- Department of Molecular Cell Biology and Immunology, Amsterdam Neuroscience, Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia worldwide giving rise to devastating forms of cognitive decline, which impacts patients’ lives and that of their proxies. Pathologically, AD is characterized by extracellular amyloid deposition, neurofibrillary tangles and chronic neuroinflammation. To date, there is no cure that prevents progression of AD. In this review, we elaborate on how bioactive lipids, including sphingolipids (SL) and specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators (SPM), affect ongoing neuroinflammatory processes during AD and how we may exploit them for the development of new biomarker panels and/or therapies. In particular, we here describe how SPM and SL metabolism, ranging from ω-3/6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites to ceramides and sphingosine-1-phosphate, initiates pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling cascades in the central nervous system (CNS) and what changes occur therein during AD pathology. Finally, we discuss novel therapeutic approaches to resolve chronic neuroinflammation in AD by modulating the SPM and SL pathways.

Introduction

The central nervous system (CNS) is one of the most important but vulnerable parts of the human body. CNS-specific cell types, for example microglia, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes, play a vital role in securing CNS homeostasis and supporting neuronal functioning. In addition, the unique properties of the microvasculature of the CNS that forms the blood brain barrier (BBB), further ensures a tightly controlled CNS environment. The BBB consists of endothelial cells, which are supported by pericytes and astrocytes, together regulating the flow of molecules and cells in and out of the CNS to safeguard its homeostasis (1–5). Over the past decades, worldwide occurrences of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), are increasing and it is expected that this trend will continue (6). Despite years of research and increasing fundamental knowledge, only a few treatments have been developed and used, but none of such interventions results in curing these devastating neurodegenerative diseases, thereby creating a high and unmet clinical need. For this, more fundamental insight into pathological mechanisms that underlie AD pathology is therefore needed to facilitate the development of potential novel treatment regimes.

Key modulators of a variety of physiological (including cellular) processes are lipids. Lipids are highly abundant in the dry mass of the CNS (up to 50%) where they serve important biological functions. Apart from being structural components of a cell membrane, lipids also act as energy storage source and play important roles in cell signaling pathways such as maintaining BBB homeostasis, immune regulation, and myelination (7–9). Since lipid metabolism occurs in such core CNS processes, alterations in lipid metabolism influences the pathophysiology of various neurodegenerative diseases (10). Therefore, targeting lipid metabolism may result in new perspectives for the treatment of such diseases.

Excessive or uncontrolled inflammation is known as a unifying feature of a plethora of chronic diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases like AD (11, 12). It has become clear that lipids and their metabolites can influence the immune responses and inflammatory processes, in promoting as well as in resolving inflammation. In this review we will discuss how bioactive lipids, including sphingolipids (SLs) and specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs), are involved in chronic neuroinflammation in AD and how such bioactive lipids can be used for the development of new therapies.

Alzheimer’s Disease

AD is the predominant cause of dementia with an estimated 54 million cases worldwide, and with an expected growth to 130 million cases by 2050 (13). It is a progressive mental disorder that is characterized by cognitive impairment and memory loss. Next to age, the ϵ4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene (ApoE) is the strongest genetic risk factor for AD (14). Next to peripheral tissues involved in cholesterol metabolism, ApoE is highly expressed in the brain where it plays an important role in lipid trafficking (15). Moreover, it is involved in synaptic plasticity, synaptogenesis, inflammation, blood-brain barrier function and in regeneration after injury (16, 17). However, how ApoE contributes to AD remains to be elucidated.

The major neuropathological hallmarks of AD are the accumulation of extracellular senile plaques composed of aggregating β-amyloid (Aβ) and the intracellular aggregation of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. Aβ is released as monomer into the extracellular environment when β-amyloid precursor protein APP is processed by the amyloidogenic pathway (18, 19). The monomers can aggregate to form oligomers, protofibrils, fibrils and, ultimately, plaques, all of which can have neurotoxic effects causing synaptic dysfunction, reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, increased membrane permeability, and disrupted mitochondrial and proteasomal processes (20–25). Tau is a neuronal microtubule-associated protein that is distributed to the axons to regulate microtubule assembly and stability (26–28). However, when tau is hyperphosphorylated, as seen in AD, it becomes sequestered into neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), which are mainly found in neuronal processes known as neuropil threads or dystrophic neurites. The dissociation of tau proteins from microtubules negatively affects synaptic plasticity, leading to neurodegeneration (29–31).

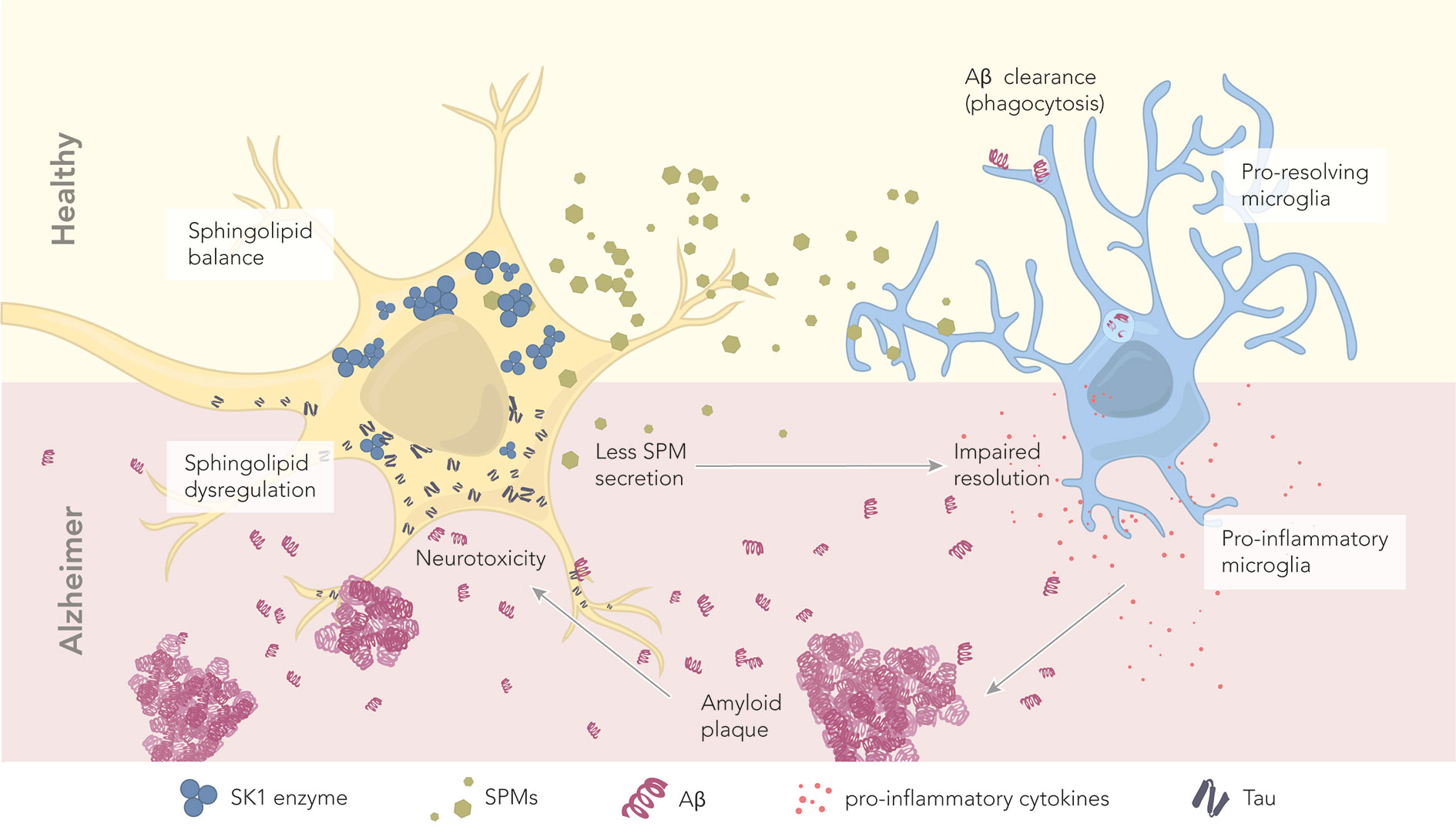

Another neuropathological process in AD is neuro-inflammation. Neuro-inflammation describes the reactive morphology and altered function of the glial compartment (32). Although the observed inflammatory glial response is presumed to be secondary to neuronal death or dysfunction, it is suggested that the activation of microglia and astrocytes contributes to the progression of AD. The main cellular players in neuroinflammatory processes are microglia, the innate immune cells of the CNS. Microglia have a complex function that involves an anti-inflammatory (pro-resolving) role where they engulf toxic proteins and apoptotic cells or a (chronic) pro-inflammatory phenotype, that promotes neurotoxicity through excessive production and secretion of inflammatory mediators. Chronically activated microglia release pro-inflammatory mediators like interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-12, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), ROS, superoxide, and nitric oxide (NO) causing CNS tissue damage (33–36). On the other hand, pro-resolving microglia are involved in the healing phases of CNS injury by actively monitoring and controlling the extracellular environment (37). In addition, by secreting anti-inflammatory mediators like IL-10 and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), these cells are able to prevent neurotoxicity, thereby restoring CNS homeostasis (38). During homeostatic conditions, the pro-inflammatory response of microglia is tightly controlled by pro-resolving microglia to prevent collateral damage to surrounding neurons. However, during neuroinflammatory diseases, such as AD, this resolution of inflammation is dysregulated, resulting in chronic neuro-inflammation and subsequent neurotoxicity.

In AD, pattern recognition receptors on microglia trigger a pro-inflammatory immune response upon Aβ recognition (39). The inflammatory properties of Aβ are strengthened by promoting increased APP levels and elevated cleavage enzyme activity, creating more Aβ production (40). Additionally, microglia surrounding senile plaque become impaired in Aβ uptake and clearance, causing further accumulation of Aβ thereby inducing a prolonged inflammatory response with continuous secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators (41). The local immune response triggers the secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1β that subsequently activate astrocyte-induced proinflammatory responses. In turn, astrocytes amplify the microglia inflammatory responses by producing IL-1β and TNF-α upon activation (42). This, together with Aβ deposition and ROS formation, has considerable detrimental effects on the BBB, such as the loss of tight junctions, pericyte death, and a decrease in the coverage of the parenchymal basal membrane by astrocytic endfeet (43–46). In turn, this greatly abolishes BBB homeostasis and increases innate and adaptive immune cell trafficking toward the CNS, thereby contributing to excessive neuro-inflammation and cognitive impairment in AD (47–50). Creating insights into ways to counteract chronic neuroinflammatory events are of high importance to dampen disease progression.

