95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Immunol. , 14 April 2015

Sec. Inflammation

Volume 6 - 2015 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00150

This article is part of the Research Topic Interaction between hyaluronic acid and its receptors (CD44, RHAMM) regulates the activity of inflammation and cancer View all 19 articles

Hyaluronan is made and extruded from cells to form a pericellular or extracellular matrix (ECM) and is present in virtually all tissues in the body. The size and form of hyaluronan present in tissues are indicative of a healthy or inflamed tissue, and the interactions of hyaluronan with immune cells can influence their response. Thus, in order to understand how inflammation is regulated, it is necessary to understand these interactions and their consequences. Although there is a large turnover of hyaluronan in our bodies, the large molecular mass form of hyaluronan predominates in healthy tissues. Upon tissue damage and/or infection, the ECM and hyaluronan are broken down and an inflammatory response ensues. As inflammation is resolved, the ECM is restored, and high molecular mass hyaluronan predominates again. Immune cells encounter hyaluronan in the tissues and lymphoid organs and respond differently to high and low molecular mass forms. Immune cells differ in their ability to bind hyaluronan and this can vary with the cell type and their activation state. For example, peritoneal macrophages do not bind soluble hyaluronan but can be induced to bind after exposure to inflammatory stimuli. Likewise, naïve T cells, which typically express low levels of the hyaluronan receptor, CD44, do not bind hyaluronan until they undergo antigen-stimulated T cell proliferation and upregulate CD44. Despite substantial knowledge of where and when immune cells bind hyaluronan, why immune cells bind hyaluronan remains a major outstanding question. Here, we review what is currently known about the interactions of hyaluronan with immune cells in both healthy and inflamed tissues and discuss how hyaluronan binding by immune cells influences the inflammatory response.

The function of our immune cells is to maintain homeostasis. When immune cells detect damage or infection, they respond by making an inflammatory response that is aimed at removing the threat. The ultimate goal is to repair the damage and return the tissue to its original state. The inflammatory process is a potent, fundamental, and normally protective immune mechanism. However, if it is not properly regulated, it can result in serious damage to the host and lead to a pathological state. In fact, inflammation is thought to be at the root of many chronic conditions, from heart attacks and strokes to arthritis and type-2 diabetes. Thus, it is important to understand the factors that drive and resolve inflammation in order to better treat inflammatory diseases and identify novel therapeutic targets and new predictors of treatment efficacy.

Our skin and mucosal surfaces provide the first line of defense, and any pathogen that breaches these barriers activates innate immune cells, which trigger an inflammatory response. Macrophages are innate immune cells that reside in our tissues and play a key role in maintaining tissue homeostasis. Their primary role is to remove dead and damaged cells, and to detect and destroy invading pathogens. Dendritic cells are also innate immune cells that become activated in response to pathogens and migrate to the lymph node to activate antigen-specific adaptive immune cells (T and B lymphocytes). Once the pathogen and cell debris are removed, damaged cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) components are replaced, and tissue homeostasis is restored. One major constituent of the ECM is hyaluronan (HA), a large glycosaminoglycan under physiological conditions that becomes fragmented during infection and tissue damage, and is restored upon the resolution of inflammation. HA turnover is perturbed during inflammation and HA fragments accumulate extracellularly. These fragments are associated with propagating the inflammatory response, whereas full-length high molecular mass HA is associated with the resolution of inflammation. While all immune cells express the HA receptor, CD44, not many bind HA under homeostatic conditions. However, this changes when immune cells become activated. In this review, we discuss what is known about the interactions between immune cells and HA during homeostasis and inflammation.

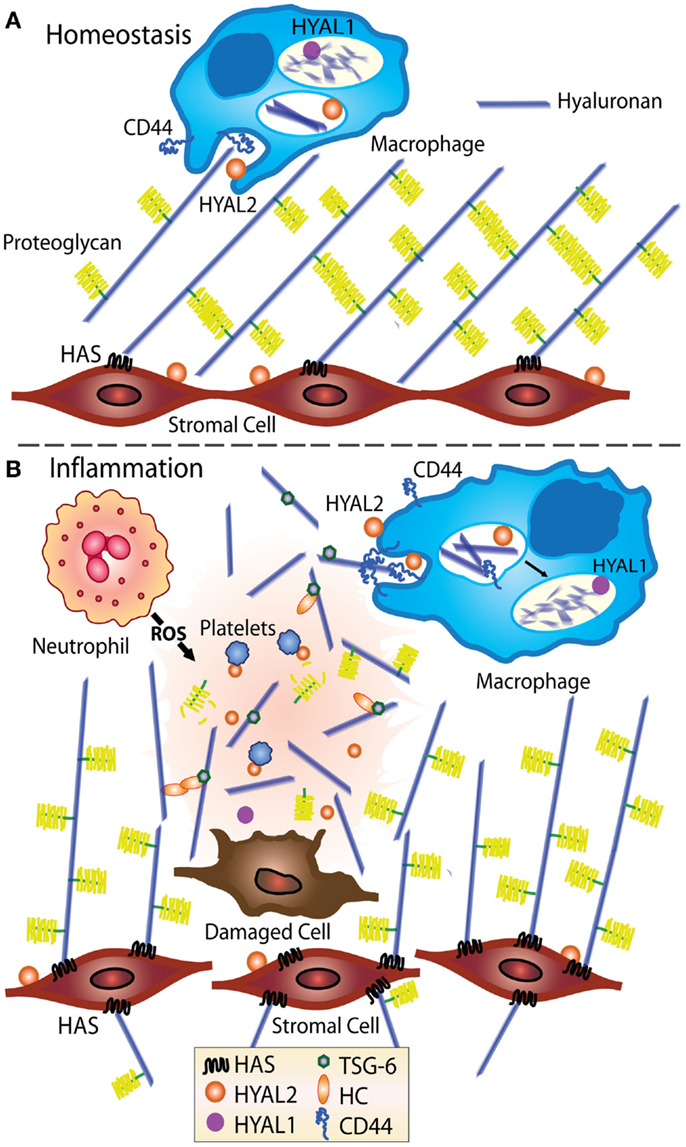

HA is widely distributed throughout all the tissues in the body with up to 50% being present in the skin. HA is found at high levels in the umbilical cord (~4 mg/ml) and synovial fluid (~2 mg/ml); it is prevalent in the vitreous of the eye (~100–400 μg/g of wet tissues) and the dermis of the skin (~500 μg/g wet tissue); and present at 10–100 ng/ml in the blood (1, 2). It is hygroscopic in nature and has viscoelastic properties making it a useful lubricant in joints. HA comprises repeating units of d-N-acetyl glucosamine and d-glucuronic acid. HA is often confined to specific areas within tissues, for example, HA is present around blood vessels and bronchioles in the lung (3). At homeostasis, HA production is balanced by its cellular uptake and degradation (4). Cellular HA synthases (HAS 1–3) and hyaluronidases (Hyal 1–3) mediate the turnover of HA [reviewed in more detail elsewhere (5–11)]. HA catabolism can occur locally by nearby cells involving CD44-mediated uptake, partial degradation by Hyal 2, and further degradation in the lysosome by Hyal 1 [(12, 13); see Figure 1]. Alternatively, HA can drain into the lymphatics and be degraded at a distant site such as the liver (2).

Figure 1. Model showing HA turnover at homeostasis and during inflammation. At homeostasis (A), stromal cells produce ECM, including HA, which becomes decorated with proteoglycans such as versican (14–16), indicated by the yellow brush structures. HA is turned over in tissues, likely by CD44-mediated cellular uptake by fibroblasts and macrophages (17), then degraded by Hyal 1 and 2 (12, 13). (B) During inflammation, the levels of HA increase and the ECM becomes susceptible to damage and fragmentation (18–20). Inflammation induced HA binding proteins such as TSG-6 bind and crosslink itself or the heavy chain of IαI (HC) to HA (21, 22) and in some situations such as chronic inflammation, HA deposits may develop (3, 18). CD44-mediated uptake of HA fragments by macrophages is thought to play an important role in resolving inflammation (19).

During inflammation, an increase in HA is accompanied by a decrease in chain length, possibly due to altered HAS and Hyal activities (3, 18) or to cleavage by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species produced by activated immune cells (23, 24). Macrophages are thought to be involved in HA uptake and the removal of HA fragments (19), and stromal cells are a major source of newly synthesized HA, see Figure 1. Upon the resolution of inflammation, HA production and cellular turnover return to normal and the high molecular mass form predominates again.

Hyaluronan is secreted from the cell and forms pericellular or extracellular matrices presumably after cleavage and release from the cell surface. HA is a major component of the ECM and at homeostasis, extracellular HA is found predominantly in its high molecular mass form of over 1000 kDa (10, 25, 26). HA chains occupy a large hydrodynamic volume in solution (27) and can associate with collagen in extracellular matrices. Proteoglycans such as versican and aggrecan bind to HA and this could create a stable network under homeostatic conditions (14–16).

