95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Immunol. , 02 September 2020

Sec. Alloimmunity and Transplantation

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.02022

This article is part of the Research Topic The Immunotherapeutic Potential of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT) View all 10 articles

Fei Gao1,2,3

Fei Gao1,2,3 Yishan Ye1,2,3

Yishan Ye1,2,3 Yang Gao1,2,3

Yang Gao1,2,3 He Huang1,2,3*

He Huang1,2,3* Yanmin Zhao1,2,3*

Yanmin Zhao1,2,3*Natural killer (NK) cells play a significant role in immune tolerance and immune surveillance. Killer immunoglobin-like receptors (KIRs), which recognize human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I molecules, are particularly important for NK cell functions. Previous studies have suggested that, in the setting of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), alloreactive NK cells from the donor could efficiently eliminate recipient tumor cells and the residual immune cells. Subsequently, several clinical models were established to determine the optimal donors who would exhibit a graft-vs. -leukemia (GVL) effect without developing graft-vs. -host disease (GVHD). In addition, hypotheses about specific beneficial receptor-ligand pairs and KIR genes have been raised and the favorable effects of alloreactive NK cells are being investigated. Moreover, with a deeper understanding of the process of NK cell reconstitution post-HSCT, new factors involved in this process and the defects of previous models have been observed. In this review, we summarize the most relevant literatures about the impact of NK cell alloreactivity on transplant outcomes and the factors affecting NK cell reconstitution.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is an effective therapy for patients with hematological malignancies. However, relapse, graft-vs. -host disease (GVHD), and infections remain the main causes of treatment failure (1–4). Potential strategies to prevent GVHD and even infections while sparing the graft-vs. -leukemia (GVL) effect have attracted extensive attention. Natural killer (NK) cells, which are a major type of innate lymphocytes, are being researched in this context.

NK cells constitute 5–15% of human peripheral blood lymphocytes (5, 6) and possess the abilities of cytotoxic lysis and rapid cytokine secretion without prior antigen presentation (7, 8). These functions are regulated by various types of receptors expressed on NK cells manifesting multiple functions either activating or inhibitory (9–11) (Table 1). Among the NK cell receptors, the killer immunoglobin-like receptor (KIR) is one of the major factors that mediate self-tolerance and anti-tumor/infection responses.

It is well established that KIR genes are located on chromosome 19q13.4 (12). Based on their various structures (the number of extracellular immunoglobulin domains (D) and the long (L) or short (S) tails), 16 KIR genes (including two pseudogenes (P), KIR2DP1 and KIR3DP1) have been classified into four groups (KIR2DL1-5, KIR3DL1-3, KIR2DS1-5, and KIR3DS1). Six genes with short tails are activating KIR genes that encode activating receptors, while the eight genes with long tails are inhibitory KIR genes encoding inhibitory receptors. KIRs could be divided into haplotype A and B according to the activating genes on them. Haplotype A has only one activating gene, KIR2DS4, whereas haplotype B possesses up to five activating KIR genes, including KIR2DS1, 2, 3, 5, and 3DS1 (Figure 1). Thus, the A/A genotype is defined as homozygous for A haplotypes, and the B/x genotype consists of at least one B haplotype. Finally, according to the specific KIR gene locus on the chromosome, a centromeric (Cen) and telomeric (Tel) KIR haplotype and genotype are further determined (13–15). Five inhibitory and three activating KIRs recognize specific class I HLA (A, B, or C) ligands, with the inhibitory KIR2DL1 recognizes group 2 HLA-C alleles, KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 recognize group 1 HLA-C alleles, KIR3DL1 recognizes HLA-Bw4 alleles, and KIR3DL2 recognizes HLA-A3/-A11 alleles. Moreover, activating KIR2DS1, KIR2DS2, and KIR2DS4 recognize HLA-C2, C1, A11, respectively (15). The ligands of the remaining KIRs remain unknown.

Figure 1. Simplified genomic maps of KIR. Inhibitory KIR genes are color-coded in blue, activating KIR genes in orange, and pseudogenes in gray. KIR haplotype A has only one activating KIR gene: KIR2DS4, KIR B haplotype has fixable content of activating KIR genes. KIR haplotype could be further determined as Cen haplotype and Tel haplotype.

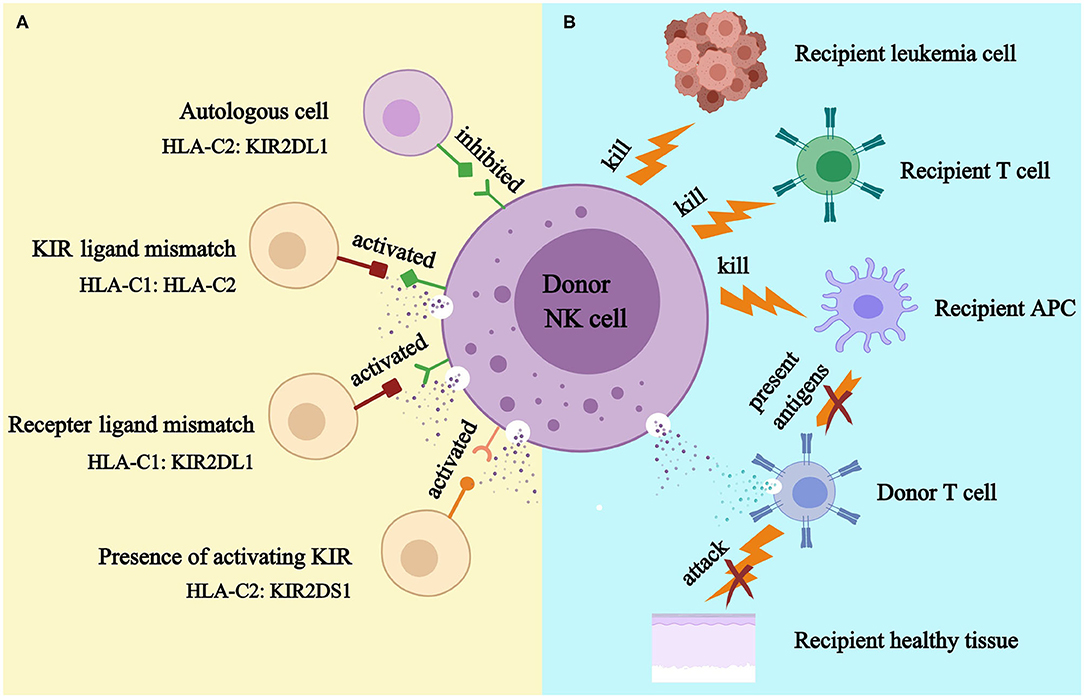

As KIR genes and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes are located on different chromosomes, autologous KIR receptor-ligand mismatch may exist (16). Normally, NK cells acquire self-tolerance and functional competence through the education process, in which inhibitory KIRs could be inhibited by self-HLA ligands and activated in a non-self HLA environment. Besides, the decreased responsiveness of activating KIRs in the presence of their cognate ligands also prevents autoimmunity (17–23) (Figure 2A). Importantly, infected and/or tumor cells may express inhibitory KIR ligands insufficiently or express activating ligands that may activate NK cells (24–31).

Figure 2. KIR models (A) and NK cell-mediated killing (B). APC, antigen presenting cell. (A). Donor NK cell is tolerant to self because donor inhibitory KIR is inhibited by its cognate HLA ligand; donor NK cell might kill recipient cell because HLA ligand for donor inhibitory KIR presents in donor but absents in recipient (KIR ligand model); donor NK cell could kill recipient cell because recipient HLA ligand does not inhibit donor inhibitory KIR (receptor ligand model); donor NK cell could kill recipient cell because donor activating KIR is activated by recipient (KIR B haplotypes and KIR B genes). (B). Alloreactive donor NK cell could kill recipient leukemia cell to prevent relapse; it could kill recipient T cell to prevent graft rejection; and it could kill recipient APC to prevent GVHD.

As the first reconstituted lymphocyte subset after transplantation (32, 33), NK cells play a critical role in controlling early relapse and infections. They also possess the ability to eliminate recipient T cells and antigen-presenting cells (APCs), to prevent graft failure and GVHD (34–38) (Figure 2B). Three models were established historically in an attempt to optimize donor selection for HSCT based on KIR (Figure 2A). The Perugia group in Italy firstly proposed the donor-recipient KIR ligand-ligand model (also known as KIR ligand model) solely based on the HLA phenotype of the donor and recipient. The KIR ligand incompatibility in the GVH direction was defined as the absence in recipients of donor class I allele group(s) recognized by KIRs. Those authors observed that the HLA haplotype-mismatched transplants reduced the rejection and relapse rate and prevented GVHD in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (36). Subsequently, the second model (named receptor-ligand model or missing ligand model) was raised by Leung et al. based on the compatibilities between the recipient HLA and donor inhibitory KIR. This model focused on donor KIR instead of donor HLA and could, therefore, be used in both HLA-matched and HLA-mismatched transplants. The results of that study suggested that the receptor-ligand model better predicted the risk of primary disease relapse, especially for lymphoid malignancies, compared with the ligand-ligand model (39). Subsequently, with a deeper understanding of KIR haplotypes, the third model analyzed and compared the KIR genotypes of different donors. Cooley et al. showed that unrelated donors with KIR-B haplotypes conferred a significant relapse-free survival (RFS) benefit to patients with AML undergoing T cell-replete HSCT (40). Based on the three models described above, numerous studies have been carried out to explore the impact of NK cell alloreactivity. Clinical results obtained from KIR ligand model, receptor ligand model and KIR haplotype and gene model were summarized in Tables 2–4, respectively. Nevertheless, the results were controversial, and several key questions remained regarding NK cell biology post-HSCT. What are the exact effects of NK cell alloreactivity on patients after HSCT? How do NK cells reconstitute post-HSCT and which factors may interfere with the reconstitution process? This review summarizes the latest literature on this important topic and offer some instructive hypothesis.

