Abstract

The association between inflammation with depression and suicide has prompted many investigations of the potential contributors to inflammatory pathology in these psychiatric illnesses. However, a distillation of diverse clinical findings into an integrated framework of the possible involvement of major physiological processes in the elicitation of pathological inflammation in depression and suicide has not yet been explored. Therefore, this review aims to provide a concise synthesis of notable clinical correlates of inflammatory pathology in subjects with various depressive and suicidal clinical subtypes into a mechanistic framework, which includes aberrant immune activation, deregulated neuroendocrine signaling, and impaired host-microbe interaction. These issues are of significant research interest as their possible interplays might be involved in the development of distinct subtypes of depression and suicide. We conclude the review with discussion of a pathway-focused therapeutic approach to address inflammatory pathology in these psychiatric illnesses within the realm of personalized care for affected patients.

1 Pathobiology of depression and suicide

Investigation of the complex pathobiology of depression and suicide, including both suicidal ideation (SI) and behavior (SB), is pivotal to achieve advances in diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of these psychiatric illnesses. There is a variety of neurobiological hypotheses of depression and SI/SB, often involving abnormalities from multiple areas of biology with ramified interactions (1–5). Currently, neurobiological hallmarks of depression and SI/SB are of immense research interest as no current markers of such origins are of sufficient clinical utility (6–12). Moreover, a thorough understanding of molecular and cellular pathways of these two conditions can be hindered by their complex behavioral manifestations, interaction with psychosocial, cultural, and environmental factors, diverse patient subpopulations, and the presence of somatic and psychiatric comorbidities (10, 13–17).

Recent evidence of associations between inflammatory mediators with various neurological and psychiatric illnesses, including depression and suicide, has highlighted the important role of pathological inflammation in the development of these conditions (18–26). Therefore, this review aims to categorically distill major clinical observations of the presence of inflammation in depression and SI/SB into a putative etiological framework, which involves crosstalks among immunological abnormalities, neurometabolic impairment, and dysregulated host-microbe interactions.

2 Inflammatory hallmarks of depression and suicide

The etiological connection between inflammation, depression, and suicide was first suggested by the increased risk of these neuropsychiatric conditions in patients with inflammatory somatic illnesses (27). Depressive symptoms and SI/SB were also observed in some patients receiving immunotherapy that elicits robust inflammatory responses, such as IFN-α (28). More importantly, the presence of focal inflammation in depression- and SI/SB-associated brain structures, such as the pre-frontal and anterior cingulate cortex (29, 30), further supported the involvement of pathological inflammation in these psychiatric illnesses. Here, we aim to synthesize notable clinical observations of diverse inflammatory manifestations in depressed and suicidal patients into specific inflammatory phenotypes of different clinical subtypes of these neuropsychiatric illnesses.

2.1 Depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is characterized by the persistent presence of depressed mood, reduced interest in pleasure-seeking activities, feelings of guilt/worthlessness, low energy, poor concentration, alterations in appetite/sleep/psychomotor functions, or suicidal thoughts. MDD has been the primary focus of studies of inflammation in patients with depressive symptoms. Notably, (epi)genetic as well as proteomic alterations of circulating and central nervous system (CNS)-specific inflammatory mediators were detected in MDD patients (Table 1). In this regard, polymorphisms in several innate immunity-associated inflammatory cytokines, such as CCL2, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, were correlated with more severe MDD symptoms (31). Conversely, a unique variant in IL-6R was also linked to reduced risk of depression and/or psychosis (32). In agreement with these genetic analyses, protein levels of selected innate immunity-associated inflammatory cytokines, including CCL2, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-18, were elevated in sera of MDD patients compared to healthy individuals (33). Importantly, early MDD-onset age was linked to a systemic pro-inflammatory state (34), driven by IL-1β and TNF-α.

Table 1

| Reference | Neuropsychiatric condition | Patient population | Study method/ Tissue type | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bufalino et al. (31) | MDD | 125 MDD vs 275 HC (2 studies) | Systematic review | CCL2 genetic variants were linked to MDD |

| Bufalino et al. (31) | MDD | 576 MDD vs 706 HC (4 studies) | Systematic review | IL-1β genetic variants were linked to MDD |

| Bufalino et al. (31) | MDD | 289 MDD vs 468 HC (2 studies) | Systematic review | IL-6 genetic variants were linked to MDD |

| Bufalino et al. (31) | MDD | 140 MDD vs 488 HC (2 studies) | Systematic review | TNF-α genetic variants were linked to MDD |

| Kohler et al. (33) | MDD | 3212 MDD vs 2798 HC (82 studies) | Meta-analysis/Blood | CCL2/TNF-α/IL-6/IL-12/IL-18, but not IL-17, were elevated in MDD sera |

| Anzolin et al. (34) | MDD | 234 MDD | Proteomics/Blood | Higher serum IL-1β/TNF-α levels were linked to early MDD onset |

| Myint et al. (35) | MDD | 40 MDD vs 80 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum IFN-γ/IL-4 ratio in MDD |

| Davami et al. (36) | MDD | 41 MDD vs 40 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum IL-17 in MDD |

| Mahajan et al. (37) | MDD | 23 MDD vs 23 HC | Proteomics/Brain | Increased CCL2 in hippocampal dentate gyrus of MDD |

| Enache et al. (38) | MDD | 66 MDD vs 149 HC (3 studies) | Meta-analysis/CSF | Increased CSF IL-6 in MDD |

| Rush et al. (39) | Melancholic MDD | 55 Melancholic MDD vs 26 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum IL-6 in melancholic MDD |

| Sowa-Kucma et al. (40) | Melancholic MDD | 74 Melancholic vs 37 Non-melancholic MDD vs 50 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum soluble IL-6R in melancholic MDD |

| Yang et al. (41) | Melancholic MDD | 25 Melancholic vs 17 Non-melancholic MDD | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum IL-1β in melancholic MDD |

| Dionisie et al. (42) | Bipolar MDD | 34 Bipolar vs 83 unipolar MDD | Proteomics/Blood | Higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in bipolar MDD |

| Mao et al. (43) | Bipolar MDD | 61 Bipolar vs 64 unipolar MDD | Proteomics/Blood | Decreased serum TNF-α in bipolar MDD |

| Brunoni et al. (44) | Bipolar MDD | 59 Bipolar vs 245 unipolar MDD | Proteomics/Blood | Reduced serum IL-1β/TNF-α/IL-12 and increased serum IL-6/IL-18 in bipolar MDD |

| Poletti et al. (45) | Bipolar MDD | 76 Bipolar MDD | Proteomics/Blood | Higher serum IL-6 was linked to poor cognition in bipolar MDD |

| Su et al. (46) | Bipolar MDD | 10 Bipolar vs 18 unipolar MDD vs 21 HC | Proteomics/Blood | No differences in serum IL-6/TNF-α among study groups |

| Yoon et al. (47) | Atypical depression | 35 Atypical depression vs 70 MDD | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum IL-2, but not IL-6/TNF-α, in atypical depression |

| Lamers et al. (48) | Atypical depression | 122 Atypical depression vs 111 MDD vs 543 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α in atypical depression |

| Song et al. (49) | SAD | 20 SAD vs 20 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased IL-1β/TNF-α/IFN-γ production by blood cells in SAD could be reversed by phototherapy |

| Leu et al. (50) | SAD | 15 SAD vs 15 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum IL-6 in SAD could not be reversed by phototherapy |

| Corwin et al. (51) | PPD | 26 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum IL-1β was linked to PPD |

| Leu et al. (52) | PPD | 45 PPD vs 251 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum CRP and IL-6 in PPD |

| Nicoloro-SantaBarbara et al. (54) | PPD | 16 PPD vs 17 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased NK-FB activation was linked to PPD 2-3 years after delivery |

| Sowa-Kucma et al. (40) | TRD | 42 TRD vs 72 non-TRD vs 50 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum soluble IL-6R in TRD |

| Strawbridge et al. (56) | TRD | 36 TRD vs 36 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum IL-6/IL-8/TNF-α/CRP in TRD |

| Mendlewicz et al. (57) | TRD | 372 TRD | Genetics/Blood | COX-2 genetic variant was linked to TRD |

| Aguglia et al. (22) | SA | 133 high-lethality vs 99 low-lethality SA | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum CRP were linked to SA lethality |

| Lindqvist et al. (61) | SA | 63 SA vs 47 HC | Proteomics/CSF | Increased CSF IL-6 in SA |

| Janelidze et al. (62) | SA | 47 SA vs 17 non-suicidal MDD vs 16 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum IL-6 and TNF-α in SA |

| Kim et al. (63) | SA | 204 SA with MDD vs 97 non-suicidal MDD | Proteomics/Blood | TNF-α genetic variant was linked to SA with MDD |

| Kim et al. (64) | SA | 36 SA with MDD vs 33 non-suicidal MDD vs 40 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum IL-6 in non-suicidal MDD |

| Isung et al. (65) | SA | 43 SA vs 40 HC | Proteomics/CSF | No difference in CSF IL-6 between study groups |

| Lindqvist et al. (66) | SA | 124 SA | Proteomics/CSF | Increased CSF IL-6 was linked to SA lethality |

| Isung et al. (67) | SA | 58 SA | Proteomics/Blood-CSF | Increased serum/CSF IL6 were linked to SA lethality |

| Schiavone et al. (71) | SA | 26 SA vs 10 HC | Proteomics/Brain | Increased cortical IL-6 in SA |

