- 1The Key Laboratory of Biosystems Homeostasis & Protection of Ministry of Education, Life Sciences Institute, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

- 2Liangzhu Laboratory, Zhejiang University Medical Center, Hangzhou, China

- 3Inflammatory Disease Section, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States

RIPK1 (receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1) is a key molecule for mediating apoptosis, necroptosis, and inflammatory pathways downstream of death receptors (DRs) and pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). RIPK1 functions are regulated by multiple post-translational modifications (PTMs), including ubiquitination, phosphorylation, and the caspase-8-mediated cleavage. Dysregulation of these modifications leads to an immune deficiency or a hyperinflammatory disease in humans. Over the last decades, numerous studies on the RIPK1 function in model organisms have provided insights into the molecular mechanisms of RIPK1 role in the maintenance of immune homeostasis. However, the physiological role of RIPK1 in the regulation of cell survival and cell death signaling in humans remained elusive. Recently, RIPK1 loss-of-function (LoF) mutations and cleavage-deficient mutations have been identified in humans. This review discusses the molecular pathogenesis of RIPK1-deficiency and cleavage-resistant RIPK1 induced autoinflammatory (CRIA) disorders and summarizes the clinical manifestations of respective diseases to help with the identification of new patients.

Introduction

RIPK1 is a key modulator of inflammatory signaling and cell death pathways and its functions ultimately determine the cell fate upon different cellular stimulations. A growing body of evidence suggests that many human diseases, including systemic inflammation (1–5), cardiovascular disease (6), neurodegenerative disease (7), and cancer (8) are related to dysregulations in RIPK1-mediated cell death pathways. In recent years, multiple studies in model organisms have provided better understandings of the intricate biological functions of RIPK1. However, the role of RIPK1 in the regulation of immune responses has not been fully understood until very recently with the identification of RIPK1-deficiency Immunodeficiency 57 With Autoinflammation; OMIM: # 618108 (9–12) and the autoinflammatory disease named CRIA (Cleavage-resistant RIPK1-Induced Autoinflammatory) (13, 14). Both disorders are characterized by a profound dysregulation of cytokine expression and cell death pathways, and severe immune dysfunction.

RIPK1 as a Regulator of Cell Death Pathways

Apoptosis and necroptosis are two distinct forms of programmed cell death. Both are critical for the regulation of embryonic development, immune response, and many other biological processes (15, 16). Apoptosis is executed by caspase-mediated events, while necroptosis is mediated by RIPK3 (receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 3), MLKL (mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein) and upstream effectors such as RIPK1. The upstream regulator, RIPK1, is a key signaling node for determination of cell fate in response to TNF stimulation.

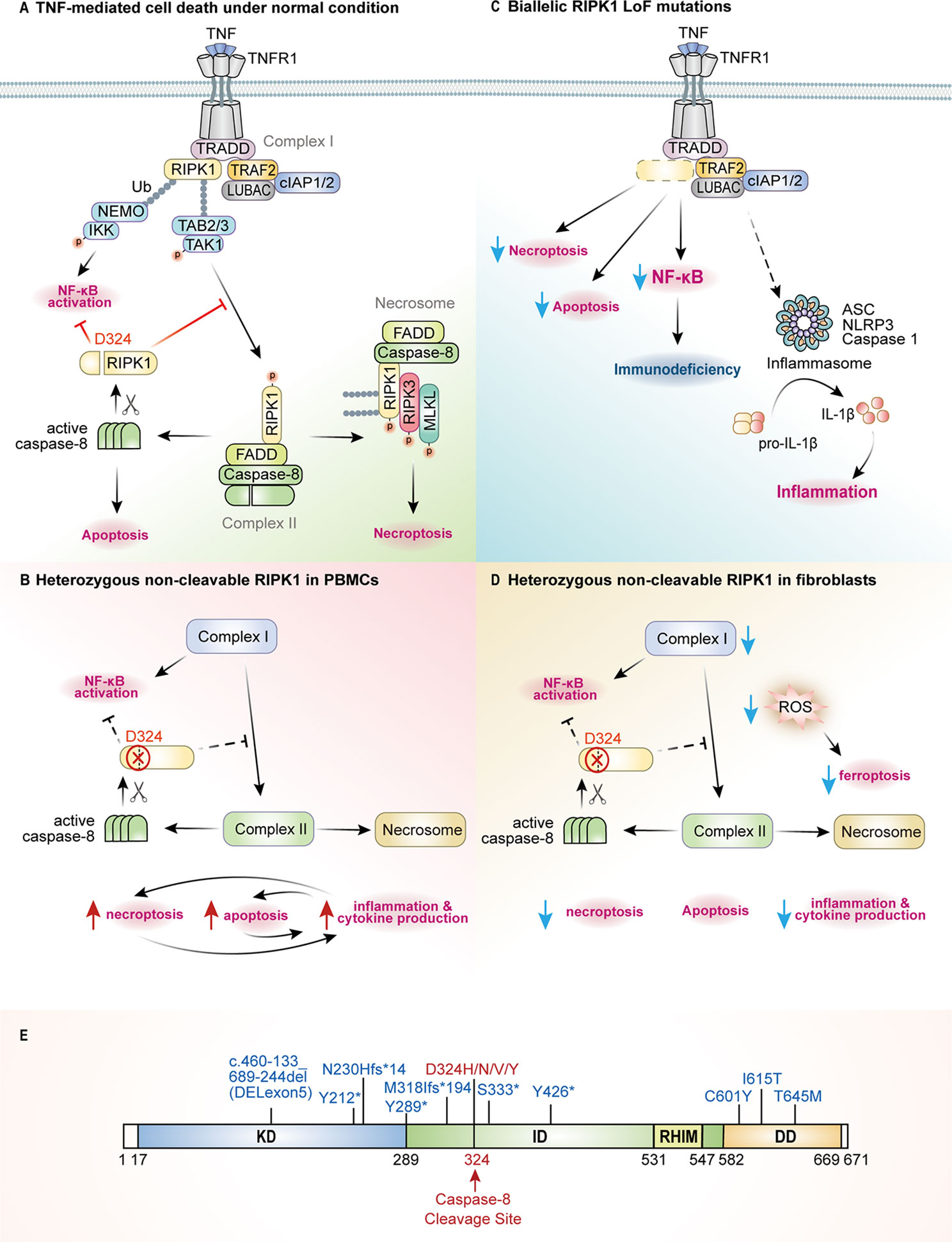

RIPK1 is a 75.9 kDa protein with an amino-terminal kinase domain (KD), a carboxy-terminal death domain (DD), and an intermediate domain (ID) in-between which contains a Rip homotypic interaction motif (RHIM). RIPK1 plays a crucial role in mediating downstream signals triggered by DRs and PRRs, and that function is highly dependent on its PTMs, including ubiquitination, phosphorylation or cleavage. For example, the ubiquitination status of RIPK1 can trigger a switch from NF-κB-mediated pro-survival inflammatory signaling to cell death pathways via activation of caspase-8-dependent apoptosis or RIPK3/MLKL-dependent necroptosis (17–19). Binding of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) to TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) on cell surface initiates receptor trimerization and recruitment of TRADD (TNFR1-associated death domain) and RIPK1 to form the signaling complex I. This complex then recruits a series of E3 ligases including TRAF2/5 (TNF receptor associated factor 2 and 5), cIAP1/2 (cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 and 2), and LUBAC (linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex) to ubiquitinate various components in the complex (20). This process provides a docking platform to recruit kinases including TAK1 (transforming growth factor β-activated kinase 1), IKKα/β/γ/ϵ (Inhibitor of κB kinase α/β/γ/ϵ) and TBK1 (TANK-binding kinase 1) to activate NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, which results in expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8, as well as promoting proliferation and cell survival (18–20) (Figure 1A). A set of kinases such as TAK1 (21), MK2 (22–24), IKKα/β (25), and TBK1 (26, 27) can phosphorylate RIPK1 at different sites to inhibit its kinase activity. The RIPK1 function is also negatively regulated by deubiquitinases (DUBs), including A20 (28) and CYLD (Cylindromatosis) (29, 30).

