- 1Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, United States

- 2The Past Foundation, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States

Research inspired by collective action theory has provoked a rethinking of premodern governance, including state formation. We briefly summarize key elements of this theoretical turn, first, by demonstrating that, as predicted by the existing theory, political collective action is enhanced when the provision of good government motivates taxpayer compliance. Beyond that key process, our cross-cultural comparative investigation identified a suite of corollary social and cultural factors, including civic ritual, that, side-by-side with good government, served to undergird the institution of political collective action. We investigate, in particular, policies and practices that fostered the transformation of what had been a dominated and socially fragmented subaltern into a politically engaged and conditionally compliant citizenry. We discuss this process in relation to administrative policies and practices and in relation to evidence we found for directed cultural change purposed to enhance consensus and forbearance in the face of social divisiveness and political inequality.

Introduction

Historically, anthropologists and other historical social science theorists argued that, while cooperation could be the basis for social cohesion among kin or in other small groups, at large scale, and in the context of social diversity, social integration was only possible when a politically coercive chiefdom or state dominated a passive and easily mystified subaltern (e.g., as discussed in Thurston, 2010). In recent decades, however, as coercion theory came under critical scrutiny (e.g., Blanton, 1998), anthropologists searched for a more encompassing theoretical frame and eventually identified a potentially promising path forward in the work of collective action theorists (e.g., Bates, 1983; Hechter, 1990; Ostrom, 1990; Lichbach, 1996), especially Levi's (1988) fiscal theory. A collective action approach is unlike coercion theory in multiple ways, most importantly, the lack of an assumed subaltern who is passive and easily mystified. Instead, the foundational hypothesis is that both rulers and subjects are thoughtful social actors (“contingent cooperators”) who will agree to limitations on their selfish actions, although only contingently, when they perceive that the actions of others are consistent with mutual benefit. However, there is a caveat (a “cooperators dilemma;” Lichbach, 1996). While collective action has the capacity to bring mutual benefits, to institute and sustain it is challenging and costly. To demonstrate a commitment to mutual benefit, a state must extend its governing capacity across society, for example, to provide public goods. In addition, as we discuss below, since the choices of contingent cooperators reflect their knowledge of others' actions, collective action is further undergirded when there are enhanced opportunities for comingling, social interaction, and communication across social, geographical, and cultural divisions.

As students of premodern state formation, we and other researchers found ideas about conditional cooperators and cooperator's dilemmas to be thought-provoking in the way they present novel research questions, most importantly: Did the social and cultural architects of premodern states, and their subjects, understand and address conditional cooperation and cooperator's dilemmas, and, if so, what kinds of strategic actions did they employ in response, what causal factors might have prompted such actions, and what were the social consequences? Our goal in this article is to provide both a brief summary of work we and others have done in this vein (recent sources include Blanton and Fargher, 2008, 2016; Blanton et al., 2020, 2022; Fargher et al., 2022; Feinman et al., 2022; Carballo and Feinman, 2023; Feinman, 2023), and an expansion of prior work in ways that, we suggest, will enrich the existing framework. In this paper's first section, “Premodern Government and Its Variations as Seen from the Vantages of Good Government and Cross-Cultural Analysis,” we evaluate the robustness of existing collective theory by summarizing key features of institutional variation and commonality among the most collectively organized polities we studied. In following sections, we focus attention on one of the most vexing issues pertaining to the institution of political collective action, one that is not specifically addressed in current theory: How could a powerless, socially and culturally fragmented, and socially isolated (even, in some cases untouchable) subaltern sector of autocratic states be incorporated into a polity as compliant taxpaying citizens and even as active participants in societal governance? Our comparative investigations pointed to the playing out of cultural and institutional processes that, we suggest, undergirded the emergence of a citizenry (in sections titled “Encouraging the Commingling of Social Categories Usually Kept Separate and Unequal” and “Generating and Regenerating Egalitarian Notions and Behaviors Through Civic Ritual”). Lastly, we address how our exploratory work exposed what were largely unintended outcomes of political collective action. We suggest these outcomes were in addition to other factors that motivated compliance with governing policies and practices, while also providing additional sources of revenue for state-building. We describe these in a section titled “Unintended Outcomes of Political Collective Action: The Unleashing of the Social Energy of Collective Action and an Engaged Citizenry.”

Methods

We address questions surrounding the emergence of premodern political collective action through two closely intertwined research paths. By employing cross-cultural comparative analysis, we are able to demonstrate the wide range of variation in forms of both autocratic and collective polities, while also carrying out statistical analyses to test hypotheses about the causes of collective action and to elucidate how governing capacity was built in ways that would foster it.1 To evaluate the possibility of viewing collective action theory through a quantitative lense, we conducted a cross-cultural comparative project that involved the systematic numeric coding of historical, ethnographic, and archaeological data from a socially and culturally diverse world-wide sample of 30 premodern states not influenced by contemporary notions of democratic governance (Blanton and Fargher, 2008, 2016; Blanton et al., 2021). The cross-cultural method is ideal for our purposes because it demands close attention to issues of validity and reliability of results and because our sample encompasses a diversity of forms of governance ranging from more autocratic to those expressing key elements of collective action.

Our other path to the study of political collective action is a qualitative analysis of directed cultural change, a form of analysis that should be integral, we argue, to any inquiry into the institution of political collective action (Blanton and Fargher, 2016, p. 191–244). We investigate cultural change from the perspective of ritual, a traditional topic of social science, particularly anthropological, inquiry (e.g., as summarized in Feinman, 2016). Yet, because our discussion of ritual is meant to dovetail with our consideration of the emergence of a citizenry, it only faintly echoes previous social science thinking, including that ritual serves primarily to strengthen traditional social ties, legitimates a hierarchical social order, or provides a voice for subaltern defiance against oppression. Instead, from our perspective, ritual can also be a powerful force for introducing and reinforcing new notions consistent with collective action, including an awareness of the need for consensus and forbearance in the face of social divisiveness and political inequality.

Premodern government and its variations as seen from the vantages of good government and cross-cultural analysis

