94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol., 01 March 2021

Sec. T Cell Biology

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.623280

This article is part of the Research TopicThymic Epithelial Cells: New Insights in the Essential Driving Force of T Cell DifferentiationView all 16 articles

Huishan Tao1†

Huishan Tao1† Lei Li1†

Lei Li1† Nan-Shih Liao2

Nan-Shih Liao2 Kimberly S. Schluns3‡

Kimberly S. Schluns3‡ Shirley Luckhart4

Shirley Luckhart4 John W. Sleasman1

John W. Sleasman1 Xiao-Ping Zhong1,5,6*

Xiao-Ping Zhong1,5,6*Expression of tissue-restricted antigens (TRAs) in thymic epithelial cells (TECs) ensures negative selection of highly self-reactive T cells to establish central tolerance. Whether some of these TRAs could exert their canonical biological functions to shape thymic environment to regulate T cell development is unclear. Analyses of publicly available databases have revealed expression of transcripts at various levels of many cytokines and cytokine receptors such as IL-15, IL-15Rα, IL-13, and IL-23a in both human and mouse TECs. Ablation of either IL-15 or IL-15Rα in TECs selectively impairs type 1 innate like T cell, such as iNKT1 and γδT1 cell, development in the thymus, indicating that TECs not only serve as an important source of IL-15 but also trans-present IL-15 to ensure type 1 innate like T cell development. Because type 1 innate like T cells are proinflammatory, our data suggest the possibility that TEC may intrinsically control thymic inflammatory innate like T cells to influence thymic environment.

How innate like T cell such as iNKT cell and γδT cell development is regulated and the role of thymic epithelial cells (TECs) in their development is not fully understood. We analyzed publicly available databases and have found that transcripts of many cytokines and cytokine receptors are expressed in both human and mouse TECs. We demonstrated that TEC-derived IL-15 and IL-15Rα play important and selective roles for type 1 innate like T cell, such as iNKT1 and γδT1 cell, development in the thymus. As iNKT1 cells are proinflammatory and contribute to adipogenesis, our data suggest the possibility that TEC may intrinsically control thymic inflammatory innate like T cells to influence thymic environment.

Two lineages of T cells, the αβT cell and γδT cell lineages that express distinct TCR receptor αβ chains and γδ chains, are generated in the thymus. αβT cells develop sequentially from the CD4−CD8− double negative (DN) stage, the CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP) stage, and to the TCRαβ+CD4+CD8− or TCRαβ+CD4−CD8+ single positive (SP) stage. Several αβT cells sublineages, including conventional CD4+ and CD8+ αβT cells, regulatory T cells, invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells, and mucosal associate invariant T (MAIT) cells, with both distinct and common phenotypic and functional properties are evolved within the thymus (1–4). DN thymocytes can be sequentially defined into early T cell progenitors (ETP, Lin−cKit+CD44+CD25−), CD44+CD25+ DN2, CD44−CD25+ DN3, and CD44−CD25− DN4 stages. At the DN2 and DN3 stages, γδT cells are generated after productively expressing functional γδ TCRs (5). In contrast to conventional αβT cells, iNKT cells, MAIT cells, and γδT cells can complete their differentiation into effector cells in the thymus, which appears to be regulated by thymic environment (6–11). These effector lineages include the type 1 sublineage (iNKT1/MAIT1/γδT1) that express T-bet and IFNγ, the type 2 sublineage (iNKT2/MAIT2/γδT2) that express Gata3 and IL-4, and the type 3 sublineage (iNKT17/MAIT17/γδT17) that express RORγt and IL-17A (8, 9, 12–19). While naïve T cells require several days to differentiate to effector cells, these innate like T cells can be activated quickly and are able to rapidly produce a variety of cytokines in response to agonistic stimuli to shape both innate and adaptive immunity.

In addition to crucial roles of TCR signals for both αβT and γδT cell development, local environment plays important roles in these innate like T cell maturation and differentiation to effector lineages. IL-15 is critical for development of iNKT cells, especially, for the NK1.1+CD44+ stage 3 and IFNγ-producing T-bet+ iNKT1 cells (20–23). Similarly, γδT cell effector lineages are also controlled by local cytokines. IFNγ-producing γδT1 cells are severely decreased in pLNs in IL-15 or IL-15Rα deficient mice. IL-15 induces γδT1 cell proliferation and survival via upregulating Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 (24, 25). An important feature of IL-15 signaling is that IL-15Rα serves as a high affinity IL-15-binding protein to trans-present IL-15 to the IL-15Rβ/γc complex on neighboring cells (26–30). IL-15Rα mediated trans-presentation of IL-15 promotes NK cells and CD8 T cell homeostasis (26–30). Interestingly, IL-15Rα deficiency causes severe impairment of stage 3 iNKT1 cell development (6, 7). Although it has been reported that radiation-resistant cells in the thymus provide IL-15 and trans-present IL-15 via IL-15Rα to promote iNKT cell development (6, 7), the exact cellular source of IL-15 and the cell type(s) that trans-present IL-15 via IL-15Rα have been unclear as the thymus contains many cell types including radiation resistant non-hematopoietic cells and some hematopoietic cells that could also be radiation resistant.

Thymic epithelial cells (TECs) are crucial for thymopoiesis and thymus function to generate a vast repertoire of T cells that are able to perform immune defenses but are also self-tolerated. Cortical TECs (cTECs) and medullary TECs (mTECs) localize in discrete regions in the thymus and perform different function (31–33). cTECs are mainly responsible for positive selection of developing thymocytes expressing functional TCRs capable of recognition of self-peptide/MHC complexes (34–37). mTECs ensure highly self-reactive T cells are ablated to establish central tolerance via presentation of promiscuously expressed tissue restricted antigens (TRAs) controlled by Aire and Fezf2 (34, 36, 38–41). In this report, we analyzed publicly available databases and revealed that TECs indeed express a variety of cytokine and cytokine receptors at various levels. We demonstrated further that ablation of either IL-15 or IL-15Rα in TECs selectively impaired development and/or homeostasis of iNKT1 and γδT1 cells in the thymus, indicating that TECs not only serve as an important source of IL-15 but also trans-present IL-15 to ensure type 1 innate like T cell development. Our data suggest that possibility that TEC may intrinsically control thymic inflammatory innate like T cells, which may in turn influence thymic environment.

