- Bremen International Graduate School of Social Sciences (BIGSSS), University of Bremen and Constructor University Bremen, Bremen, Germany

Computational approaches have grown in prominence amidst advancements in new media and technologies and ever-increasing amounts of digital data. This article critically examines these automated techniques, especially the analytical affordances and concerns that such methods introduce to the study of online migrant and mobility discourses. The paper further argues for a mixed methodology anchored on social representations theory—a contextually sensitive framework that enables reflexive use of computational approaches, i.e., quantitatively analyze but also explore different layers of cultural and linguistic meanings in online diasporic interactions. With Filipino migrants in Germany as a case study and partner community, the study then demonstrates the combined application of topic modeling and ethnographically inspired qualitative analysis on migrant posts in Facebook. The findings are discussed in the form of a cultural reflection on Filipino values and expectations and an advocacy for mixed methodologies grounded on critical, social, and practice-oriented theories.

1 Introduction

‘When I use a word,' Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean–neither more nor less.'

‘The question is,' said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean different things–that's all.'

‘The question is,' said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master–that's all'

– Caroll (1902, p. 117)

The excerpt above from Lewis Caroll's classic book “Through the Looking-Glass” shares a simple yet sometimes taken-for-granted insight about language and meanings that can be interpreted as follows: the value of words or utterances is not only based on their denotative sense or definition in a dictionary (i.e., semantics), but also based on their context or as words are deployed in talk (i.e., pragmatics). Yet in an increasingly digitized world where millions of data are generated every minute through new media technologies (Jenik, 2021), the multilayered meaning of words can easily be forgotten, neglected, or even distorted.

Such can be the case with studies on minority and vulnerable groups, like migrants and their use of social media. On the one hand, Western-centric views, mass media depictions, and host society representations still dominate migration and mobility scholarship (Smets et al., 2020). Given these hegemonic discourses and the deluge of online data, migrants' culturally rich expressions and shared meanings may easily be overlooked. On the other hand, the use of digital (big) data and analytics has become a trend. Although these novel methods are a welcomed innovation, they also introduce potential risks. For instance, migrants' complex realities may become “datafied” (Leurs and Shepherd, 2017) or oversimplified because of “big data positivism” (Fuchs, 2017).

Against such backdrop, this article first looks briefly into the analytical benefits and risks presented by computational methods, especially automated content methods used on textual online data. The paper then proposes a reflexive computational approach to address “datafication” concerns—by advocating a mixed methodology anchored on a critical, social psychological theory to enable socially meaningful and contextually sensitive migration and mobility studies. Lastly, the article presents an empirical study involving Filipino migrants in Germany to illustrate the proposed reflexive approach to diasporic discourse in Facebook.

2 Computational methods and analysis of discursive content

Computational methods have risen in prominence together with advancements in digital technologies (especially social media) and the generation of unprecedented amounts of online data (i.e., big data). Text mining methods such as natural language processing and machine learning have become popular especially for conducting automated analysis of a large collection (i.e., corpus) of text.

Various state-of-the-art methods for automated content analysis exist, and a few will be discussed briefly. Much like manual content analysis, dictionary and rule-based methods enable a straightforward count of words that are considered a measure of a specific category or feature (van der Meer, 2016; Hase, 2023). A word can be the studied feature itself, such as the occurrence of “terrorism” in media coverage of Islam (Hoewe and Bowe, 2021, as cited by Hase, 2023, p. 26). Other studies analyze a list of features—or a dictionary (Hase, 2023). Dictionaries function like a manual codebook and are popular in identifying pre-defined categories such as emotions or positive and negative sentiments in text. The primary downside with dictionaries is that they are usually customized to a specific topic, type of text, or language (Hase, 2023) and so are seldom validated (van der Meer, 2016). In contrast, supervised methods enable easier validation (van der Meer, 2016). An abundant set of texts is manually coded according to a codebook of categories to create a training dataset. A computer algorithm then uses this training dataset to “learn” how to classify a different dataset into the same predefined classifiers (van der Meer, 2016; Hase, 2023). The limitation of using supervised methods is that it entails a huge amount of manual labor and texts for machine learning. There is also the question of how applicable the classifiers are on another kind of text, dataset, or topic domain (Hase, 2023). Lastly, unsupervised methods enable the detection of naturally occurring categories in text. In contrast to previous methods, unsupervised machine learning presents a “more inductive ‘bottom-up' approach” (Hase, 2023, p. 27). Features or topics are identified without prior assumptions, like in traditional thematic analysis. More importantly, unsupervised methods accommodate the similarity of words (e.g., in terms of frequent co-occurrence) and the multiple semantic usage of words (i.e., words can have different meanings and thus be classified into different categories) (van der Meer, 2016; Hase, 2023). Among the popular unsupervised techniques is topic modeling–the chosen computational method for this study. This will be discussed in detail in the Methodology part.

On the one hand, these automated content methods enable “more systematically reliable, and therefore more replicable” content analysis (van der Meer, 2016, p. 953). Human subjectivities are minimized in the process of parsing through massive amounts of data that would otherwise be tedious and costly for manual coding and analysis (van der Meer, 2016). Computational methods can thus present an alternative, complementary view for analyzing data (e.g., see Baumer et al., 2017). On the other hand, computational results are largely decontextualized, as data are reduced to small units of analysis (e.g., individual words or co-occurring keywords or phrases). Migrant narratives are further reduced to the identified keywords or key topics, which poses the threat of simplified and “datafied” migrant realities (Leurs and Shepherd, 2017). Results may also end up “wrong and misleading”, especially when the method and results do not align with the theories applied or concepts being studied (van der Meer, 2016, p. 953). Thus, the sole use of such computational methods can limit the understanding of migrant and mobility data to statistical and lexical aspects, or even lead to conceptually irrelevant or inaccurate results.

To counter and prevent such pitfalls, several scholars advocate an “ethics of care” (Leurs, 2017; also see Leurs and Prabhakar, 2018; Sandberg et al., 2022). The approach emphasizes relationality, critical human-centeredness, and social justice orientation throughout the conduct of studies (Leurs and Ponzanesi, 2018; Candidatu et al., 2019). This practice has been applied mainly using qualitative and ethnographic methods, which enable equal attention to online and offline realms of interaction (i.e., “non-digital-centric-ness,” Pink et al., 2016). Such techniques can bolster the interpretability of automated methods by incorporating supplemental information absent in the text corpus, e.g., “researcher's complex contextual knowledge” (Baumer et al., 2017, p. 1406). Other studies also adopt ethnographic principles of reflexivity, situatedness, and active collaboration, such as the “Reflexive Data Science” methodology proposed by Hirsbrunner and colleagues in the conduct of AI-related research (Hirsbrunner et al., 2022). The recent work by Dedecek Gertz (2023) also provides an excellent example for a detailed ethical reflection on the application of topic modeling on migrants' social media data. Overall, combining computational analytics with qualitative methods and reflective practices promotes a “caring” management of migrants' digital narratives, traces, and interactions (Sandberg et al., 2022).

