- 1Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Animal Cells and Developmental Biology, School of Life Science, Shandong University, Qingdao, China

- 2State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology, Shandong University, Qingdao, China

- 3Laboratory for Marine Biology and Biotechnology, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao, China

A small open reading frame (smORF) or short open reading frame (sORF) encodes a polypeptide of <100 amino acids in eukaryotes (50 amino acids in prokaryotes). Studies have shown that several sORF-encoded peptides (SEPs) have important physiological functions in different organisms. Many ribosomal proteins belonging to SEPs play important roles in several cellular processes, such as DNA damage repair and apoptosis. Several studies have implicated SEPs in response to infection and innate immunity, but the mechanisms have been unclear for most of them. In this study, we identified a sORF-encoded ribosomal protein S27 (RPS27) in Marsupenaeus japonicus. The expression of MjRPS27 was significantly upregulated in shrimp infected with white spot syndrome virus (WSSV). After knockdown of MjRPS27 by RNA interference, WSSV replication increased significantly. Conversely, after MjRPS27 overexpression, WSSV replication decreased in shrimp and the survival rate of the shrimp increased significantly. These results suggested that MjRPS27 inhibited viral replication. Further study showed that, after MjRPS27 knockdown, the mRNA expression level of MjDorsal, MjRelish, and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) decreased, and the nuclear translocation of MjDorsal and MjRelish into the nucleus also decreased. These findings indicated that MjRPS27 might activate the NF-κB pathway and regulate the expression of AMPs in shrimp after WSSV challenge, thereby inhibiting viral replication. We also found that MjRPS27 interacted with WSSV's envelope proteins, including VP19, VP24, and VP28, suggesting that MjRPS27 may inhibit WSSV proliferation by preventing virion assembly in shrimp. This study was the first to elucidate the function of the ribosomal protein MjRPS27 in the antiviral immunity of shrimp.

Introduction

A small open reading frame (smORF) or short open reading frame (sORF) encodes polypeptides of <100 amino acids in eukaryotes (1). SmORFs can encode functional polypeptides, designated as smORF-encoded polypeptides (SEPs or micropeptides), or act as cis-translational regulators (2). Hundreds and thousands of smORF sequences are found in eukaryotic genomes (3). One of the differences between smORF and a traditional ORF is the length of the DNA sequence, i.e., the traditional ORF usually exceeds 100 codons. The second difference is that smORF-encoded SEPs do not need to undergo protease hydrolysis and play direct physiological roles, whereas a traditional peptide, such as an 180 amino acid pre-glucagon, must undergo protease hydrolysis to become the biologically active glucagon (with 29 amino acids) (4, 5).

smORFs play important roles in many fundamental biological processes in human cells, animals, plants, and bacteria (6–8). For example, a new smORF–sarcolamban gene identified in Drosophila encodes two novel functional SEPs, namely a 28- and a 29-amino acid peptide homologous to the mammalian 30-amino acid polypeptide of muscle lipoprotein and the 52-amino acid phosphoprotein (9–11). Sarcolamban regulates calcium signaling and muscle contraction. Loss of sarcolamban leads to arhythmia, but its overexpression can lead to increased heart rate in Drosophila (9). A smORF-encoded myoregulin (MLN) is a homolog of myosin and phosphoprotein. It can interact with SERCA, the membrane pump that controls muscle relaxation by regulating Ca2+ uptake into the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Mice lacking MLN have higher endurance than wild-type mice and can travel farther, suggesting that MLN is an important regulator of skeletal muscle physiology (12). Several reports have implicated SEPs in response to infection and innate immunity. For example, Jackson et al. (13) found that the translation of a new ORF “hidden” within the long noncoding RNA Aw112010 can control mucosal immunity during both bacterial infection and colitis. Virus infection of human lung cancer cells induced 19 novel smORFs in noncoding RNAs either up- or downregulated during infection, suggesting that these smORFs may be immune regulators involved in the antiviral process (14).

Ribosome protein S27 (RPS27) belongs to the 40S subunit of ribosome, also called metallopanstimulin-1 (MPS-1) protein. RPS27 was identified as a growth-factor-inducible gene and encodes an 84-amino acid (9.5 kDa) protein with a zinc finger motif (15–17). Many studies show that some ribosomal proteins have other functions in addition to protein synthesis (18). For example, the ribosomal protein L13a participates in the formation of the complex respiratory syncytial virus-activated inhibitor of translation during respiratory syncytial virus infection, thereby acting as an antiviral agent (19). Ribosomal protein L11 and L23 interact with HDM2 (the human counterpart of murine double minute two gene), and this interaction inhibits the E3 ligase function of HDM2 and stabilizes and activates p53 (20–22). Recent studies have shown that RPS27/MPS-1 is overexpressed in 86% of gastric cancer tissues, and its overexpression is related to tumor nodule metastasis. In gastric cancer cells, the expression of RPS27/MPS-1 affects the NF-κB pathway of gastric cancer cells (23). However, current reports about the function of RPS27 are mostly on human cancers, and reports on other functions are few.

In shrimp, The NF-κB pathways [Toll and immune deficiency (IMD) pathways] play important roles in innate immunity (24, 25). After pathogen infection, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) recognize the pathogen-associated molecular patterns of invading pathogens and activate NF-κB pathways (Toll and IMD pathways). Consequently, the expression of specific genes regulated by the pathways, such as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and C-type lectins, are increased to defend against pathogen invasion (26–29).

White spot syndrome virus (WSSV) is one of the most prevalent, widespread, and lethal viruses and causes great losses in the shrimp aquaculture industry (30). Understanding the molecular mechanism between host–pathogen interactions will contribute significantly to the treatment of this pathogen. In the present study, we identified a sORF-encoded polypeptide, ribosome protein S27, in kuruma shrimp (Marsupenaeus japonicus) and denoted it as MjRPS27. We found that MjRPS27 was upregulated in shrimp challenged by white spot syndrome virus (WSSV). RNA interference and overexpression analysis revealed that MjRPS27 had an antiviral function. The possible underlying mechanism was studied.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Materials

Kuruma shrimp Marsupenaeus japonicus (8–10 g each) were purchased from the fish market in Jinan and Qingdao, Shandong Province, and cultured in a circulating aquaculture system filled with natural seawater before the experiments. The preparation of WSSV inoculum and quantification of viral copy numbers of the inoculum followed our previously described methods (31).

Viral Challenge and Tissue Collection

Shrimp were randomly divided into two groups (30 shrimp each) for the challenge experiment. One group was intramuscularly injected with 50 μL of WSSV (5 × 107 copies/shrimp) at the penultimate segment of shrimp using a microsyringe, and another group was injected with the same amount of PBS (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.8 mM KH2PO4; pH 7.4) as a control. Different organs (heart, hepatopancreas, gills, stomach, and intestine) and total hemocytes were collected from shrimp at different time points (0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h post injection) for RNA extraction. For hemocytes collection, shrimp hemolymph was extracted using a 5 mL syringe preloaded with anticoagulant (0.45 M NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM EDTA, and 10 mM HEPES; pH 7.45) beforehand at 1:1 hemolymph/anticoagulan ratio. After centrifugation at 800 × g for 6 min at 4°C, hemocytes were collected and used to extract RNA or protein for tissue distribution and expression pattern analysis. At least three shrimp were used for a tissue collection.

RNA Extraction and cDNA Reverse Transcription

The different organs collected from viral-challenged or control shrimp were homogenized on ice with 1 mL of Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The collected hemocytes were suspended with Trizol reagent. All homogenates of different organs and hemocytes were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to collect the supernatant, which was placed in a new 1.5 mL RNase-free centrifuge tube. After adding 200 μL of chloroform to the supernatant, thorough mixing, and centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was collected. Then, after adding 500 μL of isopropanol to the supernatant, the resulting solution was mixed well and placed on ice for 10 min to precipitate the RNA. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, RNA precipitates were collected, washed once with 70% ethanol, and dried on a clean bench.