Sphingolipid Metabolism

The CNS has the second-highest abundancy of lipids to adipose tissue, with 50% of its dry weight comprising of lipids (51). They can be classified into 8 groups containing distinct classes and subclasses of molecules, performing key biological functions (52). Especially SLs gained interest in recent years because of their role as secondary messengers in health and disease. Not only are they ubiquitous components of the plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells and are essential for the development of the CNS, they are also known as bioactive lipids regulating cell survival, cellular stress and cell death (53–55).

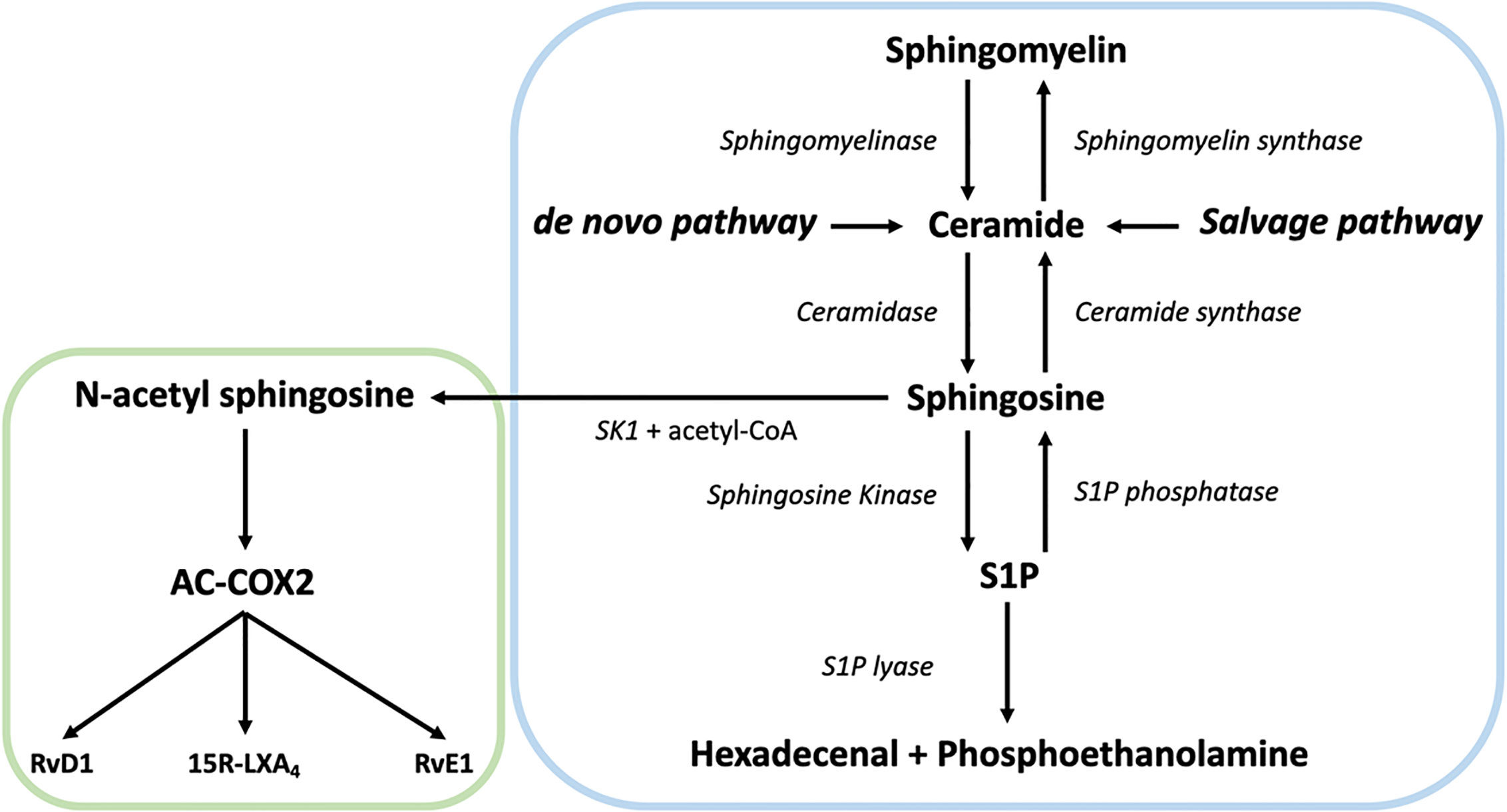

In the centre of SL metabolism are ceramides, that consist of a sphingosine backbone and a fatty acid residue. Ceramides can be synthesized via the de novo pathway, the sphingomyelinase pathway, or the salvage pathway (Figure 1). The de novo synthesis pathway starts with L-serine and palmitoyl-CoA condensation in the endoplasmic reticulum by serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) to 3-ketosphinganine, that is directly reduced to sphinganine by 3-ketosphinganine reductase (3-KSR). Next, ceramide synthases (CerSs) add fatty acyl-CoAs of different chain lengths to sphinganine to form dihydroceramide. Finally, dihydroceramide desaturase converts dihydroceramide to ceramide. After ceramide synthesis, it can be further metabolized to form complex SLs, such as sphingomyelin and glycosphingolipids (56). These complex SLs create a potential ceramide source since they can be converted to ceramide again. For instance, the sphingomyelinase pathway generates ceramides via the hydrolysis of sphingomyelin. This is catalyzed by two sphingomyelinases, named neutral sphingomyelinase (nSMase) and acid sphingomyelinase (aSMase) (57, 58). Finally, ceramide can also be generated from sphingosine via the salvage pathway. While sphingosine can be reused to generate ceramide, it is also the precursor of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) (59). The breakdown of S1P into non-sphingolipid molecules by S1P lyase is the only exit point of sphingolipid metabolism. Over the last decades, it became clear that SLs and their metabolites play an important role in several cellular processes and signaling events, including neuro-inflammation (60–62).

Figure 1 Overview of the sphingolipid (SL) rheostat model and the interplay with specialized pro-resolving mediator (SPM) metabolism. Ceramide can be synthesized by ceramide synthases via the de novo and the salvage pathway from sphingosine or by hydrolysis of sphingomyelin by sphingomyelinase. Once generated, ceramide can act as substrate for other sphingolipids such as sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) via sphingosine kinase (SK). S1P can be catabolized into hexadecenal + phospho-ethanolamine by the action of sphingosine 1-phosphate lyase. Alternatively, SK can generate N-acetyl sphingosine via acetyl-CoA and sphingosine, followed by the acetylation of COX-2. In turn, this activates COX-2 mediated 15-HETE, 18-HEPE and 17-HDHA production, which can be converted to SPMs like such as 15R-LXA4, RvE1, and RvD1, thereby providing a direct link between the SL and SPM pathways.

Sphingolipids and Neuroinflammation

Ceramide and S1P are the main signaling molecules of the SL machinery that can activate a pro- or anti-inflammatory response. Activation of their modulators, such as SMase and sphingosine kinase (SK), are therefore important events during neuroinflammation. Originally it was thought that ceramide functions as a secondary messenger with two faces, where short-chain ceramides (acyl chain length C2-C8) show an anti-inflammatory effect while long-chain ceramides (acyl chain length C16-C24) initiate a pro-inflammatory response (63–66). However, synthetic short-chain ceramides were used to mimic the effects of long-chain ceramides resulting in contradictory results. For instance, the use of short-chain ceramides caused an anti-inflammatory effect in LPS stimulated rodent microglia, by competing with LPS for the binding to toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4). This resulted in the reduction of cytokines, chemokines, inducible NO synthase, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2, also known as prostaglandin G/H synthase 2) and ROS (63, 67, 68). In contrast, astrocytes and microglia produce long-chain ceramides upon TNF-α induced SMase activity. These ceramides activate pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB, inducing expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, NO, TNF-α, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, pro-inflammatory enzyme cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and lipoxygenases (LOXs) (64, 65, 69). These observations are supported by SMase knockdown experiments in rodent LPS-activated microglia, showing impaired NF-κB induced gene expression (66).

However, in the context of ceramide function in the brain, it has become clear that the amount of ceramide is important as well as the relative amount of the individual chain-lengths (70). The various ceramide species are generated by six individual CerSs, of which five are present in the brain. Each CerS prefers certain fatty acyl-CoA substrates, generating distinct ceramide species with unique N-linked fatty acids. The resulting ceramide species differ in their chain-length (C14-C26), localize to distinct cellular compartments, and in turn may mediate specific functions (71, 72). Therefore, contributing opposing functions to short- or long-chain ceramides is to simplified and the underlying regulatory process is far more complicated. This needs to be considered when investigating the role of ceramide in neuro-inflammation.

Besides ceramides, S1P plays an important role in the intracellular and extracellular signaling in the CNS. Various reports suggest that S1P is involved in migration, proliferation and changes in astrocyte and microglia morphology, suggesting its involvement in neuroinflammation (73). Upon activation, two distinct enzymes, SK1 or SK2, phosphorylate sphingosine to form S1P. Although S1P has several intracellular targets, S1P is predominantly transported to the outside the cell, where it acts in a paracrine or autocrine manner on five different S1P receptors (S1PR1-5), which are G protein-coupled receptors (74). S1PR1-3 are ubiquitously expressed while S1PR4 is mainly expressed by leukocytes and S1PR5 by oligodendrocytes and brain endothelial cells (75, 76).

Upon LPS induced activation, SK1 shuttles to the plasma membrane where it converts sphingosine to S1P. Subsequently, S1P binds to S1PRs, which induces proliferation and synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17, and neurotoxic molecules like ROS and NO (77). Additionally, the accumulated extracellular S1P activates microglia and further enhances the inflammatory response (78). Also, S1PR, and SK1 knockdown or the addition of S1PR antagonists reduce pro-inflammatory responses (79, 80). At the level of the BBB, different S1PRs seem to be involved in the remodeling of its integrity. Endothelial cells express three types of S1PRs, S1PR1 activation restricts leukocyte infiltration to the CNS while S1PR2, 3 and 5 regulate vascular permeability by enhancing pro-inflammatory expression. Astrocyte-endothelial cell communication via S1P and/or ceramide may, therefore, be important in maintaining BBB homeostasis as it can promote or decrease its integrity (81–85). This shows that directing specific S1PR activation may influence inflammatory responses in the CNS.