GVHD is an important complication of HSCT with high morbidity and mortality in which allogeneic donor immune cells are activated by APCs and then recognize and attack the host tissue (105). Removing donor T cells from grafts reduces the occurrence of GVHD, while it also elevates the risk of graft failure and disease relapse (106–108).

As another component of immune cells, previous murine studies suggested that adoptive transfer of interleukin-2 (IL-2)-activated SCID NK cells with donor bone marrow cells promoted engraftment in allogenic hosts with no signs of GVHD (109). Later, Asai et al. reported that hosts receiving MHC-incompatible bone marrow and spleen cells (as a source of T cells) rapidly succumbed to acute GVHD, while hosts who additionally received IL-2-activated donor NK cells on day 0 experienced a significant improvement in survival because of the lower incidence of severe GVHD. They further demonstrated that that the protective effect on GVHD was dependent on the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and could be abrogated by an anti-TGF-β antibody (35). Moreover, Ruggeri et al. showed that pre-transplant alloreactive Ly49 (Ly49 receptors recognize major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules in mice, which is analogous to KIR in humans) ligand-mismatched donor NK cell transfusion successfully eliminated host tumor cells and protected against GVHD by depleting host APCs. In contrast, hosts receiving bone marrow grafts without NK cell infusion died of GVHD, and non-alloreactive Ly49 ligand matched NK cell infusion did not provide protection against GVHD (36). Consistently, subsequent studies also found that donor alloreactive NK cells suppressed GVHD by inhibiting T cell proliferation and activation (37, 110). However, the protective role of NK cells in GVHD pathogenesis has also been challenged. Pre-clinical evidence from a xenogeneic model showed that an in vitro IL-2-activated human NK cell infusion promoted GVHD in SCID mice via the production of cytokines such as IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (111, 112). Accordingly, GVHD was inhibited after the administration of anti-IFN-γ and depletion of Poly I:C-activated NK cells in murine studies (113, 114).

In patients with hematological malignancies, a purified (115, 116) or cytokine-induced (117–121) donor NK cell transfusion was also well tolerated and seldom induced severe GVHD (grade III-IV acute GVHD or moderate-to-severe chronic GVHD). More recently, a pilot study suggested that, after haplo-HSCT, patients with refractory AML who received a donor NK cell infusion experienced a significantly lower grade II-IV GVHD than did those without NK cell infusion (122). In contrast, Shah et al. observed that patients who received a donor IL-15/4-1BBL-activated NK cell infusion after T cell-depleted (TCD) stem cell transplantation experienced a high risk of GVHD (123).

In addition to the technique of adoptive transfer, many studies have analyzed the effects of innate donor-recipient NK cell alloreactivity on GVHD in a clinical setting. The majority of studies did not report a significant association between these parameters (41–44, 46, 47, 50, 51, 54–56, 59, 65, 66, 79, 81, 83, 87–89, 91–93, 97, 98, 102, 104), while some reported a protective effect (70, 74, 76). Moreover, several studies found that KIR ligand mismatch or receptor-ligand mismatch increased the risk of GVHD (45, 57, 60, 64, 68, 80). Accordingly, two studies performed in China that applied the ‘Peking protocol’ for HSCT using the granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF)-mobilized graft containing a high dose of T cells observed promotive effects of NK cell alloreactivity on GVHD (48, 49).

It is not entirely clear why the reconstituted alloreactive NK cells were unable to prevent GVHD as the adoptively transferred NK cells. Studies have indicated that this discrepancy was probably attributable to the impaired function of early reconstituted NK cells. Shilling et al. first observed that a period of several months or even years was required for the recipient to reconstitute an NK cell repertoire resembling that of the donor (124). Vago et al. also suggested that the NK cells that were reconstituted early after transplantation were immature and exhibited compromised cytotoxicity (125). In addition, NK cell reconstitution is affected by graft composition. Patients receiving more T cells in grafts experience a faster T cell reconstitution (126, 127), while the absolute number of reconstituted NK cells and KIR expression are impaired by the co-grafted T cells (127–130). Other than NK cells, nearly 5% of CD8+ T cells, 0.2% of CD4+ T cells, and 10% of γδ T cells in the peripheral blood also express KIRs (131–133). Therefore, it is possible that the potential beneficial effects of alloreactive NK cells are overwhelmed by the strong alloreactive T cell response. In addition, it was observed that NK cells generated more IFN-γ in the presence of T cells in grafts, leading to a higher occurrence of acute GVHD (aGVHD) (130). Moreover, post-transplant immune suppression also exerted negative effects on NK cell reconstitution (134, 135).

Regarding specific genotypes, some studies have reported that KIR haplotype B donors afforded a significantly reduced risk of GVHD (60, 63, 86, 96). Consistent with these findings, Sivori et al. suggested that donor NK cells expressing KIR2DS1 were efficient in killing allogenic dendric cells in the setting of haplo-HSCT, thus leading to a better GVHD control (136). However, several studies also found that donors with KIR-B/x led to higher GVHD occurrence in recipients compared with donors with A/A, probably because of the more potent production of IFN-γ by alloreactive NK cells (40, 45, 76, 77, 94, 95).

Other factors, such as HLA mismatch, disease type, patient age, GVHD prophylaxis, and graft source, were also reported to interfere with GVHD occurrence in these studies (44, 45, 63, 66, 87, 92, 93, 104). Collectively, the manner in which the reconstituted NK cells affect the risk of GVHD remains largely unknown, and the relationships between NK and T cells during the initiation and process of GVHD warrant further investigation.

Infections are especially challenging for patients after HSCT because of the immunological derangement caused by multiple factors, including an intensive conditioning regimen, immunosuppressive agents, and other complications, such as GVHD (137, 138).

Several studies have reported that patients receiving KIR ligand-mismatched transplants are more vulnerable to infections. Schaffer et al. first reported that KIR ligand mismatch was associated with an increased infection-related mortality (43). Similarly, results from Zhao et al. showed that recipients from the KIR ligand-mismatched group experienced a significantly higher cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation rate. Moreover, the percentage of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)-expressing NK cells in the peripheral blood was significantly higher in the KIR ligand matched group 30 and 100 days post-HSCT compared with the KIR ligand-mismatched group (53). The higher level of IFN-γ secretion from the NK cells might trigger Th1 immune responses, antigen presentation cell activation, and macrophage killing (7, 8), leading to lower infection rate. While, KIR ligand mismatch may increase the risk of infection by eliminating recipient APCs by donor alloreactive NK cells (36).

Many studies have found that KIR-B genes protect patients with HSCT against infections and most of them were predominantly T cell replete (TCR) transplants (81, 84, 87, 96, 139, 140). Cook et al. first observed that KIR haplotype B donors exhibited a significant reduction in the rate of CMV reactivation in sibling allo-HSCT (139). Wu et al. and Zaia et al. reported that donors expressing higher numbers of activating KIRs were associated with a lower CMV reactivation rate (62, 84). Specifically, activating KIR2DS2 and KIR2DS4 may play a major protective role (84, 140). Importantly, transplantations from donors with KIR2DS1 correlated with better infectious control (51, 96). Mancusi et al. further demonstrated that the binding of KIR2DS1 to HLA-C2 triggered pro-inflammatory cytokine production by alloreactive NK cells (51). Moreover, without a cognate ligand (HLA-C1) in recipients, donor KIR2DS2 was associated with a higher CMV reactivation rate after HLA-identical sibling HSCTs (81). Apart from CMV reactivation, the incidence of bacterial infections was also reduced when patients had KIR-B/x donors (87). In contrast with previous results, KIR2DS2 gene and Cen-B/x donors related to a higher incidence of CMV reactivation and infection-related mortality in TCD transplants (53, 100). The reasons for these differing results may be due to the different graft composition. As previously described, NK cells generate more IFN-γ in TCR transplants, which may benefit the infection control (130). Of notice, the activating KIR targets outside of HLA are largely unknown, and these clinical observations still need to be confirmed by definitive functional analysis in the future.

Primary disease relapse remains the main obstacle that hampers the long-term survival of patients with hematological malignancies. Previous experience showed that adoptive transfer of autologous NK cell for patients with tumors was safe but inefficient (141–145), probably because autologous NK cells could not overcome the inhibition mediated by tumor cells expressing self-HLA. In contrast, allogenic (117), especially haploidentical, donor NK cell infusion demonstrated wide prospects in the salvage treatment (115, 120, 121) and prophylactic treatment (118, 119) of patients with hematological malignancies. In allo-HSCT, whether the reconstituted alloreactive NK cells prevent the disease relapse remains controversial.