However, an extended ethics-of-care practice would be grounding research methodologies and analysis in critical, social theories (Fuchs, 2017) or practice-oriented frameworks (Pentzold, 2020). Doing so not only propels “interdisciplinary dialogue” (Leurs, 2022, p. 231) in migration and mobilities research; it also anchors the use of computational methods on (social) media discourses to theories of society, collective agency, and mediated practice (Pentzold, 2020; Pentzold and Menke, 2020).

This article illustrates such a comprehensive, two-pronged ethics-of-care approach: (1) applying a mixed methodology of topic modeling and qualitative analysis and (2) grounding the analysis in the ideas of social representation, pragmatic communication, and context. These are all tackled in the next sections.

3 Social representations, communication, and context

Social representations (SR) are structured systems of beliefs, values, associations, and practices that people share as members of a community. SR emerge as a form of collective and social psychological coping (Wagner et al., 1999) when people encounter and make sense of novel or “unfamiliar” social objects or phenomena (Moscovici, 2001). These social objects can be tangible things (e.g., AI or robots), topics (e.g., climate change), events (COVID-19 infection, social distancing), social groups (e.g., Muslims or migrants) or organizations (e.g., Hamas). In other words, SR are a community's “common sense” knowledge (Moscovici, 2001, 2008) about objects and experiences as members engage in different levels of everyday interaction (Duveen and Lloyd, 2010).

This article focuses on the social object of migration—an unfamiliar and rather disruptive yet significant “phenomenon that people must make sense of as they encounter it, whether as lived experience, discourse, or both” (Umel, 2023, p. 770). It is an ever-relevant social issue yet acquires different meanings depending on the context by which it arises (e.g., during the EU migration crisis in 2015–2016), on the discursive medium (e.g., mass media vs. social media), or on the social groups involved (e.g., asylum seekers vs. migrant workers vs. host society members).

The paper investigates SR of migration as “a set of concepts, statements and explanations originating in daily life during inter-individual communications” (Moscovici, 1981, p. 181). Specifically, the empirical part later explores a migrant community's collective understanding of the diasporic life through daily exchanges in Facebook's group platform.

Nevertheless, SR do not simply arise from a set of words employed in interactions. As the SR theory's proponent, Serge Moscovici, elucidates:

[R]epresentations are only very partially conveyed by the meanings of a sentence. This is because of the presence of a context that deflects our interpretations as we, the speakers, try to understand them… [T]ake more interest in pragmatic communication (Moscovici, 1994, p. 165; emphasis mine).

What Moscovici (1994) refers to as the pragmatic dimension in SR involves how people deploy language to imply or transform meanings. This is seen through various factors influencing the communicative value of utterances, such as interlocutors' choice of words or phrases, (explicit or implicit) intentions, affective tones, (cultural) connotations, and implications (Moscovici, 1994).

Pragmatic communication enables another layer of analysis of discursive data and, eventually, SR in at least two ways. One, pragmatic features provide added information (e.g., affective meanings, latent connotations or meaning potentials) embedded in exchanges. Pragmatic communication thus elucidates how context impacts the way social knowledge about a phenomenon is constructed in dialogue (Marková, 2008). Two, pragmatic communication relates to how SR have the essential character of presuppositions—or assumptions external to the linguistic structure of utterances—that are taken for granted yet carried by participants with them and applied into conversations (Moscovici, 1994; Kalampalikis and Moscovici, 2005).

An example from Umel's (2023) study exhibits a Filipino participant's description of some newcomer migrants as “feeling like a frog. You would think they have been here in Germany for 100 years” (p. 779). The semantic meaning does not make much sense and we have no way of knowing what it feels like to be such an amphibian. However, the discursive value and impact of the utterance becomes clear when interpreted in the context of the migrants' discussions and within the network of meanings of Filipino cultural values and expectations. The utterance has the multi-layered meanings of “strong disapproval and dislike,” “colloquial insult to someone's beauty, that is, to feel or be like a frog is to be ugly,” admonishment of one's “lack of'beauty-of-will',” and rejection of claim to superiority among co-ethnics in Germany (p. 779–780).

As the example above illustrates, context as it relates to pragmatic communication and shared knowledge is not limited to the linguistic level. As scholars from communication and media theories further emphasize, people's utterances are not mere “sayings” but also “doings”; they are suffused with relationality, agency, and intentionality and are thus performative as much as they are communicative (Pentzold and Menke, 2020). For instance, people do not just negotiate ideas and beliefs about a topic (e.g., climate change) or object (e.g., video of climate change scenarios); people also engage in assessments of credibility and co-creation of an imagined future (Hirsbrunner, 2021).

Other levels of context are hence relevant, such as the individual and relational histories of subjects and the social-cultural-political backdrop in which actors and interactions are situated (Howarth, 2006). By doing so, the SR approach embraces the complexity of social phenomena, including the possibilities of negotiation and resistance in different levels of meaning-making (Duveen and Lloyd, 2010; Howarth, 2011).

From this social representational lens and understanding of pragmatic and contextual aspects of communication, the next section operationalizes the study's mixed methodology for studying migrant discourse on social media.

4 A reflexive computational approach to diasporic discourse

This study's reflexive computational methodology mainly borrows from social representational research and communication studies that give attention to lexical contexts and pragmatist readings of online discourse. In particular, parts of discourse such as textual units of analysis (i.e., words, phrases, statements, etc.) are considered “language use instantiations of the SR” under study (Chartier and Meunier, 2011, p. 37.11). Clusters of words or parts of discourse that share similar lexical traits based on collocation or co-occurrence patterns correspond to what are called “lexical worlds” or lexical classes (Reinert, 2003). In topic modeling, each topic would be considered a lexical class and would in turn form the “basic nuclei of [a] social representation” (Lahlou, 1996, p. 3).

Computational methods enable the detection of such lexical worlds (Flick et al., 2015). For this study, the automated analysis is adapted from Chartier and Meunier's (2011) three-phase approach to text mining for SR. The first phase data collection focuses on “good practice guidelines” (i.e., homogeneity and relevance criteria) in identifying documents that form a study's corpus (Chartier and Meunier, 2011: 37.4). This phase further involves the selection of relevant parts of discourse (e.g., words or phrases) that are thematically relevant to the SR under study. The second phase data modeling marks the use of a software for vectorization, e.g., filtering “empty” or common words like articles, pronouns, and prepositions and assigning weighting values to words. This phase includes similarity calculation, i.e., two text segments or parts of discourse are semantically close to one another when they appear in the text together with similar sets of words. The third phase data analysis comprises three steps. Step One is automatic classification, which involves a text clustering algorithm to group together parts of discourse that share similar lexical features while splitting up those that differ. This step enables “an extensional description of the semantic classes of the discourses in which the SR is embodied” (Chartier and Meunier, 2011, p. 37.30). The present study applies topic modeling for automatic classification and is discussed further in the “Data Analysis” subsection. Step Two involves salient content extraction where the researcher identifies words that best exemplify the core semantic meaning expressed within each class. Step Three is categorization where the researcher interprets and labels the lexical classes through an “abductive inference process” (Chartier and Meunier, 2011, p. 37.33–37.36).