Sphingomyelinase and Ceramide During Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease

In AD, many of the SLs and their metabolites are altered. For example, increased sphingomyelin levels are observed in brain tissue of AD patients, which is associated with the severity of AD pathology (86). However, SMase levels and activity are also increased due to the presence of Aβ and, therefore, could result in increased sphingomyelin hydrolysis (87). Moreover, elevated aSMase significantly correlated with the levels of Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau protein (88). The enhanced SMase levels in AD are possibly involved in pro-inflammatory processes in the brain. The inhibition of nSMase, not aSMase, in Aβ activated human astrocytes suppresses the production of NF-κB and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 (89). Additionally, antisense knockdown of nSMase lowered inducible NOS in vivo and protected neurons in the mouse cortex from fibrillar Aβ toxicity. This indicates that nSMase has a role in the pro-inflammatory activation of astrocytes through a nSMase/ceramide signaling pathway. In addition, exosomes secreted by activated astrocytes induced apoptosis in surrounding astrocytes by transporting long-chain ceramide C18 (90). This toxic effect was attenuated upon nSMase inhibition, suggesting nSMase activation results in a neurotoxic ceramide secretion via exosomes. Furthermore, the increased activity of the sphingomyelin pathway is a large source of ceramide observed in AD (87).

Involvement of the de novo ceramide synthesis pathway is also reported in AD. SPT is the first enzyme in the de novo synthesis of ceramide, and elevated SPT long-chain 1 and SPT long-chain 2 levels are observed in AD (91). Inhibition of SPT directly lowers ceramide synthesis and results in decreased Aβ production, which supports the findings that ceramide metabolism is involved in amyloidopathy (92). For example, ARN14494, which inhibits SPT activity, prevents the synthesis of long-chain ceramides and dihydroceramide in a cortical astrocyte-neuron co-culture. Blockade of SPT activity also prevents the synthesis of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as IL-1β, TNF-α, iNOS, and COX-2 by astrocytes. Additionally, inhibition of SPT possibly prevents caspase-3 neurotoxicity, via the reduced expression of astrocyte secreted pro-inflammatory factors (93). This suggests that ceramide induces pro-inflammatory responses through astrocytes, which may promote neurotoxicity. The exact mechanism by which ceramide activates the pro-inflammatory astrocyte response remains to be established.

Indeed, increased long-chain ceramide levels have been found in AD affected brains, senile plaques, cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) and serum of AD patients (94–98). Interestingly, ceramides enhance APP metabolism toward Aβ by stabilizing β-secretase, creating a vicious cycle. This results in increased ceramide levels in neurons possibly leading to cell death. These observations indicate that interfering in ceramide synthesis possibly reduces Aβ pathology and neuronal cell death in AD (99–101). Taken together, the de novo and the sphingomyelinase ceramide synthesis pathways show to increase the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in AD. Ceramide metabolism might therefore be an interesting therapeutic target to prevent and resolve neuroinflammation during AD.

Sphingosine-1-Phosphate During Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease

The function of S1P in AD affected brains remains controversial. Analysis of post-mortem brain tissue of AD patients showed a reduced level of S1P, which correlated with the levels of hyperphosphorylated tau and Aβ (88). The reduction might be caused by decreased SK1 and increased S1P-lyase activity due to Aβ, which supports the idea that S1P is a pro-survival and proliferative signal (102, 103). On the other hand, however, prolonged exposure of hippocampal neurons to S1P resulted in apoptosis (104). Moreover, depletion of S1P lyase in vivo, causing an increase in S1P levels, augments tau phosphorylation in neurons (105). A study focusing on the development of AD showed elevated S1P levels in mild cognitive impairment patients while eventually in AD patients, S1P levels declined (106). Interestingly, another study investigated whether sphingolipid levels are altered as a function of age and APOE genotype (107). The authors observed an age-dependent decline in S1P levels specifically in females. Moreover, the APOE genotype was not found to have a significant influence on the SL levels. These findings suggest that age is an important factor regarding SL metabolism, where increased S1P levels might play a role in the early development of AD and, as observed in post-mortem AD brains, these levels decrease over time.

Zhong and colleagues proposed a mechanism that displays how S1P is involved in pro-inflammatory activation of microglia in AD (108). They showed that Aβ activates spinster homolog 2 (Spns2), which transports S1P out of the cell, resulting in the subsequent binding of S1P to S1PR1. S1P binding to S1P1R induced the pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion of microglia via a NF-κB dependent mechanism. These experiments were conducted in vitro and in vivo, using primary cultured microglia, mouse models, Spns2 knockout mice as well as an S1PR inhibitor Fingolimod (FTY720). Spns2 knockout mice show reduced inflammatory microglia phenotypes, suggesting that S1P transport is important for the activation of microglia and provides evidence that S1P contributes to Aβ-induced NF-κB signaling and cognitive decline. Another study used LPS activated microglia and astrocytes to study S1PR1 dependent pro-inflammatory chemokine release. Here, the inhibition of S1PR1 via FTY720 attenuates pro-inflammatory chemokine release in both astrocytes and microglia (109). Interestingly, LPS binds to TLR4 to activate pro-inflammatory responses, which suggests that TLR4 may mediate pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokine secretion via S1PR1 activation.

In astrocytes, TLR4 seems to activate SKs resulting in chemokine expression (110). This could also be true for Aβ induced NF-κB secretion via S1PR activation since Aβ binds to TLR4, TLR2 and CD14 for the pro-inflammatory activation of microglia (39, 111, 112). Indeed, in case Aβ would mediate pro-inflammatory responses via other mechanisms, a stronger pro-inflammatory effect could be expected in FTY720 inhibited microglia and astrocytes (108). In conclusion, S1P signaling through S1PR1 seems to play a pivotal role in the pro-inflammatory responses by microglia and astrocytes. The onset of Aβ induced neuroinflammation through TLR/SK/S1P/Spns2/S1PR1/NF-κB signaling possibly takes place in the early stages of AD, as S1P levels are higher in mild cognitive impairment patients before the official onset of AD. However, the exact mechanisms behind the onset of neuro-inflammation in AD by S1P remains to be established.

Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators and the Resolution of Neuroinflammation

Resolution of inflammation is crucial to regain tissue homeostasis. When resolution fails, chronic inflammation occurs, causing excessive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators, potentially leading to ongoing neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, as seen in AD (113). Under healthy conditions, the resolution of inflammation is facilitated by SPMs that are derived from polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). These include ω-3 fatty acids, like α-linolenic (ALA) acid, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) as well as ω-6 fatty acids, such as linolenic acid (LA) and arachidonic acid (AA). The PUFAs are predominantly metabolized by lipoxygenases (LOX) and, to a lesser extent by (acetylated) cyclooxygenases (COX) to generate SPMs, such as lipoxins, E-series resolvins, D-series resolvins, protectins and maresins (114). In general, SPMs are potent resolution agonists that extinguish the eicosanoid-induced inflammation by activating local resolution programs, eventually leading to tissue recovery (115, 116).

During an acute inflammatory event, the vasculature as well as local macrophages/microglia are activated, resulting in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as the activation of lipid mediator producing enzymes, such as COX and LOX. In general, COX activity supports the secretion of prostaglandins, like PGE2 and PGI2, leading to the migration of leukocytes, such as neutrophils to the site of inflammation. In this initial pro-inflammatory response, leukotriene B4 (LTB4) is produced by innate immune cells, also attracting leukocytes toward the site of inflammation. This pro-inflammatory lipid mediator response is changed to a pro-resolving response in a process called lipid mediator class switching (117). In particular, this consists of the change of AA metabolism from pro-inflammatory LTB4 to a pro-resolving lipoxin A4 (LXA4) lipid mediator production in response to inflammation (e.g., eosinophils) or due to a phenotype switch (e.g., macrophages). Four LXA4-biosynthesis pathways that are involved in class switching are currently known. First, protein kinase A gets activated by PGE2 resulting in the phosphorylation of 5-LOX. This increases LXA4 synthesis and inhibits LTB4 (118). Secondly, neutrophils induce 15-LOX-mediated LXA4 synthesis and downregulate 5-LOX mediated LTB4 synthesis, induced by PGE2 (115). Thirdly, endotoxin or extracellular ATP can induce hydrolytic release of the esterified 15-HETE and synthesize LXA4 via 5-LOX pathway (119). Finally, the activity of 12/15-LOX can catalyze LTA4 conversion to LXA4 (120). Overall, increasing LXA4 synthesis contributes to the decreased leukocyte migration toward the site of inflammation and is, therefore, the first step in the resolution response.

The E and D series resolvins, protectins, and maresins, derived from ω-3 fatty acids, are metabolized by LOX and/or CYP450 (115, 121). These SPMs are locally secreted to stimulate macrophage/microglia phenotype switching toward a pro-resolving phenotype. In turn, this promotes efferocytosis for the clearance of debris and downregulates the activity of the adaptive immune system to facilitate the return to tissue homeostasis (122, 123). Therefore, anti-inflammation and pro-resolution are not equivalent. The SPMs that actively promote resolution are fundamentally different from the antagonists that limit the duration and magnitude of the inflammatory response at both the molecular and cellular levels (124).

Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators in AD

An important process in the return to tissue homeostasis after the onset of acute inflammation is inflammation resolution via SPMs. When resolution fails, acute inflammation will acquire a chronic phenotype, resulting in severe tissue damage. Chronic inflammation in AD is possibly caused by alterations in the SPM production machinery (125). Of note, it was shown that APOE4 may mechanistically impact the neuropathogenesis of AD by decreasing DHA transport into the brain, which in turn, may lead to lower SPM levels in patients (126). Understanding the mechanisms behind this resolution failure can therefore be of clinical value for the treatment of AD.

Currently, only a few studies have addressed the potential effects of SPMs in AD. For example, lower levels of LXA4 are found in post-mortem hippocampal tissue as well as CSF compared to controls (125). Additionally, CSF levels of LXA4 and RvD1 are correlated with the mini-mental state examination scores, suggesting that the impaired resolution of neuroinflammation is involved in the cognitive decline in AD (127). Additionally, higher levels of 15-LOX-2, 15-LOX-1 and 5-LOX enzymes are observed in AD hippocampus. However, these enzymes are also known to mediate the production of pro-inflammatory lipid mediators and depend on class switching to generate SPMs (117). Therefore, it is possible that the increase of 15-LOX and 5-LOX together with the lack of lipid class switching facilitates the ongoing pro-inflammatory response (125, 128, 129). This also suggests that AD progression might be reduced when altered local SPM levels are restored. Indeed, treatment with aspirin-triggered LXA4 was shown to ameliorate Aβ and tau pathology in vivo (130). In addition, enhancing LXA4 signaling by using aspirin leads to reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine levels, while anti-inflammatory IL-10 levels are elevated, leading to more pro-resolving microglia phenotypes, Aβ phagocytosis and improved cognition (127). Similar to LXA4, RvD1 induces an pro-resolving microglia phenotype and enhances microglia-mediated Aβ phagocytosis (131). Besides LXA4, maresin-1 is also decreased in post-mortem hippocampal tissue and CSF of AD patients compared to controls (125). Importantly, in vitro experiments with the CHME3 microglial cell line revealed enhanced Aβ phagocytosis and attenuated microglia activation when incubated with maresin-1 (132). Together, these findings suggest that administering disease-affected SPMs or activating local SPM biosynthesis during AD could be an interesting therapeutic approach to resolve chronic inflammation and thereby prevent neurodegeneration.

