95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Immunol. , 08 January 2021

Sec. Viral Immunology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.601886

Fataneh Tavasolian1

Fataneh Tavasolian1 Mohsen Rashidi2

Mohsen Rashidi2 Gholam Reza Hatam3

Gholam Reza Hatam3 Marjan Jeddi4

Marjan Jeddi4 Ahmad Zavaran Hosseini5

Ahmad Zavaran Hosseini5 Sayed Hussain Mosawi6,7

Sayed Hussain Mosawi6,7 Elham Abdollahi8

Elham Abdollahi8 Robert D. Inman1,9*

Robert D. Inman1,9*The severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that appeared in December 2019 has precipitated the global pandemic Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). However, in many parts of Africa fewer than expected cases of COVID-19, with lower rates of mortality, have been reported. Individual human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles can affect both the susceptibility and the severity of viral infections. In the case of COVID-19 such an analysis may contribute to identifying individuals at higher risk of the disease and the epidemiological level to understanding the differences between countries in the epidemic patterns. It is also recognized that first antigen exposure influences the consequence of subsequent exposure. We thus propose a theory incorporating HLA antigens, the “original antigenic sin (OAS)” effect, and presentation of viral peptides which could explain with differential susceptibility or resistance to SARS-CoV-2 infections.

More than 190 countries have experienced a recent COVID-19 pandemic, especially China, South Korea, Italy, Iran, Spain, France, the United Kingdom, and growing numbers from the United States. However, Africa, with a population of >1.2 billion people, has had a comparatively low percentage of COVID-19 deaths, especially in the malaria-endemic region (1–6). There have been several hypotheses about such unexpected findings, including a relative lack of testing and documentation. The confirmation studies have suggested that most of these countries have close ties with China in terms of trade, migration, or commerce. All of these may play a role, yet it has also been proposed that several African nations more vigorously implemented public health policies than many other countries. Another consideration is that epidemic preparedness may be much higher, with prior experience with Ebola, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis (TB), etc. The strong burden of endemic infectious diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, and ongoing outbreaks of Lassa fever and Ebola in Nigeria and Congo, suggest an unpredictable and unusual response to COVID-19 (5, 7). This background illustrates the need to utilize a range of mitigation approaches even during the pandemic to establish a broad-based response. Our hypothesis emphasizes that HLA antigens and the OAS phenomenon could be important determinants for outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination (8, 9).

Coronaviruses are a category of respiratory viruses that can cause infections ranging from the common cold to Middle-East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). An increasing body of literature reveals that these coronaviruses are originally zoonotic, targeting the lower respiratory tract, and causing potentially lethal inflammation in extra-pulmonary organs (10). Within two decades, there have emerged three highly pathogenic and deadly human coronaviruses: SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 (11). What started as a novel outbreak of atypical viral pneumonia in December 2019 in Wuhan, China is now officially recognized as COVID-19, with the causative virus classified as SARS-CoV-2, which expresses a genomic homology of about 80% to SARS-CoV, and lesser homology (50%) with MERS-CoV. Researchers have discovered that cross-reactive antibodies react with, but do not confer cross-protection against, the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD) and non-RBD domains, nor is there cross-neutralization between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are uncommon (12–15).

SARS-CoV-2 is a single-strand RNA coronavirus composed of four main structural proteins: spike (S), envelope (E), nucleocapsid (N), and membrane (M) proteins that induce extreme respiratory disease and an aggressive pneumonia-like infection (16). Clinical studies have demonstrated that fever, exhaustion, dry cough, shortness of breath, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are predominant clinical manifestations. Several research studies have confirmed that the severity of the infection has been correlated with lymphopenia and the development of a cytokine storm (17).

In humans, the HLA system orchestrates immune regulation. The research effort, therefore, aims to identify the mechanisms that are potentially responsible for activating an immune response to SARS‐CoV‐2, including the role of HLA alleles in affected individuals (18). It is recognized that T-cell receptors recognize the conformational structure of the antigen binding-grove in the HLA molecule along with the accompanying antigen peptides. Thus, particular HLA haplotypes are associated with distinct genetic predispositions to disease (9, 19, 20). The repertoire of the HLA molecules composing a haplotype is thought to contribute to survival during evolution. As a result, it is advantageous to have enhanced binding capabilities of HLA molecules for viral peptides on the surface from novel viral infections, such as SARS-CoV-2, on the cell surface of antigen-presenting cells (9, 20–22).

