, Bai ZF, Wang QY, Dai J, et al. NLRP3 phosphorylation is an essential priming event for inflammasome activation. Mol Cell. (2017) 68:185–97 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.017

34. McKee CM, Fischer FA, Bezbradica JS, Coll RC. PHOrming the inflammasome: phosphorylation is a critical switch in inflammasome signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. (2021) 49:2495–507. doi: 10.1042/BST20200987

35. Hedl M, Abraham C. A TPL2 (MAP3K8) disease-risk polymorphism increases TPL2 expression thereby leading to increased pattern recognition receptor-initiated caspase-1 and caspase-8 activation, signalling and cytokine secretion. Gut. (2016) 65:1799–811. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308922

36. Sheu WH, Lin KH, Wang JS, Lai DW, Lee WJ, Lin FY, et al. Therapeutic potential of tpl2 (Tumor progression locus 2) inhibition on diabetic vasculopathy through the blockage of the inflammasome complex. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2021) 41:e46–62. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.315176

37. Kaiser F, Cook D, Papoutsopoulou S, Rajsbaum R, Wu X, Yang HT, et al. TPL-2 negatively regulates interferon-beta production in macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells. J Exp Med. (2009) 206:1863–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091059

38. Blair L, Pattison MJ, Chakravarty P, Papoutsopoulou S, Bakiri L, Wagner EF, et al. TPL-2 inhibits IFN-beta expression via an ERK1/2-TCF-FOS axis in TLR4-stimulated macrophages. J Immunol. (2022) 208:941–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2100213

39. McNab FW, Ewbank J, Rajsbaum R, Stavropoulos E, Martirosyan A, Redford PS, et al. TPL-2-ERK1/2 signaling promotes host resistance against intracellular bacterial infection by negative regulation of type I IFN production. J Immunol. (2013) 191:1732–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300146

40. Latha K, Jamison KF, Watford WT. Tpl2 ablation leads to hypercytokinemia and excessive cellular infiltration to the lungs during late stages of influenza infection. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:738490. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.738490

41. Diaz-Pino R, Rice GI, San Felipe D, Pepanashvili T, Kasher PR, Briggs TA, et al. Type I interferon regulates interleukin-1beta and IL-18 production and secretion in human macrophages. Life Sci Alliance. (2024) 7:e202302399. doi: 10.26508/lsa.202302399

42. Guarda G, Braun M, Staehli F, Tardivel A, Mattmann C, Forster I, et al. Type I interferon inhibits interleukin-1 production and inflammasome activation. Immunity. (2011) 34:213–23. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.006

43. Nurmi K, Silventoinen K, Keskitalo S, Rajamaki K, Kouri VP, Kinnunen M, et al. Truncating NFKB1 variants cause combined NLRP3 inflammasome activation and type I interferon signaling and predispose to necrotizing fasciitis. Cell Rep Med. (2024) 5:101503. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101503

44. Latha K, Patel Y, Rao S, Watford WT. The influenza-induced pulmonary inflammatory exudate in susceptible tpl2-deficient mice is dictated by type I IFN signaling. Inflammation. (2023) 46:322–41. doi: 10.1007/s10753-022-01736-8

45. Meurs E, Chong K, Galabru J, Thomas NS, Kerr IM, Williams BR, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase induced by interferon. Cell. (1990) 62:379–90. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90374-N

46. Soto JA, Galvez NMS, Andrade CA, Pacheco GA, Bohmwald K, Berrios RV, et al. The role of dendritic cells during infections caused by highly prevalent viruses. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1513. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01513

48. Pestka S, Krause CD, Walter MR. Interferons, interferon-like cytokines, and their receptors. Immunol Rev. (2004) 202:8–32. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00204.x

49. Verweyen E, Holzinger D, Weinhage T, Hinze C, Wittkowski H, Pickkers P, et al. Synergistic signaling of TLR and IFNalpha/beta facilitates escape of IL-18 expression from endotoxin tolerance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2020) 201:526–39. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0659OC

50. Lebratti T, Lim YS, Cofie A, Andhey P, Jiang X, Scott J, et al. A sustained type I IFN-neutrophil-IL-18 axis drives pathology during mucosal viral infection. Elife. (2021) 10:e65762. doi: 10.7554/eLife.65762.sa2

51. Wang Y, Wu T, Tsai MC, Rezzonico MG, Abdel-Haleem AM, Xie L, et al. TPL2 kinase activity regulates microglial inflammatory responses and promotes neurodegeneration in tauopathy mice. Elife. (2023) 12:e83451. doi: 10.7554/eLife.83451.sa2

52. Hong SM, Lee J, Jang SG, Lee J, Cho ML, Kwok SK, et al. Type I interferon increases inflammasomes associated pyroptosis in the salivary glands of patients with primary sjogren's syndrome. Immune Netw. (2020) 20:e39. doi: 10.4110/in.2020.20.e39

53. Liu J, Berthier CC, Kahlenberg JM. Enhanced inflammasome activity in systemic lupus erythematosus is mediated via type I interferon-induced up-regulation of interferon regulatory factor 1. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2017) 69:1840–9. doi: 10.1002/art.40166

54. Nanda SK, Prescott AR, Figueras-Vadillo C, Cohen P. IKKbeta is required for the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. EMBO Rep. (2021) 22:e50743. doi: 10.15252/embr.202050743

55. Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. (2009) 27:519–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612

56. Cornut M, Bourdonnay E, Henry T. Transcriptional regulation of inflammasomes. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21(21):8087. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218087

Keywords: TPL2, Tpl2 kinase, NLRP3 inflammasome, interferons, type I IFN, IL-1b

Citation: Fahey DL, Patel N and Watford WT (2025) TPL2 kinase activity is required for Il1b transcription during LPS priming but dispensable for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Front. Immunol. 16:1496613. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1496613

Received: 14 September 2024; Accepted: 19 February 2025;

Published: 18 March 2025.

Edited by:

Michael V. Volin, Midwestern University, United StatesReviewed by:

Ankit Malik, University of North Carolina System, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Fahey, Patel and Watford. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wendy T. Watford, d2F0Zm9yZHdAdWdhLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.