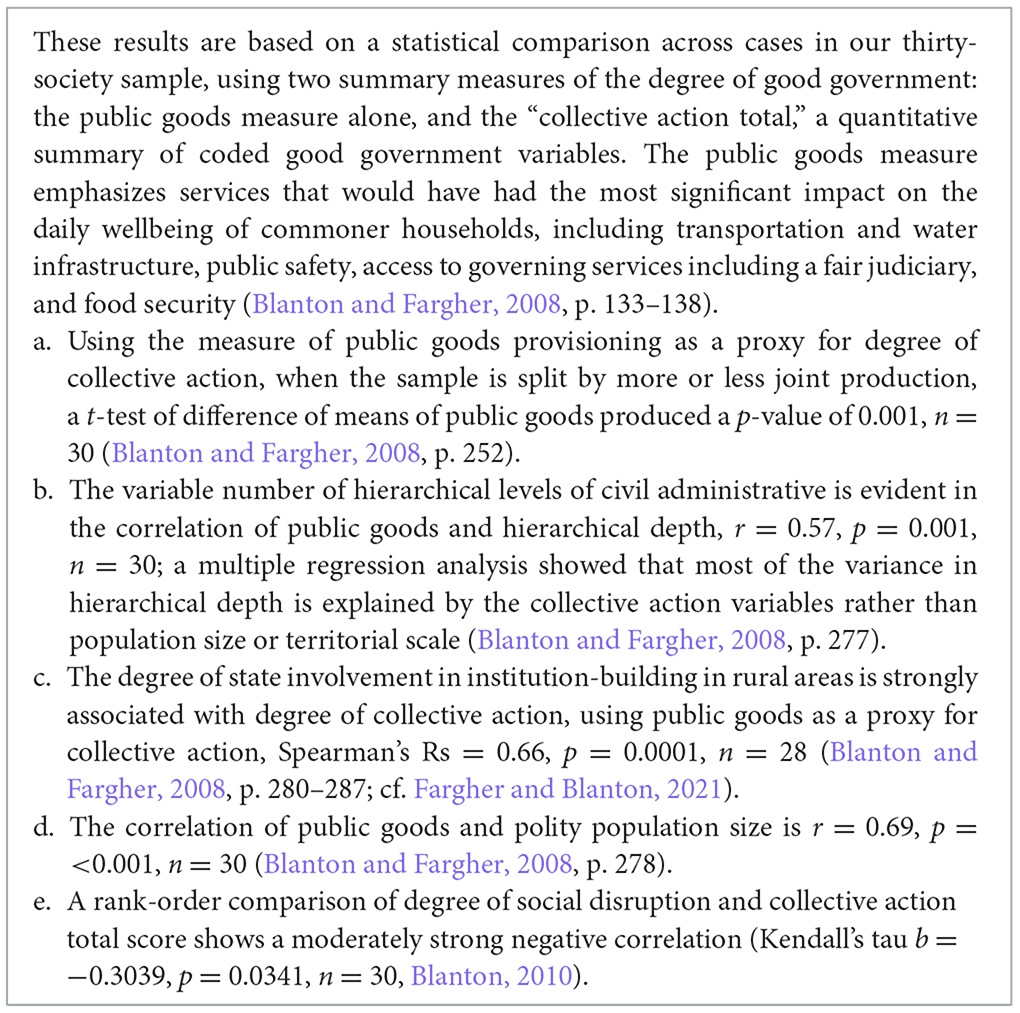

Our quantitative comparative research confirmed the reality of political collective action in premodernity and allowed for an evaluation of a key causal proposal of collective action theory (Blanton and Fargher, 2008). Although cross-cultural comparative research does not entail the investigation of historical sequences to identify the temporality of proposed causes and political outcomes, it does allow for an estimate of whether or not a proposed causal sequence is likely valid by calculating the degrees of correlation or association between multiple variables across a sample of societies. The comparative analysis did provide evidence that a fiscal economy featuring an important component of joint production (when the state's revenue and labor needs, including military service, were provided by virtually all households irrespective of status, wealth, rural or urban) will provide a fiscal environment suited to funding the high costs of collective state- building while bringing benefits to taxpayers, as Levi (1988) proposed (Table 1. a). In such cases, the central causal force of political change, rather than coercion, was the establishment of a mutual, but contingent, bond of obligation between governing authorities and subjects (“contingent mutuality”).

To build and sustain a mutual bond of obligation requires that the leadership will accept institutional limits on their political agency and that they have the willingness and ability to extend governing capacity across society in a manner analogous to what political scientists refer to as good government (e.g., Levi, 1988, 2022; Cook et al., 2005; Ahlquist and Levi, 2011; Rotberg, 2014; Rothstein, 2011, 2014; see also Blanton et al., 2021). Good government requires the building of administrative institutions to detect and punish social malfeasance such as shirking and free riding on public resources, to provide information about and access to governing institutions and positions of governing authority (“open recruitment”), to tax equitably, and to place enforceable limits on executive and judicial agency.

In the following descriptive section, we briefly summarize how these requirements were met in polities in our sample that scored highest in quantitative measures of good government (more detailed accounts are found in Blanton and Fargher, 2008); although the coding included variables related to institutional controls over the apical leadership, the categories listed below emphasize the institution of governing capacity aimed to incorporate commoner subjects into the body politic. The polities are listed below in order from lowest to highest scoring in this group (Blanton and Fargher, 2008, Table 10- 6, p. 261; the date indicated is the “focal period” for each polity, the specifically coded time period during which governing institutions remained highly stable).

Mughal (CE 1556–1606)

Mughal, as in some other cases summarized below, is among the list of most collectively organized in terms of the institutional variables we emphasize in this article but was lacking in an administrative process for impeachment of the apical leadership. In this case and others in this sub-sample [Rome, Ming, and Venice], the eventual failure of the apical leadership to uphold institutions and values that had been foundational to the polity was a cause of societal collapse (Blanton et al., 2020).

Public Goods: famine relief (Hasan, 1936, p. 282–287; Habib, 1963, p. 102–104); transportation infrastructure (Farooque, 1977, p. 54–6; Grover, 1994, p. 239); sewers and public water in some cities (Sarkar, 1963, p. 211; Blake, 1991, p. 64).

Open Recruitment: most official positions were open irrespective of patrimony or religion (Ali, 1995, p. 271–2), although in some peripheral parts of the empire, local hereditary Hindu rulers (zamindars) were allowed to remain in office but were required to conform with Mughal governing policies (Habib, 1963, p. 174, 292).

Tax Equitability: massive survey of taxable land, one of the most expansive in premodernity, greatly enhanced equitability of tax obligation and taxpaying compliance (e.g., Habib, 1963, p. 234).

Institution-Building at the Local Level: some degree of reorganization in rural areas (Habib, 1963, p. 178, 290; Sarkar, 1963, p. 12) and in cities (Blake, 1991); extensive institutional ability to control corruption among administrative officials, including at the local level (Habib, 1963, p. 290; Sarkar, 1963, p. 54).

Aztec (CE 1428–1521; more information below)

Public Goods: water-control and transportation infrastructures enhanced agricultural production and rural-urban and intraurban interaction in the core region; food stores for famine distribution (Davies, 1987, p. 117; Berdan, 2014, p. 76–81); judicial system built on principles of blind justice and broad access to courts and included extensive controls to identify and punish judicial malfeasance (Offner, 1983); public education for elite and commoner, including for judicial training (Offner, 1983, p. 111–112).

Open Recruitment: commoners were selected for participation in governing councils based on merit (numerous sources including Davies, 1987: 114–115, Offner, 1983, and Fargher et al., 2017: 152–153).

Tax Equitability: effective tax administration including land surveys to assure equitable taxation (van Zantwijk, 1985, p. 275–276), particularly in the empire's core region

Institution-Building at the Local Level: This history is not well-known, but local-scale (tlaxilacalli) units were highly self-governing, although linked into the central administration, for example for tax collection (Berdan, 2014, p. 136). Strategic provinces, military garrisons, and trade entrepot were established at the imperial fringes (Smith, 1996).

Lozi (CE 1864–1900)

Public Goods: agricultural development and canal construction, for both swamp drainage and transportation in the vast (7,000 sq. km) upper floodplain of the Zambezi River (Prins, 1980, p. 58–70); food security was made possible by public access to state gardens and food distribution in emergencies; citizen access to an organized judiciary (Gluckman, 1961, p. 63; Prins, 1980, p. 93).

Open Recruitment: commoners served on the major governing council, and there were lower-level salaried officials who governed side-by-side with local elite (Gluckman, 1941, p. 47, 66).

Tax Equitability: little information is available.

Institution-Building at the Local Level: some new communities were established in areas developed for agriculture by the state, composed of persons who were “followers” of the rulers (Prins, 1980, p. 58–70), or who were immigrant refugees escaping political chaos beyond Lozi borders (Colson, 1969, p. 30).

Roman High Empire period (CE 69–192)

Like the Mughal, there was no established impeachment process for the apical leadership, yet there was a broad understanding of the importance of equal treatment that weakened the sense of noble privilege (Hannestad, 1988, p. 196).

Public Goods: extensive transportation infrastructure and water control, including improved domestic water supply in some cases (Morely, 1996, p. 104–5); improved city planning and rules regarding uses of urban spaces to improve legibility of cities and intraurban movement (van Tilburg, 2007).

Open Recruitment: increase in administrative appointments to commoners and freed slaves (Eck, 2000); broader selection for positions in the senate by comparison with the Republican Period (Levick, 1996).

Tax Equitability: improved taxation administration based on censuses (Hitchner, 2005, p. 211).

Institution-Building at the Local Level: increased accountability of provincial governors to reduce official corruption (Abbott, 1963, p. 138); empire-wide mandate to build governing capacity at the community level (Galsterer, 2000, p. 345), including the establishment of police and fire departments in Rome (Abbott, 1963, p. 280).

Early and middle Ming dynasty (CE fifteenth century)

Public Goods: famine relief and food price controls to counter attempts by wealthy families to alter grain prices counter to commoner interests (Wong, 1991); institutions to improve urban governance and urban public goods (Fei, 2009); issuance of a vernacular version of the law code (Langlois, 1998, p. 180).

Open Recruitment: open recruitment to governing and military administrations, and accompanying state-funded public schools to prepare less-wealthy students for qualifying exams (Ho, 1962, p. 225; Elman, 1991).

Tax Equitability: a massive land census was a basis for empire-wide equitable taxation (Wiens, 1988).

Institution-Building at the Local Level: mandates to improve county-level (rural hsien) administration and enhancement of village-scale (li) social interaction and cooperation (Hucker, 1998, p. 73, 89–91, 98–99).

Republic of Venice (CE 1290–1600)

Public Goods: improved urban administration of public plazas, streets and canals (Lane, 1973, p. 16; Norwich, 1982, p. 26; Romano, 1987, p. 22); improvement of public safety measures (Romano, 1987, p. 9; Chambers and Pullan, 2001, p. 20); maintenance of food price security (Lane, 1973, p. 14; Chambers and Pullan, 2001, p. 13); public health and public education (Norwich, 1982, p. 284; Chambers and Pullan, 2001, p. 113).