We speculate that population HLA variability in a population could be correlated with COVID-19 incidence since HLA plays such a crucial role in the immune response to pathogens and the development of infectious diseases. The HLA system affects clinical outcomes in multiple infectious diseases, including HIV and SARS (23, 24). For the latter, population studies observed correlations between certain HLA alleles and the incidence and severity of SARS (24–26). HLA-B*07:03, B*46:01, DRB1*03:01, DRB1 *12:02 alleles were correlated with SARS susceptibility (27, 28). The SARS-CoV-2 sequence displays considerable homology with SARS, but the two viruses do have distinct variations (29). Therefore, it will require further investigation to incorporate HLA alleles when analyzing COVID-19 outcomes (27, 30, 31). The SARS-related susceptibility alleles were not shown to occur in COVID-19 patients at a significantly different level after p-value correction in the analysis performed by Wei Wang et al. in May 2020 (32).

Host genetic variability may help explain the multiplicity of immune responses to a virus within a community. Knowing how variability in HLA can impact the progression of COVID-19, in particular, may help distinguish individuals at higher risk for the disease.

In a study conducted by Benlyamani et al. in critically ill patients, results indicate downregulation of HLA-DR molecules in circulating monocytes, which, based on profound lymphopenia and other functional differences, create immunosuppressed conditions for host response (33).

An in silico analysis of viral peptide-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I binding affinity was conducted by Nguyen et al, which revealed that HLA-A*02:02, HLA-B*15:03, and HLA-C*12:03 effectively presented a larger amount of peptides whereas A*25:01, B*46:01, C*01:02 were the least efficient for of SARS-CoV-2 peptide presentation (30). Iturrieta-Zuazo et al. indicate that Class I HLA molecules with a better theoretical capacity to bind SARS-CoV-2 peptides were found in patients with mild disease and showed higher heterozygosity as compared with moderate and severe disease (34).

Thus the genetic variability of the MHC molecules can affect the susceptibility and severity of SARS-CoV-2 (35). One potential genetic contributor to the lower incidence of SARS-CoV-2 in Africa may be the occurrence of different HLA alleles in Africa compared to other regions. HLA alleles, particularly MHCI, are major elements of the presentation system for viral antigens and have been shown to impart differential viral resistance and disease intensity. Specific HLA genotypes can stimulate the T cell-mediated anti-viral response differently and could possibly alter the symptoms and transmission of the disease (36). HLA-B*46:01 is expected to have the fewest possible binding peptides for SARS-CoV-2, indicating that individuals with this allele could be especially vulnerable to COVID-19, as had previously been seen for SARS. HLA-B*15:03, on the other hand, demonstrated the greatest ability to present highly conserved SARS-CoV-2 peptides shared among common human coronaviruses, indicating that this allele may allow cross-protective T-cell dependent immunity (30). This is a more intriguing mechanism, as HLA-B*1503 appears to be prevalent in West Africa and most countries with high endemic malaria in the World Health Organization(WHO) African Region (37).

The HLA-viral interaction is complex. While HLA-B27 seems to confer relative resistance to Hepatitis C virus(HCV) and HIV (38, 39), it may confer susceptibility to malaria (40), since in Africa HLA-B27 prevalence seems to decrease in malaria-endemic populations. This could be related to the hypothesis of HLA-mediated host peptide presentation since serious COVID-19 disease is particularly unusual in malaria-endemic populations. In particular, a substantial correlation for HLA‐DRB1*15:01, ‐DQB1*06:02, and ‐B*27:07 was observed in research conducted Novelli et al. in a group of 99 Italian patients affected by a severe or extremely severe course of COVID‐19, although considering the limited sample size, there is a chance of false-positive detection (41). In the case of influenza, A (flu), HLA-B27-related immunodominance is endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase (ERAP-1)-dependent. This is not the case for HLA-B7 immunodominance the epitope of the HLA-B27 immunodominant influenza nucleoprotein (NP) 383–391 is formed as a 14-mer N-terminally stretched until ERAP-1 trims it. In flu-infected B27/ERAP-/- mice, the CD8+ T cell reaction to the B27/NP383–391 epitope is significantly reduced in the absence of ERAP1 As the correlation between ERAP-1 and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is seen exclusively in HLA-B27+ patients, it appears that creating the B27-related immunodominant peptide of the flu virus depends on ERAP-1, but this is not the case for HLA B-7 (42). Whether this ERAP-HLA interaction is applied to coronaviruses as well is unknown. Currently, we have limited data on whether B27+ AS patients are more, or less, susceptible to COVID-19 (43).

Coronaviruses belong to the family Coronaviradae, order Nidovirales, that can be further categorized into four major lines (α-, β-, π-, and δ-coronaviruses). Several α- and β-coronaviruses induce mild respiratory infections and common cold symptoms in humans, while some are zoonotic and infect birds, pigs, bats, and other animals. Similar to SARS-CoV-2, two other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV, also caused large disease outbreaks with high mortality levels (10%–30%) and substantial social effects. Comparison of the SARS-CoV-2 protein sequence with the sequences SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and bat-SL-CoVZXC21 revealed a high degree of homology between SARS-CoV-2, bat-SL-CoVZXC21, and SARS-CoV, but with a more restricted similarity to MERS-CoV. Grifoni et al. proposed that SARS-CoV-2 may be potentially interpreted as the inevitable outcome of an antigenic shift from SARS-CoV since these viruses share around 80% of their genome and almost all the encoded proteins (14).

