94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol. , 26 April 2023

Sec. Cancer Immunity and Immunotherapy

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1138355

Yangxun Pan1,2†

Yangxun Pan1,2† Xiaodong Zhu3†

Xiaodong Zhu3† Jianwei Liu4

Jianwei Liu4 Jianhong Zhong5

Jianhong Zhong5 Wei Zhang6

Wei Zhang6 Shunli Shen7

Shunli Shen7 Renan Jin8

Renan Jin8 Hongzhi Liu9

Hongzhi Liu9 Feng Ye10

Feng Ye10 Kuan Hu11

Kuan Hu11 Da Xu12

Da Xu12 Yu Zhang13

Yu Zhang13 Zhong Chen13

Zhong Chen13 Baocai Xing12

Baocai Xing12 Ledu Zhou11

Ledu Zhou11 Yongjun Chen10

Yongjun Chen10 Yongyi Zeng9

Yongyi Zeng9 Xiao Liang8

Xiao Liang8 Ming Kuang7

Ming Kuang7 Tianqiang Song6

Tianqiang Song6 Bangde Xiang5

Bangde Xiang5 Kui Wang4

Kui Wang4 Huichuan Sun3*

Huichuan Sun3* Li Xu1,2* and China Liver Cancer Study Group Young Investigators (CLEAP)

Li Xu1,2* and China Liver Cancer Study Group Young Investigators (CLEAP)Background: Systemic therapy is the standard care of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC), while transcatheter intra-arterial therapies (TRITs) were also widely applied to uHCC patients in Chinese practice. However, the benefit of additional TRIT in these patients is unclear. This study investigated the survival benefit of concurrent TRIT and systemic therapy used as first-line treatment for patients with uHCC.

Methods: This real-world, multi-center retrospective study included consecutive patients treated at 11 centers accross China between September 2018 and April 2022. Eligible patients had uHCC of China liver cancer stages IIb to IIIb (Barcelona clinic liver cancer B or C stage), and received first-line systemic therapy with or without concurrent TRIT. Of 289 patients included, 146 received combination therapy and 143 received systemic therapy alone. The overall survival (OS), as primary outcomes, was compared between patients who received systemic therapy plus TRIT (combination group) or systemic therapy alone (systemic-only group) using survival analysis and Cox regression. Imbalances in baseline clinical features between the two groups were adjusted through propensity score matching (PSM) and inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW). Moreover, subgroup analysis was conducted based on the different tumor characteristics of enrolled uHCC patients.

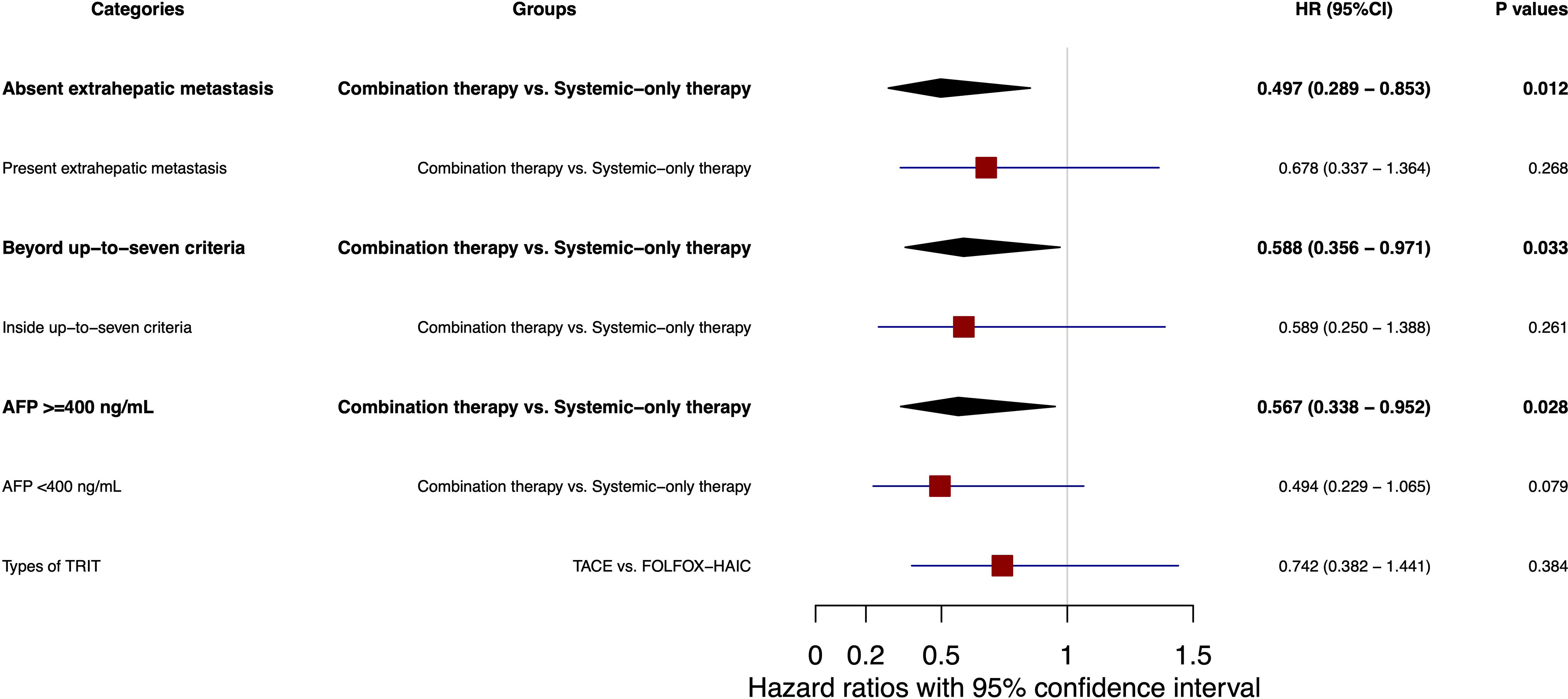

Results: The median OS was significantly longer in the combination group than the systemic-only group before adjustment [not reached vs. 23.9 months; hazard ratio (HR), 0.561; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.366 to 0.861; P = 0.008], after PSM (HR, 0.612; 95% CI, 0.390 to 0.958; P = 0.031) and after IPTW (HR, 0.539; 95% CI, 0.116 to 0.961; P = 0.008). Subgroup analyses suggested the benefit of combining TRIT with systemic therapy was greatest in patients with liver tumors exceeding the up-to-seven criteria, with an absence of extrahepatic metastasis, or with alfa-fetoprotein ≥ 400 ng/ml.

