Corrigendum: Nasal Administration of Anti-CD3 Monoclonal Antibody (Foralumab) Reduces Lung Inflammation and Blood Inflammatory Biomarkers in Mild to Moderate COVID-19 Patients: A Pilot Study

- 1Ann Romney Center for Neurologic Diseases, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

- 2Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

- 3Santa Casa de Misericordia de Santos, Santos, Brazil

- 4Tiziana LifeScience, Doylestown, PA, United States

- 5Department of Radiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Background: Immune hyperactivity is an important contributing factor to the morbidity and mortality of COVID-19 infection. Nasal administration of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody downregulates hyperactive immune responses in animal models of autoimmunity through its immunomodulatory properties. We performed a randomized pilot study of fully-human nasal anti-CD3 (Foralumab) in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 to determine if its immunomodulatory properties had ameliorating effects on disease.

Methods: Thirty-nine outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19 were recruited at Santa Casa de Misericordia de Santos in Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Patients were randomized to three cohorts: 1) Control, no Foralumab (n=16); 2) Nasal Foralumab (100ug/day) given for 10 consecutive days with 6 mg dexamethasone given on days 1-3 (n=11); and 3) Nasal Foralumab alone (100ug/day) given for 10 consecutive days (n=12). Patients continued standard of care medication.

Results: We observed reduction of serum IL-6 and C-reactive protein in Foralumab alone vs. untreated or Foralumab/Dexa treated patients. More rapid clearance of lung infiltrates as measured by chest CT was observed in Foralumab and Foralumab/Dexa treated subjects vs. those that did not receive Foralumab. Foralumab treatment was well-tolerated with no severe adverse events.

Conclusions: This pilot study suggests that nasal Foralumab is well tolerated and may be of benefit in treatment of immune hyperactivity and lung involvement in COVID-19 disease and that further studies are warranted.

Introduction

The new beta-coronavirus Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS- CoV-2) has infected over 200 million people world-wild and represents the greatest global public health crises since the pandemic influenza outbreak of 1918 (1, 2). Clinical trials have focused on anti-viral therapy (3–5) and treatment to modulate the immune system including corticosteroids (6, 7), convalescent plasma (8, 9), immunoglobulins (10, 11) and tocilizumab (12–14).

SARS-CoV-2 infection involves prominent immune changes including infiltration of monocytes to the lungs associated with elevated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines known as cytokine storm (15–17). The COVID-19 hyperinflammatory syndrome can led to multiorgan failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome that represents the leading cause of mortality in COVID-19 (17). Increased cytotoxic follicular helper cells (TFH) and cytotoxic T helper cells and a decrease in SARS-CoV-2-reactive Tregs were observed in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. A strong cytotoxic TFH response was observed early in the illness (18). A reduction of Tregs could be an important contributing factor to the hyperactive immune system and lung damage in COVID-19 patients. This is consistent with animal studies in which Treg depletion led to acute encephalitis and increased mortality in mice infected with murine coronavirus (19).

Considering that an excessive immune response plays an important role in COVID-19 infection, we hypothesized that enhancing T regulatory cells (Treg) could be of benefit in SARS-CoV-2 infection (20–22). Tregs play a key role in maintaining tolerance to self-antigens and in suppression of excessive immune responses in autoimmune conditions (23, 24). We have been investigating mucosal administration of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) as a novel approach to induce Tregs and suppress inflammation in models of autoimmunity (25–28). We have shown that nasal anti-CD3 induces IL-10 dependent Tregs that suppress inflammation and disease progression in several inflammatory diseases models including experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, lupus and arthritis (26, 29).

We are developing nasal Foralumab, a fully human anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb), for treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS). In preparation for a clinical trial of nasal Foralumab in SPMS we conducted a dose-ranging safety trial in healthy volunteers at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Foralumab had previously been tested in subjects with colitis given intravenously (30). We found that nasal Foralumab was safe and was immunologically active as measured by suppression of CD8+ T cell responses and induction of CD4+ IL-10 responses (unpublished). The characterization of the immune response to nasal anti-CD3 in healthy volunteers is ongoing. Given the crises caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the immediate need for novel approaches to treat the illness, we elected to perform a pilot trial of nasal Foralumab in COVD-19 subjects since we had found that Foralumab was safe in healthy individuals and had immunomodulatory effects.

We chose to treat mild to moderate COVID-19 subjects who were outpatients seen at the Santa Casa de Misericordia de Santos Hospital in Brazil. A dose of 100ug/day for 10 consecutives days was selected based on our experience with nasal Foralumab in healthy individuals. We randomized subjects to receive no treatment vs. treatment with Foralumab/Dexa vs. treatment with Foralumab alone. The measurement of inflammatory blood markers IL-6, CRP and D-dimer was used as the primary outcome.

Methods

Patient Recruitment and Trial Design

Patients with flu-like symptoms consistent with COVID-19 infection were evaluated at Santa Casa de Misericordia de Santos Hospital emergency ward and screened for the study. Inclusion criteria comprised 1) a positive RT-PCR COVID test; and 2) mild to moderate disease with an oxygen saturation over 93% and no requirement for oxygen. Exclusion criteria included (1) infectious disease: syphilis, hepatitis and HIV; (2) Pregnancy; (3) less than 18 years old; (4) chronic kidney disease; (5) cancer or other immunodeficiencies; and (6) elevated glycated hemoglobin for patients with diabetes. Of 60 patients screened for the study, 39 patients were enrolled. 10 were negative for COVID by PCR and 11 elected not to participate after screening.

Patients were randomized into three cohorts: no Foralumab treatment, nasal Foralumab/Dexa, and nasal Foralumab alone. Treatment was administered in an open label fashion. Patients randomized to Foralumab treatment were visited by a nurse for daily drug administration. 50μg of Foralumab was administered by nose drop to each nostril (total 100μg). Patients receiving dexamethasone received 6 mg of oral dexamethasone on days 1-3. Patients in the control group did not receive foralumab. All arms were allowed to continue background antibiotics. Corticosteroids were not given per protocol but patients were able to access them through self or other healthcare provider outside the hospital.