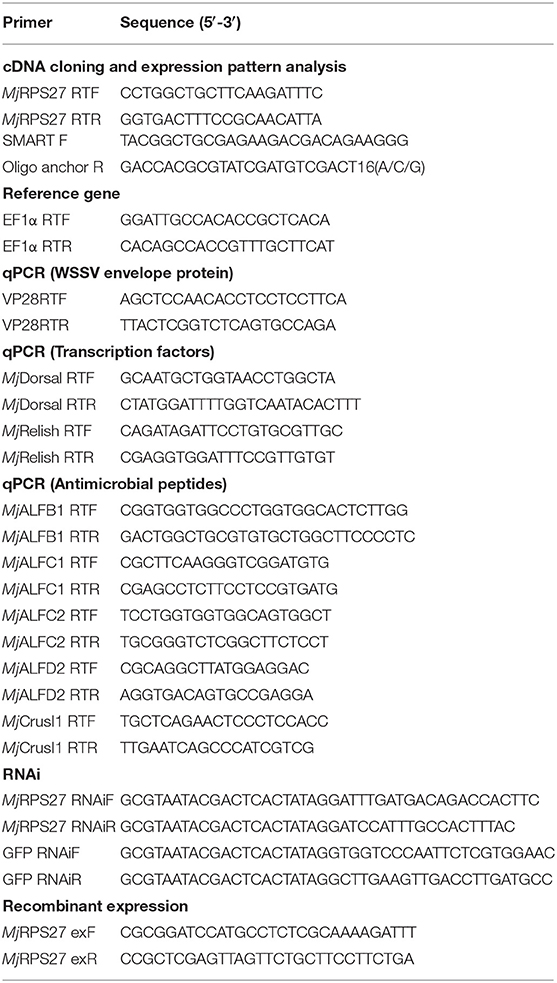

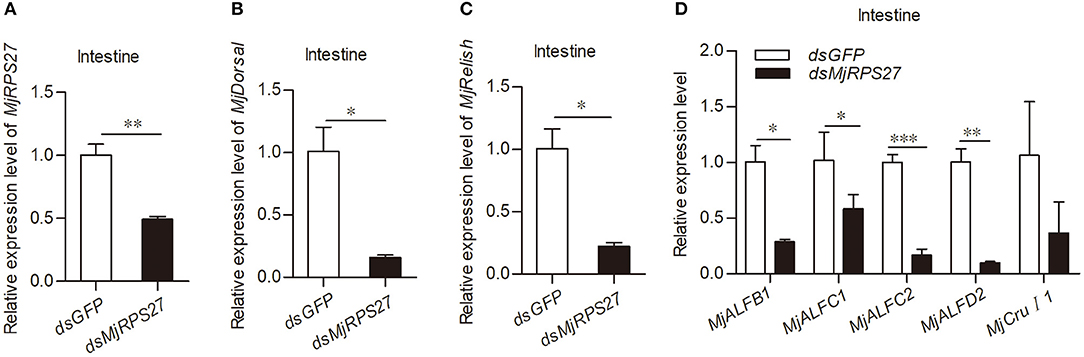

cDNA was synthesized with a Smart cDNA synthesis kit (Takara, Dalian, China) with primers SMART F and Oligo anchor R (Table 1). A mixture of total RNA (5 μg of RNA in 9 μL of RNase-free water) and SMART F and Oligo anchor R primers (1 μL each) (Table 1) was incubated at 70°C for 5 min before placing in an ice bath. Then, 11 μL of the mixture was mixed with 1 μL of Power M-MLV (Bioteke, Beijing, China), 4 μL of 5 × first-strand cDNA buffer, 0.5 μL of RNase Inhibitor (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), 2 μL of dNTP mix solution (GENERAY, Shanghai, China), and 1.5 μL of RNase free water (total volume = 20 μL). cDNA was synthesized at 42°C for 1 h. At the end of cDNA synthesis, the reaction system was incubated at 70°C for 10 min to end the reaction. The obtained cDNA was used for subsequent experiments.

cDNA Cloning and Phylogenetic Analysis

The sequence of MjRPS27 was obtained from the hemocyte transcriptome sequencing of M. japonicus. The sequence was amplified by RT-PCR with primers MjRPS27 exF and exR (Table 1) and confirmed by resequencing. The confirmed sequence was analyzed at the blastx website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and its protein sequence was predicted with ExPASy-Traslate tool (https://web.expasy.org/translate/). The obtained protein sequence was analyzed with the ExPASy-Compute pI/Mw tool (https://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/). GENEDOC and MEGA5 were used for sequence alignment and phylogenetic-tree analysis, respectively.

Tissue Distribution and Expression-Pattern Analysis

The tissue distribution of MjRPS27 in shrimp was detected using semiquantitative RT-PCR with primers MjRPS27 RTF and MjRPS27 RTR (Table 1). The PCR profile was as follows: 94°C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 56°C for 20 s, 72°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 10 min. EF1α was used as an internal control. The DNA fragment obtained after PCR was detected by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Quantitative real-time RCR (qPCR) was used to analyze the expression patterns of MjRPS27 at different time points after WSSV challenge with primers MjRPS27 RTF and MjRPS27 RTR (Table 1). The PCR profile was as follows: 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 50 s, and read at 72°C for 2 s, and then a melt period from 65 to 95°C. PCR data were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method and expressed as the mean ± SD. Student's t-test was used to analyze the significant differences among PCR data, and significant difference was accepted at p < 0.05.

RNA Interference Assay

Double-stranded RNA synthesis and RNA Interference (RNAi) assay were both conducted as in our previous report (32). In a typical procedure, the software Primer Premier 5 was used to design the RNA interference primers of MjRPS27 (Table 1). Simultaneously, GFP RNAiF and RNAiR were used to amplify the dsGFP fragment as a control (Table 1). First, a partial MjPRS27 cDNA fragment was amplified by PCR with primers (MjRPS27 RNAiF and MjRPS27 RNAiR) linked to the T7 promoter sequence (Table 1) using for the template for dsRNA synthesis. The PCR profile for the template amplification was 94°C for 3 min, 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, 72°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 10 min. The PCR product was extracted using phenol–chloroform and was used as a template to synthesize dsRNA with an in vitro T7 Transcription Kit (Takara Bio, Dalian, China). The synthesis procedure of dsRNA was performed following manufacturer's instruction. The synthesized dsRNA was first extracted with phenol–chloroform, and the concentration was detected using a micro-spectrophotometer K5500 (K.O., China).

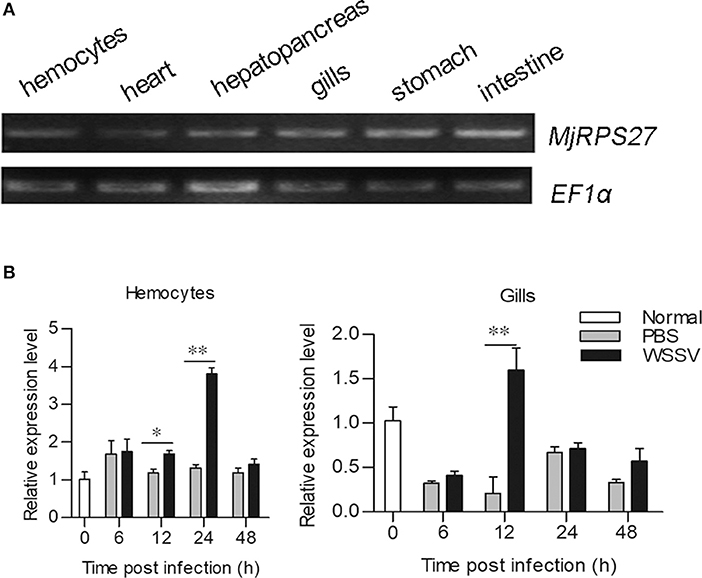

To test whether the expression of MjRPS27 could be suppressed, we injected different amounts of dsRNA (40, 80, and 100 μg) into shrimp at the penultimate somite, and an equal amount of GFP dsRNA injection was used as the control. At 48 h post injection, the MjRPS27 expression in gills and intestine was analyzed by qPCR to confirm the RNA interference (RNAi) efficiency. At least three shrimp were used for testing the RNAi efficiency.

After validating that MjRPS27 expression could be silenced by the dsRNA injection, the RNAi assay was performed. Shrimp were randomly divided into two groups (30 individuals for each group). DsRNA (80 μg) was intramuscularly injected at the penultimate somite of shrimp, and the same amount of dsGFP was injected as a control. After 48 h of dsRNA injection, the WSSV (5 × 107 copies/shrimp) were injected into shrimp of the two groups at the penultimate segment of shrimp with a microsyringe. WSSV replication in gills and intestines was analyzed by qPCR (using VP28 expression as an indicator) 24 h post-WSSV injection using the primers VP28 RTF and VP28 RTR.