| Pandey et al. (72) | SA | 24 SA with MDD vs 24 HC | Proteomics/Brain | Increased IL-1β/IL-6/TNF-α and reduced IL-1RA/IL-10 in prefrontal cortex of SA |

| Torres-Platas et al. (74) | SA | 16 SA with MDD vs 14 HC | Genetics/Brain | Increased CCL2/IBA-1 mRNA in dorsal cingulate cortex of SA |

| Janelidze et al. (75) | SA | 137 SA vs 43 HC | Proteomics/Brain | Decreased CSF CCL2/TARC/MIP-1β in SA |

| Bokor et al. (77) | SA | 1761 HC | Genetics/Saliva | IL-6 genetic variants were linked to increased lifetime SA risk |

| Knowles et al. (78) | SA | 1882 HC | Genetics/Blood | IL-8 represents a female-specific genetic risk for SA, but not SI |

| Melhem et al. (79) | SA | 38 SA vs 40 SI vs 37 HC | Genetics/Proteomics/Blood | Increased serum CRP and TNF-α mRNA in SA compared to SI |

| Vasupanrajit et al. (80) | SA | 4043 SA/SI vs 12377 HC (59 studies) | Meta-analysis | Inflammation-related nitro-oxidative stress was strongly related to SA than SI |

| O'Donovan et al. (76) | SI | 124 SI with MDD vs 124 HC | Proteomics/Blood | Increased inflammatory index (composite of TNF-α /IL-6/CRP/IL-10) in SI with MDD |

| Bokor et al. (77) | SI | 1761 HC | Genetics/Saliva | IL-6 genetic variants were linked to increased current SI |

Inflammatory features of depressive and suicidal clinical subtypes.

CRP, C-reactive protein; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HC, healthy control; MDD, major depressive disorder; PPD, post-partum depression; SA, suicide attempt; SAD, seasonal affective disorder; SI, suicidal ideation; TRD, treatment-resistant depression.

Besides alterations that are closely related to innate-immune mediated inflammation, the adaptive immunity-associated inflammatory cytokine, IFN-γ, has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of depression, with increased expression of serum IFN-γ/IL-4 ratio in MDD patients (35). Another T lymphocyte-associated inflammatory cytokine, IL-17, was reportedly elevated in MDD blood samples, with some discrepancies between reports (33, 36). While the majority of MDD studies focused on peripheral inflammatory markers, neuroinflammation in MDD has also been documented. In this regard, CCL2 expression in brain parenchyma was elevated in post-mortem brain tissues of MDD patients (37). Additionally, IL-6 level in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were increased in MDD subjects (38).

While the aforementioned clinical findings suggest that prototypical inflammation is prominently present in MDD, some variants of this neuropsychiatric condition might exhibit distinct inflammatory profiles (Table 1). In this regard, melancholic MDD was associated with elevated serum IL-1β, IL-6, and soluble IL-6R levels (39–41). Furthermore, selected inflammatory alterations were uniquely linked to bipolar MDD compared to unipolar MDD. For example, increased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), an inflammatory index, has been proposed as a diagnostic parameter to distinguish bipolar from unipolar MDD (42). Other indicators to distinguish bipolar from unipolar MDD are reduced serum levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-12, and increased serum levels of IL-6 and IL-18 (43, 44). Of mechanistic importance, increased serum IL-6 was linked to poorer cognition in bipolar MDD (45). It’s worth noting that some unique inflammatory features of bipolar MDD have been disputed. For example, no significant differences in serum TNF-α and IL-6 levels were observed between bipolar and unipolar MDD (46). These differences might be related to disease activity at the time of inflammatory marker measurements. Hence, further longitudinal analyses of fluctuations in inflammatory markers of MDD patients might provide important insights on the role of specific inflammatory pathways in the onset of manic episodes.

Similar to MDD, inflammatory pathology has been observed in other depression subtypes (Table 1). In atypical depression, circulating inflammatory mediators, such as IL-2, C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6, and TNF-α, were significantly elevated, although differences in IL-6 and TNF-α were not consistently observed (47, 48). In seasonal affective disorder (SAD), production of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ in cultures of circulating immune cells was elevated, which could be reversed by phototherapy (49). Interestingly, serum IL-6 was also elevated in SAD patients but could not be normalized by this therapeutic approach (50), suggesting distinct effects of this treatment on different inflammatory mediators. In post-partum depression (PPD), depressive symptoms were associated with increased expression of serum CRP, IL-1β, and IL-6 (51, 52). Notably, elevated inflammation was detected as early as 1-3 days after childbirth (53) and their persistence for several years after delivery was linked to PPD (54), highlighting the possible initiating role of inflammation in this type of depression as well as its long-lasting epigenetic impact.

Treatment responsiveness represents a therapeutic challenge for patients with depression (55), partly owing to the delayed impact of anti-depressants that occur only after an extended treatment period (of at least one month). Consequentially, pre-treatment biomarkers that could predict therapeutic efficacy of anti-depressants are of immense clinical interest. In this regard, several predictors of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) have been proposed, including elevated serum levels of IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, soluble IL-6R, and CRP (40, 56) or polymorphisms in COX-2 (57). However, some conflicting findings regarding correlations between changes in inflammatory markers and antidepressant response to ketamine in TRD exist (58), which might be explained by the heterogeneity of this patient population. In fact, anti-inflammatory therapy was only effective in a subset of TRD patients with elevated expression of inflammatory mediators (59).

2.2 Suicidal ideation and behavior

The interconnected pathobiology of depression and suicide suggests that overlapping inflammatory signatures might exist between these two conditions. However, few studies have examined potential differences in inflammatory features between suicidal depressed and suicidal non-depressed subjects (24). It has been hypothesized that subjects at risk for suicide might be biologically distinguishable from depressed individuals without such risk by a heightened pro-inflammatory state, characterized by elevated serum IL-6 (60). Nevertheless, a consensus on unique and/or shared inflammatory features between depression and SI/SB has not been reached, given the diverse approaches to patient stratification in studies of these two conditions. As such, mechanistic insights from clinical correlates must be carefully interpreted. The following section aims to highlight inflammatory changes in different suicidal subtypes, while acknowledging the possible coexistence of depressive symptoms in affected individuals.

In subjects who made an suicidal attempt (SA), increased serum levels of IL-6 and TNF-α, elevated CSF levels of IL-6, and TNF-α polymorphisms were observed (61–63). However, differences in IL-6 in CSF and sera could not be confirmed by other studies (64, 65), possibly due to confounding demographic factors, such as patient stratification and/or medication status. Interestingly, the lethality of SA was reportedly associated with specific inflammatory chemokines/cytokines in the CSF (66) as well as serum CRP and IL-6 (a stimulator of hepatic CRP synthesis) (22, 67). Mechanistically, increased expression of inflammatory markers might predispose subjects with specific behavioral traits, such as impulsivity, aggression, and hostility (15, 68–70), to violent SA.

Besides fluid-based biomarker studies, post-mortem brain tissue analysis has provided important insights on the possible association between neuroinflammation and SA. For example, cortical IL-6 was upregulated in asphytic suicidal subjects (71). Depressed suicidal patients also showed elevated expression of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) and reduced levels of anti-inflammatory mediators (IL-1RA and IL-10) in the prefrontal cortex (72). Interestingly, aberrant epigenetic regulation might account for the elevated expression of TNF-α in the brains of subjects with SA (73). Increased CCL2 mRNA expression were also noted in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex of suicide victims, which was correlated with IBA-1-expressing brain macrophage accumulation (74). However, decreased macrophage-attracting chemokines, including CCL2, TARC, and MIP-1β, were observed in another study (75).

In MDD subjects with SI, a higher systemic inflammatory score was observed compared to healthy controls (76). Furthermore, IL-6 genetic variants appeared to interact with childhood adversities or recent life stress to influence lifetime risk of SA and current SI (77). However, different magnitudes of inflammatory changes might distinguish SA from SI. For example, the chemokine IL-8 represented a female-specific genetic risk factor for SA but not SI (78). Increased serum CRP and TNF-α mRNA from blood cells were also observed in SA compared to SI (79). Finally, inflammation-related nitro-oxidative stress was more strongly related to SA than SI (80).

While these observations need to be further validated with detailed consideration of patient characteristics and other confounders, they have prompted a provocative hypothesis that dynamic changes in inflammation might underlie the development of SI/SA and progression from the former to the latter. Furthermore, inflammatory pathology has also been documented in various psychiatric illnesses, suggesting the possible existence of a common inflammatory pathway among behavioral disorders.

3 Contributors to inflammation in depression and suicide

While the relative contribution of each inflammatory mediator to distinct pathological manifestations of depression and SI/SB needs to be further examined, abnormalities in major inflammation-associated physiological processes have been observed in these conditions. Notably, immunological and neuroendocrinological abnormalities have been linked to inflammatory pathology in depression and suicide. Furthermore, dysregulated host-microbe interaction has recently emerged as another major contributor to inflammation in these conditions. While we do not exclude the possible crosstalks between these signaling axes with other factors, such as those of (epi)genetic and environmental origins, the following sections will propose a mechanistic synthesis of clinical evidence focusing on abnormalities in these three major physiological processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Proposed etiological framework of inflammation in depression and suicide. Inflammation in depression and suicide might result from overactivation of the neuroimmune system, with abnormalities in the function/distribution of various circulating adaptive and innate immune cell as well as possible alterations in activation profiles and concentration of cellular components of the central nervous system (CNS), including astrocytes, microglia, and infiltrated macrophages. Furthermore, alterations in several neurometabolic axes, such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) pathway, melatonin signaling, kynurenine metabolism, and oxidative stress, might also contribute to this pathology. Lastly, dysregulated host-microbe interaction (dysbiosis) may heighten the production of inflammatory mediators in these neuropsychiatric conditions.