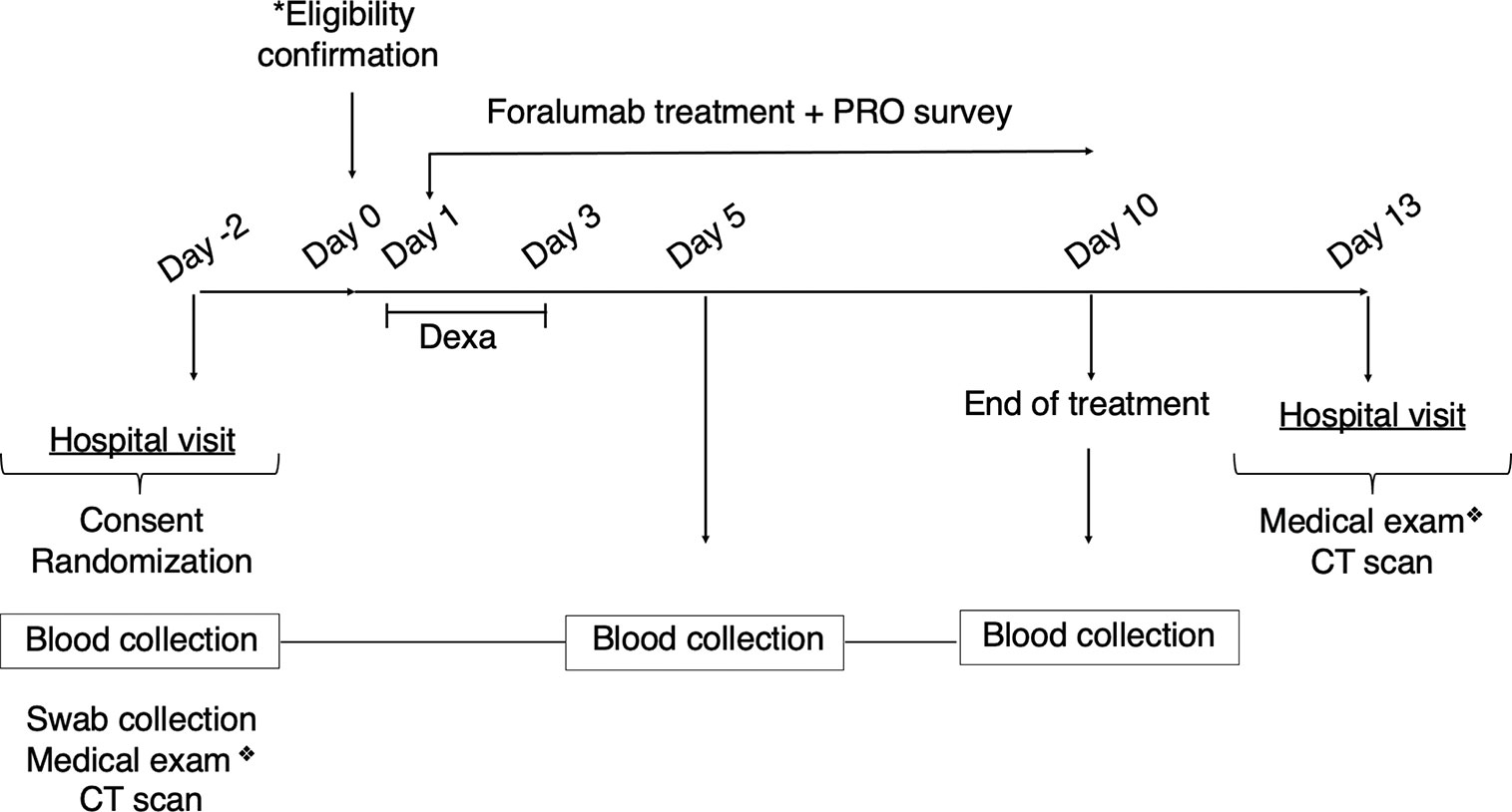

Foralumab treatment was given for 10 consecutive days. Patients returned to hospital at day 13 for clinical exam and lung CT scan follow up. All patients had a lung CT scan prior to entering the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Clinical Study Design. Symptomatic patients were consented and randomized on day -2. Blood and nasopharyngeal swab collection, CT scans and medical exam was also performed at day -2. *Eligibility was confirmed on day 0 (SARS-CoV-2 PCR positive results, infectious disease negative results). Foralumab treatment started at day 1 for 10 days. Dexamethasone (6mg/day) was given on days 1-3 to Foralumab/Dexa group. PRO data was collected daily during treatment (day 1 to day 10) and symptomatology was accessed during medical exam at the beginning and completion of study (day -2 and day 13). Blood collection for biomarkers follow-up was performed at day 5 and day10. Patient returned to the hospital for clinical exam and CT scan follow up on day 13. ❖ Symptomatology and drug use assessment. CT, computerized tomography; PRO, patient reported outcome.

Patients completed a daily clinical outcome questionnaire to assess 15 common COVID-19 related symptoms designed based on FDA guidelines (see below). This scoring system generated a numeric value for each day. Overall wellness was accessed using Baker Wong scale for pain assessment. Patients allocated to the control group did not receive placebo and thus were not visited by the clinical team apart from blood collection on days 5 and 10. For these patients, the daily survey was conducted by phone.

Study Approval

The study was conducted according to the Brazilian regulatory agency for clinical research and good clinical practice guidelines and declaration of Helsinki. Ethical committee approval was granted by Universidade Metropolitana de Santos – UNIMES (CAAE: 38056120.1.0000.5509). The investigators designed the trial, collected the data, and performed the analysis. In addition to providing Foralumab, Tiziana Life Sciences also provided financial assistance to the trial but did not participate in statistical analysis or data interpretation.

Laboratory Tests

Nasopharyngeal swabs were used to screen for COVID-19 by RT-PCR. Clinical laboratory tests were performed at S’agapo Laboratory and included: complete blood counts, IL-6, D-dimer, CRP, COVID-19 Serology, HIV, syphilis, pregnancy, hepatitis, and glycated hemoglobin. White blood counts were measured by flow cytometry and impedance. CRP and glycated hemoglobin were measured by turbidimetry, D-dimer was measured by immunoturbidimetry, and IL-6 was measured by chemiluminescence. IL-18 was measured using ProcartaPlex multiplex assay (Thermo Fisher, EPX450-12171-901).

Lung CT and Analysis

Lung CT scan was performed at Santa Casa de Misericordia de Santos Hospital using a 16 channel (Toshiba-Alexion) CT scanner. Contrast was not used. Scan coverage was from apex of the lung to the level of bilateral adrenals. Tube voltage was between 100-120Kv. Parenchyma slide thickness was 1mm.

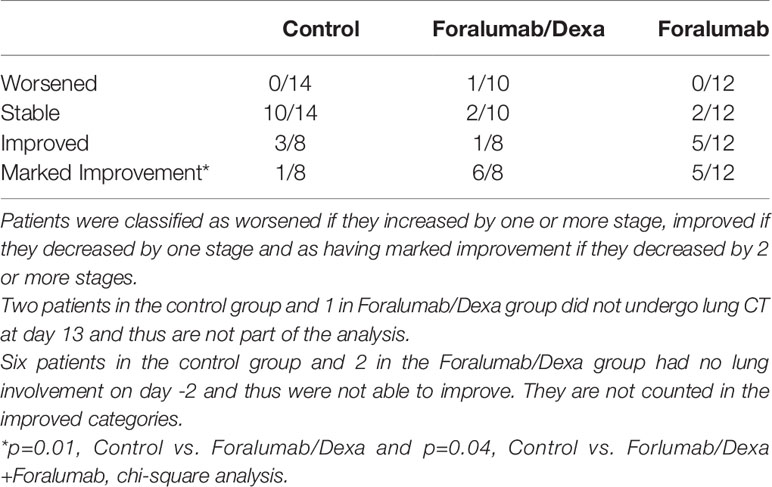

Lung injury consisted of patchy shadowing and ground glass appearance which was graded on a scale of 0 to 4 as follows: 0 = no detectable abnormalities or lung involvement <5%; Stage 1 = mild lung involvement involving approximately 10% of lung area, Stage 2= moderate lung involvement with patchy shadowing and ground glass lesions involving approximately 25% of lung area, Stage 3 = severe confluent ground glass lesions and consolidation involving 25% to 50% of lung area; Stage 4 very severe ground glass lesions and consolidation involving more than half of the lung area.

Baseline lung CT scans obtained on day -2 were compared to scans obtained on day 13. Patients were classified as worsened if they increased by one or more stage, improved if they decreased by one stage and as having marked improvement if they decreased by 2 or more stages. Patients were stable if they did not change stages. Lung CT analysis was performed by three radiologists in a blinded fashion.

Patient Reported Outcomes (PRO) and Medical Report Outcome

Patient reported outcomes were accessed daily using a symptomatology survey based on FDA guidelines (Assessing COVID-19-related symptoms in Outpatient Adult and Adolescent Subjects in Clinical Trials of Drug and Biological Products for COVID-19 Prevention or Treatment) (https://www.fda.gov/media/142143/download). PRO consisted of 15 questions with the following response system: (1) Anosmia (loss of smell): 0=normal, 3=reduced, 5=completely lost). (2) Dysgeusia (loss of taste): 0=normal, 3=reduced, 5=completely lost). (3) Cough: 0=not present, 3 =present some time, 5=present more than half the day. (4) Headache: 0=not present, 3=present some time, 5=present more than half the day); (5) Throat ache: 0=not present, 3=moderate, hurts when swallowing, 5=strong, intense pain when swallowing. (6) Dyspnea: 0=not present, 3= moderate, some lack of air, 5=strong, difficult breathing. (7) Nausea/Vomiting: 0=not present, 3= nausea without vomiting, 5=vomiting. 8) O2 Saturation: 0= > 95, 3 = 94-95%, 5 = 91-93%. (9) Diarrhea was evaluated according to the Bristol Scale (ref) 0=type 0-4, 3=type 5 or 6, 5=type 7. (10) Rhinorrhea: 0=not present, 3=nose with mucus, 5=runny nose (liquid)); (11) Abdominal pain: 0=not present, 3=moderate, 5=intense). (12) Myalgia: 0=not present, 3=moderate, 5=intense (full body). (13) Fever: 0=not present, 3 = 37-38C, 5= >38.0C. (14) Conjunctivitis: 0=absent, 5=present. (15) Appetite: 0=normal, 3=reduced, 5=completely lost. General well-being (how you are feeling today) was assessed using the Baker Wong scale for pain assessment (0-10). The maximum possible score was 85.

