94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol., 18 February 2019

Sec. Cancer Immunity and Immunotherapy

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00138

Jesse D. Plotkin1†

Jesse D. Plotkin1† Michael G. Elias1†

Michael G. Elias1† Mohammad Fereydouni1

Mohammad Fereydouni1 Tracy R. Daniels-Wells2

Tracy R. Daniels-Wells2 Anthony L. Dellinger1

Anthony L. Dellinger1 Manuel L. Penichet2,3,4,5,6,7

Manuel L. Penichet2,3,4,5,6,7 Christopher L. Kepley1*

Christopher L. Kepley1*Mast cells (MC) are important immune sentinels found in most tissue and widely recognized for their role as mediators of Type I hypersensitivity. However, they also secrete anti-cancer mediators such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). The purpose of this study was to investigate adipose tissue as a new source of MC in quantities that could be used to study MC biology focusing on their ability to bind to and kill breast cancer cells. We tested several cell culture media previously demonstrated to induce MC differentiation. We report here the generation of functional human MC from adipose tissue. The adipose-derived mast cells (ADMC) are phenotypically and functionally similar to connective tissue expressing tryptase, chymase, c-kit, and FcεRI and capable of degranulating after cross-linking of FcεRI. The ADMC, sensitized with anti-HER2/neu IgE antibodies with human constant regions (trastuzumab IgE and/or C6MH3-B1 IgE), bound to and released MC mediators when incubated with HER2/neu-positive human breast cancer cells (SK-BR-3 and BT-474). Importantly, the HER2/neu IgE-sensitized ADMC induced breast cancer cell (SK-BR-3) death through apoptosis. Breast cancer cell apoptosis was observed after the addition of cell-free supernatants containing mediators released from FcεRI-challenged ADMC. Apoptosis was significantly reduced when TNF-α blocking antibodies were added to the media. Adipose tissue represents a source MC that could be used for multiple research purposes and potentially as a cell-mediated cancer immunotherapy through the expansion of autologous (or allogeneic) MC that can be targeted to tumors through IgE antibodies recognizing tumor specific antigens.

Mast cells (MC) are resident tissue immune cells that play an important role in innate and acquired immunity, but are most widely recognized in their role as regulators of Type I hypersensitivity (1, 2). Differences in MC phenotypes and functional responses between species have hampered progress in understanding their role in several disease processes (2–7). This incongruence has directed efforts toward obtaining sources of human MC that can be used to evaluate the role of these cells in basic mechanisms of disease without confounding differences between rodent and human systems (4, 5, 8). For example, MC can be obtained by culturing progenitor cells from cord blood, venous blood, fetal liver, bone marrow, and skin (8–12). However, variations in culture conditions and the resulting MC that are phenotypically and functionally immature still result in limitations that have hindered MC research. Thus, new sources of human MC are consistently needed.

One disease in which the role of MC has been investigated is cancer (13–15). It is controversial as to their role in this disease in light of contradictory findings between model systems and species and that studies in humans are solely correlative (i.e., an increase in MC numbers equates to poor prognosis (13, 16–18). Human MC contain several pro-inflammatory mediators, but are unique in their ability to pre-store and release potentially beneficial anti-cancer mediators. For example, human MC have pre-stored and releasable (through FcεRI engagement) tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) within their granules (2). Furthermore, human MC release granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) upon FcεRI stimulation (19, 20). Both TNF-α and GM-CSF have been used as anti-cancer agents (21, 22). Correlative studies in humans cannot address if the MC are affecting tumor growth; whether their presence enhances, inhibits, or are non-participating bystanders. Thus, developing ways to use MC to target tumors will aid researchers in determining the functional role of these cells in various tumors. In addition, harnessing anti-tumor agents from MC as a potential “Trojan Horse” may represent a new form of cancer cellular immunotherapy.

Human adipose tissue is a heterogeneous tissue containing the stroma-vascular (SVF) fraction that includes a large population of immune progenitor cells (23) and is a reservoir of functional MC progenitors in mice (24). We report here that large numbers of functional human MC can be expanded from human adipose tissue. The adipose-derived MC (ADMC) are phenotypically and functionally similar to connective tissue MC obtained from skin as assessed through MC-specific markers and IgE- and non-IgE-dependent mediator release assays. Importantly, ADMC sensitized with anti-HER2/neu IgE antibodies (Abs) are able to induce cell death in breast cancer cells overexpressing HER2/neu. Adipose tissue now provides researchers a new source of human MC that could be used for multiple research purposes and as a potential new strategy for cell-mediated cancer immunotherapy.

Tissue procurement and IRB approval including patient consent were obtained from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network.

Skin and adipose tissue was obtained from patients undergoing cosmetic surgery. Adipose tissue was incubated with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS), 1% fetal bovine serum, 0.04% sodium bicarbonate, 1% HEPES, 0.5% amphotericin B, 1% streptomycin/penicillin and 0.1% collagenase type 1A. Cells were placed into a 37°C orbital shaker for 1 h with constant agitation at 4 × g. The cell slurry was centrifuged at 360 × g for 15 min and adipocytes washed, suspended in medium (DMEM with 4.5 g/L glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% streptomycin/penicillin, 1% L-glutamine and 1% HEPES), and cultured for up to 7 days or until the stem cells were confluent before testing of MC-differentiating media below.

Different cell culture media were tested for their ability to induce MC differentiation of the adipose cells using X-VIVO 15 or AIM-V (Lonza, Switzerland), plus 80 ng/ml SCF (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) with or without non-specific (NS) psIgE (human myeloma IgE; a gift from Dr. Andrew Saxon, UCLA; 0.1 μg/ml). Conditioned MC media was produced using media used to culture primary human skin MC as described (12, 25). Briefly, skin MC cultures (>5 weeks) containing 80 ng/ml SCF in X-VIVO 15 were pelleted by centrifugation, supernatants removed, filtered through a 22 μm filter (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to remove any cells, and added directly to the adipose stem cells (~15 ml per 75/mm2 flask). Approximately every seven to 10 days, viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion and half of the media was collected and replaced with fresh media. Initial monitoring of MC differentiation was determined using toluidine blue staining of cytospins followed by further characterization as described below.

Flow cytometry was performed using a FACS Arial III (Becton Dickenson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Briefly, mouse anti-human Abs to FcεRI, c-kit, FcγRI, FcγRII, FcγRIII (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX), or mouse IgG isotype control MOPC (Sigma-Aldrich) were added for at least 1 h on ice, washed, and F(ab′)2-FITC-goat anti-mouse Abs (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) added for detection (26). All experiments were performed at least three times.

Immunochemistry was performed with mouse anti-human Abs to tryptase and chymase or NS mouse IgG isotype (negative) control as described (27, 28) but using Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse secondary Abs. For detection of ADMC-induced apoptosis of human breast cancer SK-BR-3 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA), cell cytospins were incubated with 1 μg/ml Alexa FluorTM 488 dye (ThermoFisher Scientific, Walnut, CA) labeled mouse anti-human tryptase (1 μg/ml; for ADMC detection; green) along with Alexa FluorTM 647 labeled mouse anti-human Ab to the active form of caspase 3 (1 μg/ml; for SK-BR-3 detection; red) or Alexa FluorTM 647 labeled isotype control for the caspase 3 Ab. To quantify the percentage of caspase 3 positive cells observed on the cytospins a total of 200 cells were counted on each slide and the number of SK-BR-3 cells positive for caspase activation was compared to the number of those not stained for caspase 3 that were not MC.

RNA was extracted from ADMC using the Qiagen RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany). Reverse Transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) was performed using the Qiagen OneStep RT-PCR kit using primers previously described to amplify short fragments of the β-actin, tryptase, chymase, c-KIT, and FcεR1α RNA (29). Cycling conditions were: 50°C for 30 min, 95°C for 15 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 53–63°C for 45 s (according to primer Tm), 72°C for 1 min and a final 10 min extension at 72°C.

