94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Immunol., 22 January 2018

Sec. Cancer Immunity and Immunotherapy

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00014

This article is part of the Research TopicTargeting the Tumor Microenvironment for a More Effective and Efficient Cancer ImmunotherapyView all 15 articles

Recent advances in cancer treatment have emerged from new immunotherapies targeting T-cell inhibitory receptors, including cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen (CTLA)-4 and programmed cell death (PD)-1. In this context, anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies have demonstrated survival benefits in numerous cancers, including melanoma and non-small-cell lung carcinoma. PD-1-expressing CD8+ T lymphocytes appear to play a major role in the response to these immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI). Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) eliminate malignant cells through recognition by the T-cell receptor (TCR) of specific antigenic peptides presented on the surface of cancer cells by major histocompatibility complex class I/beta-2-microglobulin complexes, and through killing of target cells, mainly by releasing the content of secretory lysosomes containing perforin and granzyme B. T-cell adhesion molecules and, in particular, lymphocyte-function-associated antigen-1 and CD103 integrins, and their cognate ligands, respectively, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and E-cadherin, on target cells, are involved in strengthening the interaction between CTL and tumor cells. Tumor-specific CTL have been isolated from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) of patients with varied cancers. TCRβ-chain gene usage indicated that CTL identified in vitro selectively expanded in vivo at the tumor site compared to autologous PBL. Moreover, functional studies indicated that these CTL mediate human leukocyte antigen class I-restricted cytotoxic activity toward autologous tumor cells. Several of them recognize truly tumor-specific antigens encoded by mutated genes, also known as neoantigens, which likely play a key role in antitumor CD8 T-cell immunity. Accordingly, it has been shown that the presence of T lymphocytes directed toward tumor neoantigens is associated with patient response to immunotherapies, including ICI, adoptive cell transfer, and dendritic cell-based vaccines. These tumor-specific mutation-derived antigens open up new perspectives for development of effective second-generation therapeutic cancer vaccines.

CD8+ T lymphocytes play a central role in immunity to cancer through their capacity to kill malignant cells upon recognition by T-cell receptor (TCR) of specific antigenic peptides presented on the surface of target cells by human leukocyte antigen class I (HLA-I)/beta-2-microglobulin (β2m) complexes. TCR and associated signaling molecules thus become clustered at the center of the T cell/tumor cell contact area, resulting in formation of a so-called immune synapse (IS) (1) and initiation of a transduction cascade, leading to execution of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) effector functions. Major CTL activities are mediated either directly, through synaptic exocytosis of cytotoxic granules containing perforin and granzymes into the target, resulting in cancer cell destruction, or indirectly, through secretion of cytokines, including interferon (IFN)γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF). Adhesion/costimulatory molecules, mainly lymphocyte-function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1, CD11a/CD18 or αL/β2) and CD103 (αE/β7) integrins, on CTL play a critical role in TCR-mediated killing by interacting with their cognate ligands, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (or CD54) and E-cadherin, respectively, and directing exocytosis of lytic granules to the cancer cell surface at the IS (2, 3). NKG2D, a c-type lectin molecule expressed on activated lymphocytes (4, 5), also plays an important role in the induction of T-cell-mediated cytoxicity and in CTL-dependent rejection of cancer (6, 7). NKG2D ligands include major histocompatibility complex class I-related chain (MIC)A and MICB (8), and UL16-binding proteins 1, 2, and 3 (9). These ligands are upregulated upon cell stress, such as tumor transformation, and are expressed by most of the cancer cells (10) in particular those of epithelial origin (11).

Activation of naive CD8 T cells by antigen-presenting cells (APC) involves binding of TCR, that is associated with the CD3 complex, to specific peptide-major histocompatibility complex class I (pMHC-I) complexes and the interaction of the costimulatory molecules CD28 and CD2 with their respective ligands CD80/CD86 and LFA-3 (12). Costimulatory receptors such as TNF receptor family member 4 (TNFRSF4 best known as OX40 or CD134) and member 9 (TNFRSF9 best known as 4-1BB or CD137) also play an important role in T-cell priming and antitumor immune responses (13–17).

Evidence for antitumor CD8+ T-cell immunity was provided by isolation of tumor-specific CTL from peripheral blood or tumor tissue of patients with diverse cancers, such as melanoma and lung carcinoma (18–22). The existence of a tumor-specific CTL response was further strengthened by identification of tumor-associated antigens (TAA) and detection of TAA-specific CD8+ T cells in spontaneously regressing tumors (18). Moreover, a correlation between tumor progression control and the infiltration rate of CD8+ T lymphocytes in the tumor was established (23). Efficacy of the antitumor immune response is negatively influenced by a hostile tumor microenvironment. Establishment of an immunosuppressive state within the tumor is mediated by diverse immunosuppressive factors released by cancer cells themselves, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, and/or by recruiting regulatory immune cells with immunosuppressive functions, such as regulatory T (Treg) cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) (24). Indeed, a role for Treg cells in modulating tumor-specific effector T lymphocytes by producing immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, consuming IL-2 or expressing the inhibitory molecule cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen (CTLA)-4, has been reported (25, 26). MDSC are a heterogeneous group of myeloid progenitor cells and immature myeloid cells, including immature macrophages, granulocytes, and dendritic cells (DC), that impair T-lymphocyte functions by upregulating the expression of immune suppressive factors, such as arginase and inducible nitric oxide synthase, increasing the production of nitric oxide (NO) and reactive oxygen species, and inducing Treg cells (27). Moreover, it has been shown that predominant secretion of TNF by CD4+ T cells in MHC class II-expressing melanoma promotes a local immunosuppressive environment, impairing effector CD8+ T-cell functions (28).

While it is generally admitted that CD8+ T cells are directly involved in antitumor cytotoxic responses, the role of CD4+ T cells is more controversial. Involvement of CD4+ T cells in regulating antitumor immunity was associated with their help in priming of CD8+ T cells, through activation of APC and an increase in antigen presentation by major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) molecules via secretion of cytokines such as IFNγ (29, 30). More recently, it has been shown that CD4+ T-cell help optimized CTL in expression of cytotoxic effector molecules, downregulation of inhibitory receptors, and increased migration capacities (31). A role for the CD4+ T-cell subset in optimizing the antitumor immune response was supported by in vivo studies demonstrating that depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes promotes tumor progression, whereas their adoptive transfer was correlated with improved tumor regression (32). Moreover, it has been reported that CD4+ T cells recognize most tumor-specific immunogenic mutanomes, and that vaccination with such CD4+ immunogenic mutations confers antitumor activity and broadens CTL responses in mice (33). Frequent recognition of neoantigens by CD4+ T cells was also observed in human melanoma (34). Notably, CD4+ CTL able to kill specific tumor cells have been described in several cancer types, including non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and melanoma (35–39); for review, see Ref. (32). Elsewhere, TAA-specific CD4+ T-cell clones were shown to mediate HLA-II-restricted cytotoxic activity, making them attractive effectors in cancer immunotherapy (39, 40). While CD4+ CTL are able to lyse target cells via the granule exocytosis pathway (35, 36, 41, 42), they mainly use FasL- and APO2L/TRAIL-mediated pathways to kill their target cells (35, 43).

Our fundamental knowledge of the tumor-specific T-cell response came with the discovery of tumor antigens that differentiated malignant cells from their non-transformed counterparts and provided important input in the field of tumor immunology and cancer immunotherapy. The first human tumor antigen recognized by CTL was identified in melanoma and was designated melanoma-associated antigen (MAGE)-1 (44). Subsequently, several other antigens of the MAGE family were characterized, most of which were identified through generation of tumor cell lines and isolation of reactive autologous CTL clones. Based on their expression profile, tumor antigens were initially classified into two categories: TAA and tumor-specific antigens (TSA). TAA are relatively restricted to tumor cells, and, to a limited degree, to normal tissues, whereas TSA are expressed only in tumor cells, arising from mutations that result in novel abnormal protein production.

At present, numerous TAA have been identified in a large variety of human cancer types. They are heterogeneous in nature and were classified into at least four groups according to their expression repertoire and the source of the antigen: antigens encoded by cancer-germline genes, differentiation antigens, overexpressed antigens, and viral antigens (Table 1). Antigens encoded by cancer-germline genes are expressed in tumor cells and in cells from adult reproductive tissues, including placenta and testicular cells, and are thus designated cancer testis antigens. Differentiation antigens are expressed only in tumor cells and in the normal tissue of origin, while overexpressed antigens are derived from proteins that are overexpressed in tumors, but are expressed at much lower levels in normal tissues. Viral antigens derive from viral infection and are associated with several human cancers, including cervical carcinoma, hepatocarcinoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and adult T-cell leukemia (45, 46).

The first mutant TSA, also termed neoantigens, were identified by the genetic method (46) via isolation of reactive CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell clones (Table 2). Recent accessibility to next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology and improvement in in silico epitope prediction have contributed to identification of patient-specific tumor antigens generated by somatic mutations in individual tumors (Table 3). Notably, most mutations identified in tumor-expressed genes do not generate neoantigens recognized by cognate T lymphocytes. Moreover, a large fraction of these mutations are not shared between patients and may thus be considered patient specific (47). These neoantigens have opened up new perspectives in cancer immunotherapy. They were shown to be involved in the success of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) (48–50), adoptive cell transfer (ACT) immunotherapy (51, 52), and even virally induced epithelial cancer (53) and DC-based immunotherapy (54, 55); thus, they might be of use as predictive biomarkers of the response to immunotherapy.