Identifying how pre-existing immunity may dictate the development of antibodies to conserved SARS virus epitopes is important for the creation of new SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccines. Two features that have been found during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic demand attention. First, the lack of clinical symptoms of infection in children (16, 44), Secondly, the early onset of IgG in serum (45, 46). From the viewpoint of the host immune response, such an early increase of specific IgG is thought to represent a secondary immune response when the memory of a cross-reactive antigen is present, as may occur from an earlier coronaviral infection.

The key question then emerges whether or not such cross-reactive antibodies defend against the new virus. The worst-case scenario would be for such cross-reactive memory antibodies against similar coronaviruses not only to be non-protective but also to intensify infection (47). A significant discovery, however, is that cross-reactivity in antibody binding to spike proteins in SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV infections is widely observed, suggesting that antibodies to conserved spike antigens are common. Cross-neutralization of the virus species is however an uncommon phenomenon (12). In a study conducted by Ju et al. the anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and the convalescent plasma did not cross-react with the RBD of the viral spike protein of SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV, although there was substantial cross-reactivity to their trimeric spike proteins (48). But the plasma antibodies did cross-reaction with antigens in the SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV spikes, which did not result in virus neutralization (47, 48).

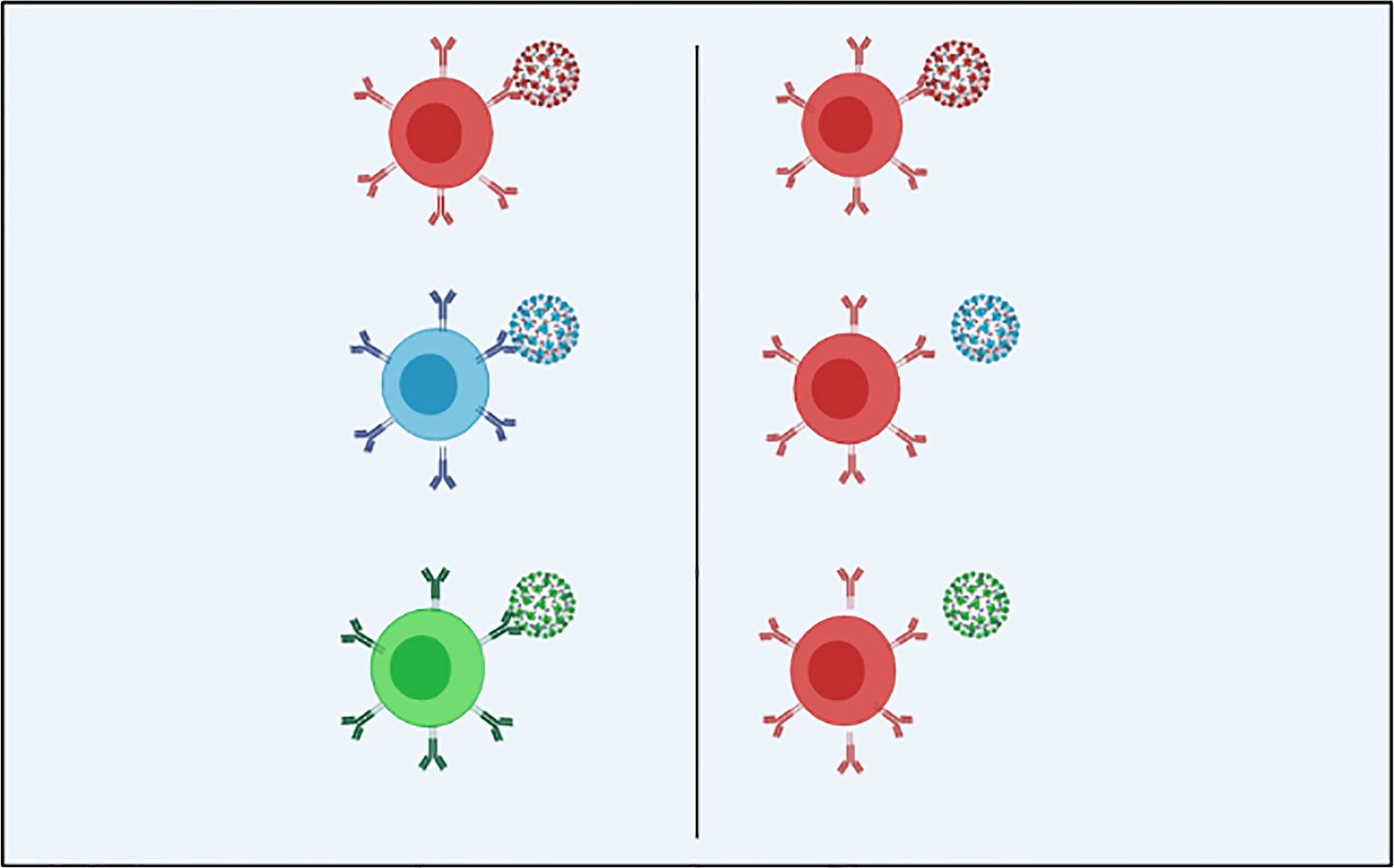

Original antigenic sin (OAS) refers to the activation of a more vigorous immune reaction to the priming vs an immunogenic boost that itself attaches poorly, if at all, to antibodies s caused by the priming immunogen (Figure 1) (8, 49, 50). MHC diversity could be a contributor in humans for such an event (30).