Recombinant Expression and Purification of MjRPS27

MjRPS27 exF and MjRPS27 exR (Table 1) were used to amplify MjRPS27 by RT-PCR. The PCR product and empty plasmid pGEX4T-2 (GE Healthcare) were digested by two restriction endonucleases, BamHI and XhoI (Thermo Scientific), at 37°C for 1 h (MjRPS27) and 37°C for 0.5 h (vector pGEX4T-2). The obtained fragments and the pGEX4T-2 plasmids ligated with T4 DNA ligase (Thermo Fisher) to construct the recombinant plasmid pGEX4T-2/MjRPS27. The constructed recombinant plasmid was then transformed into E. coli DH5α cells, cultured at 37°C overnight. The recombinant plasmid, purified from the E. coli DH5α, was transformed into E. coli Rosetta cells, and MjRPS27 expression was induced with β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Sangon, Shanghai, China) at a final concentration of 0.5 mM at 37°C. Rosetta bacteria were collected and disrupted with ultrasonic waves. The crushed bacterial solution was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant and precipitate were collected and analyzed by sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The recombinant protein was purified by GST-resin chromatography (GenScript, Nanjing, China) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Pulldown Assay

To analyze the interaction of MjRPS27 with WSSV envelope proteins, a pulldown assay was performed. MjRPS27 with GST tag, GST tag protein, and four types of WSSV envelope proteins (VP19, VP24, VP26, and VP28) with His tag were expressed in E. coli using our previously constructed plasmid (33). Recombinant MjRPS27 and different envelope proteins (100 μg) were mixed and incubated at 4°C overnight. Then, 100 μL of glutathione-Sepharose was added to the mixture and incubated at 4°C for 40 min. The mixture (resin and binding proteins) was washed six times with PBS by centrifugation at 500 × g for 3 min to remove the unbound proteins. The interacting proteins were eluted by 50 μL of GST elution buffer (10 mM glutathione, pH 8.0), and the eluted solution was subjected to Western blot analysis.

Western Blot Assay

Previously obtained samples were mixed with 25 μL of sodium dodecylsulfate loading buffer and subjected to 12.5% SDS-PAGE analysis following the Laemmli method (34). The proteins in the SDS-PAGE gel were electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (pore size = 0.45 μm). Non-fat dry milk was dissolved in TBS (10 mM Tris-HCl and 150 mM NaCl; pH 8.0), and the 3% non-fat dry milk solution was placed on the blocking membrane. After incubation at room temperature for 1 h, the blocking solution was discarded and the primary antibody (against His tag or GST tag; Zhongshan, Beijing, China) (1:10,000 diluted in blocking solution) was added. After overnight incubation at 4°C, the nitrocellulose membrane was washed with TBST (TBS plus 0.1% Tween-20) three times for 10 min each time. The membrane was then incubated for 3 h in horseradish-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Zhongshan, Beijing, China) (1:10,000 in blocking solution), washed three times for 10 min in TBST, and washed in TBS for 5 min. The nitrocellulose membrane was developed by horseradish peroxidase method by adding 1 mL of 4-chloro-1-naphthol in methanol (6 mg/mL) to 9 mL of TBS and 6 μL of H2O2 and reacting for 10 min.

Recombinant Expression of MjRPS27 With Cell-Penetrating TAT Peptide

To ensure the entry of recombinant MjRPS27 into the cells, we fused the sequence encoding the cell-penetrating TAT peptide (TATGGAGAGGAAGAAGCGGAGACAGCGACGAAGA) (35) with MjRPS27 and then constructed pET30a–TAT–MjRPS27 to express the TAT–MjRPS27 fusion protein in E. coli. The protein was purified by Ni-resin chromatography (GenScript, Nanjing, China) and used for the overexpression assay in shrimp.

Immunocytochemistry Assay

To detect whether the recombinant protein could enter shrimp cells, healthy shrimp were divided into two groups (10 individuals for each group), and the TAT–MjRPS27 protein was injected into the shrimp (10 μg/shrimp). The same amount of TAT-His tag protein and BSA was also injected as a control. The hemolymph was extracted using sterile syringes with anticoagulant and a 4% paraformaldehyde solution. Hemocytes were collected by centrifuging at 800 × g for 6 min at 4°C. Afterwards, the hemocytes were washed with anticoagulant and a 4% paraformaldehyde solution. The hemocytes were dropped onto polylysine-treated slides and allowed to stand for 1 h in a wet box. Triton-X100 (0.2%) was added to the slides for 5 min and washed with PBS six times (5 min each time). After blocking with 3% BSA (in PBS) at 37°C for 30 min, the primary antibody against His tag (1:1,000 dilution with 3% BSA; Zhongshan, Beijing, China) was added to the glass slides and incubated at 37°C overnight. After washing with PBS six times, the glass slides were blocked with 3% BSA (in PBS) at 37°C for 30 min. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody was then added to the slides in darkness at 37°C for 1 h. After washing with PBS six times, the glass slides were incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1 μg/mL) for 10 min in darkness and washed six times to remove excess DAPI. Finally, the glass slides were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus DP71).

The fluorescence immunocytochemical assay was also used to detect the nuclear translocation of MjDorsal and MjRelish after MjRPS27 knockdown. The anti-Dorsal and anti-Relish sera used in the assay were prepared in our laboratory (36). The healthy shrimp were divided into two groups and 10 shrimp were used in each group. DsMjRPS27 and dsGFP were firstly injected into shrimp, WSSV was then injected 48 h post dsMjRPS27 injection. After 2 h of WSSV injection, hemocytes were collected for immunocytochemical analysis. dsGFP and WSSV injection shrimp served as controls.

The immunocytochemical assay was performed as described above. The anti-MjDorsal or anti-MjRelish (1:400 in 3% bovine serum albumin) was used as primary antibody, and the Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antibody to rabbit (1:1,000 ratio, diluted in 3% BSA) was used as the second antibody. The number of cells of MjDorsal or MjRelish into the nucleus or not into nucleus in different fields was observed under a microscope (Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan), and about 100 cells were counted. The experiment was repeated three times, the dsGFP injection was used as a control. A student's t-test was used to analyze difference significant among these data, and significant difference was accepted at p < 0.05.

Overexpression Assay

To further confirm the function MjRPS27 in shrimp, a type of MjRPS27 “overexpression” was performed by TAT–MjRPS27 injection following previous report (37, 38). Shrimp were divided into two groups (10 individual each). The TAT–MjRPS27 recombinant protein was mixed with WSSV and immediately injected into shrimp (10 μg/shrimp), and a TAT-His tag plus a WSSV injection was used as a control. The mixture was intramuscularly injected into shrimp at the penultimate segment with a microsyringe. Hemocytes and gills were collected at 24 and 48 h post injection, and WSSV replication was analyzed by qPCR using VP28 expression as an indicator.

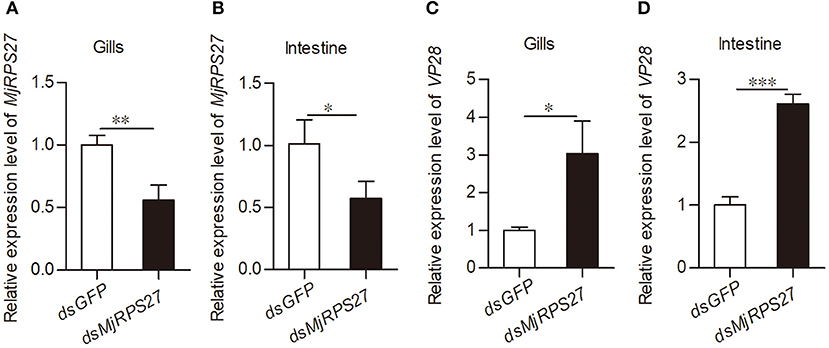

MjDorsal, MjRelish, and Related AMP Detection After Knockdown of MjRPS27 by RNAi

To determine whether the immune function of MjRPS27 was related to NF-κB pathways, we detected the expression of MjDorsal, MjRelish, and related antimicrobial peptides of NF-κB pathways (RT-PCR primers in Table 1) in the intestine after MjRPS27 knockdown by RNAi. The qPCR data analysis method was the same as that which was mentioned before.

