- Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

Natural killer T (NKT) cells are specialized CD1d-restricted T cells that recognize lipid antigens. Following stimulation, NKT cells lead to downstream activation of both innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. This has impelled the development of NKT cell-targeted immunotherapies for treating cancer. In this review, we provide a brief overview of the stimulatory and regulatory functions of NKT cells in tumor immunity as well as highlight preclinical and clinical studies based on NKT cells. Finally, we discuss future perspectives to better harness the potential of NKT cells for cancer therapy.

Introduction

Both innate and adaptive immune systems respond to tumor cells and participate in immune-surveillance against tumor (1). Defined immune interactions in the context of cancer include recognition of tumor-associated antigens or cues by innate cell populations such as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) [macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), neutrophils, and natural killer (NK) cells (2)]. Innate immune cells rely on germline encoded pattern recognition receptors to recognize and elicit prompt response against cancer-associated danger signals, and also augment components of the adaptive immune system, composed of antigen-specific B and T cells (1). One of the key players that link the innate and adaptive immune systems is the natural killer T (NKT) cells (3–5). NKT cells are innate-like T lymphocytes that possess ability to quickly respond to antigenic stimulation and rapidly produce copious amounts of cytokines and chemokines (6). This rapid effect can modulate both innate and adaptive immunity and is important in influencing host immune responses to cancer (7).

Natural killer T cells are a heterogeneous subset of specialized T cells (8). These cells exhibit innate cell-like feature of quick response to antigenic exposure in combination with adaptive cell’s precision of antigenic recognition and diverse effector responses (9). Like conventional T cells, NKT cells undergo thymic development and selection and possess T cell receptor (TCR) to recognize antigens (10). However, unlike conventional T cells, TCR expressed by NKT cells recognize lipid antigens presented by the conserved and non-polymorphic MHC class 1 like molecule CD1d (11). In addition to TCRs, NKT cells also possess receptors for cytokines such as IL-12, IL-18, IL-25, and IL-23 similar to innate cells such as NK and innate lymphoid cells (12). These cytokine receptors can be activated by steady state expression of these inflammatory cytokines even in the absence of TCR signals. Thus, NKT cells can amalgamate signals from both TCR-mediated stimulations and inflammatory cytokines to manifest prompt release of an array of cytokines (13). These cytokines can in turn modulate different immune cells present in the tumor microenvironment (TME) thus influencing host immune responses to cancer. Their predominant tissue localization and ability to sense cancer-mediated changes in host lipid metabolism or breach in tissue integrity via recognition of endogenous lipids, makes NKT cells an ideal candidate for cancer immunotherapy (14).

Type I NKT Cells

Broadly, CD1d-restricted NKT cells can be divided into two main subsets based on their TCR diversity and antigen specificities. Type I (invariant) NKT cells, so named because of their limited TCR repertoire, express a semi-invariant TCR (iTCR) α chain (Vα14-Jα18 in mice, Vα24-Jα18 in humans) paired with a heterogeneous Vβ chain repertoire (V β 2,7 or 8.2 in mice and V β 11 in humans) (8, 9). The prototypic antigen for type I NKT cells is galactosylceramide (α-GalCer or KRN 7000), which was isolated from a marine sponge as part of an antitumor screen (15). α-GalCer is a potent activator of type I NKT cells, inducing them to release large amounts of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which helps activate both CD8+ T cells and APCs (16, 17). The primary techniques used to study type I NKT cells include staining and identification of type I NKT cells using CD1d-loaded α-GalCer tetramers, administering α-GalCer to activate and study the functions of type I NKT cells and finally using CD1d deficient mice (that lack both type I and type II NKT) or Jα18-deficient mice (lacking only type I NKT) (10). Recent published study reported that Jα18-deficient mice in addition to having deletion in the Traj18 gene segment (essential for type I NKT cell development), also exhibited overall lower TCR repertoire caused by influence of the transgene on rearrangements of several Jα segments upstream Traj18, complicating interpretations of data obtained from the Jα18-deficient mice (18). To overcome this drawback, a new strain of Jα18-deficient mice lacking type I NKT cells while maintaining the overall TCR repertoire has been generated, which should facilitate future studies on type I NKT cells (19). Type I NKT cells can be further subdivided based on the surface expression of CD4 and CD8 into CD4+ and CD4−CD8− (DN) subsets and a small fraction of CD8+ cells found in humans (6, 20–24). Type I NKT cells are present in different tissues in both mice and humans but at higher frequency in mice (25, 26). Two very unique characteristics of type I NKT cells are that they possess dual reactivity to both self and foreign lipids, and that even at steady state type I NKT cell have an activated/memory phenotype (6, 27, 28). Functionally distinct subsets of NKT cells analogous to Th1, Th2, Th17, and TFH subsets of conventional T cells have been described. These subsets express the corresponding cytokines, transcription factors and surface markers of their conventional T cell counterparts (29–31). Type I NKT cells have a unique developmental program that is regulated by a number of transcription factors (32). Transcriptionally, one of the key regulators of type I NKT cell development and activated memory phenotype is the transcription factor promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF). In fact, PLZF deficient mice show profound deficiency of type I NKT cells and cytokine production (33, 34). Other transcription factors that are known to impact type I NKT cell differentiation are c-Myc (35, 36), RORγt (37), c-Myb (38), Elf-1 (39), and Runx1 (40). Furthermore, transcription factors that control conventional T cell differentiation such as Th1 lineage specific transcription factor T-bet and Th2 specific transcription factor GATA-3 can also affect type I NKT cell development (41–43). Aside from transcription factors, SLAM-associated protein (SAP) signaling pathway can also selectively control expansion and differentiation of type I NKT cell (44, 45). Type I NKT cells have been shown to respond to both self and foreign α and β linked glycosphingolipids (GSL), ceramides, and phospholipids (46). Type I NKT cells have been reported to mostly aid in mounting an effective immune response against tumor (3, 5, 47–49).

Type II NKT Cells

Type II NKT cells also called diverse or variant NKT cells, are CD1d-restricted T cells that express more diverse alpha-beta TCRs and do not recognize α-GalCer (50). Type II NKT cells are major subset in humans with higher frequency as compared to type I NKT cells (51). Due to absence of specific markers and agonistic antigens to identify all type II NKT cells, characterization of these cells has been challenging. Different methodologies employed to characterize type II NKT cells include, comparing immune responses between Jα18−/− (lacking only type I NKT) and CD1d−/− (lacking both type I and type II NKT) mice, using 24 αβ TCR transgenic mice (that overexpresses Vα3.2/Vβ9 TCR from type II NKT cell hybridoma VIII24), using a Jα18-deficient IL-4 reporter mouse model, staining with antigen-loaded CD1d tetramer and asses binding to type II NKT hybridomas [reviewed in Ref. (46)]. The first major antigen identified for self-glycolipid reactive type II NKT cells in mice was myelin derived glycolipid sulfatide (25, 26, 52). Subsequently, sulfatide and lysosulfatide reactive CD1d-restricted human type II NKT cells have been reported (53, 54). Sulfatide specific type II NKT cells predominantly exhibit an oligoclonal TCR repertoire (V α 3/V α 1-J α 7/J α 9 and V β 8.1/V β 3.1-J β 2.7) (25). Other self-glycolipids such as β GlcCer and β GalCer have been shown to activate murine type II NKT cells (55–57). Our group recently reported that two major sphingolipids accumulated in Gaucher disease (GD), β-glucosylceramide (β GlcCer) and its deacylated product glucosylsphingosine, are recognized by murine and human type II NKT cells (57). In an earlier study, we have also shown that lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), lysophospholipid markedly upregulated in myeloma patients was an antigen for human type II NKT cells (58). Type II NKT cells can be distinguished from type I NKT cells by their predominance in humans versus mice, TCR binding and distinct antigen specificities (59). Crystal structures of type II NKT TCR-sulfatide/CD1d complex and type I NKT TCR-α-GalCer/CD1d complex provided insights into the mechanisms by which NKT TCRs recognize antigen (60). The type I NKT TCR was found to bind α-GalCer/CD1d complex in a rigid, parallel configuration mainly involving the α-chain. The key residues within the CDR2β, CDR3α, and CDR1α loops of the semi-iTCR of type I NKT cells were determined to be involved in the detection of the α-GalCer/CD1d complex (61). On the other hand, type II NKT TCRs contact their ligands primarily via their CDR3β loop rather than CDR3 α loops in an antiparallel fashion very similar to binding observed in some of the conventional MHC-restricted T cells (62). Ternary structure of sulfatide-reactive TCR molecules revealed that CDR3 α loop primarily contacted CD1d and the CDR3β determined the specificity of sulfatide antigen (63). The flexibility in binding of type II NKT TCR to its antigens akin to TCR–peptide–MHC complex resonates with its greater TCR diversity and ability to respond to wide range of ligands. However, despite striking difference between the two subsets, similarities among the two subsets have also been reported. For example, both type I and type II NKT cells are autoreactive and depend on the transcriptional regulator PLZF and SAP for their development (55, 64, 65). Although, many type II NKT cells seem to have activated/memory phenotype like type I NKT cells, in other studies including ours, a subset of type II NKT cells also displayed naïve T cell phenotype (CD45RA+, CD45RO−, CD62high, and CD69−/low) (66, 67). Type II NKT cell is activated mainly by TCR signaling following recognition of lipid/CD1d complex (56, 68) independent of either TLR signaling or presence of IL-12 (65, 69).

In tumor and autoimmune disease models, type II NKT cells are typically associated with immunosuppression (70–72).

How Do NKT Cell Target Tumor Cells?