Figure 1 The pathogenic mechanisms of RIPK1-deficiency and CRIA patients. (A) RIPK1 is the key switch protein to mediate signal transduction downstream of TNFR1. TNF mediated TNFR1 trimerization results in recruitment of TRADD and RIPK1 through death-domain interactions to form complex I where post translational modifications (PTMs) by E3 ligases such as TRAFs, cIAPs and LUBAC or kinase complexes NEMO/IKK, TAK1/TAB2/3 determine the cell fate either to activate NF-κB signaling or to execute programmed cell death pathways. RIPK1 activates itself through trans-autophosphorylation and then interacts with FADD/caspase-8 to form the complex II to undergo RIPK1-dependent apoptosis (RDA), or it binds RIPK3/MLKL to form the necrosome and to initiate necroptosis. Active caspase-8 can cleave RIPK1 at Asp324 to inhibit complex II formation, and the RIPK1 inactivation will shift the balance towards necroptotic signaling. (B) In PBMCs of CRIA patients, due to the pathogenic mutations at Asp324, RIPK1 activation and all downstream signaling pathways are amplified to promote inflammation and cytokine production. (C) In case of the RIPK1 deficiency caused by biallelic LoF mutations, complex I-mediated signaling and downstream events will be blocked, leading to decreased NF-κB activation and impaired cell death. However, deficiency of RIPK1 may promote noncanonical TLR4-TRIF-RIPK1-FADD-Caspase-8 signaling to activate inflammasome formation and necroptosis. (D) Non-cleavable RIPK1 in CRIA patients fibroblasts causes reduced inflammatory signaling and necroptosis, but almost unchanged levels of apoptosis under TNFR1 signaling pathway. Besides, the decreased production of ROS in fibroblasts through yet unknown mechanisms leads to reduced ferroptosis. (E) The position of RIPK1 (NM0038.4.6) LoF mutations (blue, homozygous) and cleavage-deficient mutations (red, heterozygous) are indicated across the protein domains.

Under pathological conditions when NF-κB is inhibited or RIPK1 is no longer ubiquitinated or phosphorylated (18–20), RIPK1 interacts with FADD (FAS-associated death domain) and caspase-8 to form complex II, which then triggers downstream RIPK1-dependent apoptosis (RDA). In case where caspase-8 activation is blocked, RIPK1 auto-phosphorylates at Ser166 (31) and co-aggregates with RIPK3, through the RHIM-RHIM interaction, and MLKL to form the complex termed necrosome (32–35). Subsequently, MLKL gets phosphorylated by RIPK3 and causes necroptosis by disrupting the plasma membrane (36, 37). In complex II, caspase-8 serves as a regulatory switch of RIPK1 activity through cleavage at RIPK1 residue Asp324 (Figure 1A). Pathogenic genetic variants that block the cleavage of RIPK1 by caspase-8 lead to RIPK1 over-activation, and the promotion of RDA and necroptosis (13, 14, 38, 39) (Figure 1B). RIPK1 deficiency due to pathogenic LoF variants leads to reduced NF-κB activation and dysregulated cell death under specific conditions, e.g., TNF or poly(I:C) stimulation, or a combination of TNF plus BV6 (IAP inhibitor) induced apoptosis and TNF, BV6 plus zVAD-fmk (pan-caspase inhibitor) induced necroptosis in patients’ fibroblasts, as well as in RIPK1-/- HT-29 cell lines (9, 10) (Figure 1C).

The complicated mechanisms of RIPK1 in mediating inflammation and cell death have been described in numerous studies using mouse models. Constitutive Ripk1-/- mice die postnatally due to dysregulated cell death and systemic inflammation (40), which can be rescued by knockout of Ripk3 and either Fadd or Casp8 (1, 3–5). Because of the indispensable role of RIPK1 in embryonic development, conditional knockout mice were constructed to study cell-specific functions of this protein. Ripk1 deletion in mouse intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) causes IEC apoptosis and loss of goblet and Paneth cells, manifesting with severe intestinal pathology and premature death (41, 42). Similarly, Ripk1 deletion in epidermis cell induces keratinocyte apoptosis and necroptosis, resulting in severe skin inflammation (42). In contrast to the phenotype of constitutive and conditional Ripk1–/– mice, mice engineered with RIPK1 knock-in (KI) kinase-dead mutations, including Asp138Asn (43), Lys45Ala (5, 44), Gly27_Phe28del (45) and the Lys584Arg (46) mutation affecting the dimerization of death domain, are viable and normal, which indicates the dispensable role of RIPK1 kinase activity in regulating development.

Caspase-8 cleavage activity is essential for inhibition of the RIPK1-dependent cell death during embryogenesis. Casp8 knockout in mice leads to embryonic lethality due to defects in the vascular, cardiac, and hematopoietic systems (47). This phenotype is linked to increased necroptosis and can be rescued by the deletion of either Ripk3 or Mlkl (48–50). Similarly, mice with enzymatically inactive caspase-8 (Cys362Ser or Cys362Ala) also died at embryonic stage owing to increased endothelial cell necroptosis that can be prevented by knockout of Mlkl. However, lethality of Casp8C362S/C362SMlkl–/– mice was noted at perinatal stage (38, 51). Furthermore, conditional expression of inactive caspase-8 in IECs caused ASC [apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-activation and recruitment domain (CARD)] assembly, while loss of either caspase-1 or ASC helped the normal development of Casp8C362S/C362SMlkl–/– mice (38, 51). Therefore, caspase-8 and its enzymatical activity play a critical role in the regulation of apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis, a type of inflammasome-mediated cell death.

There is also a strong evidence that RIPK1 is an essential substrate of caspase-8 as mutant Ripk1D325A/D325A mice, in which the caspase-8 cleavage site Asp325 was abolished, died between E10.5 and E11.5. The embryonic lethality of Ripk1D325A/D325A mice can be prevented by inhibition of RIPK1 kinase activity, deletion of Tnfr1, or a combined deletion of Fadd and Ripk3, or deletion of Fadd and Mlkl (14, 38, 39). Although Ripk1D325A/+ and kinase-dead Ripk1D138N,D325A/D138N,D325A mice survived, they developed multi-organ inflammation, and their cells were hypersensitive to TNF-induced cell death (14, 38). Therefore, cleavage of RIPK1 by caspase-8 is a mechanism for preventing abnormal cell death.

These functional and mechanistic studies of RIPK1 in mouse have provided compelling evidences for the indispensable role of RIPK1 in development and inflammation. Besides, they have established platforms for the investigation of RIPK1-associated diseases in humans.

