94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Immunol. , 28 April 2020

Sec. Vaccines and Molecular Therapeutics

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00789

This article is part of the Research Topic Immunotherapies Towards HIV Cure View all 14 articles

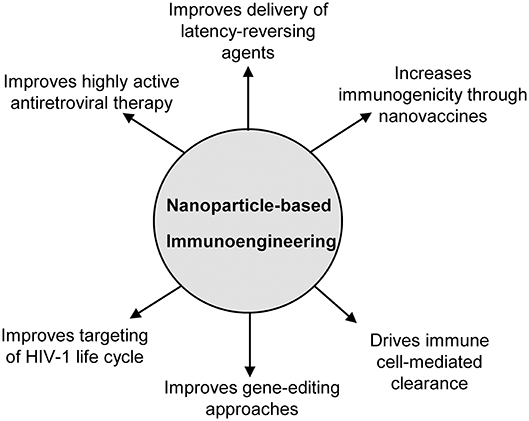

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) serves as an effective strategy to combat HIV infections by suppressing viral replication in patients with HIV/AIDS. However, HAART does not provide HIV/AIDS patients with a sterilizing or functional cure, and introduces several deleterious comorbidities. Moreover, the virus is able to persist within latent reservoirs, both undetected by the immune system and unaffected by HAART, increasing the risk of a viral rebound. The field of immunoengineering, which utilizes varied bioengineering approaches to interact with the immune system and potentiate its therapeutic effects against HIV, is being increasingly investigated in HIV cure research. In particular, nanoparticle-based immunoengineered approaches are especially attractive because they offer advantages including the improved delivery and functionality of classical HIV drugs such as antiretrovirals and experimental drugs such as latency-reversing agents (LRAs), among others. Here, we present and discuss the current state of the field in nanoparticle-based immunoengineering approaches for an HIV cure. Specifically, we discuss nanoparticle-based methods for improving HAART as well as latency reversal, developing vaccines, targeting viral fusion, enhancing gene editing approaches, improving adoptively transferred immune-cell mediated reservoir clearance, and other therapeutic and prevention approaches. Although nanoparticle-based immunoengineered approaches are currently at the stage of preclinical testing, the promising findings obtained in these studies demonstrate the potential of this emerging field for developing an HIV cure.

Approximately 37 million people worldwide are living with HIV for which there is no practical cure (1). There are two main types of the virus: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1, which is the focus of cure strategies discussed in this paper, is more prevalent and pathogenic, and primarily infects CD4+ T helper cells (2). Other cell populations susceptible to HIV-1 include dendritic cells, macrophages, microglia, and astrocytes although the mechanisms of infection for these cell types are not yet fully understood (3–8). HAART is an effective treatment regimen for HIV-1 (9), however, it allows the virus to remain viable and does not provide a sterilizing or functional cure in patients. Further HAART causes several deleterious comorbidities (10, 11). Since HAART targets the HIV-1 replication cycle, HIV-1 evades targeting by undergoing latency (12, 13). Latent HIV-1 reservoirs are also able to go undetected by the immune system, which increases the risk of a viral rebound. Another confounding factor is the lack of unique surface markers on latently infected cells, which has hindered the development of strategies to generate total viral clearance or permanent latency (14–16). This challenge is supported by the fact that there have been only two well-documented cases wherein patients have experienced total HIV-1 viral clearance. This suggests that it is extremely rare for individuals to adequately control HIV-1 without a sustained antiretroviral treatment regimen (17, 18). Hence, there is an urgent need for novel HIV cure strategies.

The field of immunoengineering encompasses a broad variety of bioengineering approaches and technologies to manipulate the immune system. A notable component of these approaches involves engineered biomaterials including nanoparticles, polymeric scaffolds, and hydrogels to engage the immune system to fight disease, and represents an attractive strategy for developing a cure for HIV-1 (19–21). While numerous nanoparticle-based immunoengineered approaches have been successfully applied in the field of cancer immunotherapy (22–26), fewer studies have utilized these promising benefits for an HIV cure. The goal of this mini-review is to familiarize the reader with the field of nanoparticle-based immunoengineering approaches for an HIV cure. In particular, we focus on the use of nanoparticles to enhance HAART, latency reversal, vaccination strategies, gene editing, cell therapies, among others (Figure 1). We highlight both immune-mediated strategies (e.g., nanoparticles in conjunction with adoptive cell transfer) and those targeting endogenous immune cells involved in HIV (e.g., nanovaccines). For a comprehensive discussion on the use of nanoparticles for treating HIV/AIDS in the context of nanoparticles classes, formulation, and their use in drug delivery, we direct the readers to several published reviews in the literature (27–29).

Figure 1. Overview of the applications of nanoparticle-based immunoengineering approaches for combating HIV-1.

Nanoparticle sizes range from ~1 to 100 nm (30). On account of their sizes, nanoparticle-based therapies can easily be administered by varied techniques (i.e., intravenously, subcutaneously, intraperitoneally) and penetrate body barriers (31). Related to their sizes and pertinent to HIV cure strategies, nanoparticles accumulate in lymphoid tissue and lymphatic organs (32), the sites of anatomical HIV reservoirs (33, 34) when parenterally injected (especially when injected intradermally, subcutaneously, and/or intramuscularly). Additionally, because nanoparticles have a large surface area-to-volume ratio, diverse molecules such as drug payloads, immunological adjuvants, and targeting ligands can be bioconjugated to their surface (35), which can then be trafficked to sites of latent HIV reservoirs. Nanoparticles can also be synthesized in the form of depots/reservoirs that encapsulate and release therapeutic drugs or immunomodulatory agents (36), allowing for their improved bioavailability and sustained release kinetics in an HIV cure setting. In the following sections, we review various examples of nanoparticles used for immunoengineering HIV cures.