The last phase in Chartier and Meunier's (2011) text mining model—or any computational method—is better treated as the primary step of a reflexive, social scientific analysis. In other words, automated methods are initial, exploratory techniques (Lahlou, 2012), so computational results need further interpretation from the researcher. Clusters of words or topics are only preliminary indicators of which utterances or documents in a text corpus present latent semantic relations or thematic coherence (Baumer et al., 2017). Hence, the application of other software, data sources, or analytical techniques are highly encouraged for triangulation (Lahlou, 2012). For the present study, qualitative techniques were employed for a more meaningful interpretation and in-depth examination of SR of migration. More details are given later in the “Data Analysis” subsection.

4.1 Research questions

This study applies computational and qualitative analyses to explore how Filipino migrants construct their communal ideas of migration in(to) Germany, as reflected in their community interactions on Facebook. Specifically, the empirical part aims to answer the following:

• What are the most salient topics that define the everyday Filipino migrant life in Germany as they are constructed within the migrants' Facebook group?

• Which shared meanings of migration are communicated through these dominant topics?

• How do these SR of migration reflect Filipino cultural values, norms, and practices?

4.2 Fieldwork: participants and data collection

This article is based on the author's digital ethnographic fieldwork and collaboration with Filipino migrants in Germany from May 2016 to June 2017. The researcher made various efforts to build rapport and gain the trust and consent of the partner community. The researcher first met the group leaders and administrators in person, then gained their support and permission in conducting different activities to connect with and get the acceptance of the community members.

The main dataset analyzed here consisted of naturally occurring textual data gathered from the partner Facebook community comprising Filipino migrants temporarily or permanently living in Germany at the time of study. Specifically, the data corpus used for the computational analysis comprised posts written in mixed Filipino, English, and German from the group's Facebook page during online data gathering and participant-observations from January to March 2017. The top 50 posts were saved as PDF files every week and were then encoded into spreadsheets. Only the textual content of the posts was included for analysis. Any identifying information such as usernames and links were omitted. Posts that only contained stickers, images, emoticons, videos, or hyperlinks were excluded. The total number of cases or analytical units was 12,039 posts, originating from 1,329 members. Ethnographic notes and observations were further used to support the qualitative part of the analysis.

4.3 Data processing

For the computer-assisted analysis, this study employs WordStat, a powerful and user-friendly text-mining tool that provides various content analysis and data-mining features such as text processing, clustering, and topic extraction (Provalis Research, 2015; Peladeau and Davoodi, 2018).

To filter commonly used words such as articles and linking verbs, a customized stop word list was created based initially on WordStat's default exclusions lists for English, Filipino, and German languages. Other stop words in the various languages were then added as they were found in the top frequency list. Additionally, a custom-built substitutions list was created so that WordStat recognized and counted at least the top 300 most frequent words and their equivalents in English, Filipino, and German languages as one. Common words in the regional languages, plural forms, other tenses, and gerund forms were also considered.

Some words had similar forms but different meanings in different languages (e.g., “pass” which could either mean “passing an exam” in English or “passport” in German) or in the same language (e.g., “German” could refer to the nationality, the language, or as an adjective). Such words were identified from the frequency list and manually changed (e.g., “pass” used as “Reisepass” or “passport” in German were searched and changed to “passport” instead; “German” used to refer to the language was changed to “Deutsch”) to reduce noise and increase homogeneity.

Raw texts were then separated into single words or tokens. Any word with frequency count < 25 was excluded in the analysis. The output of data pre-processing comprised a “bag-of-words” composed of nouns, adverbs, adjectives, and verbs. From this bag-of-words, a total number of 234,345 words or tokens were analyzed to produce a list of most frequently used terms.

4.4 Data analysis

With its social representational lens, this study assumes that certain shared meanings of diasporic life are reflected in latent focal themes found within the structured collocation of key terms in migrants' online talk. The focus is not simply on frequency of terms but on relationality, i.e., how “meanings do not inhere in symbols (words, icons, gestures) but that symbols derive their meaning from the other symbols with which they appear and interact” (DiMaggio et al., 2013, p. 586–587).

To do so with quantitative precision and reliability, the study employs topic modeling as first part of analysis. Topic modeling or topic extraction is an unsupervised machine learning technique that assists in organizing a collection of unstructured texts based on words that appear together or ‘co-occur'. It produces insightful information based on collocated terms and the latent topical patterns formed by these associated words. Topic modeling also provides information as to which among the themes are more important (i.e., coherence of words within each topic) than others; which keywords and key phrases are more indicative of these themes; and which words differentiate certain topics from the others. Topic modeling assumes that (co-)occurring keyword repertoires “specify the construction of meaning and represent a higher-order structure of texts” (van der Meer, 2016, p. 957). As such, identified topics can serve as a frame (DiMaggio et al., 2013; van der Meer, 2016) or, for the present study, as a marker of social representations of an object or phenomenon. Furthermore, topic extraction allows a part of discourse to be classified into several categories—“a characteristic that more realistically represents the polysemous nature of some words as well as the multiplicity of context of word usages” (Provalis Research, 2015, p. 45). For instance, some Facebook posts can be about several issues in different proportions, or the word “birth” can be associated to marriage requirements topic (e.g., birth certificate), citizenship topic (e.g., nationality at birth), or parental and child benefit topic.

Using WordStat's topic extraction by factor analysis, a principal component analysis with varimax rotation (e.g., Peladeau and Davoodi, 2018) was performed on the dataset. Unit of segmentation was each post or “document”; minimum loading criterion was set at 0.20 to maintain a level of coherence among extracted words for each topic; pruning option was used to remove poorly correlated words; and topic enrichment was applied to benefit from the software's capabilities to detect and suggest spelling corrections, exceptions, and other terms for inclusion. A balance between comprehensive coverage of topics and specificity across themes was aimed for. After comparing several iterations and despite a few topics having just two to four words of significant loadings, a final topic model using factor analysis comprising 25 topics was chosen for analysis.

Given its social representational framework, the case study treats identified topics or patterns of co-occurring parts of discourse as lexical worlds (Reinert, 2003). Each topic serves not only as a cluster of meaning that defines a thematic focus in a social interaction, but as a signpost to a social representation or “way of talking and thinking about the [social] object” (Caillaud et al., 2012, p. 368), which in this study is Filipino migration in(to) Germany.

The second part of analysis involved qualitative techniques based on pragmatic communication (Moscovici, 1994) and discursive storylines (Slocum-Bradley, 2010). This part takes into consideration sociocultural contexts and thus determines what overarching meanings of migration the 25 topics or “signposts” refer to.

Specifically, topics were analyzed and labeled first through a careful reading of the keywords and key phrases. The keywords' factor or topic loadings, the researcher's ethnographic fieldwork, and the researcher's familiarity of the socio-cultural contexts of the participant community were also taken into consideration. WordStat's cluster analysis was then used to identify the topics' natural groupings. These automated semantic clusters were based on how closely words co-occur and relatively significant across topics.