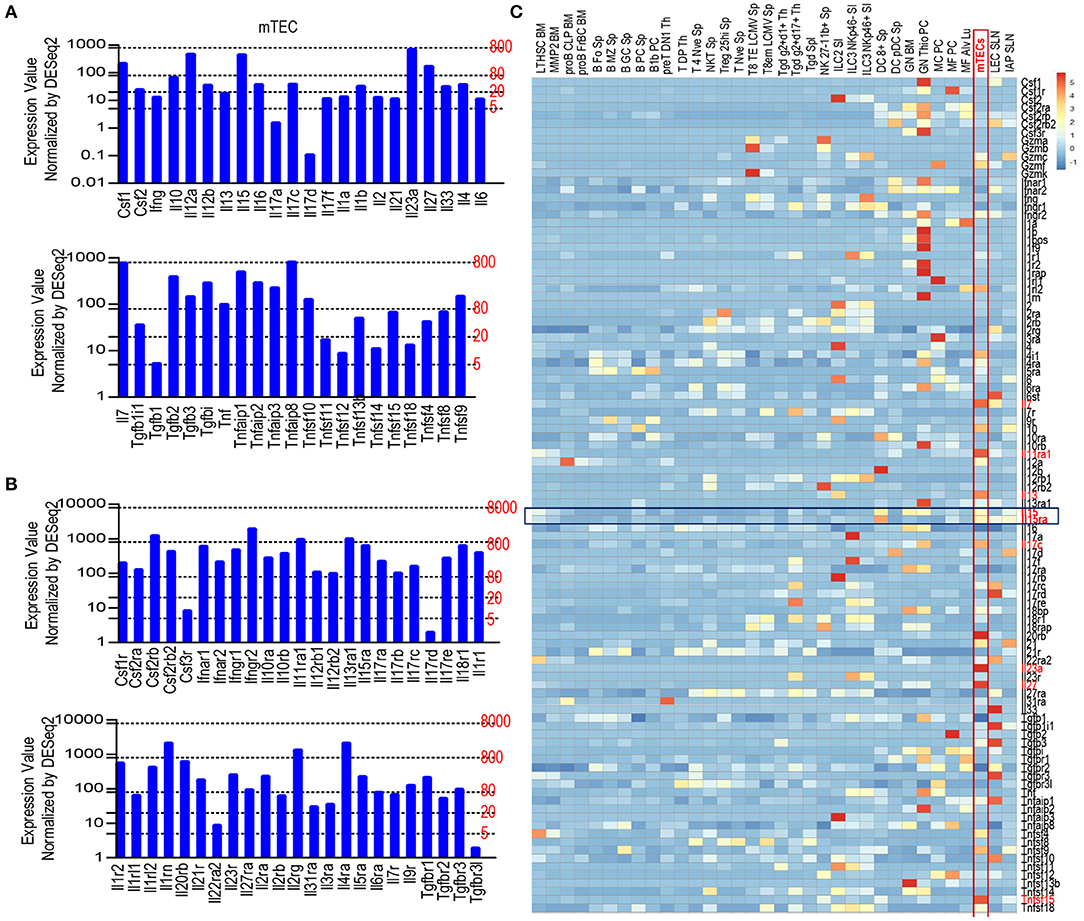

To determine the expression of cytokines and cytokine receptors in mTECs, we searched the publicly available Skyline RNAseq database from The Immunological Genome Project (Immgen.org) for mRNA levels in mTEC. mRNAs of many cytokines and their receptors could be detected in mTECs at various levels (Figures 1A,B). For cytokines, Il7 is expressed at high levels and Il23a is expressed close to high levels (Figure 1A); Csf1, IL12a, Il15, Il27, Tgfb2, Tgfb3, Tnf, Tnfsf9, and Tnfsf10 are expressed at intermediate levels; Many other cytokines such as Il10, Il12b, il17c, Il1b, Il4, Il33, and several Tnf superfamily members are expressed at low levels; several other cytokines such as Ifng, Il17a, Il17d and Tgfb1were expressed at very low or trace levels. For cytokine receptors, Csf2rb, Ifngr2, Il11ra1, Il13ra1, Il1rn, Il2rg, and Il4ra are expressed at high levels, whereas most cytokine receptors including Il15ra are expressed at intermediate levels and a few of cytokine receptors such as Il22ra2, Csf3r, and Il17rd were expressed between low and trace levels. Compared with different types of immune cells and other stromal cells, mTECs were among the highest expressers of mRNAs for multiple cytokines and cytokine receptors such as Il7, Il10, Il11ra1, Il13, Il15, Il15ra, Il17c, Il20rb, Il23a, Il27, Tnfsf4, Tnfsf9, and Tnfsf15 (Figure 1C). Thus, mTECs express mRNAs of many cytokines and cytokine receptors at various levels.

Figure 1. Expression of various cytokines and cytokine receptors in mTECs. (A) mRNA levels of cytokines in mTECs. Expression levels: 0–5, Trace; 2–20, very low; 20–80, low; 80–800, intermediate; 800–8,000, high according to Immgen.org. (B) mRNA levels of cytokine receptors in mTECs. (C) Heatmap showing relative mRNA levels of cytokine and cytokine receptor among mTECs, immune cells, and other stromal cells. Data shown are compiled from the RNAseq data from Immgen.org.

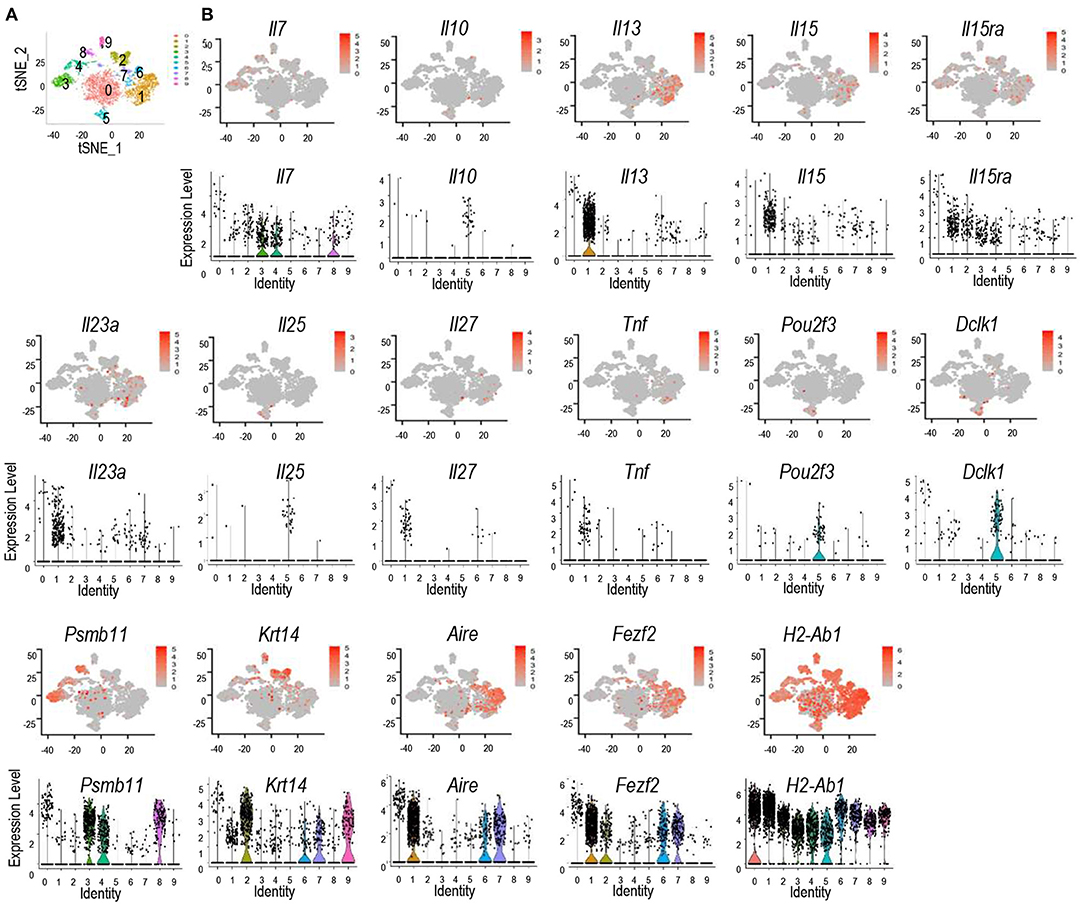

Recently, murine TECs have been defined into 5 subsets based on single cell RNA sequencing analysis (42–48). To further investigate expression of cytokines and their receptors in TEC subsets, we analyzed scRNAseq data of TECs generated by the Ido Amit group, which had sequenced more TECs than other reports (42). Using the Seurat package approach (49), we could define TECs from 4 to 6 week old mice into 10 populations (Figure 2A). Populations 3, 4, and 8 are Psmb11+ and represent cTECs; populations 2 and 9 are Krt14+ and represent mTEC-I; populations 1, 6, and 7 are Aire+ and Fezf2+ and represent mTEC-II; population 5 is enriched with Il25, Pou2f3, and Dclk1 and represents mTEC-IV or Tuft cells; population 0 is the most abundant population that expresses the highest levels of multiple molecules such as H2-ab1, Psmb11, Krt14, Aire, Fezf2, and Dclk1 as well as cytokines and cytokine receptors, although at low frequencies. This population may represent mTEC-III (Figure 2B). Interestingly, Aire+/Fezf2+ populations 1, 6, and 7 (mTEC-II) also contain high levels and/or frequencies of cytokines/cytokine receptor mRNAs such as Il13, Il23a, Il27, and Tnf. In addition to Il25, mTEC-IV also is the highest Il10 expresser. Although cTECs (populations 3, 4, and 8) contain highest frequencies of Il7+ cells, populations 1, 2, and 9 (mTEC-I/III) contain cells expressing higher levels of Il7 than cTECs. Il15 is expressed at high frequencies in population 1 and its levels appear higher in mTEC populations than cTEC populations, which is consistent with the detection of IL-15 reporter expression in the medulla in the mouse thymus (50). Il15ra is expressed at higher frequencies in populations 1 and 2 of mTECs and populations 3 and 4 of cTECs. However, the expression levels in these mTECs appear higher than in cTECs. Overall, Aire/Fezf2+ mTECs appear to express multiple cytokines at levels higher than cTECs while cTECs express higher levels of Il7 than mTECs.