Most antigenic peptides recognized by CD8+ T cells originate from degradation of intracellular proteins by proteasomes and translocation to the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP)1/TAP2 heterodimeric complex. Once in the ER, peptides larger than 11 residues are further cleaved by ER amino-peptidase (ERAP)1 and ERAP2 before being loaded onto MHC-I molecules and presented on the surface of target cells for CD8 T-cell recognition [for review, see Ref. (87, 88)].

Defects in the antigen-processing machinery and, in particular, in TAP subunits, have been described as a major mechanism used by several tumors to escape from CD8 T-cell immunity (89). In this context, alternative peptide degradation pathways permitting CD8 T cells to overcome this tumor evasion mechanism have been identified. Indeed, proteasome/TAP-independent CTL epitopes, generated either by the cytosolic metallopeptidase insulin-degrading enzyme or cytosolic endopeptidases nardilysin and thimet oligopeptidase, have been described (90, 91). Moreover, TAP-independent processing of antigenic peptides can be achieved by the so-called secretory pathway in which the proteolytic enzyme furine releases C-terminal peptides (92). Interestingly, peptide epitopes that emerge at the surface of cancer cells with impaired TAP function derived from self-antigens and act as immunogenic neoantigens, as they are not presented by normal cells (93). Our group identified a signal peptide-derived CD8 T-cell epitope processed independently of proteasomes/TAP, by a novel pathway involving signal peptidase and the signal peptide peptidase (94, 95). These signal sequence-derived peptides represent attractive T-cell targets that permit CTL to destroy TAP-impaired tumors and therefore correspond to promising candidates for cancer immunotherapy.

The TCR–CD3 complex, expressed on the T-cell surface, allows recognition of antigenic peptides bound to MHC molecules on target cells and APC, and transduction of the signal into the cytosol to initiate signaling events leading to T-cell activation (96). The TCRα- and β-chains are products of V(D)J recombination, a somatic rearrangement of the germline TCR loci occurring in T cells (97). This process leads to generation of a diverse TCR repertoire [>1015 distinct αβ-receptors or clonotypes (98)] that enables T-cell recognition of numerous foreign or mutant antigens. The TCRα- and β-chains possess three hypervariable regions, referred to as complementarity-determining regions (CDR) 1, 2, and 3. CDR3 is highly polymorphic and is directly responsible for recognition of antigenic peptides. Immunoscope/spectratype technology was first used to probe the T-cell repertoire by analyzing the diversity of TCRVβ (99, 100) and, more recently, TCRVα (101, 102) chains without isolating peptide-reactive T cells and cloning TCR genes. It is based on the use of V and J gene-segment-specific primers for reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction amplification of CDR3 of a bulk T-cell population from diverse biological materials such as blood and tumor tissues (103). Analyzing CDR3 polymorphisms and sequence length diversity served to follow up T-cell clonality in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) to investigate T-cell functions and the pattern of TCR utilization. It highlighted restriction of the CDR3 length of TCRβ- and TCRα-chains in T cells infiltrating solid tumors and hematological malignancies, including melanoma, renal cell carcinoma (RCC), neuroblastoma, NSCLC, and Sezary syndrome (19, 101, 104–109). TCRβ-chain gene usage also showed that antigen-specific T-cell clones with high functional avidity/tumor reactivity expanded only at the tumor site, but not in peripheral blood (108). Identification of TAA has led to improvement in procedures for detecting and monitoring specific antitumor T-cell responses. In this regard, combining a quantitative immunoscope approach with MHC–peptide multimer-based T-cell sorting led to more sensitive ex vivo follow-up, by quantitation of human CD8+ T-cell responses and monitoring of T-cell subsets throughout immunotherapy clinical trials (110).

Tremendous progress in characterizing the size and dynamics of the T-cell repertoire has emerged from recent advances in DNA and RNA sequencing (RNAseq) technologies (111, 112). High-throughput TCR sequencing (TCR-seq) involves NGS for generating DNA sequences covering TCR CDR3 and permits quantification of T-cell diversity at very high resolution (113). Another method for profiling the TCR repertoire relies on a TCR-specific short read assembly strategy based on 5′ amplification of cDNA ends (RACE), so as to obtain TCRβ CDR3 transcript sequences and massively parallel Illumina sequencing of TCRβ CDR3 amplification products (114). This strategy avoids potential bias associated with the use of multiple primer sets required to amplify CDR3 regions from all TCRBV sequences and takes advantage of the conserved sequences of TCRBC1 and TCRBC2 genes (115, 116). High-throughput DNA-based strategy for identifying antigen-specific TCR sequences was also developed by the capture and sequencing of genomic DNA fragments encoding TCR genes (117). More recently, an optimized approach to characterizing tissue-resident T-cell (TRM) populations emerged from extraction of TCR CDR3 sequence information directly from RNAseq data sets of thousands of solid tumors and control tissues (118). This method circumvents the need for PCR amplification and provides TCR information in the context of global gene expression profiles.

Sequence-based immunoprofiling is a useful tool for monitoring the dynamics of the T-cell repertoire under physiological and pathological conditions, and in response to therapeutic interventions. In this respect, characterization of the TCR repertoire in TIL permits isolation of tumor-specific T-cell clones for use in cancer immunotherapy. TCR-seq can also be used to evaluate T-cell diversity and identify tumor-reactive T-cell clonotypes, along with potentially immunogenic neoantigen-reactive T cells (119). For instance, deep cDNA sequencing of TCR-α and β-chains enabled quantitative monitoring of the T-cell repertoire in lung cancer patients treated with cancer peptide vaccines (120). Another interesting parameter for follow-up by deep TCR-seq is the heterogeneity of T-cell density and clonality across tumor regions. Indeed, it has been shown that high intratumor heterogeneity of TCR is positively correlated with that of predicted neoantigens and has been associated with increased risk of disease progression (121). In contrast, maintenance of high-frequency TCR clonotypes alongside CTLA-4 blockade therapy was associated with improved overall survival in prostate cancer and melanoma (122). Moreover, high TCR clonality was associated with an increased response by melanoma patients to the programmed cell death (PD)-1 blockade, suggesting that TCR repertoire analysis could be used as a predictive marker in cancer immunotherapy (123). Indeed, elevated TCR clonality and significant T-cell clone expansion were observed in melanoma patients responding to anti-PD1 treatment (124). Overall, T-cell clonality and TCR repertoire diversity appear to be biomarkers of antitumor adaptive immunity and might also be predictive markers of responses to cancer immunotherapy.

An understanding of regulation of the molecular interaction between T cells and tumor cells, together with refined T-cell engineering technologies and the discovery of TSA, gave rise to novel cancer immunotherapies with unprecedented clinical efficacy. These therapies are aimed at (re)activating and expanding tumor-specific CTL, with the goal of destroying primary cancer cells and metastases. The most effective current cancer immunotherapies include ICI, such as anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4, ACT of ex vivo-expanded tumor-reactive T cells, either native (CTL clones or TIL) or engineered to express particular TCR or chimeric antigen receptors (CAR), and TSA-based cancer vaccines (peptide- or RNA-based) (84, 125–132). Moreover, increasing evidence of a link between CD8 and CD4 T-cell recognition of mutant neoepitopes and clinical responses to cancer immunotherapy strategies has been reported (34, 48–53, 55); for review, see Ref. (47).

The possibility of expanding subsets of mature T cells in vitro led to development of ACT immunotherapy. The aim is to transfer a T-cell population enriched in potentially highly tumor-reactive effector cells (130, 131, 133, 134). In this context, re-infusion of ex vivo-expanded TIL displaying increased specificity toward cancer cells was developed as a means of strengthening patient spontaneous T-cell responses and overcoming tolerance to the tumor. Steven Rosenberg’s team has been one of the pioneers in the development of ACT, mainly using selected tumor-reactive T cells and TIL. Thus, clonal repopulation of T cells directed against overexpressed self-derived differentiation antigens, in combination with chemotherapy and high doses of IL-2, led to tumor regression in patients with metastatic melanoma (135, 136). Similarly, treatment of patients with uveal melanoma by adoptive transfer of autologous TIL, administered together with IL-2, resulted in objective tumor regression (137). Clinical responses were associated with the presence of tumor-resident CD8+ T lymphocytes that target tumor-specific mutant neoantigens and express the PD-1 checkpoint receptor (51, 52, 83, 138, 139). Moreover, neoantigen-reactive TCR have been identified from the most frequent clonotypes among TIL, opening up new avenues for developing a personalized TCR-gene therapy approach that targets individual sets of antigens presented by tumor cells without the need for determining their identity (140). Accordingly, neoantigen-reactive TCR have been identified, with the aim of treating patients with autologous T cells genetically modified to express such TCR (141). Nevertheless, analyses of neoantigen-specific T-cell responses in melanoma patients treated by ACT demonstrated that the T-cell-recognized neoantigens can be selectively lost over time emphasizing the importance of targeting broad TCR recognized neoantigens to avoid tumor resistance (142).

While ACT of tumor-specific T cells holds promise for melanoma treatment, significant challenges remain in clinical translation to other solid tumors. This can be explained by the observation that some tumors, referred to as “immune-desert tumors” or “cold tumors,” are rarely infiltrated by T cells, and TIL often display an exhausted state acquired in the tumor microenvironment. Indeed, TIL are characterized by high expression levels of one or several inhibitory receptors such as PD-1, CTLA-4, Tim-3, LAG-3, and TIGIT, and often display altered production of cytokines leading to weak antitumor reactivity (143, 144); for review, see Ref. (145). Moreover, the limited life span of TIL and difficulties linked to their production, including isolation from fresh patient tumor specimens and selection based on tumor-specificity, constrain their clinical routine use.

