94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Immunol. , 15 November 2021

Sec. Autoimmune and Autoinflammatory Disorders

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.715839

Psoriasis is a chronic and recurrent immune-related skin disease that often causes disfigurement and disability. Due to the visibility of lesions in patients and inadequate understanding of dermatology knowledge in the general public, patients with psoriasis often suffer from stigma in their daily lives, which has adverse effects on their mental health, quality of life, and therapeutic responses. This review summarized the frequently used questionnaires and scales to evaluate stigmatization in patients with psoriasis, and recent advances on this topic. Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire, Questionnaire on Experience with Skin Complaints, and 6-item Stigmatization Scale have been commonly used. The relationship between sociodemographic characteristics, disease-related variables, psychiatric disorders, quality of life, and stigmatization in patients with psoriasis has been thoroughly investigated with these questionnaires. Managing the stigmatization in patients with psoriasis needs cooperation among policymakers, dermatologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, researchers, and patients. Further studies can concentrate more on these existing topics, as well as other topics, including predictors of perceived stigmatization, stigmatization from non-patient groups, influence of biologics on stigmatization, and methods of coping with stigmatization.

Psoriasis is a chronic and recurrent inflammatory skin disease characterized by clearly demarcated, scaly, erythematous plaques (1–4). Beyond the conventional definition of a skin disorder, psoriasis is now considered a systemic disease (5). Patients with psoriasis may be affected in other organs, such as joint (6) and cardiovascular system (7). Moreover, patients with psoriasis are susceptible to a variety of psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety (8), bipolar mood disorder (9), personality disorder (10), and cognitive impairment (11). Psoriasis may place a heavy physical and psychological burden on patients, negatively affecting patients’ health status, private lives, and professional careers (12). Psoriasis could substantially diminish the quality of life in physical, emotional, and social functioning (13, 14).