Conclusion: Concurrent TRIT with systemic therapy was associated with improved survival compared with systemic therapy alone as first-line treatment for uHCC, especially for patients with high-intrahepatic tumor load and no extrahepatic metastasis.

Primary liver cancer was the sixth most common malignancy and third leading cause of cancer death worldwide in 2020, with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounting for 75 to 85% of cases (1). Since HCC generally progresses asymptomatically, most patients in China are diagnosed with intermediate- or advanced-stage disease, which is not amenable to radical therapies and has a poor long-term prognosis (2). Systemic therapies, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), bevacizumab, and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), are recommended as first-line treatments for patients with advanced- or intermediate-stage HCC with diffuse or extensive liver involvement (3). Chinese treatment guidelines for HCC also recommend transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) (4). In clinical practice, many patients with uHCC receive TACE or other transcatheter intra-arterial therapies (TRITs), such as hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy (HAIC), in combination with systemic therapy. However, whether the addition of TRIT improves outcomes compared with systemic therapy alone remains controversial.

Significant advances in locoregional and systemic therapies in recent years have substantially improved the prognosis for patients with uHCC. For example, HAIC with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX-HAIC) has emerged as a more potent TRIT compared with TACE for patients with tumors larger than 7 cm (5). However, despite decades of development, only two TKIs, sorafenib and lenvatinib, are currently recommended as first-line systemic therapy for patients with advanced HCC, and these agents provide only a limited benefit (6, 7). Nonetheless, highly promising preliminary results from the IMbrave150 and LEAP-002 trials showing objective response rates (ORRs) of 30% or higher have provided support for the further investigation of combinations of molecularly targeted drugs (MTDs) and ICIs for HCC treatment (8, 9).

Given the trend toward an increasing use of combination therapies for uHCC, there is significant interest in the potential of systemic therapy plus TRIT to improve tumor control (10, 11). Of note, sorafenib plus FOLFOX-HAIC or lenvatinib plus TACE have recently been shown to prolong median overall survival (OS) by 5 to 6 months compared with TKIs alone (12, 13). Several small, exploratory trials of TRIT combined with MTDs plus ICIs have also shown encouraging efficacy in patients with uHCC (14–18) but were mostly limited by single-arm, single-center designs. Overall, there is a lack of data from multi-center, head-to-head studies comparing outcomes between MTD plus ICI combinations, when administered with or without TRIT.

In the present study, we compared long-term outcomes for patients receiving dual (MTD plus ICI) systemic therapy, with or without TACE/HAIC, using the large-scale China Liver Cancer Study Group Young Investigators (CLEAP) database, which includes data from 34 clinical centers across China. The analysis was expected to provide preliminary evidence that will inform the future use of these treatment strategies in patients with uHCC.

The CLEAP database contains data from 843 patients diagnosed with uHCC between September 2018 and April 2022 and treated at 34 clinical centers across China. Inclusion criteria for the present analysis were as follows: diagnosis of HCC according to clinical or pathological features based on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidelines (19); China liver cancer (CNLC) stage IIb, IIIa or IIIb (4), which corresponds to Barcelona Clinic liver cancer stage B or C; receipt of first-line systemic therapy with TKIs plus ICIs, with or without concurrent TRIT; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0 or 1 (20); and availability of complete medical and follow-up data. Exclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosis of other malignant tumors; use of local therapies other than TACE or HAIC; and use of systemic therapy regimens other than combinations of TKIs plus anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) antibodies. In addition, patients from centers that contributed fewer than five cases were excluded to avoid any potential impact of limited clinical experience with these regimens. Eligible patients were analyzed according to whether they received first-line systemic therapy with concurrent TRIT (combination group) or without concurrent TRIT (systemic-only group). Patients who received TRIT after confirmed progressive disease (PD) on systemic therapy were included in the systemic-only group. Systemic agents were administered according to the product package inserts and previous studies, based on current efficacy and safety data, prior treatment, and drug access (21).

The protocol complied with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center and Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (approval nos. B2022-301-01 and B20202-195R, respectively). All patients provided written informed consent for HCC treatment and the use of their medical records for research purposes.

Tumor assessments were performed every two to three cycles (i.e., every 6 to 12 weeks) using contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging for intrahepatic tumors and upper abdominal metastasis and chest CT for lung metastases, with blood tests used to evaluate liver function and tumor markers. Tumor responses were defined as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or PD according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1 (22). The ORR was calculated as the proportion of patients with the best response of CR or PR. OS was defined as the time from treatment initiation to cancer-related death. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from treatment initiation to disease progression or death from any cause. Safety was evaluated based on the occurrence of severe (i.e., grade ≥ 3) treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs).

Continuous variables were summarized as means [standard deviation (SD)] or medians [interquartile range (IQR)], while categorical variables were summarized as counts (percentage). The Student’s t-test and Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare normally and non-normally distributed continuous variables, respectively. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, with comparison of OS and PFS curves conducted using the log-rank test. Survival outcomes were also analyzed by Cox regression using both univariate and multivariate models including relevant variables. Subgroup analyses were performed according to extrahepatic metastasis (presence or absence), intrahepatic tumor burden (within or exceeding the up-to-seven criteria) (23), alfa-fetoprotein (AFP) levels (< 400 or ≥ 400 ng/ml), and type of TRIT received (TACE or HAIC).

To adjust for differences in potential confounding variables, propensity scores were calculated using logistic regression and matched for 1:1 nearest-neighbor individuals according to the logit of the propensity scores, with a caliper width of 0.1 times the SD of the propensity score logit (24). Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed with the “MatchIt” package within R software and included the variables tumor size, hepatic vein invasion and ECOG PS. In addition, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was performed as a sensitivity analysis with the same variables using the “WeightIt” package within R (25). All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.2.1 (http://www.r-project.org/). P-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