To overcome limitations of TIL-based ACT, and due to the availability of TAA-specific TCR or antibodies, genetically engineered T cells have been developed with either tumor-specific TCR or CAR (146–149). Therefore, desired specificity was achieved by genetically modifying T cells to express a TAA-specific TCR (150–153). Candidates are selected either from the native TCR repertoire or after mutagenesis of their antigen recognition domain, the CDR3 domain, to increase the affinity of T cells (154). Thus, T cells engineered to express TAA-specific TCR (recognizing Melan-A/MART1-, gp100-, NY-ESO-, or p53-derived peptides) resulted in objective regression of metastatic melanoma lesions in some patients (153, 155, 156). As an alternative, engineered T-cell strategy utilizes CAR comprising the antigen-binding domain of an antibody, fused with one or more immunostimulatory domains, to activate T cells once the recognition domain has bound to a target cell. Because such T cells are able to recognize tumor antigen-expressing cells in a MHC-independent manner, a single CAR can be used on all patients whose tumor expresses the target antigen (i.e., CD19, CD20). The therapeutic potential of CAR-expressing T cells, especially in patients with hematological malignancies such as B-cell lymphoma expressing CD19 or CD20, has been demonstrated in several clinical trials (157–163). This holds promise for further use in hematological tumors and for treatment of solid tumors unresponsive to other immunotherapies.

Targeting immune checkpoints with blocking monoclonal antibodies (mAb) such as anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 has provided clinical benefits for patients with advanced metastatic melanoma, NSCLC, RCC, and several other cancers (164, 165). While the CTLA-4 blockade reduces the activation threshold required for T-cell priming (166), the PD1/PD-L1 blockade in certain T-cell subpopulations (167) at least partly reverses immune alterations such as exhaustion (168). This allows synergy for combined treatments (169) and opens up new perspectives for combining these checkpoint blockers (i.e., anti-CTLA-4, -PD-1, or -PD-L1) with mAb toward additional inhibitory molecules, such as BTLA, TIM-3, or LAG-3. In this regard, synergistic antitumor effects were obtained in several preclinical models (170–172).

Accumulating evidence indicates that preexisting antitumor CD8+ T cells predict the efficacy of ICI therapy (124, 173). Moreover, effective CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade immunotherapy appears to be associated with the presence of T cells directed toward mutant cancer neoepitopes (48–50), and with the likelihood of MHC presentation of these neoantigens and subsequent recognition by specific T cells (174). Mutant neoantigens are highly immunogenic; they are not expressed by normal tissues and thus bypass thymic tolerance (175). Unfortunately, clinical trials demonstrated that only a fraction of cancer patients respond to such immunotherapy. Resistance to anti-PD-1 of tumors with a high mutational load was associated with defects in pathways involved in IFNγ-receptor signaling and antigen presentation by MHC-I molecules, concomitant with a truncating mutation in the gene encoding β2m (176, 177). Moreover, patients identified as non-responders to anti-CTLA-4 mAb had tumors with genomic defects in IFN-γ pathway genes (178). These findings demonstrate the importance of the IFN-γ signaling pathway and CD8 T-cell recognition of mutant neoantigens in response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy.

The discovery of TAA has led to development of therapeutic cancer vaccines, based on either synthetic peptides, “naked” DNA, DC, or recombinant viruses, that attempt to strengthen the antitumor immune response, and particularly tumor antigen-specific CTL response (179, 180). Peptide vaccines have many advantages, including inexpensive, convenient acquisition of clinical-grade peptides, easy administration, higher specificity, and potency due to their higher compatibility with targeted proteins, the ability to penetrate the cell membrane and improved safety with few side effects (181, 182). Mechanisms underlying priming of anticancer immune responses by peptide-based vaccines, and hence their efficacy, is dependent, at least in part, on the size of the peptides. While short peptides (8–11 aa) bind directly to HLA-I molecules and mount MHC-I-restricted antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell immunity (183–185), long synthetic peptides (25–50 aa) must be taken up, processed, and presented by APC to elicit a T-cell response. Vaccination with long peptides usually results in broader immunity than with short peptides, along with induction of both CD8+ cytotoxic and CD4+ helper T cells when conjugated with efficient adjuvants (186, 187). Indeed, CD4+ T-cell help is required for generation of potent CTL and long-lived memory CD8+ T cells (186).

First-generation cancer vaccines based on non-mutant TAA, also termed shared antigens because they are expressed by many patients’ tumors, such as MART-1, gp100, tyrosinase, TRP-2, NY-ESO-1, MAGE-A3, and Her2/neu or telomerase proteins, were shown to be immunogenic and capable of inducing clinical responses in only a minority of patients with late-stage cancer (180, 188, 189). However, results showing that CD4+ T cells directed toward NY-ESO-1 cancer-germline TAA and lymphocytes genetically engineered with a NY-ESO-1-reactive TCR display antitumor activity (40, 190) support the notion that T-cell responses to a subset of non-mutant antigens contribute to the effects of current cancer immunotherapies. The limited success of these active immunotherapy approaches might be due to the inability of effector T cells to overcome tolerance to self-antigens, expression of T-cell inhibitory receptors such as CTLA-4 and PD-1, and suboptimal activation of tumor-specific T cells in an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (191).

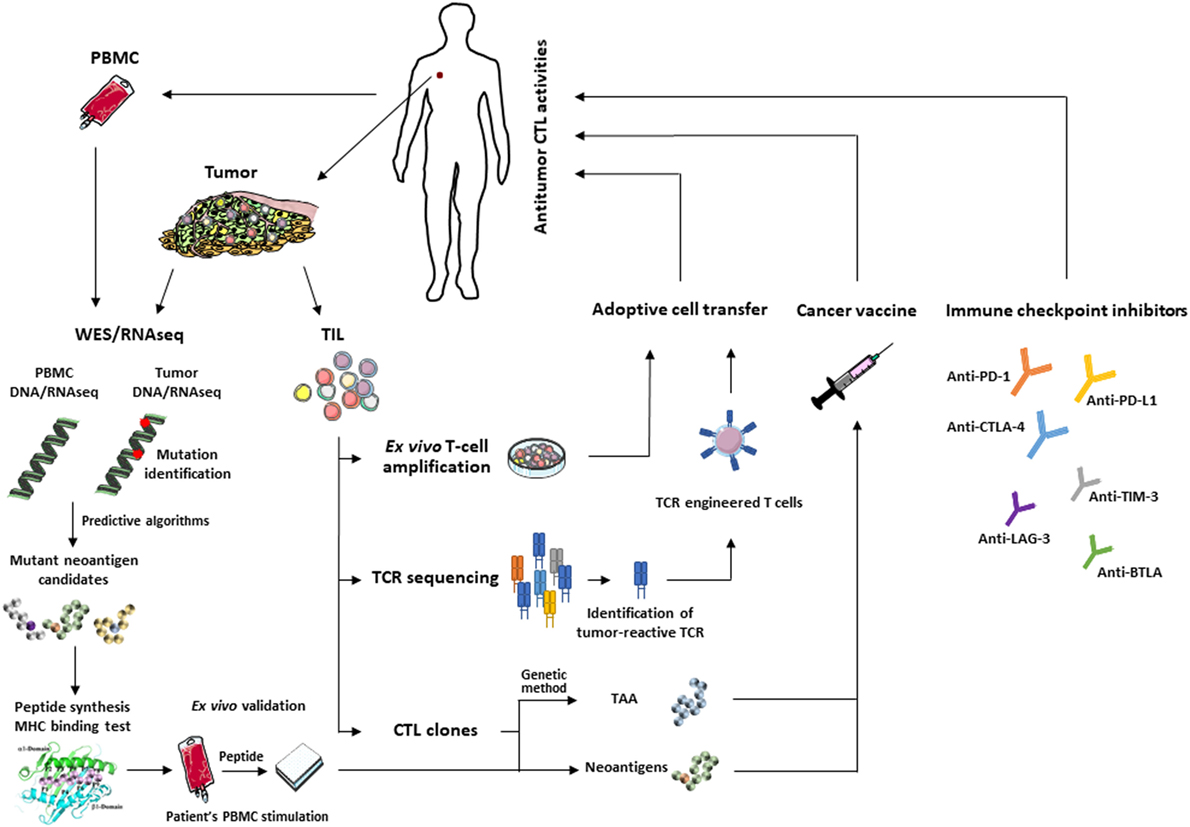

The current challenge in developing more efficient second-generation cancer vaccines is based on mutant epitopes that derive from tumor neoantigens (192, 193). Non-mutant tumor neoepitopes that emerge on the target cell surface upon alteration of TAP expression, such as the self-epitope derived from the human ppCT preprohormone (94, 95), are interesting targets for peptide-based vaccination against immune-escaped tumors expressing low levels of pMHC-I complexes (194, 195). Recent technological advances in identifying mutation-derived tumor antigens have enabled development of patient-specific therapeutic vaccines, including peptides, proteins, DC, tumor cells, and viral vectors, that target individual cancer mutations (196). Over the past few years, examples of TSA-based personalized cancer immunotherapies have begun to emerge. For example, a durable clinical response to cancer vaccines with autologous melanoma-pulsed DC was obtained and correlated with the presence of effector memory T cells responding to mutant antigens (54). Moreover, DC-based vaccination directed at melanoma-neoepitope candidates resulted in an increase in clonal diversity of antitumor T-cell immunity and promoted a diverse neoantigen-specific TCR repertoire (55). Immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccines, based either on RNA or synthesized long peptides, have recently been developed for patients with melanoma. In this regard, personalized RNA-based mutanome vaccines, alone or in combination with anti-PD-1, induced effective T-cell responses against multiple vaccine neoepitopes and resulted in sustained progression-free survival (84). In another clinical trial, long peptide cancer vaccines that target predicted personal tumor neoantigens, administered alone or in combination with anti-PD-1, resulted in clinical benefits and induced polyfunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, with expansion of the repertoire of neoantigen-specific T cells (132). Thus, a combination of neoepitope-based vaccines and ICI is promising for overcoming the anergic state of vaccine-induced T cells. These strategies open up new avenues for further development of personalized active immunotherapy, either alone or in combination with other therapies, for patients with different types of cancer (Figure 1). Personalized cancer immunotherapies offer promise of low toxicity and high specificity, and the opportunity to treat human malignancies resistant to current therapies.

