- 1Department of Infectious Disease, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

- 2Innovation for Health and Development (IFHAD), Laboratory of Research and Development, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru

- 3Innovacion Por la Salud Y el Desarrollo (IPSYD), Asociación Benéfica PRISMA, Lima, Peru

- 4Department of Pulmonology and Tuberculosis, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

Background: Whole blood mycobacterial growth assays (WBMGA) quantify mycobacterial growth in fresh blood samples and may have potential for assessing tuberculosis vaccines and identifying individuals at risk of tuberculosis. We evaluated the evidence for the underlying assumption that in vitro WBMGA results can predict in vivo tuberculosis susceptibility.

Methods: A systematic search was done for studies assessing associations between WBMGA results and tuberculosis susceptibility. Meta-analyses were performed for eligible studies by calculating population-weighted averages.

Results: No studies directly assessed whether WBMGA results predicted tuberculosis susceptibility. 15 studies assessed associations between WBMGA results and proven correlates of tuberculosis susceptibility, which we divided in two categories. Firstly, WBMGA associations with factors believed to reduce tuberculosis susceptibility were statistically significant in all eight studies of: BCG vaccination; vitamin D supplementation; altitude; and HIV-negativity/therapy. Secondly, WBMGA associations with probable correlates of tuberculosis susceptibility were statistically significant in three studies of tuberculosis disease, in a parasitism study and in two of the five studies of latent tuberculosis infection. Meta-analyses for associations between WBMGA results and BCG vaccination, tuberculosis infection, tuberculosis disease and HIV infection revealed consistent effects. There was considerable methodological heterogeneity.

Conclusions: The study results generally showed significant associations between WBMGA results and correlates of tuberculosis susceptibility. However, no study directly assessed whether WBMGA results predicted actual susceptibility to tuberculosis infection or disease. We recommend optimization and standardization of WBMGA methodology and prospective studies to determine whether WBMGA predict susceptibility to tuberculosis disease.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is estimated to make more than ten million people ill and to kill 1.4 million people each year globally (1). A quarter of the world population are believed to have latent TB infection (LTBI), in >90% of whom antimycobacterial immunity is expected to indefinitely prevent progression to TB disease. Several risk factors for progression from exposure to LTBI to active TB disease have been identified (2), but reliable predictors are lacking (3). Risk stratification, assessment of vaccines and other interventions aiming to reduce TB susceptibility are all complicated by the variable and often long delay from infection to disease and by difficulty determining TB exposure, infection and disease (4, 5). Consequently, there is an urgent need for in vitro assays to predict in vivo TB susceptibility.

Whole blood mycobacterial growth assays (WBMGA) aim to measure in vitro growth of mycobacteria in fresh blood samples. They are functional assays that, instead of focusing on a single immune marker, assess the combined effects of a range of factors such as immune mechanisms that influence mycobacterial growth in vitro. WBMGA have gained interest for TB vaccine testing, where pre- and post-vaccination assays may provide information about the efficacy of vaccine candidates, predicting individuals at risk of TB disease (6, 7). The underlying assumption is that if in vitro an individual’s blood allows greater mycobacterial growth then this finding predicts that individual to be at greater risk of developing TB infection or disease i.e., in vivo TB susceptibility.

In addition to WBMGA, mycobacterial growth assays have been developed and assessed using purified peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), purified macrophages, and bronchoalveolar lavage cells (6). In the current systematic review, we focused on WBMGA because of several advantages it offers compared to the PBMC-based mycobacterial growth assay: 1. the simplicity of WBMGA increases feasibility in the resource-constrained settings where most TB occurs (8); 2. whole-blood assays reduce the artefactual effects of cell-isolation procedures; and 3. the WBMGA is the in vitro approach that appears to best represent the complexities of in vivo responses, including the role of hemoglobin, neutrophilic granulocytes, antibodies and complement, which may explain the disagreement in results between WBMGA and equivalent assays using purified PBMC (9, 10).

Two main types of WBMGA have been used. Firstly, in the BCG lux assay, recombinant luminescent mycobacteria (BCG lux) are inoculated in diluted whole blood and a mycobacterial growth rate is calculated by measuring emitted light at the time of inoculation versus after incubation (11). Secondly, in the mycobacterial growth inhibition tube (MGIT) assay (12), mycobacteria are cultured in diluted whole blood, after which the mycobacteria are isolated and inoculated into BACTEC (Becton and Dickinson, Sparks, USA) MGIT culture tubes to assess time to mycobacterial detection, indicative of mycobacterial growth. WBMGA have used different blood supplements; infection with various M. tuberculosis strains and both wild-type or genetically modified BCG; incubation for 72-96 hours; and diverse outcome measures (e.g., mycobacterial time to culture positivity and mycobacterial bioluminescence indicating metabolism).

The central premise of a useful WBMGA is that mycobacterial growth measured in vitro predicts the in vivo risk of developing TB infection or active TB disease. Recently, the technical details of diverse WBMGA (and mycobacterial growth assays based on peripheral blood mononuclear cells) were reviewed (6). Our current review aims to extend these findings to determine what, if any evidence exists that human WBMGA results in vitro predict risk of TB in vivo. We aimed to include all types of human participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study designs (PICOS) with relevance to our objective (13).