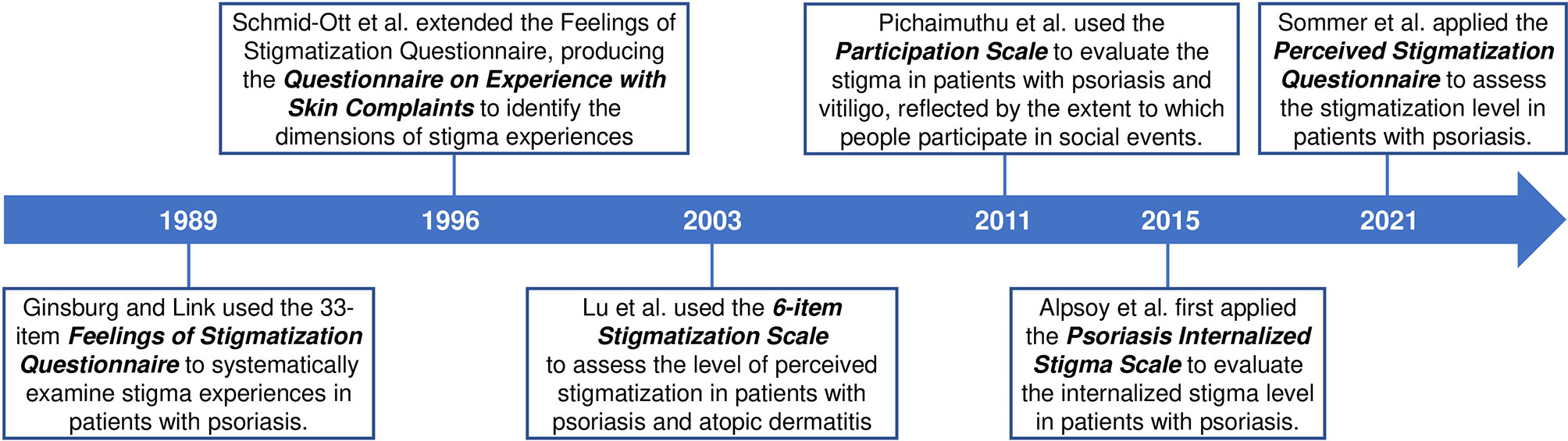

Stigmatization was defined as the assignment of biological or social discrediting perceptions to a person, distinguishing a person from others of a society (15, 16). The feeling of stigmatization is common in dermatologic patients, such as psoriasis, vitiligo, and leprosy, mainly because of visible skin lesions, insufficient public understanding of the diseases, and other cultural or social factors (15, 17). Back in the 1950s, Susskind and McGuire reported that psoriasis patients might be exposed to curiosity, hostility, and disgust, because of their “unclean skin” and public concerns about infectivity (18). The publicity of “psoriasis as non-infectious disease” could reduce the burden of these patients (19). In 2018, a global survey included 8,338 patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis from 31 countries (20). 84% of the respondents experienced psoriasis-related discrimination and/or humiliation, which had negative effects on work, intimacy, and health status. Psoriasis patients may experience social and psychological difficulties in their daily lives, especially when they need to expose their bodies (21). Patients with psychological distress may lose hope and feel out of control over the disease, impairing the response to their therapies (21, 22). In recent years, more and more studies have been conducted on the relationship between stigmatization, sociodemographic characteristics, disease-related variables, and psychiatric disorders in patients with psoriasis. Both dermatology-specific and disease-specific questionnaires can be utilized to evaluate the stigmatization level of psoriasis patients (16, 23). This review aims to summarize these frequently used questionnaires and scales (Figure 1), and recent advances on stigmatization in patients with psoriasis, which may facilitate the understanding of this topic and pave the way for further research.

Figure 1 Commonly used questionnaires and scales to evaluate the stigmatization in patients with psoriasis.

In 1989, Ginsburg and Link, using “Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire”, systematically examined stigma experiences in 100 psoriasis patients, and identified six dimensions of stigma (24). This questionnaire is a disease-specific questionnaire consisting of 33 items. The six dimensions were “anticipation of rejection, feeling of being flawed, sensitivity to others’ attitudes, guilt and shame, secretiveness, and positive attitudes”. Stigmatization may result in poor compliance and worsening status. The emphasis on stigmatization in patients with psoriasis has important implications, not only for their quality of life, but also for the clinical management of them.

Several studies used Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire to evaluate the stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. In 1993, Ginsburg and Link also found that 19% of psoriasis patients experienced episodes of gross rejection due to their skin disease, mainly from a gym, pool, hairdresser, or job (25). Rejection experiences may induce the feeling of being stigmatized and bring about adverse effects on emotions and occupations. Zięciak and colleagues used Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire and Beck Depression Inventory, and found the correlation between the feelings of stigmatization and depressive symptoms in patients with psoriasis (26). In 2017, Hawro and colleagues assessed the stigmatization of 115 psoriasis patients using the Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire, and found that lesions on the back of hands, rather than overall disease severity, were associated with higher stigmatization levels (12). One possible explanation for this association was the fear of infection, especially when shaking hands, being touched, or touching the same objects. Stigmatization appeared to predict the quality of life impairment best among all analyzed variables. In 2020, Jankowiak and colleagues explored whether sociodemographic variables were related to the stigmatization and quality of life of patients with psoriasis (27). They used the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) to evaluate the level of stigmatization and quality of life, respectively. Authors found that gender and age correlated with different domains of stigmatization, and quality of life correlated significantly with two domains of stigmatization.

In 1996, Schmid-Ott and colleagues adopted and extended the Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire, producing the Questionnaire on Experience with Skin Complaints (28). It was used to identify the dimensions of stigma experience in 187 psoriasis patients. Five factors were identified, including self-esteem, retreat, rejection, composure, and concealment. This questionnaire could assess the stigma experiences of patients with psoriasis and other skin diseases. The same research group also evaluated its validity and concluded that it was valid and reliable in evaluating stigma feelings in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis patients (29). In 2003, the short version of the Questionnaire on Experience with Skin Complaints was used for the first time by the research group (30). The short form with 23 items was more economical and had a satisfying Cronbach’s alpha, indicating good validity. Four dimensions of the questionnaire were confirmed by factor analysis, including impairment of self-esteem and withdrawal, rejection experienced, concealment, and composure. In psoriasis and atopic dermatitis patients, the Questionnaire on Experience with Skin Complaints was found to have a middle-high correlation with DLQI.

As a dermatology-specific instrument, Questionnaire on Experience with Skin Complaints has also been commonly used to evaluate the stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. In 2013, Böhm and colleagues investigated the relations between disease severity, gender, stigmatization, and quality of life (31). The stigmatization levels of 381 patients were measured with the Questionnaire on Experience with Skin Complaints. Higher severity of psoriasis was associated with higher stigmatization and lower skin-related quality of life. Men and women experienced different social impacts, but stigmatization affected the quality of life with similar degrees in both genders. In 2014, Bangemann and colleagues adopted the short version of the Questionnaire on Experience with Skin Complains and identified stigmatization as a major predictor of quality of life (8). Quality of life was further the strongest predictor of depression and anxiety.