Sphingolipid Mediated Resolution of Neuroinflammation via SPMs

So far, only few studies have reported on the interplay of the SL and SPM machinery and the role thereof in AD is now emerging. Interestingly, Young Lee and colleagues demonstrated a direct anti-inflammatory correlation between the SL machinery and SPMs in AD (133, 134). Neuronal SK1 appears to generate N-acetyl sphingosine via acetyl-CoA and sphingosine, followed by the acetylation of serine residue 565 of COX-2 by N-acetyl sphingosine. This activates COX-2 mediated 15-HETE, 18-HEPE, and 17-HDHA production, which can be converted to SPMs, such as 15R-LXA4, RvE1, and RvD1. In APP/PS1 mice, SK1 is severely decreased in neurons but not in microglia, causing a decrease in N-acetyl sphingosine and therefore a decline in SPM production and secretion by neurons. The increased or decreased SK1 levels result in altered SPM levels as well as phagocytosis of Aβ by microglia in APP/PS1 mice, respectively (133, 134). Of note, SK1 levels appear to be reduced in post-mortem AD affected brains (103, 133). This suggests that neuronal SK1 fulfils an anti-inflammatory role during neuroinflammation in AD. Additionally, N-acetyl sphingosine is decreased in microglia, caused by deficient acetyl-CoA, reducing acetylated COX-2 and SPM secretion by Aβ activated microglia from C57BL/6 mice. Treating 5xFAD and APP/PS1 mice with N-acetyl sphingosine increased COX-2 acetylation and subsequent SPM biosynthesis in microglia (134). This facilitates the resolution of neuroinflammation and enhances the phagocytosis of Aβ by microglia. Overall, these findings indicate that the sphingolipid machinery has an immune regulatory function by activating SPM biosynthesis in the CNS via COX-2 acetylation (Figures 1 and 3). Moreover, the immune regulation via sphingolipids seems to be dysregulated in AD, providing a new framework to reinstate the resolution of neuroinflammation in AD.

Sphingolipid and SPM Based Therapeutic Approaches for AD

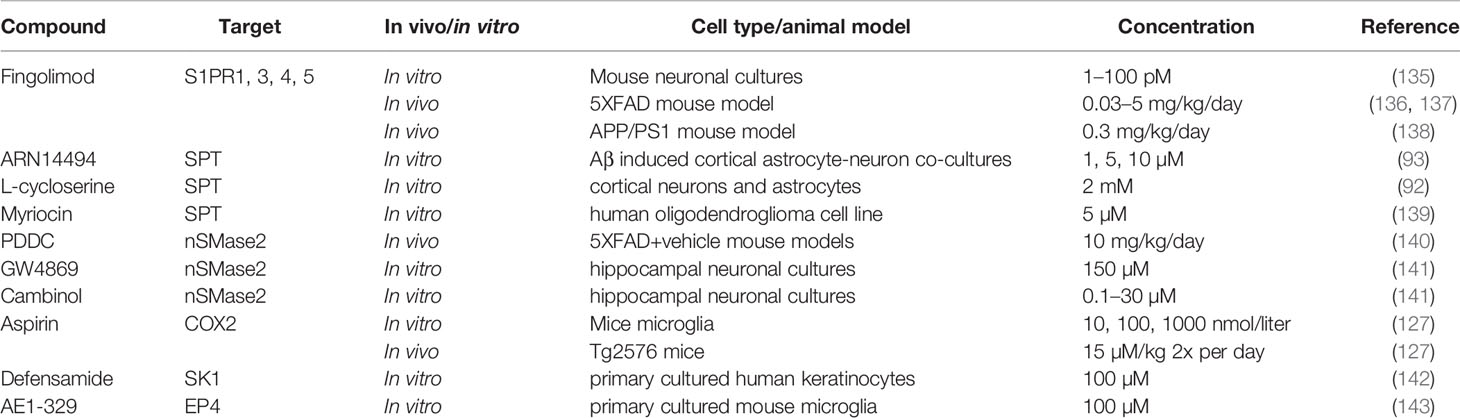

Although the fundamental knowledge about SLs and SPM metabolism in the CNS during healthy and pathological situations remains to be fully elucidated, it has been demonstrated that changes in their metabolic pathways occur during AD pathogenesis as described above. In turn, this paves the way to include their receptors, metabolites, and involved machinery as possible therapeutic targets to limit the progression of AD. Various strategies targeting these pathways will be discussed below (see Table 1 for complete overview).

Potential S1P Metabolism-Related Therapeutic Targets and Therapies

S1P signaling through S1PR1 demonstrated to be a possible initiator for pro-inflammatory immune responses of microglia (108). Inhibition of S1PR1 signaling could, therefore, be an interesting approach to attenuate neuroinflammation in AD. Fingolimod (FTY720) is a functional antagonist that promotes initial activation followed by sustained internalization and desensitization of several S1PRs in lymphocytes, except S1PR2 (144). Fingolimod is approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) as a treatment for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) and has the potential to target major processes in AD pathogenesis as well, including Aβ toxicity and production, neuroinflammation and neuronal loss. In vitro experiments demonstrated that Fingolimod ameliorates Aβ toxicity in neuronal cultures via increased concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (135, 145). In vivo models, using the 5XFAD transgenic AD mouse model, displayed decreased signs of neuroinflammation and cognitive improvement when given a low dose (0.03 mg/kg/day) (136, 137). Other experiments demonstrated that Fingolimod attenuates pro-inflammatory chemokine release in both astrocytes and microglia (108, 109). Furthermore, Aβ load is decreased in APP/PS1 mice by the inhibition of β-secretase when treated with Fingolimod, possibly by modulating the transport of Aβ through the BBB (138). Taken together, this shows that Fingolimod is a promising new therapeutic approach for AD. Moreover, other neurodegenerative or neuro-inflammatory diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and epilepsy also explore the use of Fingolimod as possible treatment because of its diverse anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects (146). However, although different animal models show promising results upon treatment with Fingolimod, further experiments, as well as clinical studies, should elucidate if patients indeed benefit from Fingolimod as medication.

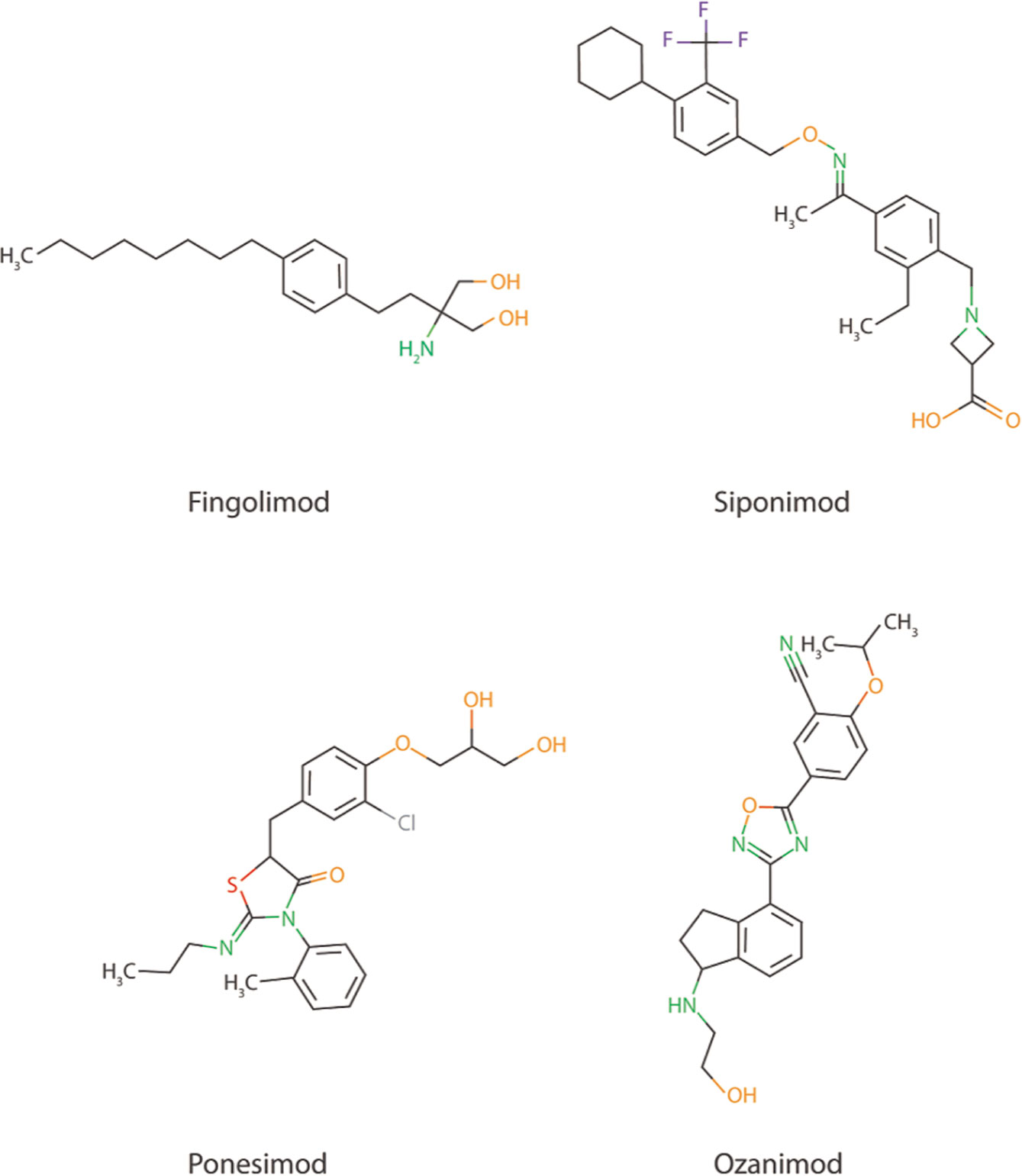

The promising preclinical results of S1PR inhibitor Fingolimod also creates possibilities for the use of other more selective S1PR inhibitors, such as Ponesimod (acts via S1PR1), Siponimod (acts via S1PR1 and S1PR5), and Ozanimod (acts via S1PR1 and S1PR5) in AD (Figure 2), especially since Fingolimod targets all S1P receptors (except S1PR2), creating potential harmful side effects (147, 148). Currently, the use of these S1PR inhibitors are focused on therapy development for MS and no scientific literature is describing their use in AD models. Another strategy to interfere in the S1P signaling could be via the inhibition of the S1P transporter Spns2. As described earlier, Spns2 knockout mice display reduced inflammatory microglia phenotypes and Spns2 is possibly involved in the Aβ42-induced NF-κB signaling and cognitive decline. Additionally, Spns2 forms a complex with major facilitator superfamily domain-containing 2a (Mfsd2a) to optimize S1P transport and shows involvement in maintaining BBB integrity by adjusting S1P concentrations (149). This indicates that S1P transport could potentially be inhibited via either Spns2 or Mfsd2a. Unfortunately, no inhibitors are currently available for both Spns2 and Mfsd2a.