Open Recruitment: membership of the governing Great Council was closed, but numerous salaried officials were recruited, equitably, in Venice and its mainland cities (Lane, 1973, p. 266; Norwich, 1982, p. 208–9).

Tax Equitability: governing institutions implemented to identify tax shirking by wealthy families (Chambers and Pullan, 2001, p. 136); salaried officials managed tax collection (Lane, 1973, p. 266).

Institution-Building at the Local Level: political organization in the mainland dependencies was modeled after the system in Venice (Norwich, 1982, p. 208–9); state attorney offices monitored for official malfeasance and served as channels for communicating commoner voice (Lane, 1973, p. 100).

Athens (403 to 322 BCE, although some key reforms were initiated after 507; more information below)

Public Goods: court cases adjudicated issues of food security and food price control (Moreno, 2007) and some magistrates were assigned to regulate grain prices (Gulick, 1973, p. 302); pensions were made available to some needy persons, including to families of soldiers (Gulick, 1973); broad access to courts (e.g., Hansen, 1999, p. 301).

Open Recruitment: open jury selection by lot (Hansen, 1999, p. 301); governance through citizen councils (Hansen, 1999, p. 34, passim); administrators (magistrates) chosen by lot or election for short terms of office in most cases.

Tax Equitability: one magistrate board was charged with identifying and punishing taxpayer non-compliance (Gulick, 1973, p. 303), but otherwise there was little in the way of censusing or other measures to assure tax equitability (Hansen, 1999, p. 111, 262).

Institution-Building at the Local Level: new rural organization for village-scale governance of tribes, districts, and demes; deme governance was by citizen assemblies that elected and monitored demarchs for 1-year terms and sent representatives to the governing Council of the Five Hundred (Hansen, 1999, p. 259–265, 388); households were reimagined as semi-autonomous units directly tied to the state rather than to tribe or patronage systems (Westgate, 2007).

These brief summaries demonstrate cross-polity variability in the specific elements of good government, but they also illustrate commonalities, particularly the tendency to emphasize the supply of public goods and open recruitment to positions of governing authority. Programs to enhance tax equitability were extremely difficult and costly to implement, given the limited transportation and communication technologies of premodernity, yet were addressed in some cases, and on a very large scale in some. The comparative method also allows for statistical analyses to evaluate the theory's causal hypotheses. We mentioned finding statistical support for the fiscal model, and we also found a relatively greater degree of administrative scale and hierarchical complexity in polities exhibiting features of collective action (Table 1. b). Especially in polities scoring among the highest on measures of collective action, the central authorities saw value in devoting resources to institution-building at the local level, even in distant rural communities. This kind of administrative outreach, which is of interest for our discussion, sought to increase local-scale governing capacity according to collective principles and to provide enhanced opportunities for social interactions both within the local communities, between those communities and the state, and between rural communities and urban populations (Table 1. c).

While cross-cultural comparative analysis did support the validity of a fiscal model, the quantitative analyses have also served to challenge commonly expressed but misleading ideas. For example, given preindustrial transportation and communication technologies, some have claimed that premodern collective action would have been feasible only in relatively smaller polities (e.g., Olson, 1965; Korotayev, 1995; Boix, 2015, p. 257), but our analyses demonstrate a strong positive correlation between the degree of collective action, expressed as good government, and a polity's total population size (Table 1. d; the positive correlation holds even when large-population outliers, including the Roman Empire, Mughal, and China are removed from the sample). While collective action was identified in smaller polities as well, some of the highest scoring on good government were among the most populous in premodernity and comparable in scale to many modern states, including the Ming focal period with well over 100 million inhabitants.

Was there a “virtuous circle?”

Levi (2022, p. 215) argued that, in contemporary polities, a “virtuous circle” results when good government inspires taxpayer compliance. We looked for evidence of this process in the comparative sample but found little valid data. It is possible to evaluate the hypothesis, however, by using the relative frequency of notable rebellions or other anti-state actions during a polity's focal period as a proxy for willingness to comply. Fortunately, most of the sources in the thirty-society sample did document the occurrence and frequency of major disruptive episodes, including factional disputes over political control, successional struggles, and commoner resistance to a state's policies and actions. A tabulation of oppositional actions did demonstrate that the more autocratic polities experienced relatively higher frequencies of confrontational and sometimes damaging forms of opposition to the state's leadership and its policies (Table 1. e).

Encouraging the commingling of social categories usually kept separate and unequal

As “hybrid” spaces, marketplaces “unsettle” traditional forms of identity through their “commingling of categories usually kept separate” (Stallybrass and White, 1986, p. 27).

The “unnatural” market economy is problematic because it “equalizes things and thus challenges the natural order of things” (Aristotle, quoted in Booth, 1993, p. 153).

In addition to hypothesis-testing, cross-cultural analysis has allowed us to widen the aperture of collective action theory to reveal aspects of state-building not previously addressed nor well-theorized. We include in these findings evidence that contingent mutuality and cooperation at the scale of society are undergirded by institutional and cultural policies and practices that expanded opportunities for persons to engage in a broad range of cooperative interactions and alignments beyond the local scale and beyond social and cultural divisions. We discuss this process in terms of multiple interrelated factors: the decline of local-scale cooperative groups; the increased importance of marketplace economies; and city planning to enhance urban spatial integration and legibility.

The decline of local-scale cooperative groups

Our studies of cities illustrate how a contingent cooperator might choose increased compliance with a state's system of government, it can also imply the possibility that persons will choose to reduce participation in localized cooperative social formations. This is evident in the case of urban settings, where we found that political collective action at the scale of the state brought a relative decline in the functional significance of what had been socially introverted and bounded neighborhoods. This is a topic worthy of additional investigation; however, we suggest that, owing to the provision of urban public goods, the introverted neighborhoods were rendered less significant as sites of local-scale cooperative responses to urban problems such as crime and fire control (Blanton and Fargher, 2012; Fargher et al., 2019). Beyond the urban domain, public goods and other aspects of good government appear to have had a similar influence motivating persons, even in rural areas, to shift their social identities away from bounded and highly self-sufficient ethnic enclaves to a greater degree of identification with collectively organized governance (Blanton, 2015).

The increased importance of marketplace economies

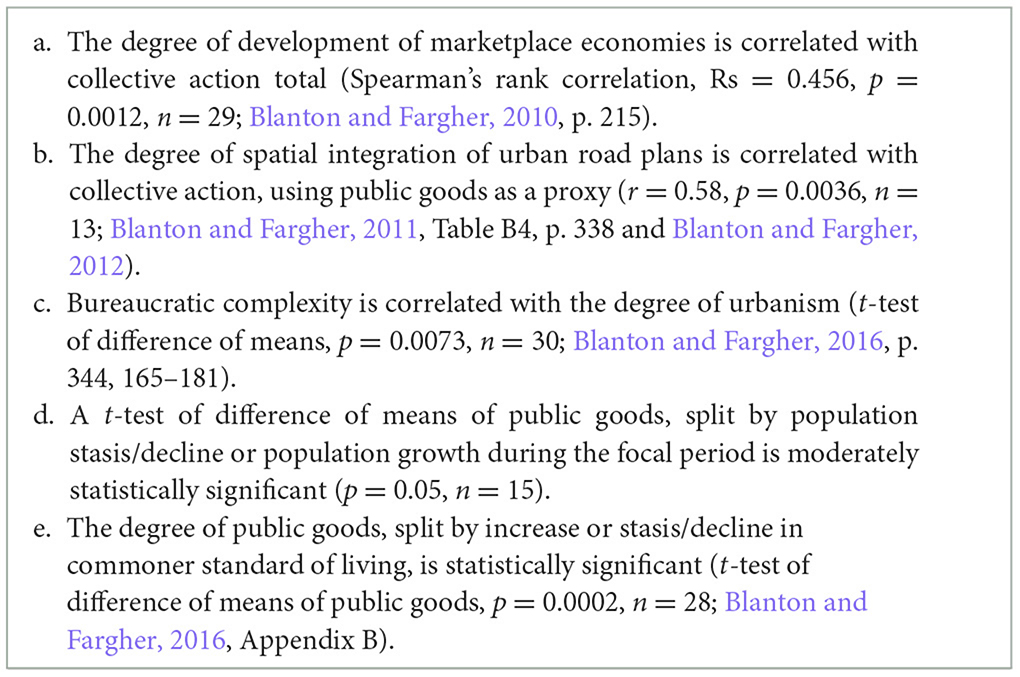

Our cross-cultural analysis provides evidence for a processual connection between collective action in state-building and the degree of development and economic importance of marketplace economies that brought together large numbers of socially diverse buyers and sellers in designated public spaces and on scheduled market days, while, in many cases, providing a new source of state revenues (Table 2. a). Although marketplace economies did not always directly reflect state-building policies (Blanton and Fargher, 2010) and could be threatening to an entrenched elite (as Aristotle indicates), comparative research has demonstrated that what we call “open” marketplaces (lacking barriers to participation, unlike elite-driven long-distance trade) and their egalitarian “moral economies” (Blanton, 2013, p. 28–30) were a force consistent with comingling and with the emergence of egalitarian notions as argued by Stallybrass and White (cf. Rollison, 2010; Romano, 2015, p. 222; e.g., Blanton and Fargher, 2016, p. 278–281; Sewell, 2021), including in Classical Athens (Brown, 1947, p. 108; Redfield, 1986). Further, marketplaces have had political consequences as sites of “anti-hegemonic discourses” (Scott, 1990, p. 122, cf. Yang, 1998, p. 164).