Figure 1. Main approaches for T-cell-based cancer immunotherapy: identification of immunogenic tumor antigens using WES/RNAseq and predictive programs (left) or CTL and genetic approach for the development of effective therapeutic cancer vaccines. Adoptive transfer of selected tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) or autologous T cells engineered to express tumor-reactive T-cell receptor (TCR) (middle). These approaches can be combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors (right) to reverse T-cell exhaustion and optimize antitumor T-cell response.

The success of cancer immunotherapy relies on the induction of immune effector mechanisms associated with generation of high-avidity tumor-specific CTL. To further improve their antitumor effectiveness, and for more robust long-term disease control, a deeper understanding of host-tumor interactions and tumor immune escape strategies is required. Overcoming immune tolerance/suppression pathways within the tumor microenvironment, which may hinder the potency of immunotherapeutic approaches, is a major challenge in the field of tumor immunology and immunotherapy. In this context, optimizing the therapeutic potential of the immune system relies on a combination of different approaches, mainly cancer vaccines with ICI and/or ACT, which synergistically enhance antitumor T-cell responses. Selection of the right adjuvant or neoadjuvant, such as TLR agonists, is necessary to improve the immunogenicity of peptide-based vaccines, by targeting antigens to competent APC (and, in particular, DC, capable of cross-presentation and delivering of stimuli to activate both specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells). Moreover, alternative routes of peptide administration for improved target delivery would help to induce strong long-lasting antitumor T-cell responses and thus improve clinical outcome. Therapeutic cancer vaccines combining both TAP-dependent and TAP-independent epitopes might also boost tumor-specific CD8 T-cell immunity, prevent immune escape mechanisms developed by malignant cells, and thereby potentiate current cancer immunotherapies. Remarkably, targeting of non-self tumor-specific neoantigens, generated by somatic mutations, has gained increasing interest over the past few years. Rising accessibility to NGS technologies, improved in silico prediction of truly immunogenic mutant peptides and easy peptide manufacturing are promising approaches to identifying patient-specific neoepitopes and evaluating their potential use in both prognosis and treatment. The utility of highly immunogenic neoantigens for personalizing therapeutic cancer vaccines will open up new perspectives for the refinement of current cancer immunotherapies.

FMC, AD, and SC: design and writing. YV: writing.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was supported by grants from Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC) and the Institut National du Cancer (INCa). SC is a recipient of a fellowship from INCa.

ACT, adoptive cell transfer; CDR, complementarity-determining region; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; CTLA, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen; PD, programmed cell death; DC, dendritic cell; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitors; IFN, interferon; LFA-1, lymphocyte-function-associated antigen-1; mAb, monoclonal antibody, NSCLC, non-small-cell lung carcinoma; MHC-I/β2m, major histocompatibility complex class I/beta-2-microglobulin; TAA, tumor-associated antigen; TCR, T-cell receptor; TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte; TSA, tumor-specific antigen.

1. Bossi G, Trambas C, Booth S, Clark R, Stinchcombe J, Griffiths GM. The secretory synapse: the secrets of a serial killer. Immunol Rev (2002) 189:152–60. doi:10.1034/j.1600-065X.2002.18913.x

2. Anikeeva N, Somersalo K, Sims TN, Thomas VK, Dustin ML, Sykulev Y. Distinct role of lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 in mediating effective cytolytic activity by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2005) 102(18):6437–42. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502467102

3. Le Floc’h A, Jalil A, Vergnon I, Le Maux Chansac B, Lazar V, Bismuth G, et al. Alpha E beta 7 integrin interaction with E-cadherin promotes antitumor CTL activity by triggering lytic granule polarization and exocytosis. J Exp Med (2007) 204(3):559–70. doi:10.1084/jem.20061524

4. Eichler W, Ruschpler P, Wobus M, Drossler K. Differentially induced expression of C-type lectins in activated lymphocytes. J Cell Biochem Suppl (2001) Suppl 36:201–8. doi:10.1002/jcb.1107

5. Eagle RA, Trowsdale J. Promiscuity and the single receptor: NKG2D. Nat Rev Immunol (2007) 7(9):737–44. doi:10.1038/nri2144

6. Maccalli C, Nonaka D, Piris A, Pende D, Rivoltini L, Castelli C, et al. NKG2D-mediated antitumor activity by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and antigen-specific T-cell clones isolated from melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res (2007) 13(24):7459–68. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1166

7. Wang E, Selleri S, Marincola FM. The requirements for CTL-mediated rejection of cancer in humans: NKG2D and its role in the immune responsiveness of melanoma. Clin Cancer Res (2007) 13(24):7228–31. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2150

8. Cerwenka A, Lanier LL. Ligands for natural killer cell receptors: redundancy or specificity. Immunol Rev (2001) 181:158–69. doi:10.1034/j.1600-065X.2001.1810113.x

9. Cosman D, Mullberg J, Sutherland CL, Chin W, Armitage R, Fanslow W, et al. ULBPs, novel MHC class I-related molecules, bind to CMV glycoprotein UL16 and stimulate NK cytotoxicity through the NKG2D receptor. Immunity (2001) 14(2):123–33. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00095-4

10. Moretta A, Bottino C, Vitale M, Pende D, Cantoni C, Mingari MC, et al. Activating receptors and coreceptors involved in human natural killer cell-mediated cytolysis. Annu Rev Immunol (2001) 19:197–223. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.197

11. Groh V, Rhinehart R, Secrist H, Bauer S, Grabstein KH, Spies T. Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived gamma delta T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1999) 96(12):6879–84. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.12.6879

12. Davis SJ, Ikemizu S, Evans EJ, Fugger L, Bakker TR, van der Merwe PA. The nature of molecular recognition by T cells. Nat Immunol (2003) 4(3):217–24. doi:10.1038/ni0303-217

13. Melero I, Shuford WW, Newby SA, Aruffo A, Ledbetter JA, Hellstrom KE, et al. Monoclonal antibodies against the 4-1BB T-cell activation molecule eradicate established tumors. Nat Med (1997) 3(6):682–5. doi:10.1038/nm0697-682

14. Sugamura K, Ishii N, Weinberg AD. Therapeutic targeting of the effector T-cell co-stimulatory molecule OX40. Nat Rev Immunol (2004) 4(6):420–31. doi:10.1038/nri1371

15. Croft M. The role of TNF superfamily members in T-cell function and diseases. Nat Rev Immunol (2009) 9(4):271–85. doi:10.1038/nri2526

16. Ye Q, Song DG, Powell DJ Jr. Finding a needle in a haystack: activation-induced CD137 expression accurately identifies naturally occurring tumor-reactive T cells in cancer patients. Oncoimmunology (2013) 2(12):e27184. doi:10.4161/onci.27184

17. Adler AJ, Vella AT. Betting on improved cancer immunotherapy by doubling down on CD134 and CD137 co-stimulation. Oncoimmunology (2013) 2(1):e22837. doi:10.4161/onci.22837

18. Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde B. Tumor antigens recognized by T cells. Immunol Today (1997) 18(6):267–8. doi:10.1016/S0167-5699(97)80020-5

19. Echchakir H, Vergnon I, Dorothee G, Grunenwald D, Chouaib S, Mami-Chouaib F. Evidence for in situ expansion of diverse antitumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte clones in a human large cell carcinoma of the lung. Int Immunol (2000) 12(4):537–46. doi:10.1093/intimm/12.4.537

20. Karanikas V, Colau D, Baurain JF, Chiari R, Thonnard J, Gutierrez-Roelens I, et al. High frequency of cytolytic T lymphocytes directed against a tumor-specific mutated antigen detectable with HLA tetramers in the blood of a lung carcinoma patient with long survival. Cancer Res (2001) 61(9):3718–24.

21. Slingluff CL Jr, Cox AL, Stover JM Jr, Moore MM, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response to autologous human squamous cell cancer of the lung: epitope reconstitution with peptides extracted from HLA-Aw68. Cancer Res (1994) 54(10):2731–7.

