94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol., 13 September 2022

Sec. Viral Immunology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.857905

This article is part of the Research TopicImmune Responses to HIV Infection: Basic, Clinical and Translational Research in East and Southeast AsiaView all 43 articles

Yi Zhou1,2†

Yi Zhou1,2† Shaoli Huang3†

Shaoli Huang3† Mingting Cui4

Mingting Cui4 Zhihui Guo4

Zhihui Guo4 Haotong Tang2

Haotong Tang2 Hang Lyu1

Hang Lyu1 Yuxin Ni5,6

Yuxin Ni5,6 Ying Lu5,6

Ying Lu5,6 Yunlong Feng7

Yunlong Feng7 Yuyu Wang7

Yuyu Wang7 Fengshi Jing8,9

Fengshi Jing8,9 Shanzi Huang1

Shanzi Huang1 Jiarun Li1

Jiarun Li1 Yao Xu10*

Yao Xu10* Wenhua Mei1*

Wenhua Mei1*Background: To assess whether HIV self-testing (HIVST) has a better performance in identifying HIV-infected cases than the facility-based HIV testing (HIVFBT) approach.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among men who have sex with men (MSM) by using an online questionnaire (including information on sociodemographic, sexual biography, and HIV testing history) and blood samples (for limiting antigen avidity enzyme immunoassay, gene subtype testing, and taking confirmed HIV test). MSM who were firstly identified as HIV positive through HIVST and HIVFBT were compared. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to explore any association between both groups and their subgroups.

Results: In total, 124 MSM HIV cases were identified from 2017 to 2021 in Zhuhai, China, including 60 identified through HIVST and 64 through HIVFBT. Participants in the HIVST group were younger (≤30 years, 76.7% vs. 46.9%), were better educated (>high school, 61.7% vs. 39.1%), and had higher viral load (≥1,000 copies/ml, 71.7% vs. 50.0%) than MSM cases identified through HIVFBT. The proportion of early HIV infection in the HIVST group was higher than in the HIVFBT group, identified using four recent infection testing algorithms (RITAs) (RITA 1, 46.7% vs. 25.0%; RITA 2, 43.3% vs. 20.3%; RITA 3, 30.0% vs. 14.1%; RITA 4, 26.7% vs. 10.9%; all p < 0.05).

Conclusions: The study showed that HIVST has better HIV early detection among MSM and that recent HIV infection cases mainly occur in younger and better-educated MSM. Compared with HIVFBT, HIVST is more accessible to the most at-risk population on time and tends to identify the case early. Further implementation studies are needed to fill the knowledge gap on this medical service model among MSM and other target populations.

In 2020, United Nations Member States committed to implementing 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in which one of the motivations/goals is to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030 via using the Fast-Track approach with the 95-95-95 targets: by 2030, 95% of people living with HIV (PLWH) should know their HIV status, 95% of people who know their status should be on antiretroviral treatment (ART), and 95% of those on treatment should be virally suppressed (1–3). Acute and primary HIV infection, also known as early HIV infection (EHI), is the early stage of HIV infection. Acute HIV infection occurs 2 to 4 weeks after infection with both HIV RNA and p24 antigen present, and primary HIV infection occurs 6 months after infection. The high concentration of the virus during EHI leads to increased infectiousness, possibly as much as 26 times greater than during chronic infection (4). Improving the identification of EHI cases is important for HIV infection management to achieve the goal by 2030. However, in China, only 68% of people living with HIV were aware of their serology status by the end of 2015 (5). Only 15% of the identified cases are EHI in some high HIV prevalence provinces, which means most of the cases were diagnosed late (5). Thus, effective ways for early identification of EHIs are needed.

In the past years, several laboratory-based assays have been tested to identify early HIV infection according to the natural serological responses after infection (6). However, they were based on population data. When applied to individuals, false-positive results that classify long-term infection as a recent infection could occur. Thus, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) recommend using recent infection testing algorithms (RITAs) to improve the accuracy of identifying recent HIV infections, which integrate HIV recency tests with multiple routinely used clinical assays (7). In the other words, a RITA is a combination of laboratory tests used to classify an HIV infection as recent (recent infections were acquired generally within 4 to 12 months) (8) or long-term (9). The limiting antigen avidity enzyme immunoassay (LAg-EIA) is one of the widely used serological assays to identify EHI (10–12). CD4+ T-cell count and viral load (VL) test are the other two clinical assays used for the majority of RITAs to reclassify recent infections (7). In comparison to the sole use of serological assays for the classification of recent HIV infection, RITAs, which combine various clinical information with the HIV recency assay, have been proven to accurately classify recent infection cases and effectively reduce false recent rate (FRR) (7).

Voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) and provider-initiated testing and counselling (PITC) are the majority of HIV tests conducted within health facilities and still represent the most common testing approach in most countries (3, 13). However, facility-based HIV testing (HIVFBT) is not accessible to the most at-risk population on time and tends to identify the case late. Thus, we will need a decentralized tool to reach the most at-risk participants.

