- 1Department of Immunology, School of Medicine, UConn Health, Farmington, CT, United States

- 2Arthritis and Clinical Immunology Program, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, OK, United States

- 3Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Oklahoma Health Science Center, Oklahoma City, OK, United States

- 4Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States

- 5Academy of Integrative Medicine, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 6Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, United States

Neutrophils are the most abundant leukocyte in human blood. They are critical for fighting infections and are involved in inflammatory diseases. Mitochondria are indispensable for eukaryotic cells, as they control the biochemical processes of respiration and energy production. Mitochondria in neutrophils have been underestimated since glycolysis is a major metabolic pathway for fuel production in neutrophils. However, several studies have shown that mitochondria are greatly involved in multiple neutrophil functions as well as neutrophil-related diseases. In this review, we focus on how mitochondrial components, metabolism, and related genes regulate neutrophil functions and relevant diseases.

Introduction

Neutrophils play a central role in the innate immune system. They are the most abundant circulating white blood cells in human blood. They are recruited to infection sites or damaged tissue by a recruitment cascade that involves rolling, arrest, spreading, intravascular crawling, transendothelial migration, and in-tissue migration/chemotaxis (1–4). Neutrophils have various methods to kill invading microorganisms, including phagocytosis (5–7), neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs; and process of NETosis) (6, 8, 9), degranulation (6, 10), and respiratory burst (11, 12).

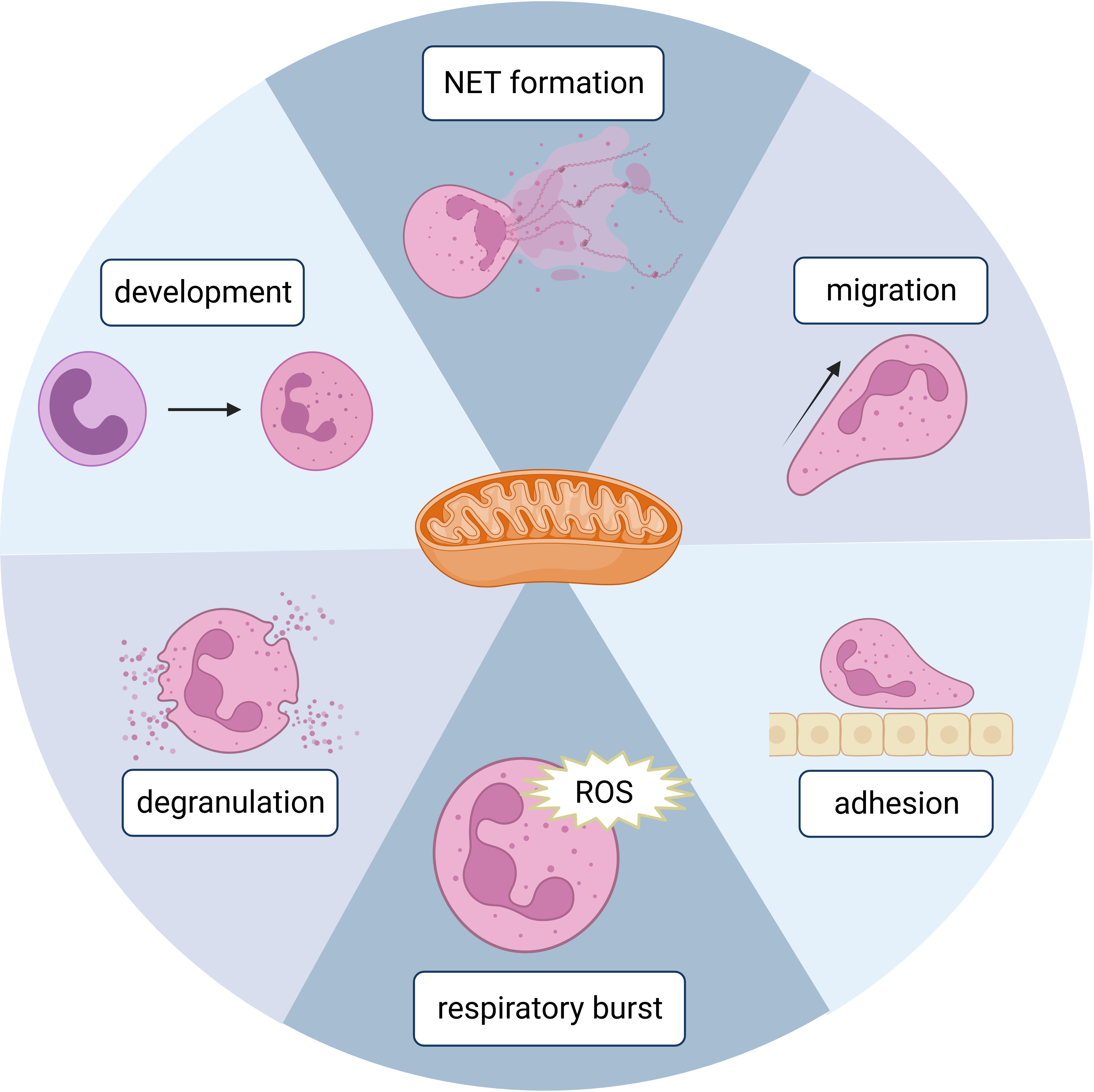

Mitochondria are one of the most important organelles in eukaryotic cells. They are the powerhouses of eukaryotic cells since this is where adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is produced efficiently by oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Mitochondria are also central signaling hubs that regulate cell death (13). Until 2003, mitochondria had been underestimated for their role in neutrophils. Utilizing multiple specific dyes, Fossati et al. identified mitochondria in neutrophils as complex networks extending through the cytoplasm (14), which kickstarted intensive research on neutrophil mitochondria. Mitochondria are now known to have several important functions in neutrophils, such as NET formation, adhesion/migration, respiration burst, development/differentiation, and death, which will be discussed in this review (Figure 1). We will also discuss diseases related to dysfunctions of neutrophil mitochondria.

Figure 1 A schematic figure showing the involvement of mitochondria in different neutrophil functions. Created in BioRender.com.

Respiratory burst

Neutrophil respiratory burst, which involves the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), plays an important role in controlling infections and the progression of inflammatory diseases. Here, the term ROS refers to reactive non-radical derivatives of molecular oxygen, such as H2O2, and reactive free radical species, such as O2–.

N-Formyl peptides (e.g., N-formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-phenylalanine; fMLP) can stimulate neutrophil oxidative burst and produce ROS via formyl peptide receptors (FPRs) (15). Oligomycin and cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) that inhibit mitochondrial OXPHOS can reduce fMLP-induced neutrophil ROS production (15). Dihydrorhodamine (DHR) 123 was used to measure ROS production in this study. However, since mitochondrial OXPHOS also produces ROS (mitochondrial ROS, mROS), whether DHR123-indicated ROS are from mitochondrial OXPHOS or oxidative burst is unclear (15).

Another study showed that scavenging of mROS with mitochondria-targeted antioxidant SkQ1 could decrease neutrophil intracellular ROS upon cytochalasin D/fMLP stimulation in a dose-dependent manner (16). Then they investigated whether mROS directly contributes to the intracellular ROS or regulates intracellular ROS through an indirect mechanism. Intracellular ROS was labeled by the redox-sensitive dye 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein-diacetate (DCFH-DA), which can be cleaved by intracellular esterases to form dichlorofluorescein and become fluorescent upon oxidation. Using membrane-impermeable catalase to scavenge extracellular ROS, they demonstrated that fMLP predominantly induced extracellular ROS formation, and the DCFH-DA-labeled intracellular ROS was coming from the penetration of extracellular ROS but not mROS. They also used MitoSOX to specifically label mROS, which were shown not to significantly contribute to fMLP-induced intracellular ROS accumulation. Thus, these results indicated that mROS does not directly contribute to intracellular ROS but is implicated in the NADPH oxidase (NOX)-dependent generation of extracellular ROS or transportation of extracellular ROS to the cytoplasm (16). Other mechanisms of how mROS regulate oxidative burst need further investigation. This study also found that SkQ1 can inhibit cytochalasin D/fMLP-induced degranulation based on decreased surface expression of azurophilic granule marker CD63 and specific granule marker CD66b, suggesting that mROS may influence granule exocytosis (16).

A recent study found that inhibition of complex III (cytochrome c reductase) with antimycin A can significantly reduce neutrophil superoxide O2– production (17). MitoTEMPO can accumulate in mitochondria and reduce superoxide. Pre-incubation of neutrophils with MitoTEMPO can significantly attenuate neutrophils’ ability to kill Staphylococcus aureus. This effect is not enhanced by co-incubation with MitoTEMPO and antimycin A, suggesting that electron transport complex III is critical for mROS production and required for the bactericidal function of neutrophils (17). Rice et al. found that mitochondria contribute to prolonged H2O2 production. Moreover, if neutrophils have limited glucose, mitochondria can utilize fatty acid metabolism to maintain NADPH levels to support NOX-dependent respiratory burst instead of producing mROS (18).

NET formation

NETs were discovered while studying the unique antibacterial mechanisms of neutrophils. When neutrophils were stimulated with interleukin-8 (IL-8), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Brinkmann et al. found that extracellular filamentous structures containing DNA and histones can ensnare bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella typhimurium, or Shigella flexneri (8). The process of formation of NETs is called NETosis, which is a unique form of cell death in neutrophils (19). NETosis is essential for the host to fight against microorganisms. However, it also contributes to many pathological processes, including cancer, thrombosis, and autoimmune diseases (20, 21).