The fully human anti-human HER2/neu IgE/kappa containing the variable regions of the human scFv C6MH3-B1 has been previously described (30). In addition, we also developed an anti-human HER2/neu IgE/kappa containing the variable regions of the humanized Ab trastuzumab (Herceptin®) by subcloning the variable regions of trastuzumab previously used in Ab-cytokine fusion proteins (31, 32) into the human epsilon/kappa expression vectors use to the develop the C6MH3-B1 IgE. The trastuzumab IgE and C6MH3-B1 IgE bind different epitopes of human HER2/neu. They are expressed in murine myeloma cells and the transfectomas grown in roller bottles for Ab production as described (30). The IgE Abs are purified from cell culture supernatants on an immunoaffinity column prepared with omalizumab (Xolair®) (Genentech, Inc. San Fransisco, CA, USA) (30). The extracellular domain of HER2/neu (ECDHER2) was produced as described previously (31). All proteins were quantified using the BCA Protein Assay (ThermoFisher Scientific).

To determine ADMC functional responses mediated through FcεRI, ADMC were incubated with 1 μg/ml of anti-FcεRI Abs or with 1 μg/ml anti-NP IgE for 1 h followed by NP-BSA. To determine ADMC functional responses mediated by non-IgE pathways, ADMC were incubated with 40 μg/ml Poly-L-Lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) or 10 μM A23187 (Sigma-Aldrich). Post-incubation, activation was performed for 30 min (to measure degranulation) or overnight (for cytokine analysis) and β-hexosaminidase release and TNF-α and GM-CSF production were measured as described (33–35). All experiments were performed in duplicate from four separate donors and significant differences (p < 0.05) determined using the Student t-test.

To assess the ability of anti-HER2/neu IgE sensitized ADMC to bind to HER2/neu expressing SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells, confocal imaging was used on differentially labeled, live cells. The ADMC (1.5 × 105) were sensitized with 1 μg/ml of anti-HER2/neu IgE Abs or NS psIgE followed by the addition of MitoTracker™ Green (500 nM; ThermoFisher Scientific). The ADMC were washed once in warm X-VIVO 15 and added to the adherent, human HER2/neu-positive SK-BR-3 cells that were pre-stained with MitoTracker™ Red (500 nM; ThermoFisher Scientific) in a live cell incubator affixed to a confocal microscope and images acquired over 6 h.

ADMC were sensitized with or without 1 μg/ml of anti-HER2/neu IgE or NS psIgE as above and added to human breast cancer cells expressing high levels of HER2/neu SK-BR-3 or BT-474 (a gift from Dr. Hui-Wen Lo, Wake Forest University) cells for 1 h in 24 well plates. The ratio of MC to breast cancer cells varied from 1:10 to 10:1 ADMC to breast cancer cells and mediators assessed in the supernatants. In some experiments anti-HER2/neu IgE sensitized ADMC challenged with ECDHER2 or heat-inactivated serum from patients with HER/neu positive breast cancer (Cureline, Brisbane, CA; Table 1).

Three different methods were used to assess the ability of anti-HER2/neu IgE sensitized ADMC to induce cell death of HER2/neu expressing breast cancer cells. First, ADMC (1.5 × 105) were sensitized with 1 μg/ml of anti-HER2/neu IgE or psIgE for 2 h. Breast cancer cells (5 × 104) on coverslips were labeled with 2 μM MitoTracker™ Green (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 1 h. The washed ADMC were labeled with CellTrackerTM Deep Red (which stains the cells reddish/purple under confocal; 2 μM) for 1 h, washed, and added to SK-BR-3 in medium containing 25 μg/ml of propidium iodide (PI; which stains the cells red) used to detect dead cells (36) and PI intensity measured over time. Second, SK-BR-3 were plated and incubated with CelleventTM Caspase 3/7 Green (to detect activated caspase-3/7 in apoptotic cells; ThermoFisher Scientific) for 1 h according to the manufacturers protocol. ADMC, treated with MitoTrackerTM Red (1 μg/ml), were added to the washed SK-BR-3 cells and incubated for up to 4 days. Third, cytospins of cells from separate experiments were made and used for immunofluorescence detection of apoptosis. Briefly, cytospins were fixed in methanol and incubated with Alexa FluorTM 488 dye (ThermoFisher Scientific) labeled mouse anti-human tryptase (1 μg/ml; for ADMC detection; green, for co-cultures) along with Alexa FluorTM 647 labeled mouse anti-human active caspase 3 (BD Biosciences, 1 μg/ml; for SK-BR-3 detection; red) Alexa FluorTM 647 labeled isotype Abs were used as a control for the caspase 3 Ab.

In separate experiments, cell free supernatants from optimally activated ADMC (1.3 × 106) by an anti-FcεRI Ab (1 μg/ml for 24 h; 60–70% release) were directly added to MitoTracker™ Green-labeled SK-BR-3 cells (5 × 104). In some experiments, an anti-human TNF-α Ab (5 μg/ml) was added to the supernatants to block TNF-α activity. Cell death was monitored over time through the quantification caspase 3/7-positive cells (>200) counted at the end of each experiment to obtain percentages. All confocal/live cell experiments were performed on three separate ADMC donors and significance (p < 0.05) tested using the Student's t-test.

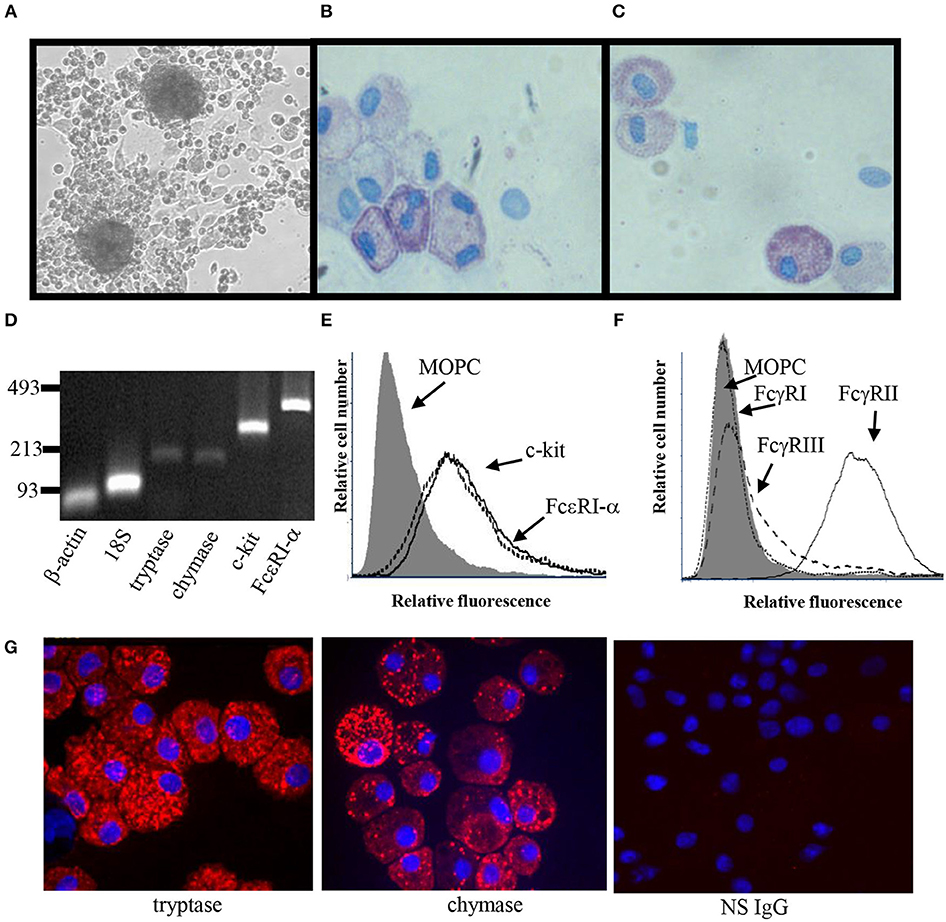

Several culture conditions were tested for their ability to induce MC differentiation (35, 37). The conditioned media from skin-derived human MC cultures was found to be optimal for ADMC differentiation (Table 2). In conditioned medium, ADMC were observed to emerge from large clumps of cells or tissue as shown in Figure 1A. After 3–4 weeks of culture, mature MC (>90% viable) were observed as demonstrated by the classical spherical, highly granulated morphology (Figure 1B) characteristic of skin-derived MC (Figure 1C). In addition, the ADMC were positive for messenger RNA to the two major MC proteases, tryptase, and chymase (Figure 1D). Furthermore, the ADMC expressed surface markers for tissue MC including FcεRI and the receptor for SCF, c-kit (Figure 1E). As previously reported with skin MC (26), ADMC express FcγRII and not FcγRI or FcγRIII (Figure 1F). As seen in Figure 1G both tryptase and chymase protein was detected using immunohistochemistry. Thus, adipose tissue has MC progenitors that can be differentiated into MC that are phenotypically similar to human connective tissue (MCTC) (38) based on these characteristics. Representative numbers of ADMC obtained from surgical specimens are shown in Table 3.

