95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol. , 02 June 2022

Sec. Microbial Immunology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.890258

This article is part of the Research Topic Immune Interactions with Pathogenic and Commensal Fungi View all 17 articles

Cryptococcus neoformans is a major etiological agent of fungal meningoencephalitis. The outcome of cryptococcosis depends on the complex interactions between the pathogenic fungus and host immunity. The understanding of how C. neoformans manipulates the host immune response through its pathogenic factors remains incomplete. In this study, we defined the roles of a previously uncharacterized protein, Csn1201, in cryptococcal fitness and host immunity. Use of both inhalational and intravenous mouse models demonstrated that the CSN1201 deletion significantly blocked the pulmonary infection and extrapulmonary dissemination of C. neoformans. The in vivo hypovirulent phenotype of the csn1201Δ mutant was attributed to a combination of multiple factors, including preferential dendritic cell accumulation, enhanced Th1 and Th17 immune responses, decreased intracellular survival inside macrophages, and attenuated blood–brain barrier transcytosis rather than exclusively to pathogenic fitness. The csn1201Δ mutant exhibited decreased tolerance to various stressors in vitro, along with reduced capsule production and enhanced cell wall thickness under host-relevant conditions, indicating that the CSN1201 deletion might promote the exposure of cell wall components and thus induce a protective immune response. Taken together, our results strongly support the importance of cryptococcal Csn1201 in pulmonary immune responses and disseminated infection.

Cryptococcus neoformans is a major fungal pathogen that causes life-threatening meningoencephalitis in both immunocompromised and apparently immunocompetent hosts (1). The increasing prevalence of immunocompromised individuals, such as those with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and organ transplantation treated with immunosuppressive compounds to prevent organ rejection, has resulted in a significant rise in the morbidity and mortality of cryptococcosis. Globally, Cryptococcus causes approximately 278,000 infections and 181,000 deaths each year (2). C. neoformans is also an excellent fungal model for studying pathogen–host interactions (3).

C. neoformans is widely distributed in natural environments that include soil and bird droppings (4). The desiccated yeast cells or basidiospores mainly invade the respiratory tract via inhalation, and then cause asymptomatic pneumonia. The pathogen is often cleared by host immunity or becomes latent (5). When host immunity is compromised or suppressed, the resting cryptococcal cells reactivate and cause systemic infection, especially in the central nervous system. Infection results from complex interactions between the pathogenic fungus and host immunity. C. neoformans can adapt to the hostile environment in vivo (such as nutrient limitation, oxidative stress, etc.) through the expression of multiple virulence factors that include capsule and melanin (6). On the other hand, the direct damage or interference caused by C. neoformans does not allow the host to organise an effective immune response to contain or kill the pathogen, ultimately resulting in fungal dissemination (7). Several studies have demonstrated that C. neoformans induces a non-protective Th2 immune response or inhibits an excessive inflammatory response through the expression of classical or non-classical virulence factors (8–13). Identification of critical pathogenic factors that control the activation of protective immune responses will be beneficial for developing new immunotherapy strategies against cryptococcosis.

Previous studies systematically screened a substantial number of uncharacterised pathogenic factors (including Csn1201) from the gene-deletion library of C. neoformans strain KN99α (14, 15). Their functions and mechanisms in composite cryptococcal virulence have remained unclear.

Based on the background of the clinical hypervirulent strain, H99, we further characterised the pleiotropic roles of cryptococcal Csn1201 in fungal fitness and host immunity in the present study. Deletion of Csn1201 considerably blocked the pulmonary infection and extrapulmonary dissemination of C. neoformans. The in vivo hypovirulent phenotype of the csn1201Δ mutant could likely be attributed to a combination of multiple factors, such as enhanced Th1 and Th17 immune responses, attenuated blood–brain barrier (BBB) transcytosis, and reduced fungal fitness in the host environment. These results enhance our understanding of host–pathogen interactions and provide opportunities to explore new intervention strategies against cryptococcosis.

C. neoformans strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Strains were cultured at 30°C on YPD agar medium (1% yeast extract, 2% bacto-peptone, and 2% glucose) and selective media contained nourseothricin (100 mg/L) and/or neomycin (G418 200 mg/L). Stress media were prepared by adding different stress inducing agents to YNB agar medium (0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 2% glucose) or YPD agar medium before autoclaving. Capsule- and melanin-inducing media were prepared as previously reported (16). DMEM with 10% FBS (Transgen Biotech, Beijing, China) was used for cell culture in the murine-derived J774 macrophage killing assay.

The CSN1201 gene sequence (CNAG_01697) was obtained from the C. neoformans var. grubii serotype A genome database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?id=235443). For gene disruption, overlap PCR was used to generate the knock-out cassette of CSN1201, including the flanking fragments and NAT resistance gene (17). The purified PCR products were precipitated onto gold microparticles and introduced into H99 cells by biolistic transformation (16). Stable transformants were screened using selective medium containing nourseothricin and confirmed by diagnostic PCR, DNA sequencing, and Southern blotting. To complement the csn1201Δ mutant, a genomic DNA fragment containing the ORF, promoter, and terminator region was amplified using primers ReCSN1201-F and ReCSN1201-R. This PCR fragment and the digested plasmid pJAF1 by Xba I were fused using the In-FusionH EcoDry Cloning System (Clontech; TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan). The reconstructed vector pCSN1201-NEO was linearised and reintroduced into csn1201Δ mutants via biolistic transformation. Positive colonies were selected on YPD agar containing G418. Reconstitution was confirmed by diagnostic PCR and Southern blotting. The primers used to construct the strains are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Southern blot analysis was performed to confirm the mutant and reconstituted strains as previously described (16). Genomic DNA (20 μg) from the strains was digested using specific restriction endonucleases and separated by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. The DNA fragments were transferred to positively charged nylon membranes (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The NEO or NAT probe was labelled with digoxigenin by the manufacturer (Roche Applied Science) and was detected on the membrane.

The in vitro stress assays were performed as previously described (17). Briefly, each strain was incubated to saturation at 30°C in YPD medium, washed, and diluted to 2.5×108 cells/mL in PBS. Four microlitre aliquots were spotted onto YNB or YPD agar medium containing different stress-inducing compounds. For the oxidative and nitric oxide (NO) stress test, 2 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was added to the YNB agar medium. For the osmotic stress and high salt sensitivity tests, 1.5 M sorbitol, 1.5 M NaCl, and 1.5 M KCl were incorporated in YPD agar medium. To examine cell wall integrity, the cells were spotted onto YPD agar medium containing 0.02% SDS and 0.5% Congo red. The spotted cells were incubated at 30°C for 3 days and photographed. For temperature stress, the YPD plates were incubated at 30°C, 37°C, and 39°C.

The yeast cells were incubated in DMEM at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 3 days in tissue culture flasks at a density of 5×106 to 107 cells/mL. The cells were washed with sterile PBS, and resuspended in PBS, 10 µL aliquots of the cell suspension were each mixed with a drop of India Ink and observed by microscopy. The relative ratio of the capsule was calculated as previously reported (16). For the melanisation test, cells were spotted onto caffeic acid agar and incubated for 3–7 days at 30°C. Melanin production was monitored and photographed.

The serum survival assay was performed as previously described, with modifications (18). Briefly, yeast strains were incubated overnight in YPD medium at 30°C until saturation. Cryptococcal cells were then diluted at 1:10 into mouse serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), RP1640 (Sigma-Aldrich), PBS, and YPD and incubated at 37°C for another 3 days. The strains were diluted at 1:10 (1:100 overall) in PBS and plated (1:10 and 1:100) onto YPD agar plates. The plates were photographed after 3 days of incubation at 30°C.

The impact of CSN1201 deletion on the morphology of C. neoformans was assessed by TEM. Cryptococcal cells of both the wild-type (WT) and csn1201Δ strain were cultured to the logarithmic phase in YPD (30°C) or DMEM (37°C, 5% CO2). The cells were harvested and fixed as previously described (19). Ultrathin sections (approximately 70 nm thick) were generated using the EM UC7 ultramicrotome (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), collected on copper grids, and stained with 2% uranyl acetate and Sato’s triple lead stain. All sections were imaged on a Talos L120C TEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 80 kV equipped with a 4k×4k Ceta CCD camera.

The assay was performed as previously described (20). Yeast strains were incubated overnight at 30°C. J774A.1 macrophages seeded at a density of 106 cells/well were activated with interferon-gamma (INF-γ) and lipopolysaccharide for 18 h. Prior to coincubation, the yeast cells were incubated with the monoclonal antibody mAb18B7 for 1 h. Activated macrophages were coincubated with 106 cryptococcal cells for 2 h to allow phagocytosis. Extracellular yeasts were removed, diluted, and cultured on YPD plates for 3 days. Macrophages were lysed using 0.05% SDS, and intracellular (attached and digested) yeasts were determined on YPD plates after 3 days of growth. Phagocytosis efficiency was calculated as (intracellular cells/[intracellular cells + extracellular cells] × 100%). A similar method was used to calculate cryptococcal survival rates inside macrophages after 48 h of coincubation. Each strain was tested in triplicate.

An in vitro blood–brain barrier (BBB) model was constructed for the cryptococcal transcytosis assay as previously described (21). Briefly, 105 mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells (bEND.3) were seeded into the Costar 3422 Transwell apparatus (Corning, New York, NY, USA) and grown until confluence. The integrity of the BBB model was evaluated by measuring transendothelial electrical resistance using a Millicell‐ERS apparatus (Millipore, Inc., Billerica, MA, USA). Then, 4 × 105 cells of C. neoformans were added to the top compartment of the insert and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for predetermined times. Cryptococci were collected from the bottom compartment (brain side) and plated onto YPD agar to determine their transmigration efficiency.

The yeast cells were inoculated in YPD, incubated overnight, washed, suspended and diluted to 5 × 106 cells/mL in PBS. Sixteen G. mellonella larvae weighing 200–400 mg were inoculated for each group. The larvae suspension was injected (10 µL containing 50,000 cells) through the last foreleg and placed in petri dishes (17). The dishes were placed in a box and kept in the dark at room temperature. Survival was monitored every day. The larvae were considered dead when they displayed no movement in response to touch.

