- 1Institute of Medical Microbiology and Hygiene and Research Center for Immunotherapy (FZI), University Medical Center, University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany

- 2Institute of Immunology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany

- 3Institute of Systems Immunology, Hamburg Center for Translational Immunology (HCTI), University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

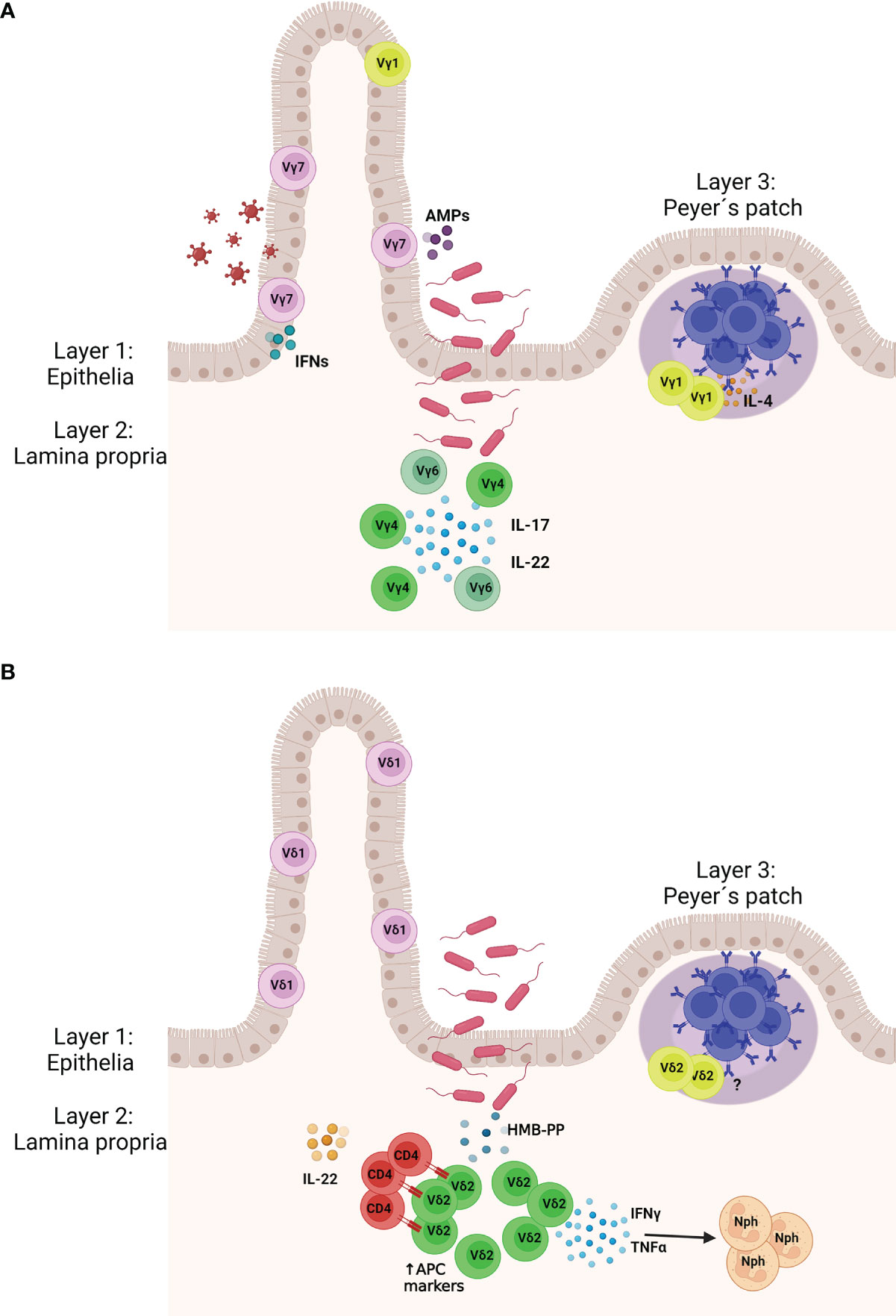

The mucosal surfaces of our body are the main contact site where the immune system encounters non-self molecules from food-derived antigens, pathogens, and symbiotic bacteria. γδ T cells are one of the most abundant populations in the gut. Firstly, they include intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, which screen and maintain the intestinal barrier integrity in close contact with the epithelium. A second layer of intestinal γδ T cells is found among lamina propria lymphocytes (LPL)s. These γδ LPLs are able to produce IL-17 and likely have functional overlap with local Th17 cells and innate lymphoid cells. In addition, a third population of γδ T cells resides within the Peyer´s patches, where it is probably involved in antigen presentation and supports the mucosal humoral immunity. Current obstacles in understanding γδ T cells in the gut include the lack of information on cognate ligands of the γδ TCR and an incomplete understanding of their physiological role. In this review, we summarize and discuss what is known about different subpopulations of γδ T cells in the murine and human gut and we discuss their interactions with the gut microbiota in the context of homeostasis and pathogenic infections.