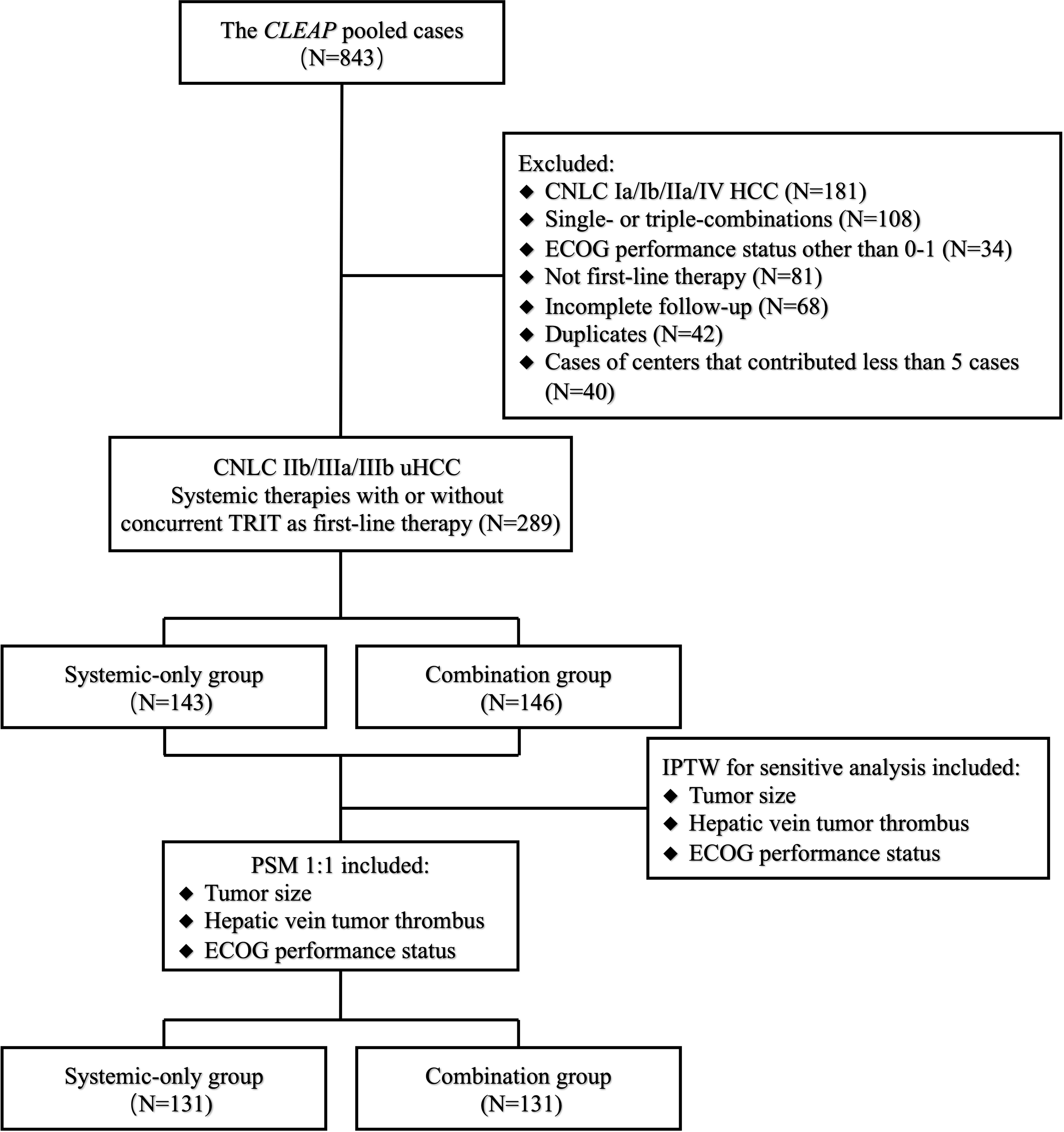

The analysis included 289 eligible patients treated with first-line systemic therapy with TKIs plus PD-1 antibodies, with or without concurrent TRIT, between 21 September 2018 and 26 April 2022. Patient disposition is shown in Figure 1. In the overall population, the median age was 54.00 years (IQR, 48.00 to 61.00), and the majority of patients were male (90.3%) (Table 1). Most patients had hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (serum positivity for HBsAg, HBcAb, or HBeAb) as the etiology of uHCC (86.9%), Child-Pugh class A liver function (95.2%), and ECOG PS 0 (74.4%). Overall, 18.0, 46.4, and 35.6% of patients were diagnosed with CNLC stages IIb, IIIa, and IIIb, respectively.

Figure 1 Patient disposition. CLEAP, China Liver Cancer Study Group Young Investigators; CNLC, China liver cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; uHCC, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma; PSM, propensity score matching; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting.

