- College of Animal Science, Zhejiang University, The Key Laboratory of Molecular Animal Nutrition, Ministry of Education, Hangzhou, China

Wild pigs usually showed high tolerance and resistance to several diseases in the wild environment, suggesting that the gut bacteria of wild pigs could be a good source for discovering potential probiotic strains. In our study, wild pig feces were sequenced and showed a higher relative abundance of the genus Lactobacillus (43.61% vs. 2.01%) than that in the domestic pig. A total of 11 lactic acid bacteria (LAB) strains including two L. rhamnosus, six L. mucosae, one L. fermentum, one L. delbrueckii, and one Enterococcus faecalis species were isolated. To investigate the synergistic effects of mixed probiotics strains, the mixture of 11 LAB strains from an intestinal ecology system was orally administrated in mice for 3 weeks, then the mice were challenged with Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 (2 × 109 CFU) and euthanized after challenge. Mice administrated with LAB strains showed higher (p < 0.05) LAB counts in feces and ileum. Moreover, alterations of specific bacterial genera occurred, including the higher (p < 0.05) relative abundance of Butyricicoccus and Clostridium IV and the lower (p < 0.05) abundance of Enterorhabdus in mice fed with mixed LAB strains. Mice challenged with Escherichia coli showed vacuolization of the liver, lower GSH in serum, and lower villus to the crypt proportion and Claudin-3 level in the gut. In contrast, administration of mixed LAB strains attenuated inflammation of the liver and gut, especially the lowered IL-6 and IL-1β levels (p < 0.05) in the gut. Our study highlighted the importance of gut bacterial diversity and the immunomodulation effects of LAB strains mixture from wild pig in gut health.

1 Introduction

Homeostasis of gut health, together with the diverse and complex microbial community harbored in the gut, plays a central role in host health (1). Disorder of gut health, including the alteration of gut microbiota, impairment of barrier function, and disruption of the immune system, further lead to several diseases of the host (2). Supplementation of probiotics has been revealed as one of the effective strategies to maintain the gut health (3). According to the definition, probiotics are “living microorganisms that confer several health benefits when administrated in adequate amounts to the host” (4). Most often used as probiotic supplements, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) include many bacterial genera, including Lactobacilli, Lactococci, Enterococci, Streptococci, Leuconostoc, and Pediococci, among which the best known is the genus Lactobacillus (5). Numerous studies have revealed the beneficial effect in applying LAB, with the mechanisms behind including suppression of pathogens, manipulation of microbiota communities, immunomodulation, stimulation of epithelial cell proliferation, and differentiation and fortification of the gut barrier (6).

Isolation and characterization of bacterial strains was the first step in the discovery and application of probiotics. As the gut is one of the sources for probiotic strains, probiotics such as L. gasseri, L. reuteri, and L. fermentum isolated from the human gut exert therapeutic and protective activities (7). However, imbalance in the gut microbiota usually occurs in humans with industrialized lifestyles, following a rise in diseases such as allergic and autoimmune disorders, and inflammatory bowel disease, indicating the importance of preserving the treasure of microbial diversity from rural communities (8). On the other hand, the gut of pigs is also suggested as a good source of probiotics (9). In our previous study, probiotic strain L. reuteri ZJ617 was isolated from the domestic pig intestine and showed high adhesive ability together with inhibition activity against pathogens including Escherichia coli K88 and Salmonella enteritidis 50335 (10). Compared with the domestic pig fed with a commercial diet, wild pigs live in a wild environment mainly fed on a diet that includes acorns, wild fruits, grassroots, and stems with high cellulose content and low carbohydrate or fat content (11). It has been previously reported that a strong distinction existed in the bacterial diversity of wild pigs and domestic pigs. What is more, predictions of metagenome function showed more bacterial genes related to the immune system and environmental adaptation in the feces of wild pigs than that in domestic pigs (12). To investigate the probiotics in wild pigs, Li and colleagues assessed the probiotic characteristics and safety properties of LAB strains isolated from the gut, including L. mucosae, L. salivarius, Enterococcus hirae, Enterococcus durans, and Enterococcus faecium (13). Previous studies have suggested the beneficial effects of probiotics in the gut of wild pigs, while few studies demonstrated the mechanism behind applying probiotics strains in gut health. On the other hand, although beneficial effects of single-strain probiotics to health were revealed in numerous studies, the potential of synergistic effects from mixed probiotics strains is still not fully explored (14).

In this study, we sequenced and isolated LAB strains from the feces of a wild pig, following administrated LAB strain mixture in mice challenged with E. coli, aiming to investigate the synergistic effects of probiotic strains and illustrate the mechanisms in the contribution to gut health.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Animals and Fecal Collection

In this study, one adult WP weighting 100 kg from a wild environment and three adult DP (Duroc × Landrace × Yorkshire) with similar weights were selected. Fecal pellets were collected and stored at -80°C immediately with 20% glycerol for further analysis.

2.2 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing

Amplicon sequencing of the 16S RNA was performed by Realbio Genomics Institute (Shanghai, China). Briefly, DNA was extracted and the V3–V4 region was amplified in PCR reactions using primers 341F: 5′-CCTACGGGRSGCAGCAG-3′ and 806R: 5′-GGACTACVVGGGTATCTAATC-3′ and sequenced on a HiSeq platform (Illumina Inc., CA, USA) for paired-end reads of 250 bp. Reads were clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) with 97% similarity (15) and classified with RDP Classifier (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/). QIIME1 (v1.9.1) was used in the OTU profiling and alpha/beta diversity analyses. All DNA sequences in this study were deposited in the NCBI sequence read archive with the project number PRJNA778598.

2.3 Isolation and Characterization of LAB Strains

2.3.1 Isolation of LAB Strains

LAB strains were isolated according to methods described in a previous study (10). Briefly, feces from WP was suspended, homogenized, and spread on de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) agar (Qingdao Haibo Bio, China) plates and incubated anaerobically. After incubation, the white colony of LAB was streaked onto MRS agar plates again and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Samples from LAB medium plates were transferred to a tube containing 10 ml MRS broth and preserved at -80°C with a dilution of 40% (w/v) sterile glycerol for further use.

2.3.2 Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis of LAB

DNA of the LAB strains was extracted, and full lengths of 16S rRNA genes were amplified with the following primers: forward 5′-A GAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ and reverse 5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′ (16). The PCR products were sequenced (Shangya Biotechnology, Hangzhou, China), and sequences were compared with the sequences available in the NCBI of BLAST program (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Phylogenetic tree analysis was achieved with MEGA 7.0 (http://megasoftware.net/). Sequences were submitted in GenBank, and the name and accession numbers (MT12247, MT712248, MT712249-MT712254, MT712255, MT712256, MT712257) are obtained.

2.3.3 Characterization of LAB Strains

LAB strains were characterized according to the procedures in a previous study (10). Briefly, bacterial culture inoculated into MRS broth was measured for the growth curve in 0, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, and 24 h. Auto-aggregation assay (17) was applied, and absorbance of the supernatant was measured to determine the specific cell–cell interactions. In terms of cell surface hydrophobicity, xylene was added to the cell suspension and the aqueous phase was measured. All the absorbance of bacterial culture, supernatant, and aqueous phase was measured for each time at 600 nm using a BioTek Synergy HTX multi-mode reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Acid and bile salt survivability of the LAB was assessed in the MRS broths with pH = 3.0 or 0.1% bile salt. Viable bacterial counts were determined by plating appropriate dilutions on MRS agar medium. For the tolerance of Cu2+ and Zn2+, MRS mediums were prepared with 100 mg/L or without Cu2+/Zn2+ and inoculated with 2% of culture and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Optical density at OD 600 nm was measured for monitoring the growth kinetics. The above tests were carried out in triplicate for each strain.

2.4 Oral Administration of LAB and Sample Collection in Mouse Study

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang University (No. 20170529). In this study, a total of 36 male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and fed with chow diet ad libitum. Mice were housed in a quiet and ventilated environment at 25°C, 50% humidity, and 12-h light–dark cycle.

As shown in Figure S1A, mice were randomly divided into four groups of nine mice each. Four groups were treated as follows: (1) mice orally administrated with 200 μl of PBS for 3 weeks (C); (2) mice orally administrated with 200 μl of PBS for 3 weeks followed by oral challenge with E. coli ATCC 25922 (18) as gut inflammatory model (2 × 109 CFU) (CE); (3) mice orally administrated with mixed LAB (2 × 109 CFU) for 3 weeks (M); and (4) mice orally administrated with mixed LAB (2 × 109 CFU) for 3 weeks followed by oral challenge with E. coli ATCC 25922 (2 × 109 CFU) (ME), respectively. The body weight of all mice was recorded daily, and feces of all mice was collected aseptically and suspended into sterile saline to determine viable LAB counts. At the endpoint, the body temperature of each mouse was measured, and blood and fecal samples were collected before euthanasia. Viable LAB that adhered in the jejunum and ileum epithelium were counted by plating appropriate dilutions on MRS agar medium.

2.5 Biochemical Assays of Serum

The concentrations of T-AOC, SOD, GSH, DAO, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in the serum were determined with commercially available ELISA kits according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institution).