In 2003, a four-point Likert scale was used to assess the level of perceived stigmatization due to skin disease with the following six items: not attractive due to the skin disease, others staring at the skin disease, others feeling uncomfortable touching me due to the skin disease, others regarding the skin disease as contagious, others avoiding me due to the skin disease, others sometimes making annoying comments about the skin disease (32). Cronbach’s alpha for this 6-item stigmatization scale was over 0.8 in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, which represented good internal consistency. Authors investigated the level of perceived stigmatization and predictors of stigmatization in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, and found that perceived helplessness was the strongest predictor of the experience of stigmatization in both groups. Two limitations should be emphasized. The use of self-report measures might underestimate the contribution of clinical status to stigmatization. Besides, other psychological factors possibly relevant to chronic skin diseases should also be considered.

This 6-item stigmatization scale is a dermatology-specific scale, which has been commonly used with Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire and Questionnaire on Experience with Skin Complaints. Studies also focused on disease severity, quality of life, and feeling of stigmatization with these stigmatization questionnaires and other assessments, including Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), Acceptance of Illness Scale (AIS), Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), and DLQI (33, 34). In a cross-sectional study evaluating stigmatization in Arabic psoriatic patients, researchers found that most patients showed feelings of stigmatization due to psoriasis, and face involvement appeared to be the only independent factor influencing the level of stigmatization (33). Łakuta and colleagues investigated the associations between site of skin lesions and depression, social anxiety, body-related emotions and feelings of stigmatization in patients with psoriasis (35). Several body regions were identified as ‘sensitive’, where psoriasis was associated with negative mental health. Another study included 166 patients with plaque psoriasis to determine their level of stigmatization and the association between the level of stigmatization and other factors (36). Men, countryside dwellers, unmarried persons, patients with a longer history of the disease had significantly higher stigmatization levels than women. In 2021, Kowalewska and colleagues evaluated the effect of disease severity on the quality of life and sense of stigmatization in psoriasis patients (37). Authors concluded that the severity of the disease was the strongest determinant of the quality of life, and the levels of stigmatization correlated significantly with PASI scores.

In 2011, a cross-sectional study evaluated the stigma among vitiligo and psoriasis patients in India (38). The key issue of stigma is that it excludes people from participating in social events. The Participation Scale used in stigma reduction, rehabilitation, and social integration programs was applied to measure the extent to which people participated in social events (39). Researchers found that psoriasis patients faced more restrictions in their daily lives, 28% of whom participated minimally in domestic and social life, and 2.7% of whom had extreme participation restrictions.

In 2015, the Psoriasis Internalized Stigma Scale was first applied to psoriasis patients (40). Internalized stigma includes endorsing negative feelings and beliefs and applying them to oneself, decreasing self-esteem and life-satisfaction, increasing depression and suicidality, and causing difficulty in coping with the illness (41). The Psoriasis Internalized Stigma Scale was proved to be reliable and valid with Cronbach’s alpha 0.89. The Psoriasis Internalized Stigma Scale was significantly correlated with the Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DQoL) scores (r=0.726). A multi-centered, cross-sectional study included 1,485 patients, investigated the internalized stigma state of patients with psoriasis, and identified the factors influencing internalized stigma using Psoriasis Internalized Stigma Scale (41). Authors found that disease severity, involvement of visible body parts, genital area, folds or joints, poorer quality of life, negative perceptions of general health and psychological illnesses were associated with high levels of internalized stigma. Another comparative multi-centered study investigated the internalized stigma in pediatric psoriasis patients (42). Internalized stigma in pediatric patients was associated with poorer quality of life, general health, and psychological illnesses. Unlike adults, internalized stigma in pediatric patients was mainly determined by psoriasis itself, rather than disease severity or involvement of visible body parts, genital area, or folds.

In 2021, Sommer and colleagues used the Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire to assess the level of stigmatization in patients with psoriasis, and found that stigmatization experiences were positively associated with younger age, disease severity, scratching behaviors, dysmorphic concerns, and treatment benefits (43). The Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire is a 5-point Likert scale (never, almost never, sometimes, often, always) with 21 items in six categories, the reliability of which was previously confirmed with Cronbach’s alpha 0.93 in a group of burn survivors (44).

Psoriasis is a chronic and recurrent immune-mediated skin disease that often causes disfigurement and disability in patients (1, 45–48). Due to the inadequate popularization of dermatology knowledge, patients with psoriasis often receive stigmatization in their work and life, negatively affecting their quality of life and even leading to mental illnesses such as anxiety and depression. Over the past few decades, a variety of questionnaires have been developed or applied to assess the stigmatization of patients with psoriasis (16). Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire, Questionnaire on Experience with Skin Complaints, and 6-item Stigmatization Scale are commonly used in stigmatization assessment among psoriasis patients recently, based on which many essential conclusions on stigmatization have been drawn.