Introduction

The mucosal immune system represents the first barrier of the body against pathogenic invaders. At the same time, it is responsible for maintaining the symbiotic relationship between the microbiota and the host. Although the microbiota have beneficial functions for the host, they also represent a threat to penetrate the mucosal barrier. Thus, a tight regulation of tissue integrity and a rapid immune response are required (1). The intestinal epithelium consists of only a single layer of epithelial cells that separates the intestinal lumen from the lamina propria (LP), the mucosal tissue situated underneath (Figure 1). The epithelium forms either crypts or villi where water and nutrients are absorbed. To fulfill its multiple functions, the mucosal immune system is composed by extremely heterogeneous populations of leucocytes. Indeed, next to γδ T cells and αβ T cells, the intestinal epithelium and the LP harbor plenty of immune cells including B cells, innate lymphoid cells (ILC)s, macrophages, and dendritic cells (2).

Figure 1 Murine (A) and human (B) γδ T cell protect the gut tissue against pathogens. (Layer 1) γδ IELs patrol the gut epithelia and are interspersed between the epithelial cells. (Layer 2) Upon pathogen invasion lamina propria (LP) γδ T cells expand and produce cytokines to activate the locally the immune system. In mice LP γδ T cells express the Vγ4 and Vγ6 chains and mainly produce IL-22 and IL-17. In humans, LP γδ T cells express the Vδ2 chain and upon stimulation with (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but- 2-enyl pyrophosphate (HMB-PP) produced by bacteria, they release IFN-γ and TNF-α, which attract neutrophils. Vδ2+ γδ T cells may also express markers of antigen presenting cells and present antigen to CD4 T cells, which start producing IL-22. (Layer 3) Specific populations of γδ T cells are found in the Peyer´s patches where they support the humoral immunity, including the production of the immunoglobulin (A) AMPs, antimicrobial peptides; Nph, neutrophil. Created with BioRender.com.

γδ T cells express on the surface a γ and a δ chain, which together form the γδ TCR. They are enriched in the peripheral tissue, but represent only a small percentage of all T cells in the blood (1-5% of total T cells in humans) (3, 4). In mice, γδ T cell subsets are mainly defined by the expression of their γ chain (Heilig and Tonegawa nomenclature) (5), e.g. Vγ1+, Vγ4+, or Vγ7+ γδ T cells; whereas in humans they are grouped according to their δ chain, e.g. Vδ1+ or Vδ2+ γδ T cells. γδ T cells are highly abundant in the gut, where they display diverse phenotypes and functions (6). Among them, γδ intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL)s are localized between the epithelial cells (7, 8) (Figure 1). They are mainly tissue resident (9) and their phenotype is shaped by the local environment (10, 11). Beside γδ IELs, other γδ T cells subsets populate the LP and are termed γδ LPLs. They can re-circulate in the blood or be tissue-resident (10). Finally, Peyer´s patches (PPs) are also home to γδ T cells, in particular to a specific subpopulation important for the humoral response and the production of the immunoglobulin A (IgA) (12, 13) (Figure 1).

In this review, we focus on the different subsets of intestinal γδ T cells, including tissue-resident and circulating populations, which populate the murine and human gut and PPs. We also discuss their interactions with the gut microbiota in the context of homeostasis and pathogenic infections.

First Layer: γδ Intraepithelial Lymphocytes

In this paragraph, we first revisit the functions, origin, and tissue-development of γδ IELs and then discuss their relation to the microbiota at steady state and during infections.

IELs are fundamental for preserving the tissue integrity of the gut, maintaining the symbiosis with the microbiota, and providing continuous surveillance of the intestinal epithelium (14–16).

γδ IELs belong to the natural or type B IELs and express the homodimer CD8αα co-receptor (17). 20% - 30% of human IELs express the γδ TCR; while in mice their frequency makes up to 50% - 60% of all IELs (11, 18). Murine γδ IELs populate the intestine during the perinatal period and mainly express the Vγ7 chain. Although they may appear like an invariant population, their TCR repertoire is still very diverse, endowing them with the potential to recognize a wide array of antigens (6, 19).

It has been suggested that γδ IELs may partially develop extrathymically, as a few γδ IELs still develop in nude mice, which lack a thymus (18, 20). However, it is likely that IEL precursors develop in the thymus before entering the gut (21, 22). Interestingly, intestinal epithelial cells are able to produce IL-7, a cytokine important for intrathymic T cell development (23, 24).

Their recruitment to the intestinal compartment is mediated by the expression of CCR9, which recognize CCL25 produced from intestinal epithelial cells (25, 26) and their accumulation into the epithelium is regulated via binding of integrin αEβ7 (CD103) on IELs with E-cadherin expressed on enterocytes (27). In the epithelia, dietary compounds, such as aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands, and IL-15 produced by epithelial cells, are essential for the maintenance of human and murine γδ IELs (28–33). Importantly, they are locally shaped by specific molecules, the butyrophilin-like (Btnl) subfamily of B7 genes (11, 34). In the gut of mice, Btnl1, expressed by the epithelial cells of the villi, selectively promote the maturation and expansion of Vγ7+ γδ T cells (11) and, together with Btnl6 induce a TCR-dependent stimulation of these cells. Interestingly, different Btnl heterodimers had diverse effects on IELs with different TCRs, indicating that they may fine-tune the IEL numbers, composition, and function in the gut (34).