Both damage and inflammatory conditions can cause the fragmentation of HA, which is considered fragmented when its molecular mass falls below 500 kDa. Studies in the lung tissue have reported the detection of 500 kDa HA fragments after bleomycin-induced inflammation (19), 70 kDa fragments after cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (18), and 100–200 kDa fragments in the bronchial alveolar lavage fluid (BALF) after ozone-induced airway hyper-responsiveness (20). There is evidence that HA fragmentation can result from degradation by reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are produced by neutrophils (23, 24), or by enzymatic cleavage by Hyal 1 or 2 that perhaps have escaped from dying cells. Hyal 2 and Hyal 1 both work optimally at acidic pH and break down HA to 20 kDa and small oligomers, respectively (28). Alternatively, an increase in HA fragments may be the result of HA synthases making smaller chains of HA (3, 18).

Under normal conditions, small oligomers of HA should only be present in the lysosome as HA is degraded into tetrasaccharides by Hyal 1. Hyal 1 has been reported in the serum, but neither the source nor its activity is known (28). Thus, one can predict that the smallest oligomers of HA would only be present under severe inflammatory conditions when there is significant cell death and release of the lysosomal contents. It is these smaller oligomers that are thought to activate dendritic cells (29, 30). As CD44 binds to these oligomers with very low avidity, they may activate dendritic cells by interacting with other receptors such as TLR2 or 4, although this remains to be shown directly.

In vitro, pericellular cable-like structures of HA can be induced in cells in response to inflammatory stimuli such as polyI:C, a viral RNA mimic (31, 32), or to tunicamycin, an ER stress and N-glycosylation inhibitor (33). These HA cables are also positive for the inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor (IαI) (32). The heavy chains (HC or serum HA-associated protein, SHAP) of IαI can become covalently bound to HA and this is thought to crosslink and stabilize HA (34). The human monocytic cell line U937 and human peripheral blood mononuclear leukocytes, which do not bind soluble HA, can bind to these cables (31, 32, 35), although only at 4°C as at 37°C the HA is taken up by the U937 cells. (36). HA cables have been induced in a variety of cell types in vitro, including smooth muscle cells from the lung (37) and colon (32), in airway (38) and renal epithelial cells (39), as well as epidermal keratinocytes (40). However, HA cables have yet to be described in vivo, although HA and IαI co-staining has been reported in a human case of inflammatory bowel disease (32).

TNFα-stimulated gene-6 protein (TSG-6) is a multifunctional protein that has a HA binding module and binds HA under acidic conditions (41). TSG-6 production is greatly increased with inflammation and is associated with tissue remodeling (41). TSG-6 is the enzyme that catalyzes the covalent addition of the HC from IαI to HA (21, 22, 42), which can lead to the crosslinking and aggregation of HA (34). Interestingly, TSG-6 and the attachment of the HC from IαI enhance the binding of HA to CD44 (43, 44). Furthermore, these HA–HC complexes are found as HA deposits in vivo during persistent inflammation in the lung and TSG-6 has been shown to promote these deposits (3, 45). However, the function of these HA–HC complexes in inflammation and tissue remodeling is still being explored.

Under homeostatic conditions, without infection or inflammation, the majority of developing and mature immune cells do not bind HA, as assessed by flow cytometry using fluoresceinated HA (Fl-HA, see Box 1). In fact, alveolar macrophages are the only immune cells that have been shown to bind high levels of HA under homeostatic, non-inflammatory conditions, in both rodents and humans [(46–48); see Table 1]. Alveolar macrophages reside in the respiratory tract and alveolar space, between the epithelial layer and surfactant, where they are responsible for the uptake and clearance of pathogens and debris. In the absence of these macrophages, the immune response is exacerbated (49), indicating that these scavenger cells also have a role in limiting inflammation, perhaps by clearing debris and removing inflammatory stimuli. Alveolar macrophages take up HA in a CD44-dependent manner, which is then delivered to the lysosomes and subsequently degraded (17). HA is present in the connective tissue space during lung development, but is reduced as the number of CD44-positive macrophages increases (50). Fetal alveolar type II pneumocytes produce HA (51), which is thought to associate with the pulmonary surfactant. However, in adults, it is less clear if mature pneumocytes make HA and most of the HA in the lung tissue is found lining blood vessels and bronchioles (3, 50). There seems to be two possible explanations why alveolar macrophages constitutively bind HA: (1) to bind to the HA producing pneumocytes to help anchor themselves in the alveolar space or (2) to internalize HA or HA fragments and help keep the alveolar space free of debris.

Box 1. Evaluation of HA binding by flow cytometry.

Hyaluronan from rooster comb (1000–1500 kDa) or commercially available HA of specific molecular mass is conjugated to fluorescent dyes, using the method of de Belder (52), or indirectly using a coupling reagent. Fluoresceinated HA (Fl-HA) used in flow cytometry provides a useful means to evaluate surface HA binding, HA uptake, and CD44-specific HA binding using HA-blocking CD44 mAbs such as KM81 or KM201 (53). To date, all experiments indicate that the HA binding on immune cells is mediated by CD44 [(54, 55), and reviewed in Ref. (56, 57)].

High molecular mass HA (>1000 kDa) binds to CD44 with a higher avidity than medium (~200 kDa) or low (<20 kDa) molecular mass HA fragments, and thus high molecular mass Fl-HA is routinely used to evaluate HA binding by immune cells. CD44 can bind monovalently to 6–18 sugars of HA, with a noticeable increase in avidity when the HA reaches 20–38 sugars in length, suggesting that divalent binding is occurring (58). The avidity will increase with increasing length as more CD44 molecules are engaged. Ultimately, the strength of Fl-HA binding depends on the size of HA as well as the amount, density, and type of CD44 at the cell surface. Flow cytometry allows us to determine relative HA binding abilities as it can distinguish cells that bind different amounts of Fl-HA. The pretreatment of cells with hyaluronidase (which is then washed away) can determine if CD44 is binding to endogenous HA and thus blocking the binding of Fl-HA. It is thus a useful technique to gain insights into the HA binding abilities of CD44. Commercial sources now provide specific molecular sizes of purified soluble HA that are low in contaminants and endotoxin. However, it is important to keep in mind that purified soluble chains of HA may not always be the form encountered in vivo.

There is very little direct evidence that immature or mature dendritic cells bind HA, HA fragments, or oligomers of HA, despite reports that HA fragments and small oligomers of HA stimulate dendritic cells to produce proinflammatory cytokines (29, 30, 74). Dendritic cells have been reported to express HA and HA-synthesizing and degrading enzymes (75), with human monocyte-derived dendritic cells expressing primarily HAS 3 (76). However, it is not clear whether CD44 on either immature or activated dendritic cells is capable of interacting with HA. Unlike macrophages, which stay in the tissues to fight infection and maintain homeostasis, activated dendritic cells migrate to the draining lymph node, where they present antigen to naïve T cells. A HA binding peptide, Pep-1, reduced dendritic cell clusters and antigen-induced T cell proliferation, however, Pep-1 acted on the T cells, suggesting that T cells make HA (75). Non-endotoxin tested HA upregulated costimulatory molecule expression on bone marrow-derived dendritic cells, which facilitated T cell proliferation, while CD44 on the T cells promoted clustering with the dendritic cells (74). However, since endotoxin is a common contaminant in some HA preparations and can have similar effects on dendritic cells, additional steps are needed to exclude an endotoxin effect. Supernatants from Th1 clones also promoted HA-dependent adhesion between human monocyte-derived dendritic cells and activated T cells or Th1 or Th2 clones, providing evidence for a dendritic cell-HA:CD44-T cell interaction (76). However, as we discuss below, naïve T cells express low levels of CD44 and have a low avidity for HA, making this mechanism unlikely to play a key role in the initial contact and activation of naïve T cells, unless dendritic cells produce a form of HA that enables naive T cells to bind. It could, however, play a role in activating memory T cells, which express higher levels of CD44 and have a greater propensity to bind HA (54).

Activated dendritic cells present antigen to naive T cells, which stimulates their activation, proliferation, and differentiation into effector T cells. Early studies showed that CD44 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) could provide a costimulatory signal that together with a signal from the T cell receptor (TCR) activates T cells (77–79). As CD44 is present in lipid rafts along with the tyrosine kinase Lck (80), its crosslinking was thought to help Lck activation and bring it into contact with the TCR signaling complex (81). Although these antibodies crosslink CD44 and enhance TCR signaling, there is limited evidence that HA can do this, perhaps because naïve T cells have a very low avidity for HA. Data from naïve T cells isolated from C57Bl/6 mice show that naïve T cells express low levels of CD44 and do not bind Fl-HA (54, 55, 68). However, one study showed that immobilized HA could augment PMA or CD3-induced proliferation of human peripheral blood T lymphocytes and could augment IL-2 production from CD3-stimulated CD4 T cell clones (82). In this study, HA binding did not become apparent until 1–2 days after stimulation.