Figure 2. Discrete and promiscuous expression of cytokines and cytokine receptors in murine TEC subsets. scRNAseq data of TECs from 4 to 6 weeks old mice were analyzed. (A) tSNE plots showing TEC populations. (B) tSNE plots (top panels) and violin plots (bottom panels) showing distribution of cytokine/cytokine receptor expressing cells in different TEC populations. Data shown are generated from the scRNAseq data from Bornstein et al. (42).

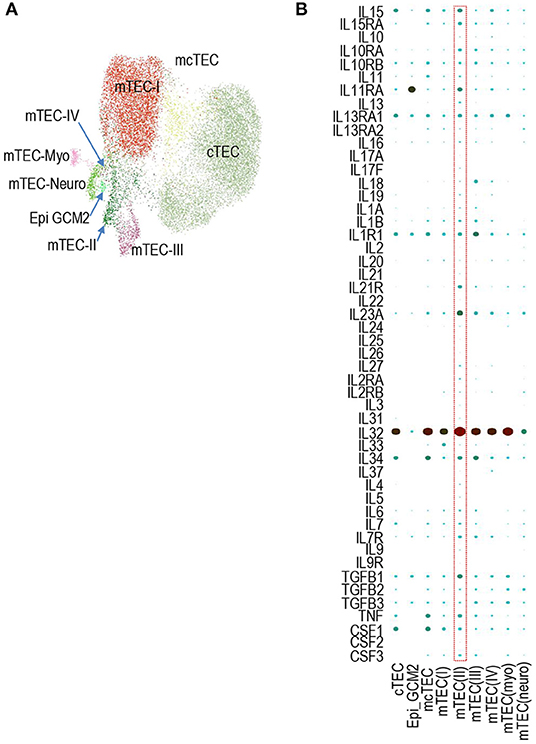

Similar to murine TECs, a recent report has found human TECs could also be defined into multiple populations based scRNAseq transcriptomic analysis (51). Human TECs also contain TEC-I – IV populations that mimic their murine counterparts. In addition, human TECs also contain MYOD1- and MYOG-expression myoid TEC-myo and NEUROD1- and NEURODG1- expressing TEC-neuro populations (Figure 3A) (51). We searched the Human Fetal Thymic Epithelium Gene Expression Web Portal (https://developmentcellatlas.ncl.ac.uk/datasets/HCA_thymus/human_epi/) for cytokines and cytokine receptors and revealed that human TECs also express many cytokine mRNAs at various levels (Figure 3B). IL15, IL15RA, IL11RA, IL13RA1, IL1R1, IL23A, IL32, IL34, TGF1B1, TNF, and CSF1 are noticeably expressed at intermediate or high levels. Thus, similar to murine TECs, human TECs also expressed various cytokine/cytokine receptors at the mRNA levels.

Figure 3. Expression of cytokines and cytokine receptors in human TEC subsets. (A) UMAP presentation of human fetal TEC clusters adapted from Jong-Eun Park et al. (51). (B) Dot-plot showing mRNA levels of indicated cytokine/cytokine receptors in the nine human TEC clusters from scRNAseq analysis. The size and color of the dot represent the percentage of cells within a cluster expressing the mRNA and the average expression level across all cells within a cluster. Light green and dark red represent low and high levels, respectively.

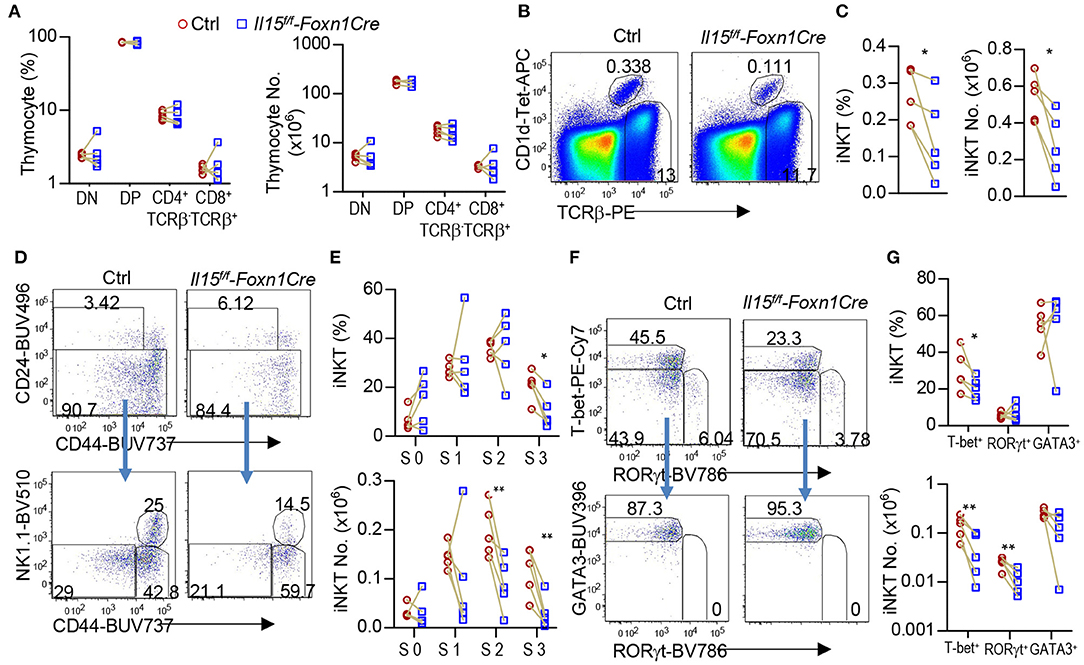

Thymic iNKT cells are defined into 0–3 stages based on differential expression of CD24, CD44, and NK1.1. IL-15/IL-15R signal promoted the development of T-bet+ iNKT1 cells, which occupy most of the CD44+NK1.1+ stage 3 iNKT cells (6, 7, 20–23). To investigate whether IL-15 expressed on TECs may exert biologic consequence besides serving as a TRA, we generated and analyzed TEC-specific IL-15 deficient, Il15f/f-Foxn1Cre mice. Foxn1Cre mice direct Cre expression starting on embryonic day 11.5 in TECs and ablate gene in both mTECs and cTECs (52). Compared with WT control mice, Il15f/f-Foxn1Cre mice did not show obvious alterations in thymocyte development (Figure 4A). However, their thymic iNKT cells, which were CD1d-Tetramer loaded with PBS-57 positive (CD1d-Tet+) and TCRβ+, showed 42.8 and 50.4% decreases of both percentages and numbers, respectively (Figures 4B,C). Within iNKT cells, CD24+CD44− stage 0 and CD24−CD44− stage 1 iNKT cells were not altered; CD24−CD44+NK1.1− stage 2 iNKT cell percentages were not changed but numbers were decreased 54.8%; CD24−CD44+NK1.1+ stage 3 iNKT cells were decreased in both percentages (51.1%) and more severely in numbers (74.4%) (Figures 4D,E). Moreover, T-bet+RORγt− iNKT1 cells were decreased in both percentages (31.8%) and, more severely, in numbers (66.2%). In contrast, T-bet−RORγt+ iNKT17 cell percentages were not decreased, although numbers of these cells were moderately decreased (54.9%). In contrast, T-bet−RORγt−Gata3+ iNKT2 cells were not altered in either percentages or numbers (Figures 4F,G). Thus, TEC-derived IL-15 is important for iNKT1 but not iNKT2 differentiation and/or homeostasis. Additionally, TEC-derived IL-15 also exerts a weak role for iNKT17 cell differentiation/homeostasis.

