- 1School of Sociology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

- 2School of Geography, Development, and Environment, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

- 3Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, United States

Housing is a widely recognized yet understudied domain of integration of internally displaced persons (IDPs) into their new communities. This article examines the role of housing for integration of Ukrainian IDPs displaced by Russia-fueled political violence in Eastern Ukraine that started in 2014 or by Russia's annexation of Crimea that year. In Ukraine, housing holds particular significance for integration because homeownership is both widespread and a vital source of people's sense of wellbeing, security, and normalcy. Our evidence comes from an original 2018 survey of housing experiences of both IDPs and long-term residents in IDPs' new localities. The survey design enables us to assess housing integration relationally, by comparing gaps in housing status and subjective housing-related wellbeing between IDPs and locals. We find that for IDPs in protracted displacement, deprivation of culturally normative housing conditions, particularly homeownership, impeded both material and experiential housing integration. Disparities in housing status drive differences in subjective experience, ranging from satisfaction with one's housing to feeling at home in one's community. These results from our 2018 study may help anticipate challenges of the massive, nationwide displacement crisis precipitated by Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Whether Ukrainians resettle in new communities or return to their old ones, divisions between those who have homes to return to and those who do not are likely to be salient. Policies aimed at restoring housing resources, particularly pathways to homeownership, will be essential to rebuilding Ukraine.

1. Introduction

This article investigates the significance of housing for the integration of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Ukraine, most of whom fled fighting in the eastern “Donbas” region between Russia-backed secessionists (often with direct participation of Russian forces) and Ukrainian troops that first erupted in 2014. Acquisition of decent housing with secure property rights is “one of the most symbolically and practically meaningful elements of local integration” (NRC, 2011). The International Organization for Migration (IOM) defines integration as a “dynamic two-way process that involves mutual adaptation of migrants and the host society” (IOM, 2012). In this spirit, we assess housing integration relationally, by analyzing differences in housing experiences between IDPs and other residents of the same localities (henceforth: “locals”), and interpreting gaps as evidence for lack of integration.

Using an original survey of IDPs and local residents in 2018, we assess differences in their housing status, a multi-dimensional construct consisting of housing tenure, quality, and quantity, reflecting positions in a housing stratification order (Zavisca and Gerber, 2016). We find large gaps in housing tenure between IDPs and locals, and more moderate differences in housing quantity and quality. Ukraine is a “homeowner society”: following mass privatization of Soviet housing stock, 90% of Ukrainians came to own their homes, as did most IDPs prior to displacement. Although a few IDPs had managed to acquire homes of their own within 4 years of displacement, most dwelled in private rentals with no feasible pathways back into ownership, due to the lost value of their former homes and lack of affordable housing finance.

To further understand housing as a domain of integration, we assess the relationship between housing status and subjective housing-related wellbeing (SHW). Stratification researchers increasingly consider the distribution of subjective wellbeing, not only of material resources, in evaluating the health of economies and societies (Diener et al., 2018). Likewise, we argue that full housing integration requires convergence of IDPs and locals in SHW. We evaluate a range of indicators of SHW, ranging from those most proximal to housing status—satisfaction with housing conditions and sense of autonomy at home—to more distal—the ranking of housing among other problems people face, and the sense of being at home in one's community. We find that the various dimensions of housing status significantly impacted SHW, and (net of controls) accounted for much of the gap in SHW between IDPs and locals. This suggests that IDPs and locals value the same aspects of housing, and that closing gaps in material housing status—especially homeownership—would largely close gaps in SHW.

Since we conducted our research, Ukraine's displacement crisis has escalated dramatically due to Russia's full-scale invasion in February 2022. As of October 2022, around 7.7 million Ukrainian refugees had fled to Europe, and another 6.2 million were displaced within the country (UNHCR, 2022). Yet the ongoing trauma of Russia's 2022 assault should not make us forget that Ukraine's IDP crisis has been ongoing since 2014, when 1.8 million people were internally displaced due to the war between Russian-backed separatists and Ukrainian forces in the eastern Donbas region and the annexation of Crimea (Mykhnenko et al., 2022). By 2015, Ukraine was already among the ten countries with the largest IDP populations in the world (UNHCR, 2015), and the country with the largest displacement of people in Europe since World War II. Despite this, until recently Ukrainian IDPs have been less visible and less studied than other displaced populations (Mitchneck et al., 2016).

Though current displacement within Ukraine is tragically vaster in scope and scale, there are lessons to be learned from our 2018 study. Whether Ukrainians resettle in new communities or return to their old ones, divisions between those who have homes to return to and those who do not will likely persist. Housing trajectories of those who lost their homes will be profoundly consequential for recovery and integration, with potential major effects on social stratification and quality of life. Research on the housing experiences of the prior wave of IDPs can inform plans for reconstruction following the current crisis in Ukraine.

2. Housing as a domain of IDP integration

Because shelter is central for the human security of forced migrants, housing understandably has received extensive attention in the scholarly literature on refugees, asylum seekers, and IDPs. Ager and Strang (2008) posit housing as one of several means to and markers of integration. Yet housing is less focal in the literature on integration than issues such as employment, education, social capital, and citizenship (Strang and Ager, 2010; Donato and Ferris, 2020). Research on housing and forced migration tends to frame housing as a humanitarian need; a domain of legal protection to secure rights to shelter, land, and property; or a policy challenge and stressor for receiving communities. Examples of areas of analysis include containment and exclusion in refugee accommodation (Kreichauf, 2018; Kandylis, 2019); the impact of forced migration on local housing supply and prices (Becker and Ferrara, 2019); the relationship between housing and health for forced migrants (Ziersch and Due, 2018); and methods for assessing housing quality for the displaced (Yamen et al., 2022).

Yet housing is more than a physical shelter or an economic asset. Boccagni (2016) argues that for international migrants, research on homes should focus on issues of belonging, not only on physical structures. Belloni and Massa (2022) introduce the concept of “accumulated homelessness” to shift attention from the physical aspects of shelter for forced migrants to the emotional aspects of home such as security and familiarity. Brun and Fabos (2015, p. 7) discuss how forced migrants experience home “as a site in which power relations of the wider society...are played out.” This perspective dovetails with recent calls for migration scholars to consider subjective wellbeing and life satisfaction as key to integration into host communities (Paparusso, 2021; Williams et al., 2021).

Despite housing's significance, there are few studies that center housing as a domain of societal integration specifically for IDPs. A growing literature examines housing integration of refugees and asylum seekers (Phillips, 2006; Fozdar and Hartley, 2014; Nielsen et al., 2015; Czischke and Huisman, 2018; Adam et al., 2021). However, as the limited literature on IDP integration suggests, housing may matter for IDPs in different ways than for refugees and asylum seekers who cross international borders. In contrast to refugees, most IDPs are citizens living among their compatriots, infusing housing with particular social and political meaning for integration of the displaced. It may be hard to feel a sense of local belonging when living in long-term temporary shelter typical of protracted displacement (Kabachnik et al., 2010). Socially, the question is whether physical housing is transformed into a sense of home, which entails feelings of security and belonging (Brun, 2015).

Because IDPs remain in their home countries, their host communities are likely to bear socioeconomic, linguistic, and cultural similarities to their origin communities. Although this could ease integration, it could also intensify experiences of exclusion and injustice. The sense of displacement may be exacerbated by dwelling among locals whose current circumstances closely resemble IDPs' pasts but are unattainable to IDPs in the present. Lacking a culturally normative dwelling can impede sociability and lead to social marginalization of IDPs (Roth, 2013). Politically, citizenship rights that are tied to place of residence, such as voting, become difficult to exercise, as do other forms of civic engagement that require permanent residential status in a community (Koch, 2020). In sum, housing is a necessary (but not sufficient) resource for full societal integration of IDPs. This is especially true in societies where the social contract is predicated on having secure housing, as is the case in many post-Soviet countries (Zavisca, 2012; Zavisca et al., 2021).

3. The study context: Housing and displacement in Ukraine

3.1. Ukraine's housing system: A post-Soviet homeownership society

Ukraine and other post-Soviet countries have among the highest homeownership rates in the world, largely without mortgages (Schwartz and Seabrooke, 2008; Mandič, 2010; Stephens et al., 2015). As of 2015, 90% of Ukrainian adults lived in owner-occupied homes (Zavisca et al., 2021). This is a result of Soviet housing policy and mass post-Soviet privatization. In the 1950s, Khrushchev promised to provide a separate apartment for every nuclear family. This ambitious plan was not fully realized, as waiting lists for apartments stretched for years, but millions of families experienced radical change within a generation. By the close of the late Soviet period, most urban Ukrainians lived in state-owned apartments, while rural Ukrainians continued to dwell in low-quality, self-built houses. Soviet citizens had durable rights of residence and exchange (but not of sale for profit) and came to think of these dwellings as their own. Property rights, while limited, were secure. In short, a separate apartment for the nuclear family became a critical component of the Soviet social contract, and the centerpiece of a so-called “normal life” (Zavisca, 2012).

When the Soviet Union collapsed and Ukraine became an independent country, the new government initiated mass privatization to the occupants of socialist housing, creating the chief source of household wealth in the new economy. Ownership rights over the existing private sector—mainly rural, dilapidated homes—were also formalized. At the same time, the state drastically reduced its role in producing and distributing housing: by 2013, a residual waiting list remained, but allocation rates plummeted to only 3% of the 1990 rate. Yet the private sector has had limited capacity to produce affordable housing. As of 2013, over 90% of the housing stock had been constructed prior to 1990 (UNECE, 2013). As a result, most residents live in housing allocated initially by the state, acquired through privatization, and subsequently redistributed through familial and market exchange (Gerber et al., 2022).

Market exchange is limited mainly to direct purchase and sale. A fledgling mortgage sector was decimated by the 2008–2009 global financial crisis and the 2014 post-Maidan economic crisis (Burdyak and Novikov, 2014; Manzhos, 2016). As of 2015, the mortgage-to-GDP ratio was < 1% (Kharabara, 2017). Although housing prices fell with the crises of the past decade, so did incomes, rendering housing unaffordable out of labor market earnings (UNECE, 2013; Mezentsev et al., 2019). Poor development and regulation of rental markets further restricted market-based housing mobility. Thus, the Ukrainian case resembles less an asset-based welfare system than a pre-commodified family-based one, as is characteristic of much of Southern Europe and post-socialist Eastern Europe (Mandič, 2010; Delfani et al., 2014).

This high rate of homeownership, coupled with low housing affordability and deep retrenchment of public housing provision and other social protections, means that mortgage-free ownership is essential to social welfare. Unencumbered ownership, by reducing housing costs to families, has acted as a buffer against unemployment, currency fluctuations, and repeated economic crises in the post-Soviet era. In such contexts, lack of homeownership has profound consequences for wellbeing (Zavisca et al., 2021; Gerber et al., 2022).