Yeast strains were grown in YPD liquid medium at 30°C with shaking overnight. The cells were washed twice with PBS and resuspended at a final concentration of 2×106 cells/mL. Groups of 10 female Balb/C mice (Shanghai Lingchuang Biotech, Shanghai, China), were infected with 25 µL (50,000 cells) yeast cells of each strain by dropping the inoculum into the nares or injecting into the tail vein. Animals were sacrificed when a loss of 20% body weight was observed compared to peak body weight. Other signs of sickness were monitored, including lethargy, lack of activity, and absence of grooming. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital

Infected animals were sacrificed at designated time points and the endpoint of the experiment. Infected lungs and brains were isolated, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution, and sent to Servicebio (Shanghai, China) for processing. Tissue slides with Periodic Acid-Schiff staining were examined by microscopy. The infected lungs, spleens, and brains were obtained under aseptic conditions. The organs were weighed and macerated in 1 mL sterile PBS. Serial 10-fold dilutions of the samples were plated in duplicates 100-µL aliquots on YPD containing 100 µL/mL chloramphenicol. Colonies were counted following incubation at 30°C for 2 to 3 days. The animal protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Military Medical University.

Lung leukocytes were isolated from inhalational mouse models as previously described (22). After sacrificing the mice, lungs were removed, minced with scissors, transferred to gentleMACS C tubes containing 5 mL of proprietary catalysts [RPMI 1640, 5% FBS, penicillin, and streptomycin; 1 mg/mL collagenase A (Roche Diagnostics); and 30 μg/mL DNase I]. The tissue samples were further homogenized using the gentle MACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). This process was followed by erythrocyte lysis using NH4Cl buffer (0.829% NH4Cl, 0.1% KHCO3, and 0.0372% Na2EDTA, pH 7.4). Cells were dispersed using a syringe and filtered through a sterile 100 μm nylon screen. The filtrate was centrifuged for 30 min at 1,500 g in the presence of 20% Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich) to separate leukocytes from cell debris and epithelial cells. Leukocytes were counted in a hemocytometer using Trypan blue.

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described (23). Cells were stained with antibodies (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) specific to various leukocyte subpopulations according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Data were collected on a FACS LSR2 flow cytometer using FACSDiva software (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Mountain View, CA, USA) and analysed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA, USA). Leukocyte subpopulations were identified using the following markers: neutrophils (CD45+ Ly6G+ CD11b+), dendritic cells (DCs, CD45+ CD11c+ MHC II high), eosinophils (CD45+ CD11b+ Siglec F+), monocytes (CD45+ Ly6C+ CD11c−), CD4 T cells (CD45+ CD3+ CD4+), CD8 T cells (CD45+ CD3+ CD8+), and B cells (CD45+ CD19+).

Cytokine analysis of lung tissues was performed as previously described (23). Briefly, lung tissue was excised and homogenized in sterile PBS at 4°C. The concentrations of each cytokine in lung homogenates were tested using the respective ELISA kit (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Survival was analysed using a Kaplan–Meier survival curve and the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. Virulence data were analysed for statistical differences with the log-rank test. A two-tailed unpaired Student t test was used for all other tests for statistical difference between the two groups. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad-Prism 5.0 software program (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A search of the C. neoformans genome database indicated that CSN1201 (CNAG_01697) encodes a 472-amino acid protein containing a PCI domain (Proteasome, COP9, Initiation factor 3). Bioinformatics analysis unexpectedly revealed the putative Csn1201 orthologue only in Cryptococcus spp. and evolutionarily related basidiomycete (such as Kwoniella spp., Saitozyma spp., and Trichosporon spp.). The orthologue was not present in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and higher eukaryotic species (such as Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, and Homo sapiens). The findings suggest that Csn1201 might be evolutionarily specific to some fungal species, including C. neoformans.

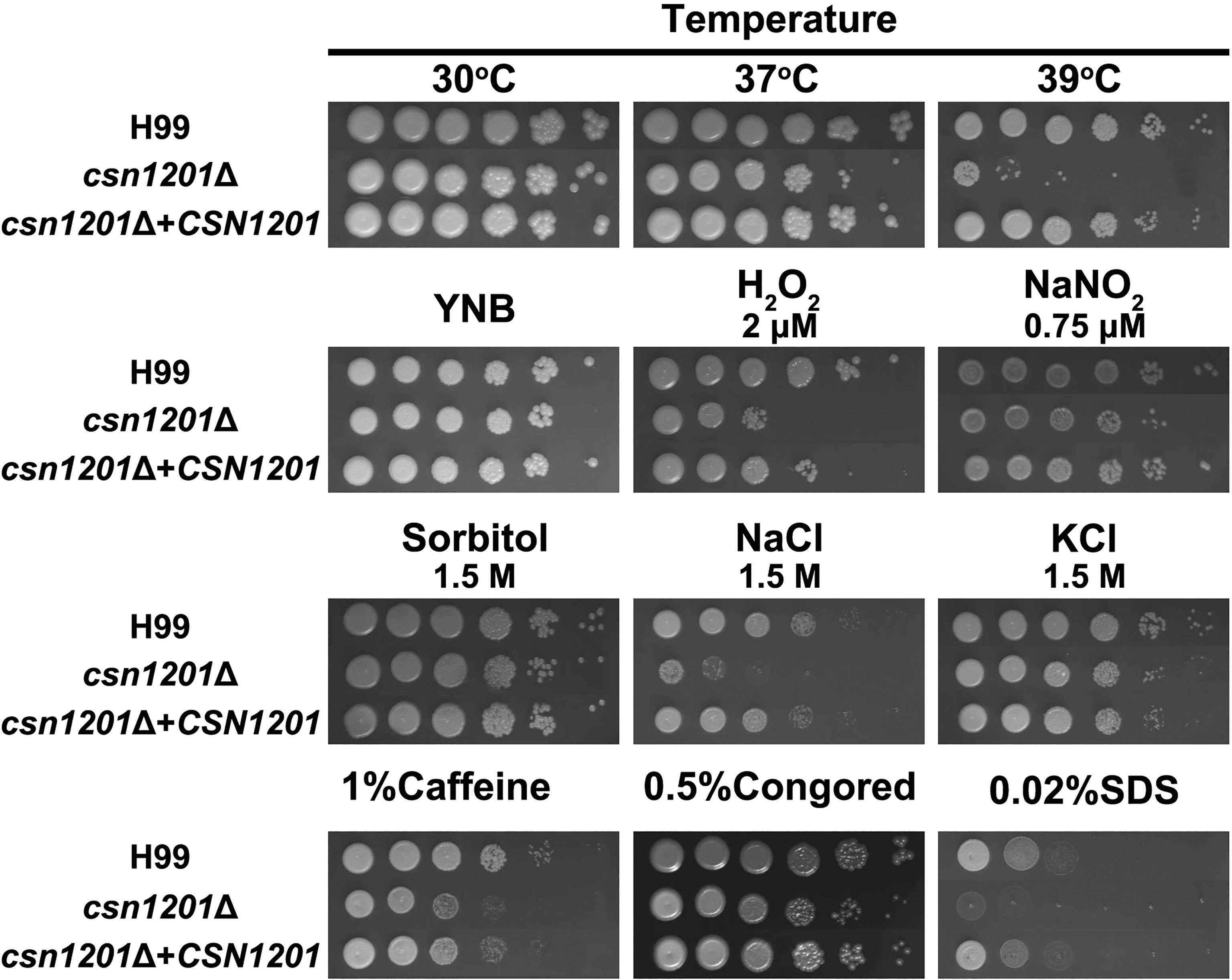

To investigate the roles of Csn1201 in the growth and pathogenesis of C. neoformans, we constructed the mutant strain csn1201Δ and its reconstituted strain csn1201Δ+CSN1201 via biolistic transformation. We first tested the sensitivity of each strain to a variety of in vitro stresses. As shown in Figure 1, the csn1201Δ mutant exhibited temperature sensitivity with a partial growth defect at 37°C and 39°C. Furthermore, csn1201Δ showed increased sensitivity to 2 µM H2O2 and 1.5 M NaCl, compared with the WT strain. These findings suggested that CSN1201 might be involved in regulating cryptococcal tolerance to oxidative stress and high salt environments. The csn1201Δ mutant also displayed mild defects in cryptococcal tolerance to cell wall or membrane-damaging agents. The csn1201Δ+CSN1201 reconstituted strain completely restored WT sensitivity in the in vitro stress assays.

Figure 1 Csn1201 is involved in various stress responses of C. neoformans. Strains were grown to saturation at 30°C in YPD medium, washed, serially diluted 10-fold (1–106 dilutions), and spotted (4 µL) onto YNB or YPD agar medium containing different stress-inducing agents. Spotted cells were incubated at 30°C for 3 days and then photographed.