Assessment of Survival Rates

To further confirm the role of MjRPS27 in the WSSV infection of M. japonicus, we performed a survival assay for the injection of recombinant protein (a type of overexpression). We initially confirmed that the constructed recombinant protein with a cell-penetrating TAT peptide can enter the cell. Shrimps were randomly divided into two groups with 40 animals per group. In the first one, the mixture of TAT–MjRPS27 (50 μg/shrimp) and WSSV (5 × 107 copies per shrimp) was intramuscularly injected into the penultimate segment of the shrimp; the same amount of TAT-His tag purified from the empty pET30a–TAT vector together with WSSV was injected into the second group. The number of dead shrimps was counted every 12 h after injection, and the survival rate of the shrimp was calculated and analyzed using GraphPad Prism software.

Statistical Analysis

Data are represented as the results of at least three independent experiments. Student's t-tests were used to calculate significance at p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01(**), and p < 0.001(***). Some data (the nuclear translocation rates of MjDorsal and MjRelish) were subjected to one-way ANOVA with a Scheffe test from triplicate assays. Significant differences (p < 0.05) are represented by different letters.

Results

MjRPS27 Was Upregulated in Shrimp Challenged by WSSV

MjRPS27 consists of 375 bp with a 252 bp opening reading frame, which encodes 84 amino acids (GenBank MN385248, Figure S1). The theoretical values of the isoelectric point and molecular weight are 9.47 and 9222.93, respectively. The sequence alignment analysis (Figure S2A) and phylogenetic-tree analysis (Figure S2B) showed that RPS27 exhibited high sequence conservation in different organisms, and that MjRPS27's sequence was highly similar to that of Litopenaeus vannamei and Limulus polyphemus.

The tissue distribution of MjRPS27 in shrimp was analyzed by RT-PCR, and results showed that MjRPS27 was expressed in all tested tissues (Figure 1A). To determine whether MjRPS27 responded to WSSV infection, the expression pattern was analyzed by qPCR. The expression of MjRPS27 was found to increase significantly in hemocytes 12 and 24 h after WSSV injection. MjRPS27 was also upregulated in the gills of shrimp challenged with WSSV (Figure 1B). These results suggested that MjRPS27 was involved in viral infection in shrimp.

Figure 1. Tissue distribution and expression pattern of MjRPS27. (A) Tissue distribution of MjRPS27 mRNA. (B) Expression pattern of MjRPS27 in hemocytes and gills of shrimp challenged by WSSV as analyzed by qPCR. PBS injection shrimp served as a control. At least three shrimp were used for hemocytes and tissue collection at different time points. Significance was compared between the infected group and the same time point by t-test analysis, and significant difference was accepted at *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

WSSV Replication Increased in MjRPS27-Knockdown Shrimp

To examine the function of MjRPS27 in the WSSV infection of shrimp, we conducted an RNA interference experiment and followed the WSSV infection. After 48 h of dsRNA injection, the mRNA expression of MjRPS27 was detected by qPCR. MjRPS27 expression was successfully knocked down in the gills (Figure 2A) and intestine (Figure 2B). Then, the MjRPS27 knockdown shrimp were challenged with WSSV (5 × 107 copies per shrimp). The expression level of WSSV envelope protein 28 (VP28) was analyzed by qPCR after 24 h. Compared with the control (dsGFP injection), the expression level of VP28 significantly increased (Figures 2C,D). To confirm the MjRPS27 RNAi was a specific knockdown of the gene, we analyzed expressions of other genes in hemocytes and the intestine of the MjRPS27-silenced shrimp by qPCR (Table S1), including a related gene, ribosomal protein S28 (MjRPS28), a transcription factor gene MjFOXO, and other unrelated genes, such as a G protein-coupled receptor with methuselah domain (MjMthGPCR), a serine/threonine-protein kinase (MjAKT), and two small GTPases (MjRab5 and MjRab7). The results showed that the expression of all above genes was not altered compared with controls in hemocytes and the intestine (Figure S3), suggesting that there was no non-specific silencing of the gene after injection of dsRNA of MjRPS27. Based on the above results, we can speculate that MjRPS27 can inhibit WSSV proliferation in shrimp.

Figure 2. VP28 expression was increased after knockdown of MjRPS27. (A,B) The RNAi efficiency of MjRPS27 was analyzed by qPCR 48 h post-dsRNA injection. The same amount of dsGFP injection served as a control. (C,D) After knockdown of MjRPS27, the shrimp were challenged with WSSV (5 × 107 copies per shrimp), and the expression levels of VP28 were analyzed by qPCR 24 h post-WSSV challenge. Compared with the controls (dsGFP injection), the mRNA expression level of VP28 significantly increased. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

WSSV Replication Decreased in MjRPS27-Overexpressed Shrimp

To further confirm the function of MjRPS27 in the antiviral immunity of shrimp, an “overexpression” assay was performed. The TAT–MjRPS27 fusion protein was expressed and purified (Figure 3A), and then healthy shrimp were injected with the recombinant protein. To determine whether the recombinant protein can enter cells, an immunocytochemistry assay was performed using anti-His tag as the primary antibody. As shown in Figure 3B, TAT–MjRPS27 was detected in hemocytes 1 h post injection. After observing that the recombinant protein can enter hemocytes, the overexpression assay was performed and the WSSV replication and survival rate of shrimp were analyzed. We firstly mixed TAT–MjRPS27 protein (50 μg/shrimp) and WSSV (5 × 107 copies/shrimp) together and immediately injected this into the shrimp. Compared with the control (TAT-His tag protein and WSSV injection), the shrimp survival rate significantly increased (Figure 3C). VP28 expression in hemocytes and gills was also analyzed by qPCR 24 and 48 h post injection. Results showed that VP28 expression was significantly inhibited in hemocytes and gills at 24 and 48 h post injection (Figures 3D–G). All these findings indicated that MjRPS27 can inhibit the replication of WSSV in M. japonicus.

Figure 3. TAT–MjRPS27 overexpression inhibited WSSV proliferation. (A) Expression and purification of recombinant of TAT-MjRPS27. Lane M, protein marker; lane 1, total proteins from E. coli; lane 2, total proteins from E. coli after induced by IPTG; and lane 3, purified recombinant protein. (B) Immunocytochemistry to detect recombinant protein in hemocytes. Top panel, recombinant protein (TAT-MjRPS27) injection (10 μg/shrimp); middle, His tag protein injection; bottom, BSA injection. Bars = 20 μm. (C) Survival rate of shrimp injected with TAT-MjRPS27 (50 μg/shrimp); His tag protein injection served as a control. (D) VP28 expression in hemocytes of TAT-MjRPS27-WSSV-injected shrimp analyzed by qPCR at 24 h post-injection, His-WSSV-injected shrimp served as a control. (E) VP28 expression in gills of TAT-MjRPS27-WSSV-injected shrimp analyzed by qPCR at 24 h post injection, His-WSSV-injected shrimp served as a control. (F,G) VP28 expression in hemocytes (F) and Gills (G) of TAT-MjRPS27 and WSSV-injected shrimp was analyzed by qPCR 48 h post injection. His-WSSV-injected shrimp served as a control. PCR data were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method and expressed as the mean ± SD. Student's t-test was used to analyze significant differences among PCR data, and significant difference was accepted at *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

MjRPS27 Involvement in the Regulation of NF-κB Pathways

Previous studies have shown that RPS27 is related to the activation of NF-κB pathways in cancer cells (23). In our previous studies, we found that the Toll pathway in shrimp can regulate the expression of several antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), such as anti-lipopolysaccharide factor C2 (ALF-C2) and Crustin I-1 (CruI-1). The IMD pathway can regulate the expression of ALF-B1, ALF-C1, and ALF-D2 (25, 39). Accordingly, we evaluated the expression of Dorsal (transcription factor of the Toll pathway), Relish (transcription factor of the IMD pathway), and AMPs in shrimp after MjRPS27 knockdown (Figure 4A). Compared with the control group, the expression levels of MjDorsal and MjRelish decreased significantly (Figures 4B,C); the expression levels of MjALFB1, MjALFC1, MjALFC2, and MjALFD2 in the intestine also decreased significantly (Figure 4D). These results suggested that MjRPS27 was involved in the regulation of the Toll and IMD pathways and that its antiviral function may be related to the upregulation of AMPs in shrimp.