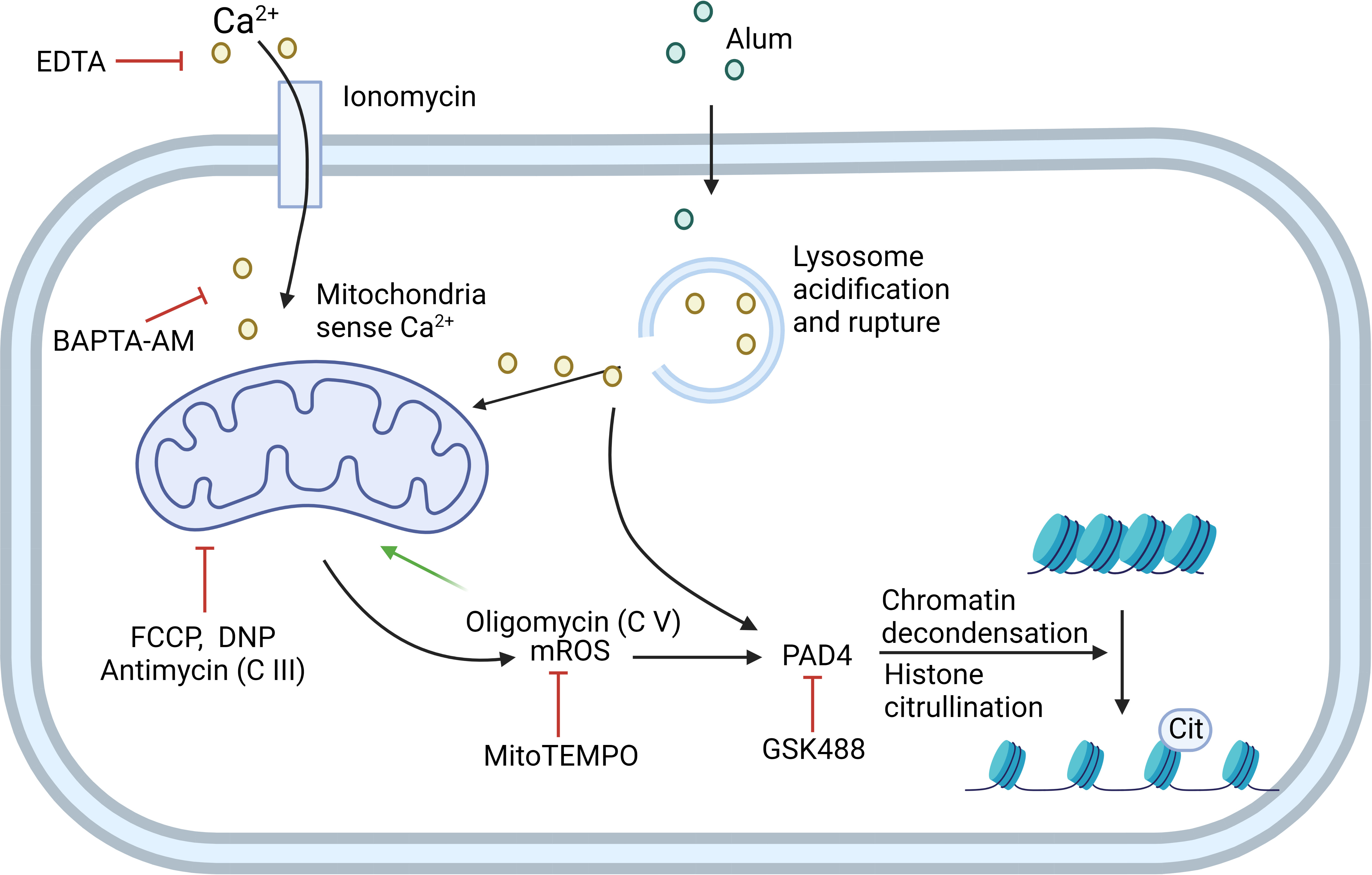

Multiple stimuli can initiate NET formation, including nicotine (22), LPS, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), PMA, ionomycin, and alum. However, each initiates NET formation using a different mechanism, which can be categorized into two types based on the dependence of NOX: NOX-dependent and NOX-independent (Figure 2).

Figure 2 NOX-independent NETosis can be induced by ionomycin or alum. Ionomycin works as a Ca2+ ionophore to transfer extracellular calcium (Ca2+) into cells. Alum causes lysosome acidification and rupture, which then leads to Ca2+ release. Mitochondria sense the elevation of Ca2+ in the cytoplasm and generate mitochondrial ROS (mROS). Cytoplasmic Ca2+ and mROS are both required to activate PAD4, which further induces histone citrullination and chromatin decondensation. EDTA and BAPTA-AM can chelate extracellular and cytoplasmic Ca2+, respectively, to inhibit this process. Mitochondrial inhibitor FCCP, DNP, and mitochondria complex III inhibitor antimycin can inhibit this process. mROS-specific scavenger MitoTEMPO also inhibits the pathway. Mitochondria complex V inhibitor oligomycin inhibits the retrograde proton transport, therefore leading to the increased MMP which drives enhanced NETosis. GSK488 is an inhibitor of PAD4. C III: complex III; C V: complex V. Created in BioRender.com.

PMA has been used as a stable NETosis inducer to study the mechanisms of NOX-dependent NETosis. The indispensable role of NOX was shown by using the NOX2 inhibitor DPI to significantly reduce PMA-induced NETosis, and that neutrophils from chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) patients—that have mutations in one of the genes encoding the components of the Nox2 NADPH oxidase complex—lose their ability for NETosis (19). PMA activates protein kinase C (PKC), which subsequently activates NOX2 through c-Raf/MEK/Erk to produce cytosolic ROS (23). The release of neutrophil elastase (NE) and myeloperoxidase (MPO) follows the production of ROS, causing specific histone degradation and chromatin decondensation. However, signaling components between ROS and translocation of NE from azurophilic granules and to the nucleus are not clear (24). During this process, although PMA can induce the production of mROS, PMA-induced mROS cannot drive NETosis (25). Why ROS from different sources have distinct effects on NETosis is not clear.

PMA-induced NOX-dependent NETosis needs glucose. Human neutrophils cultured in glucose-free media are unable to form NETs. Further, glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxyglucose, but not OXPHOS inhibitor oligomycin, abolishes neutrophil’s ability to undergo PMA-induced NETosis (26). GM-CSF plus complement factor 5a (C5a)/LPS-dependent NET formation is also NOX-dependent, which is demonstrated by using NOX inhibitor DPI and neutrophils from CGD patients (27). However, it has also been shown that electron transport complex I localized on the inner membrane of mitochondria (IMM) is critical for GM-CSF plus C5a/LPS-dependent NET formation (28). This is because complex I produces nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), which participates in glycolysis to generate ATP. Blocking complex I with rotenone or piericidin A but not complex III or complex V leads to the inability of mouse and human neutrophils to release DNA upon stimulation with GM-CSF plus C5a (28). Optic atrophy 1 mitochondrial dynamin-like GTPase (OPA1) is one of the “mitochondria-shaping” proteins, bound to the outer space of the inner mitochondrial membrane. Patients with mutated OPA1 can develop autosomal dominant optic atrophy (ADOA). The neutrophils from some ADOA patients or OPA1-deficient mice cannot release DNA following GM-CSF plus C5a stimulation. Amini et al. further found that deficiency of OPA1 leads to the reduced activity of complex I, therefore reducing ATP production by limiting NAD+ availability in glycolysis, resulting in the inability to release DNA to extracellular space and failure of the mitochondrial network formation (28).

Calcium ionophore ionomycin and A23187 can drive NETosis via a NOX-independent pathway. mROS, but not NOX2-dependent ROS, is required for NOX-independent NETosis in dHL60 cells and human neutrophils (29). Mitochondrial uncouplers, such as 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) and carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), dissipate the proton gradient and inhibit mitochondrial ATP synthesis. DNP and FCCP inhibit NOX-independent NETosis in a dose-dependent manner (29). Takishita et al. used dideoxycytidine to generate mitochondria-deficient ρ0 cells from HL60 cells. They also found that ρ0 cells release less DNA compared to neutrophil-like HL60 cells after stimulating with A23187, but not PMA, suggesting that mitochondria are crucial for NOX-independent NETosis (30). MitoTEMPO can attenuate A23187-induced NET formation, suggesting that mROS is the key part of the NOX-independent pathway (30, 31).

Reithofer et al. proposed a mechanism of alum-induced NETosis regarding mitochondrial membrane potential as the major driving force (32). They first found that positively charged alum has a similar effect with calcium ionophore ionomycin on activating NETosis. However, alum-induced NETosis does not require extracellular Ca2+ like ionophores. Instead, the rupture of lysosomes followed by the release of lysosome-stored Ca2+ leads to an increased production of mROS. The authors further investigated the role of the respiration chain in mROS production and NETosis. They found that rotenone, the inhibitor of complex I, does not affect alum-induced NETosis, whereas antimycin, an inhibitor of complex III, decreased alum-induced NETosis to a similar extent as DNP. The inhibition of complex V inhibits retrograde proton transport, increases mitochondrial membrane potential, and enhances alum-induced NETosis. This suggests that alum/ionophore-induced NETosis uses a different pathway from C5a/LPS-induced NETosis, which is dependent on complex I-controlled, glycolytic ATP production (32).

Ca2+ signals were found important for NOX-independent NETosis. Mitochondria will sense Ca2+ either from extracellular space or intracellular components like ER or lysosome and produce ROS in response to that. The uptake of Ca2+ by the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) is regulated by mitochondrial calcium uptake 1 (MICU1), which acts as a gatekeeper for Ca2+ flux through the MCU. In the MICU1 conditional KO model, MCU-mediated ion flux coincides with increased production of mitochondrial O2- in response to S. aureus, thereby causing MICU1 knockout neutrophils to undergo accelerated and more robust suicidal NETosis and decreased azurophilic granule degranulation (33). Both pharmacological and genetic evidence showed that peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4) is critical for chromatin decondensation and NETosis (34, 35). Activation of PAD4 requires both ROS and Ca2+ signaling (21).

Although NETs are mainly composed of chromosomal DNA, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) can be released to extracellular space stimulated by GM-CSF C5a (27) or ribonucleoprotein immune complexes (36), suggesting a direct involvement of mitochondria in NET formation.