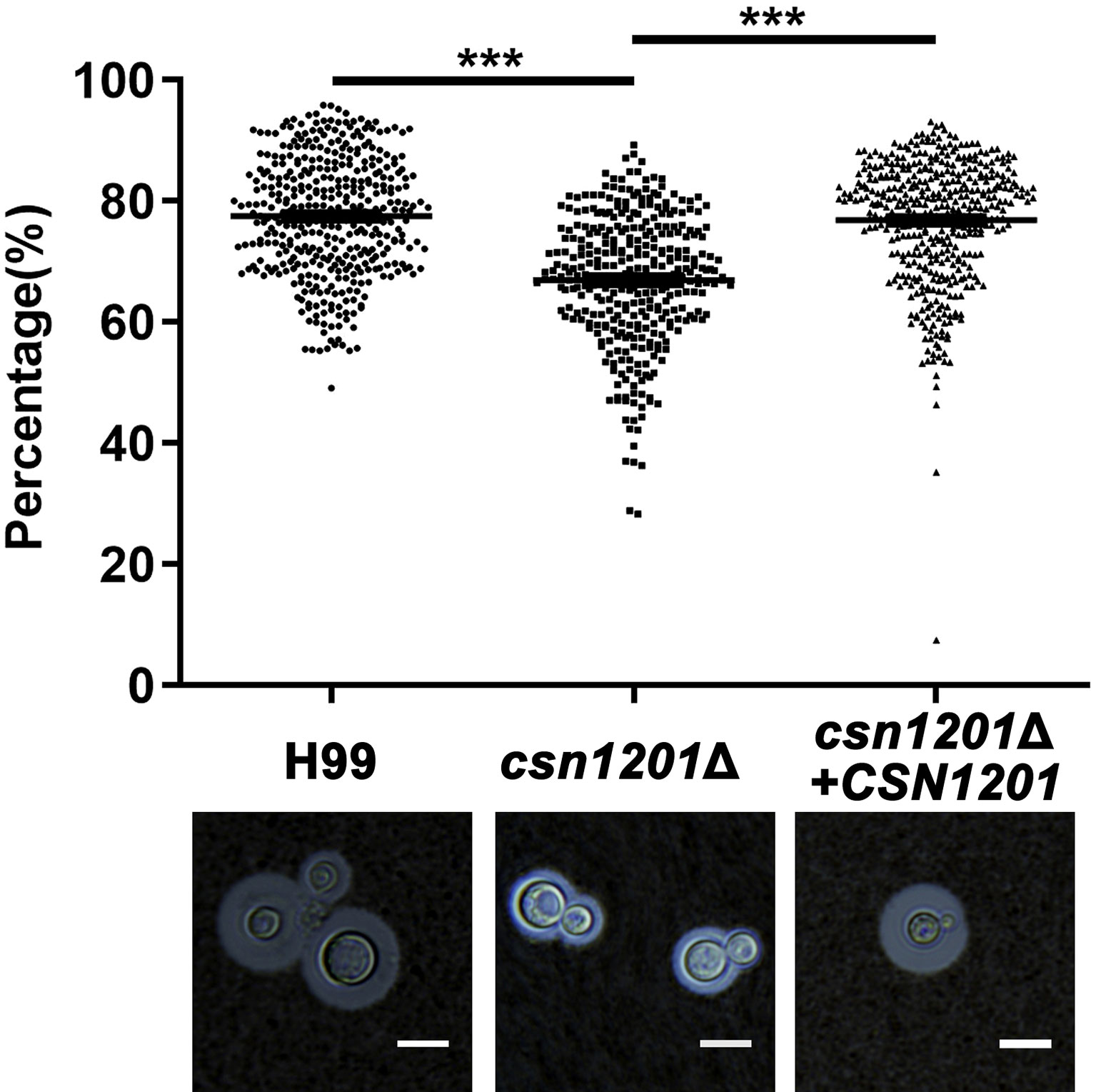

We next evaluated the effect of CSN1201 deletion in the production of different pathogenic factors of C. neoformans. When incubated in DMEM, the capsule thickness of the mutant was significantly decreased. The capsule thickness was restored to that of the WT in the reconstituted strain (Figure 2). When grown in melanin-inducing medium containing caffeic acid or niger seed, no noticeable melanin changes were observed in these strains (Figure S1). These results implicate Csn1201 in cryptococcal capsule production but suggest that Csn1201 is not required for melanin accumulation.

Figure 2 The CSN1201 deletion down-regulates capsule production. Each strain was cultured on DME medium for capsule production at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 3 days. The capsule was detected by staining with India ink and visualising at 100× magnification (scale bar = 10 µm). Total (cell and capsule) and cell-only diameters were measured using Photoshop Software for at least 300 cells for each strain. ***, P < 0.001.

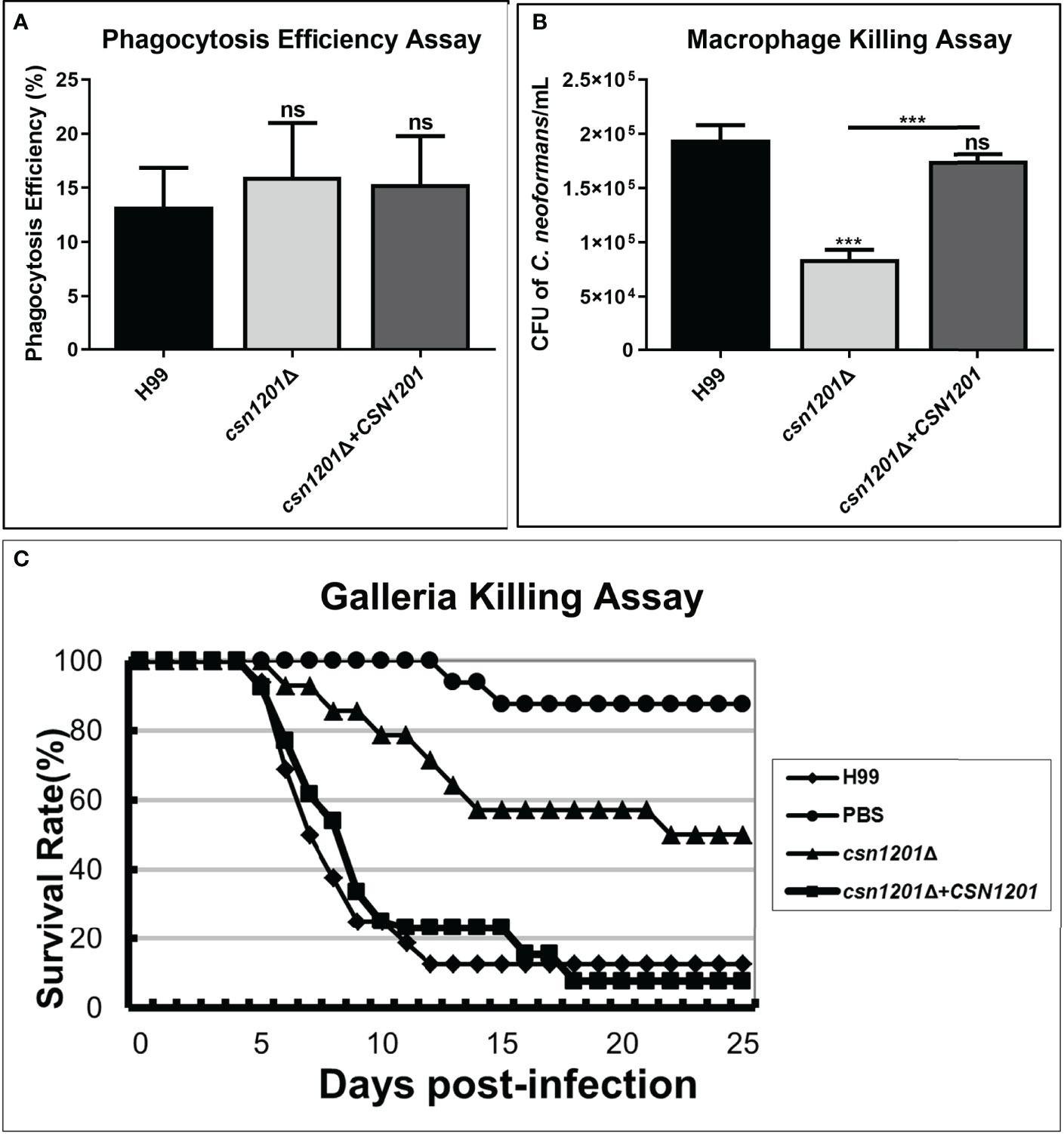

Macrophages, as the first line of host defence, are critical for cryptococcal latency and dissemination (24). Thus, we developed an ex vivo cell model to examine the intracellular parasitic capacity of the csn1201Δ mutant strain. There was no significant difference in the phagocytosis efficiency of the macrophages for these strains (Figure 3A), indicating that the CSN1201 deletion did not affect cryptococcal cell uptake into macrophages. After 48 h of co-culture with activated J774.1 macrophage-like cells, the mutant strain exhibited approximately a 50% reduction in intracellular survival (P<0.001) within macrophages compared with that of the WT or reconstituted strain (Figure 3B).

Figure 3 Csn1201 is required for cryptococcal survival in macrophages and in Galleria mellonella. Macrophage phagocytosis (A) and killing (B) assays. Activated macrophages were coincubated with 106 cryptococcal cells for 2 h to allow phagocytosis. Extracellular yeasts were removed, diluted, and cultured on YPD plates for 3 days. Macrophages were lysed with 0.05% SDS and intracellular (attached and digested) yeasts were determined on YPD plates after 3 days of growth. Phagocytosis efficiency was calculated using the formula (intracellular cells/[intracellular cells + extracellular cells] × 100%). A similar method was used to calculate cryptococcal survival inside the macrophage after 24 h of coincubation. Each strain was tested in triplicate. ***, P < 0.001; ns, no significant difference. (C) In vivo virulence assay in the G. mellonella model.

To further exclude the potential effect of high-temperature sensitivity on cryptococcal virulence, we also constructed the G. mellonella non-vertebrate infection model at 25°C. In the G. mellonellar/C. neoformans system, the csn1201Δ mutant (LT50 = 22 days) exhibited significantly attenuated virulence compared with the WT (LT50 = 7 days) or reconstituted (LT50 = 9 days) strains, as determined by survival analysis (P<0.01, Figure 3C). These findings indicate that the CSN1201 deletion might attenuate the virulence of C. neoformans independently of its influence on thermotolerance.