In HLA-mismatched transplants, the Perugia group first observed that, in the context of T cell depletion, high stem cell dose, and absence of post-transplant immune suppression, KIR ligand mismatch reduced the risk of relapse and markedly improved survival in patients with AML, but not in those with acute lymphoblast leukemia (ALL) (36). This protective effect on relapse or survival was supported by many clinical studies (42, 44, 47, 51, 54), especially in myeloid disease (44, 47, 51) and transplants with TCD grafts (42, 47, 51, 54). However, conflicting results stemmed from many studies that failed to replicate these results (39, 46, 58, 102), and some even reached the opposite conclusions (41, 43, 45, 48, 50, 55).

Studies using the receptor-ligand model including HLA-matched donor-recipient pairs also reported conflicting results. Leung et al. first reported that the receptor-ligand model was more accurate than the KIR ligand model when predicting the risk of relapse, especially for lymphoid malignancies. Moreover, the potency of the relapse protection positively correlated with the number of receptor-ligand mismatch pairs (39). Subsequently, the protective effect of receptor-ligand mismatch has been confirmed by many investigations (58, 59, 66, 69, 71, 73, 76, 79, 80). Moreover, a survival advantage was also observed in patients with receptor-ligand mismatch compared with receptor-ligand matched pairs (59, 66, 69–71, 73, 76, 79). However, several other studies described opposite results (63, 64, 75, 77, 78). Of notice, two studies from Japan observed that the lack of the HLA-C2 ligand for donor inhibitory KIR afforded relapse protection in patients with AML and chronic myeloid leukemia, but increased the relapse rate in patients with ALL (73, 75). To date, no plausible explanation has been put forward for this disparity in relapse.

In contrast to the controversial results described above, transplantations from KIR haplotype B donors achieved greater agreement. Cooley et al. observed that patients with AML with KIR-B/x donors experienced a 30% improvement in RFS compared with those with A/A donors (40). Subsequently, many further investigations confirmed this beneficial effect of the KIR-B haplotype on relapse and survival in patients with hematological malignancies (50, 51, 57, 67, 72, 76, 79, 81, 85, 88–92, 96, 98, 101–104). Five of these studies reported that the protection effects mainly existed in the KIR Cen-B locus (67, 88, 91, 92, 96). Babor et al. further suggested that the presence of Cen-B with absence of Tel-B improved leukemia control in pediatric patients with ALL (97). At the genetic level, the KIR2DS2 gene, which is located on the Cen-B motif (72, 76, 79, 90, 92, 96), and the KIR2DS1 gene, located on the Tel-B motif (51, 72, 82, 98), were found to be related to a decreased relapse rate or an improved survival. However, several studies found that Cen-B donors indicated a lower OS (56, 70, 100). Meanwhile, Verneris et al. did not find any association between transplant outcomes and NK cell alloreactivity or KIR gene content in pediatric patients with acute leukemia (46).

Recently, Krieger et al. developed a scoring system, in which interactions of multiple KIR genes and HLA ligands were quantitatively analyzed. This comprehensive method raised an improved strategy to select a donor and exhibited great potential in the future (146).

Collectively, it is still controversial to determine an optimal donor who exhibits the best NK cell function using the three established KIR models. A better knowledge of NK cell reconstitution after HSCT may promote a better understanding of how NK cells affect the transplant outcomes in these patients. More in-depth studies focusing on “functional changes in NK cells” rather than “match or mismatch” may help us get closer to an optimal donor.

NK cells are derived from the CD34+ hematopoietic stem and precursor cells in the bone marrow, which then migrate to the periphery (147). Recent evidence suggested that not only the bone marrow, but also secondary lymphoid tissues contribute to the development of NK cells (148). According to the surface expression of CD56, NK cells could be divided in two main subtypes: CD56bright and CD56dim NK cells. CD56bright NK cells exist mainly in lymph nodes and tonsils, while CD56dim NK cells, the more mature subset transformed from CD56bright NK cells, are dominant in the peripheral blood (7, 147, 149, 150). CD56bright and CD56dim NK cells are equipped with distinct functions. The former population responds rapidly to interleukin-mediated stimulation with proliferation and cytokine secretion, while the latter population displays higher cytolytic capacity and lower proliferation (7, 8, 149). During the process of maturation, CD94/NKG2A is the first receptor that is expressed on immature NK cells. Together with the downregulation of CD56 expression, NK cells upregulate CD16 expression, lose NKG2A, and acquire KIR receptors. Finally, a subset of CD56dim cells continue to differentiate and express CD57, together with an increased KIR expression and a completely abolished proliferative ability (150, 151).

In HSCTs with post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PT-Cy) as GVHD prophylaxis, NK cells experience two waves of expansion. After graft infusion, peripheral NK cells and T cells (mainly mature cells from the donor) were detectable at very low levels. PT-Cy administration results in a further decrease in T cells and NK cells, and NK cells are barely detectable in the peripheral blood. Subsequently, the reconstituted NK cells gradually recover and express high levels of CD56 and NKG2A. Around 60 days after transplantation, the KIR expression returns to normal. The expression of CD56 and NKG2A gradually decreases and becomes stable at 9–12 months post-transplantation. Other receptors expressed on NK cells, such as DNAM-1and 2B4, also require several months to return to normal (152). In summary, post-transplantation NK cell reconstitution is a long-term process (124, 125, 152).

As described earlier, the random combination of KIR receptor and HLA ligand can exist in healthy individuals. However, the autoimmune attack is inhibited because each NK cell expresses at least one self-inhibitory receptor. To avoid autoreactivity, NK cells must undergo an education process: NK cells expressing inhibitory KIR for self-HLA ligand (self-KIR) are educated, which means that these cells can be inhibited by self-inhibitory signals and become alloreactive against self-HLA-deficient targets. In contrast, NK cells expressing an inhibitory KIR that lacks a self-HLA ligand (non-self KIR) are uneducated, which means that they are tolerant to the self but also to infected or malignant cells (19, 21).

In the last decades, studies on KIR education have much extended our knowledge of NK cell function. After transplantation, most reconstituted NK cells express a donor-like KIR repertoire that is significantly different from that of recipient NK cells prior to transplantation (124, 151). Therefore, reconstituted NK cells expressing donor KIR may exert alloreactivity in recipients, or become anergic, as recipients may not present the cognate HLA (Figure 3). Foley et al. and Björklund et al. observed that reconstituted NK cells with non-self KIR remained tolerant, while those with self KIR acquired better functions after transplantation (65, 153). However, Yu et al. reached the opposite conclusion that alloreactive NK cells broke the self-tolerance and displayed functional capacities in the first 3 months, then gradually acquired self-tolerance by day 100 post-transplantation (154). Rathmann et al. also suggested that alloreactive NK cells were increased in the peripheral blood and exhibited a GVL effect in the early period after transplantation (155). One possible explanation for this observation is that the infusion of a megadose of donor CD34+ cells may create a transient donor dominant HLA environment in recipient bone marrow, and the early reconstituted NK cells expressing non-self KIR for the recipient may become educated by donor HLA and acquire functions (156). After migration to a recipient-dominant environment, reconstituted NK cells may gradually lose their responsiveness.

In murine studies, it was observed that mature NK cells from major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-sufficient mice become hyporesponsive after transfusion into MHC class I-deficient mice. Conversely, anergic NK cells from MHC class I-deficient mice acquired functions after exposure to the MHC class I-sufficient environment (157, 158). Using a murine transgenic model of HLA-B*27:05 exhibiting the Bw4 ligand for KIR3DL1, Boudreau et al. observed similar results in stem cell transplantation. CD34+ cells from KIR3DL1+ donors were transfused to B27 Tg+ and Tg− mice, respectively. A functional analysis suggested that the most cytotoxic responsive cells were KIR3DL1+ NK cells from Bw4+ donors and developed in B27 Tg+ mice (Bw4+ donors and Tg+ mice), while the least-responsive cells were KIR3DL1+ NK cells from Bw4− donors and developed in Tg− mice (Bw4− donors and Tg− mice). Recipients with the other two combinations (Bw4+ donors and Tg− mice and Bw4− donors and Tg+ mice) displayed a medium level of responsiveness. The stepwise escalation of NK cell responsiveness suggested that both the donor and recipient MHC environments are critical for the maintenance and adjustment of NK cell education (159).

Recently, the Nowak team proposed that inhibitory KIR (iKIR)-HLA pairs could predict the post-HSCT NK cell education status, i.e., donors presenting cognate HLA for donor iKIR and recipients lacking it predict a downward education level; in contrast, recipients presenting cognate HLA for donor iKIR and donors lacking it predict an upward education level. Those authors found that the decrease in iKIR–HLA pairs post-transplantation is associated with a higher relapse and poorer survival (160–162), indicating that reconstituted NK cells acquire better functions after interaction with more cognate HLA class I ligands in recipients. Zhao et al. also observed that, when the donors and recipients expressed three major HLA ligands (HLA-C1, C2, Bw4), patients with AML and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) experienced the lowest relapse rate, and NK cells expressing three inhibitory receptors exhibited the greatest cytotoxicity and cytokine responsiveness against K562 targets (163).