HAART can successfully inactivate HIV-1, however the virus is able to persist within latent lymphoid, gut, and CNS reservoirs (5–8). This requires patients to remain adherent to the HAART regimen for the duration of their lifetime to prevent viral rebound (9). Since nanoparticles facilitate the sustained release of drugs, a group of researchers have developed a long-acting slow-effective release antiretroviral therapy (termed “LASER ART”), which utilizes nanoparticles for controlled release of HAART agents, thereby improving regimen adherence (37, 38). In a recent study, the same group of researchers demonstrated that a nanocrystallized product of lamivudine, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NM23TC), maintained antiretroviral activity in HIV-1-infected monocyte-derived macrophages after viral challenge for up to 30 days. NM23TC was taken up by HIV-1-infected monocyte-derived macrophages and remained in high prodrug concentration in whole blood for 30 days after a single dose. In addition, at day 28, M23TC, a metabolized version of lamivudine, was detected at high levels in the liver, lymph nodes, and spleen (39), suggesting that this nanoplatform may improve delivery of the drug to HIV-1 niches. Other groups have also developed nanoparticles for improving HAART (40–43) (Table 1).

Latency-reversing agents (LRAs) are able to reactivate viral replication. LRAs are used in “shock and kill” treatment approaches, wherein the LRA-elicited viral replication is coupled to the actions of HIV-1 cell-specific cytotoxic agents or immune-mediated clearance (73). Several classes of molecules and macromolecules have been used as LRAs including protein kinase C (PKC) agonists, histone deacetylase inhibitors, and cytokines, and their mechanisms of latency reversal are well-described. For example, PKC agonists function via the NF-KB pathway. Activated PKC isoforms downregulate the inhibitor IKB, thereby releasing the transcription factor NF-KB, which translocates into the nucleus, and binds to the HIV-1 proviral long terminal repeats, thereby mediating viral transcription (74). Similar to HAART, nanoparticles have been utilized to improve the delivery of LRAs (Table 1). In one study, Kovochich et al. encapsulated bryostatin, a potent PKC agonist (75) and nelfinavir, an HIV-1 protease inhibitor, into nanoparticles. Their nanoplatform targeted CD4+ cells in a peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) culture, activated latent virus, and inhibited viral spread (76). In a more recent study, Cao et al. synthesized hybrid lipid-coated PLGA nanocarriers that incorporated diverse LRAs. These lipid-coated nanoparticles could selectively activate CD4+ T cells in nonhuman primate PBMCs as well as in murine lymph nodes with substantially reduced toxicity (44). Despite the fact that it is currently impossible to identify and target every HIV-1-infected cell in the latent reservoir (45), the ability of nanoparticles and nanocarriers to traffic and deliver LRAs to sites of latent HIV reservoirs can maximize their therapeutic benefit, and serve as an important component of successful shock and kill cure regimens. Other examples of nanoparticles for improving latency reversal appear in Table 1 (46, 47).

Traditional vaccines for HIV-1 have been difficult to develop, and clinical trials using HIV-1 vaccines have demonstrated poor efficacy (77, 78). Vaccines fail for several reasons including poor delivery to dendritic cells, reversion of a live attenuated virus to its virulent form, or if the vaccine is too weak to facilitate an immune response (68). Consequently, an ideal vaccine should be clinically safe, stable, and capable of inducing a potent immune response (79). Nanoparticles have been shown to overcome these limitations (80) by protecting antigens from proteolytic enzymes, promoting antigen uptake and processing by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), in addition to being biocompatible and biodegradable (81). Several groups have leveraged favorable properties of nanoparticles to develop nanovaccines for HIV-1 (Table 1).

One effective strategy is utilizing nanovaccines to activate dendritic cells (DCs), which in turn cause T cell activation (82). To this end, Rostami et al. decorated antigens onto the surface of nanoparticles to facilitate greater interaction with the APCs due to the high surface area to volume ratio of the nanoparticles (48). Specifically, a flagellin molecule sequence derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (FLiC), a toll-like receptor 5 agonist, was conjugated to an HIV-1 p24-NeF peptide, and encapsulated within PLGA nanoparticles. The FLiC-p24-NeF-encapsulated nanoparticle elicited higher levels of lymphocyte proliferation and cytotoxic T cell activity compared to controls (48), suggesting its potential use in an HIV-1 vaccination strategy. In a more recently study by Tokatlian et al., nanoparticles encapsulating HIV-1 antigens were observe to localize to the lymph nodes more than corresponding soluble antigen counterparts, and remained localized there for up to 4 weeks (49). In another study, Lori et al. showed that their nanoplatform “DermaVir” could administer HIV-1 antigens to Langerhans cells, which resulted in a potent immunogenic response (50). DermaVir is currently undergoing a phase 3 clinical trial evaluation based on excellent responses observed in Phase I/II clinical trials (83). Together, these studies along with others summarized in Table 1 (51–56), clearly suggest the importance of nanovaccines for treating HIV-1.

Targeting the HIV replication cycle by inhibiting the ability of HIV-1 to fuse and/or enter a target cell has been the focus of several published studies (Table 1). Fusion or entry inhibition leads to inhibition of viral activity and viral cytotoxicity. In one approach, Lara et al. showed that silver nanoparticles are antiviral and prophylactic against HIV-1 fusion to target cells (57). Silver nanoparticles exert anti-HIV activity at an early stage of viral replication, likely as a virucidal agent or as an inhibitor of viral entry. Silver nanoparticles bind to gp120 in a manner that prevents CD4-dependent virion binding, fusion, and infectivity, acting as an effective virucidal agent against cell-free and cell-associated virus. Further, silver nanoparticles inhibit post-entry stages of the HIV-1 life cycle (57).