Activation of immune cells by proinflammatory cytokines, inflammatory stimuli, and by antigen recognition can all induce HA binding by CD44 [reviewed in Ref. (56); see Table 1]. HA binding in response to these stimuli is generally accompanied by an increase in CD44 expression and typically takes 2–3 days to reach maximal HA binding levels. Flow cytometry can indicate a shift in HA binding or identify a specific subset of binding cells (see Box 1 for more details). Table 1 shows the stimuli that induce HA binding in the various immune cells. Although neutrophils are major inflammatory phagocytic cells, these cells do not bind Fl-HA and are normally recruited to inflammatory sites independently of CD44 (83). However, as we discuss later, HC-modified HA provides a means of neutrophil recruitment to inflamed liver (71). Below, we will focus on the HA binding abilities of monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and T cells during inflammation.

Human monocytes in the blood bind negligible amounts of soluble Fl-HA (59–61), but are induced to bind over a period of 2–3 days when activated in vitro by inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1β, and the inflammatory agent, LPS (see Table 1). Similarly, M-CSF-induced mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages and ex vivo peritoneal macrophages do not bind Fl-HA until induced by proinflammatory agents (62). Treatment of TNFα-induced human monocytes with IL-4 prevents the induction of HA binding (60), whereas IL-4 treatment alone induced HA binding on mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (62). Both the transcription and post-translational modifications of CD44, such as glycosaminoglycan or carbohydrate addition, can influence HA binding. Decreases in sialylation and changes in the chondroitin sulfate modification to CD44 can modulate HA binding by human monocytes (84) and mouse macrophages, respectively (62). Macrophages are found in many locations in the body, with resident populations in the spleen, liver, skin, gut, lung and the alveolar space, brain, and the peritoneum, but only the alveolar macrophages bind substantial amounts of HA under homeostatic conditions. This suggests that the environment of the macrophage influences its ability to interact with HA, and raises the possibility that these macrophages may be induced to bind HA when the environment or cytokine milieu changes upon infection or inflammation.

Why inflammation induces HA binding on monocytes and macrophages is not well understood. Possible explanations include: (1) activated monocytes and macrophages use HA as a substrate to aid in migration toward the site of infection; (2) an enhanced ability to bind HA or HA–HC complexes to retain activated immune cells in the tissue at sites of inflammation; (3) an enhanced ability to bind, take up, and degrade HA, HA fragments, or HA–HC complexes via CD44, thereby helping reduce inflammation and promote tissue repair; (4) HA binding provides a supportive environment for these cells, either by providing a direct survival signal to the cell or by creating a cytokine-rich environment that aids in their survival, proliferation, or function.

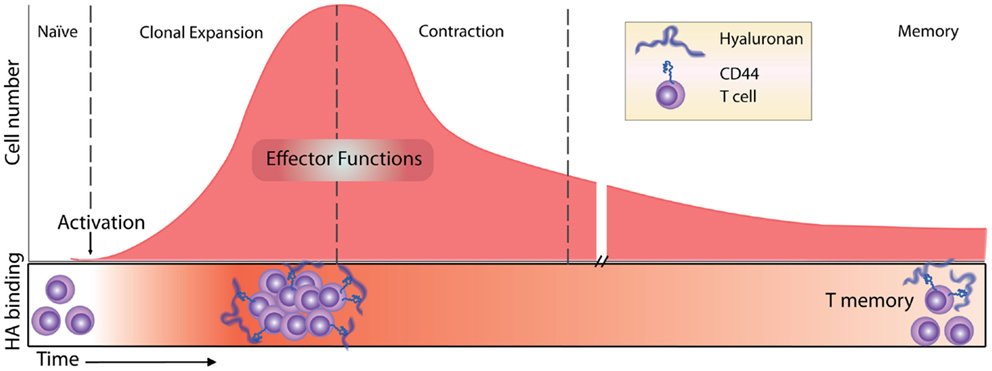

In contrast to unstimulated naïve T cells, antigen-induced activation of T cells induces HA binding, coincident with an increase in CD44 expression, and this is now well-established both in vitro and in vivo [(54, 55, 68); see Figure 2]. In vitro, the induction of HA binding is transient, peaking at 2–3 days, whereas it is more sustained in vivo, reaching its maximum around 5–8 days (54, 55). The absence of any significant Fl-HA binding on naïve T cells until 2–3 days, after at least the first division, also argues against a model where HA on dendritic cells facilitates CD44-mediated naïve T cell adhesion and the initiation of T cell activation. As T cell activation and proliferation proceeds, HA binding increases, as does the ability of T cells to roll under flow on a HA substrate (85) and the ability of superantigen-activated T cells to extravasate to the inflamed peritoneum in an HA-dependent manner (86). Thus, one function of the upregulation of HA binding by activated T cells may be to guide the effector T cell to the site of infection. This later induction of HA binding after activation and some proliferation suggests a role beyond the initial contact and activation step. Notably, the strength of the signal received by the T cell dictates the level and percentage of T cells that are induced to bind HA, with cells binding the most HA being the most proliferative (54). Despite these correlations, no evidence was found to support HA-stimulated proliferation. However, in another study focusing on CD4+ CD25+ T cells, HA was found to stimulate IL-2 production and sustain FoxP3 expression (87). 4-methylumbelliferone, a compound that can inhibit HA synthesis (88, and also see article in this research topic), prevented T cell proliferation and IL-2 production, suggesting that HA synthesis by the T cell itself is important for this effect (89). Thus, there is some evidence that HA production and/or the binding of high molecular mass HA on activated T cells may enhance IL-2 production, which may either prolong T cell proliferation or, if acting on regulatory T cells (Tregs), may limit T cell activation. The outcome of an interaction of activated T cells with high molecular mass HA may also depend on the differentiation state of the T cell, as re-activated T cells exposed to high molecular mass HA undergo a rapid form of activation-induced cell death, as observed in human Jurkat T cells and a subpopulation of splenic T cells from mice (90).

Figure 2. Timeline of the T cell response and HA binding. Before immune challenge, naïve T cells express low levels of CD44 and have low affinity/avidity for HA (55). Following activation, HA binding is induced (55, 68) and marks the most proliferative, activated T cells (54). HA binding on effector T cells has a role in T cell extravasation into inflamed peritoneum (68), and marks the majority of cytotoxic CD8 T cells (55). Contraction and generation of memory CD8 T cells result in memory cells that maintain high levels of expression of CD44 but only a percentage of them (approximately 30%) bind HA (54).

After naïve T cell activation and proliferation, CD4 T cells differentiate into various effector T cells (Th1, Th2, Th17, Tregs), and CD8 T cells become cytotoxic effector cells. Both CD4 and CD8 effector cells leave the lymph node and migrate to the infected tissue to fight the infection. After the initial induction of HA binding during the proliferative phase, it is less clear how long these cells retain their HA binding abilities. In vitro evidence indicates that after antigen-induced HA binding in 50% of ovalbumin- (Ova-) specific OT-I CD8 T cells 2 days post activation, only 6% retain HA binding at day 6 (54). In vivo, antigen-induced HA binding peaks 5 days post infection, marking approximately 50% of the OT-I CD8 T cells, and this drops to 14% by day 10, indicating that HA binding is more sustained in vivo although it also declines after the peak of the proliferative phase (54). In other mouse studies, the percent of HA binding cells peaked at day 7–8 and the HA-positive population contained the majority of the cytotoxic CD8 T effector cells (55), consistent with the HA-negative cells being naïve cells. However, since both soluble HA and HA-blocking CD44 mAbs had no effect on allogeneic killing, HA binding was not implicated in the killing function of these cells (55). After the peak of the response, many effector T cells undergo apoptosis during the contraction phase and only long-lived memory cells remain. Following Listeria-Ova infection and the development of T memory cells in vivo, about 30% of the Ova-specific OT-I CD8 memory T cells in the bone marrow and spleen bind Fl-HA 30 days after infection [(54); see Figure 2].

CD4 T cells differentiated in vitro to become either Th1 or Th2 bind slightly higher levels of Fl-HA than naïve T cells, with Th2 cells binding slightly more than Th1, but the binding is still at a very low level (91, 92). Nevertheless, this low-level binding is sufficient to allow them to roll and adhere on TNFα-inflamed endothelium in vivo (91). In another study, CD44 promoted T effector cell survival from Fas-mediated contraction, and was required for the formation of Th1 memory cells, but the effect of HA was not examined (93). Thus HA binding by effector T cells may assist in their recruitment to inflammatory sites and the interaction of HA with CD44 in the tissues may provide a survival signal for the effector T cell.

Tregs express CD4 and CD25, as do activated CD4 T cells, and so are further characterized by expression of the transcription factor, FoxP3 (94). Firan and colleagues activated CD4+CD25+ T cells isolated from BalbC mice, separated them into HA binding and non-binding populations, and found that the HA binding fraction was functionally more suppressive (69). The activation of human peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ T cells induced a subpopulation to bind HA and this correlated with the highest expression of CD44 and FoxP3 (70). The addition of 20 μg/ml of high molecular mass HA (1.5 × 106 Da) maintained FoxP3 expression under limiting levels of IL-2, and enhanced their suppressive ability in vitro. At a higher concentration (100 μg/ml), HA directly reduced CD4 T cell proliferation (70). Both high molecular mass HA and the crosslinking of CD44 provided a costimulatory signal that augmented IL-2, FoxP3 expression, and IL-10 production in the human CD4+ CD25+ T cell population (87). Furthermore, HA or CD44 crosslinking activated p38 and ERK1/2-dependent pathways that induced IL-10 producing regulatory T cells (TR1) from FoxP3-negative cells (95). Together, this suggests a role for high molecular mass HA in limiting T cell proliferation either indirectly via supporting Tregs or directly when given in higher amounts to CD4 T cells.