3.2. Accommodating displacement in Ukraine's housing system

Mass displacement from the Donbas region (and, to lesser extent, from Crimea) began in 2014. Ukraine's pro-Russia president, Viktor Yanukovich, was overthrown by popular uprising in Kyiv and fled to Russia. Russia then seized (and eventually annexed) Crimea by force, and Yanukovich supporters in the eastern Donbas region, backed by Russian weapons (and eventually personnel), took up arms against the Ukrainian government, declaring independent republics in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. Kyiv sent forces to attempt to defeat the separatists and restore full control over Donetsk and Luhansk, resulting in intense combat in 2014 and 2015. The combat reached a stalemate, ultimately yielding a ceasefire that left large parts of the two Ukrainian oblasts outside of Kyiv government control. Sporadic episodes of fighting continued in subsequent years. Although some fled Crimea after it was annexed, the most massive wave of internal displacement consisted of those fleeing the NGCA during and following the war there in 2014 and 2015.

Ukrainian IDPs overwhelmingly resettled into the existing housing stock in their new communities. Collective settlements played a minor and transient role in IDP housing; new housing was not built specifically for the displaced. Voluntary organizations provided limited assistance, and some of the most vulnerable populations were resettled into social housing (typically government-owned hostels and dorms). Ukraine did re-purpose structures such as summer camps, sanatoria, dormitories, and storage facilities, but generally only for the immediate emergency period as short-term shelter. Ukrainian government benefits for IDPs, especially related to housing, have been meager, and humanitarian assistance from NGOs waned over time. This limited infrastructure and aid left most IDPs in Ukraine to settle themselves into private rentals or with extended family (Dean, 2017).

This approach stands in sharp contrast to Georgia and Azerbaijan, the two other post-Soviet countries with the largest number of IDPs, whose conflicts occurred much sooner after the breakup of the Soviet Union. Those countries housed IDPs in collective centers and existing housing stock for protracted periods and, with substantial international assistance, built new housing settlements for some of the displaced. During our field research, government officials as well as representatives of NGOs involved with IDP resettlement noted that Ukraine did not use collective centers as temporary shelter to the extent as did Georgia because of concerns that temporary solutions would become permanent. Some describe Georgia's new settlements as “slums” segregating IDPs from the local population (Dunn, 2012); international humanitarian aid organizations and policy communities advised against repeating the Georgian settlement policies because they believed that moving into existing local housing stock would better facilitate integration. Mitchneck et al. (2009) found, however, that Georgian IDPs living in the local housing stock were not necessarily more socially integrated into the local host communities than people living in collective centers, and many women in private accommodations were more socially isolated.

Ukrainian IDPs moving into existing housing stock—mostly private rentals—were disadvantaged from the get-go for several reasons. Rental housing stock is often of the lowest quality. Tenant rights in Ukraine are weak. Landlords are reluctant to provide tenants with written contracts or to give them documentation needed to acquire a “propiska,” a residential registration needed to activate certain rights, including school enrollment, medical care, pension payments, and voter registration. A 2018 survey found that 95% of Ukrainians said they would not register tenants if they were renting out an apartment they owned, and 93% would not do so even if tenants agreed to a higher rent (Slobodian and Fitisova, 2019). IDPs were further disadvantaged relative to local housing markets because the housing left behind in the non-government-controlled areas (NGCAs) was often their only capital asset, rendered worthless. They could not sell those homes at prices sufficient to convert into capital for buying homes in their new places of residence. Furthermore, limited mortgage access and low wages made prospects for new ownership in displacement extremely poor. In addition, many IDPs have harbored the hope of return, in part because of housing assets, and moved to close-by areas. This proximity to previous communities allowed IDPs to cross into NGCAs periodically to check on housing and other assets left behind.

In sum, given the significance of housing for overall wellbeing and belonging in Ukraine, we expect housing will have played a large and negative role in IDPs' experiences. While IDP integration is more complex than housing status, we show in the following sections that in the Ukrainian context, housing status significantly differentiates the IDP experience from the local one. The local gaps in housing conditions between IDPs and their host populations contribute to lower senses of subjective wellbeing and belonging. We argue that the depth and breadth of divergent housing experiences hinder IDPs from integrating socially, economically, and civically. In particular homeownership, an expectation and reality for 90% of Ukrainians, is both a material and symbolic marker of incomplete integration for IDPs.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Data

Our core data source is the 2018 Ukraine wave of the Comparative Survey of Housing and Societal Stability (CHESS). This original survey interviewed 3,200 urban Ukrainians ages 18–49, including 1,600 IDPs and 1,600 locals, from January to March 2018. The survey was designed by the authors and carried out by SOTSIS, a Ukrainian survey research organization. Note the sample restriction to ages 18–49 is a limitation that reflects the goals of the broader project (a study of the relationship between housing, demographic, and political outcomes during the reproductive and workforce stages of the life course).

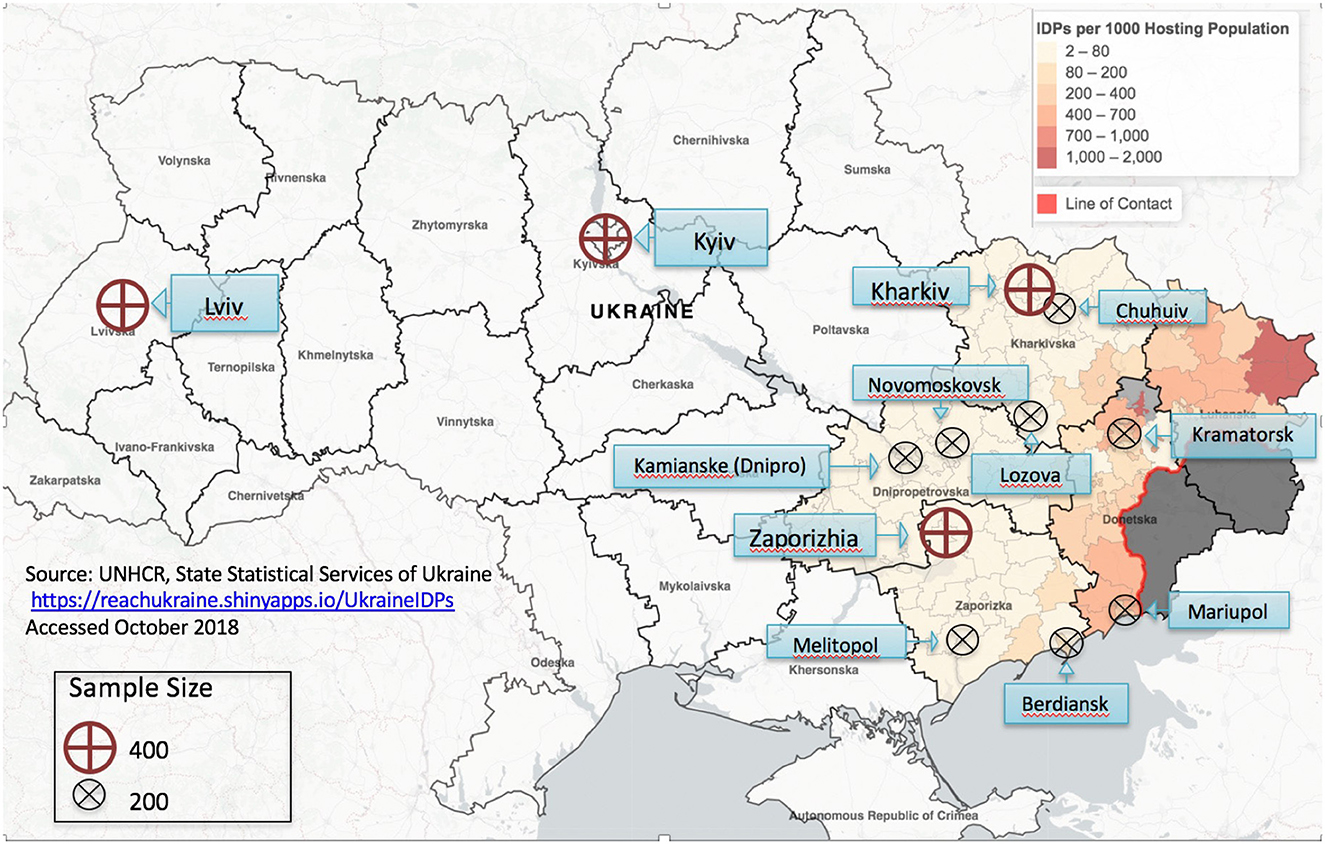

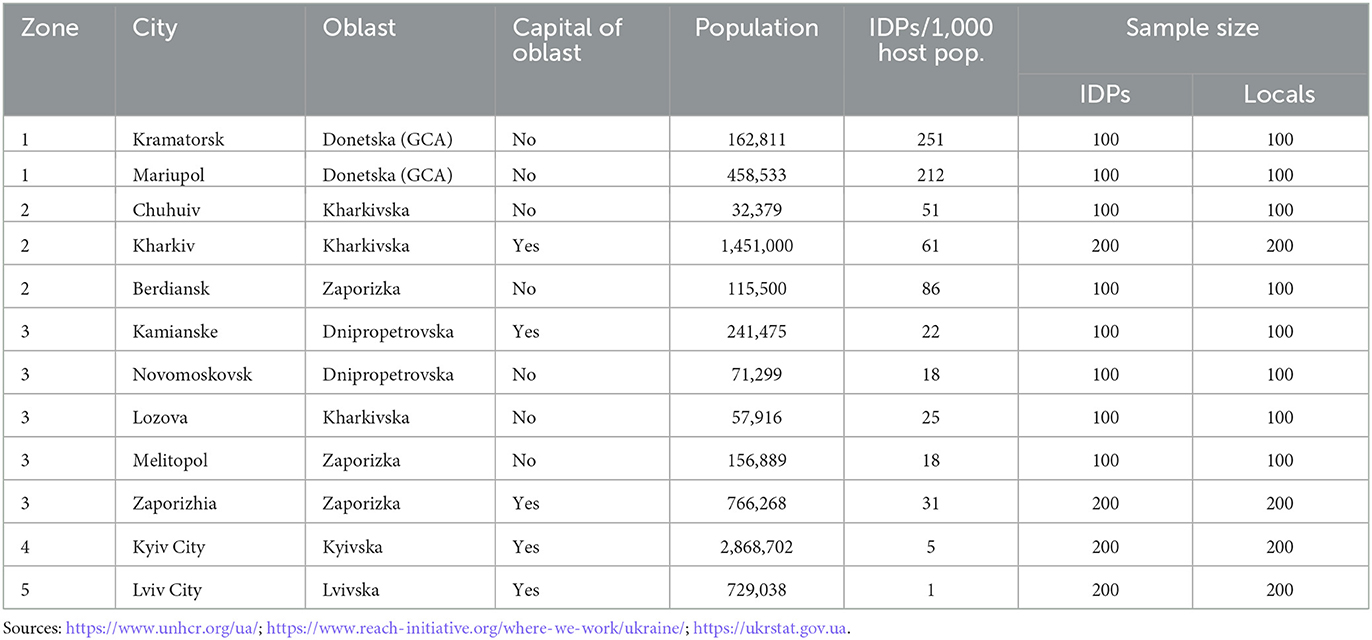

The 2018 CHESS survey sample is drawn from 12 urban settlements, which were selected purposively and are not nationally representative. Figure 1 depicts sampling sites on a national map of IDP density, while Table 1 lists the sample sites and their population characteristics. Most settlements were selected within four oblasts near the conflict zone, in which the vast majority of IDPs resided: Dnipopetrovska, Kharkivska, and Zaporizka, and the government-controlled area (GCA) of Donetsk oblast. Within these oblasts, settlements were selected to vary on type of place (oblast capital vs. other city), distance from the line of contact separating GCAs and NGCAs, and density of IDP populations. We further restricted sampled sites to those where SOTSIS has a field office with capacity to safely and expeditiously carry out fieldwork given conflict conditions. In addition, Kyiv and Lviv, the two largest cities in Ukraine that host sizable IDP populations and were distant from the conflict zone (at the time of the survey), were included.