Another approach utilized semen-derived enhancer of viral infection (SEVI), which is a type of amyloid fibril present in human semen that enhances HIV-1 infection of target cells by capturing HIV-1 virions, resulting in increased viral fusion (84). SEVI serves as a mediator for HIV-1 viral attachment due to its highly cationic nature (84, 85). In their study, Sheik et al., synthesized a hydrophobic polymeric nanoparticle to reduce SEVI fibril-mediated infection (58). The hydrophobicity of the nanoparticle interferes with Aβ amyloid structure, forming amorphous aggregates, thereby disrupting the amyloid HIV-1 trafficking protein to target cells (86–88). Thus, the hydrophobic nanoparticles were able to reduce HIV-1 virion binding affinity toward their target cells (58).

Biomimicry approaches, such as plasma membrane-coated nanoparticles, represent a unique strategy to target a variety of human pathologies (89). A pivotal study showed the efficacy of coating a nanoparticle with a cell membrane to imitate and model endogenous cell activity. HIV-1 infection begins when an exposed HIV-1 surface protein, gp120, interacts with CD4 receptor and chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) co-receptor on target cells (90). Wei et al. coated polymeric nanoparticles with a CD4+ T cell membrane, causing the modified membrane-coated nanoparticle to preferentially interact with HIV-1. This preferential binding ultimately neutralized HIV-1 viral activity in PBMCs in vitro (59), illustrating the potential of biomimicking nanoparticle approaches to reduce HIV-1 viral spread by blocking viral fusion to T cells.

Unlike synthetic nanoparticles, extracellular vesicles (EVs) are naturally occurring nanoscale structures that carry cargo (e.g., proteins, lipids, nucleic acids) and can be released from both healthy and apoptotic cells (91). Recently, Palomino et al. discovered that EVs released by Lactobacillus in the healthy vaginal microbiota prevented HIV-1 attachment to target cells and thereby inhibited HIV-1 infection (60). In a recent study by Welch et al., EVs extracted from semen inhibited HIV-1 in vitro regardless of HIV infection status of the donor, while EVs extracted from the blood and semen of ART-treated subjected inhibited HIV-1 in vivo (61). These studies suggest a potential avenue for bacterial and/or EV-based treatment strategies in preventing HIV-1 viral spread.

Gene therapy technologies have been explored for HIV-1 cure strategies (Table 1). Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR-Cas9) is a gene editing platform wherein genes can be added, removed, or altered at given genetic loci (92). CRISPR-Cas9 is a faster and more efficient technique than other genetic editing platforms using other viral vectors or the Cre-Lox system, although current CRISPR-Cas9 delivery techniques use electroporation to facilitate DNA entry into living cells, which is difficult to control and can generate cytotoxicity (92, 93). Previously, gene-editing tools have knocked out CCR5 in CD4+ T cells to block HIV-1 viral entry (94, 95). However, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) have a unique ability to safely deliver CRISPR-Cas9 components to their targets (96). AuNPs have large surface area to volume ratios and are biocompatible with low toxicity (5). Shahbazi et al. developed AuNPs with layer-by-layer surface conjugation of CRISPR components (AuNP/CRISPR), targeting two locations within the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) genome, CCR5 and the gamma-globin gene promoter. Genetic deficiency in CCR5 is linked to HIV-1 resistance through the elimination of viral anchoring and entry through its CCR5 co-receptor (62, 97). AuNP/CRISPR was able to penetrate into CD34+ hematopoietic cell line, which is difficult to transfect. At micromolar concentrations, AuNP/CRISPR exhibited an overall low amount of gene editing and homologous directed repair (HDR) at the CCR5 and the gamma-globin promoter locus. This demonstrates that AuNP/CRISPR functioned with low efficacy. However, genetic editing and HDR via AuNP/CRISPR was higher than the electroporation-driven process. This suggests that AuNP/CRISPR could be effective in delivering gene editing for HIV-1 therapy (62).

With the promising innovations of LASER ART and CRISPR-Cas9, Dash et al. combined the two methodologies to evaluate a potentially synergistic functionality. Two of seven HIV-1-infected mice that received LASER ART followed by subsequent AAV9-CRISPR-Cas9 treatment targeting a fragment of the HIV-1 genome were cured of viral rebound and experienced a restoration of their CD4+ T cells, suggesting HIV-1 regression/elimination (63). Additionally, HIV-1 RNA levels diminished to undetectable levels in the plasma, spleen, liver, gut, and brain in the cured mice. Further, naïve humanized mice that were challenged with adoptively transferred cells isolated from the cured mice showed no detectable HIV-1 viral loads. This study demonstrates the possibility of eliminating HIV-1 in plasma and infectious tissues through this novel combination approach (63).

Recent studies show promising effects of cell therapies for treating HIV-1 (98–100). Here, autologous or allogenic immune cells are transferred to the patient after ex vivo expansion and/or modification to clear HIV-1 infected cells. Nanoparticles may offer the ability to enhance the ability of immune cells to target and kill target cells in the context of HIV-1. In their study, Sweeney et al. generated a PLGA nanoplatform that co-encapsulated an LRA and a target cell-specific antibody to improve NK cell effector function in an in vitro cell model of latent HIV-1 (64). The nanoplatform was able to increase NK cell cytotoxicity of the target cells, thereby illustrating an example of nanoparticles enhancing immune cell function in the context of latent HIV-1 (64). In another studies, Jones et al. demonstrated that cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) were made more potent by conjugating drug-loaded lipid nanoparticles to their surface (65). HIV-1-specific CTLs were able to specifically target HIV-1-infected cells and deliver the nanoparticle-encapsulated payload (65).