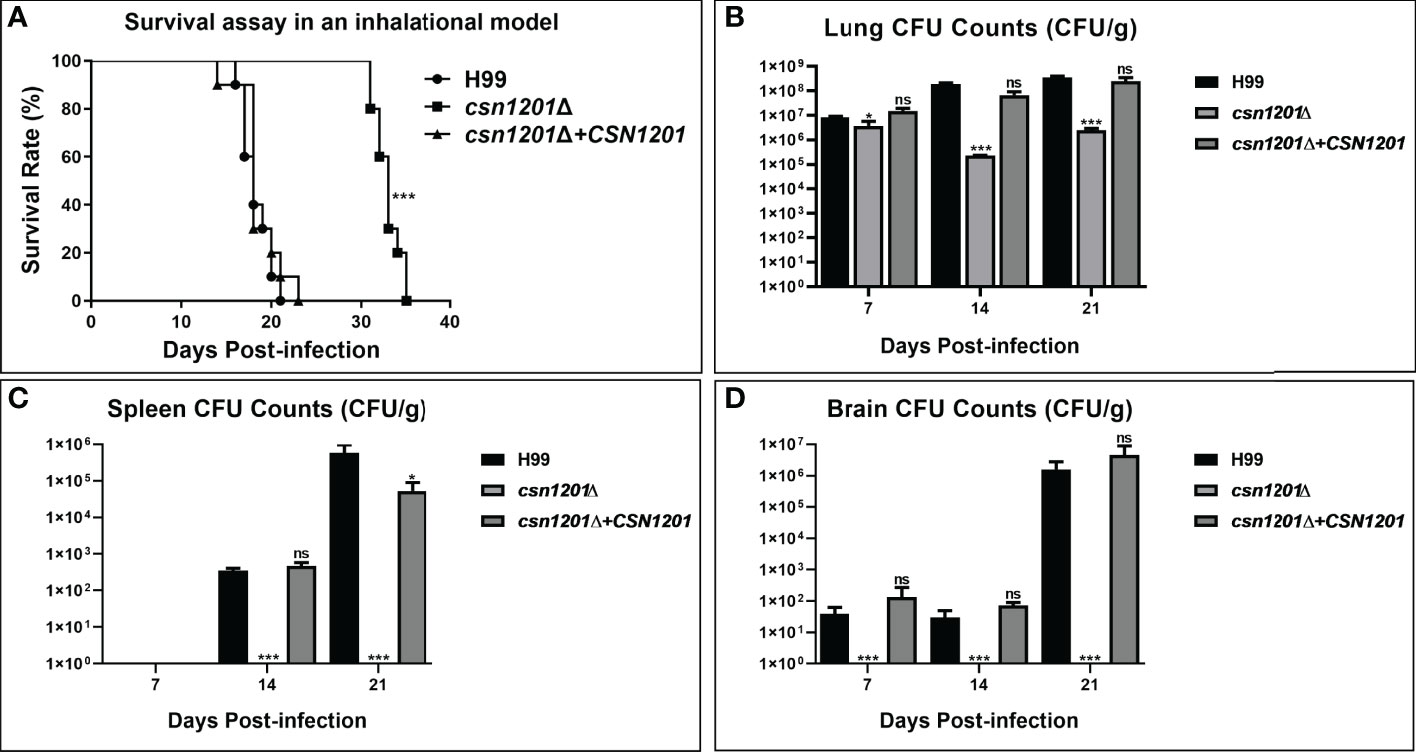

We further assessed the virulence of the csn1201Δ mutant in a murine inhalation model (Figure 4). Briefly, 10 female Balb/c mice were intranasally inoculated with 105 C. neoformans cells for each strain. Mice were monitored daily and sacrificed at predetermined clinical endpoints. All mice infected with the WT or reconstituted strains died within 23 days. Their average survival time was 18.3 ± 1.64 days and 18.6 ± 2.37 days, respectively. However, all mice infected with the csn1201Δ mutant succumbed to the infection by day 35. Their average survival time was extended to 32.9 days (P<0.001), suggesting a significant virulence defect (Figure 4A). Fungal burdens in different organs of each group were also examined at different time points. Viable yeast cells were discovered from the lungs of mice infected with the csn1201Δ mutant, but not from the spleen and brain. Intriguingly, a transient reduction in yeast viable numbers (2.28×105 ± 7.2×103 colony forming units (CFU)/g) was observed in the lungs of the csn1201Δ mutant group by 14 days, which was increased (2.47×106 ± 4.6×105 CFU/g) by 21 days (Figures 4B–D). In contrast, WT or reconstituted strain infected mice displayed significantly higher fungal burdens in all the tested organs at each time point (P<0.05). These results suggest that Csn1201 is essential for the pathogenesis of C. neoformans and is especially required for hematogenous dissemination from a pulmonary infection.

Figure 4 Csn1201 is essential for C. neoformans virulence in mouse inhalational infection models. (A) Survival assay in an inhalational model. Mouse lung (B), spleen (C), and brain (D) fungal burden assays were performed by counting fungal colonies after culturing serially diluted tissue lysate on YPD plates. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ns, no significant difference.

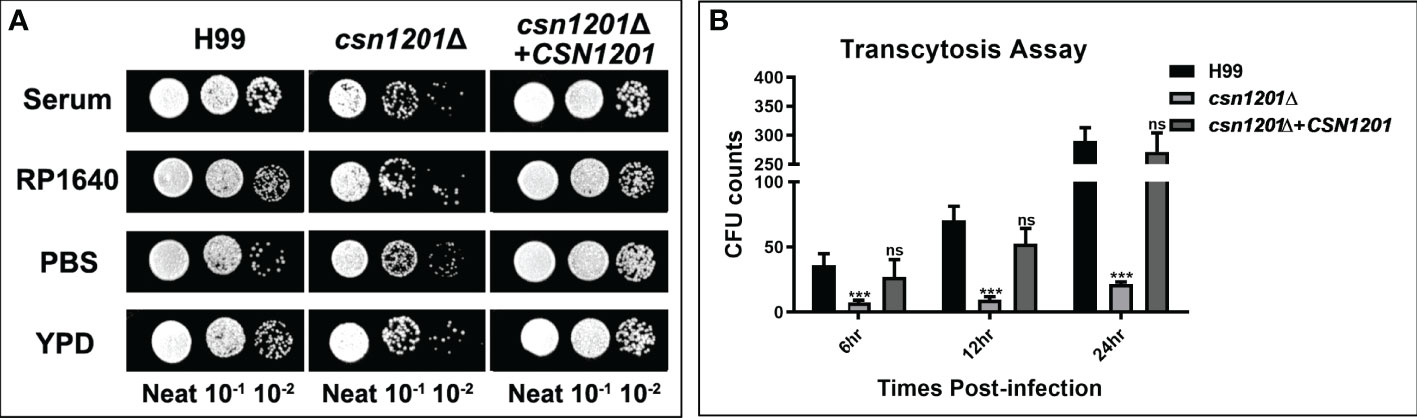

C. neoformans is a facultative intracellular pathogen that can evade the phagocytic cells in the extracellular environment (25). To determine the reason underlying the defective extrapulmonary dissemination by the csn1201Δ mutant, we assessed its ability to survive in serum. When exposed to human serum at 37°C for 4 days, the mutant strain displayed mild growth inhibition (Figure 5A). The survival defect observed in serum was not associated with nutrient starvation but contributed to enhanced high-temperature susceptibility, as the csn1201Δ mutant exhibited similar survival in RP1640, YPD medium, and PBS. We also tested the effects of CSN1201 deletion on cryptococcal transmigration across host brain microvascular endothelial cells via an in vitro BBB system. A significant reduction (86.5% at 12 h and 92.5% at 24 h) was noted in the transcytosis efficiency of the csn1201Δ mutant. The transmigration rate returned to that of the WT in the reconstituted strain (Figure 5B). Together, these data indicate that Csn1201 might promote the serum survival and BBB transcytosis of C. neoformans.

Figure 5 The CSN1201 deletion is involved in serum survival and in vitro blood-brain barrier transcytosis of C. neoformans. (A). Serum survival assay. Each strain was grown to saturation in YPD at 30°C, diluted 1:10 in mouse serum or YPD, and incubated at 37°C for 4 days. “Neat” represents the colony-forming units (CFU) concentration in serum. Strains were serially diluted 10-fold prior to being spotted onto YPD plates. (B). In vitro transcytosis assay of C. neoformans at 6, 12, and 24 hr. ***, P < 0.001; ns, no significant difference.