Figure 1. Phenotypic characterization of ADMC. (A) Light microscopy of ADMC. ADMC cultures demonstrating large cell/tissue clumps from which the MC differentiate (20 × magnification). Cytospins of adipose-derived (B) or skin MC (C) were stained with toluidine blue. (D) Gene expression was measured using RT-PCR on total RNA. β-actin and 18S ribosomal subunit primers were controls (Ladder: bp). (E) Surface expression of MC-specific markers by flow cytometry. ADMC were incubated with mouse anti-c-Kit/CD117 (dashed line), FcεRIα chain (solid line), or isotype control mouse IgG (gray) for 2 h on ice, washed, and F(ab′)2-FITC-goat anti-mouse added for 1 h. (F) Fcγ receptor expression on ADMC. ADMC were incubated with mouse anti human FcγRI (dotted), FcγRII (solid line), FcγRIII (dashed), or isotype control mouse IgG (gray) for 2 h on ice, washed, and FITC-labeled anti-mouse F(ab′)2 added for 1 h. (G) Immunohistochemistry of ADMC with MC-specific markers. Anti-tryptase, anti-chymase, or NS IgG Ab were incubated overnight on cytospin cells, washed and incubated with Cy3-secondary Abs and Hoechst dye (blue nuclei) and visualized using confocal microscopy. Figures are representative of cells derived from three different human subjects.

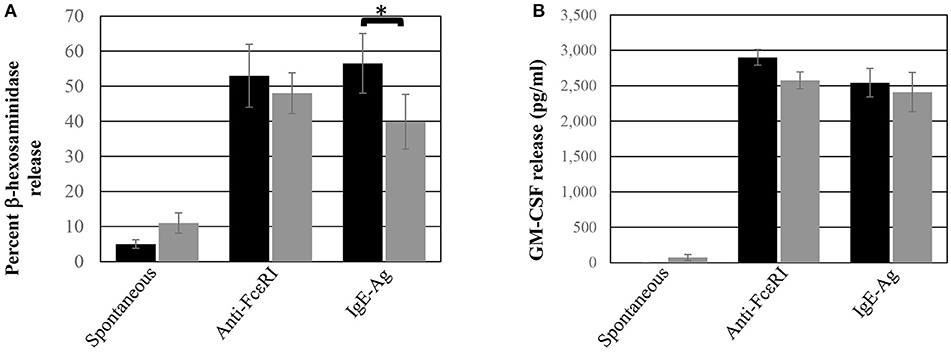

The functional response of ADMC was compared to skin-derived MC. As seen in Figure 2, ADMC degranulated (Figure 2A) and produced cytokines (Figure 2B) in response to FcεRI engagement. Cytokine release by ADMC and skin MC was similar in response to FcεRI-dependent stimuli averaging 2,850 and 2,600 pg/ml of GM-CSF in skin MC and ADMC, respectively. A similar degranulatory response with ADMC was observed using non-FcεRI-dependent stimuli Poly-L-Lysine and A23187 (Supplemental Figure 1). Taken together, the ADMC are functionally similar to skin-derived MC in response to FcεRI-dependent and FcεRI-independent stimuli.

Figure 2. ADMC functional response. Human skin MC (black box) or ADMC (gray box; 106) were challenged with or without (spontaneous release) 1 μg/ml anti-FcεRI Abs or anti-NP IgE + antigen (IgE-Ag) and degranulation (A) or GM-CSF production (B) assessed in the supernatants. Error bars represent ± SD. *p < 0.05 comparing skin MC vs. ADMC release. Figure is representative of cells derived from two different donors.

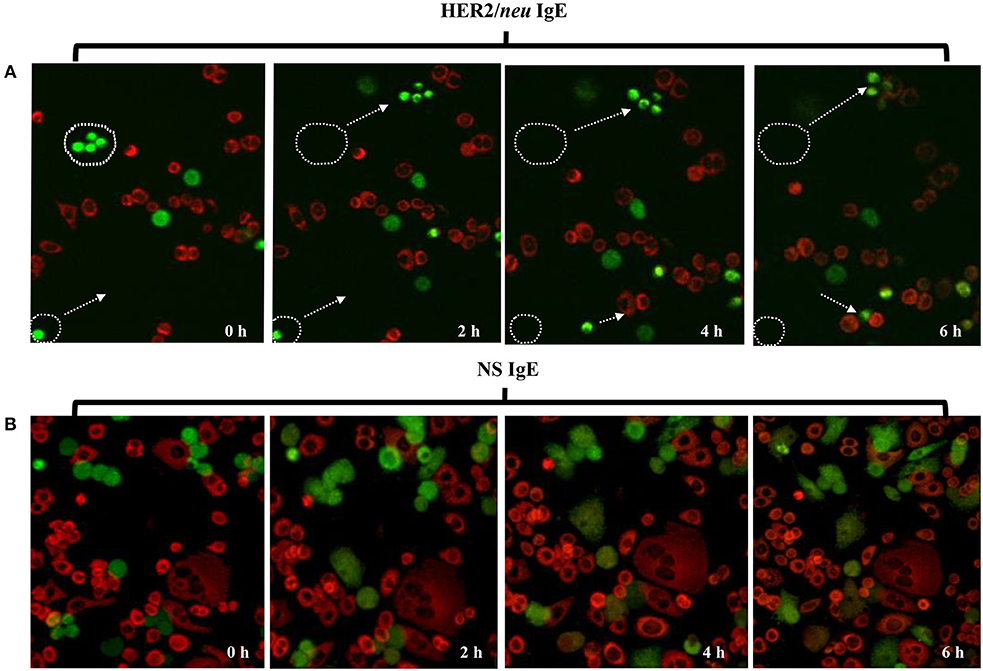

The ability of ADMC sensitized with the anti-HER2/neu IgE to bind HER2/neu–positive SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells was investigated. As seen in Figure 3A, the ADMC sensitized with the anti-HER2/neu IgE (green) bound to HER2/neu-positive SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells (red) as demonstrated in the time lapse pictures and video (Supplemental Video 1). However, ADMC sensitized with a NS IgE did not target or bind to the SK-BR-3 cells (Figure 3B). These results demonstrate that the anti-HER2/neu-IgE mediates the interaction between ADMC and HER2/neu-positive breast cancer cells.

Figure 3. Time lapse, confocal microscopy of ADMC binding to breast cancer cells. ADMC (105-106) were sensitized with 1 μg/ml of trastuzumab IgE (A, 20X) or NS IgE (B, 40X) followed by MitoTracker™ Green. The MitoTracker™ Green-loaded ADMC were added to adherent SK-BR-3 (105-106) that had been pre-stained with MitoTracker™ Red and time lapse video taken over 6 h. The white circular boundaries and arrows represent starting point and tracking of ADMC (green) at time 0 to SK-BR-3 (red) binding over the 6 h. 20X magnification was used to capture the cellular tracking (start and stop) that can be observed in accompanying video.