Random local samples within each settlement were drawn using random walk selection of residential addresses, followed by random selection of one individual among eligible residents at the address. The random walk procedure was employed due to the lack of a reliable list of addresses for a sampling frame. Starting at the geographical center of election districts, supervisors were instructed to follow a specified random route (with turns at intersections also randomized) to choose addresses. Supervisors then provided interviewers with specific addresses. The local response rate was 24.4%. About half of the non-responses were due to refusal to participate (52%), with the remainder due to no one being home or inability to access the building after three attempts.

The IDP sample consists of a combination of IDPs encountered during random walk, referrals from the local sample (who were asked to provide contact information for IDPs who they knew), and purposive recruitment via organizations serving IDPs. The IDP sample is thus not a probability sample, which was infeasible given the lack of access to a suitable sampling frame (other scholars of IDPs in Ukraine also employ non-probability methods to survey this difficult to reach population: c.f., Cheung et al., 2019; Sasse and Lackner, 2020; Vakhitova and Iavorskyi, 2020). The response rate for the IDP sample is 38.2%. One-third of IDP non-responses were due to refusals based on fear of participation in the survey; with the remainder refusing for other reasons or being otherwise unavailable.

Our core aim was to compare housing status between IDP and local populations within the same settlements, not to obtain nationally representative samples for either population. It is possible that sampling error due to non-response and non-probabilistic sampling of IDPs introduced biases at the settlement level. However, the achieved sample demographic characteristics are reasonably close to benchmark comparison surveys (see Appendix Table A1 in Supplementary material).

Our questionnaire design is adapted from the 2015 CHESS survey, a comparative survey of housing experiences in four post-Soviet countries including Ukraine. We also draw on field research we conducted in 2015 and 2016 to inform the survey design. Qualitative data collection consisted of nine in-depth interviews and ten focus groups in five cities, including six focus groups with locals, three with IDPs, and one with returned migrants from Russia. In addition, we conducted expert interviews and observed events addressing Ukraine's IDP crisis hosted by international organizations (UNHCR, OIM, NRC, IRF, and US Dept of State); the Ukrainian government (Ministry of Social Policy and Ministry of IDP Affairs), and Ukrainian NGOs providing assistance to IDPs (Station Kharkiv, Proliska, Ukrainian Women's Fund, Crimea SOS, and WURC).

4.2. Analytical approach

Our analytical approach stems from our conceptualization of integration as the outcome of a dynamic process involving the local population and those IDPs who resettle there (IOM, 2012). We first compare indicators of material housing status—tenure, quality, and quantity—between IDPs and locals in 2018, viewing extensive gaps as markers of incomplete integration. We also compare these findings with IDP housing conditions in 2013 (pre-displacement) to document that IDPs' housing status mirrored those of locals before they were displaced. Next, we analyze gaps between IDPs and locals in their SHW, also important markers of integration in the housing domain. All observed differences between IDPs and locals are statistically significant, unless otherwise noted in the text (based on p < 0.05 for Pearson's Chi-square tests for contingency tables and t-tests for differences between means). Finally, we perform multivariate analysis to elucidate the relationship between material housing status and SHW. We demonstrate that material differences in housing status explain not only significant variation in SHW among IDPs, but also account for much of the gap in SHW between IDPs and locals. We further examine variation in housing gaps between IDPs and locals across geographic zones, which we define in terms of two socio-spatial elements: (1) IDP resettlement distance from the conflict zone and (2) the concentration of IDPs in the resettlement locations close to the conflict zone. Both proximity to origins and concentration of IDPs in the host community could impact prospects for housing integration. Higher concentrations of IDPs can mean more competition for scarce housing resources, but also stronger social networks and access to support that can facilitate housing access and integration. Geographic proximity or distance, as a proxy for cultural distance, could also impact capacity to integrate and feel at home. While we do find some variation, our key findings are consistent across zones, bolstering confidence that our results are likely to be generalizable across Ukraine.

To help interpret quantitative results, we provide illustrative examples of talk about housing status and SHW from our focus groups and interviews with IDPs. We select examples that resonate with the major trends found in our survey. Our aim is not a full-scale, systematic qualitative analysis, but rather to supplement and contextualize our survey findings in IDPs' own words.

4.3. Measures

4.3.1. Housing status

Our specific measures of each housing status dimension were developed for post-Soviet contexts through a comparative study of Ukraine Azjerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia. For a detailed explication of our concept of housing status and approach to measurement, see Zavisca et al. (2021). Our housing tenure measure classifies respondents as: respondent owners (personally on the title); household owners (respondent does not hold title, but other resident household members do); renters of private housing; tenants in public housing; residents of private housing owned by non-resident relatives or friends. Distinguishing respondent from household owners is important in post-Soviet settings, where intrahousehold inequality in property rights is both extensive and consequential (Zavisca, 2012; Zavisca et al., 2021).

We measure housing quality through two composite scales (ranging from 0 to 1). The “amenities” scale captures the home's physical characteristic: the presence of a toilet, bath, running water, hot water, heating, gas supply, and PVC windows. The “comfort” scale measures experiential aspects of housing quality: whether cold in winter or hot in summer, leaky, noisy, unsafe, or poor air quality. Finally, housing quality (space) is measured using the dwelling's square meters per capita, and whether the respondent has a room of their own where they sleep with only their partner and/or small children under 3. We measure these elements of housing status retrospectively to 2013 (pre-displacement) as well as contemporaneously to ascertain whether IDPs' housing status mirrored those of locals before they were displaced.

4.3.2. Subjective housing-related wellbeing

In prior research, we have employed two measures of SHW—housing satisfaction and sense of autonomy at home—to validate the salience of housing status for people's lived experiences (Zavisca et al., 2021; Gerber et al., 2022). Likewise, we employ these same measures here. Housing satisfaction is measured via a 5-category Likert scale response, from very dissatisfied to very satisfied, to the question “How satisfied are you overall with your home.” Housing autonomy is a scale (ranging from 0 to 1) that averages integer-scored Likert-scale responses to 3 questions on whether respondents feel that they can: get away from it all at home, do what they like at home, and control who lives in their home.

We also introduce two new measures of SHW that we expect to be especially salient for IDPs. First, we examine a dichotomous measure indicating whether respondents selected housing issues as among their top two main problems (from a list of nine choices). This measure demonstrates stark differences between IDPs and locals in the weight of housing in everyday concerns of Ukrainians, additional evidence that housing poses a barrier to IDP integration. Finally, we examine the degree to which IDPs vs. locals feel “at home” (vs. like guests) in the communities in which they live. A sense of place and belonging is especially significant in narratives of what displaced persons have lost and crave as they seek to integrate into new communities (Kabachnik et al., 2010; Chattoraj, 2022). Brun (2016) highlights how rented dwellings (or homes) become intertwined with identity creation distinct from shelter or status as an IDP. Our survey enables us to systematically analyze the role that material housing conditions play in this subjective sense of being at home.

4.3.3. Geographic zones

For purposes of geographic analysis, we divide the sample into 5 zones (see Table 1). Zone 1 is comprised of the two settlements selected from the GCA region of Donetsk oblast, which had very high concentrations of over 200 IDPs per 1,000 host population. Zones 2 and 3 are settlements in Dnipropetrovska, Kharkivska, and Zaporizka oblasts, which neighbor the oblasts with occupied territories. We divide these settlements into two zones based on IDP density: Zone 2 consists of high-density settlements (≥50 IDPs per 1,000 host population), while Zone 3 consists of lower-density settlements (< 50 IDPs per 1,000 host population). Zones 4 and 5 contain the cities of Kyiv and Lviv, respectively.

4.3.4. Other control variables

Multivariate analyses of the relationship between housing status and SHW control for other factors that could influence both housing status and SHW but are not analytically focal in this paper: gender (male/female); age; marital status (married; cohabitating; single and previously married; single and never married); education (less than secondary, secondary degree, and university degree); a scale of durable possessions (as a proxy for economic class, which is difficult to measure with current income or occupation in Ukraine); whether living as a nuclear family vs. with extended family or nonrelatives; and time since displacement (0–1, 2, 3, or 4 years).1 Descriptive statistics for control variables are given in Appendix Table A2 in Supplementary material. For further rationale and details on control variable specifications, see Zavisca et al. (2021), Gerber et al. (2022), and Perelli-Harris et al. (2022).

5. Results: Housing status

5.1. The homeownership gap

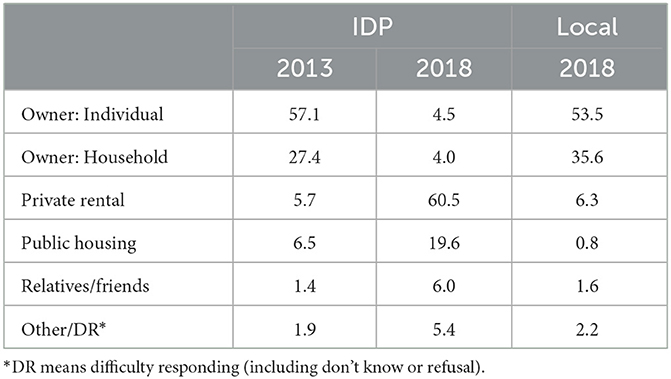

Gaps in housing tenure are the starkest indicator of the differences in livelihoods and life chances between IDPs and locals, as well as of IDPs' downward housing mobility relative to pre-displacement. Locals were ten times more likely than IDPs, 4 years after displacement, to be owners. As Table 2 shows, in 2018 nearly 90% of local respondents were homeowners: 54% were personally named on the title to the property, while 36% did not hold title but other household members did. By contrast, only 9% of IDPs lived in homes that either they personally (5%) or other household members (4%) owned. The majority of IDPs in our sample (61%) lived in private rental housing—vs. only 6% of locals. An additional 20% of IDPs lived in public government-owned housing, a sector that had virtually vanished for locals. Two thirds of those in public housing were living in hostels, which are generally of poor quality and originally intended for students or temporary workers.