It is clear from the above sections that HA binding by T cells is not restricted to activated Tregs, suggesting a more general function for HA binding in activated CD4 and CD8 T cells. Since HA binding labels the most proliferative, functionally active T cells, HA may exert its effect by aiding in the production of IL-2 under limiting conditions. Alternatively, perhaps HA localizes activated T cells to a specific area in the lymph node, where they have optimal access to cytokines and growth factors, or maybe HA binding itself provides a survival signal for activated T cells.

Previous reviews have discussed HA binding by immune cells (56, 85), and have detailed what is known regarding the role of HA (96) and CD44 in inflammation and inflammatory diseases (57, 97, 98). Many diseases involve an inflammatory component and it has become apparent that HA levels are increased in many tissues upon inflammation. Here, we describe the effects of HA interactions with immune cells during inflammation with a particular focus on lung inflammation.

At the first signs of damage or infection in a tissue, ensuing danger signals are received by macrophages that induce the secretion of inflammatory stimuli such as TNFα and IL-1β, which act on the endothelium in the microvasculature. This leads to the upregulation of adhesion molecules that facilitate leukocyte recruitment to the inflamed tissue. HA is one adhesion molecule that is upregulated on microvascular endothelial cell lines (99). Under flow conditions, T cells can roll on HA via CD44 both in vitro (100, 101) and in vivo (91), implying that the upregulation of HA on activated endothelial cells will facilitate T cell recruitment to inflamed tissues. Indeed, a CD44-mediated interaction with HA is important for T cell extravasation into the peritoneum in a model of superantigen-driven T cell activation and inflammation (86). However, given the well-established roles of the selectin molecules in leukocyte recruitment (102), the CD44–HA interaction may provide an additional and possibly redundant mechanism to facilitate T cell extravasation. The fact that the majority of CD44-deficient leukocytes still reach inflammatory sites (57) supports this idea.

CD44- and HA-dependent rolling on endothelium is not a factor for neutrophil recruitment to inflammatory sites (83). However, CD44-mediated adhesion to HA is a key factor in neutrophil adhesion to inflamed liver sinusoids in endotoxemic mice (71). Leukocyte recruitment to liver sinusoids proceeds in the absence of rolling and involves both integrin- and CD44-dependent mechanisms (103). LPS recognition by liver endothelial cells induces the deposition of HC (SHAP) on HA that is constitutively expressed by the liver sinusoids, and this leads to CD44-dependent adhesion of neutrophils to HA (71, 104, and also see article in this research topic).

In experimental pulmonary eosinophilia that is induced by administration of Ascaris suum extract, HA-blocking CD44 antibodies prevented lymphocyte and eosinophil recruitment into the BALF (105). A follow-up study using CD44-deficient mice and the house dust mite allergen concluded that the loss of CD44 affected Th2, but not Th1 recruitment to the BALF (92). This suggests that HA and CD44 play a role in the recruitment of eosinophils and Th2 cells in an allergic response in the lung.

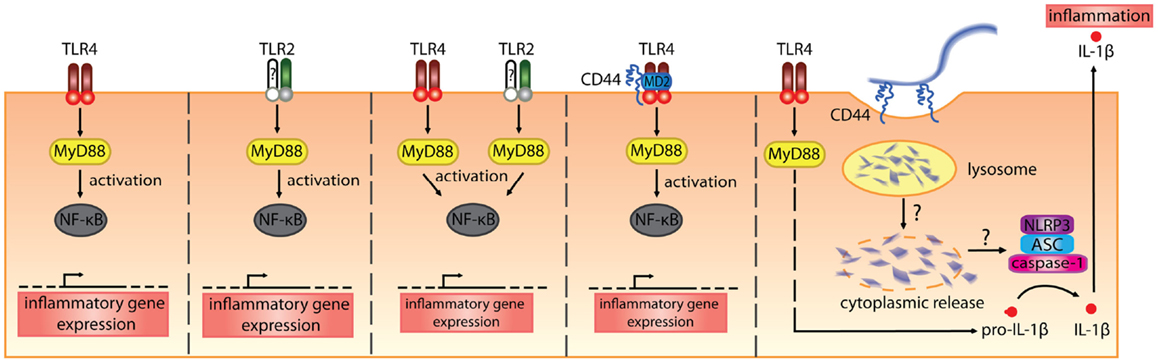

In vitro. Hyaluronan fragments were first reported to stimulate chemokine and proinflammatory cytokine expression and NFkB-mediated iNOS expression in macrophage cell lines in the 1990s (106–109). At first, it was thought that CD44 mediated the effect of these HA fragments, which were quite large (470, 200–280 kDa), but later studies began to implicate the toll-like receptors, TLR2 and/or TLR4 (Table 2; Figure 3). While CD44 can bind HA fragments on activated cells, it is not clear if this alone leads to proinflammatory cytokine secretion. Instead, TLR4 (110), TLR2 (111), TLR2 and TLR4 (112), a complex of CD44 and TLR4 (113), or a combination of TLR4, CD44 and activation of the NLRP3-mediated inflammasome (114) have all been implicated in mediating HA fragment-induced proinflammatory signals (see Figure 3). TLR4 was required for HA oligomers to initiate dendritic cell maturation and proinflammatory cytokine production from both human and mouse in vitro-derived dendritic cells (29, 30) and 200 kDa HA fragments stimulated dendritic cell maturation in a CD44-independent manner (74). However, whether HA fragments can directly activate TLRs remains uncertain, as contaminants such as LPS can produce similar results and the direct binding of HA to TLRs has not yet been demonstrated. This needs to be determined to establish HA as a bone fide TLR ligand.

Figure 3. The various receptors implicated in mediating the proinflammatory signals induced by HA fragments. From the left, HA fragments ranging from 500 kDa and below have been reported to stimulate proinflammatory cytokine production via TLR4 alone, TLR2 alone, both TLR2 and TLR4, a complex of TLR4 involving CD44, or via TLR4- and CD44-mediated uptake that leads to inflammasome activation (110–114). In the first three panels, the TLRs signal via MyD88 to activate NF-κB and induce proinflammatory cytokine gene expression. In the fourth panel, CD44, together with TLR4 and MD-2, is needed for HA-stimulated proinflammatory cytokine production. In the fifth panel, TLR4 signals via MyD88 to produce pro-IL-1β and the uptake of HA via CD44 leads to the breakdown of HA which, through some unknown mechanism, leads to HA oligomers in the cytoplasm and these trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation. This leads to cleavage of pro-IL-1β and the generation of IL-1β (114).

In Table 2, we summarize the reported proinflammatory effects of HA and HA fragments on macrophages and dendritic cells in vitro. Proinflammatory effects have been reported with a wide range of HA fragment sizes: from HA oligomers [2–18 mers] to HA fragments ranging from 5 to 500 kDa. Interestingly, we note that HA fragments derived from rooster comb did not generally elicit proinflammatory responses whereas human umbilical cord-derived HA did. Human umbilical cord HA is not as pure as HA purified from rooster comb (some preparations are FDA approved for injection into humans), leaving open the possibility that the effects seen with human umbilical cord HA maybe due to LPS contamination. Indeed, in our hands HA from human umbilical cord but not rooster comb, tested positive for endotoxin (unpublished data). Although endotoxin levels were checked and polymyxin B was added to bind to LPS in some cases, possible residual contamination with TLR agonists remains a concern. In some cases, DNA contamination of HA was responsible for the proinflammatory activity on monocytes (119). Alternatively, there could be something different about the HA isolated from human umbilical cord as it does appear to be of a lower average molecular mass compared to rooster comb HA. Specific sizes of HA are now available from commercial sources that are purified from bacteria and certified endotoxin-free, and so it will be of interest to see if similar data are obtained with these HA preparations. Indeed, studies monitoring endotoxin levels more closely are now emerging. One report on glomerular mesangial cells shows that hyaluronidase is contaminated with LPS and suggests that HA provides a protective barrier for cells, which when cleaved exposes the TLRs (120). Others report no proinflammatory effect of endotoxin-free HA oligomers (118) or HA fragments on immune cells [(117); see Table 2]. Thus, further work with endotoxin-free HA is needed to substantiate whether HA fragments induce proinflammatory cytokine production and whether they do this by directly engaging TLRs.

In vivo. Ozone-induced airway hypersensitivity is associated with increased hyaluronan in the BALF, and CD44- and IαI-deficient mice were protected from this airway hypersensitivity implying a role for CD44 and IαI in driving the hypersensitivity (20). Interestingly, the instillation of fragmented, but not full-length HA, partially mimicked airway hyper-responsiveness (20). Ozone- and fragmented HA-induced airway hyper-responsiveness were also reduced in TLR4- and MyD88-deficient mice, leading to the conclusion that fragmented HA responses require TLR4 in vivo (121).