22. Weynants P, Thonnard J, Marchand M, Delos M, Boon T, Coulie PG. Derivation of tumor-specific cytolytic T-cell clones from two lung cancer patients with long survival. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (1999) 159(1):55–62. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9805073

23. Pages F, Berger A, Camus M, Sanchez-Cabo F, Costes A, Molidor R, et al. Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med (2005) 353(25):2654–66. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051424

24. Gajewski TF, Meng Y, Harlin H. Immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunother (2006) 29(3):233–40. doi:10.1097/01.cji.0000199193.29048.56

25. Piccirillo CA, Shevach EM. Cutting edge: control of CD8+ T cell activation by CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory cells. J Immunol (2001) 167(3):1137–40. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1137

26. Wing K, Yamaguchi T, Sakaguchi S. Cell-autonomous and -non-autonomous roles of CTLA-4 in immune regulation. Trends Immunol (2011) 32(9):428–33. doi:10.1016/j.it.2011.06.002

27. Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol (2009) 9(3):162–74. doi:10.1038/nri2506

28. Donia M, Andersen R, Kjeldsen JW, Fagone P, Munir S, Nicoletti F, et al. Aberrant expression of MHC class II in melanoma attracts inflammatory tumor-specific CD4+ T-cells, which dampen CD8+ T-cell antitumor reactivity. Cancer Res (2015) 75(18):3747–59. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2956

29. Pardoll DM, Topalian SL. The role of CD4+ T cell responses in antitumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol (1998) 10(5):588–94. doi:10.1016/S0952-7915(98)80228-8

30. Kalams SA, Walker BD. The critical need for CD4 help in maintaining effective cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med (1998) 188(12):2199–204. doi:10.1084/jem.188.12.2199

31. Ahrends T, Spanjaard A, Pilzecker B, Babala N, Bovens A, Xiao Y, et al. CD4+ T cell help confers a cytotoxic T cell effector program including coinhibitory receptor downregulation and increased tissue invasiveness. Immunity (2017) 47(5):848–61.e5. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2017.10.009

32. Martorelli D, Muraro E, Merlo A, Turrini R, Rosato A, Dolcetti R. Role of CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the control of viral diseases and cancer. Int Rev Immunol (2010) 29(4):371–402. doi:10.3109/08830185.2010.489658

33. Kreiter S, Vormehr M, van de Roemer N, Diken M, Lower M, Diekmann J, et al. Mutant MHC class II epitopes drive therapeutic immune responses to cancer. Nature (2015) 520(7549):692–6. doi:10.1038/nature14426

34. Linnemann C, van Buuren MM, Bies L, Verdegaal EM, Schotte R, Calis JJ, et al. High-throughput epitope discovery reveals frequent recognition of neo-antigens by CD4+ T cells in human melanoma. Nat Med (2015) 21(1):81–5. doi:10.1038/nm.3773

35. Dorothee G, Vergnon I, Menez J, Echchakir H, Grunenwald D, Kubin M, et al. Tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T lymphocytes express APO2 ligand (APO2L)/TRAIL upon specific stimulation with autologous lung carcinoma cells: role of IFN-alpha on APO2L/TRAIL expression and -mediated cytotoxicity. J Immunol (2002) 169(2):809–17. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.809

36. Echchakir H, Bagot M, Dorothee G, Martinvalet D, Le Gouvello S, Boumsell L, et al. Cutaneous T cell lymphoma reactive CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte clones display a Th1 cytokine profile and use a fas-independent pathway for specific tumor cell lysis. J Invest Dermatol (2000) 115(1):74–80. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00995.x

37. Darrow TL, Abdel-Wahab Z, Quinn-Allen MA, Seigler HF. Recognition and lysis of human melanoma by a CD3+, CD4+, CD8- T-cell clone restricted by HLA-A2. Cell Immunol (1996) 172(1):52–9. doi:10.1006/cimm.1996.0214

38. Zennadi R, Abdel-Wahab Z, Seigler HF, Darrow TL. Generation of melanoma-specific, cytotoxic CD4(+) T helper 2 cells: requirement of both HLA-DR15 and Fas antigens on melanomas for their lysis by Th2 cells. Cell Immunol (2001) 210(2):96–105. doi:10.1006/cimm.2001.1809

39. Huarte E, Karbach J, Gnjatic S, Bender A, Jager D, Arand M, et al. HLA-DP4 expression and immunity to NY-ESO-1: correlation and characterization of cytotoxic CD4+ CD25- CD8- T cell clones. Cancer Immun (2004) 4:15.

40. Hunder NN, Wallen H, Cao J, Hendricks DW, Reilly JZ, Rodmyre R, et al. Treatment of metastatic melanoma with autologous CD4+ T cells against NY-ESO-1. N Engl J Med (2008) 358(25):2698–703. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0800251

41. Yasukawa M, Ohminami H, Yakushijin Y, Arai J, Hasegawa A, Ishida Y, et al. Fas-independent cytotoxicity mediated by human CD4+ CTL directed against herpes simplex virus-infected cells. J Immunol (1999) 162(10):6100–6.

42. Appay V, Zaunders JJ, Papagno L, Sutton J, Jaramillo A, Waters A, et al. Characterization of CD4(+) CTLs ex vivo. J Immunol (2002) 168(11):5954–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5954

43. Nagata S, Golstein P. The Fas death factor. Science (1995) 267(5203):1449–56. doi:10.1126/science.7533326

44. Van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, Lurquin C, De Plaen E, Van den Eynde B, et al. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science (1991) 254(5038):1643–7. doi:10.1126/science.1840703

45. Novellino L, Castelli C, Parmiani G. A listing of human tumor antigens recognized by T cells: March 2004 update. Cancer Immunol Immunother (2005) 54(3):187–207. doi:10.1007/s00262-004-0560-6

46. Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P, Boon T. Tumour antigens recognized by T lymphocytes: at the core of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer (2014) 14(2):135–46. doi:10.1038/nrc3670

47. Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science (2015) 348(6230):69–74. doi:10.1126/science.aaa4971

48. Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, Yuan J, Zaretsky JM, Desrichard A, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med (2014) 371(23):2189–99. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1406498

49. Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science (2015) 348(6230):124–8. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1348

50. McGranahan N, Furness AJ, Rosenthal R, Ramskov S, Lyngaa R, Saini SK, et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science (2016) 351(6280):1463–9. doi:10.1126/science.aaf1490

51. Tran E, Turcotte S, Gros A, Robbins PF, Lu YC, Dudley ME, et al. Cancer immunotherapy based on mutation-specific CD4+ T cells in a patient with epithelial cancer. Science (2014) 344(6184):641–5. doi:10.1126/science.1251102

52. Lu YC, Yao X, Crystal JS, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Gross C, et al. Efficient identification of mutated cancer antigens recognized by T cells associated with durable tumor regressions. Clin Cancer Res (2014) 20(13):3401–10. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0433

53. Stevanovic S, Pasetto A, Helman SR, Gartner JJ, Prickett TD, Howie B, et al. Landscape of immunogenic tumor antigens in successful immunotherapy of virally induced epithelial cancer. Science (2017) 356(6334):200–5. doi:10.1126/science.aak9510

54. Pritchard AL, Burel JG, Neller MA, Hayward NK, Lopez JA, Fatho M, et al. Exome sequencing to predict neoantigens in melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res (2015) 3(9):992–8. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0088

55. Carreno BM, Magrini V, Becker-Hapak M, Kaabinejadian S, Hundal J, Petti AA, et al. Cancer immunotherapy. A dendritic cell vaccine increases the breadth and diversity of melanoma neoantigen-specific T cells. Science (2015) 348(6236):803–8. doi:10.1126/science.aaa3828

56. Gueguen M, Patard JJ, Gaugler B, Brasseur F, Renauld JC, Van Cangh PJ, et al. An antigen recognized by autologous CTLs on a human bladder carcinoma. J Immunol (1998) 160(12):6188–94.

57. Mandruzzato S, Brasseur F, Andry G, Boon T, van der Bruggen P. A CASP-8 mutation recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human head and neck carcinoma. J Exp Med (1997) 186(5):785–93. doi:10.1084/jem.186.5.785

58. Robbins PF, El-Gamil M, Li YF, Kawakami Y, Loftus D, Appella E, et al. A mutated beta-catenin gene encodes a melanoma-specific antigen recognized by tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. J Exp Med (1996) 183(3):1185–92. doi:10.1084/jem.183.3.1185

59. Wolfel T, Hauer M, Schneider J, Serrano M, Wolfel C, Klehmann-Hieb E, et al. A p16INK4a-insensitive CDK4 mutant targeted by cytolytic T lymphocytes in a human melanoma. Science (1995) 269(5228):1281–4. doi:10.1126/science.7652577

60. Huang J, El-Gamil M, Dudley ME, Li YF, Rosenberg SA, Robbins PF. T cells associated with tumor regression recognize frameshifted products of the CDKN2A tumor suppressor gene locus and a mutated HLA class I gene product. J Immunol (2004) 172(10):6057–64. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6057

61. Corbiere V, Chapiro J, Stroobant V, Ma W, Lurquin C, Lethe B, et al. Antigen spreading contributes to MAGE vaccination-induced regression of melanoma metastases. Cancer Res (2011) 71(4):1253–62. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2693

62. Lennerz V, Fatho M, Gentilini C, Frye RA, Lifke A, Ferel D, et al. The response of autologous T cells to a human melanoma is dominated by mutated neoantigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2005) 102(44):16013–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0500090102

63. Kawakami Y, Wang X, Shofuda T, Sumimoto H, Tupesis J, Fitzgerald E, et al. Isolation of a new melanoma antigen, MART-2, containing a mutated epitope recognized by autologous tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes. J Immunol (2001) 166(4):2871–7. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2871

64. Coulie PG, Lehmann F, Lethe B, Herman J, Lurquin C, Andrawiss M, et al. A mutated intron sequence codes for an antigenic peptide recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1995) 92(17):7976–80. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.17.7976

65. Chiari R, Foury F, De Plaen E, Baurain JF, Thonnard J, Coulie PG. Two antigens recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on a melanoma result from a single point mutation in an essential housekeeping gene. Cancer Res (1999) 59(22):5785–92.