The WHO encourages HIV rapid tests for screening high-risk populations (3, 14). In July 2019, 77 countries adopted policies or guidelines for the implementation and support of HIV self-testing (HIVST) (15). In China, the demand for and acceptability of HIVST among men who have sex with men (MSM) had been high, and many local community-based organizations were working with health bureaus in piloting HIVST among MSM (16, 17). A recent study has demonstrated that a model of social media-based HIVST with a secondary distribution is feasible and acceptable among MSM in China (18). HIVST can be used to identify first-time testers, promote HIV case identification, and link to care (18).

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether HIVST can identify PLWH earlier than the facility-based method.

A community-based project was conducted from January 2017 to September 2021 to collect data on newly diagnosed HIV cases using two different approaches, HIVST and HIVFBT, among MSM in Zhuhai, China. Zhuhai is one of the first sites to pilot HIVST among Chinese MSM. It is estimated that there are 17,000 MSM living in Zhuhai, of whom 7% are HIV positive (19, 20). For HIVST, Zhuhai Center for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) and Zhuhai Xutong Voluntary Services Center (short for Xutong), a gay community-led organization, initiated a social media-based online system in 2016 for MSM to apply for free dual HIV/syphilis self-testing kits via Xutong’s public WeChat account. WeChat is one of the major communication social media platforms used for messaging, public surveys, and monetary transactions in China. The Lingnan Community Health Service Center is one of the HIVFBT sites in Zhuhai and accounted for more than 90% of HIVFBT among MSM each year. Therefore, for HIVFBT, the Lingnan Community Health Service Center in Zhuhai was selected as an HIVFBT site for recruiting participants.

Adults who were a) biologically identified as men, b) aged 18 years and over, c) newly diagnosed as HIV positive, d) ever had anal sexual contact with a same-gender partner, and e) agreed to provide blood samples in Zhuhai were eligible for participation. Participants who used HIVST were classified into the HIVST group. Participants who adopted HIV testing at Lingnan Community Health Service Center and had not applied for free dual HIV/syphilis self-testing kits via Xutong’s public WeChat account were classified into the HIVFBT group. In addition, participants whose results of CD4+ T-cell count and VL were both not uploaded to the case-reporting system until 1 month after confirmed HIV tests were excluded.

After all eligible participants provided written consent, they had to complete an online survey including information about sociodemographic characteristics (age, education, marital status, and residence), sexual biography (gender identity, sexual orientation, and sexual orientation disclosure), and HIV testing history. A blood sample of 5 ml was taken from each individual for HIV serological testing, stored in a collection tube without anticoagulants, and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5–10 min to obtain a serum sample. Then serum samples were kept at −20°C until processing. Blood specimens were firstly confirmed by Western blotting (HIV 2.2 WB, Genelabs Diagnostics, Singapore). Confirmed HIV cases were also tested for CD4+ T-cell count and viral load. Serological LAg-EIA assay (Beijing Kinghawk Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used to classify recent infection status. All laboratory tests were conducted in Zhuhai CDC.

All data analyses were conducted in SPSS 26.0 for Windows 10. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare LAg-EIA, sociodemographic characteristics, and sexual behaviors between the HIVST and HIVFBT groups. Each group was also classified into four subgroups using different RITAs for the same analyses above: RITA 1 used the LAg-EIA only; RITA 2 combined the LAg-EIA with CD4+ T-cell count; RITA 3 combined the LAg-EIA with viral load; RITA 4 used the LAg-EIA, CD4+ T-cell count, and viral load together. Univariate and multivariate logistic analyses were used to identify factors associated with recent HIV infection. Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Permission to conduct the project was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Zhuhai CDC (Ethics documents ID No. [2021]08).

In total, 124 (99.2%) of the 125 eligible men agreed to participate. Of them, 60 (48.0%) were from the HIVST group, while the other 64 (51.2%) were from the HIVFBT group.

Compared with the HIVFBT group, participants in the HIVST group tended to be younger (aged 30 years or under, 76.7% vs. 46.9%, p = 0.001) and well educated (>high school, 61.7% vs. 39.1%, p = 0.012) and have had higher baseline viral load (≥1,000 copies/ml, 71.7% vs. 50.0%, p < 0.001) (Table 1). Participants in both groups had similar marital status, ethnic groups, baseline CD4+ T-cell counts, and genotype.