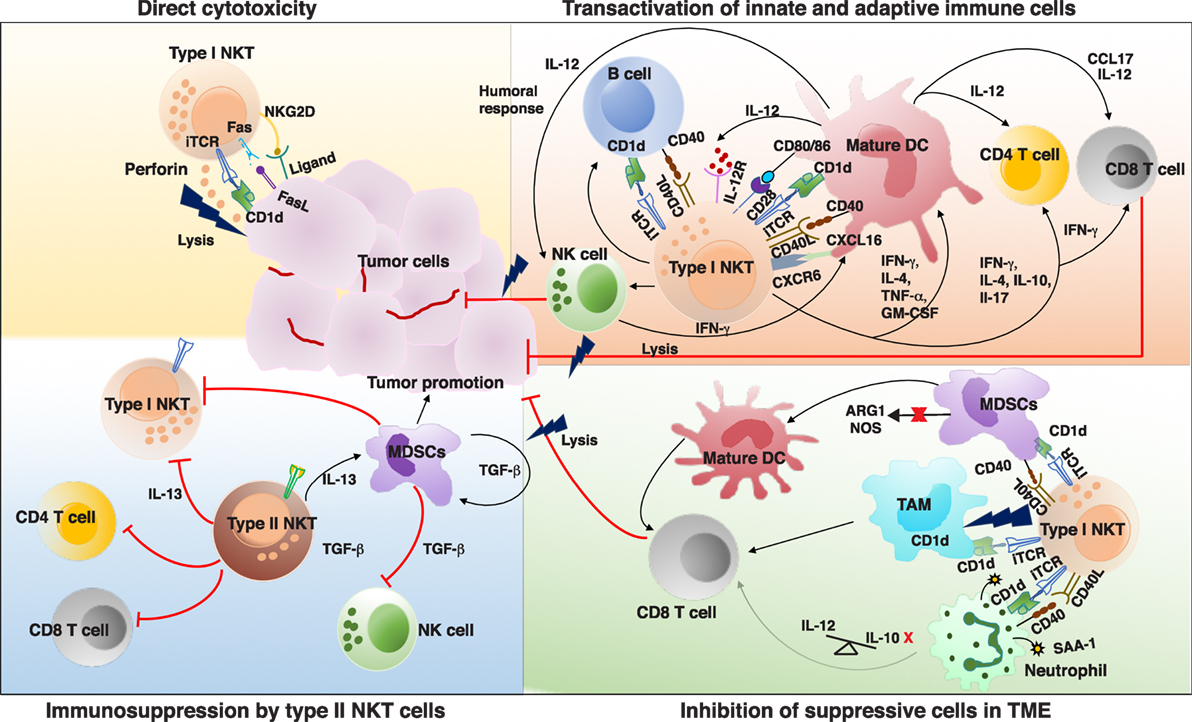

Several clues exist attributing a significant role of type I NKT cells in mediating protective immune response against tumors. Decreased frequency and function of type I NKT cells in the peripheral blood of different cancer patients is suggestive of their role in effective antitumor immunity (73–78). Increased frequency of peripheral blood type I NKT cells in cancer patients predicts a more favorable response to therapy (79, 80). Furthermore, recent studies found an association between number of tumor-infiltrating NKTs with better clinical outcome (79, 81). Notably, α-GalCer, the prototypic NKT ligand, was first discovered in a screen for antitumor agents (82). Many studies using genetic knockouts and murine models of tumor have been useful to discern the role of NKT cells in malignancy (83, 84). Type I NKT cells can lead to effective antitumor immunity by three mechanisms: (a) direct tumor lysis, (b) recruitment and activation of other innate and adaptive immune cells by initiating Th1 cytokine cascade, and (c) regulating immunosuppressive cells in TME (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Interactions and cross talk between different subsets of natural killer T (NKT) cells and other immune cells in tumor microenvironment (TME). Antigenic activated type I NKT cells can promote antitumor immunity by directly killing tumor cells in a CD1d-dependent and -independent mechanism. Type I NKT cells can recognize self or foreign lipid antigens presented by different CD1d-expressing antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in TME such as dendritic cells (DCs), TAMs, B cells, and neutrophils. On activation type I NKT cells can produce various Th1 and Th2 cytokines leading to reciprocal activation and or modulation of the APCs as well as other effector lymphocytes. Major type I NKT cytokine that helps activate DCs and CD8+ T cells is interferon-γ (IFN-γ). Type I NKT cells and DCs reciprocally activate each other via CD1d-TCR/lipid antigen and CD40–CD40L interactions. IL-12 produced by type I NKT cell matured DCs stimulates natural killer (NK), NKT, and MHC-restricted T cells to produce more IFN-γ which can secondarily activate other antitumor-promoting effector lymphocytes. Mature DCs derived factors as well as costimulatory receptors can activate CD8+ T cells to promote adaptive immunity. Type I NKT cells enhance tumor immunity by subduing the actions of tumor supporting cells such as TAMs, MDSCs, and suppressive neutrophils. In some instances, type II NKT cells have been shown to suppress the activation of type I NKT cells, T cells, NK cells and enhance development of tumor-associated MDSCs, aiding in tumor growth. iTCR, invariant TCR; IL-12, interleukin 12; IL-12R, IL-12 receptor; CXCL16, chemokine ligand 16; CXCR6, chemokine receptor 6; MDSCs, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; TAM, tumor-associated macrophages; ARG1, arginase 1; NOS, nitrous oxide synthase; SAA-1, serum amyloid A1; TCR, T cell receptor.

Direct Cytotoxicity Against Tumor Cells

Natural killer T cells can eliminate CD1d-expressing transformed cells by direct cytolysis using either perforin (85, 86), granzyme B, Fas ligand (FasL) (87, 88), or TNF-α-mediated cytotoxic pathways (89). Tumor cells expressing CD1d are mainly of myelomonocytic and B-cell lineages origin (90), and very few solid tumors have also been found to be CD1d-positive (91–95). Surface expression of CD1d on tumor cells is assumed to directly correlate with NKT cell-mediated cytotoxicity (96). With higher expression of CD1d, resulting in higher tumor cell lysis and thereby lower metastasis rates (92, 97), while lack of CD1d expression in tumors leads to their escape from recognition by NKT cells, and tumor progression in some models (90, 98, 99). These studies postulate that loss or downregulation of surface expression of CD1d favors tumor survival and permits tumor escape from NKT cell-mediated immunosurveillance. This concept is further strengthened by observations that downregulation of CD1d in human breast cancer and multiple Myeloma correlated with increased metastatic potential and disease progression (92, 99). Similarly, downregulation of CD1d by human papillomavirus in infected cervical epithelial cells was linked to their progression to cervical carcinoma (100). Another means by which tumor cells escape NKT cell-mediated antitumor response was shown in a mouse model of lymphoma, where shedding of tumor-associated glycolipids was shown to inhibit CD1-mediated presentation to NKT cells (101). Interestingly, in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), CD1d expression was found to increase during disease progression, counteracting the suggested role of CD1d as an anti-survival factor in cancer (102, 103). However, a recent study has shown that higher CD1d expression on CLL cells associated with disease progression actually led to impairment in both function and numbers of type I NKT cells (104). CD1d independent cytotoxic effect of NKT cells on various hematopoietic tumor cell lines have also been reported (98, 105, 106). Although, the mechanisms or tumor specific CD1d—glycolipid complex that helps NKT cells recognize and kill only CD1d-positive tumor cells and not normal cells is still enigmatic. Membrane glycolipids especially GSL such as globotriaosyl-ceramide (Gb3Cer/CD77), gangliosides (GD2, GD3, and GM2) have been shown to be overexpressed and altered in a range of cancers compared to normal tissue (107, 108). Shedding of some of the gangliosides and GSL into the TME have also been reported. Recognition of these overexpressed GSL and gangliosides on the surface of tumor cells may lead to differential recognition and killing of tumor cells by NKT cells.

Cytokine-Mediated Modulations of Effector Cells

In addition to direct tumor lysis, type I NKT cells can activate and recruit both innate and adaptive immune cells, such as DCs, NK cells, B cells, and T cells through rapid secretion of cytokines on activation (109). This is underscored by the observed increase in NK cells, CD8+ T cells and macrophages among tumor-infiltrating leukocytes brought about by α-GalCer injection (110). Owing to partially activated state and the presence of preformed cytosolic mRNA for various cytokines, type I NKT cells can rapidly produce broad spectrum of Th1 and Th2 cytokines on activation (111–113). The nature and magnitude of the type I NKT cell cytokine response is contingent on a number of variables that include the glycolipid antigen, subsets of NKT, and tissue location. For example, while α-GalCer-activated type I NKT cell primarily elicits an IFN-γ, a synthetic analog of α-GalCer with a truncated lipid chain OCH elicits majorly elicits IL-4 production (114). Further, DN liver subset of type I NKT was found to confer protection as compared to CD4+ liver subset or IL-4 inducing thymic type I NKT cells in MCA-induced fibrosarcoma model (115). Type I NKT cells play a crucial role in induction of early immune responses to tumor by influencing DC maturation (116). Mostly DCs found in TME are immature and inept at activating specific T cells (117). Maturation and differentiation of DCs is important in shaping the magnitude and polarization of T cell-mediated response (118). A mutually costimulatory interaction between DC and type I NKT cells ensues following encounter with CD1d/antigen complexes displayed by immature DCs. Ligation of APC-expressed CD40 with upregulated CD40L on type I NKT cells induces DCs’ maturation with higher surface expression of MHC class II, the costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80, CD86, CD70 and the endocytic receptor DEC205 and potent IL-12 production (119, 120). Sustained IL-12 secretion by mature DCs induces IFN-γ production by NKT cells (121–126). Mature DCs reciprocally enhance expression of CD40L and IL-12 receptor on type I NKT cells providing a strong feed forward signal that amplifies IFN-γ responses (119, 127). Ligation of chemokine receptor CXCR6 on the surface of type I NKT cells by its ligand CXCL16 expressed on APCs can also provide costimulatory signal resulting in robust α-GalCer-induced type I NKT activation (128, 129). α-GalCer-induced type I NKT cells can provide cognate licensing for cross-priming CD8 alpha + DCs to produce CCL17, which attracts CCR4+CD8+ T cells for subsequent activation (130, 131). Presence of phenotypic maturation ligands, suitable cytokines (IFN-γ), other functional immunostimulatory factors on type I NKT licensed DC can induce activation of CD8 T cells and their polarization toward antitumor effector function (119, 132–134). Release of various cytokines such as IL-2, IL-12, and IFN-γ by type I NKT cells leads to activation and expansion of NK cells into lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cells. These LAK cells upregulate the effectors or adhesion molecules such as perforin, NKp44, granzymes, FasL, and TRAIL and secrete IFN-γ to adhere and lyse tumor cells (135, 136). Type I NKT cells can form bidirectional interactions with B cells, wherein B cells can present lipid antigens to type I NKT cells through CD1d (137) and NKT cells can license B cells to effectively prime and activate antitumor CTL responses (138, 139) and can also directly provide B cell help to enhance and sustain humoral response (57, 140–143).

Altering the Effects of Immunosuppressive Cells in TME

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are prominent immunosuppressive immune cells present in the TME (144). TAMs contribute to tumor progression by enhancing angiogenesis, tumor cell invasion, suppression of NK, and T cell responses (145, 146). Type I NKT cells were found to co-localize with CD1d-expressing TAMs in neuroblastoma and kill TAMs in an IL-15 and CD1d-restricted manner (90, 147). Besides TAMs, type I NKTs can alter the effects of CD1d+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)-mediated immune suppression. MDSCs are heterogeneous population of cells of myeloid origin, which often accumulate during tumor growth and contribute to immune escape and tumor progression (148). In a model of influenza A viral infection, adoptive transfer of type I NKTs inhibited arginase 1 and nitrous oxide synthase-mediated suppressive activity of MDSCs. The ability of type I NKT cells to abolish the suppressive activity of MDSCs was found to be dependent on CD1d and CD40 interactions (149). In a tumor model, α-GalCer-loaded MDSCs facilitate conversion of immature MDSCs to mature APCs capable of eliciting cytotoxic NK and T cell immune response against cancer cells (150). De Santo et al. reported type I NKT cell-mediated reversal of immunosuppressive activity of neutrophils in melanoma, serum amyloid A1 (SAA-1) derived as consequence of tumor-associated inflammation induced differentiation of IL-10-producing neutrophils causing suppression of antigen-specific T cell responses. Conversely, SAA-1 also enhanced CD1d-CD40 dependent interaction between the suppressive neutrophils and type I NKT cells. This crosstalk lead to dephosphorylation of Erk, p38, and phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase, which in turn lead to inhibition of IL-10 secretion and promotion of IL-12 production by neutrophils, reinstating the proliferation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells (151).