Figure 1 In the optimal immune response (on the left) against SARS-CoV-2 and its antigenic variants, the particular adaptive immunity is often associated with (color matching) the symbolic antibody and the spike proteins that cover the outer surface of the virion; Original antigenic sin explains the propensity of the immune response to use immunological memory that relies on the previous infection when a new slightly altered strain of the foreign pathogen is identified. As we see in the OAS model (right), the particular adaptive immune response is only installed against the original virus and is not used to combat the mutated forms of the virus, leading to a less specific and less efficient maladaptive response (Created in BioRender.com) (8).

Long-lived B memory cells, which persist in the body, develop during primary infection, and protect against subsequent infection. To produce antigen-specific antibodies, these memory B cells respond to particular epitopes on the surface of viral proteins and are capable of responding to infection faster than B cells react to novel antigens. This effect reduces the time it takes for subsequent infections to be resolved (51, 52).

A virus may demonstrate antigenic drift following primary and secondary infections, in which the viral epitopes are reshaped by natural mutation, enabling the virus to evade the immune system. When this occurs, the modified virus preferentially reactivates previously activated B memory cells of high affinity and stimulates the production of antibodies. Such antibodies may prevent the recruitment of higher affinity naive B cells that could generate more effective antibodies against the second viral challenge. This contributes to a less efficient immune response since it can take longer to clear recurrent infections. For the development and implementation of vaccines, OAS is of particular interest. The actual impact of OAS in dengue fever has important consequences for vaccine research. Whenever a response has developed to a dengue virus serotype, vaccination to a second serotype is unlikely to be successful, meaning that balanced reactions to all four virus serotypes should be developed in the initial formulation of the vaccine (53). However, in 2015 a new category of highly effective neutralizing antibodies was isolated, which were efficient against those four virus serotypes, boosting hope for the development of a universal dengue vaccine. In people that are regularly immunized, either by vaccinations or chronic infections, the specificity and efficiency of the immune response to new influenza strains are sometimes reduced (54). The effect of antigenic sin on protection, however, has not been well characterized and seems to vary for each vaccine with the particular pathogen, geographical region, and age.

A similar pattern in CTLs is implicated in host immunity. With a second infection by another type of dengue virus, it has been seen that the CTLs tend to produce cytokines rather than inducing target cell lysis. As a consequence, the production of these cytokines is suggested to enhance vascular permeability and the destruction of endothelial cells is intensified (55).

Many researchers have attempted to formulate HIV and HCV vaccines based on the induction of host CTL response. The observation that original antigenic sin can distort the CTL response can shed light on understanding the restricted efficacy of such vaccinations. Viruses such as HIV are extremely variable and regularly undergo mutation. In such circumstances, a vaccine may fail to control HIV infection if the virus expresses slightly different epitopes compared to those in the viral vaccine due to original antigenic sin. In theory, the vaccine could exacerbate the infection by “trapping” the immune response into the initial, inefficient response to the virus (56).

Thus, an inadequate immune response to the mutated virus due to the OAS may generate a significant number of sub-neutralizing cross-reactive antibodies that enhance inflammation and may paradoxically promote virus entry into host cells (8). The intracellular presence of the pathogen activates a pyroptosis mechanism with the subsequent release of danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) to trigger additional inflammatory cells, which in response release a great number of cytokines; which may be the basis of the “cytokine storm” identified in severe cases of COVID-19 (17, 57).

Consequentially, the OAS phenomenon can be both advantageous and detrimental to host defense. Perhaps the biggest influence of both the risks and benefits of OAS is an ever-present threat from strongly pathogenic strains of zoonotic viruses with pandemic potential. These are new pathogens for humans and it can be dangerous for any individual who does not have an element of pre-existing cross-protective immunity once a strain of this type appears. However, imprinting with a strain from the same group of phylogenies may protect against serious infection. Both the H1N1 pandemics of 1918 and 2009 have been accelerated by the reduced vulnerability of aging populations to cross-protection from antibodies generated to strains throughout childhood (58, 59). Also, heterosubtypic defense against highly pathogenic avian strains may rely on the year of birth, and hence the dominant strain during early life (60). This raises the possibility of a degree of protective immunity conferred by SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV-specific antibodies to decrease the susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 in Africa by the higher prevalence of HLA-B*15:03, which has the highest strength to present strongly conserved SARS-CoV-2 peptides shared by common human coronaviruses. Resolving this interaction may allow cross-protective T cell immunity to be derived (8, 61).