2.6 Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining of Liver and Gut

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of liver and gut tissues was performed as previously described (19). In brief, samples from the liver, ileum, and colon were soaked in 4% paraformaldehyde, waxed, and sliced into 5 µm-thick sections. After deparaffinization and dehydration, sections were soaked in graded alcohols and stained with H&E subsequently. Photomicrographs were obtained via optical microscopy, and crypt length was measured using Imaging Software (CS-EN-V1.18) (Olympus Corporation).

2.7 Western Blotting

Bradford’s method was applied in the determination of protein concentration in samples (20). Protein samples were loaded on sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. The primary antibody was applied to incubate and block the membrane at 4°C overnight. The blot was developed with electrochemiluminescence (Millipore) after incubation with the secondary antibody. Bands were measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) and standardized to the density of GAPDH.

2.8 Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis (qRT-PCR) of mRNA from the gut was performed with TB Green Premix Ex Taq (Tiangen Biotech) according to the instructions. The sequences for PCR primers were as follows: GAPDH (5′-CGCGAGAAGATGACCCAGAT-3′, 5′-GCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAGG-3′); TNF-α (5′-CGTTGTAGCCAATGTCAAAGCC-3′, 5′-TGCCCAGATTCAGCAAAGTCCA-3′); IL-1β (5′-TCTTTGAAGTTGACGGACCC-3′, 5′-TGAGTGATACTGCCTGCCTG-3′); IL-6 (5′-GCTACCAAACTGGATATAATCAGGA-3′, 5′-CCAGGTAGCTATGGTACTCCAGAA-3′). The data obtained were analyzed using the Mx3000P system (Agilent), and β-actin was used as internal standard in all gene quantifications performed. The final data were derived from the formula 2-ΔΔCt.

2.9 Gut Microbiota Profiling

The 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing of fecal samples in mice was performed. The detailed procedures were described in Section 2.2.

2.10 Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA, and two-way ANOVA were applied in the comparison of two groups, bacterial strains, and four groups, respectively. For the abundance of gut microbiota, Kruskal–Wallis H test and Dunn’s post hoc test were carried out on the comparison among four groups. Analysis of similarities (Anosim) was applied for the beta diversity of gut microbiota between four groups. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) was used to the detect the differential microbiota at the genus level, and the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score of each microbiota was given. In each case, p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analysis of the dataset was completed with R software (version 3.5.1).

3 Results

3.1 Isolation and Identification of LAB Strains From Wild Pig

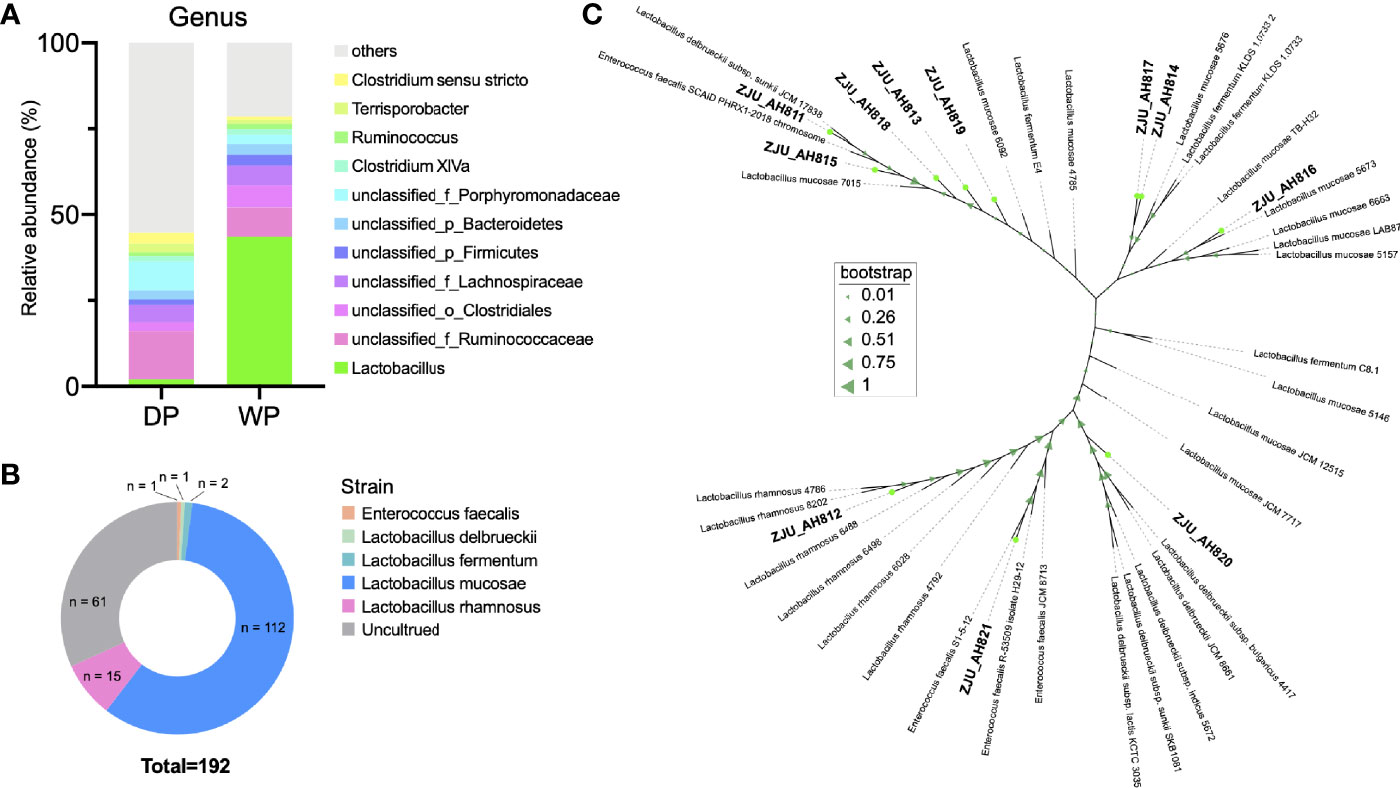

Results of 16S rRNA gene sequencing (Figure 1A and Table S1) revealed high relative abundance of Lactobacillus in feces of WP (43.61%) than that in DP (2.01%). When LAB strains from WP were isolated and cultured (Figure 1B), a total of 112, 15, 2, 1, and 1 strains were classified as L. mucosae, L. rhamnosus, L. fermentum, L. delbrueckii, and Enterococcus faecalis within the 192 cultures, respectively. According to the threshold of 97% similarity, 11 LAB strains were identified, namely, ZJU_AH811, ZJU_AH812, ZJU_AH813, ZJU_AH814, ZJU_AH815, ZJU_AH816, ZJU_ AH817, ZJU_AH818, ZJU_AH819, ZJU_AH820, and ZJU_AH821. As shown in Figure 1C, a phylogenetic tree of 11 LAB strains with reference sequences from NCBI was constructed. Within the 11 LAB strains, ZJU_AH811 and ZJU_AH812 belong to L. rhamnosus, ZJU_AH819 belongs to L. fermentum, ZJU_AH820 belongs to L. delbrueckii, ZJU_AH821 belongs to Enterococcus faecalis, and the rest of the 6 strains belong to L. mucosae.

Figure 1 Isolation and identification of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) strains. (A) Relative abundance (>1%) of gut microbiota at the genus level between domestic pig (DP) and wild pig (WP). (B) Proportion of the cultured LAB strains isolated from WP. (C) Phylogenetic tree of 11 LAB strains with similarity < 97% (ZJU_AH811, ZJU_AH812, ZJU_AH813, ZJU_AH814, ZJU_AH815, ZJU_AH816, ZJU_AH817, ZJU_AH818, ZJU_AH819, ZJU_AH820, ZJU_AH821) and reference sequences from NCBI.