Using a mouse model of allergic contact dermatitis, Martin and colleagues found that inhibition of ROS and HA breakdown prevented sensitization and contact hypersensitivity (118). ROS stimulated hyaluronidase activity, which rapidly degraded HA in the epidermis, in a similar mechanism to that described in bronchial epithelial cells (122). Although this in vivo hypersensitivity reaction requires TLR2 and TLR4 (123), the authors have been unable to activate dendritic cells in vitro using commercially available HA oligomers of 2–12 sugars in length (118). These studies show that HA fragmentation occurs in vivo and is required for hypersensitivity responses, as are TLRs. If HA fragments do not act directly via the TLRs, perhaps TLRs are activated indirectly, by something that is released or produced upon their fragmentation. The involvement of IαI suggests that in vivo HA fragments may arise from HA–HC deposits and thus may contain other proteins and proteoglycans besides HA. This also raises the cautionary note that HA fragments and HA–HC complexes generated in vivo may be quite different from the purified forms of HA used in vitro studies and in Fl-HA labeling. Further work is thus needed to understand the HA-driven inflammatory mechanisms observed in vitro and in vivo.

In a mouse model of allergic asthma using Ova, a significant increase in HA deposition is observed in lung tissue (3). This was attributed to early increases in HAS 1 and HAS 2 mRNA expression and a decrease in Hyal 1 and Hyal 2 expression in the lung tissue (3). HA deposits provided sites for inflammatory cells to accumulate and supported subsequent collagen deposition (3). TSG-6 promoted HA deposition, suggesting the formation of HA–HC complexes, and eosinophilic airway inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness (45), correlating HA deposits with the eosinophilic response. Further evidence for a role of HA in allergic airway inflammation comes from the use of a HA synthesis inhibitor, 4-methylumbelliferone (88), which reduces Ova-induced eosinophil airway inflammation (124). Thus, these HA deposits may support inflammation by sequestering inflammatory cells and providing survival or other signals. Alternatively, it is possible that the presence of HA deposits may reflect an attempt to resolve the inflammation by promoting matrix deposition. More work is needed to fully understand the role of HA deposits in the inflammatory response.

The mouse bleomycin model of sterile inflammation and fibrosis has been used extensively by Noble and colleagues, and has provided key data on the role of HA and CD44 in the inflammatory process [reviewed in Ref. (97, 112)]. Bleomycin induces lung injury and necrosis that triggers an inflammatory response and subsequent wound repair mechanisms. Inflammatory monocytes and neutrophils are recruited to the damaged site, where they are activated by inflammatory signals released from the injured and necrotic tissue. These activated cells will phagocytose cell debris but will also produce anti-microbial factors such as ROS, which cause further tissue damage. HA is normally undetectable in the BALF but increases upon inflammation to approximately 2 μg/ml at the peak of the response. HA levels are also increased in the lung tissue upon inflammation, from 100 to 300 ng/mg of dry tissue. This increase is also accompanied by a decrease in molecular mass (500 kDa compared to the normal size of 1400 kDa) (19). Normally, the inflammatory response transitions to a healing response, where further neutrophil recruitment is halted, and debris and apoptotic neutrophils are scavenged by macrophages and/or inflammatory monocytes. Increased levels of TGFβ stimulate fibroblast proliferation and ECM production, which restores the tissue back to its original state. In CD44-deficient mice, the initial inflammatory phase appears normal, except for a higher accumulation of HA fragments. However, the CD44-deficient mice cannot resolve the inflammation: TGFβ activation is defective; apoptotic neutrophils are not cleared; and HA levels continue to rise in both the BALF and lung tissue (19). This points to a defect in clearance by macrophages or monocytes and a role for CD44 in this process. This defect is largely corrected by reconstitution of CD44-deficient mice with a CD44-sufficient immune system (19), further implicating CD44 on immune cells in the clearance of HA. The CD44-mediated uptake of HA and associated debris, together with CD44-assisted activation of TGFβ (125), may be sufficient to tip the balance toward the resolution phase of the inflammatory response. While a protective role for CD44 has also been observed in severe hypoxia-induced lung damage by promoting HA clearance and protecting from epithelial cell death (126), this role for CD44 in the resolution phase is not universally apparent, particularly when infections occur. This highlights potential differences between pathogenic and sterile inflammation and/or suggests that additional factors drive resolution when pathogens are encountered.

The key points to emerge from this review are:

1. Few immune cells bind HA during homeostasis (alveolar macrophages are a notable exception).

2. The form of HA (its size, association with other molecules, and its ability to form complexes) changes between homeostasis and inflammation.

3. Immune cell interactions with HA increase upon an inflammatory response. This may help recruit immune cells to the site of inflammation as well as keep cells at the site and may facilitate their survival and function.

4. CD44 is the only receptor that has been demonstrated to bind HA on immune cells. HA binding by CD44 can lead to HA uptake and its subsequent degradation. Macrophage CD44 is thought to play an important role in HA uptake and the clearance of HA fragments during lung inflammation.

5. Additional evidence is required to establish whether purified HA fragments and HA oligomers are proinflammatory and if so, what receptors do they interact with to mediate this effect.

6. There is a need to better understand the composition and structure of the HA fragments and complexes present in vivo during an inflammatory response, and to then mimic their effects in vitro.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support for their research from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-119503) and the Natural Sciences of Engineering Research Council (NSERC) to PJ. We also acknowledge financial support from NSERC, the University of British Columbia, and the Swedish Medical Research Council (Vetenskapsradet) for scholarships to SL-S, YD, and MO, respectively.

1. Hascall VC, Laurent TC. Hyaluronan: structure and physical properties. Glycoforum: Science of Hyaluronan Today. (1997). Available from: http://www.glycoforum.gr.jp/science/hyaluronan/HA01/HA01E.html

2. Fraser JR, Laurent TC, Laurent UB. Hyaluronan: its nature, distribution, functions and turnover. J Intern Med (1997) 242:27–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00170.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Cheng G, Swaidani S, Sharma M, Lauer ME, Hascall VC, Aronica MA. Hyaluronan deposition and correlation with inflammation in a murine ovalbumin model of asthma. Matrix Biol (2011) 30:126–34. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2010.12.003

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Erickson M, Stern R. Chain gangs: new aspects of hyaluronan metabolism. Biochem Res Int (2012) 2012:893947. doi:10.1155/2012/893947

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Stern R. Devising a pathway for hyaluronan catabolism: are we there yet? Glycobiology (2003) 13:105R–15R. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwg112

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Stern R, Asari AA, Sugahara KN. Hyaluronan fragments: an information-rich system. Eur J Cell Biol (2006) 85:699–715. doi:10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.05.009

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Stern R, Jedrzejas MJ. Hyaluronidases: their genomics, structures, and mechanisms of action. Chem Rev (2006) 106:818–39. doi:10.1021/cr050247k

8. Stern R, Kogan G, Jedrzejas MJ, Soltes L. The many ways to cleave hyaluronan. Biotechnol Adv (2007) 25:537–57. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.07.001

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Tammi RH, Passi AG, Rilla K, Karousou E, Vigetti D, Makkonen K, et al. Transcriptional and post-translational regulation of hyaluronan synthesis. FEBS J (2011) 278:1419–28. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08070.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Weigel PH, Deangelis PL. Hyaluronan synthases: a decade-plus of novel glycosyltransferases. J Biol Chem (2007) 282:36777–81. doi:10.1074/jbc.R700036200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Itano N. Simple structure, complex turnover regulation, and multiple roles of hyaluronan. J Biochem (2008) 144:131–7. doi:10.1093/jb/mvn046

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Harada H, Takahashi M. CD44-dependent intracellular and extracellular catabolism of hyaluronic acid by hyaluronidase-1 and -2. J Biol Chem (2007) 282:5597–607. doi:10.1074/jbc.M608358200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Stern R. Hyaluronan catabolism: a new metabolic pathway. Eur J Cell Biol (2004) 83:317–25. doi:10.1078/0171-9335-00392

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Toole BP. Hyaluronan and its binding proteins, the hyaladherins. Curr Opin Cell Biol (1990) 2:839–44. doi:10.1016/0955-0674(90)90081-O

15. Day AJ. Understanding hyaluronan protein interactions. Glycoforum: Science of Hyaluronan Today. (2001). Available from: http://www.glycoforum.gr.jp/science/hyaluronan/HA16/HA16E.html

16. Frey H, Schroeder N, Manon-Jensen T, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Biological interplay between proteoglycans and their innate immune receptors in inflammation. FEBS J (2013) 280:2165–79. doi:10.1111/febs.12145

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Culty M, Nguyen HA, Underhill CB. The hyaluronan receptor (CD44) participates in the uptake and degradation of hyaluronan. J Cell Biol (1992) 116:1055–62. doi:10.1083/jcb.116.4.1055