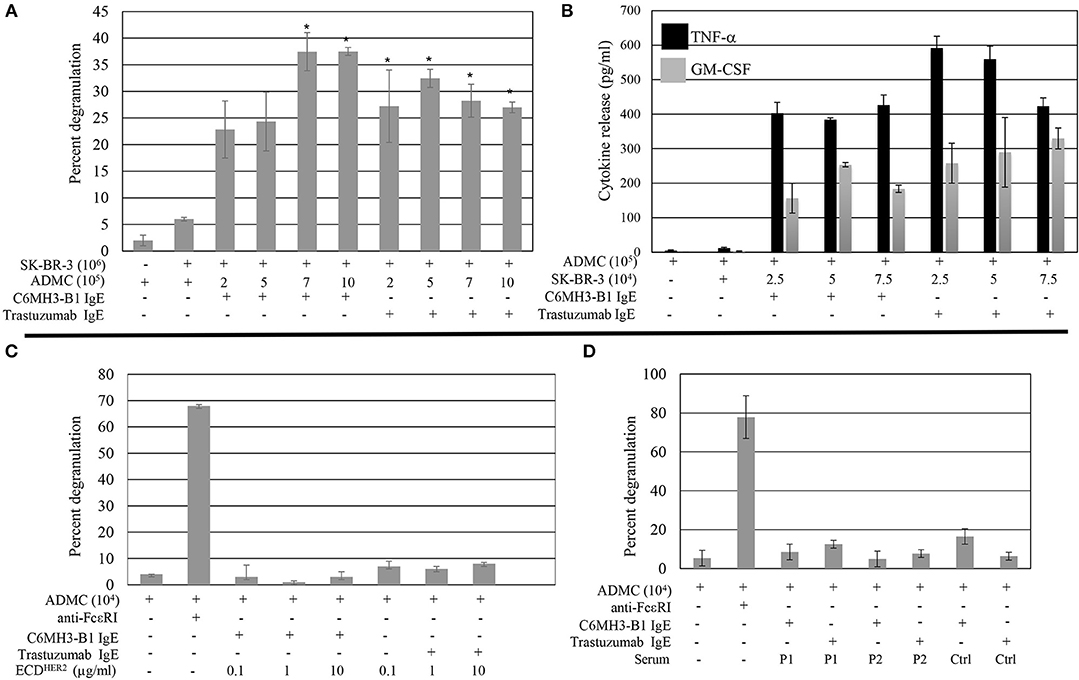

ADMC must release their mediators upon FcεRI challenge at the site of the tumor to be effective anti-tumor agents. Thus, the ability of ADMC sensitized with the anti-HER2/neu IgE to degranulate in the presence of breast cancer cells was investigated. ADMC were sensitized with one of two anti-HER2/neu IgE Abs recognizing different epitopes (trastuzumab IgE or C6MH3-B1 IgE). Varying ADMC cell numbers were incubated with SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells and mediator release assessed in the medium. As seen in Figure 4, ADMC sensitized with anti-HER2/neu IgE induced significant (p < 0.05) mediator release through FcεRI when co-incubated with the HER2/neu-positive SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells. The ADMC degranulated to release pre-stored mediators (Figure 4A), as well as newly formed mediators TNF-α and GM-CSF (Figure 4B). Another HER2/neu-positive breast cancer cell line, BT-474, also induced degranulation and cytokine production optimally at a ratio of 1:2 (degranulation) and 1:0.5 (cytokine release) ADMC:BT-474 (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 4. Breast cancer cell-induced ADMC mediator release. ADMC were sensitized with 1 μg/ml anti-HER/neu IgE (clone C6MH3-B1 IgE or trastuzumab IgE), washed, and incubated with SK-BR-3 cells and degranulation (A) or cytokine release (B) assessed. Data are from a single experiment representative of experiments performed on cells derived from four separate donors. Error bars represent ± SD. *p < 0.05 Compared with non-IgE (spontaneous) release. All values in (B) are significant compared to spontaneous release. (C) ECDHER2 does not induce ADMC mediator release. ADMC were sensitized with 1 μg/ml anti-HER/neu IgE as in (A), washed, and incubated with ECDHER2 and mediator release assessed. As a control, optimal concentrations of 1 μg/ml anti-FcεRI Ab were tested in parallel. Each condition was tested in triplicate and is representative from two separate ADMC donors. Error bars represent ±SD. (D) Sera from HER2/neu positive breast cancer patients does not induce ADMC degranulation. Heat inactivated sera from two separate HER2/neu positive breast cancer patients (P1 and P2; see Table 1) or normal control serum (Ctrl) was used to challenge anti-HER/neu IgE (C6MH3-B1 IgE or trastuzumab IgE) sensitized ADMC and β-hexosaminidase release measured as described. Background levels of β-hexosaminidase naturally found in the sera was subtracted from values. Experiment is representative of two separate ADMC preparations each done in duplicate. Error bars represent ± SD.

The above results suggest the possibility of using ADMC armed with IgE Abs can trigger degranulation in the presence of HER2/neu expressing cancer cells and thus, the potential of using this strategy for cancer therapy via the release of MC mediators. However, a potential concern of the systemic administration of ADMC sensitized with an anti-HER2/neu IgE is the possible induction of a systemic anaphylactic reaction as patients with HER2/neu breast cancer can have elevated levels of circulating ECDHER2 in the blood (39, 40). The IgE Abs are not expected to induce FcεRI cross-linking when complexed with soluble antigen (ECDHER2), given the mono-epitopic nature of this interaction and the fact that ECDHER2 does not form homodimers in solution (41, 42). To address this concern, the ability of ECDHER2 to induce FcεRI-mediator release was examined. As described previously (30), ECDHER2 in the presence of the anti-HER2/neu IgE Abs did not induce degranulation, while anti-FcεRI Abs induced release (Figure 4C). Furthermore, serum from two separate HER2/neu positive breast cancer patients did not induce ADMC degranulation (Figure 4D). These results suggest that the anti-HER2/neu IgE-sensitized ADMC will not induce a systemic anaphylactic response in vivo and will only release mediators upon encountering HER2/neu on breast cancer cells.

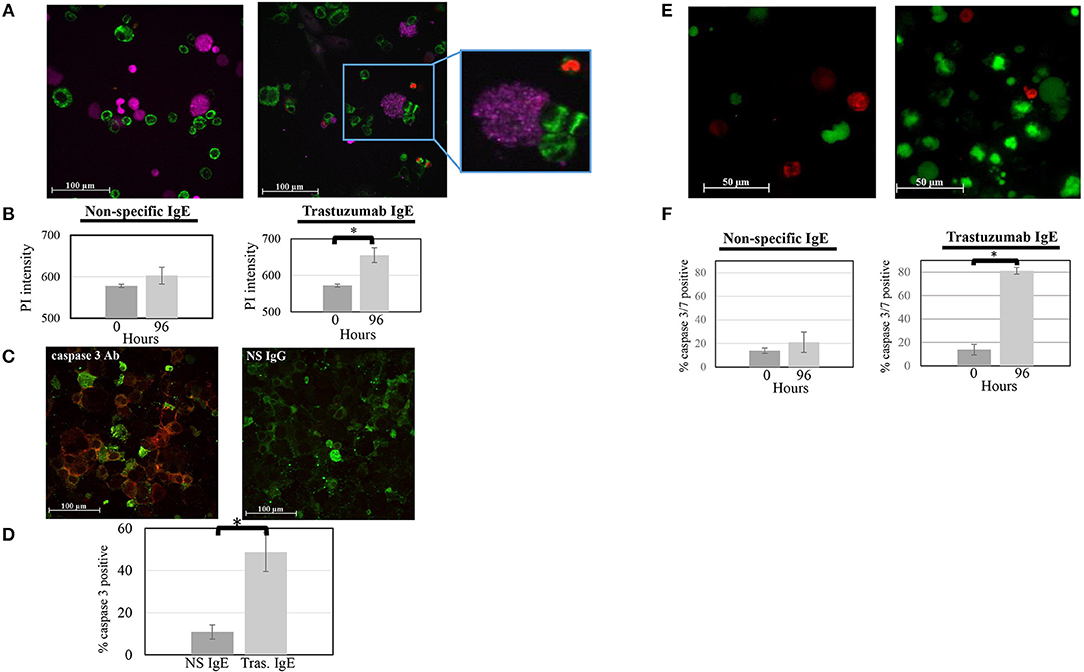

The ability of ADMC to induce breast cancer cell death was investigated. ADMC sensitized with the anti-HER2/neu IgE were added to SK-BR-3 cells in medium containing PI to discriminate dead cells from live cells (36). As seen in Figure 5A, binding of anti-HER2/neu–sensitized (trastuzumab IgE) ADMC to SK-BR-3 cells induced significant cell death of the breast cancer cells as assessed by the uptake and visualization (red) of the PI in the SK-BR-3 cells but not the ADMC. Quantification of the PI signal in Figure 5B demonstrated significant breast cancer cell killing after 4 days (p = 0.0003). Sensitization of the ADMC with NS IgE did not result in significant SK-BR-3 cell death. Similarly, anti-HER2/neu IgE C6MH3-B1 sensitized ADMC induced significant (p = 0.032) SK-BR-3 cell death (data not shown). In addition, ADMC added to the SK-BR-3 over 4 days revealed significant (p = 0.003) breast cancer cell death, but not ADMC death (anti-tryptase labeled), as indicated by immunostaining of the SK-BR-3 with an Ab specific for the apoptotic enzyme caspase 3 (Figures 5C,D). Lastly, a significant (p = 0.0004) increase in caspase 3/7-positive breast cancer cells was confirmed at day 4 when anti-HER2/neu–sensitized ADMC were co-incubated (Figures 5E,F). The tumor cell specificity of the responses was verified as the NS isotype control IgE did not affect breast cancer cell viability. These experiments indicate ADMC binding to SK-BR-3 results in ADMC activation through FcεRI capable of inducing significant SK-BR-3 cell death.