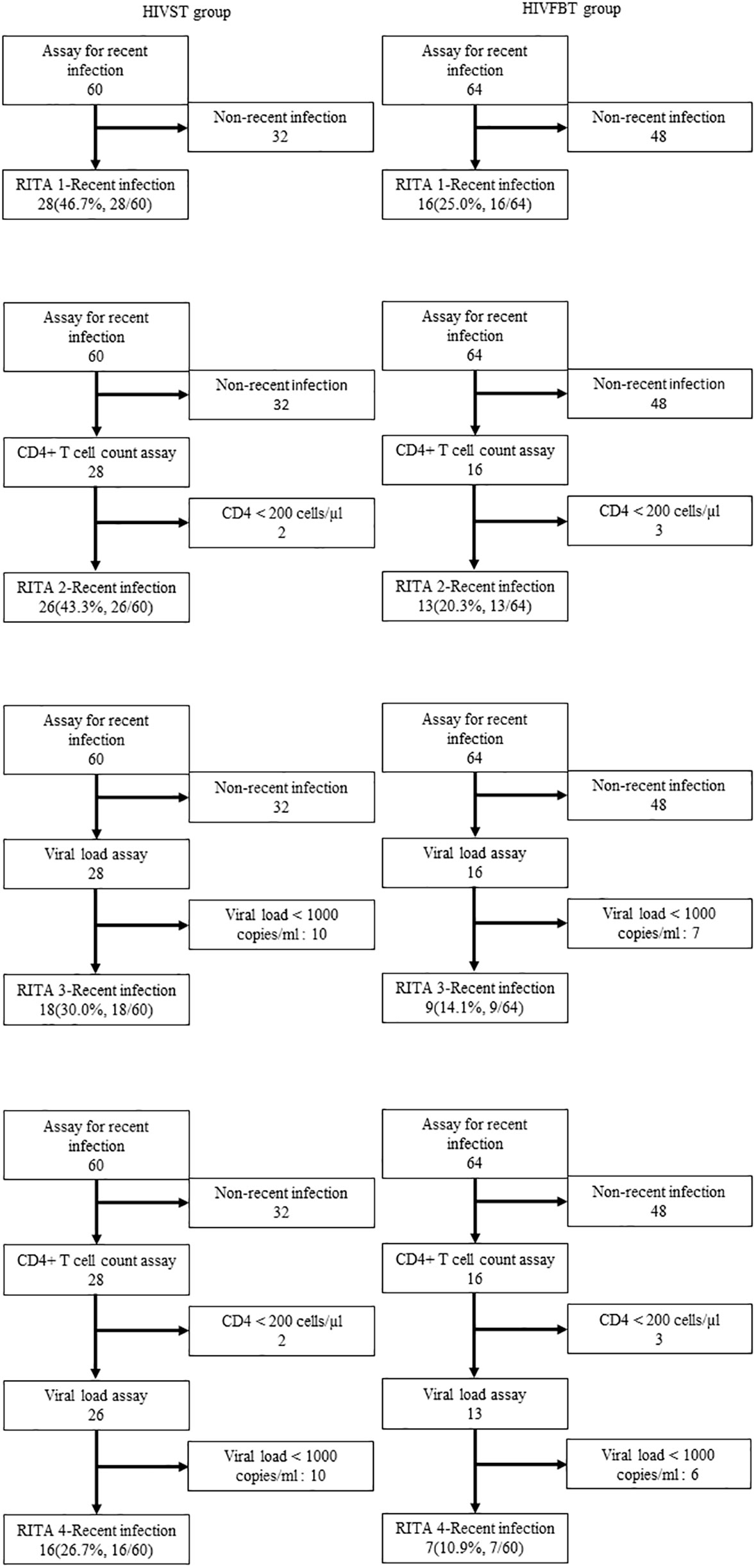

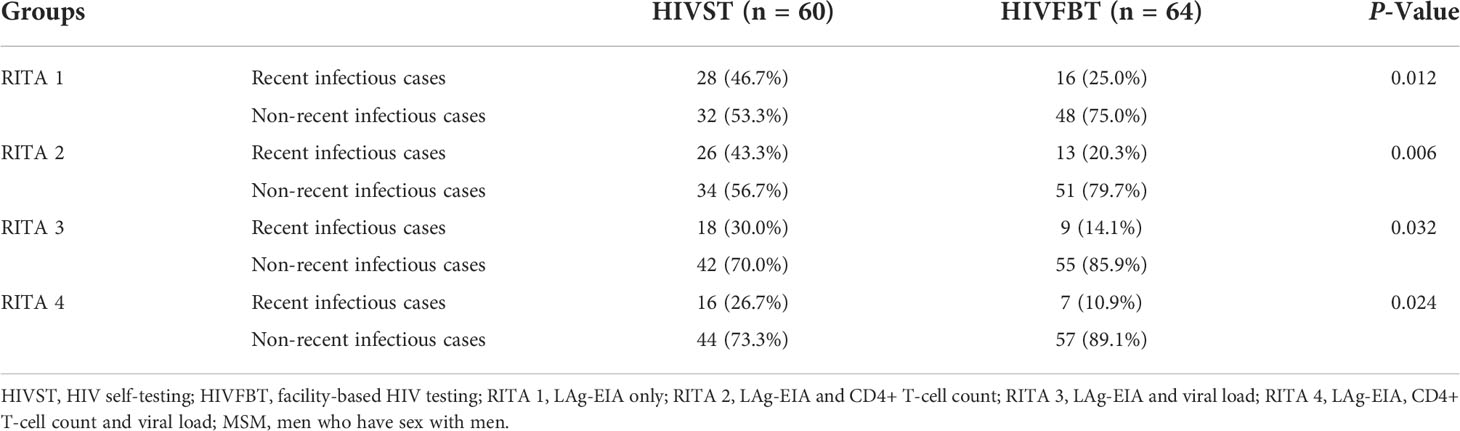

Four RITAs were implemented to classify recent HIV infection cases between the HIVST group and the HIVFBT group (Figure 1). According to the results of all RITAs, recent infectious cases were significantly associated with HIVST (Table 2). RITA 1 classified 28 (45.9%) recent infection cases from the HIVST group and 16 (25.0%) from the HIVFBT group with a strong significant difference. In RITA 2, two cases from the HIVST group were reclassified as non-recent due to CD4+ T-cell count <200 cells/µl, and three cases from the HIVFBT group were reclassified as non-recent due to CD4+ T-cell count <200 cells/µl. Together, RITA 2 classified a significant difference between the HIVST group and the HIVFBT group as 26 (42.5%) versus 13 (20.3%) cases, respectively. In RITA 3, 10 cases from the HIVST group were reclassified as non-recent due to VL < 1,000 copies/ml, and seven cases from the HIVFBT group were reclassified as non-recent due to VL < 1,000 copies/ml. The HIVST group (18, 29.5%) was significantly different from the HIVFBT group (9, 14.1%) when RITA 3 was used. RITA 4 combined all three assays and reclassified 44 cases in total as