HIV-1, like many other viruses, has evolved mechanisms to evade or disrupt immune surveillance. Therefore, one strategy to eliminate HIV-1 viral load is to reverse immune evasion. HIV-1 typically inhibits the cGAS-STING pathway that normally functions via cGAMP binding to STING on the endoplasmic reticulum resulting in an IFN-1-mediated antiviral response (66, 101, 102). pH-sensitive polymeric nanoparticles were engineered to deliver a STING agonist to counteract HIV-1 immune evasion via the cGAS-STING pathway. These STING agonist-nanoparticles demonstrated potent antiretroviral activity for up to 12 days (66).

Quantum dots are biocompatible semiconductor crystal nanoparticles with low toxicity that have been used for biosensing, image contrast, and drug delivery (103, 104). These nanomaterials are attractive due to their intrinsic antiviral activity and thus, their potential as inhibitors of HIV-1. In a proof-of-concept study by Iannazzo et al., a reverse transcriptase inhibitor (RTI; CHI499) was readily conjugated onto the surface of the graphene quantum dots (GQDs) via intrinsic functional groups (67). The conjugated GQD product (GQD-CHI499) achieved remarkable anti-reverse transcriptase and cellular anti-HIV-1 activities compared to the free drug alone. This additive improvement may be the result of the GQDs' intrinsic structure, where the polycarboxylation group could mediate the inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase through viral fusion (67), suggesting the potential of GQDs in treatment for HIV-1.

Aside from persistent HIV-1 in CD4+ helper T cells, HIV-1 may also persist in microglial cells, which are the resident macrophages of the CNS (6). These cells may confer HAART resistance, perpetuate HIV-1 infection in peripheral tissues, and are critical in the development of HIV-1 associated neurocognitive diseases (105). The brain poses an anatomical barrier, where there is low drug penetration by virtue of the blood brain barrier (BBB). Therefore, there is a need to develop ways to penetrate the BBB to target persistent HIV-1 in microglial cells (6, 105). Nanodiamonds are ~10 nm diamonds which are known for their inexpensive production, surface modifications, and low cytotoxic profile. In the context of HIV-1, Roy et al. complexed efavirenz (EFV), an effective non-nucleoside RTI, to a nanodiamond to effectively improve the poor bioavailability of EFV (ND-EFV) (68). ND-EFV allowed for sustained release of EFV in a BBB model in vitro. In addition, ND-EFV was effective in controlling HIV-1 replication for 7 days, where the EFV alone drug was able to inhibit HIV-1 for 5 days (68). Similarly, gold nanoparticles have also been used entry through the BBB. Garrido et al. showed that gold nanoparticles conjugated with HIV integrase inhibitors could penetrate the BBB with antiviral efficacy, providing another nanoplatform for targeting HIV-1-infected microglial cells (69).

Another application of nanoparticles is in improving pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which provides a >90% effective approach to prevent HIV-1 infection but requires daily oral administration (106). PrEP comprises tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and emtricitabine (FTC), two nucleoside RTIs that have low half-lives and require high dosing, thereby increasing the risk of adverse effects (107). Mandal et al. encapsulated FTC within PLGA nanoparticles (FTC-NPs), and demonstrated improved bioavailability of FTC with significantly lower inhibitory concentration (IC50) than free FTC in vitro (70). Alternatively, Destache et al. loaded TDF into PLGA nanoparticles (TDF-NPs), and subsequently incorporated them within a thermosensitive vaginal gel (71). Mice challenged with two strains of HIV-1 and treated with the TDF-NP gel were 100% protected against the virus with no detectable viral plasma load (71), suggesting the efficacy of sustained release of TDF by nanoparticles via vaginal administration to prevent HIV-1 infection. In another study, Mandal et al. encapsulated dolutegravir (DTG), an integrase strand transfer inhibitor, within nanoparticles made from cellulose acetate phthalate, a pH-sensitive polymer that intrinsically inhibits HIV-1 entry into its target cells (DTG-CAP-NPs) (72). Similarly to above, DTG-CAP-NPs were incorporated into a thermosensitive vaginal gel. Vaginal epithelial cells were able to take up DTG-CAP-NPs, where they persisted for up to 7 days with low cytotoxicity (72). These studies demonstrate the potential of nanoparticles for use in HIV-1 preventative strategies, including enhancing PrEP.

Here, we have reviewed the field of nanoparticle-based immunoengineered approaches toward an HIV-1 cure. We highlighted the potential and use of nanoparticles to facilitate and improve the delivery, bioavailability, and/or functionality of HAART, LRAs, vaccines, gene-editing approaches, and other therapeutic or preventative strategies. The innovative advances described herein demonstrate the potential of the field of nanoparticle-based immunoengineering in treating and preventing HIV-1.

AB, ES, and RF all participated in the writing and the preparation of the manuscript, and approved it for publication.

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the George Washington Cancer Center and by the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21AI136102.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Jordan A, Bisgrove D, Verdin E. HIV reproducibly establishes a latent infection after acute infection of T cells in vitro. EMBO J. (2003) 22:1868–77. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg188

2. Martinez Rivas CJ, Tarhini M, Badri W, Miladi K, Greige-Gerges H, Nazari QA, et al. Nanoprecipitation process: from encapsulation to drug delivery. Int J Pharm. (2017) 532:66–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.08.064

3. Fredenberg S, Wahlgren M, Reslow M, Axelsson A. The mechanisms of drug release in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based drug delivery systems–a review. Int J Pharm. (2011) 415:34–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.05.049

4. Wiemann B, Starnes CO. Coley's toxins, tumor necrosis factor and cancer research: a historical perspective. Pharmacol Ther. (1994) 64:529–64. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)90023-X