It was proved that several factors could predict the stigmatization level of patients with psoriasis, including sociodemographic variables, disease-related variables, and personality variables. Among the sociodemographic variables, gender correlated with stigmatization level in some studies (27, 49), while in others not (26, 34). Lower education (50), lack of professional knowledge (51), and countryside residence (52) were associated with higher levels of stigmatization, which might be secondary to inadequate understanding of psoriasis. The popularization of psoriasis characteristics among the public, particularly its non-infectious nature, might improve the stigmatized condition and the acceptance of patients (53). Among the disease-related variables, age of onset was proved to correlate with feelings of stigmatization, and patients with early-onset age were more susceptible (24, 54, 55). Psoriasis-related social stigma affected individuals in earlier adulthood more negatively, who just established their social relationships and contacted a wider range of people (55). Thus, extra attention should be paid to children and adolescent patients by physicians. Besides, skin lesion distribution and disease severity appeared to be associated with stigmatization in some studies (12, 31, 35, 50). Skin lesions at the exposed areas were associated with higher stigmatization levels, increasing the risk of social exclusion and hurting patients’ quality of life. Therefore, the lesion distribution should be considered together with overall disease severity during the treatment, and psoriasis at the exposed areas required special attention. Moreover, type D personality was found correlated with stigmatization, probably because of the inhibited emotion or behavior caused by fear of disapproval (50). As a result, type D personality screening might be needed to assess the stigmatization level among the patients. Investigation on the proper predictors provided a framework for patients with a high risk of stigmatization, promoting screening and intervention procedures for further implementation of tailored evidence-based treatment (50).

Nowadays, several studies on psoriasis stigmatization have also been conducted based on non-patient groups. In 2018, Sommer and colleagues investigated the public awareness of psoriasis in German (56). 9% of the surveyed thought psoriasis was communicable, and 27% were unwilling to have a personal relationship with the affected. The same group also assessed prejudice and stigmatization of psoriasis patients in the general German population (57). People with psoriasis were considered disadvantaged and disgusting by a majority of the surveyed. Most participants did not want to touch psoriasis patients, and some thought patients should ‘take better care of themselves’. Age, gender, and education level were associated with some prejudiced attitudes. In 2019, Pearl and colleagues compared the stigmatizing attitudes towards psoriasis among laypersons and medical students (51). The medical trainees reported fewer stigmatizing attitudes than laypersons, which indicated that an educational campaign about psoriasis among the public might help reduce the stigmatization of psoriasis patients.

Topical agents are the primary option for patients with mild psoriasis, while systemic treatments are the mainstay for moderate to severe psoriasis. In 2005, Nijsten and colleagues assessed psoriasis patients’ satisfaction with four traditional systemic treatments (58). Less than 40% of the users were very satisfied with any of the four therapies. With a better understanding of pathogenesis, dermatologists began to create new pathogenesis-based therapies, especially various biologics. Over the past two decades, a variety of biologics have been proved to be safe and effective in the treatment of psoriasis, especially in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (13, 59, 60). Biologics are recommended by the American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines as a first-line treatment option for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. The introduction of biologics increased medication adherence and treatment satisfaction (61), and improved patients’ quality of life (62). In 2013, Tennvall and colleagues reported that patients receiving biological treatment of 12 months showed the highest satisfaction and the lowest DLQI score, compared to the topical treatment group and systemic and/or biological <12 months treatment group (62). In 2015, Schaarschmidt and colleagues compared the patients’ satisfaction with four treatment modalities (63). Participants obtaining biologics were the most satisfied, with ustekinumab receiving the highest Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication score. In 2018, Ichiyama and colleagues concluded that treatment satisfaction was significantly correlated with disease severity and quality of life impairment (61). Patients who received biologics were more satisfied than those who received non-biologics, indicating better skin condition and quality of life. Because of the correlation between disease severity, stigmatization, and quality of life (31), the application of biologics probably decreases the level of perceived stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. More research is needed in the future, focusing on the effects of biologics on the stigmatization level in patients with psoriasis.

Methods of helping patients cope with the stigmatization of psoriasis should be emphasized, and necessary psychological and social support should be provided. The potential influence of stress on disease onset and severity was shown in a subgroup of psoriasis patients (64). Therefore, psoriasis management should address both physical and psychosocial aspects. Other forms of support have been emphasized in the treatment of psoriasis, such as relaxation techniques, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and support groups (65). The cooperation of dermatologists and psychiatrists is highly warranted to manage the stigmatization in psoriasis patients. Germen has translated the WHA resolution to a “Destigmatization” program for visible chronic skin diseases (66). Such activities are of great significance in regions where psoriasis is highly prevalent and stigmatized, and require cooperation among policymakers, dermatologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, researchers, and patients (67).