66. Baurain JF, Colau D, van Baren N, Landry C, Martelange V, Vikkula M, et al. High frequency of autologous anti-melanoma CTL directed against an antigen generated by a point mutation in a new helicase gene. J Immunol (2000) 164(11):6057–66. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.6057

67. Zorn E, Hercend T. A natural cytotoxic T cell response in a spontaneously regressing human melanoma targets a neoantigen resulting from a somatic point mutation. Eur J Immunol (1999) 29(2):592–601. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199902)29:02<592::AID-IMMU592>3.0.CO;2-2

68. Linard B, Bezieau S, Benlalam H, Labarriere N, Guilloux Y, Diez E, et al. A ras-mutated peptide targeted by CTL infiltrating a human melanoma lesion. J Immunol (2002) 168(9):4802–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4802

69. Vigneron N, Ooms A, Morel S, Degiovanni G, Van Den Eynde BJ. Identification of a new peptide recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Cancer Immun (2002) 2:9.

70. Hogan KT, Eisinger DP, Cupp SB III, Lekstrom KJ, Deacon DD, Shabanowitz J, et al. The peptide recognized by HLA-A68.2-restricted, squamous cell carcinoma of the lung-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes is derived from a mutated elongation factor 2 gene. Cancer Res (1998) 58(22):5144–50.

71. Takenoyama M, Baurain JF, Yasuda M, So T, Sugaya M, Hanagiri T, et al. A point mutation in the NFYC gene generates an antigenic peptide recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human squamous cell lung carcinoma. Int J Cancer (2006) 118(8):1992–7. doi:10.1002/ijc.21594

72. Echchakir H, Mami-Chouaib F, Vergnon I, Baurain JF, Karanikas V, Chouaib S, et al. A point mutation in the alpha-actinin-4 gene generates an antigenic peptide recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human lung carcinoma. Cancer Res (2001) 61(10):4078–83.

73. Brandle D, Brasseur F, Weynants P, Boon T, Van den Eynde B. A mutated HLA-A2 molecule recognized by autologous cytotoxic T lymphocytes on a human renal cell carcinoma. J Exp Med (1996) 183(6):2501–8. doi:10.1084/jem.183.6.2501

74. Gaudin C, Kremer F, Angevin E, Scott V, Triebel F. A hsp70-2 mutation recognized by CTL on a human renal cell carcinoma. J Immunol (1999) 162(3):1730–8.

75. Maccalli C, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Rosenberg SA, Robbins PF. Identification of a colorectal tumor-associated antigen (COA-1) recognized by CD4(+) T lymphocytes. Cancer Res (2003) 63(20):6735–43.

76. Wang HY, Peng G, Guo Z, Shevach EM, Wang RF. Recognition of a new ARTC1 peptide ligand uniquely expressed in tumor cells by antigen-specific CD4+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol (2005) 174(5):2661–70. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2661

77. Wang RF, Wang X, Atwood AC, Topalian SL, Rosenberg SA. Cloning genes encoding MHC class II-restricted antigens: mutated CDC27 as a tumor antigen. Science (1999) 284(5418):1351–4. doi:10.1126/science.284.5418.1351

78. Wang HY, Zhou J, Zhu K, Riker AI, Marincola FM, Wang RF. Identification of a mutated fibronectin as a tumor antigen recognized by CD4+ T cells: its role in extracellular matrix formation and tumor metastasis. J Exp Med (2002) 195(11):1397–406. doi:10.1084/jem.20020141

79. Wang RF, Wang X, Rosenberg SA. Identification of a novel major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted tumor antigen resulting from a chromosomal rearrangement recognized by CD4(+) T cells. J Exp Med (1999) 189(10):1659–68. doi:10.1084/jem.189.10.1659

80. Topalian SL, Gonzales MI, Ward Y, Wang X, Wang RF. Revelation of a cryptic major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted tumor epitope in a novel RNA-processing enzyme. Cancer Res (2002) 62(19):5505–9.

81. Novellino L, Renkvist N, Rini F, Mazzocchi A, Rivoltini L, Greco A, et al. Identification of a mutated receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatase kappa as a novel, class II HLA-restricted melanoma antigen. J Immunol (2003) 170(12):6363–70. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6363

82. Pieper R, Christian RE, Gonzales MI, Nishimura MI, Gupta G, Settlage RE, et al. Biochemical identification of a mutated human melanoma antigen recognized by CD4(+) T cells. J Exp Med (1999) 189(5):757–66. doi:10.1084/jem.189.5.757

83. Gros A, Parkhurst MR, Tran E, Pasetto A, Robbins PF, Ilyas S, et al. Prospective identification of neoantigen-specific lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of melanoma patients. Nat Med (2016) 22(4):433–8. doi:10.1038/nm.4051

84. Sahin U, Derhovanessian E, Miller M, Kloke BP, Simon P, Lower M, et al. Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer. Nature (2017) 547(7662):222–6. doi:10.1038/nature23003

85. Robbins PF, Lu YC, El-Gamil M, Li YF, Gross C, Gartner J, et al. Mining exomic sequencing data to identify mutated antigens recognized by adoptively transferred tumor-reactive T cells. Nat Med (2013) 19(6):747–52. doi:10.1038/nm.3161

86. Wick DA, Webb JR, Nielsen JS, Martin SD, Kroeger DR, Milne K, et al. Surveillance of the tumor mutanome by T cells during progression from primary to recurrent ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2014) 20(5):1125–34. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2147

87. Rock KL, Goldberg AL. Degradation of cell proteins and the generation of MHC class I-presented peptides. Annu Rev Immunol (1999) 17:739–79. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.739

88. Hammer GE, Kanaseki T, Shastri N. The final touches make perfect the peptide-MHC class I repertoire. Immunity (2007) 26(4):397–406. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.003

89. Marincola FM, Jaffee EM, Hicklin DJ, Ferrone S. Escape of human solid tumors from T-cell recognition: molecular mechanisms and functional significance. Adv Immunol (2000) 74:181–273. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60911-6

90. Kessler JH, Khan S, Seifert U, Le Gall S, Chow KM, Paschen A, et al. Antigen processing by nardilysin and thimet oligopeptidase generates cytotoxic T cell epitopes. Nat Immunol (2011) 12(1):45–53. doi:10.1038/ni.1974

91. Parmentier N, Stroobant V, Colau D, de Diesbach P, Morel S, Chapiro J, et al. Production of an antigenic peptide by insulin-degrading enzyme. Nat Immunol (2010) 11(5):449–54. doi:10.1038/ni.1862

92. Medina F, Ramos M, Iborra S, de Leon P, Rodriguez-Castro M, Del Val M. Furin-processed antigens targeted to the secretory route elicit functional TAP1-/-CD8+ T lymphocytes in vivo. J Immunol (2009) 183(7):4639–47. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0901356

93. Van Hall T, Wolpert EZ, van Veelen P, Laban S, van der Veer M, Roseboom M, et al. Selective cytotoxic T-lymphocyte targeting of tumor immune escape variants. Nat Med (2006) 12(4):417–24. doi:10.1038/nm1381

94. El Hage F, Stroobant V, Vergnon I, Baurain JF, Echchakir H, Lazar V, et al. Preprocalcitonin signal peptide generates a cytotoxic T lymphocyte-defined tumor epitope processed by a proteasome-independent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2008) 105(29):10119–24. doi:10.1073/pnas.0802753105

95. Durgeau A, El Hage F, Vergnon I, Validire P, de Montpreville V, Besse B, et al. Different expression levels of the TAP peptide transporter lead to recognition of different antigenic peptides by tumor-specific CTL. J Immunol (2011) 187(11):5532–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1102060

96. Ngoenkam J, Schamel WW, Pongcharoen S. Selected signalling proteins recruited to the T-cell receptor-CD3 complex. Immunology (2017) 153(1):42–50. doi:10.1111/imm.12809

97. Alt FW, Oltz EM, Young F, Gorman J, Taccioli G, Chen J. VDJ recombination. Immunol Today (1992) 13(8):306–14. doi:10.1016/0167-5699(92)90043-7

98. Davis MM, Bjorkman PJ. T-cell antigen receptor genes and T-cell recognition. Nature (1988) 334(6181):395–402. doi:10.1038/334395a0

99. Pannetier C, Cochet M, Darche S, Casrouge A, Zoller M, Kourilsky P. The sizes of the CDR3 hypervariable regions of the murine T-cell receptor beta chains vary as a function of the recombined germ-line segments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1993) 90(9):4319–23. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.9.4319

100. Gorski J, Yassai M, Zhu X, Kissela B, Kissella B, Keever C, et al. Circulating T cell repertoire complexity in normal individuals and bone marrow recipients analyzed by CDR3 size spectratyping. Correlation with immune status. J Immunol (1994) 152(10):5109–19.