Figure 4. Impairment of iNKT1 development/homeostasis in TEC-specific IL-15 deficient mice. Thymocytes from 2 to 3 weeks old Il15f/f-Foxn1Cre and WT (Il15+/+-Foxn1Cre or Il15f/f) control mice were stained with fluorescently labeled PBS-57-loaded CD1d-Tetramer (CD1d-Tet), antibodies for TCRβ, CD4, CD8, other indicated molecules, and lineage markers (CD11b, B220, Ter119, CD11c, F4/80) as well as a fixable Live/Dead stain. (A) Scatter graph represents percentages and numbers of CD4−CD8− double negative (DN), CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP), and TCRβ+ CD4+CD8− or CD4−CD8+ single positive (SP) mature T cells. (B) Representative FACS plots showing TCRβ and CD1d-Tet staining of live gated Lin− thymocytes. (C) Scatter plots of iNKT cell percentages and numbers. (D) Representative FACS plots showing CD24 vs. CD44 staining of total iNKT cells and CD44 vs. NK1.1 staining of CD24− iNKT cells. (E) Scatter graphs of percentages and numbers of stage 0–3 iNKT cells. (F) Representative FACS plots showing T-bet vs. RORγt staining of CD24− iNKT cells and GATA3 vs. RORγt staining of CD24− T-bet−RORγt− iNKT cells. (G) Scatter graphs of percentages and numbers of iNKT1/2/17 cells. Data shown are representative of or pooled from five experiments. Connection lines indicate sex-matched littermates. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 determined by two-tail pairwise Student t-test.

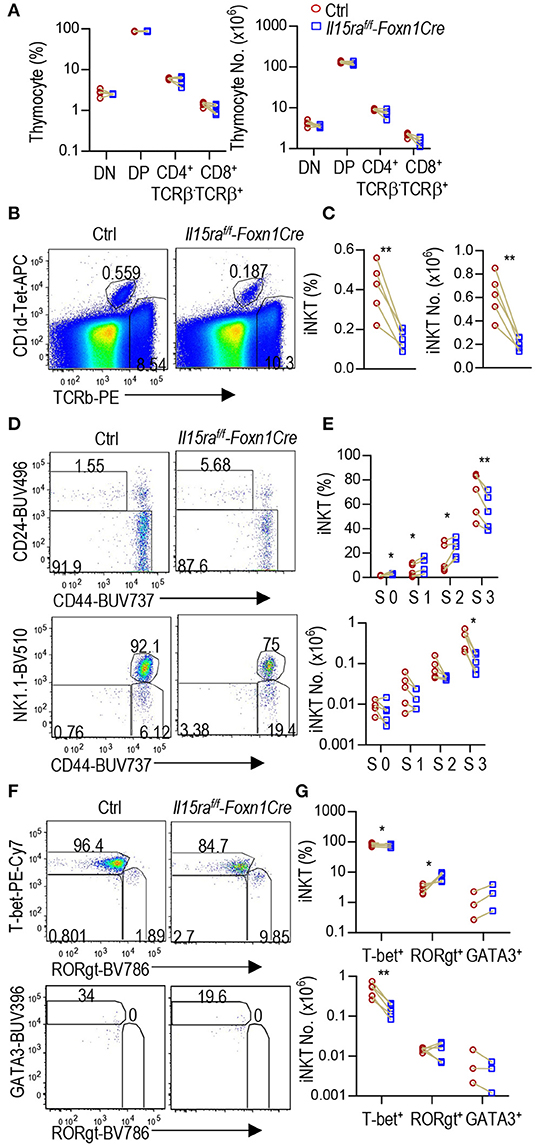

IL-15Rα can trans-present IL-15 to IL-15R to trigger IL-15R signaling (26, 27). It has been reported that radiation-resistant thymic stromal cells may trans-present IL-15 to promote stage 3 and iNKT1 cell development via enhancing Bcl-2 mediated survival. The data were generated in lethally irradiated IL15Rα−/− mice reconstituted with WT bone marrow cells (6, 7). However, these studies did not distinguish the role of TECs, other stromal cells, and radiation-resistant tissue resident macrophages or lymphoid tissue inducer cells. To investigate whether IL-15Rα expressed on TECs has biological consequences, we analyzed TEC-specific IL-15Rα deficient, Il15raf/f-Foxn1Cre mice. Thymocyte development was not grossly affected in Il15raf/f-Foxn1Cre mice (Figure 5A). However, Il15raf/f-Foxn1Cre mice displayed 62.7 and 66.4% decreases of thymic iNKT cell percentages and numbers, respectively (Figures 5B,C). Within iNKT cells, percentages of stage 0, 1, and 2 cells were increased 2.1, 1.5, and 1.5-fold, respectively. However, their numbers were not significantly changed (Figures 5D,E). Stage 3 iNKT cells were decreased in both percentages (19.5%) and numbers (72.8%). Furthermore, T-bet+RORγt− iNKT1 cells but not T-bet−RORγt+ iNKT17 or T-bet−RORγt−GATA3+ iNKT2 cells were severely decreased in Il15raf/f-Foxn1Cre thymus (Figures 5F,G). Thus, IL-15Rα on TECs played an important and selective role for iNKT1 but not for iNKT2/17 differentiation or early iNKT cell development.

Figure 5. Selective defects in iNKT1 but not iNKT2/17 cell differentiation in Il15raf/f-Foxn1Cre mice. Thymocytes from 6 to 8 weeks old Il15raf/f-Foxn1Cre and WT (Il15ra+/+-Foxn1Cre or Il15raf/f) control mice were analyzed similarly as Figure 4. (A) Scatter graph represents percentages and numbers of DN, DP, and TCRβ+ CD4+CD8− or CD4−CD8+ SP mature T cells. (B) Representative FACS plots showing TCRβ and CD1d-Tet staining of live gated Lin− thymocytes. (C) Scatter plots of iNKT cell percentages and numbers. (D) Representative FACS plots showing CD24 vs. CD44 staining of total iNKT cells and CD44 vs. NK1.1 staining of CD24− iNKT cells. (E) Scatter graphs of percentages and numbers of stage 0–3 iNKT cells. (F) Representative FACS plots showing T-bet vs. RORγt staining of CD24− iNKT cells and GATA3 vs. RORγt staining of CD24− T-bet−RORγt− iNKT cells. The gating of GATA3+ iNKT cells is based on its levels in T-bet+ iNKT cells. (G) Scatter graphs of percentages and numbers of iNKT1/2/17 cells. Data shown are representative of or pooled from three to five experiments. Connection lines indicate sex-matched littermates. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 determined by two-tail pairwise Student t-test.