These correlations were also found between immunodominant sequences [N protein from SARS-CoV-2/SARS-CoV and thrombospondin-anonymous-related protein (TRAP) from P. falciparum] and [S protein-SARS-CoV-2/SARS-CoV and predicted epitope in sporozoite surface protein -2 (SSP-2) from P. falciparum]. Individually, both epitopes could induce the response of CD8+ CTL by HLA-A*02:01 presentation (1, 2). Lesa et al. presumed that the memory of adaptive immunity elevated against the described TRAP immunodominant epitope could recognize peptide-HLA-A*02:01 complexes originating from SARS-CoV-2 infection in malaria-endemic regions, particularly in Africa, and modify the host immune system response. Of course, such an assumption needs further empirical testing to prove its validity and ascertain the strength of the primed response (1).

The creation of an efficient subunit vaccine seems to be rather challenging in the presence of OAS and the potential adaptive mutation of SARS-CoV-2. Thus, an attractive option is to concentrate on an alternative method of vaccination that is capable of stimulating innate immunity instead of adaptive immunity. In children, where the immune system is immature and susceptible to challenge with new antigenic stimuli, innate immunity may be more effective, while adaptive immunity may play are larger role in the mature immune response in adults. This may relate to the observation that children rarely suffer fatal complications during the current COVID-19 pandemic (8, 62).

One of the representative processes of immune evasion of pathogens is to mask or alter pathogen molecules which are usually recognized by innate pattern recognition receptors. When developing vaccines against infectious agents, there is also a need to focus an immune response towards a particular conformational epitope (63). The approach is to develop vaccines that can provide epitope-specific immunofocusing and induce antibodies specifically targeting epitope (64). A specific monoclonal antibody could be used to shield the target epitope on the protein. The remaining uncovered surface proteins would then be altered to make them non-immunogenic. The epitope is eventually unprotected by eliminating the monoclonal antibody (64). The conserved immunodominant regions from Coronaviruses have implications for vaccine design against SARS-CoV-2 because of the OAS phenomenon. Research strategies must seek to maximize antibodies to conserved epitopes and induce broadly protective immunity against multiple strains. By utilizing an adjuvant vaccine, an increased cellular reaction will yield enhanced host protection benefits (65).

The clinical course of infection with SARS-CoV-2 is strongly dependent on the relationship between the virus and the host immune system, in which the host HLA plays a central role in the activation and regulation of the immune response. There is scope for further study into the role of HLA in COVID-19, and epidemiological studies need to focus on HLA profiles as host immune determinants. Such studies should include HLA typing of COVID-19 patients, both to unravel the complexity of the disease response and also to inform customized therapies. In addition, a prior history of coronavirus infection in the patient can be relevant to the magnitude of the immune response to the current SARS-CoV-2 infection, a phenomenon referred to as “original antigenic sin”. This concept refers to cross-reacting immunity due to past infections of similar coronavirus strains, which must be considered in interpreting immune responses to infections and vaccinations.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; HLA, Human Leukocyte Antigen; OAS, Original Antigenic Sin; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; TB, Tuberculosis; MERS, Middle-East respiratory syndrome; SARS, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; S, spike; E, envelope; N, nucleocapsid; M, membrane; ARDS, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome; WHO, World Health Organization; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; Flu, influenza A; ERAP, Endoplasmic Reticulum Aminopeptidase; NP, nucleoprotein; AS, Ankylosing Spondylitis; RBD, Receptor-Binding Domain; MHC, Major Histocompatibility Complex; CTL, cytotoxic T cells; DAMPs, Danger-Associated Molecular Patterns; TRAP, Thrombospondin-Anonymous-Related Protein; SSP-2, Sporozoite Surface Protein -2.

1. Iesa MA, Osman ME, Hassan MA, Dirar AI, Abuzeid N, Mancuso JJ, et al. SARS-COV2 and P. falciparum common immunodominant regions may explain low COVID-19 incidence in the malaria-endemic belt. New Microbes New Infect (2020) 38:100817. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100817

2. Nghochuzie NN, Olwal CO, Udoakang AJ, Amenga-Etego LN-K, Amambua-Ngwa A. Pausing the Fight Against Malaria to Combat the COVID-19 Pandemic in Africa: Is the Future of Malaria Bleak? Front Microbiol (2020) 11:1476. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01476

3. Rogerson SJ, Beeson JG, Laman M, Poespoprodjo JR, William T, Simpson JA, et al. Identifying and combating the impacts of COVID-19 on malaria. BMC Med (2020) 18(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01710-x