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

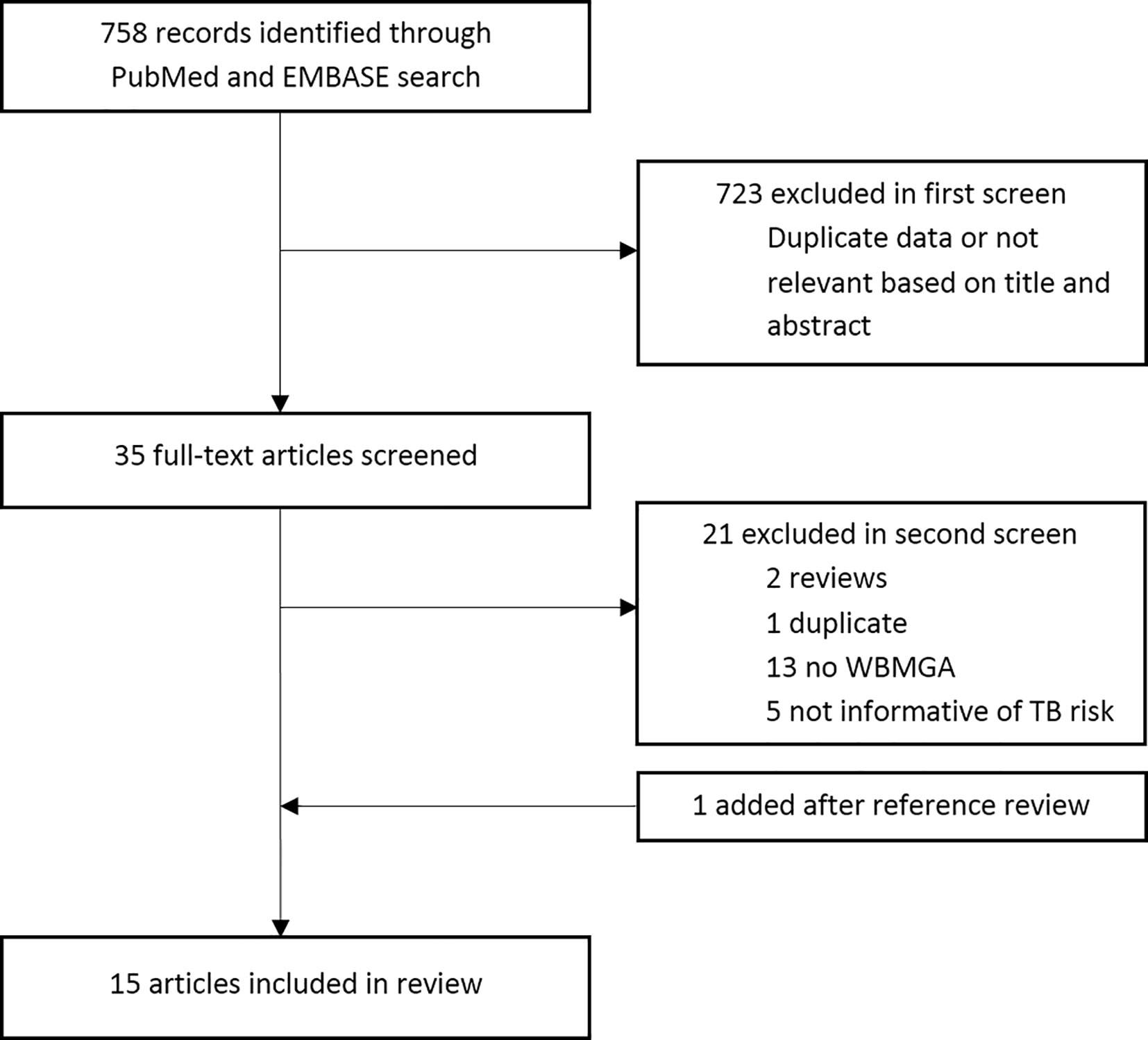

The search strategy is available at this link: http://www.ifhad.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/WBMGA_review_search_strategy.pdf. The systematic review protocol is available at this link: http://www.ifhad.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/WBMGA_review_protocol.pdf. The systematic review and meta-analysis registration is available at this link: http://www.ifhad.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Systematic_review__meta-analysis_registration_submitted_to_PROSPERO.pdf. This review followed the PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses (13). PubMed and EMBASE were searched until 25th June 2020. References cited by these publications and reviews were searched. Inclusion criteria were: peer-reviewed, English-language publications that described cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort studies using WBMGA to study mycobacterial growth in human blood in relation to risk of TB infection; risk of TB disease; established or possible TB risk factors. JB and CAE reviewed potentially relevant publication titles, then abstracts and finally full-text publications for eligibility (Figure 1). Quality of the included studies was evaluated by JB and RH using a quality assessment tool from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), leading to an overall rating for the quality of each study of “good”, “fair”, or “poor” (14). Although derived for larger scale observational and cohort studies, this quality assessment tool seemed to be the best available option considering our inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Data Analysis and Synthesis of Findings

WBMGA results, study characteristics and methodology were extracted from each publication and categorized by factors known to decrease or likely to affect TB susceptibility by JB and CE. WBMGA results were extracted as published, regardless of calculation or methodological differences.

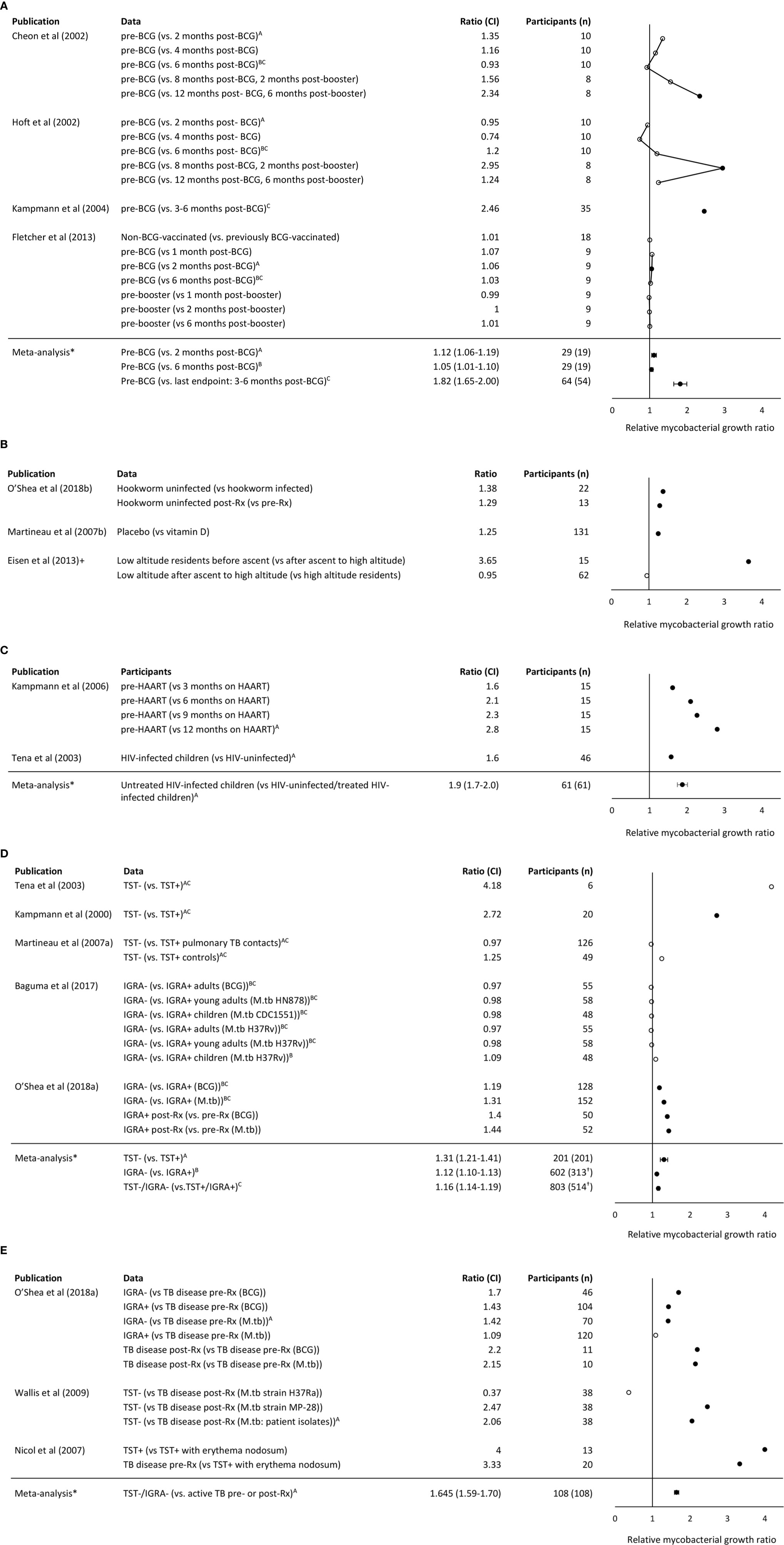

To allow comparison and synthesis of WBMGA results between different studies, ratios of one study group (e.g., pre-vaccination) versus the other (e.g., post-vaccination) were calculated for each of the main findings of the publications, generating relative mycobacterial growth ratios that are presented in Figures 2A–E.

Figure 2 (A) Relative mycobacterial growth ratios of comparisons made in studies of BCG vaccination. (B) Relative mycobacterial growth ratios of comparisons made in studies of parasitism, vitamin D, and altitude, respectively. +Note the Eisen et al. (8) considered growth relative to control samples to adjust for altitude effects on mycobacterial growth. (C) Relative mycobacterial growth ratios of comparisons made in studies of HIV and its treatment. (D) Relative mycobacterial growth ratios of comparisons made in studies of TB infection. †Approximation of population (E) Relative mycobacterial growth ratios of comparisons made in studies of TB disease. Note that higher relative mycobacterial growth ratio indicates greater mycobacterial growth so may be interpreted as implying relative susceptibility to mycobacterial infection in the participants listed without parentheses (compared with the participants listed in parentheses). Filled circles indicate P <0. 05. Meta-analysis mean and confidence interval methodology are explained in the Methods. BCG indicates Bacille Calmette Guerin. IGRA indicates the Interferon- γ release assay. *Comparisons included in the meta-analysis are marked with the corresponding letter (A–C).

When different WBMGA methodologies were used concurrently to assess a patient then the level of agreement between the methodologies was assessed with scatter plots and Pearson correlation coefficients.

Meta-Analysis

Because of heterogeneity in statistical methods and lack of availability of participant-level data, standard deviations/errors could not be reliably estimated for each of the relative mycobacterial growth ratios that we calculated. Consequently, frequently used meta-analysis techniques incorporating study variances were impossible. Instead, for comparable studies we report averages of the relative mycobacterial growth ratios that we calculated weighted according to the number of participants in each study.

The equation used to calculate the weighted means was:

The equation used to calculate the standard error of weighted means was:

The standard errors of these weighted averages indicate the variation between individual studies and could not assess the variation within each study. These calculations used the R package “Hmisc” (15).

Heterogeneity was assessed visually with a histogram showing the log10 relative mycobacterial growth ratios in individual studies, indicating potential publication bias. Because the variance of each relative mycobacterial growth ratio was unknown, a conventional funnel plot could not be made. We therefore generated what we termed a pseudo-funnel plot of the log10 of the weighted means of relative mycobacterial growth ratios graphed against their standard errors, indicating potential publication bias in the weighted averages that we calculated.

Results

Results of Search

No prospective studies were found directly comparing WBMGA results with risk of TB infection or TB disease. Therefore, this review is limited to indirect evidence of studies testing associations between WBMGA results and factors believed to affect TB susceptibility. Fifteen articles meeting these criteria were included (Figure 1). A distinction was made between: (A) factors with consensus that they decrease TB susceptibility; and (B) factors likely affecting TB susceptibility but that lack consensus on whether they would increase or decrease susceptibility.