Suppression of Tumor Immunity by Type II NKT Cells

In contrast to the established protective role of type I NKT in most murine tumor models, type II NKT cells have been shown to possess a more suppressive/regulatory role in tumor immunity (4, 59, 65, 152). Comparison of antitumor response in Jα18-deficient mice (which lack only type I NKT) with CD1d deficient mice (which lack both type I and II NKT cell) revealed that type II NKT cells were responsible for suppression of antitumor responses in several murine tumor models (152–154). Furthermore, sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells was shown to antagonize the protective antitumor immune responses mounted by α-GalCer-stimulated type I NKT cells (47). Sulfatide activated murine type II NKT cells were reported to inhibit proinflammatory functions of type I NKT cells, conventional T cells and DCs and also induce tolerization of myeloid DCs (155). A major attribute of type II NKT-mediated suppression of tumor immunity is elevated production of IL-13 and IL-4 cytokines capable of skewing the cytokine response predominantly toward tumor-promoting Th2 type. In a mouse model of transformed recurrent fibrosarcoma, type II NKT cells was shown to suppress cytotoxic T cells through IL-13 production via IL4R and STAT6 axis and also induce MDSCs producing immunosuppressive cytokine TGF-β (71). Similarly, LPC reactive type II NKT cells have been shown to preferentially produce IL-13 and exhibit immunoregulatory role in myeloma patients (58). Concentration of LPC, a phospholipid associated with inflammation, was found to be elevated in myeloma sera. Progressive myeloma disease is associated with a decline as well as dysfunctional activation of type I NKT cells and increased frequency of type II NKT cells (58, 78). The preferential production of IL-13, a cytokine implicated in promoting tumor growth, by LPC specific type II NKT cells suggests their role in disease progression (58). Recently, we have shown a possible implication of type II NKT cells in the development of B-cell malignancies associated with GD. GD is uniquely associated with increased cancer risk particularly with multiple myeloma (156). GD is a lysosomal storage disorder caused due to an inherited deficiency of the acidic β-glucosidase enzyme, resulting in marked accumulation of β-glucosylceramide (β GlcCer) and its deacylated product, glucosylsphingosine (LGL1). Increased frequency of LGL1-specific type II NKT cells with reduced frequency of type I NKT cells was observed in murine model and patients of GD. Interestingly, LGL1 reactive type II NKT cells demonstrated follicular helper T cell phenotype and were able to provide help to germinal center B cells to produce lipid-reactive antibodies (57). In both patients and mice with GD having monoclonal gammopathy, the monoclonal immunoglobulin was found to be reactive to Gaucher lipids (157). Though studies described earlier hint to pro- and antitumor functional dichotomy between type I and type II NKT, respectively, there are several emerging evidences challenging this paradigm, and the pro/antitumor roles of these cells may be context or activation-dependent. While type I NKT cells have been shown to assume immune-suppressive role in several tumor settings (158–161), a recent study showed that CpG-activated type II NKT cells secreted IFN-γ rather than IL-13, which in turn enhanced the activation and function of CD8+ T cells and contributed to the antitumor effect of CpG in the B16 melanoma model (162).

Preclinical Studies

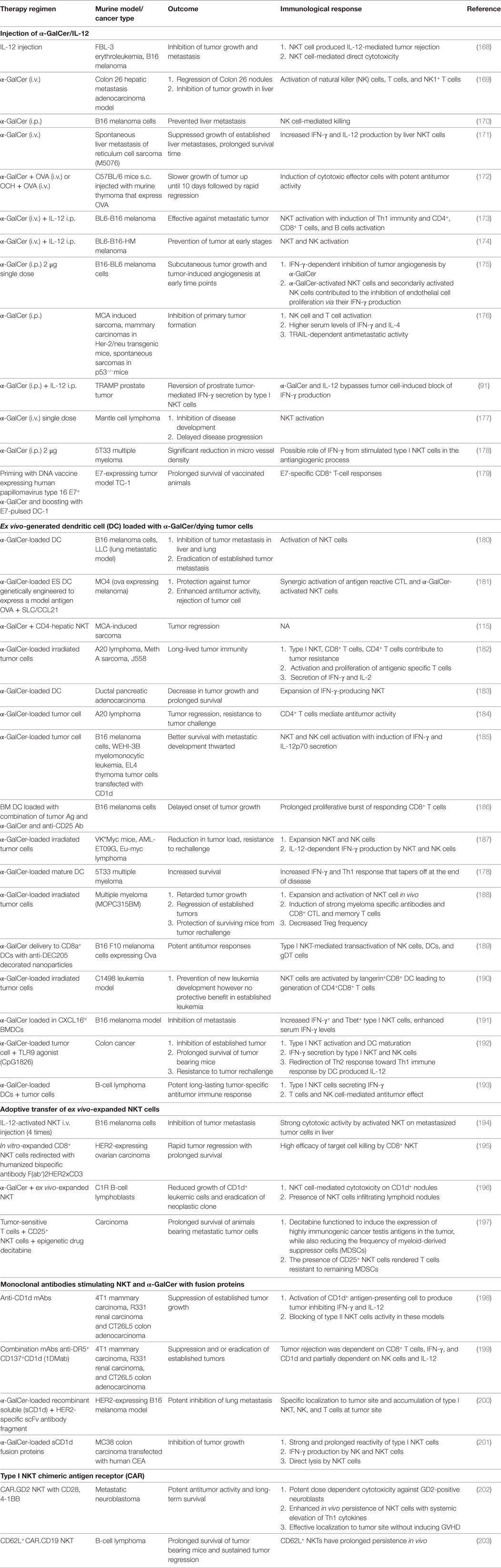

There are several theoretical advantages for harnessing type I NKT cells against cancer. NKT cell can simultaneously target both MHC positive and negative tumor cells due to ability to activate both antigen-specific CD8+ T cells and NK cells. Second, type I NKT cells show strong adjuvant activity thereby activating both innate and adaptive immune cells. Finally, NKT cells have the ability to convert immature and or tolerogenic DCs found in tumor bed into mature DCs capable of initiating tumor specific CD8+ T cell response. However, major limitations in targeting NKT cell for tumor treatment are the cancer-mediated reversible defect in the number and function of type I NKT cells (73, 74, 76–78, 80, 163, 164). Circulating type I NKT cell deficiency leads to decreased proliferation and IFN-γ production by type I NKT cells, consequently skewing immune response to a pro-tumor Th2 cytokine profile (73, 74, 76–78, 80, 163, 164). In line with this observation, reduced type I NKT cell frequency was shown to correlate with poor survival, while increased type I NKT cell numbers capable of making IFN-γ have positive prognostic value for survival in cancer patients (74, 80, 163–167). To restore the numbers and function of type I NKT cells in cancer patients and murine models, several approaches like administration of α-GalCer either alone or with IL-12, administration of APCs (DC or irradiated tumor cells) with α-GalCer, adoptive transfer of ex vivo expanded and/or activated type I NKT cells, and finally a combination of α-GalCer with antibodies or fusion proteins have been exploited. Data from numerous studies on variety of experimental and spontaneous murine tumor models have shown significant role for NKT cells in launching of powerful antitumor immune responses (Table 1).

Type I NKT cells were shown to be indispensable in mediating IL-12-mediated antitumor effects in low- and moderate-dose IL-12 treatment models (91, 169, 204). IL-12 was found to activate the NKT cell-mediated lysis of tumor cells and also induce IFN-γ production by type I NKT cells. Administration of soluble α-GalCer leads to activation and expansion of type I NKT cells, creating a milieu of immune-stimulatory cytokines including IFN-γ and costimulatory molecules, resulting in maturation of host APC thus enhancing antitumor T cell response. IFN-γ production by type I NKT cell was found to be pivotal in inducing NK cell activation, proliferation of memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cell effector functions, and inhibiting angiogenesis, all contributing to effective immune response against tumor. One of the major drawbacks of administering soluble free α-GalCer is that it causes type I NKT cell to adopt an anergic state causing unresponsiveness to sequential stimulation with α-GalCer (205). To circumvent this problem, mice were administrated DCs loaded with either α-GalCer alone or in combination with tumor antigens (180, 182, 187, 190, 206). α-GalCer-pulsed APCs induced a more prolonged cytokine response as well as powerful antitumor immune response than α-Galcer alone (180, 207). Another recent immunotherapeutic approach has been to load autologous irradiated tumors, which act as source of tumor antigens with α-GalCer (121, 182, 187, 188). A big improvement of this approach is CD1d-mediated cross-presentation of endogenous glycolipids and or α-GalCer from tumor cells to NKT cells, leading to DC maturation and consequently effective long-term T cell resistance to the tumor (128). Another approach involved adoptive transfer of ex vivo expanded and or activated type I NKT cells to restore type I NKT cell numbers in preclinical models of melanoma and lymphoid neoplasms (194, 196, 208). This approach has been shown to be more effective compared to the i.v. administration of α-GalCer (194). Finally, combination therapy using monoclonal Abs targeting CD1d alone or in combination with tumor cell death inducing and immunomodulating mAbs has emerged as promising immunotherapeutic candidate against CD1d-negative cancers (199). Stirnemann and Corgnac et al. attempted to target α-GalCer to tumor site by using constructs consisting of either α-GalCer/CD1d molecules alone or fused to tumor Ag specific scFv fragments in a colon carcinoma and murine melanoma model, respectively, and reported specific tumor localization of type I NKT activating potent antitumor responses compared to α-GalCer alone (200, 201). Preclinical studies obtained using chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) with engineered type I NKT cells have yielded promising result. CAR-bearing type I NKT cells effectively localized to the tumor sites, eliminating tumor cells, and exhibited potent and specific cytotoxicity against TAMs without producing graft-versus-host disease (202). Recently, CD62L+CD19−specific CAR-engineered NKT cells have been shown to possess superior therapeutic activity in a B-cell lymphoma model (203).

