- 1Somali Institute for Development Research and Analysis (SIDRA) Institute, Garoowe, Somalia

- 2Social Anthropology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 3Save the Children International, Mogadishu, Somalia

- 4International Maternal and Reproductive Health and Migration, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Amidst the ever-expanding debates in various academic and policy fields around migrant and refugee integration and local integration, we bring these two concepts in conversation with one another. Until very recently, theories of integration have had a state-centric focus in the Global North. This article expands and complicates this literature to focus on displaced Somalis within Somalia and its borderlands living in the cities of Kismayo and Garowe using mixed qualitative and quantitative methods in five displacement settlements. Toward this end, we use the often- engaged term “domains of integration” to frame integration. In our conceptualization, however, we incorporate the concept of “local integration” as a durable solution. In brief, we see the domains of integration as a productive concept in the Somali context. However, in Somalia, where clans are interwoven into the state, which lacks resources and power, clan affiliation represents social connections domains, yet also influences the state's role in the foundational domain of rights and citizenship and makers and means (employment, housing, education, health). International donors and NGOs, as well as international capitalist urban expansion also have a large role in these processes. As such, we argue that the ten domains of integration (discussed in detail below) intersect and blur to an even greater extent than in European and North American contexts, particularly around crucial issues such as housing, land, and property; a key factor in people's decisions to remain or leave.

Introduction

The trope of “transnational nomads” is often used to describe the Somali diaspora, dispersed across the world through displacement, resettlement, and other migrations. In exile or transit, Somalis often maintain transnational networks of social and economic support through familial and clan structures, which enables them to integrate (Horst, 2006). This study, however, examines the conditions and processes of durable integration for Somalis displaced within Somalia and its borderlands, including those returning as refugees from Kenya in five settlements in Kismayo and Garowe. The highly contested idea of integration requires additional unpacking to fit the Somali context, which has been shaped by conflict, natural disasters, and the resultant migrations, urbanization, and transformations of the state over the last three decades. To contribute to the integration debates, we recognize that the Global South cannot be approached with the state-centric focus we encounter in North America and Europe (Landau and Bakewell, 2018; Abdelhady and Norocel, 2023). At the same time, we caution against lurching in the other direction, portraying African states generally, and the Somali state specifically, as mere exceptions, oddities, or failures that cannot reflect on processes of integration in the Global North and beyond (Vigneswaran and Quirk, 2015; Boeyink and Turner, 2023). Toward this end, we use Ager and Strang's (2008) oft-engaged work on the interlocking “domains of integration” to frame integration. In our conceptualization, however, we incorporate the concept of “local integration” as a durable solution, which is a scholarly and policy discussion that often happens in parallel or in isolation for protracted displacement contexts in the Global South. In brief, we see the domains of integration as a productive concept in the Somali context. However, in Somalia, where clans are interwoven into the state, which lacks resources and power, clan affiliation represents social connections domains, yet also influences the state's role in the foundational domain of rights and citizenship and makers and means (employment, housing, education, health). International donors and NGOs, as well as international capitalist urban expansion also have a large role in these processes. As such, we argue that the ten domains of integration (discussed in detail below) intersect and blur to an even greater extent than in European and North American contexts, particularly around crucial issues such as housing, land, and property; a key factor in people's decisions to remain or leave.

The article is divided into five parts. First, we provide background of the displacement context, giving brief characteristics of the five field sites in Kismayo and Garowe. This is followed by situating our study in the debates around processes of integration and local integration. The third section outlines our mixed quantitative and qualitative methods and analysis. The fourth, and main results section, is organized around the four domains of integration (foundation, facilitators, social connection, and markers and means) and their sub-domains. Within each domain we use our data to present the significance and importance and how it relates to displaced people's decision to stay or go. Finally, we return to (local) integration theory and the policy implications for displaced populations in Somalia.

Background

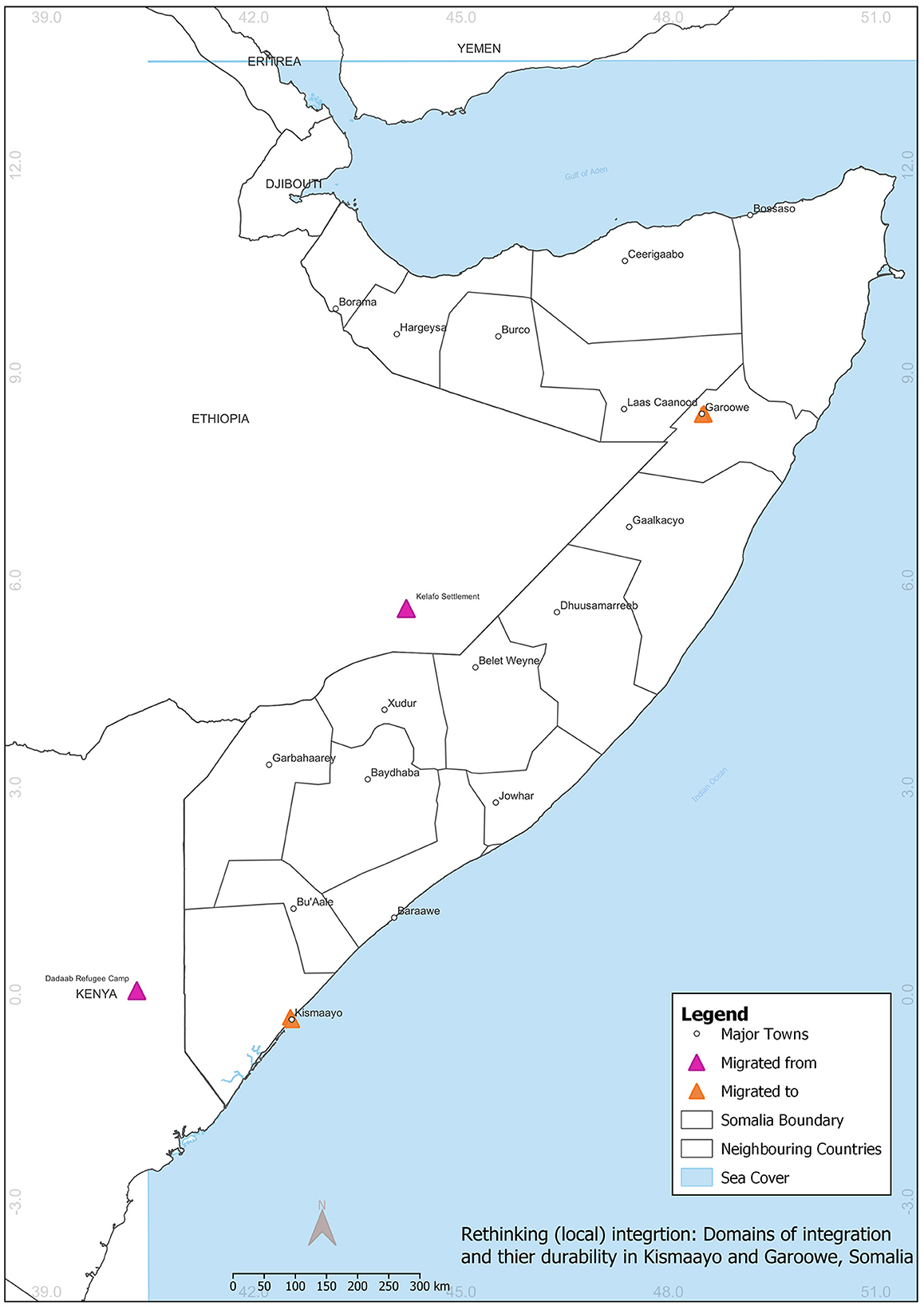

Somalia has experienced over 40 years of conflict and state erosion dating back to 1977/78 Ethio-Somali war (Bradbury, 1994; Elmi and Barise, 2006). The military regime of General Mohamed Siad Barre, which ruled the country since 1969, was ousted in 1991 leading to the subsequent collapse of the state and protracted humanitarian crises (Bradbury, 1994). After the civil war, power was divided and contested between the Transitional Federal Government and the Islamic Court Union (ICU), which was eventually toppled through involvement of Ethiopian forces from 2006 to 2008. The more radical Al-Shabaab militant group emerged. Today, Al-Shabaab is predominant in rural areas in southern and central Somalia and is a major driver of forced migrations, particularly through its at times excessive taxation of local populations (Mubarak and Jackson, 2023).1 The compounding effects of conflict, the prolonged absence of a functioning state, and environmental disasters, particularly droughts, have resulted in multiple phases of widespread displacement. See Figure 1 for locations of fieldsites and areas they moved from.

Protracted displacement and historical migration have resulted in a globally dispersed Somali diaspora. UNHCR currently estimates that there are more than 700,000 Somali refugees and asylum seekers, most living in neighboring Kenya and Ethiopia, and nearly 4 million people have been internally displaced (UNHCR, 2023). Moreover, at the end of 2022 there were an estimated 140,000 “returnees” or refugees repatriating from nearby countries. Most returned from Kenya and were resettled in Jubaland where Kismayo is located (UNHCR, 2022). We take caution with these figures, knowing displacement figures are difficult to accurately capture (Crisp, 2022). More importantly, however, we are tentative in labeling those on the move because displaced people elude simple categorizations (Zetter, 2007; Bakewell, 2008). We agree with researchers who problematize the IDP categorization in Somalia where wealthier or well-connected people displaced by drought settle in cities and never register as IDPs, blurring the distinction between IDPs and so-called “economic migrants” [Research and Evidence Facility (REF), 2018, p. 40]. An example of this comes from Garowe, where many members of Rahanweyn clan never register as IDPs. Through clan connections, they successfully establish small businesses, despite their clan not being prominent in Puntland.

Fundamental to understanding displacement in Somalia are the linguistic underpinnings, which help explain differentiated access to rights and privileges displaced Somalis experience, despite having Somali citizenship. Somali words “barakac” or “barakacayaal” characterize people who were forced to leave their place of origin and live in settlements recognized as IDP camps. Key to the definition is that people leave their “place of origin,” an area where they draw from support of their clan. Alternatively, “qaxooti” denotes refugees who cross borders. “Qax” means to flee a place because of war, insecurity, and fear of persecution. The word barakac means to leave place of residence due to war, insecurity, and natural disasters. Although the two words have similar meaning, a clear semantic distinction has developed in recent years. Furthermore, the use of the word barakacayaal for IDPs has gained traction because of its formal use by UN and international organizations providing assistance. The distinction between barakac and qaxooti becomes blurred when discussing citizenship and refugee status among ethnic Somalis displaced from other Somali inhabited borderlands such as Ethiopia into Somalia. These displaced people consider themselves and are treated as IDPs rather than refugees. Indeed, due to their ethnicity as per 1962 Somali Citizenship law, they are legally and in practice considered Somalis and treated locally as IDPs. Similarly, many returnees from Kenya or Yemen are resettled in the camps and settlements as IDPs.