In humans, the Vδ2− γδ T cell subset is enriched in the intestinal tissue and is also rather heterogeneous (35) (Figure 1B). Similarly to mice, the human gut epithelia express the closely related proteins BTNL3 and BTNL8 which promote the local colonic expansion of a specific Vγ4+ γδ T cell subset (11). Interestingly, during chronic inflammation driven by celiac disease, loss of BTNL8 expression by the gut epithelium was accompanied by the reduction of Vγ4Vδ1+ γδ IELs and by the generation of IFN-γ producing Vδ1+ γδ IELs whose TCR lacked reactivity against BTNL3 and BTNL8 (36). Therefore, also in human the BTNL molecules have a critical role in shaping tissue-resident γδ IELs.

Crosstalk of γδ IELs With the Microbiota

Unexpectedly, the gut microbiota does not influence the number of intestinal γδ IELs, as germ-free (GF) and specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice show comparable numbers of these IELs (18). However, their functions and motility behavior can be conditioned by the microbiota (1). γδ IELs are highly mobile and there is one IEL every ca 5 - 10 epithelial cells (17). IELs patrol the basement membrane by migrating between adjacent epithelial cells, a behavior called “flossing” that has been captured by intravital microscopy using transgenic mice with green fluorescent γδ T cells (9, 11, 17–20). More recently, it has been shown that γδ IELs exhibit a microbiota-dependent localization and movement pattern. Infections of pathogenic bacteria or protozoa induced an active response by γδ IELs, which resulted in increased intraepithelial cell scanning, expression of antimicrobial genes and metabolic switch towards glycolysis (33, 37). These changes were dependent on the pathogen sensing by intraepithelial cells through the MyD88 signaling (33)

This pathway seems to be involved also in the ability of γδ IELs to express several innate antibacterial effectors, including regenerating islet-derived protein 3γ (REG3γ) or chemotactic cytokines in response to a resident bacterial pathobiont, which is able to penetrate into the cells of the host (38) (Figure 1A). In fact, this bacterial stimulation is mediated by intestinal epithelial cells via the activation of MyD88 signaling, indicating that γδ IELs receive microbe-dependent cues directly from epithelial cells (38). Accordingly, the absence of γδ T cells was associated with an increased bacterial burden in Tcrd–/– mice following acute dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced intestinal damage or invasion by other pathogens (39–41). All together, these data reveal a dialogue between the microbiota and γδ IELs, which specifically respond to invading bacteria, both resident (pathobionts) or exogenous (38). Besides bacteria, γδ IELs were shown to protect the intestinal epithelial cells from murine norovirus infections by promoting the antiviral response, dependent on production of type I, II and III IFNs by IELs (32) (Figure 1A). Additionally, activated intestinal IELs increased the resistance of intestinal epithelial cells to viral infection (32). In that study, mice were first treated with anti-CD3 or control antibodies and then orally infected with a norovirus. The level of infection was reduced in mice pre-treated with anti-CD3 antibodies, suggesting that the pre-activation of IELs via TCR engagement enhance the resistance to norovirus infections (32).

Another characteristic of the γδ IELS is that they exist in a so-called “activated yet resting” status (17) describing a chronically activated phenotype (42). They homogeneously express the activation marker CD69, NK cell associated-molecules like 2B4/CD244, NKG2A, NKG2D, NKp46 and NK1.1 (28, 43), and some cytolytic genes such as granzymes A and B, perforin, and Fas ligand, indicating a cytotoxic activity towards pathogens and infected cells as well as potential to trigger apoptosis (29, 30). However, evidence for direct cell lysis by γδ IELs in vivo is still elusive (1, 31).

In summary, there is a coordinated crosstalk between the microbiota, epithelial cells and γδ IELs, which support the maintenance of homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota and the epithelial barrier defense.

Second Layer: Lamina Propria γδ Lymphocytes

LP is a thin layer of connective tissue, which is situated beneath the epithelial cells and contains different γδ T cell populations that are influenced by the microbiota in distinct ways. In contrast to the γδ IELs, which never produce IL-17A, LP-resident γδ T cells can readily produce IL-17 and other “type-3” cytokines (42). Of note, the frequencies of γδ17 T cells in the LP are decreased in GF mice or in mice treated with antibiotics, implying that specific microbiota promote their differentiation or expansion in situ (32). Specifically, signaling through the guanine nucleotide exchange factor VAV1, required in the TCR signal transduction, is essential for the expansion of this pool of LP γδ17 T cells, indicating an involvement of the TCR in the interaction between intestinal microbiota and LP γδ17 T cells (32). In this scenario, macrophages and dendritic cells may produce IL-1 and IL-23, which then induces the production of IL-17 by LP γδ17 T cells (32, 33). These γδ17 T cells share comparable features with Th17 cells, such as the expression of chemokine receptor 6, retinoid orphan receptor (RORγt), AhR, and IL-23 receptor (37, 44, 45). So far, a specific bacterial species that is able to expand LP γδ17 T cells has not been recognized (46). However, their dependency on microbiota could also be indirect via production of IL-10 by Treg cells (47) or regulated by the production of short-chain fatty acids by the microbiota themselves (48).

In mice, a distinct subpopulation of LP γδ T cells accumulate in the intestinal epithelium and associated mesenteric lymph nodes after exposure to Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) (49). These LP γδ T cells appear to be very different from the ones previously described as they form a stable long-lived memory population. They express the Vγ6Vδ1 chains and are able to produce IFN-γ and IL-17 at the same time. Interestingly, they quickly expand after second exposure to oral Lm but not oral Salmonella or intravenous Lm, indicating a specific dependence on Lm, although their TCR ligand is not clear yet (50–52). These findings point to an adaptive-like tissue-specific accumulation of innate γδ17 T cells after bacterial infections.