We also accessed COVID-19 symptoms reported at day -2 as compared to symptomatology at day 13. For this, we stratified patient reported symptoms according to Domains as follows: Domain 1 (weakness, fatigue, inappetence, body ache, backpain); Domain 2 (fever, chills, sweating); Domain 3 (nausea, diarrhea, epigastric pain); Domain 4 (ageusia); Domain 5 (anosmia); Domain 6 (runny nose, odynophagia, sneezing); Domain 7 (headache, anxiety, eye pain, dizziness); Domain 8 (cough, dyspnea, chest pain). Patient was scored for one symptom in each domain.

Statistical Analysis

The demographic characteristics of the three treatment groups were summarized using means/standard deviations for continuous outcomes and number/percentages for dichotomous outcomes. The patient reported outcomes were measured daily for 10 days, and the change with time in each treatment group was estimated using a linear mixed model with a random intercept and slope. The fixed effects in the model were two indicators for the Foralumab groups, day, and two day by treatment group interaction terms. The estimated slope in each treatment group, and the pairwise group comparison of the slopes are reported. For the presence of symptoms at each domain, the number/percentage for each domain was calculated prior to starting the treatment and at day 10, and the percentage was compared between the treatment groups using a chi-squared test. The total number of domains at each time point was compared across the treatment groups using a Kruskal-Wallis test. For biomarkers, we used linear mixed effects regression model with a random intercept to compare the three groups in terms of change from baseline (day -2) at day 5 and day 10. The primary analysis was the three-group comparison, and this was completed using appropriate contrasts from the linear mixed model. Comparisson between the treatment groups for lung injury (Lung CT scan) was calculated using a chi-squared test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with R software and graph prism was used for graph representation.

Results

Patients

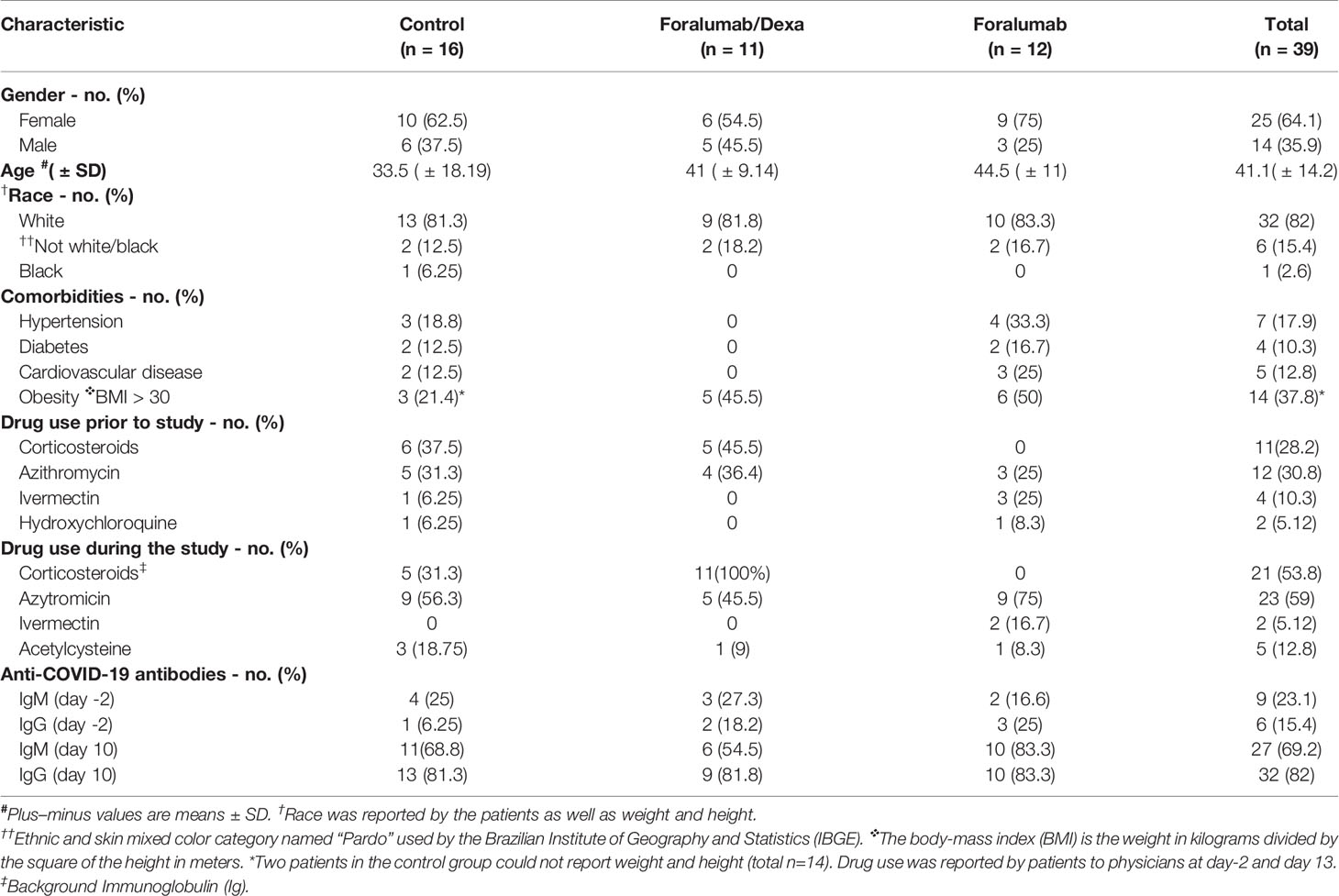

The baseline demographics are shown in Table 1. Thirty-nine patients participated in the study, 64.1% females (n=25) and 35.9% males (n=14). The mean age of subjects was 41.1 ± 14.2. with control subjects 33.5, Foralumab/Dexa subjects 41, and Foralumab subjects 44.5. The majority of patients were white. Twenty-three (41%) patients had one or more comorbidities with the most common being obesity. Obesity (BMI>30 Kg/m2) occurred in 37.8% of patients and was observed in all groups (31). Grade 2 obesity was observed in one control subject and one subject in the Foralumab group. Eleven patients (28.2%) reported the use of corticosteroids (prednisolone or dexamethasone) prior to entry in the study. Patients that did not use corticosteroids prior to the study were randomized to the control or the Foralumab group. Patients that used corticosteroids prior to the study were randomized to the control or Foralumab/Dexa group.

Drug use during the study: Twenty-three patients (58.9%) received azithromycin prescribed their physicians. Two patients took the anti-helminth drug ivermectin and 5 patients took the drug acetylcysteine. At the 13day follow-up visit, 5 patients in control group reported taking up to 5 days of off label steroids during the study.

IgM and IgG anti-COVID antibodies were measured on day -2 and day 10 of the study. Nine subjects (23.1%) had anti-COVID IgM antibodies on day -2 which increased to 27 subjects (69.2%) at day 10. Six subjects (15.4%) had anti-COVID IgG antibodies on day -2 which increased to 32 subjects (82%) at day 10. No differences in the development of IgM or IgG antibodies were observed between the groups.