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Bracke KR, Dentener MA, Papakonstantinou E, Vernooy JH, Demoor T, Pauwels NS, et al. Enhanced deposition of low-molecular-weight hyaluronan in lungs of cigarette smoke-exposed mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2010) 42:753–61. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2008-0424OC

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Teder P, Vandivier RW, Jiang D, Liang J, Cohn L, Pure E, et al. Resolution of lung inflammation by CD44. Science (2002) 296:155–8. doi:10.1126/science.1069659

20. Garantziotis S, Li Z, Potts EN, Kimata K, Zhuo L, Morgan DL, et al. Hyaluronan mediates ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Biol Chem (2009) 284:11309–17. doi:10.1074/jbc.M802400200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Baranova NS, Nileback E, Haller FM, Briggs DC, Svedhem S, Day AJ, et al. The inflammation-associated protein TSG-6 cross-links hyaluronan via hyaluronan-induced TSG-6 oligomers. J Biol Chem (2011) 286:25675–86. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.247395

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Milner CM, Tongsoongnoen W, Rugg MS, Day AJ. The molecular basis of inter-alpha-inhibitor heavy chain transfer on to hyaluronan. Biochem Soc Trans (2007) 35:672–6. doi:10.1042/BST0350672

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Agren UM, Tammi RH, Tammi MI. Reactive oxygen species contribute to epidermal hyaluronan catabolism in human skin organ culture. Free Radic Biol Med (1997) 23:996–1001. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(97)00098-1

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Moseley R, Waddington RJ, Embery G. Degradation of glycosaminoglycans by reactive oxygen species derived from stimulated polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta (1997) 1362:221–31. doi:10.1016/S0925-4439(97)00083-5

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Toole BP. Hyaluronan: from extracellular glue to pericellular cue. Nat Rev Cancer (2004) 4:528–39. doi:10.1038/nrc1391

26. Dicker KT, Gurski LA, Pradhan-Bhatt S, Witt RL, Farach-Carson MC, Jia X. Hyaluronan: a simple polysaccharide with diverse biological functions. Acta Biomater (2014) 10:1558–70. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2013.12.019

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Scott J. Secondary and tertiary structures of hyaluronan in aqueous solution. Some biological consequences. Glycoforum: Science of Hyaluronan Today. (1998). Available from: http://www.glycoforum.gr.jp/science/hyaluronan/HA02/HA02E.html

28. Stern R. Update on the mammalian hyaluronidases. Glycoforum: Science of Hyaluronan Today. (2004). Available from: http://www.glycoforum.gr.jp/science/hyaluronan/HA15a/HA15aE.html

29. Termeer C, Benedix F, Sleeman J, Fieber C, Voith U, Ahrens T, et al. Oligosaccharides of hyaluronan activate dendritic cells via toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med (2002) 195:99–111. doi:10.1084/jem.20001858

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Termeer CC, Hennies J, Voith U, Ahrens T, Weiss JM, Prehm P, et al. Oligosaccharides of hyaluronan are potent activators of dendritic cells. J Immunol (2000) 165:1863–70. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1863

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

31. de La Motte CA, Hascall VC, Calabro A, Yen-Lieberman B, Strong SA. Mononuclear leukocytes preferentially bind via CD44 to hyaluronan on human intestinal mucosal smooth muscle cells after virus infection or treatment with poly(I.C). J Biol Chem (1999) 274:30747–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.43.30747

32. de la Motte CA, Hascall VC, Drazba J, Bandyopadhyay SK, Strong SA. Mononuclear leukocytes bind to specific hyaluronan structures on colon mucosal smooth muscle cells treated with polyinosinic acid:polycytidylic acid: inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor is crucial to structure and function. Am J Pathol (2003) 163:121–33. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63636-X

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Majors AK, Austin RC, de la Motte CA, Pyeritz RE, Hascall VC, Kessler SP, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces hyaluronan deposition and leukocyte adhesion. J Biol Chem (2003) 278:47223–31. doi:10.1074/jbc.M304871200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

34. Day AJ, de la Motte CA. Hyaluronan cross-linking: a protective mechanism in inflammation? Trends Immunol (2005) 26:637–43. doi:10.1016/j.it.2005.09.009

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Kessler S, Rho H, West G, Fiocchi C, Drazba J, de la Motte C. Hyaluronan (HA) deposition precedes and promotes leukocyte recruitment in intestinal inflammation. Clin Transl Sci (2008) 1:57–61. doi:10.1111/j.1752-8062.2008.00025.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Wang A, de la Motte C, Lauer M, Hascall V. Hyaluronan matrices in pathobiological processes. FEBS J (2011) 278:1412–8. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08069.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Lauer ME, Mukhopadhyay D, Fulop C, De La Motte CA, Majors AK, Hascall VC. Primary murine airway smooth muscle cells exposed to poly(I,C) or tunicamycin synthesize a leukocyte-adhesive hyaluronan matrix. J Biol Chem (2008) 284:5299–312. doi:10.1074/jbc.M807965200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Stober VP, Szczesniak C, Childress Q, Heise RL, Bortner C, Hollingsworth JW, et al. Bronchial epithelial injury in the context of alloimmunity promotes lymphocytic bronchiolitis through hyaluronan expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol (2014) 306:L1045–55. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00353.2013

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Selbi W, de la Motte CA, Hascall VC, Day AJ, Bowen T, Phillips AO. Characterization of hyaluronan cable structure and function in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Kidney Int (2006) 70:1287–95. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5001760

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Jokela TA, Lindgren A, Rilla K, Maytin E, Hascall VC, Tammi RH, et al. Induction of hyaluronan cables and monocyte adherence in epidermal keratinocytes. Connect Tissue Res (2008) 49:115–9. doi:10.1080/03008200802148439

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Milner CM, Higman VA, Day AJ. TSG-6: a pluripotent inflammatory mediator? Biochem Soc Trans (2006) 34:446–50. doi:10.1042/BST0340446

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Rugg MS, Willis AC, Mukhopadhyay D, Hascall VC, Fries E, Fulop C, et al. Characterization of complexes formed between TSG-6 and inter-alpha-inhibitor that act as intermediates in the covalent transfer of heavy chains onto hyaluronan. J Biol Chem (2005) 280:25674–86. doi:10.1074/jbc.M501332200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Lesley J, Gal I, Mahoney DJ, Cordell MR, Rugg MS, Hyman R, et al. TSG-6 modulates the interaction between hyaluronan and cell surface CD44. J Biol Chem (2004) 279:25745–54. doi:10.1074/jbc.M313319200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Zhuo L, Kanamori A, Kannagi R, Itano N, Wu J, Hamaguchi M, et al. SHAP potentiates the CD44-mediated leukocyte adhesion to the hyaluronan substratum. J Biol Chem (2006) 281:20303–14. doi:10.1074/jbc.M506703200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Swaidani S, Cheng G, Lauer ME, Sharma M, Mikecz K, Hascall VC, et al. TSG-6 protein is crucial for the development of pulmonary hyaluronan deposition, eosinophilia, and airway hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of asthma. J Biol Chem (2013) 288:412–22. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.389874

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

46. Culty M, O’Mara TE, Underhill CB, Yeager H Jr, Swartz RP. Hyaluronan receptor (CD44) expression and function in human peripheral blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages. J Leukoc Biol (1994) 56:605–11.

47. Teder P, Heldin P. Mechanism of impaired local hyaluronan turnover in bleomycin-induced lung injury in rat. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (1997) 17:376–85. doi:10.1165/ajrcmb.17.3.2698

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

48. Katoh S, Matsubara Y, Taniguchi H, Fukushima K, Mukae H, Kadota J, et al. Characterization of CD44 expressed on alveolar macrophages in patients with diffuse panbronchiolitis. Clin Exp Immunol (2001) 126:545–50. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01699.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

49. Thepen T, Van Rooijen N, Kraal G. Alveolar macrophage elimination in vivo is associated with an increase in pulmonary immune response in mice. J Exp Med (1989) 170:499–509. doi:10.1084/jem.170.2.499

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

50. Underhill CB, Nguyen HA, Shizari M, Culty M. CD44 positive macrophages take up hyaluronan during lung development. Dev Biol (1993) 155:324–36. doi:10.1006/dbio.1993.1032

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

51. Sahu SC, Tanswell AK, Lynn WS. Isolation and characterization of glycosaminoglycans secreted by human foetal lung type II pneumocytes in culture. J Cell Sci (1980) 42:183–8.