In addition, in the mouse, the abundance of LP γδ T cells varies along the gastrointestinal tract. In the colon a specific population of γδ17 T cells has been reported to express the Vγ4 chain as well as CCR6 and to be restricted to the innate lymphoid follicles (53).

Finally, besides IL-17, other subsets of LP γδ T cells and innate lymphoid cells type 3 (ILC3) can produce IL-22 (33, 54–56), which controls the release of antimicrobial peptides and enforces tight junctions between enterocytes to limit bacterial dissemination and intestinal inflammation (57, 58).

In humans, 1-5% of the total T cells in the gut are Vγ9/Vδ2 cells (59). Conversely to γδ IELs, LP γδ T cells are recruited from the peripheral blood and proliferate locally in order to preserve the local pool mainly constituted by Vδ2+ cells (7) (Figure 1A). They recognize microbiota- associated metabolites; specifically, they are triggered by phosphoantigens like HMB-PP expressed by bacteria (60–62). Microbe-responsive Vγ9/Vδ2 cells acquire a gut-homing phenotype by increasing the level of the marker CD103, express antigen presenting cells markers and influence the expression of IFN-γ by autologous colonic CD4+ T cells (59) (Figure 1B). In line with this data, Vδ2+ T cell were recruited to the gut and expanded after injection of HMB-PP into macaques (7, 63) (Figure 1B). Moreover, in order to support the mucosal defense, Vγ9/Vδ2 cells activated by bacterial phosphoantigens may recruit neutrophils to the site of invasion, stimulate CD4+ T cells to release IL-22, and promote the production of the IL-22-inducible antimicrobial protein calprotectin by the epithelial cells without affecting the production of IL-17 (64, 65). However, γδ17 T cells are quite abundant in infants and may be involved in the protection of the mucosal barrier during neonatal life (66, 67).

It is worth to mention that γδ17 T cells in other organs can respond to intestinal microbial cues (10, 47, 68, 69) and they have been extensively discussed elsewhere (46).

In summary, conversely to the γδ IELs, LP γδ T cells comprise a big variety of different subpopulations which are very distinct between humans and mice; however, they have a common goal, to support and promote the mucosal immune system in response to invading pathogens.

Third Layer: γδ T Cells In Peyer’s Patches

PPs constitute one of the major components of the mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue and are located along the small intestine. In adult humans, between 100 – 200 PPs can be found in the small intestine (70), whereas mice have approximately 6 – 12 PPs (71). Peyer’s patch formation is profoundly affected by the production of IL-7 from intestinal epithelial cells (24).

Because of a constant stimulation by the nearby microbiota, germinal centers (GCs) in PPs are continuously formed and maturation of high affinity B cells is achieved through somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination, in particular towards the IgA isotype. In fact, IgA is the most abundant antibody of the gut and is mainly secreted by plasma cells generated in the GCs to maintain the homeostasis with the microbiota (72, 73). Our lab recently demonstrated that γδ T cells (mainly Vγ1+ γδ T cells) can be found in PPs and that they localize inside and at the border of the GCs (12). In particular, we showed that a restricted subset of Vγ1+ T cells is able to produce IL-4, thereby inducing B cell isotype switch towards IgA (Figure 1A). Their absence altered the development of IgA+ GC B cells not only at steady state but also in the context of Salmonella infection (12). The influence of Vγ1+ T cells on IgA was also shown at steady state in Vγ1−/− mice, where the concentration of IgA+ B cells was diminished compared to WT mice (74). Also, Tcrd−/− mice presented an even stronger reduction of IgA levels in serum, saliva, and fecal samples after exposure to tetanus and cholera toxin (75). Interestingly, IgM and IgG concentrations were not affected, further corroborating a specific role for PP γδ T cells in the production of IgA (75). These data leave a lot of open questions, in particular regarding the repertoire and the specificities of the γδ TCR. Do Vγ1+ T cells recognize specific signals/antigens via their TCR or does their help rely on other signaling molecules (12)?

Human PPs also harbor a small percentage of γδ T cells, mainly of the Vδ2+ subset, and thus different from the γδ IELs (76) (Figure 1B). Interestingly, a fraction of the PP γδ T cells is CD62L+, probably recruited from the blood while another fraction is CD45R0+ and possibly antigen-primed (76). Weather these γδ T cell subpopulations contribute to the humoral response also in humans is still an open question.

Concluding Remarks

γδ IELs, LP γδ T cells and PP γδ T cells are distinctly shaped by the intestinal microenvironment and by the microbiota. However, how they in turn shape the microbiota and the microenvironment is not completely understood. Further work is necessary to understand the intricate and intriguing interplay between the microbiota, epithelial cells and immune system at local level as well as the effect in other organs. In order to achieve that, careful experimental design should be carried out in order exclude confounding environmental factors and housing conditions (46).