5. Murphy CJ, Gole AM, Stone JW, Sisco PN, Alkilany AM, Goldsmith EC, et al. Gold nanoparticles in biology: beyond toxicity to cellular imaging. Acc Chem Res. (2008) 41:1721–30. doi: 10.1021/ar800035u

6. Wallet C, De Rovere M, Van Assche J, Daouad F, De Wit S, Gautier V, et al. Microglial cells: the main HIV-1 reservoir in the brain. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2019) 9:362. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00362

7. Chauveau L, Donahue DA, Monel B, Porrot F, Bruel T, Richard L, et al. HIV fusion in dendritic cells occurs mainly at the surface and is limited by low CD4 levels. J Virol. (2017) 91:e01248-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01248-17

8. Wu L, KewalRamani VN. Dendritic-cell interactions with HIV: infection and viral dissemination. Nat Rev Immunol. (2006) 6:859–68. doi: 10.1038/nri1960

9. Chesney M. Adherence to HAART regimens. Aids Patient Care St. (2003) 17:169–77. doi: 10.1089/108729103321619773

10. Sension MG. Long-Term suppression of HIV infection: benefits and limitations of current treatment options. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. (2007) 18(1 Suppl.):S2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.11.012

11. Margolis AM, Heverling H, Pham PA, Stolbach A. A review of the toxicity of HIV medications. J Med Toxicol. (2014) 10:26–39. doi: 10.1007/s13181-013-0325-8

12. Reeves DB, Duke ER, Wagner TA, Palmer SE, Spivak AM, Schiffer JT. A majority of HIV persistence during antiretroviral therapy is due to infected cell proliferation. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:4811. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06843-5

13. Richman DD, Margolis DM, Delaney M, Greene WC, Hazuda D, Pomerantz RJ. The challenge of finding a cure for HIV infection. Science. (2009) 323:1304–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1165706

14. Siliciano RF, Greene WC. HIV latency. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. (2011) 1:a007096. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007096

15. Williams SA, Chen LF, Kwon H, Ruiz-Jarabo CM, Verdin E, Greene WC. NF-kappaB p50 promotes HIV latency through HDAC recruitment and repression of transcriptional initiation. EMBO J. (2006) 25:139–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600900

16. Dahabieh MS, Battivelli E, Verdin E. Understanding HIV latency: the road to an HIV cure. Annu Rev Med. (2015) 66:407–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-092112-152941

17. Gupta RK, Abdul-Jawad S, McCoy LE, Mok HP, Peppa D, Salgado M, et al. HIV-1 remission following CCR5Delta32/Delta32 haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Nature. (2019) 568:244–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1027-4

18. Hutter G, Nowak D, Mossner M, Ganepola S, Mussig A, Allers K, et al. Long-term control of HIV by CCR5 Delta32/Delta32 stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. (2009) 360:692–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802905

19. Goldberg MS. Immunoengineering: how nanotechnology can enhance cancer immunotherapy. Cell. (2015) 161:201–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.037

20. Delcassian D, Sattler S, Dunlop IE. T cell immunoengineering with advanced biomaterials. Integr Biol (Camb). (2017) 9:211–22. doi: 10.1039/c6ib00233a

21. Xie YQ, Wei L, Tang L. Immunoengineering with biomaterials for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. (2018) 10:e1506. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1506

22. Wang C, Xu L, Liang C, Xiang J, Peng R, Liu Z. Immunological responses triggered by photothermal therapy with carbon nanotubes in combination with anti-CTLA-4 therapy to inhibit cancer metastasis. Adv Mater. (2014) 26:8154–62. doi: 10.1002/adma.201402996

23. Chen Q, Xu L, Liang C, Wang C, Peng R, Liu Z. Photothermal therapy with immune-adjuvant nanoparticles together with checkpoint blockade for effective cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. (2016) 7:13193. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13193

24. Nam J, Son S, Ochyl LJ, Kuai R, Schwendeman A, Moon JJ. Chemo-photothermal therapy combination elicits anti-tumor immunity against advanced metastatic cancer. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:1074. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03473-9

25. Sweeney EE, Cano-Mejia J, Fernandes R. Photothermal therapy generates a thermal window of immunogenic cell death in neuroblastoma. Small. (2018) 14:e1800678. doi: 10.1002/smll.201800678

26. Cano-Mejia J, Bookstaver ML, Sweeney EE, Jewell CM, Fernandes R. Prussian blue nanoparticle-based antigenicity and adjuvanticity trigger robust antitumor immune responses against neuroblastoma. Biomater Sci. (2019) 7:1875–87. doi: 10.1039/C8BM01553H

27. Mamo T, Moseman EA, Kolishetti N, Salvador-Morales C, Shi J, Kuritzkes DR, et al. Emerging nanotechnology approaches for HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention. Nanomedicine (Lond). (2010) 5:269–85. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.1

28. Victor OB. Nanoparticles and its implications in HIV/AIDS therapy. Curr Drug Discov Technol. (2019) 16:1. doi: 10.2174/1570163816666190620111652

29. Cao S, Woodrow KA. Nanotechnology approaches to eradicating HIV reservoirs. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. (2019) 138:48–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.06.002

30. International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Nanotechnologies — Vocabulary — Part 2: Nano-objects. ISO/TS 80004-2:2015 (2015).

31. Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol. (2015) 33:941–51. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3330

32. Rao DA, Forrest ML, Alani AW, Kwon GS, Robinson JR. Biodegradable PLGA based nanoparticles for sustained regional lymphatic drug delivery. J Pharm Sci. (2010) 99:2018–31. doi: 10.1002/jps.21970

33. Vanhamel J, Bruggemans A, Debyser Z. Establishment of latent HIV-1 reservoirs: what do we really know? J Virus Erad. (2019) 5:3–9.