Patient Reported Outcomes (PRO)

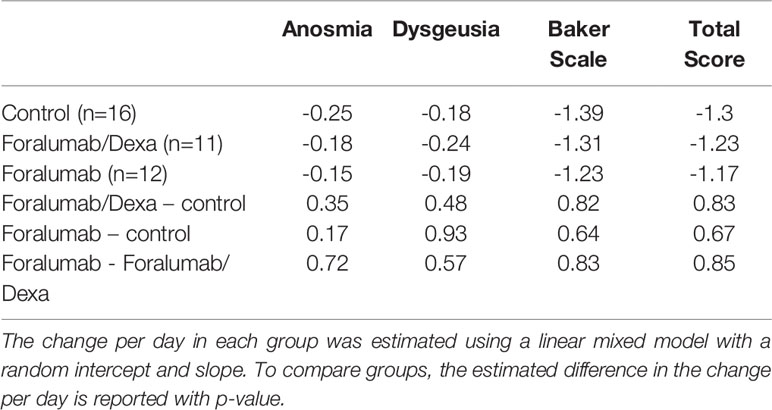

Patients completed a daily clinical outcome questionary to assess 15 common COVID-19 related symptoms. There were no differences in patient reported outcome among groups (Table 2).

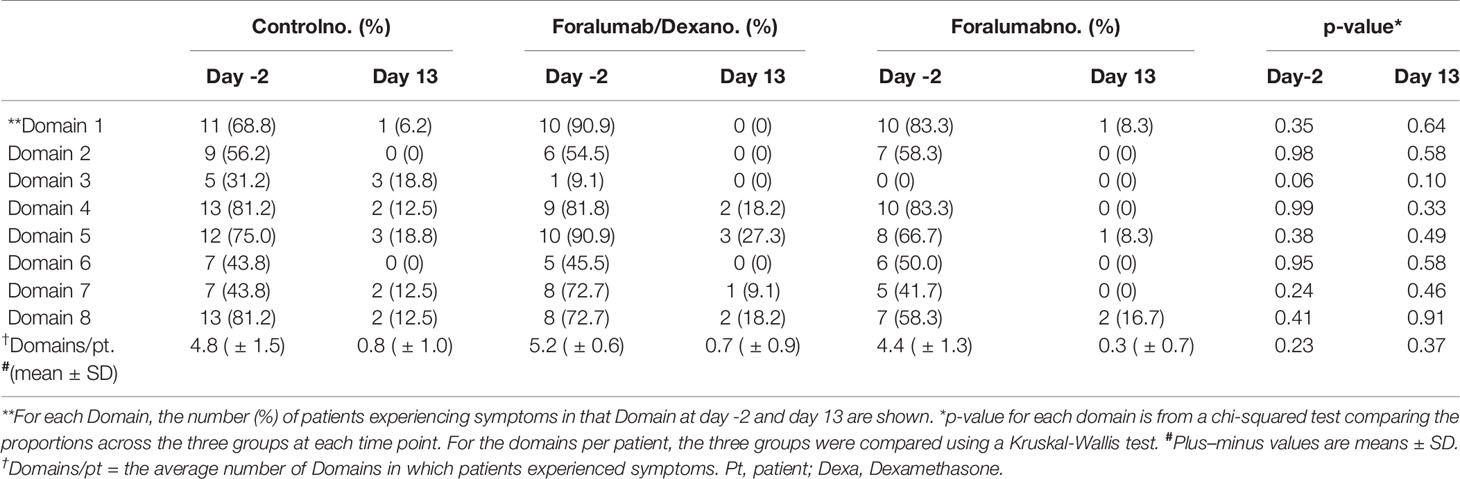

COVID Symptomatology

We compared patient symptomatology at day -2 vs. day 13 according to the 8 Domains (eg., fever, gastrointestinal symptoms, and respiratory symptoms) described in methods above. At day -2, patients had been experiencing symptoms for an average of 6 days in an average of 5 Domains. As shown in Table 3, most patients improved during the course of the study with no major differences between the treatment groups. At the end of the study 23 of 39 patients (58.9%) were asymptomatic; 8 of 16 (50%) in the control group, 6 of 11 (54.5%) in the Foramulab/Dexa group and 9 of 12 (75%) in the Foralumab group. Among the 16 patients that remained symptomatic at the end of the study, anosmia (Domain 5) and cough (Domain 8) were the most common symptoms. There were anecdotal reports of rapid recovery from anosmia and ageusia in both Foralumab treated groups. Of note, our study was not designed to determine long-term effects of Foralumab on COVID-19 symptomatology.

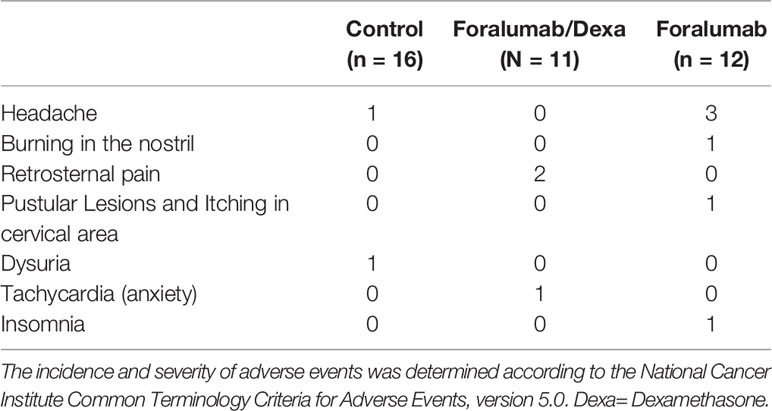

Adverse Events

Eleven patients (28%) experienced an adverse event including headache (n=4) burning in the nostril (n=1), retrosternal pain (n=2), pustular lesions and itching in cervical area (n=1), dysuria (n=1), tachycardia associated with anxiety (n=1) and insomnia (n=1) (Table 4). No serious adverse events were observed, and all patients completed the study. The incidence and severity of adverse events was determined according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0.