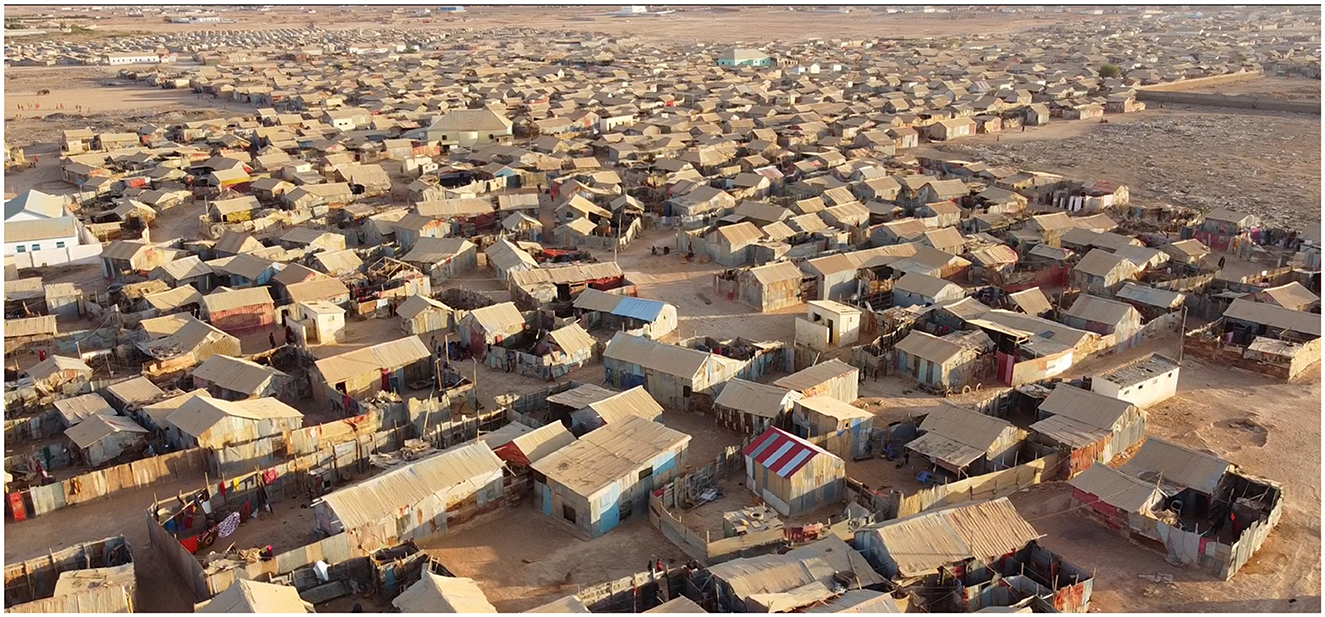

While comparing across sites in Kismayo and Garowe, the massive scale of displacement makes it impossible to generalize for all camps as there are reportedly more than 2,700 IDP sites across every state in Somalia/Somaliland (CCCM Cluster Somalia, 2023a). One generalizable aspect is the urbanization of most displacement locations. War and drought, which devastate agricultural and livestock assets, are clear displacement factors leading rural-urban migrations. People are drawn to cities by the prospects of safety from war, availability of jobs, and access to educational and healthcare services. However, as we discuss, urbanization and rising land prices leaves displacement sites vulnerable to eviction, which explains the importance our participants place on housing, property, and land, which are key themes in important recent monograph, Precarious Urbanism by Bakonyi and Chonka (2023), who conduct similar research in Baidoa, Bosaso, Mogadishu, and Hargeisa. This precarity is most pronounced in Mogadishu where self-established camps are run by brokers or “gatekeepers” (HRW, 2013) who have a clientelist relationship with camp residents, allowing access to housing and connection to aid in exchange for up to 50% of aid IDPs receive (Bakonyi, 2021, p. 14). Alternatively, Kismayo and Garowe do not have camp brokers, but rather “camp leaders” of prominent camp residents are appointed by governmental authorities. The following subsections give further background to these regions, cities, and displacement sites.

Kismayo

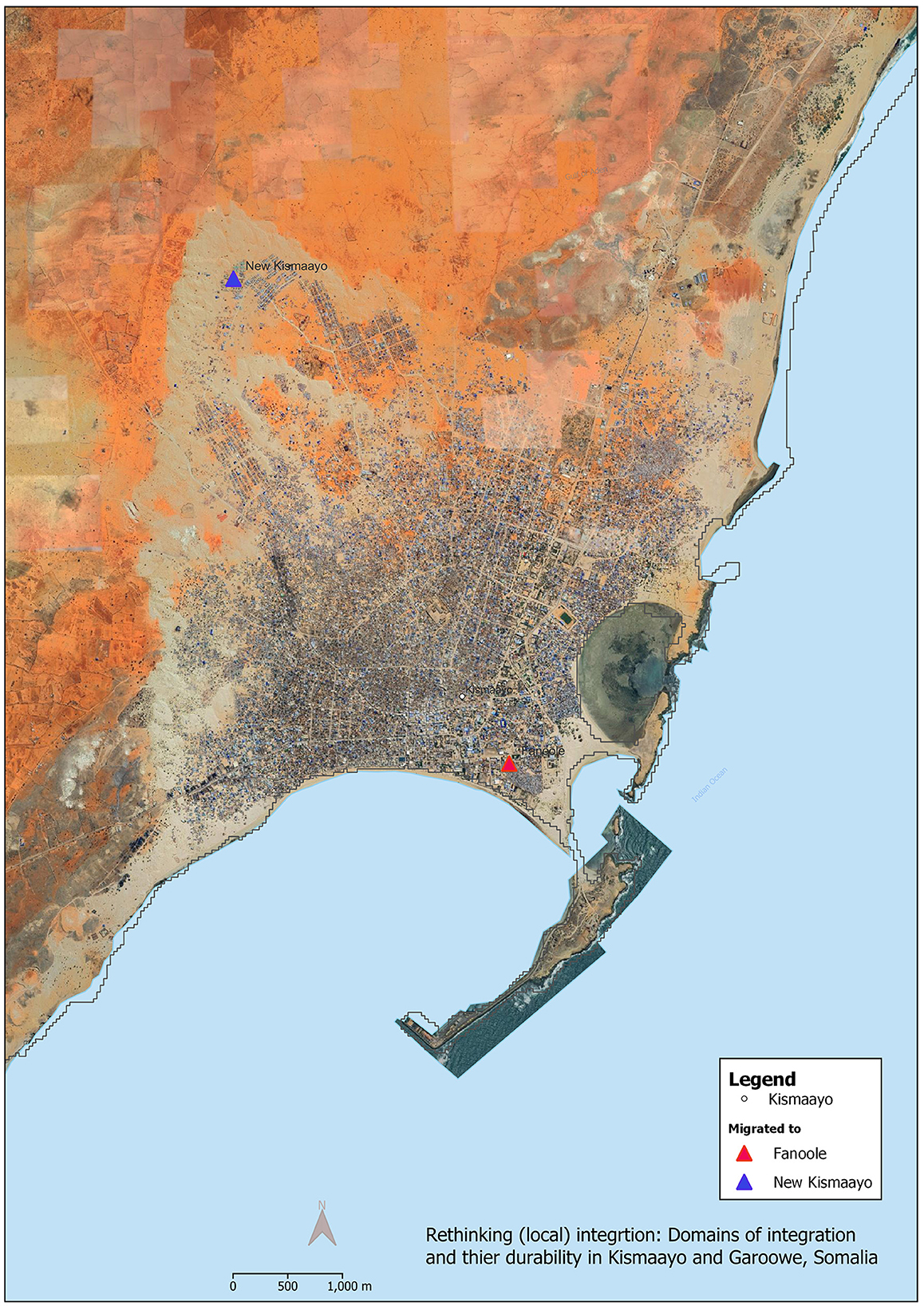

The port city of Kismayo is the largest city of the Federal Member State Jubaland, which gained federal recognition in 2013. The city hosts 170 verified IDP sites of 145,000 individuals (CCCM Cluster Somalia, 2023b) (see Figure 2). Severe drought and Al-Shabaab strongholds surrounding Kismayo are the primary displacement drivers [although Al-Shabaab strongholds in Lower and Middle Juba have also seen growth in population (Mubarak and Jackson, 2023)]. The city also accommodates Somali refugee returnees, mostly from Dadaab camps in Kenya. By 2023, following the repatriation program beginning in 2014, an estimated 55,000 returnees (including those assisted financially and logistically by UNHCR and unassisted or “spontaneous”) initially returned to Kismayo (UNHCR, 2022). Many felt pushed out by the Kenyan government's threats to forcibly close refugee camps and were drawn to the perceived improved security and job opportunities in the city (Ahmed et al., 2023). These migrations have profoundly affected the city as they have nearly doubled the estimated urban population since 2014 (JMOPW and UN-Habitat, 2020, p. 11). The Jubaland government, one of the most recent federal member states, has a centralized structure and established the Jubaland Commission for Refugees and IDPs (JUCRI) to oversee the settlement of displaced people. JUCRI appoints influential residents of displacement sites to be camp leaders or liaisons between government and humanitarian provisions. However, many of the services are funded or provided by international NGOs.

Displacement sites in Kismayo and Garowe can be divided into two typologies, “informal and formal,” based on home and land ownership and physical structures, though these categories blur over time as we demonstrate. The informal sites are built on public or private land and the houses are temporary shelters made of corrugated iron and plastic sheets. Informal settlements are at the highest risk of eviction due to their lack of legal protection. In contrast, the homes in the formal settlements are permanent structures made of bricks that were built for displaced people by international organizations on land that has been provided by the government. These formal settlements also include health and education facilities and other amenities (NRC, 2021, p. 21). Displacement sites differ in other ways such as location (inner city, outskirts), size, duration of existence, and composition of residents.

The field site, Fanole, consists of more than 20 unplanned displacement settlements south of the city (see Figure 3). It is occupied by people from surrounding areas around Kismayo. Private individuals from powerful clans took public spaces, through “land grabbing” during the civil war. These private individuals allowed IDPs to settle and build temporary shelters on the land to protect their ownership. Newly migrated settlers build their own shelter with plastic and iron sheets, with some materials donated by NGOs. These households are considered “occupiers” and while they do not pay rent, they are at high risk of eviction.