Figure 4. MjRPS27 was involved in the activation of the Toll and IMD pathways. (A) The RNA interference efficiency of MjRPS27 was analyzed by qPCR 48 h after dsMjRPS27 injection. The same amount of dsGFP was injected as a control. (B) After knockdown of MjRPS27, the expression level of MjDorsal was analyzed by qPCR. The mRNA expression level of MjDorsal was significantly downregulated compared with the control (dsGFP injection). (C) After knockdown of MjRPS27, the expression level of MjRelish was analyzed by qPCR. The mRNA expression level of MjRelish was significantly downregulated compared with the control (dsGFP injection). (D) After knockdown of MjRPS27, the expression levels of AMPs (MjALFB1, MjALFC1, MjALFC2, MjALFD2, and MjCruI 1) were analyzed by qPCR. The expression levels of AMPs, except MjCruI 1, were significantly downregulated compared with the control (injected dsGFP). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

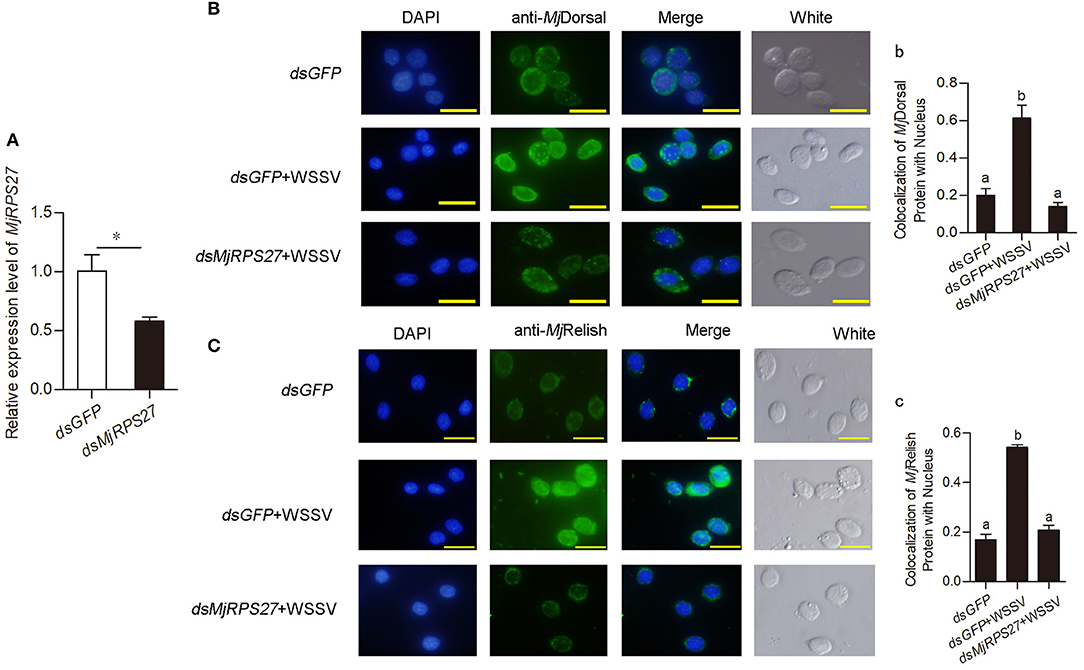

Decreased Nuclear Translocation of MjDorsal and MjRelish After MjRPS27 Knockdown

Previous study found that knockdown of MPS-1/RPS27 inhibited NF-κB activity by reducing the phosphorylation of p65 and inhibiting NF-κB nuclear translocation in human gastric cells (23). We used antibodies against MjDorsal and MjRelish prepared in our laboratory to determine whether MjRPS27 affected the MjDorsal and MjRelish entry into the nucleus. After knockdown of MjRPS27 and WSSV injection, MjDorsal and MjRelish in hemocytes were detected by fluorescence immunocytochemical assay, and the same amount of dsGFP was injected as a control. Results showed that, after MjRPS27 knockdown (Figure 5A), the entry rate of MjDorsal and MjRelish into the nucleus decreased significantly (Figures 5Bb,Cc). These results indicated that MjRPS27 can regulate the nuclear translocation of MjDorsal and MjRelish and subsequently regulate the expression of AMPs to prevent viral proliferation in shrimp infected by WSSV.

Figure 5. The nuclear translocation of MjDorsal and MjRelish decreased after knockdown of MjRPS27 in shrimp. (A) Efficiency of MjRPS27 interference in gills; dsGFP injection served as a control. (B) Immunocytochemical analysis to detect the nucleus translocation of MjDorsal in hemocytes of shrimp after RNAi of MjRPS27; dsGFP-injected shrimp served as a control. Bars = 20 μm. (b) Statistics analysis of MjDorsal and nucleus co-localization in hemocytes. (C) Immunocytochemical analysis used to detect the nucleus translocation of MjRelish in hemocytes of shrimp after RNAi of MjRPS27; dsGFP-injected shrimp served as a control. Bars = 20 μm. (c) Statistics analysis of the colocalization of MjRelish with nucleus in hemocytes (details described in Materials and Methods). *p < 0.05.

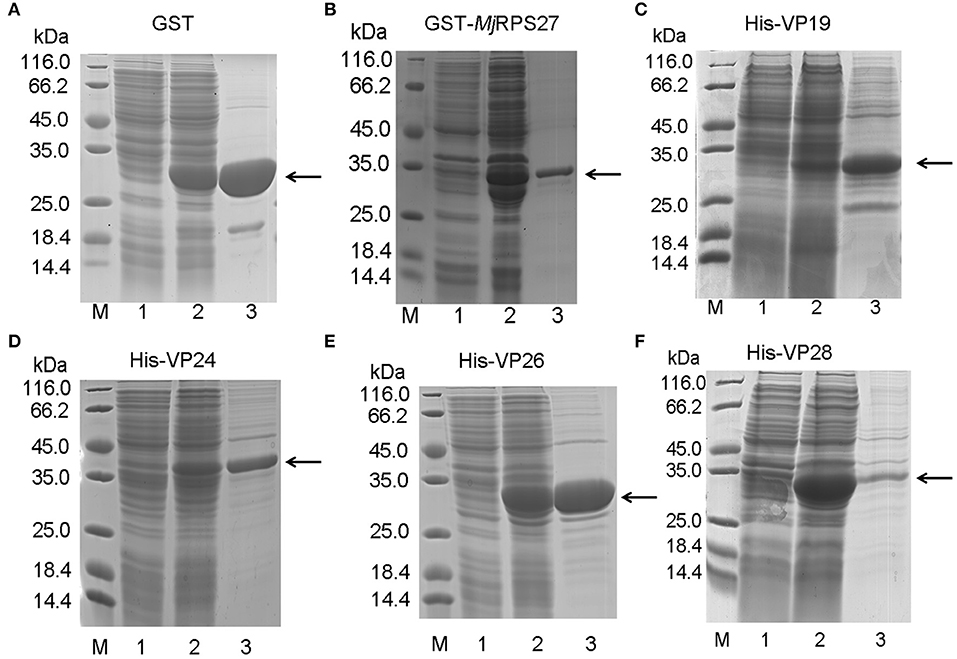

Expression and Purification of MjRPS27 and WSSV Envelope Proteins

To study the function and possible mechanism of MjRPS27 in shrimp immunity, we also analyzed MjRPS27 interaction with envelope proteins of WSSV. We initially expressed the GST-tagged MjRPS27 protein and His-tagged envelope proteins of WSSV for pulldown analysis. Figure 6 shows the purified recombinant proteins, including the GST tag protein expressed in E. coli (Figure 6A), purified GST-tagged MjRPS27 expressed in E. coli with pGEX4T-2/MjRPS27 (Figure 6B), and four types of His-tagged envelope proteins of WSSV expressed in E. coli with pET-32a(+)/VP19, pET-32a(+)/VP24, pET-32a(+)/VP26, and pET-30a(+)/VP28 (Figures 6C–F).

Figure 6. Recombinant expression and purification of MjRPS27 and WSSV envelope proteins. (A) Recombinant expression and purification of GST tag protein. Lane M, protein marker; lane 1, total proteins from E. coli; lane 2, total proteins from E. coli after induction by IPTG; and lane 3, purified GST protein. (B) Recombinant expression and purification of MjRPS27. Lane M, protein marker; lane 1, total proteins from E. coli with pGEX4T-2/MjRPS27; lane 2, total proteins from E. coli after induction by IPTG; and lane 3, purified MjRPS27. (C) Recombinant expression and purification of WSSV VP19. Lane M, protein marker; lane 1, total proteins from E. coli with pET-32a(+)/VP19; lane 2, total proteins from E. coli after induction by IPTG; and lane 3, purified recombinant protein. (D) Recombinant expression and purification of WSSV VP24. Lane M, protein marker; lane 1, total proteins from E. coli with pET-32a(+)/VP24; lane 2, total proteins from E. coli after induction by IPTG; and lane 3, purified VP24. (E) Recombinant expression and purification of VP26. Lane M, protein marker; lane 1, total proteins from E. coli with pET-32a(+)/VP26; lane 2, total proteins from E. coli after induction by IPTG; and lane 3, purified VP26. (F) Recombinant expression and purification of WSSV VP28. Lane M, protein marker; lane 1, total proteins from E. coli with pET-30a(+)/VP28; lane 2, total proteins from E. coli after induction by IPTG; and lane 3, purified VP28. The arrows indicated the purified proteins.