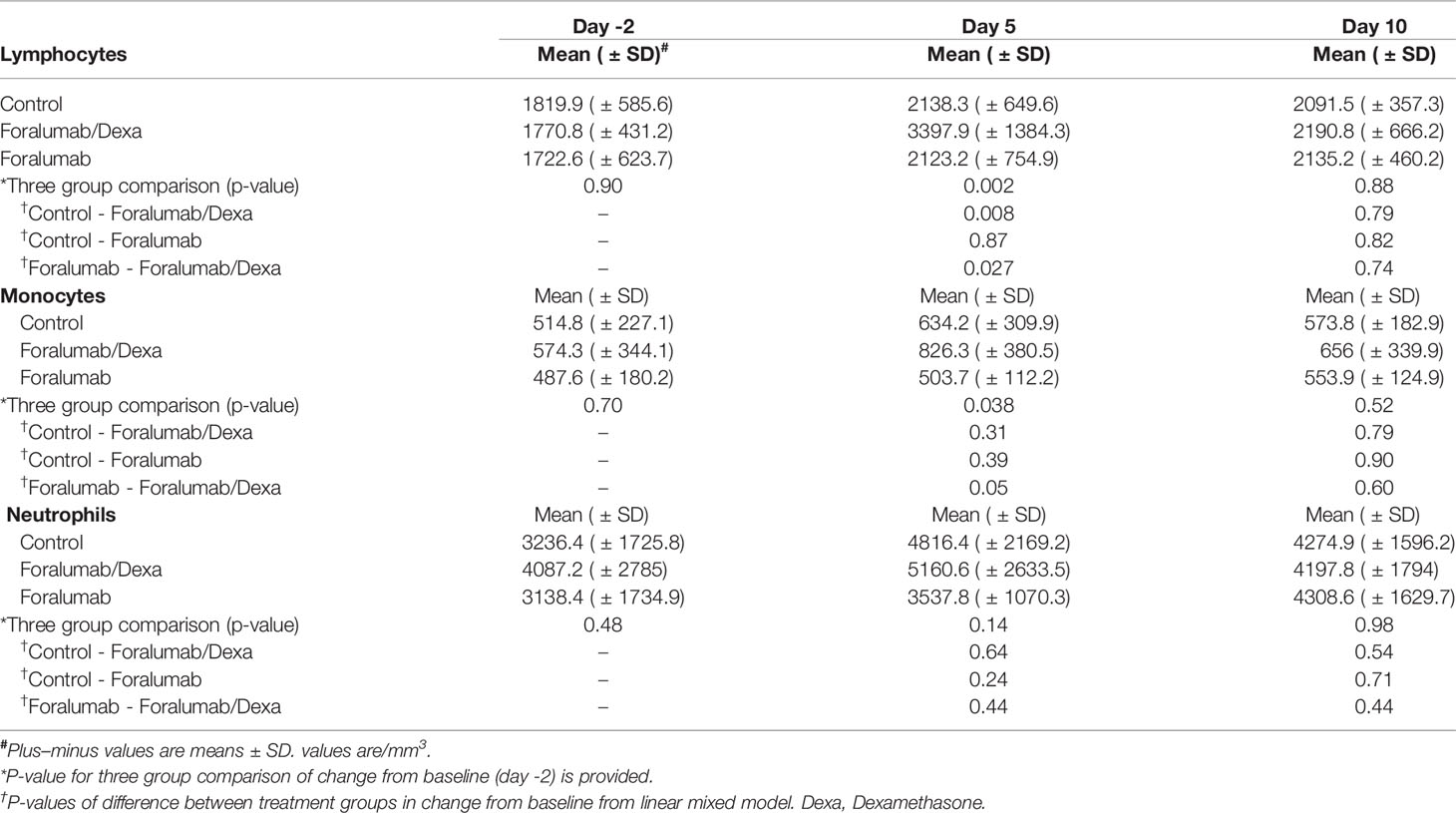

White Blood Cells

Lymphocyte, monocyte and neutrophil counts were obtained on days -2, 5 and 10 (Table 5). No reduction in white blood cells was observed with treatment. Lymphocytes and monocytes were increased in the Foralumab/Dexa cohort on day 5; p=0.002 and p=0.038, respectively but not on the last day on dosing. Lymphocytes were not elevated significantly above Baseline in the foralumab alone group or the control group. No differences in neutrophil counts were observed. In three group comparisons, a difference was observed in the control vs. the Foralumab/Dexa group and the Foralumab vs. Foralumab/Dexa for lymphocytes at day 5; p= 0.008 and p=0.027, respectively.

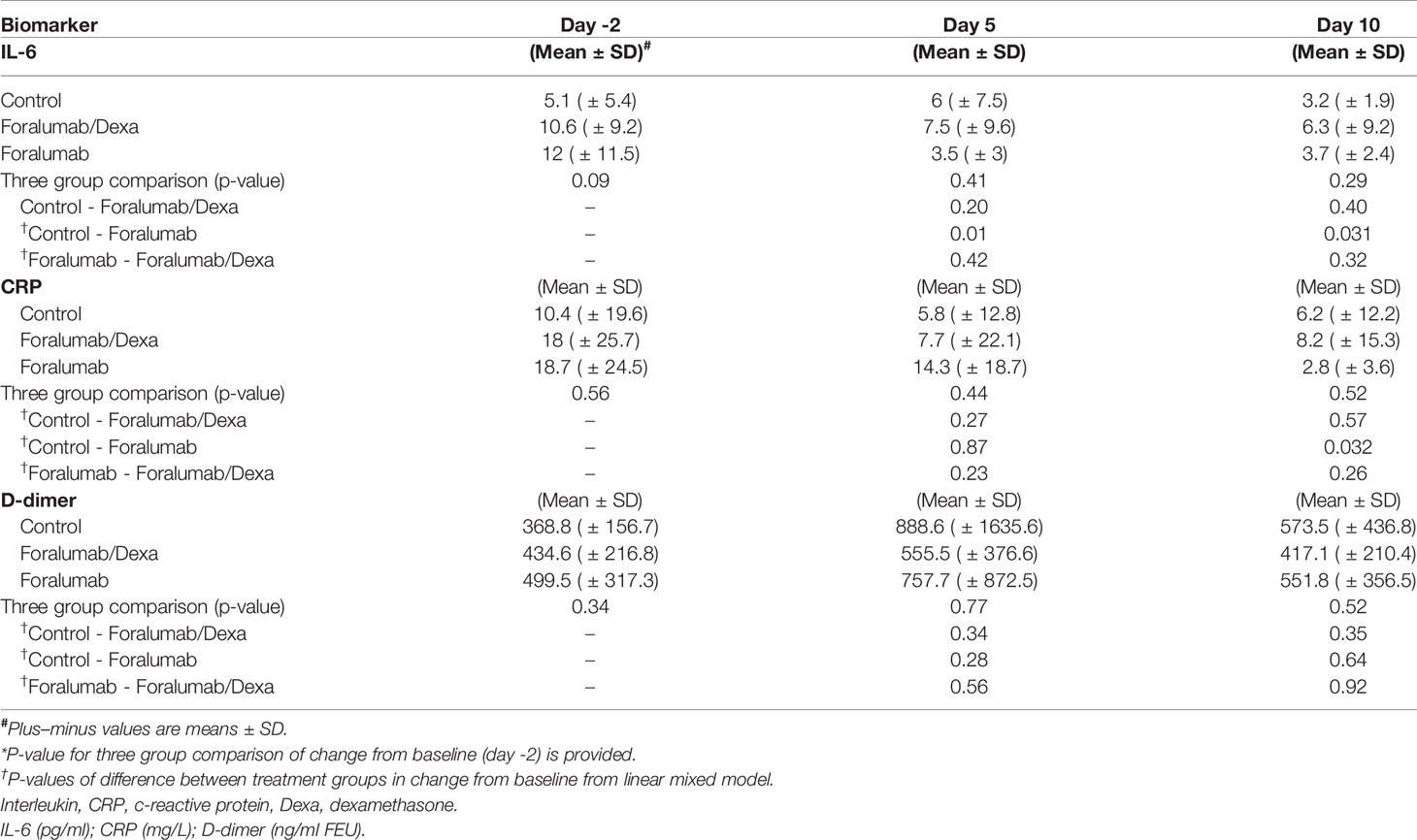

Inflammatory Biomarkers

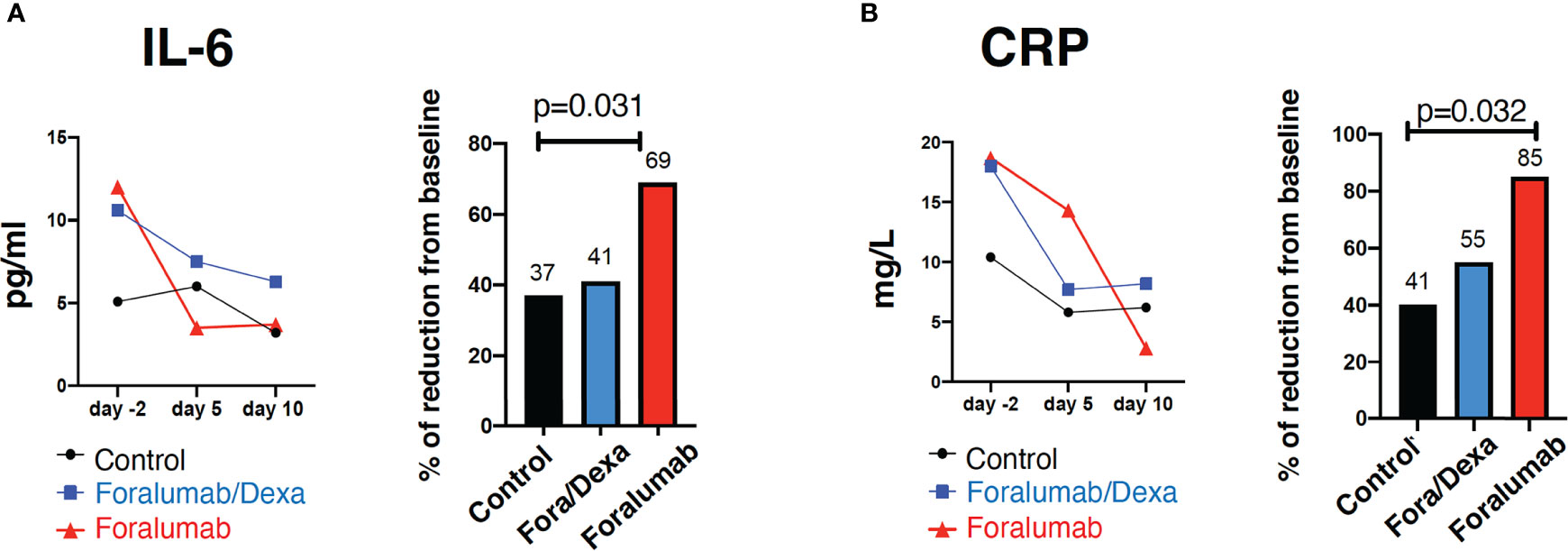

We quantified serum levels of IL-6, CRP and D-dimer on days -2, 5 and 10. IL-6 and CRP levels may be linked to worse outcome in COVID-19 (32, 33) and anti-IL-6 therapy is being investigated as immunotherapy in COVID (34–36). As shown in Figure 2 Foralumab resulted in a 69% reduction in IL-6 levels at day 10 (p=0.031) and 85% reduction in CRP at day 10 (p=0.032).