Figure 2 Chemical structure of Fingolimod together with three other more selective S1PR inhibitors; Siponimod, Ponesimod, and Ozanimod.

Ceramide Synthesis Inhibition as a Therapeutic Target in AD

With enhanced levels of long-chain ceramides found in AD, inhibition of ceramide metabolism could be an interesting therapeutic approach. For instance, targeting the de novo ceramide synthesis by inhibiting SPT has already been investigated by using SPT inhibitors such as myriocin, ARN14494 and L-cycloserine. In vitro experiments with myriocin indicated that it inhibits ceramide synthesis via SPT in MS and its mouse model experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (139). However, myriocin has not been extensively tested for efficacy in AD models. In AD in vitro models, ARN14494 and L-cycloserine are capable of inhibiting SPT, resulting in decreased ceramide and pro-inflammatory cytokine levels (92, 93). While these initial in vitro results are promising, studies exploring the effect of SPT inhibition in vivo is needed to confirm whether these inhibitors have indeed anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects.

Targeting the sphingomyelinase pathway might be another approach to decrease ceramide levels. For instance, the knockdown of nSMase in Aβ activated astrocytes decreased their pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine secretion (89). GW4869 and Cambinol are proven inhibitors of nSMase and show neuroprotective and anti-neuroinflammatory properties (90, 141). However, these inhibitors have an unfavorable IC50 of >1µM. Additionally, GW4869 is insoluble and has a high molecular weight, creating difficulties for the conduction of (pre)clinical studies (141, 150). Recently a new nSMase2 inhibitor was identified, phenyl (R)-(1-(3- (3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-2,6-dimethylimidazo[1,2-b]pyridazin-8-yl)- pyrrolidin-3-yl)carbamate 1 (PDDC). This inhibitor showed in the 5XFAD+vehicle AD mouse model that it can penetrate the BBB, inhibit exosome release and neuroinflammation (140, 151). The first results with PDDC as nSMase2 inhibitor seem promising but, being a new compound, additional research is warranted.

Overall, the inhibition of ceramide synthesis pathways shows potential to function as a therapeutic approach for AD. A reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines is observed upon the use of ARN14494 and L-cycloserine to inhibit de novo synthesis in vitro. Additionally, PDDC already showed inhibitory effects on SMase ceramide synthesis pathways, decreasing neuroinflammation in vivo.

Boosting the Resolution of Neuroinflammation as a Novel Treatment Modality for AD

The exploitation of SPMs to resolve neuroinflammation in AD is still in its infancy. Several papers demonstrate that aspirin can acetylate COX-2, resulting in the blocking of prostaglandin biosynthesis and activation of SPM biosynthesis. For example, aspirin-triggered LXA4 production reduced NF-κB activation and pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine secretion in aspirin treated microglia. It also increased Aβ phagocytosis by microglia and improved cognitive function in Tg2576 mice (127). Aspirin is currently the only known therapeutic that inhibits the pro-inflammatory response and activates the anti-inflammatory response of COX-2. However, a clinical human trial showed no evidence that aspirin reduces the risk of AD (152).

Other therapeutic approaches could consist of SK1 activation via (S)-Methyl 2-(hexanamide)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl) propanoate (MHP), also known as Defensamide (142). Young Lee and colleagues demonstrated how SK1 has a pro-resolving effect on neuroinflammation via N-acetyl sphingosine generation followed by COX-2 acetylation, resulting in SPM biosynthesis (133, 134). It can therefore be hypothesized that activation of SK1 by Defensamide might be a novel SPM promoting therapeutic approach. Currently, Defensamide was shown to activate SK1 in human keratinocytes (an epidermal cell line), however, it is not known if this activation also increases N-acetyl sphingosine generation and no publications discuss its effect in an AD experimental setup (142). The effect of Defensamide remains, therefore, to be established.

An important event in the resolution of neuroinflammation is lipid mediator class-switching. This can for example be induced by the activation of E-prostanoid (EP)4 receptor by PGE2. In turn, this enhances LOX-15 production that induces LXA4 biosynthesis (153). This indicates that activation of EP4 during neuroinflammation in AD could represent a new therapeutic approach. Indeed, AD in vitro microglial experiments showed that EP4 receptor activation by EP4 receptor agonist AE1–329 attenuates Aβ induced ROS, pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression. Additionally, EP4 receptor expression levels seem to be reduced in human post-mortem AD brain (143). This indicates that activating the EP4 receptor via AE1-329 might be a possible new therapeutic route for the resolution of neuroinflammation during AD, but the lowered expression of EP4 may attenuate its effects. Currently, only one paper discusses the effect of AE1-329 in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia, confirming that AE1-329 does enter the brain and therefore could be implemented in AD mouse model studies (154). Overall, research into new therapeutics for the targeting of SPM metabolism in AD is still at the beginning, but some publications show that modulation of the SPM metabolism can be applied as a potential novel treatment strategy.

Discussion and Future Directions

Our understanding of neuroinflammation in AD has tremendously increased over the last decade. With this, it became clear that both SL and SPM metabolism are major players in the onset and resolution of excessive neuroinflammation during AD. Increased ceramide and SMase levels are found in AD brain and showed to be part of the signaling cascades for pro-inflammatory responses (87, 95). S1P signaling in AD remains controversial, as levels are increased in mild cognitive impairment patients but are attenuated in cases with more advanced AD (104). The exact mechanisms underlying SL metabolism alterations in AD patients is largely unknown. Additionally, several SPMs are reduced in AD patient tissues and body fluids, suggesting potential defects in resolution pathways, but how this decrease in SPM levels is mediated remains to be established. Interestingly, it was suggested that SK1 can generate N-acetyl sphingosine that acetylates COX-2, resulting in activation of the SPM production (133, 134). This suggests that SL metabolism is involved in the resolution of neuroinflammation via SPM biosynthesis, thereby providing a direct link between these bioactive lipid pathways (Figures 1 and 3). In short, although increased understanding of SL and SPM metabolism in AD is gained over the years, extended research should be conducted to further understand its involvement in AD pathology. This includes getting a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms that are involved in lowering SK1 and subsequent SPM levels, as well as increased ceramide levels.

Figure 3 The role of sphingolipids and specialized pro-resolving mediators in health and disease. In healthy conditions, neurons maintain a proper balance of sphingolipids. The abundant SK1 enzyme deviates the sphingolipid pathway toward SPM production and secretion. Secreted SPMs reach perineuronal microglia, promoting their pro-resolving phenotype. Pro-resolving microglia maintain a healthy microenvironment by clearing amyloid beta through phagocytosis. In AD, there is a dysregulation of sphingolipids and SPMs, which correlates with the levels of hyperphosphorylated tau and Aβ. Reduced levels of the enzyme SK1 result in less SPM production and secretion. Microglia become pro-inflammatory, and start secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines. Aβ is no longer cleared, leading to the formation of extracellular amyloid plaques. These plaques further contribute to neurotoxicity.

Although the development of SL and SPM therapeutics is still in its infancy, several potential compounds show beneficial effects on reducing neuroinflammation, increasing Aβ phagocytosis, and decreasing the levels of phosphorylated tau (90, 92, 130, 135, 139–141, 145, 151). Fingolimod is one of those prime candidates, demonstrating decreased neuroinflammation in both in vitro and in vivo models of AD. Additionally, Fingolimod is already approved by the EMA as therapy for MS. This makes Fingolimod one of the most promising therapeutic compounds to reduce the pro-inflammatory response via S1PRs in AD. Therefore, additional research with AD models should be conducted, focusing on the inhibition of neuroinflammation using S1P receptor specific therapeutic compounds like Ponesimod, Siponimod, and Ozanimod.

Therapeutics that focus on the downregulation of ceramide syntheses, such as PDDC, ARN14494, and L-cycloserine, are possibly effective to fight progression of AD pathology, as ceramide levels appear to be increased throughout AD progression. However, Fingolimod and Defensamide are possibly most effective during the early stages of AD. For instance, SK1 levels are decreased in post-mortem brain tissue of AD patients. In addition, mild cognitive impairment patients show high S1P levels, but their levels decrease during the progression of AD. Therefore, the effects of possible treatments should be studied throughout AD progression to determine the most effective treatment window.

In conclusion, SL and SPM metabolism are essential players in the onset and resolution of neuroinflammation in AD (Figure 3). Increasing our knowledge about alterations in their metabolism and signaling, and more importantly about the interplay between SLs and SPMs metabolism will provide new perspectives for the development of innovative therapies for AD based on resolution pharmacology. It is therefore of major importance to gain more insight in the coming years into the underlying mechanism of action by which SLs and SPM signaling and metabolism act during tissue homeostasis and neuroinflammation in AD.

Author Contributions

This manuscript was written by NW, KM, and GK. SRL provided the illustration. HV and SRL contributed in revising the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from IMI (807015 to NW), a grant from the Dutch MS Research Foundation (20-1087 MS to SRL), as well as a grant from the Dutch Research Council (NWO Vidi grant 91719305 to GK).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Lawson LJ, Perry VH, Dri P, Gordon S. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience (1990) 39(1):151–70. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90229-W

2. Sofroniew MV, Vinters HV. Astrocytes: Biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol (2010) 119:7–35. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0619-8

3. Tognatta R, Miller RH. Contribution of the oligodendrocyte lineage to CNS repair and neurodegenerative pathologies. Neuropharmacology (2016) 110:539–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.04.026

4. Daneman R, Prat A. The blood–brain barrier. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2015) 7(1):a020412. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020412

5. Wit N, Kooij G, Vries H. In Vitro and Ex Vivo Model Systems to Measure ABC Transporter Activity at the Blood-Brain Barrier. Curr Pharm Des (2016) 22(38):5768–73. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160810145536

6. Catalá-López F, Gènova-Maleras R, Vieta E, Tabarés-Seisdedos R. The increasing burden of mental and neurological disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol (2013) 23:1337–9. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.04.001

7. Andreone BJ, Chow BW, Tata A, Lacoste B, Ben-Zvi A, Bullock K, et al. Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Is Regulated by Lipid Transport-Dependent Suppression of Caveolae-Mediated Transcytosis. Neuron (2017) 94(3):581–594.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.043

8. Loving BA, Bruce KD. Lipid and Lipoprotein Metabolism in Microglia. Front Physiol (2020) 11:393. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00393

9. Schmitt S, Cantuti Castelvetri L, Simons M. Metabolism and functions of lipids in myelin. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Cell Biol Lipids (2015) 1851:999–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.12.016

10. Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci (2008), 9:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297

11. Ardura-Fabregat A, Boddeke EWGM, Boza-Serrano A, Brioschi S, Castro-Gomez S, Ceyzériat K, et al. Targeting Neuroinflammation to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease. CNS Drugs (2017) 31:1057–82. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0483-3

12. Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, Landreth GE, Brosseron F, Feinstein DL, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol (2015) 14:388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5

13. World Alzheimer Report. World Alzheimer Report 2019, Attitudes to dementia. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International (2019).