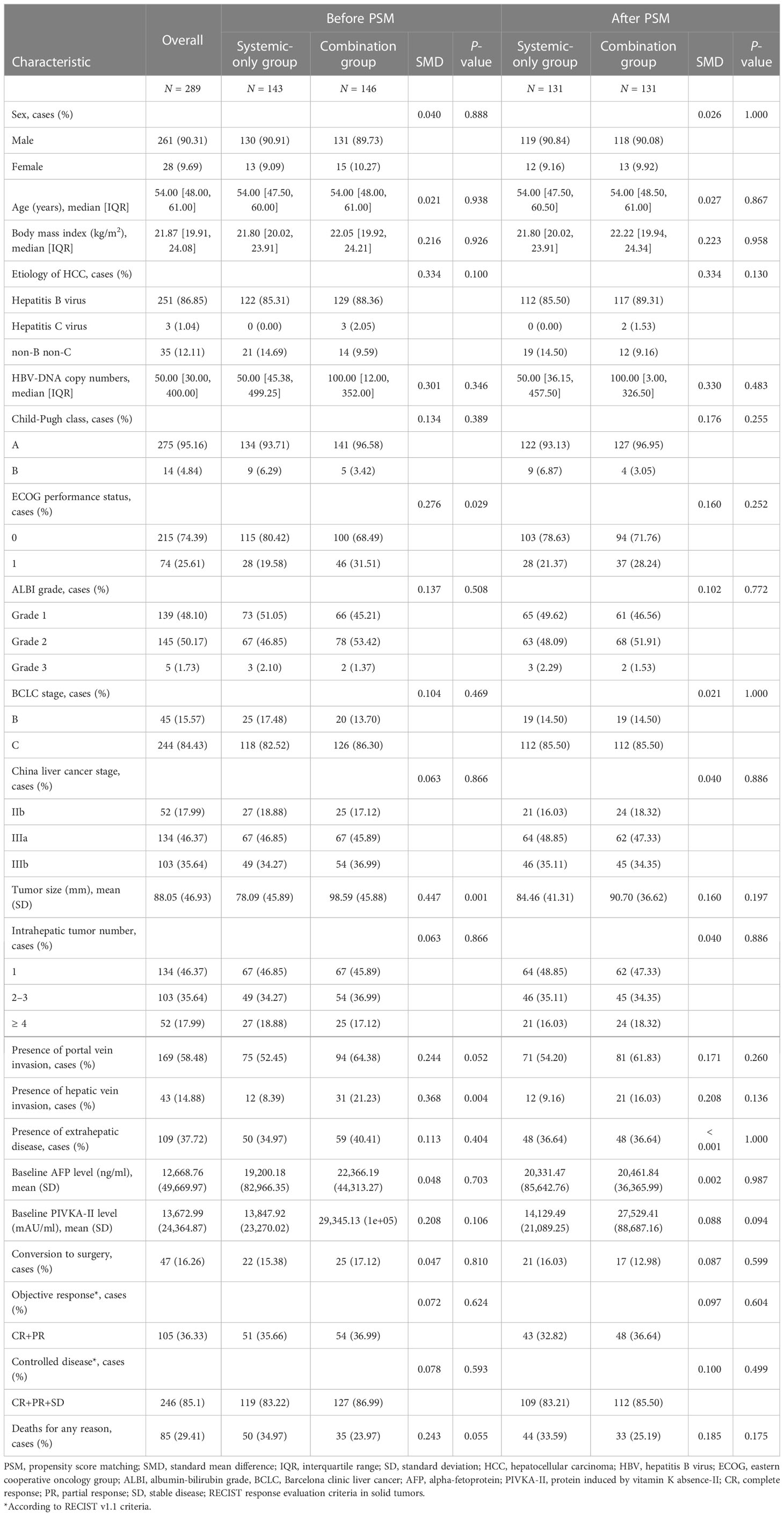

Table 1 Baseline demographics and disease characteristics and outcomes of patients before and after PSM.

Although baseline variables were generally comparable between the two groups, the combination versus systemic-only group had significantly higher percentages of patients with ECOG PS 1 (31.5 vs. 19.6%, respectively; P = 0.029), hepatic vein invasion (21.2 vs. 8.4%, respectively; P = 0.004), and larger tumor size (98.6 ± 45.9 vs. 78.1 ± 45.9 mm, respectively; P = 0.001).

Patients received various oral TKIs, including lenvatinib (87.9%), apatinib (8.3%), and sorafenib (3.5%), and anti–PD-1 antibodies, including sintilimab (31.2%), camrelizumab (29.4%), toripalimab (21.1%), tislelizumab (9.0%), pembrolizumab (6.7%), and nivolumab (2.6%). TRIT (i.e., TACE and HAIC) was administered following digital subtraction angiography via right femoral artery puncture and catheterization. TACE agents were mainly epirubicin and platinum with lipiodized oil, while HAIC mostly comprised oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and fluorouracil on the first day, with maintenance of the fluorouracil infusion for 23h or 46h, according to standard local practice. Treatment was continued until PD, unacceptable toxicity, or curative hepatectomy. For patients with HBV infection, the oral antiviral agents entecavir or tenofovir were prescribed throughout anti-cancer treatment.

At the data cut-off of 19 August 2022, the median follow-up was 11.57 months (IQR, 6.73 to 20.33) for the overall population. A total of 85 (29.4%) patients had died, and the median OS for all patients was 34.33 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 23.00 months to not reached [NR]), while the median PFS was 12.27 months (95% CI, 9.27 months to 17.93 months).