Midnimo (meaning unity in Somali, to denote the unification of refugees long displaced in Kenya), also known as New Kismayo, is a large, planned structure, which was negotiated between UN organizations and Jubaland government and local communities in 2017 to house displaced populations, returnees, and so-called “host community members” (see Figure 4). This resettlement scheme had detailed planning for spatial organization and social services, transport and commercial integrations into the wider city, making the area “some of the most attractive locations in the city” (Mohn et al., 2023, p. 12). There is a large, functional health center, primary school, community and women's center, and sports grounds. As such, Midnimo has been hailed as a success by researchers and international policymakers for its property rights protecting against eviction and integration to services and infrastructures as the sixth neighborhood of Kismayo (Ahmed et al., 2023, p. 27; Mohn et al., 2023, p. 13). However, IDPs in Midnimo and other areas complain of the inequality and preferential treatment of returnees from Kenya who receives greater and more consistent amounts of aid than others (Ahmed et al., 2023, p. 15). Though not a field site of this project, following the success of Midnimo, Luglow was constructed in a similar top-down fashion, though it was built 20 km outside the city. This distance has caused security concerns and made integration to services and employment difficult (Ahmed et al., 2023, p. 7; Mohn et al., 2023, p. 15). Bakonyi and Chonka (2023, p. 148–154) discuss similar dynamics in resettlement schemes in Bosaso and Hargeisa, which provided housing security but also isolates communities apart from jobs and services in the city, and further entrench the otherness of IDPs. This indicates the importance of spatial integration for displacement sites.

Garowe

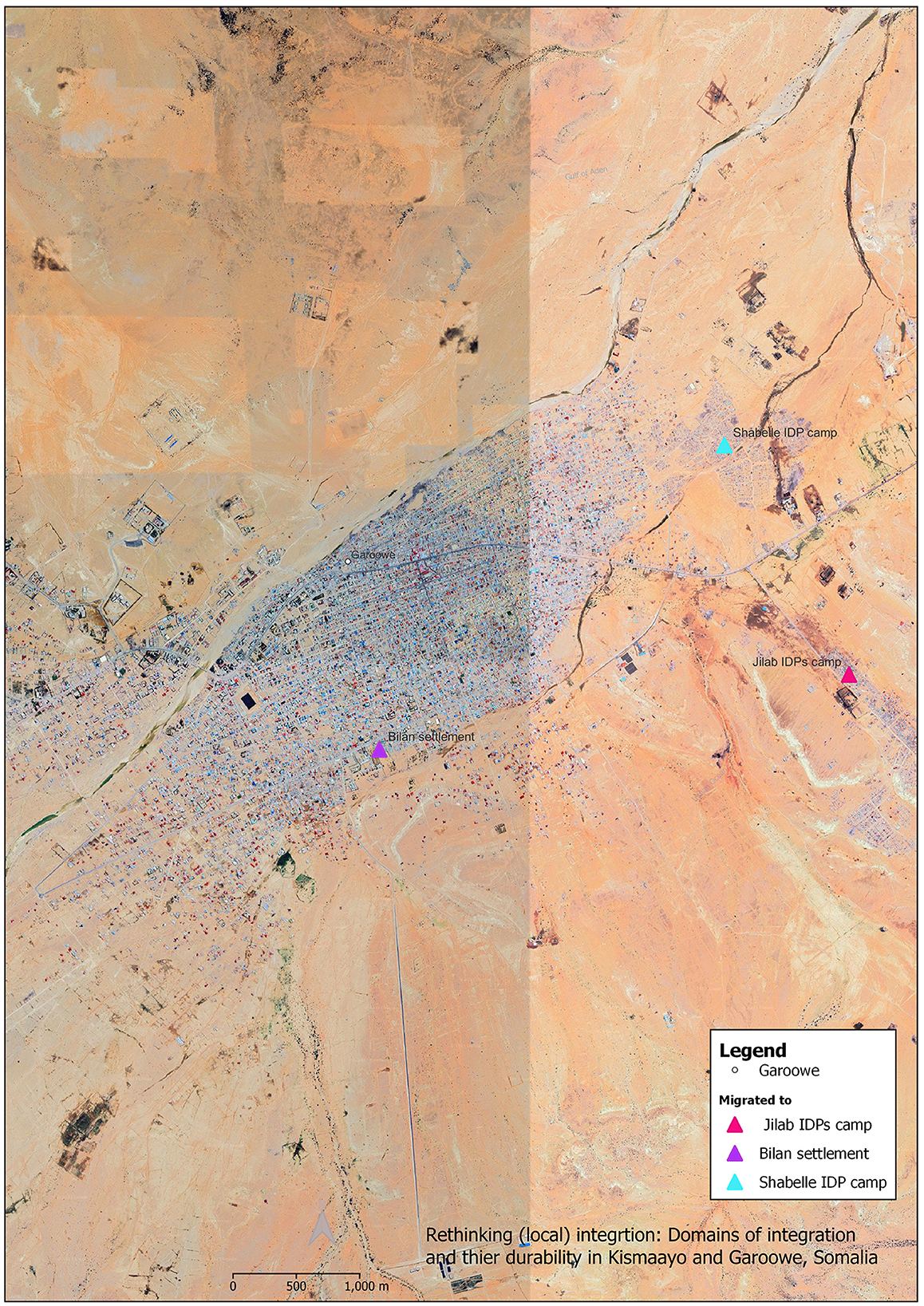

The first Federal Member State of Somalia, Puntland has benefited from being insulated from the worst effects of drought and war in comparison to central and southern Somalia (see Figure 5). This has been a primary pull for displaced people to travel large distances to reside in Garowe and the port city of Bosaso. This peace dividend has made a more vibrant economy and job availability in Garowe as compared with Kismayo. By 2023, around 55,000 individuals reside in 25 verified displacement settlements (CCCM Cluster Somalia, 2023b). The reasons for displacement are varied from violence and drought to tsunamis. Compared to Jubaland, the administration of displaced people is handled more at the municipal level, where camp leaders are appointed by the municipality. Unlike Jubaland, large-scale interventions such as Midnimo and Luglow have not been implemented in the city, leaving a more informal character similar to Fanole in Kismayo. Indeed, a reported 60% of displacement settlements are facing an extreme or high risk of eviction, which is largely due to the rental agreements in place at the camp level (CCCM Cluster Somalia, 2023b). However, there are contrasting sites such as Bilan, presented below, which demonstrate differing outcomes of durable solutions.

Established in 2009, Shabelle camp is one of the largest displacement settlements in the north of Garowe (see Figure 6). Most Shabelle residents are Bantu Somalis (known in Somali as Jareer, meaning “hard hair”) that lived along the Shabelle river in the Ethiopia-Somalia borderlands facing a series of displacements from the Ogaden War in the 1970s, spillover from the 1990s civil war, and localized violence in the Somali region of Ethiopia in the 2000s. Despite many coming from Ethiopia, they are considered barakac rather than qaxooti, or refugees. However, due to their Bantu ethnicity, Jareer have been historically racializd and marginalized in Somalia, though they still claim membership of clan lineages based on histories of slavery or clientelist protection (Besteman, 2016). Like Fanole, Shabelle consists of informal, self-built shelters. This arrangement of informal communal ownership was made as an agreement between the district authorities and the landlords to house IDPs for 10–20 years. However, with more than 10 years passing since this agreement, in conjunction with lucrative rise of land prices, the landowners are becoming impatient with this arrangement. This raises fears among Shabelle residents of imminent evictions. Local authorities are discussing relocating these and other informal sites outside of the city, although this risks disconnections to valuable services and livelihoods as in the Luglow settlement of Kismayo.

Jilab, established in 2010, is a cluster of settlements in the southern outskirts of Garowe. Long term residents of informal IDP camps and people displaced by droughts in Nugal region were offered permanent settlement in Jilab, resulting in a population of mixed clan lineages (see Figure 7). Earlier residents living in the initial Jilab camps were able to acquire land and own the houses they stay in. However, recent Jilab residents in the newer camps rely on rented houses and are classified as having high and extreme risks of eviction due to the inability to pay rent. In earlier established sites Jilab 1 and 2, there is a mixture of housing tenures. The original displaced people were given land and ownership as mentioned. However, many informants described camp leaders and authorities allocated housing to non-displaced Garowe residents. As such, both original displaced inhabitants and “hosts” from Garowe have rented their homes to more recently displaced families. This has resulted in a mixture of secure and highly precarious housing arrangements across Jilab.

Finally, Bilan offers a contrast to Shabelle and Jilab because it was established nearly 20 years ago after the 2005 tsunami displaced many people from the coast. Many initially lived with relatives until UN-HABITAT and the Puntland Ministry of Interior and Garowe municipality selected a proportion to have land and home ownership in Bilan. Eventually the settlement was integrated into the city (see Figure 8). Importantly, these displaced individuals come from the same dominant clan, Ciise Maxamuud sub-clan of Darood, which is prominent in Garowe. This group was able to leverage kinship ties into legal protection. Because of these clan affinities and longevity of residence, most living in this site do not consider themselves to be displaced. In fact, many even rent out their properties to newly displaced people and have gained the assets to move into Garowe city. We see similar displacement and connections to locally influential clans, offering greater resources, protections, and sense of belonging (Bakonyi and Chonka, 2023, p. 165).

Across the five sites there are relatively similar levels of access to services such as healthcare and education. Each location has health centers; however, locations such as Fanole and Bilan, which are located more centrally in Kismayo and Garowe cities respectively, have closer access to larger, more specialized hospitals. Similarly, each settlement has primary education, although Fanole's facilities are significantly lacking with only one classroom, compared to a more functional school in Midnimo. As mentioned, there are generally more jobs available in Garowe than Kismayo, though this is changing due to the arrival of foreign labor. As a response to recurring drought, various donors and NGOs distribute cash to households, which is a valuable resource to many, though many participants complained that this money does not last and not all people receive it.

Integration and/or local integration?

The boundaries of integration, as theory, practice, and discourse, have eluded consensus among academics and policymakers. Moreover, there are parallel, mostly siloed debates within forced migration studies and policy around “local integration” as a “durable solution” to protracted displacement. This section aims to unpack and reconcile these related, yet often separate discussions to understand plans for migration and integration of displaced Somalis in Kismayo and Garowe.

Integration

Integration in scholarship and policy is often assumed to be a process that betters the treatment and outcomes of migrants and refugees. One paradigmatic definition points to the aspirational nature of integration as:

The processes that increase the opportunities of immigrants and their descendants to obtain the valued “stuff” of a society, as well as social acceptance, through participation in major institutions such as the educational and political system and the labor and housing markets. Full integration implies parity of life chances with members of the native majority group and being recognized as a legitimate part of the national community (Alba and Foner, 2015, p. 5).