What makes displacement in Ukraine distinctive is not that few IDPs are homeowners—we suspect that displaced persons globally are unlikely to become owners even after several years in displacement—but that almost everyone else is. In this homeowner society, both private and public tenancy are marginal and marginalized housing tenures (Bobrova et al., 2022b). These differences in housing tenure reflect extraordinary downward housing mobility of IDPs caused by displacement: in 2013, 85% of IDPs lived in homes that they or other members of their households owned. Thus, many IDPs would have experienced lacking homeownership not only as a contemporaneous disadvantage relative to their neighbors in 2018, but also as a daily reminder of what they had lost.

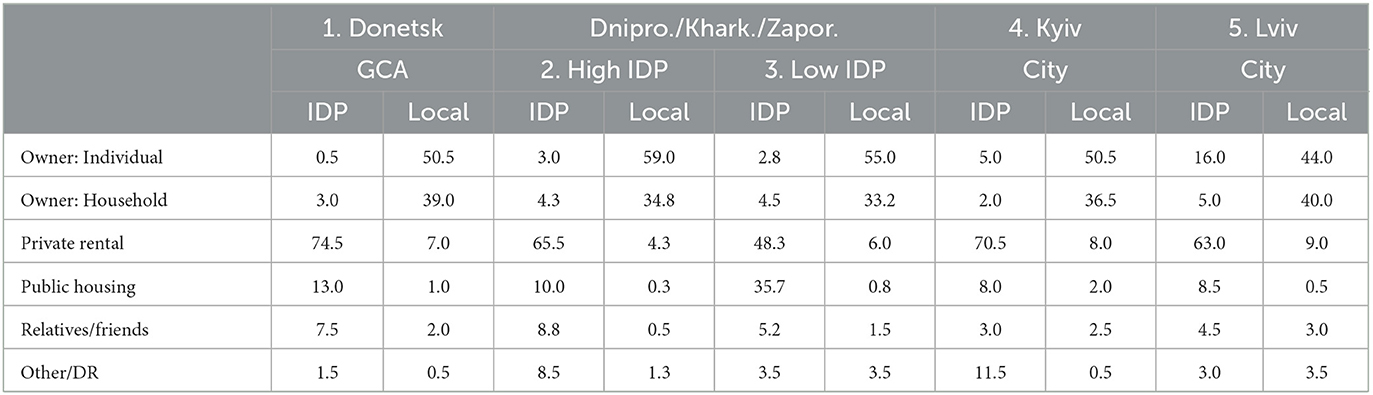

Table 3 compares IDP and local housing tenure in 2018 across displacement zones. The patterns of disparity across zones are fairly consistent, with IDPs much less likely to be homeowners, and much more likely to be renters. IDPs in Lviv were more than twice as likely as IDPs elsewhere to live in homes that they own. We attribute this unexpected finding to the greater distance of Lviv from the occupied regions whence IDPs were displaced, which makes Lviv a costlier destination, available mainly to IDPs with more financial resources or stronger family or professional networks there prior to displacement. Another notable (and statistically significant) difference is the relative preponderance of private renters vs. public tenants among IDPs in Zones 1, 2, and 3. Zone 1, adjacent to the NGCAs, has the highest proportion of private renters (75%), vs. 66% in zone 2 and 48% in zone 3. The rate of private renting across these three zones near the conflict decreases as IDP density decreases. Conversely, zone 3 has many more public renters (35%) vs. 10% in zone 2 and 13% in zone 1. Such localities appear to have had greater capacity to meet IDP demand for public housing, perhaps because there were relatively fewer displaced people in need.

Lacking homeownership drives insecure property rights for IDPs, who were typically unable to secure rental contracts or formally register their places of residence. Renters in Ukraine generally have limited rights and face high costs; this is especially true for IDPs. Among IDP private renters, only 47% had written rental contracts, vs. 64% of local renters. Likewise, only 38% of IDP tenants in public housing had contracts. IDP renters were also disproportionately concerned that they would be forced to move out of their residences: 35% of IDPs in our sample reported being somewhat or very worried, vs. only 11% of local renters. Surprisingly, however, IDP renters with rental contracts were about twice as likely to be worried (45%) as renters without written contracts (28%). Perhaps having a contract exacerbated worry because it put a formal fixed term with an end date on the tenancy agreement.

Private renting also exacerbated income precarity: although most homeowners in Ukraine do not have mortgage payments, tenants must pay rent. Housing costs in 2018 were relatively low for most Ukrainians: the average Ukrainian spent about half of household monthly income on food, and only 16% on housing costs (ukrstat.gov.ua). For the vast majority of Ukrainians who were mortgage-free homeowners, the only typical housing costs were utilities and maintenance. Renters, by contrast, would have had to allocate a much larger share of their monthly budgets to housing, for rent alone. Although we do not have data on housing-related expenditures, we do have a question on ability to afford a hierarchy of goods. Forty-two percent of surveyed IDPs reported they could not afford clothing or other durable goods, vs. 21% of locals. This gap correlates strongly with housing: the 9% of IDPs who were owners reported a similar distribution of purchasing power to locals.

IDPs' disadvantages were further compounded by their difficulty in acquiring a “propiska,” or local residential registration. A vestige of the Soviet internal passport system (Buckley, 1995), a propiska documents local residency and hence entitlement to services tied to local registration such as education and health care. Furthermore, prospective employers often verify whether job applicants have local propiskas. Renters may only acquire a local propiska with the consent of the owner. Yet landlords are often reluctant to register tenants, both for tax reasons, and due to concern that such documents could preclude eviction or sale. As a result, only 20% of IDPs in our survey had a propiska for their current place of residence, vs. 86% of locals. This disparity presented significant barriers to broader economic and civic integration. Among those IDPs lacking propiskas, this was reported to cause problems with voting among 47%, finding a job among 22%, and access to medical care among 11%. Note that propiska registration is distinct from IDP registration: 88% of surveyed IDPs were registered on government lists of IDPs, which entitled them to very modest income support and other services for a limited period. Yet IDPs needed to register in the locality twice to receive full voting rights. IDP registration without propiska registration carried voting rights only in national elections, not in local ones—denying access to a key means to civic integration (Solodko et al., 2017).

5.2. Housing quality and quantity

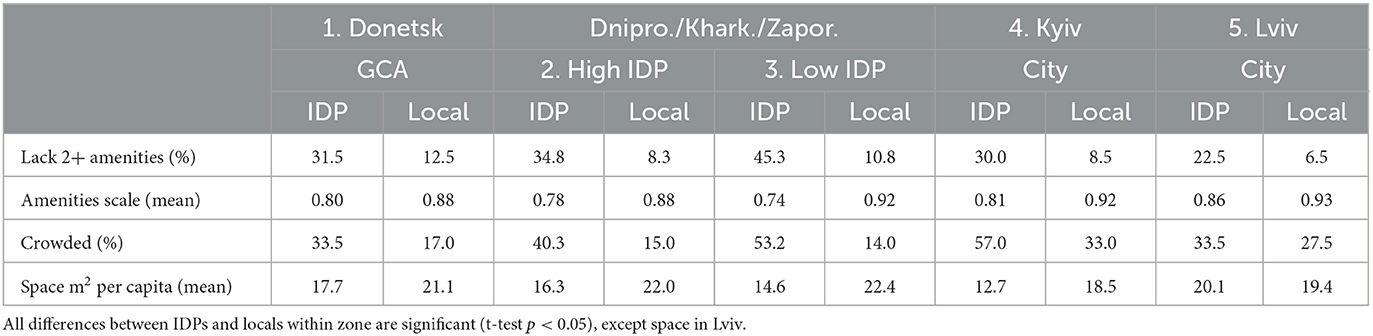

The housing gap between IDPs and locals extended to quality and quantity, although the disparities are less dramatic than for tenure. Table 4 measures quality differences in terms of access to a core set of amenities and environmental (dis)comforts. With respect to amenities, the largest quality gaps between IDPs and locals in 2018 were in having one's own kitchen, toilet, and bath/shower. This is due to the segment living in dorms/hostels with shared facilities. IDPs were also less likely to have double-paned polyurethane windows (so-called “plastic” windows) than were locals. Such windows are indicators of post-Soviet construction or renovation, which are more typical in owner-occupied homes than in rentals. As an overall indicator of poor housing quality, we examine whether at least two basic amenities were lacking. Here we see a much larger gap between IDPs and locals in 2018: 36% of IDPs lived in housing lacking two or more basic amenities, vs. only 10% of locals. We also constructed a scale of access to these amenities (normalized to range from 0 to 1) which takes into account both consistency and presence of amenities (see Zavisca et al., 2021). A substantively moderate (0.13, equivalent to a difference of about 1 amenity) and statistically significant gap between IDPs and locals is evident. As with tenure, these gaps in housing quality were a function of displacement: IDPs in 2013 had similar access to amenities as did locals in 2018.

Another set of housing quality measures captures what we call housing “comfort”—the degree to which respondents are free from a variety of common problems with environmental quality at home: leaky plumbing, poor climate control (being cold in winter or hot in summer), noise, poor air quality, and unsafe building infrastructure. There are no statistically significant differences between IDPs and locals either on individual measures, or in the housing comfort scale (based on the frequency and presence of problems, scaled from 0 to 1, c.f. Zavisca et al., 2021). Taken together, these two measures suggest that housing comfort differences are fairly minor, especially compared to the large gaps observed in homeownership. This likely reflects the fact that IDPs resettled into existing housing stock, not temporary structures (e.g., tents or barracks). In post-Soviet Ukraine, the majority of urban housing has most or all basic amenities; most housing is also older, and so environmental/comfort problems are relatively common, and apparently not disproportionately present in IDP's dwellings.