However, some topics seemed to belong better to other clusters. Thus, this study applied the discursive concept of “storylines” to group topics into more meaningful categories. A storyline is the ascribed meaning or interpretation of a series of utterances within a discursive episode (Slocum-Bradley, 2010). In this research, a storyline served as a narrative that contextualized the meaning of keywords, revealed the connection among terms, and thus captured the essence of a topic.

One identifies a storyline through repeated reading of relevant texts. In this study, WordStat's Keyword Retrieval function was used to identify the top 30 “matching hits” or most representative posts for each topic. For the 25 topics, a total of 750 representative sample posts were collected. These representative posts were then used to search storylines that connect the various key terms and individual topics into a reasonably coherent narrative. Identifying the storyline of each topic then enabled the clustering of the 25 topics into five overarching and more meaningful categories. Each overarching category is then treated as a Filipino social representation of migration in(to) Germany and shall be elaborated in the following section.

5 Findings: the everyday online social talk about Filipino migration in(to) Germany

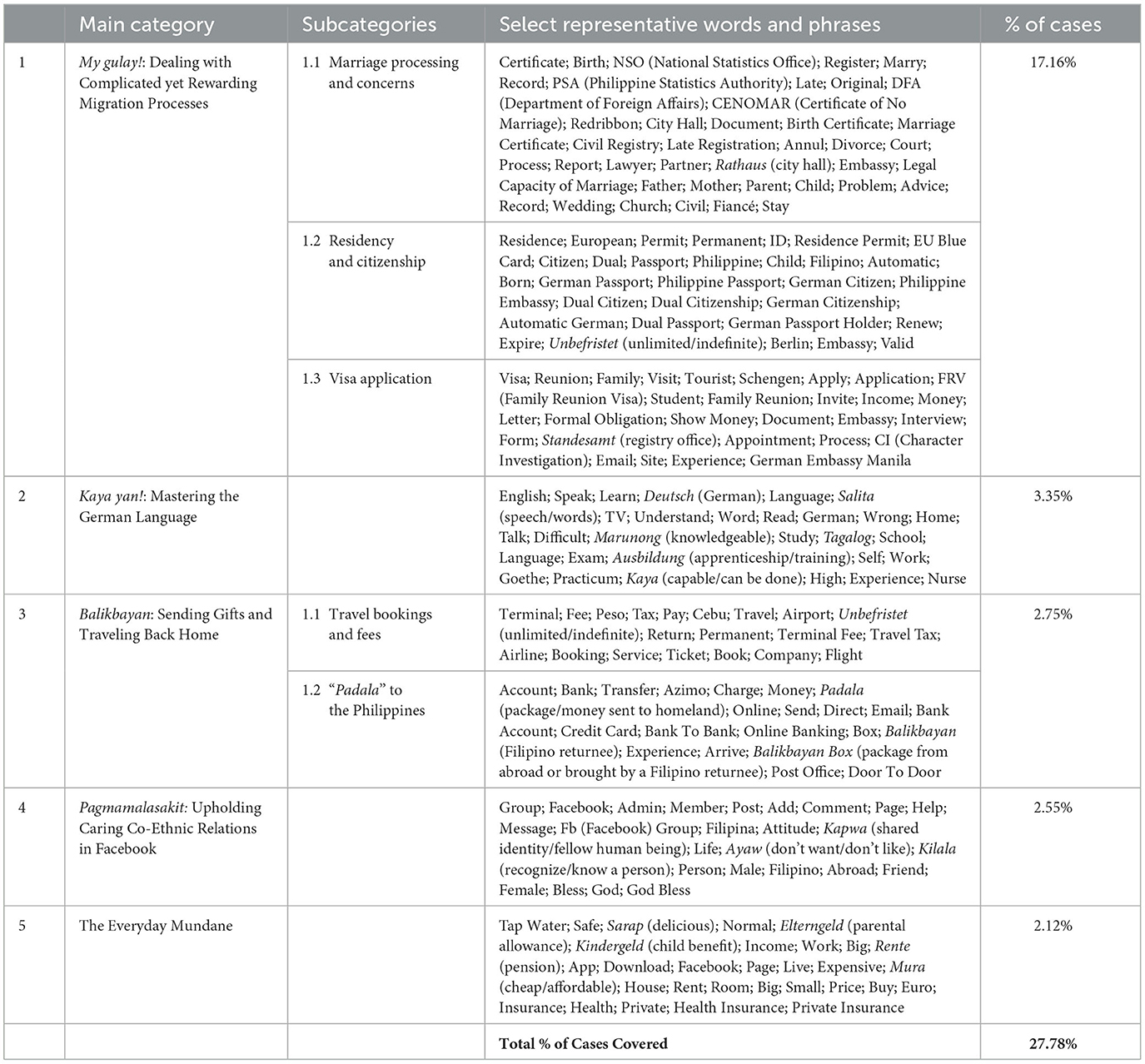

The Filipino migrants' Facebook group talk about relocation to and life in Germany is characterized by five major topic categories, as shown in Table 1. The main clusters are arranged based on percentage of cases covered. Total percentage of cases covered by the five topic categories is ~28% or around one-third of the corpus.

Some keywords identified through topic modeling and emphasized in the qualitative analysis are sustained in their original language forms. In such cases, the original term in Filipino or German is italicized, followed by the English translation in parentheses or brackets.

5.1 My gulay!: dealing with complicated yet rewarding migration processes

The first major topic category represents the biggest theme within the Filipino migrants' Facebook discussions detected by topic extraction. Initial pragmatic analysis shows that this category primarily reflects concerns and experiences during pre-departure and arrival in Germany, particularly the salience of utterances about marriage processing and concerns (1.1), residency and citizenship (1.2), and visa applications (1.3).

Under the Subcategory 1.1., the most salient of these matters is the processing or obtaining of legal documents like birth certificate, CENOMAR (certificate of no marriage), and legal capacity of marriage from various government offices and institutions (e.g., NSO [National Statistics Office], DFA [Department of Foreign Affairs], or embassy). Subcategory 1.1 also references talk related to marital unions and family affairs. On the one hand, this includes questions and advice related to civil or church weddings and (late) registration of marriage. On the other hand, the hiring of lawyers for court issues of annulment, divorce, and child support also emerged prominent.

The Subcategory 2.2 indicates interests or issues of migrants who have been in Germany for some time. Words like permanent, residence permit, unbefristet (unlimited/indefinite), and citizenship in Subcategory 1.2 imply discussions about long-term stays in Germany and the possibility of German naturalization. Talk about German citizenship is not limited to the Filipino migrants alone but especially their kids, i.e., whether children born in Germany are recognized as automatic Germans or dual citizens and thus acquire dual passport and dual citizenship.

The key terms under Subcategory 1.3 imply discussions related to the application of different visa types. Filipinos can apply for a Schengen visa for short stays as a tourist or for a brief visit of a family member. Student visas are available for those aspiring to study in German universities. A family reunion visa (FRV) is applicable for permanent reunion with family members who first gained the right to reside in Germany.