In sum, intestinal γδ T cells act synergistically with the local immune system and epithelial cells to preserve the symbiosis with the gut microbiota and they contribute to the immune responses against invading pathogens directly at three levels: in the epithelial lining, in the LP, and in PPs. Thus, understanding the crosstalk of γδ T cells with the microbiota and identifying the elusive antigens of their TCR in the gut may provide novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of intestinal pathologies.

Author Contributions

FR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. IP wrote sections and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The researchers received funding from Hannover Medical School (HILF I Hochschulinterne Leistungsförderung), number 79228008 (to FR), and from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, grants PR727/11-2, PR727/13-1 and SFB900/project ID158989968 (to IP).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Nielsen MM, Witherden DA, Havran WL. γδ T Cells in Homeostasis and Host Defence of Epithelial Barrier Tissues. Nat Rev Immunol (2017) 17:733–45. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.101

2. Veldhoen M, Brucklacher-Waldert V. Dietary Influences on Intestinal Immunity. Nat Rev Immunol (2012) 12:696–708. doi: 10.1038/nri3299

3. Chien Y, Becker DM, Lindsten T, Okamura M, Cohen DI, Davis MM. A Third Type of Murine T-Cell Receptor Gene. Nature (1984) 312:31–5. doi: 10.1038/312031a0

4. Carding SR, Egan PJ. γδ T Cells: Functional Plasticity and Heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol (2002) 2:336–45. doi: 10.1038/nri797

5. Heilig JS, Tonegawa S. Diversity of Murine Gamma Genes and Expression in Fetal and Adult T Lymphocytes. Nature (1986) 322:836–40. doi: 10.1038/322836a0

6. Takagaki Y, DeCloux A, Bonneville M, Tonegawa S. Diversity of γδ T-Cell Receptors on Murine Intestinal Intraepithelial Lymphocytes. Nature (1989) 339:712–4. doi: 10.1038/339712a0

7. McCarthy NE, Eberl M. Human γδ T-Cell Control of Mucosal Immunity and Inflammation. Front Immunol (2018) 9:985. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00985

8. Goodman T, Lefrançois L. Expression of the γ-δ T-Cell Receptor on Intestinal CD8+ Intraepithelial Lymphocytes. Nature (1988) 333:855–8. doi: 10.1038/333855a0

9. Chennupati V, Worbs T, Liu X, Malinarich FH, Schmitz S, Haas JD, et al. Intra- and Intercompartmental Movement of T Cells: Intestinal Intraepithelial and Peripheral T Cells Represent Exclusive Nonoverlapping Populations With Distinct Migration Characteristics. J Immunol (2010) 185:5160–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001652

10. Khairallah C, Chu TH, Sheridan BS. Tissue Adaptations of Memory and Tissue-Resident Gamma Delta T Cells. Front Immunol (2018) 9:2636. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02636

11. Di Marco Barros R, Roberts NA, Dart RJ, Vantourout P, Jandke A, Nussbaumer O, et al. Epithelia Use Butyrophilin-Like Molecules to Shape Organ-Specific γδ T Cell Compartments. Cell (2016) 167:203–18.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.030

12. Ullrich L, Lueder Y, Juergens A-L, Wilharm A, Barros-Martins J, Bubke A, et al. IL-4-Producing Vγ1+/Vδ6+ γδ T Cells Sustain Germinal Center Reactions in Peyer’s Patches of Mice. Front Immunol (2021) 12:729607. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.729607

13. Rampoldi F, Ullrich L, Prinz I. Revisiting the Interaction of γδ T-Cells and B-Cells. Cells (2020) 9:743. doi: 10.3390/cells9030743

14. Van Kaer L, Olivares-Villagómez D. Development, Homeostasis, and Functions of Intestinal Intraepithelial Lymphocytes. J Immunol (2018) 200:2235–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701704

15. Chen Y, Chou K, Fuchs E, Havran WL, Boismenu R. Protection of the Intestinal Mucosa by Intraepithelial Gamma Delta T Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2002) 99:14338–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212290499

16. Edelblum KL, Sharon G, Singh G, Odenwald MA, Sailer A, Cao S, et al. The Microbiome Activates CD4 T-Cell–Mediated Immunity to Compensate for Increased Intestinal Permeability. Cmgh (2017) 4:285–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.06.001

17. Cheroutre H, Lambolez F, Mucida D. The Light and Dark Sides of Intestinal Intraepithelial Lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol (2011) 11:445–56. doi: 10.1038/nri3007

18. Bandeira A, Mota-Santos T, Itohara S, Degermann S, Heusser C, Tonegawa S, et al. Localization of Gamma/Delta T Cells to the Intestinal Epithelium is Independent of Normal Microbial Colonization. J Exp Med (1990) 172:239–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.239

19. Asarnow DM, Goodman T, LeFrancois L, Allison JP. Distinct Antigen Receptor Repertoires of Two Classes of Murine Epithelium-Associated T Cells. Nature (1989) 341:60–2. doi: 10.1038/341060a0

20. Nonaka S, Naito T, Chen H, Yamamoto M, Moro K, Kiyono H, et al. Intestinal γδ T Cells Develop in Mice Lacking Thymus, All Lymph Nodes, Peyer’s Patches, and Isolated Lymphoid Follicles. J Immunol (2005) 174:1906–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1906

21. Naito T, Shiohara T, Hibi T, Suematsu M, Ishikawa H. Rorγt is Dispensable for the Development of Intestinal Mucosal T Cells. Mucosal Immunol (2008) 1:198–207. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.4