3.1 Aberrant activation of the immune system

As a major source of inflammatory mediators, the immune system has long been implicated in the development of inflammatory pathology in depression and suicide (23, 24, 81). Peripheral perturbations in various immune cell subsets have been observed in these conditions. For example, reduced function and numbers of T cells and natural killer cells were linked to MDD (82). However, expansions of various T-helper subtypes, including Th-17 cells, were also detected in depressed patients (83), suggesting that temporally distinct immune activation profiles might exist during the progression of this psychiatric illness. Regarding innate immunity-related changes, increased numbers of blood monocytes and frequencies of neutrophils were observed in depressed subjects (60, 84). Notably, a heightened systemic accumulation of these cells might distinguish subjects with increased suicide risk from non-suicidal depressed patients (60).

Besides alterations in peripheral immunity, abnormal activation of microglia and macrophages in the CNS has also been examined in the context of depression and suicide. However, observations of gliosis-related changes were inconsistent in depressed and suicidal patients (38), possibly due to the impact of death on glial cell reactivity as well as the different types of tissue-sampling methods (brain regions, cerebrospinal fluid vs. brain parenchyma). Alternatively, gliosis might have resulted from an influx of peripheral monocytes/macrophages. The latter viewpoint is supported by observations of higher concentrations of blood vessels surrounded by macrophages in the anterior cingulate cortex of depressed suicidal patients, evidenced by increased IBA-1 and CD45 mRNA expression (74). Increased activation markers of astrocytes have also been implicated in suicide and depression. For instance, increased circulating levels of S100B and CSF levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) were observed in depressed subjects (85, 86), while reactive astrocytosis with hypertrophic morphology was noted in the white matter of the anterior cingulate cortex of depressed suicide completers (87).

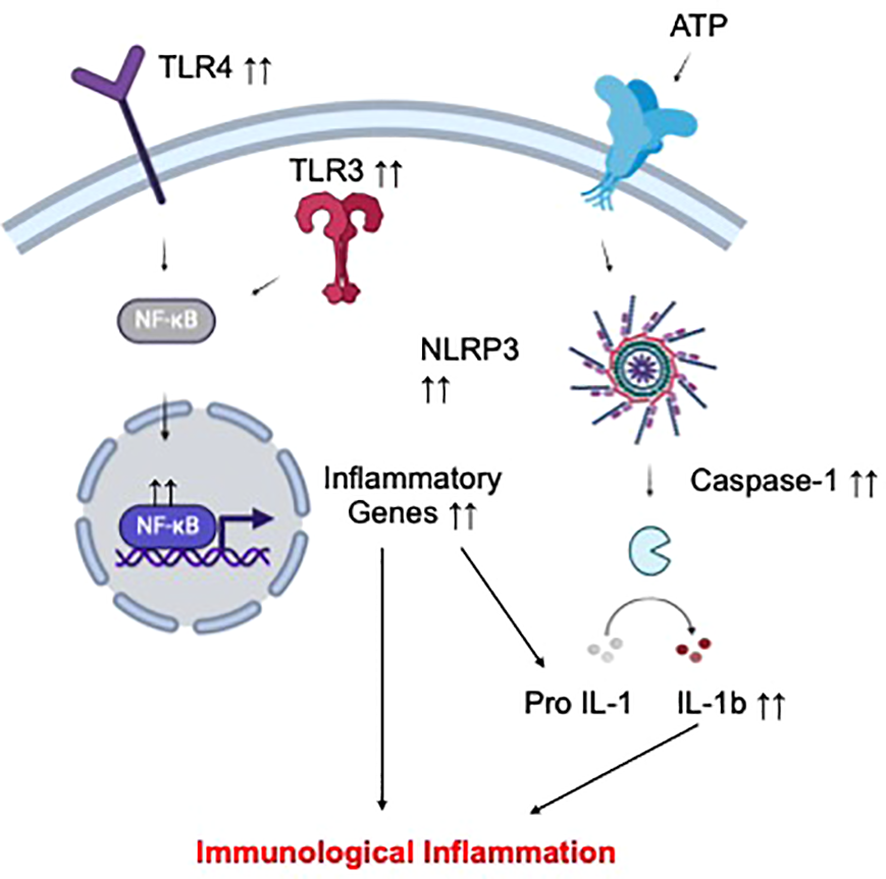

Altogether, the clinical findings above highlight hyper-activation of the peripheral and CNS immune repertoires as a root cause of pathological inflammation in depression and suicide. Mechanistically, exuberant inflammatory responses of peripheral and CNS immune cells in the context of these psychiatric conditions might be mediated by abnormally activated pro-inflammatory signaling cascades (Figure 2). In this regard, increased expression of various molecular regulators of the toll-like receptors (TLR)/nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-KB) pathway have been associated with depression and suicide. For example, increased TLR4 expression in peripheral immune cells was linked to MDD symptoms while elevated TLR3/TLR4 expression was observed in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of depressed suicidal patients (88, 89). NF-KB and the expression of its related genes were reportedly higher in depressed adolescents and adults (90, 91). Another master regulator of inflammation, the nod-like receptor pyrin-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, has also been implicated in these neuropsychiatric conditions (92). For example, mRNA expression of NLRP3 and its related genes (the adaptor apoptosis-associated speck-like protein ASC, caspase-1) in peripheral immune cells were increased in MDD patients compared to healthy controls (93, 94). Specific DNA methylation pattern of NLRP3 in depressed brains was also linked to depression-associated neuroanatomical changes (cortical thickness) and neuroinflammatory processes (95). In an analysis of post-mortem brain samples from depressed suicidal patients, evidence of hyperactive NLRP3 inflammasome (elevated protein and mRNA expression of NLRP3, Caspase-1, and the inflammasome adaptor protein ASC) was also observed (96). Importantly, two anti-depressants, amitriptyline (97) and ketamine (98), could respectively reduce NLRP3 and NK-FB expressive, and consequentially, inflammatory cytokine production in peripheral blood cells from MDD subjects. Collectively, these findings provide further mechanistic support for the involvement of pro-inflammatory signaling cascades in the orchestration of immunological inflammation in MDD.

Figure 2

Proposed mechanism of immunological inflammation in depression and suicide. Increased activation status of different circulating and CNS immune cell subsets has been implicated in depression and suicide. Such hyperinflammatory phenotype of these cells might result from elevated signal transduction via selected pro-inflammatory pathways, including those of TLR-NFKB and the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to overproduction of inflammatory cytokines, and ultimately, peripheral and CNS inflammation.

3.2 Impaired neurometabolic signaling

Quantitative analyses of clinical specimens from depressed and suicidal subjects revealed changes in the concentrations of various metabolites and hormones compared to healthy individuals. Importantly, these bioactive molecules point to the potential disruption of homeostatic signaling of several neuroendocrine systems as another important contributor to pathological inflammation in these neuropsychiatric illnesses (Figure 3). Their putative mechanistic contributions to pathological inflammation in depression and suicide will be detailed in this section.

Figure 3

Proposed mechanism of neuroendocrinological inflammation in depression and suicide. Several neuroendocrine pathways might contribute to the inflammatory pathology of depression and suicide by distinct pathways. (A) HPA dysfunction-induced hypercortisolemia might result in glucocorticoid receptor (GR) downregulation/desensitization and activation of non-canonical inflammation signaling of cortisol. (B) Impaired melatonin production might dampen its downstream anti-inflammatory properties. (C) Primary inflammatory insult might induce the divergence of tryptophan’s catabolic fate away from serotonin synthesis and towards neurotoxic kynurenine metabolism, and ultimately, secondary inflammation. (D) Oxidative stress might result in mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired antioxidant defense, causing neurotoxicity and inflammation.

Abnormalities in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a major stress response system, have been noted in depression and suicide, regardless of the presence of any other psychiatric conditions (99). This signaling pathway consists of various neuroendocrine hormones, such as corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and cortisol, which are released in response to stress. In this regard, more than 40% of depressed patients exhibited hypercortisolemia, increased CRH production or reduced ACTH release (100), with hypercortisolemia being associated with MDD severity and MDD-associated psychosis (101). Similarly, increased cortisol response has been observed in depressed suicidal subjects (102). Age-dependent hypercortisolemia were also linked to SA (103). Mechanistically, hypercortisolemia might represent a compensatory response to reduced glucocorticoid receptor (GR) expression. In fact, reduced hippocampal GR expression was observed in brain specimens of abused suicidal patients and linked to early-life trauma-induced epigenetic changes (methylation) in the NR3C1 gene (104). Alternatively, hypercortisolemia might desensitize GR signaling (105), thereby increasing the propensity for non-canonical inflammatory signaling of cortisol (Figure 3A). In fact, reduced GR-α expression in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala of suicide victims was linked to higher expression of CRP and TNF-α (106).