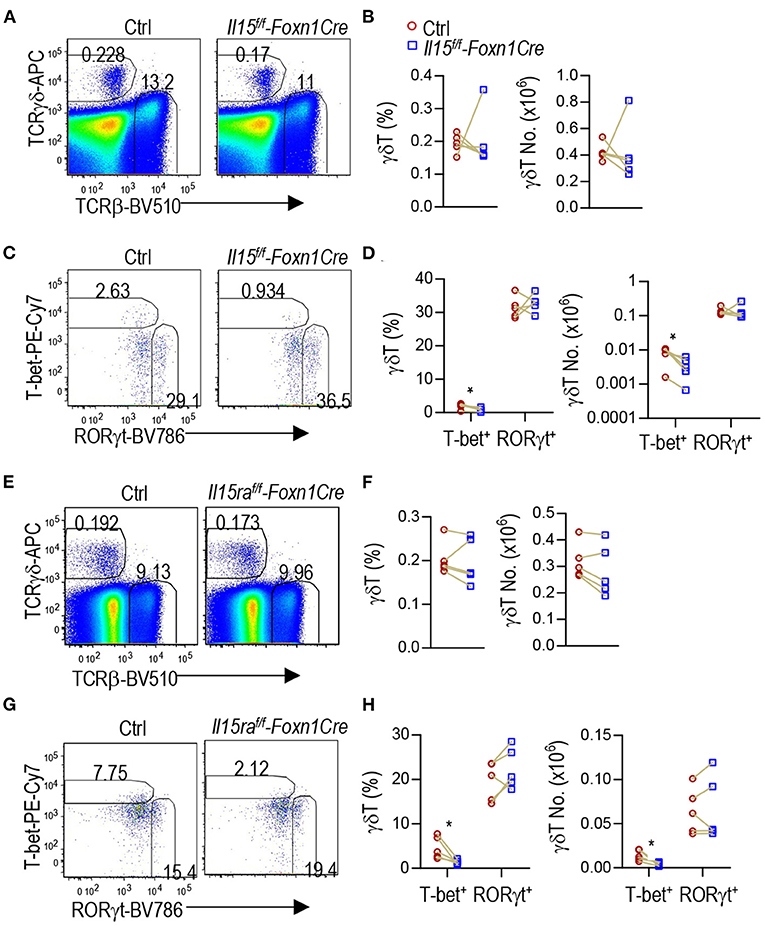

γδT cells are another innate like T cell lineage that differentiate to effector lineages in the thymus. γδT cells also contain T-bet+ IFNγ-producing γδT1 and RORγt+ IL-17A-producing γδT17 lineages (53–55). γδT1 cells express CD122, the IL-2/15Rβ chain, and IL-15R signal is also important for γδT1 cell differentiation as well as γδT cell homeostasis and migration (20, 56–61). In Il15f/f-Foxn1Cre thymus, γδT cell percentages and numbers were not obviously different from controls (Figures 6A,B). However, T-bet+RORγt− γδT1 cells but not T-bet−RORγt+ γδT17 cells were decreased 54.8% in percentages and 57.7% numbers (Figures 6C,D), indicating that TEC-derived IL-15 plays an important role for γδT1 cell development/homeostasis in the thymus.

Figure 6. Selective defects in γδT1 but not γδT17 cell differentiation in TEC-specific IL-15 or IL-15Rα deficient mice. (A–D) Thymocytes from 2 to 3 weeks old Il15f/f-Foxn1Cre and WT (Il15+/+-Foxn1Cre or Il15f/f) control mice were labeled with fluorescently tagged antibodies as well as a fixable Live/Dead stain. (A) Representative FACS plots showing TCRβ and TCRγδ staining of live gated thymocytes. (B) Scatter graphs showing γδT cell percentages and numbers. (C) Representative FACS plots showing T-bet vs. RORγt in γδT cells. (D) Scatter graphs showing percentages and numbers of γδT1/17 lineages. Data shown are representative of or pooled from five experiments. Connection lines indicate sex-matched littermates. *p < 0.05 determined by two-tail pairwise Student t-test. (E–H) Thymocytes from 6 to 8 weeks old Il15raf/f-Foxn1Cre and WT (Il15ra+/+-Foxn1Cre or Il15raf/f) control mice were labeled with fluorescently tagged antibodies as well as a fixable Live/Dead stain. (E) Representative FACS plots showing TCRβ and TCRγδ staining of live gated thymocytes. (F) Scatter graphs showing γδT cell percentages and numbers. (G) Representative FACS plots showing T-bet vs. RORγt in γδT cells. T-bet+ γdT cell gating is based on its levels in TCRβ+CD44−CD122− cells (Supplementary Figure 1B). (H) Scatter graphs showing percentages and numbers of γδT1/17 lineages. Data shown are representative of or pooled from five experiments. Connection lines indicate sex-matched littermates. *p < 0.05 determined by two-tail pairwise Student t-test.

Similarly, IL-15Rα deficiency in TECs in Il15raf/f-Foxn1Cre mice did not obviously affect total γδT cell percentages or numbers (Figures 6E,F). However, γδT1 but not γδT17 cells in the thymus were decreased 69.1% in percentages and 70.4% numbers (Figures 6G,H). Thus, IL-15Rα on TECs also selectively promoted γδT1 cell differentiation but appeared dispensable for γδT17 differentiation.

It has been long appreciated that TECs control local environment to shape both conventional and innate like T cell development. We analyzed publicly available RNAseq and scRNAseq data and found that TECs, especially mTECs, express mRNAs for numerous cytokines and cytokine receptors such as Il13, Il23a, Il15, and Il27 as well as Il15ra in mouse and/or human. Some cytokines and cytokine receptors including IL-15 and IL-15Rα are single chain molecules. It is conceivable that these molecules could be expressed as biologically functional molecules in TECs if they are properly processed inside these cells. While multiple previous studies have found radio-resistant cell derived IL-15 and/or IL-15Rα or have suggested that mTEC-derived IL-15 and/or IL-15Rα are important for iNKT cell, especially iNKT1 cell, development, no TEC-specific ablation of these molecules have been reported (6, 7, 62). We examined how TEC-specific IL-15 or IL-15Rα deficiency affects T cell, especially innate like T cell, development. We found that ablation of either IL-15 or IL-15Rα in TECs causes significant impairment of iNKT1 and γδT1 cell development in the thymus. Our data reveal that TECs not only serve as an indispensable source of IL-15 but also trans-present IL-15 for proper type 1 innate T cell development. At present, we do not known whether expression of various cytokine and cytokine receptors in TECs is dependent on Aire or Fezf2 and whether they function in TECs as TRAs to ensure T cell central tolerance. Nevertheless, our observations, together with those that mTEC-IV-derived IL-25 promotes iNKT2 development in the thymus (42, 43), suggest the possibility that some cytokines and cytokine receptors expressed in TECs may function both as TRAs and biologically active molecules that can exert their canonical biological functions in the thymus to shape local thymic environment to regulate T cell, particularly innate like T cell, development. Further studies are needed to examine whether TEC-specific ablation of IL-15 and IL-15Rα leads to escape the negative selection of T cells reactive to these molecules.

Of note, TEC-deficiency of IL-15 or IL-15Rα does not completely abolish type 1 innate like T cell development. It is possible other cell types such as dendritic cells and macrophages in the thymus may play partially redundant roles with TECs. Interestingly, TEC-specific IL-15 deficiency weakly reduced iNKT17 numbers in the thymus. This observation is consistent with previous reports that injection of IL-15/IL-15Rα complex induced expansion of both thymic iNKT1 and iNKT17 cells in mice (62, 63). Thus, TEC-derived IL-15 also plays an important role for iNKT17 cell development. Of note, our study does not distinguish the role of mTEC and cTEC derived IL-15/IL-15Rα for iNKT1 and γdT1 development as Foxn1Cre ablates genes in both mTECs and cTECs. However, IL-15 appears to be expressed mainly in mTECs and IL-15Rα is expressed at higher levels in mTECs than cTECs (Figure 2). Additionally, it has been found that mTECs are critical for iNKT1 cell development and induction of IL15R signaling by injecting IL-15/IL-15Rα complex into micer is able to overcome mTEC deficiency to promote iNKT1 development (62, 63). Similarly, γdT cells differentiate into effector lineages in the medulla (64). Together, these observations support that mTECs provide critical source of IL-15 for iNKT1 and γδT1 cell development.

Although mRNAs encoding many cytokines and cytokine receptors are expressed in TECs, some of them are biologically active only after complex with other molecules. For example, IL-12 and IL-23 that are heterodimers of an IL-12B (IL-12p40) subunit and the IL-12A (IL-12p35) subunit or the IL-23A (IL-23p19) subunit, respectively. Simultaneous expression of both subunits in the same cells would be required for formation of a functional protein. It is intriguing that expression levels among cytokines and cytokine receptors varies drastically in TECs. Il23a is expressed at the highest levels in mTECs. Whether such high levels of expression ensure full deletion of IL-23A reactive T cells, increase the chance of coexpression with IL-12B in some TECs, or IL-23A itself has biological activity in TECs remain to be explored.