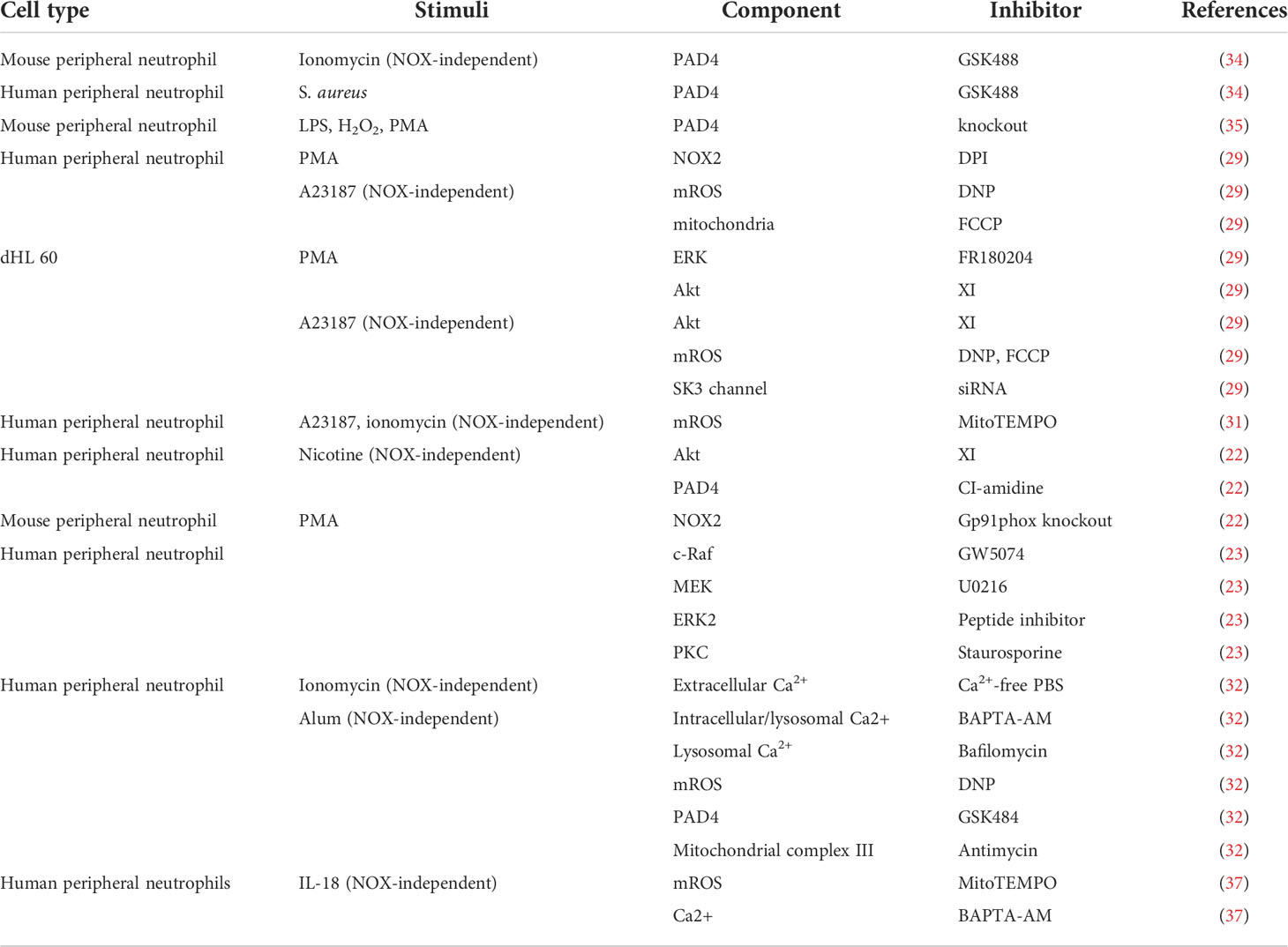

Current methods used to dissect the NETosis pathway are mainly pharmacological inhibition due to the short life of neutrophils. Here, we summarize studies showing cellular components participating in the pathway in Table 1.

Migration and adhesion

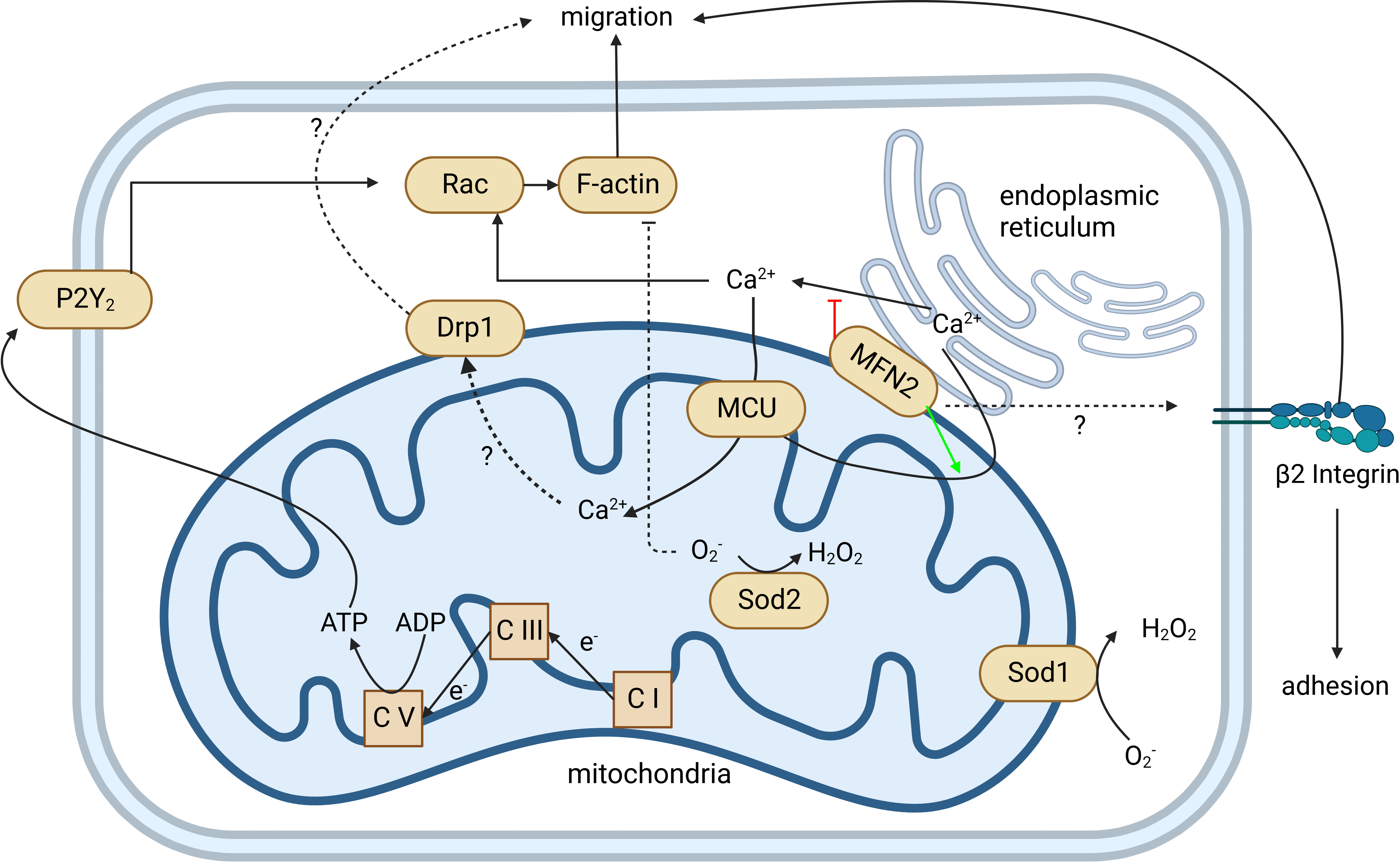

As the first-line defenders, neutrophils are critical for the innate immune system. The premise of nearly all functions of neutrophils is their ability to navigate and migrate to the infection or wound site. Mitochondria are one of the most important organelles in eukaryotic cells and work as a central hub for signal transduction and metabolism in the locomotion of most cells. Although mature neutrophils mainly rely on glycolysis for ATP (38), mitochondria still play an essential role in neutrophil locomotion (Figure 3). Inhibition of mitochondria by CCCP significantly reduced the migration speed of neutrophils and abolished chemotaxis (39). During chemotaxis, neutrophils release ATP from the leading edge of their cell surface to amplify chemotactic signals and direct cell orientation by feedback through P2Y2 nucleotide receptors and purinergic signaling (40). Mitochondria translocate to the front of the neutrophil, producing ATP to fuel the purinergic signaling (39). Meanwhile, P2Y2 receptors promote mTOR signaling and augment mitochondrial activity near the front of the cell (39). However, excessive mitochondrial ATP production induced by LPS impairs neutrophil chemotaxis (41). Unlike fMLP gradient-induced neutrophil ATP release from the leading edge of the cell surface, LPS uniformly disorganized intracellular trafficking of mitochondria, resulting in global ATP release that disrupted purinergic signaling, cell polarization, and chemotaxis. LPS-primed neutrophils cannot translocate mitochondria toward the leading edge in response to the fMLP gradient, but they can move their mitochondria uniformly toward the cell periphery. Neutrophil chemotaxis is impaired due to the lack of polarity. Removal of excessive extracellular ATP by adding apyrase can restore the chemotaxis of LPS-primed neutrophils (41). This study may partially explain the decreased chemotactic activity in neutrophils from septic patients compared to healthy controls (42). Zhou et al. first provided in vivo evidence that mitochondria regulate neutrophil motility in a zebrafish model (43). The gene encoding mtDNA polymerase, polg, was knocked out in a neutrophil-specific transgenic line and reduced the migration speed of neutrophils (43).