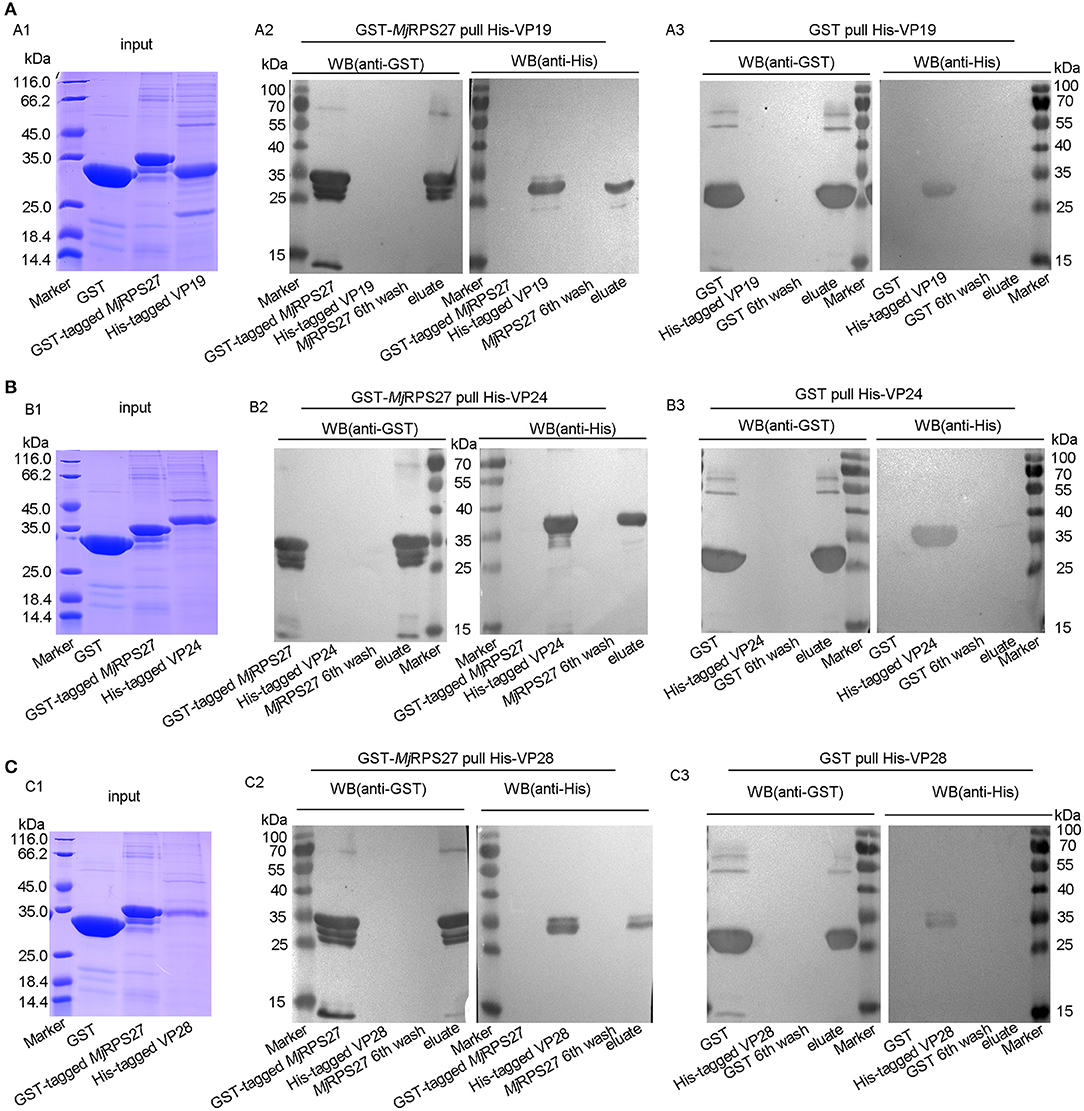

MjRPS27 Interaction With VP19, VP24, and VP28 of WSSV

To study the possible mechanism of MjRPS27 activity against WSSV in shrimp, the interaction of the protein with WSSV was analyzed. GST pulldown was carried out using purified MjRPS27 and WSSV envelope proteins. Given that the molecular weight of MjRPS27 with GST tag protein is similar to those of WSSV envelope proteins, we detected the interactions by Western blot assay. The proteins (GST, GST-tagged MjRPS27, and His-tagged VP19) used for the interaction analysis are shown in Figure 7A1. We observed a band in the elution lanes detected by anti-GST (Figure 7A2, left panel) and anti-His (Figure 7A2, right panel); however, in the control (Figure 7A3), only a band in the elution lane was detected by anti-GST (Figure 7A3, left panel), and no band in the elution lane was detected by anti-His (Figure 7A3, right panel). These results suggested that MjRPS27 interacted with VP19, but GST protein cannot interact with VP19. The same results were obtained in the interaction analysis of MjRPS27 with VP24 (Figure 7B) and MjRPS27 with VP28 (Figure 7C). All these results suggest that MjRPS27 can interact with VP19, VP24, and VP28 but not with VP26 (Figure S4). Based on these findings, we can conclude that MjRPS27 interacted with VP19, VP24, and VP28 proteins, indicating that MjRPS27 may inhibit the proliferation of WSSV by interacting with the envelope proteins to prevent WSSV invasion and assembly. We could also assume that MjRPS27 recognized infected WSSV through interaction with envelope proteins and activated the NF-κB pathway to induce expression of AMPs.

Figure 7. MjRPS27 interacted with the WSSV envelope proteins, VP19, VP24, and VP28. (A) The interaction of MjRPS27 with VP19 was analyzed by GST pulldown. (A1) Input proteins (GST protein, GST-tagged MjRPS27, and His-tagged VP19) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (A2) GST-MjRPS27 pulldown His-VP19 was analyzed by Western blot: left panel, proteins used in the Pulldown assay were initially separated by SDS-PAGE, electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and analyzed by Western blot using anti-GST as primary antibody; right panel, SDS-PAGE-separated proteins were transferred onto the nitrocellulose membrane and analyzed by Western blot using anti-His as primary antibody. (A3) GST pulldown His-VP19 analyzed by Western blot: left panel, Western blot with anti-GST; right panel, Western blot using anti-His as primary antibody (control). (B) The interaction of MjRPS27 with VP24 was analyzed by GST pulldown. (B1) Input proteins (GST protein, GST-tagged MjRPS27 and His-tagged VP24) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (B2) GST-MjRPS27 pulldown His-VP24 was analyzed by Western blot: left panel, Western blot with anti-GST; right panel, Western blot analysis using anti-His as primary antibody. (B3) GST pulldown His-VP24 was analyzed by Western blot: left panel, Western blot with anti-GST; right panel, Western blot using anti-His as primary antibody (control). (C) The interaction of MjRPS27 with VP28 was analyzed by GST pulldown. (C1) Input proteins (GST protein, GST-tagged MjRPS27, and His-tagged VP28) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (C2), GST-MjRPS27 pulldown His-VP28 analysis: left panel, Western blot analysis with anti-GST; right panel, Western blot analysis using anti-His as primary antibody. (C3) GST pulldown His-VP28 analysis: left panel, Western blot analysis with anti-GST; right panel, Western blot analysis using anti-His as primary antibody (control).

Discussion

Several studies have implicated SEPs in response to infection and innate immunity, but the mechanisms were unclear for most of them. In the present study, we found that MjRPS27 was upregulated after WSSV stimulation, suggesting that MjRPS27 may participate in the immune response against WSSV in M. japonicus. Further mechanism study shows that MjRPS27 interacts with WSSV envelope proteins and inhibits WSSV infection by activating the NF-κB pathways to induce the expression of AMPs in shrimp.