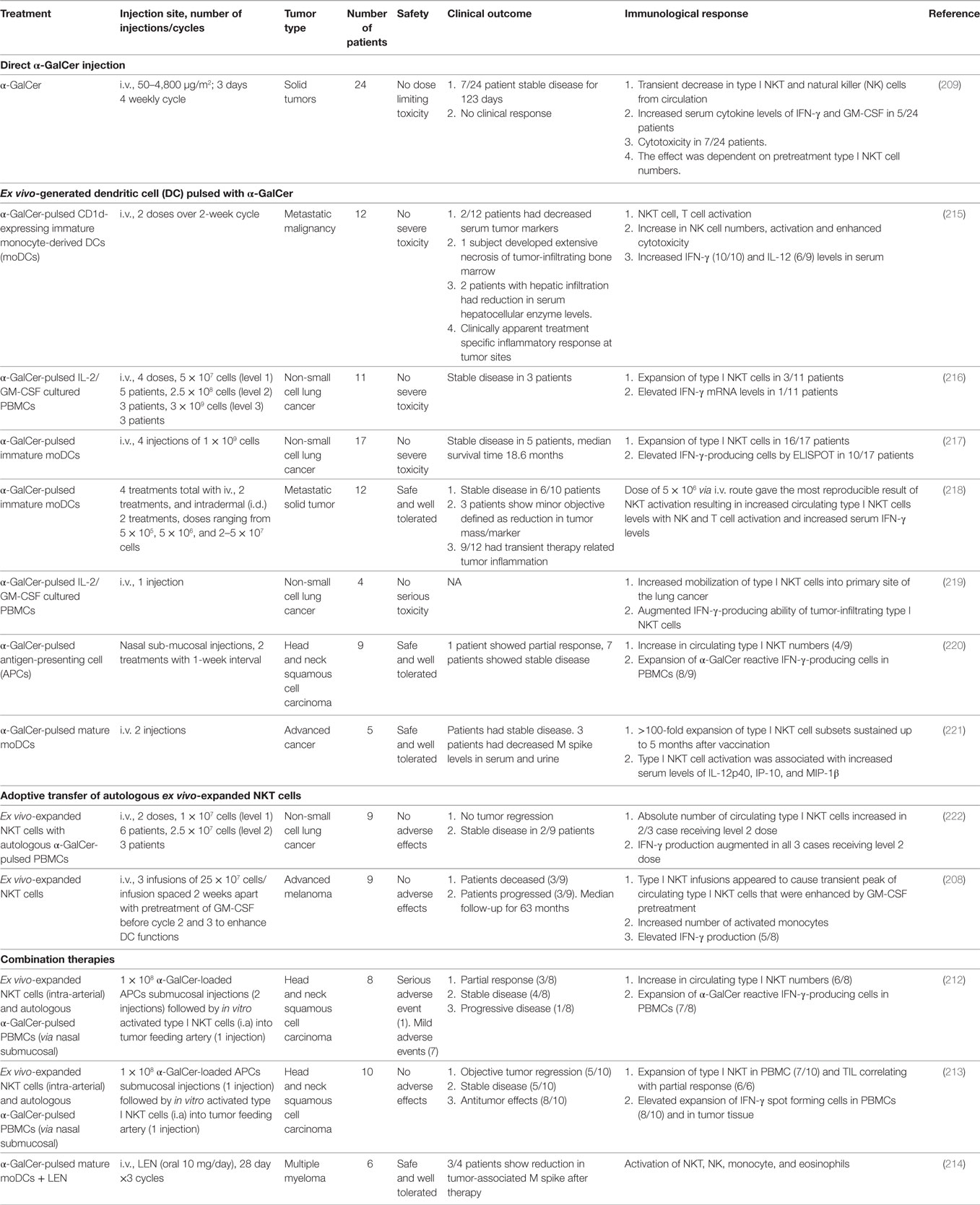

Clinical Trials of NKT Cells

Based on the preponderance of data from preclinical mice models, showing that activation of type I NKT cells plays a substantial role in providing protection against tumor growth and metastasis of several tumors, different clinical trials have been initiated to harness NKT cell’s antitumor potential (Table 2). However, while direct administration of soluble α-GalCer in cancer patients was well tolerated, it failed to yield any clinical response (209). Potential reasons for the low efficacy in human trials could be attributed to insufficient drug delivery, inter-individual variability and very low type I NKT cell numbers at baseline, induction of anergy or regulatory IL-10-producing type I NKT cells (205, 210, 211). To overcome these limitations of soluble α-GalCer administration and improve NKT-mediated antitumor responses, multiple clinical trials were performed using autologous α-GalCer-pulsed APCs in patients with advanced and recurrent non-small cell lung cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (Table 2). Different types of APCs and alternative routes to efficiently target activated NKT cells directly to cancer region were optimized to achieve objective antitumor responses. Though promising, this strategy too suffers from certain caveats like the treatment is again dependent on the baseline NKT levels, which are inevitably low in most cancer patients. Second, it is difficult to obtain large number of autologous monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs) from immune suppressed cancer patients and also cumbersome for ex vivo generation of DCs in compliance with good manufacturing practices regulations. Another strategy involves adoptive transfer of in vitro-expanded autologous type I NKT populations. Clinical trials using this approach in non-small cell lung cancer and advanced melanoma do show increase in type I NKT expansion and elevated serum IFN-γ levels in vivo; however, further optimization of the protocols and perhaps combination approaches such as combining with immune checkpoint blockade may be needed to obtain a significant clinical response. Remarkably, combining activated type I NKT cells and α-GalCer-pulsed APCs has been reported to enhance the low antitumor response observed with monotherapy employing either NKT or APCs alone in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients (212, 213). Similarly, combining regimen of α-GalCer-pulsed DCs and the immune-modulatory drug lenalidomide in treating multiple myeloma patients leads to type I NKT expansion with downstream activation of NK, monocytes and decrease in tumor-associated M spikes (214).

Emerging Approaches

Adoptive Transfer of Type I NKT Cells

Advanced cancer patients with low NKT cell numbers may benefit from development of in vitro methods for generation of large numbers of functional NKT cells which can be further used for adoptive transfers. NKT cells have been generated from CD34+ cells isolated from cord blood using IL-15 and stem cell factor (flt-3 ligand) in liquid culture system. Watarai et al. successfully differentiated murine induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into functional NKT cells in vitro that secreted large amounts of Th1 cytokine IFN-γ acting as adjuvant and antitumor agent (223). Recently, protocol to generate human type I NKT cells in vitro from iPSC that are competent in eliciting antitumor activity has been generated (224). Human type I NKT cells can also be reprogrammed to pluripotency followed by redifferentiation back to type I NKT cells in vitro using an IL-7/IL-15-based cytokine combination (225). The immunological features of re-differentiated type I NKT cells and their unlimited availability from iPSCs offer a potentially effective immunotherapy against cancer. Functionally mature human NKT cells have been also generated from bone marrow-derived adult hematopoietic stem-progenitor cells by expansion with CD1d-Ig-based artificial-presenting cells (226). Owing to the feasibility of producing large quantities of competent NKT cells, stem cell-derived type I NKT cells offer a promising strategy for effective anticancer immunotherapy.

Alternate Ligands

As discussed earlier, while α-GalCer is a potent activator of type I NKT cells, α-GalCer suffers from few drawback that limits its use as effective cancer immunotherapeutic. For example, α-GalCer induces anergy in type I NKT cells. This has led to preclinical exploration of several alternate ligands that are now poised to enter the clinic. Synthetic glycolipids or α-GalCer analogs chemically modified to induce more precise and predictable cytokine profile than α-GalCer have been synthesized and tested. These analogs as compared α-GalCer, show superior anticancer immunity in tumor mouse models and therefore hold great potential as an alternative vaccine adjuvant (227–229). As compared to α-GalCer, alternative non-glycosidic type I NKT-cell agonist threitol ceramide promoted stronger activation of human and mouse type I NKT cells and stronger antitumor responses in comparison to α-GalCer, making it potential candidate for NKT cell-based clinical trials (230). Another interesting prospect is encapsulating α-GalCer or other lipids in nanoparticle carriers or liposomes decorated with Abs or ligands to target specific APCs. These approaches have several advantages like slower release of α-GalCer, specific targeting of APC subset, lower amounts of α-GalCer required to activate NKT cells than soluble α-GalCer (231). Positive therapeutic effect of α-GalCer-loaded octa-arginine modified liposomes was reported in melanoma murine model (232). Administration of α-GalCer and ovalbumin coencapsulated PLGA nanoparticles provided significant prophylactic and therapeutic responses in mouse melanoma model by enhancing activation and tumor infiltration of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cell (233).

Combination Approaches

A major limitation of the initial studies targeting NKT cells in cancer is that these studies were conducted using single agent strategies and did not account for blockade of immune checkpoints or other immune-suppressive factors. PD-1:PD-L pathway has been shown to play an important role in mediating αGalCer-induced anergy in NKT cells. Antibody-mediated blockade of PD-1:PD-L interactions at the time of α-GalCer treatment prevent the induction of type I NKT anergy and also enhance the antitumor activities of αGalCer. Therefore, combination of NKT-targeted therapies with PD-1:PD-L blockade should be considered (234). Synthetic lipopeptide vaccines based on conjugation of MHC-binding peptide epitopes to α-GalCer displayed promising antitumor activity in a melanoma model. The principle behind these vaccines is to simultaneously provide both adjuvant and antigen to the same cell in a controlled fashion. Application of this vaccine technology using different tumor antigens might serve as a novel strategy for diverse malignancies (235). Combination of type I NKT-targeted DC vaccine with low dose of lenalidomide led to promising clinical activity in myeloma (214). Therefore, there is an unmet need to pursue combination approaches targeting type I NKT cells to better harness the antitumor properties of type I NKT cells in the clinic.

Concluding Remarks

Natural killer T cells are an important component of the TME and play key roles in regulating antitumor immunity. Although preclinical studies with NKT cell-targeted therapies in murine tumor models have been positive, clinical translation of these results has proven challenging. Translational challenge could be attributed to incomplete knowledge of human NKT subsets. Generation of improved preclinical models that replicate human NKT cell response is needed to gain insights into the cross talk between APCs and NKT subsets and to improve the efficacy of NKT cell-targeting therapies.

Author Contributions

Both SN and MVD participated in conceptualization and drafting of the article as well as critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. Both authors gave final approval of the submitted publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

MD is supported by funds from MMRF, LLS, IWMF, and NIH CA197603.