The ability of TECs to produce cytokines and trans-presentation of cytokine(s) to shape thymic environment to control innate like T cell effector lineage differentiation/homeostasis in the thymus could have important implications for thymus biology. Despite the importance of the thymus for T cell generation, it undergoes involution or atrophy with advancing age. Thymic involution may contribute to the decline of immune functions, increased infection-induced mortality and morbidity, and autoimmune diseases in the elderly population (65–67). Although many extrinsic factors that can modulate the course of thymic involution have been identified, none is able to prevent or stop thymic involution. It has been noted that age-associated thymic involution is associated with accumulation of fatty tissue and inhibition of adipogenesis delays thymic involution. Interestingly, adipogenesis is promoted by local inflammation that is negatively controlled by iNKT2 and M2 macrophages but positively controlled by IFNγ and M1 macrophages (68–70). Given the ability of TEC sublineages to control type 1 and type 2 innate like T cell differentiation and iNKT cells can in turn regulate mTECs and thymic dendritic cells (63, 71), it is possible that thymic involution is an intrinsically programmed process encarved in and triggered by TECs (particularly mTECs) via shaping local thymic environment and presence of innate like T cell effector lineages in the thymus. A hypothesis warrants further investigation.

Il15raf/f mice (28) and Il15f/f mice (72) were kindly provided by Drs. Kimberly Schluns and Averil Ma and Drs. Nan-Shih Liao and Shirley Luckhart, were bred with B6(Cg)-Foxn1tm3(cre)Nrm/J (Foxn1Cre) mice (52) that were kindly provided by Dr. Nancy Manley, to generate Il15raf/f−Foxn1Cre and Il15f/f−Foxn1Cre mice as well as Il15raf/f, Il15f/f, and WT-Foxn1Cre control mice. Mice were maintained in a pathogen free facility. All mouse experiments were performed following a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Duke University.

Thymocytes cells were prepared according to published protocols (73, 74). Cells were stained for surface markers with appropriate fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies and tetramers in PBS containing 2% FBS on ice for 30 min followed by intracellular staining of transcription factors using the eBioscience Foxp3 Staining Buffer Set according to the manufacturer's protocols. PE- or APC-labeled PBS-57-loaded CD1d-Tetramers (CD1d-Tet) were provided by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility. Fluorochrome-conjugated anti-TCRβ (clone H57-597), NK1.1 (clone PK136), CD44 (clone IM7), CD24 (clone M1/69), CD11b (clone M170), CD11c (clone N418), F4/80 (clone BM8), B220 (clone RA3-6B2), TER119/Erythroid Cells (clone TER-119), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8a (53-6.7), T-bet (4B10), TCRγδ (clone GL3), CD3 (clone 145-2C11), CD45 (clone 30-F11), CD27 (clone LG.3A10) were purchased from Biolegend; GATA3 (L50-823), RORγt (Q31-378) were purchased from BD Biosciences. Cell death was identified using the Live/Dead™ Fixable Violet Dead Cell Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were collected using a BD LSRFortessa™ cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using the FlowJo Version 9.2 software (Tree Star).

Skyline RNAseq database from the Immunological Genome Project (Immgen.org) was searched for mRNA levels of indicated cytokines and cytokine receptors. In the Immunological Genome Project, 34 immune cell types from male and female mice were profiled by RNA-seq. Expression of mRNA was normalized for each cell types with the Z-score method. To visualize the different values among different cell types, the data for each cell were plotted as a heatmap using the pheatmap program (75).

Raw counts of scRNAseq data of TECs from 4 to 6 weeks old mice reported by Bornstein et al. (42) were downloaded from GEO Database under the accession number GSE103967. scRNAseq data were pre-processed using the Seurat package (version 3.1.1) (49) in R (version 3.5.3). Genes expressed in fewer than 3 cells and cells with no more than 50 detected genes were filtered out. Filtered datasets were normalized the gene expression measurements for each cell by the total expression multiplied with a scale factor of 10,000 by default, followed by log-transformation of the results using the global-scaling normalization method, LogNormalize. The technical noise and/or biological sources of variation were mitigated via ScaleData function to improve downstream dimensionality reduction and clustering. Highly variable genes were screened with Find Variable Features function for downstream analysis. Principle component analysis (PCA) were performed on the scaled data using the RunPCA function. Significant PCs were identified as those with a strong enrichment of low p-value genes based on the Jackstraw algorithm. For cell clustering, k-nearest neighbors were calculated and the SNN graphs were constructed using Find Neighbors. Top 20 PCs were selected for analysis using Find Clusters. Cells within the graph-based clusters determined above were co-localized for visualization on the tSNE plot via RunTSNE and TSNEPlot. Find All Markers were applied to find markers that define clusters via differential expression. Feature Plot was applied to visualize individual gene expression on a tSNE plot. VlnPlot was applied to show expression probability distributions across clusters.

Expression of cytokines and cytokine receptors in human TECs was searched online based on scRNAseq analyses (https://developmentcellatlas.ncl.ac.uk/datasets/HCA_thymus/human_epi/) (51). Data were presented as a bubble plot with bubble size representing percentages of TECs expressing individual molecules and bubble color representing expression levels.

Data shown represent means ± SEMs and were analyzed with the two-tailed pairwise Student t-test using the Prism 5/GraphPad software for statistical differences. Each pair of mice represents sex-matched littermates and is indicated by a connecting line between test and control mice. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Duke University.

HT and LL designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and participated manuscript preparation. N-SL, KS, and SL provided critical reagents and participated in manuscript preparation. X-PZ conceived the project, designed experiments, and wrote the manuscript. JS participated in manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R56AG060984 and R56AI079088 for X-PZ and R01AI131609 for SL) and by the Translating Duke Health Initiative.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Drs. Averil Ma (UCSF) and Nancy Manley (University of Georgia) for providing the Il15raf/f and Foxn1Cre mice respectively, the NIH Tetramer Core Facility for CD1d-Tetramers, and the flow cytometry core facility at Duke University for services. We are also grateful to the Immunological Genome Project, the Ido Amit group, and the Human Cell Atlas Developmental portal for open data access and analyses.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.623280/full#supplementary-material

1. Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. (2008) 133:775–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009

2. Yang W, Gorentla B, Zhong XP, Shin J. mTOR and its tight regulation for iNKT cell development and effector function. Mol Immunol. (2015) 68:536–45. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.07.022

3. Pan Y, Deng W, Xie J, Zhang S, Wan ECK, Li L, et al. Graded diacylglycerol kinases alpha and zeta activities ensure mucosal-associated invariant T-cell development in mice. Eur J Immunol. (2020) 50:192–204. doi: 10.1002/eji.201948289

4. Chandra S, Kronenberg M. Activation and function of iNKT and MAIT cells. Adv Immunol. (2015) 127:145–201. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.03.003

5. Hayday AC. Gammadelta T cell update: adaptate orchestrators of immune surveillance. J Immunol. (2019) 203:311–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800934

6. Chang CL, Lai YG, Hou MS, Huang PL, Liao NS. IL-15Ralpha of radiation-resistant cells is necessary and sufficient for thymic invariant NKT cell survival and functional maturation. J Immunol. (2011) 187:1235–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100270

7. Castillo EF, Acero LF, Stonier SW, Zhou D, Schluns KS. Thymic and peripheral microenvironments differentially mediate development and maturation of iNKT cells by IL-15 transpresentation. Blood. (2010) 116:2494–503. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-277103

8. Koay HF, Gherardin NA, Enders A, Loh L, Mackay LK, Almeida CF, et al. A three-stage intrathymic development pathway for the mucosal-associated invariant T cell lineage. Nat Immunol. (2016) 17:1300–11. doi: 10.1038/ni.3565

9. Legoux F, Gilet J, Procopio E, Echasserieau K, Bernardeau K, Lantz O. Molecular mechanisms of lineage decisions in metabolite-specific T cells. Nat Immunol. (2019) 20:1244–55. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0465-3

10. Wang HX, Cheng JS, Chu S, Qiu YR, Zhong XP. mTORC2 in thymic epithelial cells controls thymopoiesis and T cell development. J Immunol. (2016) 197:141–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502698