In the present study, we knocked down the expression of MjRPS27 and detected the expression of VP28 after WSSV challenge. We found that the expression of VP28 was significantly increased. To confirm the function of MjRPS27, we constructed a type of overexpression assay using the recombinant MjRPS27 carrying a cell-penetrating TAT peptide to enhance the cellular uptake of the protein. Results showed that the expression of VP28 in shrimp significantly decreased and that the survival rate of shrimp increased significantly compared with that of the control group. Overall, the findings suggested that MjRPS27 can inhibit WSSV infection in shrimp.

Dorsal is a known NF-κB transcription factor in the classical Toll pathway. In Litopenaeus vannamei, the silence of Dorsal leads to a decline in the expression of a specific group of AMPs, such as the anti-lipopolysaccharide factor (ALF) and lysozyme (LYZ) family. Meanwhile, ALF1 and LYZ1 have been shown to interact with several WSSV structural proteins to inhibit viral infection (40). In other studies, the Toll and IMD pathways in shrimp are activated and AMP are induced after WSSV infection. Some AMPs and other immune-related genes such as ALF, penaeidin, and PMAV (an antiviral gene from Penaeus monodon encoding a protein with a C-type lectin-like domain) have direct antiviral activity (41–44). Accordingly, after MjRPS27 knockdown, we detected the expression of AMPs and the nuclear translocation of MjDorsal and MjRelish. We found that the nuclear translocation of MjDorsal and MjRelish were significantly reduced (Figure 5) and that the expression of AMPs was markedly downregulated (Figure 4). All the results suggested that MjRPS27 can activate the NF-κB pathways and induce the expression of AMPs, thereby playing an antiviral role in shrimp. The similar results were reported in human gastric cancer cells. Knockdown of MSP-1/RPS27 can inhibit NF-κB activity by reducing phosphorylation of p65 and IκB, inhibiting NF-κB nuclear translocation, and downregulating its DNA binding activity (23).

How does the RPS27 activate the NF-κB pathway? It is reported that some ribosomal proteins can directly regulate gene transcription or modulate transcriptional factors (23). Ribosomal proteins usually contain sequences such as zinc finger motifs, which enables them to interact instantaneously or stably with DNA and RNA. For example, ribosomal protein S3 (RPS3) can interact with NF-κB, with p65 forming as a subunit of a p65-dimer and p65-p50 isodimer DNA binding complex, which enhances DNA binding by stabilizing the binding of Rel subunit to some homologous sites. RPS3 knockout impairs the activity of NF-κB and the transcription of its target gene (45). Knocking down MPS-1 (RPS27) in gastric cancer cells can affect the activity of NF-κB. It is speculated that MPS-1, like RPS3, can directly or indirectly regulate the activity of NF-κB by binding to the target DNA of NF-κB and stabilizing the protein–DNA complex as a transcriptional co-regulator with zinc finger domain (23). The knockout of MPS-1 proteins reduces the stability of complexes and their interaction with target genes, thereby reducing the activity of NF-κB (23). We speculated that MjRPS27 may directly or indirectly regulate the activity of MjDorsal and MjRelish by binding their target DNA and stabilizing protein–DNA complexes. The detailed mechanism of RPS27 activating the NF-κB pathway needs further investigation.

In previous studies, we have found that some proteins can inhibit the replication of WSSV by binding with WSSV proteins. For example, prohibitin can inhibit the proliferation of WSSV by binding with VP28, VP26, and VP24 in crayfish (46). Some envelope proteins of WSSV can also be involved in the process of virus infection. For example, the major envelope protein VP28 reportedly plays a key role in the initial stage of systemic WSSV infection in shrimp (47). Moreover, WSSV VP28, as an attachment protein, has been found to play an important role in the process of infection, such as through binding the virus to shrimp cells and helping them enter the cytoplasm (48). The interaction between MjRPS27 and WSSV envelope proteins (VP19, VP24, and VP28) was examined by GST pulldown. Results showed that MjRPS27 can bind to VP19, VP24, and VP28, suggesting that MjRPS27 can also inhibit the invasion, assembly, and proliferation of envelope proteins by binding to WSSV envelope proteins.

In conclusion, our study showed that a sORF-encoded protein, MjRPS27, participated in the innate immune process of shrimp infected by WSSV. MjRPS27 played an antiviral role by binding with WSSV envelope proteins and activating the NF-κB pathway. Our research further enriched knowledge on invertebrate antiviral innate immunity and the functional diversity of RPS27.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in Genbank under the accession number MN385248. The other data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Author Contributions

J-XW and X-FZ supervised the overall project and designed the experiments. M-QD performed the experiments, analyzed data. J-DX helped to perform experiments and analyzed data. CL performed RNA interference experiment and helped to analyze data.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2018YFD0900502) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31630084), and Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Animal Cell and Developmental Biology (Grant No. SDKLACDB-2019019).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02763/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Basrai MA, Hieter P, Boeke JD. Small open reading frames: beautiful needles in the haystack. Genome Res. (1997) 7:768–71. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.8.768

2. Khitun A, Ness TJ, Slavoff SA. Small open reading frames and cellular stress responses. Mol Omics. (2019) 15:108–16. doi: 10.1039/C8MO00283E

3. Aspden JL, Eyre-Walker YC, Phillips RJ, Amin U, Mumtaz MA, Brocard M, et al. Extensive translation of small Open reading frames revealed by Poly-Ribo-Seq. Elife. (2014) 3:e3528. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03528

4. Saghatelian A, Couso JP. Discovery and characterization of smORF-encoded bioactive polypeptides. Nat Chem Biol. (2015) 11:909–16. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1964

5. White JW, Saunders GF. Structure of the human glucagon gene. Nucleic Acids Res. (1986) 14:4719–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.12.4719

6. Wadler CS, Vanderpool CK. A dual function for a bacterial small RNA: SgrS performs base pairing-dependent regulation and encodes a functional polypeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2007) 104:20454–59. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708102104

7. Kastenmayer JP, Ni L, Chu A, Kitchen LE, Au WC, Yang H, et al. Functional genomics of genes with small open reading frames (sORFs) in S. cerevisiae. Genome Res. (2006) 16:365–73. doi: 10.1101/gr.4355406

8. Guo B, Zhai D, Cabezas E, Welsh K, Nouraini S, Satterthwait AC, et al. Humanin peptide suppresses apoptosis by interfering with Bax activation. Nature. (2003) 423:456–61. doi: 10.1038/nature01627

9. Magny EG, Pueyo JI, Pearl FM, Cespedes MA, Niven JE, Bishop SA, et al. Conserved regulation of cardiac calcium uptake by peptides encoded in small open reading frames. Science. (2013) 341:1116–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1238802

10. MacLennan DH, Kranias EG. Phospholamban: a crucial regulator of cardiac contractility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2003) 4:566–77. doi: 10.1038/nrm1151

11. Schmitt JP, Kamisago M, Asahi M, Li GH, Ahmad F, Mende U, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure caused by a mutation in phospholamban. Science. (2003) 299:1410–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1081578

12. Anderson DM, Anderson KM, Chang CL, Makarewich CA, Nelson BR, McAnally JR, et al. A micropeptide encoded by a putative long noncoding RNA regulates muscle performance. Cell. (2015) 160:595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.009

13. Jackson R, Kroehling L, Khitun A, Bailis W, Jarret A, York AG, et al. The translation of non-canonical open reading frames controls mucosal immunity. Nature. (2018) 564:434–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0794-7

14. Razooky BS, Obermayer B, O'May JB, Tarakhovsky A. Viral infection identifies micropeptides differentially regulated in smORF-containing lncRNAs. Genes. (2017) 8:E206. doi: 10.3390/genes8080206

15. Chan YL, Suzuki K, Olvera J, Wool IG. Zinc finger-like motifs in rat ribosomal proteins S27 and S29. Nucleic Acids Res. (1993) 21:649–55. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.3.649

16. Fernandez-Pol JA, Klos DJ, Hamilton PD. A growth factor-inducible gene encodes a novel nuclear protein with zinc finger structure. J Biol Chem. (1993) 268:21198–204.

17. Wong JM, Mafune K, Yow H, Rivers EN, Ravikumar TS, Steele GJ, et al. Ubiquitin-ribosomal protein S27a gene overexpressed in human colorectal carcinoma is an early growth response gene. Cancer Res. (1993) 53:1916–20.