3.2 Characteristics of LAB Strains

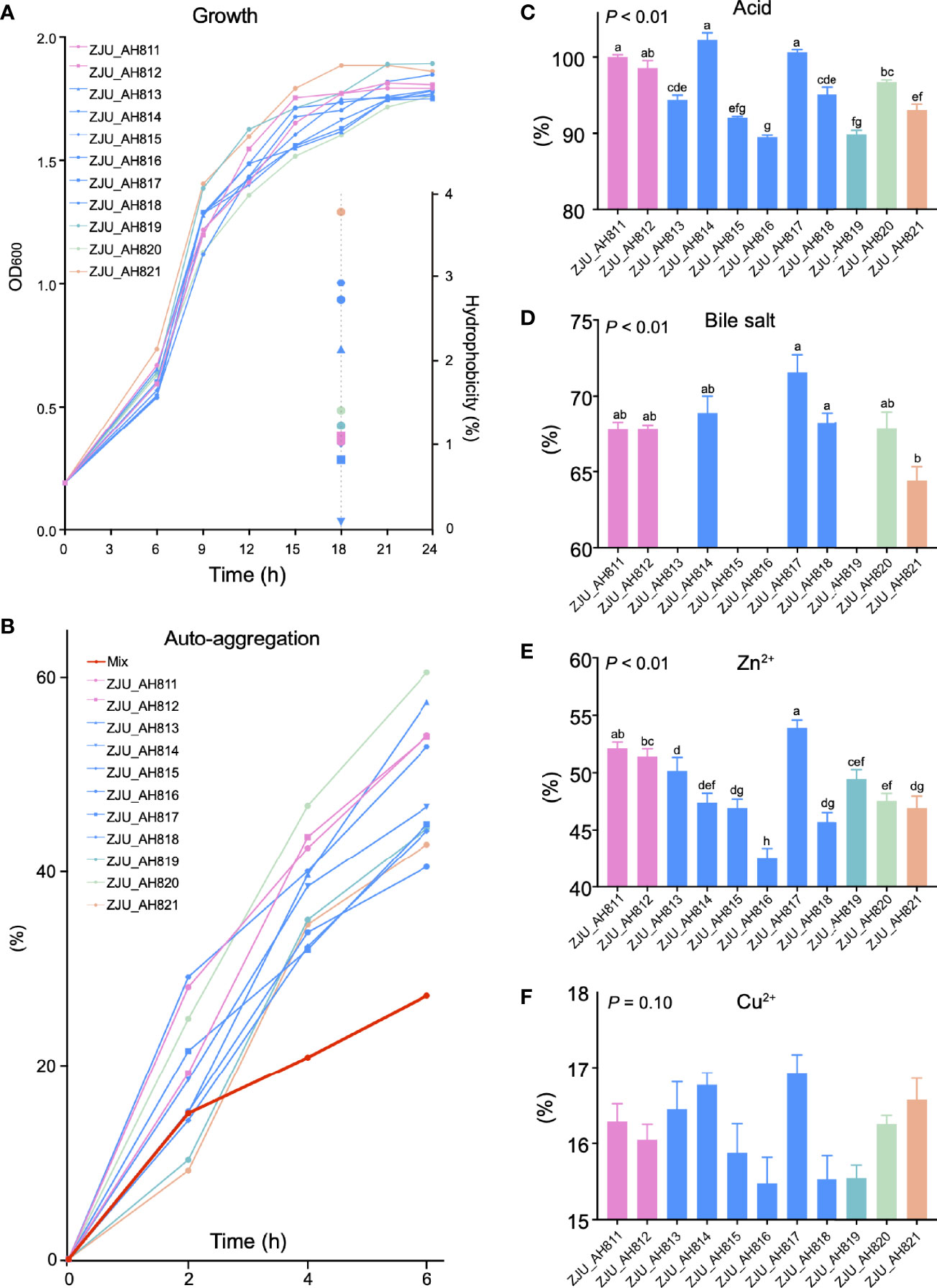

As the LAB strains were isolated and identified from WP, the growth kinetics of the 11 LAB strains were evaluated (Figure 2A). After 24 h, ZJU_AH819 and ZJU_AH817 showed the highest growth rate value indicated as OD600 nm values, respectively. The hydrophobicity of LAB strains was tested at 18 h (Figure 2A), and ZJU_AH821 and ZJU_AH814 showed the highest (3.76%) and lowest (0.08%) hydrophobicity among the 11 LAB strains. The auto-aggregation curves within 6 h of 11 LAB strains alone or mixed were generated (Figure 2B), which ranged from 60.54% to 27.24%. The mixed LAB strains showed the lowest auto-aggregation than 11 LAB strains alone. All the 11 LAB strains tested showed tolerance to acid (pH = 3), and the survival rate of LAB strains was between 102.25 ± 0.95% and 89.48 ± 0.32% after 3 h of exposure to acid (Figure 2C, p < 0.01). The survivability in 0.3% bile salt was examined (Figure 2D, p < 0.01), and seven LAB strains were able to survive with a survival rate ranging from 64.43 ± 0.92% to 71.58 ± 1.13% after a 3-h exposure, including ZJU_AH811, ZJU_AH812, ZJU_AH814, ZJU_AH817, ZJU_AH818, ZJU_AH820, and ZJU_AH821. The results of the LAB strains’ tolerance to 100 mg/l Zn2+ or Cu2+ are shown in Figures 2E, F. The LAB strains ZJU_AH817 and ZJU_AH816 showed the highest (53.93%) and the lowest (42.57%) tolerance to Zn2+ after 24 h, respectively. The tolerance of Cu2+ showed no significant difference between 11 LAB strains (p = 0.01).

Figure 2 Characteristics of LAB strains. Growth curve and hydrophobicity (A), and auto-aggregation (B) of single and mixed of 11 LAB strains. Tolerance of (C) acid, (D) bile acid, (E) Zn2+, and (F) Cu2+ of 11 LAB strains (ZJU_AH811, ZJU_AH812, ZJU_AH813, ZJU_AH814, ZJU_AH815, ZJU_AH816, ZJU_AH817, ZJU_AH818, ZJU_AH819, ZJU_AH820, ZJU_AH821). Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Letters a-h in the same graphic were significantly different (p < 0.05).

3.3 Adherence of Mixed LAB Strains in the Gut and Composition of Gut Microbiota in Mice

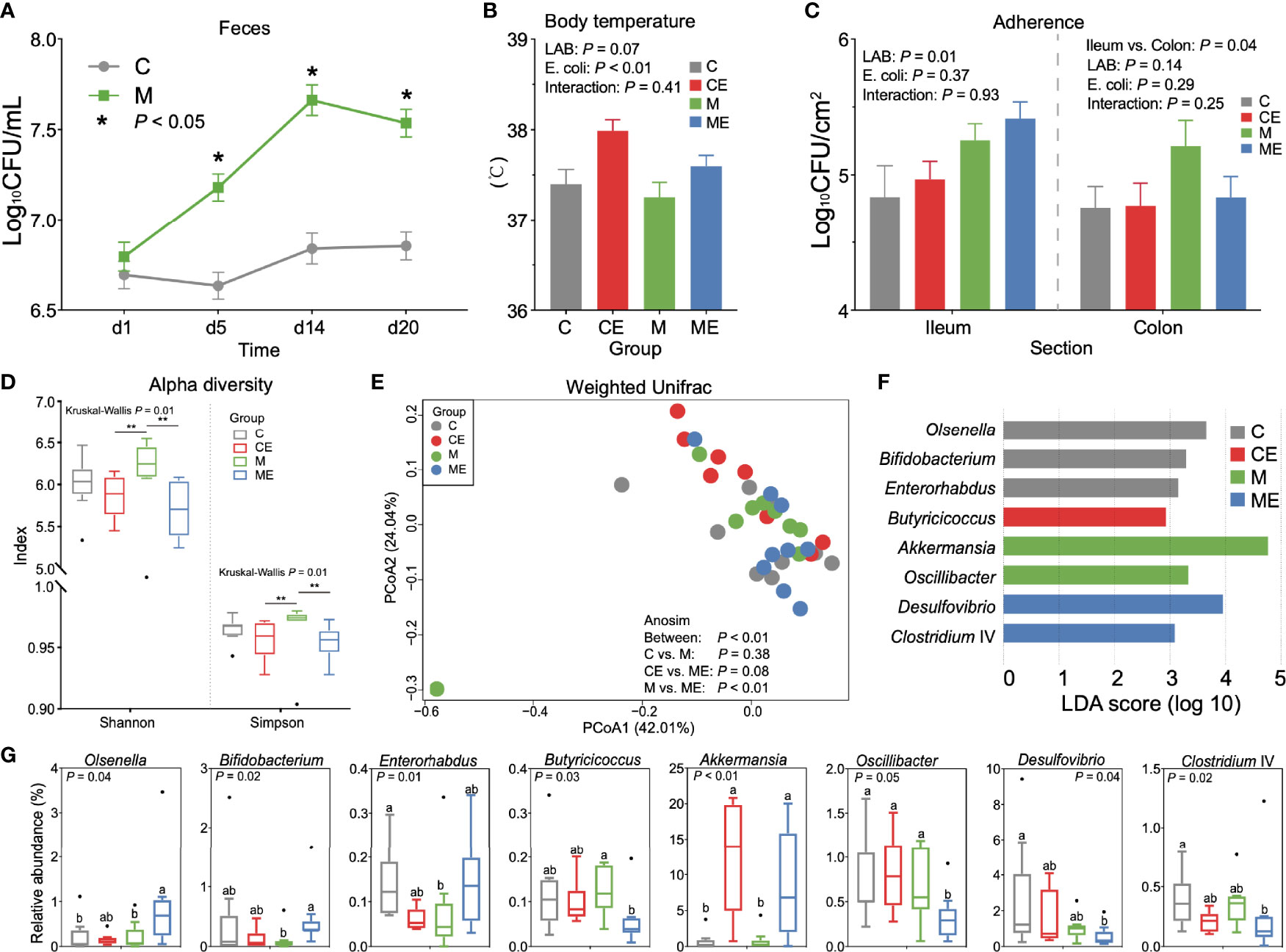

In mice fed with a mixture of 11 LAB strains, feces were collected and cultured to test the viable count of entire LAB in the gut. As shown in Figure 3A, the LAB counts in mice fed with mixed LAB strains (M) were 7.18 ± 0.30, 7.66 ± 0.35, and 7.54 ± 0.32 Log10 CFU/ml and were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than 6.63 ± 0.29, 6.84 ± 0.35, and 6.85 ± 0.31 Log10 CFU/ml in the control group (C) at days 5, 14, and 20, respectively. During the study, no significant of feed intake, weight gain, or feed-to-gain ratio was observed between C and M mice (Figure S1B). As shown in Figure 3B, the challenge with E. coli showed a significant effect (p < 0.01) on body temperature, while the administration of mixed LAB strains (p = 0.07) showed a decreasing trend in the body temperature, and the interaction between mixed LAB strains and E. coli showed no significant effect (p = 0.41) on the body temperature in mice. As shown in Figure 3C, administration of mixed LAB strains showed a significant effect on the counting number of LAB in the ileum (p < 0.01) than that in control mice. The challenge of E. coli and the interaction between mixed LAB strains showed no effect on the counting number of LAB both in the ileum and colon.