Beside HPA dysfunction, perturbations in the signaling pathway of melatonin, a pineal gland-derived hormone that regulates the sleep-wakefulness cycle, have been observed in depression and suicide. Specifically, single-nucleotide polymorphism of the melatonin receptor in the brain was associated with depression (107), while changes in melatonin levels and production patterns was documented in various depression subtypes (108). Decreased melatonin concentrations in the pineal gland was also observed in suicide victims (109). A connection between melatonin dysregulation and inflammatory pathology in depression and suicide might be related to the compromised anti-inflammatory properties of this hormone on innate immune cells (110) (Figure 3B).

Another prominent hypothesis of depression and suicide development focuses on dysregulated kynurenine metabolism. This metabolite of the tryptophan catabolic pathway represents a rate-limiting step in the diversion of tryptophan availability from the synthesis of serotonin, a neuroprotective neurotransmitter in depression. In fact, acute tryptophan deprivation might be able to trigger clinical symptoms of depression (111). Additionally, kynurenine pathway activation was observed in various forms of depression (112, 113) and correlated with depression severity (114). Increased toxic metabolites of the kynurenine pathway, such as 3-hydroxykynurenine, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, and quinolinic acid, have been associated with reduced cortical thickness in MDD (115) or linked to MDD development (116, 117). In suicidal patients, reduced serotonin metabolism was linked to possible dysregulation of kynurenine signaling (118). In fact, positive correlations between the cytokine activation marker neopterin with the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio and between abnormally elevated quinolinic acid concentration and increased inflammatory potential have been reported (119, 120). Elevated serum concentration of kynurenine was also observed in MDD patients with SA (121). Of mechanistic interest, a bidirectional interaction between kynurenine metabolism and inflammation might occur in depression and suicide. While kynurenine catabolic activation might be induced by inflammatory signals, toxic metabolites of this pathway might cause neuronal injuries and secondary inflammatory response, thereby propagating this vicious interactome (Figure 3C).

Finally, oxidative stress has been implicated in depression and suicide (23, 24, 122). Reduced antioxidant levels and/or increased oxidative stress markers were observed in brain specimens and blood samples of depressed subjects (122, 123). In suicide pathophysiology, increased NADPH oxidase was associated with SI, while increased nitro-oxidative stress markers and reduced antioxidant levels were linked to SA (80, 124). Mechanistically, oxidative stress can damage the mitochondria, triggering inflammatory reactions (Figure 3D). In fact, concomitant increases in inflammation and oxidative stress were observed in maltreated children, who developed higher risk of depression in adulthood (125). Reduced circulating antioxidants in depressed patients were also linked to elevated serum inflammatory cytokines (126). Furthermore, the high-oxygen demand of the CNS renders this tissue highly susceptible to oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial damage and reduced antioxidant defense, followed by the vicious cycle of elevated neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity in vulnerable brain regions, which underlies various behavioral pathologies of depression and suicide development.

3.3 Dysregulated host-microbe interaction

Alterations in the microbiome have recently emerged as a novel pathology of various neuropsychiatric illnesses, including depression and suicide (127, 128). In depressed subjects, the most commonly observed alterations in the microbiome are related to those of the gastrointestinal compartment. In this regard, most studies found changes in beta-diversity (dissimilarity between depressed and control subjects) as well as alterations in abundance (the concentrations of specific microbes) of selected microbial phyla (Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria), families (Rikenellaceaea, Enterobacteriaceae, and Ruminococcaeceae), and geniuses (Eggerthella, Alistipes, Parabacteroides, Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, Veillonella, Flavonifractor, Streptococcus and Faecalibacterium) in fecal samples of MDD patients compared to health controls (129). In other studies, alterations in abundance, but not diversity, of selected salivary microbial genera (Prevotella, Haemophilus, Rothia, Treponema, Schaalia, Neisseria, Solobacterium, Lepotrichia, Fusobacterium, and Veillonella) and species (Lachnoanaerobaculum orale, Fusobacterium periodonticum, and Mobiluncus Mulieris) were associated with depressive symptoms (130, 131). In suicidal MDD patients, six microbial taxa were linked to suicidal behaviors (positive associations: Hungatella and Fusicatenibacter, negative associations: Butyricicoccus, Clostridium, Parabacteroides merdae, and Desulfovibrio piger) (132). Furthermore, SI was reportedly associated with changes in salivary abundance of various microbial genera (Veillonella, Streptococcus, Prevotella, Rothia, Alloprevotella, Granulicatella, Porphyromonas, Peptostreptococcus, Stomatobaculum, Gemella, and Solobacterium) and species (Streptococcus oralis, Prevotella melaninogenica, Fusobacterium periodoncitum, Rothia mucilagniosa, Graulicatella adiacens, Streptococcus parasanguinis, Prevotella nanciensis, Solobacterium moorei, Dialister pneumosintes, Peptoanaerobacter stomatis, Actinomyces naeslundii, Bacteroides dorei, and Fusobacterium naviforme) (133). Last but not least, increased laxative misuse, which is associated with gastrointestinal microbial dysbiosis, were linked to a history of SA (134).

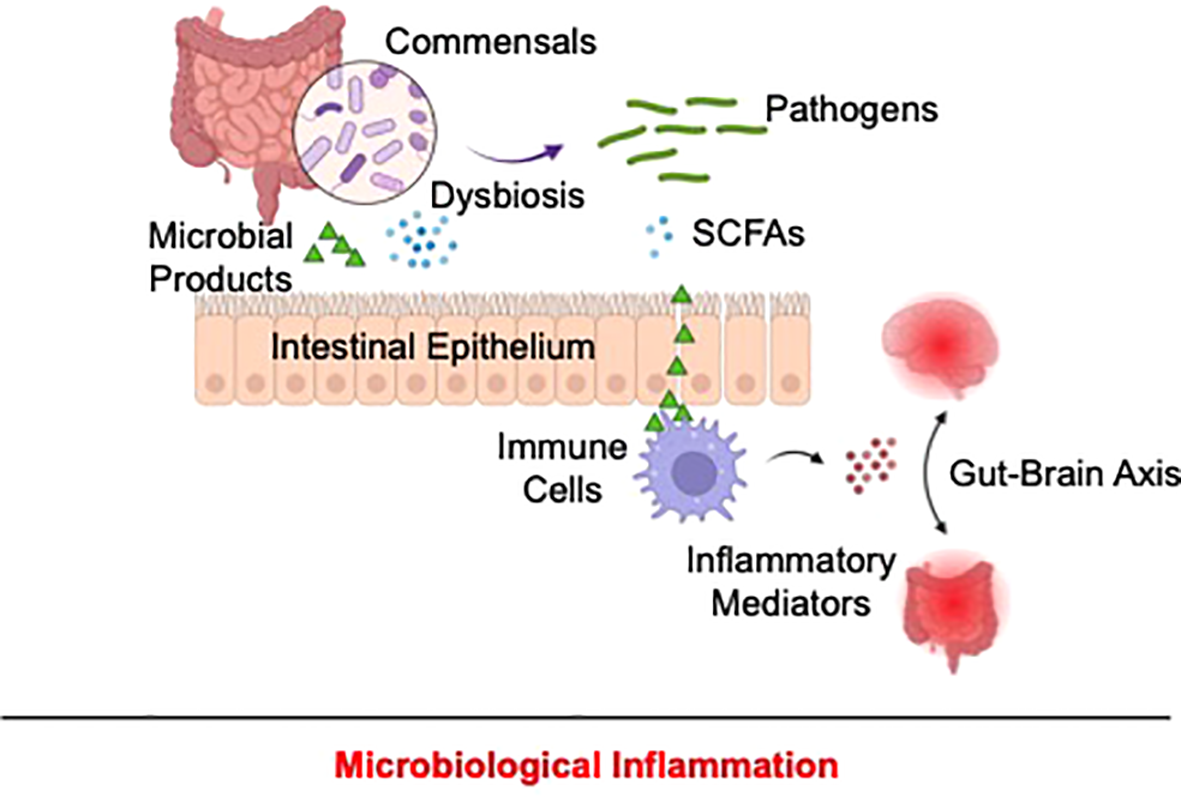

Mechanistically, microbial dysbiosis might contribute to inflammatory pathology by triggering the loss of intestinal barrier integrity, exposing intestinal immune cells to inflammatory environmental stimuli. In fact, higher depressive symptoms were reportedly associated with increased intestinal permeability in cancer patients (135). Reduced zonulin expression, a biomarker of increased intestinal permeability, was also observed in patients with MDD or those with SA (136). Furthermore, compositional changes in commensals, as a result of dysbiosis, might trigger excessive release of microbe-associated inflammatory stimuli (137) and reduce the availability of anti-inflammatory microbial products, such as short-chain fatty acids (138), leading to unrestrained intestinal immune activation. Of note, the gut-brain interactome might relay microbiome-associated inflammatory signals from peripheral tissues to the brain (137, 139), contributing to depression- and suicide-associated neuroinflammation (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Proposed mechanism of microbiological inflammation in depression and suicide. In depression and suicide, alterations of the microbiome might disrupt intestinal barrier, allowing exposure of resident immune cells to pathogen-associated pro-inflammatory stimuli and concomitantly reducing the production of anti-inflammatory microbial products, including as short-chain fatty acids. As a result, unrestrained gastrointestinal immune activation occurs and might be relayed to the CNS via the gut-brain interactome, resulting in depression and suicide-associated inflammation.