Figure 3 Mitochondria regulate neutrophil chemotaxis. Neutrophil mitochondria produce ATP to fuel neutrophil autocrine purinergic signaling, which is required for neutrophil chemotaxis. The production of ATP by mitochondria is through OXPHOS, coupled with an electron transport chain from complex I (C I) to complex V (C V). This is demonstrated by complexes I, III (C III), and V-specific inhibitors and/or gene knockouts. The P2Y2 receptor can recognize ATP, activate Rac, induce actin polymerization, and guide neutrophil migration. MFN2 can regulate β2 integrin activation through an unknown mechanism that affects both neutrophil adhesion and migration. MFN2 also tethers the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) with mitochondria and promotes ER Ca2+ transfer into mitochondria. Loss of MFN2 may lead to more ER Ca2+ released into the cytoplasm. Elevated cytoplasmic Ca2+ hyperactivates Rac and impairs the directionality of neutrophil migration. MCU mediates cytoplasmic and ER Ca2+ transferring into mitochondria and regulates downstream Drp1 through an unclear mechanism. Both MCU and Drp1 are involved in neutrophil migration. Sod1 and Sod2 mediate the reduction of O2- to H2O2. Loss of Sod1 or Sod2 impairs the chemotaxis of neutrophils. Created in BioRender.com.

Intracellular NOX2-dependent ROS regulates neutrophil migration by modulating actin dynamics via inducing actin glutathionylation (44). Rotenone and metformin, the mitochondria complex I inhibitors, impair the electron transport chain, increase intracellular superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, and significantly reduce neutrophil recruitment in an acute LPS-induced lung inflammation mouse model (43, 45). Both mitochondria complex I inhibitor rotenone and complex III inhibitor antimycin significantly reduced neutrophil motility in zebrafish (43). Gene knockouts of ndufs2 and uqcrc1, which are core components in complex I and III, respectively (46, 47), also resulted in a neutrophil motility reduction (43). Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase 1 and 2 (Sod1 and Sod2) mediate ROS reduction. The loss of Sod1 or 2 significantly reduces the speed of neutrophil migration, which can be rescued by N-acetylcysteine and/or MitoTEMPO. This implies that an excessive amount of intracellular ROS can inhibit neutrophil migration (43). However, this is in contrast to a certain condition where increased intracellular ROS may associate with increased neutrophil migration. Hv1/VSOP is a voltage-gated proton channel that mediates the extrusion of protons and supports intracellular ROS production (48). As expected, Hvcn1-deficient neutrophils produce more intracellular ROS. However, they exhibit stronger chemotaxis toward a low (0.25–1 µM) but not higher (10–50 µM) concentration of fMLP compared with wild-type (WT) neutrophils. Hvcn1-deficient neutrophils have a similar fMLP receptor expression and similar intracellular Ca2+ flux after fMLP stimulation compared to WT neutrophils. However, increased ERK activation was observed in Hvcn1-deficient neutrophils. The migration increase and ERK activation of Hvcn1-deficient neutrophils are NOX-dependent, supported by NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI (49). Interestingly, they did not observe a change in migration of WT neutrophils treated with DPI, suggesting that the above migration changes in mitochondrial defect neutrophils might not be ROS-dependent. However, DPI has off-target effects where it inhibits cell redox metabolism and induces oxidative stress (50).

Recent work has highlighted the role of mitochondrial calcium homeostasis in regulating cell migration (51). Mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU), located on IMM, is responsible for mitochondrial calcium uptake. MCU knockdown impaired the migration of Hs578t cells, similar to the outcome of treatment with Ru360, a potent MCU inhibitor. This finding suggests that mitochondrial Ca2+ intake regulates cell migration. However, the study of MCU in neutrophils is limited by pharmacological treatment. Two independent groups have shown that MCU regulates neutrophil migration. Activation of MCU by treatment of spermine can promote primary human neutrophil chemotaxis; inhibition of MCU by Ru360 impairs the chemotaxis of human neutrophils (52) and DMSO-differentiated HL60 (dHL60) cells (43). Dynamin-related protein (Drp1) regulates mitochondrial fission, maintaining mitochondria morphology. In some circumstances, phosphorylation of Drp1 serine 616 (S616) enhances Drp1 activity causing more mitochondria fragmentation (53). In fMLP-stimulated neutrophils, inhibition of MCU can downregulate the phosphorylation of Drp1 S616 and impair neutrophil chemotaxis. Selective suppression of Drp1 by mdivi-1 inhibits neutrophil polarization and chemotaxis but not MCU expression and Ca2+ uptake, suggesting that MCU regulates neutrophil chemotaxis partially via Drp1 (52). More genetic evidence is needed to connect Drp1 and neutrophil polarization and chemotaxis.

Intracellular Ca2+ is mainly stored in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and the juxtaposition of ER and mitochondria is essential due to the low affinity of MCU for Ca2+ (51). Mitofusin2 (MFN2) stabilizes the contact between ER and mitochondria. MFN2 is involved in neutrophil migration and adhesion. Mazaki et al. found that interfering with MFN2 expression using short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) can significantly suppress the chemotaxis of neutrophil-like dHL60 cells (54). The Deng group found that MFN2-knockdown dHL60 cells have slower chemotaxis and failed to firmly adhere to endothelial cells (55), which is consistent with an in vitro study by Mazaki et al. They also extend their finding to an in vivo zebrafish model, showing that MFN2-knockout neutrophils failed to recruit to the zebrafish tail wound, and a thioglycollate-induced mouse peritonitis model that showed fewer neutrophils was recruited to the peritoneal cavity in neutrophil-specific MFN-2 knockout mice (55). Also, transfecting an artificial ER-mitochondria tether (56), mimicking MFN2, can rescue the chemotaxis defect in MFN2 knockdown dHL60 cells (55).

In collaboration with Deng’s group, our group investigated the mechanism of the adhesion defect in MFN2 knockdown dHL60 cells (57). Using microfluidic devices, we identified that MFN2 knockdown dHL60 cells have defects on β2 integrin-dependent slow rolling and arrest but not P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1)-dependent rolling. MFN2 knockdown dHL60 cells have reduced formyl peptide receptor (FPR) expression and FPR-dependent (fMLP stimulation) and independent (PMA stimulation) β2 integrin activation defects. MFN2 knockdown dHL60 cells also show defects in actin polymerization after fMLP or PMA stimulation and Mn2+-induced cell spreading on ICAM-1. We demonstrated that MFN2 knockdown HL60 cells are deficient in differentiating to neutrophil-like dHL60 cells by assessing the nuclear morphology and maturation markers CD35 and CD87. Using the CD87 maturation marker, we found that in a mature CD87high population, MFN2 knockdown HL60 cells still show defects in cell slow rolling, adhesion, and β2 integrin activation, indicating that besides effects on differentiation, MFN2 is directly involved in regulating β2 integrin activation. Please note that in these mature populations, MFN2 only affects integrin extension (which is reported by the KIM127 antibody), but not headpiece opening (which is reported by the mAb24 antibody), under PMA stimulation. This suggests that MFN2 might be important for the conformational changes of bent-open to extended-open β2 integrins, which is an alternative allosteric pathway of β2 integrins we observed before (58–61), in addition to the conical switchblade model (62).

A migrasome is an extracellular organelle in migrating cells newly discovered by Yu’s group (63). During neutrophil migration, intracellular components can be released to extracellular space to form migrasomes, which is called mitocytosis. TSPAN9, a member of the tetraspanin family, is a key regulator of migrasome formation. In TSPAN9-/- mice, neutrophils produced fewer migrasomes than those in WT. The number of TSPAN9-/- neutrophils that can maintain mitochondria membrane potential (MMP) is reduced compared with WT, suggesting a defect in mitochondrial quality control. To directly link mitocytosis and mitochondrial quality control and exclude the other effects caused by TSPAN9 knockout, Jiao et al. compared MMP of both bone marrow and spleen neutrophils between TSPAN9-/- and WT. Since spleen neutrophils migrated a long distance while bone marrow neutrophils did not, there was less difference in MMP of bone marrow neutrophils than of spleen neutrophils, suggesting that migrasomes are mainly responsible for mitochondrial quality control (63).

Development and differentiation

During the differentiation of neutrophils, metabolism reprogramming that limits glycolytic activity while engaging mitochondrial respiration is required. Riffelmacher et al. defined five stages of neutrophil development: myeloblasts (MBs), myelocytes (MCs), metamyelocytes (MMs), band cells (BCs), and neutrophils (PMNs) (64). Taking advantage of Map1lc3b-GFP transgenic mice, they found stable autophagic flux in MBs and MCs and reduced flux in MMs and BCs, which is consistent with Tfeb and Atg7 expression changes. Their further use of Atg7fl/fl-Vav-Cre mice revealed that knockout of Atg7 causes defects in neutrophil differentiation. Similar results were seen in Atg5fl/fl-Mx1-Cre mice, indicating that this phenomenon is not Atg7-specific. Immature neutrophils only prevalent in Atg5 -/- CD45.2+ but not WT CD45.1+ cells in bone marrow chimeric mice prove that differentiation is independent of autophagy during development. Metabolic analysis showed metabolic reprogramming during G-CSF-induced neutrophil differentiation. The increased extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and decreased oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of Atg7-/- myeloblasts suggest that metabolic reprogramming limits glycolysis and engages mitochondrial respiration. Depletion of free fatty acids (FFAs) was found in Atg7-/- but not Atg7+/+ myeloblasts. Atg7-/- neutrophil lipid droplet accumulation and colocalization of autophagosomes with lipid droplets suggest that degradation of lipid droplets is mediated by autophagy. Overall, this study showed that autophagy-mediated lipolysis provides free fatty acids to support the fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) and OXPHOS pathway to produce ATP, which is essential for neutrophil differentiation (64).