A. Factors Decreasing TB Susceptibility

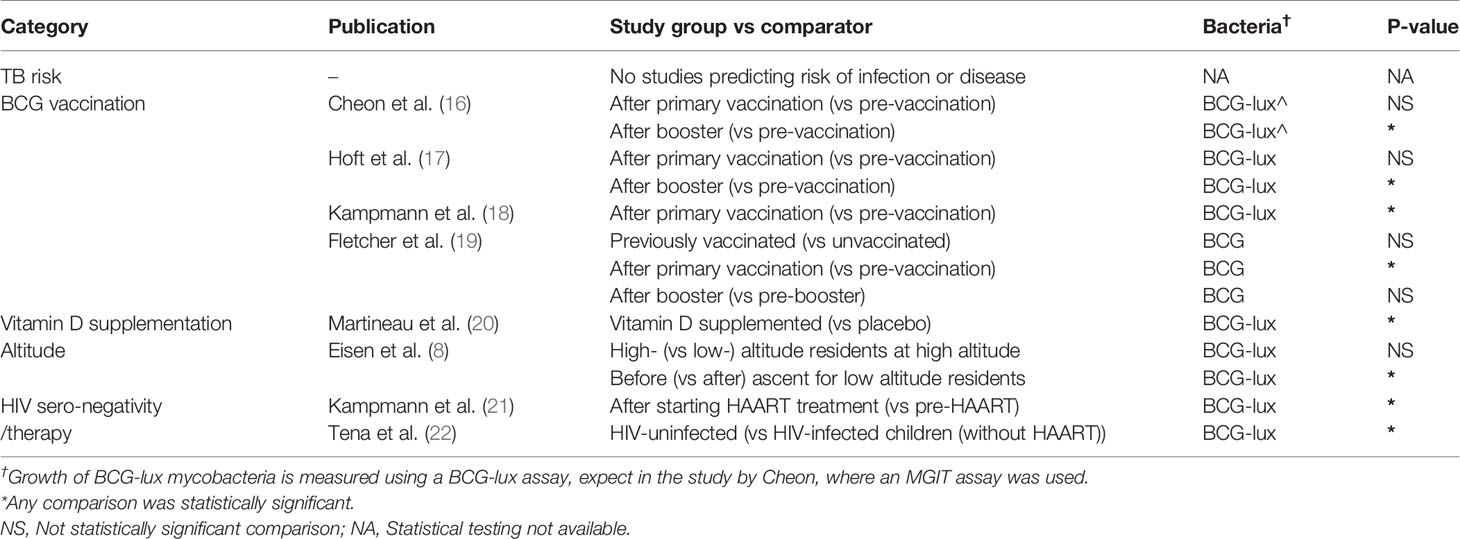

Table 1A shows study results grouped according to the following factors believed to decrease TB susceptibility: BCG vaccination; vitamin D; altitude; and HIV negativity/therapy, all of which are summarized immediately below.

Table 1A Overview of factors believed to decrease TB susceptibility and their association with less mycobacterial growth in WBMGA.

BCG Vaccination

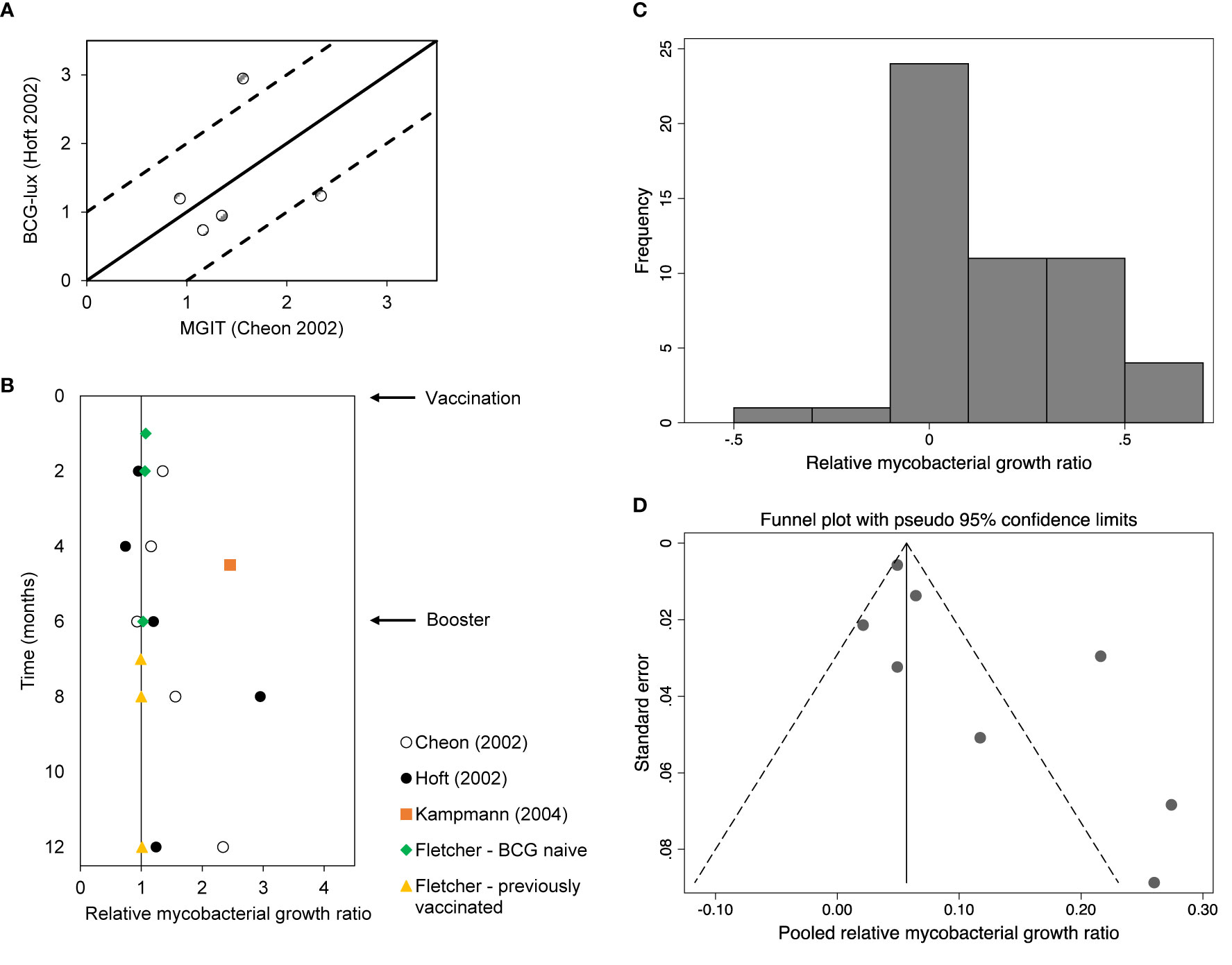

BCG vaccination can offer protection of 60-80% against severe disseminated childhood TB, whereas protection against pulmonary TB varied considerably between studies (23). In the present review, three studies were identified that compared WBMGA pre- versus post-BCG-vaccination (Figure 2A). The BCG-lux technique demonstrated significantly decreased mycobacterial growth two months after secondary (8 months after primary) BCG vaccination in adults, but no significant effects persisted later (17). Concurrently the same blood samples (personal communication with Dr. Daniel Hoft) were tested with the MGIT technique, showing significantly decreased mycobacterial growth only six months after secondary (12 months after primary) BCG vaccination (16). The differences in relative mycobacterial growth at different time points between these studies are illustrated in Figure 3A, with a more than twofold difference at two time points. Significantly reduced mycobacterial growth in adults was reported only after primary vaccination of a cohort of BCG-naïve adults (although this depended on the statistical method) but no difference after secondary vaccination of a cohort of adults who had been vaccinated more than six months before enrolment (19). In the same study no difference in mycobacterial growth was found between the previously BCG-vaccinated versus the non-BCG-vaccinated groups at baseline. Reduced mycobacterial growth was also reported after neonatal BCG-vaccination (18). In Figure 3B, relative mycobacterial growth at different time points post-BCG vaccination are compared across all included studies.

Figure 3 (A) Relative mycobacterial growth (ratios) of BCG vaccination studies using the same population but different assays. The solid line represents no difference between assay results. The dotted lines represent a 2-fold difference between assay results. (B) Relative mycobacterial growth (ratios) of BCG vaccination studies per month post-vaccination. (C) Histogram of log10 of relative mycobacterial growth ratios. Note this refers to the ratios as presented in Figures 2A–E. (D) Pseudo-funnel plot (see Methods).