This review summarized the frequently used questionnaires and scales to evaluate stigmatization in patients with psoriasis, and recent advances on this topic. Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire, Questionnaire on Experience with Skin Complaints, and 6-item Stigmatization Scale have been commonly used. The relationship between sociodemographic characteristics, disease-related variables, psychiatric disorders, quality of life, and stigmatization in patients with psoriasis has been thoroughly investigated with these questionnaires. Two limitations should be emphasized. First, the strengths and weaknesses of some questionnaires, and the rationale for developing additional questionnaires were not summarized, because the original articles using these questionnaires focused little on these topics, and few articles compared different questionnaires in evaluating stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. Second, selection bias should also be considered, not only on the selected patients in these studies, but also on the selected articles in this review. Further studies can concentrate more on these existing topics, as well as other topics, including predictors of perceived stigmatization, stigmatization from non-patient groups, influence of biologics on stigmatization, and methods of coping with stigmatization.

HZ, ZY, and KT contributed equally to this manuscript. HZ designed the study and wrote the manuscript. ZY wrote the manuscript. KT and QS made the figure and revised the manuscript. HJ supervised the study. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This paper was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773331 and 82073450), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC0901500).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Lanna C, Galluzzi C, Zangrilli A, Bavetta M, Bianchi L, Campione E. Psoriasis in Difficult to Treat Areas: Treatment Role in Improving Health-Related Quality of Life and Perception of the Disease Stigma. J Dermatol Treat (2020) 1–4. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1770175

2. de la Cueva Dobao P, Notario J, Ferrándiz C, López Estebaranz JL, Alarcón I, Sulleiro S, et al. Expert Consensus on the Persistence of Biological Treatments in Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol (2019) 33(7):1214–23. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15600

3. Hemida AS, Hammam MA, Salman ATA, Shehata WA. Smad7 in Psoriasis Vulgaris Patients: A Clinical and Immunohistochemical Study. J Cosmet Dermatol (2020) 19(12):3395–402. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13425

4. Rigon RB, de Freitas ACP, Bicas JL, Cogo-Müller K, Kurebayashi AK, Magalhães RF, et al. Skin Microbiota as a Therapeutic Target for Psoriasis Treatment: Trends and Perspectives. J Cosmet Dermatol (2021) 20(4):1066–72. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13752

5. Amanat M, Salehi M, Rezaei N. Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders in Psoriasis. Rev Neurosci (2018) 29(7):805–13. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2017-0108

6. Veale DJ, Fearon U. The Pathogenesis of Psoriatic Arthritis. Lancet (2018) 391(10136):2273–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30830-4

7. Masson W, Lobo M, Molinero G. Psoriasis and Cardiovascular Risk: A Comprehensive Review. Adv Ther (2020) 37(5):2017–33. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01346-6

8. Bangemann K, Schulz W, Wohlleben J, Weyergraf A, Snitjer I, Werfel T, et al. [Depression and Anxiety Disorders Among Psoriasis Patients: Protective and Exacerbating Factors]. Hautarzt (2014) 65(12):1056–61. doi: 10.1007/s00105-014-3513-9

9. Chen M, Jiang Q, Zhang L. The Prevalence of Bipolar Disorder in Autoimmune Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Palliat Med (2021) 10(1):350–61. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-2293

10. Rubino IA, Sonnino A, Pezzarossa B, Ciani N, Bassi R. Personality Disorders and Psychiatric Symptoms in Psoriasis. Psychol Rep (1995) 77(2):547–53. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1995.77.2.547

11. Innamorati M, Quinto RM, Lester D, Iani L, Graceffa D, Bonifati C. Cognitive Impairment in Patients With Psoriasis: A Matched Case-Control Study. J Psychosom Res (2018) 105:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.12.011

12. Hawro M, Maurer M, Weller K, Maleszka R, Zalewska-Janowska A, Kaszuba A, et al. Lesions on the Back of Hands and Female Gender Predispose to Stigmatization in Patients With Psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol (2017) 76(4):648–54.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.040

13. Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment of Psoriasis: A Review. Jama (2020) 323(19):1945–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4006

14. de Jager ME, De Jong EM, Evers AW, Van De Kerkhof PC, Seyger MM. The Burden of Childhood Psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol (2011) 28(6):736–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01489.x