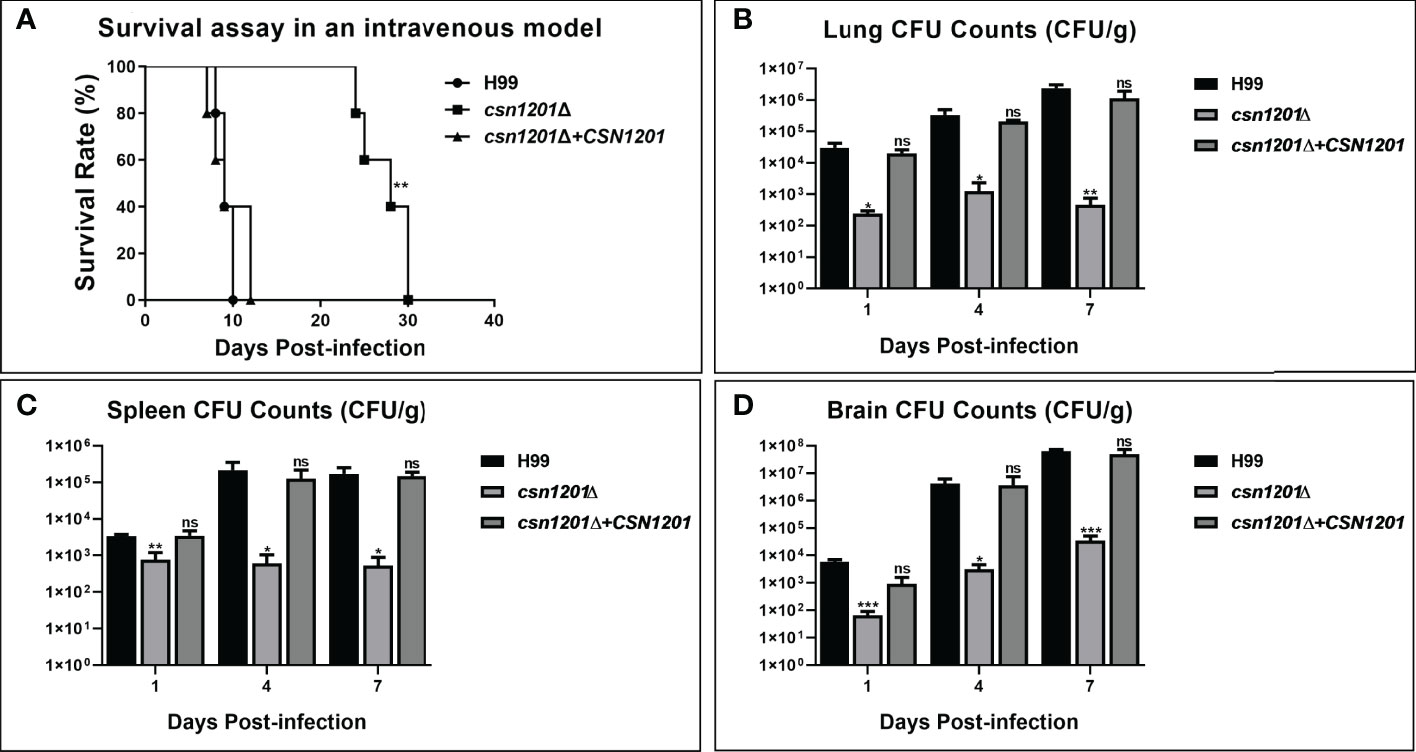

To further dissect the roles of Csn1201 in cryptococcal virulence and extrapulmonary dissemination, an intravenous mouse model was constructed as previously described. As expected, the CSN1201 deletion significantly prolonged the survival of mice intravenously infected with C. neoformans (27.4 ± 2.79 days, P<0.01 compared with the WT). In contrast, the average survival times of WT and csn1201Δ+CSN1201 mice were 9.2 ± 0.84 and 9.6 ± 2.30 days, respectively (Figure 6A). The fungal burden assay revealed a drastic reduction of fungal burden in different organs (lungs, spleens, and brains) from csn1201Δ-infected mice at each time point (1, 4, and 7 days post-infection; P<0.05, compared with the WT). However, distinct from the inhalational model (Figure 4) the csn1201Δ mutant still invaded the spleen and brain despite a remarkably lower fungal burden (Figures 6B–D). These results indicate that Csn1201 is required for the disseminated infection of C. neoformans but plays different roles in different infection routes.

Figure 6 The CSN1201 deletion attenuates virulence of C. neoformans in a murine intravenous model. (A) Survival assay in mouse intravenous cryptococcosis with different strains. Fungal burden assays in the lung (B), spleen (C), and brain (D). Organs were removed at 1, 4, and 7 days post-infection in the three groups.*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns, no significant difference.

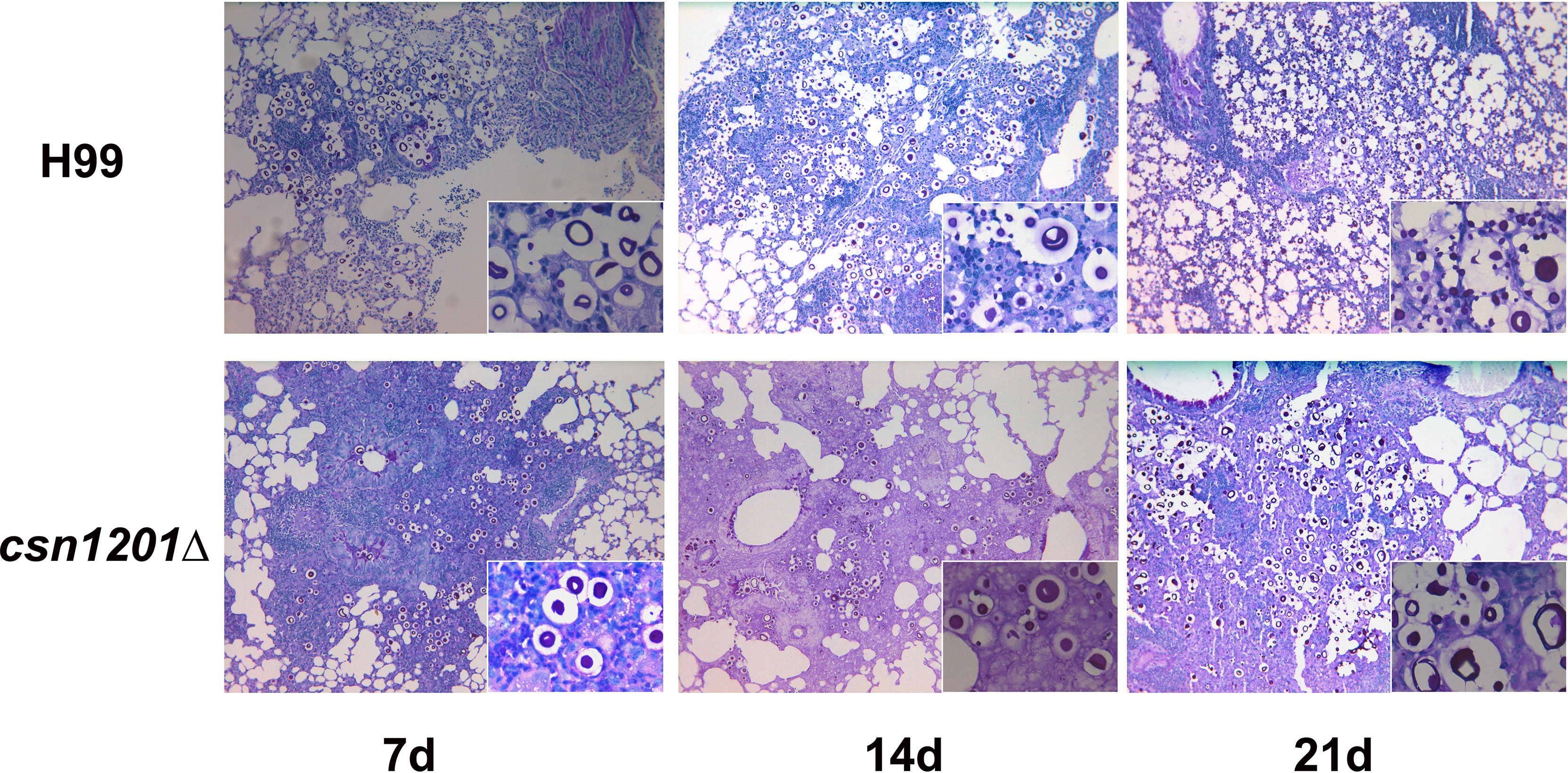

Based on the above results, we speculated that the absence of the csn1201Δ mutant strain in extrapulmonary dissemination might be attributed to its inability to breach the pulmonary immune defence in the inhalational model. To define the role of Csn1201 in pulmonary pathogenesis, we performed histological analyses of infected lungs at various time points in BALB/c mice (Figure 7). In BALB/c mice infected with the WT strain, a few yeast cells were confined to the alveolar space or the septum along with mild infiltration by neutrophils at 7 days post-infection. However, on day 14 post-infection, some of the alveolar architecture was destroyed because of the propagated cryptococci and severe inflammation. The inflammatory cells primarily comprised mononuclear cells with a few eosinophils. Pulmonary alveoli displayed diffuse destruction and were filled with a full field of fungal cells, but much fewer inflammatory cells at 21 days post-infection. Consistent with the quantitative fungal burden assay, the csn1201Δ strain showed attenuated proliferation in the lungs of mice. Yeast cells were primarily localized in interstitial tissues and were surrounded by marginal zones of mixed leukocyte infiltrates that formed diffuse granulomas at 7 days post-infection. The inflammatory cells primarily comprised epithelioid cells mixed with neutrophils and lymphocytes. Similarly, fungal cells were confined to pulmonary interstitia with reduced inflammation at 14 days post-infection. However, on day 21 post-infection, expansive cryptococcal clusters of the mutant were released from damaged epithelioid cells and caused severe destruction of lung tissues.

Figure 7 Csn1201 regulates host pulmonary inflammatory responses to C. neoformans. Representative photographs of haematoxylin and eosin-stained mouse lungs at different times post-infection.