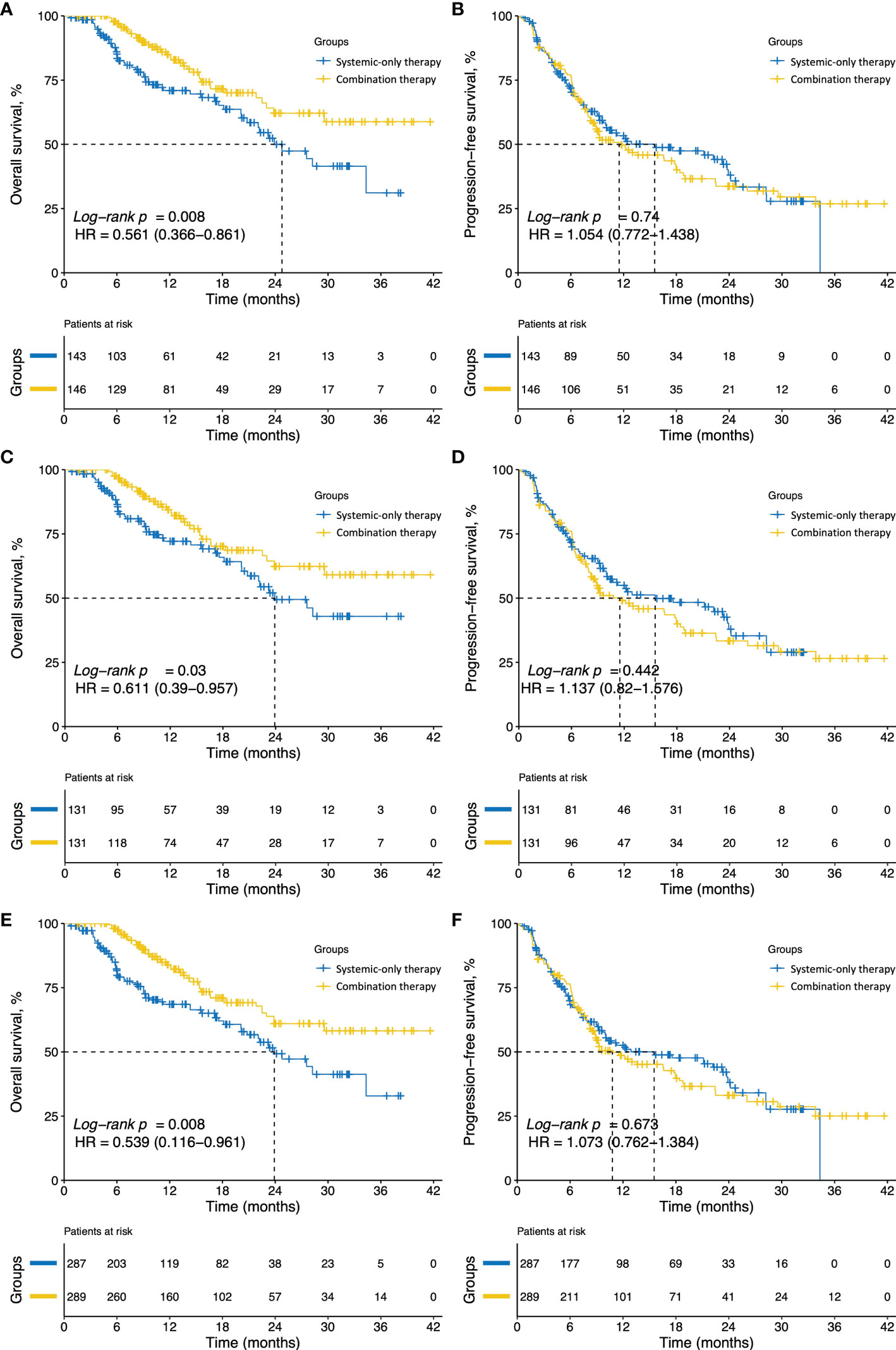

During follow-up, 35 patients (24.0%) in the combination group and 50 (34.8%) in the systemic-only group died. The median OS was significantly longer in the combination group compared with the systemic-only group [hazard ratio (HR), 0.561; 95% CI, 0.366 to 0.861; P = 0.008; Figure 2A], with 12-, 24-, and 36-month OS rates of 83.9, 62.1, and 58.8%, respectively, with combination therapy and 71.0, 50.0, and 31.1% with systemic-only therapy. However, the 12-, 24-, and 36-month PFS rates were comparable between the groups: 48.8, 33.7, and 26.9%, respectively, in the combination group and 53.4, 38.0, and 27.8% in the systemic-only group (HR, 1.054; 95% CI, 0.772 to 1.438; P = 0.740; Figure 2B).

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) for patients in the different groups. (A) OS and (B) PFS of patients in the systemic-only group (N = 143) or combination group (N = 146) before PSM. (C) OS and (D) PFS for the systemic-only group (N = 131) and combination group (N = 131) after PSM. (E) OS and (F) PFS for patients in the systemic-only group (N = 287.37) and combination group (N = 289.04) weighted by IPTW. HR, hazard ratio; PSM, propensity score matching; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting.

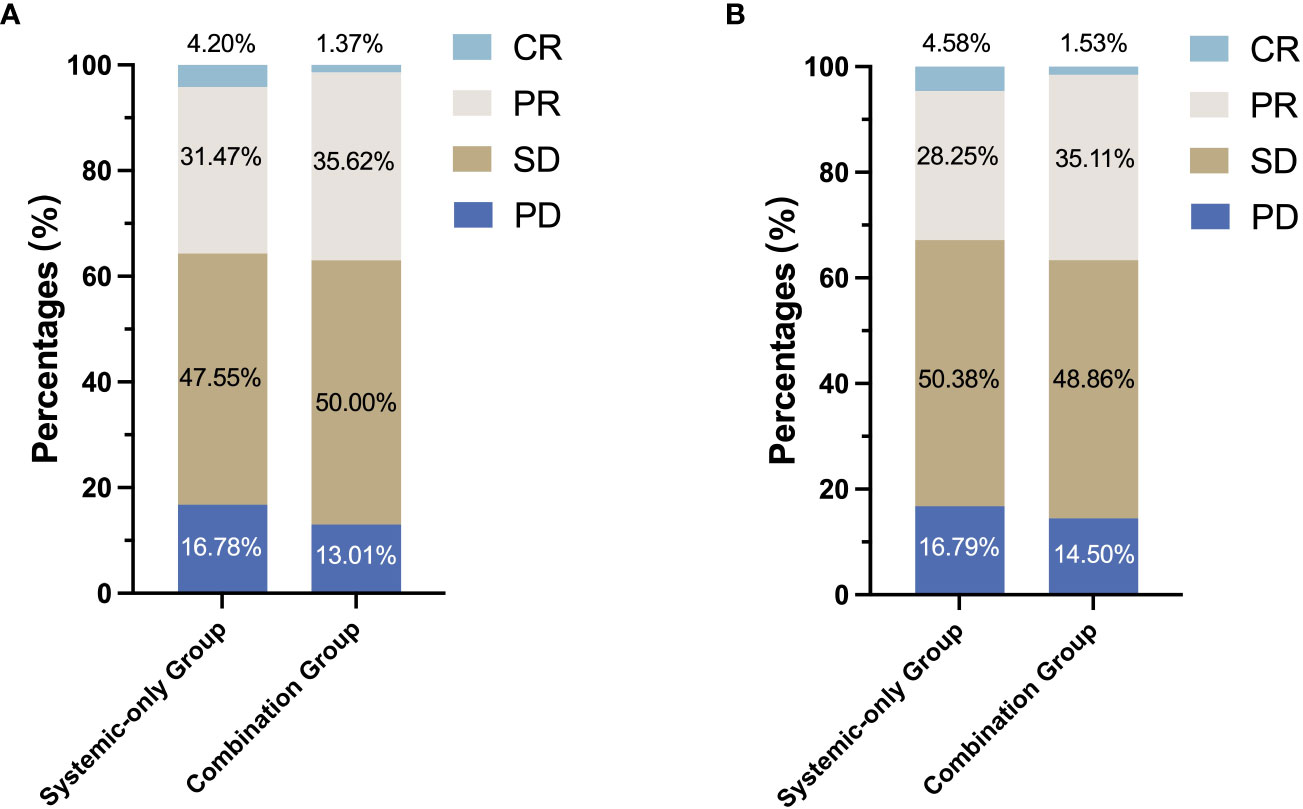

In the combination group, the best response was a CR in two patients, a PR in 52 patients, and SD in 73 patients, providing an ORR of 37.0%. The best response in the systemic-only group was a CR in six patients, a PR in 45 patients, and SD in 68 patients, giving an ORR of 32.9% (Figure 3A). Tumors in 25 patients (17.1%) in the combination group and 22 patients (15.4%) in the systemic-only group were successfully converted to become surgically resectable. Response and conversion rates did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 1).

Figure 3 Tumor responses rates based on RECIST v1.1 in the systemic-only group and the combination group (A) before PSM and (B) after PSM. RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; PSM, propensity score matching; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

In multivariate analyses, combination therapy was significantly and independently associated with improved OS compared with systemic therapy (HR, 0.286; 95% CI, 0.100 to 0.813; P = 0.019). Furthermore, objective tumor response was significantly associated with increases in both OS (HR, 0.319; 95% CI, 0.133 to 0.762; P = 0.010) and PFS (HR 0.432; 95% CI, 0.219 to 0.851; P = 0.015) (Table 2).