14. Guerreiro RJ, Gustafson DR, Hardy J. The genetic architecture of Alzheimer’s disease: Beyond APP, PSENS and APOE. Neurobiol Aging (2012) 33:437–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.03.025

15. Holtzman DM, Herz J, Bu G, Apolipoprotein E. and apolipoprotein E receptors: Normal biology and roles in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med (2012) 2(3):a006312. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006312

16. Herz J, Chen Y, Masiulis I, Zhou L. Expanding functions of lipoprotein receptors. J Lipid Res (2009) 50(SUPPL.):S287–92. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800077-JLR200

17. Montagne A, Nation DA, Sagare AP, Barisano G, Sweeney MD, Chakhoyan A, et al. APOE4 leads to blood–brain barrier dysfunction predicting cognitive decline. Nature (2020) 581(7806):71–6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2247-3

18. Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, et al. The precursor of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature (1987) 325(6106):733–6. doi: 10.1038/325733a0

19. Vassar R, Bennett BD, Babu-Khan S, Kahn S, Mendiaz EA, Denis P, et al. β-Secretase cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science (80- ) (1999) 286(5440):735–41. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735

20. Laurén J, Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Gilbert JW, Strittmatter SM. Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-B oligomers. Nature (2009) 457(7233):1128–32. doi: 10.1038/nature07761

21. Yasumoto T, Takamura Y, Tsuji M, Watanabe-Nakayama T, Imamura K, Inoue H, et al. High molecular weight amyloid β1-42 oligomers induce neurotoxicity via plasma membrane damage. FASEB J (2019) 33(8):9220–34. doi: 10.1096/fj.201900604R

22. Shen LL, Li WW, Xu YL, Gao SH, Xu MY, Le Bu X, et al. Neurotrophin receptor p75 mediates amyloid β-induced tau pathology. Neurobiol Dis (2019) 132:104567. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104567

23. Fukuyama R, Wadhwani KC, Galdzicki Z, Rapoport SI, Ehrenstein G. β-Amyloid polypeptide increases calcium-uptake in PC12 cells: a possible mechanism for its cellular toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res (1994) 667(2):269–72. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91505-9

24. Rosen KM, Moussa CEH, Lee HK, Kumar P, Kitada T, Qin G, et al. Parkin reverses intracellular β-amyloid accumulation and its negative effects on proteasome function. J Neurosci Res (2010) 88(1):167–78. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22178

25. Caspersen C, Wang N, Yao J, Sosunov A, Chen X, Lustbader JW, et al. Mitochondrial Aβ: a potential focal point for neuronal metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J (2005) 19(14):2040–1. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3735fje

26. Kadavath H, Hofele RV, Biernat J, Kumar S, Tepper K, Urlaub H, et al. Tau stabilizes microtubules by binding at the interface between tubulin heterodimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2015) 112(24):7501–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504081112

27. Dawson HN, Ferreira A, Eyster MV, Ghoshal N, Binder LI, Vitek MP. Inhibition of neuronal maturation in primary hippocampal neurons from tau deficient mice. J Cell Sci (2001) 114(6):1179–87.

28. Esmaeli-Azad B, McCarty JH, Feinstein SC. Sense and antisense transfection analysis of tau function: Tau influences net microtubule assembly, neurite outgrowth and neuritic stability. J Cell Sci (1994) 107(4):869–79.

29. Alonso AD, Cohen LS, Corbo C, Morozova V, ElIdrissi A, Phillips G, et al. Hyperphosphorylation of Tau Associates with changes in its function beyond microtubule stability. Front Cell Neurosci (2018) 12:338. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00338

30. Cash AD, Aliev G, Siedlak SL, Nunomura A, Fujioka H, Zhu X, et al. Microtubule reduction in Alzheimer’s disease and aging is independent of τ filament formation. Am J Pathol (2003) 162(5):1623–7. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64296-4

31. Tai HC, Wang BY, Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Spires-Jones TL, Hyman BT. Frequent and symmetric deposition of misfolded tau oligomers within presynaptic and postsynaptic terminals in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun (2014) 2(1):146. doi: 10.1186/s40478-014-0146-2

32. Lampron A, ElAli A, Rivest S. Innate Immunity in the CNS: Redefining the relationship between the CNS and its Environment. Neuron (2013) 78(2):214–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.005

33. Xiao BG, Ma CG, Xu LY, Link H, Lu CZ. IL-12/IFN-γ/NO axis plays critical role in development of Th1-mediated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Mol Immunol (2008) 45(4):1191–6. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.07.003

34. Imler TJ, Petro TM. Decreased severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis during resveratrol administration is associated with increased IL-17+IL-10+ T cells, CD4- IFN-γ+ cells, and decreased macrophage IL-6 expression. Int Immunopharmacol (2009) 9(1):134–43. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.10.015

35. Hewett SI, Csernansky CA, Choi DW. Selective potentiation of NMDA-induced neuronal injury following induction of astrocytic iNOS. Neuron (1994) 13(2):487–94. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90362-X

36. Zekry D, Kay Epperson T, Krause KH. A role for NOX NADPH oxidases in Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia? IUBMB Life (2003) 55:307–13. doi: 10.1080/1521654031000153049

37. Butovsky O, Weiner HL. Microglial signatures and their role in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci (2018) 19:622–35. doi: 10.1038/s41583-018-0057-5

38. O’Keefe GM, Nguyen VT, Benveniste EN. Class II transactivator and class II MHC gene expression in microglia: Modulation by the cytokines TGF-β, IL-4, IL-13 and IL-10. Eur J Immunol (1999) 29(4):1275–85. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199904)29:04<1275::AID-IMMU1275>3.0.CO;2-T

39. Liu S, Liu Y, Hao W, Wolf L, Kiliaan AJ, Penke B, et al. TLR2 Is a Primary Receptor for Alzheimer’s Amyloid β Peptide To Trigger Neuroinflammatory Activation. J Immunol (2012) 188(3):1098–107. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101121

40. Alasmari F, Alshammari MA, Alasmari AF, Alanazi WA, Alhazzani K. Neuroinflammatory Cytokines Induce Amyloid Beta Neurotoxicity through Modulating Amyloid Precursor Protein Levels/Metabolism. BioMed Res Int (2018) 2018:3087475. doi: 10.1155/2018/3087475

41. Krabbe G, Halle A, Matyash V, Rinnenthal JL, Eom GD, Bernhardt U, et al. Functional Impairment of Microglia Coincides with Beta-Amyloid Deposition in Mice with Alzheimer-Like Pathology. PloS One (2013) 8(4):e60921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060921

42. Choi SS, Lee HJ, Lim I, Satoh JI, Kim SU. Human astrocytes: Secretome profiles of cytokines and chemokines. PloS One (2014) 9(4):e92325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092325

43. Carrano A, Hoozemans JJM, Van Der Vies SM, Van Horssen J, De Vries HE, Rozemuller AJM. Neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier changes in capillary amyloid angiopathy. Neurodegener Dis (2012) 10(1–4):329–31. doi: 10.1159/000334916

44. Veszelka S, Tóth AE, Walter FR, Datki Z, Mózes E, Fülöp L, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid reduces amyloid-β induced toxicity in cells of the neurovascular unit. J Alzheimers Dis (2013) 36(3):487–501. doi: 10.3233/JAD-120163

45. Merlini M, Meyer EP, Ulmann-Schuler A, Nitsch RM. Vascular β-amyloid and early astrocyte alterations impair cerebrovascular function and cerebral metabolism in transgenic arcAβ mice. Acta Neuropathol (2011) 122(3):293–311. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0834-y

46. Sagare AP, Bell RD, Zhao Z, Ma Q, Winkler EA, Ramanathan A, et al. Pericyte loss influences Alzheimer-like neurodegeneration in mice. Nat Commun (2013) 4:2932. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3932

47. Unger MS, Li E, Scharnagl L, Poupardin R, Altendorfer B, Mrowetz H, et al. CD8+ T-cells infiltrate Alzheimer’s disease brains and regulate neuronal- and synapse-related gene expression in APP-PS1 transgenic mice. Brain Behav Immun (2020) 89:67–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.070

48. Fiala M, Zhang L, Gan X, Sherry B, Taub D, Graves MC, et al. Amyloid-β induces chemokine secretion and monocyte migration across a human blood-brain barrier model. Mol Med (1998) 4(7):480–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03401753

49. Baik SH, Cha MY, Hyun YM, Cho H, Hamza B, Kim DK, et al. Migration of neutrophils targeting amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Neurobiol Aging (2014) 35(6):1286–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.01.003

50. Browne TC, McQuillan K, McManus RM, O’Reilly J-A, Mills KHG, Lynch MA. IFN-γ Production by Amyloid β–Specific Th1 Cells Promotes Microglial Activation and Increases Plaque Burden in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Immunol (2013) 190(5):2241–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200947

51. Hamilton JA, Hillard CJ, Spector AA, Watkins PA. Brain uptake and utilization of fatty acids, lipids and lipoproteins: Application to neurological disorders. J Mol Neurosci (2007) 33:2–11. doi: 10.1007/s12031-007-0060-1

52. Fahy E, Cotter D, Sud M, Subramaniam S. Lipid classification, structures and tools. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Cell Biol Lipids (2011) 1811(11):637–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.06.009

53. van Echten-Deckert G, Herget T. Sphingolipid metabolism in neural cells. Biochim Biophys Acta - Biomembr (2006) 1758(12):1978–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.06.009

54. Gualtierotti R, Guarnaccia L, Beretta M, Navone SE, Campanella R, Riboni L, et al. Modulation of Neuroinflammation in the Central Nervous System: Role of Chemokines and Sphingolipids. Adv Ther (2017) 34(2):396–420. doi: 10.1007/s12325-016-0474-7

55. Maceyka M, Payne SG, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Sphingosine kinase, sphingosine-1-phosphate, and apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Cell Biol Lipids (2002) 1585(2–3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/S1388-1981(02)00341-4

56. Mandon EC, Ehses I, Rother J, Van Echten G, Sandhoff K. Subcellular localization and membrane topology of serine palmitoyltransferase, 3-dehydrosphinganine reductase, and sphinganine N- acyltransferase in mouse liver. J Biol Chem (1992) 267(16):11144–8. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)49887-6