52. de Belder AN, Wik KO. Preparation and properties of fluorescein-labelled hyaluronate. Carbohydr Res (1975) 44:251–7. doi:10.1016/S0008-6215(00)84168-3

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

53. Zheng Z, Katoh S, He Q, Oritani K, Miyake K, Lesley J, et al. Monoclonal antibodies to CD44 and their influence on hyaluronan recognition. J Cell Biol (1995) 130:485–95. doi:10.1083/jcb.130.2.485

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

54. Maeshima N, Poon GF, Dosanjh M, Felberg J, Lee SS, Cross JL, et al. Hyaluronan binding identifies the most proliferative activated and memory T cells. Eur J Immunol (2011) 41:1108–19. doi:10.1002/eji.201040870

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

55. Lesley J, Howes N, Perschl A, Hyman R. Hyaluronan binding function of CD44 is transiently activated on T cells during an in vivo immune response. J Exp Med (1994) 180:383–7. doi:10.1084/jem.180.1.383

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

56. Ruffell B, Johnson P. The regulation and function of hyaluronan binding by CD44 in the immune system. Glycoforum: Science of Hyaluronan Today. (2009). Available from: http://www.glycoforum.gr.jp/science/hyaluronan/HA32/HA32E.html

57. Johnson P, Ruffell B. CD44 and its role in inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets (2009) 8:208–20. doi:10.2174/187152809788680994

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

58. Lesley J, Hascall VC, Tammi M, Hyman R. Hyaluronan binding by cell surface CD44. J Biol Chem (2000) 275:26967–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M002527200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

59. Levesque MC, Haynes BF. In vitro culture of human peripheral blood monocytes induces hyaluronan binding and up-regulates monocyte variant CD44 isoform expression. J Immunol (1996) 156:1557–65.

60. Levesque MC, Haynes BF. Cytokine induction of the ability of human monocyte CD44 to bind hyaluronan is mediated primarily by TNF-alpha and is inhibited by IL-4 and IL-13. J Immunol (1997) 159:6184–94.

61. Brown KL, Maiti A, Johnson P. Role of sulfation in CD44-mediated hyaluronan binding induced by inflammatory mediators in human CD14+ peripheral blood monocytes. J Immunol (2001) 167:5367–74. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5367

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

62. Ruffell B, Poon GF, Lee SS, Brown KL, Tjew SL, Cooper J, et al. Differential use of chondroitin sulfate to regulate hyaluronan binding by receptor CD44 in inflammatory and interleukin 4-activated macrophages. J Biol Chem (2011) 286:19179–90. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.200790

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

63. Termeer C, Johannsen H, Braun T, Renkl A, Ahrens T, Denfeld RW, et al. The role of CD44 during CD40 ligand-induced dendritic cell clustering and maturation. J Leukoc Biol (2001) 70:715–22.

64. Kryworuchko M, Diaz-Mitoma F, Kumar A. Interferon-gamma inhibits CD44-hyaluronan interactions in normal human B lymphocytes. Exp Cell Res (1999) 250:241–52. doi:10.1006/excr.1999.4524

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

65. Hathcock KS, Hirano H, Murakami S, Hodes RJ. CD44 expression on activated B cells. Differential capacity for CD44-dependent binding to hyaluronic acid. J Immunol (1993) 151:6712–22.

66. Murakami S, Miyake K, June CH, Kincade PW, Hodes RJ. IL-5 induces a Pgp-1 (CD44) bright B cell subpopulation that is highly enriched in proliferative and Ig secretory activity and binds to hyaluronate. J Immunol (1990) 145:3618–27.

67. Katoh S, Zheng Z, Oritani K, Shimozato T, Kincade PW. Glycosylation of CD44 negatively regulates its recognition of hyaluronan. J Exp Med (1995) 182:419–29. doi:10.1084/jem.182.2.419

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

68. DeGrendele HC, Kosfiszer M, Estess P, Siegelman MH. CD44 activation and associated primary adhesion is inducible via T cell receptor stimulation. J Immunol (1997) 159:2549–53.

69. Firan M, Dhillon S, Estess P, Siegelman MH. Suppressor activity and potency among regulatory T cells is discriminated by functionally active CD44. Blood (2006) 107:619–27. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-06-2277

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

70. Bollyky PL, Lord JD, Masewicz SA, Evanko SP, Buckner JH, Wight TN, et al. Cutting Edge: high molecular weight hyaluronan promotes the suppressive effects of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol (2007) 179:744–7. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.744

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

71. McDonald B, McAvoy EF, Lam F, Gill V, de la Motte C, Savani RC, et al. Interaction of CD44 and hyaluronan is the dominant mechanism for neutrophil sequestration in inflamed liver sinusoids. J Exp Med (2008) 205:915–27. doi:10.1084/jem.20071765

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

72. Sague SL, Tato C, Pure E, Hunter CA. The regulation and activation of CD44 by natural killer (NK) cells and its role in the production of IFN-gamma. J Interferon Cytokine Res (2004) 24:301–9. doi:10.1089/107999004323065093

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

73. Koshiishi I, Shizari M, Underhill CB. CD44 can mediate the adhesion of platelets to hyaluronan. Blood (1994) 84:390–6.

74. Do Y, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M. Role of CD44 and hyaluronic acid (HA) in activation of alloreactive and antigen-specific T cells by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. J Immunother (2004) 27:1–12. doi:10.1097/00002371-200401000-00001

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

75. Mummert ME, Mummert D, Edelbaum D, Hui F, Matsue H, Takashima A. Synthesis and surface expression of hyaluronan by dendritic cells and its potential role in antigen presentation. J Immunol (2002) 169:4322–31. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4322

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

76. Bollyky PL, Evanko SP, Wu RP, Potter-Perigo S, Long SA, Kinsella B, et al. Th1 cytokines promote T-cell binding to antigen-presenting cells via enhanced hyaluronan production and accumulation at the immune synapse. Cell Mol Immunol (2010) 7:211–20. doi:10.1038/cmi.2010.9

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

77. Huet S, Groux H, Caillou B, Valentin H, Prieur AM, Bernard A. CD44 contributes to T cell activation. J Immunol (1989) 143:798–801.

78. Shimizu Y, Van Seventer GA, Siraganian R, Wahl L, Shaw S. Dual role of the CD44 molecule in T cell adhesion and activation. J Immunol (1989) 143:2457–63.

79. Denning SM, Le PT, Singer KH, Haynes BF. Antibodies against the CD44 p80, lymphocyte homing receptor molecule augment human peripheral blood T cell activation. J Immunol (1990) 144:7–15.

80. Ilangumaran S, Briol A, Hoessli DC. CD44 selectively associates with active Src family protein tyrosine kinases Lck and Fyn in glycosphingolipid-rich plasma membrane domains of human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Blood (1998) 91:3901–8.

81. Föger N, Marhaba R, Zöller M. CD44 supports T cell proliferation and apoptosis by apposition of protein kinases. Eur J Immunol (2000) 30: 2888–99. doi:10.1002/1521-4141(200010)30:10<2888::AID-IMMU2888>3.0.CO;2-4

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

82. Galandrini R, Galluzzo E, Albi N, Grossi CE, Velardi A. Hyaluronate is costimulatory for human T cell effector functions and binds to CD44 on activated T cells. J Immunol (1994) 153:21–31.

83. Khan AI, Kerfoot SM, Heit B, Liu L, Andonegui G, Ruffell B, et al. Role of CD44 and hyaluronan in neutrophil recruitment. J Immunol (2004) 173:7594–601. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7594

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

84. Katoh S, Miyagi T, Taniguchi H, Matsubara Y, Kadota J, Tominaga A, et al. Cutting edge: an inducible sialidase regulates the hyaluronic acid binding ability of CD44-bearing human monocytes. J Immunol (1999) 162:5058–61.

85. Siegelman MH, DeGrendele HC, Estess P. Activation and interaction of CD44 and hyaluronan in immunological systems. J Leukoc Biol (1999) 66:315–21.

86. DeGrendele HC, Estess P, Siegelman MH. Requirement for CD44 in activated T cell extravasation into an inflammatory site. Science (1997) 278:672–5. doi:10.1126/science.278.5338.672

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

87. Bollyky PL, Falk BA, Long SA, Preisinger A, Braun KR, Wu RP, et al. CD44 costimulation promotes FoxP3+ regulatory T cell persistence and function via production of IL-2, IL-10, and TGF-beta. J Immunol (2009) 183:2232–41. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0900191

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

88. Nakamura T, Takagaki K, Shibata S, Tanaka K, Higuchi T, Endo M. Hyaluronic-acid-deficient extracellular matrix induced by addition of 4-methylumbelliferone to the medium of cultured human skin fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (1995) 208:470–5. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1995.1362

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

89. Mahaffey CL, Mummert ME. Hyaluronan synthesis is required for IL-2-mediated T cell proliferation. J Immunol (2007) 179:8191–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8191

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

90. Ruffell B, Johnson P. Hyaluronan induces cell death in activated T cells through CD44. J Immunol (2008) 181:7044–54. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7044

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

91. Bonder CS, Clark SR, Norman MU, Johnson P, Kubes P. Use of CD44 by CD4+ Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes to roll and adhere. Blood (2006) 107:4798–806. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-09-3581

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

92. Katoh S, Kaminuma O, Hiroi T, Mori A, Ohtomo T, Maeda S, et al. CD44 is critical for airway accumulation of antigen-specific Th2, but not Th1, cells induced by antigen challenge in mice. Eur J Immunol (2011) 41:3198–207. doi:10.1002/eji.201141521

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

93. Baaten BJG, Li C-R, Deiro MF, Lin MM, Linton PJ, Bradley LM. CD44 regulates survival and memory development in Th1 cells. Immunity (2010) 32:104–15. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.011