After 1:1 PSM for tumor size, hepatic vein invasion and ECOG PS, all baseline variables were comparable across the two treatment groups (all P > 0.050) (Table 1). The distributions of imbalanced variables before and after PSM adjustment are shown in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Figure S1). Of note, following PSM adjustment, OS in the combination group remained significantly longer, with 12-, 24-, and 36-month OS rates of 83.2, 62.4, and 59.1%, compared with 72.2, 49.5, and 42.9% in the systemic-only group (HR, 0.612; 95% CI, 0.390 to 0.957; P = 0.031; Figure 2C). PFS was not significantly different between the two groups after PSM adjustment, with 12-, 24-, and 36-month PFS rates of 48.0, 33.3, and 36.6%, respectively, for the combination group and 55.0%, 37.9% and 26.6% for the systemic-only group (HR, 1.137; 95% CI, 0.82 to 1.576; P = 0.442; Figure 2D). Furthermore, the ORR was not significantly different between the two groups after PSM adjustment (36.6% vs. 32.8%, P = 0.604; Figure 3B).

After IPTW (Supplementary Figure S2), baseline tumor size, prevalence of hepatic vein invasion and ECOG PS were similar between the two groups (P > 0.050) (Supplementary Table S1). The OS remained significantly longer in the combination group with 12-, 24- and 36-month OS rates of 83.1, 61.0, and 58.2%, respectively, compared with 68.5, 49.3, and 32.9% for the systemic-only group (HR, 0.539; 95% CI, 0.116 to 0.961; P = 0.008; Figure 2E). Consistent results were obtained in analyses of PFS and ORR before and after IPTW adjustment (Figure 2F; Supplementary Table S1, respectively).

In subgroup analyses, patients without extrahepatic metastasis significantly benefited from combination versus systemic therapy (OS HR, 0.497; 95% CI, 0.289 to 0.853; P = 0.012; Figure 4), whereas no difference was observed in patients with extrahepatic metastasis (OS HR, 0.278; 95% CI, 0.337 to 1.364; P = 0.268; Figure 4). Interestingly, a significantly longer OS was demonstrated with combination versus systemic therapy among patients with liver lesions exceeding the up-to-seven criteria (HR, 0.588; 95% CI, 0.356 to 0.971; P = 0.033; Figure 4), while no significant difference was observed among patients within these criteria (HR, 0.261; 95% CI, 0.250 to 1.388; P = 0.261; Figure 4). Additionally, OS was significantly longer in the combination group versus the systemic-only group for patients with baseline AFP ≥ 400 ng/ml (HR, 0.567; 95% CI, 0.338 to 0.952; P = 0.028; Figure 4), but not in those with AFP < 400 ng/ml (HR, 0.494; 95% CI, 0.229 to 1.065; P = 0.079; Figure 4). OS was comparable between patients who received TACE or HAIC as their concurrent TRIT with systemic therapy (HR, 0.742; 95% CI, 0.382 to 1.441; P = 0.384; Figure 4).

Figure 4 Forest plot of subgroup analysis for overall survival. AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; TRIT, transcatheter intra-arterial therapies; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; HAIC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, confidence interval.

No treatment-related deaths occurred in either treatment group. Severe (i.e., grade 3/4) TRAEs were reported in 16 patients (11.0%) in the combination group and 17 patients (11.9%) in the systemic-only group (P = 0.223). There was no significant difference between the two groups in the types of severe TRAEs reported (P = 0.139) (Table 3).

To our knowledge, this is the first real-world, multi-center study to compare the efficacy and safety of TKIs plus PD-1 antibodies, with or without concurrent TRIT, for the first-line treatment of patients with uHCC. Patients in the combination group demonstrated significantly superior OS compared with systemic therapy alone in unadjusted analyses, as well as following PSM and IPTW adjustment. Multivariate analyses revealed that concurrent TRIT was significantly and independently associated with longer OS in this cohort of patients with uHCC of CNLC stages IIb to IIIb.

Therapeutic options for uHCC have evolved dramatically in recent years. Following the demonstration of a significant benefit of lenvatinib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy for advanced HCC in the REFLECT study, several newer TKIs and PD-1 antibodies, alone or in combination, have been recommended in the first-line setting (6, 8, 26, 27). Following the failure of studies of single-agent PD-1 antibodies to show improvements in tumor control and initial skepticism regarding combination regimens, the Imbrave150 study demonstrated that atezolizumab plus bevacizumab increased 12-month OS by 12.6% compared with sorafenib, with a similar incidence of adverse events between groups (8). Moreover, in the HIMALAYA study, tremelimumab, an anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 monoclonal antibody, combined with durvalumab, an anti-programmed death ligand-1 monoclonal antibody, prolonged median OS by 3.0 months compared with sorafenib, in patients with uHCC (26). More recently, the phase III LEAP-002 study of first-line lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab, compared with lenvatinib monotherapy, achieved the longest median OS (21.2 months) for dual therapy ever reported in the treatment of advanced HCC, further supporting the concept of combining systemic therapies in patients ineligible for curative therapy (27).

HCC is a hypervascular tumor that derives most of its blood supply from the hepatic artery. Accordingly, TRIT, including TACE and FOLFOX-HAIC, has been shown to facilitate local tumor control and provide long-term clinical benefits (28). TACE with cisplatin or doxorubicin has demonstrated favorable OS in the treatment of uHCC and is recommended for asymptomatic, large, or multifocal HCC without macrovascular invasion or extrahepatic metastasis (3, 29, 30). Additionally, several recent randomized clinical trials have shown FOLFOX-HAIC is another potent TRIT that improves survival outcomes compared with the guideline-recommended TACE or sorafenib in the treatment of large and advanced HCC tumors and have enabled patient eligibility criteria for TRIT to be enriched (5, 31). For example, in patients with large, unresectable HCC tumors exceeding 7 cm, FOLFOX-HAIC prolonged the median OS by 7.0 months compared with TACE (HR, 0.580; 95% CI, 0.450 to 0.750; P < 0.001) with a lower incidence of adverse events (P = 0.030) (5).

Given the encouraging efficacy and acceptable safety of TRIT in uHCC treatment, the administration of TRIT alongside systemic therapy has the potential to enhance liver lesion control with manageable safety. Indeed, the LAUNCH trial demonstrated that first-line lenvatinib plus TACE significantly improved median OS by 6.3 months compared with lenvatinib alone (P < 0.001), with a pronounced benefit observed in patients with tumor thrombosis (32). Another study found that sorafenib plus FOLFOX-HAIC provided a median OS of 13.37 months, which is significantly longer than with sorafenib monotherapy, at 7.13 months (P < 0.001) (13). Moreover, the potential to further evolve combination approaches was illustrated in a single-arm study in which lenvatinib plus sintilimab plus TACE led to a median OS of 23.6 months (95% CI, 22.2 to 25.0 months) in patients with uHCC (33). Nonetheless, evidence regarding the administration of both TKIs and PD-1 antibodies in combination with TRIT is limited.