Vitamin D

Low serum levels of vitamin D have been associated with an increased risk of TB disease (24). In the only study identified that analyzed vitamin D and WBMGA, in a randomized controlled trial a single dose of a vitamin D significantly reduced mycobacterial growth compared to placebo (Figure 2B) (20).

Altitude

High altitude is associated with lower risk of TB infection and disease (25, 26) and decreased mycobacterial growth was reported in low-altitude residents after ascent to high altitude, sufficient for there to be no difference between recently ascended individuals and permanent high-altitude residents (Figure 2B) (8).

HIV Negativity/Therapy

HIV infection is one of the strongest risk factors for progression to active TB disease (27). Two studies were identified that investigated WBMGA in relation to HIV infection (Figure 2C). Higher mycobacterial growth in HIV-infected children (without highly active antiretroviral therapy, HAART) was reported compared to HIV-uninfected children (22). Similarly, a significant decline in mycobacterial growth was reported after starting HAART in HIV-infected children (21).

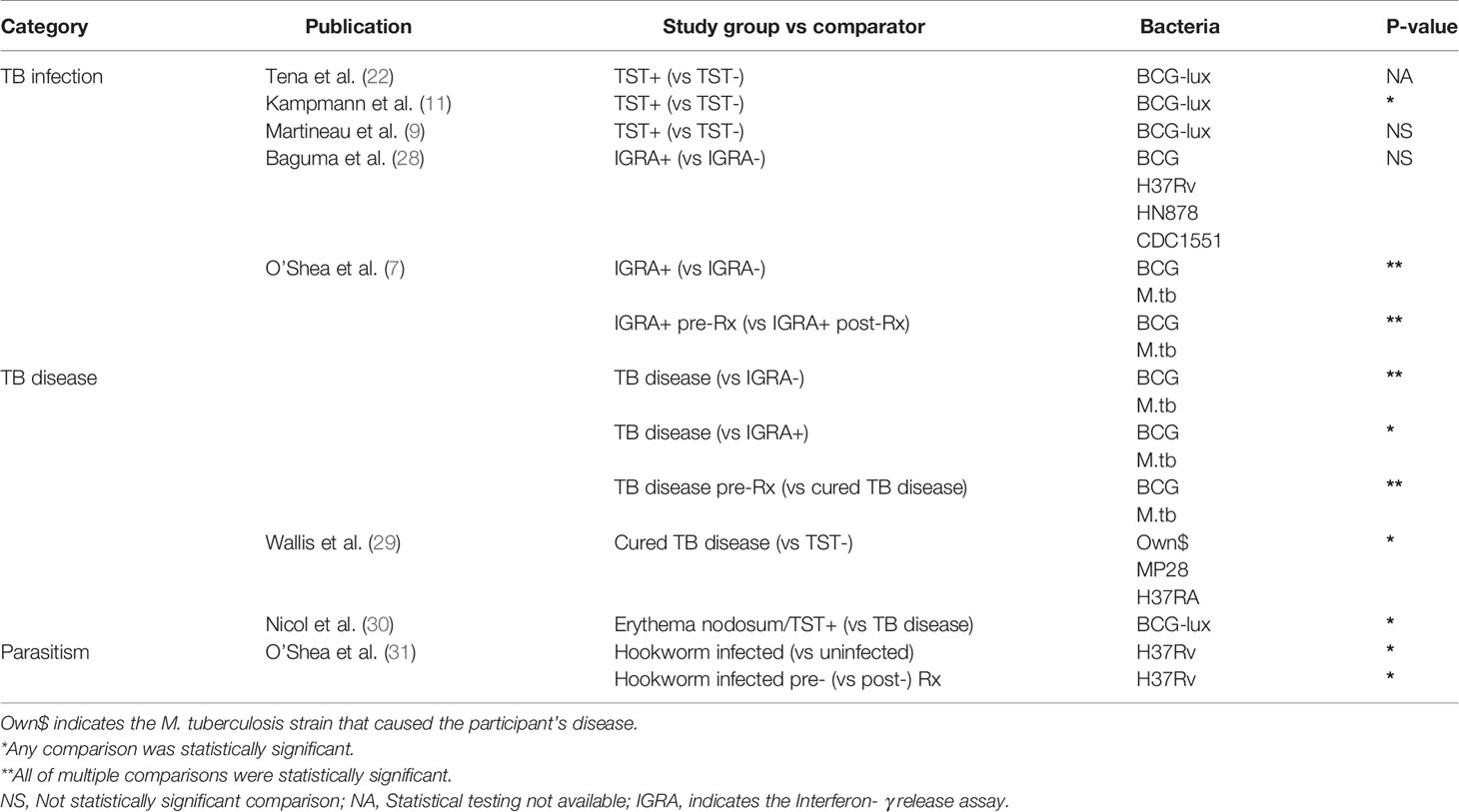

B. Factors Likely Affecting TB Susceptibility

Table 1B shows study results grouped according to the following factors likely to affect TB susceptibility: TB infection, TB disease, and parasitism.

Table 1B Overview of results of factors that may affect TB susceptibility and their association with less mycobacterial growth in WBMGA.

TB Infection

Five studies were identified that analyzed the association between WBMGA and TB infection status, i.e., absence of infection indicated by negative tuberculin skin test (TST) and/or Interferon- γ release assay (IGRA) results versus TB infection (positive TST and/or IGRA) (Figure 2D). Three of these studies compared TST-positive versus TST-negative populations. Lower mycobacterial growth was reported in TST-positive versus TST-negative individuals, although statistical significance was not reported (22). Decreased mycobacterial growth was reported in TST-positive adults versus TST-negative adults (11). No significant difference in mycobacterial growth was found comparing TST-positive versus TST-negative adult contacts of patients diagnosed with pulmonary TB in a study designed to assess the role of neutrophils in host resistance to mycobacterial infection (9). Two other studies compared IGRA-positive and IGRA-negative populations. One found no significant difference in mycobacterial growth between IGRA-positive versus IGRA-negative children and adults in a high TB burden setting (28); the other reported significantly lower mycobacterial growth in IGRA-positive compared to IGRA-negative individuals and an increase in mycobacterial growth after treatment of IGRA-positive individuals (7).

TB Disease

Three studies reported the association between WBMGA and TB disease (Figure 2E). Patients with TB disease showed lowest mycobacterial growth, followed by IGRA-positive individuals, with highest mycobacterial growth in IGRA-negative individuals, although these associations were only observed when the mycobacteria used in the assay were BCG, not M. tuberculosis (7). Mycobacterial growth in patients cured of TB was less than TB-naïve individuals for two tested M. tuberculosis strains, but no significant difference was observed for a third M. tuberculosis strain (29). TST-positive children with erythema nodosum, a condition that was usually attributed TB infection in the setting of this study, showed less mycobacterial growth in WBMGA than children with active TB (30).

Parasitism

The evidence concerning the direction of the association between parasitism and risk of TB infection and TB disease is conflicting i.e. parasitism may be associated with decreased (31–33) or potentially (directly or indirectly through associated malnutrition) increased TB susceptibility (34, 35). One study was identified that examined the relation between helminth infections and WBMGA, which showed decreased mycobacterial growth in individuals with hookworm infection compared to hookworm-uninfected controls, which resolved after treatment of hookworm infection (Figure 2B) (31).

Relative Mycobacterial Growth Ratios and Meta-Analysis

Relative mycobacterial growth ratios from the studies related to BCG vaccination, TB infection, TB disease and HIV infection are shown in Figures 2A–D, respectively, with each of these figures including meta- analyses. Figure 2E shows relative mycobacterial growth ratios from the studies related to parasitism, vitamin D and altitude; none of which were amenable to meta-analysis. The meta-analyses showed the following:

● Mycobacterial growth in WBMGA was significantly reduced 2-6 months after primary BCG vaccination (Figure 2A). The available data concerning BCG booster vaccination were not amenable to meta-analysis (see legend to Figure 2A).

● Mycobacterial growth was significantly less for TB-infected than for TB-uninfected populations (whether infection was assessed by TST or IGRA, Figure 2B).

● Mycobacterial growth was significantly less for patients with TB disease (whether before or after treatment) than for TB-uninfected people (TST- or IGRA-negative, Figure 2C).

● Mycobacterial growth was significantly less in relatively immunocompetent people (whether HIV-uninfected people or HIV-infected people receiving HAART) than untreated people with HIV-infection (Figure 2D).