Figure 5. ADMC killing of human breast cancer cells measured as evidence by the uptake of PI. (A) CellTracker™-red labeled ADMC (7.5 × 104; shown here as purple cells) were sensitized with 1 μg/ml anti-HER2/neu IgE (clone trastuzumab), washed, and incubated with MitoTracker™-green-stained SK-BR-3 (105) in culture medium containing PI and images taken before (A; left) and after (A; right) 96 h. The call out box shows a representative ADMC being activated through loss of granularity over time. (Mag 20x). (B) Quantification of overall PI fluorescence before and after incubation. The percent of PI-positive cells was counted in culture. The *p = 0.0003 SK-BR-3 cell death at day 4 compared to day 0 when ADMC where sensitized with anti-HER2/neu IgE. No cell death was observed with the NS IgE. (C) ADMC-induced breast cancer cell apoptosis. Anti-HER2/neu IgE-sensitized ADMC (7.5 × 104) were incubated with SK-BR-3 (1 × 105) for 72 h, cytospins made, fixed, and incubated with Alexa FluorTM 488 labeled, mouse anti-human tryptase (left; green) along with Alexa FluorTM 647 labeled, mouse anti-human caspase 3 (red) or Alexa FluorTM 647 labeled, isotype control IgG for caspase 3 Ab (right). (D) Quantification of overall Alexa FluorTM 647 fluorescence before and after incubation. *p = 0.002 SK-BR-3 apoptosis comparing psIgE and anti-HER2/neu IgE-sensitized cells at day 4 from three experiments. (E) ADMC killing of human breast cancer cells measured by caspase 3/7 activation Mitotracker™-red labeled ADMC (7.5 × 104; shown here as red cells) were sensitized with 1 μg/ml anti-HER2/neu IgE (clone trastuzumab), washed, and incubated with caspase 3/7 green-labeled SK-BR-3 (105 and images taken before (A, left) and after (A; right) 96 h. (F) Quantification of overall caspase 3/7 fluorescence before and after incubation. The percent of caspase 3/7-positive cells was counted in culture. *p = 0.004 SK-BR-3 cell death at day 4 compared to day 0 when ADMC where sensitized with anti-HER2/neu IgE. No SK-BR-3 cell death was observed with the NS IgE.

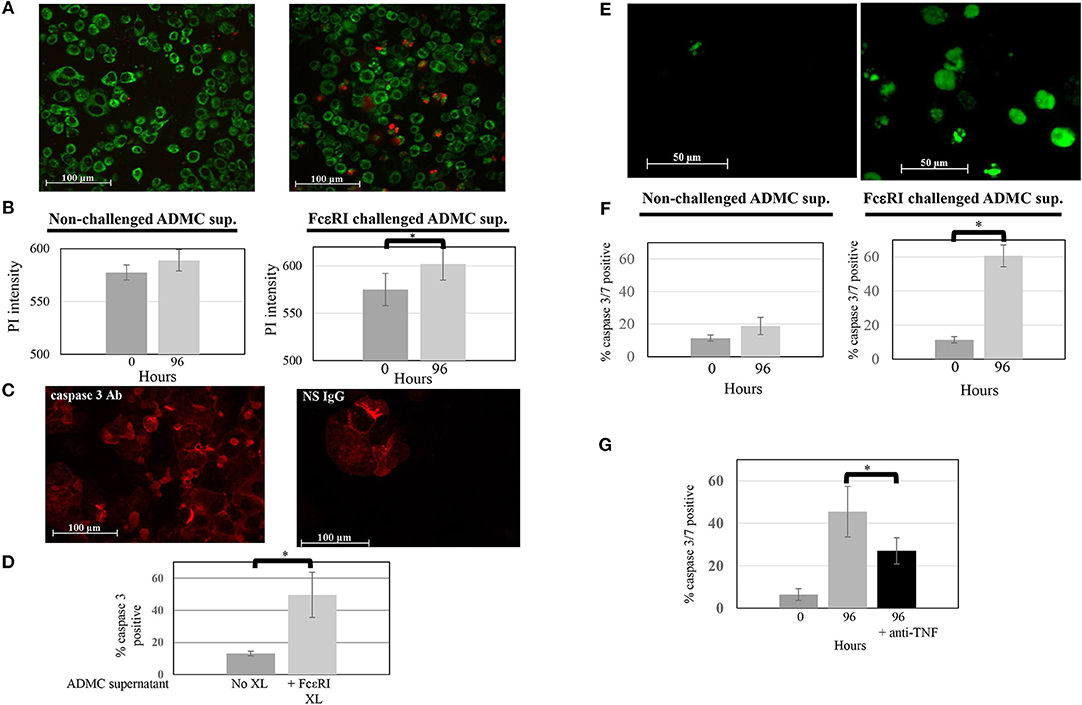

As shown above, ADMC produce mediators that induce significant breast cancer cell death upon FcεRI cross-linking using a tumor-targed IgE. The ability of the mediators obtained from FcεRI-activated ADMC alone to induce SK-BR-3 cell death was then examined. As seen in Figures 6A,B, medium alone (not containing ADMC) from optimally activated ADMC incubated with SK-BR-3 cells induced significant (p = 0.009) SK-BR-3 cell death when incubated for 4 days. Further, when the media from optimally activated FcεRI ADMC were added to the SK-BR-3, there was a significant (p = 0.01) increase of apoptotic cells as evidenced by the increase in active caspase 3 (Figures 6C,D) indicating cell death of the breast cancer cells as in Figure 5. A significant (p = 0.0002) increase in activated caspase 3/7-positive breast cancer cells was confirmed at day 4 when SK-BR-3 cells were incubated with supernatants from ADMC activated through FcεRI (Figures 6E,F). Blocking TNF-α activity significantly prevented SK-BR-3 cell death (Figure 6G).

Figure 6. Mediators from FcεRI-challenged ADMC induce SK-BR-3 cell killing. (A) ADMC (1.3 × 106) were challenged with optimal concentrations of anti-FcεRI stimuli (70% release) for 24 h and supernatants (XL media; no cells) from these ADMC were incubated with the MitoTracker™ green-stained SK-BR-3 (105) in culture medium containing optimal concentrations of PI and images taken before (left) and after (right) 96 h. (B) Quantification of overall PI fluorescence before and after incubation. The increased number of red cells indicates breast cancer cell death as indicated by the PI (red) and quantified in showing overall PI fluorescence before and after incubation. Graph represents average PI intensity from two separate experiments (±SD; *p = 0.0008). (C) Mediators from FcεRI-challenged ADMC induce human breast cancer cell apoptosis. The same media from anti-FcεRI challenged ADMC were incubated with SK-BR-3 (105) for 72 h, cytospins prepared, fixed, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 647 labeled, anti-human caspase 3 (left) or Alexa Fluor 647 labeled, isotype control Ab for caspase 3 (right). Representative panels are shown. (D) Quantification of overall Alexa FluorTM 647 fluorescence before and after incubation with supernatants from FcεRI activated ADMC. *p = 0.01 SK-BR-3 apoptosis comparing anti-HER2/neu IgE-sensitized cells at day 0 vs. day 4 from three experiments. (E) Mediators from FcεRI-challenged ADMC induce SK-BR-3 cell killing measured by caspase 3/7. ADMC (1.8 × 106) were challenged with optimal concentrations of anti-FcεRI stimuli (63% release) for 24 h and supernatants (no cells) from these ADMC were incubated with SK-BR-3 (105) and caspase 3/7 green images taken before (left) and after (right) 96 h. The increased number of green cells indicates breast cancer cell death as indicated by the caspase 3/7 and quantified by counting live vs. dead cells before and after incubation. (F) Graph represents average percentage of cells from two separate experiments (±SD; *p = 0.002). (G) Blocking TNF-α significantly reduces SK-BR-3 cell death. SK-BR-3 were treated and quantified as in (C) except anti-TNF-α Ab were added during the incubation time. *p = 0.028 Decrease in SK-BR-3 cell death when anti-TNF-α Ab are added to the supernatants from anti-FcεRI stimulated ADMC.