RIPK1-Related Human Immune Diseases

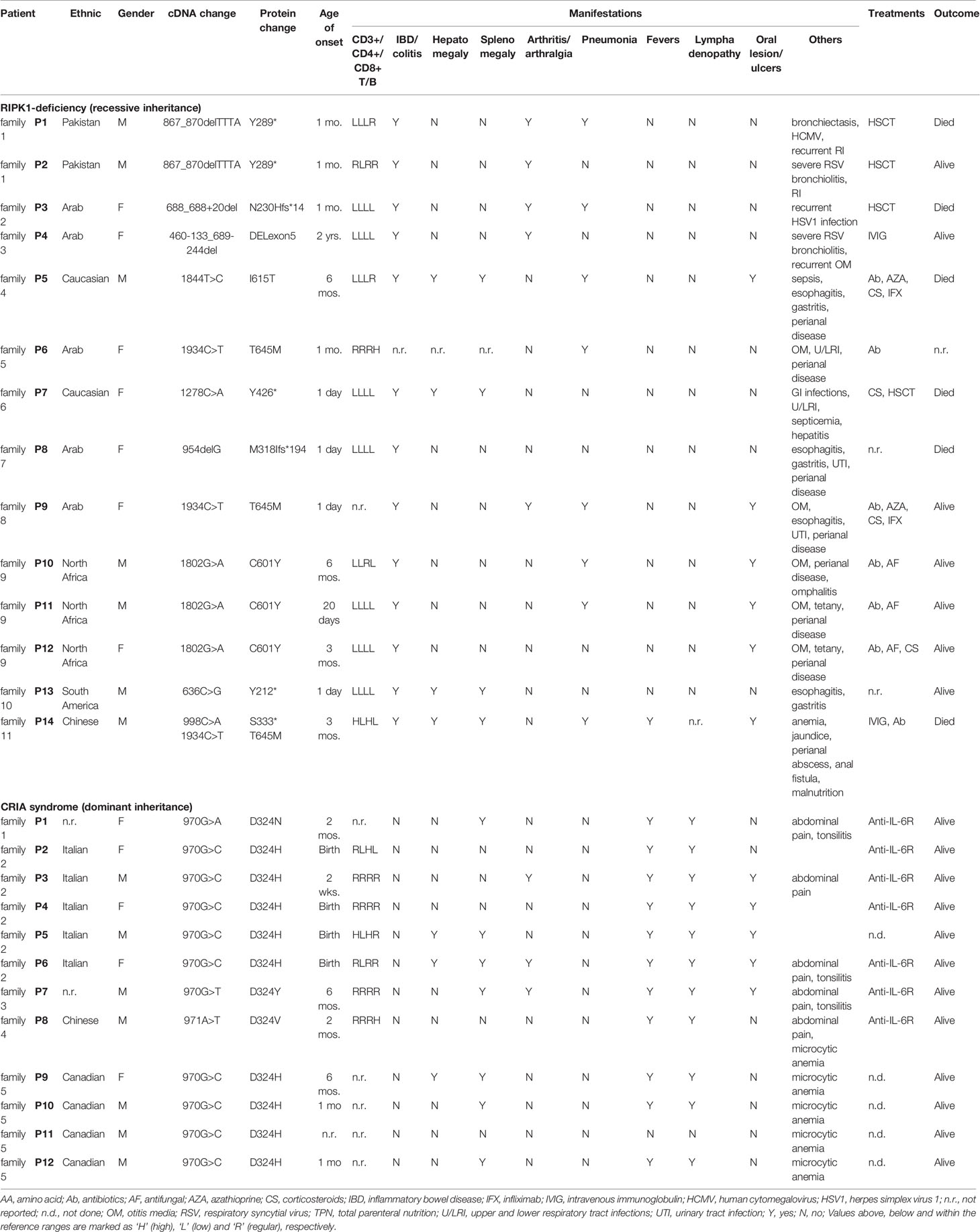

Dysregulation in the innate immune system can result in immunodeficiency or autoinflammatory disease. Immunodeficiency is a state in which the immune system’s ability to defend against various pathogens is diminished or severely compromised. Systemic autoinflammatory diseases result from the over-activation of innate immune cells, such as circulating and tissue-resident myeloid cells. Given that these are life-long immunological disorders, dysregulation in the adaptive immune system can ensue. From 2018 till now, six independent groups have reported patients with RIPK1-associated immunodeficiency or autoinflammatory diseases (9–14). Patients with RIPK1 deficiency and RIPK1 non-cleavable mutations present with distinct clinical manifestations. The summary of the genotypes and clinical phenotypes of 14 RIPK1-deficiency and 12 CRIA patients are listed in Table 1, and the position of pathogenic variants in RIPK1 are indicated in Figure 1E.

Table 1 Genotypes, clinical phenotypes, immunological manifestations and treatments of RIPK1-deficiency and CRIA patients.

Immunodeficiency and Inflammation Caused by RIPK1 Deficiency

Unlike postnatal lethality of Ripk1 constitutive knockout mice, patients with RIPK1 biallelic LoF mutations were born alive, however, they suffered from severe and potentially lethal immunodeficiency (9–12), and one of them had autoinflammatory manifestations (12). The associated phenotypes include recurrent viral, bacterial, and/or fungal infections, early-onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and progressive polyarthritis. The immunodeficiency results from impaired differentiation of T and B cells, profound lymphopenia, and decreased production of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6, TNF and IL-12. The inflammatory component of this disease is possibly related to the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and high production of IL-1β cytokine (Figure 1C). This observation requires further investigations.

Autoinflammation Caused by Non-Cleavable RIPK1 Variants

Patients with heterozygous missense mutations at the RIPK1 residue Asp324 present with recurrent fevers and lymphadenopathy (13, 14). The caspase-8 cleavage site Asp324 is highly conserved across species, indicating its importance from the evolutionary prospect. The disease-associated variants Asp324Val, Asp324His, Asp324Asn, and Asp324Tyr were identified in different families either as a de novo mutation or as a dominantly inherited allele. These pathogenic variants render RIPK1 non-cleavable, as they block caspase-8 mediated cleavage, thereby promoting RIPK1 activation.

Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Attempts

Impaired Inflammation Pathways and Disordered Cytokine Production

Interestingly, both RIPK1-deficiency and CRIA patients present with a substantial dysregulation in inflammatory pathways and cytokine production. These cellular phenotypes were replicated in RIPK1-deficient cell lines (9, 10) and RIPK1 Asp325 mutation knock-in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (13, 14).

Biallelic LoF mutations in RIPK1 result in reduced NF-κB and MAPK signaling. Fibroblasts from a RIPK1-deficiency patient (c.688_688+20del, p.Asn230Hisfs*14) had markedly reduced phosphorylation of p38 and AP-1 subunit c-Jun, as well as partially reduced phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 under TNF or poly(I:C) stimulation, which showed impaired proinflammatory signaling downstream of TNFR1 or TLR3 (10). Similarly, RIPK1-deficient cell lines (HCT-116, Jurkat) showed reduced NF-κB activation in response to TNF (9). Consequently, TNF-induced secretion of IL-6 and RANTES in patients’ fibroblasts, LPS-induced production of IL-6, TNF, and IL-12 in patient’s primary monocytes, and LPS-induced IL-6 and IL-10 in RIPK1-/- THP1 cells were all significantly diminished (9).