Figure 3 Gut microbiota profiles in mice fed with mixed LAB strains and challenged with Escherichia coli. (A) Counts of LAB in feces of mice fed with mixed LAB strains (M) and control group (C) at days 1, 5, 14, and 20. (B) Body temperature of control mice (C), control mice challenged with Escherichia coli (CE), mice fed mixed LAB strains (M), and mice fed mixed LAB strains and challenged with Escherichia coli (ME) at the end point. (C) Adherence of LAB in the ileum and colon of mice between C, CE, M, and ME groups. (D) Alpha diversity (Shannon and Simpson index) of gut microbiota in mice between C, CE, M, and ME groups. (E) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) on the weighted UniFrac distance matrix of gut microbiota between C, CE, M, and ME groups. (F) Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score of gut microbiota (with LDA score > 2) at the genus level between C, CE, M, and ME groups. (G) Relative abundance of bacteria genera with LDA score > 2 between C, CE, M, and ME groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Letters a,b in the same graphic were significantly different (p < 0.05).

When fecal samples were sequenced, significant differences (p = 0.01) of the Shannon and Simpson indices were observed between four groups (Figure 3D). Mice fed mixed LAB strains showed both higher Shannon and Simpson indices in the gut microbiota than did CE and ME mice. The PCoA analysis based on the weight UniFrac distance matrix of the gut microbiota revealed the beta diversity in C, CE, M, and ME mice (Figure 3E). Analysis of similarities (Anosim) showed no significant difference between the C and M (p = 0.38) or CE and ME (p = 0.08) group while the profiles of gut microbiota in M and ME mice showed a significant difference (p < 0.01). The relative abundance of gut microbiota between C, CE, M, and ME groups at the phylum and genus levels is shown in Tables S2, S3. LEfSe analysis revealed 8 differential genera (LDA score > 2, Figure 3F), and the relative abundance of differential genera between four groups is shown in Figure 3G, including Olsenella, Bifidobacterium, Enterorhabdus, Butyricicoccus, Akkermansia, Oscillibacter, Desulfovibrio, and Clostridium IV. When mice were challenged with E. coli, higher (p < 0.01) abundance of Akkermansia was observed in the CE and ME group than in the C and M group. Mice fed with mixed LAB strains challenged the lower (p = 0.05) relative abundance of Oscillibacter in the gut than did other groups.

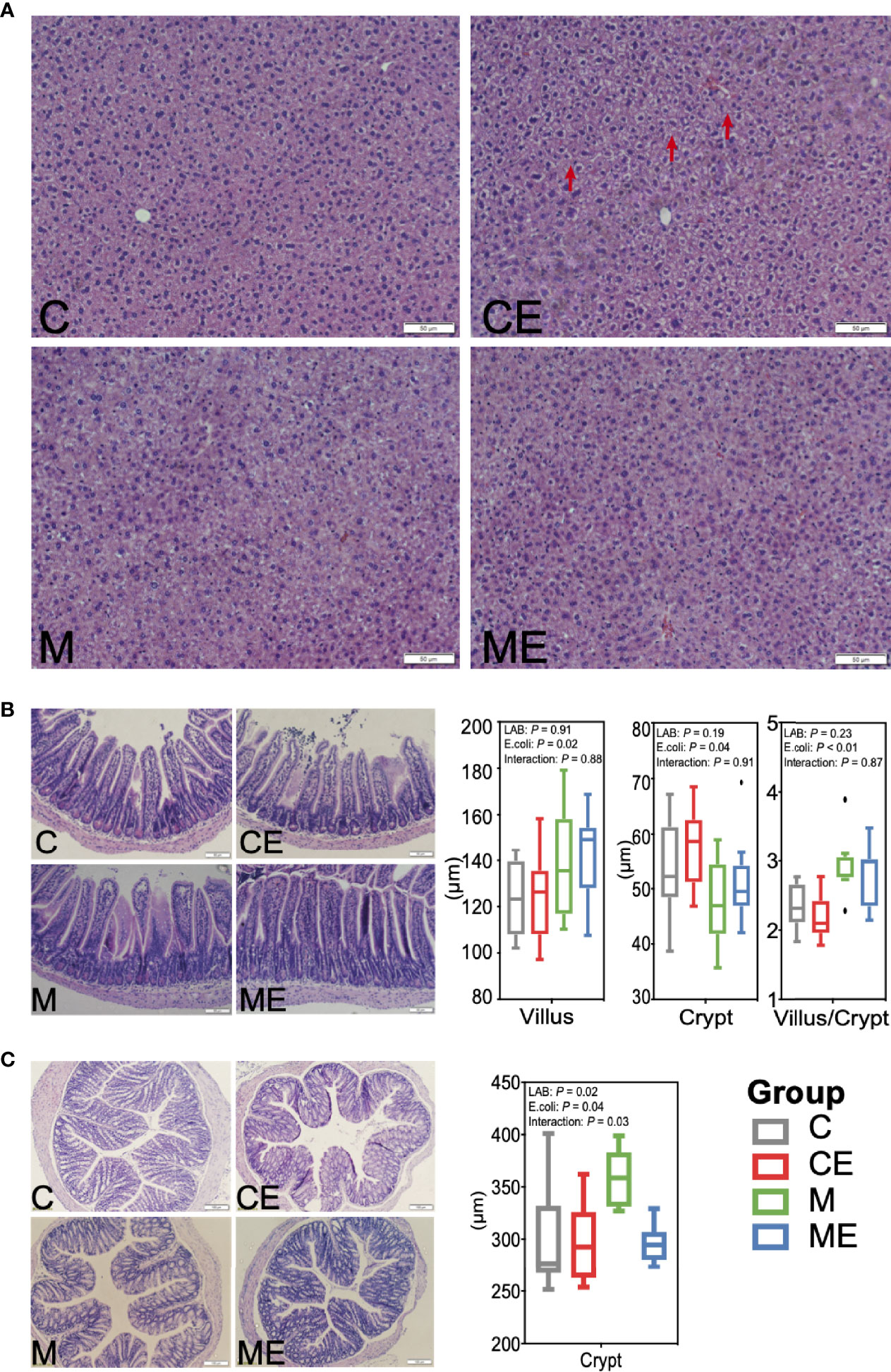

3.4 Alleviation of Liver and Gut Morphology in Mice Fed Mixed LAB Strains and Challenged With E. coli

H&E staining revealed hepatic vacuolization in CE mice challenged with E. coli, while administration of mixed LAB strains attenuated the vacuolization in ME mice (Figure 4A). Morphology of the ileum and colon in C, CE, M, and ME mice was also assessed and is shown in Figures 4B, C. Administration of mixed LAB strains showed no effect on the villus length (p = 0.91) and crypt depth (p = 0.19) while challenge with E. coli significantly increased the villus length (p = 0.02) and crypt depth (p = 0.04), and no interaction between LAB and E. coli was observed (Figures 4B, C). In addition, a lower (p < 0.01) proportion of villus to crypt in mice challenged with E. coli was observed (Figure 4B). In the colon, both LAB (p = 0.02) and E. coli (p = 0.04) showed a significant effect on the crypt depth. Mice administrated with mixed LAB strains showed the highest crypt depth (358.21 µm) than other C (299.73 µm), CE (298.10 µm), and ME (295.74 µm) mice. The interaction between LAB and E. coli (p = 0.03) was also observed (Figure 4C).

Figure 4 Morphology of the (A) liver, (B) ileum, and (C) colon in control mice (C), control mice challenged with Escherichia coli (CE), mice fed mixed LAB strains (M), and mice fed mixed LAB strains and challenged with Escherichia coli (ME) at the end point.