Here we report that functional MC can be differentiated from adipose tissue obtained from human subjects undergoing cosmetic surgery procedures. This research discovery is notable as there is an ever-present need for new sources of human MC for research, given the differences between human and rodent MC phenotypes and functional responses (5–7). This incongruence has led to confusion and inconsistent findings in the field of MC biology and allergic mechanisms (8, 43, 44), especially in Fc receptor expression and function (26). While a plethora of human “mast cell” lines exist, each is wrought with phenotypic and functional anomalies compared to primary human MC (8). Primary human MC can be obtained from cord blood (45, 46), bone marrow (45), fetal liver (47), peripheral blood (48), and human tissue (e.g., skin) (11). For autologous applications, MC can be obtained from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells in the blood (49), but not in sufficient numbers for most applications. For example, the total MC number generated from 1.0 × 108 lymphocytapheresis or peripheral blood mononuclear cells averaged 2.5 × 106 and 2.4 × 106, respectively (50). Large numbers of enriched CD34+ cells can also be obtained commercially to increase the quantities of subsequent MC following GM-CSF injection, apheresis, and subsequent positive selection with magnetic beads has been described (48). However, given the various protocols for differentiation the MC obtained from these methods are not fully mature and functional. In this report, approximately 5.1 × 105 ADMC were obtained per ml of liposuction compared to 4.8 × 105 MC per gram of skin. Thus, ADMC can be utilized as a relatively rapid, more cost effective, and efficient method for studying MC biology and function. Current efforts are focused on identifying the molecule(s) in the conditioned media that are responsible for the ADMC differentiation and maturation.

The role of MC in cancer is controversial as to whether they are beneficial, harmful, or innocuous and is dependent on the tumor type and location within the tumor in humans and animal models (16, 18, 51–53). Animal models, mostly MC-deficient mice, have suggested that MC and their mediators play a pro-tumorigenic role (52). Yet, MC-deficient mouse models have paradoxically indicated that in certain tumors, and even in the same models, MC appear to play a protective role (52, 54). These contradictory results might reflect differences in the stage, incongruences between animal models (i.e., MC knockout through kit mutation vs. Cre mutation) and/or rodent MC lines vs. human MC, grade, and subtypes of tumor; as well as the different methods to identify MC. While in certain human cancers the presence of MC is associated with poor prognosis, in other malignancies, such as breast and colorectal cancer, the presence of MC has been associated with a favorable clinical prognosis depending on their location (55–58). Currently, multiple questions remain as to the nature of the role of MC in cancer pathogenesis.

Human MC are unique in that they have pre-stored TNF-α stores within their granules (59, 60). Furthermore, human MC release copious amounts (2,500–4,000 pg/ml from 105 cells) of GM-CSF upon FcεRI stimulation (19, 20). Indeed, the above blocking experiments suggest TNF-α activity is the major component in FcεRI-activated ADMC supernatants that induces SK-BR-3 apoptosis (Figure 6G). TNF-α is an anti-cancer agent shown to suppress tumor cell proliferation, induce tumor regression, and used as an adjuvant that enhances the anti-cancer effect of chemotherapeutic agents (61–63). GM-CSF is also being investigated as an anti-breast cancer therapeutic, including its use in combination strategies with other immunotherapies (21, 64–67). There are over 50 clinical trials completed or underway examining the beneficial clinical effects of GM-CSF (www.clinicaltrials.gov). In addition to GM-CSF and TNF-α, MC also store and release several other potential anti-tumor mediators including reactive oxygen species (ROS), prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), interleukin-9 (IL-9), and heparin (2, 13). In one study cord blood-derived MC and eosinophils, sensitized with an anti-CD20 IgE, were shown to kill CD20-positive cancer cells (68). Thus, it may be possible that even in cases where MC may act favoring the tumors in certain cases through a controlled release of certain agents, they may have anti-tumor activity upon an IgE-mediated strong and immediate release of their granular content. Given that these MC mediators may have unwanted side effects, further in vivo studies are needed to address this topic.

There are 21 FDA approved Abs on the market to treat various cancers (69). While all are of the human IgG class, IgE has several potential advantages over Abs of the IgG class, such as the IgE-FcεRI high affinity interaction, which allows a more effective arming of effector cells without losing surface-bound Abs (30, 70, 71) and the low serum levels of IgE that result in less competition for FcR occupancy (70–72). The first clinical trial (www.clinicaltrials.gov; clinical trial number NCT02546921) is currently underway in patients with advanced solid tumors to examine the safety of a mouse/human chimeric IgE Ab (MOv18 IgE), specific for the tumor-associated antigen folate receptor-α, which has exhibited superior anti-tumor efficacy for IgE compared with IgG1 in animal models (73, 74).

Three separate experimental approaches were used above to demonstrate ADMC, and mediators from FcεRI-challenged ADMC, have anti-tumor activity and suggests the possibility of using autologous (or allogeneic) MC in cancer immunotherapy. There are several advantages for this potential technology. First, mature, functional, autologous or allogeneic MC can be obtained in quantities necessary for patient infusion. Second, the availability of IgE Abs with human constant regions (chimeric, humanized, and fully human) targeting tumor antigens has grown substantially (70, 72). Third, the high affinity binding between IgE and FcεRI is very stable with a long half-life resulting in an effective arming of MC, which would be able to target the tumor and so doing induce tumor cell death. The presence of dead tumor cells would facilitate their uptake and presentation of tumor antigens by antigen presenting cells (APC), eliciting an adaptive broad-spectrum anti-tumor immunity. This would increase due to MC local release of GM-CSF (19, 20) and potentially the release of suppressors of regulatory T-cell (Tregs) function as reported for IgE degranulation in murine MC (75). Lastly, unlike other immune cells currently being used for cancer immunotherapy (76), ADMC sensitized with anti-HER2/neu IgE are equipped to kill tumor cells without genetic reprogramming, which is time consuming and expensive (76).

In conclusion, it is shown that adipose tissue represents an alternative source for human MC that are phenotypically and functionally similar to primary MC. This new source of MC, ADMC, can be used in research to address fundamental questions in MC biology and to study IgE Abs including those targeting tumor antigens. Importantly, ADMC exhibit tumoricidal activity when armed with IgE Abs specific for a tumor antigen. Future studies are needed to evaluate the utility of ADMC, sensitized with tumor targeting IgE, to examine anti-tumor activity and toxicity in in vivo cancer models to further validate this potential new cancer immunotherapy strategy.

JP, ME, and MF conducted the experiments which were conceived by CK. MP, and TD-W developed the anti-HER2/neu IgE antibodies and helped design the studies. JP, ME, TD-W, MP, AD, and CK assisted in the preparation of this manuscript.

This work was supported in part by NIH/NCI R01CA181115 and R21CA193953 (MP and TD-W) and UNCG Giant Steps grant (CK).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00138/full#supplementary-material

MC, mast cells; Abs, antibodies; ADMC, adipose-derived mast cells; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; SCF, stem cell factor; PI, propidium iodide; APC, antigen presenting cells; Tregs, Regulatory T cells; NS, non-specific.

1. Schwartz LB, Huff TF. Biology of mast cells and basophils. In: Middleton E Jr., Reed CE, Ellis EF, Adkinson NF Jr., Yunginger JW, Busse WW, editors. Allergy: Principals and Practice, Vol. 4. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book, Inc. (1993). p 135–68.