References

1. Gajewski TF, Schreiber H, Fu YX. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat Immunol (2013) 14:1014–22. doi:10.1038/ni.2703

2. Marcus A, Gowen BG, Thompson TW, Iannello A, Ardolino M, Deng W, et al. Recognition of tumors by the innate immune system and natural killer cells. Adv Immunol (2014) 122:91–128. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800267-4.00003-1

3. McEwen-Smith RM, Salio M, Cerundolo V. The regulatory role of invariant NKT cells in tumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Res (2015) 3:425–35. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0062

4. Terabe M, Berzofsky JA. The role of NKT cells in tumor immunity. Adv Cancer Res (2008) 101:277–348. doi:10.1016/S0065-230X(08)00408-9

5. Robertson FC, Berzofsky JA, Terabe M. NKT cell networks in the regulation of tumor immunity. Front Immunol (2014) 5:543. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00543

6. Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol (2007) 25:297–336. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711

7. Godfrey DI, Pellicci DG, Patel O, Kjer-Nielsen L, Mccluskey J, Rossjohn J. Antigen recognition by CD1d-restricted NKT T cell receptors. Semin Immunol (2010) 22:61–7. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2009.10.004

8. Brennan PJ, Brigl M, Brenner MB. Invariant natural killer T cells: an innate activation scheme linked to diverse effector functions. Nat Rev Immunol (2013) 13:101–17. doi:10.1038/nri3369

9. Salio M, Silk JD, Jones EY, Cerundolo V. Biology of CD1- and MR1-restricted T cells. Annu Rev Immunol (2014) 32:323–66. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120243

10. Berzins SP, Uldrich AP, Pellicci DG, Mcnab F, Hayakawa Y, Smyth MJ, et al. Parallels and distinctions between T and NKT cell development in the thymus. Immunol Cell Biol (2004) 82:269–75. doi:10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01256.x

11. Godfrey DI, Uldrich AP, Mccluskey J, Rossjohn J, Moody DB. The burgeoning family of unconventional T cells. Nat Immunol (2015) 16:1114–23. doi:10.1038/ni.3298

12. Cohen NR, Brennan PJ, Shay T, Watts GF, Brigl M, Kang J, et al. Shared and distinct transcriptional programs underlie the hybrid nature of iNKT cells. Nat Immunol (2013) 14:90–9. doi:10.1038/ni.2490

13. Kohlgruber AC, Donado CA, Lamarche NM, Brenner MB, Brennan PJ. Activation strategies for invariant natural killer T cells. Immunogenetics (2016) 68:649–63. doi:10.1007/s00251-016-0944-8

14. Fan X, Rudensky AY. Hallmarks of tissue-resident lymphocytes. Cell (2016) 164:1198–211. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.048

15. Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science (1997) 278:1626–9. doi:10.1126/science.278.5343.1626

16. Kronenberg M, Gapin L. The unconventional lifestyle of NKT cells. Nat Rev Immunol (2002) 2:557–68. doi:10.1038/nri854

17. Godfrey DI, Hammond KJ, Poulton LD, Smyth MJ, Baxter AG. NKT cells: facts, functions and fallacies. Immunol Today (2000) 21:573–83. doi:10.1016/S0167-5699(00)01735-7

18. Bedel R, Matsuda JL, Brigl M, White J, Kappler J, Marrack P, et al. Lower TCR repertoire diversity in Traj18-deficient mice. Nat Immunol (2012) 13:705–6. doi:10.1038/ni.2347

19. Chandra S, Zhao M, Budelsky A, De Mingo Pulido A, Day J, Fu Z, et al. A new mouse strain for the analysis of invariant NKT cell function. Nat Immunol (2015) 16:799–800. doi:10.1038/ni.3203

20. Bendelac A, Killeen N, Littman DR, Schwartz RH. A subset of CD4+ thymocytes selected by MHC class I molecules. Science (1994) 263:1774–8. doi:10.1126/science.7907820

21. Gadola SD, Dulphy N, Salio M, Cerundolo V. Valpha24-JalphaQ-independent, CD1d-restricted recognition of alpha-galactosylceramide by human CD4(+) and CD8alphabeta(+) T lymphocytes. J Immunol (2002) 168:5514–20. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5514

22. Gumperz JE, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Brenner MB. Functionally distinct subsets of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells revealed by CD1d tetramer staining. J Exp Med (2002) 195:625–36. doi:10.1084/jem.20011786

23. Lee H, Hong C, Shin J, Oh S, Jung S, Park YK, et al. The presence of CD8+ invariant NKT cells in mice. Exp Mol Med (2009) 41:866–72. doi:10.3858/emm.2009.41.12.092

24. Lee PT, Benlagha K, Teyton L, Bendelac A. Distinct functional lineages of human V(alpha)24 natural killer T cells. J Exp Med (2002) 195:637–41. doi:10.1084/jem.20011908

25. Arrenberg P, Halder R, Kumar V. Cross-regulation between distinct natural killer T cell subsets influences immune response to self and foreign antigens. J Cell Physiol (2009) 218:246–50. doi:10.1002/jcp.21597

26. Jahng AW, Maricic I, Pedersen B, Burdin N, Naidenko O, Kronenberg M, et al. Activation of natural killer T cells potentiates or prevents experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med (2001) 194:1789–99. doi:10.1084/jem.194.12.1789

27. Godfrey DI, Stankovic S, Baxter AG. Raising the NKT cell family. Nat Immunol (2010) 11:197–206. doi:10.1038/ni.1841

28. Wu L, Van Kaer L. Natural killer T cells and autoimmune disease. Curr Mol Med (2009) 9:4–14. doi:10.2174/156652409787314534

29. Constantinides MG, Bendelac A. Transcriptional regulation of the NKT cell lineage. Curr Opin Immunol (2013) 25:161–7. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2013.01.003

30. Coquet JM, Chakravarti S, Kyparissoudis K, Mcnab FW, Pitt LA, Mckenzie BS, et al. Diverse cytokine production by NKT cell subsets and identification of an IL-17-producing CD4-NK1.1- NKT cell population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2008) 105:11287–92. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801631105

31. Lee YJ, Wang H, Starrett GJ, Phuong V, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Tissue-specific distribution of iNKT cells impacts their cytokine response. Immunity (2015) 43:566–78. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.025

32. Das R, Sant’Angelo DB, Nichols KE. Transcriptional control of invariant NKT cell development. Immunol Rev (2010) 238:195–215. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00962.x

33. Kovalovsky D, Uche OU, Eladad S, Hobbs RM, Yi W, Alonzo E, et al. The BTB-zinc finger transcriptional regulator PLZF controls the development of invariant natural killer T cell effector functions. Nat Immunol (2008) 9:1055–64. doi:10.1038/ni.1641

34. Savage AK, Constantinides MG, Han J, Picard D, Martin E, Li B, et al. The transcription factor PLZF directs the effector program of the NKT cell lineage. Immunity (2008) 29:391–403. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.011

35. Dose M, Sleckman BP, Han J, Bredemeyer AL, Bendelac A, Gounari F. Intrathymic proliferation wave essential for Valpha14+ natural killer T cell development depends on c-Myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2009) 106:8641–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812255106

36. Mycko MP, Ferrero I, Wilson A, Jiang W, Bianchi T, Trumpp A, et al. Selective requirement for c-Myc at an early stage of V(alpha)14i NKT cell development. J Immunol (2009) 182:4641–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0803394

37. Michel ML, Mendes-Da-Cruz D, Keller AC, Lochner M, Schneider E, Dy M, et al. Critical role of ROR-gammat in a new thymic pathway leading to IL-17-producing invariant NKT cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2008) 105:19845–50. doi:10.1073/pnas.0806472105

38. Hu T, Simmons A, Yuan J, Bender TP, Alberola-ILA J. The transcription factor c-Myb primes CD4+CD8+ immature thymocytes for selection into the iNKT lineage. Nat Immunol (2010) 11:435–41. doi:10.1038/ni.1865

39. Choi HJ, Geng Y, Cho H, Li S, Giri PK, Felio K, et al. Differential requirements for the ETS transcription factor ELF-1 in the development of NKT cells and NK cells. Blood (2011) 117:1880–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-09-309468

40. Egawa T, Eberl G, Taniuchi I, Benlagha K, Geissmann F, Hennighausen L, et al. Genetic evidence supporting selection of the Valpha14i NKT cell lineage from double-positive thymocyte precursors. Immunity (2005) 22:705–16. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.011

41. Kim PJ, Pai SY, Brigl M, Besra GS, Gumperz J, Ho IC. GATA-3 regulates the development and function of invariant NKT cells. J Immunol (2006) 177:6650–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6650

42. Matsuda JL, Zhang Q, Ndonye R, Richardson SK, Howell AR, Gapin L. T-bet concomitantly controls migration, survival, and effector functions during the development of Valpha14i NKT cells. Blood (2006) 107:2797–805. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-08-3103

43. Townsend MJ, Weinmann AS, Matsuda JL, Salomon R, Farnham PJ, Biron CA, et al. T-bet regulates the terminal maturation and homeostasis of NK and Valpha14i NKT cells. Immunity (2004) 20:477–94. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(04)00076-7

44. Nichols KE, Hom J, Gong SY, Ganguly A, Ma CS, Cannons JL, et al. Regulation of NKT cell development by SAP, the protein defective in XLP. Nat Med (2005) 11:340–5. doi:10.1038/nm1189

45. Pasquier B, Yin L, Fondaneche MC, Relouzat F, Bloch-Queyrat C, Lambert N, et al. Defective NKT cell development in mice and humans lacking the adapter SAP, the X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome gene product. J Exp Med (2005) 201:695–701. doi:10.1084/jem.20042432

46. Macho-Fernandez E, Brigl M. The extended family of CD1d-restricted NKT cells: sifting through a mixed bag of TCRs, antigens, and functions. Front Immunol (2015) 6:362. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00362

47. Ambrosino E, Terabe M, Halder RC, Peng J, Takaku S, Miyake S, et al. Cross-regulation between type I and type II NKT cells in regulating tumor immunity: a new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol (2007) 179:5126–36. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5126

48. Pilones KA, Aryankalayil J, Demaria S. Invariant NKT cells as novel targets for immunotherapy in solid tumors. Clin Dev Immunol (2012) 2012:720803. doi:10.1155/2012/720803

49. Altman JB, Benavides AD, Das R, Bassiri H. Antitumor responses of invariant natural killer T cells. J Immunol Res (2015) 2015:652875. doi:10.1155/2015/652875

50. Cardell S, Tangri S, Chan S, Kronenberg M, Benoist C, Mathis D. CD1-restricted CD4+ T cells in major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. J Exp Med (1995) 182:993–1004. doi:10.1084/jem.182.4.993

51. Exley MA, Tahir SM, Cheng O, Shaulov A, Joyce R, Avigan D, et al. A major fraction of human bone marrow lymphocytes are Th2-like CD1d-reactive T cells that can suppress mixed lymphocyte responses. J Immunol (2001) 167:5531–4. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5531