Tanimura et al. found that both ER stress and unfolded-protein reactions (UPRs) are involved in neutrophil differentiation (65). During HL60 differentiation into neutrophils induced by ATRA, the ER-stress marker BiP expression is reduced. Treatment of 4-phenylbutyric acid (4-PBA), a chemical chaperone that can reduce ER stress, on HL60 cells can increase CD11b expression and induce morphological change. Detection of cleaved activating transcription factor (ATF) 6 and ATF4 suggests the activation of UPR in non-treated HL60 cells. Co-treatment of ATRA and UPR inhibitors on HL60 cells hindered its differentiation into neutrophils functionally and morphologically. Since both processes require ATP, they further investigated the role of mitochondrial ATP supply by using oligomycin. They found that disrupted neutrophil differentiation as a result of oligomycin treatment inhibited XBP-1 activation (65).

MFN2 conditional knockout/down mice were used to examine the role of MFN2 in neutrophil development. Luchsinger and colleagues found that in a competitive repopulation assay, Mfn2fl/fl-Vav-Cre and Mfn2fl/fl CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells show similar numbers in the bone marrow (66). However, they did not further study different myeloid cell populations. Zhou et al. also found that there is no significant difference in neutrophil frequencies between Mfn2fl/fl-S100A8-Cre+ and Cre- lines. Of note, both the MFN2 transcript and protein were reduced by 50% in neutrophils of these mice (55, 57). The incomplete deletion of MFN2 suggests that the S100A8-Cre line may be too late for neutrophil differentiation studies. Our group used dHL60 cells to show that the MFN2 knockdown causes a neutrophil differentiation defect based on several maturation markers, including CD35, 87, 18, and nucleus segmentation (57).

Others

Human neutrophils produced more mROS in hypoxia ex vivo (67). The addition of MitoTEMPO accelerates neutrophil apoptosis, suggesting that mitochondrial O2– is needed for neutrophil survival. Neutrophils in hypoxia also display higher mitochondrial membrane potential compared to those in normoxia. Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 2 (GPD2) is the mitochondrial component of glycerol 3-phosphate shuttle and produces mROS. To test whether GPD2 is involved in the hypoxia-induced mROS in neutrophils, Wilson et al. used iGP-1 to inhibit GPD2 and found that this inhibition led to decreased HIF-1a expression and mROS, suggesting that neutrophils use GPD2 to produce mROS and stabilize HIF-1a. Importantly, inhibition of GPD2 activity with the pro-apoptotic iGP-1 abrogates neutrophil phagocytosis of heat-killed S. aureus and degranulation, indicating that GPD2 activity is essential for neutrophil survival and key effector functions (67).

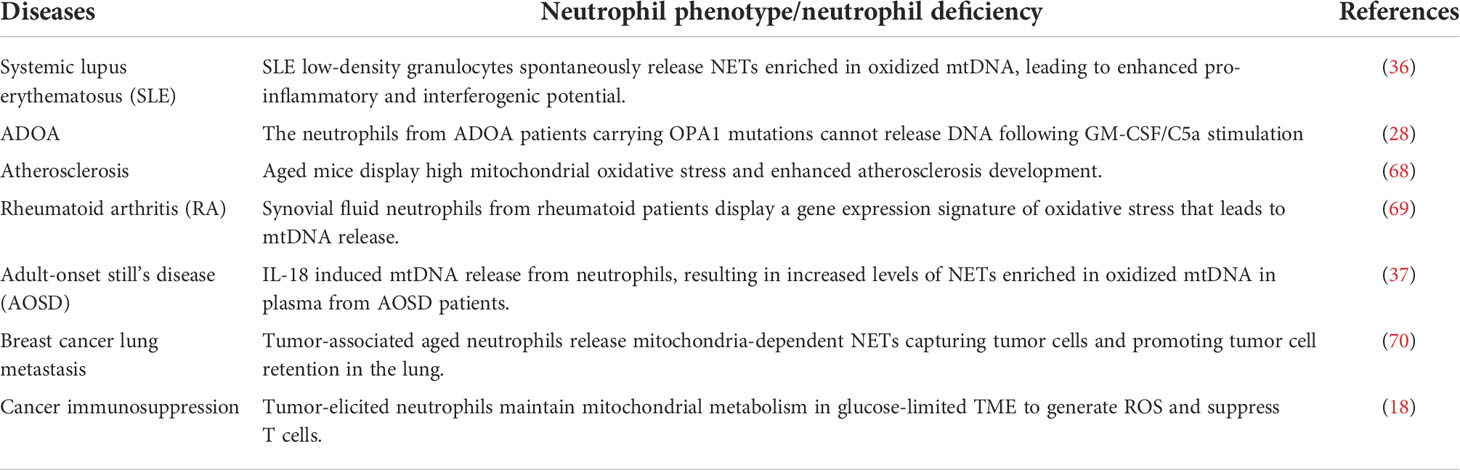

Neutrophil mitochondria-associated diseases

Neutrophil dysfunctions in mitochondria have been linked to many diseases (Table 2). Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease, and low-density granulocytes, a pro-inflammatory subset of neutrophils, from SLE patients spontaneously form more NETs. Ribonucleoprotein immune complexes (RNP-IC) are prevalent in lupus patients and can induce NETosis through an mROS-dependent manner and release oxidized mtDNA. Both in vitro and ex vivo experiments showed that oxidized mtDNA is highly inflammatory (36).

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disorder where the roles of neutrophils in pathology are well recognized (71). NETs have been observed in atherosclerosis environments in mice and humans (72). Wang et al. used lethally irradiated low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice (Ldlr−/−) with transplanted bone marrow from WT mice and transgenic mice containing mitochondrial catalase (mCAT), which can reduce mitochondrial oxidative stress (mitoOS) to examine the neutrophil-specific mitoOS in atherosclerosis in aged settings. As a result, aged mCAT→Ldlr−/− chimeric mice had significantly less aortic root atherosclerotic lesions, fewer lesional neutrophils, and decreased NETs, compared with aged controls, suggesting the pathological role of mitoOS in atherosclerosis (68).

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is another chronic inflammatory disease, where osteoclasts play a vital role in the development and progression of bone loss. The receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL) is an important factor that drives bone destruction by activating osteoclasts (73). Neutrophils highly express RANKL and activate osteoclastic bone resorption (74). Contis et al. performed a quantitative proteomic analysis of purified neutrophils isolated from synovial fluid (SF) and blood from RA patients. They found that only SF neutrophils from RA patients displayed oxidative stress gene expression signatures. They further found that SF from RA patients had a higher number of mtDNA copies than osteoarthritis patients. Moreover, the mtDNA copy number was higher in SF from RA patients with a higher disease activity score of 28, indicating that mtDNA is associated with disease severity. They also found that mtDNA can induce RANKL expression in neutrophils from healthy donors in vitro. Their findings suggest that neutrophils could release mtDNA in SF, which increases neutrophil RANKL expression and induce osteoclastic bone loss, forming an autocrine loop model contributing to RA progression (69).

Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) is a rare type of inflammatory arthritis that features fever, rash, and joint pain. Elevated levels of NETosis are found in AOSD patients (75). Liao et al. found that MitoTEMPO but not DPI can significantly inhibit AOSD patient-serum-induced NET formation, suggesting that elevated NETs in AOSD patients are mROS-dependent. They further investigated the role of IL-18 in the NETs of AOSD and found that MitoTEMPO and calcium chelator BAPTM-AM can suppress IL-18-induced NET formation. They conclude that IL-18 can induce calcium influx into neutrophils leading to mROS production and NETosis (37).

A unique subset of neutrophils regulates the lung metastasis of breast cancer in a mitochondria-dependent way (70). Tumor-associated aged neutrophils, defined by CXCR4+CD62Llow, increased in the peripheral blood and lung metastasis in the 4T1 breast tumor model and mouse mammary tumor virus-polyoma middle tumor-antigen (MMTV-PyMT) model. Further, the blood of breast cancer patients had a higher proportion of aged neutrophils compared with patients with breast fibroadenoma. Transcriptomic analysis showed that transcription factor SIRT1 is upregulated in aged neutrophils. SIRT1 can induce NETosis, which is different compared with PMA induction in the following ways: 1) SIRT1-induced NETosis is independent of NOX and PAD4 signaling; 2) mitochondrial DNA dominates the components of SIRT1-induced neutrophil extracellular traps; and 3) SIRT1 agonist SRT1720 can activate the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Immunofluorescence and scanning electron microscope images show that tumor-associated aged neutrophils can capture tumor cells and promote tumor cell retention in the lung through NETs. Moreover, the SIRT1 knockdown can significantly reduce lung metastasis (70).

In cancer, neutrophils may promote tumor progression by suppressing T-cell (76–78) and NK-cell (79) activity. However, the tumor microenvironment (TME) is usually glucose-limited. As mentioned above, neutrophils mainly use glycolysis to produce energy; therefore, the glucose-limited TME may inhibit glycolysis-dependent neutrophil functions. Using 4T1 breast cancer tumor-bearing mice, Rice et al. showed that 4T1 tumors elicit the expansion of c-Kit+ neutrophils, which may indicate immaturity (18). These c-Kit+ neutrophils have increased mitochondrial metabolism that shows higher ATP synthase-dependent and maximal OCR, greater MMP, and higher expression of complexes I and IV. Moreover, these c-Kit+ neutrophils use mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation to support stronger NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS production while limiting glucose compared to neutrophils from naïve mice. The authors further hypothesize that tumor-produced stem cell factor (SCF), a c-Kit ligand, maintains mitochondrial metabolism via the c-Kit–SCF axis. Indeed, after using c-Kit antibody blockade or SCF-null tumors, neutrophil number and mitochondrial activity are decreased. They conclude that tumor-elicited c-Kit signaling is responsible for the increased neutrophil number and neutrophil oxidative adaptation. In the coculture assay, tumor-elicited neutrophils stimulated with PMA can induce significantly more T-cell death and suppress T-cell proliferation and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production compared to neutrophils from naïve mice. Further, suppressing neutrophil glycolysis by 2-deoxy-D-glucose pretreatment did not abolish the T-cell killing ability of tumor-elicited neutrophils. Consistent with their mouse data, they found that neutrophils from peripheral blood of ovarian cancer patients have higher ATP synthase-dependent OCR.