non-recent according to the exclusion criteria of CD4+ T-cell count and viral load (30 cases excluded for each) from the HIVST group and 57 cases from the HIVFBT group. RITA 4 identified significantly different numbers of recent infection cases in two groups, 16 (26.7%) from the HIVST group and seven (10.9%) from the HIVFBT group.

Figure 1 Flowchart of different recent infection testing algorithms (RITAs) among HIV infection status among men who have sex with men (MSM) diagnosed as HIV positive in Zhuhai, China. HIVST, HIV self-testing; HIVFBT, facility-based HIV testing; RITA 1, LAg-EIA only; RITA 2, LAg-EIA and CD4+ Tcell count; RITA 3, LAg-EIA and Viral Load; RITAs 4, LAg-EIA, CD4+ T cell count and Viral Load.

Table 2 HIV infection status among MSM diagnosed as HIV positive using different recent infection testing algorithms (RITAs) in Zhuhai, China.

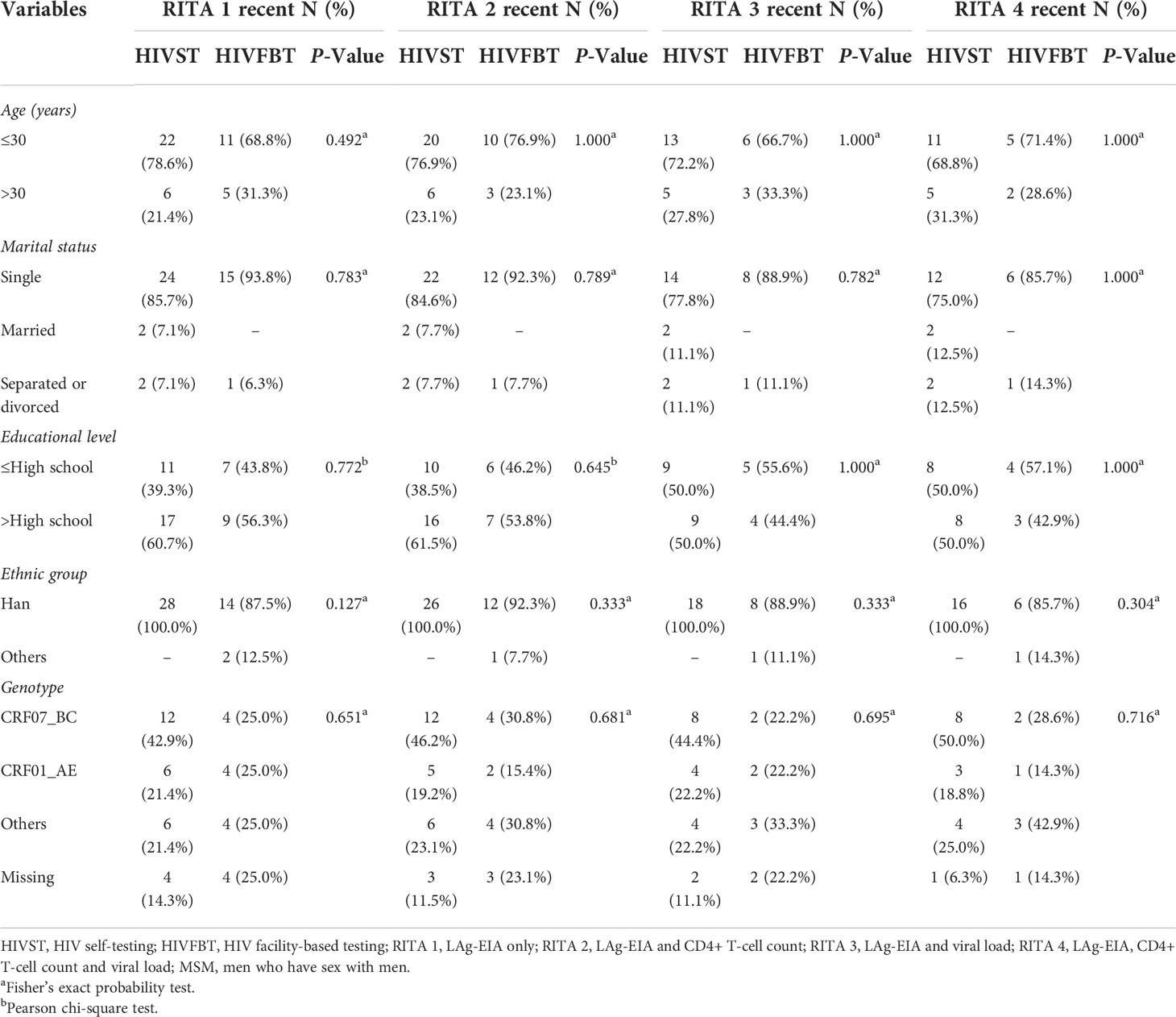

In the RITA subgroups, the sociodemographic characteristics of recent HIV infection cases between the HIVST and HIVFBT groups did not show significant differences (Table 3): more than half of the participants were aged 30 years or under and graduated from high school, and over 80% of the men were single and of Han ethnicity.