The histogram depicting the log10 of the relative mycobacterial growth ratios (Figure 3C) and the pseudo-funnel plot (Figure 3D) are both skewed right, which may indicate publication bias.

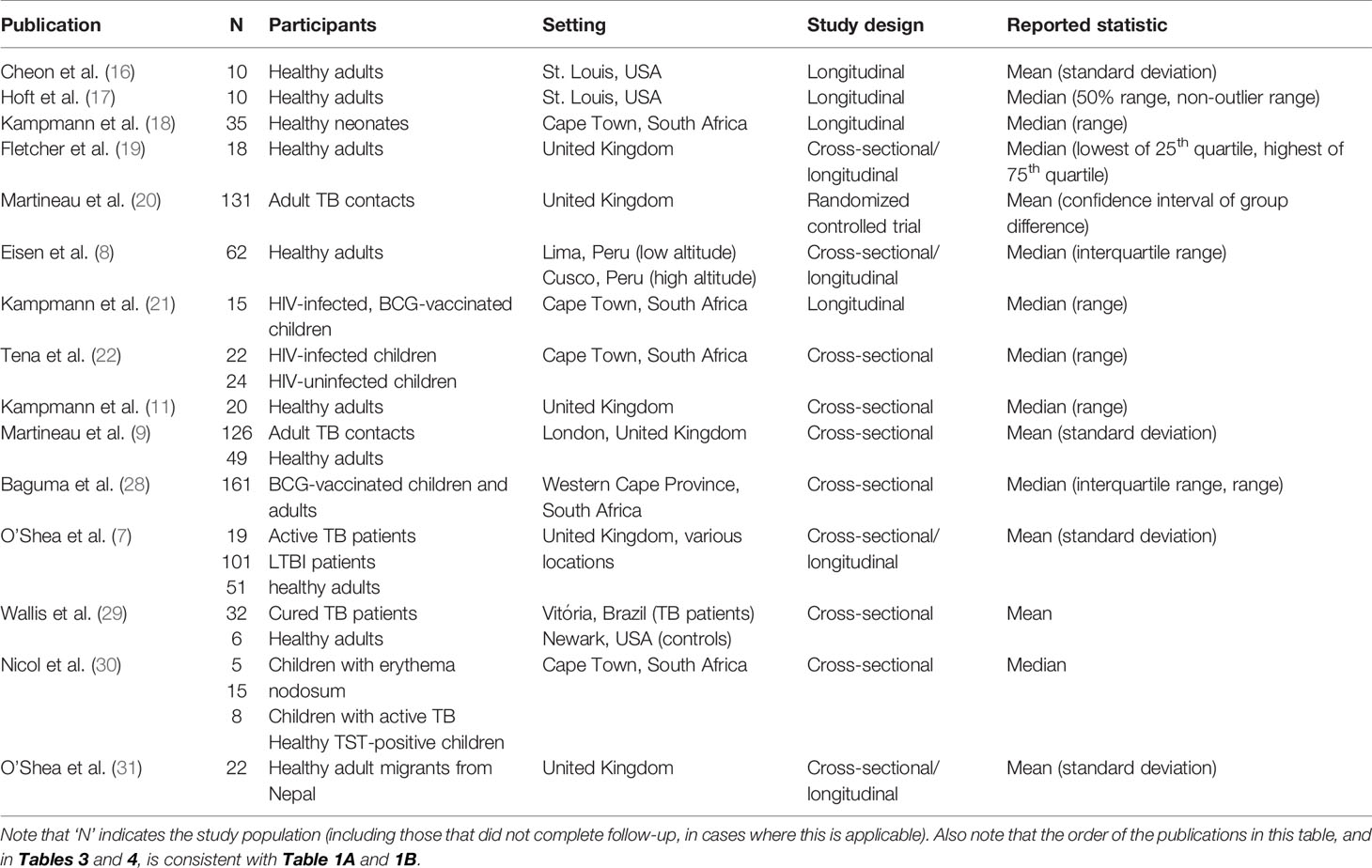

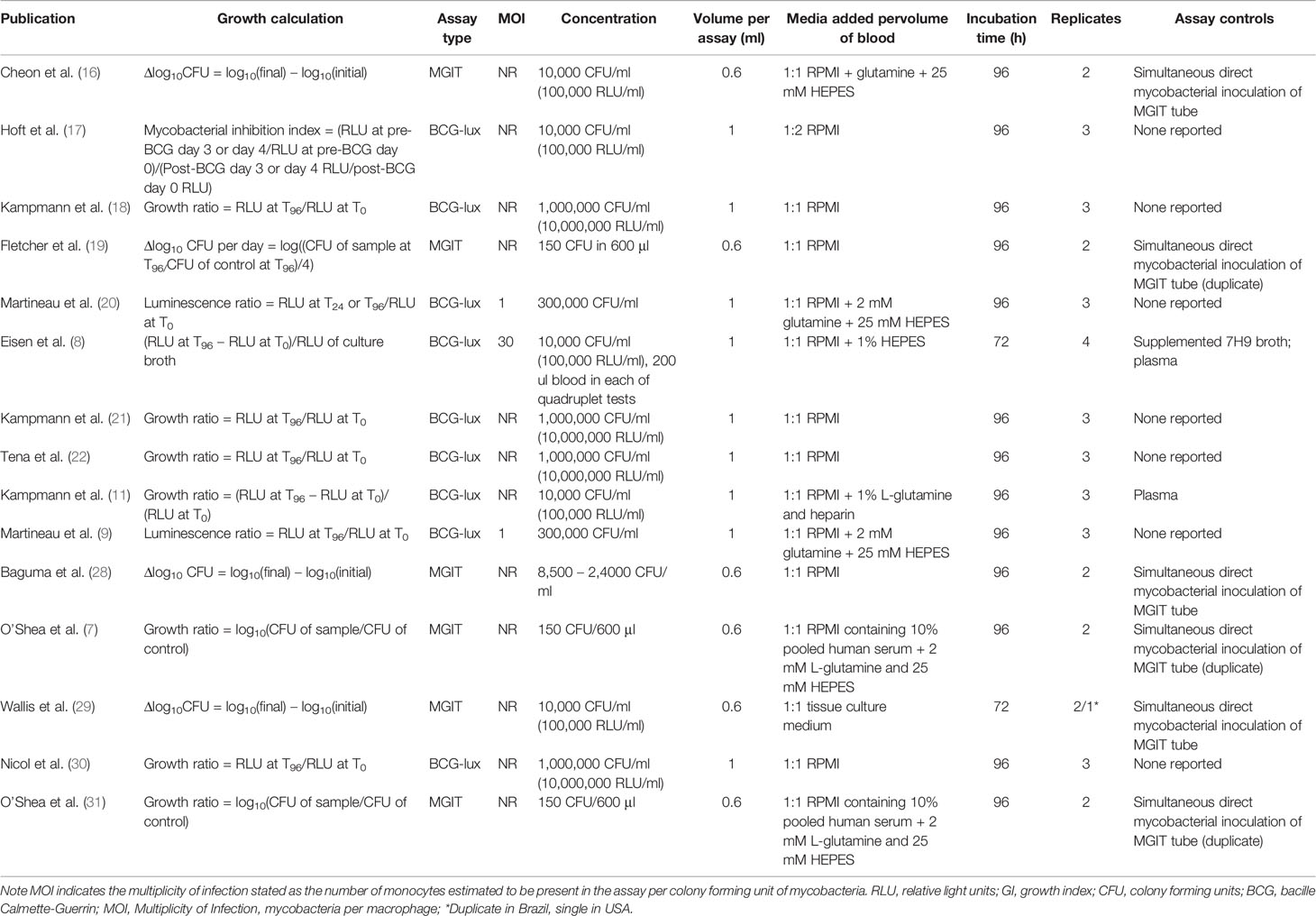

Study Characteristics and Assay Methodology

Study characteristics of the included studies and the WBMGA methodology that were used are presented in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Assay controls were used in 53% (eight of 15) of the included studies. Considerable heterogeneity in population, setting and reported statistics were found (Table 2). Methodological characteristics comparing studies, including concentrations of mycobacterial inoculate and the use of controls, were diverse (Table 3).