3.5 Effects of Mixed LAB Strains in the Inflammation of Serum and Gut in Mice

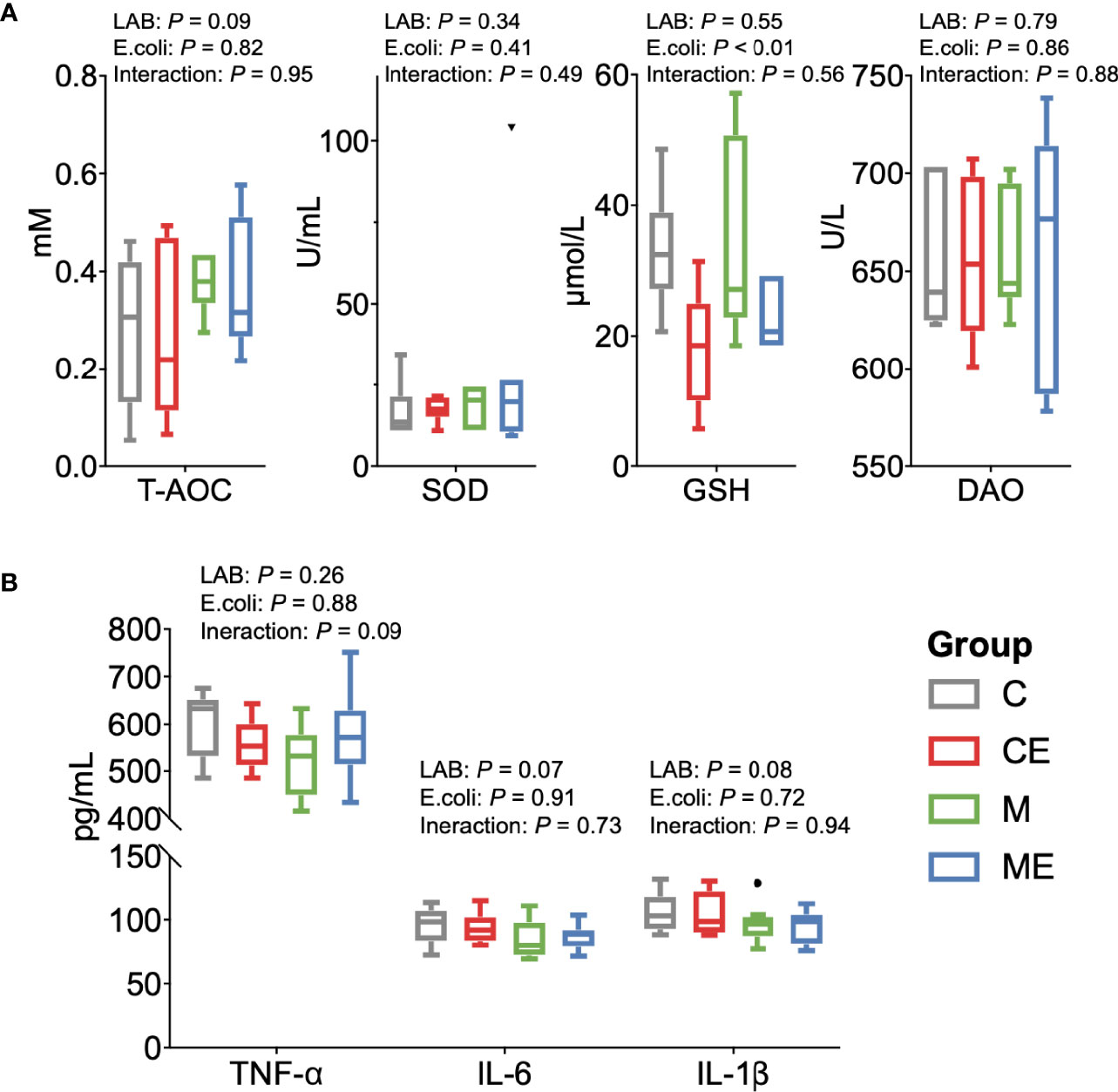

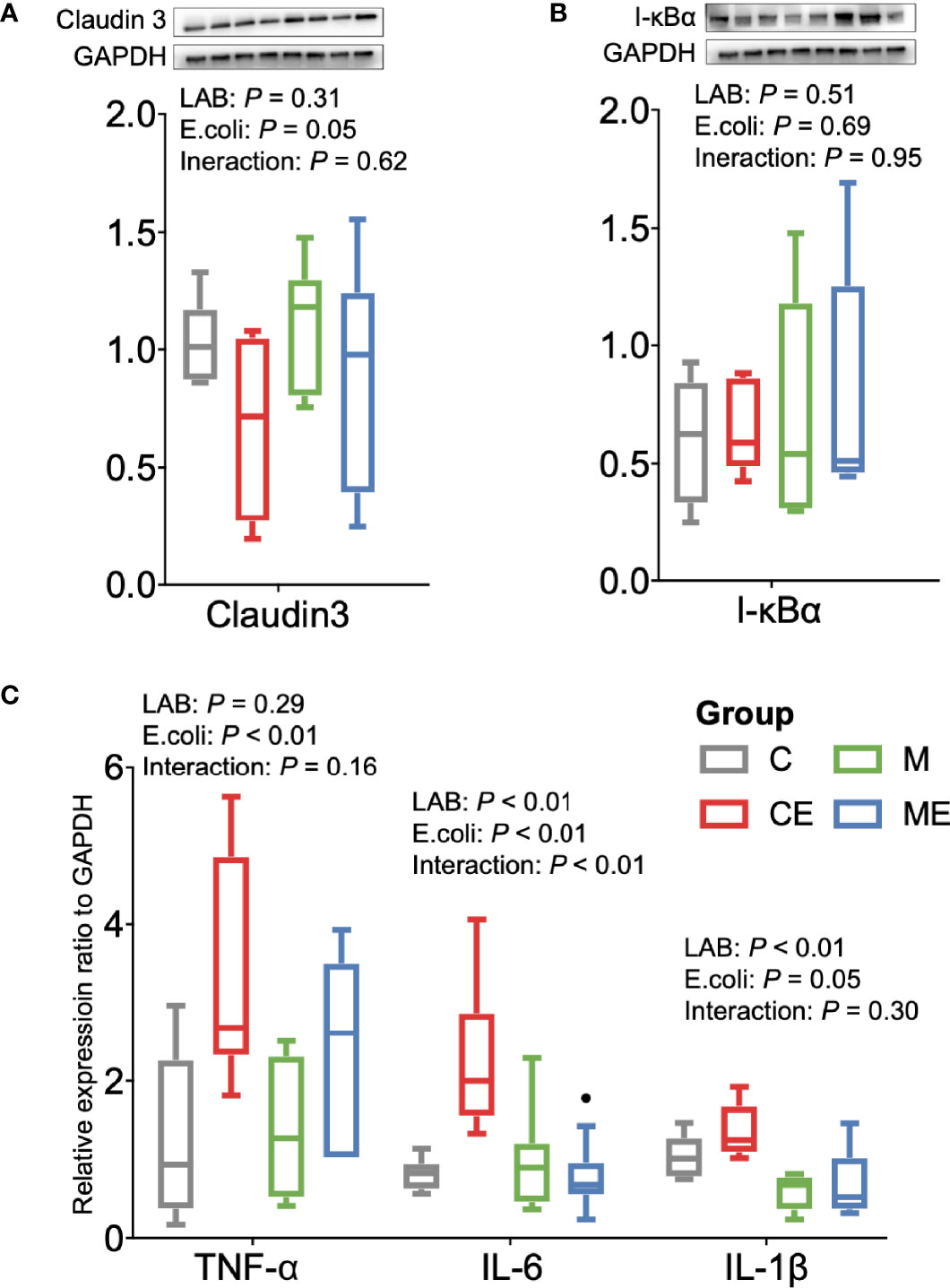

The oxidative stress of mice was assessed (Figure 5A); the LAB, E. coli, or both showed no significant (p > 0.05) effect on the T-AOC and SOD levels in serum between C, CE, M, and ME mice. CE and ME mice challenged with E. coli showed a significantly lower (p < 0.01) GSH level in the serum than that in C and M mice. When cytokines in the serum were measured (Figure 5B), LAB or E. coli showed no significant (p > 0.05) effects on the concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in the serum between four groups. In the gut, administration of mixed LAB strains or E. coli also showed no significant (p > 0.05) effects on the proteins claudin-3 and I-κBα between four groups (Figures 6A, B). A significant difference of cytokines in the gut was observed between four groups (Figure 6C). Challenge with E. coli elevated the levels of TNF-α (p < 0.01) and IL-1β (p < 0.01) in the gut, and administration of LAB significantly lowered the IL-1β (p < 0.01) and IL-6 (p < 0.01) in the gut of mice. The interaction (p < 0.01) of mixed LAB strains and E. coli was observed in the IL-6 level of gut between four groups.

Figure 5 Oxidant and inflammation status of the serum in control mice (C), control mice challenged with Escherichia coli (CE), mice fed mixed LAB strains (M), and mice fed mixed LAB strains and challenged with Escherichia coli (ME). (A) Oxidative stress parameters and (B) cytokines in the serum of mice between four groups. T-AOC, total antioxidant capacity colorimetric; SOD, superoxidase dismutase; GSH, glutathione; DAO, diamine oxidase; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL, interleukin.

Figure 6 Inflammation status of the gut in control mice (C), control mice challenged with Escherichia coli (CE), mice fed mixed LAB strains (M), and mice fed mixed LAB strains and challenged with Escherichia coli (ME). Ratio of (A) Claudin3, (B) I-κBα, and (C) mRNA expression of cytokines in the gut of mice between four groups. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; I-κBα, nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL, interleukin.

4 Discussion

In this study, LAB strains from wild pig were isolated and characterized, which showed beneficial effects on the gut health in mice. Our results revealed the probiotics of LAB strains and the mechanisms in mediating immune defenses against E. coli in the gut, highlighting the importance of probiotics in healthy individuals.