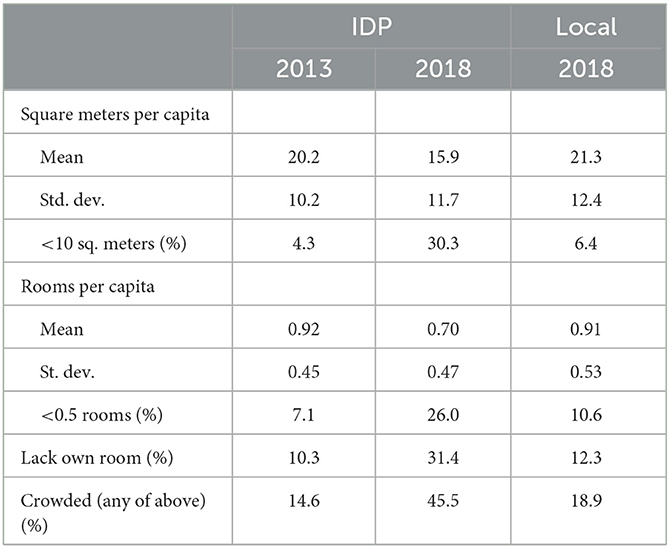

Turning to housing quantity, Table 5 shows that IDPs had, on average, less space and faced significantly more crowding than their local counterparts did in 2018. IDPs had only about two-thirds the space per capita as locals did. They were also significantly more likely to face crowding considered extreme by local norms (see Zavisca et al., 2021 for context). Among IDPs, 30% had fewer than 10 sq. m. per capita, and 26% fewer than 0.5 rooms per capita, conditions affecting only 6% and 11% of locals, respectively. Furthermore, 31% of IDPs did not have a room of their own within the household (defined as having a room for sleeping and personal use shared only with a partner and/or young child under 3), vs. just 12% of locals. Still, nearly half of IDPs (46%) experienced at least one form of crowding, in contrast to 19% of locals. Inferior housing quantity was a new disparity for most IDPs, driven by displacement, given that they did not have less space or more crowding as a group than locals in 2013.

Table 6 shows the variable IDP experience of housing quality and quantity across displacement zones. The patterns of disparity between IDPs and locals are generally consistent across zones: in each place, IDPs are significantly more likely to have fewer housing amenities and less space. That said, IDPs living farther from the NGCA, in Kyiv and Lviv, experienced housing differently from IDPs who settled closer to the NGCA. For example, residents of Lviv, including IDPs, were far less likely than IDPs elsewhere to lack basic amenities. On the other hand, the quantity situation was especially difficult in Kyiv, where space deprivation was more common for both IDPs (57%) and locals (33%). Zones closest to the NGCA (1, 2, and 3) had similar levels of crowding. IDP crowding is remarkably high in zone 3, where IDP concentration is lower than in zones 1 or 2, 3. This is counterintuitive from a socio-spatial perspective: we would expect IDPs to face more competition for scarce housing resources where they are more concentrated. Most likely, tenure differences explain this situation. As Table 3 shows, IDPs in zone 3 were far more likely to live in public housing (36%, vs. 13% in zones 1 and 10% in zone 2), which consists mainly of dormitory-style residences that are crowded and in poor condition.

In sum, incorporation of IDPs into local housing stock appears to have put people into conditions that, while substandard on average, satisfied basic shelter needs. The majority (63%) enjoyed a standard suite of utilities and amenities, and environmental quality conditions were on average equivalent to those faced by locals. Furthermore, just over half (54%) avoided serious crowding. Indeed, in the international humanitarian landscape of displacement, IDPs in Ukraine in 2018 were relatively well off—most were in shelters that provided adequate conditions to survive, if not to thrive.

Nevertheless, not only were gaps between IDPs and locals in tenure very large, quality and quantity conditions failed to meet local norms for significant proportions of IDPs. Importantly, pre-displacement (in 2013) housing conditions for IDPs had been very similar to those of locals in the localities to which they had been displaced in 2018. In turn, these analogous contrasts of IDPs' objective housing conditions with those of both their former lives and their contemporaneous neighbors led to large gaps in SHW and in feeling “at home,” as we show in the next section.

6. Results: Subjective housing-related wellbeing

We cannot infer IDPs' lived experience of housing integration from their material conditions alone; what matters is the degree to which their housing experiences met local norms in the Ukrainian context. To elucidate the relationship between housing and integration, we analyze gaps between IDPs and locals in their SHW, triangulating across a variety of measures relevant to integration. First, we examine subjective assessments of housing conditions, both overall satisfaction and sense of autonomy at home. Next, we assess the relative rank of housing among the overall problems that IDPs and locals faced. Then, we consider the degree to which respondents felt “at home” in their communities. For each measure, we interpret gaps between IDPs and locals as signs of incomplete integration. Illustrative examples from IDP focus groups and interviews illustrate the salience of housing status, and especially homeownership, for experiences of SHW. Finally, multivariate regressions statistically confirm that material housing status explain gaps in SHW both among IDPs, and between IDPs and locals.

6.1. Satisfaction and sense of autonomy at home

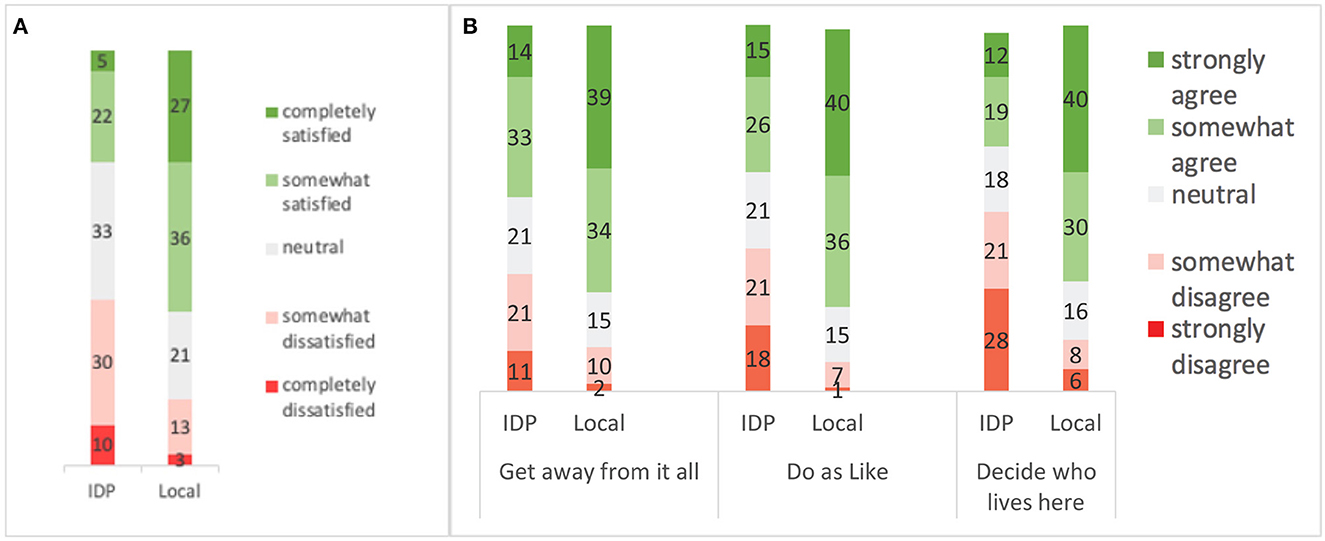

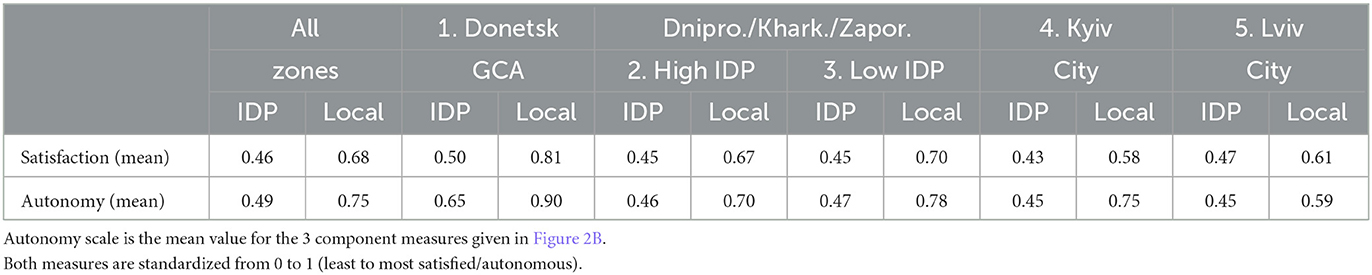

Our first indicator of SHW is derived from a common measure in the comparative literature on subjective wellbeing: a Likert scale capturing how satisfied people were with their housing conditions. As expected, IDPs reported lower levels of satisfaction than did locals. As Figure 2A demonstrates, 40% of IDPs reported being somewhat or very dissatisfied, vs. fewer than 20% of locals.

Subjective wellbeing at home, however, entails more than physical housing conditions. Home can also be the locus of a sense of autonomy and ontological (in)security (Saunders, 1986). Figure 2B shows the distribution of three measures of sense of autonomy at home: whether respondents felt home is a place they can get away from it all; do as they like; and have a say in deciding who can live there. In Ukraine in 2018, IDPs were much worse off than their local counterparts on all three measures.

These patterns were observed across Ukraine (Table 7). Mean levels of housing satisfaction and autonomy were remarkably similar for IDPs across zones (there was some variability for locals across zones, with higher levels of both mean satisfaction and autonomy in Donetsk, and lower levels in Lviv).

As Section 4.1 documented, most IDPs dwelled in worse conditions than they had before displacement and relative to the local populations in 2018, which we expect would account for their lower levels of satisfaction and sense of autonomy. Indeed, in regression analyses using the 2015 CHESS survey, we found that tenure, quality, and quantity were all strongly associated with both housing satisfaction and sense of autonomy at home across the former Soviet Union; homeownership is especially significant (Zavisca et al., 2021; Gerber et al., 2022). As we shall see in multivariate analysis below, this holds true for both IDPs and locals in Ukraine.

In focus groups and interviews, IDPs talked about the particular importance of ownership for housing satisfaction. Even when other conditions were satisfactory, owning was the overriding criterion. Employing a common turn of phrase, a home of one's own is required to “live normally” (c.f. Zavisca, 2012). For example, in a focus group in Lviv, an IDP renter explained that while very expensive, his rental conditions are “more or less normal” in terms of space and quality. “But you asked if we are satisfied. No, because…” “…it's not your own,” interjected another participant. “Yes, you said it,” he continued. “It's not mine. And satisfaction is only possible when your home is your own and you don't need to pay rent.” Another renter in Kyiv said: “My apartment is nice—in terms of comfort, I'd give it a 10 out of 10. It's the rent that burdens me. Overall, I'd score it a 5 on a scale of 1–10. But if it was my own apartment and I didn't have to pay rent, I'd rank it 100!” Likewise, an interviewee in Kharkiv who lives rent-free in a vacant apartment owned by a relative, said: “The price is satisfactory, nothing else is. It's in bad condition and needs to be renovated, and I can't afford to take that on. Because it's not my apartment. I'm living there as a guest.”