Discussion

Neutrophil mitochondria participate in many neutrophil functions, such as respiratory burst, NET formation, migration, adhesion, differentiation/development, and degranulation. Dysfunction of neutrophil mitochondria is associated with many human diseases, such as cancer, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis. In-depth investigations of mitochondria help people realize the heterogeneous and complicated nature of the neutrophil population, providing new insights into neutrophil biology and uncovering new targets to treat diseases.

Current research studying mitochondria and their components rely heavily on pharmacological inhibitors. Thus, the off-target effects of these inhibitors may lead to misleading interpretations. Gene editing of mitochondria-specific genes (33, 43, 55, 57) provides more precise interpretations of the function of different mitochondrial components in regulating neutrophil functions. However, the global knockout of most mitochondrial genes will cause severe developmental defects. Thus, several investigations were performed in the neutrophil-like HL60 cell line. Whether these findings are consistent in primary neutrophils remains to be further investigated. The conditional knockout using the Cre-loxP system provides a tool to study mitochondrial components in mouse neutrophils. Some cres, such as MRP8-cre (S100a8-cre) (80, p.; 55, 81) and Ly6G-cre (82, 83), are specific for neutrophils. The LysM-cre (80, 84, 85) targets both neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages. Since neutrophils are short-lived cells, even the genes of mitochondrial components are knocked out, and some cres are not efficient in eliminating protein expression of mitochondrial components. For example, in our study using MFN2flox/floxMRP8cre mice (57), we found that MFN2 protein expression is only decreased by 50-60% in peripheral blood neutrophils. A cre expressing in an earlier stage of hematopoietic differentiation, such as Vav1-cre (80, 86), might increase the knockout efficiency but will lose the specificity to neutrophils.

An alternative to studying the roles of mitochondrial components in neutrophils is to use HoxB8-expressing neutrophil progenitors (87). HoxB8 expression blocks the terminal differentiation of progenitors into monocytes or granulocytes (88, 89). Gene editing can be done in HoxB8 neutrophil progenitors. HoxB8 neutrophil progenitors can differentiate into neutrophils in vitro (90–94) and in vivo (95, 96). These will provide a powerful tool to study the involvement of mitochondrial components in mouse neutrophils.

There are strategies to perform gene editing in human neutrophils and study the roles of mitochondrial components. One is using a highly effective di-peptide caspase inhibitor, Q-VD.OPh, to inhibit apoptosis in long-time in vitro culture of human neutrophils (97). However, whether it is possible to perform gene editing of human neutrophils in this system and whether this culture will affect some neutrophil functions is not clear. A better strategy is to use human-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), perform gene editing on them, and differentiate them into neutrophils (98–101). This may be the best strategy to study the roles of mitochondrial components in human neutrophils.

Besides nuclear genome-encoded genes of mitochondrial components, mitochondrial DNA also encodes genes that are associated with many diseases, such as Leigh syndrome (102–104), NARP (neuron, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa) syndrome (105), and Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (106, 107). Thus, mitochondrial gene editing is critical for studying the roles of mitochondria in human neutrophils. Several techniques to edit mitochondrial genes were highlighted in previous reviews (108, 109). One of the techniques used a modulated Cas9-CRISPR gene-editing technique by appending a gene targeting guide RNA to an RNA transport-derived stem loop element (RP-loop) and expressing the Cas9 enzyme with a preceding mitochondrial localization sequence (110). Another technique is using an interbacterial toxin, DddA, which catalyzes cytidine deamination within double-stranded DNA. Fusions of the split-DddA halves, transcription activator-like effector array proteins, and a uracil glycosylase inhibitor resulted in RNA-free DddA-derived cytosine base editors (DdCBEs) that catalyze C·G-to-T·A conversions in human mtDNA with high targeting specificity and product purity (111). Later, another technique using transcription-activator-like effector (TALE)-linked deaminases (TALEDs) can catalyze A·T-to-G·C conversions in human mtDNA (112). These mitochondrial gene-editing techniques will bring new insights into studying the roles of mitochondria in neutrophil functions.

Author contributions

ZC drafted the manuscript; ZC prepared the figure and tables; HS, LH, YC, MZ, and ZF edited and revised the manuscript; ZF approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health, USA (NIH, R01HL145454), and a startup fund from UConn Health.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Christopher “Kit” Bonin and Dr. Geneva Hargis from UConn Health School of Medicine for their help scientific writing and editing of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Kolaczkowska E, Kubes P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol (2013) 13(3):159–75.

2. Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: The leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol (2007) 7(9):678–89.

3. Ley K, Hoffman HM, Kubes P, Cassatella MA, Zychlinsky A, Hedrick CC, et al. Neutrophils: New insights and open questions. Sci Immunol (2018) 3(30):eaat4579.

4. Morikis VA, Simon SI. Neutrophil mechanosignaling promotes integrin engagement with endothelial cells and motility within inflamed vessels. Front Immunol (2018) 2774.

5. Boero E, Brinkman I, Juliet T, van Yperen E, van Strijp JAG, Rooijakkers SHM, et al. Use of flow cytometry to evaluate phagocytosis of staphylococcus aureus by human neutrophils. Front Immunol (2021) 12:635825. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.635825

6. Gierlikowska B, Stachura A, Gierlikowski W, Demkow U. Phagocytosis, degranulation and extracellular traps release by neutrophils–the current knowledge, pharmacological modulation and future prospects. Front Pharmacol (2021) 12:666732. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.666732

7. Payne JA, Tailhades J, Ellett F, Kostoulias X, Fulcher AJ, Fu T, et al. Antibiotic-chemoattractants enhance neutrophil clearance of staphylococcus aureus. Nat Commun (2021) 12(1):1–15.

8. Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science (2004) 303(5663):1532–5.

9. Monteith AJ, Miller JM, Maxwell CN, Chazin WJ, Skaar EP. Neutrophil extracellular traps enhance macrophage killing of bacterial pathogens. Sci Adv (2021) 7(37):eabj2101.

10. Eichelberger KR, Goldman WE. Manipulating neutrophil degranulation as a bacterial virulence strategy. PLoS Pathog (2020) 16(12):e1009054. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009054

11. Beavers WN, Skaar EP. Neutrophil-generated oxidative stress and protein damage in staphylococcus aureus. Pathog Dis (2016) 74(6):ftw060. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftw060

12. Nauseef WM. How human neutrophils kill and degrade microbes: An integrated view. Immunol Rev (2007) 219(1):88–102.

13. Bock FJ, Tait SW. Mitochondria as multifaceted regulators of cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2020) 21(2):85–100.

14. Fossati G, Moulding DA, Spiller DG, Moots RJ, White MR, Edwards SW. The mitochondrial network of human neutrophils: Role in chemotaxis, phagocytosis, respiratory burst activation, and commitment to apoptosis. J Immunol (2003) 170(4):1964–72.

15. Bao Y, Ledderose C, Seier T, Graf AF, Brix B, Chong E, et al. Mitochondria regulate neutrophil activation by generating ATP for autocrine purinergic signaling. J Biol Chem (2014) 289(39):26794–803.

16. Vorobjeva N, Prikhodko A, Galkin I, Pletjushkina O, Zinovkin R, Sud’ina G, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species are involved in chemoattractant-induced oxidative burst and degranulation of human neutrophils in vitro. Eur J Cell Biol (2017) 96(3):254–65.

17. Dunham-Snary KJ, Surewaard BG, Mewburn JD, Bentley RE, Martin AY, Jones O, et al. Mitochondria in human neutrophils mediate killing of staphylococcus aureus. Redox Biol (2022) 49:102225.

18. Rice CM, Davies LC, Subleski JJ, Maio N, Gonzalez-Cotto M, Andrews C, et al. Tumour-elicited neutrophils engage mitochondrial metabolism to circumvent nutrient limitations and maintain immune suppression. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):1–13.

19. Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, Hurwitz R, Schulze I, Wahn V, et al. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol (2007) 176(2):231–41.

20. Castanheira FV, Kubes P. Neutrophils and NETs in modulating acute and chronic inflammation. Blood J Am Soc Hematol (2019) 133(20):2178–85.

21. Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat Rev Immunol (2018) 18(2):134–47.

22. Hosseinzadeh A, Thompson PR, Segal BH, Urban CF. Nicotine induces neutrophil extracellular traps. J Leukoc Biol (2016) 100(5):1105–12.

23. Hakkim A, Fuchs TA, Martinez NE, Hess S, Prinz H, Zychlinsky A, et al. Activation of the raf-MEK-ERK pathway is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Nat Chem Biol (2011) 7(2):75–7.

24. Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol (2010) 191(3):677–91.

25. Azevedo EP, Rochael NC, Guimarães-Costa AB, de Souza-Vieira TS, Ganilho J, Saraiva EM, et al. A metabolic shift toward pentose phosphate pathway is necessary for amyloid fibril-and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-induced neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation. J Biol Chem (2015) 290(36):22174–83.

26. Rodríguez-Espinosa O, Rojas-Espinosa O, Moreno-Altamirano MMB, López-Villegas EO, Sánchez-García FJ. Metabolic requirements for neutrophil extracellular traps formation. Immunology (2015) 145(2):213–24.

27. Yousefi S, Mihalache C, Kozlowski E, Schmid I, Simon H-U. Viable neutrophils release mitochondrial DNA to form neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Death Differ (2009) 16(11):1438–44.

28. Amini P, Stojkov D, Felser A, Jackson CB, Courage C, Schaller A, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap formation requires OPA1-dependent glycolytic ATP production. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):1–16.

29. Douda DN, Khan MA, Grasemann H, Palaniyar N. SK3 channel and mitochondrial ROS mediate NADPH oxidase-independent NETosis induced by calcium influx. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2015) 112(9):2817–22.