52. Blomqvist M, Rhost S, Teneberg S, Lofbom L, Osterbye T, Brigl M, et al. Multiple tissue-specific isoforms of sulfatide activate CD1d-restricted type II NKT cells. Eur J Immunol (2009) 39:1726–35. doi:10.1002/eji.200839001

53. Fuss IJ, Joshi B, Yang Z, Degheidy H, Fichtner-Feigl S, De Souza H, et al. IL-13Ralpha2-bearing, type II NKT cells reactive to sulfatide self-antigen populate the mucosa of ulcerative colitis. Gut (2014) 63:1728–36. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305671

54. Yang SH, Lee JP, Jang HR, Cha RH, Han SS, Jeon US, et al. Sulfatide-reactive natural killer T cells abrogate ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol (2011) 22:1305–14. doi:10.1681/ASN.2010080815

55. Rhost S, Sedimbi S, Kadri N, Cardell SL. Immunomodulatory type II natural killer T lymphocytes in health and disease. Scand J Immunol (2012) 76:246–55. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.2012.02750.x

56. Roy KC, Maricic I, Khurana A, Smith TR, Halder RC, Kumar V. Involvement of secretory and endosomal compartments in presentation of an exogenous self-glycolipid to type II NKT cells. J Immunol (2008) 180:2942–50. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2942

57. Nair S, Boddupalli CS, Verma R, Liu J, Yang R, Pastores GM, et al. Type II NKT-TFH cells against Gaucher lipids regulate B-cell immunity and inflammation. Blood (2015) 125:1256–71. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-09-600270

58. Chang DH, Deng H, Matthews P, Krasovsky J, Ragupathi G, Spisek R, et al. Inflammation-associated lysophospholipids as ligands for CD1d-restricted T cells in human cancer. Blood (2008) 112:1308–16. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-04-149831

59. Dhodapkar MV, Kumar V. Type II NKT cells and their emerging role in health and disease. J Immunol (2017) 198:1015–21. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1601399

60. Girardi E, Zajonc DM. Molecular basis of lipid antigen presentation by CD1d and recognition by natural killer T cells. Immunol Rev (2012) 250:167–79. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01166.x

61. Pellicci DG, Patel O, Kjer-Nielsen L, Pang SS, Sullivan LC, Kyparissoudis K, et al. Differential recognition of CD1d-alpha-galactosyl ceramide by the V beta 8.2 and V beta 7 semi-invariant NKT T cell receptors. Immunity (2009) 31:47–59. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.018

62. Girardi E, Maricic I, Wang J, Mac TT, Iyer P, Kumar V, et al. Type II natural killer T cells use features of both innate-like and conventional T cells to recognize sulfatide self antigens. Nat Immunol (2012) 13:851–6. doi:10.1038/ni.2371

63. Patel O, Pellicci DG, Gras S, Sandoval-Romero ML, Uldrich AP, Mallevaey T, et al. Recognition of CD1d-sulfatide mediated by a type II natural killer T cell antigen receptor. Nat Immunol (2012) 13:857–63. doi:10.1038/ni.2372

64. Zhao J, Weng X, Bagchi S, Wang CR. Polyclonal type II natural killer T cells require PLZF and SAP for their development and contribute to CpG-mediated antitumor response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2014) 111:2674–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1323845111

65. Marrero I, Ware R, Kumar V. Type II NKT cells in inflammation, autoimmunity, microbial immunity, and cancer. Front Immunol (2015) 6:316. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00316

66. Arrenberg P, Halder R, Dai Y, Maricic I, Kumar V. Oligoclonality and innate-like features in the TCR repertoire of type II NKT cells reactive to a beta-linked self-glycolipid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2010) 107:10984–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000576107

67. Kadri N, Korpos E, Gupta S, Briet C, Lofbom L, Yagita H, et al. CD4(+) type II NKT cells mediate ICOS and programmed death-1-dependent regulation of type 1 diabetes. J Immunol (2012) 188:3138–49. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1101390

68. Tatituri RV, Watts GF, Bhowruth V, Barton N, Rothchild A, Hsu FF, et al. Recognition of microbial and mammalian phospholipid antigens by NKT cells with diverse TCRs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2013) 110:1827–32. doi:10.1073/pnas.1220601110

69. Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Primary immunodeficiency associated with defects in CD1 and CD1-restricted T cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2012) 1250:14–24. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06380.x

70. Moodycliffe AM, Nghiem D, Clydesdale G, Ullrich SE. Immune suppression and skin cancer development: regulation by NKT cells. Nat Immunol (2000) 1:521–5. doi:10.1038/82782

71. Terabe M, Matsui S, Noben-Trauth N, Chen H, Watson C, Donaldson DD, et al. NKT cell-mediated repression of tumor immunosurveillance by IL-13 and the IL-4R-STAT6 pathway. Nat Immunol (2000) 1:515–20. doi:10.1038/82771

72. Terabe M, Matsui S, Park JM, Mamura M, Noben-Trauth N, Donaldson DD, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta production and myeloid cells are an effector mechanism through which CD1d-restricted T cells block cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated tumor immunosurveillance: abrogation prevents tumor recurrence. J Exp Med (2003) 198:1741–52. doi:10.1084/jem.20022227

73. Tahir SM, Cheng O, Shaulov A, Koezuka Y, Bubley GJ, Wilson SB, et al. Loss of IFN-gamma production by invariant NK T cells in advanced cancer. J Immunol (2001) 167:4046–50. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.4046

74. Molling JW, Kolgen W, Van Der Vliet HJ, Boomsma MF, Kruizenga H, Smorenburg CH, et al. Peripheral blood IFN-gamma-secreting Valpha24+Vbeta11+ NKT cell numbers are decreased in cancer patients independent of tumor type or tumor load. Int J Cancer (2005) 116:87–93. doi:10.1002/ijc.20998

75. Yoneda K, Morii T, Nieda M, Tsukaguchi N, Amano I, Tanaka H, et al. The peripheral blood Valpha24+ NKT cell numbers decrease in patients with haematopoietic malignancy. Leuk Res (2005) 29:147–52. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2004.06.005

76. Yanagisawa K, Seino K, Ishikawa Y, Nozue M, Todoroki T, Fukao K. Impaired proliferative response of V alpha 24 NKT cells from cancer patients against alpha-galactosylceramide. J Immunol (2002) 168:6494–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6494

77. Fujii S, Shimizu K, Klimek V, Geller MD, Nimer SD, Dhodapkar MV. Severe and selective deficiency of interferon-gamma-producing invariant natural killer T cells in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol (2003) 122:617–22. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04465.x

78. Dhodapkar MV, Geller MD, Chang DH, Shimizu K, Fujii S, Dhodapkar KM, et al. A reversible defect in natural killer T cell function characterizes the progression of premalignant to malignant multiple myeloma. J Exp Med (2003) 197:1667–76. doi:10.1084/jem.20021650

79. Metelitsa LS, Wu HW, Wang H, Yang Y, Warsi Z, Asgharzadeh S, et al. Natural killer T cells infiltrate neuroblastomas expressing the chemokine CCL2. J Exp Med (2004) 199:1213–21. doi:10.1084/jem.20031462

80. Schneiders FL, De Bruin RC, Van Den Eertwegh AJ, Scheper RJ, Leemans CR, Brakenhoff RH, et al. Circulating invariant natural killer T-cell numbers predict outcome in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: updated analysis with 10-year follow-up. J Clin Oncol (2012) 30:567–70. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8819

81. Tachibana T, Onodera H, Tsuruyama T, Mori A, Nagayama S, Hiai H, et al. Increased intratumor Valpha24-positive natural killer T cells: a prognostic factor for primary colorectal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res (2005) 11:7322–7. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0877

82. Natori T, Koezuka Y, Higa T. Novel antitumor and immunostimulatory cerebrosides from the marine sponge Agelas mauritianus. Tetrahedron Lett (1993) 34:5591–2. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)73889-5

83. Shissler SC, Bollino DR, Tiper IV, Bates JP, Derakhshandeh R, Webb TJ. Immunotherapeutic strategies targeting natural killer T cell responses in cancer. Immunogenetics (2016) 68:623–38. doi:10.1007/s00251-016-0928-8

84. van der Vliet HJ, Molling JW, Von Blomberg BM, Nishi N, Kolgen W, Van Den Eertwegh AJ, et al. The immunoregulatory role of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells in disease. Clin Immunol (2004) 112:8–23. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2004.03.003

85. Bassiri H, Das R, Guan P, Barrett DM, Brennan PJ, Banerjee PP, et al. iNKT cell cytotoxic responses control T-lymphoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Immunol Res (2014) 2:59–69. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0104

86. Dao T, Mehal WZ, Crispe IN. IL-18 augments perforin-dependent cytotoxicity of liver NK-T cells. J Immunol (1998) 161:2217–22.

87. Leite-De-Moraes MC, Hameg A, Arnould A, Machavoine F, Koezuka Y, Schneider E, et al. A distinct IL-18-induced pathway to fully activate NK T lymphocytes independently from TCR engagement. J Immunol (1999) 163:5871–6.

88. Wingender G, Krebs P, Beutler B, Kronenberg M. Antigen-specific cytotoxicity by invariant NKT cells in vivo is CD95/CD178-dependent and is correlated with antigenic potency. J Immunol (2010) 185:2721–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1001018

89. Hagihara M, Gansuvd B, Ueda Y, Tsuchiya T, Masui A, Tazume K, et al. Killing activity of human umbilical cord blood-derived TCRValpha24(+) NKT cells against normal and malignant hematological cells in vitro: a comparative study with NK cells or OKT3 activated T lymphocytes or with adult peripheral blood NKT cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother (2002) 51:1–8. doi:10.1007/s00262-001-0246-2

90. Metelitsa LS. Anti-tumor potential of type-I NKT cells against CD1d-positive and CD1d-negative tumors in humans. Clin Immunol (2011) 140:119–29. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2010.10.005

91. Nowak M, Arredouani MS, Tun-Kyi A, Schmidt-Wolf I, Sanda MG, Balk SP, et al. Defective NKT cell activation by CD1d+ TRAMP prostate tumor cells is corrected by interleukin-12 with alpha-galactosylceramide. PLoS One (2010) 5:e11311. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011311

92. Hix LM, Shi YH, Brutkiewicz RR, Stein PL, Wang CR, Zhang M. CD1d-expressing breast cancer cells modulate NKT cell-mediated antitumor immunity in a murine model of breast cancer metastasis. PLoS One (2011) 6:e20702. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020702

93. Chong TW, Goh FY, Sim MY, Huang HH, Thike AA, Lim WK, et al. CD1d expression in renal cell carcinoma is associated with higher relapse rates, poorer cancer-specific and overall survival. J Clin Pathol (2015) 68:200–5. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202735