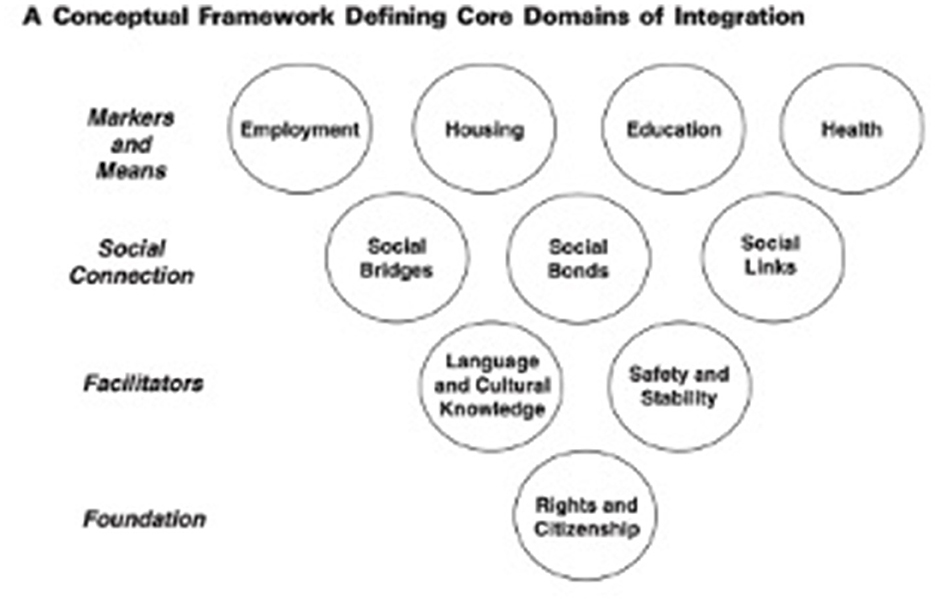

In line with this approach, the influential work of Ager and Strang (2008) formulates ten interlocking normative understandings of integration, which they call the “core domains of integration.” Shown in Figure 9, they created four categories: “foundation,” “facilitators,” “social connection,” and “markers and means.” Within these domains the valued “stuff” of society include employment; housing; education; health; social bridges, bonds, and links; language and cultural knowledge; safety and stability; and rights and citizenship. Phillimore and Goodson (2008, p. 322) critique this approach on operational grounds arguing the functional indicators (markers and means) lack sufficient data to capture the realities for displaced people and need supplemented with a qualitative element, “to better understand the interactions between indicators and to understand more about the experiential side of integration”. Moreover, Grzymala-Kazlowska and Phillimore's (2018) edited collection argue against the assumed homogeneity of “host communities” in integration research and policy, pointing to changing dynamics of “super-diversity” around the world and call for reciprocal understandings of the term.

Figure 9. Domains of integration (Ager and Strang, 2008, p. 170).

On the other hand, many scholars offer more wholesale critiques of integration, arguing the term is conceptually “fuzzy.” Many points out the normativity present in scholarship by Ager and Strang and others saying that, “the aim should be to study what is happening, the actual processes, not to prescribe or judge what ought to happen, the desired end goal” (Spencer and Charsley, 2021, p. 5). Some even call for an abandonment of the concept, saying discourses and policies of integration further entrench immigrant minorities as “others” (Rytter, 2019), and is otherwise an extension of neocolonial domination (Schinkel, 2018). In other post-conflict cases in Africa, such as Burundi and Rwanda where there was ethnic genocidal violence, integration is conceptualized in different ways without engaging in the same integration literature at all (Purdeková, 2017). Building on this critique, recent scholarship notes that these debates have mostly taken place in the Global North. Abdelhady and Norocel (2023, p. 123) contend that, “instead of the state-centered approach to integration that dominates analyses in the Global North, interrogating immigrant integration in the Global South decenters the state and underscores informal and local experiences of joining communities and forging attachments”. Landau and Bakewell (2018, p. 5) make similar points and add to the longstanding critique that integration “is infused with normative assumptions about the nature of host communities and their responsibilities to outsiders” and claim that “making sense of mobility's socio-political consequences in Africa means moving past discussions of the formal policy regimes that often frame Euro-American analyses. Beyond the general weakness of many African legal systems, few countries have overt integration policies and the term is rarely used”.

Local integration

We agree with many of the critiques above, especially the call to decenter the focus on the state and critically analyze the nature of citizenship. However, we disagree with the claim that “few countries have overt integration policies and the term is rarely used.” Many African states have negotiated and contested policies of local integration as a durable solution for displaced populations within and without their borders. Indeed, the Federal Government of Somalia has created the National Durable Solutions Strategy and is signatory to a wide range of legislature and international instruments relating to refugees and IDPs (Federal Government of Somali, 2020). Like integration, local integration needs to be unpacked because it has changed in meaning over time and lacks a shared understanding. Furthermore, local integration policies naturally apply differently between refugees and IDPs.

The 1951 Refugee Convention set out three durable solutions: voluntary repatriation, resettlement (to a third country) and local integration.2 Local integration in this original formulation explicitly meant naturalization or granting citizenship. However, because this option of citizenship has rarely been offered to refugees, it became known as the “forgotten” solution to displacement (Jacobsen, 2001). Hovil and Maple (2022) claim that it is the “evaded” solution because governments deliberately avoid naturalization. Instead as a substitute “de facto integration” through self-settlement of refugees from below and livelihood and “self-reliance” projects implemented from above has been the focus of governments, policymakers, and academics when discussing local integration. This allows Global North states to continue containing undesirable populations and funding the majority of protracted refugee situations in the Global South, without finding durable solutions. In turn Global South states avoid the domestically unpalatable political act of granting citizenship. Local integration's original intent as a solution to displacement through citizenship has been neutered. Without discrediting the things refugees do to integrate themselves into societies from below, with or without the consent of the host states, Hovil and Maple (2022, p. 264) call for a return to naturalization as a viable solution to refugeehood: “instability breeds instability: when national refugee policy is highly susceptible to change and shifts based on political pressures and forces, it does not matter how ‘de facto integrated' into the community a refugee is, their status remains vulnerable.” They emphasize “the urgent need for these self-driven approaches, which are often quite fragile, to be matched by formal, legal integration, in order to offer the solidity and stability that is otherwise lacking”. What does “local integration” means for internally displaced people, where citizenship seemingly is not a relevant factor?

Local integration and IDPs

Largescale IDP situations also use the language of durable solutions. The Framework on Durable Solutions for Internally Displaced Persons, established in 2009 by highest-level humanitarian coordination platform, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee, consider the three durable solutions as: “Sustainable reintegration at the place of origin (hereinafter referred to as “return”); Sustainable local integration in areas where internally displaced persons take refuge (local integration); Sustainable integration in another part of the country (settlement elsewhere in the country)” (The Brookings Institutions and University of Bern Project on Internal Displacement, 2010, p. 5). For IDPs, naturalization is a moot point because they already have citizenship. As such, local integration for IDPs takes a similar tone to discussions on integration, which is more about indicators of integration such as livelihoods and access to services such as education and healthcare, rather than a permanent solution to displacement—a crucially missing point according to Hovil and Maple (2022). This article asks the question, is there an anchoring component for IDPs and returnees to locally integrate in a way that naturalization fortifies local integration for refugees?

To answer this question, we use Ager and Strang's (2008) domains of integration framing in Kismayo and Garowe, which has been applied in other IDP contexts such as DRC and Ukraine (Chuiko and Fedorenko, 2021; Jacobs et al., 2021). Although Ager and Strang focus of refugee integration in the UK, they recognize adjustments are needed to suit contexts different from London and Glasgow:

This mechanism not only provides a basis for using the same framework in contexts with widely differing conceptions of citizenship, normative expectations of social integration within communities, educational attainment etc. […] Its wider utility and explanatory value now needs to be tested in diverse contexts to gauge whether the proposed structure captures key elements of stakeholder perceptions of what constitutes integration in an appropriately broad range of settings and timeframes (Ager and Strang, 2008, p. 185).

Although Ager and Strang's framework is self-described as presenting “normative understandings of integration”—a key source of critique by many scholars—we use this approach to present what displaced Somalis describe as barriers to integrating on their own terms. We make no prescriptions for what they should do or where they ought to migrate; we asked them through surveys and life history interviews about their life throughout displacement and if they plan to leave where they currently live, which we expand in the section below. We agree with Hovil and Maple's argument that without citizenship, “instability breeds instability.” However, based on our findings, we see the relationship between citizenship and state in Somalia complicated by area-based clan structures, whereby those displaced from outside locally dominant clans or sub-clans have differentiated access to rights and resources, particularly around land and property, which is a bedrock that other domains of integration must be built on.

Methodology

This study is a part of multi-sited, mixed methods research project exploring access to healthcare at the intersection of gender and protracted displacement amongst Somali and Congolese refugees and IDPs in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Somalia, Kenya and South Africa. The data collection was conducted in Garowe and Kismayo between 2020 and 2021. The study adapted the Social Connections Mapping Tool methodology to the displacement context Somalia (Strang and Quinn, 2021; Boeyink et al., 2022). The mapping tool combined participatory workshops (of 178 participants) which asked what people or institutions (social connections) people in their community turned to for health, mental health, and sexual and gender-based violence support. Their responses formed a list or social connections. This was followed by a quantitative survey of 800 IDPs and returnees asking inquiring about wealth, health status, and amount of contact and trust with the list of social connections. We also conducted 60 face-to-face semi-structured interviews with displaced people across the five sites. The survey documented the main demographic characteristics of the participants, reasons for displacement, social connections, employment, education, health, and other support resources as key elements for access to services. The semi-structured interviews were used to gain deeper understanding of the participant's displacement history and how factors such as gender, residency, livelihood, and socio-economic status affected their displacement and influenced their access to healthcare. Ethical approval was granted by the (University 1) and in-country by Somalia Federal Ministry of Health, and all participants provided written consent to participate. Further authorizations of access were received from the Ministry of Interior of Puntland State and Garowe District Local government for IDP camps in Garowe and Jubaland Commission for Refugees and IDPs (JUCRI) for IDP camps in Kismayo.

The positionality is important as the researchers collecting data were all further educated than most participants, many of whom were experiencing significant poverty. Moreover, in Garowe, all researchers were from Puntland unlike most of the participants so had different clan affiliations. In Kismayo, there was a mix of Puntland and Jubaland researchers, which had some clan connections with the participants, which aided in building trust. Despite the discrepancies in clan and class, the research team spent time building connections to “camp leaders” who acted as spokespersons for the settlements to the government and NGOs and who were trusted among the IDP camps. The camp leaders vouched for the researchers and encouraged participation, which helped build initial trust. Moreover, all interviewees had already participated in the survey and were familiar with the research project. All interviews and surveys took part in Af Maxaa Tiri Somali language (apart from two interviews conducted in Af Maay Somali language in Kismayo), which allowed researchers and participants to speak in their first languages. The interviews were transcribed and translated to English. Undoubtedly some nuances may have been lost in this process, particularly when people spoke in local idioms or proverbs that do not directly translate to English.