15. Dimitrov D, Szepietowski JC. Stigmatization in Dermatology With a Special Focus on Psoriatic Patients. Postepy Higieny i Medycyny Doswiadczalnej (Online) (2017) 71(0):1115–22. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.6879

16. Dimitrov D, Szepietowski JC. Instruments to Assess Stigmatization in Dermatology. Postepy Higieny i Medycyny Doswiadczalnej (Online) (2017) 71(0):901–5. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.5607

17. Hayes J, Koo J. Psoriasis: Depression, Anxiety, Smoking, and Drinking Habits. Dermatol Ther (2010) 23(2):174–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01312.x

18. Susskind W, Mc GR. The Emotional Factor in Psoriasis. Scott Med J (1959) 4:503–7. doi: 10.1177/003693305900401007

19. Coles RB, Ryan TJ. The Psoriasis Sufferer in the Community. Br J Dermatol (1975) 93(1):111–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb06486.x

20. Armstrong A, Jarvis S, Boehncke WH, Rajagopalan M, Fernandez-Penas P, Romiti R, et al. Patient Perceptions of Clear/Almost Clear Skin in Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis: Results of the Clear About Psoriasis Worldwide Survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol (2018) 32(12):2200–7. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15065

21. Vardy D, Besser A, Amir M, Gesthalter B, Biton A, Buskila D. Experiences of Stigmatization Play a Role in Mediating the Impact of Disease Severity on Quality of Life in Psoriasis Patients. Br J Dermatol (2002) 147(4):736–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04899.x

22. Fortune DG, Richards HL, Kirby B, McElhone K, Markham T, Rogers S, et al. Psychological Distress Impairs Clearance of Psoriasis in Patients Treated With Photochemotherapy. Arch Dermatol (2003) 139(6):752–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.6.752

23. Dimitrov D, Matusiak Ł, Evers A, Jafferany M, Szepietowski J. Arabic Language Skin-Related Stigmatization Instruments: Translation and Validation Process. Adv Clin Exp Med (2019) 28(6):825–32. doi: 10.17219/acem/102617

24. Ginsburg IH, Link BG. Feelings of Stigmatization in Patients With Psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol (1989) 20(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70007-4

25. Ginsburg IH, Link BG. Psychosocial Consequences of Rejection and Stigma Feelings in Psoriasis Patients. Int J Dermatol (1993) 32(8):587–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb05031.x

26. Zięciak T, Rzepa T, Król J, Żaba R. Stigmatization Feelings and Depression Symptoms in Psoriasis Patients. Psychiatr Polska (2017) 51(6):1153–63. doi: 10.12740/pp/68848

27. Jankowiak B, Kowalewska B, Krajewska-Kułak E, Khvorik DF. Stigmatization and Quality of Life in Patients With Psoriasis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) (2020) 10(2):285–96. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00363-1

28. Schmid-Ott G, Jaeger B, Kuensebeck HW, Ott R, Lamprecht F. Dimensions of Stigmatization in Patients With Psoriasis in a "Questionnaire on Experience With Skin Complaints'. Dermatology (1996) 193(4):304–10. doi: 10.1159/000246275

29. Schmid-Ott G, Kuensebeck HW, Jaeger B, Werfel T, Frahm K, Ruitman J, et al. Validity Study for the Stigmatization Experience in Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriatic Patients. Acta Derm Venereol (1999) 79(6):443–7. doi: 10.1080/000155599750009870

30. Schmid-Ott G, Burchard R, Niederauer HH, Lamprecht F, Künsebeck HW. [Stigmatization and Quality of Life of Patients With Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis]. Hautarzt (2003) 54(9):852–7. doi: 10.1007/s00105-003-0539-9

31. Böhm D, Stock Gissendanner S, Bangemann K, Snitjer I, Werfel T, Weyergraf A, et al. Perceived Relationships Between Severity of Psoriasis Symptoms, Gender, Stigmatization and Quality of Life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol (2013) 27(2):220–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04451.x

32. Lu Y, Duller P, Valk P, Evers AWM. Helplessness as Predictor of Stigmatization in Patients With Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatol Psychosomat (2003) 4:146 – 50. doi: urn:nbn:nl:ui:22-2066/187517 doi: 10.1159/000073991

33. Dimitrov D, Matusiak Ł, Szepietowski JC. Stigmatization in Arabic Psoriatic Patients in the United Arab Emirates - A Cross Sectional Study. Postepy Dermatol i Alergol (2019) 36(4):425–30. doi: 10.5114/ada.2018.80271