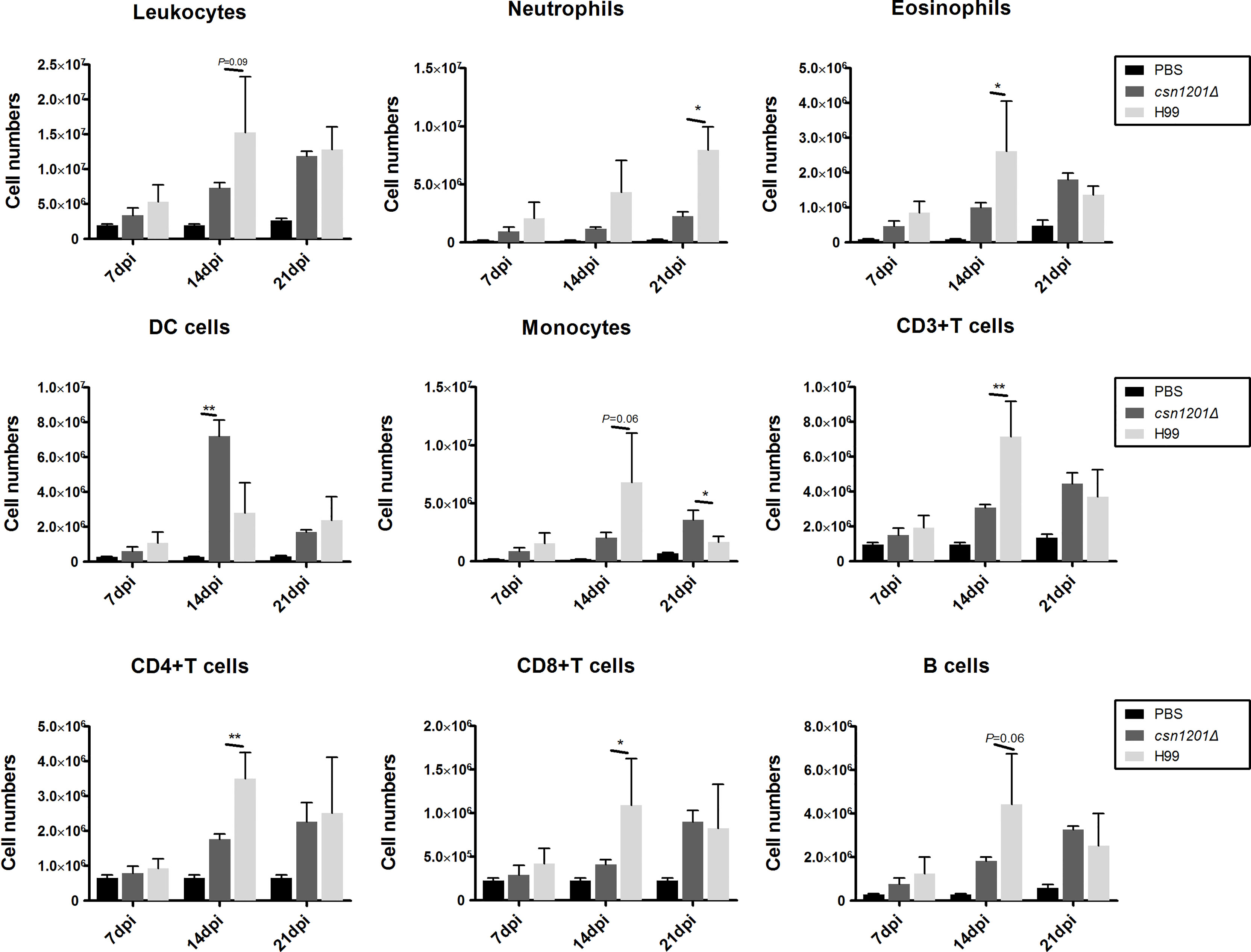

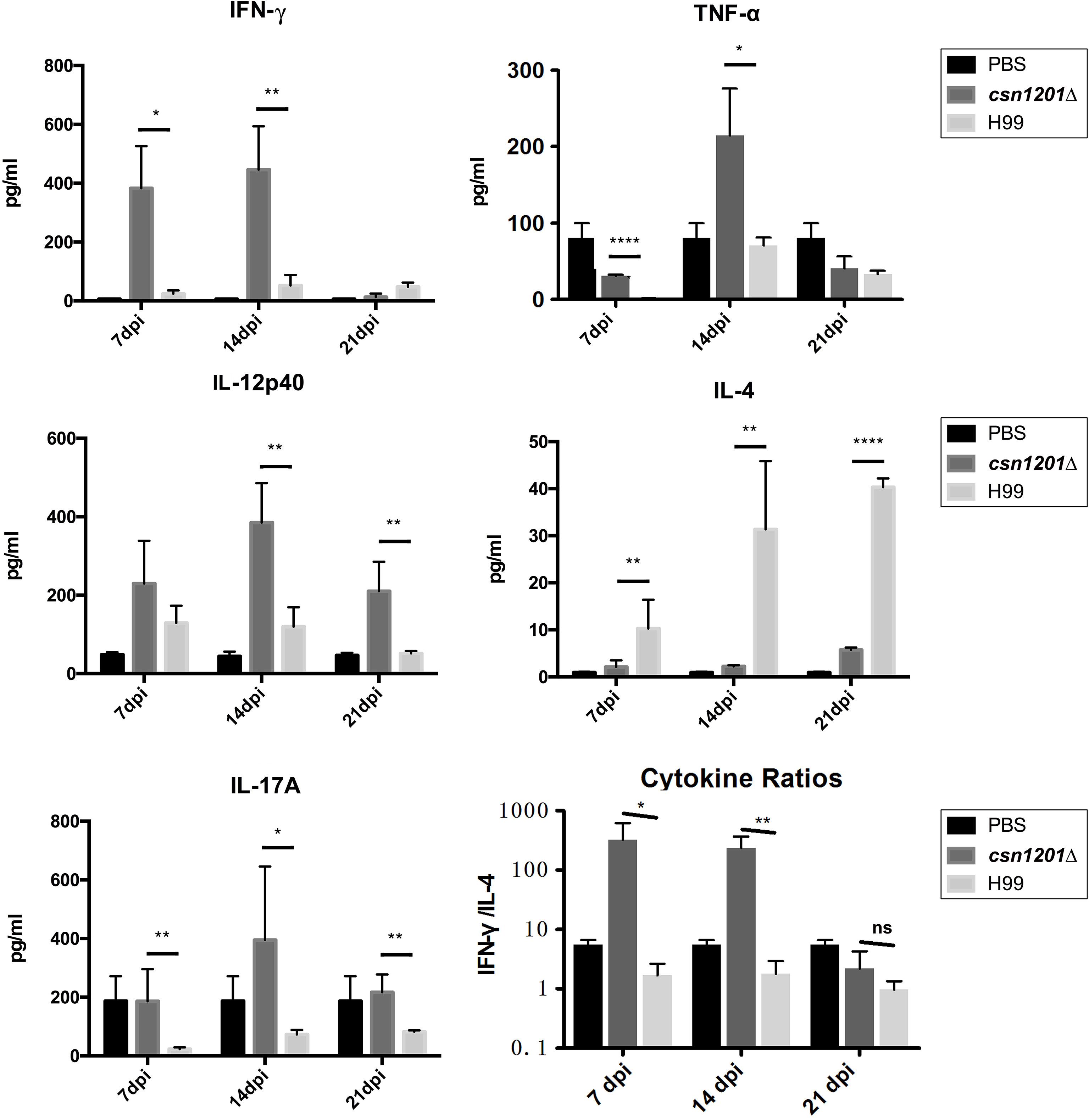

To assess the effect of cryptococcal Cns1201 deletion on pulmonary cellular responses, we isolated leukocytes from the lungs and conducted flow cytometry analysis at different time points (Figure 8). On day 7 post-infection, no significant difference was observed in the absolute numbers of total leukocytes and each subpopulation isolated from different groups. On day 14 post-infection, mouse lungs infected with the csn1201Δ strain showed substantially fewer total leukocytes, monocytes, T cells (including both CD4 + T cells and CD8 + T cells), B cells, and eosinophils, but significantly more dendritic cells than in the WT-infected mouse lungs. The lungs of csn1201Δ infected mice harboured fewer neutrophils, but significantly more monocytes, than those in the WT-infected group 21 days post-infection. Accordingly, the CSN1201 deletion induced a different pattern of pulmonary cytokines in C. neoformans-infected mice (Figure 9). The levels of IFN-γ, tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-12, and IL-17 in the csn1201Δ-infected mice were profoundly higher than those in the WT-infected mice, whereas expression of IL-4 was substantially diminished in the csn1201Δ-infected group compared with that in the WT-infected group. Thus, the CSN1201 deletion in C. neoformans altered the pulmonary inflammation pattern and promoted T cell polarization towards the protective Th1 and Th17 phenotypes.

Figure 8 The CSN1201 deletion alters the pulmonary inflammatory recruitment pattern during cryptococcal infection. Subsets of pulmonary immune cells from mice infected with C. neoformans were assessed by flow cytometry. Values are the mean ± SEM, n = 4 or more mice per group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Figure 9 The CSN1201 deletion promotes robust development of pulmonary Th1 and Th17 cytokine bias during cryptococcal infection. Specified inflammatory cytokines of C. neoformans-infected mice were analysed using ELISA. The Th1/Th2 bias ratio was calculated as IFN−γ/IL−4. Values are the mean ± SEM, n = 4 or more mice per group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, no significant difference.

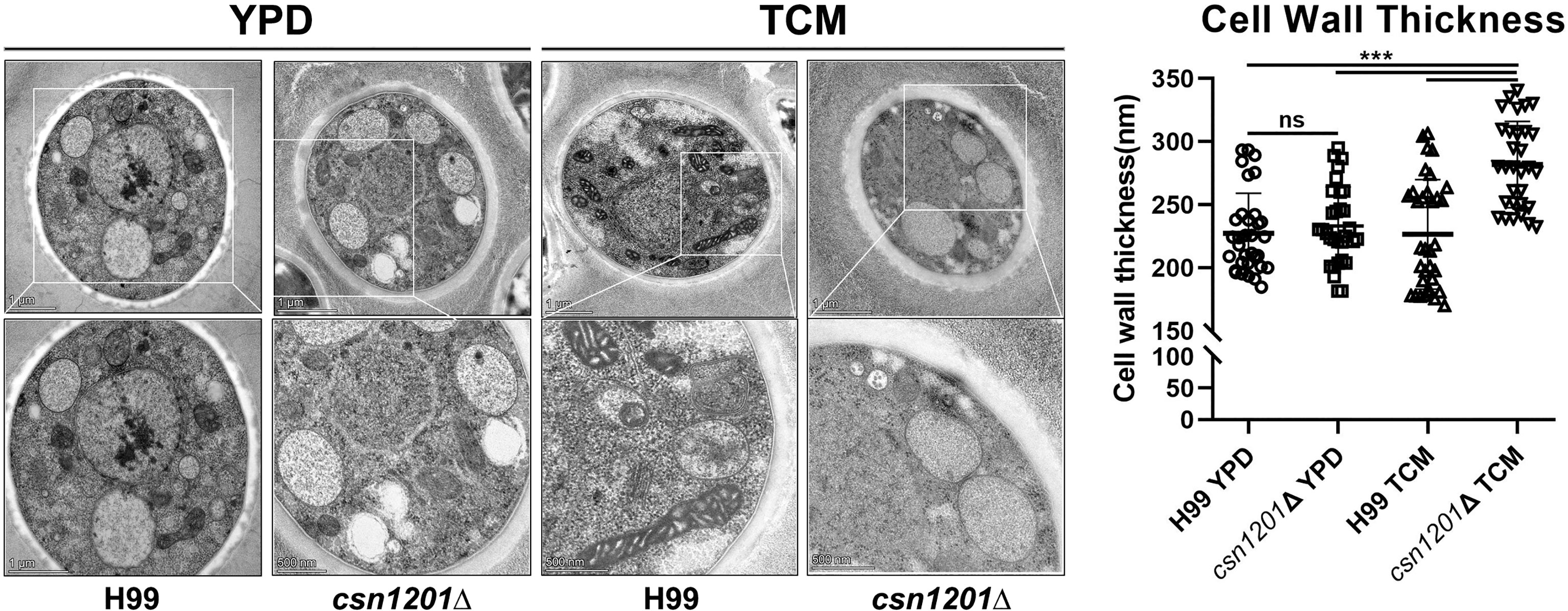

Alteration of pulmonary inflammation and immune responses observed in the csn1201Δ mutant infection suggest that the CSN1201 deletion might aberrantly expose an antigenic trigger of C. neoformans under the host environment in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effects of CSN1201 deletion on cryptococcal cell morphology, especially on the cell wall, using TEM. In YPD medium, there was no significant difference in cell morphology and cell wall thickness between the WT and mutant strains (H99, 227.4 ± 31.79 nm; csn1201Δ, 233.3 ± 30.87 nm). However, under tissue culture conditions (DMEM with 5% CO2 at 37°C), the mutant cells showed a remarkable increase in cell wall thickness compared to the WT cells (H99, 226.6 ± 43.37 nm; csn1201Δ, 281.9 ± 34.22 nm; P<0.001) (Figure 10). Additionally, we observed a noticeable increase in intracellular vacuoles and their matrixes in the mutant cells. These results indicate that Csn1201 might be implicated in the cell wall remodelling of C. neoformans under host-relevant conditions.