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

94. Corthay A. How do regulatory T cells work? Scand J Immunol (2009) 70:326–36. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.2009.02308.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

95. Bollyky PL, Wu RP, Falk BA, Lord JD, Long SA, Preisinger A, et al. ECM components guide IL-10 producing regulatory T-cell (TR1) induction from effector memory T-cell precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2011) 108:7938–43. doi:10.1073/pnas.1017360108

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

96. Petrey AC, de la Motte CA. Hyaluronan, a crucial regulator of inflammation. Front Immunol (2014) 5:101. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00101

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

97. Jiang D, Liang J, Noble PW. Hyaluronan as an immune regulator in human diseases. Physiol Rev (2011) 91:221–64. doi:10.1152/physrev.00052.2009

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

98. Pure E, Cuff CA. A crucial role for CD44 in inflammation. Trends Mol Med (2001) 7:213–21. doi:10.1016/S1471-4914(01)01963-3

99. Mohamadzadeh M, DeGrendele H, Arizpe H, Estess P, Siegelman M. Proinflammatory stimuli regulate endothelial hyaluronan expression and CD44/HA-dependent primary adhesion. J Clin Invest (1998) 101:97–108. doi:10.1172/JCI1604

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

100. DeGrendele HC, Estess P, Picker LJ, Siegelman MH. CD44 and its ligand hyaluronate mediate rolling under physiologic flow: a novel lymphocyte-endothelial cell primary adhesion pathway. J Exp Med (1996) 183:1119–30. doi:10.1084/jem.183.3.1119

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

101. Clark RA, Alon R, Springer TA. CD44 and hyaluronan-dependent rolling interactions of lymphocytes on tonsillar stroma. J Cell Biol (1996) 134:1075–87. doi:10.1083/jcb.134.4.1075

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

102. Patel KD, Cuvelier SL, Wiehler S. Selectins: critical mediators of leukocyte recruitment. Semin Immunol (2002) 14:73–81. doi:10.1006/smim.2001.0344

103. Lee WY, Kubes P. Leukocyte adhesion in the liver: distinct adhesion paradigm from other organs. J Hepatol (2008) 48:504–12. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.12.005

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

104. McDonald B, Jenne CN, Zhuo L, Kimata K, Kubes P. Kupffer cells and activation of endothelial TLR4 coordinate neutrophil adhesion within liver sinusoids during endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol (2013) 305:G797–806. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00058.2013

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

105. Katoh S, Matsumoto N, Kawakita K, Tominaga A, Kincade PW, Matsukura S. A role for CD44 in an antigen-induced murine model of pulmonary eosinophilia. J Clin Invest (2003) 111:1563–70. doi:10.1172/JCI16583

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

106. Noble PW, Lake FR, Henson PM, Riches DWH. Hyaluronate activation of CD44 induces insulin-like growth factor-1 expression by a tumor necrosis factor-alpha-dependent mechanism in murine macrophages. J Clin Invest (1993) 91:2368–77. doi:10.1172/JCI116469

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

107. Noble PW, McKee CM, Cowman M, Shin HS. Hyaluronan fragments activate an NF-kappa B/I-kappa B alpha autoregulatory loop in murine macrophages. J Exp Med (1996) 183:2373–8. doi:10.1084/jem.183.5.2373

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

108. McKee CM, Lowenstein CJ, Horton MR, Wu J, Bao C, Chin BY, et al. Hyaluronan fragments induce nitric-oxide synthase in murine macrophages through a nuclear factor kappaB-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem (1997) 272:8013–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.12.8013

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

109. McKee CM, Penno MB, Cowman M, Burdick MD, Strieter RM, Bao C, et al. Hyaluronan (HA) fragments induce chemokine gene expression in alveolar macrophages. The role of HA size and CD44. J Clin Invest (1996) 98:2403–13. doi:10.1172/JCI119054

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

110. Taylor KR, Trowbridge JM, Rudisill JA, Termeer CC, Simon JC, Gallo RL. Hyaluronan fragments stimulate endothelial recognition of injury through TLR4. J Biol Chem (2004) 279:17079–84. doi:10.1074/jbc.M310859200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

111. Scheibner KA, Lutz MA, Boodoo S, Fenton MJ, Powell JD, Horton MR. Hyaluronan fragments act as an endogenous danger signal by engaging TLR2. J Immunol (2006) 177:1272–81. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1272

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

112. Jiang D, Liang J, Fan J, Yu S, Chen S, Luo Y, et al. Regulation of lung injury and repair by toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat Med (2005) 11:1173–9. doi:10.1038/nm1315

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

113. Taylor KR, Yamasaki K, Radek KA, Di Nardo A, Goodarzi H, Golenbock D, et al. Recognition of hyaluronan released in sterile injury involves a unique receptor complex dependent on toll-like receptor 4, CD44, and MD-2. J Biol Chem (2007) 282:18265–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M606352200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

114. Yamasaki K, Muto J, Taylor KR, Cogen AL, Audish D, Bertin J, et al. NLRP3/cryopyrin is necessary for interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) release in response to hyaluronan, an endogenous trigger of inflammation in response to injury. J Biol Chem (2009) 284:12762–71. doi:10.1074/jbc.M806084200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

115. Hodge-Dufour J, Noble PW, Horton MR, Bao C, Wysoka M, Burdick MD, et al. Induction of IL-12 and chemokines by hyaluronan requires adhesion-dependent priming of resident but not elicited macrophages. J Immunol (1997) 159:2492–500.

116. Eberlein M, Scheibner KA, Black KE, Collins SL, Chan-Li Y, Powell JD, et al. Anti-oxidant inhibition of hyaluronan fragment-induced inflammatory gene expression. J Inflamm (Lond) (2008) 5:20. doi:10.1186/1476-9255-5-20

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

117. Krejcova D, Pekarova M, Safrankova B, Kubala L. The effect of different molecular weight hyaluronan on macrophage physiology. Neuro Endocrinol Lett (2009) 30:106–11.

118. Esser PR, Wolfle U, Durr C, von Loewenich FD, Schempp CM, Freudenberg MA, et al. Contact sensitizers induce skin inflammation via ROS production and hyaluronic acid degradation. PLoS One (2012) 7:e41340. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041340

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

119. Filion MC, Phillips NC. Pro-inflammatory activity of contaminating DNA in hyaluronic acid preparations. J Pharm Pharmacol (2001) 53:555–61. doi:10.1211/0022357011775677

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

120. Ebid R, Lichtnekert J, Anders HJ. Hyaluronan is not a ligand but a regulator of toll-like receptor signaling in mesangial cells: role of extracellular matrix in innate immunity. ISRN Nephrol (2014) 2014:714081. doi:10.1155/2014/714081

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

121. Li Z, Potts-Kant EN, Garantziotis S, Foster WM, Hollingsworth JW. Hyaluronan signaling during ozone-induced lung injury requires TLR4, MyD88, and TIRAP. PLoS One (2011) 6:e27137. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027137

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

122. Monzon ME, Fregien N, Schmid N, Falcon NS, Campos M, Casalino-Matsuda SM, et al. Reactive oxygen species and hyaluronidase 2 regulate airway epithelial hyaluronan fragmentation. J Biol Chem (2010) 285:26126–34. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.135194

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

123. Martin SF, Dudda JC, Bachtanian E, Lembo A, Liller S, Durr C, et al. Toll-like receptor and IL-12 signaling control susceptibility to contact hypersensitivity. J Exp Med (2008) 205:2151–62. doi:10.1084/jem.20070509

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

124. Vasconcelos JF, Teixeira MM, Barbosa-Filho JM, Agra MF, Nunes XP, Giulietti AM, et al. Effects of umbelliferone in a murine model of allergic airway inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol (2009) 609:126–31. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.03.027

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

125. Acharya PS, Majumdar S, Jacob M, Hayden J, Mrass P, Weninger W, et al. Fibroblast migration is mediated by CD44-dependent TGF beta activation. J Cell Sci (2008) 121:1393–402. doi:10.1242/jcs.021683

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

126. van der Windt GJ, Schouten M, Zeerleder S, Florquin S, van der Poll T. CD44 is protective during hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2011) 44:377–83. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2010-0158OC

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: hyaluronan, CD44, inflammation, immune cells, leukocytes

Citation: Lee-Sayer SSM, Dong Y, Arif AA, Olsson M, Brown KL and Johnson P (2015) The where, when, how, and why of hyaluronan binding by immune cells. Front. Immunol. 6:150. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00150

Received: 26 January 2015; Accepted: 20 March 2015;

Published online: 14 April 2015.

Edited by:

David Naor, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, IsraelReviewed by:

Toshiyuki Murai, Osaka University, JapanCopyright: © 2015 Lee-Sayer, Dong, Arif, Olsson, Brown and Johnson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pauline Johnson, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Life Sciences Institute, University of British Columbia, 2350 Health Sciences Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3, Canada e-mail:cGF1bGluZUBtYWlsLnViYy5jYQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.