94. Dhodapkar KM, Cirignano B, Chamian F, Zagzag D, Miller DC, Finlay JL, et al. Invariant natural killer T cells are preserved in patients with glioma and exhibit antitumor lytic activity following dendritic cell-mediated expansion. Int J Cancer (2004) 109:893–9. doi:10.1002/ijc.20050

95. Liu D, Song L, Brawley VS, Robison N, Wei J, Gao X, et al. Medulloblastoma expresses CD1d and can be targeted for immunotherapy with NKT cells. Clin Immunol (2013) 149:55–64. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2013.06.005

96. Haraguchi K, Takahashi T, Nakahara F, Matsumoto A, Kurokawa M, Ogawa S, et al. CD1d expression level in tumor cells is an important determinant for anti-tumor immunity by natural killer T cells. Leuk Lymphoma (2006) 47:2218–23. doi:10.1080/10428190600682688

97. Fallarini S, Paoletti T, Orsi Battaglini N, Lombardi G. Invariant NKT cells increase drug-induced osteosarcoma cell death. Br J Pharmacol (2012) 167:1533–49. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02108.x

98. Nicol A, Nieda M, Koezuka Y, Porcelli S, Suzuki K, Tadokoro K, et al. Human invariant valpha24+ natural killer T cells activated by alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) have cytotoxic anti-tumour activity through mechanisms distinct from T cells and natural killer cells. Immunology (2000) 99:229–34. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00952.x

99. Spanoudakis E, Hu M, Naresh K, Terpos E, Melo V, Reid A, et al. Regulation of multiple myeloma survival and progression by CD1d. Blood (2009) 113:2498–507. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-06-161281

100. Miura S, Kawana K, Schust DJ, Fujii T, Yokoyama T, Iwasawa Y, et al. CD1d, a sentinel molecule bridging innate and adaptive immunity, is downregulated by the human papillomavirus (HPV) E5 protein: a possible mechanism for immune evasion by HPV. J Virol (2010) 84:11614–23. doi:10.1128/JVI.01053-10

101. Sriram V, Cho S, Li P, O’Donnell PW, Dunn C, Hayakawa K, et al. Inhibition of glycolipid shedding rescues recognition of a CD1+ T cell lymphoma by natural killer T (NKT) cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2002) 99:8197–202. doi:10.1073/pnas.122636199

102. Anastasiadis A, Kotsianidis I, Papadopoulos V, Spanoudakis E, Margaritis D, Christoforidou A, et al. CD1d expression as a prognostic marker for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma (2014) 55:320–5. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.803222

103. Bojarska-Junak A, Hus I, Chocholska S, Tomczak W, Wos J, Czubak P, et al. CD1d expression is higher in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with unfavorable prognosis. Leuk Res (2014) 38:435–42. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2013.12.015

104. Gorini F, Azzimonti L, Delfanti G, Scarfo L, Scielzo C, Bertilaccio MT, et al. Invariant NKT cells contribute to chronic lymphocytic leukemia surveillance and prognosis. Blood (2017) 129:3440–51. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-11-751065

105. Kawano T, Nakayama T, Kamada N, Kaneko Y, Harada M, Ogura N, et al. Antitumor cytotoxicity mediated by ligand-activated human V alpha24 NKT cells. Cancer Res (1999) 59:5102–5.

106. Gansuvd B, Hagihara M, Yu Y, Inoue H, Ueda Y, Tsuchiya T, et al. Human umbilical cord blood NK T cells kill tumors by multiple cytotoxic mechanisms. Hum Immunol (2002) 63:164–75. doi:10.1016/S0198-8859(01)00382-2

107. Durrant LG, Noble P, Spendlove I. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on cancer: glycolipids as targets for tumour immunotherapy. Clin Exp Immunol (2012) 167:206–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04516.x

108. Hakomori S. Tumor malignancy defined by aberrant glycosylation and sphingo(glyco)lipid metabolism. Cancer Res (1996) 56:5309–18.

109. Parekh VV, Lalani S, Van Kaer L. The in vivo response of invariant natural killer T cells to glycolipid antigens. Int Rev Immunol (2007) 26:31–48. doi:10.1080/08830180601070179

110. Nakagawa R, Serizawa I, Motoki K, Sato M, Ueno H, Iijima R, et al. Antitumor activity of alpha-galactosylceramide, KRN7000, in mice with the melanoma B16 hepatic metastasis and immunohistological study of tumor infiltrating cells. Oncol Res (2000) 12:51–8. doi:10.3727/096504001108747521

111. Stetson DB, Mohrs M, Reinhardt RL, Baron JL, Wang ZE, Gapin L, et al. Constitutive cytokine mRNAs mark natural killer (NK) and NK T cells poised for rapid effector function. J Exp Med (2003) 198:1069–76. doi:10.1084/jem.20030630

112. Matsuda JL, Mallevaey T, Scott-Browne J, Gapin L. CD1d-restricted iNKT cells, the ‘Swiss-Army knife’ of the immune system. Curr Opin Immunol (2008) 20:358–68. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.018

113. Monteiro M, Graca L. iNKT cells: innate lymphocytes with a diverse response. Crit Rev Immunol (2014) 34:81–90. doi:10.1615/CritRevImmunol.2014010088

114. Sullivan BA, Nagarajan NA, Wingender G, Wang J, Scott I, Tsuji M, et al. Mechanisms for glycolipid antigen-driven cytokine polarization by Valpha14i NKT cells. J Immunol (2010) 184:141–53. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0902880

115. Crowe NY, Coquet JM, Berzins SP, Kyparissoudis K, Keating R, Pellicci DG, et al. Differential antitumor immunity mediated by NKT cell subsets in vivo. J Exp Med (2005) 202:1279–88. doi:10.1084/jem.20050953

116. Keller CW, Freigang S, Lunemann JD. Reciprocal crosstalk between dendritic cells and natural killer T cells: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Front Immunol (2017) 8:570. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00570

117. Dudek AM, Martin S, Garg AD, Agostinis P. Immature, semi-mature, and fully mature dendritic cells: toward a DC-cancer cells interface that augments anticancer immunity. Front Immunol (2013) 4:438. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2013.00438

118. de Jong EC, Smits HH, Kapsenberg ML. Dendritic cell-mediated T cell polarization. Springer Semin Immunopathol (2005) 26:289–307. doi:10.1007/s00281-004-0167-1

119. Kitamura H, Iwakabe K, Yahata T, Nishimura S, Ohta A, Ohmi Y, et al. The natural killer T (NKT) cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide demonstrates its immunopotentiating effect by inducing interleukin (IL)-12 production by dendritic cells and IL-12 receptor expression on NKT cells. J Exp Med (1999) 189:1121–8. doi:10.1084/jem.189.7.1121

120. Tomura M, Yu WG, Ahn HJ, Yamashita M, Yang YF, Ono S, et al. A novel function of Valpha14+CD4+NKT cells: stimulation of IL-12 production by antigen-presenting cells in the innate immune system. J Immunol (1999) 163:93–101.

121. Shimizu K, Hidaka M, Kadowaki N, Makita N, Konishi N, Fujimoto K, et al. Evaluation of the function of human invariant NKT cells from cancer patients using alpha-galactosylceramide-loaded murine dendritic cells. J Immunol (2006) 177:3484–92. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3484

122. Munz C, Steinman RM, Fujii S. Dendritic cell maturation by innate lymphocytes: coordinated stimulation of innate and adaptive immunity. J Exp Med (2005) 202:203–7. doi:10.1084/jem.20050810

123. Fujii S, Shimizu K, Hemmi H, Fukui M, Bonito AJ, Chen G, et al. Glycolipid alpha-C-galactosylceramide is a distinct inducer of dendritic cell function during innate and adaptive immune responses of mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2006) 103:11252–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604812103

124. Fujii S, Shimizu K, Hemmi H, Steinman RM. Innate Valpha14(+) natural killer T cells mature dendritic cells, leading to strong adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev (2007) 220:183–98. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00561.x

125. Hermans IF, Silk JD, Gileadi U, Salio M, Mathew B, Ritter G, et al. Nkt cells enhance CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to soluble antigen in vivo through direct interaction with dendritic cells. J Immunol (2003) 171:5140–7. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5140

126. Brigl M, Tatituri RV, Watts GF, Bhowruth V, Leadbetter EA, Barton N, et al. Innate and cytokine-driven signals, rather than microbial antigens, dominate in natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. J Exp Med (2011) 208:1163–77. doi:10.1084/jem.20102555

127. Hayakawa Y, Godfrey DI, Smyth MJ. Alpha-galactosylceramide: potential immunomodulatory activity and future application. Curr Med Chem (2004) 11:241–52. doi:10.2174/0929867043456115

128. Shimaoka T, Seino K, Kume N, Minami M, Nishime C, Suematsu M, et al. Critical role for Cxc chemokine ligand 16 (SR-PSOX) in Th1 response mediated by NKT cells. J Immunol (2007) 179:8172–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8172

129. Germanov E, Veinotte L, Cullen R, Chamberlain E, Butcher EC, Johnston B. Critical role for the chemokine receptor CXCR6 in homeostasis and activation of CD1d-restricted NKT cells. J Immunol (2008) 181:81–91. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.81

130. Semmling V, Lukacs-Kornek V, Thaiss CA, Quast T, Hochheiser K, Panzer U, et al. Alternative cross-priming through CCL17-CCR4-mediated attraction of CTLs toward NKT cell-licensed DCs. Nat Immunol (2010) 11:313–20. doi:10.1038/ni.1848

131. Gottschalk C, Mettke E, Kurts C. The role of invariant natural killer T cells in dendritic cell licensing, cross-priming, and memory CD8(+) T cell generation. Front Immunol (2015) 6:379. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00379

132. Vincent MS, Leslie DS, Gumperz JE, Xiong X, Grant EP, Brenner MB. CD1-dependent dendritic cell instruction. Nat Immunol (2002) 3:1163–8. doi:10.1038/ni851

133. Taraban VY, Martin S, Attfield KE, Glennie MJ, Elliott T, Elewaut D, et al. Invariant NKT cells promote CD8+ cytotoxic T cell responses by inducing CD70 expression on dendritic cells. J Immunol (2008) 180:4615–20. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4615

134. Fujii S, Shimizu K, Smith C, Bonifaz L, Steinman RM. Activation of natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide rapidly induces the full maturation of dendritic cells in vivo and thereby acts as an adjuvant for combined CD4 and CD8 T cell immunity to a coadministered protein. J Exp Med (2003) 198:267–79. doi:10.1084/jem.20030324

135. Trinchieri G. Natural killer cells wear different hats: effector cells of innate resistance and regulatory cells of adaptive immunity and of hematopoiesis. Semin Immunol (1995) 7:83–8. doi:10.1006/smim.1995.0012