18. Zhou X, Liao WJ, Liao JM, Liao P, Lu H. Ribosomal proteins: functions beyond the ribosome. J Mol Cell Biol. (2015) 7:92–104. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjv014

19. Mazumder B, Poddar D, Basu A, Kour R, Verbovetskaya V, Barik S. Extraribosomal l13a is a specific innate immune factor for antiviral defense. J Virol. (2014) 88:9100–10. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01129-14

20. Lohrum MA, Ludwig RL, Kubbutat MH, Hanlon M, Vousden KH. Regulation of HDM2 activity by the ribosomal protein L11. Cancer Cell. (2003) 3:577–87. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00134-X

21. Jin A, Itahana K, O'Keefe K, Zhang Y. Inhibition of HDM2 and activation of p53 by ribosomal protein L23. Mol Cell Biol. (2004) 24:7669–80. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7669-7680.2004

22. Zhang Y, Wolf GW, Bhat K, Jin A, Allio T, Burkhart WA, et al. Ribosomal protein L11 negatively regulates oncoprotein MDM2 and mediates a p53-dependent ribosomal-stress checkpoint pathway. Mol Cell Biol. (2003) 23:8902–12. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8902-8912.2003

23. Yang ZY, Qu Y, Zhang Q, Wei M, Liu CX, Chen XH, et al. Knockdown of metallopanstimulin-1 inhibits NF-kappaB signaling at different levels: the role of apoptosis induction of gastric cancer cells. Int J Cancer. (2012) 130:2761–70. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26331

24. Tassanakajon A, Rimphanitchayakit V, Visetnan S, Amparyup P, Somboonwiwat K, Charoensapsri W, et al. Shrimp humoral responses against pathogens: antimicrobial peptides and melanization. Dev Comp Immunol. (2018) 80:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.05.009

25. Sun JJ, Lan JF, Shi XZ, Yang MC, Niu GJ, Ding D, et al. beta-Arrestins negatively regulate the toll pathway in shrimp by preventing dorsal translocation and inhibiting dorsal transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. (2016) 291:7488–504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.698134

26. Li M, Li C, Ma C, Li H, Zuo H, Weng S, et al. Identification of a C-type lectin with antiviral and antibacterial activity from pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Dev Comp Immunol. (2014) 46:231–40. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2014.04.014

27. Li C, Chen YX, Zhang S, Lu L, Chen YH, Chai J, et al. Identification, characterization, and function analysis of the Cactus gene from Litopenaeus vannamei. PloS ONE. (2012) 7:e49711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049711

28. Li C, Chen Y, Weng S, Li S, Zuo H, Yu X, et al. Presence of tube isoforms in Litopenaeus vannamei suggests various regulatory patterns of signal transduction in invertebrate NF-kappaB pathway. Dev Comp Immunol. (2014) 42:174–85. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2013.08.012

29. Huang XD, Yin ZX, Jia XT, Liang JP, Ai HS, Yang LS, et al. Identification and functional study of a shrimp Dorsal homologue. Dev Comp Immunol. (2010) 34:107–13. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2009.08.009

30. Sanchez-Paz A. White spot syndrome virus: an overview on an emergent concern. Vet Res. (2010) 41:43. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2010015

31. Wang XW, Xu YH, Xu JD, Zhao XF, Wang JX. Collaboration between a soluble C-type lectin and calreticulin facilitates white spot syndrome virus infection in shrimp. J Immunol. (2014) 193:2106–17. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400552

32. Xu JD, Diao MQ, Niu GJ, Wang XW, Zhao XF, Wang JX. A small GTPase, RhoA, inhibits bacterial infection through integrin mediated phagocytosis in invertebrates. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1928. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01928

33. Yang MC, Shi XZ, Yang HT, Sun JJ, Xu L, Wang XW, et al. Scavenger receptor C mediates phagocytosis of white spot syndrome virus and restricts virus proliferation in shrimp. PLoS Pathog. (2016) 12:e1006127. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006127

34. Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. (1970) 227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0

35. Xu JD, Jiang HS, Wei TD, Zhang KY, Wang XW, Zhao XF, et al. Interaction of the small GTPase Cdc42 with arginine kinase restricts white spot syndrome virus in shrimp. J Virol. (2017) 91:e01916–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01916-16

36. Sun JJ, Lan JF, Zhao XF, Vasta GR, Wang JX. Binding of a C-type lectin's coiled-coil domain to the Domeless receptor directly activates the JAK/STAT pathway in the shrimp immune response to bacterial infection. PLoS Pathog. (2017) 13:e1006626. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006626

37. Xu JD, Jiang HS, Wei TD, Zhang KY, Wang XW, Zhao XF, et al. Interaction of the small GTPase Cdc42 with arginine kinase restricts white spot syndrome virus in shrimp. J Virol. (2017) 91:e01916–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00269-17

38. Zhou Z, Li Y, Yuan C, Zhang Y, Qu L. Oral administration of TAT-PTD-diapause hormone fusion protein interferes with Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) development. J Insect Sci. (2015) 15:123. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iev102

39. Liu N, Wang XW, Sun JJ, Wang L, Zhang HW, Zhao XF, et al. Akirin interacts with Bap60 and 14-3-3 proteins to regulate the expression of antimicrobial peptides in the kuruma shrimp (Marsupenaeus japonicus). Dev Comp Immunol. (2016) 55:80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2015.10.015

40. Li H, Yin B, Wang S, Fu Q, Xiao B, Lu K, et al. RNAi screening identifies a new Toll from shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei that restricts WSSV infection through activating Dorsal to induce antimicrobial peptides. PLoS Pathog. (2018) 14:e1007109. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007109

41. Tharntada S, Ponprateep S, Somboonwiwat K, Liu H, Soderhall I, Soderhall K, et al. Role of anti-lipopolysaccharide factor from the black tiger shrimp, Penaeus monodon, in protection from white spot syndrome virus infection. J Gen Virol. (2009) 90:1491–8. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.009621-0

42. Liu H, Jiravanichpaisal P, Soderhall I, Cerenius L, Soderhall K. Antilipopolysaccharide factor interferes with white spot syndrome virus replication in vitro and in vivo in the crayfish Pacifastacus leniusculus. J Virol. (2006) 80:10365–71. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01101-06

43. Woramongkolchai N, Supungul P, Tassanakajon A. The possible role of penaeidin5 from the black tiger shrimp, Penaeus monodon, in protection against viral infection. Dev Comp Immunol. (2011) 35:530–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2010.12.016

44. Wang XW, Wang JX. Diversity and multiple functions of lectins in shrimp immunity. Dev Comp Immunol. (2013) 39:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2012.04.009

45. Wan F, Anderson DE, Barnitz RA, Snow A, Bidere N, Zheng L, et al. Ribosomal protein S3: a KH domain subunit in NF-kappaB complexes that mediates selective gene regulation. Cell. (2007) 131:927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.009

46. Lan JF, Li XC, Sun JJ, Gong J, Wang XW, Shi XZ, et al. Prohibitin interacts with envelope proteins of white spot syndrome virus and prevents infection in the red swamp crayfish, Procambarus clarkii. J Virol. (2013) 87:12756–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02198-13

47. van Hulten MC, Witteveldt J, Peters S, Kloosterboer N, Tarchini R, Fiers M, et al. The white spot syndrome virus DNA genome sequence. Virology. (2001) 286:7–22. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1002

Keywords: short open reading frame (sORF), sORF encoded polypeptides, white spot syndrome virus, antimicrobial peptides, dorsal, Relish, kuruma shrimp

Citation: Diao M-Q, Li C, Xu J-D, Zhao X-F and Wang J-X (2019) RPS27, a sORF-Encoded Polypeptide, Functions Antivirally by Activating the NF-κB Pathway and Interacting With Viral Envelope Proteins in Shrimp. Front. Immunol. 10:2763. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02763

Received: 31 August 2019; Accepted: 12 November 2019;

Published: 17 December 2019.

Edited by:

Brian Dixon, University of Waterloo, CanadaReviewed by:

Ikuo Hirono, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, JapanTamiru Alkie, Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada

Copyright © 2019 Diao, Li, Xu, Zhao and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jin-Xing Wang, anh3YW5nQHNkdS5lZHUuY24=

†Present address: Meng-Qi Diao, Key Laboratory of Biopharmaceuticals, Engineering Laboratory of Polysaccharide Drugs, National-Local Joint Engineering Laboratory of Polysaccharide Drugs, Shandong Academy of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Postdoctoral Scientific Research Workstation, Jinan, China

Meng-Qi Diao

Meng-Qi Diao Cang Li1

Cang Li1 Xiao-Fan Zhao

Xiao-Fan Zhao Jin-Xing Wang

Jin-Xing Wang