34. Kowalewska B, Cybulski M, Jankowiak B, Krajewska-Kułak E. Acceptance of Illness, Satisfaction With Life, Sense of Stigmatization, and Quality of Life Among People With Psoriasis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dermatol Ther (2020) 10(3):413–30. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00368-w

35. Łakuta P, Marcinkiewicz K, Bergler-Czop B, Brzezińska-Wcisło L, Słomian A. Associations Between Site of Skin Lesions and Depression, Social Anxiety, Body-Related Emotions and Feelings of Stigmatization in Psoriasis Patients. Postepy Dermatol i Alergol (2018) 35(1):60–6. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2016.62287

36. Jankowiak B, Kowalewska B, Krajewska-Kułak E, Kowalczuk K, Khvorik DF. The Sense of Stigmatization in Patients With Plaque Psoriasis. Dermatol (Basel Switzerland) (2021) 237(4):611–7. doi: 10.1159/000510654

37. Kowalewska B, Jankowiak B, Cybulski M, Krajewska-Kułak E, Khvorik DF. Effect of Disease Severity on the Quality of Life and Sense of Stigmatization in Psoriatics. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol (2021) 14:107–21. doi: 10.2147/ccid.s286312

38. Pichaimuthu R, Ramaswamy P, Bikash K, Joseph R. A Measurement of the Stigma Among Vitiligo and Psoriasis Patients in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol (2011) 77(3):300–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.79699

39. van Brakel WH, Anderson AM, Mutatkar RK, Bakirtzief Z, Nicholls PG, Raju MS, et al. The Participation Scale: Measuring a Key Concept in Public Health. Disabil Rehabil (2006) 28(4):193–203. doi: 10.1080/09638280500192785

40. Alpsoy E, Şenol Y, Bilgiç Temel A, Baysal GÖ, Akman Karakaş A. Reliability and Validity of Internalized Stigmatization Scale in Psoriasis. TURKDERM - Turkish Arch Dermatol Venereol (2015) 49(1):45–9. doi: 10.4274/turkderm.54521

41. Alpsoy E, Polat M, FettahlıoGlu-Karaman B, Karadag AS, Kartal-Durmazlar P, YalCın B, et al. Internalized Stigma in Psoriasis: A Multicenter Study. J Dermatol (2017) 44(8):885–91. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13841

42. Alpsoy E, Polat M, Yavuz IH, Kartal P, Didar Balci D, Karadag AS, et al. Internalized Stigma in Pediatric Psoriasis: A Comparative Multicenter Study. Ann Dermatol (2020) 32(3):181–8. doi: 10.5021/ad.2020.32.3.181

43. Sommer R, Augustin M, Hilbring C, Ständer S, Hubo M, Hutt HJ, et al. Significance of Chronic Pruritus for Intrapersonal Burden and Interpersonal Experiences of Stigmatization and Sexuality in Patients With Psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol (2021) 35(7):1553–61. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17188

44. Lawrence JW, Fauerbach JA, Heinberg LJ, Doctor M, Thombs BD. The Reliability and Validity of the Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire (PSQ) and the Social Comfort Questionnaire (SCQ) Among an Adult Burn Survivor Sample. Psychol Assess (2006) 18(1):106–11. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.106

45. Boehncke WH. Systemic Inflammation and Cardiovascular Comorbidity in Psoriasis Patients: Causes and Consequences. Front Immunol (2018) 9:579. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00579

46. World Health O. Global Report on Psoriasis Vol. 2016. . Geneva: World Health Organization (2016).

47. Zhang X, He Y. The Role of Nociceptive Neurons in the Pathogenesis of Psoriasis. Front Immunol (2020) 11:1984. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01984

48. Costa MC, Paixão CS, Viana DL, Rocha BO, Saldanha M, da Mota LMH, et al. Mononuclear Phagocyte Activation Is Associated With the Immunopathology of Psoriasis. Front Immunol (2020) 11:478. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00478

49. Jankowiak B, Kowalewska B, Krajewska-Kułak E, Kowalczuk K, Khvorik DF. The Sense of Stigmatization in Patients With Plaque Psoriasis. Dermatology (2020) 237(4):611–7. doi: 10.1159/000510654

50. van Beugen S, van Middendorp H, Ferwerda M, Smit JV, Zeeuwen-Franssen ME, Kroft EB, et al. Predictors of Perceived Stigmatization in Patients With Psoriasis. Br J Dermatol (2017) 176(3):687–94. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14875

51. Pearl RL, Wan MT, Takeshita J, Gelfand JM. Stigmatizing Attitudes Toward Persons With Psoriasis Among Laypersons and Medical Students. J Am Acad Dermatol (2019) 80(6):1556–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.014

52. Jankowiak B, Kowalewska B, Fiodaravich Khvorik D, Krajewska-Kułak E, Niczyporuk W. The Level of Stigmatization and Depression of Patients With Psoriasis. Iran J Public Health (2016) 45(5):690–2.