RIPK1-deficient patients have dysregulated T cell responses under PHA stimulation with reduced production of IL-17 and IFN-γ, while the levels of TNF, IL-6, and IL-10 were normal. In contrast, IL-1β production was markedly increased in PHA-stimulated patient’s blood and LPS-stimulated RIPK1-/- monocytic cell lines (9, 10). These observations were in agreement with previous studies reporting an altered inflammasome activity in conditional Ripk1 knockout mice (52). The altered IL-1β release has been associated with increased NLPR3 activity and MLKL-dependent necroptosis, based on evidence that inhibitors of NLRP3 or MLKL can reduce IL-1β secretion in LPS-stimulated RIPK1-deficient cell lines (BLaER1 and THP1 cells) (9, 10).

In contrast, CRIA patients’ PBMCs and monocytes have a strong inflammatory signature in NF-κB and type I IFN pathways, and elevated production of IL-6, TNF, and IL-1β cytokines (13). Similarly, mouse models and cell lines engineered with the CRIA-associated mutations display enhanced inflammatory response induced by TNF (13, 14). However, there exist cell-specific effect of non-cleavable RIPK1, as loss of RIPK1 cleavage in patient-derived fibroblasts did not affect TNF-induced NF-κB activation, and Ripk1 knock out MEFs complemented with non-cleavable Ripk1 variants had no difference in NF-κB signaling activation upon TRAIL stimulation (13, 14).

Another difference between the CRIA and RIPK1-deficient patients is the inducer of fluctuated cytokines. The reduced secretion of IL-6 in RIPK1-/- THP1 cells is independent of necroptosis since it can’t be restored by adding necroptosis inhibitor (10). Whereas, the cytokine increases observed in the CRIA patients’ PBMCs or in Ripk1-/- MEFs complemented with RIPK1 Asp325 mutants were dependent on RIPK3 and caspase-8 (13, 14), suggesting that cell death is the major contributor to cytokine induction in the context of non-cleavable RIPK1.

Dysregulation of Cell Death

RIPK1 regulates both apoptosis and necroptosis by forming different complexes. However, controversy exists on the specific mechanism based on different observations in various cell lines.

Cuchet-Lourenço et al. found that RIPK1-deficient patient-derived fibroblasts were more sensitive to TNF or poly(I:C) induced cell death, which was reversed by complementation with wild-type RIPK1 (10). Further experiments revealed increased phosphorylation of RIPK3 and MLKL with no cleavage of caspase-8 in patients’ fibroblasts in response to poly(I:C) stimulation. In addition, the MLKL inhibitor NSA and RIPK3 inhibitor GSK’872 can rescue patients’ cells from poly(I:C)-induced cell death, whereas the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk and RIPK1 inhibitor Nec-1s had no effect. Together, these findings indicate that necroptosis was a major cell death mechanism in RIPK1-deficiency disease. A similar cell death phenotype was observed in RIPK1−/− THP1 cells.

In parallel investigations, Yue Li et al. used RIPK1-/- HT-29 cells to investigate the effect of RIPK1 deficiency on TNF-induced cell death (9). In contrast to patient-derived fibroblasts and myeloid cell lines that were prone to necroptosis induced by poly(I:C), RIPK1-/- HT-29 cells showed resistance to TNF and BV6 induced apoptosis and to TNF, BV6 plus zVAD-fmk induced necroptosis (Figure 1C).

In CRIA patients, the non-cleavable RIPK1 initiates RDA and necroptosis in myeloid cells but not in patient-derived fibroblasts (13, 14). Panfeng Tao et al. reported that patients’ PBMCs displayed increased sensitivity to apoptosis (induced by co-treatment with TNF and apoptosis-inducing SMAC mimetic SM-164, T/S) and necroptosis (induced by co-treatment with SM-164 and zVAD-fmk, S/Z). This phenotype was suppressed by RIPK1 inhibitor Nec-1s, indicating that RIPK1 kinase activity may promote downstream cell death pathways. Evidence of necrotic cell death in vivo was demonstrated by detecting cyclophilin A in a patient’s urine samples during the disease flare. Similarly, TNF-induced cell death was elevated in Ripk1-/- MEFs expressing mutant RIPK1 and was inhibited by Nec-1s or the RIPK1 kinase inactivating mutation Asp138Asn. The activated RIPK1 can drive RDA independent of necroptosis as Ripk1D325A/D325ARipk3−/− MEFs remained sensitized to T/S induced apoptosis (13, 14).

The work by Lalaoui et al. provides a comprehensive in vitro and in vivo description of the molecular mechanisms of inflammation in CRIA (14). Besides the findings that MEFs with RIPK1 non-cleavable mutants are sensitized to TNF-induced apoptosis and necroptosis, this study reports that caspase-8 mediated RIPK1 cleavage during embryogenesis can inhibit necroptosis and maintain normal development. As to the role of RIPK3, this study shows that the inhibition of RIPK3 kinase activity had little effect on the induction of cell death, while genetic loss of Ripk3 in Ripk1D325A/D325A MEFs had significantly reduced auto-phosphorylation of RIPK1 and caspase activation under T/S treatment. These data suggest that RIPK3 contributes mainly in a structural capacity to the activation of caspase-8.

Taken together, studies on the mechanisms of CRIA syndrome revealed that non-cleavable variants in RIPK1 promote cell death as well as the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Clinical Treatments

Better understanding of upstream and downstream events in the RIPK1 activation and signal transduction process will help to implement targeted treatment for patients with RIPK1 pathogenic mutations. For patients with CRIA, the small molecule RIPK1 inhibitor might be a treatment choice (53, 54). Although cytokine inhibition is effective in many autoinflammatory diseases, such as anti-IL-1β therapies for most inflammasomopathies (55, 56), TNF inhibitors for NF-κB-activation disorders (57, 58), and JAK inhibitors for interferonopathies (59), concerns remain on the long-term use and efficacy of biological therapies. CRIA patients appear to be responsive to therapy with an IL-6R antagonist (13, 14). In patients with RIPK1 deficiency, treatment with IL-1 inhibitors may ameliorate the inflammatory manifestations. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains another possibility as it can be curative in patients with severe immunodeficiencies, if performed early-in life (60–62). HSCT has resolved the inflammatory manifestations and reduced the frequency of infections in one RIPK1-deficient patient (10). Gene therapies, whether to replace deficient RIPK1 gene or gene-editing therapy in CRIA patients, might be a long-term consideration.

The summary of treatments used thus far in RIPK1-deficiency and CRIA patients is shown in Table 1. The response and outcomes to different therapies have been highly variable among patients, and the long-term consequences remain to be described.

The Role of RIPK1 in Other Autoinflammatory and Autoimmune Disorders

Pathogenic mutations in genes encoding multiple regulators of the NF-κB pathway and the RIPK1 activation, including TNFR1, NEMO, A20, LUBAC and OTULIN, have been found in patients with autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases (63). The identification of these disorders has contributed to a better understanding of mechanisms that underlie the regulation of the canonical NF-kB pathway in humans.

TNFR1 is the major signaling receptor of TNF that can initiate a number of downstream pathways including NF-κB, MAPK signaling and programmed cell death. These processes are tightly connected with RIPK1 scaffolding function and partially dependent on RIPK1 kinase activity. Pathogenic missense mutations in the extracellular domain of TNFR1 (encoded by TNFRSF1A) causes TNF Receptor-associated Periodic Syndrome (TRAPS), an autosomal dominant autoinflammatory disease (64). The clinical manifestations of TRAPS include periodic long-lasting fever, serositis, abdominal pain, arthralgia, migratory skin rash, and myalgia (65). The molecular pathogenesis of TRAPS is still elusive, and the contribution of cell death pathways have not been investigated. The mutant TNFR1 proteins accumulate in the cells, which can trigger endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and unfolded protein response (UPR) (66), as well as excessive mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mROS) (67). All these processes are known to promote inflammatory cytokine production and can explain a strong inflammatory signature in this disorder.