Analysis

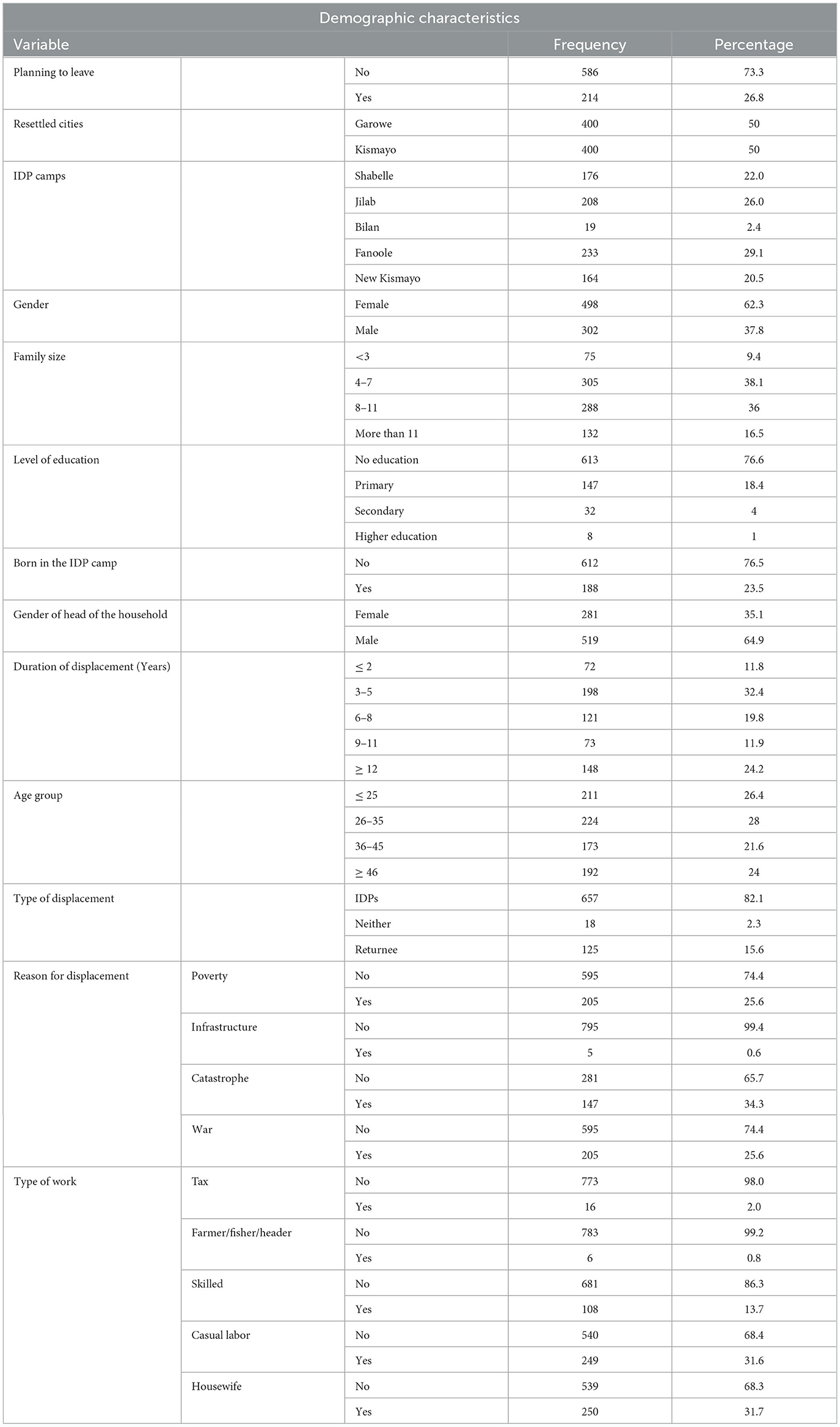

The quantitative survey data was collected in Kobo Toolbox and was analyzed in SPSS v24. The participants demographic data such as age, family size, and duration of displacement were transformed into categorical variables, by using median and interquartile range and were used to generate summary statistics to examine the distribution of the socio-demographic characteristics of the IDP population. See Table 1 for results. This was done to gain a better understanding of the sample and to identify any potential confounding variables that could impact the outcome variables.

The main focus of the study was to identify social connections and explore their relative importance to IDP access to health care services. However, it examined a number of elements within the domains of integration, including a question about intention to leave or stay as proxy variables for integration. The survey question was framed as follows:

Are you planning on leaving this place during the next year?