While a previous small-scale, single-center study has shown the superiority of combination therapy with a TKI, ICI and TRIT over systemic therapy (34), the present study provides the first multi-center, head-to-head comparison of OS between dual systemic therapy with TKIs and PD-1 antibodies, with or without TRIT, in patients with uHCC. After comprehensive analyses incorporating PSM and IPTW adjustment to account for imbalances in patient characteristics, combination treatment consistently demonstrated an OS benefit over systemic-only therapy, while PFS and the incidence of TRAEs were comparable between groups. Interestingly, patients in the combination group had larger tumors, worse ECOG PS, and more hepatic vein invasion than patients in the systemic-only group. This may reflect a tendency for physicians to administer concurrent TRIT in patients with higher liver tumor burden, with the goal of improving primary liver lesion control to preserve liver function and so prolong survival. Patients with higher intrahepatic tumor burden tended to rapid progression, presenting originally shorter PFS and lower ORR. The concurrent TRIT could help to fix the unfavorable to some extent, resulting in similar PFS and ORR of the two groups. The lack of a significant difference between groups in PFS may also be partly explained by the generally shorter follow-up interval (4–6 weeks) between assessments in patients who received TRIT than those who received systemic therapy alone (6–8 weeks).

Our subgroup analyses indicated that the OS benefit from concurrent TRIT was derived by patients with a greater local tumor burden, including those whose liver lesions exceeded the up-to-seven criteria, and those without extrahepatic metastases. In these patients with aggressive liver tumors, improvement in local tumor control with concurrent TRIT may better preserve liver function, which could have a critical impact on OS in this setting. Although FOLFOX-HAIC was reported to improve OS versus TACE in a randomized phase III study in patients with large uHCC tumors (5), we found no survival difference between patients who received TACE or FOLFOX-HAIC as concurrent TRIT with dual systemic therapy. In combination with systemic therapy, both TACE and HAIC are reported to improve disease control and prognosis in patients with uHCC in single-center or retrospective studies (35–37). The results of the present study therefore demonstrate that the combination of TKIs plus PD-1 antibodies with concurrent TRIT is a feasible strategy that holds promise for the treatment of patients with uHCC.

This study has several limitations. First, the combinations of TKIs and PD-1 antibodies are not considered standard regimens for the first-line treatment of uHCC in Western countries. Second, since bevacizumab plus atezolizumab was not approved in China until the end of 2020, this regimen was infrequently used in the present dataset (11, 38). Third, a lack of independent tumor assessments or standardization of TRIT protocols between different centers may have impacted the reliability of PFS and ORR estimates in this retrospective, multi-center study. Finally, the study included predominantly patients with HBV-related HCC, who are known to benefit more from immune-based therapies than those with HCC of other eiologies (39). Thus, our findings should be independently verified in broader populations, including patients outside China.

In conclusion, TKIs plus PD-1 antibodies combined with concurrent TRIT were associated with superior OS compared with dual systemic therapy alone in Chinese patients with uHCC, especially in those with a high-intrahepatic tumor load and no extrahepatic metastasis. Prospective studies with a larger sample size and longer follow-up are required to validate these findings.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center and Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (Approval No. B2022-301-01 and B20202-195R, respectively). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

YP, XZ, HS and LX designed experiments and drafted the manuscript. JL, JZ, WZ, SS, RJ, HL, FY, KH, DX, YZ, LZ, BCX, ZC, YC, YYZ, XL, MK, TS, BDX and KW collected the cases. XZ, HS and LX approved the final version. The China Liver Cancer Study Group Young Investigators (CLEAP) provide the platform for data maintenance. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1138355/full#supplementary-material

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

2. Roayaie S, Jibara G, Tabrizian P, Park J-W, Yang J, Yan L, et al. The role of hepatic resection in the treatment of hepatocellular cancer. Hepatology. (2015) 62:440–51. doi: 10.1002/hep.27745

3. Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado Á, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: the 2022 update. J Hepatol (2022) 76:681–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.018

4. Zhou J, Sun H, Wang Z, Cong W, Wang J, Zeng M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (2019 edition). Liver Cancer (2020) 9:682–720. doi: 10.1159/000509424

5. Li Q-J, He M-K, Chen H-W, Fang W-Q, Zhou Y-M, Xu L, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin versus transarterial chemoembolization for Large hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol (2022) 40:150–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00608

6. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han K-H, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. (2018) 391:1163–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1

7. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc J-F, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2008) 359:378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857

8. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim T-Y, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. New Engl J Med (2020) 382:1894–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745

9. Finn RS, Ikeda M, Zhu AX, Sung MW, Baron AD, Kudo M, et al. Phase ib study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol (2020) 38:2960–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00808

10. Rognoni C, Ciani O, Sommariva S, Facciorusso A, Tarricone R, Bhoori S, et al. Trans-arterial radioembolization in intermediate-advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: systematic review and meta-analyses. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:72343–55. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11644

11. Bruix J, Tak W-Y, Gasbarrini A, Santoro A, Colombo M, Lim H-Y, et al. Regorafenib as second-line therapy for intermediate or advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: multicentre, open-label, phase II safety study. Eur J Cancer (2013) 49:3412–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.05.028

12. Kelley RK, Sangro B, Harris W, Ikeda M, Okusaka T, Kang Y-K, et al. Safety, efficacy, and pharmacodynamics of tremelimumab plus durvalumab for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: randomized expansion of a phase I/II study. J Clin Oncol (2021) 39:2991–3001. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03555

13. He M, Li Q, Zou R, Shen J, Fang W, Tan G, et al. Sorafenib plus hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin vs sorafenib alone for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein invasion: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol (2019) 5:953–60. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0250

14. Zhu X-D, Huang C, Shen Y-H, Ji Y, Ge N-L, Qu X-D, et al. Downstaging and resection of initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with tyrosine kinase inhibitor and anti-PD-1 antibody combinations. Liver Cancer (2021) 10:320–9. doi: 10.1159/000514313

15. Chen X, Li W, Wu X, Zhao F, Wang D, Wu H, et al. Safety and efficacy of sintilimab and anlotinib as first line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (KEEP-G04): a single-arm phase 2 study. Front Oncol (2022) 12:909035. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.909035