However, a deeper examination of the representative posts reveals more emotional, social, and cultural aspects embedded in the migrants' Facebook group exchanges. Firstly, many keywords refer more to problems, stresses, and nuisances that the migrants had to deal with, especially at initial stages of relocation or family visit. For instance, many posts cited small mistakes committed by government offices, absurd yet preventable circumstances, and the long, grueling process of resolving such issues. To exemplify, here is an extract from a participant's post in the Facebook community:

…[D]oes the German Embassy really need the birth certificate of our parents [for visiting Germany]?... [T]he birth certificate of my mother has wrong spelling, so we had it processed for correction. We waited for 1 year and 5 month[,] my gulay… The Registry Office is too much[.] They didn't even inform my mom that they returned the documents last December from Manila…

The phrase my gulay, which literally means “my vegetables”, was not in the topic extraction results. But this shortened version of an everyday Filipino expression oh my gulay (oh my vegetables) encapsulates a miscellany of meanings and feelings –or as a famous Filipino historian and journalist even stated, “‘Oh my gulay' can be a discourse into our [Filipino] history and culture” (Ocampo, 2019; my emphasis). In the excerpt, the simple phrase captures the Filipinos' preliminary migration experiences and emotions of exasperation, shock, and disbelief—over the absurdity of more than a year's wait for a misspelling correction and over the seeming lack of consideration and competence on the part of the government office involved.

Secondly, exchanges about the topic on annulment and divorce unveil the migrants' difficulties related to these experiences but also the openness of the online community to discuss such delicate issues in a public forum. The Facebook group not only served as a source of social knowledge about the costs and complexities related to divorce and annulment. More importantly, the online community provided a safe space for members going through such sensitive and private concerns. On the one hand, this communal openness can be traced to the contrasting reality that divorce is allowed in Germany while it is prohibited by Philippine law and unaccepted by Philippine Roman Catholic faith. On the other hand, such collective support can be associated with the community leaders' persistent efforts to establish a sense of Filipino solidarity in the Facebook group. More on this point later in the fourth major category (Section 5.4).

Thirdly, other discussions exhibit the migrants' reflections about their gains for successfully entering and staying in Germany. For instance, many posts narrate the migrants' joy for finally reuniting with their German partners. Other exchanges recognized advantages for gaining a German passport and citizenship, such an end to grueling visa application processes just to visit other countries. Another set of posts exhibited migrant deliberations about the benefits of permanent residency in Germany while maintaining Philippine citizenship. The Philippine passport is seen as tangible proof of their enduring connection and contribution to their motherland, as illustrated in another participant's post:

Me, I have been here [in Germany] for 29 years yet I remain a Philippine citizen. I have an unbefristete Aufenthaltserlaubnis [permanent residence permit]… I enjoy everything here… Only that I need to renew my [Philippine] passport every 5 yrs. The cost is high but I just think it's my form of help to the Philippines… [D]o what you want. We have different destinies.

Alternatively, many participants cite their desire and capability to bring their parents to Germany for a visit as an important advantage of living in Germany. For the Filipino participants, inviting their parents to see a foreign land does not only serve as a form of reciprocity or filial duty to repay a “debt of gratitude” [(Kaut, 1961), as cited in Pe-Pua and Protacio-Marcelino (2000), p. 55] toward their parents. Rather, the gesture exemplifies Filipinos' love for their parents and of the desire to show the kind of life that the migrants now have away from the homeland. In other words, the efforts to invite and financially support family visits reflect the centrality of family to Filipinos (Medina, 2001).

Overall, the first topic category underscores a shared idea of Filipino migration in(to) Germany as a complicated, sometimes frustrating, yet rewarding process. Members display a mutual understanding that starting a life in Germany is hard work: one will most likely encounter various emotional, stressful, and absurd situations. Yet once these challenges are overcome, the migrants can enjoy several privileges and access opportunities not just for themselves but for the people they love.

5.2 Kaya yan!: mastering the German language

The second topic cluster centers on the Filipino migrants' experiences of and efforts in learning their host country's language. Filipino migrants shared various learning techniques they use for studying. Among these strategies included watching German TV (television) shows or Youtube videos, even if the words (salita) were difficult to understand. Participants further encouraged reading German books, newspapers, or magazines; not speaking English with one's spouse; and instead speaking strictly in Deutsch (German language) at home despite having wrong grammar or limited vocabulary.

Many exchanges emphasize how German is useful, if not necessary to study in the German schools or universities, to apply for Ausbildung (apprenticeship or training) or Practicum, and to get decent work. Most training and work opportunities require passing a German language exam usually conducted by the Goethe Institute. For instance, Filipinos wanting to work as a nurse in Germany are required to pass a B2 language level exam. The members however assured their fellow migrants through their own experiences that it is possible to pass the language exams even with self-study.

Apart from giving tips and advice, the participants cheered on their fellow members, saying that they have the capability of overcoming the difficulties of learning German:

“Kaya mo yan[,] sis[.] [T]iwala l[a]ng talaga[.]” [You can do it, sis. Just trust (that things work out)].

“[G]oodluck[,] sis... Kaya mo yan...” [Good luck, sis... You can do it…]

The members generously encouraged their fellow Filipinos that if these co-ethnics persevere, they will successfully learn the language. As one participant, Lyanne, shared:

It is difficult but if you are willing to study, you can do it. Study, concentrate, and practice, that's my advice. Always speak German so that you get used to it even if you make mistakes, tell your husband to correct you! Read German, watch German! … [L]earn [the] language with all your heart and you will succeed. God bless.

Overall, the second topic cluster illustrates a collective understanding that living in Germany requires motivation and perseverance to master the German language. Learning German is an undeniably difficult endeavor, yet migrants can expect an abundance of help and encouragement from co-ethnics online. Such discursive displays of social support can be seen as a practice of pakikiramay (to sympathize with) as Filipino migrants share the experience of having to learn a new language. The underlying hope is that such encouragements fortify the fellow migrants' lakas ng loob or inner strength and resolve to survive and thrive in a foreign land.

5.3 Balikbayan: sending gifts and traveling back home

The third major category involves concerns related to the Filipino migrants' visits to the Philippines and their practice of sending gifts back home. On the one hand, discussions involve information exchanges about travel taxes when returning from the Philippines for a visit or vacation. Many participants agreed that Filipinos holding unbefristet or permanent residency in Germany do not need to pay terminal fees when flying out of the Philippine airports. On the other hand, the Facebook group members also shared their experiences and recommendations on airlines and travel agencies or companies that they have tried and would recommend for booking flights or tickets when traveling to and from the Philippines.

On the other hand, discussions revolve around the Filipino concept of padala or anything that a Filipino migrant sends back home. The padala can come in the form of money or packages (balikbayan boxes). Members of the partner community make money transfers via direct bank to bank transfers, online banking, or money transfer websites such as Azimo. Members further swapped information regarding transfer charges and thus compared the most affordable ways to send money back to the Philippines. Padala also refers to the practice of sending balikbayan boxes, literally translated as “repatriate boxes” that are usually delivered door-to-door. Such packages may contain anything that the Filipino migrants deem that their families and relatives back home would like. Examples would be sweets, toiletries, canned goods, toys, clothes, shoes, electronics, and so on.