4. Sherrard-Smith E, Hogan AB, Hamlet A, Watson OJ, Whittaker C, Winskill P, et al. The potential public health consequences of COVID-19 on malaria in Africa. Nat Med (2020) 26(9):1411–6. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1025-y

5. Kobia F, Gitaka J. COVID-19: Are Africa’s diagnostic challenges blunting response effectiveness? AAS Open Res (2020) 3. doi: 10.12688/aasopenres.13061.1

6. Wang J, Xu C, Wong YK, He Y, Adegnika AA, Kremsner PG, et al. Preparedness is essential for malaria-endemic regions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet (2020) 395(10230):1094–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30561-4

7. Napoli PE, Nioi M. Global spread of coronavirus disease 2019 and malaria: an epidemiological paradox in the early stage of A pandemic. J Clin Med (2020) 9(4):1138. doi: 10.3390/jcm9041138

8. Roncati L, Palmieri B. What about the original antigenic sin of the humans versus SARS-CoV-2? Med Hypotheses (2020) 142:109824. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109824

9. Shi Y, Wang Y, Shao C, Huang J, Gan J, Huang X, et al. COVID-19 infection: the perspectives on immune responses. Cell Death Differ (2020) 27(5):1451–4. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-0530-3

10. Wu Y-C, Chen C-S, Chan Y-J. The outbreak of COVID-19: An overview. J Chin Med Assoc (2020) 83(3):217. doi: 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000270

11. Zhu Z, Lian X, Su X, Wu W, Marraro GA, Zeng Y. From SARS and MERS to COVID-19: a brief summary and comparison of severe acute respiratory infections caused by three highly pathogenic human coronaviruses. Respir Res (2020) 21(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01479-w

12. Lv H, Wu NC, Tsang OT-Y, Yuan M, Perera RA, Leung WS, et al. Cross-reactive antibody response between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV infections. Cell Rep (2020) 107725. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.15.993097

13. Yang R, Lan J, Huang B, Ruhan A, Lu M, Wang W, et al. Lack of antibody-mediated cross-protection between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV infections. EBioMedicine (2020) 58:102890. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102890

14. Grifoni A, Sidney J, Zhang Y, Scheuermann RH, Peters B, Sette A. A sequence homology and bioinformatic approach can predict candidate targets for immune responses to SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe (2020) 27(4):671–80.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.03.002

15. Ma Z, Li P, Ikram A, Pan Q. Does Cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Only Relate to High Pathogenic Coronaviruses? Trends Immunol (2020) 41(10):851–3. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.08.002

16. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med (2020) 382:1199–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316

17. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet (2020) 395(10229):1033. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0

18. Barquera R, Collen E, Di D, Buhler S, Teixeira J, Llamas B, et al. Binding affinities of 438 HLA proteins to complete proteomes of seven pandemic viruses and distributions of strongest and weakest HLA peptide binders in populations worldwide. HLA (2020) 96(3):277–98. doi: 10.1111/tan.13956

19. Lee CH, Koohy HJF. In silico identification of vaccine targets for 2019-nCoV. F1000Research (2020) 9. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.22507.2

20. Dutta M, Dutta P, Medhi S, Borkakoty B, Biswas D. Polymorphism of HLA class I and class II alleles in influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 virus infected population of Assam, Northeast India. J Med Virol (2018) 90(5):854–60. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25018

21. Horton R, Wilming L, Rand V, Lovering RC, Bruford EA, Khodiyar VK, et al. Gene map of the extended human MHC. Nat Rev Genet (2004) 5(12):889–99. doi: 10.1038/nrg1489

22. Wieczorek M, Abualrous ET, Sticht J, Álvaro-Benito M, Stolzenberg S, Noé F, et al. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II proteins: conformational plasticity in antigen presentation. Front Immunol (2017) 8:292. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00292

23. Bardeskar N, Mania-Pramanik J. HIV and host immunogenetics: unraveling the role of HLA-C. HLA (2016) 88(5):221–31. doi: 10.1111/tan.12882

24. Lin M, Tseng H-K, Trejaut JA, Lee H-L, Loo J-H, Chu C-C, et al. Association of HLA class I with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. BMC Med Genet (2003) 4(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-4-9

25. Wang S-F, Chen K-H, Chen M, Li W-Y, Chen Y-J, Tsao C-H, et al. Human-leukocyte antigen class I Cw 1502 and class II DR 0301 genotypes are associated with resistance to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) infection. Viral Immunol (2011) 24(5):421–6. doi: 10.1089/vim.2011.0024

26. Chen Y-MA, Liang S-Y, Shih Y-P, Chen C-Y, Lee Y-M, Chang L, et al. Epidemiological and genetic correlates of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in the hospital with the highest nosocomial infection rate in Taiwan in 2003. J Clin Microbiol (2006) 44(2):359–65. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.359-365.2006