Table 3 Sociodemographic characteristics among MSM diagnosed as HIV positive with recency testing results using different recent infection testing algorithms (RITAs) in Zhuhai, China.

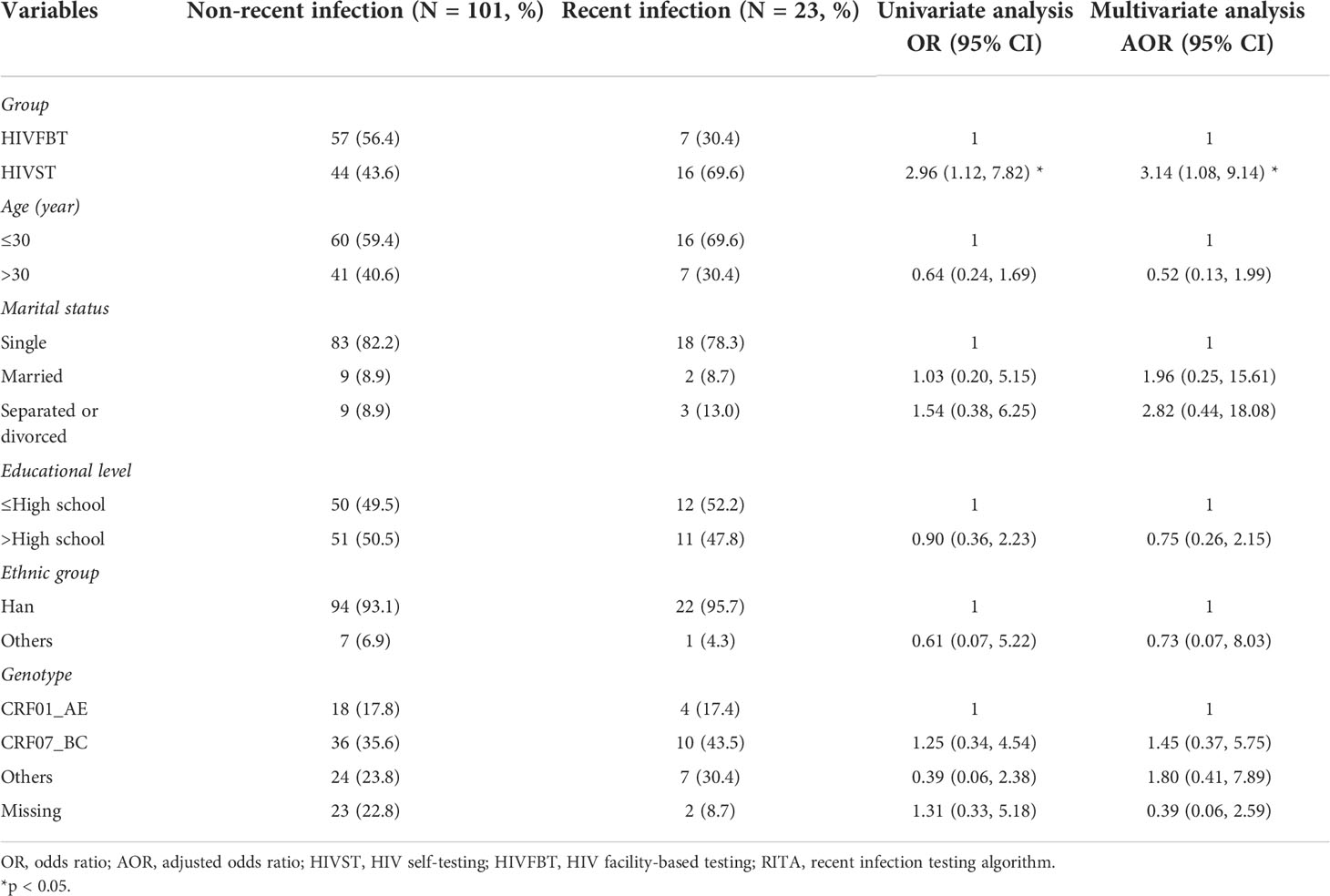

Univariate and multivariate logistic analyses of factors associated with recent HIV infection are presented in Table 4. In the univariate analysis, recent HIV infections were more likely in the HIVST group (odds ratio (OR) 2.96, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.12, 7.82). In the multivariate logistic model, HIVST had a statistically significant association with recent HIV infection (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 3.14, 95% CI 1.08, 9.14).

Table 4 Univariate and multivariate logistic analyses of factors associated with recent HIV infection by RITA 4 (N = 124).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the effectiveness of early detection of HIV infection between HIVST and HIVFBT among MSM in China and the first to compare the HIV genotype differences between HIVST and HIVFBT. This study provided strong evidence of the importance and effectiveness of assessing the early detection of HIV by self-testing. Along with other findings from the same project, the results demonstrated that HIVST expanded the coverage of HIV testing and improved the possibility of identifying new HIV cases in the Chinese MSM sample (18, 21).