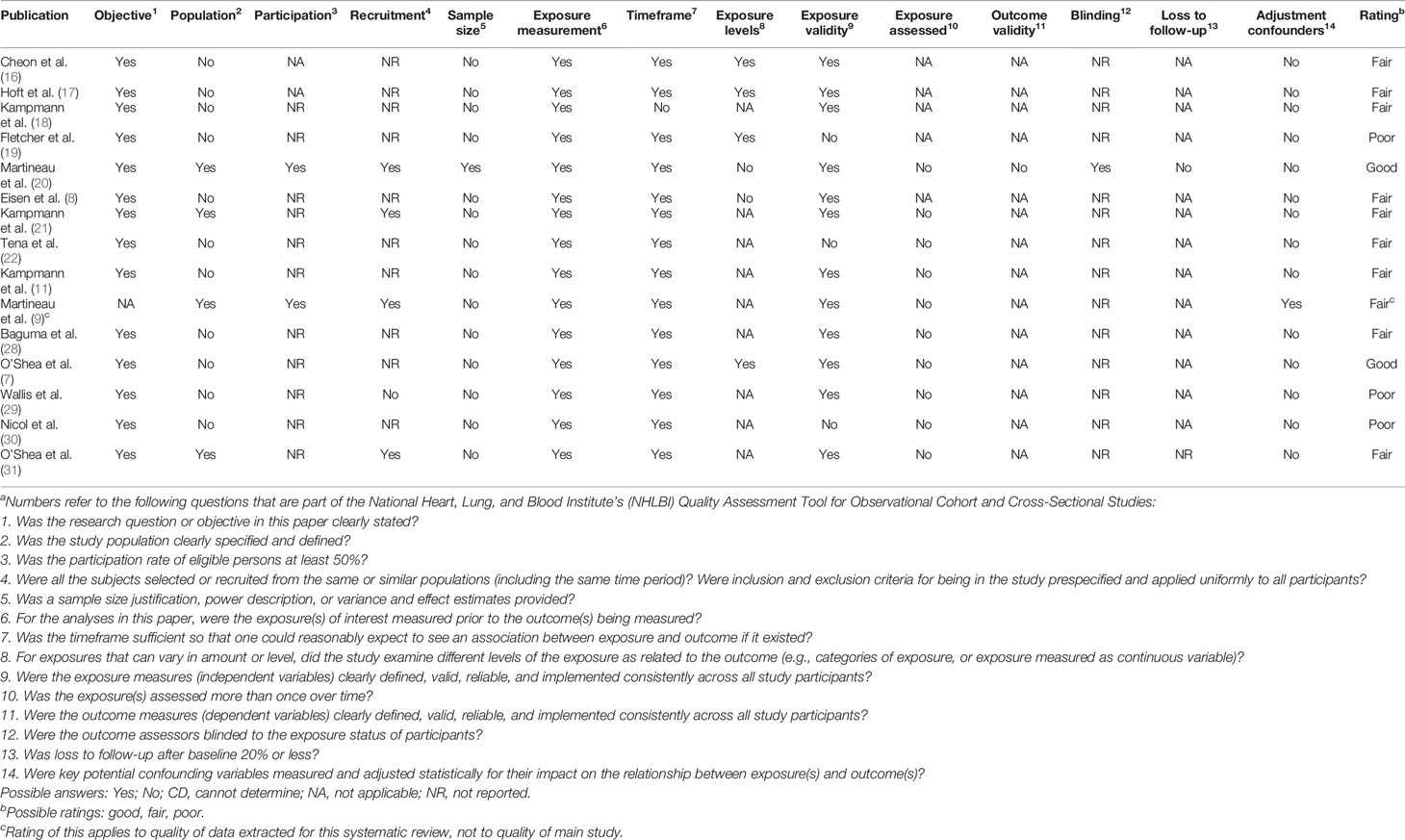

Study Quality

Table 4 shows the result of a study quality evaluation using a standardized quality assessment tool developed by NHLBI. Two of the included studies received a good rating, ten received a fair rating, and three received a poor rating.

Comparison of BCG-lux and MGIT Assay Results

Figure 3A shows differences between the results of BCG-lux and MGIT assays performed concurrently on the same whole blood samples. The Pearson correlation coefficient of the BCG-lux and MGIT assay results, presented as mycobacterial growth ratios, was 0.19 (R2 = 0.037). Two of five data points showed a more than two-fold difference in growth ratio.

Heterogeneity of BCG Vaccination Study Results

Figure 3B illustrates the heterogeneity of WBMGA results of BCG vaccination studies at different time points post-vaccination.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis assessed evidence that low mycobacterial growth in WBMGA predicted lower TB susceptibility. This demonstrated that less mycobacterial growth in vitro in WBMGA was indeed usually significantly associated with factors believed to reduce peoples’ TB susceptibility in vivo. Factors that are likely to affect TB susceptibility, but that lack consensus on whether they would increase or decrease susceptibility also generally showed significant and consistent associations with WBMGA results. This implies potential WBMGA value for clinical risk stratification and evaluation of TB vaccines, despite considerable clinical, laboratory and statistical heterogeneity across the included studies.

Developing biomarkers to predict TB risk is a priority for global TB elimination (1). Promising progress has been made recently, including identification of RNA and metabolic signatures (36, 37) and clinical risk scores (4, 5, 38). Growth assays aim to functionally assess host capacity to control infections, such as for example, malaria growth assays that predicted disease risk by a specific strain of Plasmodium falciparum (39). The emphasis of mycobacterial growth assay research has been on vaccine efficacy and immune mediator studies, with limited information on prospective risk of TB disease (6). Data on the relation between WBMGA and TB risk is thus limited to indirect evidence, which was assessed in this review.

By quantifying mycobacterial growth in vitro, WBMGA may be representative of the balance between factors influencing progression of mycobacterial infection versus containment of the infection through host antimycobacterial immunity. It is generally hypothesized that less mycobacterial growth in WBMGA in vitro implies immune restriction of mycobacteria and hence less TB susceptibility, i.e. a lower risk of TB infection or TB disease in vivo (6). In the current review, we found that WBMGA studies of factors believed to reduce TB susceptibility i.e., BCG vaccination, HIV negativity/therapy, vitamin D supplementation, and ascent to altitude largely supported this hypothesis. Although each of the included studies on BCG vaccination showed a significant association with WBMGA results, the time from vaccination until a significant inhibition of mycobacterial growth varied considerably, potentially because of methodological and population heterogeneity. Furthermore, although the protective efficacy of BCG vaccination against severe childhood TB is considerable, the protection it offers against pulmonary TB is variable and likely dependent on various host-dependent and environmental factors, including variations in exposure to environmental mycobacteria and BCG strains, confounding comparability and interpretation of these studies (23, 40). It is noteworthy that all WBMGA studies of BCG vaccination used BCG in vitro; thus assessment of the potential effect of BCG vaccination on M. tuberculosis growth in whole blood in vitro is awaited. It is unknown whether lower mycobacterial growth in vitro post-BCG vaccination implies long-term protection against TB disease rather than a temporary strengthening of adaptive antimycobacterial immunity or trained innate immunity (41).

The extent to which TB exposure and latent TB infection (LTBI) may affect susceptibility to TB disease caused by TB reactivation versus reinfection is debated (42). Currently the main tests to diagnose LTBI are TST and IGRA, which have limitations including indirectly assessing immunological memory rather than directly assessing actual infection (43). These tests only weakly predict the risk of subsequent TB disease and their results are influenced by factors including nutritional status and other causes of immunodeficiency (44, 45). An association might be expected between more mycobacterial growth in WBMGA (potentially implying greater TB susceptibility), leading to higher likelihood of LTBI, consistent with the proven association between LTBI and increased future TB risk. However, this hypothesis was not supported by any of the included studies. Rather, two of the five included studies reported significant associations and both indicated the opposite association. Specifically, less mycobacterial growth in WBMGA (potentially implying less TB susceptibility) was found in people with LTBI, despite their proven increased future risk of TB disease, possibly because mycobacterial replication in the host may provoke an immune response inhibiting mycobacterial growth in WBMGA (7). It has been suggested that this provides information about an individual’s position on the spectrum of LTBI, following the increasing recognition that LTBI represents a diverse group ranging from those who may have completely cleared the infection to those with actively replicating M. tuberculosis without clinical symptoms (46). If WBMGA results coincide with this spectrum, they may help to inform risk stratification of progression to active TB (7). The results of the included study by O’Shea do appear to imply this, but it is not specified whether patients with active TB were already receiving treatment, which may influence in vitro mycobacterial growth (7). These findings may all be explained by the hypothesis that latent TB infection or TB disease both cause immune activation that reduces TB susceptibility (as indicated by reduced mycobacterial growth in WBMGA), reducing the risk that a new exposure to TB will cause super-infection, re-infection or subsequent TB disease. This integrating hypothesis is supported by some epidemiological data and animal experimentation and should be the focus of future research (45, 47).