16. Lai ZC, He MK, Bu XY, Xu YJ, Huang YX, Wen DS, et al. Lenvatinib, toripalimab plus hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy in patients with high-risk advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a biomolecular exploratory, phase II trial. Eur J Cancer (2022) 174:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.07.005

17. Liu D, Mu H, Liu C, Zhang W, Cui Y, Wu Q, et al. Hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) combined with sintilimab and bevacizumab biosimilar (IBI305) for initial unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): a prospective, single-arm phase II trial. J Clin Oncol (2022) 40:4073. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.4073

18. Zhang J, Zhang X, Mu H, Yu G, Xing W, Wang L, et al. Surgical conversion for initially unresectable locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma using a triple combination of angiogenesis inhibitors, anti-PD-1 antibodies, and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy: a retrospective study. Front Oncol (2021) 11:729–64. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.729764

19. Bruix J, Reig M, Sherman M. Evidence-based diagnosis, staging, and treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. (2016) 150:835–53. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.041

20. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin Oncol (1982) 5:649–55. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014

21. Ren Z, Xu J, Bai Y, Xu A, Cang S, Du C, et al. Sintilimab plus a bevacizumab biosimilar (IBI305) versus sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENT-32): a randomised, open-label, phase 2-3 study. Lancet Oncol (2021) 22:977–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00252-7

22. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer (2009) 45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026

23. de Ataide EC, Garcia M, Mattosinho TJAP, Almeida JRS, Escanhoela CAF, Boin IFSF. Predicting survival after liver transplantation using up-to-seven criteria in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplant Proc (2012) 44:2438–40. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.07.006

24. Rubin DB, Thomas N. Matching using estimated propensity scores: relating theory to practice. Biometrics. (1996) 52:249–64. doi: 10.2307/2533160

25. Aubert CE, Ha J-K, Kim HM, Rodondi N, Kerr EA, Hofer TP, et al. Clinical outcomes of modifying hypertension treatment intensity in older adults treated to low blood pressure. J Am Geriatr Soc (2021) 69:2831–41. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17295

26. Abou-Alfa GK, Lau G, Kudo M, Chan SL, Kelley RK, Furuse J, et al. Tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. NEJM Evidence (2022) 1:EVIDoa2100070. Available from: doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/EVIDoa2100070

27. Finn RS. Primary results from the phase III LEAP-002 study: lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus lenvatinib as first- line (1L) therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC). Ann Oncol (2022) 33:S808–69. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.08.031

28. Cheng Y-T, Jeng W-J, Lin C-C, Chen W-T, Sheen I-S, Lin C-Y, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of tumor feeding artery before target tumor ablation may reduce local tumor progression in hepatocellular carcinoma. BioMed J (2016) 39:400–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2016.11.002

29. Malagari K, Pomoni M, Kelekis A, Pomoni A, Dourakis S, Spyridopoulos T, et al. Prospective randomized comparison of chemoembolization with doxorubicin-eluting beads and bland embolization with BeadBlock for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol (2010) 33:541–51. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9750-0

30. Meyer T, Kirkwood A, Roughton M, Beare S, Tsochatzis E, Yu D, et al. A randomised phase II/III trial of 3-weekly cisplatin-based sequential transarterial chemoembolisation vs embolisation alone for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer (2013) 108:1252–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.85

31. Lyu N, Wang X, Li J-B, Lai J-F, Chen Q-F, Li S-L, et al. Arterial chemotherapy of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a biomolecular exploratory, randomized, phase III trial (FOHAIC-1). J Clin Oncol (2022) 40:468–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01963

32. Peng Z, Fan W, Zhu B, Wang G, Sun J, Xiao C, et al. Lenvatinib combined with transarterial chemoembolization as first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III, randomized clinical trial (LAUNCH). J Clin Oncol (2023) 41(1):117–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00392

33. Cao F, Yang Y, Si T, Luo J, Zeng H, Zhang Z, et al. The efficacy of TACE combined with lenvatinib plus sintilimab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter retrospective study. Front Oncol (2021) 11:783480. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.783480

34. Mei J, Tang Y-H, Wei W, Shi M, Zheng L, Li S-H, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with PD-1 inhibitors plus lenvatinib versus PD-1 inhibitors plus lenvatinib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol (2021) 11:618206. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.618206

35. Fu Z, Li X, Zhong J, Chen X, Cao K, Ding N, et al. Lenvatinib in combination with transarterial chemoembolization for treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC): a retrospective controlled study. Hepatol Int (2021) 15:663–75. doi: 10.1007/s12072-021-10184-9

36. Xia W-L, Zhao X-H, Guo Y-, Cao G-S, Wu G, Fan W-J, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization combined with apatinib with or without PD-1 inhibitors in BCLC stage c hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter retrospective study. Front Oncol (2022) 12:961394. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.961394

37. Cai M, Huang W, Huang J, Shi W, Guo Y, Liang L, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization combined with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. Front Immunol (2022) 13:848387. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.848387

38. Galle PR, Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Zhu AX, Kim T-Y, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sorafenib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (IMbrave150): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 22(7):991–1001. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00151-0

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, transcatheter intra-arterial therapies, systemic therapy, combination therapy, prognosis

Citation: Pan Y, Zhu X, Liu J, Zhong J, Zhang W, Shen S, Jin R, Liu H, Ye F, Hu K, Xu D, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Xing B, Zhou L, Chen Y, Zeng Y, Liang X, Kuang M, Song T, Xiang B, Wang K, Sun H, Xu L and China Liver Cancer Study Group Young Investigators (CLEAP) (2023) Systemic therapy with or without transcatheter intra-arterial therapies for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a real-world, multi-center study. Front. Immunol. 14:1138355. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1138355

Received: 05 January 2023; Accepted: 12 April 2023;

Published: 26 April 2023.

Edited by:

Xu Jing, Karolinska Institutet (KI), SwedenReviewed by:

Wang-Zhong Li, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Pan, Zhu, Liu, Zhong, Zhang, Shen, Jin, Liu, Ye, Hu, Xu, Zhang, Chen, Xing, Zhou, Chen, Zeng, Liang, Kuang, Song, Xiang, Wang, Sun, Xu and China Liver Cancer Study Group Young Investigators (CLEAP). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huichuan Sun, c3VuLmh1aWNodWFuQHpzLWhvc3BpdGFsLnNoLmNu; Li Xu, eHVsaUBzeXN1Y2Mub3JnLmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.