Table 2. The commingling of social categories usually kept separate and the unleashing of the social energy of political collective action and an engaged citizenry.

City planning to enhance urban spatial integration and legibility

In addition to market growth, we noted that state-builders foregrounding collective forms of government took measures to improve intraurban movement in densely packed and traffic-congested cities (Blanton and Fargher, 2011, 2016, p. 165–190). These policies involved the construction of transportation infrastructure to improve the spatial integration and legibility of city streets, especially by building new main roads that linked highly visible intersections or other points of interest (e.g., as discussed in Hillier, 1989). Urban geographers have shown how increased spatial integration and legibility provide urban residents with more efficient movement options while also enhancing accessibility for rural-urban travelers. They also boost the ability of administrators, police and emergency services to respond to citizen needs (cf. Sharifi, 2019). Although road plans are not available for all cities in the thirty-society sample (states scoring low on good government rarely bothered to commission city maps), from the available data we found a statistically significant correlation between degree of collective action and spatial integration and legibility of urban road networks (Table 2. b).

Generating and regenerating egalitarian notions and behaviors through civic ritual

As Shore (1996, p. 208) notes, while new institutions and cultural codes might arise from the ideas of a particular person or group, it is not an easy task to project those ideas into a diverse and divided public to become part of what is considered by most to be ordinary life. To this point, we have addressed Shore's issue in relation to cooperation and collective action by emphasizing how good government and related policies enhanced the potential for social interactions and cooperative actions among a diverse public. In the following section we augment those discussions by turning attention to the role of public civic ritual as a complementary force able to represent and reinforce egalitarian notions while enhancing the degree of shared knowledge among a citizenry assembled for civic rituals (e.g., Ober, 2006). We do this below by comparing Classical Athens and Aztec, among the highest-scoring polities on measures of good government (see also our prior comparison of Athens and Aztec Tlaxcallan in Fargher et al., 2022). A two-polity comparison does not address issues of validity and reliability. Yet, given the striking similarities in the nature and purposes of civic ritual in two entirely historically unrelated cases, we suggest, does point to underlying processes related to how new and transformative ideas can be projected out into a diverse society.

The comparison of Aztec and Athens brings into sharp relief the contrast between the public rituals of two highly collective polities by comparison with the more autocratic polities. In the latter (making up the majority of our sample, 19 of 30), public rituals were purposed primarily to reaffirm the unquestionability of rule by kings who were deified and/or served as conduits between their subjects and transcendent cosmic forces outside the experience of ordinary life (e.g., Wolf, 1999). By contrast, among the more collective states we found a greater emphasis on civic rituals consistent with a process we call the “problematization of state and religion” (Blanton and Fargher, 2013). In Athens, for example, with the advent of the democracy there was “...a deliberate decision not to expand the role of priests and a preference for the development of cults in which the stress was on ceremony, competitions, and participation rather than on prayer and sacrifice” (Jameson, 1997, p. 176); and as Carlton (1977, p. 234) stated it “Such a system hardly encouraged the emergence of a priestly literati who alone could interpret the mysteries.2” Among cases in the comparative sample, these policies were not exactly like the “separation of church and state” in modern democracies, but problematization did provide for a degree of instituted separation of the political from the religious to render authorities impeachable, to increase possibilities for social interaction across the boundaries of religious communities, and to increase equitability in access to judicial services, public goods, and positions of authority (Blanton, 2016, see also Sen, 2005, p. 16, discussing Mughal ecumenism). As such these civic rituals can be fitted into Stanley Tambiah's category of “regulative rituals” (Tambiah, 1981, p. 127) in that, rather than serving to legitimate a system of centralized power, they served to honor policies and practices that enabled the pursuit of collective benefit by promoting inclusion and forbearance in the face of potentially conflictive social diversity.

Ritual expressions of communitas, liminality, and structure

The following exploratory foray into civic ritual expands on our earlier work (Blanton, 2016; Blanton and Fargher, 2016, p. 191–244) inspired by sources such as Chwe (2001), Tambiah (1981), and, especially, Turner (1969, 1974, 1988, 2012) and Turner and Turner (1978). In his major publications (1969, 1974, 1988) Victor Turner contrasted the dynamic interactions between two sociocultural patterns internal to societies. In the “structural,” pattern, adherents aim to perpetuate a socially differentiated and hierarchical system of political, legal, and economic statuses, while the pattern of “anti-structure” or “liminality” is socially and culturally transformative. “Liminars” exist outside of, or reject, elements of the normative system to create an alternative state of being that, unlike a status system, is based on notions of mutual moral commitment of equals (“communitas”). The following highlights key features of the liminal domain, drawing primarily from V. Turner (especially Turner, 1969, p. 106 and Turner, 1974, p. 231–271).

The egalitarianism of communitas

Communitas binds people together in an egalitarian association of persons who share a history of marginal origins, exclusion, lack or loss of status, shared suffering, or relative poverty (e.g., Turner, 2012). However, we would point out that in the examples described below some members of an elite saw value in the idea of communitas as a way to build a more just and incorporative society that would invite broad public participation in civic affairs and compliance with obligations.

Symbolic representation of liminality

The liminar's minimal concern for conventional categories, including gender distinctions, provides a less clear signaling of rank or role. This condition is seen by advocates of structure as a dangerous anarchical threat to their preferred social order because liminars elude or slip “through the network of classifications that normally locate states and positions in cultural space” (Turner, 1969, p. 95). In both of the cases discussed below, the liminal state was symbolically associated with the dangers and disorderliness of wilderness and animals and the anarchy of darkness and the night as contrasted with the orderliness of daytime awakeness (cf. Galinier et al., 2010). Mythological accounts illustrate the force of liminality through stories of jesters or tricksters who ridicule established forms of privilege and authority.

Structure and liminality in Athenian and Aztec dualism

In Athens, the sixth century BCE overthrow of aristocratic government brought an expanded sense that all persons had the potential for virtuous and rational actions, an egalitarian notion that had originated among rural agricultural populations during the Archaic period (Raaflaub and Wallace, 2007). According to Hanson (1999), change resulted when rural food production became increasingly important in an expanding and economically diverse society, and Snodgrass (1981, p. 102) and others have argued that subaltern transformation resulted when hoplite phalanxes made up of commoners became important military formations. Following the rejection of aristocratic governance, new rituals and stories depicted how persons who had thrived in the margins eventually entered into the urban center and influenced its more structured culture. The egalitarian turn was reflected in the notions of isegoria (freedom of speech) and isonomia (equal rights) and in extending access to governing authority to (male) citizens who could serve in diverse governing offices, councils, and kinds of military service (women were expected to avoid most public activities, although some did attend the markets and possibly the newly-devised public performances; Cartledge, 2016, p. 128, 136–7). Similarly, Aztec society was built, in part, on an egalitarian notion that persons from the margins, who had gradually adopted key features of urban culture, could participate in political and marketplace governance, in the latter setting including women in the role of market judges (a liminal process regarding gender is more evident in Aztec society than in Athenian society. Aztec women moved freely in public, participated actively in the marketplaces, invested in long-distance trading ventures, and could own land; Offner, 1983, p. 205; Berdan, 2014, p. 205–208).