From the current study, it has been found that more new HIV infection cases were found via self-testing than HIVFBT. Another study in China using the same RITAs has similar results that HIVST could identify more cases in EHI among MSM than other methods (22, 23). This may be because HIVST enables individuals to perform HIV antibody tests privately (24). Therefore, HIVST overcomes HIV-related stigma and discrimination and has the potential to increase the uptake of testing by reducing the structural barriers associated with clinic attendance (25, 26). Furthermore, normally, self-testing is designed as a rapid and easy-to-operate method like finger stick HIV self-tests. In this way, the time and effort spent traveling and attending a clinic or hospital and the waiting period can be reduced greatly. Although this method may also provide less sensitivity than laboratory-based testing, the period from detectable seroconversion to the first positive screening using self-tests may be shortened, as self-tests could increase testing frequency (27, 28). This is further proved by another study from the same project that HIV self-test kits, which showed an increase not only in case identification among MSM but also in the coverage of HIV testing as HIVST, are an easier way for secondary distribution from target participants (18). Notably, the target participants as sexual health influencers were associated with encouraging more alters with less testing access to self-tests for HIV (29). These results and evidence have demonstrated that HIVST could be a promising approach for increasing the rate of HIV testing in the period of EHI.

Identified cases in EHI in this study mainly occur in younger and better-educated MSM between the HIVST and HIVFBT groups. The same trend was reported in HIV annual reports in China and worldwide (30, 31). In China, young MSM aged 18 to 29 have a higher risk of spreading HIV than heterosexuals of a similar age, and the trend keeps increasing (32–39). In the United States, young MSM aged 20 to 29 were more likely to have “any” sexually transmitted infection, because they were more likely to have HIV-discordant condomless receptive intercourse and avoid disclosing same-sex behavior to healthcare providers or delay HIV/STI diagnosis and treatment (40, 41). These results and evidence have demonstrated that HIVST could be a promising approach to reach more at-risk populations on time.

The current study also assayed the genotypes of EHI cases. The results have discovered similar proportions in the genotypes of the EHI case compared to those in other cities in the same province. For example, the first dominant HIV-1 subtype circulating among MSM in Guangzhou was CRF07_BC (41.6%), followed by CRF01_AE (30.0%), and the same was found in Shenzhen, with CRF07_BC (39.1%) and CRF01_AE (35.1%) being the most predominant (42, 43). HIV-1 subtypes are associated with the pathogenesis and progression of AIDS-defining illness in the infected host (44). A systematic review of the trend of disease progression among HIV-1 different subtypes indicated that HIV-1 genetic diversity did seem to affect the rate of disease progression in ART-naive patient populations (45). Therefore, the similar proportion of subtypes among different cities keeps the comparability on EHI and inspires the possibility of the implementation of future community- and societal-level interventions.

Several limitations have been noticed in this study. Firstly, the results of LAg-EIA are largely affected by ART (World Health Organization, 2018) (9), and although information on receiving ART was not able to be collected in this study, the participants were firstly diagnosed as HIV positive in Zhuhai, and they were less likely to receive ART. Secondly, CD4+ T-cell count or VL testing information was missing for some participants in the HIVFBT group mainly due to a lack of specimens, and thus some cases could not be reclassified. However, the missing data should not greatly influence the chance of a significant difference between the two groups, as the EHI cases were also evaluated by the RITA 4 approach. Thirdly, the limited number of patients included in this study might result in lower statistical power. Finally, this study was a cross-sectional study. Only the associations or differences between the subgroups in a certain period can be reported due to the nature of the study design. Hence, it is hard to provide any direct evidence regarding the causes of EHI.

This study showed that HIVST improved HIV early detection among MSM. Young and better-educated MSM seem more vulnerable to HIV infection than others, but this may be because of more likelihood of using HIVST methods. Compared with HIVFBT, HIVST is more accessible to the most at-risk population on time and tends to identify the case early. Thus, HIVST will be an important promising tool to reach the most at-risk population. Further implementation studies are needed to fill the knowledge gap on this medical service model among MSM and other target populations.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Human Research Ethics Committee of Zhuhai Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

YZ designed the study and wrote the manuscript in collaboration with SLH, MC, and ZG. HT, YF, YW, ZG and MC, YN, YL, FJ, SZH, and JL performed laboratory work and/or data analysis. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study received support from Medical Research Funding of Guangdong Province funds (A2021011).

We appreciate the contributions from all study participants, CBO volunteers, and staff from Zhuhai Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Zhuhai Xutong Voluntary Services Center, and SESH Group.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The editor declared a shared affiliation with the authors, YN and YL, at the time of review.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. World Health Organization. Consolidated HIV strategic information guidelines - executive summary (2020). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/consolidated-hiv-strategic-information-guidelines-executive-summary.

2. UNAIDS. Understanding fast-track: Accelerating action to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030 (2015). Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/201506_JC2743_Understanding_FastTrack_en.pdf.

3. WHO. WHO information note on the use of dual HIV/syphilis rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) (2020). Available at: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/dual-hiv-syphilisdiagnostic-tests/en/.