53. Hrehorów E, Salomon J, Matusiak L, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Patients With Psoriasis Feel Stigmatized. Acta Dermato-venereol (2012) 92(1):67–72. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1193

54. Perrott SB, Murray AH, Lowe J, Mathieson CM. The Psychosocial Impact of Psoriasis: Physical Severity, Quality of Life, and Stigmatization. Physiol Behav (2000) 70(5):567–71. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00290-0

55. Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Age and Gender Differences in the Impact of Psoriasis on Quality of Life. Int J Dermatol (1995) 34(10):700–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb04656.x

56. Sommer R, Mrowietz U, Radtke MA, Schäfer I, von Kiedrowski R, Strömer K, et al. What Is Psoriasis? - Perception and Assessment of Psoriasis Among the German Population. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges (2018) 16(6):703–10. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13539

57. Sommer R, Topp J, Mrowietz U, Zander N, Augustin M. Perception and Determinants of Stigmatization of People With Psoriasis in the German Population. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol (2020) 34(12):2846–55. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16436

58. Nijsten T, Margolis DJ, Feldman SR, Rolstad T, Stern RS. Traditional Systemic Treatments Have Not Fully Met the Needs of Psoriasis Patients: Results From a National Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol (2005) 52(3 Pt 1):434–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.862

59. Wang Y, Wang X, Yu Y, Yuan L, Yu X, Yang B. A Retrospective Study to Assess the Efficacy, Safety and Drug Survival of Secukinumab in Plaque Psoriasis Patients in China. Dermatol Ther (2021). doi: 10.1111/dth.15081

60. Guan X, Zhang CL. An Update on Clinical Safety of Adalimumab in Treating Psoriasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Based on 20 Randomized Controlled Trials. J Cosmet Dermatol (2019) 18(5):1550–9. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12868

61. Ichiyama S, Ito M, Funasaka Y, Abe M, Nishida E, Muramatsu S, et al. Assessment of Medication Adherence and Treatment Satisfaction in Japanese Patients With Psoriasis of Various Severities. J Dermatol (2018) 45(6):727–31. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14225

62. Ragnarson Tennvall G, Hjortsberg C, Bjarnason A, Gniadecki R, Heikkilä H, Jemec GB, et al. Treatment Patterns, Treatment Satisfaction, Severity of Disease Problems, and Quality of Life in Patients With Psoriasis in Three Nordic Countries. Acta Derm Venereol (2013) 93(4):442–5. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1485

63. Schaarschmidt ML, Kromer C, Herr R, Schmieder A, Goerdt S, Peitsch WK. Treatment Satisfaction of Patients With Psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol (2015) 95(5):572–8. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2011

64. Zachariae R, Zachariae H, Blomqvist K, Davidsson S, Molin L, Mørk C, et al. Self-Reported Stress Reactivity and Psoriasis-Related Stress of Nordic Psoriasis Sufferers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol (2004) 18(1):27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00721.x

65. Makara-Studzińska M, Ziemecki P, Ziemecka A, Partyka I. [The Psychological and Social Support in Patients With Psoriasis]. Polski Merkuriusz Lekarski Organ Polskiego Towarzystwa Lekarskiego (2013) 35(207):171–4.

66. Augustin M, Mrowietz U, Luck-Sikorski C, von Kiedrowski R, Schlette S, Radtke MA, et al. Translating the WHA Resolution in a Member State: Towards a German Programme on 'Destigmatization' for Individuals With Visible Chronic Skin Diseases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol (2019) 33(11):2202–8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15682

Keywords: stigmatization, psoriasis, questionnaires, biologics, immunology

Citation: Zhang H, Yang Z, Tang K, Sun Q and Jin H (2021) Stigmatization in Patients With Psoriasis: A Mini Review. Front. Immunol. 12:715839. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.715839

Received: 27 May 2021; Accepted: 12 August 2021;

Published: 15 November 2021.

Edited by:

Nobuo Kanazawa, Hyogo College of Medicine, JapanReviewed by:

Daniella Schwartz, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH), United StatesCopyright © 2021 Zhang, Yang, Tang, Sun and Jin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hongzhong Jin, amluaG9uZ3pob25nQDI2My5uZXQ=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.