In both Aztec and Athenian cultures, structure was symbolically associated with urbanized regions that featured high culture, strict moral codes, orderly cities, writing, and wealth production primarily through elite networks of patronage. Liminality was associated with rural or marginal environments where persons were thought to live closer to a state of nature and thus constituted a dangerously transgressive threat to the structured social order. In both cases, the various dimensions of structure and liminality were condensed symbolically into mythical figures whose actions epitomized the dissimilar states of being. These were Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca for the Aztecs, Athena and Dionysus (along with Artemis and Hermes) for Athens/Attica. In their respective accounts of culture history, the mythical figures associated with the liminal impulse had entered into the urban zones where they eventually became part of the social and cultural fabrics.

In Aztec culture, the duality of structure and liminality was understood as one expression of a pervasive dualistic process, teotl, that Maffie (2014, p. 137–138, 167–168) terms an agonistic inamic unity of complementary pairs. In this sense, we suggest, even though structure and liminality are different and even at times antagonistic social forces, still, their ceaseless interaction was understood as a productive tension that generates and regenerates Aztec society. The structured dimension, in that view, was represented by the Nahua-Toltec peoples, whose adulation was to Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl (van Zantwijk, 1985; Nicholson, 2001; this account is summarized from a large literature, but we mention several key sources: van Zantwijk, 1985; Nicholson, 2001; Fargher et al., 2010; Maffie, 2014; Olivier, 2014). The Nahua-Toltec peoples traced their origins to the agriculturally productive Basin of Mexico and surrounding areas of Central Mexico where they had always lived, while liminality was represented by the various Chichimec ethnic groups who, according to mythical accounts, had migrated into the Basin and adjacent areas from a place called Aztlan, located in the environmentally marginal northern desert where they had been poor and technologically backward. Beginning about 1,000 CE, roughly coeval with the rise of the highly commercialized Postclassic Mesoamerican world-system (Smith and Berdan, 2003), the Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl duality was displayed in statuary. Tezcatlipoca was symbolically associated with the night, the moon, the jaguar (a nocturnal predator), and the capacity to detect the true moral character of persons irrespective of appearance or pedigree, thus, among other features, symbolizing blind justice. Tezcatlipoca was also a trickster whose persona was shifting and elusive, and thus aligned with the idea that the self may transcend existential boundaries; for example, one form of Tezcatlipoca's symbolic expression was as Moyocoyotzin, “he who creates himself” (Heyden, 1991, p. 189). Through their challenging and dangerous migrations from the desert, the Chichimec ethnic groups gradually adopted elements of Nahua-Toltec culture yet remained less wedded to the notion of royal rule and privilege than their Nahua-Toltec counterparts.

In Athenian thought, the polis center featured a male dominated, rationally ordered, and strongly hierarchical society, while the geographical margins (oros) were populated by farmers and marketplaces where even commoners could create wealth through commercial transactions. The margin was also thought to be inhabited by mythical figures who valorized ecstatic states of being such as the dancing satyrs and maenads and a black goat-skin caped apparition associated with Dionysus (we developed this summary from multiple sources including Dodds, 1951; Vidal-Naquet, 1981; Cartledge, 1985, 2016; Goldhill, 1990, 2000; Zeitlin, 1990; Buxton, 1992; Meier, 1993; Connor, 1996; Parker, 2006; Evans, 2010; Bettini and Short, 2011). The margin was the domain of darkness, the left (evil) side of the body, gender uncertainty, femininity, and the regenerative powers of agriculture, including wine production associated with Dionysus. The latter was understood to exhibit a cunning, guileful, potentially deceptive and uncertain mentality that challenged the truth of the center's preferred form of highly structured male-centric rationality, purity of being, and inherited privilege. The liminal mentality was epitomized by Dionysus but also by Hermes (the thief) associated with the rural marketplaces, oral communication, exchange, and encounter. Liminality was also represented by the goddess Artemis who exemplified the potential of humans to undergo transformation and transitory states of being.

Rituals and the transcendence of conflicting interests

In both Athenian and Aztec societies, diverse and contending views of humanity and society did not bring persistent and unresolvable antagonism or conflict. Although there are few details on the history of cultural production, in both cases the introduction into society of a liminal mentality was accompanied by a flurry of cultural and social innovation including new civic rituals. To gain insight on these transformative phases, we again follow the lead of Turner (1957, 1969, 1988) who saw how ritual could minimize the negative outcomes of challenging moral dilemmas and potential conflicts. Through the enactment of periodic rituals, Turner notes, society's multivocality was put on display and honored as a legitimate contribution to the culture as a whole. Dual rituals, enacted and reenacted periodically, accomplished this task by reinstituting the opposed forces, side-by-side, not in blind antagonism, but in a way that allows participants to reflect on the transcendent, conscious unity basic to a society's principles. As (Turner, 1969, p. 84) expressed it, dual rituals honor both principles and reenergize the idea that they are “a play of forces instead of a bitter battle”.

Periodic rituals in classical Athenian culture

Regularly scheduled state-sponsored rites were frequent in the Athenian polis, but two, the Panathenaea and the Great Dionysia, stood out for their elaborateness and their broad participation. The Panathenaea honored Athena Polias, the Athenian patron goddess, while the Great Dionysia, held during a month named after Artemis, celebrated the advent of Dionysus into the urban center, and, by extension, the liminal impulse, into Athenian society. The Panathenaea celebrated Theseus, an historical king who unified Attica, and who, with Athena, had “triumphed over the forces of evil” (Parker, 2006, p. 255). Male athletic contests and chariot and horse races were nods to the individual glory of the ancient warrior-kings, ignoring the fact that contemporary warfare depended primarily on commoners who made up the hoplite phalanxes and rowed the warships (p. 263). Hierarchy, misogyny, and traditional male prestige were made evident in processions that showed women, girls, and foreigners (metics) in servile statuses.

The theme of the Great Dionysia was not to honor ancient origins, instead it addressed the moral dilemmas that attended rapid social and cultural change in the direction of a more egalitarian society, for example, those surrounding female identity (Zeitlin, 1990). The rite openly celebrated the enhanced egalitarianism, for example, when citizens drank wine together with foreigners and slaves (slaves were not allowed to attend the Panathenaea); Cartledge (1985, p. 120) notes that “even prisoners were released from custody on bail.” The rite also alluded to how Athenian society could be seen as a kind of family in the parade of orphaned young men whose fathers had perished in battle, and who had been raised and trained at the polity's expense (Goldhill, 1990, p. 123). The Great Dionysia concluded with a multi-day phase of contests between poets and the actors and choruses who performed in comedic and tragic plays. Isegoria (free speech), a key building-block of Athenian democracy (e.g., Ober, 2007, p. 95), was foregrounded in the comedic plays that, as described by Parker (2006, p. 150–152) and Bertelli (2013), ridiculed the elite, the democracy, and even Dionysus, portrayed by Aristophanes in one play as a coward and braggart. The tragic dramas focused on current moral and political dilemmas presented by living in a democracy but in some ways still constrained by a persistent gender inequality and differences in access to status, wealth, and even political power in a society in which some persons harbored notions that an elite should be accorded privileges and respect based on birthright (Ober and Straus, 1990, p. 249–252, passim). For example, Evans (2010, p. 197) describes how the tragedies “enabled Athenians to peer inside the experience of peoples who had little power... [placing them]… in critical circumstances where their abilities to act and react were severely limited...”

Annual rituals in the Aztec capital

Although secondary centers hosted ritual events of their own, Tenochtitlan, the capital center, was the site of the most opulent and costly in the empire (Berdan, 2017). The rites were conducted in a highly accessible and beautifully constructed elevated platform 340 m by 360 m that was the principal architectural feature of the capital and could host 8,000 to 10,000 persons for major ritual gatherings (López Austin and López Luján, 2017, p. 607, 612). Of the complex sequence of annual rites, the Quecholli and the following Toxcatl and Etzalcualiztli served most directly as a way to honor Chichimec influence on the emerging Aztec culture (this summary draws primarily from van Zantwijk, 1985 and Bernal-García, 2007). The Quecholli, staged during the final month of the dry season in a desert-like setting in the ceremonial center, celebrated the Chichimec origins of the Mexica rulers of the Aztec empire, for example, when the ruler led a procession out of the city along a path strewn with pine needles to a mountain-top shrine at the edge of the region. The ritual sequence celebrated both liminal and structural elements of a complex society, and illustrated how the two were connected when, during the following Toxcatl phase, Tezcatlipoca's effigy was destroyed to hasten the advent of Huizilopochtli, the principal symbol of a unified empire governed by Chichimec (Mexica) rulers who had adopted many elements of Nahua-Toltec culture.