a. Yes, and I have already made arrangements

b. Yes, but I haven't made any concrete plans

c. Yes, but I don't have anywhere to go or a way to leave

d. No, but I think I will leave in a few years

e. No

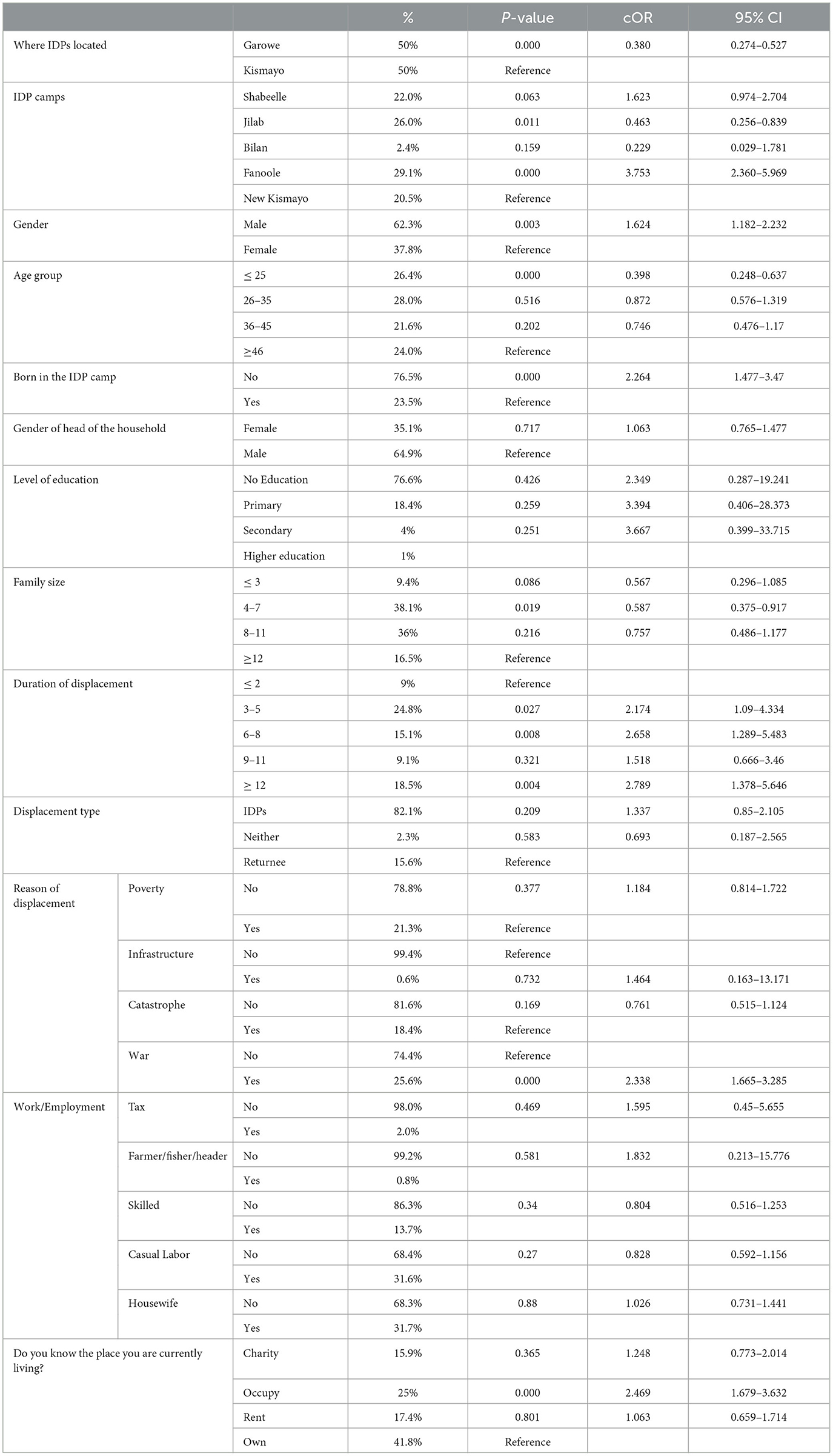

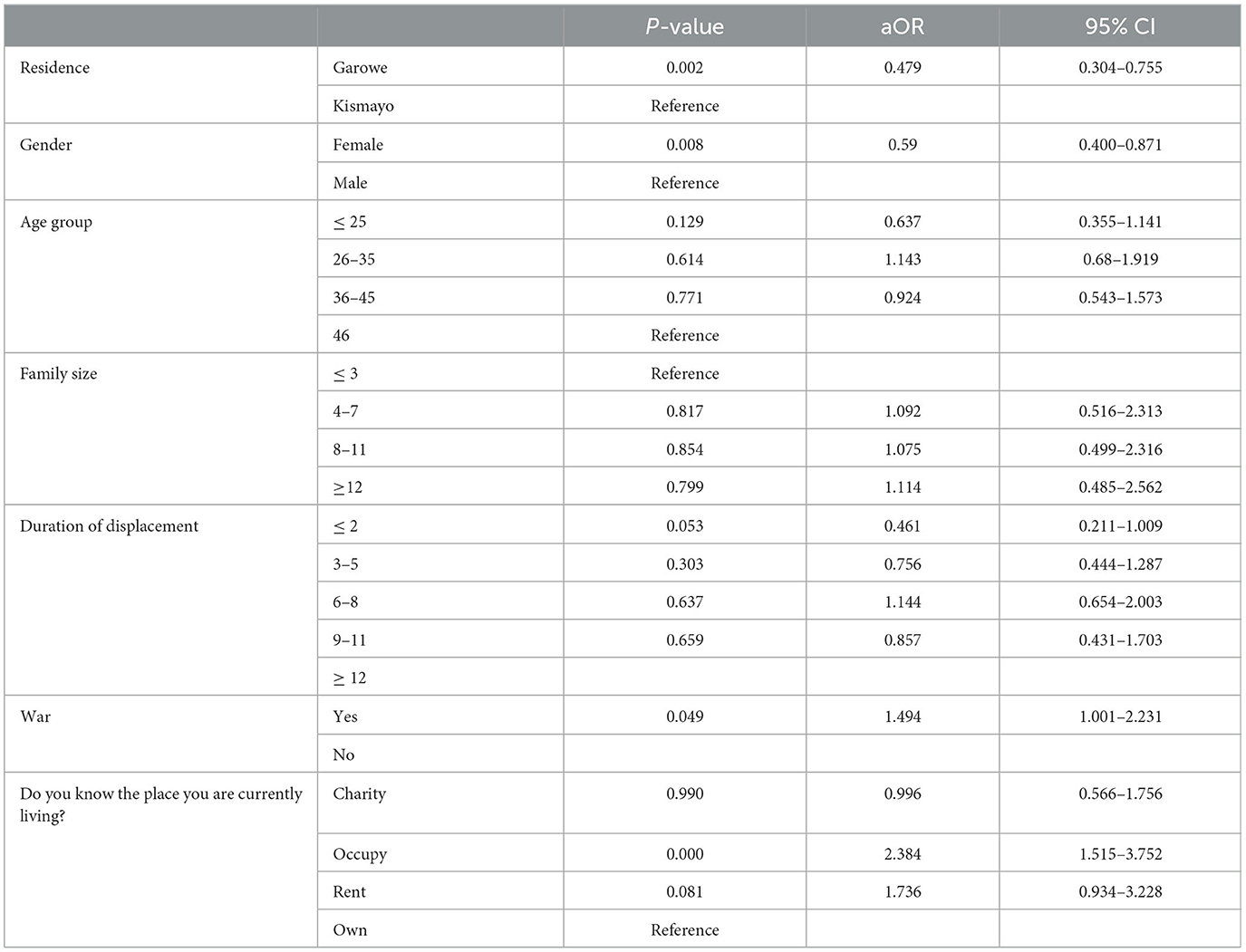

We recognize this singular question is inadequate to determine whether the displaced informants were integrated into society. However, we used this question as a starting point because inherently no person can integrate if they will imminently leave. This quantitative data was the bedrock of our analysis in that in pointed toward important factors for why people wanting to leave, such as the camp they live in or what type of housing they are living in (see Tables 2, 3). Our qualitative data was used to supplement this quantitative data to gain more insights into people's reasons for fleeing, plans for staying, and levels of integration within Ager and Strang's framework.

Univariate logistic regression analyses were used to determine whether each independent variable was associated with the participant's response of their plan to leave the IDP camp during the next year. Variables with a p-value of 0.1 or less were included in the final model of the multivariate logistic regression. Multicollinearity problem was detected in the final model, to overcome those challenges we ran the chi-square test to find the association between the independent variables, and later we eliminated IDP camps/independents variable which is associated with city (Garowe and Kismayo) where IDPs were living. A multivariate logistic regression was conducted to examine the impact of all significant independent variables on the outcome variables. This allowed for the identification of the independent variables that were the most strongly associated with the participant's response of their plan to leave the IDP camp while controlling for the effects of other variables in the model.

Four of the coauthors participated in the qualitative analysis using web-based collaborative qualitative analysis program, Taguette. The team agreed to code the interviews by some variations of Ager and Strang (2008) domains of integration and then the writing team discussed and analyzed the codes, agreeing which quotes to include in the article.

Results

Foundations

Ager and Strang (2008, p. 176–177) emphasize that indicators for “foundations” should draw attention to the ability of displaced people to access rights that provide “the basis for full and equal engagement within society”. Citizenship and rights are crucial to such engagement; however, they also note that, “there is probably no theme that creates more confusion and disagreement regarding understandings of integration than that of citizenship, and the rights and responsibilities associated with it. This partly reflects the widely different understandings of citizenship but, more fundamentally, of nationhood across societies” (Ager and Strang, 2008). This is particularly relevant in this research in Somalia, where the focus is on “internally,” rather than “externally” displaced populations, a country with a prolonged recent history without a central government, and even longer histories of contested and porous borders.

There was a widely shared understanding among participants that being “internally displaced” or barakac, was a matter of identifying as Somali, rather than being displaced from locations within the country's borders. One participant, originally from Kelafo, a predominantly Somali town located within Ethiopia, was asked if he considered himself to be foreign in Somalia. He replied, “No. I saw myself as Somali living at the border of Ethiopia and Somalia, and who then came to his country.” Like many others in similar circumstances, he considered himself internally displaced even though he had crossed an international border, and he was treated as such by receiving communities and governmental and non-governmental organizations. The significance of citizenship was clearly articulated by returnees who had resided in refugee camps in Kenya. As one returnee woman explained,

I am still in Somalia, not in a foreign country. Although I do not stay in my own home and I live in a displaced people camp, in my mind I feel that I am in Bu'ale (southern Somalia). Despite the difficult conditions in our lives, I consider myself as someone who is in his settlement... I am still in Somalia, I use Somali language and the officials in the government are all Somalis. The people around me are all Somalis. When I go to the town, no one asks me for a permit or status document. I don't face any discrimination. I was in Dadaab refugee camp sometime back. People could not even go outside of the camp or move freely. If some small incident took place, people were being detained. But now I am in my country with no problem at all.

However, there is a clear point of tension between ideas about national belonging, which are widely held by all participants, and notions of local belonging, which were more contentious and have significant ramifications for integration. Clan affiliation is the strongest thread that runs through notions of local citizenship, access to rights, and all the domains of integration. As one man in Garowe stated, “the host community does not consider me one of their own, although I have been here for a long time. So I assumed my natural role as an IDP.” When asked the reason for this, he replied “tribalism.” Similarly, a female IDP in one of the Garowe camps told us that she had not received any form of aid, “The aid recipients are registered on nepotism. When we asked him (the camp manager) why he didn't register us, he suggested that we were business people. When we confronted him about other people who have businesses whom he has registered for aid benefits, he did nothing. So we were overlooked that way.” Another woman in Garowe said, “The camp manager is a bad man he treats people unfairly and with discrimination. When there is assistance, he gives everything to his close relatives.”

In short, those displaced to areas where their clans were already present are more likely to find social and economic support, which facilitates integration. Those with few or weak clan affiliations are more likely to struggle. The relationship between clan and citizenship emerges in formal and informal ways. One woman in Garowe told us that as someone from a minority clan in the region, it was more difficult to seek justice and protection: “While we were in Mogadishu we were treated as equals, now we are treated as inferior. If you have an altercation with some girl, all the others from the area would gang up on you and say that you are not from here, so in that instance, Garowe is worse. So if we have problem with someone here, we just let it go, we can't go into conflict because people would gang up on us.” Even those in areas where their clan is present do not share uniform experiences. One participant shared the abuse and discrimination he and his children had experienced in their home village. The interviewer asked, “Didn't you have any family or relatives who could defend or help you? Are you not from this area?” The participant confirmed that he was from the area, but no one from his clan offered any assistance, and instead he was accused of being a terrorist and a member of Al Shabaab. Therefore, while recognizing the importance of clan affiliation, we urge caution in oversimplifying what are complex and intersectional relationships that interact with race, class, age, and other factors.

Race is also a salient marker of exclusion from full foundational rights in Somalia, particularly for Jareer or Bantu Somalis. While this group is not subject to the same degree of violence and outright hostility, they still face discrimination, and intermarriage is still extremely rare between Jareer and those within the Somali clan lineage structure. This racialization gets further entrenched through IDP labels and exclusions (Bakonyi and Chonka, 2023).

Facilitators

Ager and Strang identify “facilitators” as sites of intervention to facilitate or constrain integration. They establish language/cultural knowledge and safety/security as the two facilitators in their research. These facilitators are closely aligned with notions of rights and citizenship for internally displaced people. A woman in one of the Kismayo camps explained that familiarity with the land and culture, and the fact that she had relatives and friends living there, made it an attractive location. When we asked a male interviewee, originally from Kelafo, Ethiopia if he considers himself to be displaced, he told us, “At first, yes; now, no, because I'm in one of Somalia's regions. I am Somali. These people who reside here are Somalis. They don't speak a foreign language; we speak Somali. Today, I believe I am in Somalia and that I am a Somali boy. I came from my region and arrived in my other region.” As mentioned, in the methodology section, most of the interviews were spoken in Af Maxaa Tiri Somali rather than Af Maay Somali. While this language difference did not factor significantly in our study, Bakonyi and Chonka (2023, p. 154–156) found significant exclusion and discrimination in Mogadishu and Bosaso toward Maay Somali speakers.

Many interviewees in Garowe highlighted the relative peace and stability of the region as a key factor that attracted them. One man commented “we chose Garowe because it was very peaceful, also many government and international agencies are based here. We also chose it for education and health services. Also, we chose it because we can work and earn a living in peace. We got most of those things.” Security, safety, and peace were frequently referred to as an absence of conflict or crime, but also in reference to security of land or housing, as discussed in more detail below.

Social connections

In Somalia, the notion of a shared religion, language, and set of cultural values are often cited to illustrate relative homogeneity (Elmi and Barise, 2006), however, this perception risks overlooking the challenges faced by IDPs. Ager and Strang (2008, p. 177) describe social connections as the “connective tissue” that mediates between foundational principles and public outcomes such as health, employment, housing, etc. This biological metaphor is apt in this context, where the “connective tissue” was most frequently understood in relation to ideas of family, blood, and clans. Ager and Strang (2008) distinguish forms of social connections as relationships with (i) family and/or those with shared values, such as religious or ethnic groups (social bonds), (ii) “other communities” (social bridges), and (iii) structures of the state (social links). However, in this research we found that clan belonging, or “social bonds” was thread throughout all aspects of the conceptual framework.

As noted above, Somali ethnicity, citizenship, and clan belonging are tightly interwoven. This profoundly impacts how people access services, seek livelihoods, and understand themselves as integrated (or not). Many participants told us that they had received food, money for bus fares, or offers of free transport or temporary accommodation from strangers during displacement journeys. These acts of charity are commonly seen as a cultural and religious requirement among our participants, all of whom are Muslims. Close family or wider clan ties would enhance the expectation that people should provide support. As such, the notions of “social bonds” and “social bridges” are hard to disentangle, as the notions of “family” and those with shared values are expansive categories that blur into “other communities” in terms of religion and geographic location. Many interviewees expressed a reliance on family to pay for healthcare. One female participant told us that she and her husband are both physically disabled and live with and rely on their adult daughter for care and support, highlighting the role of such relationships in physical and emotional, as well as material support. Interviewees suffering from ongoing illness or injuries frequently mentioned the absence of kin or community who might provide or pay for care. In such cases they either expressed a lack of connections, or only had family facing similar levels of destitution. Ager and Strang's concepts therefore may not appear readily applicable in this context, however they illuminate the extent to which contextual notions of kinship and belonging are interwoven in diverse sets of relationships. Furthermore, they allow us to interrogate how gender, clan, and socioeconomic status can shape the extent to which bonds, bridges, and links bleed into one another.