Laments about lack of security and control over the home pervaded our focus groups and interviews. Several IDPs described their housing situations as “living by the laws of birds,” an aphorism meaning to live a precarious existence without stability or rights. This sense of precarity extends low SHW beyond dissatisfaction. Housing is not simply a problem—it is the overriding problem of many IDPs.

6.2. The salience of housing as a personal problem

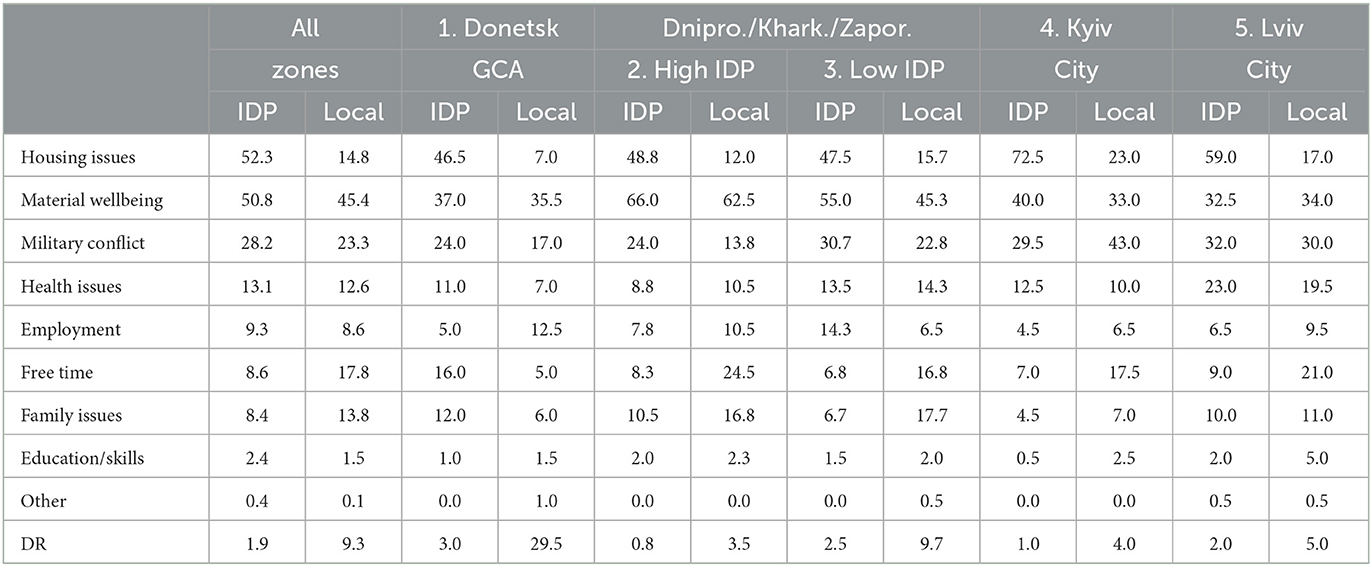

Housing in 2018 was far more salient as a major problem in everyday life for IDPs than for locals. We asked survey respondents to select their top two personal concerns from a list of issues. As Table 8 indicates, housing is a top problem for IDPs, selected by 52%, and far exceeding all other options besides material wellbeing. By contrast, just 15% of locals selected housing as among their top two concerns. Housing was by far the largest gap in selection of issues across the two populations and was pervasive across all geographic zones of our study. The issue was particularly stark in Kyiv (selected by 73% of IDPs vs. 23% of locals), likely due to very low housing affordability in the city.

We also asked survey respondents to specify their top housing concern: 47% of IDPs indicated that their main challenge is to acquire housing, vs. only 15% of locals. Locals were most likely to prioritize improving their current homes (40%) than IDPs (17%). Notably, one-third of locals said they have no housing concerns at all, compared to 9% of IDPs. These findings resonate with results of an IOM (2018) monitoring survey (which lacks a comparable local sample), in which 48% of IDPs indicated housing is their top problem, and among those, over half indicated that attaining a home of their own was their primary housing concern.

In our focus groups and interviews, IDPs emphasized how housing problems overwhelm them. For example, a renter in Kharkiv said: “My main problem, of course, is housing. This is a most painful question, unimaginably grave. Because my old house was destroyed in a single moment, and it is impossible to return. I so desperately want stable housing, an apartment where I can stay and make a home. Because from housing all other problems are born.”

6.3. Sense of being “at home” in one's community

Another lens on housing and integration is the sense of being or not being “at home” in new environs. In a review article on migrant perceptions of “psychological home,” Romoli et al. (2022) note that experiences of home “encompass more than spatial location and may include a sense of belonging, intimacy, and security, which contribute to one's wellbeing.” Prior research on IDPs in Georgia suggests that their lack of integration continually highlights for them their homes of the past; homes become a place of remembering rather than a door to local integration (Kabachnik et al., 2010). A study of Israeli settlers who were forcibly evacuated from the Gaza Strip and the West Bank likewise found that a negative sense of place post-displacement was nearly universal (Shamai, 2018). Ukraine presents a more mixed case, with considerable variance in sense of belonging in a new place.

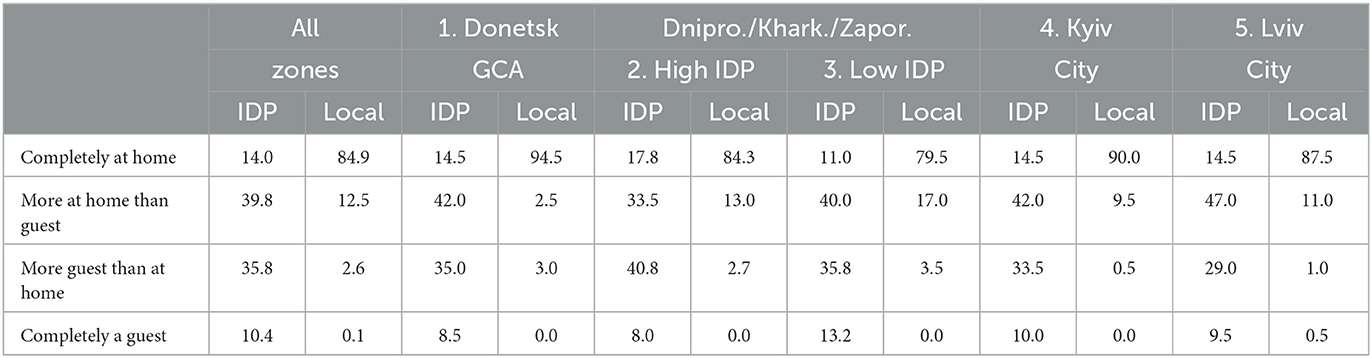

We asked both IDPs and locals to what extent they feel at home, vs. like a guest or visitor, in the city or town where they live. As Table 9 demonstrates, just over half of IDPs felt at home (40% mostly and 14% completely), while a large minority felt more like guests (36% mostly and 10% completely). By contrast, virtually all locals (97%) felt at home (12% mostly and 85% completely). These patterns were fairly consistent across zones, suggesting that this was a condition endemic to internal displacement across Ukraine and only modestly shaped by settlement destination.

Although this question refers to “home” in terms of locality rather than housing, we would expect housing experiences to condition the sense of local belonging, a marker of integration. Indeed, among those IDPs who owned their homes, virtually all (94%) felt “at home” in their places of residence, vs. only half of those who did not. Informants in our focus groups and interviews also identified housing—and specifically homeownership—as a primary condition for IDPs to feel “at home” in their new communities: for example, an interviewee in Kyiv said that although she wished she could return to Luhansk, she did not expect to, and appreciated the opportunities that Kyiv offers as a big city. “Still, I won't really call Kyiv my home until I own a home here. Because you are only at home when you own a home. Living as a renter, I can be kicked out onto the street at any time. That's not home. For me, home is a private apartment or house.” Said another interviewee in Lviv: “In principle, my friends would say about me, that I can feel at home anywhere, because wherever I go, I build up social capital. But all the same, it's hard without a material foundation. Financially, when you don't have housing, when all your money goes to rent…. I feel almost at home here, but when I own my own home, my own corner, then I will feel completely normal.”

6.4. Housing status and SHW: Accounting for integration gap

In this section we ask: to what extent do the various dimensions of housing status—tenure, quality, quantity—drive gaps in SHW? If housing status explains variation in SHW within groups—among IDPs and locals—this validates our measures of housing status are capturing what matters for wellbeing in Ukrainian society. Furthermore, if housing status accounts for gaps between IDPs and locals in SHW, this demonstrates that material housing conditions are key to integration in terms of wellbeing.