Thus, the transition from Quecholli and Toxcatl to the fertility themed Etzalcualiztli centered on Huizilopochtli can be understood as a metamorphosis between two states of being of Tezcatlipoca and the Chichimec peoples. As Bernal-García (2007, p. 108) put it, at “...the desert garden the Mexica began to retrace their hazardous migration from Aztlan to the Basin of Mexico... [which]... miraculously turned unorganized time and formless space into precise calendars, defined geographical places, and urban organization.”

Commentary on the creation of institutions for equitable and incorporative governance

Plato identified art as a “dangerous force” that has a “disruptive and capricious power” that should be “subordinated to the claims of society” (quoted in Thomas, 2021, p. 21, 34).

It is of considerable theoretical interest to note that, in both Athens and Aztec, it was liminal-inspired agency and innovativeness that brought institutional and cultural challenges to structural normativity and thus provided the cultural foundations for highly collective governance. To make this point in the case of Athens, we point to artistic innovation, most notably the famous tragedies and comedies of the Great Dionysia (Meier, 1993) that were instituted even though not highly regarded by some elite, as Plato indicates. The significance of these performances in Athenian cultural design is attested to by the considerable investment made in building a performance space for them, a stone-constructed theater that would hold an estimated 17,000 persons seated in a bowl-shaped half-circle designed to maximize audience intervisibility and thus allow participants to gauge the reactions of other viewers to the performances (Ober, 2008a, p. 201). In the Aztec case, liminal creativity is also evident, but less in artistic effort, although the annual ritual events at the capital took place in an elaborately constructed space and displayed considerable performative quality evident in the colorful costuming and other elaborate material culture. The heart of Aztec innovation, as we see it, was more in the form of new institutions that underpinned egalitarian governance in state and marketplace. For one, we know that the subculture of the great marketplace of Tlatelolco, governed by commoners, was a liminal domain where normative culture was challenged (Hutson, 2000). The egalitarianizing impetus is also evident in the presence of governing councils that included commoners recruited based on meritorious acts (e.g., Davies, 1987, p. 114, 115), and in a culture of judicial equity and accountable judges (Offner, 1983, p. 113, 242, 251). Key players behind these innovative ideas about governance were the Chichimec leaders of the Acolhua polity, most notably the ruler Nezahualcoyotl. He demonstrated the Chichimec sensibility by centering “legal and political power in the office of the...ruler...[yet]...he encouraged participation by the various classes and subgroups in the empire's legal and political processes in order to minimize discontent and alienation” (Offner, 1983, p. 123). We would also point to the example of Tlaxcallan, that illustrated elements of Aztec culture but remained independent of the Aztec Empire, where Tezcatlipoca was honored and that featured a unique (to Mesoamerica of the period) political architecture in which commoners, not royal lineages, provided the polity's principal leadership in the form of a governing council made up of persons who were recruited based strictly on ability—a democratic republic (Fargher et al., 2010, 2022).

Unintended outcomes of collective action: unleashing of the social energy of political collective action and an engaged citizenry

As we have demonstrated, in addition to hypothesis-testing, cross-cultural comparative analysis has allowed us to widen the aperture of collective action theory to discover aspects of collective state-building not previously addressed or not well-theorized. We include in these findings evidence that contingent mutuality and cooperation were undergirded by institutional and cultural policies and practices that expanded opportunities for persons to engage in a broad range of cooperative interactions beyond the local scale and beyond social and cultural divisions. Our data also point to advantageous outcomes of cooperative problem-solving that spurred what we call social energy. This process, we suggest, is similar to Levi's “virtuous circle” but expands her definition beyond compliance to include other outcomes of collective action that benefited citizens and generated new sources of revenue for state-building. We see social energy in the expanded economic opportunities provided by the growth of marketplace economies, the tendency toward population growth and urbanization, an increased material standard of living for commoners, and the intensification of rural production.

Population growth and urbanization

Not only is there a positive correlation between collective action and total population size, we found the more collective polities also tended to exhibit a relative increase in urbanism during their respective focal periods, a result, in part, of bureaucratic elaboration (Table 2. c). Urbanization was accompanied by overall population growth, unlike the more autocratic polities in the comparative sample that more often exhibited no growth or even population loss (Table 2. d; and often incurred considerable costs to inhibit exit or retrieve those who had exited). In our discussion of the possible reasons for this marked growth differential (Blanton and Fargher, 2008, p. 278–280), we noted that not only did the more autocratic systems suffer outmigration, often the more collective states were sites of immigration of displaced or uprooted persons. It is also possible that in the more collective states, the greater availability of urban and rural public goods including enhanced food security, clean water and sanitation in cities, resulted in either higher birthrates or lower mortality, or both, but demographic measures to evaluate either hypothesis are not available across the sample.

Material standard of living and intensification of production

Another factor possibly influencing differential population growth is that political collective action tended to result in higher material standards of living for common persons during the focal periods (Table 2. e; and was in evidence in both Athens; Morris, 2005; Ober, 2010, and in Aztec; Smith, 2016, p. 56–66). The reasons for this outcome are highly complex and not well-understood, although in some cases resulting from growing marketplace economies and good government policies including the expansion of public goods and the enhanced opportunities for social mobility presented by open recruitment to positions of governing authority. We also noted that, in the more collective polities, rural households and communities were motivated to intensify production, a process, we suggest, that illustrates an increased willingness to comply; Blanton et al., 2021).

Discussion

Anthropologists who incorporated collective action theory into their research designs found new ways to comprehend the sources of variation in premodern governance, including state formation. The major finding, that collective action was a foundation for premodern state-building in diverse world areas and in the context of diverse cultural frames, is a powerful challenge to outworn Eurocentric grand narratives that imagined a sharp divide between Occidental and Oriental polities and mentalities, thus expanding on a critique of Western social science first envisioned by Said (1978).

Collective action theory also throws new light on other issues that have engaged Western political philosophy, including the question: Who should hold the sovereign power to govern society, a despot or a popular sovereignty of the people? To persist in asking this question, however, as Kelly (2016, p. 275) notes, is futile because attempts to answer it are akin to the problem of squaring a circle: it can never be solved to everyone's satisfaction. We see this question as a faulty understanding of the nature of political power also because, when the central social fact of a polity is a mutual, although contingent, bond of obligation between the leadership and citizens, there will be no clear center of political power, either despot or the people. Ober (2008b; cf. 1997) made this point about distributed power when he wrote about Classical Athens, where the shift to a more democratic form of governance was not a case where the common people took control of the institutions of governing authority, although some members of a disgruntled elite rhetorically claimed they did. Instead, governing authority was in the hands of citizen council members and magistrates chosen by lot or election to serve limited terms of office. While by no means perfect (males held all positions of authority), this system was at least partially democratic given the considerable sway that commoners and elite alike possessed for freedom of speech, the ability to participate in governing councils, to serve as magistrates, to attend civic events, and to participate in (as jurors) and make use of a citizen-driven legal system that could punish even governing officials for public malfeasance.

Collection action theory also brings into question other claims about democracy and its sources, for example, that a democracy's policies must represent the “general will” of the people, implying that citizens, unlike contingent cooperators, are unable or unwilling to change their opinions or actions. By contrast, collective action theory points to the importance of the building of and sustaining of palpably successful institutions to foster social comingling and cooperative alignments that weaken social divides while building governing institutions that enhance the common good. This is a process whereby political action fosters a new general will.

Research inspired by collective action theory has brought with it other sources of new thinking. For example, a key research question for our discipline has been: What caused the emergence of social complexity late in the history of our species?

Historically, the issue of ultimate causality has focused on various, usually materialist, “prime movers” or “primary engines,” including technological innovation, demographic pressure and competition for resources, large-scale irrigation, commercial growth, and warfare, among others. Only historical and field research will provide final answers to questions about causality, yet our statistical analyses of cross-cultural data provide some interesting insights that invite research attention. For one, the comparative sample of societies we discussed brings traditional prime mover theorizing into question given the great variety of environmental, agroecological, technological, demographic, social, and cultural conditions in which collective or other forms of state-building took place, and in the diverse geographies of East Asia, South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, pre- Hispanic Mesoamerica, and, of course, the Mediterranean and Europe (Blanton and Fargher, 2008). Further, at least in cases where the emergent form of governing complexity leaned more to collective action, the statistical results we report are consistent with the possibility that the changing social formations themselves were important generative forces for material change, including the growth of marketplace economies, population growth, urbanization, and the intensification of production. This scenario need not imply the absence of external prime movers, rather it implies that episodes of state formation likely involved the interaction of multiple intertwined variables rather than linear causality by particular prime movers.