Figure 2 Blood inflammatory markers IL-6 and C-reactive protein. Serum quantification and percentage of reduction of (A) IL-6 and (B) C-reactive protein. Linear regression was used to compare three-group comparison of each time point. A linear mixed model with a random intercept was used to baseline (day -2) comparison. Percent of baseline was compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test. p= <0.05. IL, Interleukin, CRP, c-reactive protein, Dexa, dexamethasone.

As shown in Table 6, three group comparisons showed a difference between Control vs Foralumab at a day 5 (p=0.01) and at day 10 (p=0.031) and in CRP on day 10 (p=0.032). No significant differences were observed in D-dimer serum levels among groups. We also measured serum IL-18. Paired analysis showed that IL-18 in the Foralumab group was 46.1 (± 15.5) pg/ml before treatment and 37.6 (± 12.6) pg/ml after treatment (p=0.054). There were no significant changes in serum IL-18 following treatment in the Foralumab/DEXA (p=0.16) or Control groups (p=0.43).

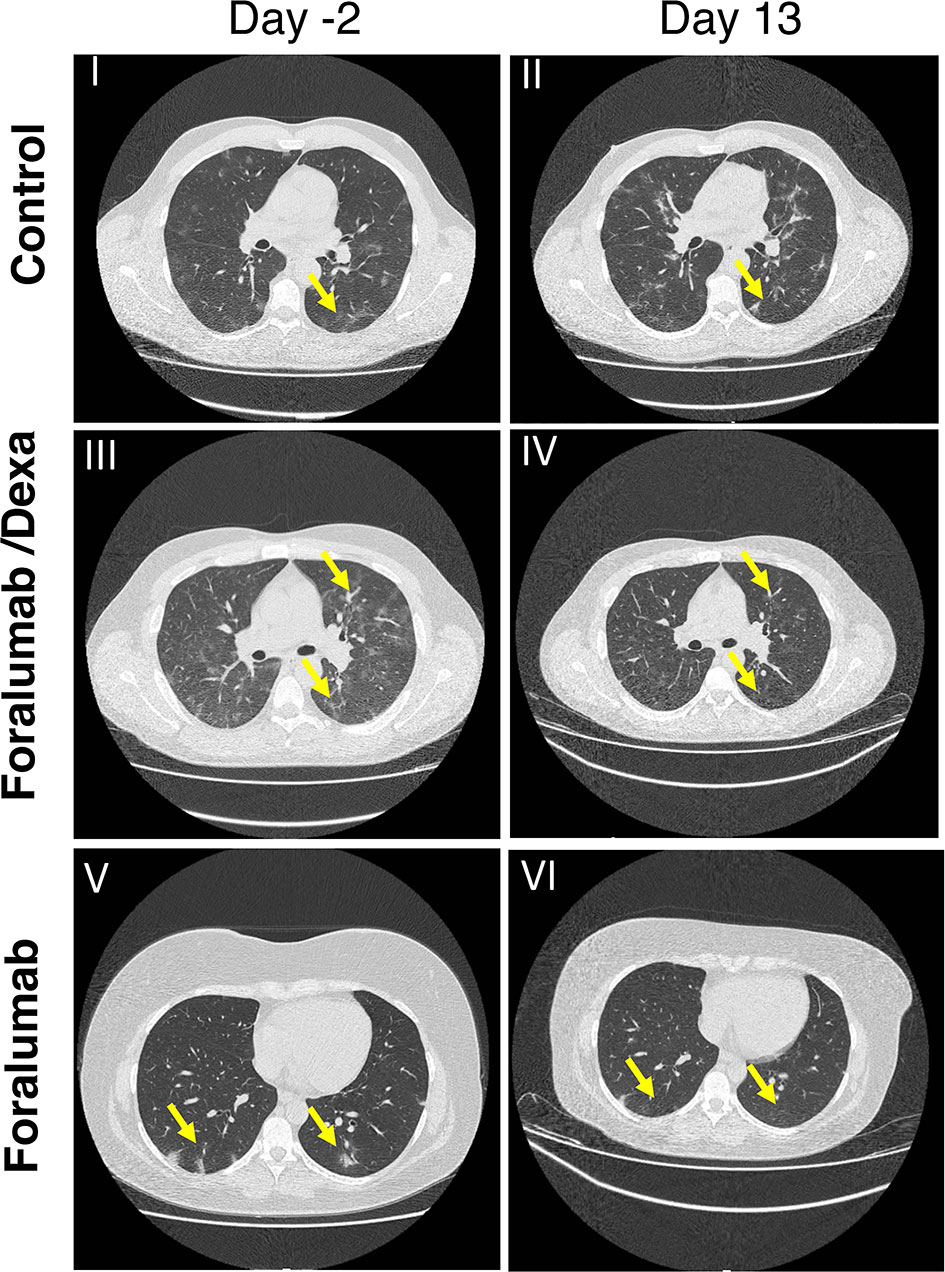

Lung CT Analysis

Computerized tomography (CT) of the lung was obtained prior to treatment at day -2 and at study completion on day 13 and analyzed as described in the methods. Lung CT scan was not obtained in 2 control subjects and 1 Foralumab/Dexa subject. Each patient was classified as worse, stable, improved or markedly improved. As shown in Table 7, 1/10 of the Foralumab/Dexa subjects worsened. 10/14 control subjects, 2/10 Foralumab/Dexa subjects and 2/12 Foralumab subjects remained stable. Regarding improvement, because 6 patients in the control group and 2 in the Foralumab/Dexa group had no lung involvement on day -2, they were not able to improve. Thus, improvement occurred in 3/8 control, 1/8 Foralumab/Dexa and 5/12 in the Foralumab group. Marked improvement was observed in 1/8 control, 6/8 in the Foralumab/Dexa and 5/12 in the Foralumab group. Thus, marked improvement was predominantly observed in subjects receiving Foralumab/Dexa or Foralumab alone. Control vs. Foralumab/Dexa, p=0.01 and Control vs. Forlumab/Dexa+Foralumab, p=0.04 (chi-square analysis) (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Lung CT Scan: CT chest in COVID-19 patients by treatment group. I-II: Axial images in a control patient shows widespread ground glass opacity (anterior and posterior segments of bilateral upper and right middle lobes) two days prior to treatment (I) showing significant progression at 13 days follow up (II). III-IV: Axial images in a patient treated with Foralumab/Dexa showing both widespread ground glass opacity in the anterior and posterior segments and consolidation in both lower lobes (III) demonstrating partial resolution on the 13 follow up day scan (IV). V-VI: Axial images in a patient who received Foralumab showing ground glass opacity of posterior segments of lungs (V) demonstrating interval resolution on 13 follow up day scan (VI). Dexa, dexamethasone.

Discussion

Intravenous anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody has been used to treat graft rejection (37) and is being investigated in type 1 diabetes (38). Intravenous anti-CD3 modulates CD3 from the T cell surface and causes a reduction of lymphocytes whereas mucosal (nasal and oral) anti-CD3 acts by inducing regulatory T cells at the mucosal surface that then act systemically (39). In animal studies no reduction in lymphocytes has been observed following nasal anti-CD3 (40). Consistent with this, no reduction in lymphocyte counts was observed in COVID-19 patients treated with 100μg nasal anti-CD3 for 10 days or in healthy volunteers treated with 250μg Foralumab for 5 consecutive days (unpublished). In our study, no significant adverse events were observed and treatment with Foralumab was generally well tolerated.