Figure 10 Csn1201 regulates cell wall thickness of C. neoformans under host-relevant conditions. Transmission electron microscopy of both the WT and csn1201Δ strains was carried out after incubation in either YPD medium or DMEM. ImageJ was utilized to quantify cell wall thickness. Results represent the mean ± SEM. ***, P < 0.001; ns, no significant difference.

In this study, we defined the roles of the uncharacterised protein, Csn1201, in cryptococcal virulence during pulmonary and disseminated infection. Deletion of CSN1201 significantly weakened the survival of C. neoformans within the lungs of infected mice. The decreased microbial burden was closely associated with protective immune responses, which were probably provoked by the exposure of cell wall components in the csn1201Δ mutant. Furthermore, CSN1201 expression also promotes the disseminated infection of C. neoformans. The decreased capacity of the csn1201Δ mutant for extrapulmonary dissemination was probably attributed to a combination of multiple factors, such as reduced fungal fitness under host conditions, attenuated BBB transcytosis, and pulmonary immune response. Overall, this study significantly advances the understanding regarding the interaction of cryptococcal pathogenic factors with host defences in vivo.

Previous studies identified Csn1201 as an uncharacterised virulence regulator of C. neoformans based on a large-scale screening of cryptococcal mutant libraries (14, 15). Herein we focussed on the effects of Csn1201 on host defence against a hypervirulent C. neoformans strain, H99, in multiple animal models. Results from murine models showed significantly prolonged survival and accelerated fungal clearance from different organs in csn1201Δ-infected mice, indicating that Csn1201 is required for pulmonary invasion and extrapulmonary dissemination of C. neoformans. Several lines of evidence indicate that the regulatory role of Csn1201 in virulence appears to be linked with fungal immune responses, rather than exclusively with the pathogenic fitness of C. neoformans. First, the csn1201Δ mutant displayed relatively good (although diminished) growth in mouse serum at 37°C, despite the mild defect in thermotolerance. Secondly, the CSN1201 deletion significantly attenuated cryptococcal virulence in the G. mellonella model at room temperature. G. mellonella is a facile invertebrate host to study fungal pathogenesis, which has an innate immune system similar to that of mammalians (26). Our data indicate that Csn1201 expression contributes to cryptococcal evasion of host innate immune responses, which is independent of its influence on fungal thermotolerance. Most importantly, viable yeast cells could be isolated from the spleen and brain of mice intravenously infected with the csn1201Δ mutant, but not in the inhalational model, indicating that the pulmonary immune response provoked by the mutant could block its extrapulmonary dissemination during natural disease progression.

The immunomodulatory role of cryptococcal Csn1201 was emphasized by pulmonary immunopathological analysis in the inhalational mouse model. The lungs of mice infected with csn1201Δ were characterised by granuloma formation in the early and middle stages of infection. Cryptococci were contained in interstitial tissues and surrounded by mixed inflammatory infiltrates, suggesting that the host immune system recognized and attempted to limit the csn1201Δ infection. Consistently, the CSN1201 deletion induced remarkable alleviation of cryptococcal expansion and overall inflammatory infiltration (typically by 14 days post-infection) in contrast to the uncontrolled growth and rapid extrapulmonary dissemination of the WT strain. Despite a weaker inflammatory response, infection with the csn1201Δ mutant induced recruitment of more dendritic cells at 14 days post-infection in the lungs. As critical innate immune cells, DCs can phagocytose and kill invading pathogens, as well as direct the adaptive immune response via antigen presentation (27, 28). The specific cytokine milieu (such as IFN-γ) or cell wall component exposure (such as mannoprotein) could stimulate protective immunity against C. neoformans by inducing early recruitment and activation of dendritic cells (29–31). We speculate that the csn1201Δ mutant might exploit a similar mechanism to stimulate the protective immunity of dendritic cells during the innate phases. This suggestion should be assessed. Furthermore, infection with the csn1201Δ mutant also resulted in a significant reduction of eosinophil and neutrophil infiltration during the middle and late phase. Eosinophils are a major source of IL-4 and contribute to a non-protective Th2 immune response, especially allergic inflammation during pulmonary cryptococcosis (32). Neutrophil depletion induces protective anti-fungal immunity by increasing inflammatory cytokine production and decreasing off-target tissue damage in the lungs (33, 34).

Cytokine analyses of pulmonary homogenates provided additional robust evidence of the effects of Csn1201-mediated, non-protective, immune modulation. On one hand, cryptococcal Csn1201 significantly enhanced the expression of Th2 cytokine IL-4 in the lungs of H99-infected mice, consistent with the accumulation of lung eosinophils. On the other hand, the CSN1201 deletion induced significant upregulation of Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-12) and inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-17). These upregulated cytokines are essential for protective immunity against C. neoformans infection (22, 35–37). Of the aforementioned cytokines, IFN-γ is probably crucial for the csn1201Δ-induced protective immune responses. Previous studies have reported that infection with an IFN-γ-producing strain of C. neoformans induces similar alteration of cytokine profiles in mouse lungs as observed in the present study, but this is not observed in mice infected with a TNF-α-producing strain (22, 31, 38).

The protective immune response is probably attributed to the exposure of cell wall components in the csn1201Δ mutant. We observed that the CSN1201 deletion noticeably enhanced cell wall thickness and mildly decreased extracellular capsule thickness under host-relevant conditions in C. neoformans. In addition, the csn1201Δ mutant exhibited enhanced sensitivity to cell wall or membrane-damaging agents. Alteration of cell wall components or its regulators in C. neoformans reportedly stimulate aberrant host immune responses and thus change the outcomes of cryptococcal infection (12, 39, 40). A prior bioinformatics analysis suggested that the PCI domain mediates and stabilises protein–protein interactions within multiprotein complexes, such as the 26S proteasome lid and the COP9 signalosome (41). Therefore, we speculate that Csn1201 might exploit a similar mechanism to regulate cell wall remodelling and thus alter the host immune response. This remains to be investigated.

In addition to modulating pulmonary immunity, Csn1201 is also essential for the extrapulmonary dissemination of C. neoformans. Regardless of the infection route, the csn1201Δ mutant exhibited a significantly reduced infectivity in different murine organs (especially the central nervous system). The decreased pathogenicity of csn1201Δ was closely associated with reduced fungal fitness under stressful host conditions in vivo. The CSN1201 deletion significantly weakened cryptococcal tolerance to various stressors in vitro, intracellular survival in macrophages, and transcytosis efficiency across the BBB. C. neoformans utilizes multiple virulence factors to adapt to the hostile environment in vivo (42). Csn1201 positively regulates melanin production but has no effect on capsule synthesis in the WT strain, KN99α (14, 15). However, in the present study, the CSN1201 deletion in the H99 hypervirulent strain resulted in reduced capsule size and a mild growth defect at the host temperature, but did not affect melanisation, which reflects a functional reconfiguring of homologous genes during cryptococcal microevolution. Each pathogenic factor provides a relatively distinct contribution to the overall virulence of C. neoformans. The regulatory role of Csn1201 in cryptococcal pathogenicity is dependent on a combination of multiple pathogenic factors and their interaction with the host. More importantly, Csn1201 might be a unique protein that is evolutionarily specific to some fungal species, facilitating the future development of therapeutic interventions against cryptococcosis.

In summary, our study provides novel insights into the role of the cryptococcal Csn1201 protein in a hypervirulent C. neoformans strain. Csn1201 promotes pulmonary growth and extrapulmonary dissemination by modulating both innate and adaptive host responses alongside fungal pathogenic fitness. Further experiments are necessary to determine how C. neoformans utilizes Csn1201 to regulate the molecules on the surface of pathogens that can avoid host immune activation, thus leading to cryptococcal pathogenesis.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?id=235443.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital.

Y-lY, Y-bF, J-lG, and WF conceived, designed and performed the experiments. LG, CZ, and WF analysed the data. J-lG, W-hP, and WF drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (81501728, 82072259, 81772159, 82073453 and 81902041).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.890258/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Melanin production assay. Strains were grown on Niger Seed or Caffeic Acid medium at 30°C.

Supplementary Table 1 | Strains and plasmids used in this study.

Supplementary Table 2 | Primers used in this study.