30. Takishita Y, Yasuda H, Shimizu M, Matsuo A, Morita A, Tsutsumi T, et al. Formation of neutrophil extracellular traps in mitochondrial DNA-deficient cells. J Clin Biochem Nutr (2019) 66(1):15–23.

31. Naffah de Souza C, Breda LCD, Khan MA, Almeida SR, Câmara NOS, Sweezey N, et al. Alkaline pH promotes NADPH oxidase-independent neutrophil extracellular trap formation: A matter of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation and citrullination and cleavage of histone. Front Immunol (2018) 8:1849. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01849

32. Reithofer M, Karacs J, Strobl J, Kitzmüller C, Polak D, Seif K, et al. Alum triggers infiltration of human neutrophils ex vivo and causes lysosomal destabilization and mitochondrial membrane potential-dependent NET-formation. FASEB J (2020) 34(10):14024–41.

33. Monteith AJ, Miller JM, Beavers WN, Maloney KN, Seifert EL, Hajnoczky G, et al. Mitochondrial calcium uniporter affects neutrophil bactericidal activity during staphylococcus aureus infection. Infect Immun (2021) 90(2):e0055121.

34. Lewis HD, Liddle J, Coote JE, Atkinson SJ, Barker MD, Bax BD, et al. Inhibition of PAD4 activity is sufficient to disrupt mouse and human NET formation. Nat Chem Biol (2015) 11(3):189–91.

35. Li P, Li M, Lindberg MR, Kennett MJ, Xiong N, Wang Y. PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med (2010) 207(9):1853–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100239

36. Lood C, Blanco LP, Purmalek MM, Carmona-Rivera C, De Ravin SS, Smith CK, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps enriched in oxidized mitochondrial DNA are interferogenic and contribute to lupus-like disease. Nat Med (2016) 22(2):146–53.

37. Liao T-L, Chen Y-M, Tang K-T, Chen P-K, Liu H-J, Chen D-Y. MicroRNA-223 inhibits neutrophil extracellular traps formation through regulating calcium influx and small extracellular vesicles transmission. Sci Rep (2021) 11(1):1–17.

38. Maianski N, Geissler J, Srinivasula S, Alnemri E, Roos D, Kuijpers T. Functional characterization of mitochondria in neutrophils: A role restricted to apoptosis. Cell Death Differ (2004) 11(2):143–53.

39. Bao Y, Ledderose C, Graf AF, Brix B, Birsak T, Lee A, et al. MTOR and differential activation of mitochondria orchestrate neutrophil chemotaxis. J Cell Biol (2015) 210(7):1153–64.

40. Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, et al. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science (2006) 314(5806):1792–5.

41. Kondo Y, Ledderose C, Slubowski CJ, Fakhari M, Sumi Y, Sueyoshi K, et al. Frontline science: Escherichia coli use LPS as decoy to impair neutrophil chemotaxis and defeat antimicrobial host defense. J Leukoc Biol (2019) 106(6):1211–9. doi: 10.1002/JLB.4HI0319-109R

42. Tavares-Murta BM, Zaparoli M, Ferreira RB, Silva-Vergara ML, Oliveira CH, Murta EFC, et al. Failure of neutrophil chemotactic function in septic patients*. Crit Care Med (2002) 30(5):1056–61.

43. Zhou W, Cao L, Jeffries J, Zhu X, Staiger CJ, Deng Q. Neutrophil-specific knockout demonstrates a role for mitochondria in regulating neutrophil motility in zebrafish. Dis Models Mech (2018) 11(3):dmm033027.

44. Sakai J, Li J, Subramanian KK, Mondal S, Bajrami B, Hattori H, et al. Reactive oxygen species-induced actin glutathionylation controls actin dynamics in neutrophils. Immunity (2012) 37(6):1037–49.

45. Zmijewski JW, Lorne E, Zhao X, Tsuruta Y, Sha Y, Liu G, et al. Mitochondrial respiratory complex I regulates neutrophil activation and severity of lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2008) 178(2):168–79.

46. Mimaki M, Wang X, McKenzie M, Thorburn DR, Ryan MT. Understanding mitochondrial complex I assembly in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta (2012) 1817:851–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.08.010

47. Smith PM, Fox JL, Winge DR. Biogenesis of the cytochrome bc(1) complex and role of assembly factors. Biochim Biophys Acta (2012) 1817:276–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.11.009

48. El Chemaly A, Okochi Y, Sasaki M, Arnaudeau S, Okamura Y, Demaurex N. VSOP/Hv1 proton channels sustain calcium entry, neutrophil migration, and superoxide production by limiting cell depolarization and acidification. J Exp Med (2010) 207(1):129–39.

49. Okochi Y, Umemoto E, Okamura Y. Hv1/VSOP regulates neutrophil directional migration and ERK activity by tuning ROS production. J Leukoc Biol (2020) 107(5):819–31.

50. Riganti C, Gazzano E, Polimeni M, Costamagna C, Bosia A, Ghigo D. Diphenyleneiodonium inhibits the cell redox metabolism and induces oxidative stress. J Biol Chem (2004) 279(46):47726–31.

51. Paupe V, Prudent J. New insights into the role of mitochondrial calcium homeostasis in cell migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2018) 500(1):75–86.

52. Zheng X, Chen M, Meng X, Chu X, Cai C, Zou F. Phosphorylation of dynamin-related protein 1 at Ser616 regulates mitochondrial fission and is involved in mitochondrial calcium uniporter-mediated neutrophil polarization and chemotaxis. Mol Immunol (2017) 87:23–32.

53. Cho B, Choi SY, Cho HM, Kim HJ, Sun W. Physiological and pathological significance of dynamin-related protein 1 (drp1)-dependent mitochondrial fission in the nervous system. Exp Neurobiol (2013) 22(3):149.

54. Mazaki Y, Takada S, Nio-Kobayashi J, Maekawa S, Higashi T, Onodera Y, et al. Mitofusin 2 is involved in chemotaxis of neutrophil-like differentiated HL-60 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2019) 513(3):708–13.

55. Zhou W, Hsu AY, Wang Y, Syahirah R, Wang T, Jeffries J, et al. Mitofusin 2 regulates neutrophil adhesive migration and the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci (2020) 133(17):jcs248880.

56. Kornmann B, Currie E, Collins SR, Schuldiner M, Nunnari J, Weissman JS, et al. An ER-mitochondria tethering complex revealed by a synthetic biology screen. Science (2009) 325(5939):477–81.

57. Liu W, Hsu AY, Wang Y, Lin T, Sun H, Pachter JS, et al. Mitofusin-2 regulates leukocyte adhesion and β2 integrin activation. J Leukoc Biol (2021) 111(4):771–91.

58. Fan Z, McArdle S, Marki A, Mikulski Z, Gutierrez E, Engelhardt B, et al. Neutrophil recruitment limited by high-affinity bent β2 integrin binding ligand in cis. Nat Commun (2016) 7(1):1–14.

59. Fan Z, Kiosses WB, Sun H, Orecchioni M, Ghosheh Y, Zajonc DM, et al. High-affinity bent β2-integrin molecules in arresting neutrophils face each other through binding to ICAMs in cis. Cell Rep (2019) 26(1):119–30.

60. Sun H, Hu L, Fan Z. β2 integrin activation and signal transduction in leukocyte recruitment. Am J Physiol-Cell. Physiol (2021) 321(2):C308–16.

61. Sun H, Zhi K, Hu L, Fan Z. The activation and regulation of β2 integrins in phagocytes. Front Immunol (2021) 12:978.

62. Luo B-H, Carman CV, Springer TA. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu Rev Immunol (2007) 25:619–47.

63. Jiao H, Jiang D, Hu X, Du W, Ji L, Yang Y, et al. Mitocytosis, a migrasome-mediated mitochondrial quality-control process. Cell (2021) 184(11):2896–910.

64. Riffelmacher T, Clarke A, Richter FC, Stranks A, Pandey S, Danielli S, et al. Autophagy-dependent generation of free fatty acids is critical for normal neutrophil differentiation. Immunity (2017) 47(3):466–80.

65. Tanimura A, Miyoshi K, Horiguchi T, Hagita H, Fujisawa K, Noma T. Mitochondrial activity and unfolded protein response are required for neutrophil differentiation. Cell Physiol Biochem (2018) 47(5):1936–50.

66. Luchsinger LL, de Almeida MJ, Corrigan DJ, Mumau M, Snoeck H-W. Mitofusin 2 maintains haematopoietic stem cells with extensive lymphoid potential. Nature (2016) 529(7587):528–31.

67. Willson JA, Arienti S, Sadiku P, Reyes L, Coelho P, Morrison T, et al. Neutrophil HIF-1α stabilization is augmented by mitochondrial ROS produced via the glycerol 3-phosphate shuttle. Blood J Am Soc Hematol (2022) 139(2):281–6.

68. Wang Y, Wang W, Wang N, Tall AR, Tabas I. Mitochondrial oxidative stress promotes atherosclerosis and neutrophil extracellular traps in aged mice. Arteriosclerosis. Thromb. Vasc Biol (2017) 37(8):e99–e107.

69. Contis A, Mitrovic S, Lavie J, Douchet I, Lazaro E, Truchetet M-E, et al. Neutrophil-derived mitochondrial DNA promotes receptor activator of nuclear factor κB and its ligand signalling in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (2017) 56(7):1200–5.

70. Yang C, Wang Z, Li L, Zhang Z, Jin X, Wu P, et al. Aged neutrophils form mitochondria-dependent vital NETs to promote breast cancer lung metastasis. J Immunotherapy. Cancer (2021) 9(10):e002875.

72. Megens RT, Vijayan S, Lievens D, Doering Y, van Zandvoort MA, Grommes J, et al. Presence of luminal neutrophil extracellular traps in atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemostasis (2012) 107(03):597–8.

73. Yeo L, Toellner K-M, Salmon M, Filer A, Buckley CD, Raza K, et al. Cytokine mRNA profiling identifies b cells as a major source of RANKL in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheumatic. Dis (2011) 70(11):2022–8.