Mutations in NEMO, an essential modulator of NF-κB encoded by IKBKG, are associated with incontinentia pigmenti and X-linked ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency (68). NEMO serves as an adaptor protein to recruit IKKα/β for NF-κB activation and TBK1/IKKϵ for type-I IFN signaling, all of them are negative regulators of RIPK1 kinase activation and its kinase dependent cell death as well (27). Individuals with hypomorphic or LoF mutations in IKBKG gene develop severe immunodeficiency, ectodermal dysplasia manifesting with coning teeth, hypodontia and inability to sweat, and colitis (69). Ectodermal dysplasia can be explained by the inability of the ectodysplasin A receptor (a TNF receptor family member) to induce NF-kB activation (69).

A20, encoded by TNFAIP3, is an enzyme that regulates NF-κB activation by cleaving K63-linked polyubiquitin chains on RIPK1 and other components in the complex I. It can also build K48-linked polyubiquitin chains on RIPK1 (28). A20 contains an N-terminal ovarian tumor (OUT) domain which deubiquitylate K63-polyubiquitin chains, and seven C-terminal zinc finger (ZnF) domains that bind to ubiquitin and act as an E3-ligase, of which ZnF7 can bind and modulate linear ubiquitin chains (70). Heterozygous LoF mutations in TNFAIP3 gene are associated with Haploinsufficiency of A20 (HA20), a childhood-onset systemic autoinflammatory disease manifesting with recurrent fever, arthritis, oral and/or genital ulcers, skin allergies, gastrointestinal inflammation, eye inflammation and autoimmunity (71, 72). HA20 patients’ PBMCs and fibroblasts have accumulated K63-linked polyubiquitin chains, as well as activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways with increased production of many pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF, IL-1β and IL-6.

The LUBAC complex is involved in the activation of NF-κB pathway in response to TNFR1 signaling by generating linear ubiquitin chains on NEMO, RIPK1, and other proteins. Biallelic LoF mutations in two of the LUBAC component: HOIL-1 (heme-oxidized IRP2 ubiquitin ligase 1; RBCK1) or HOIP (HOIL-1 interacting protein; RNF31), cause LUBAC deficiency, an autosomal recessive disease characterized by severe immunodeficiency, recurrent fever, and polyglucosan myopathy (73, 74).

OTULIN-related autoinflammatory syndrome (ORAS), also known as otulipenia, is an autoinflammatory disease caused by biallelic LoF mutations in the linear deubiquitinase OTULIN (75, 76). Patients present with early-onset recurrent fever, skin rash, neutrophilic nodular panniculitis/lipodystrophy, and gastrointestinal inflammation (76). The pathogenic variants reside in the OTU domain, which has a deubiquitination enzymic activity, and affect the binding of OTULIN to the linear ubiquitin chains. The excessive accumulation of poly-linear ubiquitin chains in patients’ PBMCs and fibroblasts causes constitutive activation of canonical NF-κB signaling pathway, and excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (75, 76).

Broadened Roles of RIPK1 in Regulating Multiple Pathways

Remarkable insights on the RIPK1 function in human immune diseases have been revealed during the past few years and are summarized in the following section.

First, RIPK1-deficient monocytes exhibit increased sensitivity to necroptosis and IL-1β release upon LPS stimulation. Previously, Gaidt, et al. have identified an alternative inflammasome signaling pathway via TLR4-TRIF-RIPK1-FADD-Caspase-8 in human monocytes (77). The LPS-dependent inflammasome signaling was only observed in the RIPK1-deficient monocytes transdifferentiated from immortalized human B cells but not in mouse models. Cuchet-Lourenço et al. identified elevated IL-1β production by T cells in vivo in the context of RIPK1 deficiency (10). In addition, previous studies have shown that RIPK1 and RIPK3 appears to promote the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome independent of cell death, and this effect can be suppressed by caspase-8 (78).

Second, CRIA patient’s fibroblasts display resistance to both necroptosis and another kind of programmed cell death, ferroptosis (13), which is an iron-dependent process accompanied by excessive lipid peroxidation (79). This phenomenon is opposite to that observed in patient’s PBMCs and might explain why there is no skin involvement of CRIA patients. This finding not only provides new evidence for heterogeneity of cell functions with respect to the cell type, but also makes a direct link between non-cleavable RIPK1 variants to ferroptosis. RIPK1 kinase activation can also be promoted by reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, the mediator of ferroptosis (80). However, ferroptosis is biochemically distinct from other programmed cell death pathways and can be triggered by a unique set of inducers (81). The role of RIPK1 in the regulation of ferroptosis needs to be investigated further.

Future Research

Despite enormous progress in understanding the role of RIPK1 in mediating cell death and inflammation, many questions remain concerning the molecular pathogenesis of RIPK1-associated diseases. They are following: 1) the unexpected difference in responses of CRIA patient’s fibroblasts and PBMCs to the same cell death inducers; 2) the causal relationship between RIPK1 non-cleavable variants and the expression of ferroptosis- or antioxidant-related genes; 3) the influence of RIPK1 deficiency on cell death in vivo; 4) the relationship between elevated expression of cytokines and increased cell death in CRIA patients. These questions might, in part, be answered with the identification of new pathogenic mutations in human patients that result either in hyperactivation or deficiency of RIPK1. Ultimately, answering these questions will help develop more efficient and targeted treatments for patients with RIPK1-associated diseases.

Of particular interest is the functional cell-type heterogeneity in PBMCs and fibroblasts of CRIA patients. Transcriptional analysis revealed decreased expression of RIPK1 and TNFR1, high levels of the antioxidant glutathione (GSH), and low levels of ROS in patients’ fibroblasts (13) (Figure 1D). These observations may in part explain the different cellular phenotypes between patient fibroblasts and PBMCs. Fibroblast is a type of resident permanent cells, and not like short-life bone-marrow-derived inflammatory cells such as granulocytes and macrophages, that can be eliminated quickly to downregulate inflammation (82). Previous studies have found that fibroblasts play a critical role in the switch of acute resolving inflammation to chronic persistent one by modifying the quantity and duration of the inflammatory infiltrate (83).

Discussion

RIPK1, as a critical regulator of NF-κB signaling, has the ability to transmit and interpret extracellular stimuli such as TNF to activate different downstream signaling pathways including NF-κB activation, apoptosis and necroptosis, with distinct outcomes.

The recent discovery of RIPK1-deficiency (9–12) and CRIA (13, 14) have enhanced the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of RIPK1 function in humans. Although the pathological mechanisms of these diseases have been revealed partly, there still exist many unsolved questions. A better understanding of the inflammatory mechanisms of rare RIPK1-associated monogenic diseases may help to develop more targeted therapies that could be used for a series of diseases, including rare neurodegenerative, autoimmune (psoriasis, ulcerative colitis and arthritis), acute ischemic diseases and other conditions such as sepsis and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (54, 84).