The fact that collective action theory incorporates the possibility of a human conditional cooperator into its suite of testable hypotheses is key to how it differs from earlier explanatory frames including coercion theory or notions of a general will of the people. The notion of a conditional cooperator also serves as a corrective to the restrictive claims of evolutionary psychologists who argue that biological natural selection in the deep human past equipped us with cooperative and norm-following instincts (e.g., Gintis, 2012), denying the possibility of contingent cooperation and constituting a not-so-subtle libertarian argument against the need for governing institutions (McKinnon, 2005; Blanton and Fargher, 2016, p. 9–28). Collective action theory is better suited as the beginning point for hypothesis testing about human cooperation because it makes no assumptions about whether humans in general, or members of specific cultural groups or social sectors, have or do not have propensities to behave cooperatively or to instinctively adhere to social norms. Compare this with the prominent evolutionary psychologist Henrich (2015, p. 315–318) who argues that, over human biological history, “natural selection shaped our psychology to make us docile, ashamed of norm violation, and adept at acquiring and internalizing social norms.” Is he serious? If true, none of the heterodox social and cultural transformations that brought about egalitarian collective governance, and that in some cases left endurable historical influence, would have been possible.

Conclusion

Collective action theory provides a path to investigations centered on actual governing practices and their outcomes, an important corrective, we suggest, to purely philosophical or activist discourses that are removed from the empirical reality of human experience. In our case, the theory has supplied us with a trove of testable hypotheses regarding the ways that humans, in premodernity, have overcome or avoided autocracy to imagine social and cultural policies and practices that make it possible for leaders to, in the words of Weber (1978, p. 267), “gain the confidence” of subjects, thus motivating not only their compliance but even, possibly, their desire to honor and celebrate government. Research conducted from a collective action perspective demonstrates that, across time periods and cultural traditions, socially thoughtful human agents consciously found means to identify and resolve cooperator dilemmas and to provide for the common good in ways that unleashed the creativity and transformative economic and political potential of a citizenry. We suggest that there is much to learn from historical episodes like those we have consulted that will provide a cache of varied examples to enrich theory-building and support more reasoned and informed political discourses. What we are suggesting, however, implies that anthropologists, along with other social scientists, should throw off traditional Eurocentric legacies and develop research designs that extend their efforts beyond the traditional disciplinary boundaries and narrow theoretical and methodological preferences.

Author contributions

RB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization. LF-N: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding came from the United States National Science Foundation (0204536-BCS).

Acknowledgments

We thank Cindy Bedell for her numerous and insightful comments on earlier drafts. RB benefitted from resources at the Knight Library of the University of Oregon. Our work on collective action has been enriched by colleagues and coauthors Gary M. Feinman and Stephen A. Kowalewski.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Cross-cultural comparative analysis has a long history of methodological development; a readable introduction is Ember and Ember (2001).

2. ^Problematization as discussed here is unlike “Axial Age Theory” that posits an evolutionary transition from “pagan” to “modern” forms of religion and governance; rather, it is a product of collective action process in state-building (Blanton and Fargher, 2013).

References

Abbott, F. F. (1963). A History and Description of Roman Political Institutions, 3rd Edn. New York, NY: Biblo and Tannen.

Ahlquist, J. S., and Levi, M. (2011). Leadership: what it means, what it does, and what we want to know about it. Ann. Rev. Poli. Sci. 14, 1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-042409-152654

Ali, M. A. (1995). “Towards and interpretation of the Mughal Empire,” in The State in India: 1000–1700, ed. H. Kulke (Delhi: Oxford University Press), 263–277.

Bates, R. H. (1983). Essays on the Political Economy of Rural Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Berdan, F. F. (2017). “The economics of mexica religious performance,” in Rethinking the Aztec Economy, eds. D. L. Nichols, F. F. Berdan, and M. E. Smith (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press), 130–155.

Bernal-García, M. E. (2007). “The dance of time, the procession of space at Mexico-Tenochtitlan's desert garden,” in Sacred Gardens and Landscapes: Ritual and Agency, ed. M. Conan (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections), 69–112.

Bertelli, L. (2013). “Democracy and dissent: the case of comedy,” in The Greek Polis and the Invention of Democracy: A Politico-Cultural Transformation, eds. J. P. Arnason, K. A. Raaflaub, and P. Wager (Oxford: John Wiley and Sons), 99–125.

Bettini, M., and Short, M. (2011). The Ears of Hermes. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Press.

Blake, S. P. (1991). Shahjahanabad: the Sovereign City in Mughal India, 1639–1739. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blanton, R. E. (1998). “Beyond centralization: steps toward a theory of egalitarian behavior in archaic states,” in Archaic States, eds. G. M. Feinman and J. Marcus (Santa Fe: School of American Research Press), 135–172.

Blanton, R. E. (2010). Collective action and adaptive socioecological cycles in premodern states. Cross-Cult. Res. 44, 41–59. doi: 10.1177/1069397109351684

Blanton, R. E. (2013). “Cooperation and the moral economy of the marketplace,” in Merchants, Markets, and Exchange in the Pre-Columbian World, eds. K. G. Hirth and J. Pillsbury (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 23–48.

Blanton, R. E. (2015). Theories of ethnicity and the dynamics of ethnic change in multiethnic societies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 9176–9181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421406112

Blanton, R. E. (2016). “The variety of ritual experience in premodern states,” in Ritual and Archaic States, ed. J. M. A. Murphy (Gainesville: University of Florida Press), 23–49.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2008). Collective Action in the Formation of Premodern States. New York, NY: Springer.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2010). “Evaluating causal factors in market development in premodern societies: a comparative study, with critical comments on the history of ideas about markets,” in Archaeological Approaches to Market Exchange in Ancient Societies, eds. C. Garraty and B. Stark (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado), 207–226.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2011). The collective logic of premodern cities. World Arch. 43, 505–522. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2011.607722

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2012). “Neighborhoods and the civic constitutions of premodern cities as seen from the perspective of collective action,” in The Neighborhood as a Social and Spatial Unit in Mesoamerican Cities, eds. M. C. Arnauld, L. R. Manzanilla, and M. E. Smith (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press), 27–54.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2013). “Reconsidering Darwinian anthropology: with suggestions for a revised agenda for cooperation research,” in Cooperation and Collective Action: Archaeological Perspectives, ed. D. M. Carballo (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado), 93–127.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2016). How Humans Cooperate: Confronting the Challenges of Collective Action. Boulder, CO.: University Press of Colorado.

Blanton, R. E., Fargher, L. F., Feinman, G. M., and Kowalewski, S. A. (2021). The fiscal economy of good government: past and present. Curr. Anthro. 62, 77–96. doi: 10.1086/713286

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Fargher, L. F. (2020). Moral collapse and state failure: a view from the past. Front. Poli. Sci. 2020:568704. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.568704

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Nicholas, L. M. (2022). Ancient Oaxaca: The Monte Albán State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Booth, W. J. (1993). Households: On the Moral Architecture of the Economy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Brown, N. O. (1947). Hermes the Thief: The Evolution of a Myth. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Carballo, D. M., and Feinman, G. M. (2023). Collective Action and the Reframing of Early Mesoamerica. Cambridge; Cambridge University Press.

Cartledge, P. (1985). “The greek religious festivals,” in Greek Religion and Society, ed. P. E. Easterling and J. V. Muir (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 98–127.

Chambers, D. S., and Pullan, B. (2001). Venice: A Documentary History, 1450–1630. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Chwe, M. S. Y. (2001). Rational Ritual: Culture, Coordination, and Common Knowledge. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Colson, E. (1969). “African society at the time of the scramble,” in Colonialism in Africa, 1870-1960: Vol. 1: The History and Politics of Colonialism, 1870-1914, eds. L. H. Gann and P. Daignan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 27–65.

Connor, R. W. (1996). “Civil society, dionysiac festival and the Athenian democracy,” in Demokratia: A Conversation on Democracies, Ancient and Modern, eds. J. Ober and C. W. Hedrick (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 217–226.

Cook, K. S., Hardin, R., and Levi, M. (2005). Cooperation Without Trust? New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Davies, N. (1987). The Aztec Empire: The Toltec Resurgence. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Dodds, E. R. (1951). The Greeks and the Irrational. Berkeley, CA: The University of California Press.

Eck, W. (2000). “The growth of administrative posts,” in The Cambridge Ancient History, Second Edition, Vol. II The High Empire, A. D. 70-192, eds. A. K. Bowman, P. Garnsey, and D. Rathbone (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 238–265.