1. Gushiken AC, Saharia KK, Baddley JW. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am (2021) 35(2):493–514. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2021.03.012

2. Rajasingham R, Smith RM, Park BJ, Jarvis JN, Govender NP, Chiller TM, et al. Global Burden of Disease of HIV-Associated Cryptococcal Meningitis: An Updated Analysis. Lancet Infect Dis (2017) 17(8):873–81. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30243-8

3. Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis: A Model for the Understanding of Infectious Diseases. J Clin Invest (2014) 124(5):1893–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI75241

4. Fang W, Fa Z, Liao W. Epidemiology of Cryptococcus and Cryptococcosis in China. Fungal Genet Biol (2015) 78:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.10.017

5. Ballou ER, Johnston SA. The Cause and Effect of Cryptococcus Interactions With the Host. Curr Opin Microbiol (2017) 40:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.10.012

6. Maziarz EK, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am (2016) 30(1):179–206. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.006

7. Casadevall A, Coelho C, Alanio A. Mechanisms of Cryptococcus Neoformans-Mediated Host Damage. Front Immunol (2018) 9:855. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00855

8. Osterholzer JJ, Surana R, Milam JE, Montano GT, Chen GH, Sonstein J, et al. Cryptococcal Urease Promotes the Accumulation of Immature Dendritic Cells and a non-Protective T2 Immune Response Within the Lung. Am J Pathol (2009) 174(3):932–43. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080673

9. Qiu Y, Davis MJ, Dayrit JK, Hadd Z, Meister DL, Osterholzer JJ, et al. Immune Modulation Mediated by Cryptococcal Laccase Promotes Pulmonary Growth and Brain Dissemination of Virulent Cryptococcus Neoformans in Mice. PLoS One (2012) 7(10):e47853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047853

10. He X, Lyons DM, Toffaletti DL, Wang F, Qiu Y, Davis MJ, et al. Virulence Factors Identified by Cryptococcus Neoformans Mutant Screen Differentially Modulate Lung Immune Responses and Brain Dissemination. Am J Pathol (2012) 181(4):1356–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.012

11. Masso-Silva J, Espinosa V, Liu TB, Wang Y, Xue C, Rivera A. The F-Box Protein Fbp1 Shapes the Immunogenic Potential of Cryptococcus Neoformans. mBio (2018) 9(1):e01828–17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01828-17

12. Hole CR, Lam WC, Upadhya R, Lodge JK. Cryptococcus Neoformans Chitin Synthase 3 Plays a Critical Role in Dampening Host Inflammatory Responses. mBio (2020) 11(1):e03373–19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03373-19

13. O'Meara TR, Holmer SM, Selvig K, Dietrich F, Alspaugh JA. Cryptococcus Neoformans Rim101 Is Associated With Cell Wall Remodeling and Evasion of the Host Immune Responses. MBio (2013) 4(1):e00522–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00522-12

14. Liu OW, Chun CD, Chow ED, Chen C, Madhani HD, Noble SM. Systematic Genetic Analysis of Virulence in the Human Fungal Pathogen Cryptococcus Neoformans. Cell (2008) 135(1):174–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.046

15. Desalermos A, Tan X, Rajamuthiah R, Arvanitis M, Wang Y, Li D, et al. A Multi-Host Approach for the Systematic Analysis of Virulence Factors in Cryptococcus Neoformans. J Infect Dis (2015) 211(2):298–305. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu441

16. Zhao J, Yang Y, Fan Y, Yi J, Zhang C, Gu Z, et al. Ribosomal Protein L40e Fused With a Ubiquitin Moiety Is Essential for the Vegetative Growth, Morphological Homeostasis, Cell Cycle Progression, and Pathogenicity of Cryptococcus Neoformans. Front Microbiol (2020) 11:570269. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.570269

17. Fang W, Price MS, Toffaletti DL, Tenor J, Betancourt-Quiroz M, Price JL, et al. Pleiotropic Effects of Deubiquitinating Enzyme Ubp5 on Growth and Pathogenesis of Cryptococcus Neoformans. PLoS One (2012) 7(6):e38326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038326

18. Blankenship JR, Wormley FL, Boyce MK, Schell WA, Filler SG, Perfect JR, et al. Calcineurin is Essential for Candida Albicans Survival in Serum and Virulence. Eukaryot Cell (2003) 2(3):422–30. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.3.422-430.2003

19. Reese AJ, Yoneda A, Breger JA, Beauvais A, Liu H, Griffith CL, et al. Loss of Cell Wall Alpha(1-3) Glucan Affects Cryptococcus Neoformans From Ultrastructure to Virulence. Mol Microbiol (2007) 63(5):1385–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05551.x

20. Sang J, Yang Y, Fan Y, Wang G, Yi J, Fang W, et al. Isolated Iliac Cryptococcosis in an Immunocompetent Patient. PloS Negl Trop Dis (2018) 12(3):e0006206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006206

21. Fang W, Fa ZZ, Xie Q, Wang GZ, Yi J, Zhang C, et al. Complex Roles of Annexin A2 in Host Blood-Brain Barrier Invasion by Cryptococcus Neoformans. CNS Neurosci Ther (2017) 23(4):291–300. doi: 10.1111/cns.12673

22. Fa Z, Xu J, Yi J, Sang J, Pan W, Xie Q, et al. TNF-α-Producing Cryptococcus Neoformans Exerts Protective Effects on Host Defenses in Murine Pulmonary Cryptococcosis. Front Immunol (2019) 10:1725. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01725

23. Fa Z, Xie Q, Fang W, Zhang H, Zhang H, Xu J, et al. RIPK3/Fas-Associated Death Domain Axis Regulates Pulmonary Immunopathology to Cryptococcal Infection Independent of Necroptosis. Front Immunol (2017) 8:1055. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01055

24. Gilbert AS, Wheeler RT, May RC. Fungal Pathogens: Survival and Replication Within Macrophages. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med (2014) 5(7):a019661. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019661

25. Botts MR, Hull CM. Dueling in the Lung: How Cryptococcus Spores Race the Host for Survival. Curr Opin Microbiol (2010) 13(4):437–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.05.003

26. Kavanagh K, Reeves EP. Exploiting the Potential of Insects for In Vivo Pathogenicity Testing of Microbial Pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev (2004) 28(1):101–12. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.002

27. Chen GH, Teitz-Tennenbaum S, Neal LM, Murdock BJ, Malachowski AN, Dils AJ, et al. Local GM-CSF-Dependent Differentiation and Activation of Pulmonary Dendritic Cells and Macrophages Protect Against Progressive Cryptococcal Lung Infection in Mice. J Immunol (2016) 196(4):1810–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501512

28. Wozniak KL. Interactions of Cryptococcus With Dendritic Cells. J Fungi (Basel) (2018) 4(1):36. doi: 10.3390/jof4010036

29. Pietrella D, Corbucci C, Perito S, Bistoni G, Vecchiarelli A. Mannoproteins From Cryptococcus Neoformans Promote Dendritic Cell Maturation and Activation. Infect Immun (2005) 73(2):820–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.820-827.2005

30. Wormley FL Jr, Perfect JR, Steele C, Cox GM. Protection Against Cryptococcosis by Using a Murine Gamma Interferon-Producing Cryptococcus Neoformans Strain. Infect Immun (2007) 75(3):1453–62. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00274-06

31. Wozniak KL, Ravi S, Macias S, Young ML, Olszewski MA, Steele C, et al. Insights Into the Mechanisms of Protective Immunity Against Cryptococcus Neoformans Infection Using a Mouse Model of Pulmonary Cryptococcosis. PLoS One (2009) 4(9):e6854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006854

32. Piehler D, Stenzel W, Grahnert A, Held J, Richter L, Köhler G, et al. Eosinophils Contribute to IL-4 Production and Shape the T-Helper Cytokine Profile and Inflammatory Response in Pulmonary Cryptococcosis. Am J Pathol (2011) 179(2):733–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.025

33. Wozniak KL, Kolls JK, Wormley FL. Depletion of Neutrophils in a Protective Model of Pulmonary Cryptococcosis Results in Increased IL-17A Production by γδ T Cells. BMC Immunol (2012) 13:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-13-65

34. Mednick AJ, Feldmesser M, Rivera J, Casadevall A. Neutropenia Alters Lung Cytokine Production in Mice and Reduces Their Susceptibility to Pulmonary Cryptococcosis. Eur J Immunol (2003) 33(6):1744–53. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323626

35. Rohatgi S, Pirofski LA. Host Immunity to Cryptococcus Neoformans. Future Microbiol (2015) 10(4):565–81. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.132

36. Leopold WCM, Hole CR, Campuzano A, Castro-Lopez N, Cai H, Van Dyke MCC, et al. IFN-γ Immune Priming of Macrophages In Vivo Induces Prolonged STAT1 Binding and Protection Against Cryptococcus Neoformans. PloS Pathog (2018) 14(10):e1007358. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007358

37. Movahed E, Cheok YY, Tan GMY, Lee CYQ, Cheong HC, Velayuthan RD, et al. Lung-Infiltrating T Helper 17 Cells as the Major Source of Interleukin-17A Production During Pulmonary Cryptococcus Neoformans Infection. BMC Immunol (2018) 19(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12865-018-0269-5

38. Hardison SE, Ravi S, Wozniak KL, Young ML, Olszewski MA, Wormley FL. Pulmonary Infection With an Interferon-Gamma-Producing Cryptococcus Neoformans Strain Results in Classical Macrophage Activation and Protection. Am J Pathol (2010) 176(2):774–85. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090634

39. Ost KS, Esher SK, Leopold WCM, Walker L, Wagener J, Munro C, et al. Rim Pathway-Mediated Alterations in the Fungal Cell Wall Influence Immune Recognition and Inflammation. MBio (2017) 8(1):e02290–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02290-16

40. Esher SK, Ost KS, Kohlbrenner MA, Pianalto KM, Telzrow CL, Campuzano A, et al. Defects in Intracellular Trafficking of Fungal Cell Wall Synthases Lead to Aberrant Host Immune Recognition. PLoS Pathog (2018) 14(6):e1007126. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007126

41. Scheel H, Hofmann K. Prediction of a Common Structural Scaffold for Proteasome Lid, COP9-Signalosome and Eif3 Complexes. BMC Bioinf (2005) 6:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-71

Keywords: Cryptococcus neoformans, Csn1201, immune evasion, cell wall remodelling, virulence

Citation: Yang Y-l, Fan Y-b, Gao L, Zhang C, Gu J-l, Pan W-h and Fang W (2022) Cryptococcus neoformans Csn1201 Is Associated With Pulmonary Immune Responses and Disseminated Infection. Front. Immunol. 13:890258. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.890258

Received: 05 March 2022; Accepted: 09 May 2022;

Published: 02 June 2022.

Edited by:

Cunwei Cao, Guangxi Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Tong-Bao Liu, Southwest University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Yang, Fan, Gao, Zhang, Gu, Pan and Fang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Fang, d2VpZmFuZzA4MTc4MkAxNjMuY29t; Wei-hua Pan, cGFud2VpaHVhOUBzaW5hLmNvbQ==; Ju-lin Gu, d3VqZ2psQDEyNi5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.