Based on the findings described above, it is likely that three factors (donor KIR, donor HLA, and recipient HLA) all contribute to the variation in NK cell function. Therefore, the KIR ligand and receptor-ligand models, which only take two factors into account, may not accurately predict donors that exhibit the greatest NK cell function post-transplantation.

Although CMV reactivation suggests an immune-compromised state, patients who experienced CMV reactivation had a lower relapse rate or better survival (70, 98, 99, 164). This protective effect might be attributed to the rapid maturation of NK cells. During CMV reactivation, NK cells that express NKG2C rapidly expand and continue to increase for 1 year (165). The number of CD56dim NK cells in the peripheral blood, their KIR expression, and IFN-γ production in response to K562 cells were also elevated in patients who developed CMV reactivation (165–173). Furthermore, nearly 60% of NKG2C+ NK cells achieved complete differentiation and expressed CD57 after CMV reactivation. These cells were termed memory-like NK cells and could be detected long after the primary CMV infection, offering a long-lasting protection (147, 166). In contrast, for non-CMV-infected patients, a higher proportion of NKG2A+ NKG2C− KIR− NK cells in the peripheral blood indicates a slow NK cell maturation. Interestingly, CMV antigen exposure to recipients also leads to an increased frequency of NKG2C+ NK cells, accompanied by increased KIR expression and decreased NKG2A expression (174).

As mentioned above, T cells in the graft impair the recovery of NK cells and KIR reconstitution (127–130). A possible explanation for this observation is that T cells compete with NK cells for IL-15, a cytokine that regulates immune cell survival and development (175, 176). Unlike ex-vivo TCD grafts, pre-transplant anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) administration results in partial T cell depletion. Two recent studies found that ATG administration promoted NK cell recovery and delayed the reconstitution of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, while sparing the effector memory T and regulatory T cells (Tregs) (177, 178). Compared with ATG, PT-Cy is more efficient in eliminating NK cells, with a higher residual ratio of CD4+ T cells and Tregs (179). Of note, several studies showed that T cells in the graft may contribute to a better NK cell function (153, 180). Several studies reported that CD56bright NK cells in lymph nodes could be stimulated by IL-2-producing T cells, resulting in NK cell maturation with higher IFN-γ secretion and cytotoxic functions (181, 182).

The relationship between GVHD and NK cell reconstitution remains controversial. Previous studies demonstrated that GVHD correlated with an impaired NK cell reconstitution and KIR expression (183–185). Ullrich et al. found that CD56bright NK cells were dramatically decreased in patients with GVHD, while CD56dim NK cells, the more mature subtype, did not show significant changes (185). In addition, Hu et al. found that the NKG2A subset of CD56dim NK cells was significantly decreased in patients with GVHD. Remarkably, a functional analysis showed that NKG2A+ NK cells from GVHD and non-GVHD patients exhibited a comparable GVL effect. Furthermore, the co-culture of donor T cells with NKG2A+ cells from non-GVHD patients suggested that NKG2A+ NK cells inhibit T cell proliferation and activation, indicating that the decreased number of NKG2A+ NK cells might be a cause, rather than a consequence, of GVHD (186). In addition, the administration of immunosuppressive agents could also affect immune recovery. Both Ullrich et al. and Giebel et al. suggested that steroid treatment, rather than GVHD, was related to the delayed NK cell reconstitution (184, 187).

Numerous studies have found that alloreactive NK cells affect treatment outcomes. Although great progress has been made through both pre-clinical and clinical investigations based on the three KIR models, the controversy remains, especially regarding the benefits of KIR alloreactivity on relapse control. Recent findings showed that donor KIR, donor HLA, and recipient HLA environment all contribute to the variation of NK cell function. The newly proposed iKIR-HLA pair model needs to be further examined in the future.

NK cells, the lymphocytes that are reconstituted first after transplantation, could be negatively affected by the T cells in the graft. However, NK cell function could also be promoted through T-cell-mediated activation. The exact interactions between NK and T cells, as well as the strategy to trigger a potential synergistic NK and T cell effect remains to be investigated.

It is noteworthy that the protective role of NK cell alloreactivity in relapse protection mostly exists in myeloid disease; in fact, some studies even found that NK cell alloreactivity increased the risk of relapse for patients with lymphoid disease. The discrepancy between expressing ligands among different diseases and their binding affinity to KIR should raise more attention. In this way, we might identify which patients would benefit from the KIR-based donor selection.

In the early period after transplantation, reconstituted alloreactive NK cell may not directly influence GVHD occurrence, as it is immature and it could be affected by T cells and immunosuppressive agents. The compatibility between donor KIR and the recipient HLA ligand may protect patients from infection. In the late period after transplantation, the iKIR-HLA pair model may reflect the variation in NK cell function, and quantitative analysis of KIR-HLA interactions may provide more convincing results regarding relapse and survival.

YZ and HH designed. FG and YY wrote this paper. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81670148 and 81730008) and Medical and Health Research Project of Zhejiang Province (2012KYB709).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Gratwohl A, Brand R, Frassoni F, Rocha V, Niederwieser D, Reusser P, et al. Cause of death after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in early leukaemias: an EBMT analysis of lethal infectious complications and changes over calendar time. Bone Marrow Trans. (2005) 36:757–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705140

2. Wingard JR, Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, Wang Z, Sobocinski KA, Jacobsohn D, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. (2011) 29:2230–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.7212

3. Holmqvist AS, Chen Y, Wu J, Battles K, Bhatia R, Francisco L, et al. Assessment of late mortality risk after allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation performed in childhood. JAMA Oncol. (2018) 4:e182453. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2453

4. Styczynski J, Tridello G, Koster L, Iacobelli S, van Biezen A, van der Werf S, et al. Death after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: changes over calendar year time, infections and associated factors. Bone Marrow Trans. (2020) 55:126–36. doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0624-z

5. Lanier LL, Le AM, Civin CI, Loken MR, Phillips JH. The relationship of CD16 (Leu-11) and Leu-19 (NKH-1) antigen expression on human peripheral blood NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Immunol. (1986) 136:4480-6.

6. Almeida-Oliveira A, Smith-Carvalho M, Porto LC, Cardoso-Oliveira J, Ribeiro Ados S, Falcao RR, et al. Age-related changes in natural killer cell receptors from childhood through old age. Hum Immunol. (2011) 72:319–29. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2011.01.009

7. Vivier E, Tomasello E, Baratin M, Walzer T, Ugolini S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol. (2008) 9:503–10. doi: 10.1038/ni1582

8. Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cells. Blood. (2008) 112:461–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-077438

9. Lanier LL. NK cell receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. (1998) 16:359–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.359

10. Moretta A, Bottino C, Vitale M, Pende D, Cantoni C, Mingari MC, et al. Activating receptors and coreceptors involved in human natural killer cell-mediated cytolysis. Annu Rev Immunol. (2001) 19:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.197

11. Pegram HJ, Andrews DM, Smyth MJ, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH. Activating and inhibitory receptors of natural killer cells. Immunol Cell Biol. (2011) 89:216–24. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.78

12. Wilson MJ, Torkar M, Trowsdale J. Genomic organization of a human killer cell inhibitory receptor gene. Tissue Antigens. (1997) 49:574–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1997.tb02804.x

13. Hsu KC, Chida S, Geraghty DE, Dupont B. The killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) genomic region: gene-order, haplotypes and allelic polymorphism. Immunol Rev. (2002) 190:40–52. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2002.19004.x

14. Parham P, Moffett A. Variable NK cell receptors and their MHC class I ligands in immunity, reproduction and human evolution. Nat Rev Immunol. (2013) 13:133–44. doi: 10.1038/nri3370

15. Manser AR, Weinhold S, Uhrberg M. Human KIR repertoires: shaped by genetic diversity and evolution. Immunol Rev. (2015) 267:178–96. doi: 10.1111/imr.12316

16. Leung W. Use of NK cell activity in cure by transplant. Br J Haematol. (2011) 155:14–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08823.x

17. Kim S, Poursine-Laurent J, Truscott SM, Lybarger L, Song YJ, Yang L, et al. Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature. (2005) 436:709–13. doi: 10.1038/nature03847

18. Fernandez NC, Treiner E, Vance RE, Jamieson AM, Lemieux S, Raulet DH. A subset of natural killer cells achieves self-tolerance without expressing inhibitory receptors specific for self-MHC molecules. Blood. (2005) 105:4416–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3156

19. Anfossi N, Andre P, Guia S, Falk CS, Roetynck S, Stewart CA, et al. Human NK cell education by inhibitory receptors for MHC class I. Immunity. (2006) 25:331–42. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.013

20. Fauriat C, Ivarsson MA, Ljunggren HG, Malmberg KJ, Michaelsson J. Education of human natural killer cells by activating killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors. Blood. (2010) 115:1166–74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-245746

21. Schonberg K, Fischer JC, Kogler G, Uhrberg M. Neonatal NK-cell repertoires are functionally, but not structurally, biased toward recognition of self HLA class I. Blood. (2011) 117:5152–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-334441