Author Contributions

JZ and TJ contributed equally. JZ wrote the original draft and draw the figure. TJ provided valuable comments and modified the manuscript. IA and QZ reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Rickard JA, O’donnell JA, Evans JM, Lalaoui N, Poh AR, Rogers T, et al. RIPK1 Regulates RIPK3-MLKL-Driven Systemic Inflammation and Emergency Hematopoiesis. Cell (2014) 157:1175–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.019

2. Zelic M, Roderick JE, O’donnell JA, Lehman J, Lim SE, Janardhan HP, et al. RIP Kinase 1-Dependent Endothelial Necroptosis Underlies Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome. J Clin Invest (2018) 128:2064–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI96147

3. Dowling JP, Nair A, Zhang J. A Novel Function of RIP1 in Postnatal Development and Immune Homeostasis by Protecting Against RIP3-Dependent Necroptosis and FADD-Mediated Apoptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol (2015) 3:12. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2015.00012

4. Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Rodriguez DA, Cripps JG, Quarato G, Gurung P, et al. RIPK1 Blocks Early Postnatal Lethality Mediated by Caspase-8 and RIPK3. Cell (2014) 157:1189–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.018

5. Kaiser WJ, Daley-Bauer LP, Thapa RJ, Mandal P, Berger SB, Huang C, et al. RIP1 Suppresses Innate Immune Necrotic as Well as Apoptotic Cell Death During Mammalian Parturition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2014) 111:7753–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401857111

6. Zhe-Wei S, Li-Sha G, Yue-Chun L. The Role of Necroptosis in Cardiovascular Disease. Front Pharmacol (2018) 9:721. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00721

7. Yuan J, Amin P, Ofengeim D. Necroptosis and RIPK1-Mediated Neuroinflammation in CNS Diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci (2019) 20:19–33. doi: 10.1038/s41583-018-0093-1

8. Schneider AT, Gautheron J, Feoktistova M, Roderburg C, Loosen SH, Roy S, et al. Ripk1 Suppresses a TRAF2-Dependent Pathway to Liver Cancer. Cancer Cell (2017) 31:94–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.11.009

9. Li Y, Fuhrer M, Bahrami E, Socha P, Klaudel-Dreszler M, Bouzidi A, et al. Human RIPK1 Deficiency Causes Combined Immunodeficiency and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2019) 116:970–75. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1813582116

10. Cuchet-Lourenco D, Eletto D, Wu C, Plagnol V, Papapietro O, Curtis J, et al. Biallelic RIPK1 Mutations in Humans Cause Severe Immunodeficiency, Arthritis, and Intestinal Inflammation. Science (2018) 361:810–13. doi: 10.1126/science.aar2641

11. Uchiyama Y, Kim CA, Pastorino AC, Ceroni J, Lima PP, De Barros Dorna M, et al. Primary Immunodeficiency With Chronic Enteropathy and Developmental Delay in a Boy Arising From a Novel Homozygous RIPK1 Variant. J Hum Genet (2019) 64:955–60. doi: 10.1038/s10038-019-0631-3

12. Lin L, Wang Y, Liu L, Ying W, Wang W, Sun B, et al. Clinical Phenotype of a Chinese Patient With RIPK1 Deficiency Due to Novel Mutation. Genes Dis (2020) 7:122–27. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2019.10.008

13. Tao P, Sun J, Wu Z, Wang S, Wang J, Li W, et al. A Dominant Autoinflammatory Disease Caused by Non-Cleavable Variants of RIPK1. Nature (2020) 577:109–14. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1830-y

14. Lalaoui N, Boyden SE, Oda H, Wood GM, Stone DL, Chau D, et al. Mutations That Prevent Caspase Cleavage of RIPK1 Cause Autoinflammatory Disease. Nature (2020) 577:103–08. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1828-5

15. Haanen C, Vermes I. Apoptosis: Programmed Cell Death in Fetal Development. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol (1996) 64:129–33. doi: 10.1016/0301-2115(95)02261-9

16. Weinlich R, Oberst A, Beere HM, Green DR. Necroptosis in Development, Inflammation and Disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2017) 18:127–36. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.149

17. Liu L, Lalaoui N. 25 Years of Research Put RIPK1 in the Clinic. Semin Cell Dev Biol (2021) 109:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.08.007

18. Newton K. Multitasking Kinase Ripk1 Regulates Cell Death and Inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2020) 12(3):a036368. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a036368

19. Delanghe T, Dondelinger Y, Bertrand MJM. Ripk1 Kinase-Dependent Death: A Symphony of Phosphorylation Events. Trends Cell Biol (2020) 30:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.12.009

20. Peltzer N, Darding M, Walczak H. Holding RIPK1 on the Ubiquitin Leash in TNFR1 Signaling. Trends Cell Biol (2016) 26:445–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.01.006

21. Geng J, Ito Y, Shi L, Amin P, Chu J, Ouchida AT, et al. Regulation of RIPK1 Activation by TAK1-Mediated Phosphorylation Dictates Apoptosis and Necroptosis. Nat Commun (2017) 8:359. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00406-w

22. Jaco I, Annibaldi A, Lalaoui N, Wilson R, Tenev T, Laurien L, et al. Mk2 Phosphorylates RIPK1 to Prevent TNF-Induced Cell Death. Mol Cell (2017) 66:698–710 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.003

23. Dondelinger Y, Delanghe T, Rojas-Rivera D, Priem D, Delvaeye T, Bruggeman I, et al. MK2 Phosphorylation of RIPK1 Regulates TNF-Mediated Cell Death. Nat Cell Biol (2017) 19:1237–47. doi: 10.1038/ncb3608

24. Menon MB, Gropengiesser J, Fischer J, Novikova L, Deuretzbacher A, Lafera J, et al. p38(MAPK)/MK2-Dependent Phosphorylation Controls Cytotoxic RIPK1 Signalling in Inflammation and Infection. Nat Cell Biol (2017) 19:1248–59. doi: 10.1038/ncb3614

25. Dondelinger Y, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Divert T, Theatre E, Bertin J, Gough PJ, et al. NF-Kappab-Independent Role of IKKalpha/IKKbeta in Preventing Ripk1 Kinase-Dependent Apoptotic and Necroptotic Cell Death During TNF Signaling. Mol Cell (2015) 60:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.07.032

26. Lafont E, Draber P, Rieser E, Reichert M, Kupka S, De Miguel D, et al. TBK1 and IKKepsilon Prevent TNF-Induced Cell Death by RIPK1 Phosphorylation. Nat Cell Biol (2018) 20:1389–99. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0229-6

27. Xu D, Jin T, Zhu H, Chen H, Ofengeim D, Zou C, et al. Tbk1 Suppresses Ripk1-Driven Apoptosis and Inflammation During Development and in Aging. Cell (2018) 174:1477–91.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.041

28. Wertz IE, O’rourke KM, Zhou H, Eby M, Aravind L, Seshagiri S, et al. De-Ubiquitination and Ubiquitin Ligase Domains of A20 Downregulate NF-kappaB Signalling. Nature (2004) 430:694–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02794

29. Brummelkamp TR, Nijman SM, Dirac AM, Bernards R. Loss of the Cylindromatosis Tumour Suppressor Inhibits Apoptosis by Activating NF-Kappab. Nature (2003) 424:797–801. doi: 10.1038/nature01811