34. Pantaleo G, Graziosi C, Butini L, Pizzo PA, Schnittman SM, Kotler DP, et al. Lymphoid organs function as major reservoirs for human immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1991) 88:9838–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9838

35. Sinha R, Kim GJ, Nie S, Shin DM. Nanotechnology in cancer therapeutics: bioconjugated nanoparticles for drug delivery. Mol Cancer Ther. (2006) 5:1909–17. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0141

36. Reis CP, Neufeld RJ, Ribeiro AJ, Veiga F. Nanoencapsulation I. Methods for preparation of drug-loaded polymeric nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. (2006) 2:8–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2005.12.003

37. Edagwa B, McMillan J, Sillman B, Gendelman HE. Long-acting slow effective release antiretroviral therapy. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. (2017) 14:1281–91. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2017.1288212

38. Gnanadhas DP, Dash PK, Sillman B, Bade AN, Lin Z, Palandri DL, et al. Autophagy facilitates macrophage depots of sustained-release nanoformulated antiretroviral drugs. J Clin Invest. (2017) 127:857–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI90025

39. Smith N, Bade AN, Soni D, Gautam N, Alnouti Y, Herskovitz J, et al. A long acting nanoformulated lamivudine ProTide. Biomaterials. (2019) 223:119476. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119476

40. Guo D, Zhou T, Arainga M, Palandri D, Gautam N, Bronich T, et al. Creation of a long-acting nanoformulated 2',3'-dideoxy-3'-thiacytidine. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2017) 74:e75–e83. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001170

41. Freeling JP, Koehn J, Shu C, Sun J, Ho RJ. Long-acting three-drug combination anti-HIV nanoparticles enhance drug exposure in primate plasma and cells within lymph nodes and blood. Aids. (2014) 28:2625–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000421

42. Prathipati PK, Mandal S, Pon G, Vivekanandan R, Destache CJ. Pharmacokinetic and tissue distribution profile of long acting tenofovir alafenamide and elvitegravir loaded nanoparticles in humanized mice model. Pharm Res. (2017) 34:2749–55. doi: 10.1007/s11095-017-2255-7

43. Kumar P, Lakshmi YS, Kondapi AK. Triple drug combination of zidovudine, efavirenz and lamivudine loaded lactoferrin nanoparticles: an effective nano first-line regimen for HIV therapy. Pharm Res. (2017) 34:257–68. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-2048-4

44. Cao S, Slack SD, Levy CN, Hughes SM, Jiang Y, Yogodzinski C, et al. Hybrid nanocarriers incorporating mechanistically distinct drugs for lymphatic CD4+ T cell activation and HIV-1 latency reversal. Sci Adv. (2019) 5:eaav6322. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav6322

45. Battivelli E, Dahabieh MS, Abdel-Mohsen M, Svensson JP, Da Silva IT, Cohn LB, et al. Distinct chromatin functional states correlate with HIV latency reactivation in infected primary CD4+ T cells. Elife. (2018) 7:e34655. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34655

46. Jayant RD, Atluri VS, Agudelo M, Sagar V, Kaushik A, Nair M. Sustained-release nanoART formulation for the treatment of neuroAIDS. Int J Nanomed. (2015) 10:1077–93. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S76517

47. Tang X, Liang Y, Liu X, Zhou S, Liu L, Zhang F, et al. PLGA-PEG nanoparticles coated with anti-CD45RO and loaded with HDAC plus protease inhibitors activate latent HIV and inhibit viral spread. Nanoscale Res Lett. (2015) 10:413. doi: 10.1186/s11671-015-1112-z

48. Rostami H, Ebtekar M, Ardestani MS, Yazdi MH, Mahdavi M. Co-utilization of a TLR5 agonist and nano-formulation of HIV-1 vaccine candidate leads to increased vaccine immunogenicity and decreased immunogenic dose: a preliminary study. Immunol Lett. (2017) 187:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2017.05.002

49. Tokatlian T, Read BJ, Jones CA, Kulp DW, Menis S, Chang JYH, et al. Innate immune recognition of glycans targets HIV nanoparticle immunogens to germinal centers. Science. (2019) 363:649–54. doi: 10.1126/science.aat9120

50. Lori F, Calarota SA, Lisziewicz J. Nanochemistry-based immunotherapy for HIV-1. Curr Med Chem. (2007) 14:1911–9. doi: 10.2174/092986707781368513

51. Jardine JG, Kulp DW, Havenar-Daughton C, Sarkar A, Briney B, Sok D, et al. HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibody precursor B cells revealed by germline-targeting immunogen. Science. (2016) 351:1458–63. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9195

52. Martinez-Murillo P, Tran K, Guenaga J, Lindgren G, Adori M, Feng Y, et al. Particulate array of well-ordered HIV clade C env trimers elicits neutralizing antibodies that display a unique V2 cap approach. Immunity. (2017) 46:804–17.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.021

53. Sliepen K, Han BW, Bontjer I, Mooij P, Garces F, Behrens AJ, et al. Structure and immunogenicity of a stabilized HIV-1 envelope trimer based on a group-M consensus sequence. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:2355. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10262-5

54. Brouwer PJM, Antanasijevic A, Berndsen Z, Yasmeen A, Fiala B, Bijl TPL, et al. Enhancing and shaping the immunogenicity of native-like HIV-1 envelope trimers with a two-component protein nanoparticle. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:4272. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12080-1

55. Dubrovskaya V, Tran K, Ozorowski G, Guenaga J, Wilson R, Bale S, et al. Vaccination with glycan-modified HIV NFL envelope trimer-liposomes elicits broadly neutralizing antibodies to multiple sites of vulnerability. Immunity. (2019) 51:915–29.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.10.008