136. Smyth MJ, Swann J, Kelly JM, Cretney E, Yokoyama WM, Diefenbach A, et al. NKG2D recognition and perforin effector function mediate effective cytokine immunotherapy of cancer. J Exp Med (2004) 200:1325–35. doi:10.1084/jem.20041522

137. Chaudhry MS, Karadimitris A. Role and regulation of CD1d in normal and pathological B cells. J Immunol (2014) 193:4761–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1401805

138. Chung Y, Kim BS, Kim YJ, Ko HJ, Ko SY, Kim DH, et al. CD1d-restricted T cells license B cells to generate long-lasting cytotoxic antitumor immunity in vivo. Cancer Res (2006) 66:6843–50. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0889

139. Kim YJ, Ko HJ, Kim YS, Kim DH, Kang S, Kim JM, et al. alpha-Galactosylceramide-loaded, antigen-expressing B cells prime a wide spectrum of antitumor immunity. Int J Cancer (2008) 122:2774–83. doi:10.1002/ijc.23444

140. Barral P, Eckl-Dorna J, Harwood NE, De Santo C, Salio M, Illarionov P, et al. B cell receptor-mediated uptake of CD1d-restricted antigen augments antibody responses by recruiting invariant NKT cell help in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2008) 105:8345–50. doi:10.1073/pnas.0802968105

141. Leadbetter EA, Brigl M, Illarionov P, Cohen N, Luteran MC, Pillai S, et al. NK T cells provide lipid antigen-specific cognate help for B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2008) 105:8339–44. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801375105

142. Dellabona P, Abrignani S, Casorati G. iNKT-cell help to B cells: a cooperative job between innate and adaptive immune responses. Eur J Immunol (2014) 44:2230–7. doi:10.1002/eji.201344399

143. Galli G, Nuti S, Tavarini S, Galli-Stampino L, De Lalla C, Casorati G, et al. CD1d-restricted help to B cells by human invariant natural killer T lymphocytes. J Exp Med (2003) 197:1051–7. doi:10.1084/jem.20021616

144. Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi L, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2017) 14:399–416. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.217

145. Coussens LM, Zitvogel L, Palucka AK. Neutralizing tumor-promoting chronic inflammation: a magic bullet? Science (2013) 339:286–91. doi:10.1126/science.1232227

146. Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell (2010) 141:39–51. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014

147. Song L, Asgharzadeh S, Salo J, Engell K, Wu HW, Sposto R, et al. Valpha24-invariant NKT cells mediate antitumor activity via killing of tumor-associated macrophages. J Clin Invest (2009) 119:1524–36. doi:10.1172/JCI37869

148. Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol (2009) 9:162–74. doi:10.1038/nri2506

149. De Santo C, Salio M, Masri SH, Lee LY, Dong T, Speak AO, et al. Invariant NKT cells reduce the immunosuppressive activity of influenza A virus-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mice and humans. J Clin Invest (2008) 118:4036–48. doi:10.1172/JCI36264

150. Ko HJ, Lee JM, Kim YJ, Kim YS, Lee KA, Kang CY. Immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells can be converted into immunogenic APCs with the help of activated NKT cells: an alternative cell-based antitumor vaccine. J Immunol (2009) 182:1818–28. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0802430

151. De Santo C, Arscott R, Booth S, Karydis I, Jones M, Asher R, et al. Invariant NKT cells modulate the suppressive activity of IL-10-secreting neutrophils differentiated with serum amyloid A. Nat Immunol (2010) 11:1039–46. doi:10.1038/ni.1942

152. Terabe M, Swann J, Ambrosino E, Sinha P, Takaku S, Hayakawa Y, et al. A nonclassical non-Valpha14Jalpha18 CD1d-restricted (type II) NKT cell is sufficient for down-regulation of tumor immunosurveillance. J Exp Med (2005) 202:1627–33. doi:10.1084/jem.20051381

153. Berzofsky JA, Terabe M. NKT cells in tumor immunity: opposing subsets define a new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol (2008) 180:3627–35. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3627

154. Berzofsky JA, Terabe M. The contrasting roles of NKT cells in tumor immunity. Curr Mol Med (2009) 9:667–72. doi:10.2174/156652409788970706

155. Halder RC, Aguilera C, Maricic I, Kumar V. Type II NKT cell-mediated anergy induction in type I NKT cells prevents inflammatory liver disease. J Clin Invest (2007) 117:2302–12. doi:10.1172/JCI31602

156. Mistry PK, Taddei T, Vom Dahl S, Rosenbloom BE. Gaucher disease and malignancy: a model for cancer pathogenesis in an inborn error of metabolism. Crit Rev Oncog (2013) 18:235–46. doi:10.1615/CritRevOncog.2013006145

157. Nair S, Branagan AR, Liu J, Boddupalli CS, Mistry PK, Dhodapkar MV. Clonal immunoglobulin against lysolipids in the origin of myeloma. N Engl J Med (2016) 374:555–61. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1508808

158. Bjordahl RL, Gapin L, Marrack P, Refaeli Y. iNKT cells suppress the CD8+ T cell response to a murine Burkitt’s-like B cell lymphoma. PLoS One (2012) 7:e42635. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042635

159. Renukaradhya GJ, Sriram V, Du W, Gervay-Hague J, Van Kaer L, Brutkiewicz RR. Inhibition of antitumor immunity by invariant natural killer T cells in a T-cell lymphoma model in vivo. Int J Cancer (2006) 118:3045–53. doi:10.1002/ijc.21764

160. Yang W, Li H, Mayhew E, Mellon J, Chen PW, Niederkorn JY. NKT cell exacerbation of liver metastases arising from melanomas transplanted into either the eyes or spleens of mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2011) 52:3094–102. doi:10.1167/iovs.10-7067

161. Pilones KA, Kawashima N, Yang AM, Babb JS, Formenti SC, Demaria S. Invariant natural killer T cells regulate breast cancer response to radiation and CTLA-4 blockade. Clin Cancer Res (2009) 15:597–606. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1277

162. Zhao J, Bagchi S, Wang CR. Type II natural killer T cells foster the antitumor activity of CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides. Oncoimmunology (2014) 3:e28977. doi:10.4161/onci.28977

163. Exley MA, Lynch L, Varghese B, Nowak M, Alatrakchi N, Balk SP. Developing understanding of the roles of CD1d-restricted T cell subsets in cancer: reversing tumor-induced defects. Clin Immunol (2011) 140:184–95. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2011.04.017

164. Molling JW, Langius JA, Langendijk JA, Leemans CR, Bontkes HJ, Van Der Vliet HJ, et al. Low levels of circulating invariant natural killer T cells predict poor clinical outcome in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol (2007) 25:862–8. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5787

165. Motohashi S, Okamoto Y, Yoshino I, Nakayama T. Anti-tumor immune responses induced by iNKT cell-based immunotherapy for lung cancer and head and neck cancer. Clin Immunol (2011) 140:167–76. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2011.01.009

166. Najera Chuc AE, Cervantes LA, Retiguin FP, Ojeda JV, Maldonado ER. Low number of invariant NKT cells is associated with poor survival in acute myeloid leukemia. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (2012) 138:1427–32. doi:10.1007/s00432-012-1251-x

167. Shaulov A, Yue S, Wang R, Joyce RM, Balk SP, Kim HT, et al. Peripheral blood progenitor cell product contains Th1-biased noninvariant CD1d-reactive natural killer T cells: implications for posttransplant survival. Exp Hematol (2008) 36:464–72. doi:10.1016/j.exphem.2007.12.010

168. Cui J, Shin T, Kawano T, Sato H, Kondo E, Toura I, et al. Requirement for Valpha14 NKT cells in IL-12-mediated rejection of tumors. Science (1997) 278:1623–6. doi:10.1126/science.278.5343.1623

169. Nakagawa R, Motoki K, Ueno H, Iijima R, Nakamura H, Kobayashi E, et al. Treatment of hepatic metastasis of the colon26 adenocarcinoma with an alpha-galactosylceramide, KRN7000. Cancer Res (1998) 58:1202–7.

170. Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Sato H, et al. Natural killer-like nonspecific tumor cell lysis mediated by specific ligand-activated Valpha14 NKT cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1998) 95:5690–3. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.10.5690

171. Fuji N, Ueda Y, Fujiwara H, Toh T, Yoshimura T, Yamagishi H. Antitumor effect of alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) on spontaneous hepatic metastases requires endogenous interleukin 12 in the liver. Clin Cancer Res (2000) 6:3380–7.

172. Silk JD, Hermans IF, Gileadi U, Chong TW, Shepherd D, Salio M, et al. Utilizing the adjuvant properties of CD1d-dependent NK T cells in T cell-mediated immunotherapy. J Clin Invest (2004) 114:1800–11. doi:10.1172/JCI200422046

173. Nishimura T, Watanabe K, Yahata T, Ushaku L, Ando K, Kimura M, et al. Application of interleukin 12 to antitumor cytokine and gene therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol (1996) 38(Suppl):S27–34. doi:10.1007/s002800051033

174. Nakui M, Ohta A, Sekimoto M, Sato M, Iwakabe K, Yahata T, et al. Potentiation of antitumor effect of NKT cell ligand, alpha-galactosylceramide by combination with IL-12 on lung metastasis of malignant melanoma cells. Clin Exp Metastasis (2000) 18:147–53. doi:10.1023/A:1006715221088

175. Hayakawa Y, Takeda K, Yagita H, Smyth MJ, Van Kaer L, Okumura K, et al. IFN-gamma-mediated inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by natural killer T-cell ligand, alpha-galactosylceramide. Blood (2002) 100:1728–33.

176. Hayakawa Y, Rovero S, Forni G, Smyth MJ. Alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) suppression of chemical- and oncogene-dependent carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2003) 100:9464–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1630663100

177. Li J, Sun W, Subrahmanyam PB, Page C, Younger KM, Tiper IV, et al. NKT cell responses to B cell lymphoma. Med Sci (Basel) (2014) 2:82–97. doi:10.3390/medsci2020082

178. Nur H, Rao L, Frassanito MA, De Raeve H, Ribatti D, Mfopou JK, et al. Stimulation of invariant natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide activates the JAK-STAT pathway in endothelial cells and reduces angiogenesis in the 5T33 multiple myeloma model. Br J Haematol (2014) 167:651–63. doi:10.1111/bjh.13092

179. Kim D, Hung CF, Wu TC, Park YM. DNA vaccine with alpha-galactosylceramide at prime phase enhances anti-tumor immunity after boosting with antigen-expressing dendritic cells. Vaccine (2010) 28:7297–305. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.079

180. Toura I, Kawano T, Akutsu Y, Nakayama T, Ochiai T, Taniguchi M. Cutting edge: inhibition of experimental tumor metastasis by dendritic cells pulsed with alpha-galactosylceramide. J Immunol (1999) 163:2387–91.