27. Sanchez-Mazas A. HLA studies in the context of coronavirus outbreaks. Swiss Med Wkly (2020) 150(1516). doi: 10.4414/smw.2020.20248

28. Ng MH, Lau K-M, Li L, Cheng S-H, Chan WY, Hui PK, et al. Association of human-leukocyte-antigen class I (B* 0703) and class II (DRB1* 0301) genotypes with susceptibility and resistance to the development of severe acute respiratory syndrome. J Infect Dis (2004) 190: (3):515–8. doi: 10.1086/421523

29. Xu J, Zhao S, Teng T, Abdalla AE, Zhu W, Xie L, et al. Systematic comparison of two animal-to-human transmitted human coronaviruses: SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Viruses (2020) 12(2):244. doi: 10.3390/v12020244

30. Nguyen A, David JK, Maden SK, Wood MA, Weeder BR, Nellore A, et al. Human leukocyte antigen susceptibility map for SARS-CoV-2. J Virol (2020) 332:498–510. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.11.038

31. The Severe Covid-19 GWAS Group. Genomewide association study of severe Covid-19 with respiratory failure. N Engl J Med (2020) 383(16):1522–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2020283

32. Wang W, Wei Z, Zhang J, He J, Zhu F. Distribution of HLA allele frequencies in 82 Chinese individuals with coronavirus disease-2019. HLA (2020) 96(2):194–6. doi: 10.1111/tan.13941

33. Benlyamani I, Venet F, Coudereau R, Gossez M, Monneret G. Monocyte HLA-DR measurement by flow cytometry in COVID-19 patients: an interim review. Cytometry Part A (2020) 97(12):1217–21. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.24249

34. Iturrieta-Zuazo I, Rita CG, García-Soidán A, de Malet Pintos-Fonseca A, Alonso-Alarcón N, Pariente-Rodríguez R, et al. Possible role of HLA class-I genotype in SARS-CoV-2 infection and progression: A pilot study in a cohort of Covid-19 Spanish patients. Clin Immunol (2020) 219:108572. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108572

35. Romero-López J, Carnalla-Cortés M, Pacheco-Olvera D, Ocampo M, Oliva-Ramírez J, Moreno-Manjón J, et al. Prediction of SARS-CoV2 spike protein epitopes reveals HLA-associated susceptibility. Preprint Res Square (2020). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-25844/v1

36. C.-H. G. Initiative. The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, a global initiative to elucidate the role of host genetic factors in susceptibility and severity of the SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic. Eur J Hum Genet (2020) 28(6):715–8. doi: 10.1038/s41431-020-0636-6

37. Gonzalez-Galarza FF, McCabe A, Santos EJMD, Jones J, Takeshita L, Ortega-Rivera ND, et al. Allele frequency net database (AFND) 2020 update: gold-standard data classification, open access genotype data and new query tools. Nucleic Acids Res (2020) 48(D1):D783–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1029

38. Neumann-Haefelin C. HLA-B27-mediated protection in HIV and hepatitis C virus infection and pathogenesis in spondyloarthritis: two sides of the same coin? Curr Opin Rheumatol (2013) 25(4):426–33. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328362018f

39. Neumann-Haefelin C, McKiernan S, Ward S, Viazov S, Spangenberg HC, Killinger T, et al. Dominant influence of an HLA-B27 restricted CD8+ T cell response in mediating HCV clearance and evolution. Hepatology (2006) 43(3):563–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.21049

40. Mathieu A, Cauli A, Fiorillo MT, Sorrentino R. HLA-B27 and ankylosing spondylitis geographic distribution as the result of a genetic selection induced by malaria endemic? A review supporting the hypothesis. Autoimmun Rev (2008) 7(5):398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.03.013

41. Novelli A, Andreani M, Biancolella M, Liberatoscioli L, Passarelli C, Colona VL, et al. HLA allele frequencies and susceptibility to COVID-19 in a group of 99 Italian patients. HLA (2020) 96(5):610–4. doi: 10.1111/tan.14047

42. Akram A, Lin A, Gracey E, Streutker CJ, Inman RD. HLA-B27, but not HLA-B7, immunodominance to influenza is ERAP dependent. J Immunol (2014) 192(12):5520–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400343

43. Rosenbaum JT, Hamilton H, Weisman MH, Reveille JD, Winthrop KL, Choi D. The Effect of HLA-B27 on Susceptibility and Severity of COVID-19. J Rheumatol (2020) jrheum.200939. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.200939

44. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, Qi X, Jiang F, Jiang Z, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of 2143 pediatric patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in China. Pediatrics (2020) 145(6):e20200702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702

45. Long Q-X, Deng H-J, Chen J, Hu J, Liu B-Z, Liao P, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 patients: the perspective application of serological tests in clinical practice. medRxiv (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.03.18.20038018

46. Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, Liu W, Liao X, Su Y, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease. Clin Infect Dis (2020) 2019:2027–34. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3546052