22. Hayday A, Gibbons D. Brokering the Peace: The Origin of Intestinal T Cells. Mucosal Immunol (2008) 1:172–4. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.8

23. Di Santo JP, Rodewald H-R. In Vivo Roles of Receptor Tyrosine Kinases and Cytokine Receptors in Early Thymocyte Development. Curr Opin Immunol (1998) 10:196–207. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(98)80249-5

24. Laky K, Lefrançois L, Lingenheld EG, Ishikawa H, Lewis JM, Olson S, et al. Enterocyte Expression of Interleukin 7 Induces Development of γδ T Cells and Peyer’s Patches. J Exp Med (2000) 191:1569–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1569

25. Wurbel M-A, Malissen M, Guy-Grand D, Meffre E, Nussenzweig MC, Richelme M, et al. Mice Lacking the CCR9 CC-Chemokine Receptor Show a Mild Impairment of Early T- and B-Cell Development and a Reduction in T-Cell Receptor γδ+ Gut Intraepithelial Lymphocytes. Blood (2001) 98:2626–32. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.9.2626

26. Wurbel M-A, Philippe J-M, Nguyen C, Victorero G, Freeman T, Wooding P, et al. The Chemokine TECK is Expressed by Thymic and Intestinal Epithelial Cells and Attracts Double- and Single-Positive Thymocytes Expressing the TECK Receptor CCR9. Eur J Immunol (2000) 30:262–71. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200001)30:1<262::AID-IMMU262>3.0.CO;2-0

27. Schön MP, Arya A, Murphy EA, Adams CM, Strauch UG, Agace WW, et al. Mucosal T Lymphocyte Numbers are Selectively Reduced in Integrin Alpha E (CD103)-Deficient Mice. J Immunol (1999) 162:6641–9.

28. Cibrián D, Sánchez-Madrid F. CD69: From Activation Marker to Metabolic Gatekeeper. Eur J Immunol (2017) 47:946–53. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646837

29. Shires J, Theodoridis E, Hayday AC. Biological Insights Into Tcrγδ+ and Tcrαβ+ Intraepithelial Lymphocytes Provided by Serial Analysis of Gene Expression (SAGE). Immunity (2001) 15:419–34. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00192-3

30. Fahrer AM, Konigshofer Y, Kerr EM, Ghandour G, Mack DH, Davis MM. Chien Y -H. Attributes of Intraepithelial Lymphocytes as Suggested by Their Transcriptional Profile. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2001) 98:10261–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171320798

31. Lefrancois L, Goodman T. In Vivo Modulation of Cytolytic Activity and Thy-1 Expression In TCR-γδ + Intraepithelial Lymphocytes. Sci (80- ) (1989) 243:1716–8. doi: 10.1126/science.2564701

32. Duan J, Chung H, Troy E, Kasper DL. Microbial Colonization Drives Expansion of IL-1 Receptor 1-Expressing and IL-17-Producing γ/δ T Cells. Cell Host Microbe (2010) 7:140–50. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.01.005

33. Sutton CE, Lalor SJ, Sweeney CM, Brereton CF, Lavelle EC, Mills KHG. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 Induce Innate IL-17 Production From ???? T Cells, Amplifying Th17 Responses and Autoimmunity. Immunity (2009) 31:331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.001

34. Jandke A, Melandri D, Monin L, Ushakov DS, Laing AG, Vantourout P, et al. Butyrophilin-Like Proteins Display Combinatorial Diversity in Selecting and Maintaining Signature Intraepithelial γδ T Cell Compartments. Nat Commun (2020) 11:3769. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17557-y

35. Deusch K, Lüling F, Reich K, Classen M, Wagner H, Pfeffer K. A Major Fraction of Human Intraepithelial Lymphocytes Simultaneously Expresses the γ/δ T Cell Receptor, the CD8 Accessory Molecule and Preferentially Uses the Vδ1 Gene Segment. Eur J Immunol (1991) 21:1053–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210429

36. Mayassi T, Ladell K, Gudjonson H, McLaren JE, Shaw DG, Tran MT, et al. Chronic Inflammation Permanently Reshapes Tissue-Resident Immunity in Celiac Disease. Cell (2019) 176:967–981.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.039

37. Martin B, Hirota K, Cua DJ, Stockinger B, Veldhoen M. Interleukin-17-Producing γδ T Cells Selectively Expand in Response to Pathogen Products and Environmental Signals. Immunity (2009) 31:321–30. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.020

38. Ismail AS, Severson KM, Vaishnava S, Behrendt CL, Yu X, Benjamin JL, et al. Gammadelta Intraepithelial Lymphocytes are Essential Mediators of Host-Microbial Homeostasis at the Intestinal Mucosal Surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2011) 108:8743–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019574108

39. Ismail AS, Behrendt CL, Hooper LV. Reciprocal Interactions Between Commensal Bacteria and Gamma Delta Intraepithelial Lymphocytes During Mucosal Injury. J Immunol (2009) 182:3047–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802705

40. Dalton JE, Cruickshank SM, Egan CE, Mears R, Newton DJ, Andrew EM, et al. Intraepithelial γδ+ Lymphocytes Maintain the Integrity of Intestinal Epithelial Tight Junctions in Response to Infection. Gastroenterology (2006) 131:818–29. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.003