As this was an open label exploratory clinical study, it was not specifically powered for statistical analysis and the major limitations of the study are its small size and the over the counter use of corticosteroids.

Systemic corticosteroids are commonly used to treat COVID-19 patients who are hospitalized and have decreased oxygen saturation and international guidelines recommend moderate doses of dexamethasone for a short period of time when hemodynamic parameters are compromised (7, 41). The use of corticosteroid treatment for noncritically ill is controversial (42).

In this pilot trial, we tested the effect of Foralumab alone vs. Foralumab given with a three-day course of dexamethasone. Foralumab/Dexa appeared to be more effective in improving lung inflammation than Foralumab alone. Foralumab alone was more effective than Foralumab/Dexa and controls in decreasing inflammatory blood markers at day 10 as measured in a three group comparison.

Given the anti-inflammatory effects of Foralumab and the positive safety profile of Foralumab treated COVID-19 patients, further studies are warranted. Of particular interest would be the degree to which nasal Foralumab might benefit hospitalized subjects with more severe disease. In addition, since it can easily be administered as an outpatient, it could be used on non-hospitalized subjects with COVID-19 and may be of benefit to speed recovery and prevent disease worsening and hospitalization. Because the anti-inflammatory effect of the nasally administered Foralumab is through the modulation of the immune system and not by directly targeting COVID-19, if effective, it would be expected to be useful for newly identified COVID-19 variants and could be given in combination with other drugs.

Immunomodulatory agents that enhance regulatory immune responses are believed to play an important role in modulating disease in patients with COVID-19 by suppressing hyperreactive immune responses (12–14, 43). In animals, we have shown that nasal anti-CD3 modulates the immune response by inducing IL-10-producing Tregs (26, 29) without the occurrence of potential adverse events associated with parenteral anti-CD3 therapy (39). Although we hypothesize that the effect of nasal Foralumab in COVID-19 patients is related to the induction of Tregs, Treg function was not measured in the current study.

In summary, although we found positive effects of nasal Foralumab as measured by decreases in IL-6 and CRP and improvement on lung CT scans in mild to moderate COVID-19 patients, our results must be taken with caution and we cannot conclude that nasal Foralumab has a beneficial effect in COVID-19 until larger studies are performed. Nonetheless, our results have identified a novel immunomodulatory therapy that potentially could have a significant benefit in patients suffering from COVID-19.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Universidade Metropolitana de Santos – UNIMES (CAAE: 38056120.1.0000.5509). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

TM designed the study, led and monitored this clinical study, and wrote the manuscript. KM designed the study, clinically monitored the study, and performed Lung CT analysis. GD and TS recruited patients, performed clinical exams, registered drug intake and medical past history. RGD, monitored the study and helped collect BMI data. FP and AC supported patient recruitment. MS performed biomarkers assays. CMB-A participated in drug development. GK performed serum and plasma collection. JJ and VP performed drug stability assays. SI and KC performed Lung CT scan analysis. BH performed statistical analysis. RR designed the study and reviewed manuscript. RAD helped supervise the study at Santa Casa de Santos Hospital. KS helped design the study and reviewed the manuscript. HW designed the study and helped write the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

JJ, VP and KS are employees of Tiziana, Life Sciences. HW is chair of the Scientific Advisory Board of Tiziana and received consulting fees and stock options from the company. TM and KM received consulting fees from the company.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients that voluntarily participated in this study. Special thanks to the nursing team: Joao Neto, Fernanda Santos, Bianca Gobbo, Cristiane Souza and Gabriel do Nascimento for their dedicated and hard work. We thank Rodrigo Morrone from S’agapo Laboratory for his technical help and support. We thank Davide Mangani, Sandro Perazzio and Carolina Lazari for their scientific input in the clinical study. We thank the clinical monitors and coordinators from Intrials team. We thank Neil Graham for reviewing the manuscript.

References

1. Jones N. How COVID-19 is Changing the Cold and Flu Season. Nature (2020) 588(7838):388–90. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03519-3

2. Durrheim DN, Baker MG. COVID-19-a Very Visible Pandemic. Lancet (2020) 396(10248):e17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31675-5

3. Yin W, Mao C, Luan X, Shen DD, Shen Q, Su H, et al. Structural Basis for Inhibition of the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase From SARS-CoV-2 by Remdesivir. Science (2020) 368(6498):1499–504. doi: 10.1126/science.abc1560

4. Carmona-Bayonas A, Jimenez-Fonseca P, Castanon E. A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Covid-19. N Engl J Med (2020) 382(21):e68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2008043

5. Stower H. Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Severe COVID-19. Nat Med (2020) 26(4):465. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0849-9

6. Ledford H. Coronavirus Breakthrough: Dexamethasone is First Drug Shown to Save Lives. Nature (2020) 582(7813):469. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01824-5

7. Tomazini BM, Maia IS, Cavalcanti AB, Berwanger O, Rosa RG, Veiga VC, et al. Effect of Dexamethasone on Days Alive and Ventilator-Free in Patients With Moderate or Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and COVID-19: The CoDEX Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA (2020) 324(13):1307–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17021

8. Joyner M, Wright RS, Fairweather D, Senefeld J, Bruno K, Klassen S, et al. Early Safety Indicators of COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma in 5,000 Patients. J Clin Invest (2020) 130(9):4791–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI140200

9. Yigenoglu TN, Hacibekiroglu T, Berber I, Dal MS, Basturk A, Namdaroglu S, et al. Convalescent Plasma Therapy in Patients With COVID-19. J Clin Apher (2020) 35:367–73. doi: 10.1002/jca.21806

10. Scoppetta C, Di Gennaro G, Polverino F. Editorial - High Dose Intravenous Immunoglobulins as a Therapeutic Option for COVID-19 Patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci (2020) 24(9):5178–9. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202005_21214

11. Saghazadeh A, Rezaei N. Towards Treatment Planning of COVID-19: Rationale and Hypothesis for the Use of Multiple Immunosuppressive Agents: Anti-Antibodies, Immunoglobulins, and Corticosteroids. Int Immunopharmacol (2020) 84:106560. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106560

12. Investigators R-C, Gordon AC, Mouncey PR, Al-Beidh F, Rowan KM, Nichol AD, et al. Interleukin-6 Receptor Antagonists in Critically Ill Patients With Covid-19. N Engl J Med (2021) 384:1491–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100433

13. Salama C, Han J, Yau L, Reiss WG, Kramer B, Neidhart JD, et al. Tocilizumab in Patients Hospitalized With Covid-19 Pneumonia. N Engl J Med (2021) 384(1):20–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2030340

14. Salvarani C, Dolci G, Massari M, Merlo DF, Cavuto S, Savoldi L, et al. Effect of Tocilizumab vs Standard Care on Clinical Worsening in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med (2021) 181(1):24–31. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0404

15. Vabret N, Britton GJ, Gruber C, Hegde S, Kim J, Kuksin M, et al. Immunology of COVID-19: Current State of the Science. Immunity (2020) 52(6):910–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.05.002

16. Mangalmurti N, Hunter CA. Cytokine Storms: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity (2020) 53(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.017

17. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, et al. COVID-19: Consider Cytokine Storm Syndromes and Immunosuppression. Lancet (2020) 395(10229):1033–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0

18. Meckiff BJ, Ramirez-Suastegui C, Fajardo V, Chee SJ, Kusnadi A, Simon H, et al. Imbalance of Regulatory and Cytotoxic SARS-CoV-2-Reactive CD4(+) T Cells in COVID-19. Cell (2020) 183(5):1340–53 e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.001

19. Anghelina D, Zhao J, Trandem K, Perlman S. Role of Regulatory T Cells in Coronavirus-Induced Acute Encephalitis. Virology (2009) 385(2):358–67. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.12.014

20. Jarjour NN, Masopust D, Jameson SC. T Cell Memory: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity (2021) 54(1):14–8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.12.009

21. Bacher P, Rosati E, Esser D, Martini GR, Saggau C, Schiminsky E, et al. Low-Avidity CD4(+) T Cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2 in Unexposed Individuals and Humans With Severe COVID-19. Immunity (2020) 53(6):1258–71 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.11.016

22. Ferretti AP, Kula T, Wang Y, Nguyen DMV, Weinheimer A, Dunlap GS, et al. Unbiased Screens Show CD8(+) T Cells of COVID-19 Patients Recognize Shared Epitopes in SARS-CoV-2 That Largely Reside Outside the Spike Protein. Immunity (2020) 53(5):1095–107 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.10.006

23. Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic Self-Tolerance Maintained by Activated T Cells Expressing IL-2 Receptor Alpha-Chains (CD25). Breakdown of a Single Mechanism of Self-Tolerance Causes Various Autoimmune Diseases. J Immunol (1995) 155(3):1151–64.