30. Trompouki E, Hatzivassiliou E, Tsichritzis T, Farmer H, Ashworth A, Mosialos G. CYLD Is a Deubiquitinating Enzyme That Negatively Regulates NF-kappaB Activation by TNFR Family Members. Nature (2003) 424:793–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01803

31. Newton K, Wickliffe KE, Maltzman A, Dugger DL, Strasser A, Pham VC, et al. RIPK1 Inhibits ZBP1-Driven Necroptosis During Development. Nature (2016) 540:129–33. doi: 10.1038/nature20559

32. Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray TD, Guildford M, et al. Phosphorylation-Driven Assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 Complex Regulates Programmed Necrosis and Virus-Induced Inflammation. Cell (2009) 137:1112–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037

33. He S, Wang L, Miao L, Wang T, Du F, Zhao L, et al. Receptor Interacting Protein Kinase-3 Determines Cellular Necrotic Response to TNF-Alpha. Cell (2009) 137:1100–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021

34. Li J, Mcquade T, Siemer AB, Napetschnig J, Moriwaki K, Hsiao YS, et al. The RIP1/RIP3 Necrosome Forms a Functional Amyloid Signaling Complex Required for Programmed Necrosis. Cell (2012) 150:339–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.019

35. Mompean M, Li W, Li J, Laage S, Siemer AB, Bozkurt G, et al. The Structure of the Necrosome Ripk1-Ripk3 Core, A Human Hetero-Amyloid Signaling Complex. Cell (2018) 173:1244–53.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.032

36. Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao D, et al. Mixed Lineage Kinase Domain-Like Protein Mediates Necrosis Signaling Downstream of RIP3 Kinase. Cell (2012) 148:213–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.031

37. Wang H, Sun L, Su L, Rizo J, Liu L, Wang LF, et al. Mixed Lineage Kinase Domain-Like Protein MLKL Causes Necrotic Membrane Disruption Upon Phosphorylation by RIP3. Mol Cell (2014) 54:133–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.003

38. Newton K, Wickliffe KE, Dugger DL, Maltzman A, Roose-Girma M, Dohse M, et al. Cleavage of RIPK1 by Caspase-8 Is Crucial for Limiting Apoptosis and Necroptosis. Nature (2019) 574:428–31. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1548-x

39. Zhang X, Dowling JP, Zhang J. RIPK1 can Mediate Apoptosis in Addition to Necroptosis During Embryonic Development. Cell Death Dis (2019) 10:245. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1490-8

40. Kelliher MA, Grimm S, Ishida Y, Kuo F, Stanger BZ, Leder P. The Death Domain Kinase RIP Mediates the TNF-Induced NF-Kappa B Signal. Immunity (1998) 8:297–303. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80535-X

41. Takahashi N, Vereecke L, Bertrand MJ, Duprez L, Berger SB, Divert T, et al. RIPK1 Ensures Intestinal Homeostasis by Protecting the Epithelium Against Apoptosis. Nature (2014) 513:95–9. doi: 10.1038/nature13706

42. Dannappel M, Vlantis K, Kumari S, Polykratis A, Kim C, Wachsmuth L, et al. RIPK1 Maintains Epithelial Homeostasis by Inhibiting Apoptosis and Necroptosis. Nature (2014) 513:90–4. doi: 10.1038/nature13608

43. Polykratis A, Hermance N, Zelic M, Roderick J, Kim C, Van TM, et al. Cutting Edge: RIPK1 Kinase Inactive Mice Are Viable and Protected From TNF-Induced Necroptosis In Vivo. J Immunol (2014) 193:1539–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400590

44. Shutinoski B, Alturki NA, Rijal D, Bertin J, Gough PJ, Schlossmacher MG, et al. K45A Mutation of RIPK1 Results in Poor Necroptosis and Cytokine Signaling in Macrophages, Which Impacts Inflammatory Responses In Vivo. Cell Death Differ (2016) 23:1628–37. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.51

45. Liu Y, Fan C, Zhang Y, Yu X, Wu X, Zhang X, et al. RIP1 Kinase Activity-Dependent Roles in Embryonic Development of Fadd-Deficient Mice. Cell Death Differ (2017) 24:1459–69. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.78

46. Meng H, Liu Z, Li X, Wang H, Jin T, Wu G, et al. Death-Domain Dimerization-Mediated Activation of RIPK1 Controls Necroptosis and RIPK1-Dependent Apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2018) 115:E2001–E09. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1722013115

47. Varfolomeev EE, Schuchmann M, Luria V, Chiannilkulchai N, Beckmann JS, Mett IL, et al. Targeted Disruption of the Mouse Caspase 8 Gene Ablates Cell Death Induction by the TNF Receptors, Fas/Apo1, and DR3 and Is Lethal Prenatally. Immunity (1998) 9:267–76. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80609-3

48. Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Long AB, Livingston-Rosanoff D, Daley-Bauer LP, Hakem R, et al. RIP3 Mediates the Embryonic Lethality of Caspase-8-Deficient Mice. Nature (2011) 471:368–72. doi: 10.1038/nature09857

49. Oberst A, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Mccormick LL, Fitzgerald P, Pop C, et al. Catalytic Activity of the Caspase-8-FLIP(L) Complex Inhibits RIPK3-Dependent Necrosis. Nature (2011) 471:363–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09852

50. Alvarez-Diaz S, Dillon CP, Lalaoui N, Tanzer MC, Rodriguez DA, Lin A, et al. The Pseudokinase MLKL and the Kinase Ripk3 Have Distinct Roles in Autoimmune Disease Caused by Loss of Death-Receptor-Induced Apoptosis. Immunity (2016) 45:513–26. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.016

51. Fritsch M, Gunther SD, Schwarzer R, Albert MC, Schorn F, Werthenbach JP, et al. Caspase-8 Is the Molecular Switch for Apoptosis, Necroptosis and Pyroptosis. Nature (2019) 575:683–87. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1770-6

52. Lawlor KE, Khan N, Mildenhall A, Gerlic M, Croker BA, D’cruz AA, et al. RIPK3 Promotes Cell Death and NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in the Absence of MLKL. Nat Commun (2015) 6:6282. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7282

53. Degterev A, Maki JL, Yuan J. Activity and Specificity of Necrostatin-1, Small-Molecule Inhibitor of RIP1 Kinase. Cell Death Differ (2013) 20:366. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.133

54. Degterev A, Ofengeim D, Yuan J. Targeting RIPK1 for the Treatment of Human Diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2019) 116:9714–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901179116

55. Lachmann HJ, Kone-Paut I, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Leslie KS, Hachulla E, Quartier P, et al. Use of Canakinumab in the Cryopyrin-Associated Periodic Syndrome. N Engl J Med (2009) 360:2416–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810787

56. Goldbach-Mansky R, Dailey NJ, Canna SW, Gelabert A, Jones J, Rubin BI, et al. Neonatal-Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disease Responsive to Interleukin-1beta Inhibition. N Engl J Med (2006) 355:581–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055137

57. Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Regulation of NF-kappaB by TNF Family Cytokines. Semin Immunol (2014) 26:253–66. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.05.004

58. Gerlag DM, Ransone L, Tak PP, Han Z, Palanki M, Barbosa MS, et al. The Effect of a T Cell-Specific NF-Kappa B Inhibitor on In Vitro Cytokine Production and Collagen-Induced Arthritis. J Immunol (2000) 165:1652–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1652