41. Edelblum KL, Singh G, Odenwald MA, Lingaraju A, El Bissati K, McLeod R, et al. γδ Intraepithelial Lymphocyte Migration Limits Transepithelial Pathogen Invasion and Systemic Disease in Mice. Gastroenterology (2015) 148:1417–26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.053

42. Malinarich FH, Grabski E, Worbs T, Chennupati V, Haas JD, Schmitz S, et al. Constant TCR Triggering Suggests That the TCR Expressed on Intestinal Intraepithelial γδ T Cells is Functional. vivo Eur J Immunol (2010) 40:3378–88. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040727

43. Mikulak J, Oriolo F, Bruni E, Roberto A, Colombo FS, Villa A, et al. NKp46-Expressing Human Gut-Resident Intraepithelial Vδ1 T Cell Subpopulation Exhibits High Antitumor Activity Against Colorectal Cancer. JCI Insight (2019) 4(24):e125884. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.125884

44. Sutton CE, Lalor SJ, Sweeney CM, Brereton CF, Lavelle EC, Mills KHG. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 Induce Innate IL-17 Production From γδ T Cells, Amplifying Th17 Responses and Autoimmunity. Immunity (2009) 31:331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.001

45. Haas JD, González FHM, Schmitz S, Chennupati V, Föhse L, Kremmer E, et al. CCR6 and NK1.1 Distinguish Between IL-17A and IFN-γ-Producing γδ Effector T Cells. Eur J Immunol (2009) 39:3488–97. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939922

46. Papotto PH, Yilmaz B, Silva-Santos B. Crosstalk Between γδ T Cells and the Microbiota. Nat Microbiol (2021) 6:1110–7. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00948-2

47. Benakis C, Brea D, Caballero S, Faraco G, Moore J, Murphy M, et al. Commensal Microbiota Affects Ischemic Stroke Outcome by Regulating Intestinal γδ T Cells. Nat Med (2016) 22:516–23. doi: 10.1038/nm.4068

48. Dupraz L, Magniez A, Rolhion N, Richard ML, Da Costa G, Touch S, et al. Gut Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids Regulate IL-17 Production by Mouse and Human Intestinal γδ T Cells. Cell Rep (2021) 36(1):109332. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109332

49. Sheridan BS, Romagnoli PA, Pham QM, Fu HH, Alonzo F, Schubert WD, et al. γδ T Cells Exhibit Multifunctional and Protective Memory in Intestinal Tissues. Immunity (2013) 39:184–95. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.015

50. Romagnoli PA, Sheridan BS, Pham Q-M, Lefrançois L, Khanna KM. IL-17A–Producing Resident Memory γδ T Cells Orchestrate the Innate Immune Response to Secondary Oral Listeria Monocytogenes Infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2016) 113:8502–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600713113

51. Murphy AG, O’Keeffe KM, Lalor SJ, Maher BM, Mills KHG, McLoughlin RM. Staphylococcus Aureus Infection of Mice Expands a Population of Memory γδ T Cells That Are Protective Against Subsequent Infection. J Immunol (2014) 192:3697–708. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303420

52. Misiak A, Wilk MM, Raverdeau M, Mills KHG. IL-17–Producing Innate and Pathogen-Specific Tissue Resident Memory γδ T Cells Expand in the Lungs of Bordetella Pertussis –Infected Mice. J Immunol (2017) 198:363–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601024

53. Muzaki ARBM, Soncin I, Setiagani YA, Sheng J, Tetlak P, Karjalainen K, et al. Long-Lived Innate IL-17–Producing γ/δ T Cells Modulate Antimicrobial Epithelial Host Defense in the Colon. J Immunol (2017) 199:3691–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701053

54. Li Y, Innocentin S, Withers DR, Roberts NA, Gallagher AR, Grigorieva EF, et al. Exogenous Stimuli Maintain Intraepithelial Lymphocytes via Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Activation. Cell (2011) 147:629–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.025

55. Sawa S, Lochner M, Satoh-Takayama N, Dulauroy S, Bérard M, Kleinschek M, et al. Rorγt+ Innate Lymphoid Cells Regulate Intestinal Homeostasis by Integrating Negative Signals From the Symbiotic Microbiota. Nat Immunol (2011) 12:320–6. doi: 10.1038/ni.2002

56. Spits H, Di Santo JP. The Expanding Family of Innate Lymphoid Cells: Regulators and Effectors of Immunity and Tissue Remodeling. Nat Immunol (2011) 12:21–7. doi: 10.1038/ni.1962

57. Zheng Y, Valdez PA, Danilenko DM, Hu Y, Sa SM, Gong Q, et al. Interleukin-22 Mediates Early Host Defense Against Attaching and Effacing Bacterial Pathogens. Nat Med (2008) 14:282–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1720

58. Mielke LA, Jones SA, Raverdeau M, Higgs R, Stefanska A, Groom JR, et al. Retinoic Acid Expression Associates With Enhanced IL-22 Production by γδ T Cells and Innate Lymphoid Cells and Attenuation of Intestinal Inflammation. J Exp Med (2013) 210:1117–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121588

59. McCarthy NE, Bashir Z, Vossenkämper A, Hedin CR, Giles EM, Bhattacharjee S, et al. Proinflammatory Vδ2 + T Cells Populate the Human Intestinal Mucosa and Enhance IFN-γ Production by Colonic αβ T Cells. J Immunol (2013) 191:2752–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202959

60. Bukowski JF, Morita CT, Tanaka Y, Bloom BR, Brenner MB, Band H. V Gamma 2V Delta 2 TCR-Dependent Recognition of Non-Peptide Antigens and Daudi Cells Analyzed by TCR Gene Transfer. J Immunol (1995) 154(3):998–1006.