24. Fujimura T, Yonekura S, Taniguchi Y, Horiguchi S, Saito A, Yasueda H, et al. The Induced Regulatory T Cell Level, Defined as the Proportion of IL-10(+)Foxp3(+) Cells Among CD25(+)CD4(+) Leukocytes, is a Potential Therapeutic Biomarker for Sublingual Immunotherapy: A Preliminary Report. Int Arch Allergy Immunol (2010) 153(4):378–87. doi: 10.1159/000316349

25. da Cunha AP, Weiner HL. Induction of Immunological Tolerance by Oral Anti-CD3. Clin Dev Immunol (2012) 2012:425021. doi: 10.1155/2012/425021

26. Wu HY, Maron R, Tukpah AM, Weiner HL. Mucosal Anti-CD3 Monoclonal Antibody Attenuates Collagen-Induced Arthritis That is Associated With Induction of LAP+ Regulatory T Cells and is Enhanced by Administration of an Emulsome-Based Th2-Skewing Adjuvant. J Immunol (2010) 185(6):3401–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000836

27. Bresson D, Togher L, Rodrigo E, Chen Y, Bluestone JA, Herold KC, et al. Anti-CD3 and Nasal Proinsulin Combination Therapy Enhances Remission From Recent-Onset Autoimmune Diabetes by Inducing Tregs. J Clin Invest (2006) 116(5):1371–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI27191

28. Mayo L, Cunha AP, Madi A, Beynon V, Yang Z, Alvarez JI, et al. IL-10-Dependent Tr1 Cells Attenuate Astrocyte Activation and Ameliorate Chronic Central Nervous System Inflammation. Brain (2016) 139(Pt 7):1939–57. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww113

29. Wu HY, Center EM, Tsokos GC, Weiner HL. Suppression of Murine SLE by Oral Anti-CD3: Inducible CD4+CD25-LAP+ Regulatory T Cells Control the Expansion of IL-17+ Follicular Helper T Cells. Lupus (2009) 18(7):586–96. doi: 10.1177/0961203308100511

30. van der Woude CJ, Stokkers P, van Bodegraven AA, Van Assche G, Hebzda Z, Paradowski L, et al. Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Escalation Study of NI-0401 (a Fully Human Anti-CD3 Monoclonal Antibody) in Patients With Moderate to Severe Active Crohn's Disease. Inflammation Bowel Dis (2010) 16(10):1708–16. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21252

31. Izzy S, Tahir Z, Cote DJ, Al Jarrah A, Roberts MB, Turbett S, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Latinx Patients With COVID-19 in Comparison With Other Ethnic and Racial Groups. Open Forum Infect Dis (2020) 7(10):ofaa401. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa401

32. Herold T, Jurinovic V, Arnreich C, Lipworth BJ, Hellmuth JC, von Bergwelt-Baildon M, et al. Elevated Levels of IL-6 and CRP Predict the Need for Mechanical Ventilation in COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2020) 146(1):128–36 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.008

33. Ali N. Elevated Level of C-Reactive Protein may be an Early Marker to Predict Risk for Severity of COVID-19. J Med Virol (2020) 92(11):2409–11. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26097

34. Luo M, Liu J, Jiang W, Yue S, Liu H, Wei S. IL-6 and CD8+ T Cell Counts Combined are an Early Predictor of in-Hospital Mortality of Patients With COVID-19. JCI Insight (2020) 5(13):e139024. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.139024

35. Leaf DE, Gupta S, Wang W. Tocilizumab in Covid-19. N Engl J Med (2021) 384(1):86–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2032911

36. Tsai A, Diawara O, Nahass RG, Brunetti L. Impact of Tocilizumab Administration on Mortality in Severe COVID-19. Sci Rep (2020) 10(1):19131. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76187-y

37. Ogura M, Deng S, Preston-Hurlburt P, Ogura H, Shailubhai K, Kuhn C, et al. Oral Treatment With Foralumab, a Fully Human Anti-CD3 Monoclonal Antibody, Prevents Skin Xenograft Rejection in Humanized Mice. Clin Immunol (2017) 183:240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2017.07.005

38. Herold KC, Bundy BN, Long SA, Bluestone JA, DiMeglio LA, Dufort MJ, et al. An Anti-CD3 Antibody, Teplizumab, in Relatives at Risk for Type 1 Diabetes. N Engl J Med (2019) 381(7):603–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1902226

39. Kuhn C, Weiner HL. Therapeutic Anti-CD3 Monoclonal Antibodies: From Bench to Bedside. Immunotherapy (2016) 8(8):889–906. doi: 10.2217/imt-2016-0049

40. Wu HY, Quintana FJ, Weiner HL. Nasal Anti-CD3 Antibody Ameliorates Lupus by Inducing an IL-10-Secreting CD4+ CD25- LAP+ Regulatory T Cell and is Associated With Down-Regulation of IL-17+ CD4+ ICOS+ CXCR5+ Follicular Helper T Cells. J Immunol (2008) 181(9):6038–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6038

41. Group RC, Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients With Covid-19. N Engl J Med (2021) 384(8):693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

42. Shuto H, Komiya K, Yamasue M, Uchida S, Ogura T, Mukae H, et al. A Systematic Review of Corticosteroid Treatment for Noncritically Ill Patients With COVID-19. Sci Rep (2020) 10(1):20935. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78054-2

Keywords: foralumab, anti-CD3, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, immune responses

Citation: Moreira TG, Matos KTF, De Paula GS, Santana TMM, Da Mata RG, Pansera FC, Cortina AS, Spinola MG, Baecher-Allan CM, Keppeke GD, Jacob J, Palejwala V, Chen K, Izzy S, Healey BC, Rezende RM, Dedivitis RA, Shailubhai K and Weiner HL (2021) Nasal Administration of Anti-CD3 Monoclonal Antibody (Foralumab) Reduces Lung Inflammation and Blood Inflammatory Biomarkers in Mild to Moderate COVID-19 Patients: A Pilot Study. Front. Immunol. 12:709861. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.709861

Received: 17 May 2021; Accepted: 28 July 2021;

Published: 12 August 2021.

Edited by:

Dan Frenkel, Tel Aviv University, IsraelReviewed by:

Georg Varga, University Hospital Muenster, GermanySrijayaprakash Babu Uppada, University of Alabama, United States

Copyright © 2021 Moreira, Matos, De Paula, Santana, Da Mata, Pansera, Cortina, Spinola, Baecher-Allan, Keppeke, Jacob, Palejwala, Chen, Izzy, Healey, Rezende, Dedivitis, Shailubhai and Weiner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Howard L. Weiner, aHdlaW5lckByaWNzLmJ3aC5oYXJ2YXJkLmVkdQ==; Thais G. Moreira, dG1vcmVpcmFAYndoLmhhcnZhcmQuZWR1

Thais G. Moreira1*

Thais G. Moreira1* Gerson D. Keppeke

Gerson D. Keppeke Vaseem Palejwala

Vaseem Palejwala Saef Izzy

Saef Izzy Rafael M. Rezende

Rafael M. Rezende Howard L. Weiner

Howard L. Weiner