Overall, this third topic category demonstrates the Filipino migrants' shared idea of diasporic life in Germany as sustaining their connection to home. The Filipino concept of balikbayan captures this practice beautifully as it can refer either (1) to the Filipino migrant as a permanent or temporary “returnee”, or (2) to the packages alone filled with various items sent back home. Nevertheless, both instances carry and connote the tradition and spirit of a “gift” or of “giving” something back to one's loved ones, whether in monetary or material ways or in the form of one's physical presence. These doing (sending money or packages) and being (visits) balikbayan also articulate the value of utang na loob (debt of gratitude), which Pe-Pua and Protacio-Marcelino (2000) describe as an endearing dimension of Filipino identity and relations that anchors Filipino diasporics back to their native Philippines:

In fact, this is expressed in a popular Filipino saying, “Ang hindi lumingon sa pinanggalingan ay hindi makakarating sa paroroonan. (Those who do not look back to where they came from will not reach their destination)”. Utang na loob is a calling heard by many Filipinos who go to other lands but who still retain strong ties with their homeland (p. 56; emphasis mine).

5.4 Pagmamalasakit: upholding caring co-ethnic relations in Facebook

In the fourth topic category, many keywords point to the Facebook group's entities (i.e., admin, member), activities (i.e., post, add, comment, message) and purpose (i.e., help). A thorough reading of relevant posts revealed interactions between the administrators and members when it comes to what the admins had intended the group for (i.e., rules and goals of the Facebook group) and how they expect the members to treat each other (i.e., social courtesies and expectations).

The admins would remind the members that they should be welcoming and respectful to each other, especially to new migrant-members who might repeat inquiries already asked before. The admins would emphasize that the online group was created to assist their kababayan (fellowmen) and that the group continues to thrive because of the pagmamalasakit (concern) and willingness of members to answer questions and share experiences, knowledge, or advice regarding legal matters and everyday life in Germany. One of the admins, Alex, went so far as to acknowledge members' helping behavior as kabayanihan (heroism) and as something vital to the group, as seen in this excerpt:

This group has become successful not because of us admins but because of all of us that show concern (nagmamalasakit) to our fellowmen who need help. Because of members that give time to comment and assist our brothers/sisters who do not know what to do. It is everyone's heroism (kabayanihan) that's keeping this group alive.

Some members also expressed agreement and appreciation toward the efforts of the admins and fellow members in upholding the aims of the group, as exhibited in this post:

Ever since I was added to this group, I never posted or asked anything even though I had many questions. But because I was really confused at times [on what to do], I met some [members] and added them as friends and would just message privately to ask questions. And in other way. I learn a lot from reading the posted questions and information here and also for reading the comments. [S]o I thank this group for the steps that were taken[,] Admin…

Additionally, some discussions involved the migrants' experiences on the attitude of kapwa (fellow) Filipinos. Some expressed disappointments for having encountered unpleasant attitudes from female Philippine migrants or Filipinas. For instance, some Filipinas would intentionally avoid interacting with co-ethnics, or would display a certain sense of superiority. Such experiences are nevertheless incomparable to the online community members' generally pleasant interactions with each other.

The last topic within this category contained only two words, “God” and “Bless” and the key phrase “God Bless”. If based on the statistics alone, this topic should be removed as the co-occurrence of just these two words does not qualify it as a “theme”. However, this key phrase reflects the religiosity of Filipinos, many of whom are Roman Catholic and Christians. In Filipino Psychology (Sikolohiyang Pilipino), wishing someone well or giving them your blessings by saying “God Bless” can also be interpreted as a way of pagmamalasakit (concern) or a practice of kagandahang-loob (shared humanity) to express the value of pagkamakatao (valuing people).

Overall, this fourth topic cluster highlights a collaborative idea that migrating in(to) Germany is about continuing the practice of certain Filipino values and practices. Filipino migrants expect their fellowmen to espouse the meaning and spirit of kapwa (shared identity) and the practice and commitment of it, which is pakikipagkapwa (respecting the other person as a human being) (see also Umel, 2022). Such expectations persist despite living abroad, being situated in a different socio-cultural context, or interacting in online and offline realms.

5.5 The everyday mundane

The fifth and last category encompasses the Filipino migrants' mundane yet relatively unique logistical and administrative concerns in everyday German life. For instance, Filipino migrants shared their candid commentaries about Germany's tap water, which is safe to drink and even delicious (sarap) as compared to the non-potable tap water in the Philippines. Community members also exchanged thoughts and information about eligibility and steps to claim parental allowance (Elterngeld), child benefits (Kindergeld), and pension (Rente). Based on the representative posts, these social benefits go together as they are dependent on whether the parents have been employed (i.e., work) and on the parents' income. Other discussions are about housing and rental issues. Questions include: what conditions to consider when buying a house or renting an apartment (e.g., number of rooms, how big or small the migrant needs or wants it to be), or in which areas are housing and rental prices affordable (mura) or expensive. Exchanges also featured the Filipinos' queries about mandatory health insurance in Germany; some members' experiences with private health insurance; and comments regarding the need to avail health insurance, in general.

Certain key terms in this topic cluster further reflect Filipinos' high affinity for digital, social engagement (Kemp, 2021). For instance, the partner community members exchanged various random online recommendations, such as which Facebook page they can visit to watch the live streaming of the Miss Universe Beauty Pageant. Another example would be suggestions of apps to download or use to better learn the German language.

Overall, this last topic cluster reflected a shared understanding of life in Germany characterized by mundane everyday matters (e.g., housing issues), uniquely developed-country comforts and (social security) services, and the embeddedness of digital activities in Filipino diasporic life.

6 Concluding remarks

For a field that deals with minorities and vulnerable groups, it becomes imperative for migration and mobility scholars to underscore and endeavor an ethics-of-care approach (Leurs, 2017; Leurs and Prabhakar, 2018) while keeping up with innovative digital methods for data analytics. Currently. combinations of computational and qualitative techniques are applied to counter tendencies of decontextualized data and detached research, as is sometimes the case in the use of big data and computational methods (Fuchs, 2017; Leurs and Shepherd, 2017). However, such mixed methodologies can be bolstered by grounding them on critical, social, or practice-oriented theories. Such frameworks not only provide conceptual basis for substantiating machine-detected linguistic patterns and usage, e.g., topic clusters as interpretative frames (DiMaggio et al., 2013; van der Meer, 2016). More importantly, such theories underscore collective performativity (Pentzold, 2020) and mediated knowledge co-creation (Umel, 2022), as these processes play out in digital interactions. Echoing the wisdom in this article's introductory epigraph, such theories can thus help tease out the kind of meaning-making migrants “master” consciously or implicitly in their everyday online interactions.