LAB is known as a probiotic group and is normally found in the gut, which has been widely applied in humans and animals to promote gut health (21, 22). Compared with the domestic pigs, higher abundance of Lactobacillus was found in the gut of wild pig in our study, suggesting the potential relationship between LAB and high disease resistance of wild pigs. As a part of LAB, Lactobacillus contributes to the growth and reduction of diarrhea and inhibition of pathogens in pigs (23). Thus, wild pigs might benefit from the high abundance of Lactobacillus in the gut. However, previous studies usually observed a higher abundance of Lactobacillus in the gut of commercial and domestic native pigs than wild pigs (12, 24), which is inconsistent with our results, partly due to the differential environment or geography (25, 26).

When LAB strains were isolated and cultured, a total of 11 LAB strains were identified and assigned as 5 species, including L. mucosae, L. fermentum, L. delbrueckii, L. rhamnosus, and Enterococcus faecalis. Similar to previous studies, L. mucosae and L. fermentum were also isolated from wild pigs (13, 27), indicating the widely distributed inhabitants in the pig. As the characteristics of 11 LAB strains were described, ZJU_AH817 showed the lower hydrophobicity but higher tolerance of acid, bile salt, and Zn2+ among the 11 strains. Cell-surface hydrophobicity was associated with bacterial attachment to the surface (28, 29), and greater hydrophobicity of bacteria means higher levels of adhesion (30), which was the first step for the LAB strains performing beneficial effects on the host (31). Moreover, the viability and survival of LAB strains were one of the most important parameters in the condition of low pH from the stomach and bile secreted in the intestine (32). Thus, despite the lower hydrophobicity of ZJU_AH817 which might make it difficult to adhere to the gut, higher tolerance of the acid and bile salt could contribute to the existence of ZJU_AH817 in wild pigs for further properties. What is more, differential tolerance of acid, bile salt, and Zn2+ between strains (ZJU_AH813, ZJU_AH814, ZJU_AH815, ZJU_AH816, ZJU_AH817, ZJU_AH818) even from the same species L. mucosae was observed, suggesting that the variation of bacteria at the strain level also demonstrated differential function in adhesion (33), immunity (34), and diseases (35). The lower auto-aggregation of mixed LAB strains than other strains also suggested the variation between different strains (36). On the other hand, the tolerance of Zn2+ and Cu2+ indicates the possibility in the application of LAB strains in pigs, since zinc and copper are classified as trace minerals required by pigs and usually supplemented in diet (37).

The efficacy of single-strained and multi-strained mixture probiotics remains debated. McFarland reviewed randomized controlled trials and found a similar efficiency of mixtures and single strains in the prevention or treatment of disease (38), while Chapman and Gibson claimed that the mixtures appear to be more effective against a wide range of end points (39). The synergistic interactions between mixed strains could be the key which influences the efficiency of probiotics (40). Since the LAB strains were isolated together from the wild pig in this study, we believe that the synergistic interactions of 11 LAB strains could exist and be more effective than a single strain. When administrated with the mixed LAB strains, mice showed higher LAB counts in the gut and feces, suggesting the colonization of LAB strains. Probiotic strains could stimulate the enterocyte migration in mice (41, 42); higher crypt depth in mice administrated with LAB strains was observed in our study, which was in accordance with previous studies. Indeed, Butyricicoccus, one of the butyrate producers (43), enriched in mice administrated with LAB strains, could also contribute to the crypt depth via butyrate in the colon (44). In addition to the colonization and crypt depth, similar feed intake, weight gain, gut microbiota profiles, or serum oxidative parameters between M and C groups were observed, suggesting that colonization of LAB strains showed a limited effect on healthy individuals. Recently, a systemic review also concluded that the probiotic supplementation showed a limited effect on immune and inflammatory markers in healthy adults (45).

Published studies usually focused on metabolic actions of probiotics while paying less attention on the immune response of probiotics. In our study, mixed LAB strains exerted the beneficial effects via the immunomodulation effects when inflammation of the gut and liver occurred in mice challenged with E. coli. Vacuolization of liver and lower GSH concentrations in the serum was observed, suggesting the oxidative stress triggered by E. coli (46). In the gut, higher diversity and differential patterns of microbiota in the M group were observed than those in the CE and ME group. Loss of microbiota diversity appears as a common feature of gut dysbiosis and diseases in several human studies (47, 48), which highlighted the importance of supplementation with probiotics in the improvement of diversity and gut health (49). LEfSe analysis revealed the alteration of specific bacterial genera after challenge with E. coli in mice, for instance, higher relative abundance of Enterorhabdus and Akkermansia was observed in mice challenged with E. coli. Enterorhabdus isolated from the inflamed ileal mucosa in a mouse (50) were observed to be enriched in the disordered gut of mice fed a Western-style diet or high-fructose intake (51). Lower abundance of Enterorhabdus in the gut suggests the improvement of gut health in mice fed with mixed LAB strains. However, Akkermansia, one of the next-generation probiotics (52, 53), was enriched in mice challenged with E. coli, which was inconsistent with previous studies, and the mechanism behind it requires further investigation. Besides, challenge with E. coli lowered the relative abundance of Clostridium IV in mice. As one of the major inhabitants in the gut, a decrease in Clostridium IV was associated with loss of gut microbiome colonization resistance in patients with chronic gut inflammation compared to healthy subjects (54, 55).

Apart from the gut microbiota, challenge with E. coli altered the gut morphology and tight junction, together with increased levels of cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in the gut. The villi, crypts, and villus height-to-crypt depth ratio are critical histomorphometric parameters in the final stage of nutrient digestion and assimilation (56). Human studies showed that E. coli could induce damage to epithelial cells (57). Similar to the previous study, a lower trend of a sealing component of tight junction, claudin 3, was also observed in the mice challenged with E. coli. What is more, previous studies revealed that damage of epithelial cells induced by E. coli also interacted with the elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in fecal samples from children and adult with diarrhea (58, 59). A study on mice also showed that impairment of the gut might be highly related to the increase in oxidative stress, including the upregulation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) (60). During the inflammatory response, pro-inflammatory cytokines are produced, which cause disruption of the gut barrier (61). Overexpression of several cytokines in the inflamed gut has been suggested as a contributor to impairment of the gut. For example, in vitro studies revealed that TNF-α could decrease the protein expression of the tight-junction proteins (62, 63). In various inflammatory diseases of the gut, IL-6 has been shown to play a critical role and contribute to the pro-inflammatory cascade, which includes barrier disruption (64, 65). Previous studies also showed that IL-1β caused an increase of permeability in the gut both in vivo and in vitro (66, 67). On the other hand, studies indicated that inhibition of cytokines could exert beneficial effects against intestinal mucosal damage and development of inflammation in the gut (61). However, no significant difference of inflammation cytokines in serum was observed including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β between four groups, indicating that the challenge of E. coli ATCC 25922 (18) might induce a local rather than a systemic inflammation in mice.

When challenged with E. coli in mice fed with mixed LAB strains, a lower trend of the relative abundance of Desulfovibrio was observed. The opportunistic pathogen Desulfovibrio enriched in patients with chronic inflammatory processes (68) and oral administration of probiotic strain L. plantarum P-8 decreased the abundance of Desulfovibrio in adults of different ages (69). Apart from the inhibition of potential pathogens, supplementation of mixed LAB strains also attenuated the inflammation in the liver and gut in mice challenged with E. coli. Previous studies also revealed that pretreatment of probiotics L. reuteri ZJ617 attenuated the hepatic inflammatory and autophagy through the gut–liver axis both in mice (70) and in piglets (71). After challenge with E. coli, lower levels of IL-6 and IL-1β in the gut of mice administrated with mixed LAB strains were observed than those in the control group, indicating the immunomodulation effect of LAB strains isolated from the wild pig. Since the importance of gut microbiota to the immune system has been demonstrated (72), it is urgent to apply probiotics treating various diseases via regulation of cytokine profiles in the gut (73).

Taken together, mixed LAB strains from wild pig exerted a beneficial effect on the host via immunomodulation of IL-6 and IL-1β against the infection of E. coli in the gut while the exact mechanisms behind it, including specific components/metabolites derived from the LAB strains and pathways in the gut, warrant further illustration. Also, other probiotics including bacillus, yeast, and some other bacterium in the gut of wild pigs warrant further investigation in future studies. This study highlighted the importance of preserving bacterial diversity and beneficial effects of LAB strains mixture from wild pig as probiotics in the gut.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang University.