Our interlocutors suggest that social bonds within a community are also shaped by gender; noting it was often women who organized financial collections for medical care, or that women more actively maintained social networks and communication. One female IDP in Garowe said, “Women are closely connected and have constant communication. You should have seen us yesterday, all of us have been in one house. People do talk to each other, they check on each other, they visit each other but they can't offer much help to each other, because they are in the same situation.”

Relationships with the state (social links) are similarly shaped by clan affiliation. The “4.5” power sharing of the Somali government (parliamentary and cabinet) means that the representation is distributed to the four large clans: Darood, Hawiye, Dir, and Rahanweyne, while 0.5 is assigned to the minority clans. In Puntland and Jubaland there is no such formula, however, political seats allocated for each sub-clan. Members of Parliament act as gatekeepers to opportunities such as employment. During social connections workshops, residents in Bilan expressed that they have local parliamentary representatives because they are from major clans in Puntland. Conversely, IDPs in Shabelle and Jilab are largely from southern Somalia and have not had political representatives in Puntland historically.

Levels of integration are not entirely determined by clan membership, however. For example, connections to the state for IDPs outside of the dominant local clan structures are evolving through democratization. IDPs were allowed to vote in Puntland's first “one-person, one-vote” local elections. This brought politicians to displacement settlements seeking votes and promising development projects and services and greater recognition for IDPs. The election even saw IDPs elected to Puntland's regional parliament (Mohamoud, 2023). The election means that the concerns of barakac from outside Puntland and non-members of powerful regional subclans have some degree of representation of their interests locally. While there were some controversies, fighting, and postponed votes at this election (Al, Al), this event demonstrates that social connections to the state (social links) may be possible for IDPs beyond traditional clan connections. Although it is too early in this process to see what tangible effects there are beyond electioneering promises made by politicians, the distinctions between social connections and foundational rights and citizenship may become more fluid over time. Displaced people outside of dominant clans may feel empowered to make stronger rights claims as voting citizens. Any social connections, whether bonds, bridges, or links, are crucial in acquiring the “stuff” of markers and means: employment, housing, education, and health.

Markers and means (employment, housing, education, health)

Employment

Access to livelihoods plays a crucial role in causes of displacement, motivations for relocation, and capacity to settle in new locations. As such, employment has been the most extensively researched domain in the field of integration (Castles, 2002). In essence, access to money can buy the other markers and means of housing, education, and health. Indeed, as other researchers, those in Somalia with the financial means and strong social connections never live in camps but rather integrate into cities and do not make it into a study such as ours [Research and Evidence Facility (REF), 2018, p. 40]. However, for most of our informants living in camps, lack of access to livelihoods was the principal cause of their displacement and daily struggle. Many participants commented on how drought and conflict had impacted their crops, livestock, and capacity to meet their basic needs. One man stated, “I was a pastoralist, I farmed and I herded livestock. I fled recurrent droughts, civil conflict and lack of basic social services.”

Many say that Garowe and Kismayo offer far more employment opportunities in comparison to their former rural villages and towns, which have been devastated by war and drought. However, many lament that recent years have seen struggling economies, particularly for those living in displacement settlements. Our study revealed that the majority of IDPs are engaged in casual and domestic labor, accounting for 31.6 and 31.7% respectively. In contrast, only 13.7% of IDPs are involved in “skilled” work (such as nurses, musicians, and artists), and only 0.08% are working in Somalia's production sector, which includes fishing, farming, and animal rearing. Our qualitative data shows that IDP communities lack qualifications and skills to enhance their employment.

Labor in the cities is highly gendered as well. In the Garowe and Kismayo, men largely found employment on construction sites while women were more likely to perform domestic labor, including laundry services, garbage collection and working as housemaids. In Kismayo, a small number of women also worked in construction. A female IDP elaborated on these gender differences: “Women mostly depend on their children who go to work in the cities, there are many girls who want to work but don't have places to go to work.”

The growing cities, which have been infused with global capital and labor, have made the work situation for men and women worse in recent years. The relative stability of Garowe has resulted in a growing construction industry, attracting companies and workers from abroad, resulting in far greater competition for employment, significantly reducing job opportunities for IDP men in particular. One male participant in Shabelle explained these challenges: “I was a young man and there were droughts (…) The people there were farmers, and there is drought, there is no work at the farms, and you become worried once you have no job and you leave.” He continued, “Normally you stay where you can get work and live it. I did not get that vibe in Beledweyne. Now that I am in Garowe, it is better in terms of my livelihood.” Despite these positive comments on the possibility of earning a living in Garowe, he later reflected: “Here in Garowe, I work as a mason in construction, and it is not reliable, we have no job security, we get work 1 day and the other day we can't (…) recently there are foreigners who work in the construction business, such as Bangladeshis and others from African countries. Before there was no such competition, and the work was 90% reliable. So, nowadays livelihood is not reliable as before.” Another man in Shabelle similarly commented,

In Garowe, the livelihood has changed in the last few years. In the past we had ample work opportunities, and we used to earn a good daily wage up to 100,000 Somali Shillings. But now the living cost has increased, and the work opportunities have decreased. This is caused by many foreign workers who came to the town. The construction business is dominated by companies and such companies hire foreign workers. If you go through the camp, you will see hundreds of skilled youths who can't find work.

As noted for housing, the clans and nepotism played similar roles in determining livelihoods and wider economic support, but only when it comes to higher paying levels in government, NGOs, or businesses. An example of this includes the Rahanweyne in Garowe as mentioned earlier. Clan connections allow displaced Rahanweyne to mobilize resources to travel large distances to Puntland, bypass camps, and find well-paying jobs from their kinship ties. Alternatively, most IDP sites act as labor reserves full of low-paid casual laborers, which are exploitable and competition for jobs is fierce. However, unlike in other cities in Somalia (Al, Al), clan connections were less important in obtaining these precarious jobs. Access to employment was a particularly important factor in people's desire to leave the camp for those renting (rather than owning or occupying) their accommodation, as the inability to pay rent put them at high risk of eviction.

Housing

A crucial area of chronic instability and a key obstacle to integration is the insecurity of housing and the persistent fear of eviction. One woman in Garowe stated, “We are not the owners of the land; it belongs to the local people. It's a challenge when they tell us to leave; we have nowhere to go.” Similarly, a woman in Fanole camp, when asked if she considered herself an IDP she replied, “Yes, because this is not my land. If you are told to move, we will. This land belongs to other people who allowed us to build. They can evict us anytime of their choosing.” Although they did not explicitly say so, these comments relate to the power that comes from connections to clans in power at the area of displacement. This is evidenced by the privileged displacement site of Bilan. Due to clan affinity in government, these people displaced by the tsunami were quickly granted permanent land and housing, which they have leveraged to full integration into Garowe.

Housing has a direct impact on IDPs' physical, emotional, and mental wellbeing, as well as their capacity to feel “at home.” Physical size, durability of materials, and ownership are all markers of appropriate housing, but people frequently talk about the social and cultural importance of housing (Ager and Strang, 2008, p. 171–172). Ownership emerged as an acute concern and many participants expressed a desire to acquire property on which to build modest houses. Our surveys reveal that those who live in rental houses are 2.093 times more likely to be planning to leave due to their inability to pay monthly rent. Similarly, people who occupy their homes but do not pay any rent are 1.770 times more likely to say they are planning to leave compared to the people who own their houses. In the qualitative data, participants emphasized the significant role of housing in their lives, identifying it as one of the reasons for self-identifying as “displaced.” One participant explained, “I have no shelter. I live in another man's land, where I built a tent. My condition may have improved, but still, I am an IDP because I don't have permanent shelter. I have no land or a house to my name.”

Even those who had lived in cities for a long time continue to feel displaced, owing mostly to inability to own a house and land. This article does not have the space to analyze the complex idea of “home.” A quote in the “Foundations” Section shows that some feel at home simply by being in Somalia, while other displaced people often spoke of the feeling of displacement being tied to the quality of physical structure they live in. One participant in Shabelle told us “I live in a makeshift shelter. I can't live in the town. I can't afford to live there. If Puntland government—since I lived here for 25 years—gives me land where I can build a home, then I would not consider myself as an IDP.” Participants drew attention to the relationship between their status as IDPs, their persistent lack of secure accommodation, and their grievances regarding the resettlement process as demonstrated by this elderly man in Jilab:

This housing project was built by the Faroole administration. It was given to someone, and now it is owned by someone else. I asked some man I know to allow me to live in this house because I can't pay rent. He gave me the house. I pay him when I could. He calls me sometimes and asks for his rent. I tell him sometimes that I don't have anything. So, in general, we are IDPs. We have nothing. We live in tough conditions. But still, thank God for everything.

The daily experience of persistent eviction threats was a primary cause for IDPs to contemplate leaving. Specifically, in IDP camps in Garowe such as Shabelle, where an informal agreement has been in place between private landowners and the municipality, the value of the land has grown exponentially. This further contributes to the eviction demand of the landlords as explained by a woman there: “We have settled down here after all of the challenges we faced. We now have challenges in the land where we reside. We are urged to leave because the owner of the land died and now it belongs to the orphans and they want to share their inherence.”

Such accounts clearly differ from those IDPs who have been provided with housing. Many of these demonstrate a heightened sense of belonging to the community and no longer see themselves solely as IDPs. One woman in Jilab told us, “After a house was built for us, now I feel like I'm at home. We are Somali people living in our land. I see no problem.” Similarly, another woman in New Kismayo stated “Before I was an IDP, but, since I got this room, I believe I am no longer a displaced person. And I feel blessed.”

Education/health

Education and health are important markers and means of integration for our informants, however, we group these categories together because we did not find these services as primary drivers for people's decision to stay or remain in the displacement sites, apart from returnees from Kenya who experienced quality education in refugee camps. This resonates with Phillimore and Goodson's (2008, p. 318–319) findings, which notes, “the issue of health was only really a concern to those individuals who had some kind of health problem and, in that respect, it is a latent need that is not considered until respondents experience a problem”. Moreover, unlike the other markers and means, clan dynamics did not contribute directly to accessing education or health resources, but rather individual households mobilized their own kinship and clan-based networks for money contributions for education and health purposes.