In this study, the theoretical lens of social representations (SR) anchors the computational operationalization and corresponding analysis of Filipino migrants' shared understandings of migration (in)to Germany. Specifically, topic modeling enables recognition of migrants' Facebook discourses as legitimate sources of relevant “stuff of social talk” and as influencing the “priming and formation of mental models,” (DiMaggio et al., 2013, p. 574) such as specific SR. When something is discussed fervently, it not only captures the attention and interest of members, but also influences what can be considered ‘common sense' knowledge in the community. Whether members directly engage in the topic or not, members become exposed to how their community understands and relates to the topic. So even if a dominant topic may not be personally meaningful to certain individuals (e.g., instrumental topic of marriage registry), the issue can be socially meaningful for the community (i.e., evoke feelings and practices of solidarity).

In these ways, topic modeling assists in revealing certain shared ideas about migration that become accessible and “psychologically active” (Duveen and Lloyd, 2010, p. 6) for a specific migrant community. Qualitative analysis then enables deeper examination of such processes, e.g., how topics of residency and citizenship could further lead to the migrants' embracing or resistance of identities and practices (e.g., as loyal Filipino passport-holders but also dutiful German long-term residents). Similarly, wider discourses about migration in the German society (societal level) easily find their way into exchanges (interpersonal level) and eventually individual psyches, as members share what they read and hear from other media sources or social groups.

As a critical and practice-oriented theory of society and knowledge construction, SR theory also enables a reflexive attention to taken-for-granted aspects of phenomena and meaning-making. For instance, the topic of visa application may be insignificant, especially for citizens of developed countries. Yet as the empirical findings exhibit, such topics relate closely not only to stressful and emotional experiences for Filipino migrants, but also to the active engagement and support by online community members. Clean tap water and visa-free travel can be taken for granted by some, yet these are everyday comforts and privileges that evoke gratitude and relief for Filipino migrants.

A limitation for the present research is the existence of different languages used by the members of the partner Filipino migrant community in Facebook. The presence of multiple languages in the data lowers homogeneity, which is important to reduce noise in text mining calculations (Chartier and Meunier, 2011). This data characteristic could thus be the main reason that WordStat could only confidently categorize one-third of the data corpus into 25 topics.

Translation of multilingual data into English is a possible alternative considered for the present study. Yet identifying and translating massive amounts of text from various languages creates monumental difficulty for any researcher, even with the use of an automatic translating engine like Google Translate. Nuances of meaning are also lost in translation. As such, the present study's data have not been translated. Yet extensive, careful efforts have been applied to process the dataset while maintaining the integrity of the texts for the data modeling and analytical purposes of this research.

Additionally, automated techniques and programs accessible to social scientists are generally still incapable of dealing with texts written in various languages. Many social media data have not-so-ideal text characteristics such as the presence of misspellings, acronyms, and colloquial terms, apart from the mixed usage of different languages. While top key terms may be identified reliably despite spelling errors (Smith et al., 2014), more work is needed to establish a similar accuracy for determining and clustering keywords for multilingual data where spelling variation is higher.

Nevertheless, future studies will only benefit from computational methods as they continue to advance together with increasing digitalization and online social interactions. Echoing critical research traditions from SR, communication, and digital migration scholarship, the most important point is for studies to uphold critical awareness, situatedness, and reflexivity, especially in terms of the theoretical grounding of approaches, the affordances and limitations of the chosen software and methods, and the researcher's influence in the interpretation of findings.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. All names used in the article are pseudonyms to protect identities.

Author contributions

AU: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study in this article was supported by the Bremen International Graduate School of Social Sciences (BIGSSS), funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) -GSC263, 49619654.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a revised version of the first empirical chapter in my dissertation on social representations, social media, and Filipino migration in Germany. Major revisions were made in the introduction, methodology, findings, and conclusion sections. A few excerpts were added, while labeling and tabular presentation of results were also changed. My sincerest gratitude to my partner community and to the two reviewers whose comments and suggestions have been very helpful for finetuning this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Baumer, E. P. S., Mimno, D., Guha, S., Quan, E., and Gay, G. K. (2017). Comparing grounded theory and topic modeling: Extreme divergence or unlikely convergence? J. Assoc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 68, 1397–1410. doi: 10.1002/asi.23786

Caillaud, S., Kalampalikis, N., and Flick, U. (2012). The social representations of the Bali climate conference in the French and German media. J. Comm. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 22, 363–378. doi: 10.1002/casp.1117

Candidatu, L., Leurs, K., and Ponzanesi, S. (2019). “Digital diasporas: beyond the buzzword. Towards a relational understanding of mobility and connectivity,” in The Handbook of Diasporas, Media, and Culture, eds J. Retis and R. Tsagarousianou (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.), 31–47.

Chartier, J.-F., and Meunier, J.-G. (2011). Text mining methods for social representation analysis in large corpora. Papers Soc. Represent. 20, 37.1–37.47. Available online at: https://psr.iscte-iul.pt/index.php/PSR/article/view/452 (accessed November 13, 2023).

Dedecek Gertz, H. (2023). Collecting migrants' Facebook posts: Accounting for ethical measures in a text-as-data approach. Front. Sociol. 7, 932908. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2022.932908

DiMaggio, P., Nag, M., and Blei, D. (2013). Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture: application to newspaper coverage of U.S. government arts funding. Poetics 41, 570–606. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2013.08.004

Duveen, G., and Lloyd, B. (2010). “Introduction,” in Social Representations and the Development of Knowledge, eds G. Duveen and B. Lloyd (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1–10.

Flick, U., Foster, J., and Caillaud, S. (2015). “Researching social representations,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Social Representations, eds G. Sammut, E. Andreouli, G. Gaskell, et al. (London: Cambridge University Press), 64–80.

Fuchs, C. (2017). From digital positivism and administrative big data analytics towards critical digital and social media research! Eur. J. Commun. 32, 37–49. doi: 10.1177/0267323116682804

Hase, V. (2023). “Automated content analysis,” in Standardisierte Inhaltsanalyse in Der Kommunikationswissenschaft – Standardized Content Analysis in Communication Research (Berlin: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 23–36.

Hirsbrunner, S. D. (2021). Negotiating the data deluge on Youtube: Practices of knowledge appropriation and articulated ambiguity around visual scenarios of sea-level rise futures. Front. Commun. 6, 613167. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.613167

Hirsbrunner, S. D., Tebbe, M., and Müller-Birn, C. (2022). From critical technical practice to reflexive data science. Convergence. 1–15. [Epub ahead of print].

Hoewe, J., and Bowe, B. J. (2021). Magic words or talking point? The framing of 'radical Islam' in news coverage and its effects. Journalism 22, 1012–1030. doi: 10.1177/1464884918805577

Howarth, C. (2006). A social representation is not a quiet thing: exploring the critical potential of social representations theory. Br. J. Social Psychol. 45, 65–86. doi: 10.1348/014466605X43777

Howarth, C. (2011). “Representations, identity and resistance in communication,” in The Social Psychology of Communication, eds D. Hook, B. Franks, and M. W. Bauer (Palgrave Macmillan), 153–168.