22. Vivier E, Nunes JA, Vely F. Natural killer cell signaling pathways. Science. (2004) 306:1517–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1103478

23. Valiante NM, Uhrberg M, Shilling HG, Lienert-Weidenbach K, Arnett KL, D'Andrea A, et al. Functionally and structurally distinct NK cell receptor repertoires in the peripheral blood of two human donors. Immunity. (1997) 7:739–51. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80393-3

24. Demanet C, Mulder A, Deneys V, Worsham MJ, Maes P, Claas FH, et al. Down-regulation of HLA-A and HLA-Bw6, but not HLA-Bw4, allospecificities in leukemic cells: an escape mechanism from CTL and NK attack? Blood. (2004) 103:3122–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2500

25. Masuda K, Hiraki A, Fujii N, Watanabe T, Tanaka M, Matsue K, et al. Loss or down-regulation of HLA class I expression at the allelic level in freshly isolated leukemic blasts. Cancer Sci. (2007) 98:102–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00356.x

26. Verheyden S, Ferrone S, Mulder A, Claas FH, Schots R, De Moerloose B, et al. Role of the inhibitory KIR ligand HLA-Bw4 and HLA-C expression levels in the recognition of leukemic cells by Natural Killer cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2009) 58:855–65. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0601-7

27. Reusing SB, Manser AR, Enczmann J, Mulder A, Claas FH, Carrington M, et al. Selective downregulation of HLA-C and HLA-E in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. (2016) 174:477–80. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13777

28. Cerwenka A, Lanier LL. Natural killer cells, viruses and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. (2001) 1:41–9. doi: 10.1038/35095564

29. Seliger B, Ritz U, Ferrone S. Molecular mechanisms of HLA class I antigen abnormalities following viral infection and transformation. Int J Cancer. (2006) 118:129–38. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21312

30. Pende D, Marcenaro S, Falco M, Martini S, Bernardo ME, Montagna D, et al. Anti-leukemia activity of alloreactive NK cells in KIR ligand-mismatched haploidentical HSCT for pediatric patients: evaluation of the functional role of activating KIR and redefinition of inhibitory KIR specificity. Blood. (2009) 113:3119–29. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-164103

31. Thiruchelvam-Kyle L, Hoelsbrekken SE, Saether PC, Bjornsen EG, Pende D, Fossum S, et al. The activating human NK Cell receptor KIR2DS2 recognizes a beta2-microglobulin-independent ligand on cancer cells. J Immunol. (2017) 198:2556–67. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600930

32. Ogonek J, Kralj Juric M, Ghimire S, Varanasi PR, Holler E, Greinix H, et al. Immune reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front Immunol. (2016) 7:507. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00507

33. de Witte MA, Sarhan D, Davis Z, Felices M, Vallera DA, Hinderlie P, et al. Early reconstitution of NK and gammadelta T cells and its implication for the design of post-transplant immunotherapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2018) 24:1152–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.02.023

34. Alvarez M, Sun K, Murphy WJ. Mouse host unlicensed NK cells promote donor allogeneic bone marrow engraftment. Blood. (2016) 127:1202–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-665570

35. Asai O, Longo DL, Tian ZG, Hornung RL, Taub DD, Ruscetti FW, et al. Suppression of graft-versus-host disease and amplification of graft-versus-tumor effects by activated natural killer cells after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Invest. (1998) 101:1835–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI1268

36. Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, Perruccio K, Shlomchik WD, Tosti A, et al. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science. (2002) 295:2097–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068440

37. Olson JA, Leveson-Gower DB, Gill S, Baker J, Beilhack A, Negrin RS. NK cells mediate reduction of GVHD by inhibiting activated, alloreactive T cells while retaining GVT effects. Blood. (2010) 115:4293–301. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-222190

38. Hu B, Bao G, Zhang Y, Lin D, Wu Y, Wu D, et al. Donor NK Cells and IL-15 promoted engraftment in nonmyeloablative allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol. (2012) 189:1661–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103199

39. Leung W, Iyengar R, Turner V, Lang P, Bader P, Conn P, et al. Determinants of antileukemia effects of allogeneic NK cells. J Immunol. (2004) 172:644–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.644

40. Cooley S, Trachtenberg E, Bergemann TL, Saeteurn K, Klein J, Le CT, et al. Donors with group B KIR haplotypes improve relapse-free survival after unrelated hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. (2009) 113:726–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171926

41. Davies SM, Ruggieri L, DeFor T, Wagner JE, Weisdorf DJ, Miller JS, et al. Evaluation of KIR ligand incompatibility in mismatched unrelated donor hematopoietic transplants. Killer immunoglobulin-like receptor. Blood. (2002) 100:3825–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1197

42. Giebel S, Locatelli F, Lamparelli T, Velardi A, Davies S, Frumento G, et al. Survival advantage with KIR ligand incompatibility in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from unrelated donors. Blood. (2003) 102:814–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0091

43. Schaffer M, Malmberg KJ, Ringden O, Ljunggren HG, Remberger M. Increased infection-related mortality in KIR-ligand-mismatched unrelated allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Transplantation. (2004) 78:1081–5. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000137103.19717.86

44. Elmaagacli AH, Ottinger H, Koldehoff M, Peceny R, Steckel NK, Trenschel R, et al. Reduced risk for molecular disease in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia after transplantation from a KIR-mismatched donor. Transplantation. (2005) 79:1741–7. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000164500.16052.3C

45. Yabe T, Matsuo K, Hirayasu K, Kashiwase K, Kawamura-Ishii S, Tanaka H, et al. Donor killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) genotype-patient cognate KIR ligand combination and antithymocyte globulin preadministration are critical factors in outcome of HLA-C-KIR ligand-mismatched T cell-replete unrelated bone marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2008) 14:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.09.012

46. Verneris MR, Miller JS, Hsu KC, Wang T, Sees JA, Paczesny S, et al. Investigation of donor KIR content and matching in children undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute leukemia. Blood Adv. (2020) 4:1350–6. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001284

47. Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Capanni M, Urbani E, Carotti A, Aloisi T, et al. Donor natural killer cell allorecognition of missing self in haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: challenging its predictive value. Blood. (2007) 110:433–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-038687

48. Huang XJ, Zhao XY, Liu DH, Liu KY, Xu LP. Deleterious effects of KIR ligand incompatibility on clinical outcomes in haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation without in vitro T-cell depletion. Leukemia. (2007) 21:848–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404566

49. Zhao XY, Huang XJ, Liu KY, Xu LP, Liu DH. Prognosis after unmanipulated HLA-haploidentical blood and marrow transplantation is correlated to the numbers of KIR ligands in recipients. Eur J Haematol. (2007) 78:338–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00822.x

50. Michaelis SU, Mezger M, Bornhauser M, Trenschel R, Stuhler G, Federmann B, et al. KIR haplotype B donors but not KIR-ligand mismatch result in a reduced incidence of relapse after haploidentical transplantation using reduced intensity conditioning and CD3/CD19-depleted grafts. Ann Hematol. (2014) 93:1579–86. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2084-2

51. Mancusi A, Ruggeri L, Urbani E, Pierini A, Massei MS, Carotti A, et al. Haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation from KIR ligand-mismatched donors with activating KIRs reduces nonrelapse mortality. Blood. (2015) 125:3173–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-599993

52. Yahng SA, Jeon YW, Yoon JH, Shin SH, Lee SE, Cho BS, et al. Negative impact of unidirectional host-versus-graft killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor ligand mismatch on transplantation outcomes after unmanipulated haploidentical peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2016) 22:316–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.018

53. Zhao XY, Luo XY, Yu XX, Zhao XS, Han TT, Chang YJ, et al. Recipient-donor KIR ligand matching prevents CMV reactivation post-haploidentical T cell-replete transplantation. Br J Haematol. (2017) 177:766–81. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14622

54. Wanquet A, Bramanti S, Harbi S, Furst S, Legrand F, Faucher C, et al. Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor-ligand mismatch in donor versus recipient direction provides better graft-versus-tumor effect in patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing allogeneic t cell-replete haploidentical transplantation followed by post-transplant cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2018) 24:549–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.11.042

55. Shimoni A, Labopin M, Lorentino F, Van Lint MT, Koc Y, Gulbas Z, et al. Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor ligand mismatching and outcome after haploidentical transplantation with post-transplant cyclophosphamide. Leukemia. (2019) 33:230–9. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0170-5

56. Cook MA, Milligan DW, Fegan CD, Darbyshire PJ, Mahendra P, Craddock CF, et al. The impact of donor KIR and patient HLA-C genotypes on outcome following HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for myeloid leukemia. Blood. (2004) 103:1521–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0438

57. Verheyden S, Schots R, Duquet W, Demanet C. A defined donor activating natural killer cell receptor genotype protects against leukemic relapse after related HLA-identical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. (2005) 19:1446–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403839

58. Hsu KC, Gooley T, Malkki M, Pinto-Agnello C, Dupont B, Bignon JD, et al. KIR ligands and prediction of relapse after unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2006) 12:828–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.04.008