Our research shows that a significant proportion (76.6%) of IDPs lack access to formal education due to their origins in rural and nomadic areas where the education system is poorly functioning or non-existent. As such the informants generally had positive things to say about education amidst displacement. All five study areas possessed schools, although there were notable differences in terms of capacity and educational quality. For instance, in Garowe, Shabelle and Jilab have primary schools that reaching grade 7 in the Somalia education system. However, to complete grade eight, students had to transfer to schools elsewhere outside the camp. In Kismayo, the educational landscape varied significantly. The New Kismayo area boasted a fully functional primary school, while Fanole informal camp had a smaller makeshift single hall primary school. As with housing, interviewee pointed to the importance of money in having a quality education beyond basic primary school:

While in Kelafo, we lived in the countryside, the education was poor, but if children were taken to the town they got better education, even better than here. Here in Garowe, education is very expensive, the textbooks are very expensive. So, you can't afford to get educated. If a single child goes to education, he is charged $40 for tuition, and she is in 8th grade, if you don't pay the child is thrown out of school. So, education has become unaffordable.

Health concerns were also prominent in our qualitative data, and like in the quote above, participants actively associated their ill-health with the stresses of displacement, including inadequate housing, lack of employment, and the limited access to nutrition and affordable healthcare. One participant in Garowe commented that, “diseases are caused by social problems, stress, poverty and lack of stable life.”

The health system in Somalia has been characterized as, fragile, underfunded, insufficient and inefficient, although there have been gradual improvements in health systems strengthening and expanding access to health care in recent years (WHO, 2010). In line with the Somalia government's official health-service priorities under the Essential Package of Health Service 2020 (EPHS)—which was designed to address healthcare needs of vulnerable populations including IDPs—there are health centers in every settlement, which provide primary health service including maternal and child health, nutrition, and outpatient services. Similar to the responses on education, many participants stated that they had very little access to health services prior to displacement (apart from those fleeing from Kelafo town in Ethiopia where the government provided more education and health services) and healthcare and camps were seen as an improvement. A man in Shabelle told us, “Here is a good place for children's education and health. MCH [maternal and child health] is also found here. And if you take the patients to a general hospital, they are accepted. Education and health care are better than where we were displaced.” Some IDPs identified previous healthcare barrier as the reason for their displacement, including a woman in New Kismayo who stated, “I got so sick in Umbareer [southern Somalia] and then I was brought here [Kismayo].” However, healthcare, like education, comes at a cost as this quote from a woman in Jilab indicates: “Here you must pay for everything, and you don't have money every time. Even if you need a match you must buy, debt is not allowed nowadays, the situation is very tough.” Another woman commented “Garowe is the best in terms of health care availability, because here medications are available, although it is paid for by the patient. However, in terms of doctors, availability of medications, and quality of health facilities, Garowe is the best.”

Social connections again emerged as highly important, as family or wider clan members frequently contribute to payments for healthcare and offer guidance on where to seek help. Notably, women were more likely than men to comment on the importance of education in interviews, indicating the gendered aspects of displacement and integration. The impact of a lack of local social connections was apparent when people tried to seek assistance through formal camp structures, as demonstrated by one female participant in Garowe. When asked about seeking healthcare, responded, “It is required for the camp manager to connect you with those organizations; I doubt he would do so for me.”

In contrast to this discussion above, those who repatriated to Kismayo from Kenya uniformly spoke of better education and health in the refugee camps in Kenya. As one woman in Midnimo noted, “This country is my country first and there is nothing better than a person's country, but life and education were good for us where we were (refugee camp in Kenya).” Even though the returnees have better housing than most IDPs in New Kismayo, some of them still prefer to go back to refugee camps largely due to better access to education. As one woman declared: “Yes, if there was a chance to go back, I would have gone back because there were very good education opportunities for the children there. I even wish to go back because of that.” Others reported that they had left their children in the refugee camps to complete their education. Returnees reported similar experiences about healthcare in Kenya as one woman shared: “Kenya was better in terms of health and education (…) I am in my country, and we have to pay money for the schools and health services.” Although education and health clearly impact the experiences and future opportunities of displaced people, apart from some returnees, these were not the most motivating factors people cite as reasons for wanting to leave.

Conclusion

Focusing on five formal and informal sites of displacement across Garowe and Somalia, this article joins the growing chorus calling for an expansion of understandings of migrant and refugee integration beyond the Global North. We engage with the influential domains of integration framework categorized by foundation, facilitators, social connection, and markers and means introduced by Ager and Strang (2008). Our contribution builds on yet nuances these debates by including internally displaced migrants (including Somalis crossing the Ethiopian-Somalia borderland) and refugee returnees—groups that have not been part of integration discussions. Furthermore, we conjoin integration literature, which often runs parallel to, rather than in conversation with durable solutions and local integration debates from the academic and policy field of forced migration. Similar analysis could be done in other Global South contexts to comparatively reflect on the efficacy domains of integration have in other situations.

From these analytical efforts, we argue that domains of integration is a useful framework to understanding processes of integration for displaced people in Somalia, yet we agree with recent critical research that integration in the Global South blurs and collapses across Ager and Strang's (2008) integration categories. This requires a renewed understanding of the relationship between citizen and state (Landau and Bakewell, 2018; Abdelhady and Norocel, 2023). While Somalia is often epitomized for state failure or collapse, Kismayo and Garowe have experienced relative stability and state building progress. Moreover, despite Somalis sharing common language, culture, and religion, control over the decentralized municipalities and federal states of Jubaland and Puntland remains largely influenced by clan politics. Thus, Ager and Strang's framework is useful in mapping how clan networks, which cut across bridges, bonds, and links in the social connection domain also holds significant power and salience over the foundation (rights and citizenship) and markers and means (employment, housing, education, and health) of society. Hovil and Maple (2022) argue for the centrality of citizenship in ensuring the durability of local integration. However, durability for internal displacement requires an understanding of citizenship in relation to clans and area-based belonging, which differentiates access to foundational rights and key markers such as employment and housing—the primary drivers influencing people's decisions to stay or leave IDP settlements.

This case study offers key policy insights for the protracted nature of displacement in Somalia and beyond. Across all sites, access to health and education are limited to the basic level, where higher incomes are required for specialized care and further education, which are an improvement for most displaced from rural areas. As such, healthcare and education does not significantly factor in their decision stay or go. For returnees from Kenya, however, these services are vastly degraded compared to the Kenyan refugee camps, which makes some long for a return to these opportunities. One of the most durable markers to stay was based around housing and land.

The sites of Fanole in Kismayo and Shabelle in Garowe suffer from informality and precarity, which diminishes their prospects of integration. As “outsiders” to the local clan structures, Fanole and Shabelle IDPs were allowed to be occupiers of privately owned land and are now facing eviction due to the rising value of land through rapid urbanization. Due to lack of stable housing or strong clan connections, many informants expressed still feeling displaced, despite residing there for many years. Alternatively, residents of Bilan, in Garowe displaced by tsunami, tapped into clan networks in the government acquiring permanent housing and land rights. Residents of the first Jilab camps were also given housing and land like Bilan, but many complain that camp leaders ensured non-displaced local clan members were given some of the homes. Moreover, many residents of Jilab and Bilan have since integrated into the city and now rent to newly arrived IDPs who are at risk of eviction due to lack of employment and ability to pay rents. Midnimo, or New Kismayo, with heavy financial and logistical investment from international donors, shows that durable solutions can transcend clan salience by ensuring land and housing rights in a well-connected part of the city. This approach must be cautioned, however, as a similar scheme in Kismayo, Luglow, due to its lack of spatial integration to the city, has been far less successful thus far. This shows that international donors have a role to play beyond recurrent humanitarian subsistence, although it is costly and requires buy-in from the local government.

Looking forward, prospects for integration will remain fluid. Land values are likely to increase across the country if stability endures, which will likely lead to further evictions displacing new settlements further to the outskirts of the city, especially for those from outside the clans in power. Urbanization is also globalizing cities such as Garowe, which makes finding employment among IDP camp “labor reserves” increasingly difficult due to the arrival of foreign companies and workers accepting lower wages (Bakonyi, 2021). On the other hand, democratization in Puntland has seen IDPs elected to local parliament and makes IDPs without local clan affiliations a potentially power constituency worth courting. In this sense, we find it important to remember that integration is a process and not a measurable endpoint, and that the durability of protection will be dependent on stability across the integration domains.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Edinburgh Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MA-S: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. CB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. LL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. SM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. AJ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project is publicly-funded academic research, supported by a grant (reference number ES/T004479/1) from the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) via the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) Development-based approaches to Protracted Displacement scheme.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincerest gratitude to the research assistants who played a vital role in supporting the data collection process. In Garowe, these individuals were Mohamud Adan Ahmed, Omar Yusuf Ahmed, Mohammed Fahim Bishar, Muna Mohamed Hersi, Anisa Said Kulmiye, Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud, and Amina Mohamed Nor. In Kismayo, we are grateful for the valuable contributions of Abdurham, Ayan Issack Hussein, and Ibrahim Hassan Hussein. Additionally, we would like to express our thanks to the research participants for generously sharing their time and knowledge and experience on the subject matter.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Al-Shabaab also receives local and clan-based support in its strongholds and the Somalia government forces also displaces people in the other direction deeper into Al-Shabaab-controlled territories (Mubarak and Jackson, 2023).

2. ^See Fiddian-Qasmiyeh et al. (2014) for primers on each of these aspects of durable solutions.

References

Abdelhady, D., and Norocel, O. C. (2023). Re-envisioning immigrant integration: toward multidirectional conceptual flows. J. Immigr. Ref. Stu. 21, 119–131. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2023.2168097

Ager, A., and Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: a conceptual framework. J. Ref. Stu. 21, 166–191. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fen016

Ahmed, A., Mohamud, F., and Wasuge, M. (2023). Examining the Durable Solutions Capacity in Kismayo and Afgoye. London: EU Trust Fund for Africa (Horn of Africa Window) Research and Evidence Facility, 35.

Al, J. (2023). Dozens Killed In Somalia's Puntland After Parliament Debate. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/6/20/fight-erupts-in-somalias-puntland-region-after-parliament-debate (accessed October 23, 2023).

Alba, R. D., and Foner, N. (2015). Strangers no More: Immigration and the Challenges of Integration in North America and Western Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bakewell, O. (2008). Research beyond the categories: the importance of policy irrelevant research into forced migration. J. Ref. Stu. 21, 432–453. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fen042

Bakonyi, J. (2021). The political economy of displacement: rent seeking, dispossessions and precarious mobility in somali cities. Global Policy 12, 10–22. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12849

Bakonyi, J., and Chonka, P. (2023). Precarious Urbanism: Displacement, Belonging and the Reconstruction of Somali Cities. Bristol, UK: Bristol University Press.

Besteman, C. L. (2016). Making Refuge: Somali Bantu Refugees and Lewiston, Maine. Durham: Duke University Press.