Author Contributions

HW designed the experiments. DF, ZD, WT, JM, TZ, and YuZ performed the experiments. HW, YiZ, DF, and JL analyzed the data. HW and YiZ wrote and revised the main manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Key R&D Projects of Zhejiang Province (2022C02015), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (Z19C170001), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0500502), and the Funds of Ten Thousand People Plan.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Leluo Guan for suggestion on data analysis. We thank Dr. Xin Luo for critical review for the article. We thank Shanghai Realbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd., for help on Illumina sequencing.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.822754/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Guinane CM, Cotter PD. Role of the Gut Microbiota in Health and Chronic Gastrointestinal Disease: Understanding a Hidden Metabolic Organ. Therap Adv Gastroenterol (2013) 6(4):295–308. doi: 10.1177/1756283x13482996

2. Zheng D, Liwinski T, Elinav E. Interaction Between Microbiota and Immunity in Health and Disease. Cell Res (2020) 30(6):492–506. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0332-7

3. Silva DR, Sardi J, Pitangui N, Roque SM, Silva A, Rosalen PL. Probiotics as an Alternative Antimicrobial Therapy: Current Reality and Future Directions. J Funct Foods (2020) 7(3):104080–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.104080

4. Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, Gibson GR, Merenstein DJ, Pot B, et al. Expert Consensus Document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics Consensus Statement on the Scope and Appropriate Use of the Term Probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2014) 11(8):506–14. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66

5. Pessione E. Lactic Acid Bacteria Contribution to Gut Microbiota Complexity: Lights and Shadows. Front Cell Infect Microbiol (2012) 8:86(6). doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00086

6. Thomas CM, Versalovic J. Probiotics-Host Communication: Modulation of Signaling Pathways in the Intestine. Gut Microbes (2010) 1(3):148–63. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.3.11712

7. Fontana L, Bermudez-Brito M, Plaza-Diaz J, Muñoz-Quezada S, Gil A. Sources, Isolation, Characterisation and Evaluation of Probiotics. Br J Nutr (2013) 10(9):S35–50. doi: 10.1017/s0007114512004011

8. De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Poullet JB, Massart S, et al. Impact of Diet in Shaping Gut Microbiota Revealed by a Comparative Study in Children From Europe and Rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2010) 107(33):14691–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107

9. Petrof EO. Probiotics and Gastrointestinal Disease: Clinical Evidence and Basic Science. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem (2009) 8(3):260–9. doi: 10.2174/187152309789151977

10. Zhang W, Wang H, Liu J, Zhao Y, Gao K, Zhang J. Adhesive Ability Means Inhibition Activities for Lactobacillus Against Pathogens and S-Layer Protein Plays an Important Role in Adhesion. Anaerobe (2013) 2(2):97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.06.005

11. Montes-Sánchez JJ, Huato-Soberanis L, Buntinx-Dios SE, Leon-de La Luz JL. The Feral Pig in a Low Impacted Ecosystem: Analysis of Diet Composition and its Utility. Rangel Ecol Manage (2020) 73(5):703–11. doi: 10.1016/j.rama.2020.05.006

12. Huang J, Zhang W, Fan R, Liu Z, Huang T, Li J, et al. Composition and Functional Diversity of Fecal Bacterial Community of Wild Boar, Commercial Pig and Domestic Native Pig as Revealed by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing. Arch Microbiol (2020) 202(4):843–57. doi: 10.1007/s00203-019-01787-w

13. Li M, Wang Y, Cui H, Li Y, Sun Y, Qiu H-J. Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated From the Gastrointestinal Tract of a Wild Boar as Potential Probiotics. Front Vet Sci (2020) 4:49(9). doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00049

14. Kwoji ID, Aiyegoro OA, Okpeku M, Adeleke MA. Multi-Strain Probiotics: Synergy Among Isolates Enhances Biological Activities. Biol (Basel) (2021) 4:322–42. doi: 10.3390/biology10040322

15. Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. Genomic Insights That Advance the Species Definition for Prokaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2005) 102(7):2567–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409727102

16. Alander M, Satokari R, Korpela R, Saxelin M, Vilpponen-Salmela T, Mattila-Sandholm T, et al. Persistence of Colonization of Human Colonic Mucosa by a Probiotic Strain, Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG, After Oral Consumption. Appl Environ Microbiol (1999) 65(1):351–4. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.1.351-354.1999

17. Xu H, Jeong HS, Lee HY, Ahn J. Assessment of Cell Surface Properties and Adhesion Potential of Selected Probiotic Strains. Lett Appl Microbiol (2009) 49(4):434–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02684.x

18. Hajam IA, Ali F, Young J, Garcia MA, Cannavino C, Ramchandar N, et al. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Plasma From Children With Short Bowel Syndrome. Pathogens (2021) 10(8):1021. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10081021

19. Lin CJ, Chiu CC, Chen YC, Chen ML, Hsu TC, Tzang BS. Taurine Attenuates Hepatic Inflammation in Chronic Alcohol-Fed Rats Through Inhibition of TLR4/MyD88 Signaling. J Med Food (2015) 18(12):1291–8. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2014.3408

20. Kruger NJ. The Bradford Method for Protein Quantitation. In: The Protein Protocols Handbook. Totowa, NJ: Human Press (2009). p. 17–24. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-198-7_4

21. Ray K. Lactobacillus Probiotic Could Prevent Recurrent UTI. Nat Rev Urol (2011) 6:292–2. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.72

22. Gareau MG, Sherman PM, Walker WA. Probiotics and the Gut Microbiota in Intestinal Health and Disease. Nat Rev Gastrol Hepatol (2010) 7(9):503–14. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.117

23. Valeriano VDV, Balolong MP, Kang DK. Probiotic Roles of Lactobacillus Sp. In Swine: Insights From Gut Microbiota. J Appl Microbiol (2017) 3:554–67. doi: 10.1111/jam.13364

24. Ushida K, Tsuchida S, Ogura Y, Toyoda A, Maruyama F. Domestication and Cereal Feeding Developed Domestic Pig-Type Intestinal Microbiota in Animals of Suidae. Anim Sci J (2016) 87(6):835–41. doi: 10.1111/asj.12492

25. Tasnim N, Abulizi N, Pither J, Hart MM, Gibson DL. Linking the Gut Microbial Ecosystem With the Environment: Does Gut Health Depend on Where We Live? Front Microbiol (2017) 8:1935. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01935

26. Gupta VK, Paul S, Dutta C. Geography, Ethnicity or Subsistence-Specific Variations in Human Microbiome Composition and Diversity. Front Microbiol (2017) 8:1162. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01162

27. Klose V, Bayer K, Kern C, Goelß F, Fibi S, Wegl G. Antibiotic Resistances of Intestinal Lactobacilli Isolated From Wild Boars. Vet Microbiol (2014) 1:240–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.11.014

28. Krasowska A, Sigler K. How Microorganisms Use Hydrophobicity and What Does This Mean for Human Needs? Front Cell Infect Microbiol (2014) 4:112. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00112

29. Arellano-Ayala K, Ascencio-Valle FJ, Gutiérrez-González P, Estrada-Girón Y, Torres-Vitela MR, Macías-Rodríguez ME. Hydrophobic and Adhesive Patterns of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Their Antagonism Against Foodborne Pathogens on Tomato Surface (Solanum Lycopersicum L.). J Appl Microbiol (2020) 129(4):876–91. doi: 10.1111/jam.14672

30. Marín ML, Benito Y, Pin C, Fernández MF, García ML, Selgas MD, et al. Lactic Acid Bacteria: Hydrophobicity and Strength of Attachment to Meat Surfaces. Lett Appl Microbiol (1997) 24(1):14–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00334.x

31. Wang R, Jiang L, Zhang M, Zhao L, Hao Y, Guo H, et al. The Adhesion of Lactobacillus Salivarius REN to a Human Intestinal Epithelial Cell Line Requires S-Layer Proteins. Sci Rep (2017) 7:44029–39. doi: 10.1038/srep44029

32. Succi M, Tremonte P, Reale A, Sorrentino E, Grazia L, Pacifico S, et al. Bile Salt and Acid Tolerance of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus Strains Isolated From Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese. FEMS Microbiol Lett (2005) 244(1):129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.01.037

33. Patnode ML, Guruge JL, Castillo JJ, Couture GA, Lombard V, Terrapon N, et al. Strain-Level Functional Variation in the Human Gut Microbiota Based on Bacterial Binding to Artificial Food Particles. Cell Host Microbe (2021) 29(4):664–73.e665. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.01.007

34. Tientcheu LD, Koch A, Ndengane M, Andoseh G, Kampmann B, Wilkinson RJ. Immunological Consequences of Strain Variation Within the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex. Eur J Immunol (2017) 47(3):432–45. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646562

35. Wiens KE, Woyczynski LP, Ledesma JR, Ross JM, Zenteno-Cuevas R, Goodridge A, et al. Global Variation in Bacterial Strains That Cause Tuberculosis Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Med (2018) 16:196–212. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1180-x

36. Trunk T, Khalil HS, Leo JC. Bacterial Autoaggregation. AIMS Microbiol (2018) 4(1):140–64. doi: 10.3934/microbiol.2018.1.140

37. Dębski B. Supplementation of Pigs Diet With Zinc and Copper as Alternative to Conventional Antimicrobials. Pol J Vet Sci (2016) 19(4):917–24. doi: 10.1515/pjvs-2016-0113

38. McFarland LV. Efficacy of Single-Strain Probiotics Versus Multi-Strain Mixtures: Systematic Review of Strain and Disease Specificity. Dig Dis Sci (2021) 66(3):694–704. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06244-z

39. Chapman CMC, Gibson GR, Rowland I. Health Benefits of Probiotics: Are Mixtures More Effective Than Single Strains? Eur J Nutr (2011) 1:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00394-010-0166-z

40. Westfall S, Carracci F, Estill M, Zhao D, Wu Q-l, Shen L, et al. Optimization of Probiotic Therapeutics Using Machine Learning in an Artificial Human Gastrointestinal Tract. Sci Rep (2021) 11:1067–83. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79947-y

41. Preidis GA, Saulnier DM, Blutt SE, Mistretta TA, Riehle KP, Major AM, et al. Probiotics Stimulate Enterocyte Migration and Microbial Diversity in the Neonatal Mouse Intestine. FASEB J (2012) 5:1960–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-177980