47. Fierz W, Walz B. Antibody dependent enhancement due to original antigenic sin and the development of SARS. Front Immunol (2020) 11:1120. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01120

48. Ju B, Zhang Q, Ge J, Wang R, Sun J, Ge X, et al. Human neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature (2020) 584(7819):115–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2380-z

49. Mongkolsapaya J, Dejnirattisai W, Xu X-N, Vasanawathana S, Tangthawornchaikul N, Chairunsri A, et al. Original antigenic sin and apoptosis in the pathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Nat Med (2003) 9(7):921–7. doi: 10.1038/nm887

50. Yewdell JW, Santos JJS. Original Antigenic Sin: How Original? How Sinful? Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med (2020) a038786. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a038786

51. Fish S, Zenowich E, Fleming M, Manser T. Molecular analysis of original antigenic sin. I. Clonal selection, somatic mutation, and isotype switching during a memory B cell response. J Exp Med (1989) 170(4):1191–209. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1191

52. Tan Y-C, Blum LK, Kongpachith S, Ju C-H, Cai X, Lindstrom TM, et al. High-throughput sequencing of natively paired antibody chains provides evidence for original antigenic sin shaping the antibody response to influenza vaccination. Clin Immunol (2014) 151(1):55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.12.008

53. Midgley CM, Bajwa-Joseph M, Vasanawathana S, Limpitikul W, Wills B, Flanagan A, et al. An in-depth analysis of original antigenic sin in dengue virus infection. J Virol (2011) 85(1):410–21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01826-10

54. Dejnirattisai W, Wongwiwat W, Supasa S, Zhang X, Dai X, Rouvinski A, et al. A new class of highly potent, broadly neutralizing antibodies isolated from viremic patients infected with dengue virus. Nat Immunol (2015) 16(2):170. doi: 10.1038/ni.3058

55. Mongkolsapaya J, Duangchinda T, Dejnirattisai W, Vasanawathana S, Avirutnan P, Jairungsri A, et al. T cell responses in dengue hemorrhagic fever: are cross-reactive T cells suboptimal? J Immunol (2006) 176(6):3821–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3821

56. McMichael AJ. The original sin of killer T cells. Nature (1998) 394(6692):421–2. doi: 10.1038/28738

57. Tetro JA. Is COVID-19 receiving ADE from other coronaviruses? Microbes and Infect (2020) 22(2):72–3. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.02.006

58. Andrews SF, Huang Y, Kaur K, Popova LI, Ho IY, Pauli NT, et al. Immune history profoundly affects broadly protective B cell responses to influenza. Sci Trans Med (2015) 7(316):316ra192–316ra192. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad0522

59. Viboud C, Eisenstein J, Reid AH, Janczewski TA, Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. Age-and sex-specific mortality associated with the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic in Kentucky. J Infect Dis (2013) 207(5):721–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis745

60. Gostic KM, Ambrose M, Worobey M, Lloyd-Smith JO. Potent protection against H5N1 and H7N9 influenza via childhood hemagglutinin imprinting. Science (2016) 354(6313):722–6. doi: 10.1126/science.aag1322

61. Henry C, Palm A-KE, Krammer F, Wilson PC. From original antigenic sin to the universal influenza virus vaccine. Trends Immunol (2018) 39(1):70–9. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.08.003

62. Prompetchara E, Ketloy C, Palaga T. Immune responses in COVID-19 and potential vaccines: Lessons learned from SARS and MERS epidemic. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol (2020) 38(1):1–9. doi: 10.12932/AP-200220-0772

63. Zarnitsyna VI, Ellebedy AH, Davis C, Jacob J, Ahmed R, Antia R. Masking of antigenic epitopes by antibodies shapes the humoral immune response to influenza. J Immnol (2016) 196(1 Supplement):80.6. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0248

64. Weidenbacher PA, Kim PS. Protect, modify, deprotect (PMD): A strategy for creating vaccines to elicit antibodies targeting a specific epitope. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2019) 116(20):9947–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1822062116

Keywords: Coronavirus Disease 2019, human leukocyte antigens, original antigenic sin, immune response, vaccine design

Citation: Tavasolian F, Rashidi M, Hatam GR, Jeddi M, Hosseini AZ, Mosawi SH, Abdollahi E and Inman RD (2021) HLA, Immune Response, and Susceptibility to COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 11:601886. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.601886

Received: 01 September 2020; Accepted: 07 December 2020;

Published: 08 January 2021.

Edited by:

Ruchi Tiwari, U.P. Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Veterinary University, IndiaReviewed by:

Talha Bin Emran, Begum Gulchemonara Trust University, BangladeshCopyright © 2021 Tavasolian, Rashidi, Hatam, Jeddi, Hosseini, Mosawi, Abdollahi and Inman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Robert D. Inman, Um9iZXJ0LklubWFuQHVobi5jYQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.