Jenik, C. (2021). A Minute on the Internet in 2021. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/chart/25443/estimated (accessed August 26, 2023).

Kalampalikis, N., and Moscovici, S. (2005). “Une approche pragmatique de l'analyse Alceste [A pragmatic approach to Alceste analysis],” in Les cahiers Internationaux de Psychologie Sociale, 15–24. Available online at: https://www.cairn.info/revue-les-cahiers-internationaux-de-psychologie-sociale-2005-2-page-15.htm

Kaut, C. R. (1961). Utang-na-loob: a system of contractual obligation. Southwestern J. Anthropol. 17, 256–272. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3629045 (accessed December 23, 2023).

Kemp, S. (2021). “A decade in digital,” in Data Reportal. Available online at: https://datareportal.com/reports/a-decade-in-digital (accessed August 26, 2023).

Lahlou, S. (1996). A method to extract social representations from linguistic corpora. Jap. J. Exp. Social Psychol. 35, 278–291. doi: 10.2130/jjesp.35.278

Lahlou, S. (2012). Text mining methods: an answer to chartier and meunier. Papers Soc. Represent. 20, 38.1–38.7 Available online at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/46728/ (accessed November 13, 2023).

Leurs, K. (2017). Feminist data studies: using digital methods for ethical, reflexive and situated socio-cultural research. Feminist Rev. 115, 130–154. doi: 10.1057/s41305-017-0043-1

Leurs, K. (2022). “On data and care in migration contexts,” in Research Methodologies and Ethical Challenges in Digital Migration Studies: Caring for (Big) Data?, eds M. Sandberg, L. Rossi, V. Galis, and M. Bak Jørgensen (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 221–234. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-81226-3_9

Leurs, K., and Ponzanesi, S. (2018). Connected migrants: encapsulation and cosmopolitanization. Popular Commun. 16, 4–20. doi: 10.1080/15405702.2017.1418359

Leurs, K., and Prabhakar, M. (2018). “Doing digital migration studies: Methodological considerations for an emerging research focus,” in Qualitative Research in European Migration Studies, eds R. Zapata-Barrero and E. Yalaz (Cham: Springer), 247–266.

Leurs, K., and Shepherd, T. (2017). “Datafication and discrimination,” in The Datafied Society: Studying Culture through Data, eds M. T. Schäfer and K. van Es (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press), 211–231.

Marková, I. (2008). The epistemological significance of the theory of social representations. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 38, 461–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5914.2008.00382.x

Medina, B. T. G. (2001). The Filipino family (2nd ed.). Philippines: The University of the Philippines Press.

Moscovici, S. (1981). “On social representations,” in Social Cognition: Perspectives on Everyday Understanding, ed J. P. Forgas (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 181–209.

Moscovici, S. (1994). Social representations and pragmatic communication. Soc. Sci. Informat. 33, 163–177. doi: 10.1177/053901894033002002

Moscovici, S. (2001). “The phenomenon of social representations,” in Social Representations: Explorations in Social Psychology, ed G. Duveen (New York, NY: New York University Press), 18–77. First published in 1984 by Cambridge University Press.

Moscovici, S. (2008). Psychoanalysis: Its Image and Its Public (tran. D Macey). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. First published 1961 in French as La psychanalyse, son image et son public by Presses Universitaires de France.

Ocampo, A. (2019, May 1). ‘Oh my gulay!'. The Philippine Inquirer. Available online at: https://opinion.inquirer.net/121063/oh-my-gulay (accessed 31 July, 2023).

Peladeau, N., and Davoodi, E. (2018). “Comparison of latent dirichlet modeling and factor analysis for topic extraction: A lesson of history,” in Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 615–623. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/49965 (accessed August 20, 2023).

Pentzold, C. (2020). Jumping on the practice bandwagon: Perspectives for a practice-oriented study of communication and media. Int. J. Commun. 14, 2964–2984. Available online at: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/11217/3105 (accessed November 13, 2023).

Pentzold, C., and Menke, M. (2020). Conceptualizing the doings and sayings of media practices: Expressive performance, communicative understanding, and epistemic discourse. Int. J. Commun. 14, 2789–2809. Available online at: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/11210/3096 (accessed November 13, 2023).

Pe-Pua, R., and Protacio-Marcelino, E. (2000). Sikolohiyang Pilipino (Filipino psychology): a legacy of Virgilio G. Enriquez. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 3, 49–71. doi: 10.1111/1467-839X.00054

Pink, S., Horst, H., Postill, J., Hijorth, L., Lewis, T., and Tacchi, I. (2016). Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Provalis Research (2015). WordStat 7: User's Guide. Available online at: https://provalisresearch.com/Documents/WordStat7.pdf (accessed August 20, 2023).

Reinert, M. (2003). Le rôle de la répétition dans la représentation du sens et son approche statistique par la méthode ‘ALCESTE' [The role of repetition in the representation of meaning and its statistical approach using the ‘ALCESTE' method]. Semiotica 147, 389–420. doi: 10.1515/semi.2003.100

Sandberg, M., Rossi, L., Galis, V., and Jørgensen, M. (2022). Research Methodologies and Ethical Challenges in Digital Migration Studies: Caring for (Big) Data? Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Slocum-Bradley, N. (2010). The positioning diamond: a trans-disciplinary framework for discourse analysis. J. Theo. Soc.l Behav. 40, 79–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5914.2009.00418.x

Smets, K., Leurs, K., Georgiou, M., Witteborn, S., and Gajjala, R. (2020). The Sage Handbook of Media and Migration. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Smith, C., Adolphs, S., Harvey, K., et al. (2014). Spelling errors and keywords in born-digital data: A case study using the Teenage Health Freak Corpus. Corpora 9:137–154. doi: 10.3366/cor.2014.0055

Umel, A. (2022). Social Representations and Social Media: Exploring Facebook and Shared Meanings of Migration Among Filipino Migrants in Germany (PhD Thesis). Bremen: Universität Bremen and Constructor University Bremen. doi: 10.26092/elib/2027

Umel, A. (2023). Filipino migrants in Germany and their diasporic (irony) chronotopes in Facebook. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 26, 768–784. doi: 10.1177/13678779221126538

van der Meer, T. G. L. A. (2016). Automated content analysis and crisis communication research. Public Relat. Rev. 42, 952–961. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.09.001

Keywords: discourse, Facebook, Filipino, migration, pragmatics, representations, social media, text mining

Citation: Umel A (2024) Facebook and social representations of Filipino migrant life in Germany: a reflexive computational approach. Front. Hum. Dyn. 5:1284711. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2023.1284711

Received: 29 August 2023; Accepted: 12 December 2023;

Published: 10 January 2024.

Edited by:

Haodong Qi, Malmö University, SwedenReviewed by:

Simon David Hirsbrunner, University of Tübingen, GermanyAndrew Sewell, Lingnan University, Hong Kong SAR, China

Copyright © 2024 Umel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Audris Umel, YXVtZWxAY29uc3RydWN0b3IudW5pdmVyc2l0eQ==

Audris Umel

Audris Umel