42. Ichikawa H, Kuroiwa T, Inagaki A, Shineha R, Nishihira T, Satomi S, et al. Probiotic Bacteria Stimulate Gut Epithelial Cell Proliferation in Rat. Dig Dis Sci (1999) 44(10):2119–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1026647024077

43. Boesmans L, Valles-Colomer M, Wang J, Eeckhaut V, Falony G, Ducatelle R, et al. Butyrate Producers as Potential Next-Generation Probiotics: Safety Assessment of the Administration of Butyricicoccus Pullicaecorum to Healthy Volunteers. mSystems (2018) 6:1–11. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00094-18

44. Kaiko GE, Ryu SH, Koues OI, Collins PL, Solnica-Krezel L, Pearce EJ, et al. The Colonic Crypt Protects Stem Cells From Microbiota-Derived Metabolites. Cell (2016) 165(7):1708–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.018

45. Mohr AE, Basile AJ, Crawford MS, Sweazea KL, Carpenter KC. Probiotic Supplementation Has a Limited Effect on Circulating Immune and Inflammatory Markers in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Acad Nutr Diet (2020) 120(4):548–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.08.018

46. Yuan L, Kaplowitz N. Glutathione in Liver Diseases and Hepatotoxicity. Mol Aspects Med (2009) 1:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.003

47. Ahn J, Sinha R, Pei Z, Dominianni C, Wu J, Shi J, et al. Human Gut Microbiome and Risk for Colorectal Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst (2013) 105(24):1907–11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt300

48. Matsuoka K, Kanai T. The Gut Microbiota and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Semin Immunopathol (2015) 37(1):47–55. doi: 10.1007/s00281-014-0454-4

49. Grazul H, Kanda LL, Gondek D. Impact of Probiotic Supplements on Microbiome Diversity Following Antibiotic Treatment of Mice. Gut Microbes (2016) 7(2):101–14. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2016.1138197

50. Clavel T, Charrier C, Braune A, Wenning M, Blaut M, Haller D. Isolation of Bacteria From the Ileal Mucosa of TNFdeltaARE Mice and Description of Enterorhabdus Mucosicola Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol (2009) 7:1805–12. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.003087-0

51. Volynets V, Louis S, Pretz D, Lang L, Ostaff MJ, Wehkamp J, et al. Intestinal Barrier Function and the Gut Microbiome Are Differentially Affected in Mice Fed a Western-Style Diet or Drinking Water Supplemented With Fructose. J Nutr (2017) 5:770–80. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.242859

52. Reunanen J, Kainulainen V, Huuskonen L, Ottman N, Belzer C, Huhtinen H, et al. Akkermansia Muciniphila Adheres to Enterocytes and Strengthens the Integrity of the Epithelial Cell Layer. Appl Environ Microbiol (2015) 81(11):3655–62. doi: 10.1128/aem.04050-14

53. Xu Y, Wang N, Tan H-Y, Li S, Zhang C, Feng Y. Function of Akkermansia Muciniphila in Obesity: Interactions With Lipid Metabolism, Immune Response and Gut Systems. Front Microbiol (2020) 11:219. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00219

54. Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-Phylogenetic Characterization of Microbial Community Imbalances in Human Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2007) 104(34):13780–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706625104

55. Lopetuso LR, Scaldaferri F, Petito V, Gasbarrini A. Commensal Clostridia: Leading Players in the Maintenance of Gut Homeostasis. Gut Pathog (2013) 1:23–31. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-5-23

56. Seyyedin S, Nazem MN. Histomorphometric Study of the Effect of Methionine on Small Intestine Parameters in Rat: An Applied Histologic Study. Folia Morphol (Warsz) (2017) 76(4):620–9. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2017.0044

57. Hicks S, Candy DC, Phillips AD. Adhesion of Enteroaggregative Escherichia Coli to Pediatric Intestinal Mucosa In Vitro. Infect Immun (1996) 64(11):4751–60. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4751-4760.1996

58. Mercado EH, Ochoa TJ, Ecker L, Cabello M, Durand D, Barletta F, et al. Fecal Leukocytes in Children Infected With Diarrheagenic Escherichia Coli. J Clin Microbiol (2011) 49(4):1376–81. doi: 10.1128/jcm.02199-10

59. Noel G, Doucet M, Nataro JP, Kaper JB, Zachos NC, Pasetti MF. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli is Phagocytosed by Macrophages Underlying Villus-Like Intestinal Epithelial Cells: Modeling Ex Vivo Innate Immune Defenses of the Human Gut. Gut Microbes (2017) 4:382–9. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1398871

60. Luo Q, Lao C, Huang C, Xia Y, Ma W, Liu W, et al. Iron Overload Resulting From the Chronic Oral Administration of Ferric Citrate Impairs Intestinal Immune and Barrier in Mice. Biol Trace Elem Res (2021) 199(3):1027–36. doi: 10.1007/s12011-020-02218-4

61. Al-Sadi R, Boivin M, Ma T. Mechanism of Cytokine Modulation of Epithelial Tight Junction Barrier. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) (2009) 14:2765–78. doi: 10.2741/3413

62. Ye X, Sun M. AGR2 Ameliorates Tumor Necrosis Factor-α-Induced Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction via Suppression of NF-κb P65-Mediated MLCK/p-MLC Pathway Activation. Int J Mol Med (2017) 39(5):1206–14. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2928

63. Watari A, Sakamoto Y, Hisaie K, Iwamoto K, Fueta M, Yagi K, et al. Rebeccamycin Attenuates TNF-α-Induced Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction by Inhibiting Myosin Light Chain Kinase Production. Cell Physiol Biochem (2017) 41(5):1924–34. doi: 10.1159/000472367

64. Seegert D, Rosenstiel P, Pfahler H, Pfefferkorn P, Nikolaus S, Schreiber S. Increased Expression of IL-16 in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut (2001) 48(3):326–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.3.326

65. Al-Sadi R, Ye D, Boivin M, Guo S, Hashimi M, Ereifej L, et al. Interleukin-6 Modulation of Intestinal Epithelial Tight Junction Permeability is Mediated by JNK Pathway Activation of Claudin-2 Gene. PLoS One (2014) 3:e85345–85360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085345

66. Al-Sadi R, Ye D, Dokladny K, Ma TY. Mechanism of IL-1β-Induced Increase in Intestinal Epithelial Tight Junction Permeability. J Immunol (2008) 8:5653–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5653

67. Al-Sadi R, Guo S, Dokladny K, Smith MA, Ye D, Kaza A, et al. Mechanism of Interleukin-1β Induced-Increase in Mouse Intestinal Permeability In Vivo. J Interferon Cytokine Res (2012) 10:474–84. doi: 10.1089/jir.2012.0031

68. Loubinoux J, Bronowicki J-P, Pereira IAC, Mougenel J-L, Le Faou AE. Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria in Human Feces and Their Association With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. FEMS Microbiol Ecol (2002) 2:107–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00942.x

69. Wang L, Zhang J, Guo Z, Kwok L, Ma C, Zhang W, et al. Effect of Oral Consumption of Probiotic Lactobacillus Planatarum P-8 on Fecal Microbiota, SIgA, SCFAs, and TBAs of Adults of Different Ages. Nutrition (2014) 7:776–83.e771. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.11.018

70. Cui Y, Qi S, Zhang W, Mao J, Tang R, Wang C, et al. Lactobacillus Reuteri ZJ617 Culture Supernatant Attenuates Acute Liver Injury Induced in Mice by Lipopolysaccharide. J Nutr (2019) 149(11):2046–55. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxz088

71. Zhu T, Mao J, Zhong Y, Huang C, Deng Z, Cui Y, et al. L. Reuteri ZJ617 Inhibits Inflammatory and Autophagy Signaling Pathways in Gut-Liver Axis in Piglet Induced by Lipopolysaccharide. J Anim Sci Biotechnol (2021) 1f:110–26. doi: 10.1186/s40104-021-00624-9

72. Wu HJ, Wu E. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Immune Homeostasis and Autoimmunity. Gut Microbes (2012) 3(1):4–14. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19320

Keywords: wild pig, lactic acid bacteria, gut microbiota, immunomodulation, gut health

Citation: Zhong Y, Fu D, Deng Z, Tang W, Mao J, Zhu T, Zhang Y, Liu J and Wang H (2022) Lactic Acid Bacteria Mixture Isolated From Wild Pig Alleviated the Gut Inflammation of Mice Challenged by Escherichia coli. Front. Immunol. 13:822754. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.822754

Received: 26 November 2021; Accepted: 05 January 2022;

Published: 26 January 2022.

Edited by:

Yigang Xu, Zhejiang A&F University, ChinaReviewed by:

Qinghua Yu, Nanjing Agricultural University, ChinaJiyuan Yin, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, China

Copyright © 2022 Zhong, Fu, Deng, Tang, Mao, Zhu, Zhang, Liu and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haifeng Wang, aGFpZmVuZ3dhbmdAemp1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Yifan Zhong†

Yifan Zhong† Dongyan Fu

Dongyan Fu Yu Zhang

Yu Zhang Jianxin Liu

Jianxin Liu Haifeng Wang

Haifeng Wang