Elman, B. (1991). Political, social, and cultural reproduction via civil service examinations in late imperial China. J. Asian Stud. 50, 7–28. doi: 10.2307/2057472

Evans, N. (2010). Civic Rites: Democracy and Religion in Ancient Athens. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Fargher, L. F., and Blanton, R. E. (2021). “Peasants, agricultural intensification, and collective action in premodern states,” in Power from Below in Premodern Societies: The Dynamics of Political Complexity in the Archaeological Record, eds. T. L. Thurston, and M. Fernández-Götz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 157–174.

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., and Antorcha-Pedemonte, R. R. (2019). The archaeology of intermediate-scale socio-spatial units in urban landscapes. In special issue: excavating neighborhoods: a cross-cultural exploration, eds. D. Pacifico and Lise A. Truex, 159-179. Arch. Pap. Am. Anthro. Assoc. 30, 159–179. doi: 10.1111/apaa.12120

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., and Espinoza, V. H. (2010). Egalitarian ideology and political power in prehispanic central Mexico: the case of Tlaxcallan. Lat. Am. Ant. 21, 227–251. doi: 10.7183/1045-6635.21.3.227

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., and Espinoza, V. H. (2017). “Aztec state-making, politics, and empires: the triple alliance,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs, eds. D. L. Nichols and E. Rodriguez-Alegría (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 143–160.

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., and Espinoza, V. H. (2022). Collective action, good government, and democracy in Tlaxcallan, Mexico: an analysis based on demokratia. Front. Poli. Sci. Comp. Gov. 2022:832440. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.832440

Farooque, A. K. M. (1977). Roads and Communications in Mughal India. Delhi: Idarah-i-Adapiyat-I Delli.

Fei, S.-y. (2009). Negotiating Urban Space: Urbanization and Late Ming Nanjing. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Feinman, G. M. (2016). “Variation and change in archaic states: ritual as a mechanism of sociopolitical integration,” in Ritual and Archaic States, ed. J. M. A. Murphy (Gainesville: University Press of Florida), 1–22.

Feinman, G. M. (2023). Reconceptualizing archaeological perspectives on long- term political change. Ann. Rev. Anthro. 52, 347–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-060221-114205

Feinman, G. M., Blanton, R. E., Kowalewsi, S. A., and Navarro, L. F. (2022). Origins, foundations, sustainability, and the trip lines of good governance: archaeological and historical considerations. Front. Poli. Sci. 2022:3. doi: 10.3389/978-2-8325-0173-3

Galinier, J., Mecquelin, A. M., Bordon, G., Fontane, L., Foumaux, F., Ponce, J. R., et al. (2010). Anthropology of the night: cross-disciplinary investigations. Curr. Anthro. 51, 819-847. doi: 10.1086/653691

Galsterer, H. (2000). “Local and provincial institutions and government,” in The Cambridge Ancient History, Second Edition, Vol. II: The High Empire Period, A.D. 70- 92, eds. A. K. Bowman, P. Garnsey, and D. Rathbone (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 344–360.

Gintis, H. (2012). “Role of cognitive processes in unifying the behavioral sciences,” in Grounding Social Sciences in Cognitive Sciences, ed. R. Sun (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 415–443.

Gluckman, M. (1941). Economy of the Central Barotse Plain. Livingston, NR: The Rhodes-Livingston Papers, 7.

Gluckman, M. (1961). “The Lozi of Barotseland in North-Western Rhodesia,” in Seven Tribes of British Central Africa, eds. E. Colson and M. Gluckman (Manchester: Manchester University Press), 1–93.

Goldhill, S. (1990). “The great dionysia and civic ideology,” in Nothing To Do With Dionysos? Athenian Drama in its Social Context, eds. J. Winkler and F. I. Zeitlin (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 97–129.

Goldhill, S. (2000). Civic ideology and the problem of difference: the politics of aeschylean tragedy once again. J. Hell. Stud. 120, 34-56. doi: 10.2307/632480

Grover, B. R. (1994). “An integrated pattern of commercial life in the rural society of North India during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries,” in Money and Markets in India, 1100–1700, ed. S. Subrahmanyam (Delhi: Oxford University Press), 219–255.

Gulick, C. B. (1973). The Life of the Ancient Greeks, With Special Reference to Athens. New York, NY: Cooper Square Publishers.

Hansen, M. H. (1999). The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes: Structure, Principles, and Ideology. Second Revised Edition. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Hanson, V. D. (1999). The Other Greeks: the Family Farm and the Agrarian Roots of Western Civilization, 2nd Edn. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hasan, I. (1936). The Central Structure of the Mughal Empire and its Practical Working Up to the Year 1657. London: Oxford University Press.

Hechter, M. (1990). “The emergence of cooperative social institutions,” in Social Institutions: Their Emergence, Maintenance, and Effects, eds. M. Hechter, K. D. Opp, and R. Wippler (New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter), 13–33.

Henrich, J. (2015). The Secret of Our Success: How Culture is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton, NY: Princeton University Press.

Heyden, D. (1991). “Dryness before the rains: toxcatl and tezcatlipoca,” in Aztec Ceremonial Landscapes, ed. D. Carrasco (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado), 188–204.

Hitchner, R. B. (2005). “The advantages of wealth and luxury,” in The Ancient Economy: Evidence and Models, eds. J. G. Manning and I. Morris (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press), 207–222.

Ho, P-ti. (1962). The Ladder of Success in Imperial China: Aspects of Social Mobility, 1368-1911. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Hucker, C. O. (1998). “Ming government,” in The Cambridge History of China, Vol 8: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 2, eds. D. Twitchett and F. W. Mote (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 9–105.

Hutson, S. R. (2000). Carnival and contestation in the aztec marketplace. Dialec. Anthro. 25, 123–149. doi: 10.1023/A:1011058318062

Jameson, M. H. (1997). “Religion in the Athenian democracy,” in Democracy 2500? Questions and Challenges, eds. I. Morris and K. A. Raaflaub (Boston, MA: Archaeological Institute of America: Colloquia and Conference Papers 2), 171–195.

Kelly, D. (2016). “Popular sovereignty as state theory in the nineteenth century,” in Popular Sovereignty in Historical Perspective, eds. R. Bourke and Q. Skinner (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 270–296.

Korotayev, A. V. (1995). “Mountains and democracy: an introduction,” in Alternative Pathways to Early State, eds. N. N. Kradin and V. A. Lynsha (Vladivostoc: Dal'nauka), 60–74.

Langlois, J. D. Jr. (1998). “Ming law,” in The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 8: The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644, Part 2, eds. D. Twitchett and F. W. Mote (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 172–220.

Levi, M. (2022). Trustworthy government: the obligations of government and the responsibility of the governed. Daedalus 141, 215–233. doi: 10.1162/daed_a_01952

Levick, B. (1996). “Senators, patterns of recruitment,” in The Oxford Classical Dictionary, eds. S. Hornblower and A. Spawforth (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1387–1388.

López Austin, A., and López Luján, L. (2017). “State ritual and religion in the sacred precinct of tenochtitlan,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs, eds. D. L. Nichols and E. Rodríguez-Alegriá (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 605–621.

Maffie, J. (2014). Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

McKinnon, S. (2005). Neo-Liberal Genetics: The Myths and Moral Tales of Evolutionary Psychology. Chicago, IL: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Meier, C. (1993). The Political Art of Greek Tragedy. Trans. Andrew Webber. Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press.

Morely, N. (1996). Metropolis and Hinterland: The City of Rome and the Italian Economy, 200 B. C.-A.D. 200. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moreno, A. (2007). Feeding the Democracy: The Athenian Grain Supply in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BC. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Morris, I. (2005). “Archaeology, standards of living, and greek economic history,” in The Ancient Economy: Evidence and Models, eds. J. G. Mannin and I. Morris (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press), 91–126.

Nicholson, H. B. (2001). Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl: The Once and Future Lord of the Toltecs. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Ober, J. (1997). “Revolution matters: democracy as a demotic action (a response to Kurt A. Raaflaub),” in Democracy 2500? Questions and Challenges, eds. I. Morris and K. A. Raaflaub (Boston, MA: Archaeological Institute of America: Colloquia and Conference Papers 2), 67–86.

Ober, J. (2006). From epistemic diversity to common knowledge: rational rituals and publicity in democratic Athens. Episteme 3, 214–233. doi: 10.3366/epi.2006.3.3.214

Ober, J. (2007). “'I besieged that man': democracy's revolutionary start,” in Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece, eds. K. A. Raaflaub, J. Ober and R. Wallace (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 83–104.

Ober, J. (2008a). Democracy and Knowledge: Innovation and Learning in Classical Athens. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.