57. Clarke CJ, Snook CF, Tani M, Matmati N, Marchesini N, Hannun YA. The extended family of neutral sphingomyelinases. Biochemistry (2006) 45(38):11247–56. doi: 10.1021/bi061307z

58. Jenkins RW, Canals D, Hannun YA. Roles and regulation of secretory and lysosomal acid sphingomyelinase. Cell Signal (2009) 21(6):836–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.026

59. Kitatani K, Idkowiak-Baldys J, Hannun YA. The sphingolipid salvage pathway in ceramide metabolism and signaling. Cell Signal (2008) 20:1010–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.006

60. Zhang H, Desai NN, Olivera A, Seki T, Brooker G, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate, a novel lipid, involved in cellular proliferation. J Cell Biol (1991) 114(1):155–67. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.1.155

61. Kim MY, Linardic C, Obeid L, Hannun Y. Identification of sphingomyelin turnover as an effector mechanism for the action of tumor necrosis factor α and γ-interferon. Specific role in cell differentiation. J Biol Chem (1991) 266(1):484–9. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)52461-3

62. Ramos B, El Mouedden M, Claro E, Jackowski S. Inhibition of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase by C2-ceramide and its relationship to apoptosis. Mol Pharmacol (2002) 62(5):1068–75. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.1068

63. Józefowski S, Czerkies M, Łukasik A, Bielawska A, Bielawski J, Kwiatkowska K, et al. Ceramide and Ceramide 1-Phosphate Are Negative Regulators of TNF-α Production Induced by Lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol (2010) 185(11):6960–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902926

64. Schütze S, Potthoff K, Machleidt T, Berkovic D, Wiegmann K, Krönke M. TNF activates NF-κB by phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C-induced “Acidic” sphingomyelin breakdown. Cell (1992) 71(5):765–76. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90553-O

65. Aggarwal BB. Nuclear factor-κB: The enemy within. Cancer Cell (2004) 6:203–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.003

66. Jung JS, Shin KO, Lee YM, Shin JA, Park EM, Jeong J, et al. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of exogenous C2 ceramide in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated microglia. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Cell Biol Lipids (2013) 1831(6):1016–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.01.020

67. Hsu Y-W, Chi K-H, Huang W-C, Lin W-W. Ceramide Inhibits Lipopolysaccharide-Mediated Nitric Oxide Synthase and Cyclooxygenase-2 Induction in Macrophages: Effects on Protein Kinases and Transcription Factors. J Immunol (2001) 166(9):5388–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5388

68. Cho YH, Lee CH, Kim SG. Potentiation of lipopolysaccharide-inducible cyclooxygenase 2 expression by C2-ceramide via c-Jun N-terminal kinase-mediated activation of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β in macrophages. Mol Pharmacol (2003) 63(3):512–23. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.3.512

69. Lukiw WJ, Bazan NG. Strong nuclear factor-κB-DNA binding parallels cyclooxygenase-2 gene transcription in aging and in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease superior temporal lobe neocortex. J Neurosci Res (1998) 53(5):583–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980901)53:5<583::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-5

70. Ben-David O, Futerman AH. The role of the ceramide acyl chain length in neurodegeneration: Involvement of ceramide synthases. NeuroMolecular Med (2010) 12(4):341–50. doi: 10.1007/s12017-010-8114-x

71. Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Many ceramides. J Biol Chem (2011) 286:27855–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.254359

72. Mencarelli C, Martinez-Martinez P. Ceramide function in the brain: When a slight tilt is enough. Cell Mol Life Sci (2013) 70(2):181–203. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1038-x

73. Bassi R, Anelli V, Giussani P, Tettamanti G, Viani P, Riboni L. Sphingosine-1-phosphate is released by cerebellar astrocytes in response to bFGF and induces astrocyte proliferation through Gi-protein-coupled receptors. Glia (2006) 53(6):621–30. doi: 10.1002/glia.20324

74. Nagahashi M, Takabe K, Terracina KP, Soma D, Hirose Y, Kobayashi T, et al. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Transporters as Targets for Cancer Therapy. BioMed Res Int (2014) 2014:651727. doi: 10.1155/2014/651727

75. van Doorn R, Lopes Pinheiro MA, Kooij G, Lakeman K, van het Hof B, van der Pol SMA, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 5 mediates the immune quiescence of the human brain endothelial barrier. J Neuroinflammation (2012) 9:663. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-133

76. Brinkmann V. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors in health and disease: Mechanistic insights from gene deletion studies and reverse pharmacology. Pharmacol Ther (2007) 115:84–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.04.006

77. Nayak D, Huo Y, Kwang WXT, Pushparaj PN, Kumar SD, Ling EA, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 regulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide in activated microglia. Neuroscience (2010) 166(1):132–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.020

78. Karunakaran I, Alam S, Jayagopi S, Frohberger SJ, Hansen JN, Kuehlwein J, et al. Neural sphingosine 1-phosphate accumulation activates microglia and links impaired autophagy and inflammation. Glia (2019) 67(10):1859–72. doi: 10.1002/glia.23663

79. Wu YP, Mizugishi K, Bektas M, Sandhoff R, Proia RL. Sphingosine kinase 1/S1P receptor signaling axis controls glial proliferation in mice with Sandhoff disease. Hum Mol Genet (2008) 17(15):2257–64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn126

80. Gaire BP, Lee CH, Sapkota A, Lee SY, Chun J, Cho HJ, et al. Identification of Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor Subtype 1 (S1P1) as a Pathogenic Factor in Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Mol Neurobiol (2018) 55(3):2320–32. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0468-8

81. Van Doorn R, Nijland PG, Dekker N, Witte ME, Lopes-Pinheiro MA, Van Het Hof B, et al. Fingolimod attenuates ceramide-induced blood-brain barrier dysfunction in multiple sclerosis by targeting reactive astrocytes. Acta Neuropathol (2012) 124(3):397–410. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1014-4

82. Singleton PA, Dudek SM, Chiang ET, Garcia JGN. Regulation of sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced endothelial cytoskeletal rearrangement and barrier enhancement by S1P 1 receptor, PI3 kinase, Tiam1/Rac1, and α-actinin. FASEB J (2005) 19(12):1646–56. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3928com

83. Sanchez T, Estrada-Hernandez T, Paik JH, Wu MT, Venkataraman K, Brinkmann V, et al. Phosphosrylation and Action of the Immunomodulator FTY720 Inhibits ‘Vascular Endothelial Cell Growth Factor-induced Vascular Permeability. J Biol Chem (2003) 278(47):47281–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306896200

84. Spampinato SF, Obermeier B, Cotleur A, Love A, Takeshita Y, Sano Y, et al. Sphingosine 1 phosphate at the blood brain barrier: Can the modulation of S1P receptor 1 influence the response of endothelial cells and astrocytes to inflammatory stimuli? PloS One (2015) 10(7):e0133392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133392

85. Singleton PA, Dudek SM, Ma SF, Garcia JGN. Transactivation of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors is essential for vascular barrier regulation: Novel role for hyaluronan and CD44 receptor family. J Biol Chem (2006) 281(45):34381–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603680200

86. Varma VR, Oommen AM, Varma S, Casanova R, An Y, Andrews RM, et al. Brain and blood metabolite signatures of pathology and progression in Alzheimer disease: A targeted metabolomics study. PloS Med (2018) 15(1):e1002482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002482

87. Alessenko AV, Bugrova AE, Dudnik LB. Connection of lipid peroxide oxidation with the sphingomyelin pathway in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Soc Trans (2004) 32:144–6. doi: 10.1042/bst0320144

88. He X, Huang Y, Li B, Gong CX, Schuchman EH. Deregulation of sphingolipid metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging (2010) 31(3):398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.05.010

89. Jana A, Pahan K. Fibrillar amyloid-β-activated human astroglia kill primary human neurons via neutral sphingomyelinase: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci (2010) 30(38):12676–89. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1243-10.2010

90. Wang G, Dinkins M, He Q, Zhu G, Poirier C, Campbell A, et al. Astrocytes secrete exosomes enriched with proapoptotic ceramide and Prostate Apoptosis Response 4 (PAR-4): Potential mechanism of apoptosis induction in Alzheimer Disease (AD). J Biol Chem (2012) 287(25):21384–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.340513

91. Geekiyanage H, Upadhye A, Chan C. Inhibition of serine palmitoyltransferase reduces Aβ and tau hyperphosphorylation in a murine model: a safe therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging (2013) 34(8):2037–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.02.001

92. Patil S, Melrose J, Chan C. Involvement of astroglial ceramide in palmitic acid-induced Alzheimer-like changes in primary neurons. Eur J Neurosci (2007) 26(8):2131–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05797.x

93. De Vita T, Albani C, Realini N, Migliore M, Basit A, Ottonello G, et al. Inhibition of Serine Palmitoyltransferase by a Small Organic Molecule Promotes Neuronal Survival after Astrocyte Amyloid Beta 1-42 Injury. ACS Chem Neurosci (2019) 10(3):1627–35. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00556

94. De Wit NM, Snkhchyan H, Den Hoedt S, Wattimena D, De Vos R, Mulder MT, et al. Altered Sphingolipid Balance in Capillary Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. J Alzheimers Dis (2017) 60(3):795–807. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160551

95. Filippov V, Song MA, Zhang K, Vinters HV, Tung S, Kirsch WM, et al. Increased ceramide in brains with alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. J Alzheimers Dis (2012) 29(3):537–47. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111202

96. Panchal M, Gaudin M, Lazar AN, Salvati E, Rivals I, Ayciriex S, et al. Ceramides and sphingomyelinases in senile plaques. Neurobiol Dis (2014) 65:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.01.010

97. Satoi H, Tomimoto H, Ohtani R, Kitano T, Kondo T, Watanabe M, et al. Astroglial expression of ceramide in Alzheimer’s disease brains: A role during neuronal apoptosis. Neuroscience (2005) 130(3):657–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.056

98. Mielke MM, Haughey NJ. Could plasma sphingolipids be diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease? Clin Lipidol (2012) 7(5):525–36. doi: 10.2217/clp.12.59

99. Crivelli SM, Giovagnoni C, Visseren L, Scheithauer AL, de Wit N, den Hoedt S, et al. Sphingolipids in Alzheimer’s disease, how can we target them? Adv Drug Deliv Rev (2020) 159:214–31. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.12.003

100. Jazvinšćak Jembrek M, Hof PR, Šimić G. Ceramides in Alzheimer’s Disease: Key Mediators of Neuronal Apoptosis Induced by Oxidative Stress and A β Accumulation. Oxid Med Cell Longev (2015) 2015:1–17. doi: 10.1155/2015/346783