4 Therapeutic insights

Current literature on the involvement of inflammation and various putative etiological pathways of this pathology in depression and suicide has prompted clinical examination of the efficacy of anti-inflammatory agents for the treatment of these psychiatric conditions. Early trials primarily focused on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs’ primary mechanism of action is to inhibit the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX), which is responsible for the production of inflammatory eicosanoids (thromboxanes, prostaglandins, and prostacyclins). As a standalone (140, 141) or adjunct therapy (142, 143), NSAIDs yielded promising outcomes as a treatment for depressive symptoms in MDD patients as well as those with other comorbid illnesses. NSAIDs were also suggested to be effective in mitigating SI risk (26), providing the impetus for further exploration of these agents in suicide prevention. Besides NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, whose binding on their cognate receptor, GR, turns on anti-inflammatory gene expression to curb immune cell activation, also exhibited short-term efficacy in alleviating depression (144, 145). Minocycline, an antibiotic with dual immunosuppressive function via its inhibition of the inflammasome (Caspase-1 and Caspase-3), pro-inflammatory enzymes (COX-2, inducible nitric oxide synthase [iNOS], matrix metalloproteinase [MMP], and phospholipase A2 [PLA2]), and immune cell proliferation/activation, also exerted anti-depressant effects in TRD patients and depressed HIV-infected subjects (146, 147). However, the efficacy of these agents requires further clinical validation (148). To date, the most compelling evidence for a pathway-focused treatment of depression, with mechanistic relevance to inflammatory pathology, emerged in clinical studies of inhibitors against different inflammatory cytokines (148). For example, IL-6 inhibitors (sirukumab and siltuximab) (149), IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor (ustekinumab) (150), IL-17 inhibitor (ixekizumab) (151), and TNF-α inhibitors (adalilumab and etanercept) (152–155) were effective in reducing depressive symptoms in patients with comorbid inflammatory diseases. Notably, infliximab, another TNF-α inhibitor, also showed some promising anti-depressant effect in TRD patients (60).

Besides these immune-related therapies, microbiome modifications have emerged as an attractive therapeutic promise in depression. Some proprietary probiotic formulations (live microorganisms with health-promoting benefits) were reportedly effective in reducing depressive symptoms (156–159). Additionally, prebiotics (nutrients that promote the growth of beneficial microorganisms) might possess some anti-depressant effects, with conflicting outcomes that require further confirmation (159, 160). Various molecular regulators of oxidative stress, HPA axis, and kynurenine pathway have also been proposed as promising therapeutic targets in depression treatment and suicide prevention (126, 161). Additionally, the impact of melatonin on depression-related inflammation warrants further examination, given its preliminary clinical effectiveness in depression (162). Other treatment approaches for depression focused on anti-infective agents (163) and their potential inhibitory effect on inflammation. Notably, melatonin and some anti-infective/anti-inflammatory therapies have been linked to the development of depressive symptoms and SB/SI, prompting additional caution when using these agents to treat psychiatric illnesses (164–166). Lastly, other treatment approaches with anti-inflammatory properties, such as psilocybin and cognitive behavioral therapies (167, 168), might provide additional mechanistic insights on the origin of inflammation in depression and suicide.

Given the diverse nature of inflammatory phenotypes of different subtype of depression and suicide, future treatment approaches might be more clinically impactful with detailed considerations of unique alterations in inflammatory biomarkers in prescribing anti-inflammatory treatments. Such biomarkers might also be of utility in monitoring treatment responsiveness, which are of urgent need in the case of TRD. Furthermore, the co-existence of dysfunctions in multiple inflammatory signaling pathways might require a combination treatment approach to achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes. Finally, integrated care that combines interventions addressing specific inflammatory pathology with current psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic treatments, is expected to improve therapeutic efficacy in depression and suicide.

5 Conclusions

The development of inflammatory pathology in depression and suicide may stem from dysregulation in immunological and neuroendocrinological signaling and improper microbial interactions with the host. Further investigations are required to elucidate the precise contributions of and/or interactions among these major physiological processes in distinct clinical subtypes of depression and suicide. These questions are of great clinical interest as they could help identify disease patterns, in the context of pathological inflammation, that may allow more targeted treatment approaches and personalized preventive strategies for depression and suicide.

Statements

Author contributions

AC: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AAm: Writing – review & editing. AAg: Writing – review & editing. LM: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. AP: Writing – review & editing. KN: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. IB: Writing – review & editing. MP: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MA: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. GS: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Open access funding by University of Geneva.

Conflict of interest

KN is the scientific founder of Tranquis Therapeutics, a biotechnology company that develops novel treatments for neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. KN is also a scientific advisor for Tochikunda, a biotechnology company that develops SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic devices.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

HawtonKvan HeeringenK. Suicide. Lancet. (2009) 373:1372–81. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60372-x

2

TureckiG. The molecular bases of the suicidal brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2014) 15:802–16. doi: 10.1038/nrn3839

3

van HeeringenKMannJJ. The neurobiology of suicide. Lancet Psychiatry. (2014) 1:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(14)70220-2

4

DeanJKeshavanM. The neurobiology of depression: An integrated view. Asian J Psychiatry. (2017) 27:101–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.01.025

5

MannJJRizkMM. A brain-centric model of suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. (2020) 177:902–16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20081224

6

CostanzaAD’OrtaIPerroudNBurkhardtSMalafosseAManginPet al. Neurobiology of suicide: do biomarkers exist? Int J Legal Med. (2013) 128:73–82. doi: 10.1007/s00414-013-0835-6

7

OquendoMASullivanGMSudolKBaca-GarciaEStanleyBHSubletteMEet al. Toward a biosignature for suicide. Am J Psychiatry. (2014) 171:1259–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020194

8

SudolKMannJJ. Biomarkers of suicide attempt behavior: towards a biological model of risk. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2017) 19:31–1. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0781-y

9

KouterKPaskaAV. Biomarkers for suicidal behavior: miRNAs and their potential for diagnostics through liquid biopsy - a systematic review. Epigenomics. (2020) 12:2219–35. doi: 10.2217/epi-2020-0196

10

OrsoliniLLatiniRPompiliMSerafiniGVolpeUVellanteFet al. Understanding the complex of suicide in depression: from research to clinics. Psychiatry Invest. (2020) 17:207–21. doi: 10.30773/pi.2019.0171

11

Fusar-PoliLAgugliaAAmerioAOrsoliniLSalviVSerafiniGet al. Peripheral BDNF levels in psychiatric patients with and without a history of suicide attempt: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2021) 111:110342. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110342

12

IvanetsNNSvistunovAAChubarevVNKinkulkinaMATikhonovaYGSyzrantsevNSet al. Can molecular biology propose reliable biomarkers for diagnosing major depression? Curr Pharm design. (2021) 27:305–18. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666201124110437

13

TureckiGErnstCJollantFLabontéBMechawarN. The neurodevelopmental origins of suicidal behavior. Trends Neurosci. (2012) 35:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.11.008

14

HawtonKCasañas I ComabellaCHawCSaundersK. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. (2013) 147:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004

15

TureckiGBrentDA. Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet. (2016) 387:1227–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00234-2

16

CostanzaABaertschiMWeberKCanutoA. Maladies neurologiques et suicide: de la neurobiology au manque d'éspoir [Neurological diseases and suicide: from neurobiology to hopelessness. Rev Med Suisse. (2015) 11:402–5.

17

CostanzaAAmerioAAgugliaAEscelsiorASerafiniGBerardelliIet al. When sick brain and hopelessness meet: some aspects of suicidality in the neurological patient. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. (2020) 19:257–63. doi: 10.2174/1871527319666200611130804

18

AgugliaAAmerioAAsaroPCaprinoMConigliaroCGiacominiGet al. High-lethality of suicide attempts associated with platelet to lymphocyte ratio and mean platelet volume in psychiatric inpatient setting. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2021) 22:119–27. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2020.1761033

19

CostanzaAXekardakiAKovariEGoldGBourasCGiannakopoulosP. Microvascular burden and Alzheimer-type lesions across the age spectrum. J Alzheimers Dis. (2012) 32:643–52. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120835

20

AgugliaASerafiniGSolanoPGiacominiGConigliaroCSalviVet al. The role of seasonality and photoperiod on the lethality of suicide attempts: A case-control study. J Affect Disord. (2019) 246:895–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.094

21

AgugliaAGiacominiGMontagnaEAmerioAEscelsiorACapelloMet al. Meteorological variables and suicidal behavior: air pollution and apparent temperature are associated with high-lethality suicide attempts and male gender. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:653390–0. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.653390

22

AgugliaANataleAFusar-PoliLGneccoGBLechiaraAMarinoMet al. C-reactive protein as a potential peripheral biomarker for high-lethality suicide attempts. Life (Basel Switzerland). (2022) 12(10):1557. doi: 10.3390/life12101557

23

SerafiniGCostanzaAAgugliaAAmerioATrabuccoAEscelsiorAet al. The role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of depression and suicidal behavior: implications for treatment. Med Clinics North America. (2023) 107:1–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2022.09.001

24

SerafiniGParisiVMAgugliaAAmerioASampognaGFiorilloAet al. A specific inflammatory profile underlying suicide risk? Systematic review of the main literature findings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17(7):2393. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072393

25

Amasi-HartoonianNParianteCMCattaneoASforziniL. Understanding treatment-resistant depression using "omics" techniques: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. (2022) 318:423–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.011

26

CostanzaAAmerioAAgugliaASerafiniGAmoreMHaslerRet al. Hyper/neuroinflammation in COVID-19 and suicide etiopathogenesis: Hypothesis for a nefarious collision? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2022) 136:104606. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104606