2. Mukai K, Tsai M, Saito H, Galli SJ. Mast cells as sources of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors. Immunol Rev. (2018) 282:121–50. doi: 10.1111/imr.12634

3. Epstein MM. Do mouse models of allergic asthma mimic clinical disease? Int Arch Allergy Immunol. (2004) 133:84–100. doi: 10.1159/000076131

4. Finkelman FD. Anaphylaxis: lessons from mouse models. J.Allergy Clin.Immunol. (2007) 120:506–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.033

5. Mestas J, Hughes CC. Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology. J Immunol (2004) 172:2731–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2731

6. Rodewald HR, Feyerabend TB. Widespread immunological functions of mast cells: fact or fiction? Immunity (2012) 37:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.007

7. Passante E. Mast cell and basophil cell lines: a compendium. Methods Mol Biol. (2014) 1192:101–13. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1173-8_8

8. Bischoff SC. Role of mast cells in allergic and non-allergic immune responses: comparison of human and murine data. Nat Rev Immunol. (2007) 7:93–104. doi: 10.1038/nri2018

9. Kirshenbaum AS, Kessler SW, Goff JP, Metcalfe DD. Demonstration of the origin of human mast cells from CD34 + bone marrow progenitor cells. J Immunol. (1991) 146:1410–5.

10. Jensen BM, Swindle EJ, Iwaki S, Gilfillan AM. Generation, isolation, and maintenance of rodent mast cells and mast cell lines. Curr Protoc Immunol. (2006) Chapter 3:Unit 3.23. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0323s74

11. Kambe N, Kambe M, Chang HW, Matsui A, Min HK, Hussein M, et al. An improved procedure for the development of human mast cells from dispersed fetal liver cells in serum-free culture medium. J Immunol Methods (2000) 240:101–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(00)00174-5

12. Kambe N, Kambe M, Kochan JP, Schwartz LB. Human skin-derived mast cells can proliferate while retaining their characteristic functional and protease phenotypes. Blood (2001) 97:2045–52. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.7.2045

13. Varricchi G, Galdiero MR, Loffredo S, Marone G, Iannone R, Marone G, et al. Are mast cells MASTers in cancer? Front Immunol. (2017) 8:424. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00424

14. Ribatti D. Mast cells in lymphomas. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2016) 101:207–12. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.03.016

15. Aaltomaa S, Lipponen P, Papinaho S, Kosma VM. Mast cells in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. (1993) 13: 785–8.

16. Dalton DK, Noelle RJ. The roles of mast cells in anticancer immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2012) 61:1511–20. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1246-0

17. Varricchi G, Galdiero MR, Marone G, Granata F, Borriello F, Marone G. Controversial role of mast cells in skin cancers. Exp Dermatol. (2017) 26:11–7. doi: 10.1111/exd.13107

18. Wasiuk A, de Vries VC, Nowak EC, Noelle RJ. Mast cells in allergy and tumor disease. In: Penichet ML, Jensen-Jarolim E, editors. Cancer and IgE: Introducing the Concept of Allergooncology. New York, NY: Springer (2010). p. 137–58.

19. Dellinger AL, Cunin P, Lee D, Kung AL, Brooks DB, Zhou Z, et al. Inhibition of inflammatory arthritis using fullerene nanomaterials. PLoS ONE (2015) 10:e0126290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126290

20. Norton SK, Dellinger A, Zhou Z, Lenk R, Macfarland D, Vonakis B, et al. A new class of human mast cell and peripheral blood basophil stabilizers that differentially control allergic mediator release. Clin Transl Sci. (2010) 3:158–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00212.x

21. Yan WL, Shen KY, Tien CY, Chen YA, Liu SJ. Recent progress in GM-CSF-based cancer immunotherapy. Immunotherapy (2017) 9:347–60. doi: 10.2217/imt-2016-0141

22. Roberts NJ, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Jr., Holdhoff M. Systemic use of tumor necrosis factor alpha as an anticancer agent. Oncotarget (2011) 2:739–51. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.344

23. Feisst V, Meidinger S, Locke MB. From bench to bedside: use of human adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cells Cloning (2015) 8: 149–62. doi: 10.2147/SCCAA.S64373

24. Poglio S, De Toni-Costes F, Arnaud E, Laharrague P, Espinosa E, Casteilla L, et al. Adipose tissue as a dedicated reservoir of functional mast cell progenitors. Stem Cells (2010) 28:2065–72. doi: 10.1002/stem.523

25. Kepley CL. Antigen-induced reduction in mast cell and basophil functional responses due to reduced Syk protein levels. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. (2005) 138:29–39. doi: 10.1159/000087355

26. Zhao W, Kepley CL, Morel PA, Okumoto LM, Fukuoka Y, Schwartz LB. Fc gamma RIIa, not Fc gamma RIIb, is constitutively and functionally expressed on skin-derived human mast cells. J Immunol. (2006) 177:694–701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.694

27. Dellinger A, Zhou Z, Norton SK, Lenk R, Conrad D, Kepley CL. Uptake and distribution of fullerenes in human mast cells. Nanomedicine (2010) 6:575–82. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.01.008

28. Irani AM, Bradford TR, Kepley CL, Schechter NM, Schwartz LB. Detection of MCT and MCTC types of human mast cells by immunohistochemistry using new monoclonal anti-tryptase and anti-chymase antibodies. J Histochem Cytochem. (1989) 37:1509–15.

29. Xia HZ, Kepley CL, Sakai K, Chelliah J, Irani AM, Schwartz LB. Quantitation of tryptase, chymase, Fc epsilon RI alpha, and Fc epsilon RI gamma mRNAs in human mast cells and basophils by competitive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. J Immunol. (1995) 154:5472–80.

30. Daniels TR, Leuchter RK, Quintero R, Helguera G, Rodriguez JA, Martinez-Maza O, et al. Targeting HER2/neu with a fully human IgE to harness the allergic reaction against cancer cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2012) 61:991–1003. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1150-z

31. Dela Cruz JS, Lau SY, Ramirez EM, De Giovanni C, Forni G, Morrison SL, et al. Protein vaccination with the HER2/neu extracellular domain plus anti-HER2/neu antibody-cytokine fusion proteins induces a protective anti-HER2/neu immune response in mice. Vaccine (2003)21:1317–26.

32. Ortiz-Sanchez E, Helguera G, Daniels TR, Penichet ML. Antibody-cytokine fusion proteins: applications in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. (2008) 8:609–32. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.5.609

33. Dellinger A, Zhou Z, Lenk R, MacFarland D, Kepley CL. Fullerene nanomaterials inhibit phorbol myristate acetate-induced inflammation. Exp Dermatol. (2009) 18:1079–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00904.x

34. Norton SK, Wijesinghe DS, Dellinger A, Sturgill J, Zhou Z, Barbour S, et al. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids are involved in the C(70) fullerene derivative-induced control of allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2012) 130:761–769.e762. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.023

35. Zhao W, Oskeritzian CA, Pozez AL, Schwartz LB. Cytokine production by skin-derived mast cells: endogenous proteases are responsible for degradation of cytokines. J Immunol. (2005) 175:2635–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2635

36. Sasaki DT, Dumas SE, Engleman EG. Discrimination of viable and non-viable cells using propidium iodide in two color immunofluorescence. Cytometry (1987) 8:413–20. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990080411

37. Gomez G, Jogie-Brahim S, Shima M, Schwartz LB. Omalizumab reverses the phenotypic and functional effects of IgE-enhanced Fc epsilonRI on human skin mast cells. J Immunol. (2007) 179:1353–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1353

38. Irani AA, Schechter NM, Craig SS, DeBlois G, Schwartz LB. Two types of human mast cells that have distinct neutral protease compositions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1986) 83:4464–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4464

39. Lennon S, Barton C, Banken L, Gianni L, Marty M, Baselga J, et al. Utility of serum HER2 extracellular domain assessment in clinical decision making: pooled analysis of four trials of trastuzumab in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2009) 27:1685–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8351

40. Tse C, Gauchez AS, Jacot W, Lamy PJ. HER2 shedding and serum HER2 extracellular domain: biology and clinical utility in breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. (2012) 38:133–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.03.008

41. Ferguson KM, Darling PJ, Mohan MJ, Macatee TL, Lemmon MA. Extracellular domains drive homo- but not hetero-dimerization of erbB receptors. EMBO J. (2000) 19:4632–43. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4632

42. Kovacs E, Zorn JA, Huang Y, Barros T, Kuriyan J. A structural perspective on the regulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Annu Rev Biochem. (2015) 84:739–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034402

43. Zschaler J, Schlorke D, Arnhold J. Differences in innate immune response between man and mouse. Crit Rev Immunol. (2014) 34:433–454. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.2014011600

44. Galli SJ, Tsai M, Piliponsky AM. The development of allergic inflammation. Nature (2008) 454(7203):445–54. doi: 10.1038/nature07204

45. Furitsu T, Arai N, Ishizaka T. Co-culture of progenitors in human bone marrow (BM) and cord blood with human fibroblast for the differentiation of human mast cells. Fed Proc. (1989) 3:A787.