56. He L, de Val N, Morris CD, Vora N, Thinnes TC, Kong L, et al. Presenting native-like trimeric HIV-1 antigens with self-assembling nanoparticles. Nat Commun. (2016) 7:12041. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12041

57. Lara HH, Ayala-Nunez NV, Ixtepan-Turrent L, Rodriguez-Padilla C. Mode of antiviral action of silver nanoparticles against HIV-1. J Nanobiotechnology. (2010) 8:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-8-1

58. Sheik DA, Chamberlain JM, Brooks L, Clark M, Kim YH, Leriche G, et al. Hydrophobic nanoparticles reduce the β-sheet content of SEVI amyloid fibrils and inhibit SEVI-enhanced HIV infectivity. Langmuir. (2017) 33:2596–602. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b04295

59. Wei X, Zhang G, Ran D, Krishnan N, Fang RH, Gao W, et al. T-cell-mimicking nanoparticles can neutralize HIV infectivity. Adv Mater. (2018) 30:e1802233. doi: 10.1002/adma.201802233

60. Nahui Palomino RA, Vanpouille C, Laghi L, Parolin C, Melikov K, Backlund P, et al. Extracellular vesicles from symbiotic vaginal lactobacilli inhibit HIV-1 infection of human tissues. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:5656. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13468-9

61. Welch JL, Kaddour H, Winchester L, Fletcher CV, Stapleton JT, Okeoma CM. Semen extracellular vesicles from HIV-1-infected individuals inhibit HIV-1 replication in vitro, and extracellular vesicles carry antiretroviral drugs in vivo. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2020) 83:90–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002233

62. Shahbazi R, Sghia-Hughes G, Reid JL, Kubek S, Haworth KG, Humbert O, et al. Targeted homology-directed repair in blood stem and progenitor cells with CRISPR nanoformulations. Nat Mater. (2019) 18:1124–32. doi: 10.1038/s41563-019-0385-5

63. Dash PK, Kaminski R, Bella R, Su H, Mathews S, Ahooyi TM, et al. Sequential LASER ART and CRISPR treatments eliminate HIV-1 in a subset of infected humanized mice. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:2753. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10366-y

64. Sweeney EEBP, Balakrishnan PB, Powell AB, Bowen A, Sarabia I, Burga RA, et al. PLGA nanodepots co-encapsulating prostratin and anti-CD25 enhance primary natural killer cell antiviral and antitumor function. Nano Res. (2020) 13:736–44. doi: 10.1007/s12274-020-2684-1

65. Jones RB, Mueller S, Kumari S, Vrbanac V, Genel S, Tager AM, et al. Antigen recognition-triggered drug delivery mediated by nanocapsule-functionalized cytotoxic T-cells. Biomaterials. (2017) 117:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.11.048

66. Aroh C, Wang ZH, Dobbs N, Luo M, Chen ZJ, Gao JM, et al. Innate immune activation by cGMP-AMP nanoparticles leads to potent and long-acting antiretroviral response against HIV-1. J Immunol. (2017) 199:3840–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700972

67. Iannazzo D, Pistone A, Ferro S, De Luca L, Monforte AM, Romeo R, et al. Graphene quantum dots based systems as HIV inhibitors. Bioconjugate Chem. (2018) 29:3084–93. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00448

68. Roy U, Drozd V, Durygin A, Rodriguez J, Barber P, Atluri V, et al. Characterization of nanodiamond-based anti-HIV drug delivery to the brain. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:1063. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16703-9

69. Garrido C, Simpson CA, Dahl NP, Bresee J, Whitehead DC, Lindsey EA, et al. Gold nanoparticles to improve HIV drug delivery. Future Med Chem. (2015) 7:1097–107. doi: 10.4155/fmc.15.57

70. Mandal S, Belshan M, Holec A, Zhou Y, Destache CJ. An enhanced emtricitabine-loaded long-acting nanoformulation for prevention or treatment of HIV infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2017) 61:e01475-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01475-16

71. Destache CJ, Mandal S, Yuan Z, Kang GB, Date AA, Lu WX, et al. Topical tenofovir disoproxil fumarate nanoparticles prevent HIV-1 vaginal transmission in a humanized mouse model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2016) 60:3633–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00450-16

72. Mandal S, Khandalavala K, Pham R, Bruck P, Varghese M, Kochvar A, et al. Cellulose acetate phthalate and antiretroviral nanoparticle fabrications for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. Polymers-Basel. (2017) 9:423–40. doi: 10.3390/polym9090423

74. Spivak AM, Planelles V. Novel latency reversal agents for HIV-1 cure. Annu Rev Med. (2018) 69:421–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-052716-031710

75. Qatsha KA, Rudolph C, Marme D, Schachtele C, May WS. Go-6976, a selective inhibitor of protein-kinase-C, is a potent antagonist of human immunodeficiency virus-1 induction from latent low-level-producing reservoir cells-in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1993) 90:4674–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4674

76. Kovochich M, Marsden MD, Zack JA. Activation of latent HIV using drug-loaded nanoparticles. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e18270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018270

77. Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, Fitzgerald DW, Mogg R, Li D, et al. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the step study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet. (2008) 372:1881–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3

78. Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, Zolla-Pazner S, Tomaras GD, Alam SM, et al. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N Engl J Med. (2012) 366:1275–86.