11. Wang HX, Shin J, Wang S, Gorentla B, Lin X, Gao J, et al. mTORC1 in Thymic Epithelial Cells Is Critical for Thymopoiesis, T-Cell Generation, and Temporal Control of gammadeltaT17 Development and TCRgamma/delta Recombination. PLoS Biol. (2016) 14:e1002370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002370

12. Michel ML, Mendes-da-Cruz D, Keller AC, Lochner M, Schneider E, Dy M, et al. Critical role of ROR-gammat in a new thymic pathway leading to IL-17-producing invariant NKT cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2008) 105:19845–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806472105

13. Watarai H, Sekine-Kondo E, Shigeura T, Motomura Y, Yasuda T, Satoh R, et al. Development and function of invariant natural killer T cells producing T(h)2- and T(h)17-cytokines. PLoS Biol. (2012) 10:e1001255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001255

14. Matsuda JL, Zhang Q, Ndonye R, Richardson SK, Howell AR, Gapin L. T-bet concomitantly controls migration, survival, and effector functions during the development of Valpha14i NKT cells. Blood. (2006) 107:2797–805. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3103

15. Coquet JM, Chakravarti S, Kyparissoudis K, McNab FW, Pitt LA, McKenzie BS, et al. Diverse cytokine production by NKT cell subsets and identification of an IL-17-producing CD4-NK1.1- NKT cell population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2008) 105:11287–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801631105

16. Wu J, Yang J, Yang K, Wang H, Gorentla B, Shin J, et al. iNKT cells require TSC1 for terminal maturation and effector lineage fate decisions. J Clin Invest. (2014) 124:1685–98. doi: 10.1172/JCI69780

17. Chen Y, Ci X, Gorentla B, Sullivan SA, Stone JC, Zhang W, et al. Differential requirement of RasGRP1 for gammadelta T cell development and activation. J Immunol. (2012) 189:61–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103272

18. Shibata K, Yamada H, Sato T, Dejima T, Nakamura M, Ikawa T, et al. Notch-Hes1 pathway is required for the development of IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells. Blood. (2011) 118:586–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-334995

19. Ribot JC, deBarros A, Pang DJ, Neves JF, Peperzak V, Roberts SJ, et al. CD27 is a thymic determinant of the balance between interferon-γ- and interleukin 17–producing γδ T cell subsets. Nat Immunol. (2009) 10:427–36. doi: 10.1038/ni.1717

20. Kennedy MK, Glaccum M, Brown SN, Butz EA, Viney JL, Embers M, et al. Reversible defects in natural killer and memory CD8 T cell lineages in interleukin 15-deficient mice. J Exp Med. (2000) 191:771–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.771

21. Matsuda JL, Gapin L, Sidobre S, Kieper WC, Tan JT, Ceredig R, et al. Homeostasis of V alpha 14i NKT cells. Nat Immunol. (2002) 3:966–74. doi: 10.1038/ni837

22. Ranson T, Vosshenrich CA, Corcuff E, Richard O, Muller W, Di Santo PJ. IL-15 is an essential mediator of peripheral NK-cell homeostasis. Blood. (2003) 101:4887–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3392

23. Ranson T, Vosshenrich CA, Corcuff E, Richard O, Laloux V, Lehuen A, et al. IL-15 availability conditions homeostasis of peripheral natural killer T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2003) 100:2663–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0535482100

24. Corpuz TM, Stolp J, Kim HO, Pinget GV, Gray DH, Cho JH, et al. Differential responsiveness of innate-like IL-17- and IFN-gamma-producing gammadelta T cells to homeostatic cytokines. J Immunol. (2016) 196:645–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502082

25. Colpitts SL, Puddington L, Lefrancois L. IL-15 receptor alpha signaling constrains the development of IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2015) 112:9692–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420741112

26. Lodolce JP, Burkett PR, Boone DL, Chien M, Ma A. T cell-independent interleukin 15Ralpha signals are required for bystander proliferation. J Exp Med. (2001) 194:1187–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.8.1187

27. Dubois S, Mariner J, Waldmann TA, Tagaya Y. IL-15Ralpha recycles and presents IL-15 In trans to neighboring cells. Immunity. (2002) 17:537–47. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00429-6

28. Mortier E, Advincula R, Kim L, Chmura S, Barrera J, Reizis B, et al. Macrophage- and dendritic-cell-derived interleukin-15 receptor alpha supports homeostasis of distinct CD8+ T cell subsets. Immunity. (2009) 31:811–22. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.017

29. Mortier E, Woo T, Advincula R, Gozalo S, Ma A. IL-15Ralpha chaperones IL-15 to stable dendritic cell membrane complexes that activate NK cells via trans presentation. J Exp Med. (2008) 205:1213–25. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071913

30. Burkett PR, Koka R, Chien M, Chai S, Boone DL, Ma A. Coordinate expression and trans presentation of interleukin (IL)-15Ralpha and IL-15 supports natural killer cell and memory CD8+ T cell homeostasis. J Exp Med. (2004) 200:825–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041389

31. Wendland K, Niss K, Kotarsky K, Wu NYH, White AJ, Jendholm J, et al. Retinoic acid signaling in thymic epithelial cells regulates thymopoiesis. J Immunol. (2018) 201:524–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800418

32. Wang W, Thomas R, Sizova O, Su DM. Thymic function associated with cancer development, relapse, and antitumor immunity - a mini-review. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:773. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00773

33. Wang HX, Pan W, Zheng L, Zhong XP, Tan L, Liang Z, et al. Thymic epithelial cells contribute to thymopoiesis and T cell development. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:3099. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03099

34. Klein L, Kyewski B, Allen PM, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: what thymocytes see (and don't see). Nat Rev Immunol. (2014) 14:377–91. doi: 10.1038/nri3667

35. Cowan JE, Parnell SM, Nakamura K, Caamano JH, Lane PJ, Jenkinson EJ, et al. The thymic medulla is required for Foxp3+ regulatory but not conventional CD4+ thymocyte development. J Exp Med. (2013) 210:675–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122070

36. Perry JS, Lio CW, Kau AL, Nutsch K, Yang Z, Gordon JI, et al. Distinct contributions of Aire and antigen-presenting-cell subsets to the generation of self-tolerance in the thymus. Immunity. (2014) 41:414–26. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.007

37. Coquet JM, Ribot JC, Babala N, Middendorp S, van der Horst G, Xiao Y, et al. Epithelial and dendritic cells in the thymic medulla promote CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell development via the CD27-CD70 pathway. J Exp Med. (2013) 210:715–28. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112061

38. Anderson MS, Venanzi ES, Klein L, Chen Z, Berzins SP, Turley SJ, et al. Projection of an immunological self shadow within the thymus by the aire protein. Science. (2002) 298:1395–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1075958

39. Takaba H, Morishita Y, Tomofuji Y, Danks L, Nitta T, Komatsu N, et al. Fezf2 orchestrates a thymic program of self-antigen expression for immune tolerance. Cell. (2015) 163:975–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.013

40. Cosway EJ, Lucas B, James KD, Parnell SM, Carvalho-Gaspar M, White AJ, et al. Redefining thymus medulla specialization for central tolerance. J Exp Med. (2017) 214:3183–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171000

41. Derbinski J, Schulte A, Kyewski B, Klein L. Promiscuous gene expression in medullary thymic epithelial cells mirrors the peripheral self. Nat Immunol. (2001) 2:1032–9. doi: 10.1038/ni723

42. Bornstein C, Nevo S, Giladi A, Kadouri N, Pouzolles M, Gerbe F, et al. Single-cell mapping of the thymic stroma identifies IL-25-producing tuft epithelial cells. Nature. (2018) 559:622–6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0346-1

43. Miller CN, Proekt I, von Moltke J, Wells KL, Rajpurkar AR, Wang H, et al. Thymic tuft cells promote an IL-4-enriched medulla and shape thymocyte development. Nature. (2018) 559:627–31. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0345-2

44. Brennecke P, Reyes A, Pinto S, Rattay K, Nguyen M, Kuchler R, et al. Single-cell transcriptome analysis reveals coordinated ectopic gene-expression patterns in medullary thymic epithelial cells. Nat Immunol. (2015) 16:933–41. doi: 10.1038/ni.3246