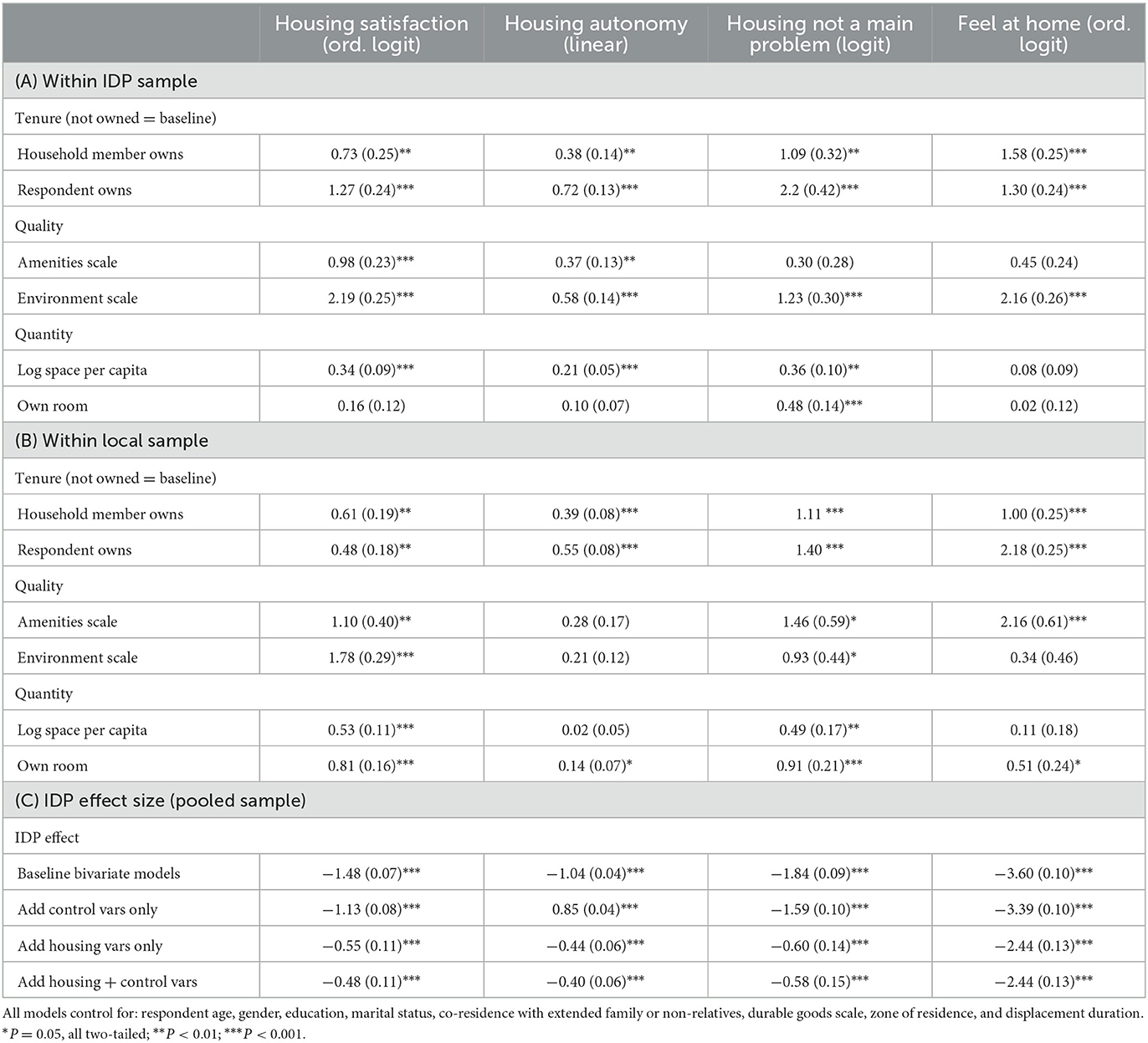

To answer these questions, we estimated regressions for each of our four indicators of SHW (Table 10). Generalized linear model type varies depending on the distribution of the dependent variable (linear, logit, ordered logit). Table 10A shows regressions for the IDP sample only, Table 10B for locals only, and Table 10C for the combined sample. Only effects of housing status variables, our substantive focus, are shown in the table; full models with controls and fit statistics are in the Appendix Tables A3a, A3b in Supplementary material.2

Among IDPs, homeownership is a significant predictor of each measure of SWB, net of other predictors (Table 10A). Furthermore, being on the title (respondent owner) is associated with higher SWB than living in a home owned by other household members for satisfaction, autonomy, and whether housing is a main problem (though the difference between respondent and household owners is only statistically significant for the latter measure). At least one measure of quality and quantity is also a significant predictor across all four SWB measures.

Findings are similar for locals (Table 10B). Tenure, quality, and quantity all matter across measures of SWB. Having one's own room is a significant predictor of all SWB measures for locals, but not for IDPs. Perhaps IDPs, struggling with more basic housing needs, are less focused on layout than overall space. Otherwise, the dimensions of housing status apparently hold similar value for both IDPs and locals. Our previous comparative work on SHW showed that tenure, quality, and quantity are all strongly associated with both housing satisfaction and sense of autonomy at home across the former Soviet Union including Ukraine, and homeownership is especially significant (Zavisca et al., 2021; Gerber et al., 2022).

Table 10C shows the extent to which housing status “explains away” differences between IDPs and locals in SHW. We assess this by comparing how the effect size for IDP changes when we add housing status measures to the model (following the approach of Perelli-Harris et al., 2022). The first row in this section shows the effect size of IDP in baseline bivariate models. For example, being an IDP yields a −1.48 difference in the log odds of improved housing satisfaction (in an ordinal model). The second row shows the IDP effect size after adding non-housing control variables to the model. We see that the effect size for housing satisfaction drops by about 25% to −1.13. The third row then adds our housing variables (the same block of variables as in Tables 10A, B), without other controls. This yields a much larger reduction in the IDP effect, to −0.55, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the gap between IDPs and locals. A full model with both housing and control variables accounts for very little of the IDP effect net of the housing variables model alone. The results are analogous for housing autonomy and housing as a main problem: material difference in housing status explain away the majority of the IDP gap in SHW, with little utility to adding additional controls (AIC and BIC fit statistics confirm that adding controls improves model fit net of housing for satisfaction and autonomy, but not for housing as a main problem or feeling at home; complete results available from authors). We interpret this as strong evidence that inequalities in material housing status impede not only material but experiential integration.

The results for feeling “at home” are especially interesting with respect to integration. Recall that this question asked whether people feel like they are more at home or guests in their communities, the question was not specifically about housing. This regression is hence our strongest test of the impact of housing on integration more broadly, as it moves beyond the domain of housing into broader experiences in displacement. Notably, our demographic, economic, and regional control variables explain almost none of the gap between IDPs and locals in feeling at home in their communities. By contrast, controlling for housing status reduces the gap by about one third. While housing does not entirely explain why IDPs feel less at home in their communities than do locals IDPs, clearly it plays a significant role.

7. Discussion

Our analysis of housing in Ukraine shows how exclusion of IDPs from culturally normative housing—in particular, homeownership—impeded their integration into host communities. Most IDPs could not become owners of decent quality homes even after prolonged periods in displacement, leaving them to live in substandard, insecure, unsatisfactory private rentals or public housing. In Ukraine, prior to Russia's full-fledged invasion of February 2022, the high costs of housing relative to income and lack of mortgage finance made sale of a home previously privatized by the state or gifted from family the primary basis for acquiring a new home. Ukrainians had most of their economic assets tied up in owning their homes, a consequence of post-Soviet privatization policies. IDPs had had to abandon that asset in the NGCAs, with very little hope of selling it, or of accumulating sufficient savings from labor market earnings to purchase a home in displacement.

These housing challenges significantly hampered IDPs' integration into local communities. In Ukraine in particular, an affordable home of one's own has been a key element of the post-Soviet social contract, yet in 2018 it remained out of reach for most IDPs. High rental costs put pressure on their incomes to cover costs that most Ukrainians did not have to bear, leading to financial vulnerability. Lacking a home of one's own was not only a financial disadvantage; it also impeded full political and cultural integration. IDP renters' inability to attain local residential registrations (propiska) posed barriers to voting, a key practice of citizenship. Housing challenges also exacerbated a sense of being out of place: IDPs were less likely than their local counterparts to feel satisfied with their homes, autonomous when at home, or more broadly at home in their communities. Half of IDPs in our sample still felt like guests or visitors where they lived after several years of displacement within their own country.

As noted above, a rationale on the part of the international community and the Ukrainian government to not house IDPs collectively or in new settlements built for them was that collective living would impede them from integrating. Our data suggest that uncoordinated private resettlement does not necessarily promote integration either. While Ukrainian IDPs would not necessarily have been better off had they been placed in long-term collective settlements, our findings suggest that individualized re-settlement approaches are insufficient to promote housing conditions that facilitate local integration in a way that allows IDPs to feel truly at home. Significant housing differences between IDPs and locals, largely irrespective of where they resettled in Ukraine, are a constant reminder of their own displacement.

We acknowledge a number of limitations to this study. Our empirical analysis is constrained to the domain of housing, examining relationships between material housing status and SHW. While these findings are suggestive of the significance of housing and especially homeownership for broader IDP integration, further analysis could extend to analyze the relationship between housing and other domains of integration such as employment, social networks, and health. Resource and feasibility constraints limited the age range (adults aged 18–49) and geography (12 localities across 5 socio-spatial zones) of our sample. Lack of access to a probabilistic sampling frame for IDPs, necessitated non-probability sampling techniques. That said, the remarkable consistency of our findings across these zones suggests that they reflect countrywide tendencies in IDPs' lived housing experiences in displacement, not simply artifacts of our sample limitations.

Our survey was collected before Russia's full-fledged invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, which spurred radical and, as of this writing, continuing changes to the dynamics of displacement. In a sadly prescient reflection on the experience of displacement in 2018, one focus group participant, after discussing what it means to feel at home, said: “Even in Kyiv there isn't true stability. Even if you could buy an apartment and establish roots, you think, what for? All of this could end here too, it's scary. We understand that everything can end overnight.” Now, the entire nation is vulnerable to displacement, with nearly 40% having fled their homes as of this writing. Those who are not fully displaced surely suffer far more widespread crises of housing than our “local” respondents did in 2018. As Ukrainians return and rebuild, the experience of displacement will affect housing experiences and prospects. We conclude by reflecting on the relevance of our findings for the contemporary situation and planning for reconstruction and recovery.

The scale of Ukraine's housing and displacement catastrophe since February 2022 dwarfs that of the period after early 2014. Rebuilding will be a very heavy lift: according to a May 2022 report by the Kyiv School of Economics, residential buildings and roads accounted for about $60 billion, or nearly 10% of economic losses (even at that early date) and counting (KSE, 2022). As Russia continues to target civilian infrastructure, including housing, for destruction, Ukraine risks being further pushed into a society of housing haves and have nots. Already, recent IDPs are navigating exorbitant rental costs and eviction, without practical or legal recourse (Bobrova, 2022). Now too, many are living in places never meant to be homes (Bubola and Specia, 2022). In part because of the huge volume of IDPs, Ukraine is using schools and dormitories to house the displaced, as officials consider a myriad of options to give them shelter, including monetary aid to people whose homes have been destroyed by Russian attacks (Filipchuk and Syrbu, 2022).

As calls for an internationally supported “Marshall Plan” for Ukraine's reconstruction gain traction, housing needs to be central in these plans (Conley, 2022). Ukrainian housing advocates are proposing ways forward for long-term housing solutions (all of which will require major international assistance). For example, Cedos, the premier Ukrainian NGO conducting research-informed advocacy on housing policy, recommends investment in social (public) housing stock, which practically disappeared after privatization, plus measures to support and regulate private renting. Indeed, affordable social housing, as well as private rentals, which were lacking in Ukraine even before the war, are critical components of a healthy housing system (Bobrova et al., 2022a,b).

In our view, effective long-term reconstruction must also include affordable pathways into purchase of culturally normative housing. Ukraine is a “homeownership society,” with over 90% of Ukrainians living in owner-occupied homes prior to displacement. According to our prior research, homeowners in Ukraine and other formerly Soviet societies have a stronger sense of SHW (Zavisca et al., 2021) and are more likely to be civically and politically active (Gerber and Zavisca, 2018). Losing a home thus not only harms living standards, it also erodes the sense of belonging and civic engagement—the very characteristics a society needs to rebuild. How people become homeowners also matters. The psychosocial benefits of homeownership in post-Soviet contexts, including Ukraine, are strongest among those who have purchased their homes (as opposed to receiving them through privatization or inheritance) (Gerber et al., 2022). Subsidized homeownership models (that is, with subsidized interest rates and insurance to protect borrowers from unemployment or inflation) would enable rebuilding a housing system with Ukrainian ownership norms, while expanding access so that options to own are not simply a function of family or (mis)fortune.