59. Konig N, Fiehn C, Wolf C, Schuster M, Cura Costa E, Tungler V, et al. Familial Chilblain Lupus Due to a Gain-of-Function Mutation in STING. Ann Rheum Dis (2017) 76:468–72. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209841

60. Van Eyck L Jr., Hershfield MS, Pombal D, Kelly SJ, Ganson NJ, Moens L, et al. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Rescues the Immunologic Phenotype and Prevents Vasculopathy in Patients With Adenosine Deaminase 2 Deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2015) 135:283–7.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.010

61. Neven B, Valayannopoulos V, Quartier P, Blanche S, Prieur AM, Debre M, et al. Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplantation in Mevalonic Aciduria. N Engl J Med (2007) 356:2700–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070715

62. Miot C, Imai K, Imai C, Mancini AJ, Kucuk ZY, Kawai T, et al. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in 29 Patients Hemizygous for Hypomorphic IKBKG/NEMO Mutations. Blood (2017) 130:1456–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-03-771600

63. Aksentijevich I, Zhou Q. NF-Kappab Pathway in Autoinflammatory Diseases: Dysregulation of Protein Modifications by Ubiquitin Defines a New Category of Autoinflammatory Diseases. Front Immunol (2017) 8:399. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00399

64. Mcdermott MF, Aksentijevich I, Galon J, Mcdermott EM, Ogunkolade BW, Centola M, et al. Germline Mutations in the Extracellular Domains of the 55 KDA TNF Receptor, TNFR1, Define a Family of Dominantly Inherited Autoinflammatory Syndromes. Cell (1999) 97:133–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80721-7

65. Cudrici C, Deuitch N, Aksentijevich I. Revisiting TNF Receptor-Associated Periodic Syndrome (TRAPS): Current Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(9):3263. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093263

66. Lobito AA, Kimberley FC, Muppidi JR, Komarow H, Jackson AJ, Hull KM, et al. Abnormal Disulfide-Linked Oligomerization Results in ER Retention and Altered Signaling by TNFR1 Mutants in TNFR1-Associated Periodic Fever Syndrome (TRAPS). Blood (2006) 108:1320–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-006783

67. Bulua AC, Simon A, Maddipati R, Pelletier M, Park H, Kim KY, et al. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Promote Production of Proinflammatory Cytokines and are Elevated in TNFR1-Associated Periodic Syndrome (TRAPS). J Exp Med (2011) 208:519–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102049

68. Zonana J, Elder ME, Schneider LC, Orlow SJ, Moss C, Golabi M, et al. A Novel X-Linked Disorder of Immune Deficiency and Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia is Allelic to Incontinentia Pigmenti and Due to Mutations in IKK-Gamma (Nemo). Am J Hum Genet (2000) 67:1555–62. doi: 10.1086/316914

69. Keller MD, Petersen M, Ong P, Church J, Risma K, Burham J, et al. Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia and Immunodeficiency With Coincident NEMO and EDA Mutations. Front Immunol (2011) 2:61. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00061

70. Tokunaga F, Nishimasu H, Ishitani R, Goto E, Noguchi T, Mio K, et al. Specific Recognition of Linear Polyubiquitin by A20 Zinc Finger 7 Is Involved in NF-kappaB Regulation. EMBO J (2012) 31:3856–70. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.241

71. Zhou Q, Wang H, Schwartz DM, Stoffels M, Park YH, Zhang Y, et al. Loss-of-Function Mutations in TNFAIP3 Leading to A20 Haploinsufficiency Cause an Early-Onset Autoinflammatory Disease. Nat Genet (2016) 48:67–73. doi: 10.1038/ng.3459

72. Aeschlimann FA, Batu ED, Canna SW, Go E, Gul A, Hoffmann P, et al. A20 Haploinsufficiency (HA20): Clinical Phenotypes and Disease Course of Patients With a Newly Recognised NF-kB-Mediated Autoinflammatory Disease. Ann Rheum Dis (2018) 77:728–35. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212403

73. Boisson B, Laplantine E, Prando C, Giliani S, Israelsson E, Xu Z, et al. Immunodeficiency, Autoinflammation and Amylopectinosis in Humans With Inherited HOIL-1 and LUBAC Deficiency. Nat Immunol (2012) 13:1178–86. doi: 10.1038/ni.2457

74. Boisson B, Laplantine E, Dobbs K, Cobat A, Tarantino N, Hazen M, et al. Human HOIP and LUBAC Deficiency Underlies Autoinflammation, Immunodeficiency, Amylopectinosis, and Lymphangiectasia. J Exp Med (2015) 212:939–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141130

75. Damgaard RB, Walker JA, Marco-Casanova P, Morgan NV, Titheradge HL, Elliott PR, et al. The Deubiquitinase Otulin Is an Essential Negative Regulator of Inflammation and Autoimmunity. Cell (2016) 166:1215–30 e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.019

76. Zhou Q, Yu X, Demirkaya E, Deuitch N, Stone D, Tsai WL, et al. Biallelic Hypomorphic Mutations in a Linear Deubiquitinase Define Otulipenia, an Early-Onset Autoinflammatory Disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2016) 113:10127–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612594113

77. Gaidt MM, Ebert TS, Chauhan D, Schmidt T, Schmid-Burgk JL, Rapino F, et al. Human Monocytes Engage an Alternative Inflammasome Pathway. Immunity (2016) 44:833–46. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.01.012

78. Kang TB, Yang SH, Toth B, Kovalenko A, Wallach D. Caspase-8 Blocks Kinase RIPK3-Mediated Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Immunity (2013) 38:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.015

79. Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis: Death by Lipid Peroxidation. Free Radical Bio Med (2018) 120:S7–7. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.04.034

80. Zhang YY, Su SS, Zhao SB, Yang ZT, Zhong CQ, Chen X, et al. RIP1 Autophosphorylation is Promoted by Mitochondrial ROS and Is Essential for RIP3 Recruitment Into Necrosome. Nat Commun (2017) 8:14329. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14329

81. Liang C, Zhang X, Yang M, Dong X. Recent Progress in Ferroptosis Inducers for Cancer Therapy. Adv Mater (2019) 31:e1904197. doi: 10.1002/adma.201904197

82. Van Linthout S, Miteva K, Tschope C. Crosstalk Between Fibroblasts and Inflammatory Cells. Cardiovasc Res (2014) 102:258–69. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu062

83. Buckley CD, Pilling D, Lord JM, Akbar AN, Scheel-Toellner D, Salmon M. Fibroblasts Regulate the Switch From Acute Resolving to Chronic Persistent Inflammation. Trends Immunol (2001) 22:199–204. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01863-4

Keywords: RIPK1, programmed cell death, immunodeficiency, autoinflammatory disease, CRIA, biological therapies

Citation: Zhang J, Jin T, Aksentijevich I and Zhou Q (2021) RIPK1-Associated Inborn Errors of Innate Immunity. Front. Immunol. 12:676946. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.676946

Received: 06 March 2021; Accepted: 24 May 2021;

Published: 07 June 2021.

Edited by:

Nobuo Kanazawa, Hyogo College of Medicine, JapanReviewed by:

Fuminori Tokunaga, Osaka City University, JapanNajoua Lalaoui, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Australia

Copyright © 2021 Zhang, Jin, Aksentijevich and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qing Zhou, emhvdXEyQHpqdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Jiahui Zhang

Jiahui Zhang Taijie Jin

Taijie Jin Ivona Aksentijevich

Ivona Aksentijevich Qing Zhou

Qing Zhou