27

MillerVHopkinsLWhorwellPJ. Suicidal ideation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2004) 2:1064–8. doi: 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00545-2

28

RaisonCLDemetrashviliMCapuronLMillerAH. Neuropsychiatric adverse effects of interferon-alpha: recognition and management. CNS Drugs. (2005) 19:105–23. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200519020-00002

29

ThomasAJFerrierINKalariaRNDavisSO'BrienJT. Cell adhesion molecule expression in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex in major depression in the elderly. Br J Psychiatry. (2002) 181:129–34. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.2.129

30

PandeyGNRizaviHSRenXFareedJHoppensteadtDARobertsRCet al. Proinflammatory cytokines in the prefrontal cortex of teenage suicide victims. J Psychiatr Res. (2012) 46:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.08.006

31

BufalinoCHepgulNAgugliaEParianteCM. The role of immune genes in the association between depression and inflammation: a review of recent clinical studies. Brain behavior Immun. (2013) 31:31–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.04.009

32

KhandakerGMZammitSBurgessSLewisGJonesPB. Association between a functional interleukin 6 receptor genetic variant and risk of depression and psychosis in a population-based birth cohort. Brain behavior Immun. (2018) 69:264–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.11.020

33

KöhlerCAFreitasTHMaesMde AndradeNQLiuCSFernandesBSet al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. (2017) 135:373–87. doi: 10.1111/acps.12698

34

AnzolinAPFeitenJGBristotGPossebonGMPFleckMCaldieraroMAet al. Earlier age of onset is associated with a pro-inflammatory state in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. (2022) 314:114601–1. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114601

35

MyintA-MLeonardBESteinbuschHWMKimY-K. Th1, Th2, and Th3 cytokine alterations in major depression. J Affect Disord. (2005) 88:167–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.07.008

36

DavamiMHBaharlouRAhmadi VasmehjaniAGhanizadehAKeshtkarMDezhkamIet al. Elevated IL-17 and TGF-β Serum levels: A positive correlation between T-helper 17 cell-related pro-inflammatory responses with major depressive disorder. Basic Clin Neurosci. (2016) 7:137–42. doi: 10.15412/J.BCN.03070207

37

MahajanGJVallenderEJGarrettMRChallagundlaLOverholserJCJurjusGet al. Altered neuro-inflammatory gene expression in hippocampus in major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2018) 82:177–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.11.017

38

EnacheDParianteCMMondelliV. Markers of central inflammation in major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining cerebrospinal fluid, positron emission tomography and post-mortem brain tissue. Brain behavior Immun. (2019) 81:24–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.06.015

39

RushGO'DonovanANagleLConwayCMcCrohanAO'FarrellyCet al. Alteration of immune markers in a group of melancholic depressed patients and their response to electroconvulsive therapy. J Affect Disord. (2016) 205:60–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.035

40

Sowa-KućmaMStyczeńKSiwekMMisztakPNowakRJDudekDet al. Lipid peroxidation and immune biomarkers are associated with major depression and its phenotypes, including treatment-resistant depression and melancholia. Neurotoxicity Res. (2018) 33:448–60. doi: 10.1007/s12640-017-9835-5

41

YangCTiemessenKMBoskerFJWardenaarKJLieJSchoeversRA. Interleukin, tumor necrosis factor-α and C-reactive protein profiles in melancholic and non-melancholic depression: A systematic review. J psychosomatic Res. (2018) 111:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.05.008

42

DionisieVFilipGAManeaMCMovileanuRCMoisaEManeaMet al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, a novel inflammatory marker, as a predictor of bipolar type in depressed patients: A quest for biological markers. J Clin Med. (2021) 10(9):1924. doi: 10.3390/jcm10091924

43

MaoRZhangCChenJZhaoGZhouRWangFet al. Different levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in patients with unipolar and bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. (2018) 237:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.115

44

BrunoniARSupasitthumrongTTeixeiraALVieiraELGattazWFBenseñorIMet al. Differences in the immune-inflammatory profiles of unipolar and bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. (2020) 262:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.037

45

PolettiSMazzaMGCalesellaFVaiBLorenziCManfrediEet al. Circulating inflammatory markers impact cognitive functions in bipolar depression. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 140:110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.05.071

46

SuS-CSunM-TWenM-JLinC-JChenY-CHungY-J. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, adiponectin, and proinflammatory markers in various subtypes of depression in young men. Int J Psychiatry Med. (2011) 42:211–26. doi: 10.2190/PM.42.3.a

47

YoonH-KKimY-KLeeH-JKwonD-YKimL. Role of cytokines in atypical depression. Nordic J Psychiatry. (2012) 66:183–8. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.611894

48

LamersFVogelzangsNMerikangasKRde JongePBeekmanATFPenninxBWJH. Evidence for a differential role of HPA-axis function, inflammation and metabolic syndrome in melancholic versus atypical depression. Mol Psychiatry. (2013) 18:692–9. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.144

49

SongCLuchtmanDKangZTamEMYathamLNSuK-Pet al. Enhanced inflammatory and T-helper-1 type responses but suppressed lymphocyte proliferation in patients with seasonal affective disorder and treated by light therapy. J Affect Disord. (2015) 185:90–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.003

50

LeuSJShiahISYathamLNCheuYMLamRW. Immune-inflammatory markers in patients with seasonal affective disorder: effects of light therapy. J Affect Disord. (2001) 63:27–34. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00165-8

51

CorwinEJJohnstonNPughL. Symptoms of postpartum depression associated with elevated levels of interleukin-1 beta during the first month postpartum. Biol Res Nurs. (2008) 10:128–33. doi: 10.1177/1099800408323220

52

LiuHZhangYGaoYZhangZ. Elevated levels of Hs-CRP and IL-6 after delivery are associated with depression during the 6 months post partum. Psychiatry Res. (2016) 243:43–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.022

53

MaesMLinAHOmbeletWStevensKKenisGDe JonghRet al. Immune activation in the early puerperium is related to postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2000) 25:121–37. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(99)00043-8

54

Nicoloro-SantaBarbaraJMCarrollJEMinissianMKilpatrickSJColeSMerzCNBet al. Immune transcriptional profiles in mothers with clinically elevated depression and anxiety symptoms several years post-delivery. Am J Reprod Immunol (New York N.Y: 1989). (2022) 88:e13619. doi: 10.1111/aji.13619.

55

GaynesBNLuxLGartlehnerGAsherGForman-HoffmanVGreenJet al. Defining treatment-resistant depression. Depression Anxiety. (2020) 37:134–45. doi: 10.1002/da.22968

56

StrawbridgeRHodsollJPowellTRHotopfMHatchSLBreenGet al. Inflammatory profiles of severe treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. (2019) 246:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.037

57

MendlewiczJCrisafulliCCalatiRKocabasNAMassatILinotteSet al. Influence of COX-2 and OXTR polymorphisms on treatment outcome in treatment resistant depression. Neurosci Lett. (2012) 516:85–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.063

58

ParkMNewmanLEGoldPWLuckenbaughDAYuanPMaChado-VieiraRet al. Change in cytokine levels is not associated with rapid antidepressant response to ketamine in treatment-resistant depression. J Psychiatr Res. (2017) 84:113–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.025

59

RaisonCLRutherfordREWoolwineBJShuoCSchettlerPDrakeDFet al. A randomized controlled trial of the tumor necrosis factor antagonist infliximab for treatment-resistant depression: the role of baseline inflammatory biomarkers. JAMA Psychiatry. (2013) 70:31–41. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.4

60

KeatonSAMadajZBHeilmanPSmartLGritJGibbonsRet al. An inflammatory profile linked to increased suicide risk. J Affect Disord. (2019) 247:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.100

61

LindqvistDJanelidzeSHagellPErhardtSSamuelssonMMinthonLet al. Interleukin-6 is elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of suicide attempters and related to symptom severity. Biol Psychiatry. (2009) 66:287–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.030

62

JanelidzeSMatteiDWestrinÅTräskman-BendzLBrundinL. Cytokine levels in the blood may distinguish suicide attempters from depressed patients. Brain behavior Immun. (2011) 25:335–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.010

63

KimY-KHongJ-PHwangJ-ALeeH-JYoonH-KLeeB-Het al. TNF-alpha –308G>A polymorphism is associated with suicide attempts in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. (2013) 150:668–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.03.019

64

KimY-KLeeS-WKimS-HShimS-HHanS-WChoiS-Het al. Differences in cytokines between non-suicidal patients and suicidal patients in major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2008) 32:356–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.08.041

65

IsungJAeinehbandSMobarrezFMårtenssonBNordströmPAsbergMet al. Low vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-8 in cerebrospinal fluid of suicide attempters. Trans Psychiatry. (2012) 2:e196. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.123

66

LindqvistDJanelidzeSErhardtSTräskman-BendzLEngströmGBrundinL. CSF biomarkers in suicide attempters–a principal component analysis. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. (2011) 124:52–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01655.x

67

IsungJAeinehbandSMobarrezFNordströmPRunesonBAsbergMet al. High interleukin-6 and impulsivity: determining the role of endophenotypes in attempted suicide. Trans Psychiatry. (2014) 4:e470–0. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.113

68

BrentDAJohnsonBAPerperJConnollyJBridgeJBartleSet al. Personality disorder, personality traits, impulsive violence, and completed suicide in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1994) 33:1080–6. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199410000-00003

69

CoccaroEFLeeRCoussons-ReadM. Elevated plasma inflammatory markers in individuals with intermittent explosive disorder and correlation with aggression in humans. JAMA Psychiatry. (2014) 71:158–65. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3297