Helminth infections have geographical overlap with LTBI and TB disease. Some helminths including hookworm infection suppress the antimycobacterial immune responses measured by TST and IGRA, and this suppression is reversible with anthelminthic treatment (48, 49). This could be a direct effect of helminths that are known to cause some forms of immunosuppression and anergy (50), or might be caused indirectly by helminth infections causing malnutrition, which also suppresses some measures of antimycobacterial immunity (34). Thus, helminth infections may suppress antimycobacterial immunity sufficiently to increase TB susceptibility (50), causing helminth infections to be associated with more mycobacterial growth in WBMGA. However, there is contrary evidence that helminth infections may instead stimulate antimycobacterial immunity (33) and the one study on helminths and WBMGA demonstrated that hookworm infection (but not other helminth species) was associated with less mycobacterial growth in WBMGA, which was reversible with hookworm treatment. There was some evidence for mediation by hookworm-induced eosinophilia (31). These seemingly contradictory findings may be explained by the complexity of antimycobacterial immunity: the antimycobacterial immunity measured by TST and IGRA may be distinct from the mediators assessed in the WBMGA.

A strength of this study that it is the first assessment of whether diverse studies suggest that WBMGA results predict TB risk. Limitations included the absence of direct evidence, so the included studies could not provide a direct answer to our research question. Another limitation was diversity: the profound variations in study design, methodology, statistical analysis, population and sample size in the studies that our systematic review identified confounded their comparison and synthesis by meta-analysis, and also complicated the assessment of study quality. Particularly concerning was the lack of controls in approximately half of the included studies. Variation in reported statistical methodology and failure of most of the included studies to publish their source data prevented us from calculating confidence intervals in our assessments of WBMGA results and forced us to calculate weighted average effect rather than using optimal meta-analysis techniques, limiting the precision of our meta-analyses.

After the literature search of this systematic review was finished, a study from The Gambia was published that would have met our inclusion criteria if it been published earlier and is noteworthy for two main methodological reasons (51). Firstly, this study used a novel auto-luminescent WBMGA, which allows for collecting smaller volume blood samples and serial measurement of luminescence without sample destruction. Secondly, WBMGA were used to assess pairs of highly TB-exposed children with discordant TST status, a novel study design that allows for comparison of individuals with a presumably similar level of TB exposure (51). This contrasts with the studies included in our review in which TB exposure could be a potential confounding factor. However, apart from these two novel methodological advances, the findings of this study were similar to the studies included in our review, demonstrating greater mycobacterial growth in uninfected children than in infected children. Thus, this recently published study does not alter the conclusions of our systematic review.

In conclusion, WBMGA results usually showed statistically significant associations with factors known or likely to affect TB susceptibility. However, these studies were diverse and there is a need for methodological standardization as well as a systematic assessment of reproducibility of WBMGA results, as has been done for PBMC-based assays (52). Importantly, prospective evaluations of whether WBMGA predict peoples’ risk of TB infection or disease are urgently needed, although these studies are likely to be slow and expensive because of the relatively low incidence of either outcome, the long interval over which these outcomes develop, and diagnostic difficulties that make the absence of TB infection or disease difficult to prove. Prospective studies should assess whether an optimized and standardized WBMGA may be useful for TB risk stratification or evaluation of new TB vaccine candidates.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in the study are included in the article, the links in the Methods section of the article, or the publications cited in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

JB, RH, and CE contributed to the conception of the study. JB and CE searched the data. JB and CE extracted the data. JB analyzed the data. JB, RH, and CE interpreted the data. JB, RH and CE prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Funding is gratefully acknowledged from: the Wellcome Trust (awards 057434/Z/99/Z, 070005/Z/02/Z, 078340/Z/05/Z, 105788/Z/14/Z, and 201251/Z/16/Z); UK-AID DFID-CSCF; the Joint Global Health Trials Scheme (award MR/K007467/1) with funding from the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, the UK Medical Research Council, the UK Department of Health and Social Care through the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) and Wellcome; the STOP TB partnership’s TB REACH initiative funded by the Government of Canada and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (awards W5_PER_CDT1_PRISMA and OPP1118545); CONCYTEC/ FONDECYT award code E067-2020-02-01 number 083-2020; and the charity IFHAD: Innovation For Health And Development.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Larry Moulton of Johns Hopkins University and Dr Emily MacLean of McGill University and the following members of our IFHAD research team: Dr Sumona Datta, Dr Matthew Saunders, Dr James Wilson, Dr Linda Chanamé Pinedo, and Lic Luz Quevedo who do not meet the requirement rules for co-authorship but have made helpful comments and suggestions concerning this research project and manuscript.

References

1. Global Tuberculosis Report 2020. World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2020 (Accessed Feb. 24, 2021).

2. Narasimhan P, Wood J, Macintyre CR, Mathai D. Risk factors for tuberculosis. Pulm Med (2013) 2013:828939. doi: 10.1155/2013/828939

3. Walzl G, Ronacher K, Hanekom W, Scriba TJ, Zumla A. Immunological biomarkers of tuberculosis. Nat Rev Immunol (2011) 11:343–54. doi: 10.1038/nri2960

4. Saunders MJ, Wingfield T, Tovar MA, Baldwin MR, Datta S, Zevallos K, et al. A score to predict and stratify risk of tuberculosis in adult contacts of tuberculosis index cases: a prospective derivation and external validation cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis (2017) 17:1190–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30447-4

5. Saunders MJ, Tovar MA, Collier D, Baldwin MR, Montoya R, Valencia TR, et al. Active and passive case-finding in tuberculosis-affected households in Peru: a 10-year prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis (2019) 19:519–28. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30753-9

6. Tanner R, O’Shea MK, Fletcher HA, McShane H. In vitro mycobacterial growth inhibition assays: A tool for the assessment of protective immunity and evaluation of tuberculosis vaccine efficacy. Vaccine (2016) 34:4656–65. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.07.058

7. O’Shea MK, Tanner R, Müller J, Harris SA, Wright D, Stockdale L, et al. Immunological correlates of mycobacterial growth inhibition describe a spectrum of tuberculosis infection. Sci Rep (2018a) 8:14480. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32755-x

8. Eisen S, Pealing L, Aldridge RW, Siedner MJ, Necochea A, Leybell I, et al. Effects of Ascent to High Altitude on Human Antimycobacterial Immunity. PLoS One (2013) 8:e74220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074220

9. Martineau AR, Newton SM, Wilkinson KA, Kampmann B, Hall BM, Nawroly N, et al. Neutrophil-mediated innate immune resistance to mycobacteria. J Clin Invest (2007a) 117:1988–94. doi: 10.1172/JCI31097

10. Tanner R, O'Shea MK, White AD, Müller J, Harrington-Kandt R, Matsumiya M, et al. The influence of haemoglobin and iron on in vitro mycobacterial growth inhibition assays. Sci Rep (2017) 7. doi: 10.1038/srep43478

11. Kampmann B, Gaora PÓ, Snewin VA, Gares M, Young DB, Levin M. Evaluation of Human Antimycobacterial Immunity Using Recombinant Reporter Mycobacteria. J Infect Dis (2000) 182:895–901. doi: 10.1086/315766

12. Wallis RS, Palaci M, Vinhas S, Hise AG, Ribeiro FC, Landen K, et al. A Whole Blood Bactericidal Assay for Tuberculosis. J Infect Dis (2001) 183:1300–3. doi: 10.1086/319679

13. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group TP. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med (2009) 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

14. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. (2014). Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (Accessed Feb. 24, 2021)

15. Harrell FE. Hmisc: A package of miscellaneous R functions (2014). Available at: https://hbiostat.org/R/Hmisc/ (Accessed Jul. 1, 2020).