4. Miller WC, Rosenberg NE, Rutstein SE, Powers KA. Role of acute and early HIV infection in the sexual transmission of HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS (2010) 5(4):277–82. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a0d3a

5. Zun-you wu. The progress. And challenges of promoting HIV/AIDS 90-90-90 strategies in China. Chin J Dis Control Prev (2016) 20(12):1187–9. doi: 10.16462/j.cnki.zhjbkz.2016.12.001

6. Murphy G, Parry JV. Assays for the detection of recent infections with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Euro Surveill (2008) 13(36):18966. doi: 10.2807/ESE.13.36.18966-EN

7. UNAIDS / World Health Organisation. When and how to use assays for recent infection to estimate HIV incidence at a population level (2011). Available at: https://www.who.int/diagnostics_laboratory/hiv_incidence_may13_final.pdf.

8. UNAIDS/WHO. When and how to use assays for recent infection to estimate HIV incidence at a population level (2011). Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44612/9789241501675_eng.pdf?msclkid=6e7ad557cf9111ec8d4ed8ccb3f8e001.

9. UNAIDS. Recent infection testing algorithm technical update: Applications for HIV surveillance and programme monitoring (2018). Available at: https://jointsiwg.unaids.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/infection_testing_algorithm_en.pdf.

10. Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the united states. Jama (2008) 300(5):520–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520

11. Jiang Y, Wang M, Ni M, Duan S, Wang Y, Feng J, et al. HIV-1 incidence estimates using IgG-capture BED-enzyme immunoassay from surveillance sites of injection drug users in three cities of China. Aids (2007) 21 Suppl 8:S47–51. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304696.62508.8a

12. Soodla P, Simmons R, Huik K, Pauskar M, Jõgeda EL, Rajasaar H, et al. HIV Incidence in the Estonian population in 2013 determined using the HIV-1 limiting antigen avidity assay. HIV Med (2018) 19(1):33–41. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12535

13. Mwenge L, Sande L, Mangenah C, Ahmed N, Kanema S, d'Elbée M, et al. Costs of facility-based HIV testing in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe. PloS One (2017) 12(10):e0185740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185740

14. WHO. Guidelines on HIV self-testing and partner notification supplement to consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services (2020). Available at: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/selftesting/hiv-self-testing-guidelines/en/.

15. WHO. Status of HIV self-testing (HIVST) in national policies (situation as of July 2019) (2020). Available at: https://www.who.int/hiv/topics/self-testing/HIVST-policy_map-jul2019-a.png?ua=1.

16. Tang W, Wu. D. Opportunities and challenges for HIV self-testing in China. Lancet HIV (2018) 5(11):e611–2. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3018(18)30244-3

17. Jin X, Xu J, Smith MK, Xiao D, Rapheal ER, Xiu X, et al. An Internet-based self-testing model (Easy test): Cross-sectional survey targeting men who have sex with men who never tested for HIV in 14 provinces of China. J Med Internet Res (2019) 21(5):e11854. doi: 10.2196/11854

18. Wu D, Zhou Y, Yang N, Huang S, He X, Tucker J, et al. Social media-based secondary distribution of human immunodeficiency Virus/Syphilis self-testing among Chinese men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis (2021) 73(7):e2251–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa825

19. Zhou Yi, Liu Y, He Xi, Huang S, Li X, Dai W. Estimation of the population size of men who have sex with men in different venues of zhuhai city. Chin J AIDS STD (2017) 23(08):730–3. doi: 10.13419/j.cnki.aids.2017.08.15

20. Wu D, Zhou Yi, Yang N, Huang S, He Xi, Tucker J, et al. Social media-based secondary distribution of human immunodeficiency Virus/Syphilis self-testing among Chinese men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis (2021) 73(7):e2251–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa825

21. Zhou Y, Wu D, Tang WM, Li XF, Huang SZ, Liu YW, et al. The roles of two HIV self-testing models in promoting HIV-testing among men who have sex with men. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi (2021) 42(2):263–8. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200629-00893

22. Zhu Q, Wang Y, Liu J, Duan X, Chen M, Yang J, et al. Identifying major drivers of incident HIV infection using recent infection testing algorithms (RITAs) to precisely inform targeted prevention. Int J Infect Dis (2020) 101:131–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.1421

23. Johnson CC, Kennedy C, Fonner V, Siegfried N, Figueroa C, Dalal S, et al. Examining the effects of HIV self-testing compared to standard HIV testing services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc (2017) 20(1):21594. doi: 10.7448/ias.20.1.21594

24. Conway DP, Holt M, Couldwell DL, Smith DE, Davies SC, McNulty A, et al. Barriers to HIV testing and characteristics associated with never testing among gay and bisexual men attending sexual health clinics in Sydney. J Int AIDS Soc (2015) 18:20221. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.20221

25. Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Corneli A, Sibeko J, Kamanga G, Rosenberg N, et al. Continued high risk sexual behavior following diagnosis with acute HIV infection in south Africa and Malawi: Implications for prevention. AIDS Behav (2011) 15(6):1243–50. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9839-0

26. Mackellar DA, Hou SI, Whalen CC, Samuelsen K, Sanchez T, Smith A, et al. Reasons for not HIV testing, testing intentions, and potential use of an over-the-counter rapid HIV test in an internet sample of men who have sex with men who have never tested for HIV. Sex Transm Dis (2011) 38(5):419–28. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31820369dd