74. Chakravarti A, Raquil M-A, Tessier P, Poubelle PE. Surface RANKL of toll-like receptor 4–stimulated human neutrophils activates osteoclastic bone resorption. Blood J Am Soc Hematol (2009) 114(8):1633–44.

75. Hu Q, Shi H, Zeng T, Liu H, Su Y, Cheng X, et al. Increased neutrophil extracellular traps activate NLRP3 and inflammatory macrophages in adult-onset Still's disease. Arthritis Res Ther (2019) 21(1):276–86. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1800-z

76. Kalyan S, Kabelitz D. When neutrophils meet T cells: Beginnings of a tumultuous relationship with underappreciated potential. Eur J Immunol (2014) 44(3):627–33.

77. Leliefeld PH, Koenderman L, Pillay J. How neutrophils shape adaptive immune responses. Front Immunol (2015) 6:471.

78. Pillay J, Tak T, Kamp VM, Koenderman L. Immune suppression by neutrophils and granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells: Similarities and differences. Cell Mol Life Sci (2013) 70(20):3813–27.

79. Spiegel A, Brooks MW, Houshyar S, Reinhardt F, Ardolino M, Fessler E, et al. Neutrophils suppress intraluminal NK cell–mediated tumor cell clearance and enhance extravasation of disseminated carcinoma CellsNeutrophil-mediated tumor cell survival and extravasation. Cancer Discovery (2016) 6(6):630–49.

80. Abram CL, Roberge GL, Hu Y, Lowell CA. Comparative analysis of the efficiency and specificity of myeloid-cre deleting strains using ROSA-EYFP reporter mice. J Immunol Methods (2014) 408:89–100.

81. Passegué E, Wagner EF, Weissman IL. JunB deficiency leads to a myeloproliferative disorder arising from hematopoietic stem cells. Cell (2004) 119(3):431–43.

82. Ancey P-B, Contat C, Boivin G, Sabatino S, Pascual J, Zangger N, et al. GLUT1 expression in tumor-associated neutrophils promotes lung cancer growth and resistance to radiotherapy. Cancer Res (2021) 81(9):2345–57.

83. Hasenberg A, Hasenberg M, Männ L, Neumann F, Borkenstein L, Stecher M, et al. Catchup: A mouse model for imaging-based tracking and modulation of neutrophil granulocytes. Nat Methods (2015) 12(5):445–52.

84. Clausen B, Burkhardt C, Reith W, Renkawitz R, Förster I. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res (1999) 8(4):265–77.

85. Shi J, Hua L, Harmer D, Li P, Ren G. Cre driver mice targeting macrophages. In: Methods Mol Biol. Springer (2018). 1784:263–75.

86. de Boer J, Williams A, Skavdis G, Harker N, Coles M, Tolaini M, et al. Transgenic mice with hematopoietic and lymphoid specific expression of cre. Eur J Immunol (2003) 33(2):314–25.

87. Wang GG, Calvo KR, Pasillas MP, Sykes DB, Häcker H, Kamps MP. Quantitative production of macrophages or neutrophils ex vivo using conditional Hoxb8. Nat Methods (2006) 3(4):287–93.

88. Knoepfler PS, Sykes DB, Pasillas M, Kamps MP. HoxB8 requires its pbx-interaction motif to block differentiation of primary myeloid progenitors and of most cell line models of myeloid differentiation. Oncogene (2001) 20(39):5440–8.

89. Krishnaraju K, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. Lineage-specific regulation of hematopoiesis by HOX-B8 (HOX-2.4): Inhibition of granulocytic differentiation and potentiation of monocytic differentiation. Blood J Am Soc Hematol (1997) 90(5):1840–9.

90. Chu JY, McCormick B, Mazelyte G, Michael M, Vermeren S. HoxB8 neutrophils replicate fcγ receptor and integrin-induced neutrophil signaling and functions. J Leukoc. Biol (2019) 105(1):93–100.

91. McDonald JU, Cortini A, Rosas M, Fossati-Jimack L, Ling GS, Lewis KJ, et al. In vivo functional analysis and genetic modification of in vitro-derived mouse neutrophils. FASEB J (2011) 25(6):1972–82.

92. Saul S, Castelbou C, Fickentscher C, Demaurex N. Signaling and functional competency of neutrophils derived from bone-marrow cells expressing the ER-HOXB8 oncoprotein. J Leukoc Biol (2019) 106(5):1101–15.

93. Weiss E, Hanzelmann D, Fehlhaber B, Klos A, von Loewenich FD, Liese J, et al. Formyl-peptide receptor 2 governs leukocyte influx in local staphylococcus aureus infections. FASEB J (2018) 32(1):26–36.

94. Zehrer A, Pick R, Salvermoser M, Boda A, Miller M, Stark K, et al. A fundamental role of Myh9 for neutrophil migration in innate immunity. J Immunol (2018) 201(6):1748–64.

95. Cohen JT, Danise M, Hinman KD, Neumann BM, Johnson R, Wilson ZS, et al. Engraftment, fate, and function of HoxB8-conditional neutrophil progenitors in the unconditioned murine host. Front Cell Dev Biol (2022) 41.

96. Orosz A, Walzog B, Mócsai A. In vivo functions of mouse neutrophils derived from hoxb8-transduced conditionally immortalized myeloid progenitors. J Immunol (2021) 206(2):432–45.

97. Wardle DJ, Burgon J, Sabroe I, Bingle CD, Whyte MK, Renshaw SA. Effective caspase inhibition blocks neutrophil apoptosis and reveals mcl-1 as both a regulator and a target of neutrophil caspase activation. PLoS One (2011) 6(1):e15768.

98. Brok-Volchanskaya VS, Bennin DA, Suknuntha K, Klemm LC, Huttenlocher A, Slukvin I. Effective and rapid generation of functional neutrophils from induced pluripotent stem cells using ETV2-modified mRNA. Stem Cell Rep (2019) 13(6):1099–110.

99. Majumder A, Suknuntha K, Bennin D, Klemm L, Brok-Volchanskaya VS, Huttenlocher A, et al. Generation of human neutrophils from induced pluripotent stem cells in chemically defined conditions using ETV2 modified mRNA. STAR. Protoc (2020) 1(2):100075.

100. Trump LR, Nayak RC, Singh AK, Emberesh S, Wellendorf AM, Lutzko CM, et al. Neutrophils derived from genetically modified human induced pluripotent stem cells circulate and phagocytose bacteria in vivo. Stem Cells Trans Med (2019) 8(6):557–67.

101. Tsui M, Min W, Ng S, Dobbs K, Notarangelo LD, Dror Y, et al. The use of induced pluripotent stem cells to study the effects of adenosine deaminase deficiency on human neutrophil development. Front Immunol (2021) 12.

102. Pelnena D, Burnyte B, Jankevics E, Lace B, Dagyte E, Grigalioniene K, et al. Complete mtDNA sequencing reveals mutations m. 9185T> c and m. 13513G> a in three patients with Leigh syndrome. Mitochondrial. DNA Part A (2018) 29(7):1115–20.

103. Sofou K, de Coo IF, Ostergaard E, Isohanni P, Naess K, De Meirleir L, et al. Phenotype-genotype correlations in Leigh syndrome: New insights from a multicentre study of 96 patients. J Med Genet (2018) 55(1):21–7.

104. Wei Y, Cui L, Peng B. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in late-onset Leigh syndrome. J Neurol (2018) 265(10):2388–95.

105. Mordel P, Schaeffer S, Dupas Q, Laville M-A, Gérard M, Chapon F, et al. A 2 bp deletion in the mitochondrial ATP 6 gene responsible for the NARP (neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa) syndrome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2017) 494(1–2):133–7.

106. Carelli V, Carbonelli M, Irenaeus F, Kawasaki A, Klopstock T, Lagrèze WA, et al. International consensus statement on the clinical and therapeutic management of leber hereditary optic neuropathy. J Neuro-Ophthalmology (2017) 37(4):371–81.

107. Wallace DC, Singh G, Lott MT, Hodge JA, Schurr TG, Lezza AM, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Science (1988) 242(4884):1427–30.

108. Yang X, Jiang J, Li Z, Liang J, Xiang Y. Strategies for mitochondrial gene editing. Comput Struct Biotechnol J (2021) 19:3319–29.

109. Yin T, Luo J, Huang D, Li H. Current progress of mitochondrial genome editing by CRISPR. Front Physiol (2022) 884.

110. Hussain S-RA, Yalvac ME, Khoo B, Eckardt S, McLaughlin KJ. Adapting CRISPR/Cas9 system for targeting mitochondrial genome. Front Genet (2021) 12:627050.

111. Mok BY, de Moraes MH, Zeng J, Bosch DE, Kotrys AV, Raguram A, et al. A bacterial cytidine deaminase toxin enables CRISPR-free mitochondrial base editing. Nature (2020) 583(7817):631–7.

Keywords: neutrophils, mitochondria, respiratory burst, NETosis, migration, adhesion

Citation: Cao Z, Zhao M, Sun H, Hu L, Chen Y and Fan Z (2022) Roles of mitochondria in neutrophils. Front. Immunol. 13:934444. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.934444

Received: 02 May 2022; Accepted: 19 July 2022;

Published: 19 August 2022.

Edited by:

Pedro Elias Marques, KU Leuven, BelgiumReviewed by:

Siva Sankara Vara Prasad Sakamuri, Tulane University, United StatesMatheus Mattos, KU Leuven, Belgium

Copyright © 2022 Cao, Zhao, Sun, Hu, Chen and Fan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhichao Fan, emZhbkB1Y2hjLmVkdQ==

Ziming Cao

Ziming Cao Meng Zhao

Meng Zhao Hao Sun

Hao Sun Liang Hu

Liang Hu Yunfeng Chen

Yunfeng Chen Zhichao Fan

Zhichao Fan