70

CostanzaARothenSAchabSThorensGBaertschiMWeberKet al. Impulsivity and impulsivity-related endophenotypes in suicidal patients with substance use disorders: an exploratory study. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2021) 19:1729–44. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00259-3

71

SchiavoneSNeriMMhillajEMorgeseMGCantatoreSBoveMet al. The NADPH oxidase NOX2 as a novel biomarker for suicidality: evidence from human post mortem brain samples. Trans Psychiatry. (2016) 6:e813. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.76

72

PandeyGNRizaviHSZhangHBhaumikRRenX. Abnormal protein and mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines in the prefrontal cortex of depressed individuals who died by suicide. J Psychiatry neuroscience: JPN. (2018) 43:376–85. doi: 10.1503/jpn.170192

73

WangQRoyBTureckiGSheltonRCDwivediY. Role of complex epigenetic switching in tumor necrosis factor-α Upregulation in the prefrontal cortex of suicide subjects. Am J Psychiatr. (2018) 175:262–74. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16070759

74

Torres-PlatasSGCruceanuCChenGGTureckiGMechawarN. Evidence for increased microglial priming and macrophage recruitment in the dorsal anterior cingulate white matter of depressed suicides. Brain Behavior Immun. (2014) 42:50–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.05.007

75

JanelidzeSVentorpFErhardtSHanssonOMinthonLFlaxJet al. Altered chemokine levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of suicide attempters. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2013) 38:853–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.09.010

76

O'DonovanARushGHoatamGHughesBMMcCrohanAKelleherCet al. Suicidal ideation is associated with elevated inflammation in patients with major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. (2013) 30:307–14. doi: 10.1002/da.22087

77

BokorJSutoriSTorokDGalZEszlariNGyorikDet al. Inflamed mind: multiple genetic variants of IL6 influence suicide risk phenotypes in interaction with early and recent adversities in a linkage disequilibrium-based clumping analysis. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:746206. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.746206

78

KnowlesEEMCurranJEGöringHHHMathiasSRMollonJRodrigueAet al. Family-based analyses reveal novel genetic overlap between cytokine interleukin-8 and risk for suicide attempt. Brain Behav Immun. (2019) 80:292–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.04.004

79

MelhemNMMunroeSMarslandAGrayKBrentDPortaGet al. Blunted HPA axis activity prior to suicide attempt and increased inflammation in attempters. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2017) 77:284–94. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.01.001

80

VasupanrajitAJirakranKTunvirachaisakulCSolmiMMaesM. Inflammation and nitro-oxidative stress in current suicidal attempts and current suicidal ideation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry (2022) 27(3):1350–61. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01407-4

81

DantzerR. Cytokine, sickness behavior, and depression. Immunol Allergy Clinics North America. (2009) 29:247–64. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2009.02.002

82

GrosseLCarvalhoLABirkenhagerTKHoogendijkWJKushnerSADrexhageHAet al. Circulating cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells as potential predictors for antidepressant response in melancholic depression. Restor T Regul Cell populations after antidepressant Ther Psychopharmacol. (2016) 233:1679–88. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3943-9

83

SchiweckCValles-ColomerMAroltVMüllerNRaesJWijkhuijsAet al. Depression and suicidality: A link to premature T helper cell aging and increased Th17 cells. Brain behavior Immun. (2020) 87:603–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.02.005

84

ValescoÁRodríguez-RevueltaJOliéEAbadIFernández-PeláezACazalsAet al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: A potential new peripheral biomarker of suicidal behavior. Eur psychiatry: J Assoc Eur Psychiatrists. (2020) 63:e14. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2019.20

85

TuralUIrvinMKIosifescuDV. Correlation between S100B and severity of depression in MDD: A meta-analysis. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2022) 23:456–63. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2021.2013042

86

MichelMFiebichBLKuziorHMeixensbergerSBergerBMaierSet al. Increased GFAP concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with unipolar depression. Trans Psychiatry. (2021) 11:308. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01423-6

87

Torres-PlatasSGHercherCDavoliMAMaussionGLabontéBTureckiGet al. Astrocytic hypertrophy in anterior cingulate white matter of depressed suicides. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2011) 36:2650–8. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.154

88

WuMKHuangTLHuangKWHuangYLHungYY. Association between toll-like receptor 4 expression and symptoms of major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2015) 11:1853–7. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S88430

89

PandeyGNRizaviHSRenXBhaumikRDwivediY. Toll-like receptors in the depressed and suicide brain. J Psychiatr Res. (2014) 53:62–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.01.021

90

PaceTWWingenfeldKSchmidtIMeinlschmidtGHellhammerDHHeimCM. Increased peripheral NF-kappaB pathway activity in women with childhood abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Brain behavior Immun. (2012) 26:13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.07.232

91

MiklowitzDJPortnoffLCArmstrongCCKeenan-MillerDBreenECMuscatellKAet al. Inflammatory cytokines and nuclear factor-kappa B activation in adolescents with bipolar and major depressive disorders. Psychiatry Res. (2016) 241:315–22. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.120

92

KaufmannFNCostaAPGhisleniGDiazAPRodriguesALSPeluffoHet al. NLRP3 inflammasome-driven pathways in depression: Clinical and preclinical findings. Brain behavior Immun. (2017) 64:367–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.03.002

93

TaeneAKhalili-TanhaGEsmaeiliAMobasheriLKooshkakiOJafariSet al. The association of major depressive disorder with activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, lipid peroxidation, and total antioxidant capacity. J Mol Neurosci. (2020) 70:65–70. doi: 10.1007/s12031-019-01401-0

94

MomeniMGhorbanKDadmaneshMKhodadadiHBidakiRKazemi ArababadiMet al. ASC provides a potential link between depression and inflammatory disorders: A clinical study of depressed Iranian medical students. Nordic J Psychiatry. (2016) 70:280–4. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2015.1100328

95

HanKMChoiKWKimAKangWKangYTaeWSet al. Association of DNA methylation of the NLRP3 gene with changes in cortical thickness in major depressive disorder. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:5768. doi: 10.3390/ijms23105768

96

PandeyGNZhangHSharmaARenX. Innate immunity receptors in depression and suicide: upregulated NOD-like receptors containing pyrin (NLRPs) and hyperactive inflammasomes in the postmortem brains of people who were depressed and died by suicide. J Psychiatry Neurosci. (2021) 46:E538–47. doi: 10.1503/jpn.210016

97

SokołowskaPSeweryn KarbownikMJóźwiak-BębenistaMDobielskaMKowalczykEWiktorowska-OwczarekA. Antidepressant mechanisms of ketamine's action: NF-κB in the spotlight. Biochem Pharmacol. (2023) 218:115918. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115918

98

Alcocer-GómezEde MiguelMCasas-BarqueroNNúñez-VascoJSánchez-AlcazarJAFernández-RodríguezAet al. NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in mononuclear blood cells from patients with major depressive disorder. Brain behavior immunity. (2014) 36:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.10.017

99

BerardelliISerafiniGCorteseNFiaschèFO'ConnorRCPompiliM. The involvement of hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in suicide risk. Brain Sci. (2020) 10(9):653. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10090653

100

DuXPangTY. Is dysregulation of the HPA-axis a core pathophysiology mediating co-morbid depression in neurodegenerative diseases? Front Psychiatry. (2015) 6:32–2. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00032

101

SchatzbergAFRothschildAJLanglaisPJBirdEDColeJO. A corticosteroid/dopamine hypothesis for psychotic depression and related states. J Psychiatr Res. (1985) 19:57–64. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(85)90068-8

102

HenningsJMIsingMUhrMHolsboerFLucaeS. Effects of weariness of life, suicide ideations and suicide attempt on HPA axis regulation in depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2021) 131:105286–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105286

103

O'ConnorDBFergusonEGreenJAO'CarrollREO'ConnorRC. Cortisol levels and suicidal behavior: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2016) 63:370–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.10.011

104

McGowanPOSasakiAD'AlessioACDymovSLabontéBSzyfMet al. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nat Neurosci. (2009) 12(3):342–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270

105

RaisonCLMillerAH. When not enough is too much: the role of insufficient glucocorticoid signaling in the pathophysiology of stress-related disorders. Am J Psychiatry. (2003) 160:1554–65. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1554

106

PandeyGNRizaviHSRenXDwivediYPalkovitsM. Region-specific alterations in glucocorticoid receptor expression in the postmortem brain of teenage suicide victims. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2013) 38:2628–39. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.06.020

107

DemirkanALahtiJDirekNViktorinALunettaKLTerraccianoAet al. Somatic, positive and negative domains of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. psychol Med. (2016) 46:1613–23. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002081

108

SrinivasanVSmitsMSpenceWLoweADKayumovLPandi-PerumalSRet al. Melatonin in mood disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2006) 7:138–51. doi: 10.1080/15622970600571822

109

SandykRAwerbuchGI. Nocturnal melatonin secretion in suicidal patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J Neurosci. (1993) 71:173–82. doi: 10.3109/00207459309000602

110

WonENaK-SKimY-K. Associations between melatonin, neuroinflammation, and brain alterations in depression. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 23(1):305. doi: 10.3390/ijms23010305

111

MorenoFAParkinsonDPalmerCCastroWLMisiaszekJEl KhouryAet al. CSF neurochemicals during tryptophan depletion in individuals with remitted depression and healthy controls. Eur neuropsychopharmacology: J Eur Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. (2010) 20:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.10.003