27. Stekler JD, Ure G, O'Neal JD, Lane A, Swanson F, Maenza J, et al. Performance of determine combo and other point-of-care HIV tests among Seattle MSM. J Clin Virol (2016) 76:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.12.011

28. Witzel TC, Eshun-Wilson I, Jamil MS, Tilouche N, Figueroa C, Johnson CC, et al. Comparing the effects of HIV self-testing to standard HIV testing for key populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med (2020) 18(1):381. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01835-z

29. Yang N, Wu D, Zhou Y, Huang S, He X, Tucker J, et al. Sexual health influencer distribution of HIV/Syphilis self-tests among men who have sex with men in China: Secondary analysis to inform community-based interventions. J Med Internet Res (2021) 23(6):e24303. doi: 10.2196/24303

30. Noble M, Jones AM, Bowles K, DiNenno EA, Tregear SJ. HIV Testing among Internet-using MSM in the United States: Systematic review. AIDS Behav (2017) 21(2):561–75. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1506-7

31. Liu Y, Wu G, Lu R, Ou R, Hu L, Yin Y, et al. Facilitators and barriers associated with uptake of HIV self-testing among men who have sex with men in chongqing, China: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020) 17(5):1634. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051634

32. Jin XM, Chen HC, Sun PY, Zeng ZJ, Yang L, Yang CJ, et al. Performance of limiting-antigen avidity enzyme immunoassay and pooling PCR in detection of recent HIV-1 infection among men who have sex with men in yunnan province. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi (2021) 42(4):706–10. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200605-00810

33. Koblin B, Chesney M, Coates T. Effects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE randomised controlled study. Lancet (2004) 364(9428):41–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16588-4

34. Mustanski BS, Newcomb ME, Du Bois SN, Garcia SC, Grov C. HIV In young men who have sex with men: A review of epidemiology, risk and protective factors, and interventions. J Sex Res (2011) 48(2-3):218–53. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.558645

35. Gangamma R, Slesnick N, Toviessi P, Serovich J. Comparison of HIV risks among gay, lesbian, bisexual and heterosexual homeless youth. J Youth Adolesc (2008) 37(4):456–64. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9171-9

36. China CDC National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention. Progress in prevention and treatment of AIDS in our country. (2012). Available at: http://ncaids.chinacdc.cn/xxgx/yqxx/201804/t20180419_164293.htm.

37. China CDC National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention. 104,000 new cases of HIV infection and patients were reported in China last year (2015). Available at: http://ncaids.chinacdc.cn/xxgx/yqxx/201501/t20150116_109952.htm.

38. Chunxiao P, tong z, Yi X. Epidemiological feature and incidence of HIV among MSM aged between 18-19 in Beijing from 2009 to 2015. Chin J AIDS STD (2020) 26(07):723–8. doi: 10.13419/j.cnki.aids.2020.07.12

39. Halkitis PN, Figueroa RP. Sociodemographic characteristics explain differences in unprotected sexual behavior among young HIV-negative gay, bisexual, and other YMSM in new York city. AIDS Patient Care STDS (2013) 27(3):181–90. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0415

40. Wolitski RJ, Fenton KA. Sexual health, HIV, and sexually transmitted infections among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in the united states. AIDS Behav (2011) 15 Suppl 1:S9–17. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9901-6

41. th Jeffries WL, Greene KM, Paz-Bailey G, McCree DH, Scales L, Dunville R, et al. Determinants of HIV incidence disparities among young and older men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS Behav (2018) 22(7):2199–213. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2088-3

42. Lan Y, He X, Li L, Zhou P, Huang X, Deng X, et al. Complicated genotypes circulating among treatment naïve HIV-1 patients in guangzhou, China. Infect Genet Evol (2021) 87:104673. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104673

43. Zhao J, Chen L, Chaillon A, Zheng C, Cai W, Yang Z, et al. The dynamics of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men (MSM) from 2005 to 2012 in shenzhen, China. Sci Rep (2016) 6:28703. doi: 10.1038/srep28703

44. Jaffar S, Grant AD, Whitworth J, Smith PG, Whittle H. The natural history of HIV-1 and HIV-2 infections in adults in Africa: A literature review. Bull World Health Organ (2004) 82(6):462–9.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, HIV self-testing, facility-based HIV testing, recent infection testing algorithms, RITA

Citation: Zhou Y, Huang S, Cui M, Guo Z, Tang H, Lyu H, Ni Y, Lu Y, Feng Y, Wang Y, Jing F, Huang S, Li J, Xu Y and Mei W (2022) Comparison between HIV self-testing and facility-based HIV testing approach on HIV early detection among men who have sex with men: A cross-sectional study. Front. Immunol. 13:857905. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.857905

Received: 19 January 2022; Accepted: 16 August 2022;

Published: 13 September 2022.

Edited by:

Weiming Tang, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United StatesReviewed by:

Jiegang Huang, Guangxi Medical University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Zhou, Huang, Cui, Guo, Tang, Lyu, Ni, Lu, Feng, Wang, Jing, Huang, Li, Xu and Mei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenhua Mei, NTIzOTY5MzUwQHFxLmNvbQ==; Yao Xu, c2FudG91eHVAZ21haWwuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.