The benefit of multiple, affordable pathways to homeownership is a clearer pathway to local integration. We advocate including multiple ownership models in plans for housing reconstruction in Ukraine—as not only the right thing to do, but also the smart thing to do. Building “permanent” housing in less-than-ideal locations, as was done in Georgia after the 2008 Russian invasion, will not promote the sense of normalcy and belonging that is so necessary to rebuild Ukraine.

Furthermore, the propiska registration system urgently needs dramatic revision so as not to perpetuate barriers to the social and political integration of displaced persons on the basis of housing. Progress had been made in decoupling IDP registration, which is based on locality of residence, from the propiska system, which is based on documented rights to a specific place of residence (IOM, 2018). Nevertheless, the lack of local propiskas due to rental tenancy continued to present obstacles to accessing local services and rights, from voting to medical care to banking—all markers of integration. IDPs would benefit from propiska reforms that would also help all Ukrainians (Solodko et al., 2017; Slobodian and Fitisova, 2019).

The massive scale of displacement will also require rethinking the categories of IDP and local. Many Ukrainians are now displaced in their own cities, as housing destruction is widespread and seemingly random, with some buildings destroyed, and neighboring ones left unscathed. Preferably, community-based approaches would make new housing opportunities accessible to anyone in need, and wherever they choose to settle. This could also make housing assistance for those perceived as newcomers or outsiders more politically viable. Based on research on the wave of displacement that started in 2014, the initial welcome of IDPs eroded as the entire nation struggled. While IDPs experienced the worst upheaval, Ukraine's broader population had also seen living standards fall—as the conflict occurred in the context of a deep economic recession, with a cumulative real GDP decline of 17% from 2013 to 2015, and the currency losing one-third of its value against the dollar (RFERL, 2016). Although locals remained objectively better off as a group than IDPs with respect to housing, subjective perceptions suggested otherwise. In our survey, we asked both IDPs and locals who has more housing need, and who should get priority for subsidized mortgages should they become available. Half of locals perceived that their housing situations are equal to (40%) or even worse (7%) than that of IDPs. Furthermore, only 22% of locals supported the notion that IDPs should have priority for subsidized mortgages. Given these perceptions, developing new housing opportunities open to all citizens would be more likely to garner wide support, and could facilitate societal integration for IDPs.

In conclusion, our research suggests that solving the housing and residential permit problems for Ukrainian IDPs will foster broader integration. Ukraine avoided a trap that other post-Soviet societies fell into by spatially concentrating the displaced and segregating them from local populations. But it must utilize new solutions to integrate its society socially, economically, and politically through housing. Investment in pathways to homeownership as well as secure rental and public housing, coupled with reforming of the propiska system, could break down barriers between IDPs and locals, housing haves and have nots—key ingredients to successful integration.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JZ, BM, and TG contributed to the conception and design of the study and the collection of the data. JZ organized the dataset and performed the statistical analysis. JZ and BM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Research for this paper was supported in part by a grant from the US Army Research Laboratory and the US Army Research Office via the Minerva Research Initiative program under grant number W911NF1310303.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views reported herein are not the views of the US Army or US Government.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fhumd.2023.1086064/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Four years was the maximum because displacement began in 2014 and the survey was conducted in 2018. Alternatively, we could have controlled for time residing in locality, which would also allow for comparing IDPs with other movers within Ukraine. However, only 2% of locals had moved localities within the prior 4 years, so there are insufficient cases of local movers for meaningful comparison. Furthermore, only 3% of IDPs had moved localities more than once since displacement, so duration in locality and duration in displacement are highly correlated for IDPs.

2. ^Although a detailed discussion of all the predictors of SHW would take us beyond our focus, we note that our measure of possession of durable goods has consistently strong, positive effects on all four outcomes, and IDPs who were displaced four years have consistently lower SHW than those displaced two or fewer years ago. The patterns regarding housing obtain even after controlling for these two intuitive effects.

References

Adam, F., Föbker, S., Imani, D., Pfaffenbach, C., Weiss, G., and Wiegandt, C. (2021). “Lost in transition”? Integration of refugees into the local housing market in Germany. J. Urban Aff. 43, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2018.1562302

Ager, A., and Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: a conceptual framework. J. Refug. Stud. 21, 166–191. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fen016

Becker, S., and Ferrara, A. (2019). Consequences of forced migration: a survey of recent findings. Labour Econ. 59, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2019.02.007

Belloni, M., and Massa, A. (2022). Accumulated homelessness: analysing protracted displacement along Eritreans' life histories. J. Refug. Stud. 35, 929–947. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feab035

Bobrova, A. (2022). The War in Ukraine Has Caused a Housing Crisis. Here's How to Combat It. Available online at: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/russia-ukraine-war-housing-crisis-displaced/ (accessed October 28, 2022).

Bobrova, A., Lazarenko, V., and Khassai, Y. (2022a). Housing and War in Ukraine. Cedos. Available online at: https://cedos.org.ua/en/researches/housing-and-war-in-ukraine-march-24-june-3-2/ (accessed October 28, 2022).

Bobrova, A., Lazarenko, V., and Khassai, Y. (2022b). Social, Temporary, and Crisis Housing: What Ukraine Had When It Faced the Full-Scale War. Cedos. Available online at: https://cedos.org.ua/en/researches/social-temporary-crisis-housing/ (accessed October 30, 2022).

Boccagni, P. (2016). Migration and the Search for Home: Mapping Domestic Space in Migrants, Everyday Lives. Berlin: Springer.

Brun, C. (2015). Home as a critical value: from shelter to home in Georgia. Refuge 31, 43–54. doi: 10.25071/1920-7336.40141

Brun, C. (2016). Dwelling in the temporary. Cult. Stud. 30, 421–440. doi: 10.1080/09502386.2015.1113633

Brun, C., and Fabos, A. (2015). Making homes in limbo? A conceptual framework. Refuge 31, 5–17. doi: 10.25071/1920-7336.40138

Bubola, E., and Specia, M. (2022). Ukraine's herculean task: helping millions whose homes are in ruins or Russia's hands. New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/06/world/europe/ukraine-war-refugees-displaced.html?smid=url-share (accessed October 28, 2022).

Buckley, C. (1995). The myth of managed migration: migration control and market in the Soviet period. Slavic Rev. 54, 896–916.

Burdyak, A., and Novikov, V. (2014). Housing finance in Ukraine: a long way to go. Hous. Finance Inter. Autumn, 17–25. Available online at: https://www.housingfinance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/HFI-3-2014.pdf (accessed October 28, 2022).

Chattoraj, D. (2022). “A sense of attachment, detachment or both: voices of the displaced persons,” in Displacement Among Sri Lankan Tamil Migrants. Asia in Transition, vol 11. Singapore: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-981-16-8132-5_5

Cheung, A., Makhashvili, N., Javakhishvili, J., Karachevsky, A., Kharchenko, N., Shpiker, M., et al. (2019). Patterns of somatic distress among internally displaced persons in Ukraine: analysis of a cross-sectional survey. Soc. Psych. Psych. Epid. 54, 1265–1274. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01652-7

Conley, H. (2022). A Modern Marshall Plan for Ukraine. German Marshall Fund. Available online at: https://www.gmfus.org/news/modern-marshall-plan-ukraine (accessed October 28, 2022).

Czischke, D., and Huisman, C. J. (2018). Integration through collaborative housing? Dutch starters and refugees forming self-managing communities in Amsterdam. Urban Plan. 3, 156–165. doi: 10.17645/up.v3i4.1727

Dean, L. A. (2017). Repurposing shelter for displaced people in Ukraine. Forced Migration Rev. 55, 49–50.

Delfani, N., De Deken, J., and Dewilde, C. (2014). Home-ownership and pensions: negative correlation, but no trade-off. Housing Stud. 29, 657–676. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2014.882495

Diener, E., Oishi, S., and Tay, L. (2018). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Human Behav. 2, 253–260. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6

Donato, K. M., and Ferris, E. (2020). Refugee integration in Canada, Europe, and the United States: perspectives from research. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 690, 7–35. doi: 10.1177/0002716220943169

Dunn, E. C. (2012). The chaos of humanitarian aid: adhocracy in the Republic of Georgia. Humanity 3, 1–23. doi: 10.1353/hum.2012.0005

Filipchuk, L., and Syrbu, O. (2022). Forced Migration and War in Ukraine. Cedos. Available online at: https://cedos.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/forced-migration-and-war-in-ukraine-march-24%E2%80%94june-10-2022.pdf (accessed October 27, 2022).

Fozdar, F., and Hartley, L. (2014). Housing and the creation of home for refugees in Western Australia. Hous. Theory Soc. 31, 148–173. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2013.830985

Gerber, T. P., and Zavisca, J. (2018). Civic Activism, Political Participation, and Homeownership in Four Post-Soviet Countries. PONARS Eurasia. Available online at: https://www.ponarseurasia.org/wp-content/uploads/attachments/Pepm505_Gerber-Zaviska_Feb2018.pdf (accessed October 10, 2022).

Gerber, T. P., Zavisca, J. R., and Wang, J. (2022). Market and non-market pathways to homeownership and social stratification in hybrid housing regimes: evidence from four post-Soviet countries. Am. J. Sociol. 128, 866–913. doi: 10.1086/722927

IOM (2012). IOM and Migrant Integration. Available online at: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/migrated_files/What-We-Do/docs/IOM-DMM-Factsheet-LHD-Migrant-Integration.pdf (accessed March 13, 2023).

IOM (2018). National Monitoring System Report on the Situation of Internally Displaced Persons: September 2018. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine/national-monitoring-system-report-situation-internally-displaced-persons-september-0 (accessed August 26, 2019).

Kabachnik, P., Regulska, J., and Mitchneck, B. (2010). Where and when is home? The double displacement of Georgian IDPs from Abkhazia. J. Refug. Stud. 23, 315–336. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feq023

Kandylis, G. (2019). Accommodation as displacement: notes from refugee camps in Greece in 2016. J. Refug. Stud. 32, i12–i21. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fey065

Kharabara, V. (2017). Analysis of mortgage lending in banks in Ukraine. Balt. J. Econ. Stud. 3, 59–63. doi: 10.30525/2256-0742/2017-3-3-59-63

Koch, A. (2020). On the Run in Their Own Country: Political and Institutional Challenges in the Context of Internal Displacement. SWP Research Paper 5. Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP). doi: 10.18449/2020RP05

Kreichauf, R. (2018). From forced migration to forced arrival: the campization of refugee accommodation in European cities. Comp. Migration Stud. 6, 1–22. doi: 10.1186/s40878-017-0069-8