45. Kernfeld EM, Genga RMJ, Neherin K, Magaletta ME, Xu P, Maehr R. A single-cell transcriptomic atlas of thymus organogenesis resolves cell types and developmental maturation. Immunity. (2018) 48:1258–70.e1256. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.015

46. Miragaia RJ, Zhang X, Gomes T, Svensson V, Ilicic T, Henriksson J, et al. Single-cell RNA-sequencing resolves self-antigen expression during mTEC development. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:685. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-19100-4

47. Zeng Y, Liu C, Gong Y, Bai Z, Hou S, He J, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing resolves spatiotemporal development of pre-thymic lymphoid progenitors and thymus organogenesis in human embryos. Immunity. (2019) 51:930–48.e936. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.09.008

48. Bacon WA, Hamilton RS, Yu Z, Kieckbusch J, Hawkes D, Krzak AM, et al. Single-cell analysis identifies thymic maturation delay in growth-restricted neonatal mice. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:2523. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02523

49. Satija R, Farrell JA, Gennert D, Schier AF, Regev A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat Biotechnol. (2015) 33:495–502. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3192

50. Cui G, Hara T, Simmons S, Wagatsuma K, Abe A, Miyachi H, et al. Characterization of the IL-15 niche in primary and secondary lymphoid organs in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2014) 111:1915–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318281111

51. Park JE, Botting RA, Dominguez Conde C, Popescu DM, Lavaert M, Kunz DJ, et al. A cell atlas of human thymic development defines T cell repertoire formation. Science. (2020) 367:eaay3224. doi: 10.1126/science.aay3224

52. Gordon J, Xiao S, Hughes B, Su D-m, Navarre SP, Condie BG, et al. Specific expression of lacZ and cre recombinase in fetal thymic epithelial cells by multiplex gene targeting at the Foxn1 locus. BMC Dev Biol. (2007) 7:69–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-69

53. Parker ME, Ciofani M. Regulation of gammadelta T cell effector diversification in the thymus. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:42. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00042

54. Papotto PH, Reinhardt A, Prinz I, Silva-Santos B. Innately versatile: gammadelta17 T cells in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. (2018) 87:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.11.006

55. Vantourout P, Hayday A. Six-of-the-best: unique contributions of γδ T cells to immunology. Nat Rev Immunol. (2013) 13:88–100. doi: 10.1038/nri3384

56. De Creus A, Van Beneden K, Stevenaert F, Debacker V, Plum J, Leclercq G. Developmental and functional defects of thymic and epidermal V gamma 3 cells in IL-15-deficient and IFN regulatory factor-1-deficient mice. J Immunol. (2002) 168:6486–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6486

57. Hu MD, Ethridge AD, Lipstein R, Kumar S, Wang Y, Jabri B, et al. Epithelial IL-15 is a critical regulator of gammadelta intraepithelial lymphocyte motility within the intestinal mucosa. J Immunol. (2018) 201:747–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701603

58. Ma LJ, Acero LF, Zal T, Schluns KS. Trans-presentation of IL-15 by intestinal epithelial cells drives development of CD8alphaalpha IELs. J Immunol. (2009) 183:1044–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900420

59. Shibata K, Yamada H, Nakamura R, Sun X, Itsumi M, Yoshikai Y. Identification of CD25+ γδ T cells as fetal thymus-derived naturally occurring IL-17 producers. J Immunol. (2008) 181:5940–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5940

60. Pantelyushin S, Haak S, Ingold B, Kulig P, Heppner FL, Navarini AA, et al. Rorgammat+ innate lymphocytes and gammadelta T cells initiate psoriasiform plaque formation in mice. J Clin Invest. (2012) 122:2252–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI61862

61. Lodolce JP, Boone DL, Chai S, Swain RE, Dassopoulos T, Trettin S, et al. IL-15 receptor maintains lymphoid homeostasis by supporting lymphocyte homing and proliferation. Immunity. (1998) 9:669–76. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80664-0

62. White AJ, Jenkinson WE, Cowan JE, Parnell SM, Bacon A, Jones ND, et al. An essential role for medullary thymic epithelial cells during the intrathymic development of invariant NKT cells. J Immunol. (2014) 192:2659–66. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303057

63. Lucas B, White AJ, Cosway EJ, Parnell SM, James KD, Jones ND, et al. Diversity in medullary thymic epithelial cells controls the activity and availability of iNKT cells. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:2198. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16041-x

64. Cowan JE, Jenkinson WE, Anderson G. Thymus medulla fosters generation of natural Treg cells, invariant gammadelta T cells, and invariant NKT cells: what we learn from intrathymic migration. Eur J Immunol. (2015) 45:652–660. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445108

65. Masters AR, Haynes L, Su DM, Palmer DB. Immune senescence: significance of the stromal microenvironment. Clin Exp Immunol. (2016) 187:6–15. doi: 10.1111/cei.12851

66. Dixit VD. Impact of immune-metabolic interactions on age-related thymic demise and T cell senescence. Semin Immunol. (2012) 24:321–30. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.04.002

67. Coder BD, Wang H, Ruan L, Su DM. Thymic involution perturbs negative selection leading to autoreactive T cells that induce chronic inflammation. J Immunol. (2015) 194:5825–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500082

68. Hams E, Locksley RM, McKenzie AN, Fallon PG. Cutting edge: IL-25 elicits innate lymphoid type 2 and type II NKT cells that regulate obesity in mice. J Immunol. (2013) 191:5349–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301176

69. Lynch L, Nowak M, Varghese B, Clark J, Hogan AE, Toxavidis V, et al. Adipose tissue invariant NKT cells protect against diet-induced obesity and metabolic disorder through regulatory cytokine production. Immunity. (2012) 37:574–87. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.016

70. Lynch L, Michelet X, Zhang S, Brennan PJ, Moseman A, Lester C, et al. Regulatory iNKT cells lack expression of the transcription factor PLZF and control the homeostasis of T(reg) cells and macrophages in adipose tissue. Nat Immunol. (2015) 16:85–95. doi: 10.1038/ni.3047

71. White AJ, Lucas B, Jenkinson WE, Anderson G. Invariant NKT cells and control of the thymus medulla. J Immunol. (2018) 200:3333–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800120

72. Liou YH, Wang SW, Chang CL, Huang PL, Hou MS, Lai YG, et al. Adipocyte IL-15 regulates local and systemic NK cell development. J Immunol. (2014) 193:1747–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400868

73. Shen S, Wu J, Srivatsan S, Gorentla BK, Shin J, Xu L, et al. Tight regulation of diacylglycerol-mediated signaling is critical for proper invariant NKT cell development. J Immunol. (2011) 187:2122–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100495

74. Shin J, Wang S, Deng W, Wu J, Gao J, Zhong XP. Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 is critical for invariant natural killer T-cell development and effector function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2014) 111:E776–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315435111

Keywords: IL-15, IL-15Rα, thymic epithelial cells, iNKT cells, γδT cells, type 1 innate like T cells

Citation: Tao H, Li L, Liao N-S, Schluns KS, Luckhart S, Sleasman JW and Zhong X-P (2021) Thymic Epithelial Cell-Derived IL-15 and IL-15 Receptor α Chain Foster Local Environment for Type 1 Innate Like T Cell Development. Front. Immunol. 12:623280. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.623280

Received: 29 October 2020; Accepted: 10 February 2021;

Published: 01 March 2021.

Edited by:

Jennifer Elizabeth Cowan, National Institutes of Health (NIH), United StatesReviewed by:

Ondrej Stepanek, Institute of Molecular Genetics (ASCR), CzechiaCopyright © 2021 Tao, Li, Liao, Schluns, Luckhart, Sleasman and Zhong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiao-Ping Zhong, eGlhb3BpbmcuemhvbmdAZHVrZS5lZHU=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

‡Present Address: Kimberly S. Schluns, Kite Pharma Inc, Santa Monica, CA, United States

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.