112

CapuronLGumnickJFMusselmanDLLawsonDHReemsnyderANemeroffCBet al. Neurobehavioral effects of interferon-alpha in cancer patients: phenomenology and paroxetine responsiveness of symptom dimensions. Neuropsychopharmacology: Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. (2002) 26:643–52. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00407-9

113

KohlCWalchTHuberRKemmlerGNeurauterGFuchsDet al. Measurement of tryptophan, kynurenine and neopterin in women with and without postpartum blues. J Affect Disord. (2005) 86:135–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.12.013

114

RaisonCLDantzerRKelleyKWLawsonMAWoolwineBJVogtGet al. CSF concentrations of brain tryptophan and kynurenines during immune stimulation with IFN-alpha: relationship to CNS immune responses and depression. Mol Psychiatry. (2010) 15:393–403. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.116

115

MeierTBDrevetsWCWurfelBEFordBNMorrisHMVictorTAet al. Relationship between neurotoxic kynurenine metabolites and reductions in right medial prefrontal cortical thickness in major depressive disorder. Brain behavior Immun. (2016) 53:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.11.003

116

Lugo-HuitrónRBlanco-AyalaTUgalde-MuñizPCarrillo-MoraPPedraza-ChaverríJSilva-AdayaDet al. On the antioxidant properties of kynurenic acid: free radical scavenging activity and inhibition of oxidative stress. Neurotoxicology teratology. (2011) 33:538–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.07.002

117

SteinerJWalterMGosTGuilleminGJBernsteinH-GSarnyaiZet al. Severe depression is associated with increased microglial quinolinic acid in subregions of the anterior cingulate gyrus: evidence for an immune-modulated glutamatergic neurotransmission? J Neuroinflamm. (2011) 8:94–4. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-94

118

AsbergM. Neurotransmitters and suicidal behavior. evidence cerebrospinal fluid Stud Ann New York Acad Sci. (1997) 836:158–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52359.x

119

Bay-RichterCLinderholmKRLimCKSamuelssonMTräskman-BendzLGuilleminGJet al. A role for inflammatory metabolites as modulators of the glutamate N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor in depression and suicidality. Brain Behav Immun. (2015) 43:110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.012

120

BrundinLSellgrenCMLimCKGritJPålssonELandénMet al. An enzyme in the kynurenine pathway that governs vulnerability to suicidal behavior by regulating excitotoxicity and neuroinflammation. Trans Psychiatry. (2016) 6:e865. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.133

121

SubletteMEGalfalvyHCFuchsDLapidusMGrunebaumMFOquendoMAet al. Plasma kynurenine levels are elevated in suicide attempters with major depressive disorder. Brain behavior Immun. (2011) 25:1272–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.05.002

122

SzebeniASzebeniKDiPeriTPJohnsonLAStockmeierCACrawfordJDet al. Elevated DNA oxidation and DNA repair enzyme expression in brain white matter in major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. (2017) 20:363–73. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw114

123

Jiménez-FernándezSGurpeguiMGarrote-RojasDGutiérrez-RojasLCarreteroMDCorrellCU. Oxidative stress parameters and antioxidants in adults with unipolar or bipolar depression versus healthy controls: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2022) 314:211–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.07.015

124

VargasHONunesSOVPizzo de CastroMBortolasciCCSabbatini BarbosaDKaminami MorimotoHet al. Oxidative stress and lowered total antioxidant status are associated with a history of suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. (2013) 150:923–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.016

125

DaneseAParianteCMCaspiATaylorAPoultonR. Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2007) 104:1319–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610362104

126

RybkaJKędziora-KornatowskaKBanaś-LeżańskaPMajsterekICarvalhoLACattaneoAet al. Interplay between the pro-oxidant and antioxidant systems and proinflammatory cytokine levels, in relation to iron metabolism and the erythron in depression. Free Radical Biol Med. (2013) 63:187–94. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.05.019

127

JiangHLingZZhangYMaoHMaZYinYet al. Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain behavior Immun. (2015) 48:186–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.03.016

128

MirandaOFanPQiXYuZYingJWangHet al. DeepBiomarker: identifying important lab tests from electronic medical records for the prediction of suicide-related events among PTSD patients. J personalized Med. (2022) 12(4):524. doi: 10.3390/jpm12040524

129

McGuinnessAJDavisJADawsonSLLoughmanACollierFO'HelyMet al. A systematic review of gut microbiota composition in observational studies of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Molelcular Psychiatry. (2022) 27:1920–35. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01456-3

130

SimpsonCAAdlerCdu PlessisMRLandauERDashperSGReynoldsECet al. Oral microbiome composition, but not diversity, is associated with adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms. Physiol Behav. (2020) 226:113126. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113126

131

WingfieldBLapsleyCMcDowellAMiliotisGMcLaffertyMO'NeillSMet al. Variations in the oral microbiome are associated with depression in young adults. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:15009. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-94498-6

132

MaesMVasupanrajitAJirakranKKlomkliewPChanchaemPTunvirachaisakulCet al. Adverse childhood experiences and reoccurrence of illness impact the gut microbiome, which affects suicidal behaviours and the phenome of major depression: towards enterotypic phenotypes. Acta neuropsychiatrica. (2023) 13:1–18. doi: 10.1017/neu.2023.21

133

AhrensAPSanchez-PadillaDEDrewJCOliMWRoeschLFWTriplettEW. Saliva microbiome, dietary, and genetic markers are associated with suicidal ideation in university students. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:14306. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-18020-2

134

LengvenyteAStrumilaRMaimounLSenequeMOliéELefebvrePet al. A specific association between laxative misuse and suicidal behaviours in patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Eating weight Disord. (2022) 27:307–15. doi: 10.1007/s40519-021-01180-x

135

OhlssonLGustafssonALavantESunesonKBrundinLWestrinÅet al. Leaky gut biomarkers in depression and suicidal behavior. Acta psychiatrica scandinavia. (2019) 139:185–93. doi: 10.1111/acps.2019.139.issue-2

136

MadisonAAAndridgeRKantarasAHRennaMEBennettJMAlfanoCMet al. Depression, inflammation, and intestinal permeability: associations with subjective and objective cognitive functioning throughout breast cancer survivorship. Cancers (Basel). (2023) 15:4414. doi: 10.3390/cancers15174414

137

RudzkiLMaesM. The microbiota-gut-immune-glia (MGIG) axis in major depression. Mol Neurobiol. (2020) 57:4269–95. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-01961-y

138

Skonieczna-ŻydeckaKGrochansEMaciejewskaDSzkupMSchneider-MatykaDJurczakAet al. Faecal short chain fatty acids profile is changed in polish depressive women. Nutrients. (2018) 10(12):1939. doi: 10.3390/nu10121939

139

KimIBParkSCKimYK. Microbiota-gut-brain axis in major depression: A new therapeutic approach. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2023) 1411:209–24. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-7376-5

140

SchwarzMJDehningSDouheACeroveckiAGoldstein-MüllerBSpellmannIet al. The cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib has therapeutic effects in major depression: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled, add-on pilot study to reboxetine. Mol Psychiatry. (2006) 11:680–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001805

141

AkhondzadehSJafariSRaisiFNasehiAAGhoreishiASalehiBet al. Clinical trial of adjunctive celecoxib treatment in patients with major depression: a double blind and placebo controlled trial. Depression Anxiety. (2009) 26:607–11. doi: 10.1002/da.20589

142

JafariSAshrafizadehSGZeinoddiniARasoulinejadMEntezariPSeddighiSet al. Celecoxib for the treatment of mild-to-moderate depression due to acute brucellosis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. J Clin Pharm Ther. (2015) 40:441–6. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12287

143

AlamdarsaraviMGhajarANoorbalaAAArbabiMEmamiAShaheiFet al. Efficacy and safety of celecoxib monotherapy for mild to moderate depression in patients with colorectal cancer: A randomized double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 255:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.029

144

DeBattistaCPosenerJAKalehzanBMSchatzbergAF. Acute antidepressant effects of intravenous hydrocortisone and CRH in depressed patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. (2000) 157:1334–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1334

145

AranaGWSantosABLaraiaMTMcLeod-BryantSBealeMDRamesLJet al. Dexamethasone for the treatment of depression: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Am J Psychiatry. (1995) 152:265–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.2.265

146

Emadi-KouchakHMohammadinejadPAsadollahi-AminARasoulinejadMZeinoddiniAYaldaAet al. Therapeutic effects of minocycline on mild-to-moderate depression in HIV patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (2016) 31:20–6. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000098

147

HusainMIChaudhryIBHusainNKhosoABRahmanRRHamiraniMMet al. Minocycline as an adjunct for treatment-resistant depressive symptoms: A pilot randomised placebo-controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. (2017) 31:1166–75. doi: 10.1177/0269881117724352

148

Köhler-ForsbergOLydholm CNHjorthøjCNordentoftMMorsOBenrosME. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory treatment on major depressive disorder or depressive symptoms: meta-analysis of clinical trials. Acta psychiatrica scandinavica. (2019) 139:404–19. doi: 10.1111/acps.13016

149

SunYWangDSalvadoreGHsuBCurranMCasperCet al. The effects of interleukin-6 neutralizing antibodies on symptoms of depressed mood and anhedonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and multicentric Castleman's disease. Brain behaviors immunity. (2017) 66:156–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.06.014

150