59. Clausen J, Wolf D, Petzer AL, Gunsilius E, Schumacher P, Kircher B, et al. Impact of natural killer cell dose and donor killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) genotype on outcome following human leucocyte antigen-identical haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Exp Immunol. (2007) 148:520–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03360.x

60. Ludajic K, Balavarca Y, Bickeboller H, Rosenmayr A, Fae I, Fischer GF, et al. KIR genes and KIR ligands affect occurrence of acute GVHD after unrelated, 12/12 HLA matched, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2009) 44:97–103. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.432

61. Linn YC, Phang CY, Lim TJ, Chong SF, Heng KK, Lee JJ, et al. Effect of missing killer-immunoglobulin-like receptor ligand in recipients undergoing HLA full matched, non-T-depleted sibling donor transplantation: a single institution experience of 151 Asian patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2010) 45:1031–7. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.303

62. Wu X, He J, Wu D, Bao X, Qiu Q, Yuan X, et al. KIR and HLA-Cw genotypes of donor-recipient pairs influence the rate of CMV reactivation following non-T-cell deleted unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation. Am J Hematol. (2009) 84:776–7. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21527

63. Gagne K, Busson M, Bignon JD, Balere-Appert ML, Loiseau P, Dormoy A, et al. Donor KIR3DL1/3DS1 gene and recipient Bw4 KIR ligand as prognostic markers for outcome in unrelated hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2009) 15:1366–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.06.015

64. Clausen J, Kircher B, Auberger J, Schumacher P, Ulmer H, Hetzenauer G, et al. The role of missing killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor ligands in T cell replete peripheral blood stem cell transplantation from HLA-identical siblings. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2010) 16:273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.10.021

65. Bjorklund AT, Schaffer M, Fauriat C, Ringden O, Remberger M, Hammarstedt C, et al. NK cells expressing inhibitory KIR for non-self-ligands remain tolerant in HLA-matched sibling stem cell transplantation. Blood. (2010) 115:2686–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-229740

66. Wu GQ, Zhao YM, Lai XY, Luo Y, Tan YM, Shi JM, et al. The beneficial impact of missing KIR ligands and absence of donor KIR2DS3 gene on outcome following unrelated hematopoietic SCT for myeloid leukemia in the Chinese population. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2010) 45:1514–21. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.3

67. Zhou H, Bao X, Wu X, Tang X, Wang M, Wu D, et al. Donor selection for KIR B haplotype of the centromeric motifs can improve the outcome after HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2013) doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.10.017

68. Sobecks RM, Wang T, Askar M, Gallagher MM, Haagenson M, Spellman S, et al. Impact of KIR and HLA genotypes on outcomes after reduced-intensity conditioning hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2015) 21:1589–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.05.002

69. Park S, Kim K, Jang JH, Kim SJ, Kim WS, Kang ES, et al. KIR alloreactivity based on the receptor-ligand model is associated with improved clinical outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Result of single center prospective study. Hum Immunol. (2015) 76:636–43. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2015.09.009

70. Cardozo DM, Marangon AV, da Silva RF, Aranha FJP, Visentainer JEL, Bonon SHA, et al. Synergistic effect of KIR ligands missing and cytomegalovirus reactivation in improving outcomes of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation from HLA-matched sibling donor for treatment of myeloid malignancies. Hum Immunol. (2016) 77:861–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2016.07.003

71. Faridi RM, Kemp TJ, Dharmani-Khan P, Lewis V, Tripathi G, Rajalingam R, et al. Donor-recipient matching for KIR genotypes reduces chronic GVHD and missing inhibitory KIR ligands protect against relapse after myeloablative, HLA matched hematopoietic cell transplantation. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0158242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158242

72. Neuchel C, Furst D, Niederwieser D, Bunjes D, Tsamadou C, Wulf G, et al. Impact of donor activating KIR genes on HSCT outcome in C1-ligand negative myeloid disease patients transplanted with unrelated donors-a retrospective study. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0169512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169512

73. Arima N, Kanda J, Tanaka J, Yabe T, Morishima Y, Kim SW, et al. Homozygous HLA-C1 is associated with reduced risk of relapse after HLA-matched transplantation in patients with myeloid leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2018) 24:717–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.11.029

74. Gaafar A, Sheereen A, Almohareb F, Eldali A, Chaudhri N, Mohamed SY, et al. Prognostic role of KIR genes and HLA-C after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in a patient cohort with acute myeloid leukemia from a consanguineous community. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2018) 53:1170–9. doi: 10.1038/s41409-018-0123-7

75. Arima N, Kanda J, Yabe T, Morishima Y, Tanaka J, Kako S, et al. Increased relapse risk of acute lymphoid leukemia in homozygous HLA-C1 patients after HLA-matched allogeneic transplantation: a japanese national registry study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2020) 26:431–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.10.032

76. Chen DF, Prasad VK, Broadwater G, Reinsmoen NL, DeOliveira A, Clark A, et al. Differential impact of inhibitory and activating Killer Ig-Like Receptors (KIR) on high-risk patients with myeloid and lymphoid malignancies undergoing reduced intensity transplantation from haploidentical related donors. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2012) 47:817–23. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.181

77. Zhao XY, Chang YJ, Xu LP, Zhang XH, Liu KY, Li D, et al. HLA and KIR genotyping correlates with relapse after T-cell-replete haploidentical transplantation in chronic myeloid leukaemia patients. Br J Cancer. (2014) 111:1080–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.423

78. Zhao XY, Chang YJ, Zhao XS, Xu LP, Zhang XH, Liu KY, et al. Recipient expression of ligands for donor inhibitory KIRs enhances NK-cell function to control leukemic relapse after haploidentical transplantation. Eur J Immunol. (2015) 45:2396–408. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445057

79. Solomon SR, Aubrey MT, Zhang X, Piluso A, Freed BM, Brown S, et al. Selecting the best donor for haploidentical transplant: impact of HLA, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor genotyping, and other clinical variables. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2018) 24:789–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.01.013

80. Willem C, Makanga DR, Guillaume T, Maniangou B, Legrand N, Gagne K, et al. Impact of KIR/HLA incompatibilities on NK cell reconstitution and clinical outcome after T cell-replete haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with posttransplant cyclophosphamide. J Immunol. (2019) 202:2141–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801489

81. Chen C, Busson M, Rocha V, Appert ML, Lepage V, Dulphy N, et al. Activating KIR genes are associated with CMV reactivation and survival after non-T-cell depleted HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation for malignant disorders. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2006) 38:437–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705468

82. Schellekens J, Rozemuller EH, Petersen EJ, van den Tweel JG, Verdonck LF, Tilanus MG. Activating KIRs exert a crucial role on relapse and overall survival after HLA-identical sibling transplantation. Mol Immunol. (2008) 45:2255–61. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.11.014

83. van der Meer A, Schaap NP, Schattenberg AV, van Cranenbroek B, Tijssen HJ, Joosten I. KIR2DS5 is associated with leukemia free survival after HLA identical stem cell transplantation in chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Mol Immunol. (2008) 45:3631–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.04.016

84. Zaia JA, Sun JY, Gallez-Hawkins GM, Thao L, Oki A, Lacey SF, et al. The effect of single and combined activating killer immunoglobulin-like receptor genotypes on cytomegalovirus infection and immunity after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2009) 15:315–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.11.030

85. Bao XJ, Hou LH, Sun AN, Qiu QC, Yuan XN, Chen MH, et al. The impact of KIR2DS4 alleles and the expression of KIR in the development of acute GVHD after unrelated allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2010) 45:1435–41. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.357

86. Venstrom JM, Gooley TA, Spellman S, Pring J, Malkki M, Dupont B, et al. Donor activating KIR3DS1 is associated with decreased acute GVHD in unrelated allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. (2010) 115:3162–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236943

87. Tomblyn M, Young JA, Haagenson MD, Klein JP, Trachtenberg EA, Storek J, et al. Decreased infections in recipients of unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation from donors with an activating KIR genotype. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2010) 16:1155–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.02.024

88. Cooley S, Weisdorf DJ, Guethlein LA, Klein JP, Wang T, Le CT, et al. Donor selection for natural killer cell receptor genes leads to superior survival after unrelated transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. (2010) 116:2411–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-283051

89. Venstrom JM, Pittari G, Gooley TA, Chewning JH, Spellman S, Haagenson M, et al. HLA-C-dependent prevention of leukemia relapse by donor activating KIR2DS1. N Engl J Med. (2012) 367:805–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200503

90. Impola U, Turpeinen H, Alakulppi N, Linjama T, Volin L, Niittyvuopio R, et al. Donor haplotype B of NK KIR receptor reduces the relapse risk in HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation of AML patients. Front Immunol. (2014) 5:405. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00405

91. Bao X, Wang M, Zhou H, Zhang H, Wu X, Yuan X, et al. Donor killer immunoglobulin-like receptor profile bx1 imparts a negative effect and centromeric b-specific gene motifs render a positive effect on standard-risk acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome patient survival after unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2016) 22:232–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.007