101. Xin-Sheng Y, Zheng-Jun X, Li M, Wan-Bang S, Wei-Yang Z, Qian W, et al. Analysis of the CDR3 region of alpha/beta T-cell receptors (TCRs) and TCR BD gene double-stranded recombination signal sequence breaks end in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Lab Haematol (2006) 28(6):405–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2257.2006.00827.x

102. Wang CY, Fang YX, Chen GH, Jia HJ, Zeng S, He XB, et al. Analysis of the CDR3 length repertoire and the diversity of T cell receptor alpha and beta chains in swine CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. Mol Med Rep (2017) 16(1):75–86. doi:10.3892/mmr.2016.5981

103. Ria F, van den Elzen P, Madakamutil LT, Miller JE, Maverakis E, Sercarz EE. Molecular characterization of the T cell repertoire using immunoscope analysis and its possible implementation in clinical practice. Curr Mol Med (2001) 1(3):297–304. doi:10.2174/1566524013363690

104. Even J, Lim A, Puisieux I, Ferradini L, Dietrich PY, Toubert A, et al. T-cell repertoires in healthy and diseased human tissues analysed by T-cell receptor beta-chain CDR3 size determination: evidence for oligoclonal expansions in tumours and inflammatory diseases. Res Immunol (1995) 146(2):65–80. doi:10.1016/0923-2494(96)80240-9

105. Gaudin C, Dietrich PY, Robache S, Guillard M, Escudier B, Lacombe MJ, et al. In vivo local expansion of clonal T cell subpopulations in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res (1995) 55(3):685–90.

106. Valteau D, Scott V, Carcelain G, Hartmann O, Escudier B, Hercend T, et al. T-cell receptor repertoire in neuroblastoma patients. Cancer Res (1996) 56(2):362–9.

107. Echchakir H, Asselin-Paturel C, Dorothee G, Vergnon I, Grunenwald D, Chouaib S, et al. Analysis of T-cell-receptor beta-chain-gene usage in peripheral-blood and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from human non-small-cell lung carcinomas. Int J Cancer (1999) 81(2):205–13. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990412)81:2<205::AID-IJC7>3.0.CO;2-M

108. Echchakir H, Dorothee G, Vergnon I, Menez J, Chouaib S, Mami-Chouaib F. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes directed against a tumor-specific mutated antigen display similar HLA tetramer binding but distinct functional avidity and tissue distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2002) 99(14):9358–63. doi:10.1073/pnas.142308199

109. Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Bussel A, Flageul B, Michel L, Dubertret L, Kourilsky P, et al. A prospective study on the evolution of the T-cell repertoire in patients with Sezary syndrome treated by extracorporeal photopheresis. Blood (2002) 100(6):2168–74.

110. Lim A, Baron V, Ferradini L, Bonneville M, Kourilsky P, Pannetier C. Combination of MHC-peptide multimer-based T cell sorting with the Immunoscope permits sensitive ex vivo quantitation and follow-up of human CD8+ T cell immune responses. J Immunol Methods (2002) 261(1–2):177–94. doi:10.1016/S0022-1759(02)00004-2

111. Holt RA, Jones SJ. The new paradigm of flow cell sequencing. Genome Res (2008) 18(6):839–46. doi:10.1101/gr.073262.107

112. Shendure J, Ji H. Next-generation DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol (2008) 26(10):1135–45. doi:10.1038/nbt1486

113. Woodsworth DJ, Castellarin M, Holt RA. Sequence analysis of T-cell repertoires in health and disease. Genome Med (2013) 5(10):98. doi:10.1186/gm502

114. Freeman JD, Warren RL, Webb JR, Nelson BH, Holt RA. Profiling the T-cell receptor beta-chain repertoire by massively parallel sequencing. Genome Res (2009) 19(10):1817–24. doi:10.1101/gr.092924.109

115. Boria I, Cotella D, Dianzani I, Santoro C, Sblattero D. Primer sets for cloning the human repertoire of T cell receptor variable regions. BMC Immunol (2008) 9:50. doi:10.1186/1471-2172-9-50

116. Warren RL, Nelson BH, Holt RA. Profiling model T-cell metagenomes with short reads. Bioinformatics (2009) 25(4):458–64. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp010

117. Linnemann C, Heemskerk B, Kvistborg P, Kluin RJ, Bolotin DA, Chen X, et al. High-throughput identification of antigen-specific TCRs by TCR gene capture. Nat Med (2013) 19(11):1534–41. doi:10.1038/nm.3359

118. Brown SD, Raeburn LA, Holt RA. Profiling tissue-resident T cell repertoires by RNA sequencing. Genome Med (2015) 7:125. doi:10.1186/s13073-015-0248-x

119. Li B, Li T, Pignon JC, Wang B, Wang J, Shukla SA, et al. Landscape of tumor-infiltrating T cell repertoire of human cancers. Nat Genet (2016) 48(7):725–32. doi:10.1038/ng.3581

120. Fang H, Yamaguchi R, Liu X, Daigo Y, Yew PY, Tanikawa C, et al. Quantitative T cell repertoire analysis by deep cDNA sequencing of T cell receptor alpha and beta chains using next-generation sequencing (NGS). Oncoimmunology (2014) 3(12):e968467. doi:10.4161/21624011.2014.968467

121. Reuben A, Gittelman R, Gao J, Zhang J, Yusko EC, Wu CJ, et al. TCR repertoire intratumor heterogeneity in localized lung adenocarcinomas: an association with predicted neoantigen heterogeneity and postsurgical recurrence. Cancer Discov (2017) 7(10):1088–97. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0256

122. Cha E, Klinger M, Hou Y, Cummings C, Ribas A, Faham M, et al. Improved survival with T cell clonotype stability after anti-CTLA-4 treatment in cancer patients. Sci Transl Med (2014) 6(238):238ra70. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3008211

123. Roh W, Chen PL, Reuben A, Spencer CN, Prieto PA, Miller JP, et al. Integrated molecular analysis of tumor biopsies on sequential CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade reveals markers of response and resistance. Sci Transl Med (2017) 9(379):eaah3560. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aah3560

124. Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, Shintaku IP, Taylor EJ, Robert L, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature (2014) 515(7528):568–71. doi:10.1038/nature13954

125. Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med (2010) 363(8):711–23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003466

126. Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, Shukla SA, Blank C, Zimmer L, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science (2015) 350(6257):207–11. doi:10.1126/science.aad0095

127. Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med (2015) 372(26):2521–32. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1503093

128. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med (2012) 366(26):2443–54. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1200690

129. Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (2016) 387(10027):1540–50. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7

130. Humphries C. Adoptive cell therapy: honing that killer instinct. Nature (2013) 504(7480):S13–5. doi:10.1038/504S13a

131. Maus MV, Fraietta JA, Levine BL, Kalos M, Zhao Y, June CH. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer or viruses. Annu Rev Immunol (2014) 32:189–225. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120136

132. Ott PA, Hu Z, Keskin DB, Shukla SA, Sun J, Bozym DJ, et al. An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma. Nature (2017) 547(7662):217–21. doi:10.1038/nature22991

133. Lerret NM, Marzo AL. Adoptive T-cell transfer combined with a single low dose of total body irradiation eradicates breast tumors. Oncoimmunology (2013) 2(2):e22731. doi:10.4161/onci.22731

134. Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Shelton TE, Even J, Rosenberg SA. Generation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cultures for use in adoptive transfer therapy for melanoma patients. J Immunother (2003) 26(4):332–42. doi:10.1097/00002371-200307000-00005

135. Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, Yang JC, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science (2002) 298(5594):850–4. doi:10.1126/science.1076514

136. Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Phan GQ, et al. Durable complete responses in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic melanoma using T-cell transfer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res (2011) 17(13):4550–7. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0116

137. Chandran SS, Somerville RPT, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Klebanoff CA, Goff SL, et al. Treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma with adoptive transfer of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes: a single-centre, two-stage, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol (2017) 18(6):792–802. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30251-6

138. Hinrichs CS, Rosenberg SA. Exploiting the curative potential of adoptive T-cell therapy for cancer. Immunol Rev (2014) 257(1):56–71. doi:10.1111/imr.12132

139. Dudley ME, Gross CA, Somerville RP, Hong Y, Schaub NP, Rosati SF, et al. Randomized selection design trial evaluating CD8+-enriched versus unselected tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for adoptive cell therapy for patients with melanoma. J Clin Oncol (2013) 31(17):2152–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6441

140. Pasetto A, Gros A, Robbins PF, Deniger DC, Prickett TD, Matus-Nicodemos R, et al. Tumor- and neoantigen-reactive T-cell receptors can be identified based on their frequency in fresh tumor. Cancer Immunol Res (2016) 4(9):734–43. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0001

141. Parkhurst M, Gros A, Pasetto A, Prickett T, Crystal JS, Robbins P, et al. Isolation of T-cell receptors specifically reactive with mutated tumor-associated antigens from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes based on CD137 expression. Clin Cancer Res (2017) 23(10):2491–505. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2680

142. Verdegaal EM, de Miranda NF, Visser M, Harryvan T, van Buuren MM, Andersen RS, et al. Neoantigen landscape dynamics during human melanoma-T cell interactions. Nature (2016) 536(7614):91–5. doi:10.1038/nature18945

143. Baitsch L, Baumgaertner P, Devevre E, Raghav SK, Legat A, Barba L, et al. Exhaustion of tumor-specific CD8(+) T cells in metastases from melanoma patients. J Clin Invest (2011) 121(6):2350–60. doi:10.1172/JCI46102

144. Djenidi F, Adam J, Goubar A, Durgeau A, Meurice G, de Montpreville V, et al. CD8+CD103+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are tumor-specific tissue-resident memory T cells and a prognostic factor for survival in lung cancer patients. J Immunol (2015) 194(7):3475–86. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1402711

145. Lanitis E, Dangaj D, Irving M, Coukos G. Mechanisms regulating T-cell infiltration and activity in solid tumors. Ann Oncol (2017) 28(suppl_12):xii18–32. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx238