101. Pchejetski D, Kunduzova O, Dayon A, Calise D, Seguelas MH, Leducq N, et al. Oxidative stress-dependent sphingosine kinase-1 inhibition mediates monoamine oxidase A-associated cardiac cell apoptosis. Circ Res (2007) 100(1):41–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000253900.66640.34

102. Dominguez G, Maddelein ML, Pucelle M, Nicaise Y, Maurage CA, Duyckaerts C, et al. Neuronal sphingosine kinase 2 subcellular localization is altered in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Acta Neuropathol Commun (2018) 6(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0527-z

103. Ceccom J, Loukh N, Lauwers-Cances V, Touriol C, Nicaise Y, Gentil C, et al. Reduced sphingosine kinase-1 and enhanced sphingosine 1-phosphate lyase expression demonstrate deregulated sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun (2014) 2(1):12. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-2-12

104. Moore AN, Kampfl AW, Zhao X, Hayes RL, Dash PK. Sphingosine-1-phosphate induces apoptosis of cultured hippocampal neurons that requires protein phosphatases and activator protein-1 complexes. Neuroscience (1999) 94(2):405–15. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00288-2

105. Alam S, Piazzesi A, Abd El Fatah M, Raucamp M, van Echten-Deckert G. Neurodegeneration Caused by S1P-Lyase Deficiency Involves Calcium-Dependent Tau Pathology and Abnormal Histone Acetylation. Cells (2020) 9(10):2189. doi: 10.3390/cells9102189

106. Ibáñez C, Simó C, Barupal DK, Fiehn O, Kivipelto M, Cedazo-Mínguez A, et al. A new metabolomic workflow for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. J Chromatogr A (2013) 1302:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.06.005

107. Couttas TA, Kain N, Tran C, Chatterton Z, Kwok JB, Don AS. Age-Dependent Changes to Sphingolipid Balance in the Human Hippocampus are Gender-Specific and May Sensitize to Neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis (2018) 63(2):503–14. doi: 10.3233/JAD-171054

108. Zhong L, Jiang X, Zhu Z, Qin H, Dinkins MB, Kong JN, et al. Lipid transporter Spns2 promotes microglia pro-inflammatory activation in response to amyloid-beta peptide. Glia (2019) 67(3):498–511. doi: 10.1002/glia.23558

109. O’Sullivan SA, O’Sullivan C, Healy LM, Dev KK, Sheridan GK. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors regulate TLR4-induced CXCL5 release from astrocytes and microglia. J Neurochem (2018) 144(6):736–47. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14313

110. Fischer I, Alliod C, Martinier N, Newcombe J, Brana C, Pouly S. Sphingosine kinase 1 and sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 3 are functionally upregulated on astrocytes under pro-inflammatory conditions. PloS One (2011) 6(8):e23905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023905

111. Fassbender K, Walter S, Kühl S, Landmann R, Ishii K, Bertsch T, et al. The LPS receptor (CD14) links innate immunity with Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J (2004) 18(1):203–5. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0364fje

112. Walter S, Letiembre M, Liu Y, Heine H, Penke B, Hao W, et al. Role of the toll-like receptor 4 in neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Physiol Biochem (2007) 20(6):947–56. doi: 10.1159/000110455

113. Bogie JFJ, Haidar M, Kooij G, Hendriks JJA. Fatty acid metabolism in the progression and resolution of CNS disorders. Adv Drug Deliv Rev (2020) 159:198–213. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.01.004

114. Serhan CN. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature (2014) 510:92–101. doi: 10.1038/nature13479

115. Shang P, Zhang Y, Ma D, Hao Y, Wang X, Xin M, et al. Inflammation resolution and specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators in CNS diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets (2019) 23:967–86. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2019.1691525

116. Chiurchiù V, Leuti A, Maccarrone M. Bioactive lipids and chronic inflammation: Managing the fire within. Front Immunol (2018) 9:38. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00038

117. Levy BD, Clish CB, Schmidt B, Gronert K, Serhan CN. Lipid mediator class switching during acute inflammation: Signals in resolution. Nat Immunol (2001) 2(7):612–9. doi: 10.1038/89759

118. Luo M, Jones SM, Phare SM, Coffey MJ, Peters-Golden M, Brock TG. Protein kinase a inhibits leukotriene synthesis by phosphorylation of 5-lipoxygenase on serine 523. J Biol Chem (2004) 279(40):41512–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312568200

119. Norris PC, Gosselin D, Reichart D, Glass CK, Dennis EA. Phospholipase A2 regulates eicosanoid class switching during inflammasome activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2014) 111(35):12746–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404372111

120. Serhan CN. Lipoxin biosynthesis and its impact in inflammatory and vascular events. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)/Lipids Lipid Metab (1994) 1212:1–25. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)90185-6

121. Konkel A, Schunck WH. Role of cytochrome P450 enzymes in the bioactivation of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochim Biophys Acta - Proteins Proteomics (2011) 1814:210–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.09.009

122. Dalli J, Serhan CN. Specific lipid mediator signatures of human phagocytes: Microparticles stimulate macrophage efferocytosis and pro-resolving mediators. Blood (2012) 120(15):e60–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-423525

123. Chiurchiù V, Leuti A, Dalli J, Jacobsson A, Battistini L, MaCcarrone M, et al. Proresolving lipid mediators resolvin D1, resolvin D2, and maresin 1 are critical in modulating T cell responses. Sci Transl Med (2016) 8(353):353ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf7483

124. Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: Dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol (2008) 8:349–61. doi: 10.1038/nri2294

125. Wang X, Zhu M, Hjorth E, Cortés-Toro V, Eyjolfsdottir H, Graff C, et al. Resolution of inflammation is altered in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (2015) 11(1):40–50.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.12.024

126. Salem N, Vandal M, Calon F. The benefit of docosahexaenoic acid for the adult brain in aging and dementia. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fat Acids (2015) 92:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2014.10.003

127. Medeiros R, Kitazawa M, Passos GF, Baglietto-Vargas D, Cheng D, Cribbs DH, et al. Aspirin-triggered lipoxin A4 stimulates alternative activation of microglia and reduces alzheimer disease-like pathology in mice. Am J Pathol (2013) 182(5):1780–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.051

128. Ikonomovic MD, Abrahamson EE, Uz T, Manev H, DeKosky ST. Increased 5-lipoxygenase immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Histochem Cytochem (2008) 56(12):1065–73. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.951855

129. Praticò D, Zhukareva V, Yao Y, Uryu K, Funk CD, Lawson JA, et al. 12/15-Lipoxygenase Is Increased in Alzheimer’s Disease: Possible Involvement in Brain Oxidative Stress. Am J Pathol (2004) 164(5):1655–62. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63724-8

130. Dunn HC, Ager RR, Baglietto-Vargas D, Cheng D, Kitazawa M, Cribbs DH, et al. Restoration of lipoxin A4 signaling reduces Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology in the 3xTg-AD mouse model. J Alzheimers Dis (2015) 43(3):893–903. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141335

131. Mizwicki MT, Liu G, Fiala M, Magpantay L, Sayre J, Siani A, et al. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and resolvin D1 retune the balance between amyloid-β phagocytosis and inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis (2013) 34(1):155–70. doi: 10.3233/JAD-121735

132. Zhu M, Wang X, Hjorth E, Colas RA, Schroeder L, Granholm AC, et al. Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators Improve Neuronal Survival and Increase Aβ42 Phagocytosis. Mol Neurobiol (2016) 53(4):2733–49. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9544-0

133. Lee JY, Han SH, Park MH, Baek B, Song IS, Choi MK, et al. Neuronal SphK1 acetylates COX2 and contributes to pathogenesis in a model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):1479. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03674-2

134. Lee JY, Han SH, Park MH, Song IS, Choi MK, Yu E, et al. N-AS-triggered SPMs are direct regulators of microglia in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun (2020) 11(1):2358. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16080-4

135. Doi Y, Takeuchi H, Horiuchi H, Hanyu T, Kawanokuchi J, Jin S, et al. Fingolimod Phosphate Attenuates Oligomeric Amyloid β-Induced Neurotoxicity via Increased Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Expression in Neurons. PloS One (2013) 8(4):e61988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061988

136. Aytan N, Choi JK, Carreras I, Brinkmann V, Kowall NW, Jenkins BG, et al. Fingolimod modulates multiple neuroinflammatory markers in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep (2016) 6:24939. doi: 10.1038/srep24939

137. Carreras I, Aytan N, Choi JK, Tognoni CM, Kowall NW, Jenkins BG, et al. Dual dose-dependent effects of fingolimod in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep (2019) 9(1):10972. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47287-1

138. McManus RM, Finucane OM, Wilk MM, Mills KHG, Lynch MA. FTY720 Attenuates Infection-Induced Enhancement of Aβ Accumulation in APP/PS1 Mice by Modulating Astrocytic Activation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol (2017) 12(4):670–81. doi: 10.1007/s11481-017-9753-6

139. Miller LG, Young JA, Ray SK, Wang G, Purohit S, Banik NL, et al. Sphingosine Toxicity in EAE and MS: Evidence for Ceramide Generation via Serine-Palmitoyltransferase Activation. Neurochem Res (2017) 42(10):2755–68. doi: 10.1007/s11064-017-2280-2

140. Šála M, Hollinger KR, Hollinger KR, Hollinger KR, Thomas AG, Dash RP, et al. Novel Human Neutral Sphingomyelinase 2 Inhibitors as Potential Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease. J Med Chem (2020) 63(11):6028–56. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00278

141. Figuera-Losada M, Stathis M, Dorskind JM, Thomas AG, Ratnam Bandaru VV, Yoo SW, et al. Cambinol, a novel inhibitor of neutral sphingomyelinase 2 shows neuroprotective properties. PloS One (2015) 10(5):e0124481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124481

142. Jeong SK, Il Kim Y, Shin KO, Kim BW, Lee SH, Jeon JE, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 activation enhances epidermal innate immunity through sphingosine-1-phosphate stimulation of cathelicidin production. J Dermatol Sci (2015) 79(3):229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.06.007

143. Woodling NS, Wang Q, Priyam PG, Larkin P, Shi J, Johansson JU, et al. Suppression of Alzheimer-associated inflammation by microglial prostaglandin-E2 EP4 receptor signaling. J Neurosci (2014) 34(17):5882–94. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0410-14.2014

144. He D, Zhang C, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Dai Q, Li Y, et al. Teriflunomide for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev (2016) 2016:CD009882. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009882.pub3

145. Ruiz A, Joshi P, Mastrangelo R, Francolini M, Verderio C, Matteoli M. Testing Aβ toxicity on primary CNS cultures using drug-screening microfluidic chips. Lab Chip (2014) 14(15):2860–6. doi: 10.1039/C4LC00174E