92. Bachanova V, Weisdorf DJ, Wang T, Marsh SGE, Trachtenberg E, Haagenson MD, et al. Donor KIR B genotype improves progression-free survival of non-hodgkin lymphoma patients receiving unrelated donor transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2016) 22:1602–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.05.016

93. Burek Kamenaric M, Stingl Jankovic K, Grubic Z, Serventi Seiwerth R, Maskalan M, Nemet D, et al. The impact of KIR2DS4 gene on clinical outcome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Hum Immunol. (2017) 78:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2016.11.010

94. Hosokai R, Masuko M, Shibasaki Y, Saitoh A, Furukawa T, Imai C. Donor killer immunoglobulin-like receptor haplotype B/x induces severe acute graft-versus-host disease in the presence of human leukocyte antigen mismatch in T cell-replete hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2017) 23:606–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.12.638

95. Sahin U, Dalva K, Gungor F, Ustun C, Beksac M. Donor-recipient killer immunoglobulin like receptor (KIR) genotype matching has a protective effect on chronic graft versus host disease and relapse incidence following HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Hematol. (2018) 97:1027–39. doi: 10.1007/s00277-018-3274-0

96. Heatley SL, Mullighan CG, Doherty K, Danner S, O'Connor GM, Hahn U, et al. Activating KIR haplotype influences clinical outcome following HLA-matched sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. HLA. (2018) 92:74–82. doi: 10.1111/tan.13327

97. Babor F, Peters C, Manser AR, Glogova E, Sauer M, Potschger U, et al. Presence of centromeric but absence of telomeric group B KIR haplotypes in stem cell donors improve leukaemia control after HSCT for childhood ALL. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2019) 54:1847–58. doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0543-z

98. Tordai A, Bors A, Kiss KP, Balassa K, Andrikovics H, Batai A, et al. Donor KIR2DS1 reduces the risk of transplant related mortality in HLA-C2 positive young recipients with hematological malignancies treated by myeloablative conditioning. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0218945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218945

99. Nakamura R, Gendzekhadze K, Palmer J, Tsai NC, Mokhtari S, Forman SJ, et al. Influence of donor KIR genotypes on reduced relapse risk in acute myelogenous leukemia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with CMV reactivation. Leuk Res. (2019) 87:106230. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2019.106230

100. Bultitude WP, Schellekens J, Szydlo RM, Anthias C, Cooley SA, Miller JS, et al. Presence of donor-encoded centromeric KIR B content increases the risk of infectious mortality in recipients of myeloablative, T-cell deplete, HLA-matched HCT to treat AML. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2020) doi: 10.1038/s41409-020-0858-9. [Epub ahead of print].

101. Weisdorf D, Cooley S, Wang T, Trachtenberg E, Vierra-Green C, Spellman S, et al. KIR B donors improve the outcome for AML patients given reduced intensity conditioning and unrelated donor transplantation. Blood Adv. (2020) 4:740–54. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001053

102. Symons HJ, Leffell MS, Rossiter ND, Zahurak M, Jones RJ, Fuchs EJ. Improved survival with inhibitory killer immunoglobulin receptor (KIR) gene mismatches and KIR haplotype B donors after nonmyeloablative, HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2010) 16:533–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.022

103. Oevermann L, Michaelis SU, Mezger M, Lang P, Toporski J, Bertaina A, et al. KIR B haplotype donors confer a reduced risk for relapse after haploidentical transplantation in children with ALL. Blood. (2014) 124:2744–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-565069

104. Perez-Martinez A, Ferreras C, Pascual A, Gonzalez-Vicent M, Alonso L, Badell I, et al. Haploidentical transplantation in high-risk pediatric leukemia: A retrospective comparative analysis on behalf of the Spanish working Group for bone marrow transplantation in children (GETMON) and the Spanish Grupo for hematopoietic transplantation (GETH). Am J Hematol. (2020) 95:28–37. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25661

105. Yu H, Tian Y, Wang Y, Mineishi S, Zhang Y. Dendritic cell regulation of graft-vs.-host disease: immunostimulation and tolerance. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:93. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00093

106. Horowitz MM, Gale RP, Sondel PM, Goldman JM, Kersey J, Kolb HJ, et al. Graft-versus-leukemia reactions after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. (1990) 75:555-62. doi: 10.1182/blood.V75.3.555.bloodjournal753555

107. Marmont AM, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, Sobocinski K, Ash RC, van Bekkum DW, et al. T-cell depletion of HLA-identical transplants in leukemia. Blood. (1991) 78:2120–30. doi: 10.1182/blood.V78.8.2120.bloodjournal7882120

108. Champlin RE, Passweg JR, Zhang MJ, Rowlings PA, Pelz CJ, Atkinson KA, et al. T-cell depletion of bone marrow transplants for leukemia from donors other than HLA-identical siblings: advantage of T-cell antibodies with narrow specificities. Blood. (2000) 95:3996–4003.

109. Murphy WJ, Bennett M, Kumar V, Longo DL. Donor-type activated natural killer cells promote marrow engraftment and B cell development during allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol. (1992) 148:2953–60.

110. Huber CM, Doisne JM, Colucci F. IL-12/15/18-preactivated NK cells suppress GvHD in a mouse model of mismatched hematopoietic cell transplantation. Eur J Immunol. (2015) 45:1727–35. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445200

111. Xun C, Brown SA, Jennings CD, Henslee-Downey PJ, Thompson JS. Acute graft-versus-host-like disease induced by transplantation of human activated natural killer cells into SCID mice. Transplantation. (1993) 56:409–17. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199308000-00031

112. Xun CQ, Thompson JS, Jennings CD, Brown SA. The effect of human IL-2-activated natural killer and T cells on graft-versus-host disease and graft-versus-leukemia in SCID mice bearing human leukemic cells. Transplantation. (1995) 60:821–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199510270-00011

113. Mowat AM. Antibodies to IFN-gamma prevent immunologically mediated intestinal damage in murine graft-versus-host reaction. Immunology. (1989) 68:18–23.

114. MacDonald GC, Gartner JG. Prevention of acute lethal graft-versus-host disease in F1 hybrid mice by pretreatment of the graft with anti-NK-1.1 and complement. Transplantation. (1992) 54:147–51. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199207000-00026

115. Passweg JR, Tichelli A, Meyer-Monard S, Heim D, Stern M, Kuhne T, et al. Purified donor NK-lymphocyte infusion to consolidate engraftment after haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. (2004) 18:1835–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403524

116. Rizzieri DA, Storms R, Chen DF, Long G, Yang Y, Nikcevich DA, et al. Natural killer cell-enriched donor lymphocyte infusions from A 3-6/6 HLA matched family member following nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2010) 16:1107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.02.018

117. Introna M, Borleri G, Conti E, Franceschetti M, Barbui AM, Broady R, et al. Repeated infusions of donor-derived cytokine-induced killer cells in patients relapsing after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a phase I study. Haematologica. (2007) 92:952–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11132

118. Yoon SR, Lee YS, Yang SH, Ahn KH, Lee JH, Lee JH, et al. Generation of donor natural killer cells from CD34(+) progenitor cells and subsequent infusion after HLA-mismatched allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a feasibility study. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2010) 45:1038–46. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.304

119. Ciurea SO, Schafer JR, Bassett R, Denman CJ, Cao K, Willis D, et al. Phase 1 clinical trial using mbIL21 ex vivo-expanded donor-derived NK cells after haploidentical transplantation. Blood. (2017) 130:1857–68. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-785659

120. Bjorklund AT, Carlsten M, Sohlberg E, Liu LL, Clancy T, Karimi M, et al. Complete Remission with Reduction of High-Risk Clones following Haploidentical NK-Cell Therapy against MDS and AML. Clin Cancer Res. (2018) 24:1834–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3196

121. Vela M, Corral D, Carrasco P, Fernandez L, Valentin J, Gonzalez B, et al. Haploidentical IL-15/41BBL activated and expanded natural killer cell infusion therapy after salvage chemotherapy in children with relapsed and refractory leukemia. Cancer Lett. (2018) 422:107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.02.033

122. Jaiswal SR, Zaman S, Nedunchezhian M, Chakrabarti A, Bhakuni P, Ahmed M, et al. CD56-enriched donor cell infusion after post-transplantation cyclophosphamide for haploidentical transplantation of advanced myeloid malignancies is associated with prompt reconstitution of mature natural killer cells and regulatory T cells with reduced incidence of acute graft versus host disease: A pilot study. Cytotherapy. (2017) 19:531–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.12.006

123. Shah NN, Baird K, Delbrook CP, Fleisher TA, Kohler ME, Rampertaap S, et al. Acute GVHD in patients receiving IL-15/4-1BBL activated NK cells following T-cell-depleted stem cell transplantation. Blood. (2015) 125:784–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-592881

124. Shilling HG, McQueen KL, Cheng NW, Shizuru JA, Negrin RS, Parham P. Reconstitution of NK cell receptor repertoire following HLA-matched hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. (2003) 101:3730–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2568

125. Vago L, Forno B, Sormani MP, Crocchiolo R, Zino E, Di Terlizzi S, et al. Temporal, quantitative, and functional characteristics of single-KIR-positive alloreactive natural killer cell recovery account for impaired graft-versus-leukemia activity after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. (2008) 112:3488–99. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-103325