146. Chmielewski M, Hombach AA, Abken H. Antigen-specific T-cell activation independently of the MHC: chimeric antigen receptor-redirected T cells. Front Immunol (2013) 4:371. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2013.00371

147. June CH. Remote controlled CARs: towards a safer therapy for leukemia. Cancer Immunol Res (2016) 4(8):643. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0132

148. Berry LJ, Moeller M, Darcy PK. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: the next generation of gene-engineered immune cells. Tissue Antigens (2009) 74(4):277–89. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01336.x

149. Atanackovic D, Radhakrishnan SV, Bhardwaj N, Luetkens T. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) therapy for multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol (2016) 172(5):685–98. doi:10.1111/bjh.13889

150. Rosenberg SA. Cell transfer immunotherapy for metastatic solid cancer – what clinicians need to know. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2011) 8(10):577–85. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.116

151. Ray S, Chhabra A, Chakraborty NG, Hegde U, Dorsky DI, Chodon T, et al. MHC-I-restricted melanoma antigen specific TCR-engineered human CD4+ T cells exhibit multifunctional effector and helper responses, in vitro. Clin Immunol (2010) 136(3):338–47. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2010.04.013

152. Sadelain M, Riviere I, Brentjens R. Targeting tumours with genetically enhanced T lymphocytes. Nat Rev Cancer (2003) 3(1):35–45. doi:10.1038/nrc971

153. Robbins PF, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Dudley ME, et al. Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J Clin Oncol (2011) 29(7):917–24. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2537

154. Irving M, Zoete V, Hebeisen M, Schmid D, Baumgartner P, Guillaume P, et al. Interplay between T cell receptor binding kinetics and the level of cognate peptide presented by major histocompatibility complexes governs CD8+ T cell responsiveness. J Biol Chem (2012) 287(27):23068–78. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.357673

155. Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Hughes MS, Yang JC, Sherry RM, et al. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science (2006) 314(5796):126–9. doi:10.1126/science.1129003

156. Johnson LA, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Cassard L, Yang JC, Hughes MS, et al. Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood (2009) 114(3):535–46. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-03-211714

157. Kochenderfer JN, Rosenberg SA. Treating B-cell cancer with T cells expressing anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2013) 10(5):267–76. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.46

158. Brentjens RJ, Riviere I, Park JH, Davila ML, Wang X, Stefanski J, et al. Safety and persistence of adoptively transferred autologous CD19-targeted T cells in patients with relapsed or chemotherapy refractory B-cell leukemias. Blood (2011) 118(18):4817–28. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-04-348540

159. Kalos M, Levine BL, Porter DL, Katz S, Grupp SA, Bagg A, et al. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci Transl Med (2011) 3(95):95ra73. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842

160. Brentjens RJ, Davila ML, Riviere I, Park J, Wang X, Cowell LG, et al. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med (2013) 5(177):177ra38. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3005930

161. Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med (2014) 371(16):1507–17. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1407222

162. Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, Cui YK, Delbrook C, Feldman SA, et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet (2015) 385(9967):517–28. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3

163. Beatty GL, Haas AR, Maus MV, Torigian DA, Soulen MC, Plesa G, et al. Mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor mRNA-engineered T cells induce anti-tumor activity in solid malignancies. Cancer Immunol Res (2014) 2(2):112–20. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0170

164. Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer (2012) 12(4):252–64. doi:10.1038/nrc3239

165. Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science (2015) 348(6230):56–61. doi:10.1126/science.aaa8172

166. Topalian SL, Wolchok JD, Chan TA, Mellman I, Palucka K, Banchereau J, et al. Immunotherapy: the path to win the war on cancer? Cell (2015) 161(2):185–6. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.045

167. Im SJ, Hashimoto M, Gerner MY, Lee J, Kissick HT, Burger MC, et al. Defining CD8+ T cells that provide the proliferative burst after PD-1 therapy. Nature (2016) 537(7620):417–21. doi:10.1038/nature19330

169. Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med (2015) 373(1):23–34. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504030

170. Sakuishi K, Apetoh L, Sullivan JM, Blazar BR, Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC. Targeting Tim-3 and PD-1 pathways to reverse T cell exhaustion and restore anti-tumor immunity. J Exp Med (2010) 207(10):2187–94. doi:10.1084/jem.20100643

171. Melero I, Grimaldi AM, Perez-Gracia JL, Ascierto PA. Clinical development of immunostimulatory monoclonal antibodies and opportunities for combination. Clin Cancer Res (2013) 19(5):997–1008. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2214

172. Dai M, Yip YY, Hellstrom I, Hellstrom KE. Curing mice with large tumors by locally delivering combinations of immunomodulatory antibodies. Clin Cancer Res (2015) 21(5):1127–38. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1339

173. Kvistborg P, Philips D, Kelderman S, Hageman L, Ottensmeier C, Joseph-Pietras D, et al. Anti-CTLA-4 therapy broadens the melanoma-reactive CD8+ T cell response. Sci Transl Med (2014) 6(254):254ra128. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3008918

174. Luksza M, Riaz N, Makarov V, Balachandran VP, Hellmann MD, Solovyov A, et al. A neoantigen fitness model predicts tumour response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Nature (2017) 551(7681):517–20. doi:10.1038/nature24473

175. Gilboa E. The makings of a tumor rejection antigen. Immunity (1999) 11(3):263–70. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80101-6

176. Zaretsky JM, Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Escuin-Ordinas H, Hugo W, Hu-Lieskovan S, et al. Mutations associated with acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med (2016) 375(9):819–29. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1604958

177. Shin DS, Zaretsky JM, Escuin-Ordinas H, Garcia-Diaz A, Hu-Lieskovan S, Kalbasi A, et al. Primary resistance to PD-1 blockade mediated by JAK1/2 mutations. Cancer Discov (2017) 7(2):188–201. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1223

178. Gao J, Shi LZ, Zhao H, Chen J, Xiong L, He Q, et al. Loss of IFN-gamma pathway genes in tumor cells as a mechanism of resistance to anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Cell (2016) 167(2):397–404.e9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.069

179. Palucka K, Banchereau J. Cancer immunotherapy via dendritic cells. Nat Rev Cancer (2012) 12(4):265–77. doi:10.1038/nrc3258

180. Finn OJ. Human tumor antigens yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Cancer Immunol Res (2017) 5(5):347–54. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0112

181. Parmiani G, Castelli C, Dalerba P, Mortarini R, Rivoltini L, Marincola FM, et al. Cancer immunotherapy with peptide-based vaccines: what have we achieved? Where are we going? J Natl Cancer Inst (2002) 94(11):805–18. doi:10.1093/jnci/94.11.805

182. Miller MJ, Foy KC, Kaumaya PT. Cancer immunotherapy: present status, future perspective, and a new paradigm of peptide immunotherapeutics. Discov Med (2013) 15(82):166–76.

183. Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P. Human T cell responses against melanoma. Annu Rev Immunol (2006) 24:175–208. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090733

184. Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Schwartzentruber DJ, Hwu P, Marincola FM, Topalian SL, et al. Immunologic and therapeutic evaluation of a synthetic peptide vaccine for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat Med (1998) 4(3):321–7. doi:10.1038/nm0398-321

185. Speiser DE, Baumgaertner P, Voelter V, Devevre E, Barbey C, Rufer N, et al. Unmodified self antigen triggers human CD8 T cells with stronger tumor reactivity than altered antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2008) 105(10):3849–54. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800080105

186. Quakkelaar ED, Melief CJ. Experience with synthetic vaccines for cancer and persistent virus infections in nonhuman primates and patients. Adv Immunol (2012) 114:77–106. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-396548-6.00004-4

187. Melief CJ, van Hall T, Arens R, Ossendorp F, van der Burg SH. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. J Clin Invest (2015) 125(9):3401–12. doi:10.1172/JCI80009

188. Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med (2004) 10(9):909–15. doi:10.1038/nm1100

189. Klebanoff CA, Acquavella N, Yu Z, Restifo NP. Therapeutic cancer vaccines: are we there yet? Immunol Rev (2011) 239(1):27–44. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00979.x

190. Robbins PF, Kassim SH, Tran TL, Crystal JS, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, et al. A pilot trial using lymphocytes genetically engineered with an NY-ESO-1-reactive T-cell receptor: long-term follow-up and correlates with response. Clin Cancer Res (2015) 21(5):1019–27. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2708

191. van der Burg SH, Arens R, Ossendorp F, van Hall T, Melief CJ. Vaccines for established cancer: overcoming the challenges posed by immune evasion. Nat Rev Cancer (2016) 16(4):219–33. doi:10.1038/nrc.2016.16

192. Heemskerk B, Kvistborg P, Schumacher TN. The cancer antigenome. EMBO J (2013) 32(2):194–203. doi:10.1038/emboj.2012.333

193. Tran E, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA. ’Final common pathway’ of human cancer immunotherapy: targeting random somatic mutations. Nat Immunol (2017) 18(3):255–62. doi:10.1038/ni.3682

194. Oliveira CC, Querido B, Sluijter M, de Groot AF, van der Zee R, Rabelink MJ, et al. New role of signal peptide peptidase to liberate C-terminal peptides for MHC class I presentation. J Immunol (2013) 191(8):4020–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1301496

195. Doorduijn EM, Sluijter M, Querido BJ, Oliveira CC, Achour A, Ossendorp F, et al. TAP-independent self-peptides enhance T cell recognition of immune-escaped tumors. J Clin Invest (2016) 126(2):784–94. doi:10.1172/JCI83671