61. Morita CT, Jin C, Sarikonda G, Wang H. Nonpeptide Antigens, Presentation Mechanisms, and Immunological Memory of Human Vγ2vδ2 T Cells: Discriminating Friend From Foe Through the Recognition of Prenyl Pyrophosphate Antigens. Immunol Rev (2007) 215:59–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00479.x

62. Karunakaran MM, Willcox CR, Salim M, Paletta D, Fichtner AS, Noll A, et al. Butyrophilin-2a1 Directly Binds Germline-Encoded Regions of the Vγ9vδ2 TCR and Is Essential for Phosphoantigen Sensing. Immunity (2020) 52:487–498.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.02.014

63. Ryan-Payseur B, Frencher J, Shen L, Chen CY, Huang D, Chen ZW. Multieffector-Functional Immune Responses of HMBPP-Specific Vγ2vδ2 T Cells in Nonhuman Primates Inoculated With Listeria Monocytogenes Δacta prfA *. J Immunol (2012) 189:1285–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200641

64. Tyler CJ, McCarthy NE, Lindsay JO, Stagg AJ, Moser B, Eberl M. Antigen-Presenting Human γδ T Cells Promote Intestinal CD4 + T Cell Expression of IL-22 and Mucosal Release of Calprotectin. J Immunol (2017) 198:3417–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700003

65. Davey MS, Lin C-Y, Roberts GW, Heuston S, Brown AC, Chess JA, et al. Human Neutrophil Clearance of Bacterial Pathogens Triggers Anti-Microbial γδ T Cell Responses in Early Infection. PloS Pathog (2011) 7:e1002040. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002040

66. Chen YS, Chen IB, Pham G, Shao TY, Bangar H, Way SS, et al. IL-17-Producing γδ T Cells Protect Against Clostridium Difficile Infection. J Clin Invest (2020) 130:2377–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI127242

67. Moens E, Brouwer M, Dimova T, Goldman M, Willems F, Vermijlen D. IL-23R and TCR Signaling Drives the Generation of Neonatal V 9v 2 T Cells Expressing High Levels of Cytotoxic Mediators and Producing IFN- and IL-17. J Leukoc Biol (2011) 89:743–52. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0910501

68. Jin C, Lagoudas GK, Zhao C, Bullman S, Bhutkar A, Hu B, et al. Commensal Microbiota Promote Lung Cancer Development via γδ T Cells. Cell (2019) 176:998–1013.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.040

69. Tedesco D, Thapa M, Chin CY, Ge Y, Gong M, Li J, et al. Alterations in Intestinal Microbiota Lead to Production of Interleukin 17 by Intrahepatic γδ T-Cell Receptor–Positive Cells and Pathogenesis of Cholestatic Liver Disease. Gastroenterology (2018) 154:2178–93. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.02.019

70. Cornes JS. Peyer’s Patches in the Human Gut. Proc R Soc Med (1965) 58:716–6. doi: 10.1177/003591576505800930

71. Heel KA, McCauley RD, Papadimitriou JM, Hall JC. REVIEW: Peyer’s Patches. J Gastroenterol Hepatol (1997) 12:122–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00395.x

72. Macpherson AJ, Geuking MB, Slack E, Hapfelmeier S, McCoy KD. The Habitat, Double Life, Citizenship, and Forgetfulness of IgA. Immunol Rev (2012) 245:132–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01072.x

73. Cerutti A, Chen K, Chorny A. Immunoglobulin Responses at the Mucosal Interface. Annu Rev Immunol (2011) 29:273–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101317

74. Huang Y, Heiser RA, Detanico TO, Getahun A, Kirchenbaum GA, Casper TL, et al. γδ T Cells Affect IL-4 Production and B-Cell Tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2015) 112:E39–48. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415107111

75. Fujihashi K, McGhee JR, Kweon MN, Cooper MD, Tonegawa S, Takahashi I, et al. Gamma/Delta T Cell-Deficient Mice Have Impaired Mucosal Immunoglobulin A Responses. J Exp Med (1996) 183:1929–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1929

Keywords: gut epithelia, lamina propria (LP), γδ T cells, IEL intra-epithelial lymphocyte, Peyer’s patch

Citation: Rampoldi F and Prinz I (2022) Three Layers of Intestinal γδ T Cells Talk Different Languages With the Microbiota. Front. Immunol. 13:849954. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.849954

Received: 06 January 2022; Accepted: 01 March 2022;

Published: 29 March 2022.

Edited by:

Oliver Pabst, Uniklinik RWTH Aachen, GermanyReviewed by:

Brian S. Sheridan, Stony Brook University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Rampoldi and Prinz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Francesca Rampoldi, cmFtcG9sZnJAdW5pLW1haW56LmRl

Francesca Rampoldi

Francesca Rampoldi Immo Prinz2,3

Immo Prinz2,3