126. Fallen PR, McGreavey L, Madrigal JA, Potter M, Ethell M, Prentice HG, et al. Factors affecting reconstitution of the T cell compartment in allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2003) 32:1001–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704235

127. Ciurea SO, Mulanovich V, Saliba RM, Bayraktar UD, Jiang Y, Bassett R, et al. Improved early outcomes using a T cell replete graft compared with T cell depleted haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2012) 18:1835–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.07.003

128. Eissens DN, Schaap NP, Preijers FW, Dolstra H, van Cranenbroek B, Schattenberg AV, et al. CD3+/CD19+-depleted grafts in HLA-matched allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation lead to early NK cell cytolytic responses and reduced inhibitory activity of NKG2A. Leukemia. (2010) 24:583–91. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.269

129. Pfeiffer MM, Feuchtinger T, Teltschik HM, Schumm M, Muller I, Handgretinger R, et al. Reconstitution of natural killer cell receptors influences natural killer activity and relapse rate after haploidentical transplantation of T- and B-cell depleted grafts in children. Haematologica. (2010) 95:1381–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.021121

130. Cooley S, McCullar V, Wangen R, Bergemann TL, Spellman S, Weisdorf DJ, et al. KIR reconstitution is altered by T cells in the graft and correlates with clinical outcomes after unrelated donor transplantation. Blood. (2005) 106:4370–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1644

131. Bjorkstrom NK, Beziat V, Cichocki F, Liu LL, Levine J, Larsson S, et al. CD8 T cells express randomly selected KIRs with distinct specificities compared with NK cells. Blood. (2012) 120:3455–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-416867

132. van Bergen J, Thompson A, van der Slik A, Ottenhoff TH, Gussekloo J, Koning F. Phenotypic and functional characterization of CD4 T cells expressing killer Ig-like receptors. J Immunol. (2004) 173:6719–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6719

133. Lafarge X, Pitard V, Ravet S, Roumanes D, Halary F, Dromer C, et al. Expression of MHC class I receptors confers functional intraclonal heterogeneity to a reactive expansion of gammadelta T cells. Eur J Immunol. (2005) 35:1896–905. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425837

134. Pradier A, Papaserafeim M, Li N, Rietveld A, Kaestel C, Gruaz L, et al. Small-molecule immunosuppressive drugs and therapeutic immunoglobulins differentially inhibit NK cell effector functions in vitro. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:556. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00556

135. Schmidt S, Schubert R, Demir A, Lehrnbecher T. Distinct effects of immunosuppressive drugs on the anti-aspergillus activity of human natural killer cells. Pathogens. (2019) 8:4. doi: 10.3390/pathogens8040246

136. Sivori S, Carlomagno S, Falco M, Romeo E, Moretta L, Moretta A. Natural killer cells expressing the KIR2DS1-activating receptor efficiently kill T-cell blasts and dendritic cells: implications in haploidentical HSCT. Blood. (2011) 117:4284–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-316125

137. Wojtowicz A, Bochud PY. Risk stratification and immunogenetic risk for infections following stem cell transplantation. Virulence. (2016) 7:917–29. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1234566

138. Kao RL, Holtan SG. Host and graft factors impacting infection risk in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Infect Dis Clin North Am. (2019) 33:311–29. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.02.001

139. Cook M, Briggs D, Craddock C, Mahendra P, Milligan D, Fegan C, et al. Donor KIR genotype has a major influence on the rate of cytomegalovirus reactivation following T-cell replete stem cell transplantation. Blood. (2006) 107:1230–2. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1039

140. Gallez-Hawkins GM, Franck AE, Li X, Thao L, Oki A, Gendzekhadze K, et al. Expression of activating KIR2DS2 and KIR2DS4 genes after hematopoietic cell transplantation: relevance to cytomegalovirus infection. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2011) 17:1662–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.04.008

141. Lister J, Rybka WB, Donnenberg AD, deMagalhaes-Silverman M, Pincus SM, Bloom EJ, et al. Autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation and adoptive immunotherapy with activated natural killer cells in the immediate posttransplant period. Clin Cancer Res. (1995) 1:607–14. PubMed PMID: 9816022.

142. Burns LJ, Weisdorf DJ, DeFor TE, Repka TL, Ogle KM, Hummer C, et al. Enhancement of the anti-tumor activity of a peripheral blood progenitor cell graft by mobilization with interleukin 2 plus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients with advanced breast cancer. Exp Hematol. (2000) 28:96–103. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(99)00129-0

143. Burns LJ, Weisdorf DJ, DeFor TE, Vesole DH, Repka TL, Blazar BR, et al. IL-2-based immunotherapy after autologous transplantation for lymphoma and breast cancer induces immune activation and cytokine release: a phase I/II trial. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2003) 32:177–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704086

144. Ishikawa E, Tsuboi K, Saijo K, Harada H, Takano S, Nose T, et al. Autologous natural killer cell therapy for human recurrent malignant glioma. Anticancer Res. (2004) 24:1861–71.

145. Krause SW, Gastpar R, Andreesen R, Gross C, Ullrich H, Thonigs G, et al. Treatment of colon and lung cancer patients with ex vivo heat shock protein 70-peptide-activated, autologous natural killer cells: a clinical phase i trial. Clin Cancer Res. (2004) 10:3699–707. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0683

146. Krieger E, Sabo R, Moezzi S, Cain C, Roberts C, Kimball P, et al. Killer immunoglobulin-like receptor-ligand interactions predict clinical outcomes following unrelated donor transplantations. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2020) 26:672–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.10.016

147. Montaldo E, Del Zotto G, Della Chiesa M, Mingari MC, Moretta A, De Maria A, et al. Human NK cell receptors/markers: a tool to analyze NK cell development, subsets and function. Cytometry A. (2013) 83:702–13. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22302

148. Scoville SD, Freud AG, Caligiuri MA. Modeling human natural killer cell development in the era of innate lymphoid cells. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:360. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00360

149. Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends Immunol. (2001) 22:633–40. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(01)02060-9

150. Bjorkstrom NK, Riese P, Heuts F, Andersson S, Fauriat C, Ivarsson MA, et al. Expression patterns of NKG2A, KIR, and CD57 define a process of CD56dim NK-cell differentiation uncoupled from NK-cell education. Blood. (2010) 116:3853–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281675

151. Abel AM, Yang C, Thakar MS, Malarkannan S. Natural killer cells: development, maturation, and clinical utilization. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1869. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01869

152. Russo A, Oliveira G, Berglund S, Greco R, Gambacorta V, Cieri N, et al. NK cell recovery after haploidentical HSCT with posttransplant cyclophosphamide: dynamics and clinical implications. Blood. (2018) 131:247–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-780668

153. Foley B, Cooley S, Verneris MR, Curtsinger J, Luo X, Waller EK, et al. NK cell education after allogeneic transplantation: dissociation between recovery of cytokine-producing and cytotoxic functions. Blood. (2011) 118:2784–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-347070

154. Yu J, Venstrom JM, Liu XR, Pring J, Hasan RS, O'Reilly RJ, et al. Breaking tolerance to self, circulating natural killer cells expressing inhibitory KIR for non-self HLA exhibit effector function after T cell-depleted allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. (2009) 113:3875–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177055

155. Rathmann S, Glatzel S, Schonberg K, Uhrberg M, Follo M, Schulz-Huotari C, et al. Expansion of NKG2A-LIR1- natural killer cells in HLA-matched, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors/HLA-ligand mismatched patients following hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2010) 16:469–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.12.008

156. Moretta L, Locatelli F, Pende D, Marcenaro E, Mingari MC, Moretta A. Killer Ig-like receptor-mediated control of natural killer cell alloreactivity in haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. (2011) 117:764–71. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-264085

157. Joncker NT, Shifrin N, Delebecque F, Raulet DH. Mature natural killer cells reset their responsiveness when exposed to an altered MHC environment. J Exp Med. (2010) 207:2065–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100570

158. Elliott JM, Wahle JA, Yokoyama WM. MHC class I-deficient natural killer cells acquire a licensed phenotype after transfer into an MHC class I-sufficient environment. J Exp Med. (2010) 207:2073–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100986

159. Boudreau JE, Liu XR, Zhao Z, Zhang A, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, et al. Cell-Extrinsic MHC Class I molecule engagement augments human NK cell education programmed by cell-intrinsic MHC class I. Immunity. (2016) 45:280–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.005

160. Rogatko-Koros M, Mika-Witkowska R, Bogunia-Kubik K, Wysoczanska B, Jaskula E, Koscinska K, et al. Prediction of NK cell licensing level in selection of hematopoietic stem cell donor, initial results. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). (2016) 64(Suppl 1):63–71. doi: 10.1007/s00005-016-0438-2

161. Graczyk-Pol E, Rogatko-Koros M, Nestorowicz K, Gwozdowicz S, Mika-Witkowska R, Pawliczak D, et al. Role of donor HLA class I mismatch, KIR-ligand mismatch and HLA:KIR pairings in hematological malignancy relapse after unrelated hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. HLA. (2018) 92 Suppl 2:42–6. doi: 10.1111/tan.13386