46. Mitsui H, Furitsu T, Dvorak AM, Irani AA, Schwartz LB, Inagaki N, et al. Development of human mast cells from umbilical cord blood cells by recombinant human and murine C-kit ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (1993) 90:735–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.735

47. Nilsson G, Forsberg K, Bodger MP, Ashman LK, Zsebo KM, Ishizaka T, et al. Phenotypic characterization of stem cell factor-dependent human foetal liver-derived mast cells. Immunology (1993) 79:325–30.

48. Radinger M, Jensen BM, Kuehn HS, Kirshenbaum A, Gilfillan AM. Generation, isolation, and maintenance of human mast cells and mast cell lines derived from peripheral blood or cord blood. Curr Protoc Immunol. (2010) Chapter 7:Unit 7.37. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0737s90

49. Kirshenbaum AS, Goff JP, Semere T, Foster B, Scott LM, Metcalfe DD. Demonstration that human mast cells arise from a progenitor cell population that is CD34(+), c-kit(+), and expresses aminopeptidase N (CD13). Blood (1999) 94:2333–42.

50. Yin Y, Bai Y, Olivera A, Desai A, Metcalfe DD. An optimized protocol for the generation and functional analysis of human mast cells from CD34(+) enriched cell populations. J Immunol Methods (2017) 448:105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2017.06.003

51. Ribatti D, Crivellato E. Mast cells, angiogenesis and cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2011) 716:270–88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9533-9_14

52. Maciel TT, Moura IC, Hermine O. The role of mast cells in cancers. F1000Prime Rep. (2015) 7:09. doi: 10.12703/P7-09

53. Wasiuk A, de VV, Hartmann K, Roers A, Noelle RJ. Mast cells as regulators of adaptive immunity to tumours. Clin Exp Immunol. (2009) 155:140–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03840.x

54. Pittoni P, Tripodo C, Piconese S, Mauri G, Parenza M, Rigoni A, et al. Mast cell targeting hampers prostate adenocarcinoma development but promotes the occurrence of highly malignant neuroendocrine cancers. Cancer Res. (2011) 71:5987–97. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1637

55. Dabiri S, Huntsman D, Makretsov N, Cheang M, Gilks B, Bajdik C, et al. The presence of stromal mast cells identifies a subset of invasive breast cancers with a favorable prognosis. Mod Pathol. (2004) 17:690–5. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800094

56. Sinnamon MJ, Carter KJ, Sims LP, Lafleur B, Fingleton B, Matrisian LM. A protective role of mast cells in intestinal tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis (2008) 29:880–6. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn040

57. Johansson A, Rudolfsson S, Hammarsten P, Halin S, Pietras K, Jones J, et al. Mast cells are novel independent prognostic markers in prostate cancer and represent a target for therapy. Am J Pathol. (2010) 177:1031–41. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100070

58. Welsh TJ, Green RH, Richardson D, Waller DA, O'Byrne KJ, Bradding P. Macrophage and mast-cell invasion of tumor cell islets confers a marked survival advantage in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2005) 23:8959–67. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.4910

59. Gibbs BF, Wierecky J, Welker P, Henz BM, Wolff HH, Grabbe J. Human skin mast cells rapidly release preformed and newly generated TNF-alpha and IL-8 following stimulation with anti-IgE and other secretagogues. Exp Dermatol. (2001) 10:312–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100503.x

60. Gordon JR, Galli SJ. Mast cells as a source of both preformed and immunologically inducible TNF-α/cachectin. Nature (1990) 346:274–6. doi: 10.1038/346274a0

61. Kulbe H, Chakravarty P, Leinster DA, Charles KA, Kwong J, Thompson RG, et al. A dynamic inflammatory cytokine network in the human ovarian cancer microenvironment. Cancer Res. (2012) 72:66–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2178

62. Kulbe H, Thompson R, Wilson JL, Robinson S, Hagemann T, Fatah R, et al. The inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha generates an autocrine tumor-promoting network in epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. (2007) 67:585–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2941

63. Liu F, Ai F, Tian L, Liu S, Zhao L, Wang X. Infliximab enhances the therapeutic effects of 5-fluorouracil resulting in tumor regression in colon cancer. Onco Targets Ther. (2016) 9:5999–6008. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S109342

64. Szomolay B, Eubank TD, Roberts RD, Marsh CB, Friedman A. Modeling the inhibition of breast cancer growth by GM-CSF. J Theor Biol. (2012) 303:141–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.03.024

65. Cheng YC, Valero V, Davis ML, Green MC, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Theriault RL, et al. Addition of GM-CSF to trastuzumab stabilises disease in trastuzumab-resistant HER2+ metastatic breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer (2010) 103:1331–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605918

66. Eubank TD, Marsh CB. GM-CSF Inhibits breast cancer growth and metastasis by invoking an anti-angiogenic program in tumor-educated macrophages. Cancer Res. (2009) 69:2133–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1405

67. Clifton GT, Gall V, Peoples GE, Mittendorf EA. Clinical development of the E75 vaccine in breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel) (2016) 11:116–21. doi: 10.1159/000446097

68. Teo PZ, Utz PJ, Mollick JA. Using the allergic immune system to target cancer: activity of IgE antibodies specific for human CD20 and MUC1. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2012) 61:2295–309. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1299-0

69. Almagro JC, Daniels-Wells TR, Perez-Tapia SM, Penichet ML. Progress and challenges in the design and clinical development of antibodies for cancer therapy. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:1751. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01751

70. Jensen-Jarolim E, Achatz G, Turner MC, Karagiannis S, Legrand F, Capron M, et al. AllergoOncology: the role of IgE-mediated allergy in cancer. Allergy (2008) 63:1255–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01768.x

71. Kinet JP. The high-affinity IgE receptor (Fc epsilon RI): from physiology to pathology. Annu Rev Immunol. (1999) 17:931–72; 931–72.

72. Leoh LS, Daniels-Wells TR, Penichet ML. IgE immunotherapy against cancer. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol (2015) 388:109–49. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-13725-4_6

73. Karagiannis SN, Josephs DH, Bax HJ, Spicer JF. Therapeutic IgE antibodies: harnessing a macrophage-mediated immune surveillance mechanism against cancer. Cancer Res. (2017) 77:2779–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0428

74. Gould HJ, Mackay GA, Karagiannis SN, O'Toole CM, Marsh PJ, Daniel BE, et al. Comparison of IgE and IgG antibody-dependent cytotoxicity in vitro and in a SCID mouse xenograft model of ovarian carcinoma. Eur J Immunol. (1999) 29:3527–37. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199911)29:11<3527::AID-IMMU3527>3.0.CO;2-5

75. de Vries VC, Wasiuk A, Bennett KA, Benson MJ, Elgueta R, Waldschmidt TJ, et al. Mast cell degranulation breaks peripheral tolerance. Am J Transplant. (2009) 9:2270–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02755.x

Keywords: mast cells, IgE, cancer, immunotherapy, breast cancer, HER2/neu

Citation: Plotkin JD, Elias MG, Fereydouni M, Daniels-Wells TR, Dellinger AL, Penichet ML and Kepley CL (2019) Human Mast Cells From Adipose Tissue Target and Induce Apoptosis of Breast Cancer Cells. Front. Immunol. 10:138. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00138

Received: 26 October 2018; Accepted: 16 January 2019;

Published: 18 February 2019.

Edited by:

Khashayarsha Khazaie, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine & Science, United StatesReviewed by:

Nahum Puebla-Osorio, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, United StatesCopyright © 2019 Plotkin, Elias, Fereydouni, Daniels-Wells, Dellinger, Penichet and Kepley. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christopher L. Kepley, Y2xrZXBsZXlAdW5jZy5lZHU=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.