80. Zaman M, Good MF, Toth I. Nanovaccines and their mode of action. Methods. (2013) 60:226–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.04.014

81. Lopez-Sagaseta J, Malito E, Rappuoli R, Bottomley MJ. Self-assembling protein nanoparticles in the design of vaccines. Comput Struct Biotec. (2016) 14:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2015.11.001

82. Huleatt JW, Jacobs AR, Tang J, Desai P, Kopp EB, Huang Y, et al. Vaccination with recombinant fusion proteins incorporating toll-like receptor ligands induces rapid cellular and humoral immunity. Vaccine. (2007) 25:763–75. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.013

83. Rodriguez B, Asmuth DM, Matining RM, Spritzler J, Jacobson JM, Mailliard RB, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of repeated doses of dermavir, a candidate therapeutic HIV vaccine, in HIV-infected patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapy: results of the ACTG 5176 trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2013) 64:351–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a99590

84. Ren RX, Yin SW, Lai BL, Ma LZ, Wen JY, Zhang XX, et al. Myricetin antagonizes semen-derived enhancer of viral infection (SEVI) formation and influences its infection-enhancing activity. Retrovirology. (2018) 15:49. doi: 10.1186/s12977-018-0432-3

85. Roan NR, Munch J, Arhel N, Mothes W, Neidleman J, Kobayashi A, et al. The cationic properties of SEVI underlie its ability to enhance human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. (2009) 83:73–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01366-08

86. Capule CC, Yang J. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-based method to quantify the association of small molecules with aggregated amyloid peptides. Anal Chem. (2012) 84:1786–91. doi: 10.1021/ac2030859

87. Giacomelli CE, Norde W. Conformational changes of the amyloid β-peptide (1-40) adsorbed on solid surfaces. Macromol Biosci. (2005) 5:401–7. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200400189

88. Moores B, Drolle E, Attwood SJ, Simons J, Leonenko Z. Effect of surfaces on amyloid fibril formation. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e25954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025954

89. Hu CM, Zhang L, Aryal S, Cheung C, Fang RH, Zhang L. Erythrocyte membrane-camouflaged polymeric nanoparticles as a biomimetic delivery platform. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:10980–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106634108

90. Campbell EM, Hope TJ. HIV-1 capsid: the multifaceted key player in HIV-1 infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2015) 13:471–83. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3503

91. Yanez-Mo M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, Zavec AB, Borras FE, Buzas EI, et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. (2015) 4:27066. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.27066

92. Ma Y, Zhang L, Huang X. Genome modification by CRISPR/Cas9. FEBS J. (2014) 281:5186–93. doi: 10.1111/febs.13110

93. Lino CA, Harper JC, Carney JP, Timlin JA. Delivering CRISPR: a review of the challenges and approaches. Drug Deliv. (2018) 25:1234–57. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2018.1474964

94. Li C, Guan X, Du T, Jin W, Wu B, Liu Y, et al. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection of primary CD4+ T-cells by gene editing of CCR5 using adenovirus-delivered CRISPR/Cas9. J Gen Virol. (2015) 96:2381–93. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000139

95. Xu L, Yang H, Gao Y, Chen Z, Xie L, Liu Y, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated CCR5 ablation in human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells confers HIV-1 resistance in vivo. Mol Ther. (2017) 25:1782–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.04.027

96. Lee B, Lee K, Panda S, Gonzales-Rojas R, Chong A, Bugay V, et al. Nanoparticle delivery of CRISPR into the brain rescues a mouse model of fragile X syndrome from exaggerated repetitive behaviours. Nat Biomed Eng. (2018) 2:497–507. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0252-8

97. Lopalco L. CCR5: from natural resistance to a new anti-HIV strategy. Viruses. (2010) 2:574–600. doi: 10.3390/v2020574

98. Lam S, Bollard C. T-cell therapies for HIV. Immunotherapy. (2013) 5:407–14. doi: 10.2217/imt.13.23

99. Patel S, Jones RB, Nixon DF, Bollard CM. T-cell therapies for HIV: preclinical successes and current clinical strategies. Cytotherapy. (2016) 18:931–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.04.007

100. Sung JA, Patel S, Clohosey ML, Roesch L, Tripic T, Kuruc JD, et al. HIV-Specific, ex vivo expanded T cell therapy: feasibility, safety, and efficacy in ART-suppressed HIV-infected individuals. Mol Ther. (2018) 26:2496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.08.015

101. Yan N, Regalado-Magdos AD, Stiggelbout B, Lee-Kirsch MA, Lieberman J. The cytosolic exonuclease TREX1 inhibits the innate immune response to human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Nat Immunol. (2010) 11:1005–U53. doi: 10.1038/ni.1941

102. Gao DX, Wu JX, Wu YT, Du FH, Aroh C, Yan N, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is an innate immune sensor of HIV and other retroviruses. Science. (2013) 341:903–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1240933

103. Mansur HS. Quantum dots and nanocomposites. Wires Nanomed Nanobi. (2010) 2:113–29. doi: 10.1002/wnan.78

104. Matea CT, Mocan T, Tabaran F, Pop T, Mosteanu O, Puia C, et al. Quantum dots in imaging, drug delivery and sensor applications. Int J Nanomed. (2017) 12:5421–31. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S138624

105. Garrido C, Margolis DM. Translational challenges in targeting latent HIV infection and the CNS reservoir problem. J Neurovirol. (2015) 21:222–6. doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0269-z

106. Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, Buchbinder S, Lama JR, Guanira JV, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Trans Med. (2012) 4:151ra125. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004006

Keywords: HIV cure strategies, immunoengineering, nanoparticles, immune activation, HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy), combination therapy for HIV, latency reversing agents

Citation: Bowen A, Sweeney EE and Fernandes R (2020) Nanoparticle-Based Immunoengineered Approaches for Combating HIV. Front. Immunol. 11:789. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00789

Received: 03 February 2020; Accepted: 07 April 2020;

Published: 28 April 2020.

Edited by:

Carolina Garrido, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United StatesReviewed by:

Darrell Irvine, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Bowen, Sweeney and Fernandes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rohan Fernandes, cmZlcm5hbmRlc0Bnd3UuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.