16. Cheon S-H, Kampmann B, Hise AG, Phillips M, Song H-Y, Landen K, et al. Surrogate Marker of Immunity after Vaccination against Tuberculosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol (2002) 9:901–7. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.4.901-907.2002

17. Hoft DF, Worku S, Kampmann B, Whalen CC, Ellner JJ, Hirsch CS, et al. Investigation of the Relationships between Immune-Mediated Inhibition of Mycobacterial Growth and Other Potential Surrogate Markers of Protective Mycobacterium tuberculosis Immunity. J Infect Dis (2002) 186:1448–57. doi: 10.1086/344359

18. Kampmann B, Tena GN, Mzazi S, Eley B, Young DB, Levin M. Novel Human In Vitro System for Evaluating Antimycobacterial Vaccines. Infect Immun (2004) 72:6401–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6401-6407.2004

19. Fletcher HA, Worku S, Kampmann B, Whalen CC, Ellner JJ, Hirsch CS, et al. Inhibition of Mycobacterial Growth In Vitro following Primary but Not Secondary Vaccination with Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Clin Vaccine Immunol (2013) 20:1683–9. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00427-13

20. Martineau AR, Wilkinson RJ, Wilkinson KA, Newton SM, Kampmann B, Hall BM, et al. A single dose of vitamin D enhances immunity to mycobacteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2007b) 176:208–13. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-007OC

21. Kampmann B, Tena-Coki GN, Nicol MP, Levin M, Eley B. Reconstitution of antimycobacterial immune responses in HIV-infected children receiving HAART. AIDS (2006) 20:1011–8. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000222073.45372.ce

22. Tena GN, Young DB, Eley B, Henderson H, Nicol MP, Levin M, et al. Failure to control growth of mycobacteria in blood from children infected with human immunodeficiency virus and its relationship to T cell function. J Infect Dis (2003) 187:1544–51. doi: 10.1086/374799

23. Roy A, Eisenhut M, Harris RJ, Rodrigues LC, Sridhar S, Habermann S, et al. Effect of BCG vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (2014) 349. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4643

24. Nnoaham KE, Clarke A. Low serum vitamin D levels and tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol (2008) 37:113–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym247

25. Vargas MH, Furuya MEY, Pérez-Guzmán C. Effect of altitude on the frequency of pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis (2004) 4:1321–4.

26. Saito M, Wilkinson RJ, Wilkinson KA, Newton SM, Kampmann B, Hall BM, et al. Comparison of altitude effect on Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection between rural and urban communities in Peru. Am J Trop Med Hygiene (2006) 75:49–54. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2006.75.49

27. Corbett EL, Watt CJ, Walker N, Maher D, Williams BG, Raviglione MC, et al. The growing burden of tuberculosis: global trends and interactions with the HIV epidemic. Arch Intern Med (2003) 163:1009–21. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.9.1009

28. Baguma R, Wilkinson RJ, Wilkinson KA, Newton SM, Kampmann B, Hall BM, et al. Application of a whole blood mycobacterial growth inhibition assay to study immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a high tuberculosis burden population. PLoS One (2017) 12:e0184563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184563

29. Wallis RS, Vinhas S, Janulionis E. Strain specificity of antimycobacterial immunity in whole blood culture after cure of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (2009) 89:221–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2009.02.001

30. Nicol MP, Kampmann B, Lawrence P, Wood K, Pienaar S, Pienaar D, et al. Enhanced Anti-Mycobacterial Immunity in Children with Erythema Nodosum and a Positive Tuberculin Skin Test. J Invest Dermatol (2007) 127:2152–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700845

31. O’Shea MK, Fletcher TE, Muller J, Tanner R, Matsumiya M, Bailey JW, et al. Human Hookworm Infection Enhances Mycobacterial Growth Inhibition and Associates With Reduced Risk of Tuberculosis Infection. Front Immunol (2018b) 9:2893. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02893

32. du Plessis N, Walzl G. “Helminth-M. Tb Co-Infection”. In: Horsnell W, editor. How Helminths Alter Immunity to Infection. New York, NY: Springer New York (2014). p. 49–74.

33. Borelli V, Vita F, Shankar S, Soranzo MR, Banfi E, Scialino G, et al. Human Eosinophil Peroxidase Induces Surface Alteration, Killing, and Lysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun (2003) 71:605–13. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.605-613.2003

34. Cegielski JP, McMurray DN. The relationship between malnutrition and tuberculosis: evidence from studies in humans and experimental animals. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis (2004) 14:286–98.

35. Elias D, Mengistu G, Akuffo H, Britton S. Are intestinal helminths risk factors for developing active tuberculosis? Trop Med Int Health (2006) 11:551–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01578.x

36. Zak DE, Penn-Nicholson A, Scriba TJ, Thompson E, Suliman S, Amon LM, et al. A blood RNA signature for tuberculosis disease risk: a prospective cohort study. Lancet (2016) 387:2312–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01316-1

37. Weiner J, Maertzdorf J, Sutherland JS, Duffy FJ, Thompson E, Suliman S, et al. Metabolite changes in blood predict the onset of tuberculosis. Nat Commun (2018) 9:5208. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07635-7

38. Mandalakas AM, Kirchner HL, Lombard C, Walzl G, Grewal HMS, Gie RP, et al. Well-quantified tuberculosis exposure is a reliable surrogate measure of tuberculosis infection. The International journal of tuberculosis and lung disease (2012) 16(8):1033–39. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0027

39. Rono J, Färnert A, Olsson D, Osier F, Rooth I, Persson KEM. Plasmodium falciparum line-dependent association of in vitro growth-inhibitory activity and risk of malaria. Infect Immun (2012) 80:1900–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06190-11

40. Fine PEM. Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet (1995) 346:1339–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92348-9

41. Joosten SA, van Meijgaarden KE, Arend SM, Prins C, Oftung F, Korsvold GE, et al. Mycobacterial growth inhibition is associated with trained innate immunity. J Clin Invest (2018) 128:1837–51. doi: 10.1172/JCI97508

42. Esmail H, Barry CE, Young DB, Wilkinson RJ. The ongoing challenge of latent tuberculosis. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci (2014) 369:20130437. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0437

43. Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Nienhaus A. Predictive value of interferon-γ release assays and tuberculin skin testing for progression from latent TB infection to disease state: a meta-analysis. Chest (2012) 142:63–75. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-3157

44. Rangaka MX, Wilkinson KA, Glynn JR, Ling D, Menzies D, Mwansa-Kambafwile J, et al. Predictive value of interferon-γ release assays for incident active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis (2012) 12:45–55. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70210-9

45. Andrews JR, Noubary F, Walensky RP, Cerda R, Losina E, Horsburgh CR. Risk of Progression to Active Tuberculosis Following Reinfection With Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis (2012) 54:784–91. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir951

46. Barry CE 3rd, Boshoff HI, Dartois V, Dick T, Ehrt S, Flynn J, et al. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol (2009) 7:845–55. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2236

47. Cadena AM, Hopkins FF, Maiello P, Carey AF, Wong EA, Martin CJ, et al. Concurrent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis confers robust protection against secondary infection in macaques. PLoS Pathog (2018) 14:e1007305. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007305

48. Elias D, Wolday D, Akuffo H, Petros B, Bronner U, Britton S. Effect of deworming on human T cell responses to mycobacterial antigens in helminth-exposed individuals before and after bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination. Clin Exp Immunol (2001) 123:219–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01446.x

49. Banfield S, Pascoe E, Thambiran A, Siafarikas A, Burgner D. Factors Associated with the Performance of a Blood-Based Interferon-γ Release Assay in Diagnosing Tuberculosis. PLoS One (2012) 7(6):e38556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038556

50. Babu S, Nutman TB. Helminth-Tuberculosis Co-Infection: an Immunologic Perspective. Trends Immunol (2016) 37:597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.07.005

51. Basu Roy R, Sambou B, Sissoko M, Holder B, Gomez MP, Egere U, et al. Protection against mycobacterial infection: A case-control study of mycobacterial immune responses in pairs of Gambian children with discordant infection status despite matched TB exposure. EBioMedicine (2020) 59:102891. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102891

52. Tanner R, Smith SG, van Meijgaarden KE, Giannoni F, Wilkie M, Gabriele L, et al. Optimisation, harmonisation and standardisation of the direct mycobacterial growth inhibition assay using cryopreserved human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Immunol Methods (2019) 469:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2019.01.006

Keywords: tuberculosis, mycobacterial growth assay, mycobacterial growth inhibition assay, MGIA, susceptibility, risk

Citation: Bok J, Hofland RW and Evans CA (2021) Whole Blood Mycobacterial Growth Assays for Assessing Human Tuberculosis Susceptibility: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 12:641082. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.641082

Received: 13 December 2020; Accepted: 08 March 2021;

Published: 11 May 2021.

Edited by:

Buka Samten, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler, United StatesReviewed by:

Giovanni Delogu, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyArshad Khan, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, United States

Copyright © 2021 Bok, Hofland and Evans. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carlton A. Evans, Q2FybHRvbi5FdmFuc0BJRkhBRC5vcmc=

Jeroen Bok1,2,3,4

Jeroen Bok1,2,3,4 Carlton A. Evans

Carlton A. Evans